Summary

Joseph Smith: The World’s Greatest Guesser? challenges the notion that Joseph Smith, the founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, could have accurately guessed the details found in The Book of Mormon and other revelations. The presentation explores the improbability of such guesses being correct without divine inspiration, highlighting historical, linguistic, and cultural evidence that supports the authenticity of Smith’s prophetic claims.

This talk was given at the 2020 FAIR Annual Conference on August 5, 2020.

Bruce and Brian Dale present a data-driven statistical analysis of The Book of Mormon, applying Bayesian probability to test the hypothesis that Joseph Smith guessed its content. Using 131 detailed correspondences between The Book of Mormon and Michael Coe’s The Maya, and comparing them against control texts, they argue the statistical evidence overwhelmingly supports the Book of Mormon as an authentic ancient document.

Transcript

Introducing Bruce and Brian Dale

With our next speakers, we have Bruce and Brian Dale, and both of them have PhDs, so obviously, education runs in the family. Bruce Dale has degrees in chemical engineering, and Brian Dale is a biomedical engineer. They have a wonderful presentation for us today. They’re not with us in the room, but I’m going to turn the time over to them.

Presentation

We really appreciate the opportunity to present our work here today. It’s a long title, and no, it’s not necessary to go ahead and repeat it, but we’re going to show you that Joseph Smith is without any doubt about the world’s greatest guesser.

Our presentation is based on a paper we published in Interpreter a little over a year ago with the same title. It’s going on 110 pages, so there’s lots of detail in there. We won’t cover anything but a small fraction of that detail. I’m your first presenter; this is me. I typically wear a hat; I want you to be able to recognize me if you see me wandering on the streets. I will present the start, why we started this study, the kind of the background for it.

Then Brian, who’s the true expert here in the Bayesian statistics, will tell a little bit about Bayesian statistical methods. Then I’ll take over the presentation again and show you how we apply Bayesian methods to a comparison of The Book of Mormon and Dr. Michael Coe’s book, The Maya, and then a couple of control books.

Correspondences

Okay, so the first question is, what are correspondences since that’s an important part of the title? They are connections, commonalities, conformities, correlations, you know, the list there, and of course, the dreaded word, parallels. I’ll talk a little bit more about parallels in just a moment. But they’re points of evidence, and when you see a correspondence or a conformity, the details line up, they fit with each other. Okay, the question is how well?

Parallelomania

Parallel mania or the drawing of parallels has been justly criticized. We would like to explain to you why this is not parallel mania. First, we start with a very strong skeptical prior hypothesis, which is part of the Bayesian methods. I’ll speak more about it, but we start with prior odds of a billion to one that The Book of Mormon is fiction, a lie, that it is what its enemies claim it to be, a lie.

We then assemble both positive and negative correspondences, our points of evidence from both Michael Coe’s book, The Maya, and The Book of Mormon. All the positive and negative correspondences that we can find.

We use Bayesian methods to weigh, because not all evidence is equally strong, but we weigh both the positive and the negative points of evidence. And then we calculate the posterior odds using the weighted positive and negative evidence. In other words, we start with a prior hypothesis, we evaluate the evidence both for and against, and then calculate a new hypothesis.

Sensitivity Analysis

Second, we do a sensitivity analysis, determine how robust our conclusions are. In other words, if you change your assumptions, change the data, how much do the conclusions change? We also test The Maya versus two control books, and we’d like to thank the reviewers for making this suggestion. I want to give them great thanks for making me read both Manuscript Found and A View of the Hebrews half a dozen times each, and together, those are the two control books.

So, we test The Maya versus the two control books. And this is again why it’s not parallel mania, because we have these controls, we’re seeing how strong the evidence is. Parallel maniacs do none of these things. They just don’t approach it this way; they’re only just in positive parallels. So, we think this is the first attempt to use Bayesian methods to evaluate a specific body of evidence for and against The Book of Mormon.

Okay, we compare facts as stated in these two books. This is our body of evidence. We compare The Book of Mormon, Another Testament of Jesus Christ, with the ninth edition of Dr. Michael Coe’s book, The Maya. Dr. Coe passed away a year and a half ago, a critic, a fairly woeful critic of The Book of Mormon.

Criticisms

Here is some of his criticism. This is the 1973 Dialogue article he wrote about Mormons and archaeology, quoting Dr. Coe: “The picture of this hemisphere between 2000 BC and AD 421 as presented in the Book has little to do with early Indian cultures as we know them, in spite of much wishful thinking.” Of course, the wishful thinkers are those who believe The Book of Mormon to be an authentic book, in other words, you and me.

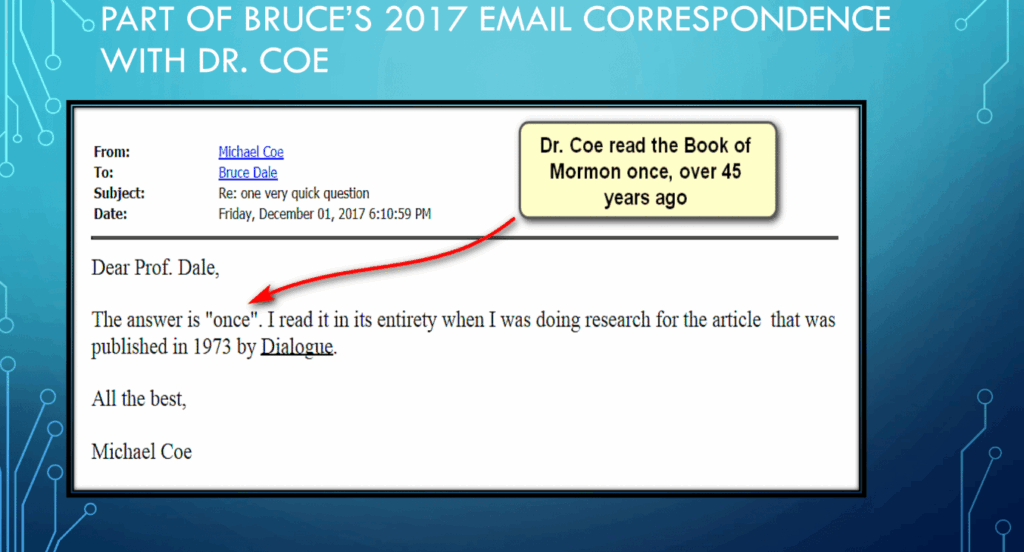

Those are powerful condemnations of The Book of Mormon, actually, to say doctrinally. That’s pretty strong language. That 99% of the details are false; those might be valid or important or meaningful criticism if Dr. Coe actually knew much about The Book of Mormon, but he did not. Okay, he was almost completely ignorant of The Book of Mormon; he didn’t know the details. Therefore, he could not compare the details because he didn’t know them.

Conclusions

In one of the podcasts, in fact, he seemed surprised that there were wars in The Book of Mormon. We’re now hip-deep in the war chapters in The Book of Mormon. It is kind of surprising that he missed that, but he did. He did miss it. So, how do I know this? How do we know this? I wrote him in December 2017 and asked him how many times he had read The Book of Mormon. His answer was once, at that point more than 45 years ago. Once. Okay, so he arrived at these conclusions, these opinions from the single reading of The Book of Mormon 45 years ago in preparing for his Dialogue article.

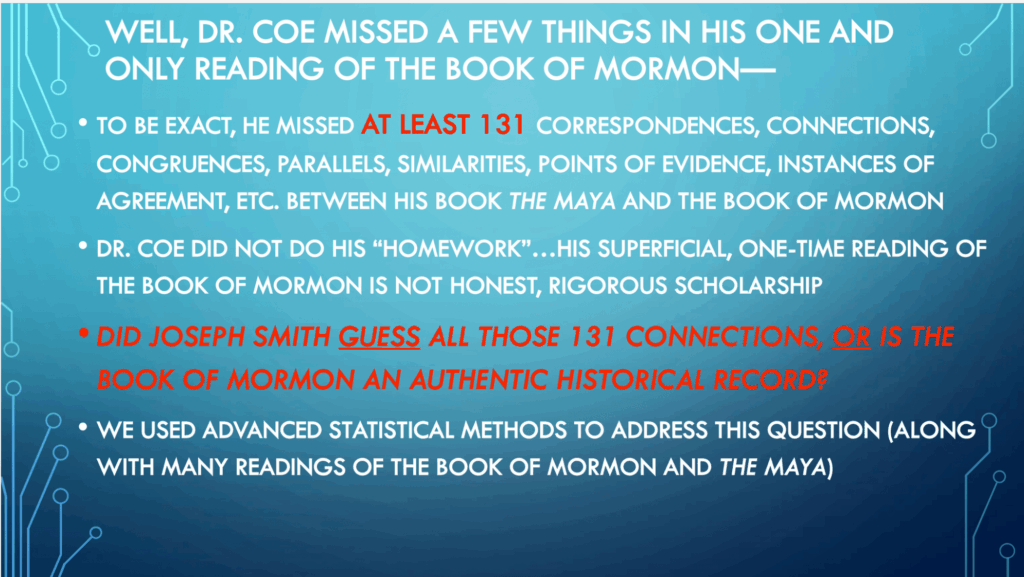

Well, he missed a few things in his one and only reading of The Book of Mormon. There are at least 131 correspondences, connections, congruences, similarities, points of evidence between his book, The Maya, and The Book of Mormon. He didn’t do his homework; that’s just the frank, honest truth. It’s a superficial, one-time reading of The Book of Mormon. That’s not honest, rigorous scholarship; that’s not how I approach review tasks when I review books or papers, and it’s not how he should approach it, but that’s what he did.

Did Joseph Smith Guess These Connections?

So, the question is, did Joseph Smith guess all those 131 connections, or is The Book of Mormon an authentic historical record? I think you don’t have any choices. Dr. Coe has also obligingly told us that in about 1840 when Stevens and Catherwood first went to the Yucatan, that literally nothing was known about ancient Mesoamerica. So, there were no sources on which Joseph Smith could have drawn for details of ancient Mesoamerica. Therefore, every factual statement in The Book of Mormon is a guess.

Okay, and the question is, do those guesses line up with ancient Mesoamerica? I knew enough about ancient Mesoamerica to know that there were a lot of similarities with The Book of Mormon even without reading Dr. Coe’s book, The Maya. So, I went ahead and read it seven times to try to understand the details, and then we used advanced statistical methods to address the question, “Is The Book of Mormon an authentic historical record, or is it a lie? Is it fiction?”

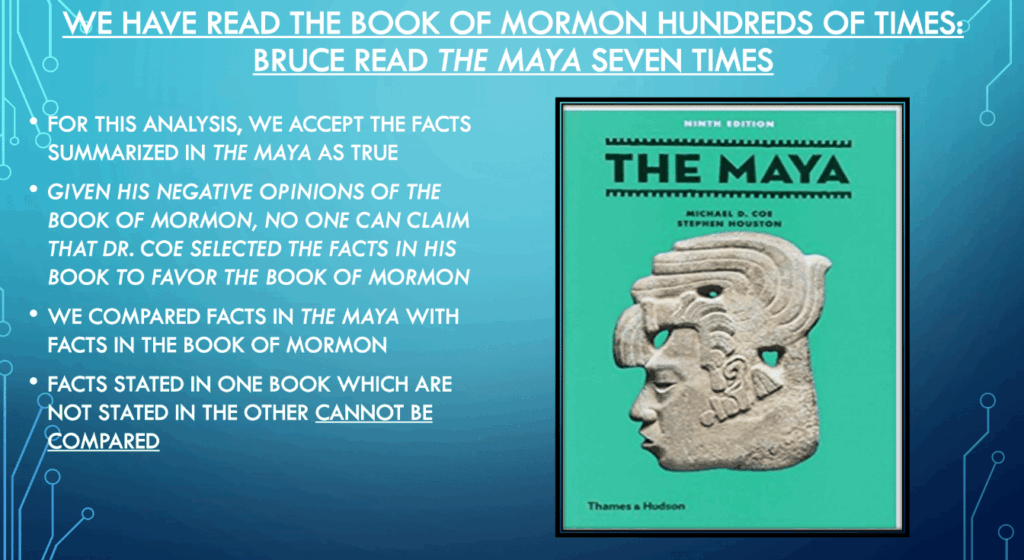

Facts in The Maya

Between us, Brian and I have read The Book of Mormon hundreds of times. As he said, he’s read The Maya seven times for purposes of this analysis. We accept the facts summarizing The Maya as true. In other words, we regard them, even though they may not all be correct, we regard that as our bedrock, grounding into the truth.

Given his very negative opinions of The Book of Mormon, no one can claim that Dr. Coe has selected the facts in his book to favor The Book of Mormon. And we compare it to the facts in The Maya, then with facts stated in The Book of Mormon. Facts in one book, which are not stated in the other, can’t be compared. There’s no grounds for doing that.

At this point, Brian will take over and talk to you about Bayesian probability.

Bayesian Probability Explained

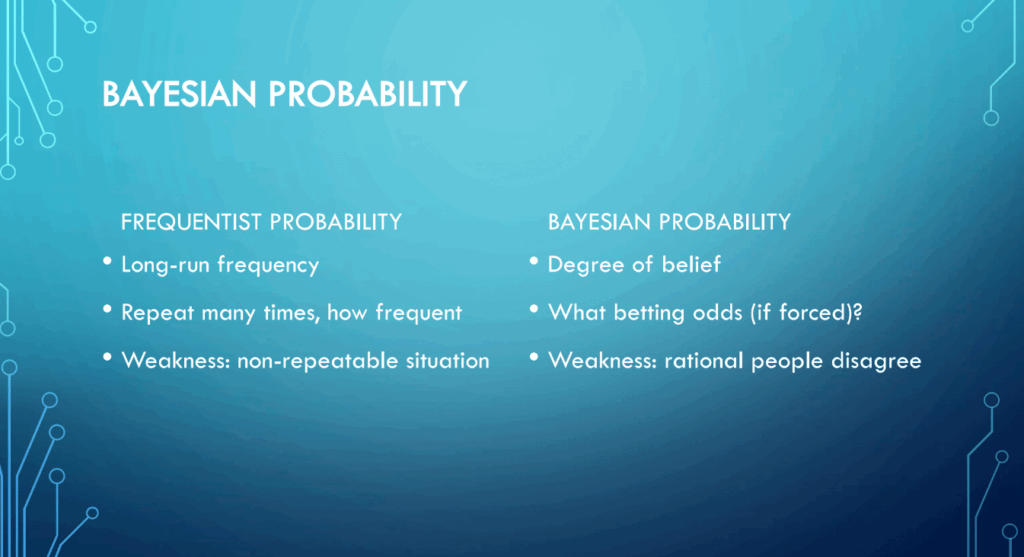

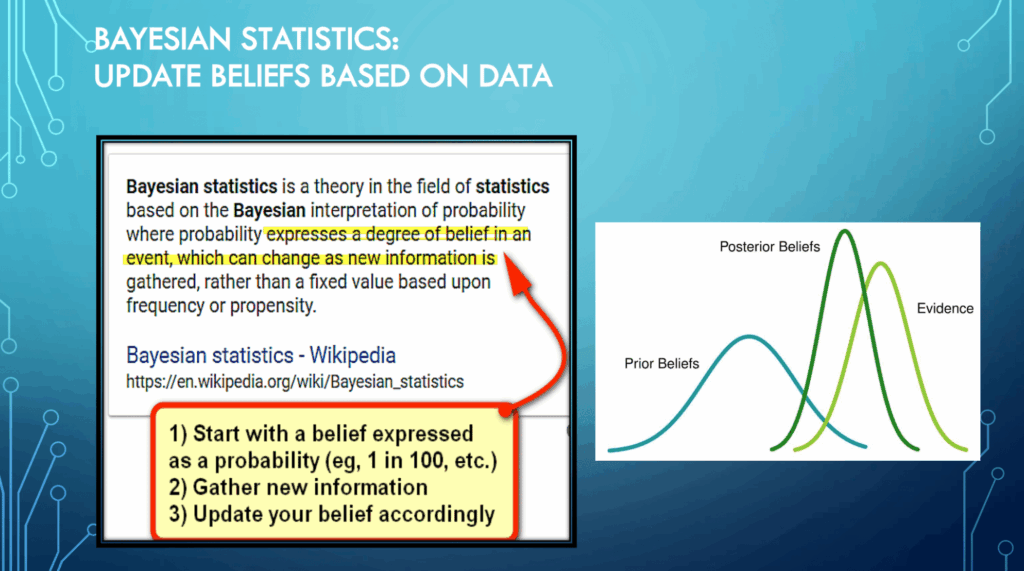

So, my dad already mentioned that we’re going to use some fairly advanced statistical methods. It’s not so much these methods are particularly advanced as that they are relatively uncommon.

Most statistics when they’re done are done with what’s called frequentist statistics, and frequentist statistics basically are based on the idea of a probability as a long-range frequency. So, if we’re talking about flipping a coin and we flip it one time, then it may turn out heads or it may turn out tails. If we flip it 10 times, then we may get seven heads and three tails. If we flip it a million times, then we expect to get pretty close to about 500,000 of each, heads and tails. So, that’s the idea of a frequentist probability; it’s something that you repeat over and over and over, and then you just count what proportion of those wind up being the thing that you’re looking at.

One of the weaknesses of frequentist probability is that it’s really difficult to address things that only happen once, so you can’t really assign probabilities to things that are just a single event that just happened once. Bayesian probability is a little bit different.

Bayesian probability is based on the idea of probability as an indication of how strongly you believe a statement. So, if I start with a coin, then before I even flip it and I haven’t acquired any data, I might say, I think it’s a 50-50 chance that it will turn up heads. So, that is a statement of my belief, and that’s what Bayesian probability looks at.

Beliefs and Weakness

Then, the Bayesian method is a method for using data to update your beliefs. So, as I flip a coin repeatedly and repeatedly and I start to get more heads, more tails, then I start to get a stronger belief about what that percentage is, what that long-range frequency would be. So, Bayesian statistics allow you to update your beliefs; it allows you to express your beliefs quantitatively, express your beliefs in terms of probability, and then rationally update your beliefs as evidence is acquired.

Bayesian probability, in this sense, usually when you look in the literature, is more closely related to betting odds, which may not be the best approach for this audience, but in general, the idea is, you know, would you prefer to have a bet on a roulette wheel with a certain number of slots marked out for wins, a certain number for lose, or the truth of whatever probability statement you’re making?

One weakness that Bayesian probability has is that rational people may disagree. In particular, that’s encoded in what we call our prior belief. Our prior is our beliefs that we go into the data collection with. As Bruce mentioned, we’re going to start with a prior that basically reflects not our personal belief, but what we believe our opponents would believe, a billion to one against The Book of Mormon being factual. Dad, could you go to the next slide?

I already briefly covered this, but Bayesian probability expresses a degree of belief in an event which can change as new information is gathered. For example, on the right shows we’ve got this line that’s labeled prior beliefs, a line that’s labeled evidence, and then our posterior beliefs are a merging of our prior beliefs and the evidence.

Coin Example

So, if we had, let’s say, we went back to that coin example, and maybe I think it’s probably 50% because most coins are close to 50%, but I don’t really know this specific coin, so maybe I want to be a little bit cagey and say that’s somewhere between, you know, 25% and 75%, so I might, in fact, have a graph like this that shows the probability that my prior belief about what I assume based on my general knowledge of general coins might be, and then as I flip a particular coin and find maybe that it’s not 50-50, then my beliefs can update and they can get, both shifted in terms of what I believe and also narrowed in terms of how uncertain I am about my beliefs.

Okay, so that’s the idea of Bayesian statistics; we’re going to start with some prior beliefs, we’ll obtain evidence, and will modify our beliefs according to these Bayesian statistics.

Simple Example of Bayesian Statistics

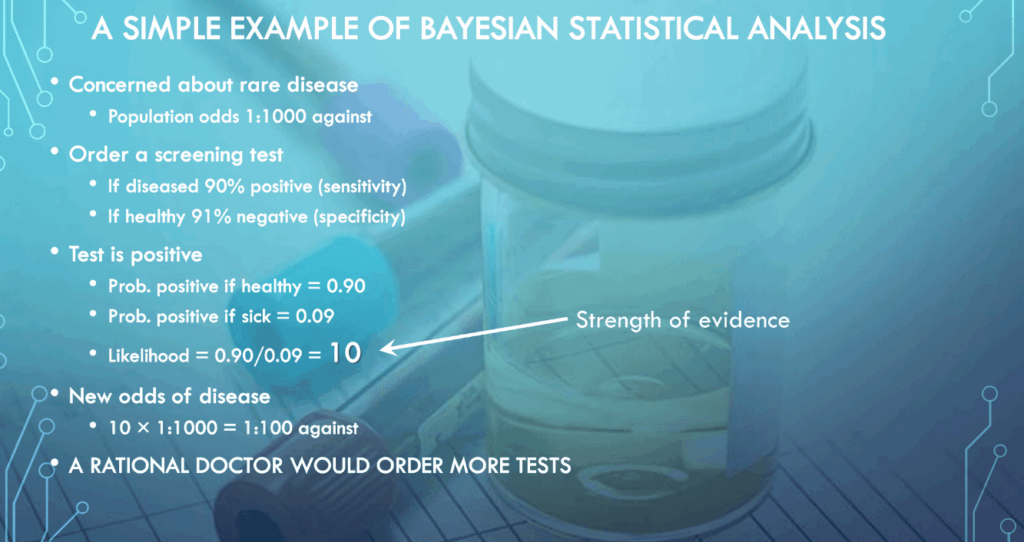

So, the way that this works with a fairly simple dichotomous example, for example, in our case, is The Book of Mormon fiction, yes or no? Other common examples are, you know, do you have a specific disease? So, this is kind of, in the literature, the most common example that they use. And so let’s take this example of we have a patient, and this patient goes to their doctor, and they’re concerned about whether or not the patient has a rare disease.

And we know from just basic population statistics that the odds of them actually having this disease is a thousand to one against, just based on the frequency of the disease in the population. So, if we order a screening test that has a 90% sensitivity and a 91% specificity, so that means that if they have the disease, it’s 90% likely that the test will say they’ve got it, and if they don’t have the disease, then it’s 91% likely that the test will come out negative.

If we run that test and we find that the test is positive, then we want to use that to update our beliefs about whether this person actually has the disease. In this case, the probability of getting a positive result if they’re healthy is 90%, and the probability of getting a positive result if they’re sick is 9%, so the ratio of those two is 10. This 10 indicates the strength of that evidence from that test.

Calculating

To calculate our posterior beliefs, you know, how the evidence changes our beliefs, we take our prior, which is that 1000:1, and we multiply it by 10, and so that gives us a 100:1 against. And so even after this test, it’s still much more likely that the patient does not have that disease. A rational doctor would hold off and say, okay, we’re not going to begin treating for this disease, we’re going to order some more tests, and we’re going to accumulate a preponderance of evidence. So that’s the idea of Bayesian statistics.

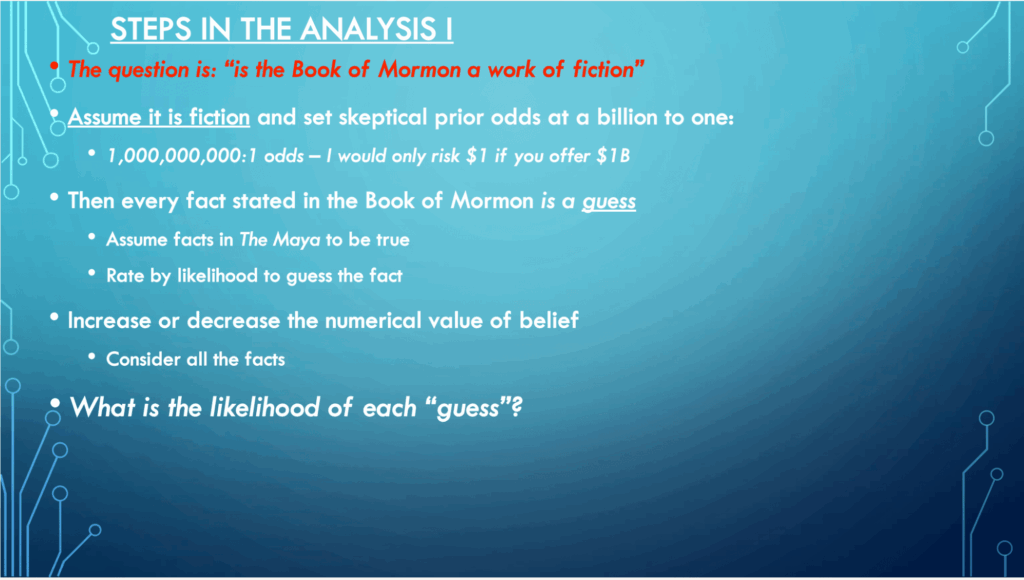

Using Bayesian Statistics to Test the Truthfulness of The Book of Mormon

What we’re going to do in our work is we’re going to test this proposition, “The Book of Mormon is a work of fiction.” We’ll assume that it’s fiction, not because we personally believe that it’s fiction, but because that’s what our opponents would believe, and so we want to do something that would be as convincing as possible to a reasonable opponent.

We’ll start with some insane odds, a billion to one, that it is a work of fiction. So, to put that in the context of Bayesian statistics, what we’re saying is I wouldn’t accept a bet that it’s true unless you would offer me one billion dollars for a one-dollar stake. I wouldn’t take a bet unless it was a billion to one.

So, I wagered my one dollar, and you wagered a billion dollars; that’s the only way that I would take the bet that it’s not fiction. Okay, so that’s what we’re saying. This is my personal opinion, but my personal belief is that if somebody’s so skeptical that they won’t accept billion to one odds, chances are that they’re, you know, just not going to be rational anyway, so this is about the most extreme that we could put what we believe a skeptical but rational person would have as a prior belief.

If It’s Fiction

Alright, so if it’s a work of fiction, then every fact in The Book of Mormon is a guess, and so we’re going to assume that the facts in The Maya are true, and we’re going to rate everything by the likelihood that Joseph Smith would have to guess that fact, so that’s going to be that factor of 10 that I showed in the previous slide, so we’re going to look at each thing as an individual test, and we’re going to rate the strength of that test on a scale, and as we repeat that over and over, that will allow us to increase or decrease the numerical value of our belief, so allow us to change these odds, right?

Our Approach

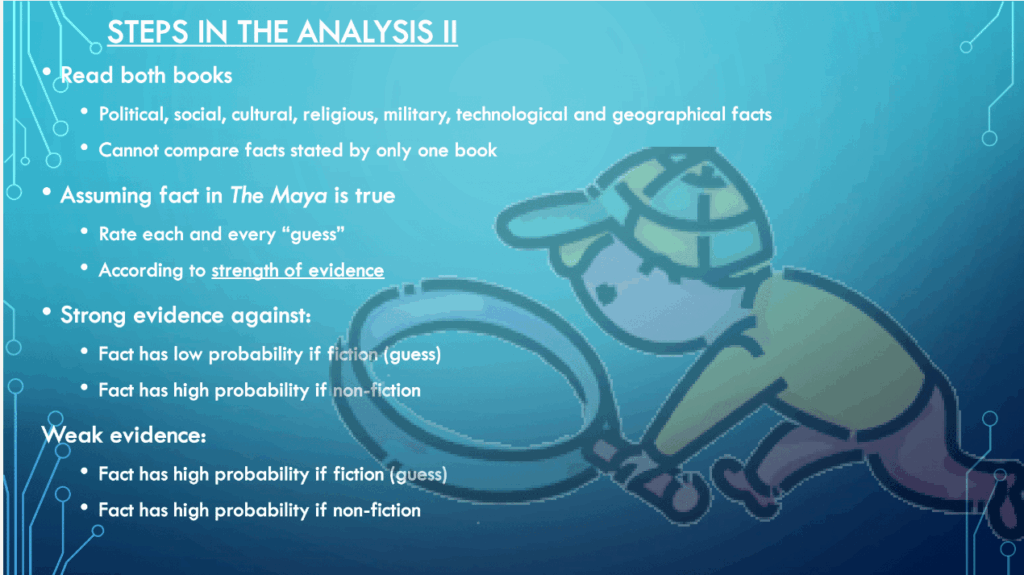

So, the approach that we took is that my dad, in particular, read both books and as he was going through, he accumulated political, social, cultural, religious, military, technological, and geographic facts. So, all these different types of facts, and looked at the facts that are identified in both books. Now, the reason we needed to have facts that were identified in both books is because if a fact is stated in both books, then we know both authors’ opinions. We know the fact as The Maya has it, and we know the guess by Joseph Smith.

If a fact is stated in The Maya but not in The Book of Mormon, then we have no basis for assuming what Joseph Smith would have said, whether he would have guessed right or wrong. Similarly, if a fact is stated in The Book of Mormon but not stated in The Maya, we have no way of saying what Dr. Coe would have said. So, we’re only going to compare facts that are stated in both, and we’re going to skip over any facts that are stated in only one or the other.

To check them to see if those facts agree or if they disagree and we’ll rate each of these according to the strength of the evidence. So, things that have strong evidence are facts that have a low probability if Joseph Smith was writing a book of fiction, and a high probability if they’re not fiction. A weak evidence would be facts that have a high probability if it’s fiction and also high probability if it’s non-fiction.

Agreements

So, in other words, we can assume that whether The Book of Mormon is fact or fiction, or The Maya is, that they both agree about things like people ate food. You know, obviously, people eat food, so that is weak evidence because it has a high probability if it was fiction; it has a high probability if it’s non-fiction.

So, the things where you have strong evidence are where it’s a low probability of fiction and a high probability of non-fiction. So, that’s the important thing. Those are the things that we’re looking for when we’re categorizing the strength of the evidence.

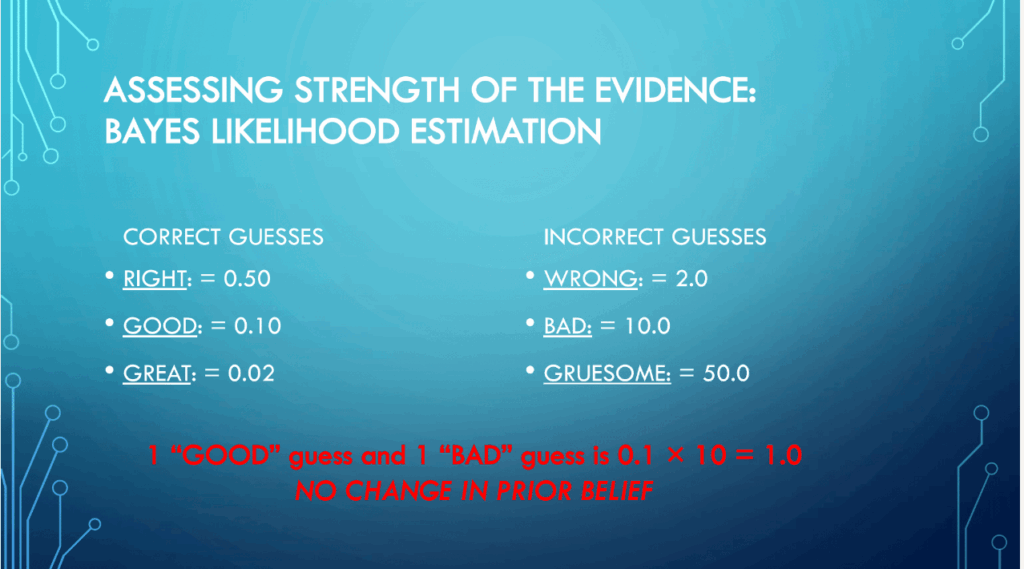

Strength of the Evidence

So, we used this scale for setting up what we call the strength of the evidence. Correct guesses have numbers that are less than one; incorrect guesses have numbers that are greater than one. So, incorrect guesses make those odds smaller. Remember we started at a billion to one, and incorrect guesses make those odds even larger. So, each time we have a fact, we’ll multiply the strength of that fact, this is the likelihood estimation, by the odds that we have at that point in the chain.

If we have conflicting evidence, we can actually handle conflicting evidence with this approach. So, when we have conflicting evidence, we don’t have to just throw up our hands and give up, we have a specific way that we can combine those. So, essentially, one bad guess and one good guess will cancel each other out. That’s a way to deal with conflicting evidence. And so, if we have those, then we won’t have any change in our prior belief.

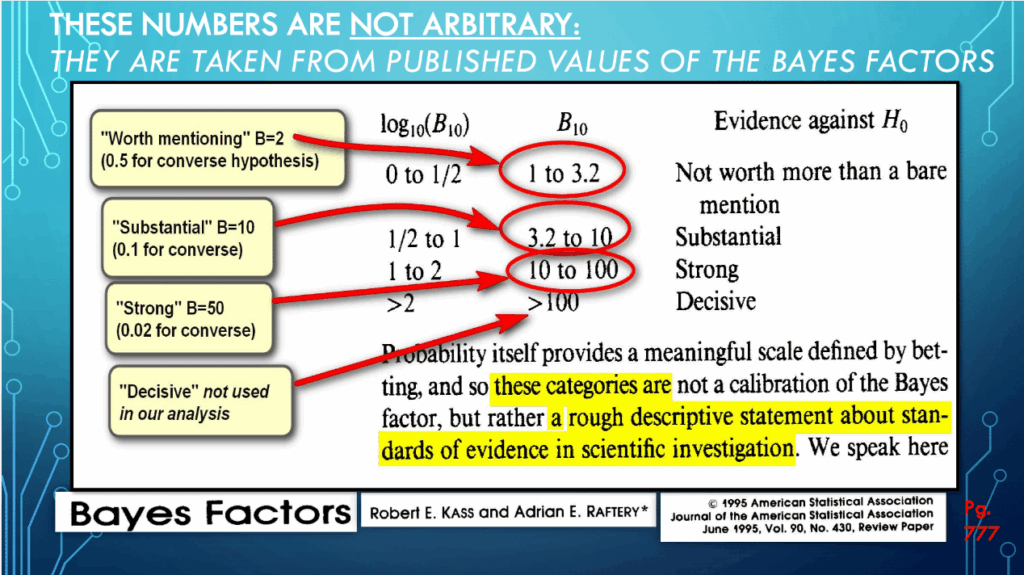

So, I’ll take it from here. The numbers that Brian cited just a moment ago are not arbitrary. We didn’t just make those up. They’re taken from published values of the bayes factor. It’s found in this particular reference 1995, Journal of the American Statistical Association. These authors just entitled “The Bayes Factors,” page 777.

So again, the three different strengths of the evidence for the hypothesis, the likelihood of The Book of Mormon being a work of fiction, a base factor of 2, 10, and 50. And for the converse hypothesis, that it’s an authentic book, 0.5, 0.1, 0.02. Again, in each case, 0.5 times 2 is 1, plus 0.1 times 10 is 1, they cancel out. One strong guess for and against cancel each other out.

Kass and Raftery

The Bayes factor that Kass and Raftery also use, what they call the a decisive number, where it’s over greater than a hundred, we didn’t use our analysis. We did now allow any guess to be decisive one way or the other, although we think that there are actually a guesses or facts stated in The Book of Mormon that are so strong that you could regard them as decisive, but we don’t allow any number to be to be higher here than a Bayes factor of 50. Okay. Kass and Raftery point out that these are a rough descriptive statement about standards of evidence in scientific investigation.

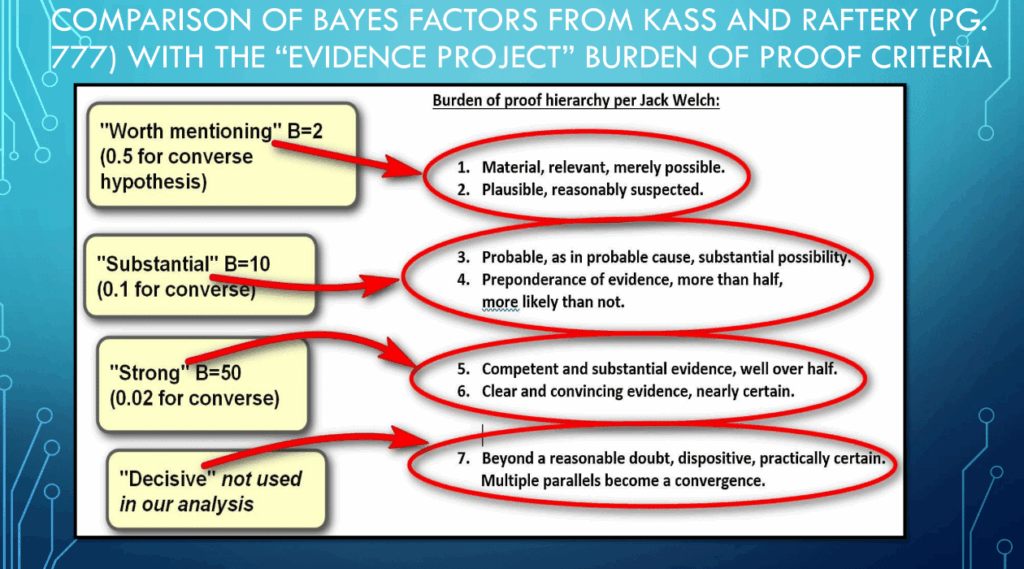

Now, this is interesting because we can compare that with the evidence project burden of proof according to Jack Welch, and it seems to me that this is a fruitful way of perhaps quantifying these burden of proof criterias per Jack Welch. Worth mentioning, base factor of 2 categories one and two substantial, base factors of 10, probable preponderance of evidence, strong, confident, substantial, clear and convincing, almost certain.

And then decisive again, but we didn’t use it. But Jack Welch points out here, the Evidence Project, this is beyond a reasonable doubt, dispositive, practically certain, multiple paragraphs become a convergence. And we didn’t use that, but we certainly believe that there are categories of evidence in The Book of Mormon that would rate that.

For instance, the presence of poetic parallels. I would rate as a physical scientist, the detailed description of a volcano and associated earthquakes in 3 Nephi chapter 8. I think that is beyond a reasonable doubt, dispositive.

Rating the “Guesses”

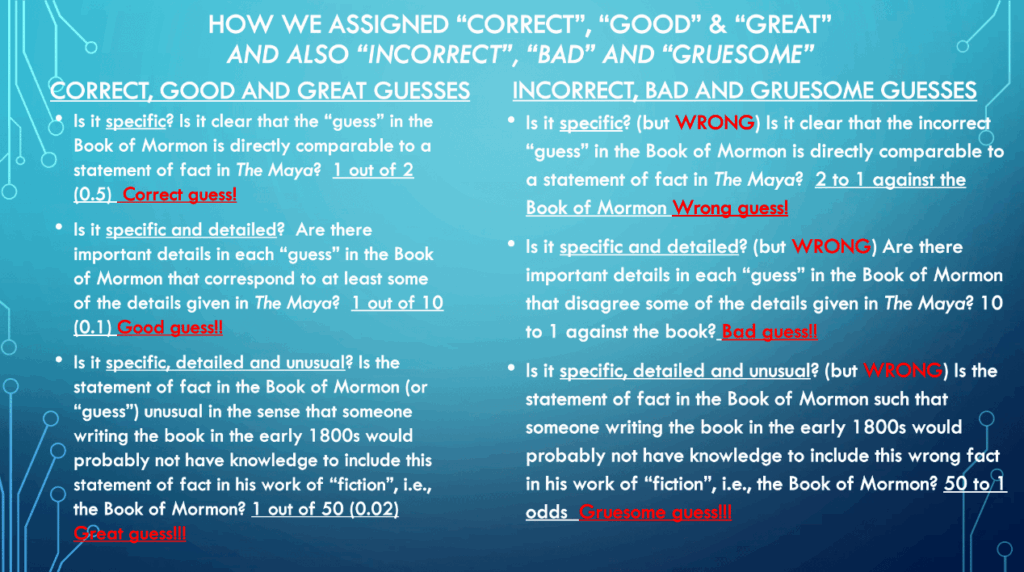

Here’s how we assign correct, good, and great, also incorrect, bad, and gruesome guesses. Again, correct, good, and great guesses. Is it specific? Is it clear that the guess in The Book of Mormon directly comparable to the statement of fact in The Maya? That’s a correct guess, 1 out of 2 (.5). Specific and detailed? Are there important details in each guess that correspond to details in The Maya? That’s a good guess. Is it specific, detailed, and unusual? Is the statement of fact in The Book of Mormon or guess, unusual in the sense of someone writing the book in the early 1800s who probably wouldn’t have the knowledge to include that in his work of fiction? That’s a great guess. Okay, 1 out of 50 (.02).

And corresponding for incorrect, bad, and gruesome guesses, specific, but wrong, counts against The Book of Mormon. Specific and detailed, but wrong, counts 10 to 1. If it is specific, detailed, and unusual, but also wrong,that’s a gruesome guess, 50 to 1 odds. And the kind of gruesome guess would increase the weight of the evidence by a factor of 50. In other words you would multiply the billion to one by 50, you increase the weight of the evidence against The Book of Mormon.

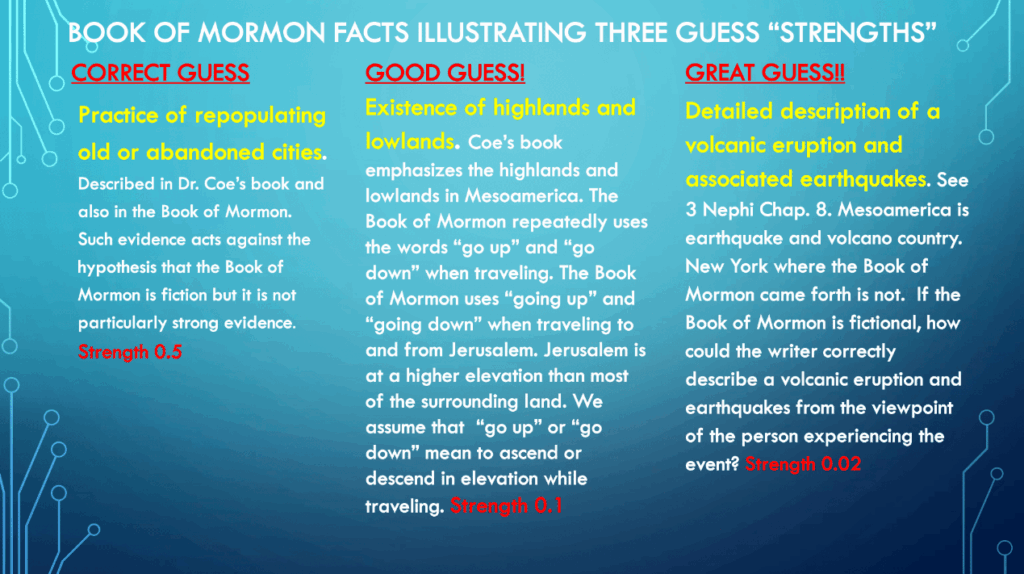

To illustrate, here are three guess strengths:

The correct guess, both The Book of Mormon and The Maya refer to the practice of repopulating older abandoned cities and it’s correct, but it’s not particularly strong. We give it a strength of 0.5. A good guess, the existence of highlands and lowlands. Coe’s book emphasizes highlands and lowlands, and The Book of Mormon does too, if you assume that ‘go up’ and ‘go down’ mean to ascend and descend in elevation.

Recalculating Our Hypothesis

We believe that’s correct. A great guess is what I mentioned earlier, 3 Nephi, chapter 8. We gave that a strength of 0.02. I think it’s actually, practically certain, in other words, that The Book of Mormon had to occur in a part of the world where there were volcanoes and associated earthquakes. And it’s just an excellent guess. Hugh Nibley pointed that out a long time ago, and Jerry Grover more recently, did another very good job there.

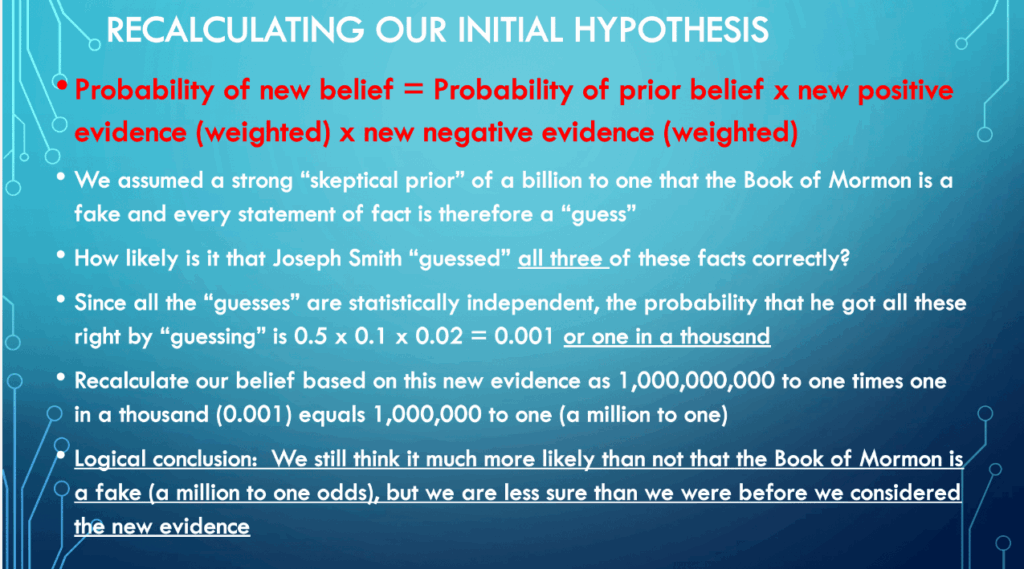

So we recalculate our initial hypothesis and point out that again, the probability of the new belief is the probability of the prior belief times the new policy of evidence weighted times the new negative as it’s also weighted. Again, a billion to one.

How likely is it that Joseph Smith guessed all three of these facts, the repopulating of old cities, high and lowlands, and also volcanoes? So they’re statistically independent. The probability he got all three of these right by guessing is the product of those. Bayesian statistics follows regular statistical methods, and that’s the probability of independent events occurring together, is a product of their probabilities. So 0.5 times 0.1 times 0.02 is one in a thousand.

We recalculate our belief based on this new evidence as a billion to one times one in a thousand which equals one in a million. Okay, the logical conclusion here is that we think that it’s much more likely than not that The Book of Mormon is a fake, (a million to one odds), but we’re less sure than we were before we considered this new evidence.

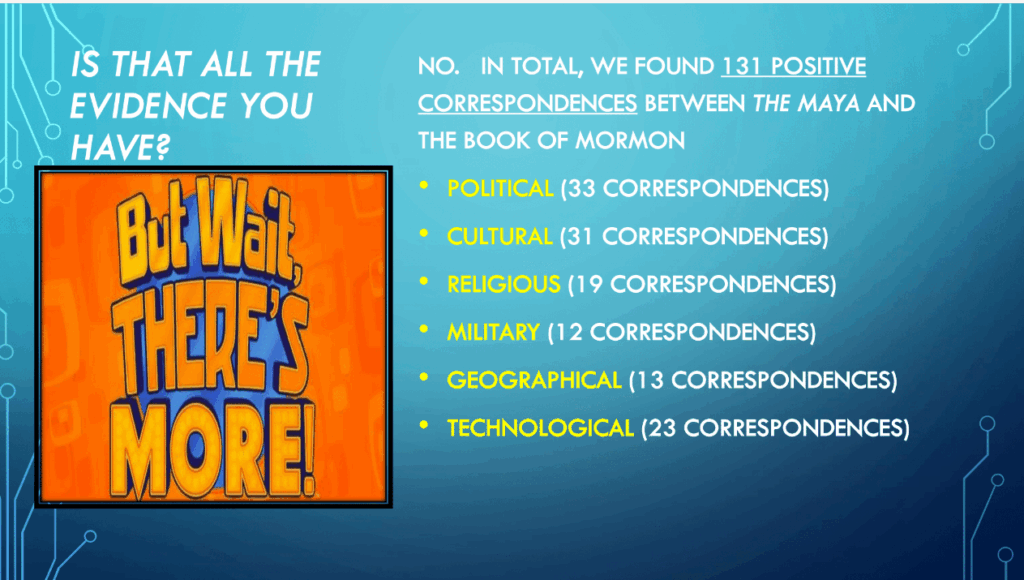

And of course then the question is, is that all the evidence you have?

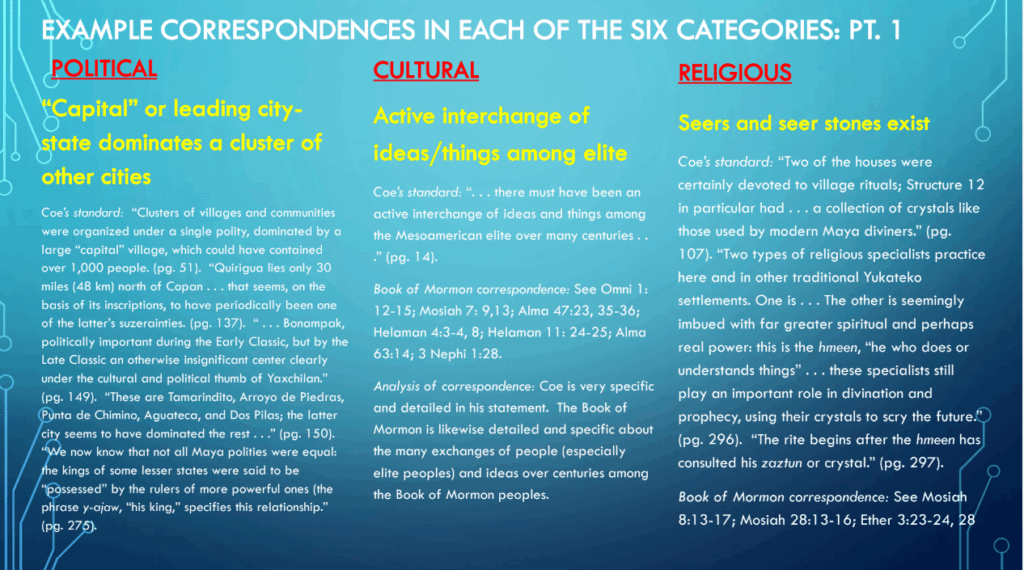

For political: That a capital or leading city-state dominates a cluster of other cities. And the way that we did this, and this actually constitutes the bulk of our paper in Interpreter, is Appendix A, where we summarize all 131 of these. We give the correspondence, we give the standard from Coe’s book, quoting portions of his book here from page 51, for example, “clusters of villages and communities organized under a single polity dominated by a large capital village.” Okay, and then there’s a number of citations that Coe provides. It’s obvious that The Book of Mormon has the same sort of arrangement, Zarahemla, the land Bountiful, on and on, use that same approach.

Cultural, active interchange of ideas and things. Again, Coe’s standard, we quote him, and then we quote The Book of Mormon correspondence, and then we provide a justification, our analysis why we think that that warrants the particular weight of evidence that we provide.

In religious, here’s a good one. Seer, as in seer stones. Coe points out that the Maya had seers and seerstones. They called them Hmeen, I don’t know how to pronounce that word, and obviously The Book of Mormon has seers and seer stones also.

131 Correspondences

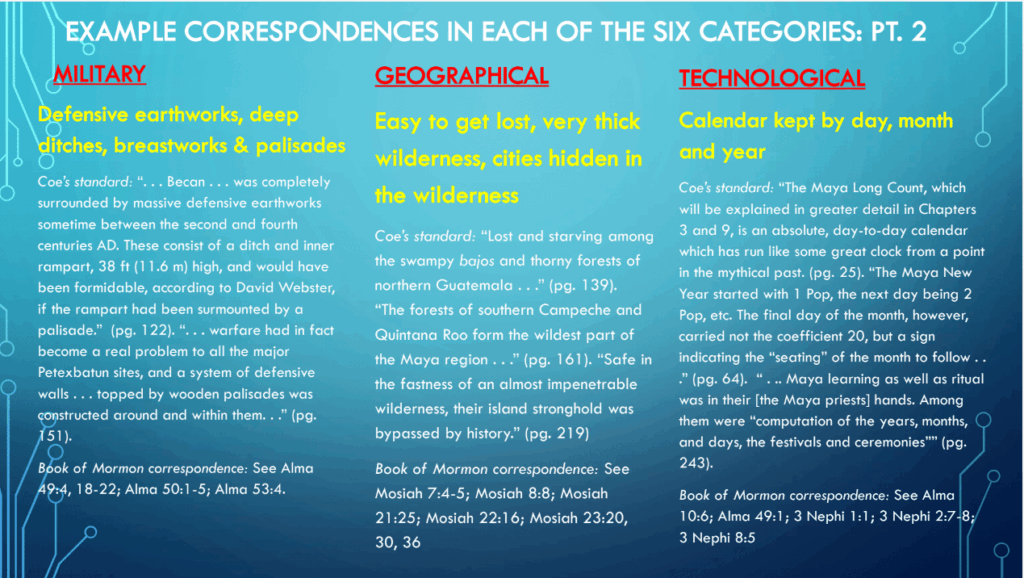

Military, likewise. Defensive earthworks, you’re acquainted with many of these things. Geographical, easy to get lost, very thick wilderness. Coe points out how wild some of the Mayan area is. Then technological–calendar kept by day, month, and year, which is to me, very, very unusual. He refers to both the linear count, the night of the new year. And The Book of Mormon obviously shows, day, month, and year, calendar keeping also.

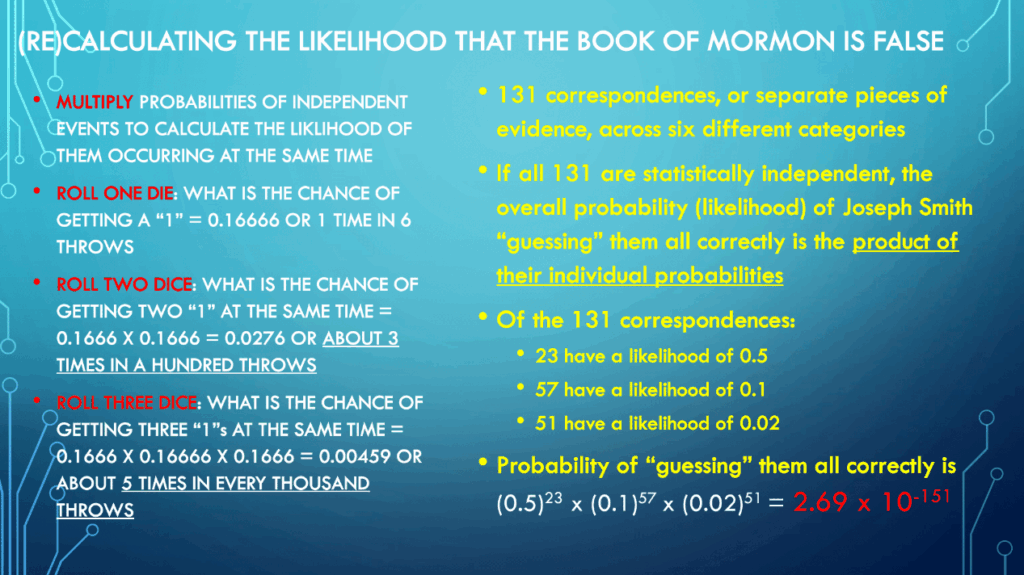

Again, multiply probabilities, independent events to calculate the likelihood of them occurring together, you know, the rolling of the dice, and we apply that same approach here to these 131 correspondences, again, given in detail in Appendix A of the paper, which is supplied to you as part of this, as a PDF copy of that.

If all 131 are statistically independent, then the overall probability or likelihood of also guessing them correctly is the product of their individual probabilities of those 131 correspondences. Twenty-three have a likelihood of 0.5, the weakest evidence 57 we evaluated having a likelihood of 0.1, and 51 have a likelihood of 0.02, strong evidence. Probability of guessing all of them correctly is 0.5 to the 23rd times 0.1 to the 57th power times 0.02 to the 51st power, equals this very, very small number, 2.69 times 10 to the minus 151.

Six Statements of Fact

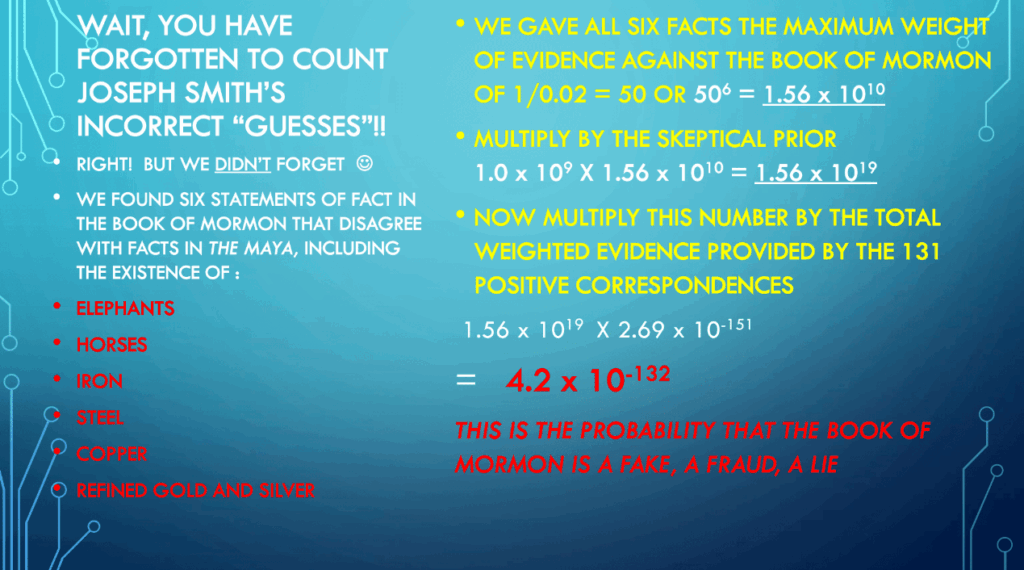

Wait, you forgot to count Joseph Smith’s incorrect guesses.

But we didn’t forget. We found six statements of fact in The Book of Mormon that disagree with facts that were stated in the other book, including elephants, horses, iron, and on and on. We gave all six of these facts the maximum weight of evidence against The Book of Mormon, although we don’t really think they may weight that, but it’s 50 to one, the strongest evidence that we give, so just 50 to the sixth power, this is the number. So we multiply that by the skeptical prior of a billion to one times this number to get a new number.

Now we multiply it by the total weighted evidence provided by all 131 positive correspondences and this is the result (4.2 times 10 to the negative 132 power). The probability of The Book of Mormon as a fake, a fraud, a work of fiction, as Coe obviously believes it to be, and others do too. That’s the problem with The Book of Mormon as a fake according to this analysis.

How Small Is the Probability The Book of Mormon Is a Fake?

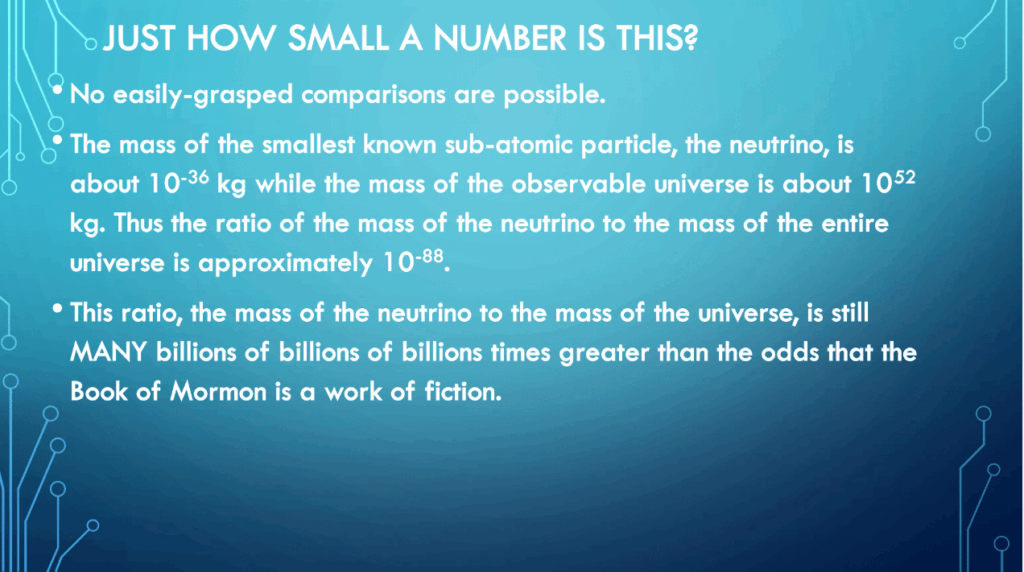

Okay, how small a number is that? Well, good question, there aren’t any easily grasped comparisons. The mass of the smallest known particle is the neutrino. The neutrino has a mass about 10 to the minus 36 kilograms. The mass of the observable universe, that universe that we can see, is about 10 to the 52 kilograms, so the ratio of the mass of the smallest particle to the mass of the entire universe is 10 to the minus 88 power, roughly. Okay, that’s still many billions and billions of billions times greater than the odds of The Book of Mormon as a work of fiction. Okay, so they’re the numbers.

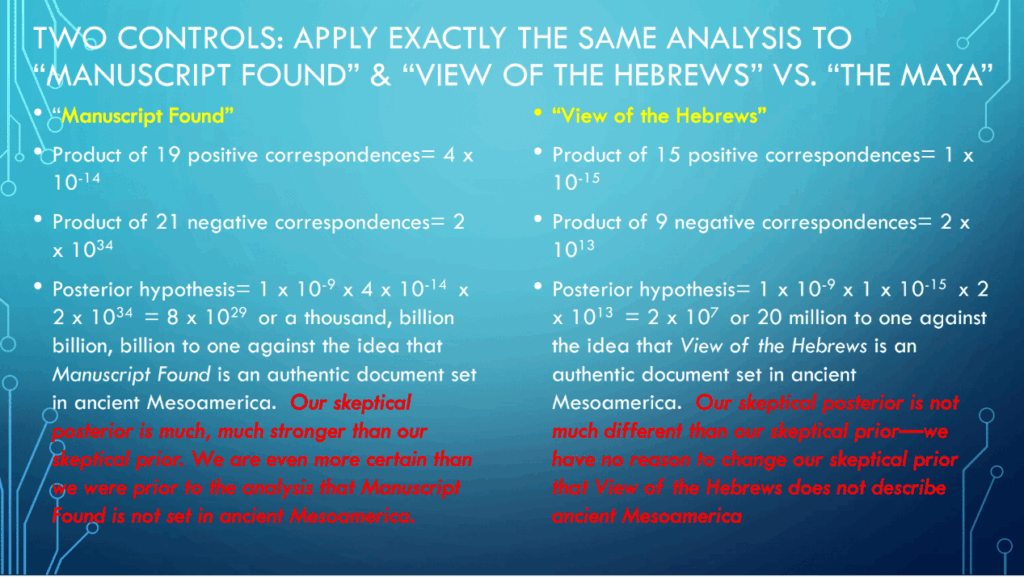

Testing our Method on Control Books

We then took two controls, again, we thank the reviewers for making what we think makes the paper quite a bit stronger. We went through Manuscript Found and compared it with The Maya and found 19 positive correspondences that we rate at this number, and 21 negative correspondences. The posterior hypothesis again, positive times the negative times the prior is still a thousand billion billion to one that Manuscript Found is an authentic document of a mesoamerican nation.

In other words, after the analysis of Manuscript Found, we’re even more convinced than we were to start with that, it’s fake, you know, or if it’s not fake, it doesn’t fit ancient Mesoamerica at all. In fact, it’s excruciatingly bad fiction. I’ve scarcely read worse fiction than that was.

Okay, View of the Hebrews is not written as a fictional book, but the product of the positive correspondences, these are correspondences with The Maya, and the negative correspondences, the posterior again is our prior times the positive correspondences times the negative correspondences, and it’s still 20 million to one against the idea that View of the Hebrews is an authentic document set in ancient Mesoamerica. It really didn’t change our point of view.

Positive and Negative Correspondences

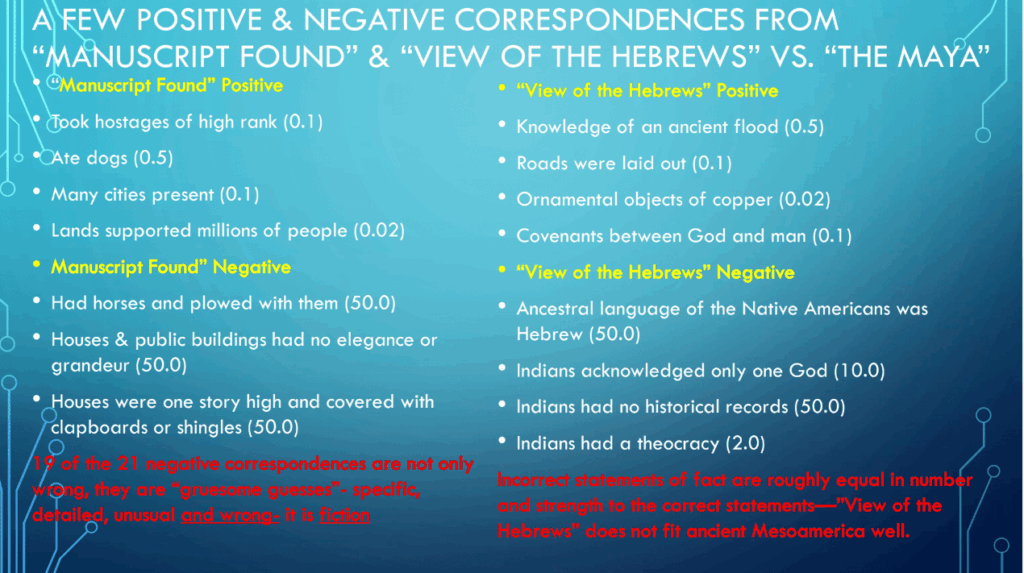

Here are just a few examples of positive and negative correspondences from Manuscript Found and View of the Hebrews. A few positives from Manuscript Found: they took hostages of high rank, they ate dogs, a lot of cities and towns, supported millions of people, which we rated as strong good guesses. Now my negatives: It says they had horses and they plowed with them.

Well Coe says that they never did that, they didn’t have horses, nor did they plow with them. Houses and public buildings had no elegance or grandeur. And actually it turns out that 19 of the 21 negative correspondences for Manuscript Found versus The Maya are not only wrong, they’re gruesome. They’re specific, they’re detailed, they’re unusual, and they’re wrong.

Positive comparing for View of the Hebrews: the knowledge of an ancient flood, they laid out roads, had ornaments of copper, and taught that covenants exist between God and man. Negative here: ancestral language of the Native Americans was Hebrew, and there’s a number of other negative correspondences. They’re roughly equal in number and strength for the correct statements so the View of the Hebrews may be a more or less accurate view of some group of ancient Indians, but not ancient Mesoamerican Indians, at least as far as what’s illuminated by Coe.

How Strong Are Our Conclusions?

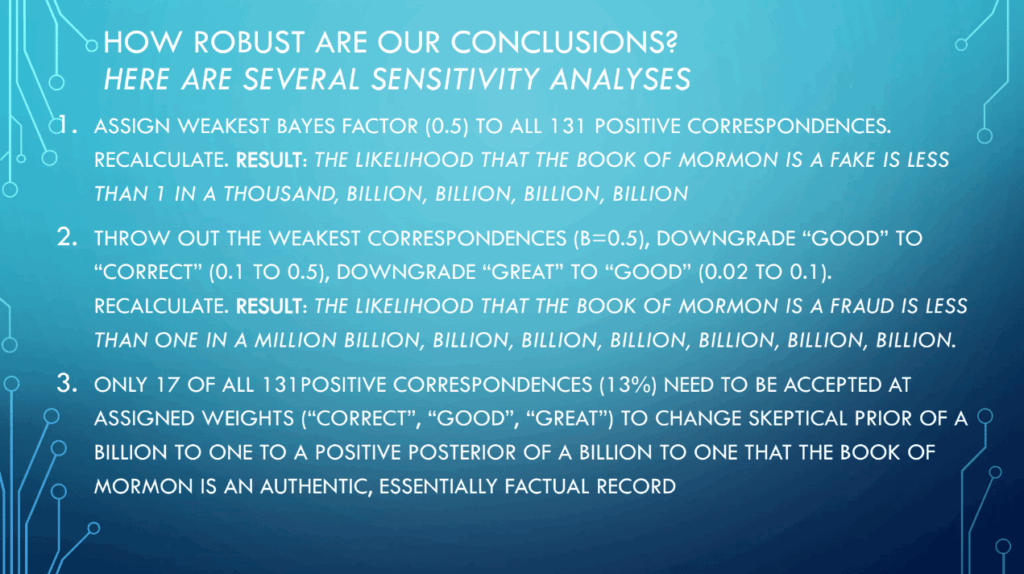

So how robust are our conclusions? Here are several sensitivity analyses. We assigned the weakest base factor to all 131 positive correspondences so that we just consider them as evidence but not really strong evidence. Recalculated, the likelihood The Book of Mormon is a fake is still less than one in a thousand billion billion billion billion. It didn’t really change how we view The Book of Mormon.

A sensitivity knowledge, you can do, we threw out all of the weakest correspondences, and this was one of the suggestions by one of the commentators to our article. We threw out the weakest correspondences which is 0.5, we downgraded the good to correct, and downgraded great to good. In other words, all the 0.5 were thrown out, all the good were just downgraded from 0.1 to 0.5, and great from 0.02 to 0.1, and still the likelihood that The Book of Mormon is a fraud is enormously small, very, very small.

So a question you can ask is how many positive correspondences do you need to change your skeptical prior, the billion to one, that The Book of Mormon is a work of fiction, to a positive posterior of a billion to one that The Book of Mormon in fact is an authentic ancient record. And the answer is 17 out of those 131 you need to accept their assigned weights. So it’s essentially a factual record now.

Summary

Some summary because this is worth going over.

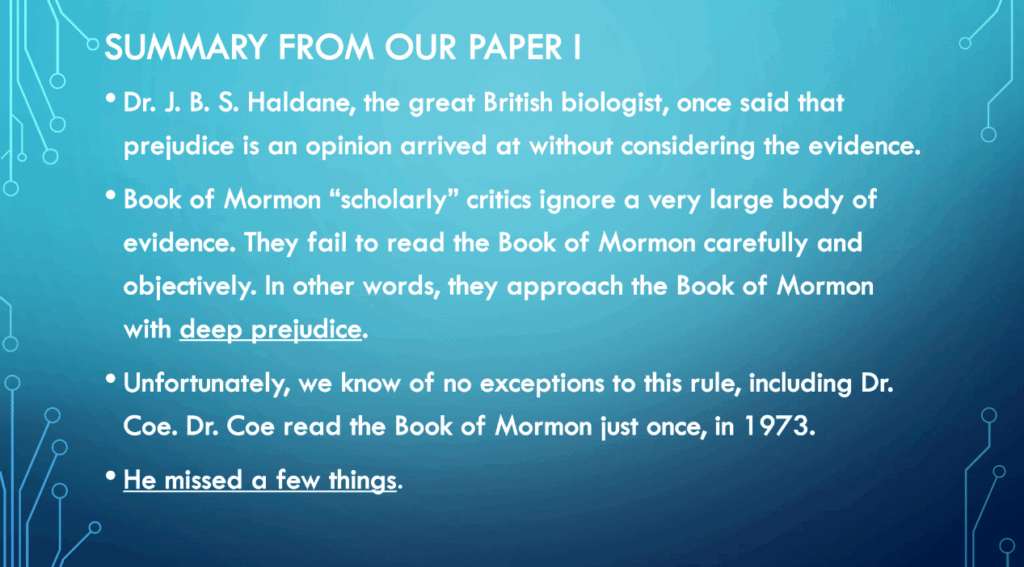

Dr. J. B. S. Haldane, a great British biologist, once said that prejudice is an opinion arrived at without considering the evidence. Book of Mormon scholarly critics ignore a very large body of evidence. I don’t know of any exceptions to that rule. The critics approach The Book of Mormon with deep prejudice. Dr. Coe read The Book of Mormon once in 1973, it’s a totally inadequate scholarly effort. So he missed a few things.

Our Paper

From our paper:

- While Dr. Cole was a great Mayanist, his knowledge of Book of Mormon is just appallingly deficient. He didn’t pay the price that any scholar needs to pay to offer a credible opinion. He didn’t know The Book of Mormon.

- There are at least 131 correspondences. In this article that we wrote we cited 151 separate pages of his ninth edition of The Maya, which has roughly 280 pages of text. Well over half of the page’s of Coe’s book contained facts that correspond to the facts referred to in The Book of Mormon.

- If you carefully read The Maya and The Book of Mormon, I think you can’t avoid noticing the many correspondences between the two books. They’re just so obvious.

- Dr. Coe’s opinion, and this is quoting him from his 1973 Dialogue article, “The picture of this hemisphere between 2000 BC and AD 421 presented in the book (The Book of Mormon) has little to do with early Indian cultures” is simply not supported by the evidence provided in his own book. His statement is not supported by the evidence that he provides us.

- We find that early Mesoamerica has a great deal to do with The Book of Mormon, a very great deal to do with it, and we feel very strongly that the cumulative weight of these correspondences, analyzed using Bayesian methods, provides what is effectively overwhelming support for the historicity of The Book of Mormon as an authentic factual record set in ancient Mesoamerica.

Where Did The Book of Mormon Take Place?

Now let me just address this issue regarding what the specific geographical setting of The Book of Mormon is. We didn’t set out to answer that question and perhaps we haven’t answered it here, we’re not interested. Brian and I are just interested in facts. As far as we’re concerned though, the facts as summarized in Dr. Coe’s book provide overwhelming evidence of The Book of Mormon as an authentic factual record set in ancient Mesoamerica, and if there are some other plausible explanations or settings, they would need to have equivalent or greater supporting evidence than what we presented here and it must include both positive and negative evidence. Thou shalt not be a cherry picker.

So in effect, we believe that the book, The Maya, describes the same world as The Book of Mormon. How did Joseph Smith guess that? The answer of course is, he didn’t. The Book of Mormon is an authentic record, we believe set in ancient Mesoamerica. We look forward, hopefully, to having some questions from this audience. Thank you very much.

Audience Q&A

Scott Gordon:

Thank you very much. I have a few questions here. First of all, have you considered running a similar analysis on other books about ancient America?

The Dales:

Just real quickly, yes. In fact we’ve submitted it for publication. There is a book written by Stanford University Press called The Ancient Maya and published in 2005. We’re comparing that as part of the second paper in our series, in addition to all nine editions of Coe’s book. Kirk Magleby from Book of Mormon Central suggested that a second paper could be valuable by demonstrating that correct scientific facts or authentic historical documents tend to accumulate positive evidence over time. Dr. Cole’s nine editions of his book on the Maya were analyzed to observe this accumulation. So the answer is yes.

Scott Gordon:

This question you answered in the last slide of your presentation. I’m going to let you restate what your answer is a little bit. It says Could this method possibly be used to evaluate the likelihood of different geographic settings for The Book of Mormon, for example the Heartland theory, Peru, Baja California, etc.?

The Dales:

So the short answer is yes. In Bayesian methods one thing that you can do is compare multiple hypotheses. So in this we basically just compared two hypotheses, is The Book of Mormon a work of fiction or is The Book of Mormon non-fiction? So those were the two hypotheses we were comparing, but you certainly can set up multiple hypotheses and accumulate evidence over all of those hypotheses and wind up with an overall opinion of which hypothesis best fits the evidence.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you. When you first published your paper in the Interpreter it was met with a flood of comments, both positive and negative. Has the response to your paper prompted you to alter or refine your methodology in any way, or your conclusions?

The Dales:

No. The conclusions stand unchanged. One of the things that I would like to do is probably a third paper that looks at the question of independence of the correspondences. We think that was a valid reservation because some of these correspondences may not be statistically independent. Once we’ve got the second paper in publication, I’ll start on the third one and try to get multiple inputs to look at how independent all 131 correspondences are. So that would be an update.

Brian Dale:

Yeah, just to confirm, there were many, many objections. By far the most objections on the discussion thread were not really valid, but I feel that the independence objection that was raised, was a valid objection. If you can make the assumption of independence, then the math becomes very easy. So the math that we described was very approachable and easy to explain, but it also relies on that independence assumption. As soon as you remove that independence assumption, the math becomes much more difficult and you have to use basically computer simulation methods that are in some sense just much less accessible and understandable. But it can be done and has been done in the scenario of weighing evidence for a trial. So there is precedent for doing this sort of a more complicated approach. Thank you very much.

Scott Gordon:

Next question here: Elephants, horses, iron, steel, copper, refined gold, and silver were items you mentioned that disagreed with Michael Coe’s book. Do you personally believe that there are other ways to account for these things in The Book of Mormon?

The Dales:

Oh, yeah. I’m aware that there are good answers to all of those. But again, our point here was to simply take the body of information in Dr. Coe’s book and compare it with the body of information because we accepted what he said in The Maya as true, okay? And then we compared The Book of Mormon with that. But yes, I think I’m pretty well aware of most of it. And the other thing is that the approach that we took with those likelihoods inherently includes both. So it includes both ways. It’s important to understand that those likelihoods are not themselves probabilities. They’re ratios of probabilities. So the ratio of the probability of seeing that statement if it were a work of fiction to the probability of seeing that fact if it was a work of nonfiction. And, you know, you can have many, many different reasons, many different justifications that could explain why that denominator is non-zero. And that’s essentially what all of these explanations for how, you know, horses could be described in there and not have been found archaeologically. You know, there’s many ways that you can explain that, and that would be included in that denominator. Thank you very much.

Scott Gordon:

So here’s another one, and this goes back to your question of whether you’ve written enough papers yet or not. Do you have any plans to run an analysis on Napoleon’s Late War, like you did on View of the Hebrews and Manuscript Found?

The Dales:

No, I mean, I could do that, but I don’t feel any driving force. The Spirit would have to kick me awful hard in the seat of the pants to do that, as I got kicked to do this. We certainly encourage anybody else that must do that to go right ahead.

Scott Gordon:

Okay, here’s another one on geography. Geography seems to be a big question thing, and this is the last question I have. Have you done this analysis for a North American location for Book of Mormon?

The Dales:

I‘ve watched several videos by main proponents of the North American theory, and I’ve kind of compared their database. Unfortunately, they only consider parallels; they don’t look for anti-parallels. And there are a number of anti-parallels. But let me just say, and hopefully without making anybody upset here… in case those folks are listening in… I do it all the time, I make people upset. So don’t worry. Okay, well, I’ll just let you have it then. I don’t know any other valid explanation for Third Nephi chapter 8 than earthquakes and associated volcanic activity. I don’t know how else you get those phenomena. And we have not had active volcanoes in Eastern North America for 100 million years, and the geology is just really clear on that; you can’t get around that. I think that fact by itself. As far as Peru and other things are concerned, I’d have to look at a body of evidence, but again, I don’t wish to offend anybody, but if they could do a similar analysis, consider both pros and cons, both parallel, you know, both points of evidence that forward and go against their hypothesis, do something similar, I’ll consider it. But until then, I think this is really overwhelming evidence that The Book of Mormon is an authentic record set in ancient Mesomerica. I don’t see how you get around that, so I’d have to see equal or greater evidence.

Scott Gordon:

This last question I have, I think you’ve already answered this, but it’s along similar things. Have you thought to use this Bayesian method to compare The Book of Mormon to the Hopewell Indians?

The Dales:

That’s Eastern North America, and I rule it out or near rule it out again by the fact that, what physical phenomenon it accounts for what happened in 3 Nephi chapter 8. Jerry Grover did a great job of summarizing that. Hugh Nibley even back in his day did it. I don’t think you can get anything other than a volcano and the associated earthquakes to line up with those facts. And we have not had volcanoes in Eastern North America for hundreds of millions of years; that’s a geological fact. Okay, so Hopewell Indians, that’s where they were. So nope, sorry, Hopewell culture doesn’t fit. Yeah, but again, this methodology certainly could be applied to do this type of analysis, you know, that that would be instead of being a strong evidence for it would be strong evidence against, but there could be other evidence. And so this sort of analysis is adaptable to pretty much any hypothesis. And so if that’s a hypothesis that you have, you can follow the same procedure and come out with an answer, and you can compare different hypotheses and see which is stronger. So let’s do an exercise that can be done. I don’t think we plan on doing it, though.

Scott Gordon:

I really appreciate your time. I appreciate you beaming into us from afar and participating with this conference, and with that, that’s the end of our questions. And thank you very much.

Endnotes & Summary

Jeffrey’s talk, What Do We Treasure?, explores how different worldviews shape our understanding of the gospel and influence what we see as the “good life.” He identifies four primary worldviews—the Expressive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, and Redemptive Gospel—each defining success and fulfillment in different ways. While Expressive Gospel prioritizes self-expression, Prosperity Gospel equates righteousness with financial success, and Therapeutic Gospel emphasizes emotional well-being, the Redemptive Gospel teaches that true success is found in reconciliation with God. By examining these perspectives, Jeffrey warns that misplaced values can lead people to misunderstand the gospel’s true purpose.

The talk highlights how Gospel Counterfeits arise when cultural influences subtly redefine gospel vocabulary and shift the focus away from Christ. He provides examples of how phrases like non-judgmental love and authenticity take on different meanings depending on the worldview, leading to confusion and potential spiritual drift. Many individuals, even those originally converted to the Redemptive Gospel, gradually adopt cultural values while still using gospel language. This process results in a faith that, while still appearing religious, may no longer align with the teachings of Jesus Christ.

Jeffrey concludes by emphasizing the need for spiritual discernment and doctrinal clarity. While Gospel Counterfeits persist because they offer comfort, validation, or worldly success, the Redemptive Gospel calls for transformation through Christ. Faithful discipleship requires prioritizing God’s values over societal expectations, measuring spiritual success by personal sanctification rather than external achievements. By recognizing and rejecting distorted versions of the gospel, believers can ensure their faith remains rooted in eternal truths rather than cultural trends.

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 9, 2024

- Duration: 26:31 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2024 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: Redemptive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, Expressive Gospel, gospel counterfeits, authenticity, covenant-keeping, LDS worldview, personal fulfillment, character transformation, reconciliation with God, faith crises, gospel vocabulary, Maslow’s hierarchy, LDS apologetics

Common Concerns Addressed

Joseph Smith guessed details of Mesoamerican culture.

Bayesian analysis shows the statistical impossibility of this level of accuracy occurring by chance.

The Book of Mormon contradicts known archaeology.

Critics like Coe failed to engage with the actual content; when properly compared, substantial parallels emerge.

Apologetic Focus

Faith supported by data and rigorous methods.

Statistical validation of scriptural authenticity.

Rational responses to historical and archaeological criticism.

Explore Further

coming soon…

Share this article