Summary

Mike Ash explores the idea that prophets play a creative role in the process of revelation, shaping the divine message through their unique human experiences and perspectives. This perspective emphasizes the collaborative nature of scripture, where divine inspiration and human agency intersect to produce sacred texts that reflect both heavenly and earthly influences.

This talk was given at the 2021 FAIR Annual Conference on August 6, 2021.

Mike Ash is a longtime FAIR contributor and author, best known for his books and essays on the intersection of LDS doctrine, history, and critical thinking. He brings a balanced, faithful, and thoughtful approach to apologetics that resonates with many seeking both belief and intellectual engagement.

📖 Rethinking Revelation and the Human Element in Scripture: The Prophet’s Role as Creative Co-Author 1

Transcript

Mike Ash

Rethinking Revelation and the Human Role in Scripture: The Prophet’s Role as Creative Co-Author

Rethinking Revelation and the Human Element in Scripture: The Prophet’s Role as Creative Co-Author

Thank you, Scott. What a marvelous conference this has been! It’s so exciting to be here, meeting people in person and being very grateful for the presentations that have happened already this morning and yesterday. Many of them dovetail with my own topic.

For the last eight to ten years, I’ve been working on a project that has culminated in this book entitled “Rethinking Revelation and the Human Element in Scripture: The Prophet’s Role as Creative Co-Author.” I started this just as I was finishing up my second edition of “Shaken Faith Syndrome.” No matter how many times I tried to cut it, it still ended up being over 700 pages. So, even though I hope it’ll be an intellectual, and maybe a spiritual tool, if nothing else, it might be a great doorstop.

The fundamental points that I hope to make in my book are to show how our scriptures are a product of inspiration and intellect, how this synthesis automatically and unavoidably draws upon a prophet’s cultural intellect, how this mortal element in scripture-making automatically introduces the mistakes of men, and how this errant scripture can still serve as consecrated narratives.

Written Nuggets

Since finishing my book, I have found nuggets of gold in the writings of other LDS and non-LDS writers. To quote Socrates, although some people attribute the quote to Plutarch, “Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel.” So, some of the nuggets I’ve discovered after submitting my book for publication are included in this presentation.

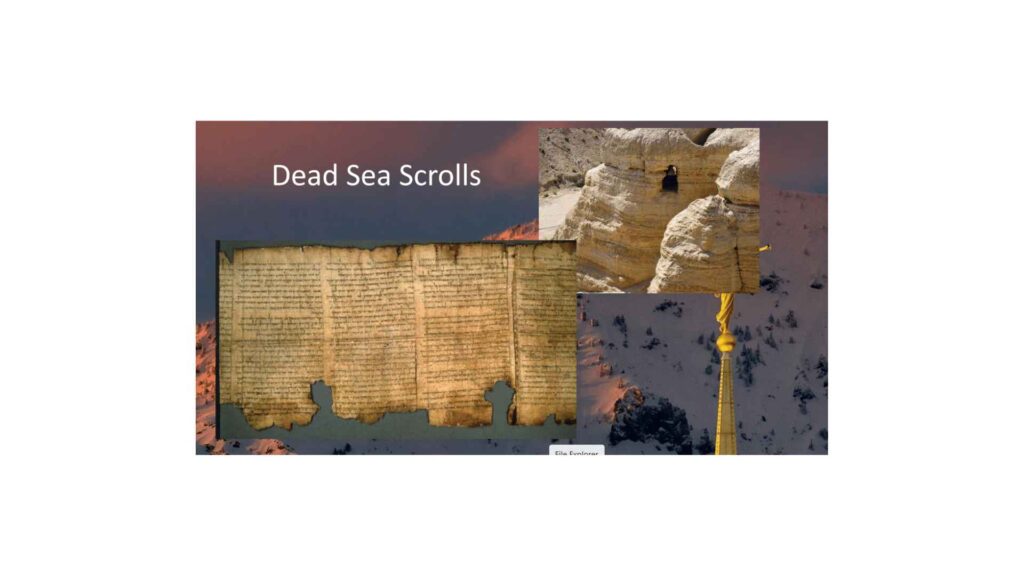

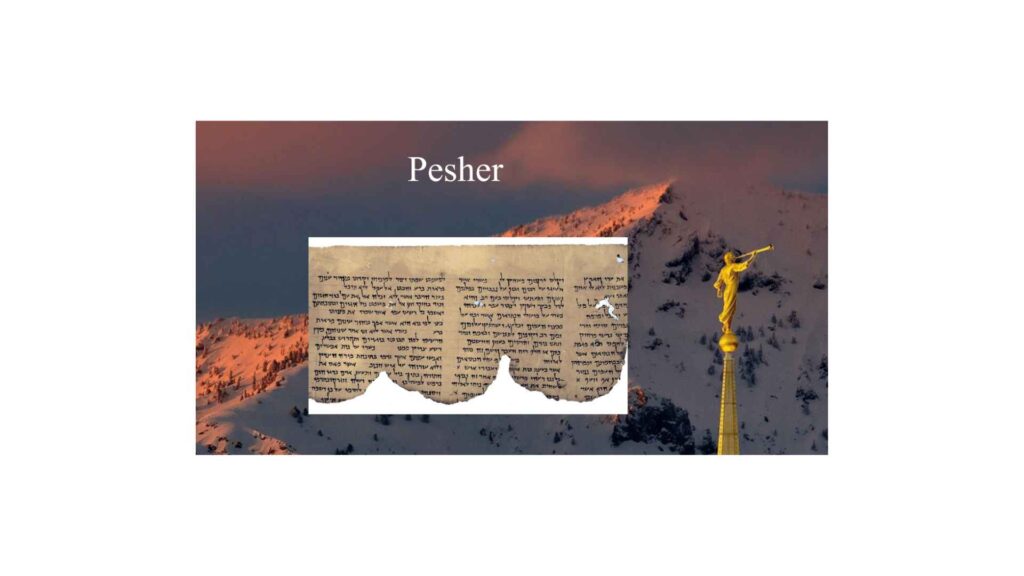

The community that created and preserved much of what is known as the Dead Sea Scrolls is often referred to as the Qumranian or Qumran community. For a time, the Qumranian’s leader was known as the “Teacher of Righteousness,” even though he is never ascribed the title of a prophet. Writes Dr. Travis Williams, “The descriptions of his role in authority within the community are reminiscent of prophetic activity. The Qumranians believed that the teacher had the power and authority to engage in a type of sacred proof-texting and was justified in adapting the message of ancient biblical texts to the Qumranian’s day and cultural circumstances.”

Exegesis

The word “exegesis” basically means to interpret a text. “Eisegesis” means to read our thoughts into a text. So technically, what the Teacher of Righteousness was doing was Eisegesis. Most scholars, however, referred to the method of interpretation found in Qumran and other biblical texts as contemporizing exegesis, actualizing exegesis, charismatic exegesis, revelatory exegesis, and creative exegesis.

Pesher exegesis is also found in the Old and New Testaments. According to biblical scholar Dr. Peter Ends, during the post-exilic period (5th century BC and onward), some Jewish community members had creative ways of handling their Bible as they sought to apply it to their changing circumstances. Uriel Simon, a professor at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, claims that the study of the Torah cannot rest content unless it is reinforced by creative exegetical work that arises out of, and responds to, the needs of this generation.

The Gospels

Some scholars argue that the Gospels likewise use a similar exegesis when connecting Christ to the Old Testament Messiah. In the Gospel of Matthew, writes Dr. Andy Woods, we find a collection of arguments written to a Jewish audience, fashioned to convince them that Christ truly was the long-awaited Davidic Messiah spoken of in the Old Testament. Ends similarly argues that Matthew was a creative reader of the Bible, as was par for the course in the Judaism of his day.

As LDS scholar Charles Harrell points out, New Testament writers not only drew on Old Testament passages as proof texts to bolster their witness of Christ, but they sometimes embellished events to better accommodate these proof texts.

According to some scholars, including non-Mormon scholars, the prophets and apostles were divinely authorized and aspired to engage in creative exegesis.

Non-LDS theologian Dr. Earl Ellis, for example, argues that the interpretation of scripture is a key feature of prophetic activity. Evangelical scholar Robert Thomas believes that the apostles had the right qualifications when it came to creative exegesis.

He explains that “New Testament writers. . . possessed the gift of apostleship and/or the gift of prophecy, enabling them to receive and transmit direct revelation from God. . . .These gifts enabled the gifted ones to practice what is called ‘charismatic exegesis’ of the Old Testament. This practice entailed finding hidden or symbolic meanings that could be revealed through an interpreter possessing divine insight.” As an evangelical Christian, Thomas believes that those gifts died off with the apostles, and that no contemporary interpreter possesses those gifts today.

Sowed

In Judaism, one of the rabbinic exegetical approaches to interpreting the Torah was known as “sowed” – a belief that scriptural texts contained a deeper true meaning.

For example, in Amos 3:7, we are told that God revealed His secret unto His servants, the prophets. The word “secret” in this verse comes from the Hebrew “sowed.” Mosiah likewise claims that a seer can not only see the past and the future but also secret and hidden things. Not completely unlike the Teacher of Righteousness, Nephi, we are told, did liken all scriptures unto his people for their profit and learning.

I believe a prophet has the divine calling and right to appropriate and repurpose various cultural ideas, teachings, artifacts, and even documents. As a prophet, he has the transformative power to liken all things as tools to draw people to Christ. A prophet does not need to be the one to create or compose a story narrative for it to qualify as scripture. He is authorized and empowered to liken past and present narratives, thereby creating divine connections that sanctify the narrative of scripture.

Likening Ancient Scripture to Our Times

Likening an ancient narrative, however, almost assuredly requires a modification of that narrative to meet the language, idioms, culture, and worldviews of the audience to which the narrative is likened. As I argue in “Rethinking Revelation,” a prophet’s likening to the word of God acts in a way like the blessing of plain bread and water at the sacrament table; it elevates the scriptural narrative. Like the bread and water, it is something holy that has the power to bring us to Christ and unites us with God and the rest of His covenant people. This is why I refer to the scriptures as consecrated narratives.

The sacrament bread and water needn’t be one hundred percent perfect; we have wheat or white, crust, no crust, and gluten-free, and at times other things instead of bread. So, they needn’t be one hundred percent perfect to serve as salvific vehicles, which means they’re emblems that can help facilitate the power of Christ’s saving atonement. Likewise, scriptural narratives need not be perfect to serve as consecrated vehicles that open our hearts and minds to personal revelation and bind us to God.

Scriptures can, therefore, be a mix of various things. They can relate tales of myth and legend, which might have little to no basis in fact, but were perceived to be authentic by those who recorded the narratives. They could be mostly accurate narratives that recount the essential elements, feelings, or intent of past events but are punctuated by the inaccuracies, exaggerations, or minimizations of human memory or bias. Or they could be accurate historical narratives and cultural legends.

Creative Exegesis

When we appreciate the role of creative exegesis in biblical and Book of Mormon times, I think we gain a greater understanding of how Joseph might have translated the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham and, quite frankly, how he received any revelation.

So, what do I mean by the human element of the scripture or my claim that prophets are creative co-authors? First, it’s important to note that this label does not mean that I believe Joseph simply made up fictitious material to supplement or blend with divine revelation. Instead, it means that Joseph would have intuitively recontextualized divine input according to what he already thought, knew, or presumed.

According to American theologian Richard Phillips (I stumbled across this after I’d already published the new book and was preparing this presentation), the human element in scripture incorporates the experiences, perspectives, and even feelings of various authors. Since finishing my book, I have been surprised to discover how often writers refer to the human element in scripture.

As Archibald Hodge and Benjamin Warfield wrote in 1881, we do not deny a human element in the scriptures. The scriptures, these writers note (and as non-LDS, they’re referring to the Bible), are the product of the dual authorship of both God and man. Scripture is not only man’s word, wrote non-LDS theologian J.I. Packer, but also equally God’s words spoken through man’s lips or written with man’s pen. In other words, scripture has double authorship, and man is only the secondary author. Even according to the Catholic doctrine of inspiration, it is commonly understood that God is the primary author of scripture, and the sacred writer is the secondary author.

Co-Authorship

The prophet’s role as co-author is present when creating new scripture, recontextualizing existing scripture for a modern audience, or when translating scripture.

As New Testament scholar Dr. K.K. Yao explains, translation does not convey the original intent of one language to another with perfect clarity. The interpreter should recognize, he argues, that reading interpretation is always constructive. The interpreter plays a significant role in the meaning-producing process. The creative, constructive work of the reader cannot be absent from the reading process.

While most other churches believe that this co-authorship produces necessarily errant or virtually inerrant scripture, many Christian theologians reject the belief that God produced the scripture through mechanical means, where God overrides the human faculties of the inspired author or simply dictated audibly or mentally the words that were to be written. So, they reject this, according to what is known to biblical scholars as the dynamic theory of scriptural creation. God gave the writers of scriptures the ideas, and then they selected the best words to describe them. He gave the thoughts to the men chosen and left them to record their thoughts, their own dynamic inspiration. Some scholars refer to this as the inspired concept theory, where concepts are inspired while the word choices are not.

We find similarities in the theories regarding Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon. Although different LDS scholars don’t necessarily agree about how tight or loose Joseph’s translation was or what was written on the Nephite plates, most LDS scholars recognize that Joseph’s own thoughts would have participated in the translation process. Even Royal Skousen, who has argued for a tight control theory, has more recently suggested the Book of Mormon translation is a creative and cultural translation that involves considerable intervention by the translator.

Co-Participation Model

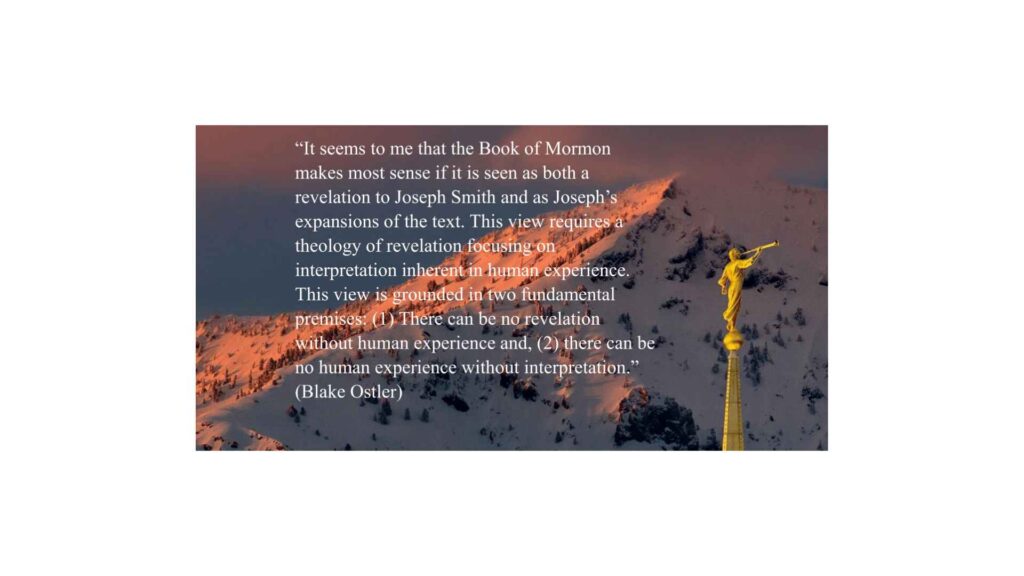

I propose a co-authorship position that more closely aligns with the theories proposed by Brant Gardner and Blake Ostler. In Blake Ostler’s original article, in which he theorized an expansion theory for the Book of Mormon translation, Ostler proposed a creative co-participation model for revelation.

”It seems to me that the Book of Mormon makes most sense if it is seen as both a revelation to Joseph Smith and as Joseph’s expansion of the text. This view requires a theology of revelation focusing on the interpretation inherent in human experience. This view is grounded in two fundamental premises. 1) there can be no revelation without human experience, and 2), there can be no human experience without interpretation.“

This translation theory of Ostler’s, and Brant Gardner’s is very similar to that, is similar to the approach I take to Joseph’s translations. And if we believe that Joseph and all the prophets are co-authors in producing translation scripture, then I believe that it means that we might find elements of the author in those scriptures.

Four years ago, I gave a talk at the 2017 FAIR Conference entitled “After the Manner of Their Language: The Key to Wisdom.” The talk included material for the project that ended up being in this book. I won’t rehash the material from that talk because you can look it up or watch it on YouTube. But to summarize what I presented, I found that cognitive studies shed some interesting light on why we humans do the things we do or think the things we think. Our brains want to see patterns, so we see patterns. These patterns exist not only in the things we see and hear, but in our concepts and worldviews. We’ve learned about this a little bit in some of the other presentations.

God’s Accommodations

God obviously knows that our brains have an affinity to patterns, and I believe He leverages these cognitive quirks when He communicates with us. He accommodates our inherent worldviews and bias-defined patterns by allowing us to re-contextualize gospel truths according to the manner of our own language. Divine communication, I wrote, appears to be a mix of divine accommodation and humankind’s recontextualization.

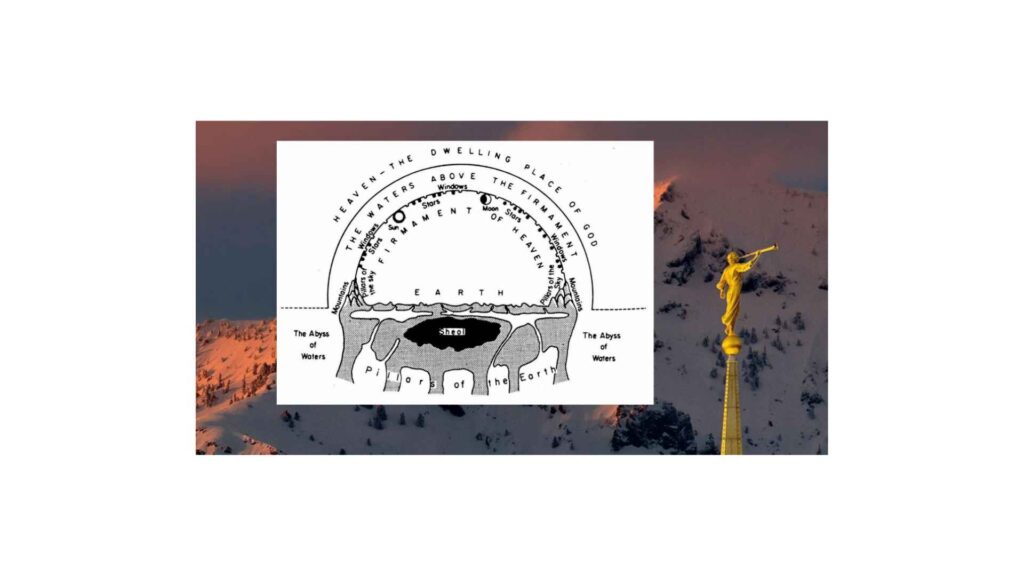

In biblical times, for example, the Hebrews re-contextualized God’s revelation about our relationship to Him and the cosmos by adapting divine truths to the creative narratives from their surrounding communities. Thus, the creation story in Genesis was not written as a scientific recounting of how God created the cosmos, but rather as a recontextualization, probably relying on Mesopotamian cultural tales, to speak to the Israelites of the day and to liken those cultural tales in a co-authorship of divine revelation so that the Israelites could see themselves in the story and know that God still loved them and was the power behind their existence.

I believe the human element can be found in all the scriptures, and in my book, I give examples from the Bible, the Doctrine and Covenants, the Book of Abraham, and the Book of Mormon. In the interest of time, I’m just going to share a couple of examples.

The First Vision

The First Vision. I believe the human element can be found in the retelling of Joseph’s first vision which occurred approximately 1820. His earliest recital however dates to 1832. Joseph then created a recital in 1835, another one in 1838, and then 1842. The 1838 account ultimately became the official account. One of the biggest problems between the different versions according to critics, is that Joseph only mentions being visited by the Lord in the first recital, but two personages in subsequent recitals. It’s important to know that Joseph purposefully created the 1830 recital to set the record straight because of the many anti-Mormon reports that were circulating at the time.

So here’s where my 2017 talk and the material which is expanded for my book might come in handy. It explains how our minds, memories, and culture connect the dots to solve puzzles, or to paint a bigger picture of the human element in the retelling of the first vision.

Is it possible that through the years Joseph misremembered some of the details of his vision, innocently or intentionally embellished other details, or forgot yet other details or the sequence of events? Absolutely. In fact, I would say it’s an absolute certainty that not one of the recitals is entirely accurate and fully complete, for the same reason that every story you or I or anyone else tells is not entirely accurate or complete.

Objectivity

No recounting of any historical event would pass a test of complete objectivity or can share every detail. Something will always be left out, something will always be emphasized, while other things will be de-emphasized. Thanks to unavoidable human bias, some things will be explained with perfunctory reports, while other things will be elucidated with comprehensive descriptions. Some things will be wrong, some things will be partially incorrect or partly right, and some things will be incomplete.

We are humans. Regardless of whether someone accepts the first vision as a real event or not, discrepancies between recitals do not prove that Joseph falsified the account, but they do show that he was human.

When Joseph recorded his first known account of the theophany in 1832, a dozen years had passed, plenty of time for Joseph to forget or conflate some of the details, and plenty of time to recontextualize the event according to his 1832 brain. The story’s retelling would be different from the way the story would have been told in 1820. our future selves unavoidably see things differently than our past selves. One of many inescapable characteristics of human nature is that a retelling of past memories will becolored by the time period lens in which we recount the memory.

As neuroscientist Matthew Hudson explains, our brain memories instinctively “revise our histories to make better stories, emitting certain details and changing others so they conform to a cohesive, compelling, and often complimentary tale.” Thus in hindsight we see that otherwise random events will align in a pattern that serves our story, unaware that we, unconsciously “custom-fit the theme to the events.”

Religious Revivalism

Joseph’s First Vision occurred in a place and time of religious revivalism, where many frontier people searched for spiritual truths, attended revivals, and experienced supernatural experiences, including others who claimed visitations from Christ. (And I am of the opinion that if someone claims a visitation from Christ, who are we to say they did not?) In the 19th century, visionary recitals were mainly shared by word of mouth, but at least a few were recorded in print. Thus, it’s reasonable to assume that Joseph would have heard about neighborhood visions, both before experiencing his own vision, as well as after his first vision, but certainly prior to his first known recital in 1832. It also seems reasonable to assume that Joseph, hearing or reading of the visions of others, might have influenced the structure, sequence, and emphasis which Joseph instinctively selected when recounting his own experience.

Elements we find in some of the other 19th-century revivalist visions include retiring to the woods or some other private place to pray, a dark and wicked presence which attempts to hinder the prayer, a white shining light, communication from the Lord, and a personal joy enveloping the one receiving the vision. In every instance where we have a record, the visionary was told or felt that their sins were forgiven. Joseph had to have been familiar with at least a few of these accounts for the simple fact that there may have been many more visions which were shared verbally or lost to history, than the few remaining examples that have survived in documented form.

In 1832, when he recorded his first recital, Joseph would naturally have drawn upon his memories and the framework of similar stories to produce a brief description of his visitation from Deity. While some of the visions contemporary to Joseph’s vision mention the appearance of both the Father and the Son, the most common theme seems to be a visitation from the Lord who lets the supplicant know that he or she was forgiven of their sins. This seems to be the approach Joseph took with his earliest recital, as well.

In 1832 when he briefly described his vision, his vision depicted a significant personal spiritual experience, the framework in which he portrayed the experience was perhaps a bit of a “me too” chronicle. It seems reasonable to conclude that Joseph was not only aware of the other visitation accounts, but also aware that prospective Latter-day Saints in his community were equally aware of the collected recitations of such visitations.

The Book of Mormon

To Joseph and his followers of the time, such a visitation was not by itself uniquely vital to his role as a prophet or founder of a new church. The Book of Mormon was the key element in his new religious movement. It wasn’t until many years later when the memory of similar manifestations began to fade and a more developed LDS narrative began to form, that the First Vision became a vital ingredient once again, shaped by hindsight expectations in the restorative narrative.

As one who both accepts the modern scholarly view of memory as well as the belief that Joseph was an honest mortal with a divine calling, I accept the primary truthfulness of the 1830 account. And in all his accounts, except for the 1832 report, Joseph mentions two personages, and I believe that Joseph was, in fact, visited by two personages. In the context of creating his earliest-known recital vision, the emphasis was one of personal nature, with past sins absolved by Jesus. Joseph intuitively framed his 1832 narrative to speak to audiences familiar with the stories of other visions in his environment.

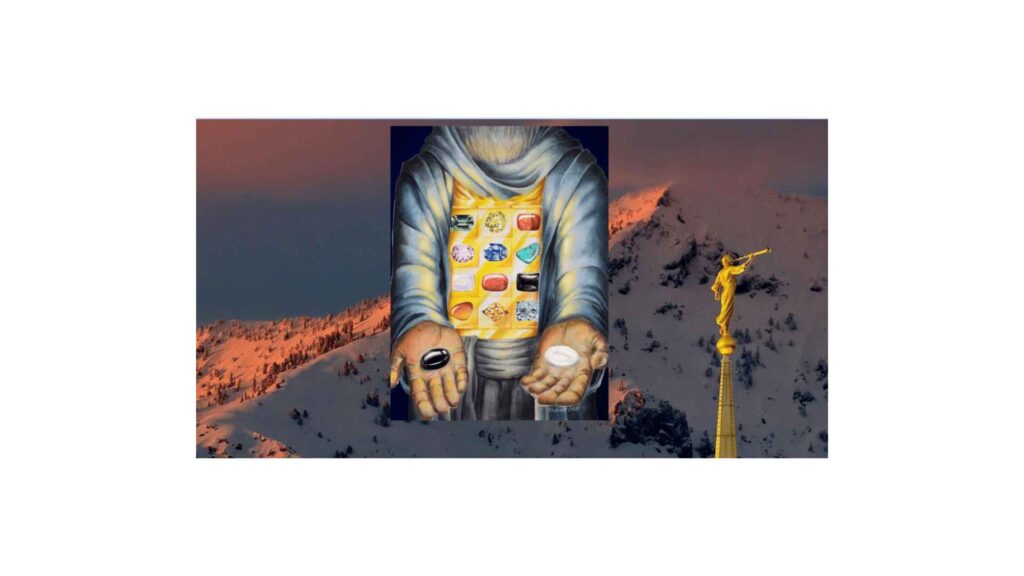

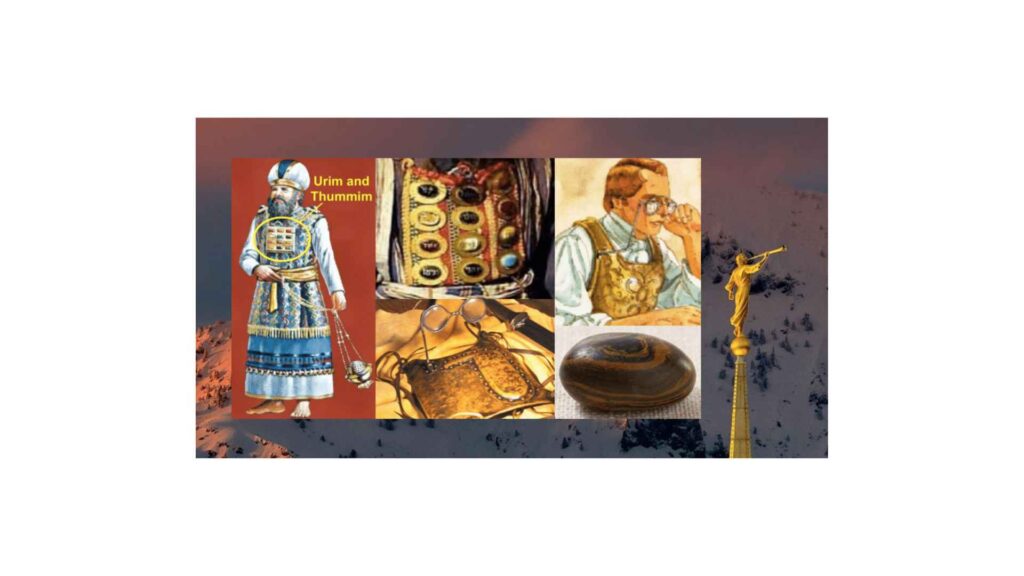

The Interpreters

The interpreters. While I don’t have time to get into the details in this brief discussion, I theorize that perhaps the interpreting stones that Joseph received from Moroni were not, in fact, the same stones that the brother of Jared received from the Lord on Mount Shelem. Now, I’m not arguing definitively that they’re not, but I’m suggesting that they might not be, and I offer answers to what I think are all the primary objections on this point. Instead, I wonder if Mosiah or some other Nephite likened Mesoamerican divining tools to the brother of Jared stones after Mosiah translated Ether’s record. Similarly, Joseph would have initially likened the Nephite stones to his personal seer stone, as well as the appearance of 19th-century spectacles.

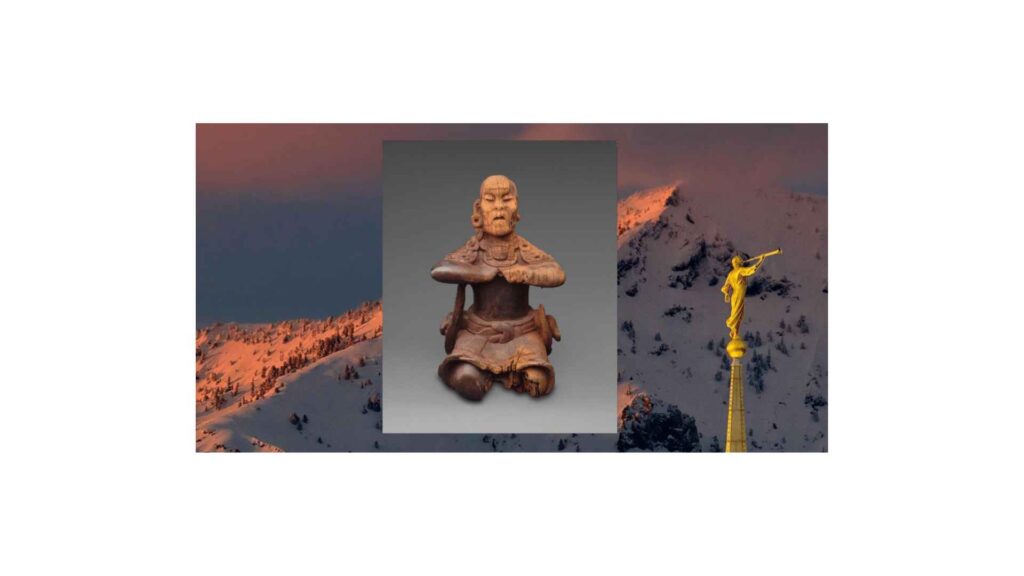

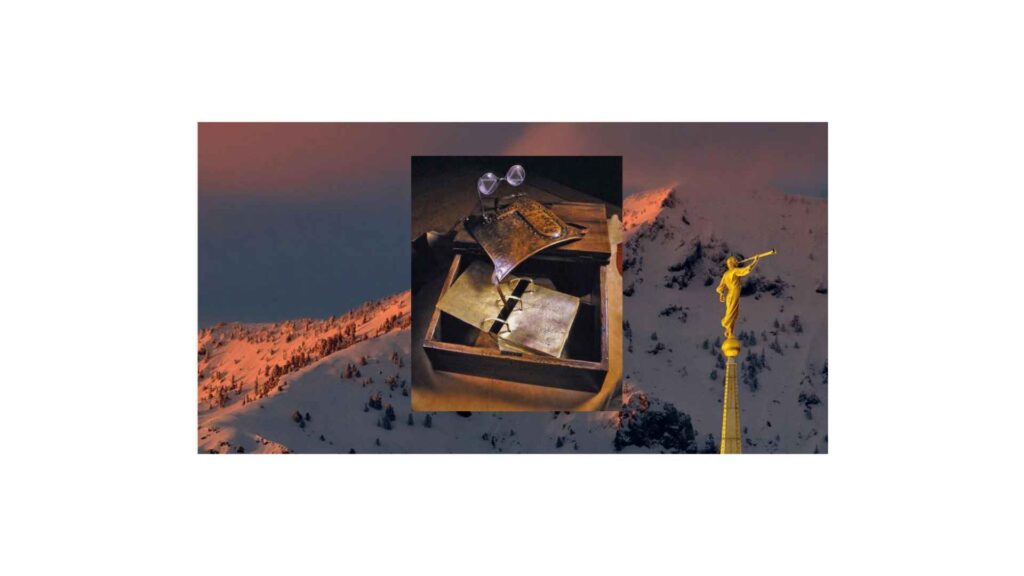

In his book “The Lost 116 Pages,” a book I highly recommend, by the way, Don Bradley offers one of the newest theories about what the Nephite spectacles might have looked like. While I accept most of the arguments in Bradley’s book, we part ways on a few points on the interpreters, and I explain why in my book. I believe the interpreters find a comfortable home in a Mesoamerican environment. They fit the shape, size, translucency, shining qualities, bundling, and function of what we find in ancient Mesoamerican diviners.

Ritual Bundling

Of all the many ways in which I believe the interpreters fit with Mesoamerican diviners, I’m limiting the discussion to this: Mesoamerican cultures often engaged in the ritual bundling of sacred objects. While classic Maya art typically depicts bundles of cloth, some bundles containing books and community documents were occasionally stored in wooden chests or coffers, and some classic Maya art even depicts bundles as wooden boxes wrapped in textiles. Likewise, the Book of Mormon and the interpreters were bundled or enclosed in the stone box.

One early American account refers to the content’s sacred bundles containing the heart of God the Father, a bead of precious stone. Sometimes the bundles were described as wrapped in fieriness of heat, or a bundle of flames—an interesting description, since both the Israelite Urim and Thummim and Mesoamerican diviners are sometimes equated with fire. The Nephite interpreters in the Book of Mormon we’re told would shine into the darkness.

Bundles could also be understood as Mesoamerican codices or books written on bark paper skins and that opening a bundle was like opening a codex.

Why did the early Americans bundle some of their sacred belongings? A wrapped object was protected, sealed from profane handling or view. The contents of the bundle, observes Karen Wenz, could be made sacred or sanctified, made wholly and elevated to a special status by the very act of bundling. Both wrapping and unwrapping a bundle have significant ritualistic implications. The bundle, explains Carolyn Tate, was understood to be both protective and secret, and the unwrapping ceremony was often calculated to denote political or religious control.

Unwrapping

To quote Julia Guernsey and Kent Riley,

The act of wrapping not only veiled objects but also enhanced their sacredness through concealment. Conversely, the unwrapping of a bundled object or monument was an act of discovery and disclosure. At times, it appears to have been metaphorically equivalent to opening a portal to cosmic realms.”

In the ancient Near East, seals were broken when it was time to expose or legitimize the purity of original contents in a document. The breaking of such seals was sometimes reserved for the end of times. Likewise, ancient Mesoamericans were not at liberty to unwrap the bundle at any time they wanted, and their ritualized opening of bundles was the only possible access to the contents, which meant that the unveiling constituted a major ritual event.

Sacred bundles symbolized a group’s identity, explains Wenz, and served as symbols of the group’s predestined ascendancy as well as their lineage. The sacred bundles of the Mixtec royal house of Tilantonga, she notes, functioned as a symbol of communal identity and as an ancestral bundle. The Nephites likewise had the sacred artifacts that linked them to the founding fathers, to Lehi, the Israelites of the Old World, and Joseph of Egypt. Moreover, those artifacts and records were not only religious in nature, but political signs of their authority and kinship.

The wrapping and unwrapping of the ancient American bundles were likewise conceptually linked to rulership rituals. The sacred bundles of the ancient Maya, explains Wenz, also tend to appear in situations or states characterized by transition and transformation, where they function as agents in negotiating between the natural and the supernatural realms, between myth and history, and between ancestors and the living.

Sacred Bundles

Sacred bundles, Julia Guernsey notes, established direct communication with gods. While sacred bundles may have been used at various times and for multiple reasons in Mesoamerican history, bundles were often given to humans, Wenz points out, at the dawning of a new age or during a clear transition from an old era to a newer era. Mesoamerican art sometimes depicted the opening of a sacred bundle. During the onset of a new era, in such art, the bundles appeared to explode, scattering ashes in all directions. Documents from the Inquisition, notes Wenz, recount the trepidation with which indigenous people responded when sacred bundles were opened.

So likewise, the Nephite plates were not to be unveiled to anyone at any time but only to be openly handled by the prophet like a Mesoamerican shaman, and unveiled to others, in our case, the witnesses, and only according to specific, pre-designated ritual events.

Necessary Timing

The Book of Mormon, like Mesoamerican bundles, was also opened in a time of crisis, in a new era, a time of restoration of all things that had been lost, when divine authority needed to be restored, and a time when a sacred lineage, in this case, the gathering of Israel, needed to be re-established. It should also be noted that according to Mesoamerican myths, as well as Mixtec codices, sacred bundles were often delivered not only at the beginning of new eras, but were brought from heavenly deities, primordial ancestors, or founding patriarchs. So likewise, the translation of the Book of Mormon was the first step in gathering or uniting God’s covenant people.

One of the significant things I discovered while doing my research for this book was the importance of remembering in the Book of Mormon. I made this discovery on my own, independently from any author who might have influenced my thoughts and conclusions. But I discovered, after I finished my first drafts, that my thoughts were not ideas that were totally unique, that at least some other LDS authors had thought of some of the same things.

Covenants and Remembering

In the scriptures, remembering and forgetting seemed to be connected to covenants with God. Those who remember God are part of God’s covenant people; those who forget God are not. Interestingly enough, one of the Hebrew words that connects remembering and covenant also denotes a record book. So likewise, the Old Testament Book of Daniel tells that those who are found in the Book of Remembrance will have everlasting life, while those who are not in the book, won’t have everlasting life.

When God made his covenant with Abraham, He told Abraham to sacrifice an animal, cut it into pieces and let the smoke from the altar pass through the pieces. The verb which refers to the passing of the smoke is the Hebrew abbar. The verb means to pass or cross over, but can sometimes be used in a similar way to cut. Thus the smoke cutting through the pieces represented a symbol of their covenant. Cutting in covenants are also present in the dividing of sacrificial animals, as well as the covenant of circumcision which memorialized or remembered the covenant God made with Abraham.

In the Jewish encyclopedia we read that the cutting of a sacrificial animal into two parts between which the contracting parties pass, shows that they are bound to each other. Thus they are symbols of the covenant relationship.

It is interesting therefore to note that the greek word symbolom, from where we get symbol, originally referred to a clay seal that was broken in half, a divider cut into two pieces. One half was given to each of the two parties of a contract.

Reuniting

So the root behind symbol means to bring together the two pieces that were once broken apart. Greek literature suggests that this breaking apart and reuniting is like a parent and child who are separated and reunited, and that reuniting is often expressed with a hand clasp or embrace. The hand clasp and embrace, writes Todd Compton, perfectly express this concept of two separate halves coming together to create a unity.

Not only does the cutting, dividing, draw attention to the ultimate reuniting, becoming one, a covenant unity, but the act of moving, crossing over for one piece, to a united peace, also signifies a covenant boundary crossing from one identity to another. Or in our case, crossing a boundary to become part of God’s covenant people.

After Moses’ death, when the Israelites crossed (again the Hebrew word abbar) the Jordan River into the promised land, Joshua commanded each of the 12 tribes to gather a stone from the Jordan River. This would be a sign to remember what the Lord had done for their boundary crossing from their previous home to the land of promise. Thus to the Israelites, cultic memorial objects arouse divine remembrance for subsequent generations who can also remember the covenant relationship.

When we take the sacrament we ritually remember Christ and the covenant to keep his commandments. We recommit to our boundary crossing by taking Christ’s name upon us. There’s a name change going on there, and to commit to change. We recommit to our baptismal covenants, which involved, according to Paul, becoming new creatures or having new identities.

The Scriptures as Books of Remembrance

The scriptures are in a way, books of remembrance, or books that remember God’s Covenant with his covenant people. I believe that the scriptures can generate a binding or sealing power that mobilizes the desire and resolve to unite with God’s covenant people and helps facilitate the ultimate divine conversion process. The scriptures are tokens, or God-recognized memorials, records of the divine memory of the ancient-modern covenants that make up his covenant people. By reading the narratives under the guidance and influence of the Holy Spirit, we ritually remember, internalize or memorialize, the promises made between our ancestors and God, as well as the covenants we make with God.

The power of scripture, the secret sauce that makes them different from other books is the fact that they are divinely sanctioned, made holy to serve as consecrated narratives. Other books can make you feel good, inspire you or relate uplifting stories, but only through the scriptures can we ritually remember our covenants, actualize the promises and blessings in our life, transform our souls, and unite with the Divine Family.

Doctrine Covenants 59 says that those not found in the book of remembrance are cut asunder. A covenant is separated by cutting. To cut asunder is to be outside of the covenant. When the covenant memories documented by the Nephite prophets to the symbolic and literal converting and likening of those Nephite memories into a renewed covenant for the Latter-day Saints, The Book of Mormon is sanctified.

Cultural Memory

Just as plain bread is made holy by the priest who asked a blessing upon it in sacrament prayers, I believe The Book of Mormon was made holy through the translation process of God’s 19th century prophet so that his covenant people could be united. I believe that the Book of Mormon, more than any other book, not only helps restore the ritual memory of God’s covenant people but can initiate a spiritual aspiration to unite with God and His covenant people.

Narratives are the records of our in-group, our covenant- making events, and our rituals.

As Agnes Heller explains,

As long as a group of people maintains and cultivates a common cultural memory, this group of people exists. . . . Whenever cultural memory enters into oblivion, a group of people disappear, irrespective of the circumstance whether they will or will not be recorded in the books of history. . . . Presence or absence, life or decay of a people does not depend on biological survival of an ethnic group, but on the survival of shared cultural memory.”

The covenant people of God exist because their cultural narratives are recorded in the standard works. Without the scriptures we would not know of past covenants, rituals and prototypes. The Mulekites didn’t bring scriptures with them and they forgot any covenants they might have previously made with God. The Lord told Nephi that if he wouldn’t have acquired the brass plates their nation would dwindle and perish and unbelief. King Benjamin said that if not for the brass plates they would have suffered in ignorance, not knowing the mysteries of God. Alma said that the brass plates enlarged the memory (we see again a covenant connection memory) of His people and brought them to the knowledge of their God and unto the salvation of their souls.

Memory Connetion

We see the memory connection here again, and note the memory and covenants often go hand in hand in the scriptures. Without scripture we will lack the cultural memory needed to bind us to previous members in our in group, and we lack the ritual memory, covenants required to bind us to God the rest of God’s covenant people.

Joseph had been told that part of his prophetic role included the charge to gather Israel, which I interpret to mean gathering God’s covenant people. In 1830 God told Joseph that he was called to bring to pass the gathering of mine elect. When Moroni first appeared to Joseph he said that the covenant which God made with ancient Israel was at hand and to be fulfilled, and the angel quoted several scriptures scriptures which foretold the gathering of the elect.

Likewise, in Third Nephi, we are told that the coming forth of the Book of Mormon would be a sign that the gathering of Israel had begun. On 22nd September, 1827, the very day that Israel celebrated the Feast of the Trumpets, Moroni gave the golden plates to the Prophet Joseph Smith and the feast of the trumpets is often seen as a symbol of the gathering of israel. When Joseph translated that covenantal memory narrative in the Book of Mormon, it opened the door for a covenant renewal in the current dispensation.

Remembering the Abrahamic Covenant

According to its title page, the Book of Mormon was written to the Lamanites, who are remnant of the House of Israel, and also the Jew and Gentile, to show, remind, the remnant of the House of Israel what great things the Lord hath done for their fathers, and they might know the covenants of the Lord; that they might not be cast off forever. The record was written, preserved. and translated so the remnant of the House of Israel, as well as the Jew and the Gentile, could remember the Abrahamic Covenant that would be brought into the same fold.

Some Mesoamerican scholars likewise believe that Mesoamerican shamans not only use shiners to see things of a spiritual nature but they believed that this divine scene united them with past ancestors. The Old Testament urim and thummim served as a memorial to arouse divine remembrance which helped maintain the eternal covenant relationship between God and his people.

I believe that Joseph’s Urim and Thummim, the interpreters, and the seer stone, invoked memories of the Divine Covenant record of God and His people as recorded by the Nephites. The translation of this covenantal narrative in English was the opening of a sacred bundle, a 19th-century Ark of the Covenant, wherein sacred memorial narratives were not only restored but caused the gates of sealing power to crack open. The earth was about to be flooded with the power and authority to gather God’s covenant people. Translated, the Book of Mormon set the restorative wheels in motion and paved the way for the priesthood that would eventually bind God’s people as one.

Covenant People

In D&C 84, known as the revelation on the priesthood, God commanded that a temple be built in Missouri, the New Jerusalem. He also noted the genealogy of the priesthood from the sons of Moses to Adam and reminded the saints that under Moses’ leadership, the Israelites hardened their hearts. God was calling to remembrance the line of priesthood authority and how things changed when the Israelites were wicked.

Then God reminded the 19th-century saints that they were now part of the covenant people, as in D&C 84.

Those who joined the Church and obtained the priesthood become sons of Moses and are bound to the same covenant people as those in the days of Moses and Abraham. Through this process of covenantal remembering, new members are changed, or sanctified by the Spirit unto the renewing of their bodies, as we read in D&C 84.

The Lord then pointed out that the saints in the newly restored Church were under condemnation. Apparently, like the children of Moses, they had hardened their hearts. The saints had treated sacred things lightly, and they were doomed to remain under this condemnation until they remembered the new covenant.

Here’s where we see the two principles closely tied together: they must remember their covenants with God. What was the new covenant they must remember? We’re told it was the Book of Mormon.

Renewing the Covenant

Translating the Book of Mormon initiated a renewal of the covenant that God had with His people. That covenant was actualized by the ritual remembering of the divine narrative, which is precisely what Joseph did when he translated the plates. Shamans and prophets apparently see what God wants by ritually connecting, uniting, and remembering their ancestral people, the covenant people in the case of the Bible and Book of Mormon and other scripture. God’s people share a sanctified narrative that binds them to each other and God.

The meaning of translate and covenant are related; both move something from one condition to another. Just as covenants are tokens of conversion, I believe that the Book of Mormon represents a covenant, the new covenant per D&C 84, that not only converted people to Christ, but converted the ritual memory of the Nephites to an English narrative.

The Book of Mormon translation process, I believe, was a ritual performance of actualizing a covenant memory, the covenant memory contained in the Book of Mormon. The use of the seer stones, Urim and Thummim, the unbundling of the plates, the ritual remembering of what the Nephites had written, all were partial to the enactment of a ritual covenant that bound the covenant people of the ancient New World to the covenant people of Joseph’s dispensation.

So likewise, the translation of the Book of Mormon ritually opened, sanctified, and shared the Divine Narrative. Modern members of God’s covenant people are now given the opportunity to ritually remember the Divine Covenant, just as the sacrament ritually remembers our baptismal covenant. We do that by reading, studying, and internalizing the Book of Mormon through the guidance of the Holy Ghost. Thank you.

Audience Q&A

Scott Gordon:

Thank you, thank you, Mike. As always, your talks are enlightening, interesting. So a few questions here. It says, I can think of many examples of Joseph Smith or Nephi or New Testament authors using previous scriptures in ways that didn’t necessarily match the original intent. Can you give a few examples of Old Testament writers doing this with earlier Old Testament texts that came before them?

Mike Ash:

That’s a tough one because, as I discussed in my book, I’m a believer in most of the scholarly literature on the Old Testament, that it was formed much later and probably based on oral traditions, maybe some scraps of written stuff. So really, it came, at least the Pentateuch, the five books of the Old Testament, came together much later and according to the cultural leanings of the time. It’s pretty hard to find things that are based on anything older because we don’t have anything older to compare it to.

Scott Gordon:

Okay, so if you believe Mosiah’s interpreters were different from the Brother of Jared’s interpreters, which set of interpreters did Joseph Smith receive?

Mike Ash:

Well, like I said, I have a long argument in my book that describes that. But we have to remember that obviously, it wasn’t necessary that he used the Brother of Jared’s interpreters because he ended up using his own seer stone for most of it. I think that was again part of God’s plan to help recontextualize both for the Nephites as well as for Joseph Smith. When he sees something that reminds him of the seer stone, that gives him that, I hate to use the word courage, but gives him an appreciation that God works through means that he already supposed that he did. It kind of validates that and that seer stones were going to give him divine revelation.

Scott Gordon:

How can we discern between a text’s human or cultural influence versus God’s influence?

Mike Ash:

Well, that gets into an entire thing about how do we understand doctrine. I actually have an article on the Fair website linked to all things on the LDS.org website on doctrine. It comes down to us; what we feel, that’s the only way we can know truth, any spiritual truth. We know doctrine when it’s confirmed to us by the Spirit. It gets a little bit tricky because I think that God kind of lets us work things out on our own as much as possible. I discussed this again in my book that I think he works through our inspiration and intellect. He’s not going to force-feed us; he’s not going to give us the answers to everything. This is all part of a test that ultimately changes our heart, aligns us with Christ.

Sometimes we have to put in our effort just as Joseph Smith had to put an effort into translating. It just didn’t all come to him. We have to put in the effort to sometimes understand what God wants as well, and sometimes it’s hard to do that. Right? So it’s hard to know.

I like what Brigham Young said about it. Even when we do get answers, sometimes it’s difficult to know what those answers really mean exactly. Which is tough.

Scott Gordon:

This is the second book that has been published through Fair. We are the publisher of it, and because this is the Fair conference, we are giving a discount for those people here at the conference. If you’re watching the conference and you order from the bookstore today, we’ll give you a discount as well. But it’s just for a short time period because this is a new release. It’s just out, brand new, new release. [To Mike] And you’ll be willing to sit out there and sign some books, correct?

Mike Ash:

Absolutely.

Scott Gordon:

Okay, so with that, thank you so much. Thank you.

Endnotes & Summary

Jeffrey’s talk, What Do We Treasure?, explores how different worldviews shape our understanding of the gospel and influence what we see as the “good life.” He identifies four primary worldviews—the Expressive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, and Redemptive Gospel—each defining success and fulfillment in different ways. While Expressive Gospel prioritizes self-expression, Prosperity Gospel equates righteousness with financial success, and Therapeutic Gospel emphasizes emotional well-being, the Redemptive Gospel teaches that true success is found in reconciliation with God. By examining these perspectives, Jeffrey warns that misplaced values can lead people to misunderstand the gospel’s true purpose.

The talk highlights how Gospel Counterfeits arise when cultural influences subtly redefine gospel vocabulary and shift the focus away from Christ. He provides examples of how phrases like non-judgmental love and authenticity take on different meanings depending on the worldview, leading to confusion and potential spiritual drift. Many individuals, even those originally converted to the Redemptive Gospel, gradually adopt cultural values while still using gospel language. This process results in a faith that, while still appearing religious, may no longer align with the teachings of Jesus Christ.

Jeffrey concludes by emphasizing the need for spiritual discernment and doctrinal clarity. While Gospel Counterfeits persist because they offer comfort, validation, or worldly success, the Redemptive Gospel calls for transformation through Christ. Faithful discipleship requires prioritizing God’s values over societal expectations, measuring spiritual success by personal sanctification rather than external achievements. By recognizing and rejecting distorted versions of the gospel, believers can ensure their faith remains rooted in eternal truths rather than cultural trends.

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 6, 2024

- Duration: 48:07 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2021 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: Mike Ash FAIR talk, Rethinking Revelation book, prophets and scripture LDS, Joseph Smith translation theories, Mormon apologetics revelation, CES Letter scripture errors, Mormon Stories Joseph Smith human element, Book of Mormon translation, seer stones and revelation, FAIR Mormon creative co-authorship

📖 Rethinking Revelation and the Human Element in Scripture: The Prophet’s Role as Creative Co-Author 1

Common Concerns Addressed

If prophets can be wrong, how can we trust anything they say?

Mike explains that while prophets are inspired, they are still human. Trust lies in the overall arc of revelation, not in isolated statements.

Is questioning prophetic counsel a sign of rebellion?

He emphasizes that faithful questioning has a long tradition in the Church and can lead to deeper conviction.

Apologetic Focus

Defending the Church’s revelatory process in a modern context.

Encouraging intellectual honesty and faithful exploration.

Showing that belief does not require absolute certainty.

Explore Further

coming soon…

Share this article