“Written in the Books of Moses”: Mosaic Authorship and Authority in the Book of Mormon

August 2023

Summary

Dr. Avram Shannon discusses the prominence of Moses in The Book of Mormon, where Moses is primarily linked to the law of Moses, appearing frequently alongside teachings of salvation through Jesus Christ. Shannon explains that while Nephi and the Nephites revered the law of Moses as essential to keeping God’s commandments, the Book of Mormon suggests they viewed Moses more as the authority behind the law rather than its direct author. He encourages readers to approach scripture with openness to unanswered questions and to let both the Bible and The Book of Mormon work together to deepen faith in Jesus Christ.

Introduction

Scott Gordon: We’re very pleased to have Avrahm Shannon here speaking. Dr. Shannon was born in Quantico, Virginia, and spent most of his life in Virginia. He served a mission first in the Oregon Portland Mission and then in the Washington Kennewick Mission after the Oregon Portland Mission was split. Dr. Shannon earned his BA in Ancient Near Eastern Studies from Brigham Young University, a Master’s in Jewish Studies from the University of Oxford, and a PhD in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures with a graduate interdisciplinary specialization in religions in the ancient Mediterranean from Ohio State University. He has nine children, and he’s taught a number of courses. With that, I’ll turn the time over to Avrahm Shannon.

Presentation

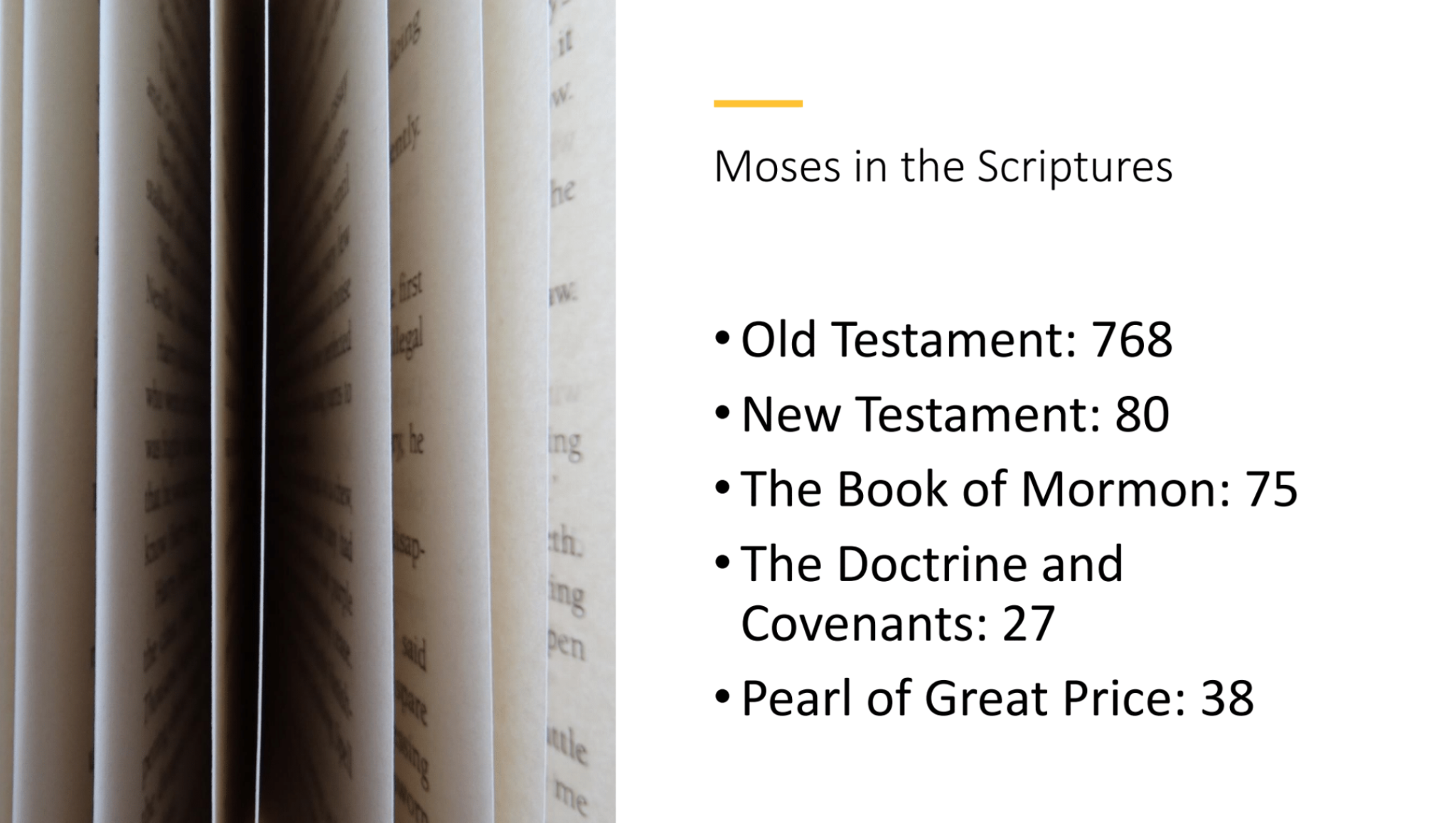

Today, I’m going to be talking about Moses, but mostly about Moses in terms of the law and what that means and the implications of that for The Book of Mormon. The first thing to frame this discussion is to recognize that Moses is a really, really big deal in the scriptures in terms of total mentions.

The Prominence of Moses in Scripture

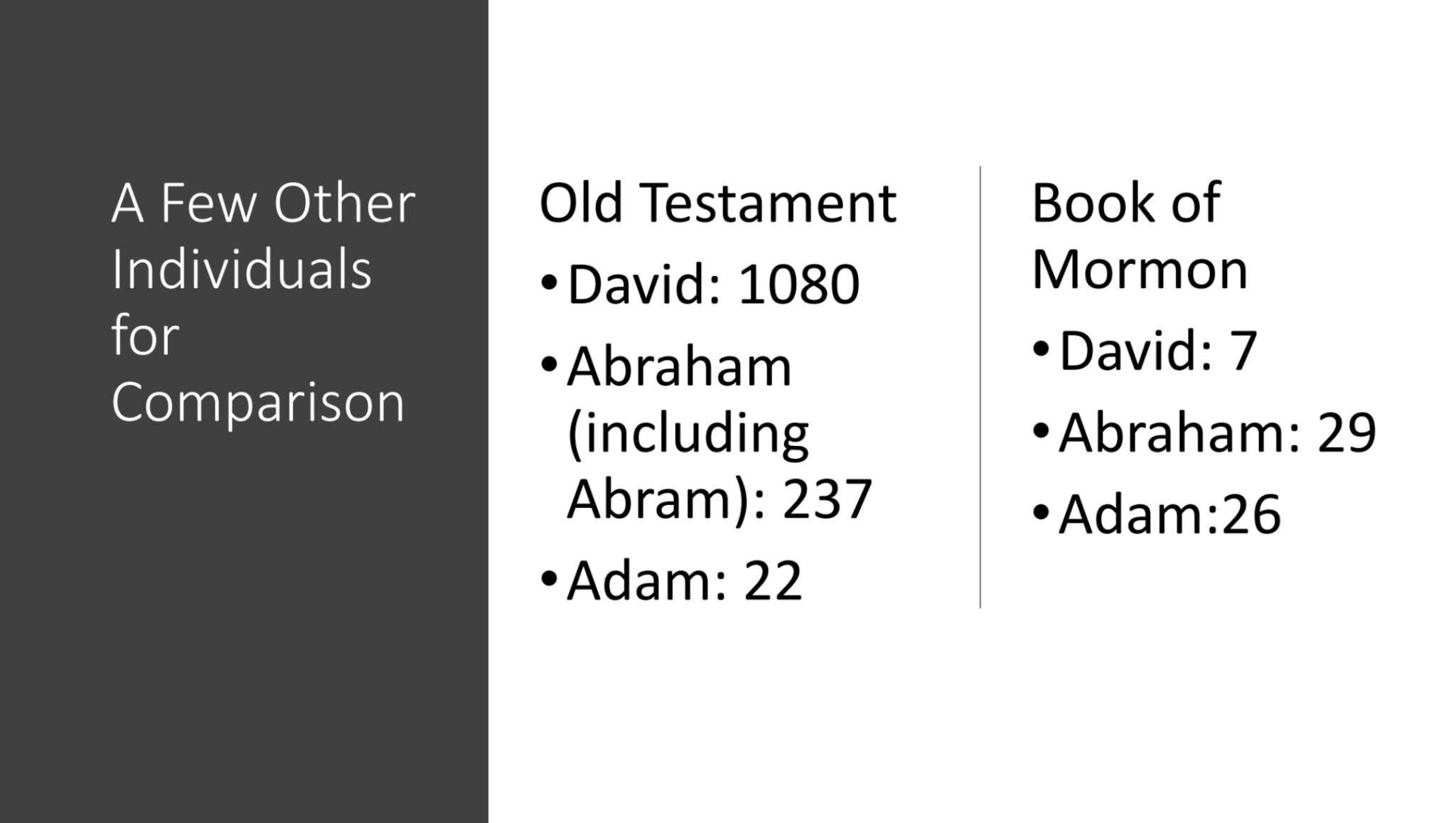

In our English scriptures, Moses appears frequently: 768 times in the Old Testament, 80 in the New Testament, and 75 in the Book of Mormon, which kind of shows the importance there. The only other single figure from the Old Testament mentioned in the Book of Mormon who even comes close to the number of mentions in all scriptures to Moses, is David.

David is prominent in the Old Testament but less so in the Book of Mormon. Other notable covenant figures, like Abraham, appear 237 times, and Adam, a mere 22 times in the Old Testament, and that’s assuming correct translation in all places, which is an assumption.

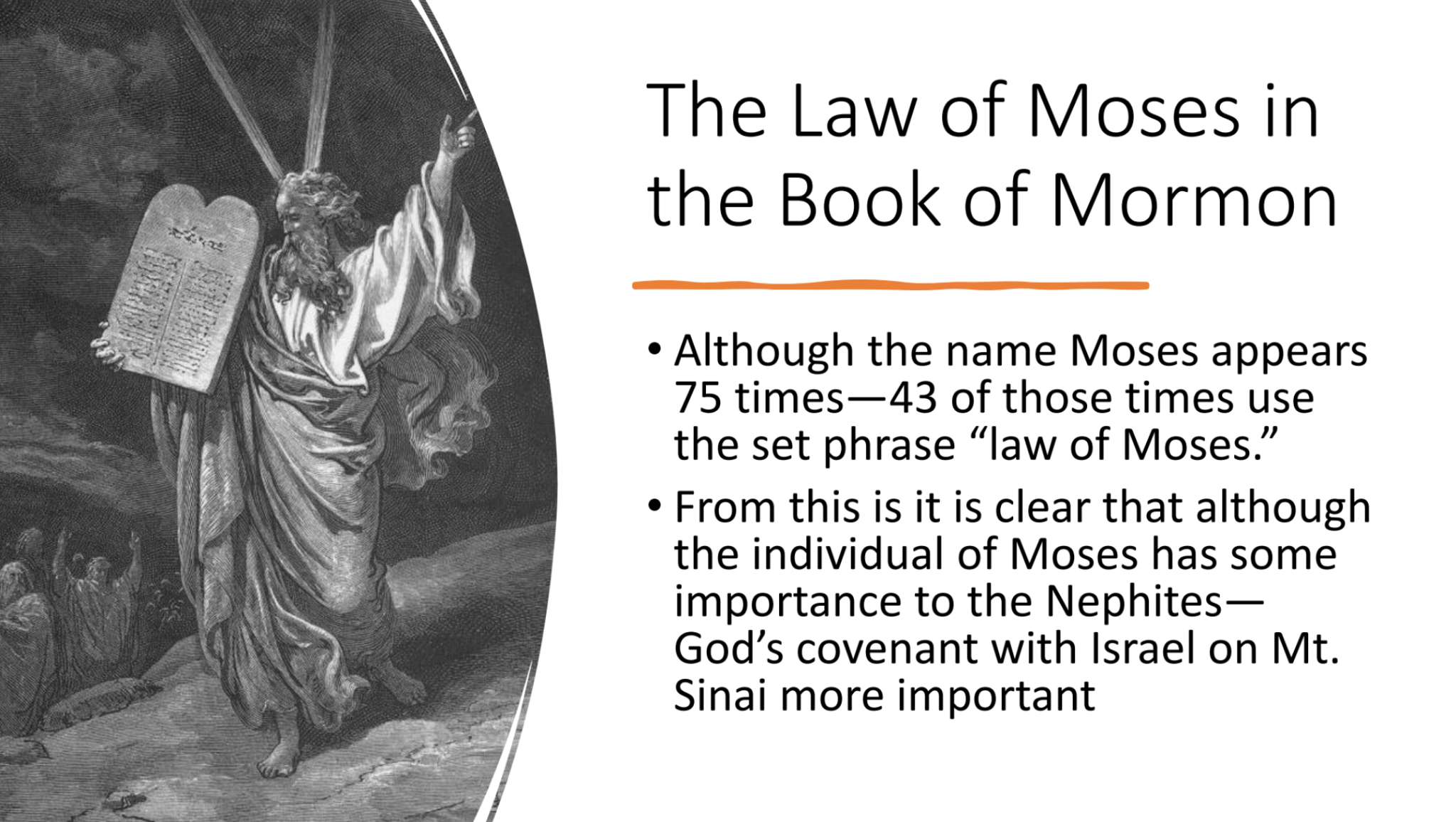

When we talk about scripture, we need to recognize the importance that Moses plays within it, and part of that importance is, of course, his association with the Sinai Covenant, often referred to in scripture, especially in the Book of Mormon, as the law of Moses.

Law of Moses in the Book of Mormon

In the Book of Mormon, Moses appears 75 times, and of those, 43 instances include the set phrase “law of Moses.” This means that about 57% of the mentions of Moses are directly related to the law of Moses. This illustrates how strongly the Book of Mormon associates Moses with the law and the Sinai Covenant. In fact, this seems to be one of the primary reasons why the Nephites refer to and bring up Moses.

And so, today we’re going to talk really about law. As Christians, we often overlook it, perhaps because it seems unrelated to us, and also because Mormon, as the editor, doesn’t emphasize these details. However, the law associated with Moses looms very large in the Book of Mormon. The Book of Mormon represents the product of a society and culture that derives from the ancient Kingdom of Judah. This means they lived and practiced a distinctive version of the worship of Jehovah, including observing a version of the law of Moses.

Of course, the Book of Mormon represents, in many ways—and it tells us this explicitly—a hybrid text, where the Nephites lived the rituals of the law of Moses and preached about salvation through Jesus Christ. Actually, as you read the book, you find that for them, these are, in many ways, the same point.

For the majority of the book, the Nephites lived the rituals of the law of Moses (and sometimes the Lamanites) and observed sacrificial laws. The reason we know this, of course, is because Jesus ends these practices in 3 Nephi 15.

This creates some interesting things, because as we deal with the law, we then have to deal with what that looked like for the Nephites.

As we think about the association between Moses and the law of Moses, traditionally that association has suggested that Moses was the author of all the materials currently identified as the law of Moses in our current Bible—that is, Genesis through Deuteronomy in our Bibles.

This view has a long history, but since around the 19th century, scholarly consensus has pushed against Mosaic authorship, asserting that he was not the author of any of the materials in our current Bible.

Latter-day Saints, again, have a nuanced view of scripture, which we’ll discuss more in our time together. We have tended to uphold traditional views of authorship, sometimes simply because they are traditional.

There is good evidence from scripture to associate the law and covenant with the person of Moses, and we’ll explore that, however, as we work through the scriptures together, including the Book of Mormon, authors do not consistently associate Moses with the specific writing of the law of Moses, but rather consistently ascribe to Moses the authority of the law.

And so we’re going to try to think through the differences between authorship and authority, and how the Book of Mormon works through those categories while considering what they’re doing with their inherited text of the law of Moses.

The Law on the Brass Plates

As we think about the importance of the law, there’s a great example–going all the way back to 1 Nephi 4—where Nephi talks about obtaining the law, specifically going back to get the brass plates.

Of course, there’s that lengthy experience in 1 Nephi 4, where he’s trying to explain to himself why it’s acceptable to kill Laban. He works through various reasons, one of which is based on the idea that, as it says,

‘Inasmuch as thy seed shall keep my commandments, they shall prosper in the land of promise. Yea and I also thought that they could not keep the commandments of the Lord according to the law of Moses save they should have the law. And I knew that the law was engraven upon the plates of brass.’

So what we have here is Nephi explicitly saying that one of the primary reasons he believes they need to go back and get the brass plates is so they can have the law. So we know, on some level, that the law is engraven on the plates of brass.

However, this is something we need to think about because we don’t have access to the brass plates. Honestly, I would cut off both my legs to have access to the brass plates, but since we don’t have them, we have to look at what we do have and work with that.

We know that the Lehites had access to some version of the law available in the 7th century BC. We have some initial textual clues. For instance, in 1 Nephi 5, after they retrieve the plates, Father Lehi finds that they contain the five books of Moses. We’ll discuss what that means, but essentially it provides an account of the creation and also of Adam and Eve, our first parents.

So, the explicit discussion of what’s included in these five books of Moses, corresponds to about the first four chapters of Genesis. In the law of Moses, as we currently have it, there are approximately 187 chapters, which means that Lehi’s description of what’s in the five books of Moses is unfortunately not very useful to us because it doesn’t tell us much beyond these first four chapters.

This is a recurring issue we have to work through in Book of Mormon studies in general, as we’ve seen in some of our previous presentations. I often like to talk to my students and quote the famous Harvard Semiticist scholar Thomas Lambdin, who used to say— not about the Book of Mormon but other areas of study—that ‘We’re ‘working with no data, but we may conclude on certain levels.’

For Book of Mormon scholars, we’re not working with no data, but we do have a fairly limited data set, but ‘we may conclude.’ So, it’s this process of working through and trying to figure out what we can and therefore can’t say about it.

So this actually reflects this notion of the five books of Moses. Again, we do not have access to the brass plates. It is easy, therefore, to assume that these five books are Genesis through Deuteronomy. But does the Book of Mormon say that? It doesn’t. Part of this involves stepping back and thinking through the assumptions we make. We don’t know the specific divisions, and this is important, and why we want to talk about this.

The Documentary Hypothesis

As I alluded to at the beginning, biblical scholarship for over a century has seen examples of sources and editing that go into the production of all scripture, but especially within what we call the Documentary Hypothesis, which we’ll talk about briefly.

In some ways, the specifics of this aren’t crucial to our argument, but you may be familiar with the concept, famously promulgated by the German scholar Julius Wellhausen. This idea suggests that we can identify four distinct strands that contribute to the creation of the Pentateuch.

Wellhausen organized these strands into a historical schema:

- ‘J,’ the Yahwist, is the earliest source, characterized by the use of the divine name Yahweh or Jehovah;

- ‘E,’ the Elohist, is a northern source characterized by the use of the name Elohim, or God;

- ‘D,’ the Deuteronomist, is characterized by the themes and language typical of Deuteronomy; and

- ‘P,’ the Priestly strata or Priestly source, which Wellhausen thought was the most ‘Jewish’ of all the sources (though as a German, he didn’t mean ‘Jewish’ as a compliment).

Wellhausen felt this material was a degeneration of ‘true religion.’ This perspective reflects certain sentiments present in Germany at that time.

There is some disagreement and ongoing discussion, as with all scholarly positions, so this is not a rigid or universally accepted view. However, the idea of the law of Moses being the result of various sources has broad scholarly consensus.

Even if you’re pushing against it, you’re working broadly in the schema. And this can sometimes be seen as a difficulty for the Book of Mormon, because some of these sources—and certainly the final form it comes to, date to after the Book of Mormon starts.

The Book of Mormon begins precisely in 597 BC, during the first year of Zedekiah, king of Judah. Our final forms date to after the Babylonian exile, around 538 BC. This could seem to challenge some of the Book of Mormon’s historical claims.

However, I want to suggest to you that this isn’t a necessary conclusion even if you accept the Documentary Hypothesis as articulated by Wellhausen. This schema for understanding the composition of the law of Moses has almost no bearing at all on what’s happening in the Book of Mormon.

For the remainder of our time, we’ll discuss this further, particularly because the Book of Mormon makes substantial claims about Mosaic authority but very few about Mosaic authorship.

Process of Scripture Creation

My friend and colleague Daniel Belnap has observed that as readers of scripture, we tend to view scripture as a monolithic entity. Part of our approach involves recognizing that all scripture undergoes a process of editing and what we call redaction.

Dan Belnap says, ‘Like the Book of Mormon, the Bible in its current form is best understood to consist of original authorial writings as well as redacted text, the latter having earlier been edited or commented on by later editors.’

For example, we know that the Book of Mormon is a collection of sources gathered over a long period of time, which were then compiled, edited, and commented on by an inspired editor. We should not be surprised to see a similar process happening in the biblical text; in fact, we should expect a similar process within the biblical text.

Because we don’t know precisely what was on the brass plates, and likewise, we don’t know exactly when the Bible, as we have it, took its current form, we cannot know the exact arrangement of what we call the law of Moses material in the Book of Mormon or what it looked like on the brass plates.

We know it included the story of Adam and Eve and the creation, and we know it could be divided into five sections, as stated explicitly in the text, but we lack further specifics regarding the process and arrangement.

I’m actually working on a project where I’m examining and discussing all we can discern about the presence of laws in these texts. Notably, we do find examples of all four strands, at least I have found examples of all four strands.

However, when we consider what the Bible says about authorship, it’s essential to note that the Bible itself never explicitly claims Mosaic authorship for the law of Moses. In fact, as you read it, it’s always in the third person: “And God said to Moses,” and does this. So it’s a story about Moses—about Moses receiving law, about Moses presenting revelation. It is not presented as a story of Moses saying, “I am doing this.”

Even Moses 1, So, restoration scripture, and this is just one example of it, Moses 1, our revelatory preface to the JST (Joseph Smith Translation) to Genesis:

“The words of God, which he spake unto Moses at a time when Moses was caught up on an exceedingly high mountain. And he saw God face to face, and he talked with him, and the glory of God was upon Moses; therefore Moses could endure his presence.”

Note here again, this is in the third person; this is about Moses. This is not written by Moses.

The Pentateuch, as we have it, presents traditions about Moses that have then been redacted and compiled. And this actually feeds into the Book of Mormon as it kind of works through this and thinks about it.

One thing that’s important for us to remember as we read this is—again, this is part of our tendency to kind of sort of level things here a little bit–so we date Moses to roughly 1200 BC, give or take—he’s hard to date. We date the start of the Book of Mormon to, as I said, 597 BC, the first year of the reign of King Zedekiah, king of Judah.

That means there’s about a 600-year gap between the person of Moses and the start of the Book of Mormon, and therefore the presentation on the brass plates.

My point here with this is that Nephi probably doesn’t know much more about Moses as a person than you or I do. Because looking at 600 years, even though they’re both, you know, older than us, it’s still a huge gap between the Lehites and Moses.

Mosaic Authorship

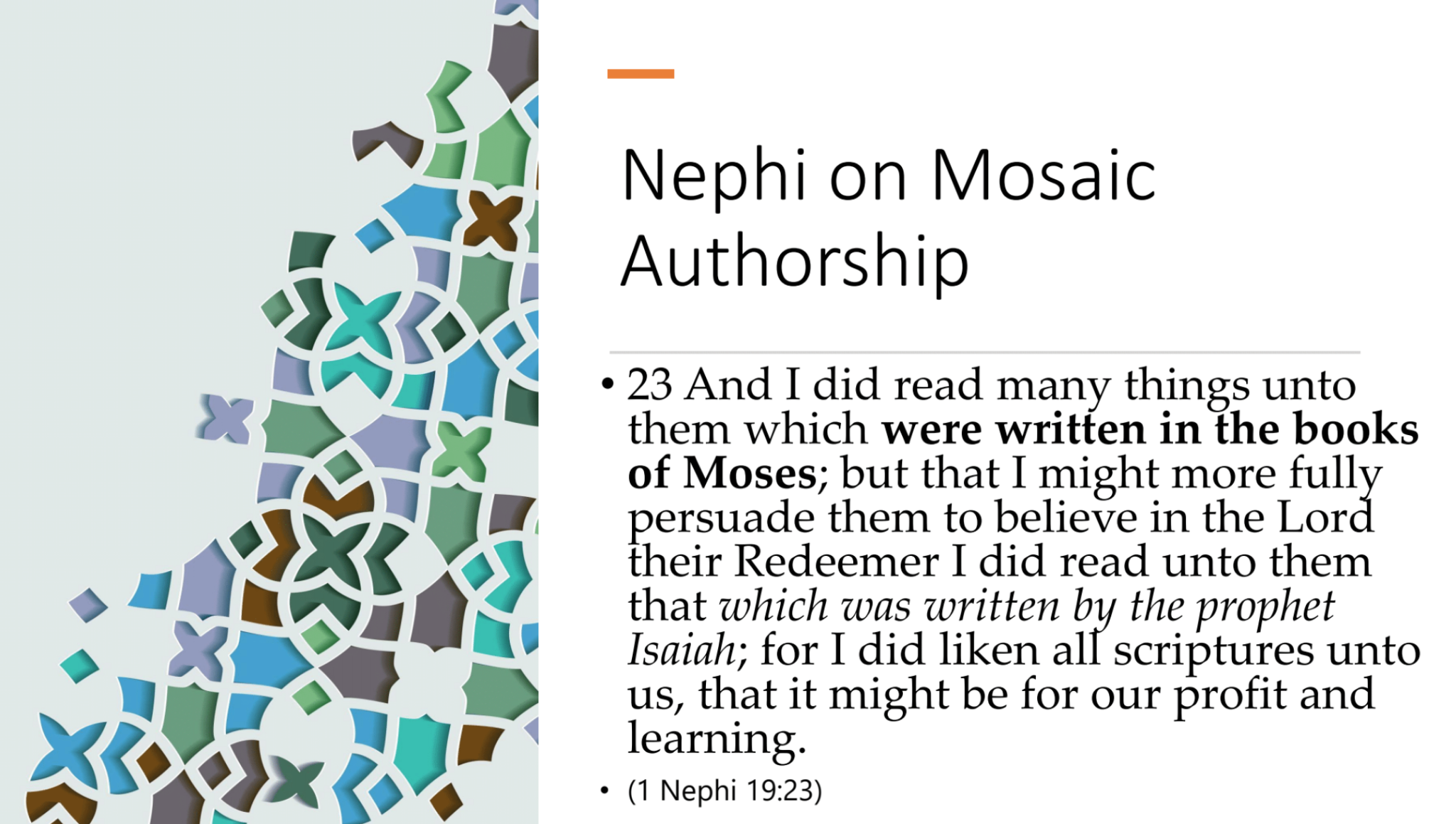

Now, there’s an intriguing verse in 1 Nephi 19 that I want us to consider. So, 1 Nephi 19:23—you’ve heard this a thousand times: ‘And I did read many things which were written in the books of Moses, but that I might more fully persuade them to believe in the Lord their Redeemer, I did read to them that which was written by the prophet Isaiah, for I did liken all scriptures unto us, that they might be for our profit and learning.’

Look here at the distinction Nephi seems to be making: ‘I did read the things which were written in the books of Moses, but I did read that which was written by the prophet Isaiah.’ He seems to indicate authorship here for Isaiah in ways that he doesn’t for Moses, suggesting that in Nephi’s time, he is aware of a compositional project that goes into what he calls the ‘books of Moses.’

As we think through titles and things like that, sometimes a scriptural book will have a title like 1 Nephi because that’s the author of it. But sometimes, like Samuel or Alma, a scriptural book will have a title because of the main character in it or because of an association with it.

Nephi’s identification of the law as the ‘books of Moses’ does not automatically mean that Nephi believes it was all written by Moses. In fact, this language here in 1 Nephi 19 suggests to me that he may be aware of some of the compositional and compilation notions that come into the text.

Now, none of this is to suggest, for Nephi or for Latter-day Saints, that the Pentateuch, or the law, does not legitimately derive from God and Moses. There is no sense of that anywhere in the Book of Mormon. Nephi is reading to them from the law, from the books of Moses, in order to persuade them to believe in Jesus, and we see that happening in multiple places across the Book of Mormon.

Some of that, I think, relates to Abinidi’s really cogent observation where he quotes Moses, ‘Have not all the prophets prophesied more or less of these things?’ Sometimes it’s more, sometimes it’s less, but there’s this idea of legitimate authority here.

The Book of Mormon stands strong on the notion of the law coming from God through Moses at Mount Sinai. It’s less clear on what it looks like and how we got it.

Allowing Space for the Unknown

Part of my suggestion for us is that we should maybe step back a little and allow space for things we simply do not know. Knowledge of the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon does not depend on scholarly discussions one way or the other, but on revelation from God.

However, this observation doesn’t mean—and of course, that’s the main point here—that we should automatically dismiss scholarly discussions about the various scriptural books in our canon. The Lord reminded Oliver Cowdery that revelation comes in both the mind and in the heart.

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ belief in revelation comes with both the ability to accept what God has revealed to us, while also recognizing that He trusts us to learn through observation and scholarship.

Whether the specific claims and various reconstructions about the sources and composition of various books in the Bible are tenable is a question that scholars and students of scripture should examine. Although there is broad consensus, consensus can be wrong, and even broad consensus is not a monolith. This means it’s vital for Latter-day Saints to work through our scriptures.

Scholarly constructions of these matters can impact discussions about historicity, but they cannot be used to either confirm or deny the historicity of the Book of Mormon, as we simply do not have sufficient data. However, when used judiciously, they can enhance our understanding of both the Book of Mormon and the Bible.

It is vital that Latter-day Saints read the Bible and the Book of Mormon together, so the two books can work together in their divine mission to bring people to Jesus Christ.

Thank you very much.

TOPICS

- Book of Mormon

- Law of Moses

- Pentateuch

This continuity creates some interesting questions about how the law looked for the Nephites, particularly given the traditional view that Moses authored all the texts in the Pentateuch, or Genesis through Deuteronomy.

Since the 19th century, however, scholarly consensus has challenged Mosaic authorship, suggesting he likely did not write these books. Latter-day Saints maintain a nuanced view of scripture, often holding traditional views on authorship based on tradition and evidence that ties Moses closely to the authority of the law rather than specific authorship. Thus, while Moses is linked with the law, he is seen more as the authoritative figure than the direct writer of the law.

In the Book of Mormon, Nephi illustrates the importance of the law by emphasizing the need to retrieve the brass plates, believing his people needed them to keep God’s commandments. In 1 Nephi 4, he explains the necessity of going back for the plates so they could have the law. However, because we don’t have the brass plates today, we’re left with only a limited view of what “the law” meant for the Nephites, as described in the Book of Mormon.

One key textual clue appears in 1 Nephi 5, where Lehi discovers that the brass plates contain the five books of Moses, an account of the creation, and Adam and Eve’s story—corresponding to the first few chapters of Genesis. However, given the entire law of Moses spans 187 chapters in the current Bible, this brief summary provides limited insight into what constituted the Nephites’ understanding and practice of the law. This is a recurring challenge in Book of Mormon studies, as we seek to piece together what the Nephites’ religious practices might have looked like based on limited textual details.

In general, as we’ve seen in some of our previous presentations, I often like to discuss with my students and quote the famous Harvard critic Thomas Lamden, who once said—not about the Book of Mormon but in other contexts—“We’re working with no data, but we may conclude…” In some ways, Book of Mormon scholars face a similar challenge. We’re not working with no data, but with a fairly limited data set, and so this process involves carefully analyzing what we can and can’t say based on available information.

This notion of the “five books of Moses” is particularly reflective of these challenges. We don’t have access to the brass plates, so it’s easy to assume these five books refer to Genesis through Deuteronomy. However, the Book of Mormon doesn’t explicitly specify this, and we need to approach this topic with a thoughtful lens.

Biblical scholarship over the past century has identified sources and edits within scripture, especially within what we call the Pentateuch. This work is often guided by the Documentary Hypothesis, famously put forward by the German scholar Julius Wellhausen. According to this hypothesis, there are four specific strands or sources in the composition of the Pentateuch: the Yahwist (J), characterized by the use of the Divine name Yahweh or Jehovah; the Elohist (E), a northern source using the name Elohim for God; the Deuteronomist (D), characterized by language and style similar to Deuteronomy; and the Priestly source (P). Each of these has a unique style and theological emphasis, reflecting the complex process of scriptural composition and transmission.

Which Wellhausen thought was the “most Jewish” of all the sources—and please note, for Wellhausen, “Jewish” was not intended as a compliment. He viewed it as a degeneration of “true” religion, reflecting certain sentiments prevalent in Germany at the time.

As with any scholarly stance, there is discussion and disagreement, and this is not universally accepted as the definitive account. Still, the idea that the Pentateuch, or law of Moses, is the product of various sources is broadly accepted within scholarship, even among those who might push against the details of the schema.

This can sometimes be seen as a difficulty for the Book of Mormon, given that some sources and the final form of these texts are thought to date after the Book of Mormon’s beginning in 597 BC, in the first year of Zedekiah, king of Judah. According to prevailing scholarly views, parts of the final text date after the Babylonian exile, around 538 BC. This timeline could appear to conflict with some of the Book of Mormon’s historical claims.

However, for the balance of our time together, I want to suggest that this is not a necessary conflict, even if one accepts the Documentary Hypothesis as articulated by Wellhausen. This schema for understanding the Books of Moses has minimal bearing on the Book of Mormon because the Book of Mormon emphasizes Mosaic authority rather than Mosaic authorship.

Daniel Belnap, my friend and colleague, observes that readers often treat scripture as a monolithic text. However, it’s crucial to recognize that all scripture goes through processes of editing, or redaction. Belnap notes, “Like the Book of Mormon, the Bible in its current form is best understood to consist of original authorial writings, as well as redacted texts, later edited or commented on by subsequent editors.”

For example, we know that the Book of Mormon is a compilation of sources gathered over a long period, compiled and edited by an inspired editor. We should not be surprised, then, to see a similar editorial process in the biblical text, and indeed, we should expect it. Since we do not know precisely what was on the brass plates, nor do we know the exact timeline for when the Bible reached its current form, the exact arrangement of the “law of Moses” material in the Book of Mormon remains open to interpretation.

We don’t know what it looked like on the brass plates. We know it had the story of Adam and Eve and the creation. We know it could be divided into five divisions; we know that explicitly from the text. But we don’t know the specifics or the process. I’m actually working on a project where I’m examining and discussing everything we can say about where we find laws. And by the way, we do find examples of all four strands, or sources, traditionally associated with the Pentateuch. I’ve found at least some examples of all four strands.

But again, thinking through what the Bible says about authorship—the Bible never claims Mosaic authorship for the law of Moses. In fact, it’s always written in the third person: “And God said to Moses,” and so forth. It’s a story about Moses, about Moses receiving the law, and about Moses presenting revelation. It is not presented as a story of Moses saying, “I am doing this.”

A special example here is Moses 1, in restoration scripture. This introductory preface to the JST of Genesis begins with “the words of God which he spake unto Moses at a time when Moses was caught up to an exceedingly high mountain, and he saw God face to face and talked with him, and the glory of God was upon Moses; therefore, Moses could endure his presence.” Note that this is in the third person; it’s about Moses, not written by Moses.

The Pentateuch as we have it presents traditions about Moses that have then been redacted and compiled. This idea is actually reflected in the Book of Mormon as it works through these concepts.

One thing important to remember as we read is our tendency to level things out when there’s actually a large chronological gap. We date Moses to roughly 1200 BC, give or take—he’s hard to date precisely. The Book of Mormon starts in 597 BC, the first year of King Zedekiah of Judah, which means there’s about a 600-year gap between the person of Moses and the start of the Book of Mormon. So Nephi likely didn’t know much more about Moses as a person than we do today, given that long historical gap.

There’s an intriguing verse in 1 Nephi 19 that I want us to consider. You’ve likely heard this many times: “And I did read many things which were written in the books of Moses, that I might more fully persuade them to believe in the Lord their Redeemer; I did read unto them that which was written by the prophet Isaiah, for I did liken all scriptures unto us, that it might be for our profit and learning.” Notice the distinction Nephi seems to be making here.

I did read the things which were written in the books of Moses, but I did read that which was written by the prophet Isaiah.” Nephi seems to indicate authorship here for Isaiah in ways that he doesn’t for Moses, suggesting that, in Nephi’s time, he is aware of a compositional project that goes into what he is calling the books of Moses. Rather than simply assuming direct authorship, Nephi might be acknowledging the process by which these texts were assembled.

As we think through titles, it’s worth noting that sometimes a scriptural book will be named after its author, like First Nephi, but other times, like Samuel or Alma, it’s named after the main character or its association with that figure. Nephi’s identification of the law as the books of Moses does not automatically imply he believes it was all written by Moses. In fact, this language in First Nephi 19 suggests that Nephi might be aware of some of the compositional and compilation notions that contributed to the text.

None of this, however, is to suggest that Nephi, or Latter-day Saints generally, would view the Pentateuch or the law as anything other than deriving legitimately from God and Moses.

There is no sense of that anywhere in the Book of Mormon. Nephi is reading to them from the law—from the books of Moses—in order to persuade them to believe in Jesus, and we see this happening in a number of places across the Book of Mormon. Some of that, I think, relates to Elder Neal A. Maxwell’s cogent observation, where he notes, ‘Have not all the prophets prophesied more or less of these things?’ Sometimes it’s more, sometimes it’s less, but this idea of legitimate authority remains strong.

The Book of Mormon stands firm on the notion that the law came from God through Moses at Mount Sinai. However, it is less clear about its precise form and how it was compiled. My suggestion is that we should perhaps step back and make room for things we just don’t know. Knowledge of the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon is not dependent on scholarly discussions but rather on revelation from God.

This does not mean, however, that we should disregard scholarly discussions of the various scriptural books in our canon. The Lord reminded the Brother of Jared that revelation comes to the mind and the heart. Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints believe in revelation and embrace both what God has revealed to us and what we can learn through observation and scholarship.

Whether specific claims and various reconstructions about the sources and composition of the Bible are tenable is a question for scholars and students of scripture to explore. While there may be a broad consensus on some issues, consensus is not infallible, nor is it a monolith. Thus, it is vital for Latter-day Saints to work thoughtfully through our scriptures. Scholarly constructions can offer valuable insights and enhance our understanding of both the Book of Mormon and the Bible. It is essential that we read the Bible and the Book of Mormon together, allowing the two books to fulfill their divine mission to bring people to Jesus Christ.

Thank you very much.