Michaelbrent Collings argues that horror is fundamentally aligned with the gospel because both rely on a foundational moral framework, agency, and faith. He illustrates that horror stories often depict a clear moral order disrupted by chaos or evil, mirroring the gospel’s teachings about good versus evil, and views the gospel itself as the ultimate redemptive “horror story,” where humanity triumphs over evil through faith and divine guidance.

Introduction

Scott Gordon: Our next speaker is Michael Brent Collings. He is an internationally best-selling novelist, and produced screenwriter, speaker, and writing teacher. He’s best known for horror, and he’s been voted in the top 20 all-time greatest horror writers. He’s written best-seller thrillers, mysteries, sci-fi, and fantasy titles. There’s a lot more we could read on his bio, but I want to give as much time as I can to him. So, with that, I’m turning the time over to Michael Brent Collings.

Michael: All right, thank you so much for being here, first of all. This has been such a delightful conference. I’ve never been before, and I’ve just enjoyed so many of the talks. Brother Shannon, Brother Westra, Sister Carruth, Sister Thatcher, if she’s still here. I’m so grateful she closed with in the name of Jesus Christ amen. I’m not an academic, in case you couldn’t tell. I dressed up for an author—I put pants on! But I’m going to pursue this much like a church talk.

And, we will go ahead and dive right in. This is “Finding Light in the Darkness: The Necessity of Horror in the Gospel.” Anyone worried about your immortal soul, I hope you come out fairly unscathed.

So here’s the presentation overview: I’m going to talk a little about me—it’s the braggy part. It’s not intended as bragging, it’s just so I can present my credentials so that I have a measure of, you know, believability. And then, we’re gonna talk about some definitions. I’m a word person. I’m obsessed with definitions, which is why some of the talks I named were my favorites, they talked about communication methods and where we can go wrong.

So we’re gonna be talking about what people think of horror, which is mostly not what horror is, if you talk to professionals, and how that misconstruction occurs. And then, we’re gonna talk about what horror actually is and its intersection with the gospel. And yes, there is one. And just so you all know, I started writing horror a long time ago, and I’ll talk more about it, but I’m actually a good member of the Church. And I very often go to horror movies with my stake president. I have been in the Deseret News numerous times. So, again, like, this is something that some people have a really odd idea of, and I’ll explain a little of it.

And I am gonna talk about the intersection of horror and how it works with the gospel, and then I’m gonna talk about what most problems occur—which is the difference between Heavenly Father’s appropriate horror and Satan’s horror. And then we’re gonna have a little spoiler: God does win in the end, so no matter what I say, wrong or right, it can’t hurt that.

Quickly about me: they talked about that, I’m the creator of BestsellerLife.com, which is where I teach people to write, publish, and market their books. And that’s important because I have thought about storytelling a lot, that’s how I can teach it. And I think about words a lot. I am an internationally best-selling indie author, I have been top 100 in numerous countries all over the world. I am good enough to actually be published—in fact I’m gonna have a nationally published book with the Church’s fiction arm next year—but usually that involves taking a pay cut for me. And because my priority is putting food on the table for my family, I just write books and market them myself, here are a couple of them.

Quickly about me: they talked about that, I’m the creator of BestsellerLife.com, which is where I teach people to write, publish, and market their books. And that’s important because I have thought about storytelling a lot, that’s how I can teach it. And I think about words a lot. I am an internationally best-selling indie author, I have been top 100 in numerous countries all over the world. I am good enough to actually be published—in fact I’m gonna have a nationally published book with the Church’s fiction arm next year—but usually that involves taking a pay cut for me. And because my priority is putting food on the table for my family, I just write books and market them myself, here are a couple of them.

Particularly pertinent to this presentation,

Particularly pertinent to this presentation,  I am best known for horror, I’m a produced horror screenwriter. Multiple Bram Stoker Award finalist (that’s kind of like the Academy Awards for screenwriting) multiple Dragon Award finalist (the people’s choice award for writing), and I was nominated for horror in that. And again, voted one of the top 100—I do wanna clarify, I don’t necessarily agree with that. I’m willing to brag about it, but I’m not saying it’s true.

I am best known for horror, I’m a produced horror screenwriter. Multiple Bram Stoker Award finalist (that’s kind of like the Academy Awards for screenwriting) multiple Dragon Award finalist (the people’s choice award for writing), and I was nominated for horror in that. And again, voted one of the top 100—I do wanna clarify, I don’t necessarily agree with that. I’m willing to brag about it, but I’m not saying it’s true.

And I grew up in a “horror house.” This is what most people think of as a horror house,

but this is not what they usually look like. I grew up learning about horror from my father. Who wrote horror poetry; in between talks in Church; sitting on the podium. Because my father was the ward organist in every ward we lived in for 30 years. And my father is deaf. And so in between playing music he could not hear, he sat and wrote uplifting poetry, which, for him, was horror poetry. He was also the world expert on Stephen King for twenty years. And the reason that so many kids today, if they show up with a Stephen King book, can talk to it about their teacher instead of the school psychiatrist. Because when I was a kid, going in with a Stephen King book would get you a talk with the principal, and maybe a failing grade. So my father bumped into a Stephen King book one year, and said ‘This is literature.’ And as the head of the creative writing department and one of the English department professors at a major university, he was in a position to start talking about that, and he wrote a dozen booklink scholarly treatises on Stephen King and dozens of other articles and books on other popular writers, talking about them as literature.

So, when I say I grew up in a horror house, yeah, I grew up in a house with screaming constantly in the next room. But it was just ‘cause my dad was watching a Stephen King movie, which he would then write a book about. So I went to bed with screaming and typing, and that’s how I grew up. I didn’t have much of a chance as far as what I was going to be doing as an adult. I did try and avoid it, I didn’t want to be a writer. I tried to have a grown up job as a lawyer, and unfortunately that didn’t work out, and here we are.

Now despite all this, or maybe because of it, I am not just a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—I am a believer. And there is a difference. I have served in callings of authority and in callings not in authority, which I vastly prefer. My favorite is Second Counselor in anything, because then I can give my opinions and not be in trouble for the problems. I have served anywhere and everywhere and love serving in the Church. My wife and I have a standing order with the bishop and stake president at all times: you don’t need to interview us, just tell us what we’re doing. Because I believe in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and I believe in the gospel.

Now despite all this, or maybe because of it, I am not just a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—I am a believer. And there is a difference. I have served in callings of authority and in callings not in authority, which I vastly prefer. My favorite is Second Counselor in anything, because then I can give my opinions and not be in trouble for the problems. I have served anywhere and everywhere and love serving in the Church. My wife and I have a standing order with the bishop and stake president at all times: you don’t need to interview us, just tell us what we’re doing. Because I believe in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and I believe in the gospel.

Now despite all this, I do want to give you a warning: I have all this cool background; again, not an academic. So, here’s the other presenters, and this is me.

Now despite all this, I do want to give you a warning: I have all this cool background; again, not an academic. So, here’s the other presenters, and this is me.  That said, I am pursuing this as a church talk, and we believe that the Spirit teaches, so at the end of this if you haven’t had a good time, it’s not because I did a bad job, it’s ‘cause you’re a lousy student.

That said, I am pursuing this as a church talk, and we believe that the Spirit teaches, so at the end of this if you haven’t had a good time, it’s not because I did a bad job, it’s ‘cause you’re a lousy student.

Now, what we think of horror? Now, when I’m talking about ‘we,’ I’m talking about mostly people who don’t like horror, including non-horror-loving LDS community. I want to make it clear, I have nothing against people who dislike horror—not a thing. Not everything is for everyone. But I do think it’s important to evaluate it properly, and that’s what I’m talking about largely here. Different genres do not salvation make; that’s one of the key points of this talk.

Now, what we think of horror? Now, when I’m talking about ‘we,’ I’m talking about mostly people who don’t like horror, including non-horror-loving LDS community. I want to make it clear, I have nothing against people who dislike horror—not a thing. Not everything is for everyone. But I do think it’s important to evaluate it properly, and that’s what I’m talking about largely here. Different genres do not salvation make; that’s one of the key points of this talk.

Here’s what people in that group think though, they think about horror as bloody— and not just bloody, but violent, and not just violent, but prurient, it’s chock-full of nudity. And not just that, but it’s just kind of icky, or in gospel parlance, it’s just plain wicked. And I have definitely had interactions, mostly kind, with people who have had concern for me because of my choice of writing. And I will have a caveat that I’m not sure it is a choice, and certainly, it is helping put my son on his mission.

Here’s what people in that group think though, they think about horror as bloody— and not just bloody, but violent, and not just violent, but prurient, it’s chock-full of nudity. And not just that, but it’s just kind of icky, or in gospel parlance, it’s just plain wicked. And I have definitely had interactions, mostly kind, with people who have had concern for me because of my choice of writing. And I will have a caveat that I’m not sure it is a choice, and certainly, it is helping put my son on his mission.

So, these ideas are not just incomplete, but they’re wildly inaccurate and they are actively harmful. And I will come back to this, trust me, but I’m gonna just leave it sitting there for a bit. I’m gonna whip through these slides, ‘cause I’ve got like 120 of them to get through, so take your pictures fast, folks!

So, these ideas are not just incomplete, but they’re wildly inaccurate and they are actively harmful. And I will come back to this, trust me, but I’m gonna just leave it sitting there for a bit. I’m gonna whip through these slides, ‘cause I’ve got like 120 of them to get through, so take your pictures fast, folks!

Alright. First, how did we have this misconception? I wanna talk about this, and a lot of my talk is gonna be definitions, because I believe if you define things properly, 99% of the time, the solution presents itself along the defining. Most of our issues that we have come from misconception rather than misunderstanding—that is, we don’t have the complete concept, we have not been communicated properly with.

So as we define things properly–I loved all the talks about mistranslations and the Journal of Discourses. I was sitting in the back with my wife taking notes, going, ‘See, I told you!’—even though she knows all this stuff, but she’s who I say that to, and she’s very nice, she lets me think I’m smart.

How did this misconception of horror come to be for the vast- the status quo of so many people? And it’s like this: we’re going to have to talk about a history of communication first. It’ll be really quick, and anybody out there who’s a professor of communication, don’t worry—I won’t impinge on your area. It’s going to be very general, and you’re better at it than I am.

How did this misconception of horror come to be for the vast- the status quo of so many people? And it’s like this: we’re going to have to talk about a history of communication first. It’ll be really quick, and anybody out there who’s a professor of communication, don’t worry—I won’t impinge on your area. It’s going to be very general, and you’re better at it than I am.

According to science, here’s how communication works.

It started out as non-verbal, and I love non-verbal communication—it’s so much clearer. The greatest inhibitor of communication ever invented was language. And here’s why: because in cave people times, if you came up to me and I liked you, you would know it, because if you were a female, I’d bonk you on the head and take you into the cave and try and make a family. And if you were a male, I’d offer you a piece of my T-rex bone, and we’d be friends. It was very clear. And if I didn’t like you, I would just try and murder you. And either way, we were on very equal footing, and everybody knew where we stood.

It started out as non-verbal, and I love non-verbal communication—it’s so much clearer. The greatest inhibitor of communication ever invented was language. And here’s why: because in cave people times, if you came up to me and I liked you, you would know it, because if you were a female, I’d bonk you on the head and take you into the cave and try and make a family. And if you were a male, I’d offer you a piece of my T-rex bone, and we’d be friends. It was very clear. And if I didn’t like you, I would just try and murder you. And either way, we were on very equal footing, and everybody knew where we stood.

I fell in love with my wife very fast on our first date. She fell in love with me—not as much, but she liked me a lot. But I wasn’t sure until she actually held my hand, and I was like, “Maybe I have a chance.” Non-verbal stuff is great. Somebody’s been there.

But then comes the verbal, and we end up with what we’re doing today. Now, according to the gospel, it’s a little bit different.

But then comes the verbal, and we end up with what we’re doing today. Now, according to the gospel, it’s a little bit different.

According to the gospel, communication has existed since God organized all creation.

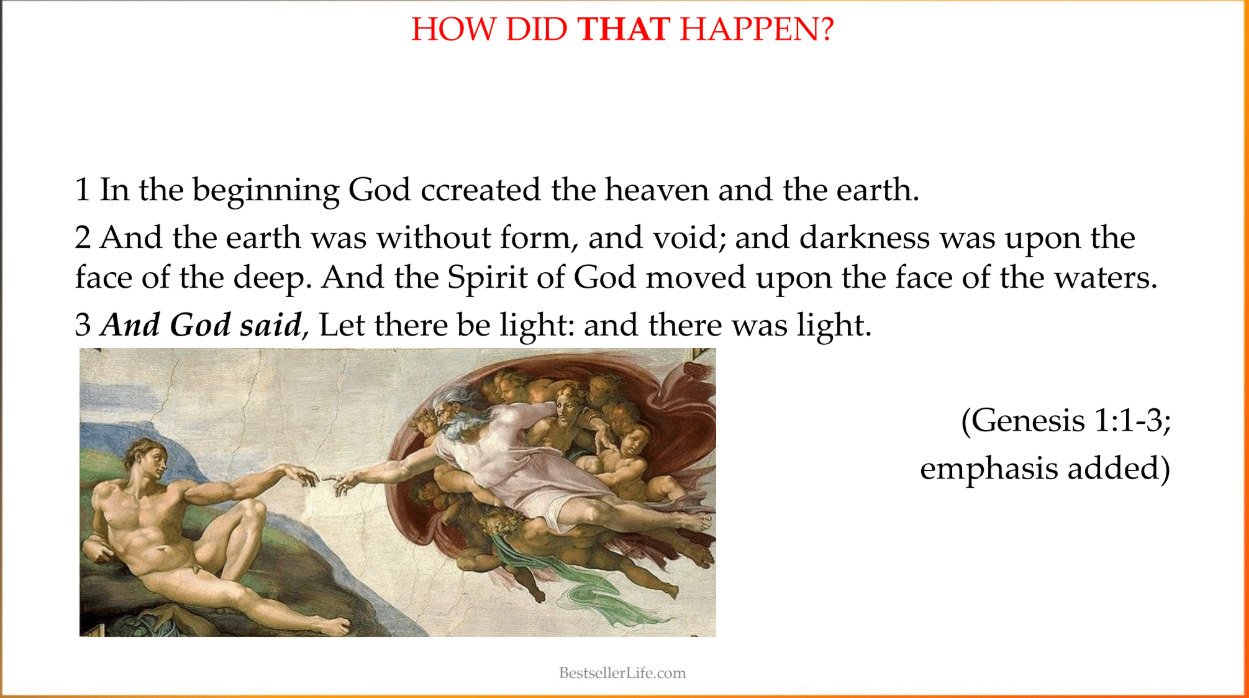

In Genesis, “In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth.” And as soon as He did that, He said something. Part of the creative process was the Lord’s communication, and I think that’s so telling and so interesting. That the writers of the scriptures didn’t start out with, “I’m going to explain how Heavenly Father works with atoms.” No, they said, “This is the important godly communication that our Lord said so that all creation would have a template to follow.” And that’s what communication is in the gospel—it’s designed to bring us to God. It is designed to help us return to Him.

In Genesis, “In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth.” And as soon as He did that, He said something. Part of the creative process was the Lord’s communication, and I think that’s so telling and so interesting. That the writers of the scriptures didn’t start out with, “I’m going to explain how Heavenly Father works with atoms.” No, they said, “This is the important godly communication that our Lord said so that all creation would have a template to follow.” And that’s what communication is in the gospel—it’s designed to bring us to God. It is designed to help us return to Him.

We have writing that dates back to 3200 BC—very old writings. Interestingly, the oldest writing in the BYU archive, which I’ve been to because they have my books down there, is a beer recipe, which I think is fantastic. The oldest thing they’ve got in the archive is a beer recipe. So, we have lots of really old writing, but the first surviving work of great literature, The Epic of Gilgamesh, appears a thousand years later. That makes sense because it takes a while to go from “Number of cows I have” to “See Spot Run,” let alone this amazing epic adventure, The Epic of Gilgamesh, which is wonderful and is a horror story for anyone who’s read it.

We have writing that dates back to 3200 BC—very old writings. Interestingly, the oldest writing in the BYU archive, which I’ve been to because they have my books down there, is a beer recipe, which I think is fantastic. The oldest thing they’ve got in the archive is a beer recipe. So, we have lots of really old writing, but the first surviving work of great literature, The Epic of Gilgamesh, appears a thousand years later. That makes sense because it takes a while to go from “Number of cows I have” to “See Spot Run,” let alone this amazing epic adventure, The Epic of Gilgamesh, which is wonderful and is a horror story for anyone who’s read it.

It makes perfect sense—it takes a while to develop. Also, it has to be remembered that writing at first was a thing of kings and gods. If you were an average person, you didn’t write. You were busy surviving. If you were a king, well, you often didn’t write either because you had people reading it to you. But you had record-keeping, you had important documents, and you had stories. I love parts in the scriptures where the kings say, “Tell me a story,” to their scholars, essentially. It’s wonderful—a story within a story.

But then, over time, we had this occur: the invention of the printing press, which led to the word getting out there.

Soon after that, we had books suddenly available to people—still largely rich people, but they were appearing elsewhere. They were appearing in normal houses, if you were very lucky.

Soon after that, we had books suddenly available to people—still largely rich people, but they were appearing elsewhere. They were appearing in normal houses, if you were very lucky.  Then it was followed by this innovation: “Well, if we’re going to make it, let’s sell it.” Which was followed by this tragedy.

Then it was followed by this innovation: “Well, if we’re going to make it, let’s sell it.” Which was followed by this tragedy.

For those of you who can’t see the tragedy—that’s the person selling the books who has no idea what any of these books are about because they’re a college person who needed a job. They’ve never liked to read, but Barnes & Noble was hiring, so they took it. “What do you want?” I’m sure we’ve all had interactions with that particular employee.

The reason I say that this was a continuation of the communication cycle is that, early on, if you had a book, you probably knew it by heart. It was very possibly your only book, and you were likely rewriting or copying it word for word.

You know, there was this transitional state between oral and written communication as the primary mode of information passing. Before, we had one of the speakers talking about people memorizing all these things. Now, we have people writing them down, and they’re still memorizing them because they’re spending their life rewriting a single book or rereading, over and over, a single book.

But then, with the printing press, the written word is disseminated, and suddenly we have lots of them. People are going to the bookstore, and the bookstore is great, but nobody goes into a bookstore originally and says, “I’d like a horror novel.” What they say is, “I’d like something, perhaps with ghosts, or just a bit scary.” Why? Well, we have a Boy Scout campout back in the olden times.

The bookstore owner says, “Well, I know exactly where it is. If you go to the third shelf over there, second shelf down, third book from the left, you’ll find a new one. It’s actually so new, we’re calling it a novel, and it’s by Mary Shelley. It’s about a monster. You’ll love it.”

Okay, but then, as books become more available and cheaper to make, they become easier to come by. This bookstore owner becomes more successful and has to hire help. Nobody knows the business like the business owner, and the bookstore owner gets tired of young varlet employees asking, “Somebody just said they want a scary book. Where do I find that?”

“Ah, varlet! Third shelf. There’ll be a book by this person named Mary Shelley. It hath done quite well.”

He gets tired of this because the reason he hired the employee in the first place was so he wouldn’t have to do this.  And so, genre was born. It’s a sales technique. When people ask me what defines horror, it’s very simple. Pragmatically, it is whatever is on the horror shelf in your local bookstore or on the horror virtual shelf on Amazon. Okay? That’s really all it is. It’s just an easy way to catalog and find things so that the owner of the bookshop doesn’t have to oversee every sales transaction personally. That was it.

And so, genre was born. It’s a sales technique. When people ask me what defines horror, it’s very simple. Pragmatically, it is whatever is on the horror shelf in your local bookstore or on the horror virtual shelf on Amazon. Okay? That’s really all it is. It’s just an easy way to catalog and find things so that the owner of the bookshop doesn’t have to oversee every sales transaction personally. That was it.

So, there’s this third developmental line of communication. We’ve talked about, according to science, according to the gospel, and then we’ve got this weird mixture with the philosophies of men we call “the world.” In that, we have non-verbal leading to verbal, and then we end up with this commercial stuff.

Okay, and commercial communication has a different priority. Communication for God is to make the gospel happen—and we’re going to talk about what the gospel is. Communication between people is largely to transmit ideas.

Communication commercially is about getting money. That’s it. It’s about what I need to say to you to get the money from you and put it with me. If I could figure out a way to do that and get you to just leave, that would be great. But that doesn’t usually work, so I’m going to have to tell you something and give you something. But the communication is about that.

Communication commercially is about getting money. That’s it. It’s about what I need to say to you to get the money from you and put it with me. If I could figure out a way to do that and get you to just leave, that would be great. But that doesn’t usually work, so I’m going to have to tell you something and give you something. But the communication is about that.

Okay, so commercial necessity is how we get this. I didn’t want to have copyright issues, so—insert typical movie poster featuring a busty, half-naked teen running from an axe murderer holding a severed head. Okay? And we’ve all seen those movie posters as we, as good members of the Church, walk into the movies, of course, to see, you know, Village of the Shiny Happy People Where Everybody Follows the Lord: Part Three. We walk past this movie poster—this horrific movie poster.  Or maybe, if we’re really unlucky, we end up going to the bookstore and seeing this stuff by some quack of an author named Michael Brent Collings. (I say that self-effacingly as a joke.)

Or maybe, if we’re really unlucky, we end up going to the bookstore and seeing this stuff by some quack of an author named Michael Brent Collings. (I say that self-effacingly as a joke.)

But none of these books are about the thing on their cover, particularly. Some of it mirrors it, but not a single one of these has a scene in any of them that actually has this occurring.

When I was talking to Shadow Mountain recently, they were very nice and invited me to participate in the cover selection. They asked, “Do you have any problems with it?” I said, “I don’t care if there are two leprechauns kissing—which doesn’t happen in the book—so long as it sells books, because that’s the purpose.” They said, “You’re like our dream author.”

Okay, because we’re just trying to get books to sell. And so, the problem is most people see commerce as ruining everything. There are people out there who think it ruins even a fair talk because you end up with a commercial in the middle. And we’re trying to communicate something that will sell.

Most people’s views of horror—especially those who don’t read or view it—are not molded by reality but by advertising, by the movie poster, which is designed to shock, to get you to stop while you’re on your way to the shiny, happy movie. They are molded by the book covers, which are, by and large, less scary than the movie posters, but they’re still designed to get you to stop, to get you to open them, and to convey a tone. Really, that’s it.

Most people’s views of horror—especially those who don’t read or view it—are not molded by reality but by advertising, by the movie poster, which is designed to shock, to get you to stop while you’re on your way to the shiny, happy movie. They are molded by the book covers, which are, by and large, less scary than the movie posters, but they’re still designed to get you to stop, to get you to open them, and to convey a tone. Really, that’s it.

Most people see that. They haven’t read any of the books, and they think, “It’s horror.”

Now, we’ve talked about what people think horror is but actually isn’t.

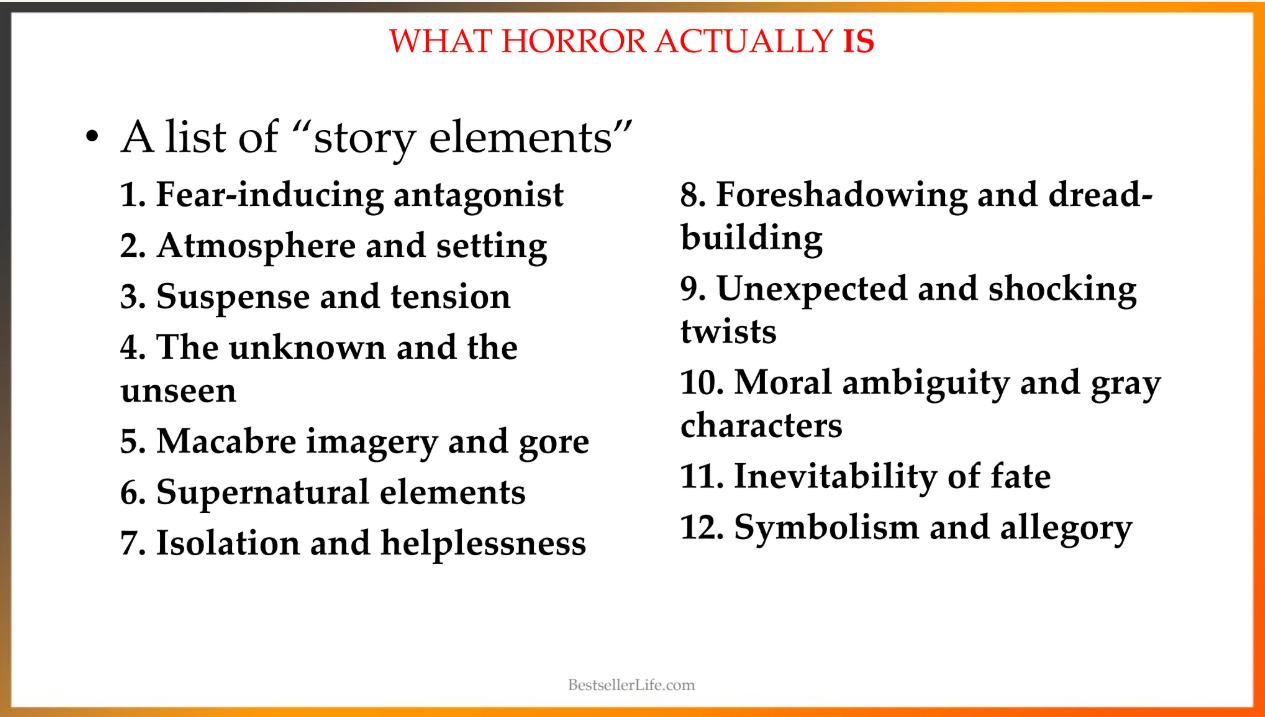

What horror actually is, is a list of story elements. So, when you talk about horror to a professional, they know you’re not talking about genre, per se, you’re talking about these: fear-inducing antagonists, atmosphere and setting, suspense, the unknown, macabre imagery, supernatural elements, isolation, foreshadowing, unexpected twists, moral ambiguity and gray characters, inevitability of fate, symbolism, and allegory. Every single one of these is found in other acceptable genres.

What horror actually is, is a list of story elements. So, when you talk about horror to a professional, they know you’re not talking about genre, per se, you’re talking about these: fear-inducing antagonists, atmosphere and setting, suspense, the unknown, macabre imagery, supernatural elements, isolation, foreshadowing, unexpected twists, moral ambiguity and gray characters, inevitability of fate, symbolism, and allegory. Every single one of these is found in other acceptable genres.

It’s one of my favorite things when somebody says, “I don’t like horror,” and I can tell it’s someone who’s never read or viewed any. Why? Well, because “it has violence.” I go, “Oh, so you don’t like war documentaries?” “Well, those are fine, but that’s good violence, I guess.” “Well, it’s got this prurient thing.” So, romance is out because we know that romances in the world are, by and large, highly prurient, even if they don’t show it on the stage, on the screen, or on the page. “Oh, well, those are okay.” And when you drill down, I usually get to: “I saw a horror trailer for a movie that I really didn’t like.” And that’s fine too.

But there are actually only three story elements that fundamentally define horror as a genre. We’ll talk about them shortly.

First, I’m going to talk about—yeah, I’m a writer; I do suspense, right?—we’re going to talk about how horror and the gospel interact first. And to do that, we’re going to talk about what the gospel is.

Okay, this is the gospel: the Gospel of Jesus Christ is our Heavenly Father’s plan for the happiness and salvation of His children. I put a little asterisk there to remind me—as an author—so, like, if I was good at other stuff, I’d do that. I’d have a real job. Um, so, as a generally incompetent wordsmith, to emphasize this: the gospel is not the Ten Commandments. The gospel is not the scriptures. It’s not the prophet. It’s not the priesthood. The gospel is Heavenly Father getting us to come home however He can do it.

Okay, this is the gospel: the Gospel of Jesus Christ is our Heavenly Father’s plan for the happiness and salvation of His children. I put a little asterisk there to remind me—as an author—so, like, if I was good at other stuff, I’d do that. I’d have a real job. Um, so, as a generally incompetent wordsmith, to emphasize this: the gospel is not the Ten Commandments. The gospel is not the scriptures. It’s not the prophet. It’s not the priesthood. The gospel is Heavenly Father getting us to come home however He can do it.

We had the last speaker talk about that—short of violating our agency—whatever He needs to do. And that’s why I tell my kids, like, “If the prophet got up and said, ‘Starting tomorrow, we all have to get drunk once a day,’” listen, I hate the smell of wine. It gives me migraines, so, this isn’t somebody who’s always drunk a lot and is excited– “I would not like that, but I’d start drinking, because Heavenly Father apparently decided that the world had changed, or I had changed, or something had changed, such that wine will now help us move forward.” And that’s not the gospel changing, because the gospel isn’t God’s methods day-to-day. The gospel is God’s hope and goal. This is my work and my glory: to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man. That’s it.

Now, that said, there are some fundamental characteristics we see as part of the restored gospel. I’ll talk about these chronologically because everything’s a story to me. That’s why I told you about myself, so you’d be like, “Oh, he’s a story guy; now it makes sense.” See? We came back to it.

The first one is a world with a foundational moral framework.

I love this scripture: There is a law irrevocably decreed in heaven before the foundations of this world, upon which all blessings are predicated. And when we obtain any blessing from God, it is by obedience to that law upon which it (the blessing) is predicated. I added some emphasis just to point out this is something Heavenly Father sets up as part of the gospel. It’s built into the system from the beginning.

I love this scripture: There is a law irrevocably decreed in heaven before the foundations of this world, upon which all blessings are predicated. And when we obtain any blessing from God, it is by obedience to that law upon which it (the blessing) is predicated. I added some emphasis just to point out this is something Heavenly Father sets up as part of the gospel. It’s built into the system from the beginning.

I will admit part of the reason I love this scripture is because it makes me look hilariously dumb. When I first found this, I was like, “There’s, like, one rule, and if I get it right, I get all the blessings,” because I read it as, “There is this ultra thing that if I do it…” You know, there is a law. “Which one? I do tithing. I hope it’s that law, and I’ll just get everything.”

And that doesn’t make me a bad kid. It makes me misunderstand things, and I’m glad to be reminded of that because, as I grow and look back at all my mistakes, hopefully that’s a measure that I’m learning a little bit—not that I had a bad heart or my ideas were evil, but that I learned and I repented. And repentance, by the way, is a fascinating word which has roots that mean “finding new information.” It’s fantastic.

Moving on—side step, sorry—so, we’ve got this foundational moral framework, which leads necessarily to the second characteristic through which the first has value, which is agency:

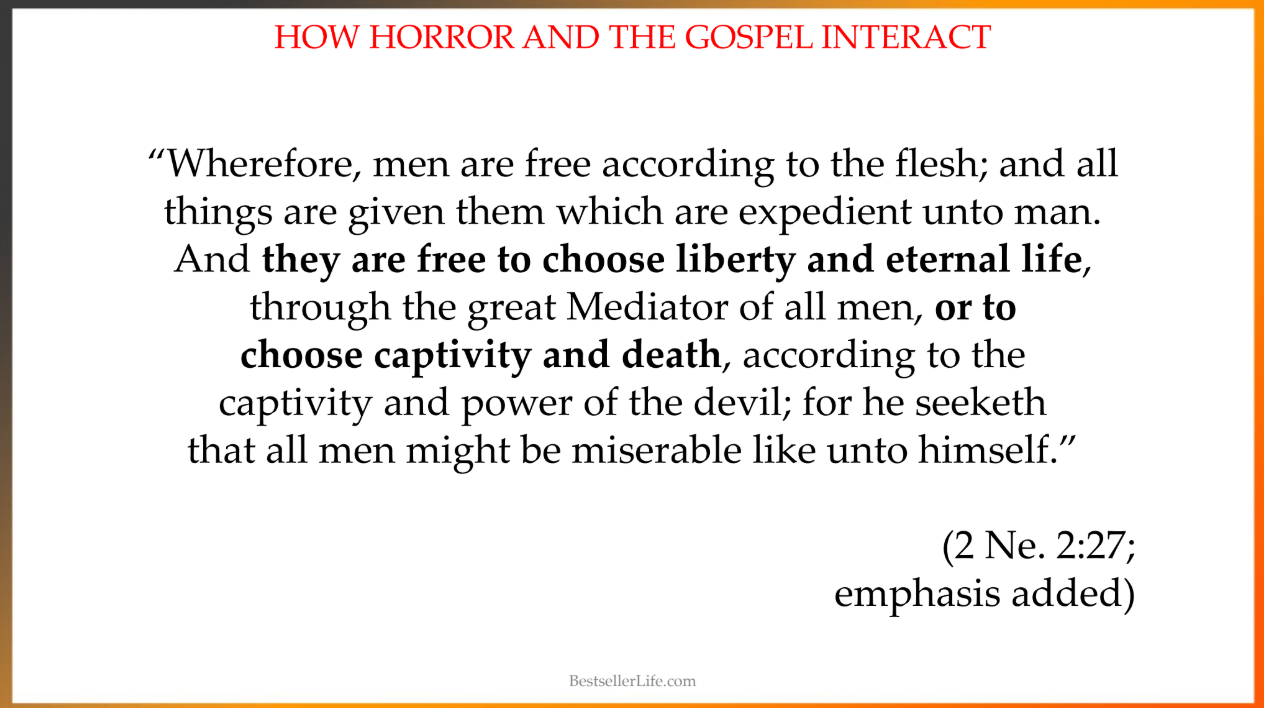

Men are free according to the flesh. They’re free to choose liberty and eternal life, or to choose captivity and death.

Men are free according to the flesh. They’re free to choose liberty and eternal life, or to choose captivity and death.

I love this scripture as well, but there are a couple of others: Genesis, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Corinthians, Helaman, and Moses. At this point, I got tired and just went, “Look at the topical guide; there’s pages of it.”

I love this scripture as well, but there are a couple of others: Genesis, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Corinthians, Helaman, and Moses. At this point, I got tired and just went, “Look at the topical guide; there’s pages of it.”

And the interactions between characteristic one of the restored gospel—our knowledge of the foundational moral element, the framework of the universe—and two, our agency, require the development of the third characteristic, which is faith.

And the interactions between characteristic one of the restored gospel—our knowledge of the foundational moral element, the framework of the universe—and two, our agency, require the development of the third characteristic, which is faith.

Okay: We believe that the first principles and ordinances of the gospel are, first, faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, and so on and so forth.

Okay: We believe that the first principles and ordinances of the gospel are, first, faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, and so on and so forth.

I love this quote by Joseph Smith—although now I’m going to have to look and see if there was any shorthand that was miswritten. Faith—I’m not even kidding—changed my world. I was going, “I’m talking to my wife, going, ‘I have to learn all kinds of shorthand now.’” Faith being the first principle in revealed religion and the foundation of all righteousness.

I love this quote by Joseph Smith—although now I’m going to have to look and see if there was any shorthand that was miswritten. Faith—I’m not even kidding—changed my world. I was going, “I’m talking to my wife, going, ‘I have to learn all kinds of shorthand now.’” Faith being the first principle in revealed religion and the foundation of all righteousness.

Now, I put faith third, even though it’s very clearly first in all of these lists, because it is first as soon as we get to the world that God created for our agency. Have some faith, people.

And with those three things, those are the three characteristics of God’s plan of salvation set up for us. Everything else is kind of window dressing. And, of course, the atonement being the material through which it is all made.

So, the central characteristics: a foundational moral framework with a promised reward, agency, and faith.

Now, we’re going to talk about horror as a genre, which has three essential characteristics: a foundational moral framework, agency, and faith.

“Why write horror?” people ask. And I say, without fail, “Because horror is the genre of hope and the most righteous of all genres when done properly.”

In story terms, this foundational element of morality—a sense that the universe has a right way to be—that’s why it’s so scary, because we know there’s a right way the universe should be, and whatever is happening in this story is wrong. It’s just not the way it should be, and it’s horrifying how wrong it is.

Characters who are presented with a choice—or else there’s no action, which is one of the essential pillars of storytelling—that’s what differentiates storytelling from an instruction manual. That’s why nobody cracks open, “What are you reading, honey?” “I’m super excited to read the instructions for the latest iPad.” Doesn’t happen. Now, you can make a story about whether I did it right or wrong, and maybe my iPad blew up, but that’s about my choices in relation to the instructions. No one ever just reads the instructions for fun. Well, I can’t say no one, but most people don’t, because they’re not a story; they’re a list.

What makes a list of events into a story is the insertion of a choice and, of course, hope for reward and fear of loss. That’s faith. Do we choose to hope and act as we will in a way that will bring success, that will bring a return to the Lord, that will keep me away from the scary axe murderer? Or do we just curl up in a corner and become apostate—or, in horror terms, be the dumb person that runs up the stairs when they should be running out the front door? Or who says, “Let’s hide in the cemetery” or something ridiculous?

Thank you for the laugh, so that a couple people know what I’m talking about. That’s the motivating hope behind all the characters’ choices in these stories, just as it is the motivating hope in everything we do. The Lectures on Faith—I love that whole first lecture. It’s fantastic, because it talks about that.

Now, I would like to tell you a story, ‘cuz I’m a storyteller, and I’m going to tell you a story about a horror writer at church, the scariest book I ever read, and the scariest movie I ever saw.

I go to church every week—well, not every week, ‘cuz I’m getting older, and sometimes my back says, “You’re not leaving the bed today.” But most of the time, I go to church, and I’ll teach a Gospel Doctrine lesson because I very often get called to Gospel Doctrine.

And I knew—this has happened multiple times; I’m not making this up; we’re in the dozens—my wife’s going, “At least.” So, I’ll teach the lesson, and some new person who’s never been in the ward before comes up and says, “That was a really great spiritual lesson. I really enjoyed it.” And I say, “Thank you so much. I really appreciate that you were listening to the Spirit,” because I’ll give credit, as well as save myself from embarrassment. The Spirit was there, and I’m so happy for that.

We talk, and they tell us why they’re new in the ward. “Oh, I’m an aerospace engineer, and I moved in because there’s a lab,” or whatever. And inevitably, they say, “What do you do?”

And I say, “I write books,” or, “I write stories,” because that—my wife told me to say that—scares fewer people. But it never works, because they go, “Oh, like Harry Potter?” That’s almost always what somebody says after I say, “I write stories,” which is interesting in and of itself, and I could fill hours discussing that. But I say, “Sure, kind of. But, like, Hermione gets really mad and sets fire to Harry halfway through the first book, and then Ron has to run from her for the remainder of the series.”

And they’re like, “What?” And I go, “I write scary books.” So, all my wife’s hard work is tossed out the window.

And I do occasionally—very often, I get, “Oh, that’s awesome! I kind of like scary books too,” like we’ve suddenly been transported behind the house, and we’re smoking cigarettes together or something. So, I get that response.

Or I’ll get—and this is where they’re like, “I just said he gave a really good Gospel Doctrine lesson, and it was very spiritual. How do I take that back?” Not really, but there’s a cognitive dissonance moment.

And I have had people say, “Why?” and follow it up a couple of times—more than once—with, “Why would you write stories about someone stabbing you in the heart?” (Which is seriously a verbatim thing, like Harry Potter—it’s just something in our Jungian consciousness because it comes up more than once.)

And my response is always the same: “I have no interest in writing stories about stabbing anyone in the heart. I genuinely don’t. What I want to do is cut your heart out, throw it into a valley, cover it up with a mountain, and then show that, with your determined choices, your hope of reward—and usually through grace, either from God (which appears in horror stories a lot) or through God’s tools of a friend—that’s enough. You are enough to survive. That is why I write those stories.”

The reality is this: the gospel is a horror story.

The reality is this: the gospel is a horror story.

The gospel is the ultimate story of agency, hope, and the possibility of loss, followed by the reality of triumphant exaltation—a world free of evil.

The gospel is the ultimate story of agency, hope, and the possibility of loss, followed by the reality of triumphant exaltation—a world free of evil.

How does this—I’m not finished with my story. So, after I’ve dropped this bomb, I say, “But seriously, I’ll tell you the scariest story I ever read. It’s, you know, it’s an everyman kind of a story. They often are, so we can sort of relate, and it sucks us in that much more. It’s a guy who—there’s kind of a question of whether it’s a conspiracy theory issue or a mistake in identity kind of thing—but the result is he ends up totally in trouble for stuff he never did. He’s betrayed by everyone who loved him, or at least enough people that it doesn’t make a difference. He is tortured explicitly and horrifically, and then nailed to a cross.”

And if there is anyone out there who thinks there is a more horrific event than that, I would invite you to think about your testimony. But it’s not a bad story because it doesn’t end there.

Three days later, that same man becomes something more. Touch me not, for I have not yet ascended to heaven. And then he goes to heaven and joins His Father and is really the first example—we talk about the first fruits, you know—the first person who broke the chains of death.That’s the first person who ever lived the gospel to fruition. That’s a fantastic horror story. Fantastic one.

Similarly, the scariest movie I ever saw—I don’t know if anyone here saw—was the old Joseph Smith movie where he goes to the Sacred Grove to pray and then is crushed by this darkness. I just about wet my pants in Primary. I really did. That stayed in my dreams till this day, I’m going to be honest.

Everyone goes, “And I went to the Grove, and it was so beautiful.” I’m like, “No, no, I don’t go to groves. I also don’t swim where Jaws lives, and I don’t hide in cemeteries. It’s just not stuff that I do, okay?”

And nobody thinks of that and says, “Well, you must be a weirdo ‘cuz the Joseph Smith story scared you.” That was scary.

Now, the problem is, there’s good horror and there’s bad horror.  Of course, there’s such a thing as bad horror. And here’s a tip—there’s a bad version of everything that’s good because that’s how Satan works, okay?

Of course, there’s such a thing as bad horror. And here’s a tip—there’s a bad version of everything that’s good because that’s how Satan works, okay?

Oh, minute and a half till Q&A. I gotta go faster.  This isn’t because horror is evil. It’s because horror is the genre of hope and righteousness, and it is particularly susceptible to Satan’s attentions and attempts to lure people away from it.

This isn’t because horror is evil. It’s because horror is the genre of hope and righteousness, and it is particularly susceptible to Satan’s attentions and attempts to lure people away from it.

Two percent, according to Brother Westra of Twitter, is taken up with mostly negative depictions of the Church. Why isn’t anybody raving about the terrible storytelling in Paw Patrol? Honestly, it’s because Paw Patrol isn’t likely to lead to salvation. Satan doesn’t care about it. Satan goes all in on things that are dangerous.

That’s something I tell every departing missionary: on your worst day, know that that’s the day Satan was most afraid of you.

Satan’s deceptions come in two ways: teaching that evil is good, and teaching that good is evil.  “Behold, false Christs and false prophets and false preachers and false teachers shall arise and shall deceive many.”

“Behold, false Christs and false prophets and false preachers and false teachers shall arise and shall deceive many.”

Maybe including me—I don’t claim to be perfect; I’m doing the best I can.  He’s a skilled imitator. And as genuine gospel truth has been given to the world in an ever-increasing abundance, he spreads the counterfeit coin of false doctrine.

He’s a skilled imitator. And as genuine gospel truth has been given to the world in an ever-increasing abundance, he spreads the counterfeit coin of false doctrine.

Okay, again—teaching that evil is good and good is evil, or—this is the best one—teaching that everything we do is good. And you can either do that by saying, “You’re great,” or just by teaching moral relativism, where there isn’t such thing as either.

Satan pacifies us and lures us away. When it says, “All is well in Zion,” it feels like he’s talking to a bunch. He’s not—he’s whispering to each of us, saying, “You’re doing great. In fact, you’re doing so well, maybe you should stand up and criticize that young woman for wearing what you believe to be an inappropriate swimsuit,” which is nowhere mentioned in the For the Strength of Youth.

And I’m not saying let’s wear whatever swimsuits we want, okay? I want to be real clear. But I am saying so many of the criticisms and judgments that we arrive at are based on a combination of incomplete information and an overdeveloped sense of our ability to judge.

The common judge in Israel is the bishop. And generally, when the bishop wants to talk to us about it, he does so during a PPI or a worthiness interview. And I’ve never seen a bishop call out anybody for doing something wrong at a swim party—ever.

And I’ve certainly never seen a bishop—particularly not my bishop, who buys all my books the first day they come out—stand up and say, “I saw someone’s horror shelf the other day.”

This is the most pernicious method of agency stealing that Satan has developed because it turns our strengths into unthinking action. We think we know so well that we can do what we will, for what we will is God’s will. And it just ain’t so.

Spoiler: God wins in the end.

I’m going to wrap it up real quick—sorry I’m going a little late.

Okay, I said I was going to come back to this thing, and I am right now. Okay, now’s the time.

Okay, I said I was going to come back to this thing, and I am right now. Okay, now’s the time.

The ideas aren’t just incomplete and wildly inaccurate; they’re actively harmful, okay? Because this is the conclusion: yes, he tells others, “You’re doing great. Don’t change. Judge the people around you based on things that are nowhere mentioned in the scriptures, let alone part of the gospel,” which, as we have seen, is God getting us home.

The ideas aren’t just incomplete and wildly inaccurate; they’re actively harmful, okay? Because this is the conclusion: yes, he tells others, “You’re doing great. Don’t change. Judge the people around you based on things that are nowhere mentioned in the scriptures, let alone part of the gospel,” which, as we have seen, is God getting us home.

Okay, so my thesis, of course, is horror is awesome, and everyone should read it.

No, my thesis is: God and goodness will win in the end. We cannot stop it, we cannot hinder it, we can’t even help it from a net value purpose. Because even when we try and help, we’re using energy God gave us and bodies God gave us. So, everything we do is a debt owed to God.

So, He gives us the energy to do things energetically for Him, oh, we still owe Him. And there’s lots of scriptures about that. Nothing we do has a net positive gain for Heavenly Father—nothing.

All we can do is try our best to stand with it, to recognize the framework God has created, exercise our agency the best we can in hope and faith, and in doing so someday arrive at the end of our own personal, horrifying, terrible, uplifting, and redemptive horror story—where we, like the Savior, follow the gospel, ascend to our Father, and are held in His bosom for all time.

And I say these things in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Q&A

Scott: So I’m going to give you a hard question. Ready? You live a long, long time ago. Your name’s Mormon. You get these records. The writer you are today—how would you do the Book of Mormon differently?

Michael: Okay, I gotta be honest. The writer I am today dies in the first battle Mormon ever went to, ’cause, like, look—I got a body made for writing, okay? I’m not a military type. No, I—again, I think that’s actually a really good question. I think I would have written something completely different, which is a) why Heavenly Father didn’t use me, but b) more importantly, we’ve seen time and again during this conference that words change according to the speaker. And it doesn’t mean that God is wrong, okay?

I told my wife earlier, I said, “Every single thing the prophet says is wrong.” Wait for it— in that he’s communicating—when he says “thus saith the Lord,” he is communicating God’s eternal truth, and you just can’t pour the Pacific Ocean into a thimble. Ever. No matter how earnest the thimble is. I’m not saying the prophet doesn’t speak truth or he doesn’t get it right. It’s a bit of a nuance thing—that we’re imperfect creatures, and no matter how hard we try, we all mess up. The atonement is for everyone, right?

Scott: That’s really good. Yeah, I think it’s Brigham Young said, “We can’t even understand the revelations that are given.” I’m paraphrasing, of course. But what’s your favorite horror film?

Michael: Oh, other than the Joseph Smith one?, which—honestly, I’m not even kidding, I’m still like, “Let’s not watch that, kids, ’cause that’s too hard for Daddy.” Um, I really—I do like the kind of intellectual ones. So, I really enjoyed —what was the… Now I’m blanking. Part of asking me my favorite is like, “I don’t know, yesterday I saw this thing, and it’s my favorite,” because I love so many things. I’m the easiest audience. I’m a horror writer, and I go to the horror theater, I’ll say Insidious because it’s got a good story. I went and saw Insidious with a kid in my Sunday School class ’cause he was having trouble. I was like, “Let’s go to a movie.” And I sat in the cool seats behind the, you know, the handicap section ’cause they’ve got the gate so you can put your feet up. A scary thing happened, and I went like that—both legs and both arms straight in the air. And for real, like, it was a packed theater, so three rows of people were going, “Help the epileptic man!” So, I ruined the theater experience for a lot of people.

So I’ll say Insidious because it certainly got me to jump in the air, and it was about a family. I love horror stories about families because, even, you know, if the horror story ends badly—if everybody dies at the end—first of all, I didn’t die, so I’m a survivor. And that’s one of the wonderful things about horror stories—they teach like, “Ah, I beat that! I’m enough, you know?”

And adding a family to it puts it in this wonderful framework that we all understand and is so important—and that Satan definitely attacks today. I love that there’s a return of horror stories that have a family center. Even something like The Exorcist, which I’m not saying to go out and watch, and I’m not encouraging people to watch—but the scariest thing about it is this mom who’s losing her daughter. And when you focus on that kind of thing, you can definitely see why Satan goes, “Let’s not have that. Let’s have naked people in the woods—that’s much better for my purposes.”

Scott: Okay. So this is a two-part question. What do you recommend for first-time horror readers—books for their first foray into horror? And the second part is: which one of your books should they read first?

Michael: Can I just answer both with the same thing?

Scott: Sure, absolutely.

Michael: That is kind of an impossible question to answer because so much goes into that selection. So, here’s how I started reading horror. My father really was the world expert on Stephen King. And he had tens of thousands of books in our home library, and he arranged them by appropriateness—by height. So he said, “If you can reach it—you can read it.” And all the kids’ books were down here. So I, being a very smart child, went and got a chair and grabbed a bunch of things I probably shouldn’t have. And my father was like—well, this is a very dad thing—”I’m proud of you, son. Go for it. You know, you beat the old man—you deserve to scare yourself.”

Um, so my background is very different from others. I would say for mine, if you like, you know, a very soft horror, the first indie horror novel to be nominated as a finalist for the Bram Stoker Award is The Ride-Along. But all of mine are set with redemptive themes. So, it just kind of depends where you are personally.

For anybody, I think one of the best horror novels ever written is The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson. It’s just so well done. I can remember reading that in my dad’s office—just sitting back there.

Scott: Delayna just whispered in my ear from six feet away here. She just commented—we have some of his books here in the bookstore, so you can take a look at them and do what you always do in bookstores—look through them and look at the back, see if you like it or not.

Just combining a couple questions here. One person’s commenting about the R-rated movies and horror and not feeling the Spirit and such. And the other person is asking about good horror versus bad horror. I think a lot of Latter-day Saints look at some of the bad horror and say, “I don’t want any horror at all.”

Michael: Absolutely. And I support that. Here’s the thing—that’s what I always say when I think I’m about to be smart. It never happens. Here’s the thing: chemotherapy consists of putting poison into a person. That’s what chemotherapy is. You go to your wellness check-up, and he’s like, “You look great—want some chemo?” No, ’cause it would hurt you, okay? Chemotherapy is much better than cancer. And part of what I want people to understand is some of us who read horror or who watch horror—we need it.

I have severe mental health problems. I have major depressive disorder, psychotic breaks, suicidal tendencies—and those are just the top three in a long list of all-time hits. And I can joke about it because they’re mine, so I get to. Um, and sometimes I need a horror novel or a horror movie. Regardless of what genre you’re talking about, 95% of it is bad for us. I don’t care if it’s a kids’ show, a romance, an action story—whatever. There are mostly bad elements in most of them, and that’s why we’re counseled to look for good books. One of the things that I encourage people—if you don’t like it, don’t like it. That’s fine.

I used to hate romance. I kind of like romance now, which is why I wrote some. It’s like—it’s kind of fun. Um, not everything is for everyone. There are some things that I think are just pure evil. I think erotica as a product is an evil product. I don’t think everyone involved in making erotica is evil—I don’t know where they came from, and I really don’t want to judge that stuff. I’m hoping for the loophole—”Judge not that ye be not judged”—like I’ll get to heaven, and Heavenly Father’s like, “Uh-uh,” and I go, “But I didn’t judge people.” He’s like, “Shoot,” and lets me in.

Scott: Thank you for your time. We really appreciate you talking to us.

Michael: Thank you all.

TOPICS

Horror

Books

Movies

The Gospel and Horror