Summary

Neal Rappleye presents compelling research on ancient South Arabian inscriptions referencing Nahom (NHM) and Ishmael—both significant names from the Book of Mormon. Highlighting archaeological discoveries such as funerary stelae and dedicatory inscriptions dating to the 7th century BC, Rappleye contextualizes these findings within the cultural and historical setting of Lehi’s journey, offering insights into the historical plausibility of the Book of Mormon account.

This talk was given at the 2022 FAIR Annual Conference on August 3, 2022.

Neal Rappleye is a research project manager at Book of Mormon Central. He is actively involved in exploring the historical and archaeological context of the Book of Mormon across ancient Jerusalem, Arabia, and Mesoamerica. His work is published in BYU Studies, The Interpreter Foundation, and other platforms.

Transcript

Introducing Jeffrey Thayne

Scott: Our next speaker, Neil Rappleye, is a research project manager for Book of Mormon Central. He’s involved in ongoing research on many facets of the Book of Mormon’s historical context, including ancient Jerusalem, especially around the 7th Century BC, ancient Arabia, the ancient Near East, or broadly pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, and the 19th-century witness to the discovery and translation of the Book of Mormon plates. He has published with BYU Studies, The Interpreter Foundation, Book of Mormon Central, Greg Covert Books, and Covenant Communications. With that, we’d like to welcome Neil.

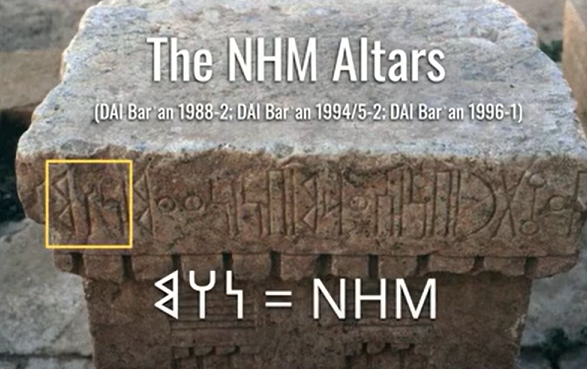

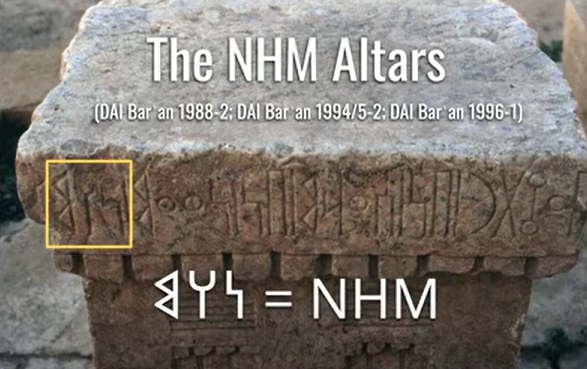

An Overview of the NHM Altars

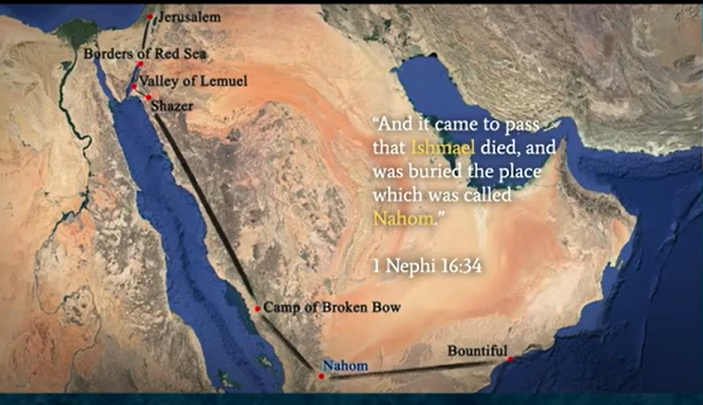

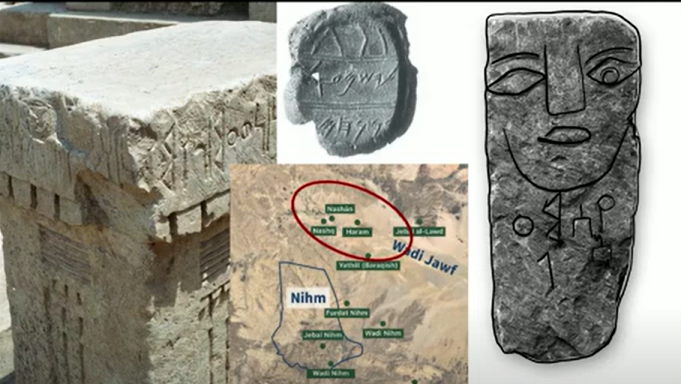

I’m going to be kind of assuming, based on my audience here, that you guys are generally familiar with the discovery a number of years ago of the NHM altars, so-called because they have the name NHM there on them, and you can see how that’s written there in South Arabia. And I just want to caveat here, ancient Semitic languages usually did not include the vowels. So, all that’s on these inscriptions is NHM, which can be interpreted as the name Nahom which is referenced here in the Book of Mormon as the place in which Ishmael was buried in 1 Nephi 16:34.

I’m going to be using the more common translation used by scholars, which is “Nihm,” and pronouncing it “N-him” because that’s how I understand locals tend to pronounce the name in Yemen. Nonetheless, there are a number of different spellings and translations that have been done, so just be aware the vowels tend to vary.

This is something, like I said, that’s been talked about before. I’m assuming most are familiar with it, but for the sake of those who may not be, we will just quickly review.

Kent Brown

Kent Brown came across this altar with this inscription when he was reading this volume, which is the French language catalog for an exhibit on Ancient South Arabia that was traveling through various museums in Europe in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

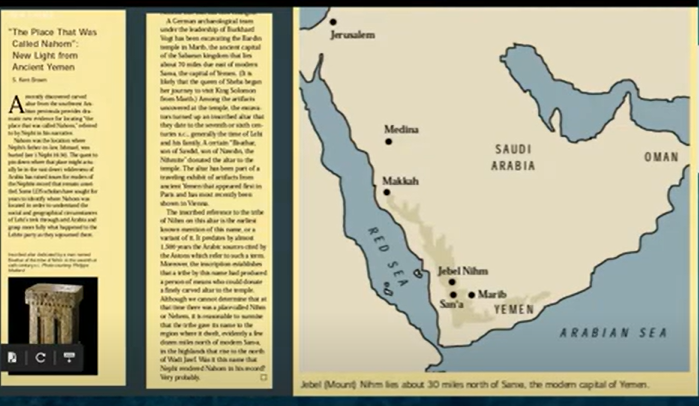

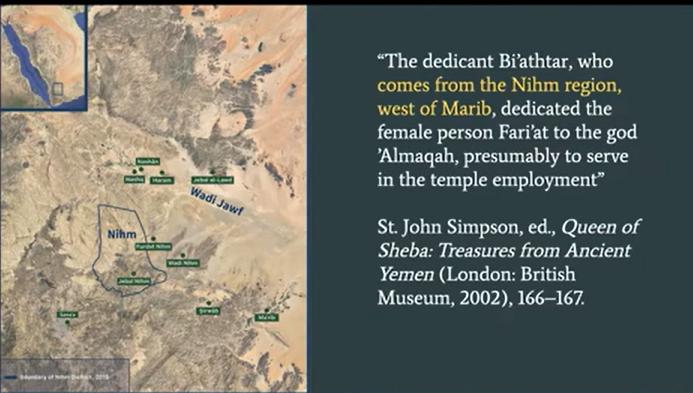

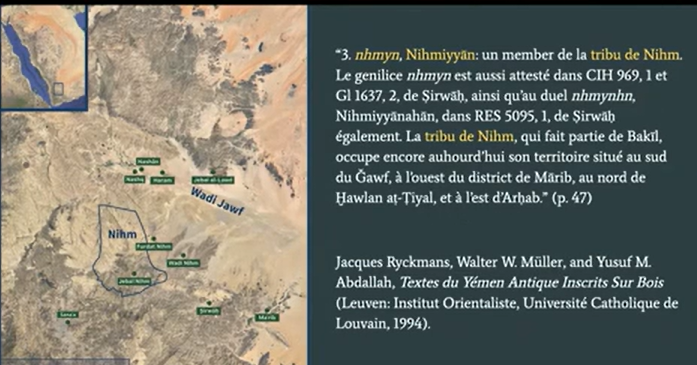

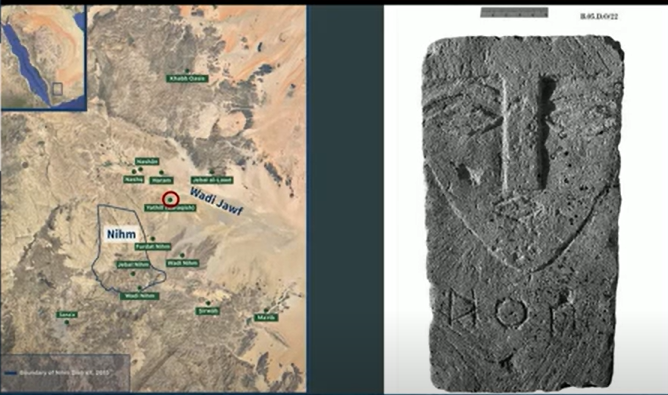

According to the commentary published there alongside the altar, which was written by the lead epigrapher on the German archaeological team that had excavated this altar in the first place, he said that the altar dated to the 6th and 7th Century BC and identified the author of the inscription as being from the tribe of Nihm, which was located near the Wadi Jawf Northeast of Sana.

There were also German, English, and Italian language publications because this was, like I said, touring throughout Europe at the time. These also featured the altar in their various publications, and they had slightly different commentary published with them that was written by another member of the German archaeological team that excavated these altars.

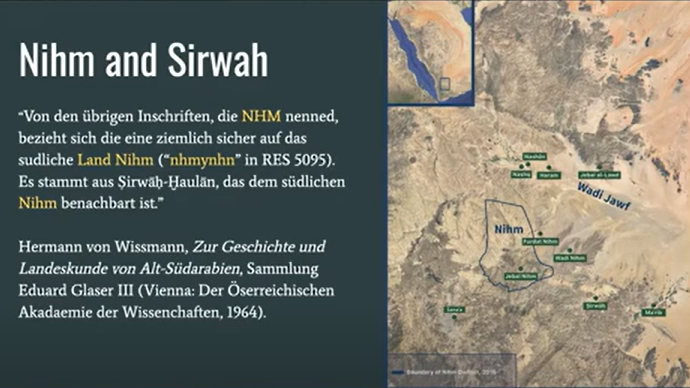

According to the commentary published in these, he said that this author or the dedicant of the altar comes from the In the Nihm region west of Marib, as indicated on the map. The map illustrates the general area of the Nehem region. The boundary I’ve marked represents the modern-day administrative district in Yemen, named after the Nehem tribe. It is a contemporary boundary, not necessarily reflective of historical antiquity or the full historical influence of the Nihm tribe in the region. However, it serves as a reference point. To the east, Marib is visible, and to the southwest, you should find Sana. In the north, Wadi Jawff is an important reference point, which we will discuss further in this presentation.

Nahom and Nhim

Before this inscription was published, Latter-day Saint researchers had already begun to associate the Book of Mormon’s Nahom with this tribal area of Nhim. In a 1978 article in the Ensign, Ross Christensen made the initial connection when he observed it on an 18th-century map. Warren Aston conducted additional research following this discovery, though he couldn’t trace the name back to Lehi’s day until Kent Brown found these altars.

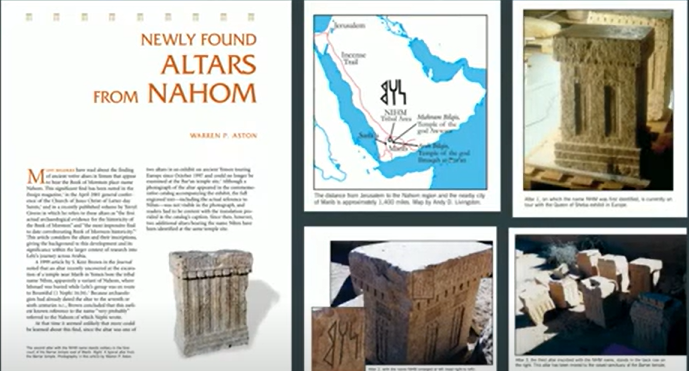

And in 2001 Warren Aston then wrote a follow-up article to Kent Brown’s article, published again in the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, providing more information about the altar and the inscription, and discussing the place of discovery along with its context. He also noted that there were actually two more altars with this same identical inscription that had been found at that same site. So, he gave kind of that update.

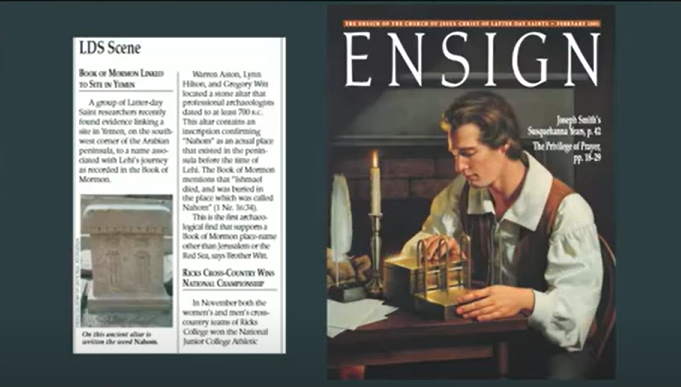

And this was even something that was highlighted in the Ensign in 2001, in the February 2001 Ensign. Just as a personal note, this is how I first heard about this discovery. I was in seminary, just kind of waiting for class to start one day, and my teacher, Brother Jones, came to the front and began class by reading this little note from the Ensign. You know, my little 14-year-old mind was just completely blown. And of course, because it was completely blown and I found it so fascinating as a teenager, afterward, I left class and didn’t think about it again for several years, because I was, of course, a teenager, but it did make an impression on me, and I remembered it several years later when I began to get more into this sort of stuff.

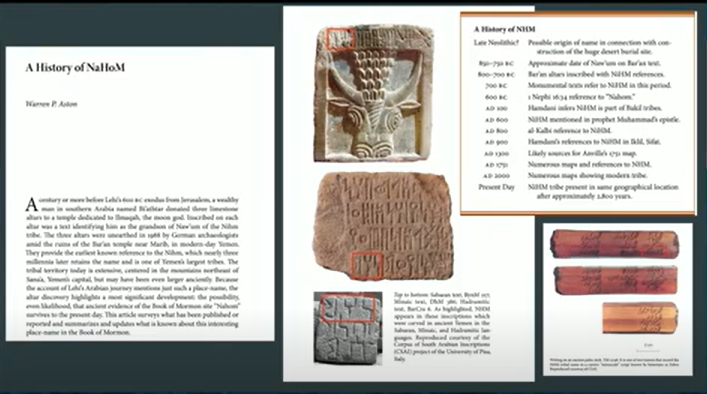

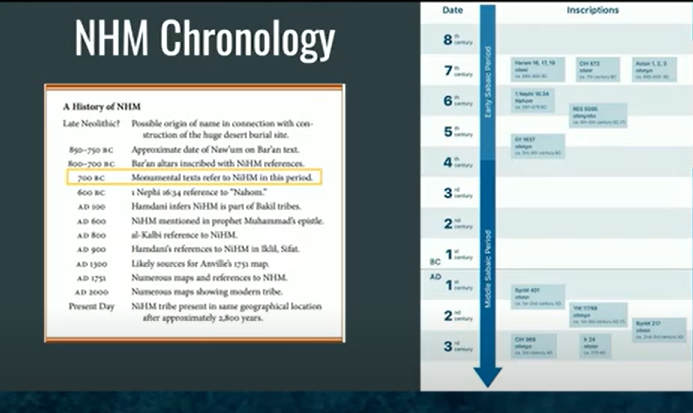

But it is worth noting there was this article that showed up in the BYU Studies Quarterly Journal in 2012, written by Warren Aston. It’s a very helpful summary of what had been done up to that point in research on this, and it also provided a couple of key updates. One of the updates being that the epigrapher for the German archeology team that excavated the altar had reassessed the dating of some of the inscriptions and dated this one back about a century to the early seventh or possibly late 8th Century BC. Warren Aston, also noted in this article, that there were additional inscriptions that mentioned the NHM name. You can see some of the images he published along with that. But he only talked about them very briefly. He’s mentioned them in some subsequent publications, but to this point, I find that a lot of people aren’t aware that there are some of these additional inscriptions.

Additional NHM Inscriptions

Which leads to the main purpose, the main event, if you will, for this presentation. When I first read about that from Warren Aston a number of years ago, I was kind of intrigued and it piqued my curiosity, so, I actually started looking up more information on some of these additional inscriptions and tracking down the various publications that have been made on them and so forth. Like I said, I’ve found that the existence of these additional inscriptions tends to be not well known by Latter-day Saints. We’re going to go over some of those just really quickly here today, and what I’ve learned about them up to this point. This is always, like most research, ongoing, and so I’m still learning more. Keep in mind, some of these thoughts are a little preliminary.

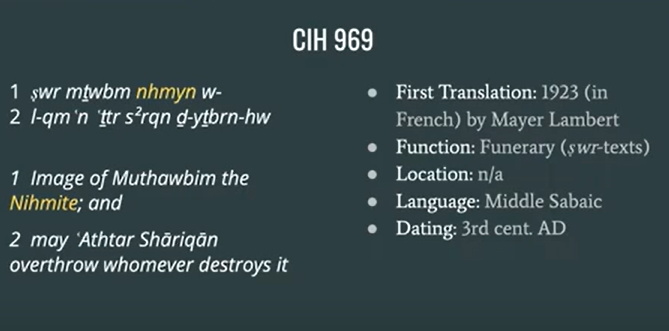

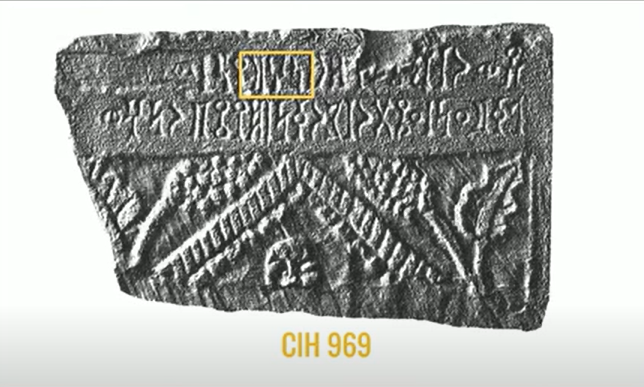

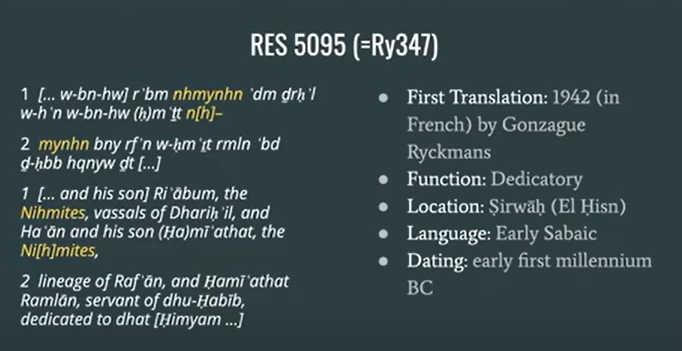

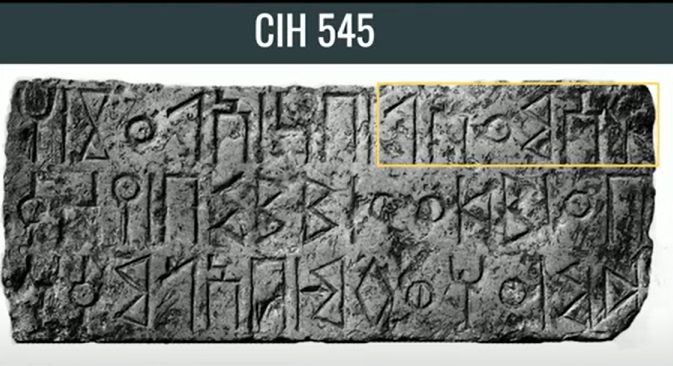

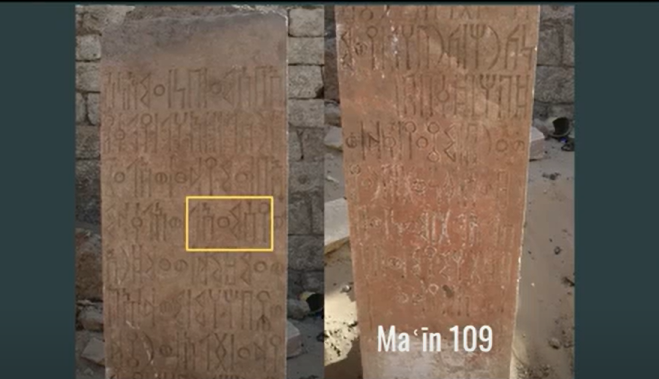

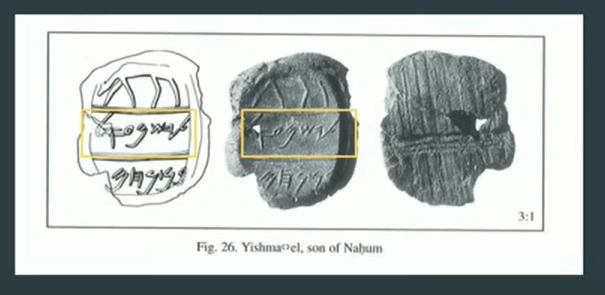

Let’s go ahead and dive in. You will notice, when I’m talking about these inscriptions, they’re often going to have these little codes with letters and numbers attached to them. These are just reference codes that scholars use to catalog these inscriptions and keep track of them, making sure everyone knows who and what they’re talking about. I’ve highlighted there where “nhm” shows up in this inscription.

This is actually a funerary stela or, a tombstone, if you will. It’s dated to the third century A.D and uses what scholars commonly call the image formula. It’s called that because the first word in the inscription is translated as “image,” and then it follows kind of formulaically with the name of the individual and their tribal or lineage affiliation.

Inscription Formula

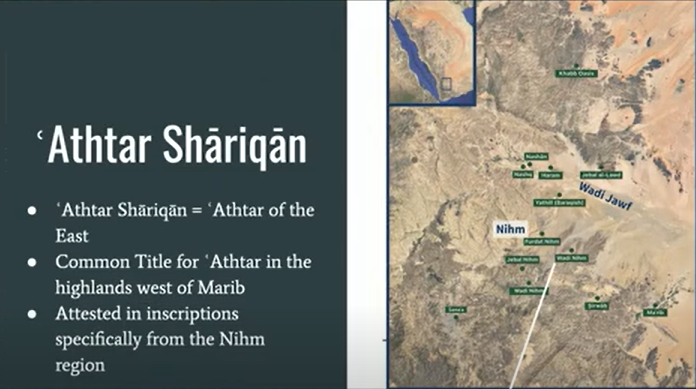

There are about 17 total known inscriptions that follow this formula. We’re talking about this one because it identifies the deceased as a Nihmite, and it also includes this curse. Some of them include a second line. Not all the inscriptions that have this particular formula will have that second line, but this one includes a second line with a curse that invokes the deity Athtar Shariqan.

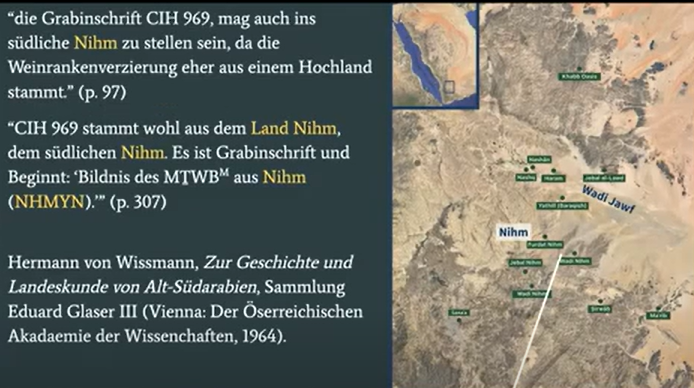

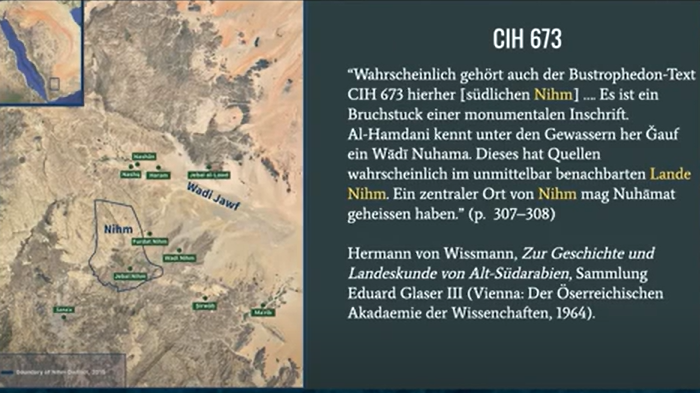

The German scholar Hermann Von Weissman was the first scholar to really seriously attempt to reconstruct the tribal geography of ancient South Arabia based on the various inscriptions, and he commented on this particular inscription, noting that it refers to Nihm. And so he believed it probably came from Nihm. Its actual provenance is a little uncertain. And his reason for associating it with Nihm, though, went beyond just the mention of the name there. He also noted that it had these decorative vines, that you can see, on the side of the kind of house rooftop there. You can maybe see those decorative vines there.

According to Von Weissman, that is a motif that is common in what’s called The Highlands area of ancient South Arabia. And you can see on the map, I’ve kind of drawn a line. Everything west of that line is what’s typically associated with or identified as the highlands because those are a mountainous region where elevations tend to exceed 2000 kilometers. And you can see Nihm is within and overlapping with this highland region.

More Inscriptions

Another detail that is consistent with that association is this reference I mentioned of Athtar Shariqan. The deity Athtar in South Arabia, was a Sabian deity that was primarily associated with the Sabian culture in Marib and Sirwa, which are down there in the heartland of Saba. When it was adopted by the western highland tribes, which are, you know, west of the Sabian Heartland, they referred to him as Athtar of the East. That’s what Shariqan means, is East. So this is a deity title that’s associated with that highland region where Nihm is. In fact, we have inscriptions right from Nihm that use this deity title. So this is another detail that would associate it with that region.

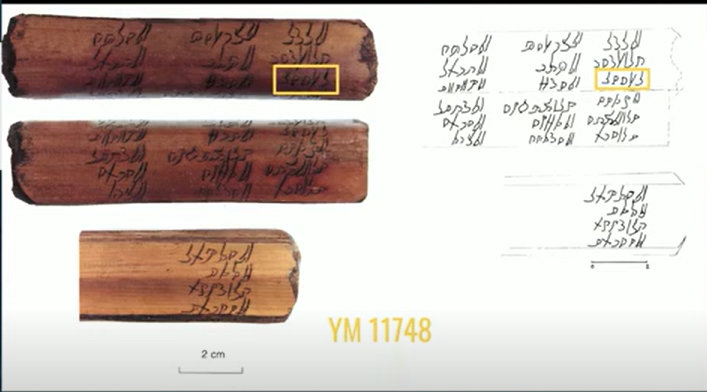

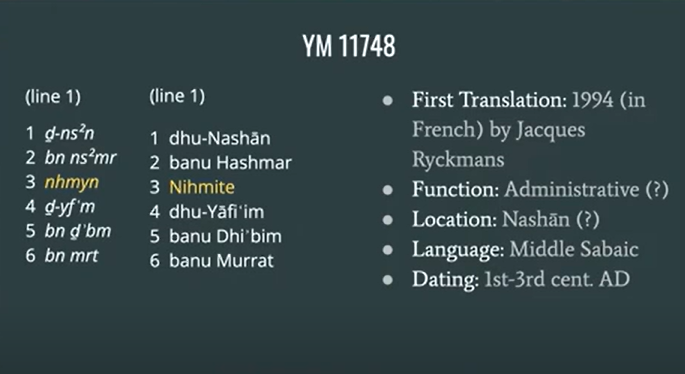

This next inscription is unusual for this particular group, at least because it’s not written on stone. It is written on palm stock. And there are actually several hundred South Arabian inscriptions written on palm stock. They use a different script, so it looks a little different, and it’s a little harder to read. But again, I’ve highlighted where it says Nihm there. And this text is actually just a long list of different tribes and lineages and things like that.

And I’ve only provided the translation and transcription here of the first line because that’s all we need. You can see right there on the third line, it mentions Nihm, or Nihmite, as one of the names on the list. And scholars believe this probably had some kind of administrative function. It was part of a larger collection of palm stock text that seemed to be administrative in nature that are believed to come from the site of Nashan, which is one of the city-states there in the Wadi Jawff. I haven’t been able to confirm a specific date for this inscription, but the collection it’s part of generally dates to the first through third centuries A.D., so I assume this one falls somewhere within that time range.

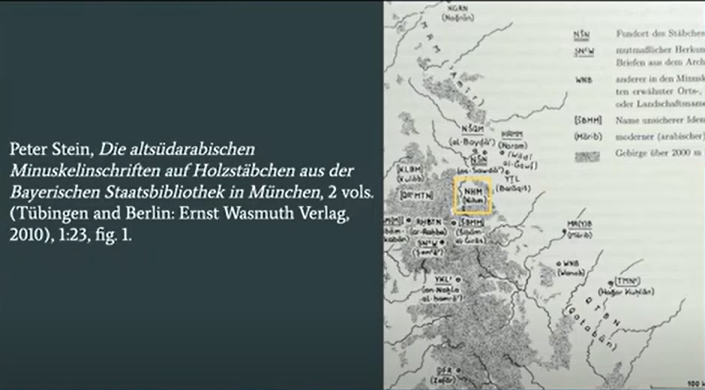

Then there’s this map that was published by Peter Stein, a German scholar who was studying the geographic horizons of the palm stock text. And so he included this reference to Nihm based on its reference on this list there on his map. Again, you can see, it’s a hand-drawn map, so it’s maybe a little harder to interpret, but it’s in the same position we would usually expect it to be.

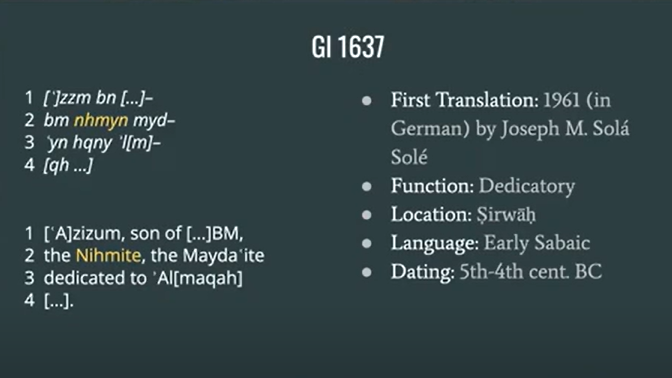

This was translated first in 1961 by a German scholar. It dates to the 5th or 4th Century BC, and it’s interesting because it’s the only one in this group of texts we’ll be talking about that has what’s called a dual affiliation. It identifies two groups that the authors associated with: the Nihmite group NHM and then the, I don’t know how scholars like to say it, but Maida or Mida tribe, a tribe located in Wadi Dana, which is the main Wadi near the city of Marib. This kind of dual affiliation is common in ancient South Arabia, but this is the only NHM one that I’m aware of.

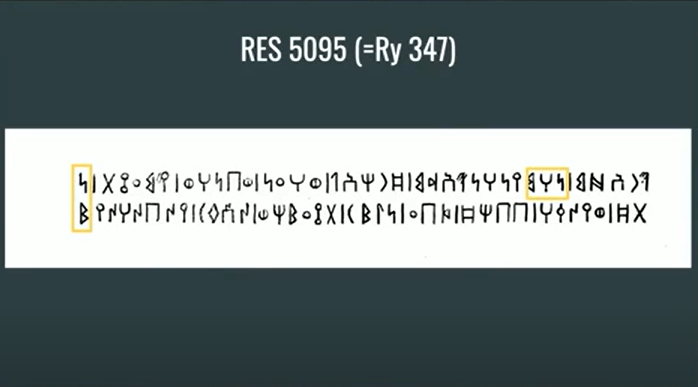

You can see the transcription there and translation. We don’t have a firm date on this text, but it’s believed to be from the early Sabic period, which is basically the early first millennium BC, no later than the 4th Century BC, but possibly much earlier. It mentions four different people who are associated with the Nihm region or tribe, all mentioned in a father-son pairing. The NHM name is actually a little longer because this is basically the dual form of the name, that’s to say, it’s like a plural but specifically refers to just two people, four people total in this inscription. It’s interesting to note that they’re all mentioned as vassals or servants in the area. That’s interesting because of the relationship between Sirwa and Nihm at this time.

Herman Von Weisman talks about how they shared a border between the region primarily controlled by Sirwa and the Nihm region. This kind of creates a link, but other scholars have noted that there’s inscriptional evidence suggesting that as early as the 6th Century BC, the Sirwa tribe actually ruled over parts of the Nihm region. It would make sense then why we find so many references to Nihmites as vassals or servants from Sirwa. They’re going there and making their dedicatory offerings as they’re kind of vassals there.

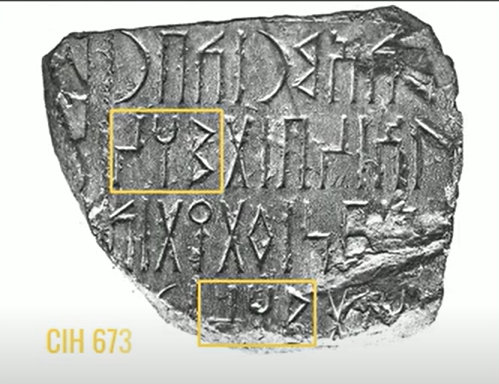

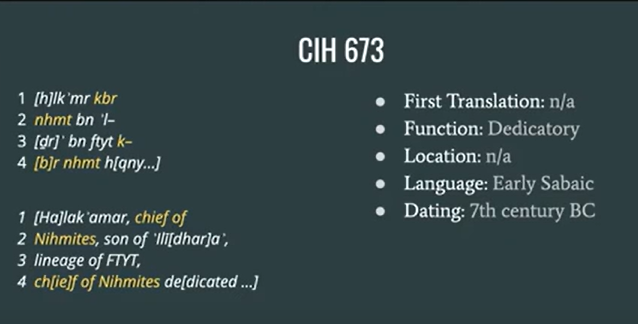

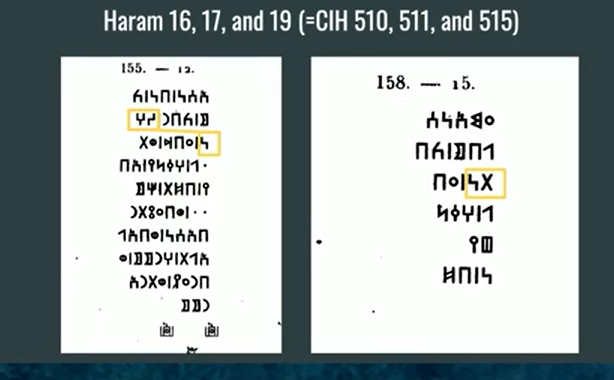

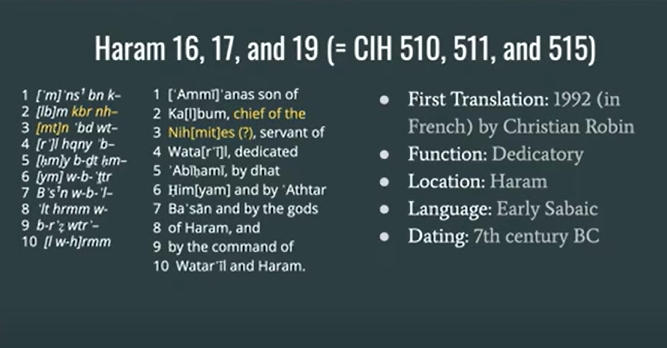

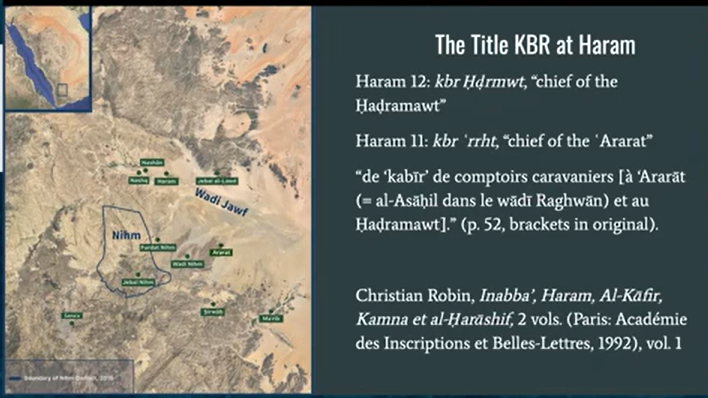

And they mention very similar titles to the previous one. They mention a Kabir, a chief or leader of a group called the NHMTN. And Christian Robin translated this. NHM means stone mason in South Arabian, so he thought this was maybe a reference to the chief of the stone masons, but other scholars, such as G. Lancaster Harding, have referred to this as a reference to a tribe or people. So there’s maybe a little debate on that one. If taken as a tribe, I think it’s reasonable to assume that, like the previous inscription with a similar title, here, this is probably referring to the Nihm. One possibility that was actually suggested to me by a scholar of ancient South Arabia is that these inscriptions refer to the chief or leader of a Haremite trade colony located within the Nihm tribe’s territory.

Inscriptions and Altars

That’s consistent with how we actually see the name, the title of Kabir, being used in other inscriptions at Harem. They refer to the chief of the Hadramawt, and the chief of the Ararat.These are not tribal chiefs from other places. These are referring to the leader of Haremite trade colonies that are established in those areas. So, it’s possible that’s the usage when it comes to Nihm here as well.

Now, obviously, you can see there are several more ancient inscriptions, and I want to try not to bore you with all of that. But there are several more inscriptions that refer to the Nihm tribe or region, or potentially do. And then, just the three altars that we’ve come to know really well as Latter-day Saints. As noted, some of these inscriptions also date back to Lehi’s time, or at least to the general period of the early first millennium BC, and they further corroborate that the name goes back to 600 B.C.

NHM Chronology

When Warren Aston first mentioned these inscriptions, he published this timeline, and this timeline represented all the references throughout history that he’s been able to track down referring to the Nihm tribe up to the present day. But when he referred to these different inscriptions, he kind of generalized to a single time period, as you can see there. So one of the benefits of having studied this out a little closer is we can actually kind of flesh out that pre-Islamic chronology a little better, as you can see on the timeline on the left, which also includes some additional inscriptions I didn’t mention but that get mentioned by Warren Aston in some of his publications. It helps us see that the Nihm tribe can be documented throughout the pre-Islamic period and throughout antiquity. It helps reinforce the long-term stability and ongoing continuity of this tribe’s presence that Warren Aston has frequently emphasized.

Of course, there are literally thousands of different inscriptions that have been found in ancient South Arabia, and most of them actually don’t mention NHM. I know that’s probably not surprising to any of you. But there are still other inscriptions that may be relevant or of interest to us. Of particular interest, I think, are going to be funerary inscriptions since Nahom was a place where Ishmael was buried.

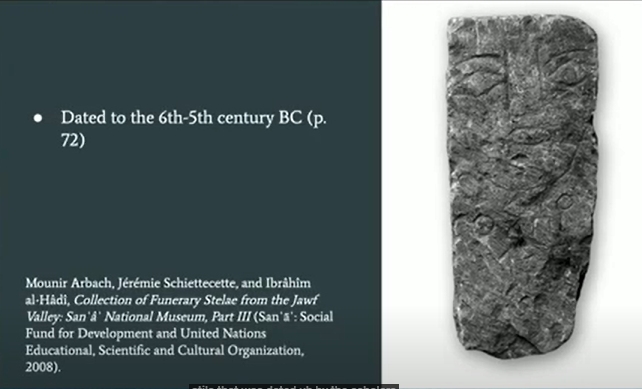

Funerary Stelae from the Wadi Jawf

And so, one time while I was doing research, I came across this collection of funerary stelae that was published some years ago, I kind of saw it. They’re a collection called carved face stelae, and in this particular collection, they were all looted, so we don’t know exactly where they came from. But I’ve kind of circled the general zone there where they’re believed to be from, on the map there.

And these are just some examples that come from there. Barakush is interesting because while it’s outside the official administrative district of Nihm, it does fall within the wider zone that the Nihm tribe controls historically. But that doesn’t necessarily mean, you know, their boundaries have fluctuated so maybe or maybe not that was the case in antiquity.

The Origins of the People in the Inscriptions

Scholars have kind of been debating the actual origins of the people that are mentioned in these different inscriptions, and one hypothesis is that they were outsiders or foreigners connected to the caravan trade in some way. And some of the evidence that’s used to support this hypothesis is their names, the onomastics, which tend to have ties to Northern Semitic languages rather than ancient South Arabia.This includes primarily North Arabian languages, but it also includes some Northwest Semitic languages more in general.

So this is what some scholars said after studying all of the examples that came from Barakush that I mentioned. They say,

We hypothesize that such individuals were connected in some way with the town of Barakush but that they were not, in effect, members of the community. The most plausible idea is that there were caravaners engaged in commerce throughout the western side of the peninsula, thus explaining why they used onomastics with some clear links to Minaic tradition but also to the northern tradition. They would have been foreigners who certainly had some sort of contact with the inhabitants of Barakush.”

An Alternate Conclusion

But on the other hand, the scholars who studied this particular collection of the looted funerary stelae, they came to a somewhat different conclusion. They think these actually represent the local population, but the lower strata, the lower social strata, the poor folk if you will, but they still acknowledge they say,

Even if most of the stelae were produced by the local population, a small number of them could have been made for the deceased of different cultural origins: Caravan traders, nomads, Mineans established in Northern Arabia, central and North Arabian populations, and so on.”

So my point in talking about all of this is just to make the point that these carved face stelae appear to represent the kind of stela that a foreigner traveling through the area would have used, probably without lots of money or resources or time to give a more grandiose burial. And of course, that fits the description of Lehi and his family.

Now the Book of Mormon doesn’t say if they buried Ishmael with a stela or not, but the point is if they did or anything and they were following the kind of local customs used for foreigners at the time, it might have been something sort of like one of these stela that have been found.

So when I first came across this collection a number of years ago, my initial thought was just like, “Huh, that’s kind of interesting, might be sort of useful for contextualizing Ishmael and his burial and whatnot.” I filed it away and didn’t really think about it again. About a week later, I was trying to reorganize all of my files and things like that, and I had completely forgotten that I ever saw this. I found it in my files and thought, “Oh, huh, that looks interesting.” So I browsed through it again and had the exact same thought process go through my mind: “That might be useful to kind of contextualize Ishmael and his burial at some point, but I’m busy right now, move on.”

The Name Ishmael in South Arabian Regions

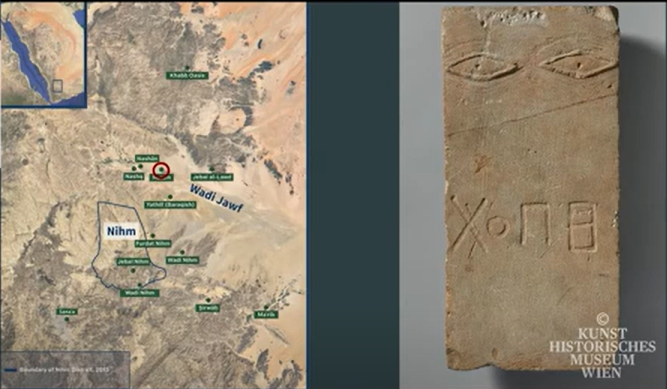

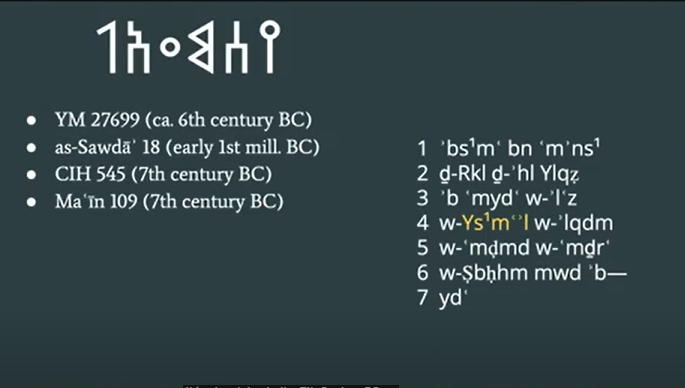

Then, a half hour later, I was struck with a thought – those stelae have names on them. I wonder if any of them have a name like Ishmael. So I went back to it and looked a little closer, and that’s when I found this.

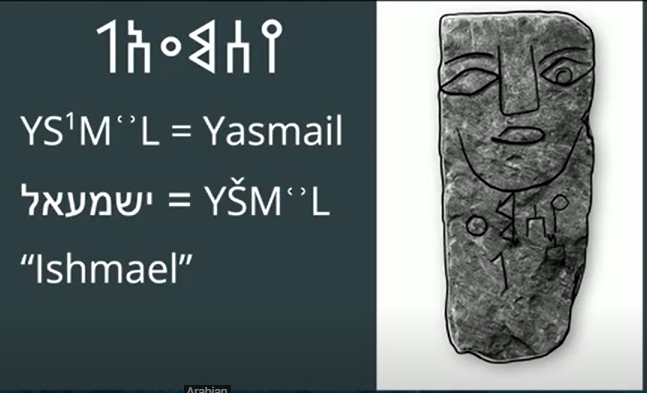

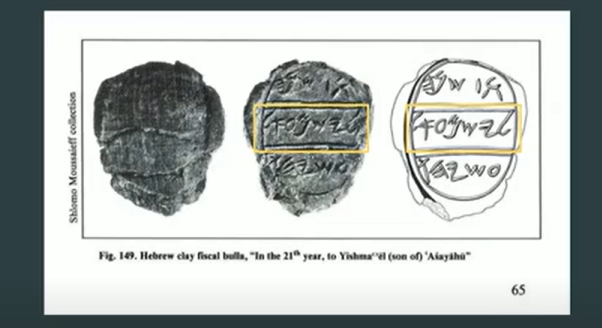

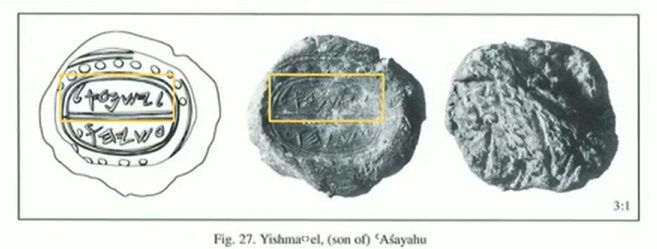

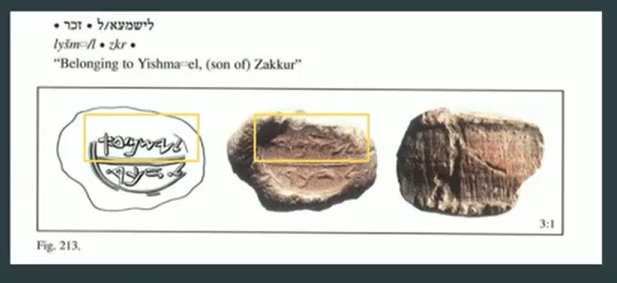

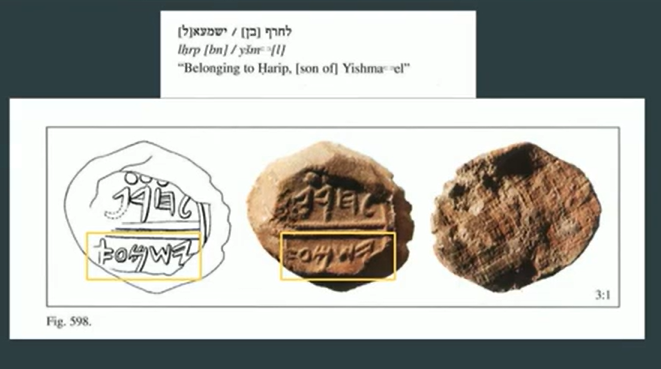

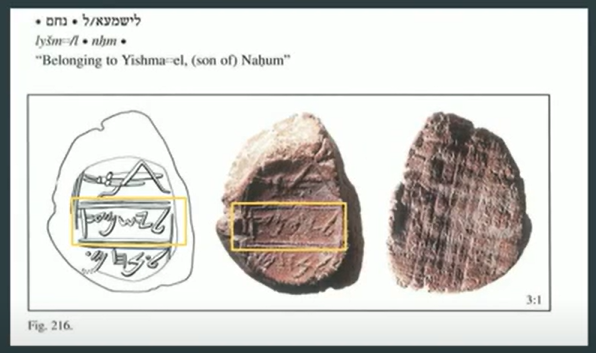

And this is the name that appears on it, outlined for clarity. For those who don’t know Hebrew, this is how that’s transliterated. And just as a kind of a note for everybody, that ‘s1’ in the letters above there represents the South Arabian ‘sat’ in the South Arabian alphabet. And that ‘s’ with the carrot over it represents the Hebrew ‘Sheen.’ And in South Arabian languages, the ‘sat’ is regularly substituted for the north Semitic ‘Sheen,’ when we look at the cognates in those languages.

So you’ve probably already surmised from here that this is the Hebrew name Ishmael. It gets translated as ‘Yasmail’ in the South Arabian inscriptions or ‘Ismail’ sometimes, but they are the exact equivalent names. They both mean the same thing: “may God hear” or “God has heard” or something along those lines. It’s the exact equivalent in the South Arabian script.

Ishmael

I do want to be clear about something: I am not claiming that this is the Ishmael from The Book of Mormon. I have absolutely no idea how we would ever be able to definitively prove that, and I’m not even willing to say it’s likely him. But I do think it’s possible, and I think it’s even a very tantalizing possibility if you think about it. But I stress it’s just a possibility.

What we can say here is that this stela does confirm that someone with the name Ishmael or its South Arabian equivalent was buried near the Nihm region in 600 BC. Based on the style of stela and the onomastics and so forth, it’s quite possible this person was an outsider in South Arabian society who came from the north along the trade routes. All of that is certainly consistent with the Ishmael of the Book of Mormon.

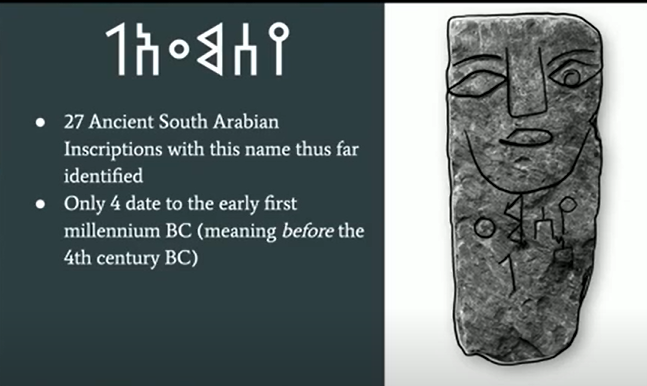

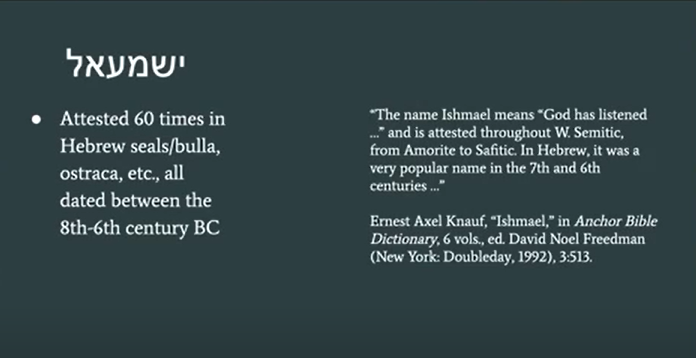

However, there are a lot of reasons why I’m not willing to be more definitive. One of them is the fact that we really cannot definitively rule out the possibility that it is someone local. This name ‘Yasmail’ or Ishmael is known in about 27 other inscriptions that I’ve been able to identify from South Arabia, and it’s a widely used Semitic name in a lot of other languages as well. So we can’t pinpoint it with absolute certainty.

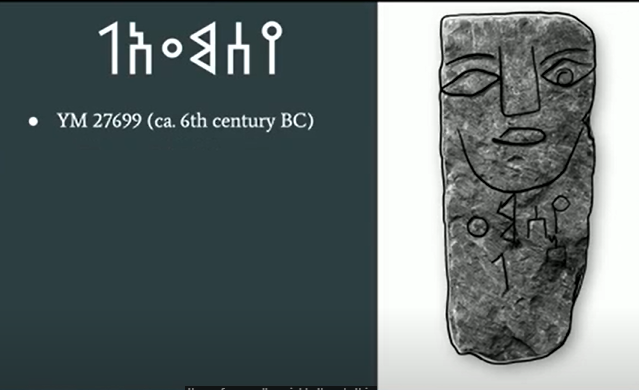

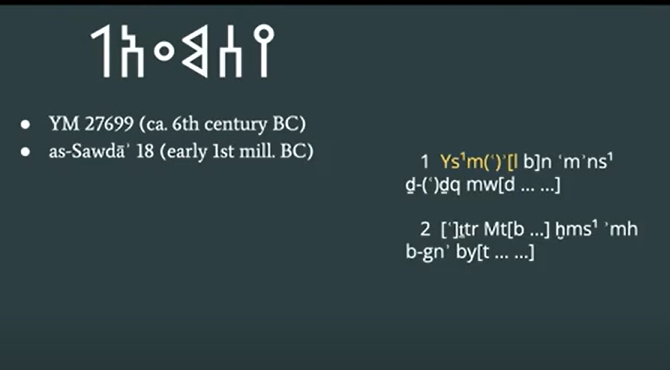

But I do find it interesting that of those 27 that have the name Ishmael on them (and this is out of a corpus of over 8,500 inscriptions), only four date to the early first millennium BC.

Four Inscriptions

So, we’re going to just go over those four, really quickly.

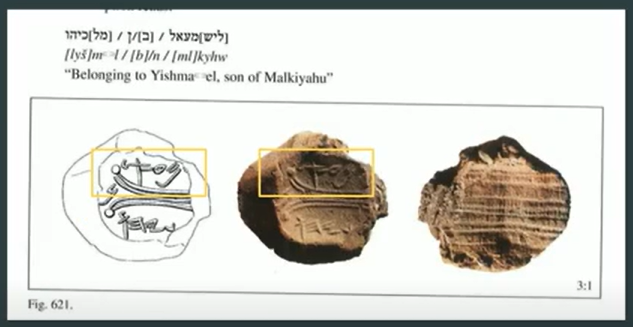

According to Ernest Axel Kanauf, in Hebrew, the name Ishmael was very popular in the sixth and seventh centuries BC. In my own searching of the seals and the bulla and so forth, I’ve identified about 60 attestations of the name Ishmael in Hebrew from between the 8th and 6th centuries BC. I’m not going to bore you with rehearsing all of those, but just to give some samples.

Conclusion

So to kind of sum everything up, we’ve long known that there’s evidence for a place called Nahom and inscriptions that go back to 600 BC. But there is, in fact, more inscriptions and more evidence than we have heretofore recognized, and that has been at least widely recognized among Latter-day Saints. The evidence is stronger and better than I think it’s ever been.

In conjunction with that, though, there’s also this evidence about the name Ishmael. While we can’t necessarily definitively link any of these attestations of the name Ishmael to the Ishmael of the Book of Mormon, I do think they are valuable in helping us contextualize and visualize Ishmael and his setting and his life and things like that. And they certainly are consistent. The details here, a popular name in Judah, so it makes sense that there’s an Ishmael from Jerusalem in the Book of Mormon at the time. All the details here are consistent with what we find in the Book of Mormon regarding Ishmael and Nahum. So thank you.

Audience Q&A

Scott Gordon:

Thank you very much. That was very interesting. My first question is, How do you address the criticism that Joseph Smith could have simply found the name Nahom on old maps?

Neal Rappleye:

That’s a wonderful ‘could have.’ Did he? This has been addressed by Kent Brown, who wrote an article in 2002 examining that. Others, like Jeff Lindsay, have also delved into this topic more recently with two lengthy articles in Interpreter, reviewing what we’ve discovered about these maps in considerable detail.

To my knowledge, the closest anyone has come to placing one of those maps near Joseph Smith is about 320 miles away. There is no evidence that Joseph Smith made such an unknown 320-mile trip to look at some obscure old map. Thus, I don’t see any compelling reason to think he did.

However, an aspect often overlooked is that those maps provide limited information. They give you a name, but critics initially responded by saying, “You don’t have evidence that goes back to 600 BC.” O.K., well, Joseph Smith would have had no way to know they go back to 600 BC. Now we do. Moreover, those maps wouldn’t have told you about Bountiful nearly eastward from Nahom or the trade routes that lead there, closely following Lehi’s trail. In the totality of evidence for Lehi’s Arabian journey, those maps don’t do very much for you. They don’t explain very much of the evidence at all. So if you want to use those maps, you’ve still got a lot of explaining to do.

Scott Gordon:

Another critical question arises: A popular response from critics is that NHM is only a tribal name, not a region, and that ancient Yemen tribes did not assign their names to places. But then today you’ve shown several scholars referring to the name as a region, the land of Nahom, etc. Other tribes, like Haram, have related place names. What else might you say about that argument against the significance of that?

Neal Rappleye:

That’s actually one of the things I’ve spent a lot of time working on. What we actually know from anthropological studies of Yemeni tribes and their structure is that there is a very, very strong link between the tribe and territory, and that’s to this day. If you’re from a particular region, you’re associated with that tribe.

In the inscriptions, the nisbah, like in NHMyn, indicates a person from Nahom, like “-ite.” One scholar I’ve read, whose speciality is in the onomastic formula, says you get this list of so-and-so who is the son of so-and-so from tribe… or whatever. She explains that tribal affiliation in those onomastic formulas are tying you to both the tribe and its territory. And that’s why you get these quotes that I’m sharing where some scholars say this links to the Nahom tribe or to the Nahom region. Because there is a lot of conflation of these two things in the literature.

In the early Islamic period, we find attestations of Nahom being referred to as both a tribe and a place. Lots of inscriptions are using tribal names as if they are place names, like “traveling along the border of (tribe’s name).” And when I talk about Kabir Hadramat, the chief of the Hadramat, the Hadramat is a tribe name, but it’s used routinely to talk about it as a region as well. This is all over the inscriptions. There’s no credible reason to split those hairs between tribe and place, in my opinion.

Scott Gordon:

So, why would a Jewish man like Ishmael have his stela written in South Arabian?

Neal Rappleye:

That’s a good question and a reason for caution. There’s nothing about the stela suggesting it’s from an Israelite. It’s using a native script, and so forth. I’ve published my thoughts on Ishmael and the stela in an article in Interpreter if you want to explore that further. And I address that question a little bit there. I think the best explanation, to my knowledge, we have no evidence that Lehi and his family were stone masons who could carve stone. So if they were going to bury him with a stela, they probably had to hire a local scribe, right? So that’s kind of my working theory there.

Scott Gordon:

Okay, what do you think about NHM, meaning ‘a sigh of mourning,’ like the prophet Nahum?

Neal Rappleye:

Yeah, so that’s all connected to the Hebrew etymology for NHM, and, I do think that Nephi is doing some wordplay stuff with that root. And, you know, Matt Bowen’s here; he could probably tell you a lot more about that than I could. But I actually think there’s a lot of really complex stuff going on in that passage, not only with that meaning but with some other meanings of the NHM name. But as far as South Arabian goes, it’s consistently identified as meaning ‘Stone Mason’ or ‘stone masonry’ and stuff like that.

Scott Gordon:

One more question here. On the map, you showed a proposed location for the camp of the Broken Bow. Why did you pick that location?

Neal Rappleye:

The only map I think that had that was actually the one in the 1978 Ensign. I don’t think I put that on any of my own maps, and that was prepared by, well, I don’t know who prepared it at the Ensign, but it was attached to Ross Christensen’s article. I’m pretty sure that was based on the itinerary for Lehi that was made by the Hiltons in 1976, published in the Ensign, and you can read about their reasons for that particular camp if you’d like.

Scott Gordon:

So, I think in your presentation, you’re either arguing that Joseph Smith was a scholar of South Arabian Peninsula history, or perhaps he might have been a prophet. Is that correct?

Neal Rappleye:

Well, I would say I think he’s a prophet. I think there’s something really interesting going on with the relationship of First Nephi and what we find in ancient Arabia. However, you want to explain that, is entirely up to you, but my money’s on prophet.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you so much. Appreciate it.

Endnotes & Summary

In Ishmael and Nahom in Ancient Inscriptions, Neal Rappleye explores archaeological evidence that supports the historicity of the Book of Mormon. Drawing on recent discoveries from South Arabia, he examines inscriptions referencing Nahom (NHM) and Ishmael dating to the 7th and 6th centuries BC—aligning with the Book of Mormon’s timeline. Rappleye evaluates arguments for and against the significance of these findings and explains how they strengthen the plausibility of Lehi’s Arabian journey.

📖 Books Mentioned in the Talk:

- Lehi in the Wilderness by George Potter and Richard Wellington

- In the Footsteps of Lehi by Warren P. Aston

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 3, 2022

- Duration: 42:29 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2022 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: Neal Rappleye FAIR talk, Nahom Book of Mormon, Ishmael Arabian inscriptions, LDS archaeology evidence, CES Letter Nahom critique, Mormon Stories Nahom argument, Lehi’s trail Arabia, Book of Mormon historicity, FAIR Mormon Arabia discoveries

Common Concerns Addressed

Joseph Smith could have found Nahom on old maps.

Maps available in Joseph Smith’s time lacked the archaeological context, dating, and geographic detail that modern inscriptions provide. No known access exists for Joseph Smith to these maps.

NHM is only a tribal name, not a place.

Inscriptions and anthropological data show tribes and territories were often synonymous. Tribal names are frequently used as place names in ancient texts.

Apologetic Focus

Ancient inscriptions support names and locations in the Book of Mormon.

Linguistic, cultural, and archaeological evidence bolster claims of historicity.

The cumulative case aligns with the 1 Nephi narrative far beyond coincidence.

Explore Further

coming soon…

Share this article