Summary

“The Life and Faith of William Paul Daniels” reflects on the remarkable life of William Paul Daniels, a South African, mixed-raced convert to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the early 20th century. His perseverance and faith were particularly notable as he sought priesthood ordination and temple blessings, which were restricted at the time due to his ancestry. His family continued his legacy of faith and community involvement in South Africa.

This talk was given at the 2022 FAIR Annual Conference on August 4, 2022.

Matthew McBride is a historian and writer, specializing in uncovering and sharing lesser-known stories from Church history. His recent work highlights the life and faith of William Paul Daniels, a Black South African convert whose unwavering devotion offers profound insights into testimony, belonging, and perseverance.

Transcript

Introducing Matthew McBride

Scott Gordon: Our next speaker is Matthew McBride, the director of the Publications Division of the Church History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He earned an M.A in American history from the University of Utah. Matt is the author of A House for the Most High: The Story of the Original Nauvoo Temple and co-editor of Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants.

His article on the origins of the women’s missionary program of the Church won the Mormon History Association’s Best Article Award for 2018. He was previously the digital content manager for the Publications Division and prior to that, Director of web development and Director of digital publishing for Deseret Book Company. With that, we’d like to welcome Matthew McBride.

Matthew McBride: Well, it is good to be here. But before I start, I need to ask all of you a favor. I’d like you to join me in welcoming my son, Benjamin McBride, who arrived home last night from the Pennsylvania Philadelphia Mission. He’s right over here. And I want to say thank you for supporting me in my fatherly duty to embarrass my children in public. How many of you have sons, right?

How many of you have read some or all of Saints Volume Three? Fantastic. Those of you who have not or are, I’m sure, all still lovely people and hopefully after you listen to Jed this morning, you’re ready to go dive in.

Matthew McBride

The Life and Faith of William Paul Daniels

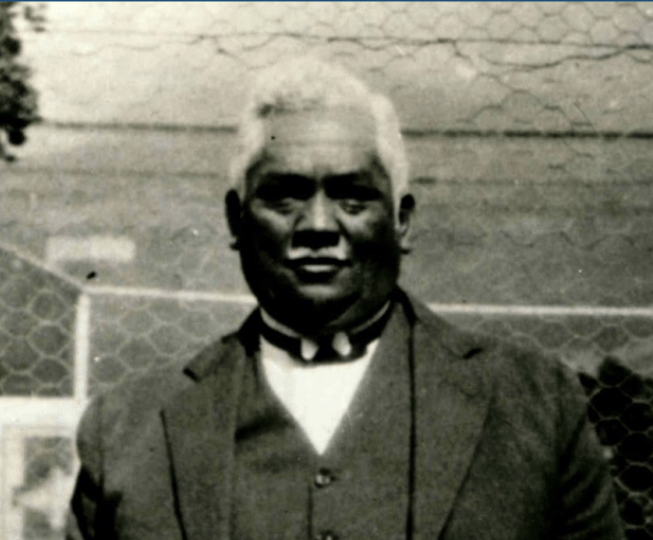

William Paul Daniels

I’m going to talk about somebody who we introduce in Saints Volume Three. I’ve come to know William Paul Daniels, who lived in Cape Town, South Africa.

He’s a person that I’ve come to love, admire, and respect. He was a colored man, and the term ‘colored’ as used in South Africa refers to people of mixed racial ancestry. So that is how I will use that word today in my presentation. I’m going to share Daniel’s story as a way of helping all of us reflect on the nature of Church membership and consequently, I think, on the aims of apologetics.

I recognize that I can’t speak for Daniels or any other person whose opportunities and life experience differ so drastically from my own as a white man. I only hope to amplify William’s voice. He left a substantial imprint on the historical record of the Church in South Africa, and I believe that his words and his actions have something important to teach us.

William was born in Stellenbosch, Cape Province, South Africa, in 1864.

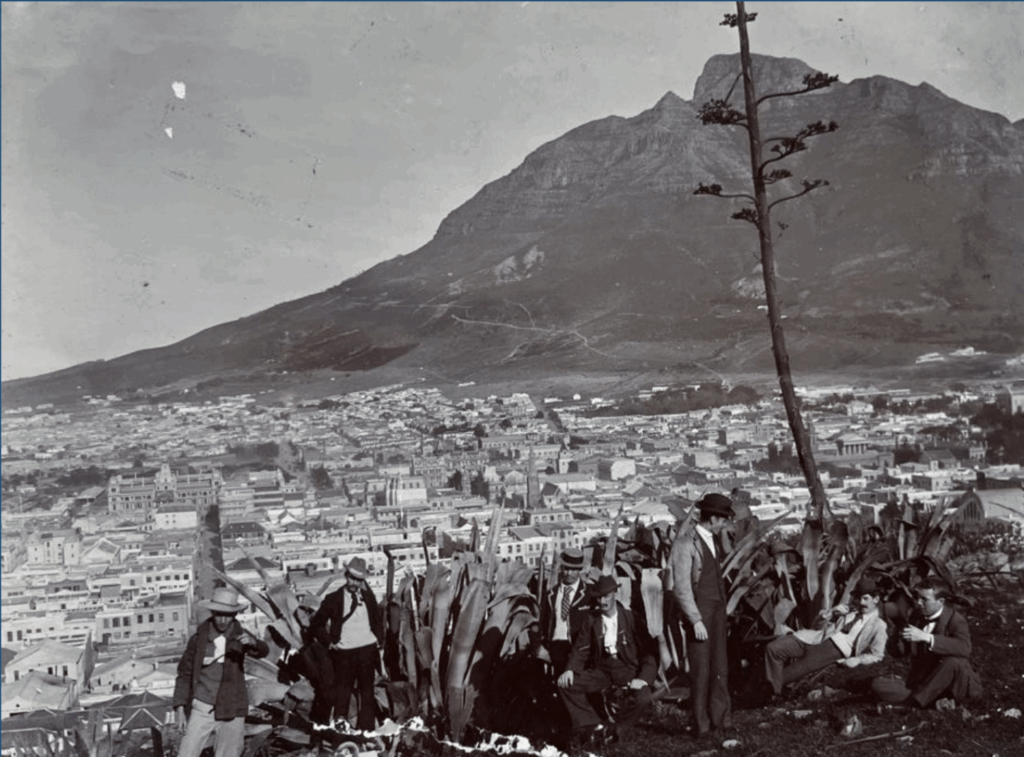

Early Life

So, this is a picture of his hometown about the time he was my son’s age. Here, in his early 20s, William lived in a society that was deeply structured around racial differences. It’s a legacy of Dutch, and later British colonization. He lived before apartheid, however, at a time when Cape Town’s large colored or mixed-race population had somewhat more social mobility than black South Africans had, or than colored or mixed-race South Africans would have later under apartheid, which firmed up and became the system of laws that we are more familiar with about 10 years after William Daniels died.

Daniels lived and worked among black and white South Africans. He was the owner of a tailor shop, a cab company, a farm, and a comfortable home. Like many mixed-race South Africans, he adopted European dress standards, etiquette, and leisure activities. He loved rugby and contributed to the founding of a sports park for colored people in Cape Town. William was raised Christian in the Dutch Reformed tradition but drifted from his religious upbringing while he was yet a young man, only to reprise his involvement in the NGK (the Dutch Reformed Church of South Africa) after his marriage to Clara Carrolls in 1893.

William was ordained a deacon and an elder in the NGK. He was in the NGK’s colored congregation that met at Saint Stephen’s church in Cape Town, South Africa, and valued the belonging and influence that his ordination and his participation in his congregation afforded him. At a certain point, he witnessed some behavior from his Minister that he deemed inappropriate and distanced himself again from church life.

Daniels’ Conversion

Around 1913, his sister Phyllis and her husband David, and then William’s son Abel, who was then a young man of about 13, joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and they moved to Utah. William declined his sister’s invitation to learn more about the Church, but over the next couple of years, the mission president, Nicholas J. G. Smith, who was also one of Daniel’s clients in his tailor shop, sent missionaries to visit with William.

William was impressed with the fruits of their faith, the way the missionaries paid their own way, and sacrificed two years to serve, all of which he felt stood in contrast to the corruption that he perceived in the leaders of his NGK congregation. At some point, the missionaries explained the priesthood restriction to William. This concerned him, and he asked the mission president, Nicholas G. Smith.

President Smith confirmed that Daniels was indeed ineligible for ordination because of his race. Now, weighing the positives and the negatives and what he was learning about the Church, he decided that he needed to visit his sister who again was in Utah, and so to investigate further, he traveled to Utah with his son Simon. Abel, of course, was already there. In fact, let me advance the slide here.

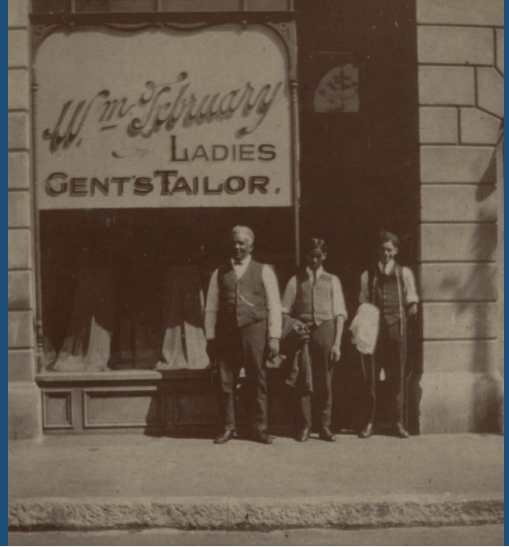

A Blessing and Promise

You can see a picture here of William, Simon, and Abel standing in front of William’s tailor shop in Cape Town.

So, off to Utah in 1915, an interesting time to travel on an ocean liner. This is around the timing of the sinking of the Lusitania, the beginning of World War One. But he heads off, to Clara’s dismay. While in Utah, he met with Church President Joseph F. Smith, I think hoping to see if there could be an exception made to the restriction. To William’s dismay, President Smith reiterated the restriction, also gave William a blessing and a promise that he would be ordained someday, be able to receive temple ordinances at some future time.

This promise evidently satisfied William, and he and his son Simon were both baptized in Clearfield, Utah, by the father of a former South African missionary. They stayed there for a few months, attended the ward in Clinton, and then he returned to South Africa that December with both Abel and Simon in tow.

Discomfort as a Colored Church Member

Upon returning and taking up life as a Latter-day Saint in South Africa, Daniels immediately felt the disparity between the belonging that he experienced as an elder in his segregated NGK congregation and the discomfort of participating in integrated worship as a colored Latter-day Saint. He was spurned by some of his white fellow congregants who made it clear that they did not want to be seen worshiping alongside a man with black ancestry.

Church membership alone was evidently not enough to overcome the racial divide that was so deeply embedded in South African culture at that time. William remained an outsider insider. He could not be ordained and thus participate fully as an equal to the other men in the Mulberry branch. He went to Clara, his wife, told her that he didn’t want to go to Church anymore, but Clara, who is not yet baptized, urged him to commit, especially after the lengths and the expense to which he had gone to investigate the Church in far away Utah. Well, Daniels did commit and he never really looked back.

Why Did Daniels Choose to Stay in the Church?

Now, if you’re like me, the first question that comes to mind is why did he choose to stay with the Latter-day Saints? We are inclined to assume that the strength of his testimony simply overrode all other concerns or discomfort, and there’s probably a lot of truth to that. And I do want to examine that question of why he stayed before I finish today, but first I want to take a few minutes with you to look at how he stayed, borrowing some concepts from social psychology and cultural anthropology to shed light on the social dimensions of William’s relationship to the Church.

Social scientists describe societies as being based on norms of reciprocity, the idea that people give to others and to their communities with the expectation of some kind of return. Now, our experience with modern economics has made us accustomed to thinking of reciprocity in exchange in purely transactional terms. I give you something and expect an immediate and commensurate return, usually in the form of currency, money. This kind of seller-buyer reciprocity effectively closes our relationship with the other person, and I no longer have an obligation and you have none to me, and we go our separate ways.

Now, the kind of reciprocity I want to talk about today is something that theorists usually call open or generalized reciprocity. It’s the concept that sometimes we give, not what the demand of immediate returned in kind, but with the trust social goods will be returned to us at some point in some form by someone. This kind of giving requires personal risk but it also forges relationships, it doesn’t close the relationship immediately when I hand you the five dollars in exchange for the thing I’m buying, creates a relationship. It creates Mutual obligation, it demands trust, it generates Social Capital, the social glue that binds communities together.

Bonding

Robert Putnam, and others have long recognized religion’s ability to generate bonding social capital. In fact, the word religion itself derives from the Latin word meaning “to bind together.” Some theorists like Emil Durkheim postulate that religion is really nothing more than an expression of social cohesion. I think we’ll see how William Paul Daniel’s story really pushes back on that I think, overly simplistic explanation, but the social fabric of kinship groups of communities, of religious organizations, and society as a whole is woven of this stuff, of this kind of open giving, and it’s it’s a more ancient form of reciprocity.

And while the more transactional mode has become increasingly important in modern times, generalized gifting in all its forms remains important to the social stability that we all crave. So let’s examine Daniel’s relationship to the Church through this lens. We’ll come to see his efforts as a kind of negotiation for belonging, for influence.

The poetic image from Ecclesiastes of casting your bread upon the waters and trusting that you will find it after many days, is an apt metaphor for William’s efforts to engage with and give generously of himself to the Latter-day Saint community in South Africa. Though the social returns were not immediate, they were far from commensurate for him and they didn’t come in forms that we might expect. Let me describe three aspects of William’s negotiation for belonging: his conspicuous devotion, his hospitality, and his creation of a Bible study class. We’ll go there.

Conspicuous Devotion

So first is his conspicuous devotion. Daniels very quickly became tuned to the social norms of the Church. He observed and understood the kinds of behaviors that were valued by this community, the type of devotion that garnered respect, that qualified one for leadership, and he excelled at every single one of those measures of Church activity.

At a Bazaar to raise funds for an organ for the new branch meeting house in 1920, and you can see that meeting house here, Daniel’s alone was responsible for raising more than half of the funds that were collected. He shared the gospel with his family and his friends, with the result that his friends, wife Clara, his daughter Alice, his son William Carl, and family friend Emma Bear, all joined the Church; not to mention of course Simon and Abel that we saw earlier.

William led all members in Cape Town in copies of the Book of Mormon given away to friends during a mission-wide contest in 1929. Don’t you just love these contests? There are like a hundred of them when you go back through the mission periodicals. This was the contest era, I swear. William, Clara, and Alice were three of only seven people in the entire mission that read the Book of Mormon twice during another such contest in 1931.

Very Engaged

Then in 1932, they and Emma Bear were the only members to complete both a private and a group reading of the Book of Mormon in Cape District, aside from the mission president and the branch president. Later that year, William, Clara, and Alice were listed among members in South Africa who had attended the most Church meetings during that year. (Again another contest.) Finally, the perusal of the Mowbray Branch minutes reveals that Daniels bore his testimony in fast meetings more frequently than most other members. It’s hard to imagine a more engaged Latter-day Saint.

So William was disheartened to learn that his brother-in-law, David, in Utah, had been ordained though he was far less actively involved in his Utah Ward than William was in the Mowbray Branch. David, his brother-in-law, according to William, was also of multi-racial ancestry and was passing as white. William expressed his frustration to mission leaders on a few occasions, in a way that shielded David from investigation into his racial background. William focused instead on the irony of his own ineligibility given his exemplary life and his Church activity.

Daniels’ untiring devotion was a powerful negotiation. It demanded that white members and missionaries reckon with their assumptions about their purported racial superiority. It even unsettled several mission leaders’ theological commitment to the priesthood restriction. Mission presidents from Nicholas G Smith to James Wiley Sessions to Don McCarroll Dalton queried Church leaders in Utah, on occasion, describing William, his faith, his situation, and asking about possible exceptions to the restriction, or seeking further clarification on its application.

Dalton’s letters in particular reveal a change in his own views during his three years as Mission President in South Africa. William Daniels and his family went from presenting an unfortunate problem to being, in Dalton’s effusive assessment, the foremost of the colored race, and pioneers. Dalton came to believe in Williams’ agency as a force for change in the Church, declaring in 1931 that he knew that by William’s diligence the barrier would be lifted and he would be a leader in Israel.

Hospitality

So let’s move on to the second aspect of Williams’ giving and that is his hospitality. And the gift that he gave to the Latter-day Saint community in Cape Town that’s mentioned most frequently in historical sources is food, it’s hospitality. By serving local Saints and missionaries hundreds of meals over the years, Daniel’s created a kind of table fellowship in Cape Town that complemented the pulpit fellowship offered by white Branch leaders.

Breaking bread together was one way of bridging the divides that the Church membership alone was not able to bridge for William at that moment. The meals were often lavish. One Observer called William and Clara’s cooking the acme of culinary art. Dozens of missionary journals attest to the sumptuousness of the feasts and the powerful bonds of fellowship that they created. A meal with the Daniels’ family became a rite of passage for new missionaries, a part of their initiation into mission life.

Daniels stood on ceremony opening every meal with prayer welcoming the missionaries, giving them advice, bearing his testimony of the Gospel. He insisted upon strict observance of British table manners, which was an uphill battle I’m sure with many of these young Americans. The ritual of the welcome meal also included a moment of hazing, I love this, where new arrivals were introduced to the Southern Hemisphere with a plate of penguins’ eggs. Only upon eating them did the Elders realize that they were nothing more than blancmange and glazed apricot halves, but watching the anxious new arrivals was great fun for Daniels and the more experienced Elders.

Hospitality and Fellowship

William and Clara’s table fellowship extended to to the white members of the Mowbray Branch as well, and on one occasion the Daniels fed a midday meal to all the children of the branch and then that evening, another meal which the mission minutes called a big brother Daniel’s style dinner that was served to 15 of the Saints as a send-off to President Nicholas G Smith.

William and Clara invited the missionaries to their home on other special occasions too. Of course on their birthdays, on New Year’s Day they always took special care to make the missionaries feel at home, borrowing a large American flag from a nearby military installation to hang outside on the 4th of July in his garden, or playing the U.S. national anthem on the victrola, or organizing a baseball game on their property.

William and Clara’s hospitality created obligations on the part of those he served. This sense of obligation gave William and his family an informal authority in the community. Though the restriction denied Daniels the formal authority of the priesthood and the right to administer the Lord’s Supper to his fellow congregants, William regularly stood at the head of his own table administering hospitality and fellowship. To nearly every missionary who came to South Africa for more than 20 years, his offering of food mirrored the sacramental authority of the Priests and the Elders, in this case, Daniels himself standing in the place of Jesus feeding the multitude.

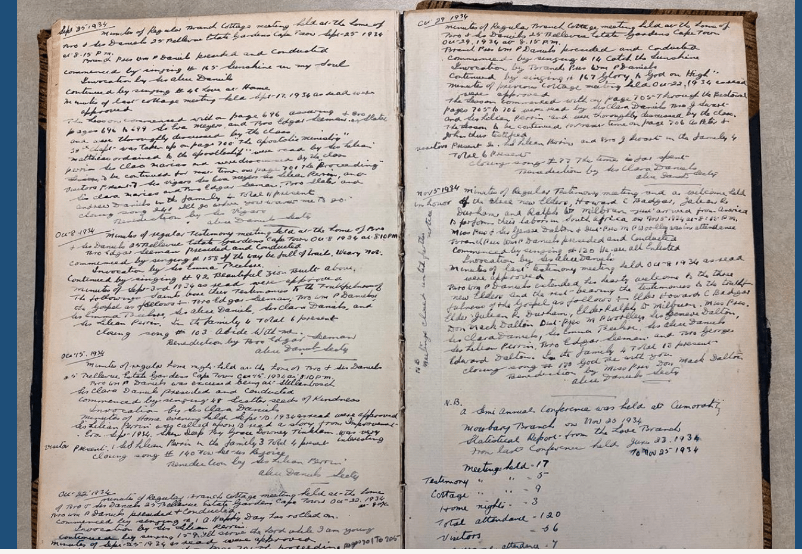

Home Bible Class

The third aspect of his giving is his home Bible class, and you can see here the minutes; I’ll talk about those in a minute. It’s a remarkable record that we have housed in the Church History Library in Salt Lake City. The minutes of the branch in Mowbray attest that Daniels himself did not let the inhospitable words and demeanor of white members in the branch deter him from attending meetings. But the disdain of some of those branch members was palpable, and the discomfort of Williams family members was real. William desired a space in which he and his family could worship with others who desired to have fellowship with him, black or white, or colored, mixed racial ancestry.

In 1916, he started a weekly Bible study class at his home. This is just within months of his baptism, and he invited the missionaries, the white Branch members, and other non-Latter-day Saint friends to attend this class. Now it was somewhat unique in the Church’s South African Mission, this class was, but Daniels likely participated in similar Bible classes when he was a participant in his NGK congregation.

By starting this weekly cottage meeting, as it was sometimes called, he created not only a safe setting for his family and friends to worship together, but a space in which he exercised influence and provided leadership. Over the years, the class became an institution in the mission, and though the meetings were often attended only by the Daniels family, the missionaries, and perhaps a few other colored members or friends, all of the mission presidents and more than a dozen different white Branch members from Cape Town attended intermittently over the years.

Minute Books

Eventually, the meeting gained greater institutional sanction; it was announced every week in the Mowbray Branch Sacrament services on Sundays. The mission newspaper encouraged attendance, saying that the meetings proved very inspirational to all who attend them and are a splendid means of better acquainting the members with the gospel, a beautiful endorsement. For more than a decade, Daniels ensured that his children took careful minutes of each Cottage meeting, and these minutes made the meetings official; they legitimized the Bible study class.

His minute books mimicked the Mowbray Branch minutes in form and content; they would read the previous minutes at the beginning of a meeting and approve them, they recorded attendance, they recorded who gave the prayers and which hymns they sang, which topics they studied, and often the words and the testimonies of those who were present.

That’s, I think, one of the most beautiful records that we have in our collection. William seems to have understood the importance of record-keeping in the church: “Whatsoever you record on Earth shall be recorded in heaven,” Joseph Smith said, and Daniels had a strong historical awareness. He insisted that these records should be kept and go down in Church history. He gave completed minute books to returning mission presidents so that they would take them to Salt Lake City and preserve them in the Church’s archives. These meetings were important enough to be recorded, preserved, and remembered.

Why Not Disengage?

Returning now to our social science lens for a moment, these theories of reciprocity and social exchange that I spoke of suggest that if over time we do not get reciprocation for all of our giving, that as human beings we disengage, and William did not disengage, as we have seen. What I described to you is collected from information that I’ve found in my research that extends all the way to the end of his life. On his deathbed, he was speaking with his daughter Alice to always be true to the Church, and his wife Clara as well.

Why did he not disengage? It’s certainly true that his love of the Church’s teachings and his spiritual experiences were an important part of the equation, but if we read the historical sources carefully, William tells us about social dimensions of his continuing engagement, the reciprocation that he perceived he was receiving from the Church as a community, and the interwovenness of personal spiritual experience and community belonging. They go together. Because of William’s hospitality, because of his Bible class, and all of his other efforts, he was welcoming members and missionaries into his home on a scale not experienced by most other Church members.

He often said things like he felt he was the richest man in Cape Town because he had the priesthood in his house, or that no person had the privilege he had in having the Lord’s representatives there. Having them here, of course, meant social interaction; it meant religious instruction, but it was more than that for William.

William knew that because of the obligation his own giving had created, he was now in a position to command their faith by requesting prayers on behalf of his family, his businesses, and his health. He especially prized blessings of healing because he had numerous health issues in his declining years. He asked members of his faith community to breach social decorum and lay their hands on his head to give them numerous healing blessings, which were at once spiritual experiences and reciprocal gifts from his religious community.

First Black Branch President

In November 1931, and we tell this part of the story in Saints volume three, President Don Mack Dalton formally organized the Daniels Family Bible class into a Church Branch. The creation of this Branch can be viewed in part as a way to quell growing concerns over integrated Worship in a South Africa that was marching full speed ahead toward segregation under apartheid at that moment.

But for President Dalton, and we know this, and for William, it was clearly understood as an acknowledgment of William’s faith. William was called as the first black Branch President in the Church. He remained unordained, so a rather unique situation, but he led the branch and he represented it in Mission leadership conferences.

Dalton’s rationale, this is from the minute book that we spoke of earlier, the minutes of that really sacred meeting, “Brother Daniel should have the privilege to perform a specific labor,” the irony being that William had been performing that labor on his own for 15 years. The creation of the branch, though integrated, what had begun as William’s gift into the Church’s structure. William’s persistent giving had at least partially disarticulated, or unfixed, some of those structures of inequality that he experienced.

Black Members in the Church

Now none of this excuses the frankly appalling way that William was treated by some in his branch, and it is not an apology for the priesthood restriction. The reality is that before 1978 and the revelation extending temple blessings and priesthood ordination to all regardless of their race, before that moment, vanishingly few black members in the Church had experiences like Williams.

Far too many disengaged. After more than a decade of activity, all three of William’s sons distanced themselves from the Church. You can imagine his pain. We all have experience with loved ones who do that, or most of us probably do. It’s telling that when missionaries later interviewed them, his sons declared that their belief in the Church’s teachings had never waned and remained intact, that they felt there was no place for them in the Church’s community, and this is tragic.

William’s hope for full participation led him to probe at the fixity of the priesthood restriction. We can see him doing this as he escalates his questioning from missionary to Mission President to President of the Church later in life. He even resorted to contesting his own racial identity. His claims over the years were complicated and sometimes contradictory.

In his response to Joseph F. Smith’s reiteration of the Restriction in 1915, that I mentioned earlier when he visited President Smith and received that blessing and that promise, you can see Daniel’s tacitly acknowledging his black ancestry, but by the mid-1920s, he began to argue in letters that he was of French and Malaysian descent and had no evidence of black progenitors.

His genealogical claims were weak, and they were never accepted, especially in view of the phenotypical traits that identified him as black in the eyes of Church leaders. But it is tragic that Daniels and so many others saw this as a necessary part of their negotiation for belonging.

Testimony vs Social Acceptance in Church

Now, we’re accustomed to thinking of our affiliation with the Church as being secured mostly by means of our testimonies. Now testimony is a complicated word the way we use it. It’s a complex construct. We think of it as involving in one way or another, at some level, elements of intellectual suasion or practical lived experience, but it is most common for us to characterize our testimonies as the result of spiritual communication, Spirit speaking to Spirit.

The emphasis we place on testimony as our tether to the church becomes especially clear when someone’s affiliation or activity in the Church is at risk. We exhort them to remember their testimony or strengthen their testimony. We question whether they ever had a testimony after they leave. People who leave sometimes speak of having lost their testimony.

On the one hand, William Paul Daniels’ decision today to stay in the Church complicates those purely sociological explanations of religion, demonstrates the power of ideas, the power of theological reasoning, and above all, the transcendent experience of divine revelation, of testimony. And all of these played a powerful role for William, planting seeds of desire in him, spurring him to engage, to stay.

Social Aspects of the Church

On the other hand, his story, and the story of his sons, should also give us pause, give us pause to those who may be prone sometimes to discount the social dimension of our relationship to the Church, especially among those of us for whom the social aspects of Church membership function really effectively.

And for whatever reason, I’m one of those people; the Church works very well for me and my family socially. It’s wonderful. I guess I’m suggesting that I, and perhaps others here, aren’t in the best position, perhaps, to understand some of the challenges of being part of a community that isn’t functioning for us the way that we hope. We might underestimate the friction that our community sometimes creates that works against the spiritual conversion of our friends, even be dismissive of their struggles.

President Hinckley’s well-known formulation is instructive: Yes, members of the Church need to be nurtured with the good word of God, but they also need friends and a responsibility. And these two latter needs correspond to the bonding Social Capital, the belonging, the influence, and those other psychosocial needs a truly reciprocal relationship provides.

These needs are common to all of God’s children, and we belong to a religious tradition that believes in sealing human relationships for the eternities, in networked salvation, in building a Zion in which there are no poor. And I use that term to refer not only to temporal poverty but also to social spiritual poverty. Such a tradition has the wealth, the resources, and the doctrinal impetus to address the need for human connection.

Apologetics and the Life of William Daniels

Now, what does this story mean for the enterprise of apologetics? We often quote Austin Farrer: ‘Rational argument does not create belief, but it maintains a climate in which belief may flourish.’ This is one important way to help people stay in the boat, so to speak.

William Paul Daniels’ story, though, reminds us that our efforts to create a rational defense of the faith, while vital, are just part of this larger picture. Strengthening the tether of testimony will always be a crucial element in our efforts to minister. We need to do it in ways that recognize the interplay of the spiritual and the social, to do it in ways that are not at cross purposes with our objective to build a flourishing Zion community.

My hope is that we can devote some of our best thinking not only to DNA in the Book of Mormon or providing workable historical contexts for plural marriage — again, all of this being very important — but also how we can be like William Paul Daniels, cast our bread upon the waters, and contribute to the social fabric that binds us all together as Latter-day Saints. Thank you.

Audience Q&A

Scott Gordon:

Thank you very much for sharing that heartfelt and sometimes difficult story. Yeah, I know you said it, but just to re-emphasize it, what year was that Branch organized again or approximately what year?

Matthew McBride:

Fantastic. So William was baptized in 1915. From 1916 until the end of his life in 1936, he conducted these meetings, which began as the Bible study class, and then in 1931, five years before he died, the mission president Don McCarroll Dalton organized that into a branch.

Scott Gordon:

That’s amazing. And to think of him sharing his minute books all the time with the mission presidents, do we know roughly how many books he ended up sending there or did you tell me, are on the shelf?

Matthew McBride:

We have two minute books from this branch. And one thing I should have said that I didn’t say, at the night that the branch was organized, the mission president said, ‘I think it would be appropriate to call this the Branch of Love.’ And so when you go to the Church history library, if you look in the catalog, you’ll see two minute books. The first one was called the Mowbray Cottage meeting minutes, and the second one is called the Branch of Love minutes, or the Love Branch minutes.

Scott Gordon:

So with all the Bible meetings, meals, then branch presidency, did he ever find fellowship and acceptance from the white members of his area?

Matthew McBride:

That remained a struggle throughout his life. And I alluded, briefly, to this when I was talking or characterizing the attendance to those meetings. So the meetings are largely attended by William, his family, or other colored people in their social circles. But there are about, as by my count, about 13 people, who were white members of the branch in Mowbray who would attend the meeting on occasion, and showed that willingness to reach out, at least in that way. And as I mentioned too, it became really important for William, to be able to call upon members of the branch, missionaries too certainly, but also members of the branch to give him blessings. So we do have those instances where he is feeling that kind of reciprocity in that fellowship, but it’s maybe not where we would want it to be as we think about an ideal branch situation or an ideal situation for a Church member.

Scott Gordon:

Another question someone asked, do we know if his vicarious work was ever done at the temple?

Matthew McBride:

I think that’s a great question. So I mentioned that on his deathbed he encouraged his daughter Alice to remain faithful in the church. And although his sons did leave activity and did not continue to participate, his daughter did and his wife did. Sometime after William died, his daughter Alice met President McKay on a trip that he took to South Africa in the 1950s, shook his hand, we have a picture of that moment. She also had the opportunity to meet Spencer W. Kimball later. And she, working in conjunction with some former South African mission presidents and other former South African missionaries, ensured that in 1978, or after 1978, that William and Clara’s work were done in the temple.

Scott Gordon:

That’s wonderful. Okay, one last question then. It says, this is an amazing story. Why have we never heard of this guy? Any plans to publish this in more detail than we get in Saints?

Matthew McBride:

My answer to that, why have we never heard of him? Frankly, we just have not done a good job of telling black stories, and that’s the truth. And we, we just need to repent and do better. I would suggest if you want to see more stories like this and to get a sense of the experience, especially that, I think a lot of us are familiar with the Elijah Ables and the Jane Manning Jameses of Church history, early black pioneers. Green Flake has become much more well known in recent years. And then we often kind of then skip way ahead to 1978 and get understandably very excited about the growth of the Church in West Africa, for example, and love to tell the stories of William Billy John Joseph Johnson, and Anthony Obina in West Africa and the growth of the Church there.

We don’t, we don’t spend a lot of time talking about the black experience in the Church in between the pioneer period and 1978. And so what I’d encourage you to do is spend a little bit of time with the Century of Black Mormons database that was created by a professor, Paul Reeve at the University of Utah, which is a digital history effort to tell stories like Williams and Clara’s story. And that will give you a sense of some of the amazing stories of patience, of faith, and of sacrifice that exist. And we owe it to ourselves. We owe it to ourselves to know those stories. My hope is to contribute, and I’m working with Paul on this, to contribute a biography of William to that database. And in the meantime, I would suggest if you haven’t read Saints, to at the very least read the story arc, the chapters relating to William and his and his family in Saints Volume 3. We there also tell the story of Lynn and Mary Hope who were black members of the Church in, I believe, first Alabama and then Ohio, and it’s really interesting to see some of the similarities between their experiences.

Scott Gordon:

So, giving away my age a bit here, I was on my mission in Switzerland in 1978, and we had a very faithful brother who was African in the ward there. And I remember being in sacrament meeting when they announced and read the letter. It was the one time that brother, he jumped up in the middle of the sacrament and put his arms in the air and yelled, ‘Yes!’ in English. So, it was great, everybody thought it was wonderful. All the members embraced him and thought that was a wonderful thing.

Matthew McBride:

Oh, that’s great. And then, you know, I think it’s important too to go learn stories like this, right, because I think there are some resonances between his experience, and I think the experiences of a lot of Church members today.

We know that as all of us face challenges as Church members, and some of those challenges unfortunately sometimes reach a point where we start to question, or we start to want to disengage in one way or another. And so being able to really think carefully about all the aspects, all the dimensions of the experience of someone like William, who is in that kind of a position, I think, serves us really well in a lot of ways.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you very much for your time and thank you for your presentation.

Endnotes & Summary

In The Life and Faith of William Paul Daniels, Matthew McBride tells the remarkable story of Daniels, a South African convert who joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the early 20th century. Though priesthood and temple blessings were denied to him due to his ancestry, Daniels remained steadfast in faith, serving his community through hospitality, scripture study, and quiet leadership. McBride draws on historical records to explore how Daniels’ Christlike perseverance challenges us to build Zion and strengthen fellowship within the Church today.

📖 Books by the Speaker:

- A House for the Most High: The Story of the Original Nauvoo Temple

Matthew McBride recounts the rich history and spiritual significance of the original Nauvoo Temple, weaving together architecture, revelation, and faith. - Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants (co-editor)

This companion to the Doctrine and Covenants illuminates the historical and spiritual context of each revelation, enriching modern study.

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 4, 2022

- Duration: 44:24 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2022 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: Matthew McBride FAIR talk, William Paul Daniels LDS, blacks and the priesthood, Mormon Church history Africa, Nauvoo Temple history, Revelations in Context Doctrine and Covenants, CES Letter race and priesthood, Mormon Stories black pioneers LDS, Latter-day Saint history South Africa

Common Concerns Addressed

Why would someone remain in a church that denies them full participation?

Daniels exemplifies faith beyond structure, driven by community, doctrine, spiritual experiences, and hope.

Why haven’t we heard this story before?

McBride acknowledges the Church’s lack of telling Black Saints’ stories and encourages more awareness through projects like Century of Black Mormons.

Apologetic Focus

Faith and perseverance amidst injustice.

Historical context for priesthood and temple restrictions.

The importance of remembering and sharing underrepresented narratives in Church history.

Explore Further

coming soon…

Share this article