Aaron Miller

Church Finances–Recent Controversies and Broader Perspectives

August 2024

Summary

Aaron Miller provides a detailed examination of the Church’s financial history, operations, and controversies. He outlines the evolution of the Church’s financial structure, including its approach to tithing, investments, and global operations.

Introduction

Scott Gordon: Our next speaker is Aaron Miller. He’s a professor at BYU, and we’re really happy to have him with us today to talk about a subject that, honestly, is near and dear to my heart as well: Church finances. With that, I’ll turn the time over to Aaron.

Presentation

Aaron Miller: Hi, everybody. I don’t know whose idea it was to schedule a session on finances on a Friday afternoon after you’ve all had lunch and have already worked your brains hard thus far today hearing very smart people.

Like Scott, this is a topic that’s very dear to me because it overlaps so heavily with what I do professionally, and I’ll talk about that in a moment. It’s also a topic around which there’s a lot of misconceptions—some deliberately generated and many innocently misunderstood. But it’s worth spending some time on.

I will warn you, though: I have prepared a lot of material here, so I’ll be going through it quickly. Hopefully, I won’t skim too shallowly, so it’s not useful to you, and hopefully, I won’t cover too much. The material I’m covering has enough details and enough different controversies and other issues that are worth mentioning that I tried to fit in as many as I thought was wise—which maybe was too many, but we’ll see.

Outline of Today’s Presentation

Here’s a quick outline of what we’re going to cover:

- A brief financial history of the Church. I have a little timeline with some details that maybe only I care about—and I’m not a Church historian either, by the way, so I should qualify myself that way.

- Church finances today: what we know and what we don’t know.

- The Church and U.S. tax law, specifically its charitable tax status with the federal government.

- The SEC settlement and some interesting details related to it that are often overlooked.

- The James Huntsman lawsuit and similar lawsuits alleging that the Church defrauded tithe payers.

- Transparency in general, as the issue of the Church’s transparency around its finances is often discussed.

- Church finances in context, compared to other large wealth funds.

- The Church as a philanthropy—a common discussion point about what the Church ought to do with its money.

- Finally, I’ll share why I pay tithing, in the context of everything else we’ve already discussed.

About Me

I teach at BYU in the Romney Institute of Public Service and Ethics. I’ve been there altogether now for 18 years. One of my colleagues, Larry Walters, is here, and I deeply admire him and miss him dearly since he retired. I’m happy to see you, Larry.

I also serve as an associate director at the Ballard Center for Social Impact, one of the largest social impact centers in the world at any university. We have thousands of students every year working on improving the world in meaningful ways.

I teach business ethics and nonprofit structure, tax, and finance classes. I also do research and writing around philanthropy and ethics and serve on a couple of nonprofit boards.

Financial History of the Church

Let’s dig in. I’ll try to go fast enough to cover this broad range of topics but also provide enough detail to point out some things that may not be commonly known.

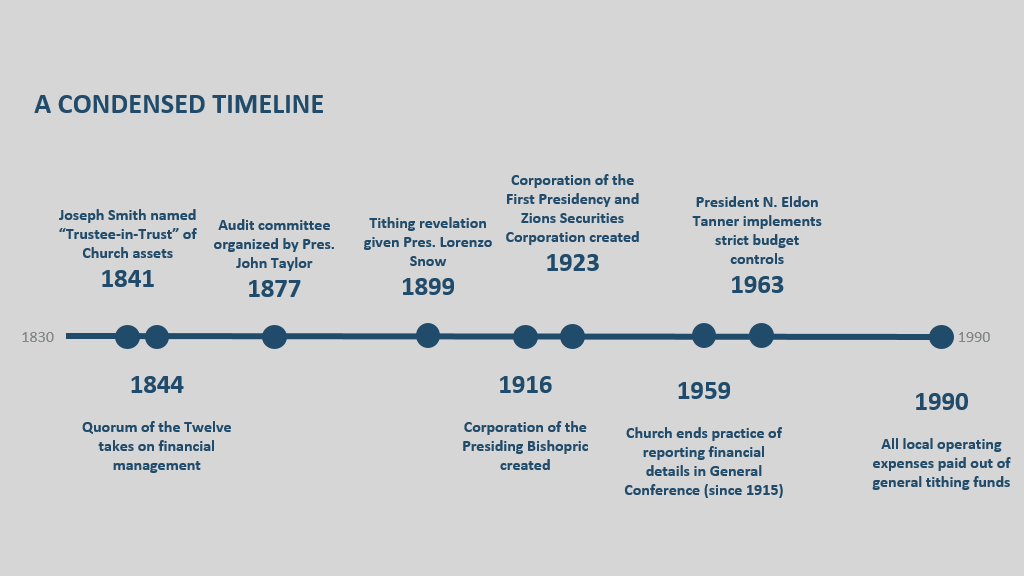

Here’s a very condensed timeline of moments in Church history relevant to today’s topic:

- 1841: Joseph Smith was named as trustee-in-trust of Church assets, establishing the original legal structure under which all Church assets were owned and managed as a trust, not a corporation.

- 1844: The management of Church finances shifted to the Quorum of the Twelve.

- 1877: President Taylor organized the first audit committee for the Church to oversee the management of Church finances.

- 1899 that President Lorenzo Snow received his famous revelation on tithing, which rescued the Church from dire financial circumstances.

- In 1916, the Church began operating under a corporation. I want to pause here to clarify: a corporation is a legal structure that doesn’t necessarily imply shareholders or a for-profit status. The fundamental nature of a corporation starts with having a board of directors, who collectively decide what should happen. The corporation is then subject to the decisions of the board. Today, you can have both for-profit corporations, which have owners such as shareholders, or nonprofit corporations, which don’t have owners. Nonprofit corporations are controlled by their boards of directors.

- In 1923, the Corporation of the First Presidency and the Zion Securities Corporation were created.

- In 1959, the Church ended its practice of reporting financial details in General Conference. Between 1915 and 1959, the Church reported general financial details to its membership during General Conference.

- In 1963, President N. Eldon Tanner was called to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and placed directly into the First Presidency to manage Church finances more carefully. This was necessitated by the Church’s overextension in constructing chapels worldwide. President Tanner was tasked with reigning in Church spending.

- In 1990, a change was implemented so that all local Church expenses would be paid out of the general tithing fund. Before this a ward would get its budget from the Church and then spend it; a lot of expenses were not centralized until 1990.

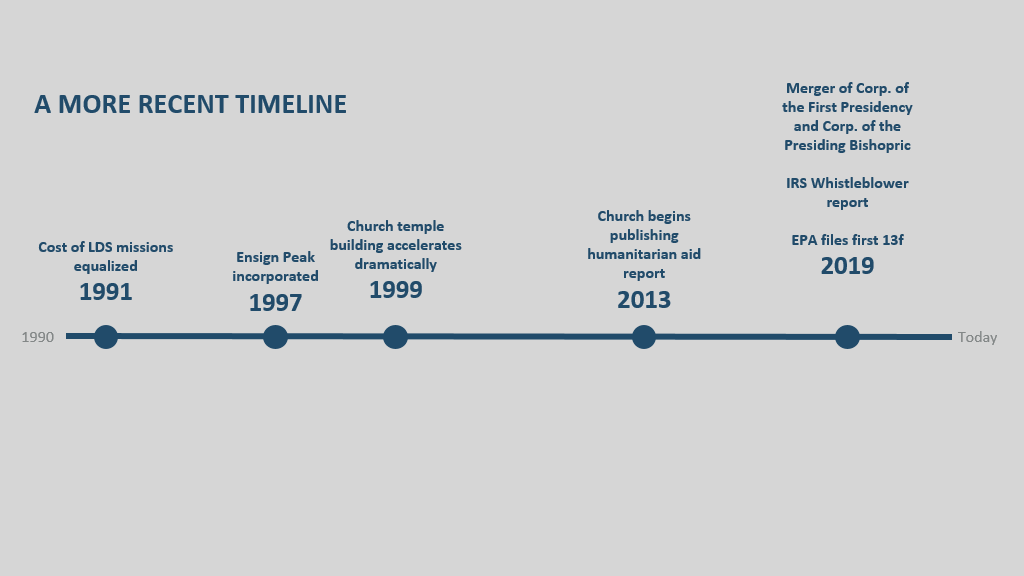

In 1991, LDS mission financial support was equalized. This is a fascinating topic, particularly under nonprofit tax law. If someone donates to a charity but specifies that the money must go to a particular individual, that donation is not deductible for tax purposes. The Church negotiated with the IRS to craft a missionary financial support system that allowed for charitable tax deductions. The key is that support funds go to the missionary fund, which supports all missionaries, rather than being earmarked for an individual. This equalization is part of what ensures compliance with tax laws. I think it’s cool and very savvy actually on the part of the Church, to figure out how to do that. Plus I think it accounted well for the financial discrepancies that would happen to families based on where a missionary was called to serve.

For example, my oldest brother served in Paris in the late 1980s, which at the time was one of the most expensive missions to support. Our family bore the direct financial responsibility. Fast forward about eight years, and my younger brother was also called to Paris. By this time, the Church had equalized missionary financial support, and we breathed a sigh of relief the second time around.

- In 1997, Ensign Peak was incorporated. Ensign Peak is at the center of many controversies in the media regarding Church finances because it is the nonprofit organization that manages the majority of the Church’s financial holdings. Prior to its creation, the Church managed its financial holdings within the Church proper—though technically across various legal entities. Ensign Peak is also a nonprofit, and while its primary purpose is to invest financial resources, it appropriately operates under nonprofit tax law.

- In 1999, the Church began a marked increase in temple building. Temples are significant financial commitments. A friend of mine, who worked in the Missionary Department and was involved in the Missionary Training Center (MTC) expansion, shared an anecdote about President Packer. He reportedly leaned forward during a committee meeting about the proposed budget for the MTC additions and asked, “How many temples is this going to cost me?” This highlights the deep importance and the immense financial dedication the Church places on temple construction worldwide.

- In 2013, the Church began publishing its humanitarian aid reports, with the most recent published earlier this year. In 2022, the Church reported over $1.3 billion in humanitarian aid efforts within the U.S. and globally.

- In 2019, significant public scrutiny of Church finances emerged. While speculation had existed for years, it was the public release of the IRS whistleblower report and Ensign Peak’s first filing of Form 13F as part of an SEC settlement that brought these issues to the forefront, and we will talk about more about that in a moment.

It’s important to note that the Church’s financial history has experienced both prosperity and challenges over time. The narrative that the Church struggled financially until President Tanner’s leadership and then steadily improved thereafter is overly simplistic. For example, in the 1940s, Church annual expenses were only 28% of annual tithing revenue, demonstrating financial strength. However, by 1962, just prior to President Tanner’s efforts, the Church ran a $32 million deficit, largely due to rapid chapel construction.

Church humanitarian efforts have also evolved significantly. The Church welfare program began in 1936 under Elder Melvin J. Ballard. International humanitarian efforts grew substantially in 1985, when Elder M. Russell Ballard visited Ethiopia during a famine to represent the Church’s aid efforts. Notably, Elder M. Russell Ballard was the grandson of Elder Melvin J. Ballard, creating a poignant legacy of service.

The key takeaway is this: today’s Church is easily the largest and most complex it has ever been in history, dating back to Adam. It operates in more places, faces greater financial demands, and must navigate an unprecedented array of government regulations. This level of complexity is precisely what we would expect in carrying forward the Lord’s work in the modern era.

Today, some people seem to long for the Church to resemble the simplicity of ancient times—less complex, less worried about legal regulations, and generally more straightforward. But governments and legal systems today are more complex than ever, and the Church must operate within these systems, not just in the United States but all over the world. To fulfill its mission while respecting the laws of the land, the Church has to operate in a very complicated way. If you’ve ever spoken with a Church area legal counsel, you’d know just how immense and ongoing the legal challenges are in managing the Church’s operations in various regions. That’s the nature of doing this kind of work globally.

Church Finances Today

What We Know

Now let’s talk about Church finances today—what we know.

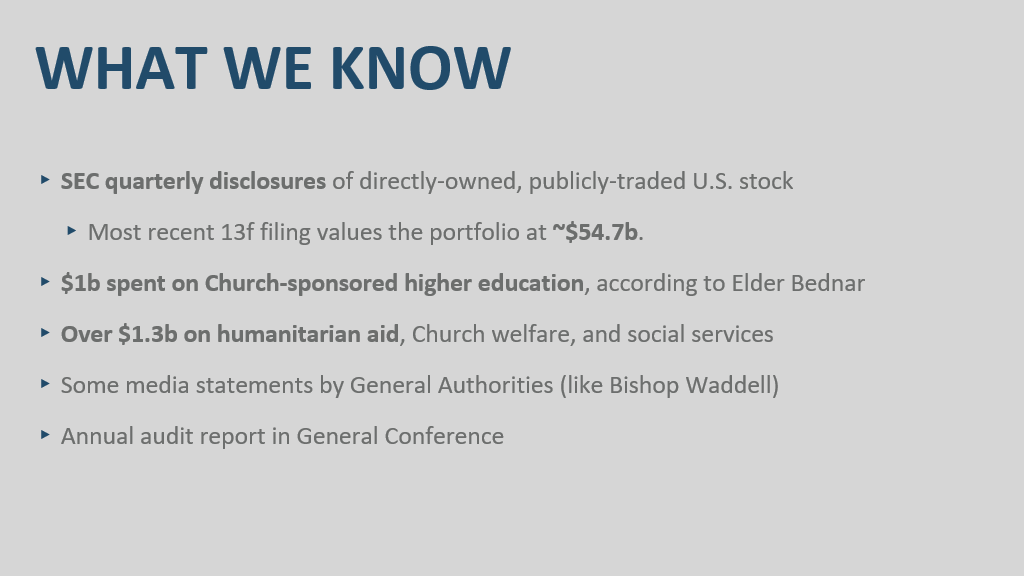

We know some details because of the Church’s 13F filings, which are required by the SEC. The Church files these quarterly reports, showing its portfolio of publicly traded securities, which is currently valued at $54.7 billion. The SEC requires this report because any organization or individual trading a total portfolio above a certain size has to disclose to the public what it has traded, what it has bought and sold, and what it owns after the fact. This report serves as a quarterly disclosure of what happened in the previous quarter.

Not only do we know the total worth of this portfolio each quarter when Ensign Peak files this report, but we also learn which stocks the organization owns, which companies are involved, and so on.

However, this report does not include any real estate holdings or privately traded investments—investments that cannot be purchased on the New York Stock Exchange, NASDAQ, or similar platforms. And that’s pretty sizable actually, the amount that doesn’t fit into this filing.

We know, according to Elder Bednar—and Elder Gilbert has since repeated this number—that the Church spends around a billion dollars a year on higher education. That includes BYU, BYU–Idaho, BYU–Hawaii, and Ensign College. I don’t know if this number includes seminaries and institutes; my guess is that it does. It’s a big number—a billion is a lot of money to spend on Church education.

I will very rarely, during this conversation, tell you what my guesses are about things, and I always want to make sure you know it’s just a total guess. Okay, so this is me making a rough guess. My guess is that the Church probably spends about $177,000 per BYU student, in addition to what they’re already paying in tuition and everything. It’s a massive subsidy to education. BYU is doing a phenomenal thing that way. Obviously, I’m biased because I get paid out of that.

On the humanitarian side, the Church recently announced that it spent over $1.3 billion in humanitarian aid. That figure covers a wide range of efforts, including global philanthropy, the Church’s welfare programs, and other social services like adoption services.

We’ve also heard some additional details from Bishop Waddell, who mentioned in an interview with 60 Minutes that the Church’s investment in City Creek Center has been profitable. He didn’t give exact numbers, but it’s clear the Church has made back what it invested there.

One more thing we know is that the Church conducts financial audits regularly. If you’ve ever been part of a ward or branch audit, you know what I mean. These happen twice a year—more frequently than most organizations, which typically do them annually. It’s an intense process to ensure every financial detail is handled correctly. There’s a strong culture of auditing within the Church, and it’s rooted in this principle of respecting the “widow’s mite.” That culture permeates everything the Church does financially. It shows up all the time.

What We Don’t Know

So, okay, what we don’t know is pretty much everything else, and I include myself in this. I want to be really clear: I’m not up here speaking as someone with inside knowledge. In fact, I think it’s kind of nice that I don’t have any, because I can be blunt about it. Nobody has brought me in, nobody’s shown me financial reports, and I haven’t had access to any information that’s not publicly available. I’m just speaking based on what’s been made public.

The fact that I can hopefully give you confidence that the Church is operating in a way that is lawful and respectful of regulations—well, that’s something I feel good about. We’ll talk about the SEC settlement in a moment, but the Church is operating within the bounds it ought to as a member of society. That’s something I can say with confidence based on what we know.

Now, I will say this: I think it’s almost certainly true that the $1 billion figure (referring to humanitarian aid) is not accurate, and there are reasonable guesses that the real number is actually higher. It’s also definitely true that the IRS whistleblower data, which is now about five years old, is out of date. Beyond that, it was probably inaccurate to begin with—at the very least, incomplete. Most other analyses you’ll find out there, including interesting ones like the Widow’s Mite Report, are based on assumptions and projections, not insider information. That’s how they compensate for missing data—they make projections. To their credit, they’re very transparent about how they arrive at those assumptions, so you can see why they’re guessing the way they are, but there’s still a lot of guessing involved when you don’t have all the details.

The Church and U.S. Tax Law

Common Misconceptions About Nonprofits

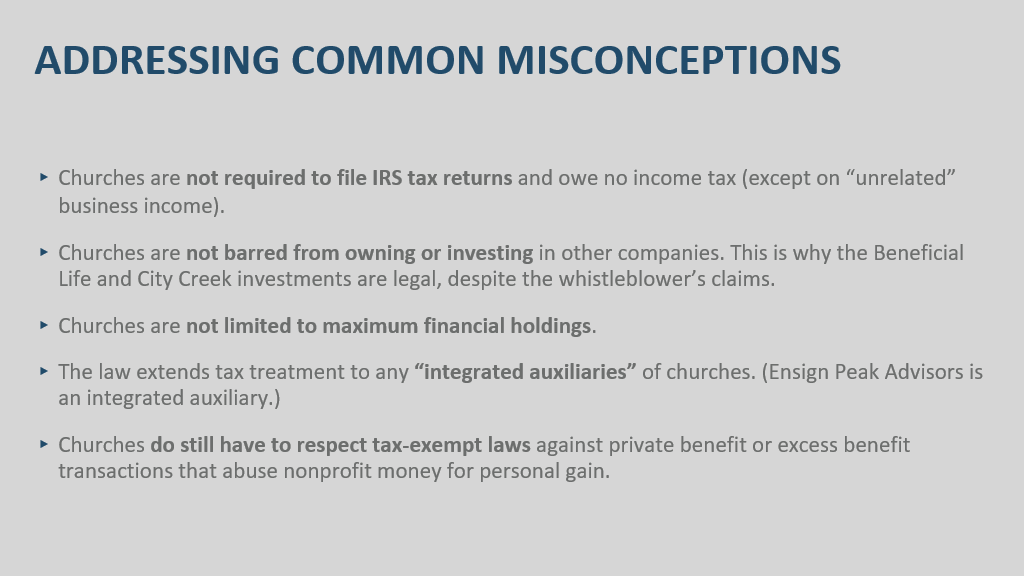

Let’s talk about some common misconceptions about nonprofits. This isn’t just about the Church in particular but about nonprofits generally, though it does get applied to the Church. The Church’s tax-exempt status is what’s called a 501(c)(3). That’s a phrase many of you have probably heard before. A “C3” designation means that under federal tax law, the Church is considered a charity. Now, charity in the colloquial sense might mean philanthropy, but charity in a legal sense means an organization that qualifies as a 501(c)(3). Lots of things can be considered “charities” under federal tax law—a youth soccer team, for example, or a scientific research institution. A lot of different organizations qualify for charitable status, and the Church is one of them.

Churches, in particular, get special status under tax law. Since 1913, when the federal income tax was first enacted by Congress, churches have not been required to file a tax return. And “church” doesn’t just mean a place of worship; it can mean a lot of things. For example, BYU is treated as a church under tax law, which is why you don’t see a tax return for BYU. Again, all of this is appropriate under federal tax law.

This is why we don’t see tax returns from the Church—they don’t even send them in. There’s a thing called a 990-T, but it doesn’t apply to very much, so we won’t get into that.

It’s also worth noting that churches, like other nonprofits, are not barred from owning or investing in things. They can own stocks, and they can buy and sell investments. It makes the most sense, right? It would be really strange if we said, “Hey, if you’re a church, you have to put your money in a savings account and nothing else.” That would be an odd way to require someone to manage their financial resources. Churches have essentially the same investment opportunities at their disposal as any other entity would. This is why Beneficial Life and City Creek investments are legal by the way, despite the whistleblower’s claims.

Churches are not limited in their financial holdings—there’s no cap for how much they can own. That means there’s no violation of the law in that regard. Also, the tax law allows for what’s called integrated auxiliaries. These are nonprofit corporations so closely tied to the Church that they share its tax treatment. Ensign Peak is one of these auxiliaries, which is why it doesn’t file a separate tax return.

This is a key point the whistleblower has misunderstood. In his first report, he didn’t even acknowledge the existence of integrated auxiliaries, which shows his legal understanding was flawed from the start.

Churches, however, must still follow laws against private benefit or excess benefit transactions. If Church leaders were taking assets for personal gain, the IRS would step in. That hasn’t happened, which underscores the Church’s compliance with these laws.

It’s also worth saying: there are no hidden Ferraris or Italian villas being bought with tithing funds. Church leaders are not using the Church’s money to enrich themselves. If that were happening, whistleblowers would have surfaced by now. Claims that the Church is obsessed with money seem strange when you consider how much its leaders sacrifice financially to serve. Even the employees at Ensign Peak are underpaid—I’ve spoken to some of them and can confirm this.

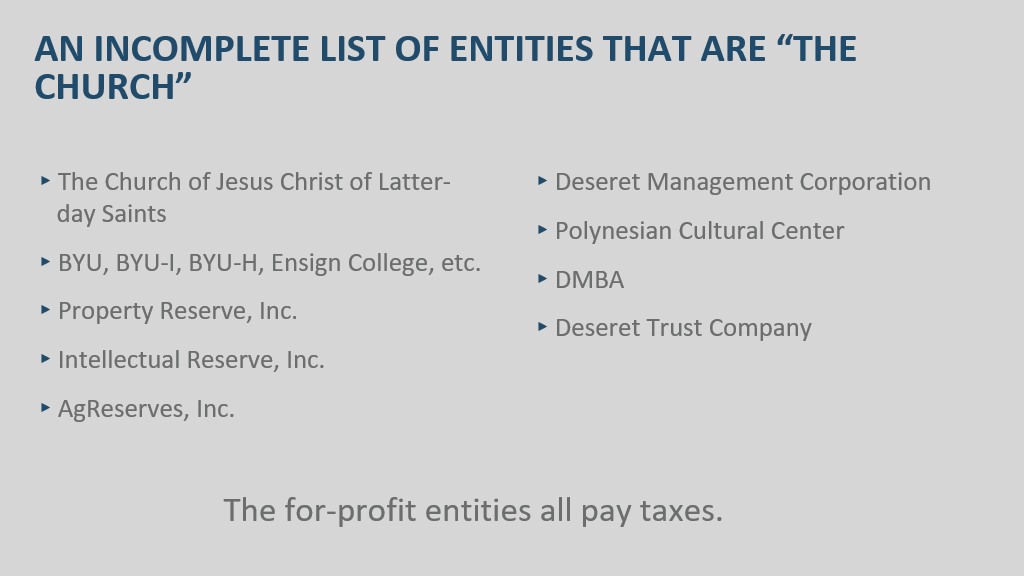

Another misconception is that the Church is a single legal entity. Spiritually, it is, but legally, it’s not. The Church operates through many entities, each legally distinct. For example, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, each of the higher education institutions, Property Reserve manages a large portion of the real estate, Intellectual Reserve owns all the copyrights, AgReserves oversees agricultural real estate, and Deseret Management Corporation handles business ventures like Deseret News. The Polynesian Cultural Center in Hawaii is a separate legal entity, DMBA, which is an insurance company, is a separate legal company. Same goes for Deseret Trust.

These are all distinct legal entities that are part of what we colloquially call “The Church.” And they are all part of one thing in the sense that they’re controlled centrally by Church leadership, but they are all legally distinct from each other. And this list isn’t even close to complete because I haven’t gone international, and the Church has I don’t know how many International entities under this umbrella. But this list also missed a bunch of the domestic ones.

And I forgot to say, the for-profit entities–they all pay taxes. Any for-profit entity controlled or managed by the Church pays income taxes on their profits.They are not exempt from that just because they’re owned by the Church.

The Whistleblower Report

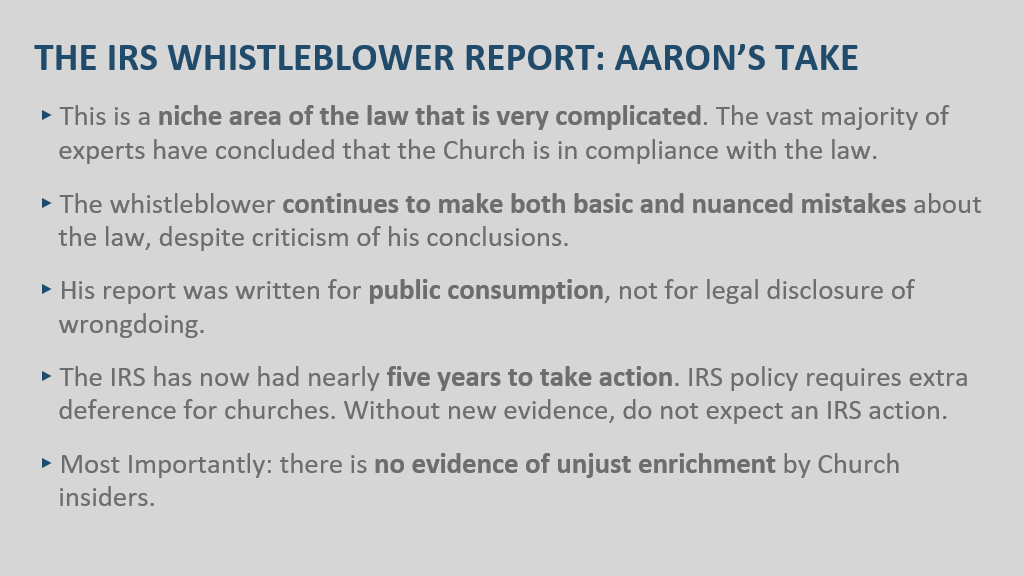

Now, about the whistleblower report itself. Nonprofit law is a niche field and very complex. Experts, both inside and outside the Church, agree that even if the whistleblower’s claims were true, the Church is operating within the law. The whistleblower has the law wrong, continually. Unfortunately, the whistleblower also continues to make both basic and nuanced mistakes about tax law, which really frustrates me because by now, years later, there’s no excuse for these errors.

There has been so much public commentary and analysis of this, like in the 60 Minutes report where the whistleblower said, ‘well I’m not a tax law expert,’ but he had four years to become one. That’s not an acceptable excuse.

The report that he submitted to the IRS was undoubtedly written for public consumption. I mean, you know this just by seeing that it was a “letter to an IRS director”—which may ring a bell, right? You don’t title something like that for an IRS examiner; no IRS examiner got anything out of that title.

It is 100% certain that the report was written for public consumption. However, because it was filed as a whistleblower report, it gave the whistleblower legal cover to disclose information despite a non-disclosure agreement. So, what he did was legal, but it wasn’t really written for the IRS.

The IRS has now had over five years to take action on this report and still hasn’t done so. The fact that it hasn’t means you can trust it’s probably not going to.

By the way, the IRS actually requires extra deference for churches by law, and without new evidence, I don’t think you should expect IRS action on these claims. Like I said, there’s no evidence of unjust enrichment, which is what federal nonprofit tax laws are mostly meant to prevent.

The SEC Settlement

Regarding the SEC settlement, I have very little expertise in this area, and there is very little expert commentary in this area.

I have come to the conclusion now, a year and a half later or whatever it is, that this is such a niche set of consequences that you couldn’t even call this a practice area. You couldn’t even say, “Yeah, there are attorneys who specialize in 13F filing.” I just don’t think that’s true. I have searched, I have talked with other people who have more expertise in securities law, and they shrug their shoulders. This was a very unique set of circumstances that led to this outcome. So, I’ll get into some details on it.

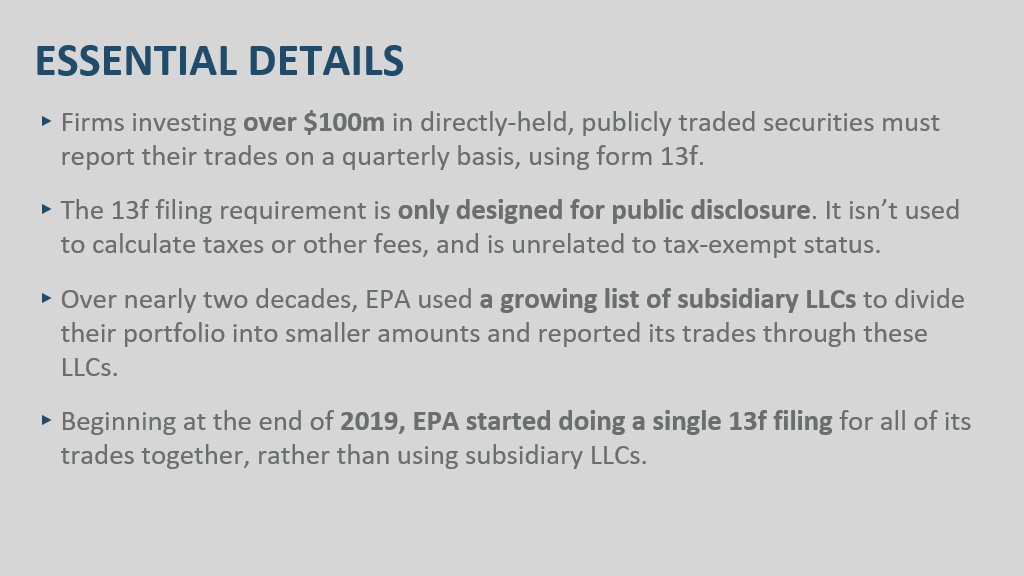

If you invest more than $100 million, you have to report it with that form I told you about. The only consequence of this report is public disclosure; there are no tax consequences attached to the 13F filings. That has zero effect on their tax-exempt status because we’re talking about the SEC versus the IRS. The only reason this report exists is so we can know what large financial institutions have done with their money after they’ve done it. That is the purpose of this report. In fact, many in the industry have argued that $100 million is far too low of a threshold for this requirement.

Over two decades, here’s what happened:

Ensign Peak used a growing list of subsidiary LLCs. So, Ensign Peak owned a growing list of smaller organizations, and then it started reporting its trades through those LLCs. The purpose was to avoid making it publicly known what financial investments the Church owned and managed.

It was at the end of 2019 that Ensign Peak started doing a single filing.

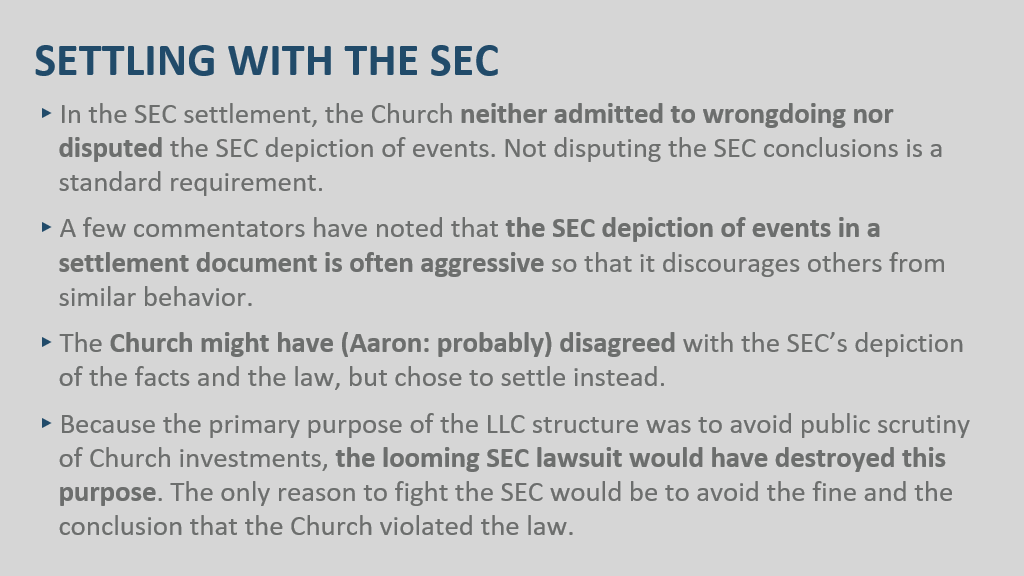

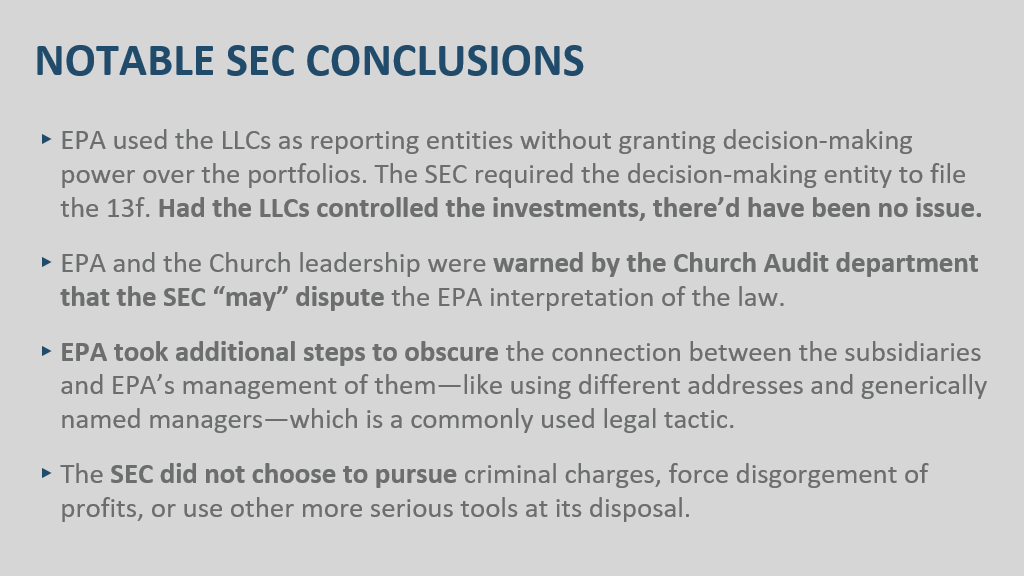

In the SEC settlement, the Church neither admitted wrongdoing nor disputed the SEC’s depiction of events.That’s a very common outcome in a settlement, where the party that’s settling says, “We don’t agree with what you said, but we also aren’t arguing with what you said.” Now, that sounds like a strange distinction, but legally, it’s actually really important because the Church is saying, “We don’t endorse what the SEC is saying about this, but we’re not going to fight them on it.”

It is true that the Church Audit Department warned Church leaders that the SEC may dispute the structure the Church was using. That term may actually carries a lot of weight, legally speaking, because according to the SEC, it wasn’t like the Church Audit Department showed up and said, “This is going to get punished; you’re breaking the law.” It’s been portrayed that way, but even the SEC doesn’t claim that happened.

It is true that Ensign Peak took additional steps to obscure the LLCs, giving them generic names and even using generically named managers. That is 100% the product of creative lawyering. I’m just telling you—there are lawyers who specialize in obscuring financial assets because of the wisdom in protecting them for legal purposes, and that’s just creative lawyers. You can think that’s terrible still, because it’s lawyers, but, I’m saying that as a former lawyer.

A few commentators have noted that the SEC, typically in a settlement document, will be as aggressive as they can get away with in interpreting the details. So, you can expect that the way the SEC framed certain topics may not have actually been true according to the framing.

The Church might have—and I think probably did—disagree with the SEC’s depiction of the facts and the law but chose to settle instead. The reason the Church chose to settle makes all kinds of sense in the world, which is that the whole purpose of this structure was to obscure their financial trades. Once the SEC brought the charges, that benefit was gone.

Here are some notable things in the SEC settlement that are worth mentioning. Had the LLCs truly controlled the investments—because the charge was that the LLCs weren’t really controlling these investment decisions, it was Ensign Peak controlling all 13—as long as those 13 LLCs were not acting independently, that’s what violated this filing requirement.

Had the LLCs truly had independent control of the financial assets they were put in charge of, then the Church wouldn’t have broken the law, according to the SEC.

It is true that the Church Audit Department warned Church leaders that the SEC may dispute the structure the Church was using. That term may actually carries a lot of weight, legally speaking, because it wasn’t like the Church Audit Department—according to the SEC—showed up and said, “This is going to get punished; you’re breaking the law.” That’s been portrayed that way, but even the SEC doesn’t claim that happened.

It is true that Ensign Peak took additional steps to obscure the LLCs, giving them generic names and even using generically named managers. That is 100% the product of creative lawyering, I’m just telling you—there are lawyers who specialize in obscuring financial assets because of the wisdom in protecting them for legal purposes, and that’s just creative lawyers. You can think that’s terrible still, because it’s lawyers, but, I’m saying that as a former lawyer.

I think this is one of the most important and interesting points here: the SEC did not choose to pursue additional punishments, even though it could have. Well, it could have pursued them, but I don’t think it would have gotten them.

When the SEC goes after people for wrongdoing, it often goes after them for what’s called disgorgement, which means any of the profits you got from your behavior you have to give back or get rid of. The SEC didn’t pursue disgorgement against the Church or use any of the other more serious tools at their disposal.

This is why you’ve heard some commentators call this the equivalent of a speeding ticket under the law. But I think an even more apt description, personally, is that this is like getting a speeding ticket where there’s not a clearly posted sign. I think that’s a fair description of it, simply because the law on this appears, based on other experts, and there aren’t very many of them, appears to have some ambiguity as to how the SEC interprets it. There’s less ambiguity now because the SEC came after the Church for it.

The Huntsman Lawsuit

This one has gotten less attention, but there are enough people who know about it that I thought it was worth mentioning. There are also similar lawsuits floating around, following the model that James Huntsman set out.

James Huntsman, if you don’t know, is a former member of the Church who paid a large amount of tithing because of his wealth, and claims that the Church defrauded him out of his tithing by misrepresenting how the tithing would be used.

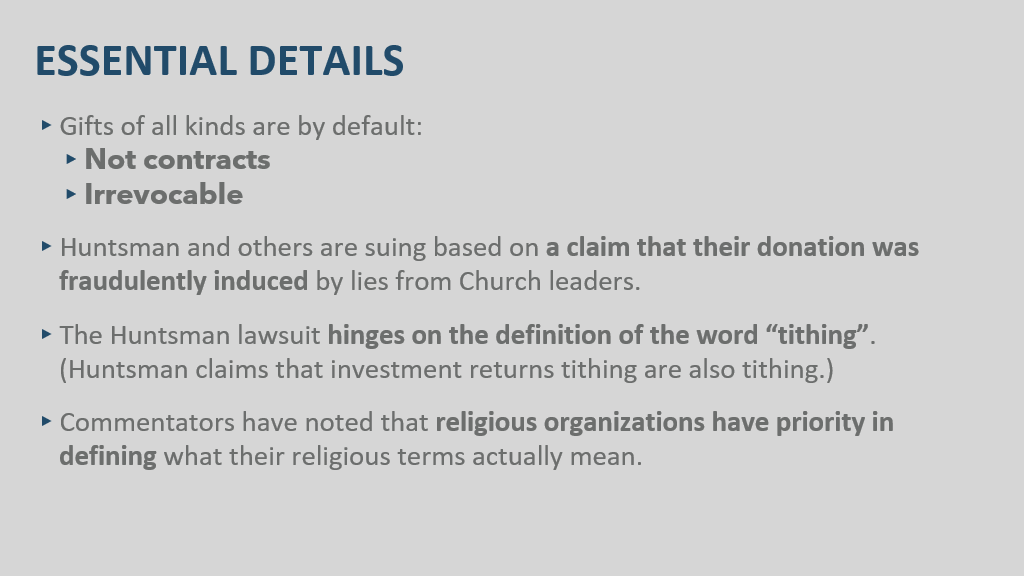

I want to emphasize that legally, gifts are not contracts. If you give something to somebody, it’s not a contract; once you give it, it’s done. That’s the second point: they’re irrevocable. Gifts are not contracts, and by default, gifts are irrevocable, meaning you can’t take them back.

James Huntsman and others are suing based on a claim that their donation was fraudulently induced. Very specifically, James Huntsman points to President Hinckley saying that tithing dollars would not be used to build City Creek, which the Church has explained came out of investment proceeds. Huntsman argues that the investment proceeds of tithing still count as tithing.

This is where the law is actually pretty important. Here, James Huntsman is claiming that his definition of tithing should prevail over the Church’s definition of tithing—essentially, that what the Church says tithing is conflicts with what James Huntsman defines as tithing.

That is an intensely unrealistic First Amendment issue, to claim that a church doesn’t get to define its own religious terms. If the government were to show up and say, “No, James Huntsman is right about what tithing means, and the Church is wrong,” that would be a violation of the First Amendment. Tithing means different things to different faiths, and for the government to step in here, at James Huntsman’s urging, and declare, “Hey Church, your definition of tithing is wrong,” would be a direct infringement on religious freedom, because religious organizations have priority in defining what their religious terms actually mean.

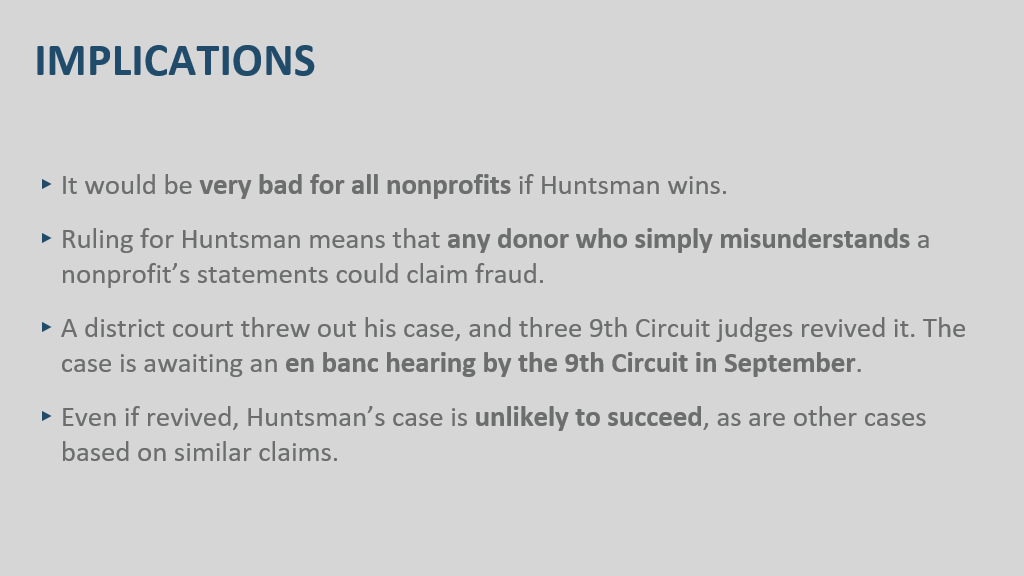

It would be bad for all nonprofits if James Huntsman wins, not just churches, because it means that any donor who misunderstands a nonprofit could claim fraud. For example, if I listen to what a nonprofit says, misunderstand what they mean, give them a donation, and later claim, “I misunderstood, you defrauded me,” that would create a dangerous legal precedent.

It would be a catastrophically bad decision for the court to uphold it, which is why it actually got dismissed at the district level. However, three Ninth Circuit judges revived it, and it’s now awaiting an en banc hearing, meaning more of the judges in the Ninth Circuit are going to hear it. It may still get booted like when the district court kicked it out. Even if it proceeds further in the legal process, I don’t think it’s going to get anywhere. I believe it’s very unlikely to succeed.

Transparency and Its Purposes

I teach ethics, and transparency is a topic I talk about in my classes. The reason transparency matters is to discourage wrongdoing. This is one of the reasons you want to use transparency—you want to put it in place so that transparency allows people to inspect what’s happening, ensuring that dishonest people won’t abuse the resources they’ve been trusted with.

Transparency also exists to provide information to those who are entitled to know.

Here are examples of non-public financial information that we might want to know but aren’t entitled to know:

- Church tax filings are one of them—all churches, not just the Church of Jesus Christ.

- Corporate tax filings are private.

- Finances of closely held companies are private.

- Individual tax filings are private—I don’t get to read any of your 1040s. For some of you, I might find it interesting, maybe for nerdy reasons, but those are private as well.

- Investment portfolios smaller than $100 million.

- Donations to Super PACs.

These are all examples of things where, in some cases, we might love to know what’s happening, but it’s private information according to the government.

Cost of Transparency

Disclosure requirements often lack important details. If you disclose but don’t disclose full details, it creates fertile ground for misunderstandings. It’s true that misunderstandings are unavoidable with available information because people will take details out of their full context.

There’s actually some research on something called the “Sunshine Effect,” by Cain, et al., which found that transparency, in some instances, actually encourages bad behavior. This happens because people disclose and then say, “Well, we told everybody, so we’re going to do the bad thing because we told them.”

Finally, with transparency disclosures, sometimes confidential information accidentally gets included. This is a common mistake in the nonprofit sector. Nonprofits are required to file a report of who their donors are and what amounts are donated above a certain threshold. That information is not public, but sometimes nonprofit accountants accidentally include it in the version of the tax filing that goes on the website. As a result, donors’ privacy is violated accidentally by nonprofits making this mistake.

Costs of Opacity

Being opaque has its costs too, though. Trust is hard to establish when you’re being opaque. Opportunity increases for false accusations because you’re not sharing information to dispute those accusations. It’s also expensive and time-consuming to keep things secret, and people are much more likely to reach inaccurate conclusions.

I am supremely confident that the leaders of the Church know everything I’ve just said. I think they understand the trade-offs. They know the benefits and the costs of disclosing financial data and have thus far chosen not to disclose it. I don’t have a reason to dispute that choice.

The Church and Financial Transparency

Does the Church owe financial transparency to its members or the public?

Legally, no.

Ethically, it’s a complex question that needs to weigh factors like:

- The implied contract between institutions and their supporters.

- The risks and benefits of expert managers being able to make decisions free of outside criticism.

- The rights of private institutions to be free from government intrusion.

I think all those things need to be considered when you think about this question.

Church Finances in Context

I haven’t updated this information from 2023 because it was a lot to look up.

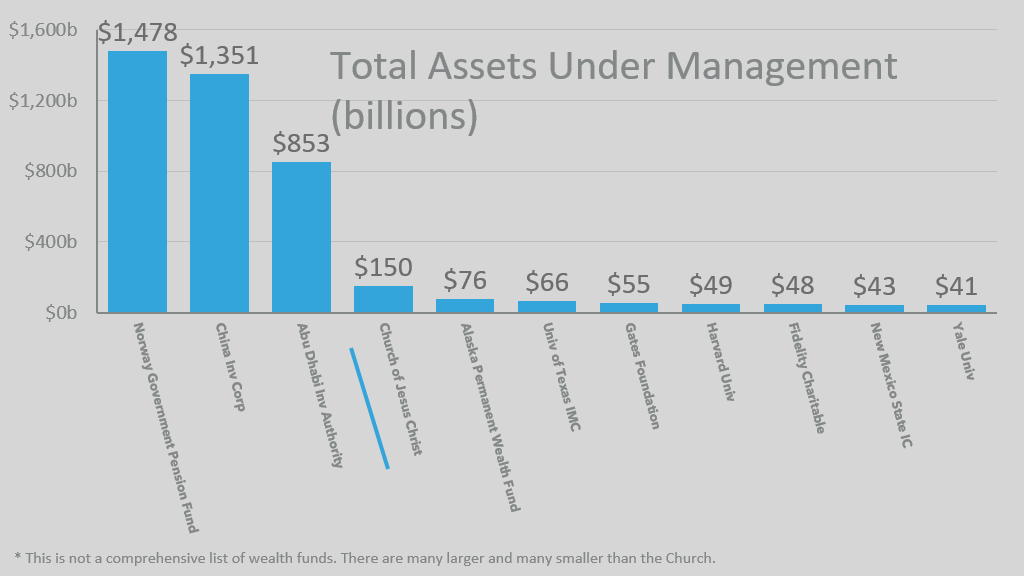

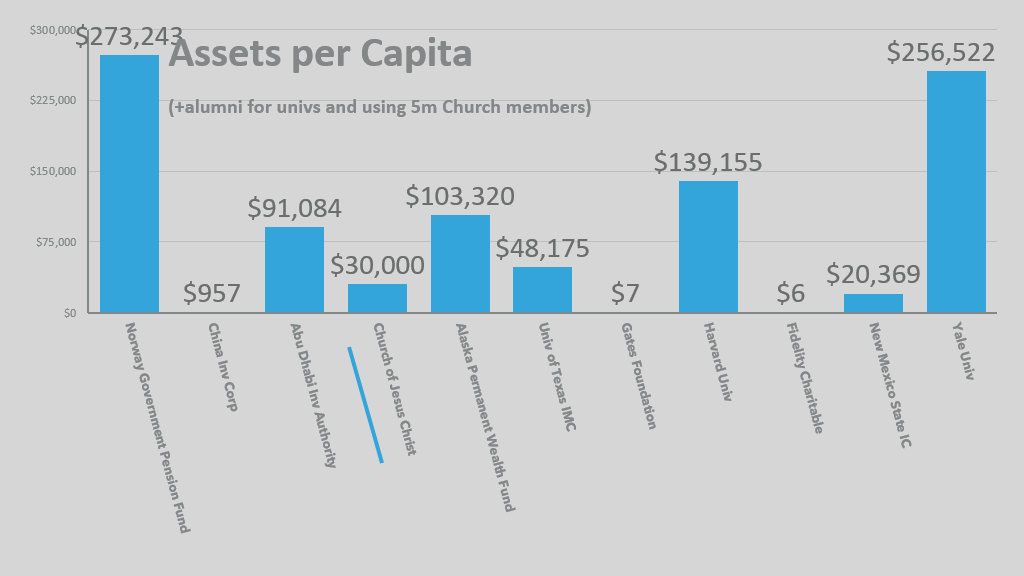

This is a chart that shows total assets under management (in billions) by different entities. I realize you’re too far away to read the text, so let me explain.

That really big one right there is the Norway Government Pension Fund, which manages about $1.5 trillion. That money comes from fees charged on people extracting oil and natural gas from government property. The next one is the China Investment Corporation, followed by Abu Dhabi.Then you see the Church—I put the number at $50 billion just as a guess. After that is the Alaska Permanent Wealth Fund, the University of Texas Investment Management Corporation, the Gates Foundation ($55 billion), Harvard University ($49 billion), an organization called Fidelity Charitable ($48 billion), the New Mexico State Investment Corporation ($43 billion), and Yale University ($41 billion).

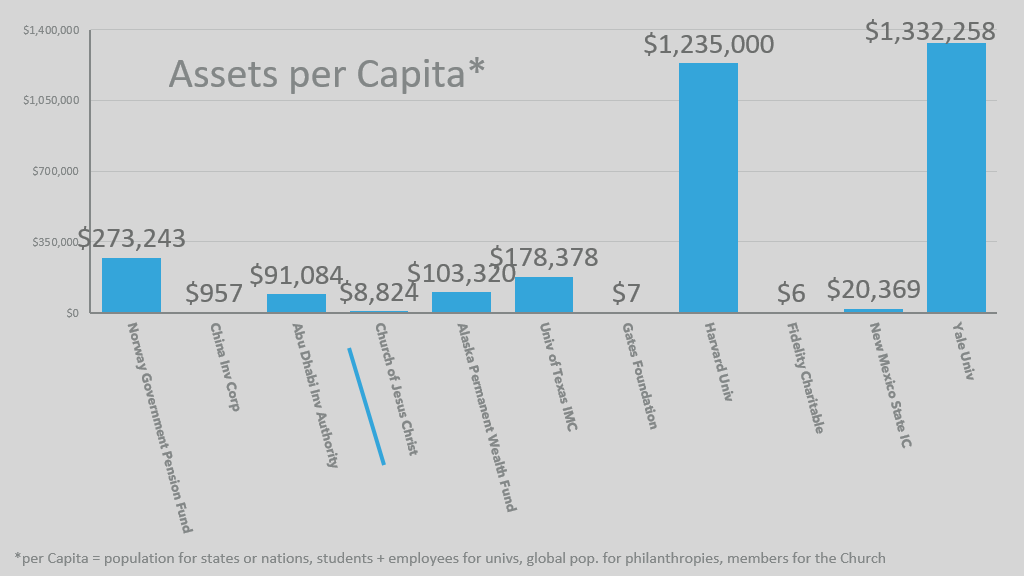

If you take those numbers and divide them by the population of people who might have a moral claim on the money, this gives the money per capita, basically.

- Norway has about $270,000 per citizen saved up in this investment account.

- Harvard, if you use just students, has $1.2 million saved up in investments per student.

- Yale has $1.3 million saved up per student.

I’ve had people criticize my numbers when I’ve done this. The Church is around $8,800 per capita, based on the math I was using, which involves some guessing.

If you adjust the assumptions—say, by throwing in alumni for Harvard and Yale or reducing the number of Church members from 17 million to 5 million (a figure some claim reflects the number of active, weekly Church members)—even making those changes, the Church still has $30,000 per member whereas Harvard has $139,000 per capita and Yale has $256,000 per capita.

Oh, and by the way, the reason I have Gates and Fidelity at $7 and $6 per capita is because, as philanthropic organizations, their only job is to give money away; I included the global population as the per capita base because they have a lot of money.

Okay, all right, so let’s get to the idea of giving it away.

The Church as a Philanthropy

According to Elder Bednar, the Church is not—and should not be—considered a primarily philanthropic organization. Its purpose is to preach the gospel and lead people through covenants back to their Heavenly Father and to Jesus Christ. That’s its purpose.

That said, it does engage in philanthropy—a sizable amount, actually. I’m going to skip some details because my time is going quickly here.

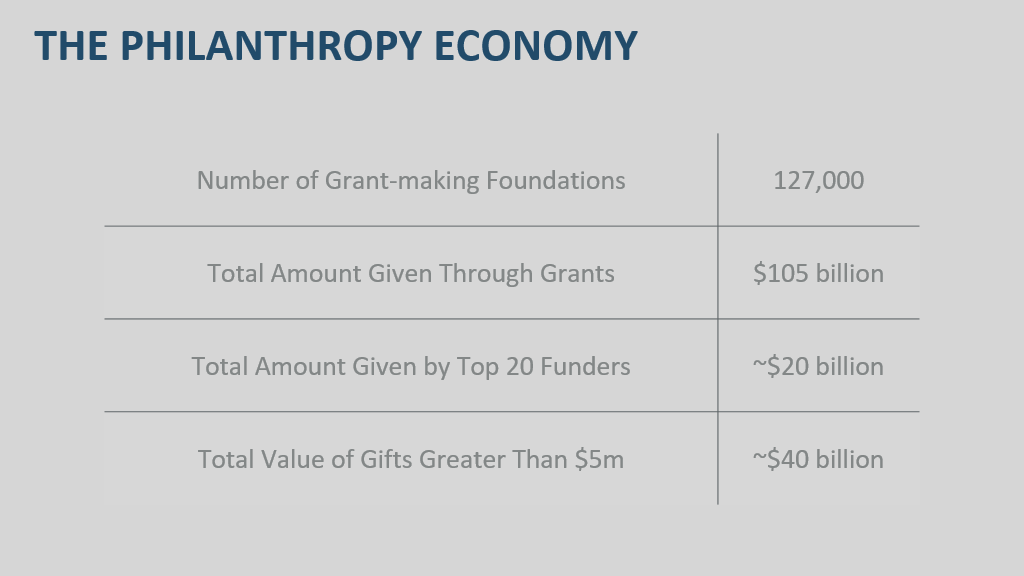

Just know that philanthropy is dominated by large organizations. About a quarter of gifts given out every year in the form of philanthropy—meaning professional foundations—are given away by about 2% of foundations. There’s a huge concentration of wealth in the philanthropic sector.

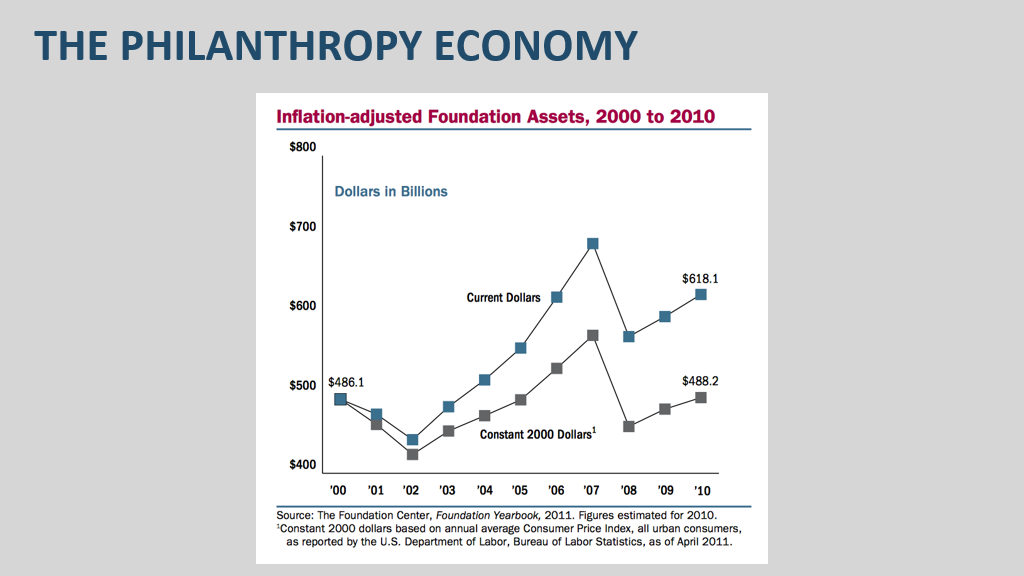

This chart shows how much philanthropic capital can swing based on economic changes. During the 2008 crisis, many foundations and charities saw their endowments shrink by 30%. That’s a huge change.

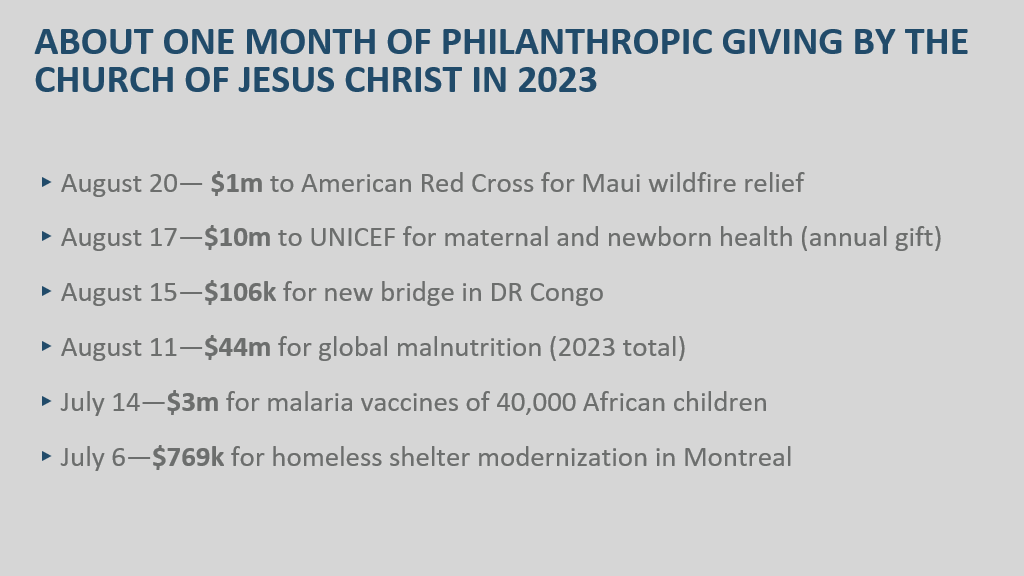

Here’s a list of philanthropic giving by the Church, just spanning a two-month period. This is based on scanning the Church Newsroom, so it doesn’t include all Church philanthropy, but it’s an example of the kind of work the Church is doing. If you go on the Newsroom now, you can’t scroll more than a few articles without reading about some philanthropic endeavor the Church is engaged in somewhere in the world.

And like I said, these examples just came from the Church Newsroom.

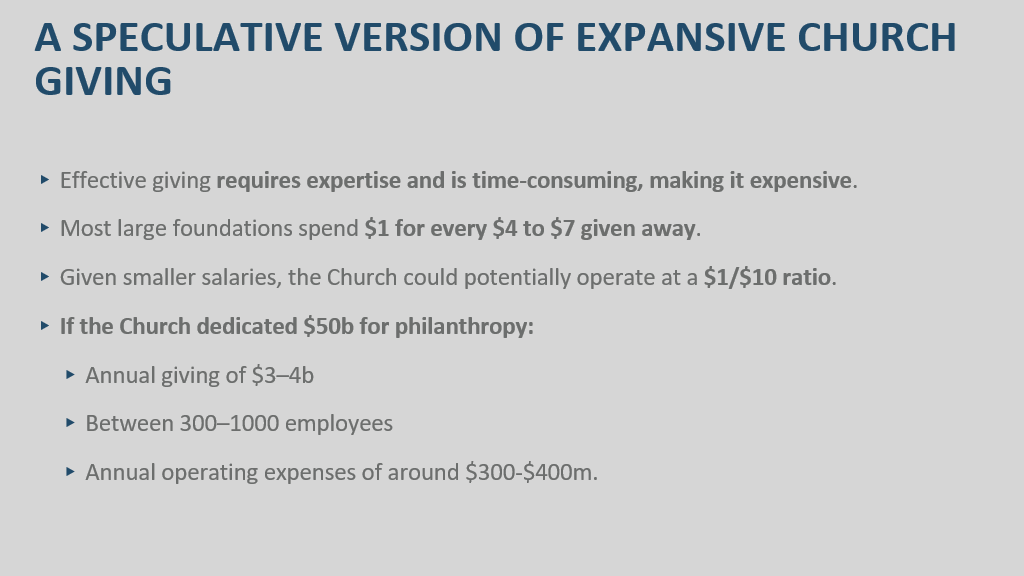

What if the Church stepped up the amount substantially—which they’re in the process of doing? I mean, I’m not saying this as someone with inside knowledge; this is just based on observation. Church humanitarian efforts went from $1 billion to $1.3 billion in just a one-year span. There’s every reason to believe that the Church is accelerating its philanthropic giving. But what if they did? What would it look like?

Well, giving money, despite perception, is actually hard to do well. You can give it foolishly and recklessly and waste a lot of it, but if you want to give it well, it requires expertise. Most large foundations spend a dollar on staff and other expenses for every $4 to $7 they give away. That’s how expensive it can be to give money away well.

Given smaller salaries—which you’d expect because that’s a pattern in how the Church operates—you could expect something like a $1 to $10 ratio. For example, if the Church took $50 billion and said, “We’re dedicating this to philanthropy,” it would mean annual giving of around $3 to $4 billion. It would probably require 300 to about 1,000 employees to do it well, and the annual operating expenses would be around $300 million just to give the money away.

This is how professional philanthropy works, and this is how to do it well. If the Church wanted to give away this much money, you would expect them to employ more people. Anecdotally, I can say they’re already involving more people in their charitable or philanthropic giving right now.

Key Conclusions

- The Church’s financial history is one of constant change.

- We know less than we think we do about Church finances, so don’t be too confident.

- There’s no compelling evidence that the Church violated federal tax law.

- The SEC settlement concluded the Church violated the law—you should not assume it’s the whole story.

- The Church today is unlike anything in the world, so comparisons are never going to be totally fitting.

- The Church is rapidly increasing its philanthropic activity, just by observation.

Why I Pay Tithing

I’ll tell this story very briefly.

When my wife and I were first married, we had our son, Luke, who was a pretty skinny baby. Then we had our son, Seth, who was a very chubby baby, and none of the hand-me-down clothes fit him well. We were poor college students—I was in grad school—and my wife prayed that we would come up with some extra money so she could buy some warm clothes for our son.

She just wanted a pair of jeans that would fit our chubby little baby, Seth. She prayed for that for a while. Then one day, we had neighbors show up. This family had the first grandson on both sides of the family, and this little boy had been showered with gifts from loving grandparents. These friends of ours brought over three garbage bags full of brand-new clothing. My wife opened the first garbage bag, and right on top was the pair of jeans she had been hoping to buy for our son.

This is why I pay tithing. It’s a covenant I made with God. It’s a covenant I’ve made to show Him gratitude and to honor this relationship.

It’s a commandment, and that’s why I pay tithing. I trust that the Lord knows what He’s doing with all this money. And I’ll be clear—it’s a lot—but I trust that.

And that’s why I pay tithing.

So, I’ll leave that with you, and if you have questions or if you have loved ones who have questions about any of this stuff, I’m very happy to answer them. My email address is [email protected]. I can be found pretty easily online, and don’t hesitate to reach out. I’ve fielded questions over the last couple of years on this topic.

So, thank you, everybody.

TOPICS

Church Financial s

Tithing