Being Here Together

I’m so glad to be with you today and glad to be part of this conference. I love the work that fair does. I’m glad to be associated in any way, and I’m very happy to be talking to you about studying the Old Testament.

I think there is so much more power and richness and depth to get out of this book than any of us are getting — that we’re just scratching the surface, that it’s just beautiful what it can offer to us. And so I want to spend my time with you today to help us get even more out of it. To help me get more out of it and to help you get more out of it.

The Painting and the Story of the Old Testament

The Painting and the Story of the Old Testament

I love this painting from the Sistine chapel because, in some ways, it is the story of the Old Testament. It is God reaching after us, yearning to be with us, just reaching. And we are fairly mixed in our feelings about reaching back to him.

So he will plead with us again and again: turn (or return) to me. And we will kind of lazily reach forth our hands. In many ways, that is the story of the Old Testament.

It’s also sadly often the story of our interaction with the Old Testament. I think that some of us love it, some of us are afraid of it. None of us love it as much as we should. None of us are getting as much out of it as we should. And all of us are sometimes as Adam in this picture —

“Oh, if you can reach me through the Old Testament God, then go ahead and do it. But I’m not going to put a lot of effort into it.”

We’re just going to do better this year. There’s so much to get out of this.

Interpretive Lenses

Interpretive Lenses

Today, I’m going to talk about how we bring interpretive lenses with us that sometimes distort the way we can see and understand the Old Testament — and how we need to instead put on different interpretive lenses.

I’m sure we have a couple that are okay. Probably not most of the lenses we bring. There may be some that are okay, but in the end, we’re going to need to put on some very specific interpretive lenses. And it’s not enough to just take off the lenses that we have; we have to put on some other ones.

So, my glasses are currently dirty and I need a new prescription. I’ll be going in a few hours to get a new prescription. But that doesn’t do me enough to just take these off. If I just take these off, then yes, I’m not seeing it with the wrong prescription, but I’m not seeing it very clearly either.

So, we’ll need to put on our interpretive lenses — our correct interpretive lenses.

Incorrect Lenses and Obstacles

Incorrect Lenses and Obstacles

Let’s look at some of the incorrect lenses or the things that are obstacles for us in our day — things that make understanding the Old Testament hard.

The obvious one is time. There is a tremendous amount of time that has gone past between when the stories of the Old Testament and the writings of the Old Testament happened and our day. That means that we know less than we would like about some of the peripheral information that helps us understand it.

So, in contrast, as we’ve just been finishing in Come, Follow Me — our course of study, the Doctrine and Covenants — the amount of resources available to us to understand all sorts of things going on around the period and the place of any revelation… there’s just a vast and wonderful amount available to us. And in comparison with the Old Testament, there’s hardly anything.

So that time is a real obstacle for us.

History as a Lens

And that, of course, leads to some of these other things. We know some of the history that helps us understand the Old Testament — and we’re going to talk about how that history does help us. But there’s so much that we don’t understand.

But we also often just fail to take advantage of the history that we have. Both the history and the way it’s presented in the Bible — I think very often I find people will look at a story they know more in the Bible, but they just look at that story in isolation and they don’t bring in what happens later to understand the big picture. So we’re going to talk about that a lot.

And then sometimes there’s just history outside of the Bible — we learn from the Assyrians or the Babylonians and the Egyptians and so on — that we just don’t bring into play when we could. History we learn from archaeology and so on and so on.

Geography and Culture

The geography is also sometimes an obstacle for us. If we’re not familiar with it, then there’s less that we can learn. So that’s a lens we need to put on.

The culture is a really big element here. I’ll just use an example.

We live — many of us, probably most of us that have access to this lecture — live in a really sterilized world. Most of us don’t go and kill the food that we’re eating. We haven’t — most of us — participated in wars. We haven’t had people attack our homes.

That’s not the case for the peoples in the Old Testament. They defended themselves. They had to defend themselves. Most of them had experienced some kind of violence and participated in some kind of small or large-scale war or defense. Most of them were killing animals. They were familiar with blood. They were familiar with death and with a kind of violence in a way that we are not.

And that cultural gap sometimes becomes shocking and surprising to us — and we need to learn to put ourselves in their place. That’s going to be really big.

Ways of Thinking

Finally, there’s just a way of thinking. I’ll come back to this when we talk about symbolism, but let me just say that we often have a specific, very Western, very modern, very post-scientific-revolution way of thinking that is different than the way they thought.

And sometimes that prevents us from seeing what they’re saying. Sometimes I think they actually understand better than we do, and we ignore that because we aren’t giving them credit or we’re so sure we’re right and so on — and we’ve just changed the way we’re thinking.

So we are going to try and look at the lenses that we need to take off and what lenses we replace them with.

The Latter-day Saint Lens

The Latter-day Saint Lens

Let’s also be clear that as members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, we have a very specific interpretive lens that we often do — maybe not as much as we could — but we often apply to the scriptures.

And that is the lens not only of Christianity, but of restored Christianity.

We are so fortunate to have texts like the book of Moses, which is the Joseph Smith translation of the first part of Genesis, and the book of Abraham, where we can see that Christ and God’s gospel have been here from the very beginning — from the days of Adam this was taught — and that should change the way we understand the Old Testament.

Doesn’t mean that they always understood it. I would guess that often — well, it seems that they’re in varying states of apostasy at any given time — and so they don’t necessarily have the same understanding that we do throughout most of their history.

But there are kernels of it. And to know that God had done it changes the way we understand God and his interactions with his children.

Available Resources

Available Resources

So with all of that in mind, let’s also just give you an idea of some resources that are available. You’ll be familiar with lots of others. These are just some that you may not be familiar with that I’ve helped put together. One is outofthedust.org . A very ugly website because I’m not a web developer, but I finally decided I need to be able to change things myself. So, all sorts of information on there … not presented prettily.

My podcast, The Scriptures Are Real, is one place. Of course, there are tons of podcasts that will be helpful for you. This is one you may not be familiar with that I hope would be helpful as we study the Old Testament.

And there are dozens and dozens of publications out there. This is my latest one, Inspirations and Insights from the Old Testament. But there are lots more coming out this year and lots of old ones that are fantastic. I would encourage you to avail yourself of all of the opportunities that you can find that are helpful for you and that you have time for.

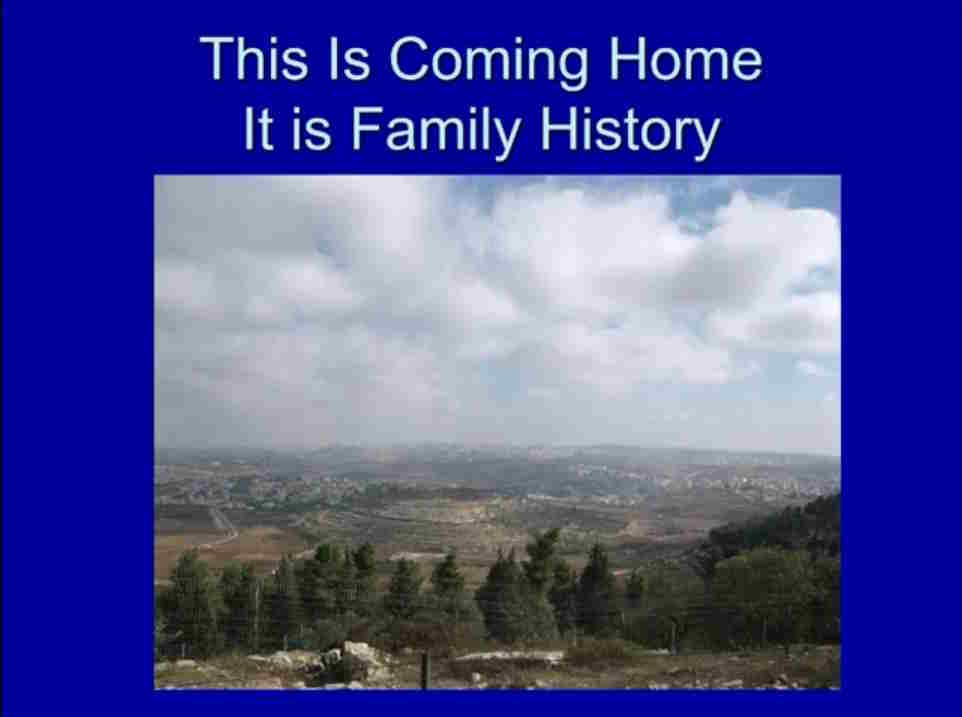

The Interpretive Lens of Family History

The Interpretive Lens of Family History

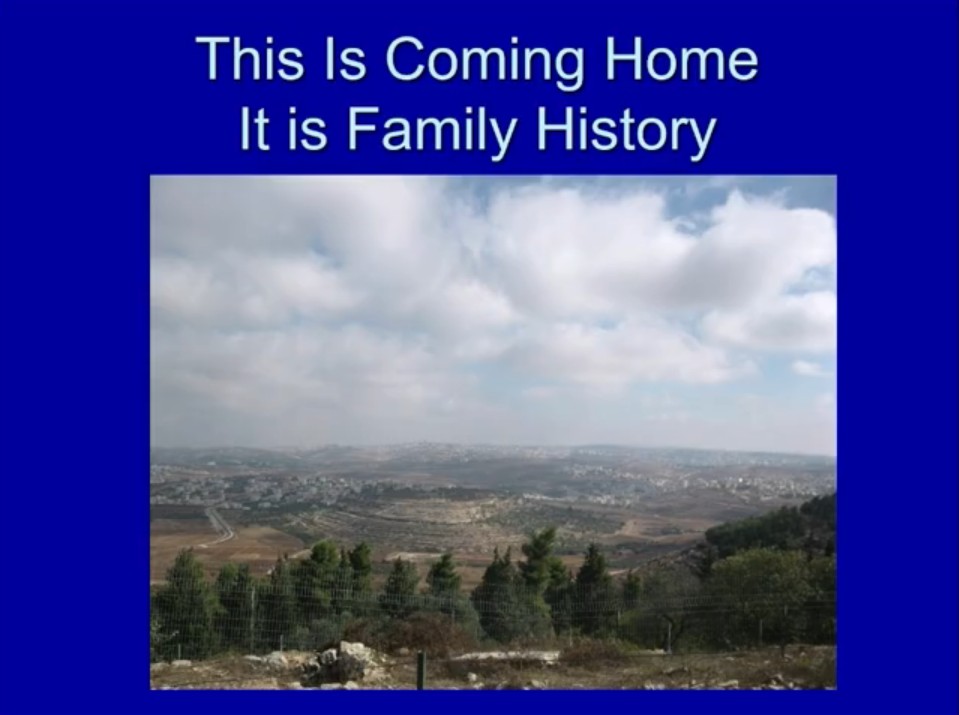

So, let’s start out with this interpretive lens. I hope we think of the Old Testament as family history.

The picture you’re looking at here is a picture taken from Nebi Samuel looking out over Gibian. And then the far horizon, you’re looking at the hills of Ephraim. So this is taken from in the middle, or kind of the edge, of the territory of Benjamin and it’s looking at the territory of Ephraim. And beyond that there are of course lots of other tribes in their lands of inheritance.

Most of us should identify — well, everyone should identify — with the house of Israel, whether by adoption or literally descended. Once we make a covenant we are of the house of Israel and this is our family history.

You are in that picture looking at your homeland, and that should affect you in some way. You should start to recognize and realize that when you think of family history, you shouldn’t just think of great great grandma Mildred, but also great great great grandma Sarah and Rebecca and Rachel and so on.

This is our story. And it changes the way we read it when we think of it that way. It suddenly becomes less foreign territory and other and someone else, and it becomes something that belongs to us and we start to identify more. Thinking of it this way, putting on that lens, will be a big part of your unlocking the Old Testament.

The Whole Story

The Whole Story

I also want to emphasize that the Old Testament gives us the whole story. That’s something — instead of the little teeny story that you can see in the lower picture — it gives us the big whole story.

And by that I mean a number of things. So, we’re going to look at some of the things I mean by that as we go along. Some of it will be the whole story of who God is — we’re going to address that in just a moment. The whole story of how he works with his children.

But I also mean that it gives us the whole story warts and all. Now, this isn’t a picture of warts, but this is of a splash from lots of different angles.

The Old Testament does not give us the sanitized story. In contrast, while the Book of Mormon is the most correct book on earth, a wonderful book of scripture, it’s intentionally sometimes sanitized. Mormon even tells us he’s sanitizing it, that he doesn’t want to put some of these things before us.

So, we don’t necessarily get the pictures of both the good and the bad things that some of our great leaders did. In some cases, you do. We know about Alma the Younger. We know about the sons of Mosiah and some of the mistakes they made.

But the Old Testament is very consistent in telling you the great things and the bad things — the triumphs and the struggles that people went through. Not unlike the Doctrine and Covenants in that it consistently tells us when Joseph needs to repent. But the Old Testament is particularly good at painting that for us.

Embracing Messy Stories

Embracing Messy Stories

And we need to embrace that rather than say, “Whoa, I don’t know… that’s kind of iffy about Jacob,” or something along those lines. We should say, “Ah, look at the struggles Jacob is having. Look at the struggles Abraham is having. Look at the struggles Eli is having. Samson, David — look at their struggles,” and be able to recognize that good people still have struggles.

Sometimes good people don’t succeed because they give in to their vices too much, as in the case of Samson. But we can look at the stories and recognize that they are like us in that life is messy — and in the middle of messiness, people can come to God.

It’s a beautiful part of the Old Testament.

The Whole Story of Who God Is

The Whole Story of Who God Is

But I want to spend my first little while emphasizing the whole story of who God is. And again, we have a very unique perspective on this as members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

When I teach — and I’m teaching right now the Pearl of Great Price — and we usually start out with Moses 1 after giving them some history of how we got the book… and it’s very, very rare that it’s not the case where the first question I get from students is: Who is speaking here?

Because we understand it to be Jehovah, and we understand Jehovah to be Jesus Christ, and yet he’s speaking about Jesus Christ as his son — and that confuses my students sometimes.

So I hope that we can start to think about that. This is Jehovah that we’re reading about, and we should think of Jehovah in a very specific way, especially in the Old Testament.

Jehovah Acting for the Father

It will be a little bit different post-resurrection in the Doctrine and Covenants era, but in the Old Testament there’s a very specific way to think of Jehovah. This is Jesus Christ acting for and in behalf of the Father.

We call it divine investiture of authority. It’s a principle I’m sure you’re familiar with. They were even more familiar with it in the ancient world — so that we get representatives from one kingdom coming to another speaking as if they are the king of the other country. No one thinks they are, but they treat them as if they are, because that’s the way that you do business. You invest someone else to act on your behalf.

After the Fall — we are so cut off from the presence of God that he does not interact with us directly, but rather interacts with us through an intermediary. We interact with him, including even our prayers, through an intermediary.

And the intermediary is Jesus Christ, who speaks as if he is the Father because that’s what he’s been asked to do. His role is to act for and in behalf of God.

How to Read the Old Testament with This Lens

How to Read the Old Testament with This Lens

So we will understand this best if we are reading it as if it is God the Father, knowing in the back of our minds that it’s Jehovah, his Son Jesus Christ, representing him to us.

And that’s one of the things that we need to stop and think about: Who is Jehovah really? This is Christ, whose primary job is to reveal the Father to us — either by eventually bringing us into the Father’s presence, but in the interim (and this is what he talks about more than anything else in the Gospels, especially in the book of John) — that he reveals the Father to us by doing what the Father would do, saying what the Father would say, acting the way the Father would act, and so on.

We learn about the nature of our Father by seeing the nature of Jehovah, who is acting so much like the Father that we can learn about the Father by watching him.

Keeping Both Christ and the Father in View

And so it is intended that you think of the Father as we think of Jehovah. Good to know it’s Jesus Christ — that’s also helpful, and it helps us understand who he is and his role as a redeemer.

But he wants to reveal the Father to us and act as the Father. And he wants us to be thinking of the Father. If we think of that — also thinking of Christ. I don’t want to take Christ out of this picture. Please don’t take me wrong. Also thinking of Christ.

But let’s not take the Father out of the picture, because that’s not what Christ tells us to do. Let’s put the Father in the picture.

This is Jehovah, or Christ, acting for and in behalf of the Father.

What Is Jehovah Like?

What Is Jehovah Like?

So then we come to the question, what is Jehovah like? And this is useful. We want to know both what the father is like and what the son is like. And as we learn about one, we learn about the other.

So what do we learn about his nature? The old testament will teach us a tremendous amount. And again, we should put our restoration interpretive lenses on as we do this.

The Restoration Teaches Us

The Restoration Teaches Us

What does the restoration teach us? Especially using the Joseph Smith translation of the Bible and especially in the book of Moses, the book of Abraham and so on.

There are a couple of really key elements. So, let’s look at this and I think we’ll find that many of the problems that many Christians have with the nature of God are resolved with restoration scripture in place.

Wrath and Weeping in Moses 7

Wrath and Weeping in Moses 7

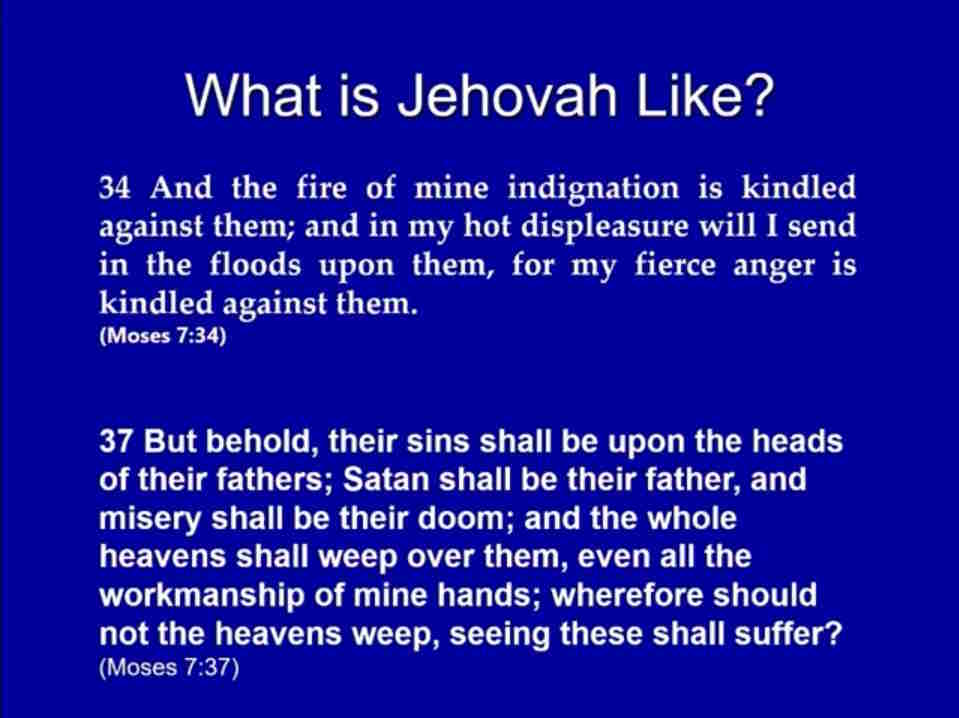

So, we are going to read from Moses 7:34. This is a vision to Enoch about the flood. And it reads, “And the fire of mine indignation is kindled against them, and in my hot displeasure will I send in the floods upon them, for my fierce anger is kindled against them.”

That’s pretty wrathy, right? That’s about as wrathy as it gets. This is an upset God. Now, we we’re going to come back to the idea of an angry or an upset God. But part of the way we can understand that is by reading just a few verses later where he says, “But behold, there meaning the people in those day, their sins shall be upon the heads of their fathers. Satan shall be their father, and misery shall be their doom, and the whole heaven shall weep over them, even all the workmanship of mine hands. Wherefore should not the heavens weep, seeing thee shall suffer?”

We see that at the same time God is experiencing both anger and sorrow over the misery, the suffering of his children — both the suffering they are bringing upon themselves and the suffering he will have to bring upon them as he brings the floods upon them.

That helps us understand who God is. God is someone — his anger will be a tool. His punishments will be a tool to bring his children back to him. And we’re going to look at that as we start talking more about looking at the whole story.

Letting God Tell Us What He Is Like

Let us be clear about this. I have had a lot of students who are uncomfortable as they read the Old Testament. They’ll read Isaiah who testifies so beautifully of Christ, but then they’ll read Isaiah saying that God is angry and upset and full of wrath and they’ll say, that’s not God.

I think this is God telling us what he looks like. So this is one of the interpretive lenses we have to deal with. That is a difficulty for us. We often do not allow God to tell us what he is like. So, we’re going to address that further in a moment.

In any case, when he presents himself to us, he does have both anger. We’ll find a key passage in Jeremiah where he says he holds anger and is merciful. And I think that’s an important distinction.

Divine Anger Versus Human Anger

But I’ve come to conclude that his anger is not like my anger. As a being who has a fallen nature, I don’t think I’m capable of feeling the kind of anger that God does. There’s always a fallen nature and an element in it that’s not appropriate for me. That’s at least me. Maybe others are different, but that’s me.

I have to just believe and have faith that a divine being has a different kind of anger and that it is always associated with love and bringing his children where they need to be. And you see that mixture when we have these two verses, or really this whole brick or set of passages together. In the book of Moses — especially in chapter 7 — we start to see that Jehovah is someone who loves his children and also will have to save his children sometimes by removing their oppressors and sometimes by punishing them.

We will return to that idea. But let’s keep in mind we are learning about the nature of Jehovah by reading the Old Testament and especially by reading restoration passages in the Old Testament.

A Latter-day Revelation that Illuminates the Old Testament

A Latter-day Revelation that Illuminates the Old Testament

Let’s read a revelation that also comes forth in these latter days that I think will help us understand so many stories in the Old Testament.

“Verily I say unto you concerning your brethren who have been afflicted,”

This is God talking about those who are in Missouri and the terrible things they’re going through.

“and persecuted and cast out from the land of their inheritance. I the Lord have suffered the affliction to come upon them wherewith they have been afflicted in consequence of their transgressions. Yet I will own them and they shall be mine in that day –”

I want you to remember that language. We’ll come back to that language.

“…in that day when I shall come to make up my jewels, therefore they must needs be chastened and tried even as Abraham who was commanded to offer up his only son.”

I will skip a few verses for the sake of time back in verse 7 of section 101.

“They were slow to hearken unto the voice of the Lord their God. Therefore the Lord their God is slow to hearken unto their prayers to answer them in the day of their trouble. In the day of their peace, they esteemed lightly my counsel; but in the day of their trouble of necessity, they feel after me. Verily, I say unto you, notwithstanding their sins, my bowels are filled with compassion towards them. I will not utterly cast them off, and in the day of wrath, I will remember mercy.”

You could apply that to every story in the Old Testament. I find that same sentiment expressed in different ways again and again and again. The Doctrine and Covenants has language that just resonates more with us in our modern times. I hope that reading it in language that we’re more familiar with helps us recognize what Jehovah is doing in the Old Testament and what his motives are and his nature and character.

What Do You Expect God to Be Like?

What Do You Expect God to Be Like?

Let’s continue by asking a couple of other questions. What do you expect God to be like? Think about that. Take a second to think about it. What do you expect God to be like?

And then, does this put blinders on us? Right? Like a horse has blinders. Does it make it so there are certain things we just won’t see?

I’ve had this experience again and again. Like I said, students who have said, “This can’t be Jehovah. That’s not what he’s like.” I’ve had that in the New Testament — “That can’t be Christ. That’s not the way he talks.”

I have read countless times, even in church publications, official church publications, where someone said, “This is how Christ did things,” and then they talk about things that he didn’t do. Or they say, “Christ always teaches this way,” and then they start talking about a certain principle, and I think, “I can think of dozens of times he taught a different way.”

We often think, ‘this is what Christ should be like’, and we read that into the text — and then when it’s not what we find, we want to turn a blind eye to it. But then that starts to color the way we see everything. And soon there are certain things we just can’t see correctly because we are trying to find God behaving and speaking the way we think he should behave or speak.

Letting God Present Himself

I think it is far better to let God present himself to us the way he wants to present himself to us. Read the scriptures without blinders, without lenses that color it, without your expectations, and find out what is actually in there. Then ask yourself, why does God want me to see him this way?

And when we do that, we will find that God is more magnificent, more powerful, and more loving and merciful than we have expected. Just not always in the ways that we expect. We often limit him.

In fact, I think we sometimes give ourselves a whitewashed God. We create God in our image or in the image we would like him to be rather than him creating us in his image and then telling us what he is actually like.

This is something we struggle with. And so I hope you will start to look at

- how does God present himself,

- and what does it mean?

Jehovah as Divine Warrior and Comforter

Jehovah as Divine Warrior and Comforter

This is in particular — I think it’s well portrayed in a couple of chapters in Isaiah. If we were to look at Isaiah chapter 25 and 27, in chapter 27 he describes himself as having a great and terrible sword and he is fighting Leviathan, the chaos monster. All that represents all that Satan would have undone in God’s creation to make everything terrible and and and miserable for us. He fights that with a great and terrible sword.

But interestingly, just two chapters before in chapter 25, he describes himself as wiping away all of our tears.

I find that my students aren’t comfortable with Jehovah being described as having a great sword. He is frequently in the Old Testament described as a man of war or the divine warrior in one way or another. That’s a phrase we use, but in one way or another, he’s described as a divine warrior. And my students and many of my audience don’t like that. We don’t want God to be a warrior. We want him to be someone who is just wiping away tears.

But I would say that it’s important for us to understand that Christ has the ability to deliver us. Why can he deliver us? Because he is a divine warrior. He fights in different ways. One of the ways he fought for us was by suffering all of our sins and thus conquering death. But he will also fight for us by removing oppressors.

And that’s a main theme in Isaiah, especially the last part of Isaiah:

- He will remove those who oppress.

- He first pleads and then if they don’t stop oppressing,

- he removes the oppressors. He punishes them.

That’s why he can deliver us.

The Sword and the Hand That Wipes Away Tears

The reason that Christ can reach out with one hand and wipe away our tears is because in the other hand he holds a great and terrible and a mighty sword. And it’s important for us to recognize this.

I will just say that in my experience as a bishop — as I do temple recommends and we’ve been encouraged recently to be asking some more questions to help the youth bear testimony and everyone to bear testimony to us and so on — I have for quite some time asked all the youth who come to me, when we ask about their faith in Christ as a savior and redeemer, what it means for him to be a savior.

And after having done this with youth in my ward, now I ask all sorts of young single adults and all sorts of people everywhere, what does it mean that Christ is your savior? The most common answer is: he is my friend. He is there for me. Those are good and those are important.

But that’s not what a savior is. A savior is someone who saves you from whatever is trying to conquer you. And he can do that only by conquering whatever it is that is trying to conquer you.

And if we don’t recognize Christ’s ability to be victorious — his ability to conquer, his supremacy as the divine warrior — then we cannot have faith that he can deliver us from everything that we need to be delivered from. I think that’s going to induce a lot more anxiousness, a lot more fear, because we won’t understand how much Jehovah, Jesus Christ sent on behalf of the father, can deliver us.

That’s a lens we need to put on as we study the Old Testament.

Seeing the Whole Story

Seeing the Whole Story

Again, I want to encourage us to see the whole story — to see the big picture, not just a little part of it. We will often take a story and isolate it or isolate a part of a story and not read the whole thing.

I’m going to give you some examples of what I’m talking about. But let’s first of all remember the age-old idea of people trying to figure out what an elephant looks like. Blind men trying to figure out what an elephant looks like. And all they can do is feel part of the elephant. And each one will think that the elephant is like this or that. But it’s only when we can see the whole story that we will understand it.

The Old Testament helps us see the whole story. But we should not read the Old Testament in isolation. We should read it in conjunction with the restoration as well.

The Story of the Ark — A Big Picture View

The Story of the Ark — A Big Picture View

So, let’s think about, for example, the story of the ark. We know the world is wicked. I won’t spend the time here to go through all the evidence about how they’re the most wicked people on earth. They’re thinking of only evil continually and they’re without affection and hate their own blood and all that that picture paints.

So, then God removes… and so let’s put it this way — they are all oppressing each other. The whole earth was filled with violence is another phrase. They are all oppressing each other. There’s no opportunity for truth, for freedom, for a lack of oppression, for moving forward righteously.

And so God will remove all those oppressors in this horrific story called the flood where eight souls will survive and everyone else will not. That is devastating. We are grateful for the eight souls that survived and that humanity can continue in that way and that we can be descended from those eight souls. But it’s devastating to think of all those who died.

But we should not think that that’s the end of the story. We get a little bit in the New Testament and even more through revelations from Joseph Smith where we learn that Jesus Christ specifically went to those souls in the spirit world — to the souls who died during the flood — and brought the gospel to them and organized the gospel being taught to them.

That tells us that as terrible and as wicked as they were and as much as God had to remove them from this part of the story, it wasn’t the end of the story. They still had another chance.

It was as it were — since he could not get them to behave there, he sent them to their room for several thousand years and then went and talked to them and tried to get them to do better.

We need to remember that the story doesn’t end even with death. And so often death happens in the Old Testament and it seems so shocking to us and we forget that for God it’s moving us from one room to another — from one part of what we’re doing to another part of what we’re doing — where he can work with us again, work with us some more.

Looking at the End of the Story

That’s an important part to remember. So we’re talking — that’s a very big picture story. It’s small stories as well. We need to remember to look at the end of the story.

But let us not forget how much this continues on the other side of the veil and how much God continues to work with those — even those whom he has killed. That sounds shocking to us that he does that. But think celestial! Recognize that God, when it seems to be what will be best for the individuals and for the group, will bring them from this life to the next. It’s like he’s ‘sent them to their room’ and He will work with them again.

That’s one example of looking at the big picture.

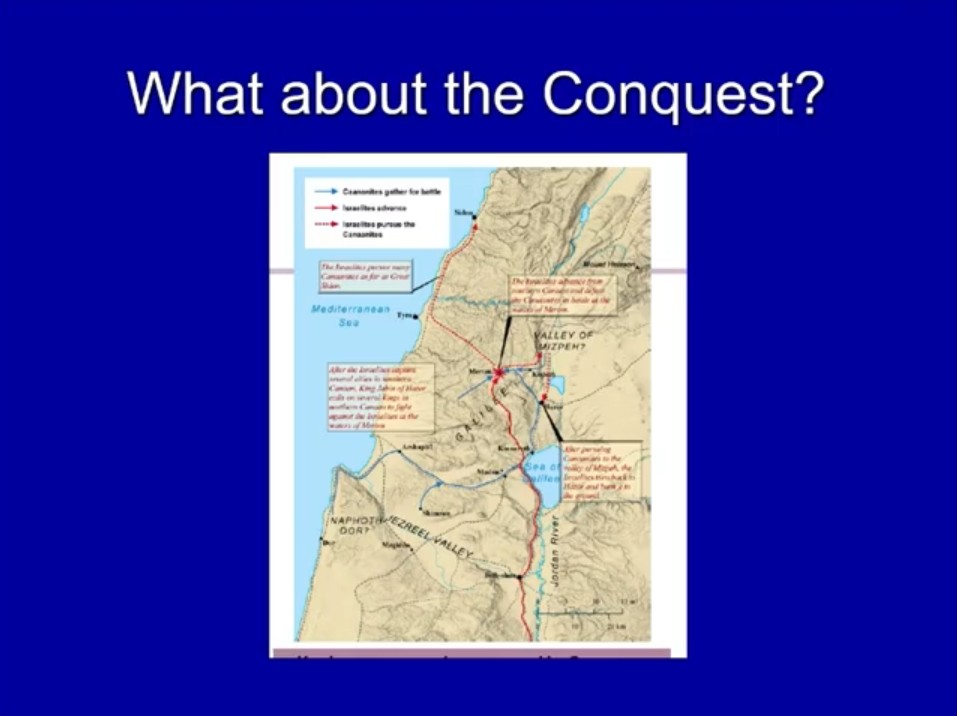

Understanding the Conquest Through the Lens of the Whole Story

Understanding the Conquest Through the Lens of the Whole Story

This can help us understand the conquest — another time of tremendous violence where whole nations are to be destroyed. Again, we know that they were wicked. We only know this — we know it a little bit from the Bible. We know it a lot from a very simple verse in 1 Nephi 17 where Nephi tells us that they’d rejected every word that had been preached to them.

That tells us that God had been preaching to them and they’d rejected it. They’d become wicked and so they are removed. And while we do not have the story of Christ going to them in the spirit world, I am sure that they had another chance – just like they did in the story of the flood.

Let’s not forget the end of the story. Let’s look at the whole story.

The Story of Hosea and Gomer

The Story of Hosea and Gomer

We’re going to look at a couple of other examples of that later. Let’s look at this one, the story of Hosea and Gomer, where we know that Gomer is a harlot. It would seem that she is bought out of this — she might have been forced to be a harlot because she is redeemed by Hosea. The timing is not 100% clear on that. But it seems, in my opinion, that he buys her out of slavery where she has been a harlot in slavery. He redeems her and then marries her and she has children with him — and then she plays the harlot again.

And why did she play the harlot again? Because she liked the payments she got as a harlot.

That’s us too often, isn’t it? So, this is another one of our lenses. We’ll talk a little bit more later about symbolism and applying it to ourselves, but that is us too often. God redeems us and then we say, “I kind of like that stuff,” and we go back to our sins like a sow wallowing in the mire.

God Removes Blessings to Bring Us Home

God Removes Blessings to Bring Us Home

So, what happens? God tells Hosea what he will do. He says:

“Therefore will I return and take away my corn in the time thereof, and my wine in the season thereof, and will recover my wool and my flax given to cover her nakedness. I will also cause all her mirth to cease.”

She’s not going to be happy anymore.

“And I will destroy her vines and her fig trees whereof sheath has said, ‘These are rewards that my lovers have given me.'”

In other words, God says, “Well, if she’s going to play the harlot and she’s doing it because she likes this stuff and she thinks that it makes her life exciting or fun or something like that, I’m going to take away all of it. She won’t get the stuff. She’s not going to have the excitement and the fun. I’m going to make her life miserable.”

And then he says very specifically — “so that she will recognize how good it was when she was with you, Hosea, and will come back to you.”

Israel as the Unfaithful Spouse

Israel as the Unfaithful Spouse

And then he compares that to the house of Israel. And he says:

“It shall come to pass that in that day I will hear, saith the Lord, I will hear the heavens, and they shall hear the earth, and the earth shall hear the corn and the wine and the oil, and they shall hold Jezreel, “

(That’s a fertile valley there that he said was going to be taken away.)

“And I will sow her unto me in the earth, and I will have mercy upon her that had not obtained mercy. And I will say to them which were not my people, thou art my people. And they shall say, Thou art my God.”

You see, he’s punishing Gomer — and by extension Israel, he’s allegorizing that story to Israel — and saying,

“I will punish Israel, but it’s only so that they will realize that they need to come back to me. And I will let them come back. I will plead with them to come back and accept them back and say, ‘You are my people,’ and you can say that I am your God.”

That’s the end of that story, right? It doesn’t end at the punishment phase. It ends at the ‘come back’ phase.

We’re going to see that is the story of the Old Testament.

Return Unto Me — The Most Repeated Plea

Return Unto Me — The Most Repeated Plea

In Isaiah chapter 55, we read:

“Let the wicked forsake his way, and let the unrighteous man his thoughts, and let him return unto the Lord, and he will have mercy upon him; and to our God, for he will abundantly pardon.”

Beautiful phrases. Beautiful phrases.

And this is the plea we find more than any other plea in the Old Testament. Return unto me or return unto the Lord. He just pleads with us again and again and again.

The Marriage Covenant in Ezekiel

In Ezekiel — and this is my own translation, just a couple differences here than what you’ll read in the King James Version — but:

“Now when I passed by thee and looked upon thee, behold, thy time was in the time of love, and I spread my wing over thee and covered thy nakedness. Yea, I swear unto thee and entered into a covenant with thee, saith the Lord God, and you became mine.”

That’s the God that will keep working with us. If we read the whole story, we will read that — after we rebel — it’s still a time of love, a time for him to take us in, and we are his.

God Takes No Pleasure in Punishment

God Takes No Pleasure in Punishment

One last one along these lines. This is from Ezekiel. We read this actually in a couple of places in Ezekiel, but in chapter 18 verse 27 again:

“When the wicked man turneth away from his wickedness that he hath committed, and doeth that which is lawful and right, he shall save his soul alive. Because he considereth and turneth away from all his transgressions that he hath committed, he shall surely live, he shall not die.”

We skip to verse 31, and we see a plea:

“Cast away from you all your transgressions, whereby you have transgressed, and make you a new heart and a new spirit. For why will ye die, oh house of Israel? For I have no pleasure in the death of him that dieth, saith the Lord God. Wherefore turn yourselves, and live ye.”

This is his plea and this is what he’s saying will eventually happen. If we keep reading the book of Ezekiel, this will happen. If we read the whole story, he keeps pleading. He keeps pleading — and eventually he is successful.

That’s the whole story. Let’s not forget that the Lord is always always pleading for us to come back. And that’s how the story will end — is when we do.

“For I am the Lord. I change not. Therefore, ye sons of Jacob are not consumed. Even from the days of your fathers, ye are gone away from mine ordinances and have not kept them. Return unto me and I will return unto you, saith the Lord of hosts.” Malachai 3:6-7

“For I am the Lord. I change not. Therefore, ye sons of Jacob are not consumed. Even from the days of your fathers, ye are gone away from mine ordinances and have not kept them. Return unto me and I will return unto you, saith the Lord of hosts.” Malachai 3:6-7

That’s at the very end of the Old Testament. If we keep reading the whole story, that’s what we’ll see.

An Interpretive Lens: Symbols

An Interpretive Lens: Symbols

Let’s look at another interpretive lens, and that is symbols. We need to recognize that the ancient Israelites were a very symbol-oriented people. They saw the world through symbols.

Now, that’s difficult for us. There is this power in symbols that we remember better. It reaches into our hearts and souls and emotes more with us. It touches our emotions and yields layers of meaning. There are so many reasons that symbols are powerful.

Orson F. Whitney once said that God teaches by symbols. 1) It’s his favorite method of teaching. And I agree with that.

All right. But there is a cultural distance between us and ancient Israel. And this is one of the biggest cultural differences.

Our Legalistic Culture Versus Their Symbolic One

We are in an increasingly legalistic society. We want one thing to mean one thing. That’s how it has to be in a legal document or something along those lines. We don’t want it to be able to be taken in more than one way.

But symbols are intended to be taken in more than one way. So, we don’t want that.

Losing Our Symbol Literacy

We’re also inheritors of a Protestant culture. Protestant culture was divorcing itself from Catholicism. Catholicism had a lot of symbolic actions and rituals within it. And so Protestants increasingly distanced themselves from that. That trajectory continues today so that we understand symbols and symbolic actions less and less and less.

That’s just the place we are culturally now.

I think this presents a huge danger for us because I will say that we—my generation—is less culturally literate than my grandparents’ generation, and my children and younger-than-them generation is less culturally or symbolically literate than I am.

That’s a problem because the gospel is laden with symbols. All of our ordinances have symbols. Most especially the temple, which is full of ordinances that are full of symbols. And the less symbol-literate our youth are, the less comfortable they will be in the temple. The more it will seem odd to them.

I’ve heard youth as they come out of the temple the first time say, “That felt like a cult.” Well, that’s because they are symbol-illiterate.

We need to work at teaching our youth to be symbol-literate. And we’ll have to become symbol literate ourselves to do that. And so we need to start getting better and better at recognizing the power of symbols and looking for symbols and especially symbolic action.

Symbolic Action in Scripture

The scriptures are full of symbols—literary symbols we could say. Especially literary symbols that are talking about symbolic actions, things that God did, things that he had his prophets did, or the way he orchestrated history. Symbolic action is huge.

For example (and we could spend forever on just this one; we’re just going to touch on it lightly) the story of the Exodus. I think it literally happens, but it happens in a way that is designed symbolically to teach us of

- our leaving the world behind,

- coming and making covenants with God, and

- coming into his presence, whether on Mount Sinai or represented by the promised land, which is symbolic of the true promised land, the celestial kingdom.

It’s a real story that is ladened with symbol after symbol after symbol that teaches us about us and our journey to be with God.

Let the Literal Help You See the Symbolic

Again, we want to understand the literal. I’m big on making the scriptures real, but we want to have that help us then to see the symbolism. Not prevent us from seeing the symbolism, but help us to see the symbolism behind what God does.

Let’s use one particular story that I think will help us see both the symbolism and the importance of reading the whole story.

Miriam and Aaron Challenge Moses

Miriam and Aaron Challenge Moses

During the Exodus, there is a time where Aaron and Miriam approach Moses and tell him he’s taken too much upon himself. This is during a time where Israel, like in the days of Joseph Smith, they’ve just been told everyone should be a prophet. Inspiration is flooding forth on everyone. And then there’s some confusion about how does that work and a hierarchy with one person that can speak for God to all of Israel and so on.

During that period of confusion, we had—as we had Hiram Page and others—that’s typical in the restoration as well.

In this era, part of it is when Aaron and Miriam come to Moses and say, “You take too much upon yourself.” And they recognize that they—or they feel like they—should have more power and authority.

Well, what happens?

Symbolic Action: Miriam Is Struck with Leprosy

God is left with a choice. In our day, Moses could give a wonderful sermon, teach everyone correct principles, and we’d all be okay. In their day, if he does that, the fact that they came and challenged him—that’s a symbolic action. And if there’s no corresponding action, then people will see this as there is no answer. They’re right. Moses is wrong.

So there has to be a corresponding action.

So what is that action? Miriam is struck with leprosy. Leprosy makes her ritually impure, ritually unclean. Not actually spiritually, but ritually unclean.

Symbolically, it teaches that when you challenge the authority of God’s prophet, when you don’t accept God’s prophet, you have distanced yourself from God. You can’t approach God when you are not listening to the prophet. That’s a powerful lesson.

It was more important that Miriam be struck with leprosy than that all of Israel should perish and dwindle in unbelief because they didn’t believe the prophet. That principle we’re going to see again and again and again. God will smite someone—teaching through symbolic action what needs to be taught—because that’s more important to save the nation and not have them dwindle in unbelief.

So sometimes an individual will have to perish, as did Laban, right? In the story of Laban and Nephi.

So Miriam is struck with leprosy. That’s an important lesson in and of itself, and often that’s where people stop.

Reading the Whole Story: Mercy and Restoration

But let’s remember the whole story. What happens?

The camp of Israel waits. She is healed. She repents. God heals her. It’s very quick that she’s healed, but there’s a period of uh where she needs to go through to be richly pure. So she goes through that period. It’s a week.

They wait for her. They do not leave Miriam behind. She’s healed. She’s ready to go with them. They wait as long as is necessary. When she can be with them again, they move on.

Think of the symbolism behind that story. If we cut it off at Miriam being struck with leprosy, it seems like a story of a rather capricious god. But when we look at the whole story, we have a God who is willing to teach and also merciful and willing to wait as long as is necessary. Not leave us behind, but bring us with him if we are only willing to come with him.

That’s reading the whole story, and that’s getting something out of the symbolism. And we need to do that and teach others to do that as well.

Another Interpretive Lens: The Covenant

Another Interpretive Lens: The Covenant

Now, we’re going to look at another lens. This is an important one that we could spend several hours on — the lens of the covenant.

If we understand what the covenant is and start looking for covenant language, we will see so many more things happening in the scriptures than we usually do.

So let’s look at this covenant lens. And as we do it, we need to think about how much the covenant is about the family. The Old Testament is a story of families and about how covenants bring families together and are administered through families, trying to make the entire whole world part of God’s family.

But let’s remember that the Old Testament is a story of families from beginning to end. It begins with Adam and Eve and the beginning of their family. We’ve got Abraham and all of the messy difficult things with his family, and Isaac and the messy difficult things with his family, and with Jacob and Esau and then Jacob and the messy things with his family and Joseph and so on and so on.

This is a story of family — the family of Israel, the family of Abraham — but teaching us that it’s always all about family.

So that’s one of the lenses that we need to have on, is the lens that it’s about covenant and family together.

Learning About Families and Covenants

Learning About Families and Covenants

And what can we learn about families? What can we learn about covenants as we read this story of families in the Old Testament?

We’re going to focus in particular on covenants, which as I said is a family affair. And we’re not going to spend long on teaching what the covenant is. We’re just going to barely touch on it so that we can get to the part where we will talk about how to see it in the scriptures.

The Greatest Covenant Obligation

We need to first of all understand our greatest obligation under the covenant, taught to us in Deuteronomy, is to love God with all our heart and with all our soul and with all — it says they — but all our might.

Mind will be put in there when it’s translated into Greek because the word — the might — is a word that’s like all your variedness or your muchness or everything you are. And so they read that not just as strength but mind as well. And that’s a reasonable thing.

But in the end, it’s about loving God. That’s what this is really about.

The Crux of the Covenant: Relationship

The Crux of the Covenant: Relationship

So if that’s our greatest obligation, if there’s something we should learn from that, I think it’s this: we learn what the crux of the covenant is.

The crux of the covenant is relationship.

And I don’t have time to go into all of this, but the more I study the covenant, the more I realize that relationship is the governing principle, and everything else stems from there.

First, it’s about having a relationship with God — loving God, and his loving us.

We also need to recognize why God wants a relationship with us. And it’s because he is our father and he loves us. The whole point of the plan of salvation is to make it so we can have a closer relationship with him by being more like him and allowing us to have the joy that comes from being like him and having that relationship with him.

Bound to God Through Covenant

Bound to God Through Covenant

President Nelson has taught us about this. If we let God prevail in our lives, that covenant will lead us closer and closer to him. All covenants are intended to be binding. They create a relationship with everlasting ties.

This is from Jenet Erickson — we are deeply relational beings designed not for independence but for radical dependence and connection.

Let’s remember that and go back to President Nelson:

“Once you and I have made a covenant with God, our relationship with him becomes much closer than before our covenant. Now we are bound together. Each of us has a special place in God’s heart. He has high hopes for us.”

Think of that. The hopes he has for us and the special place we have in God’s heart because we’re bound together. That’s what the covenant is about.

“Making a covenant with God changes our relationship with him forever. It blesses us with an extra measure of love and mercy. It affects who we are and how God will help us become what we can become.”

That’s beautiful.

Our Covenant Identity

Our Covenant Identity

So, who are we? Well, we know that our primary identity should be that we are:

- a child of God

- a child of the covenant

- and a disciple of Christ.

All those come together in the Old Testament beautifully — so beautifully.

Hesed: Covenant Loyalty, Love, and Mercy

Hesed: Covenant Loyalty, Love, and Mercy

So, this special relationship and special love and mercy he’s talking about — I’m sure you’ve heard of this phrase by now. Hesed — it’s a Hebrew word that denotes a special kind of loyalty and love and mercy available within the covenant.

It’s available because of the closer relationship. It’s not that God doesn’t want to extend this to everyone. He does — he desperately wants to extend it to everyone. And we’re trying to get everyone on both sides of the veil to be part of the covenant so they can have this.

But the fact of the matter is that there are some things that grow out of a deeper relationship. And this is the primary and most important thing that grows out of that deeper relationship.

Isaiah speaks about it this way on behalf of God:

Isaiah speaks about it this way on behalf of God:

“For the mountains shall depart and the hills be removed, but my kindness shall not depart from thee; neither shall the covenant of my peace be removed from thee, saith the Lord that hath mercy on thee.”

He is telling us it is more likely that the mountains pack up and leave than that he will stop having hesed — covenant loyalty and mercy — on us.

God’s Everlasting Covenant Love

We can read about this in Jeremiah where he says:

“Yea, I have loved thee with an everlasting love: therefore with lovingkindness have I drawn thee.”

President Nelson says hesed is:

“a special kind of love and mercy that God feels for and extends to those who have made a covenant with him and we reciprocate with for him.”

That’s beautiful, isn’t it? That’s about the relationship.

Marriage as a Symbol of the Covenant Relationship

Marriage as a Symbol of the Covenant Relationship

Marriage is one of those symbolic things. It’s real — marriage is important and real — but symbolically it teaches us about our covenant relationship with God.

And you think about how within the kind of relationship you create in marriage, there is bound to be greater love and loyalty than outside of that kind of relationship. That’s what happens in a covenant relationship with God.

The Second Great Covenant Obligation

The Second Great Covenant Obligation

Now, our second great covenantal obligation is to love our neighbor as ourselves. That is also about relationship.

You can see how much the covenant is about relationship. When you remember that and read the Old Testament with this lens — that God is trying to help us have a relationship with him and with each other and that it’s always about deepening a loving relationship with him and with each other — that’s the point of everything that’s going on in the Old Testament.

Then you’ll start to see some different things.

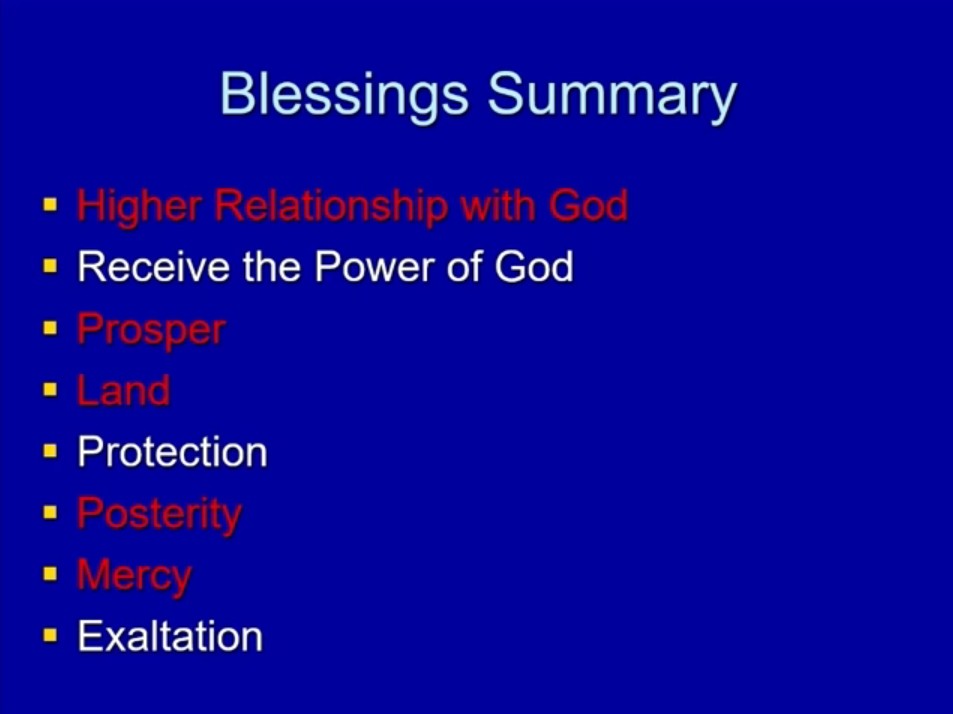

A High-Level Summary of Covenant Blessings

A High-Level Summary of Covenant Blessings

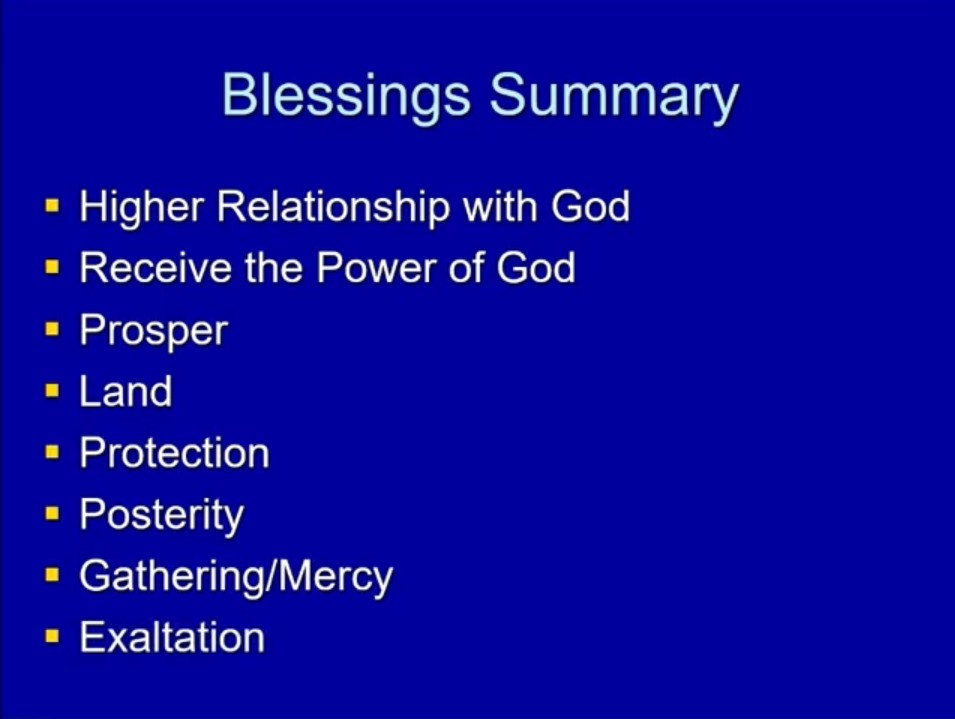

Now, let’s look very quickly — if we were to summarize on a high-level view — what the blessings of the covenant are. That’s important for us if we’re going to start to see the covenant in the Old Testament.

The blessings are:

- to have a higher relationship with God

- to receive God’s power as a result of that

- which allows us to prosper

- and then we need a place to prosper

- so there’s a land to prosper in

- once we’re prospering, people want to take it from us

- so he will protect us

- and then we can support having huge posterity

- and then he will gather us to him in mercy

- and eventually exalt us

That’s the high-level view of the blessings that are promised in the covenant.

Seeing the Covenant Everywhere

So now we want to learn to recognize that covenant in the scriptures. And when we have that lens on — when we’re looking for those things in the scriptures — with that lens, we’re going to see covenant is everywhere.

And it radically changes the depth that you can get out of the Old Testament.

President Nelson’s Invitation as a Lens

President Nelson’s Invitation as a Lens

President Nelson once asked us,

“As you study your scriptures during the next six months, I encourage you to make a list of all that the Lord has promised he will do for covenant Israel. I think you will be astounded. Ponder these promises. Talk about them with your family and friends. Then live and watch for these promises to be fulfilled in your own life.”

That is a fantastic lens for you to use as you study the Old Testament this year. Look for the promises extended to Israel. If you start to recognize what they are and start to list them or talk about how they work in your life, that lens will help you gather more out of the Old Testament uh by itself than almost anything else you can do.

Just that lens alone would change what you’re doing this year in Come, Follow Me.

Covenant Cycles: Blessing, Reversal, and Return

Covenant Cycles: Blessing, Reversal, and Return

So let’s look also then at the covenant cycles we’ll see in the Old Testament.

What happens when we don’t keep the covenant? Well, it’s not just that you don’t receive the blessings — those will vanish. Yes. But then God will reverse the blessings. In the scriptures in the Old Testament, that’s called cursings.

Sometimes I use the phrase covenant reversal because ‘cursings’ make my students think of Harry Potter and we get all out of whack. But when you think ‘reversal’, you don’t just get the lack of prosperity, you get destitution. You don’t just get the lack of a promised land, but you get taken away — a place to live, a place to belong, and so on.

God reverses that.

But why does he reverse it? So that we’ll recognize we need him and come back to him. Right?

The Covenant Corruption Cycle

I call this the covenant corruption cycle. Sometimes we’ll call it the pride cycle or the idolatry cycle. We see this cycle in all of scriptures and it has different manifestations in different uh countries or cultures or nations. In the end, it’s always about the covenant.

It’s a covenant corruption cycle. I don’t want to call it the covenant cycle because the covenant cycle is when we keep the covenant and that spirals us up to God. When we are not keeping the covenant, we keep corrupting it. Then we just keep spinning down and up, down and up. That’s the cycle we’re going to see in the scriptures.

So, look for that in the scriptures.

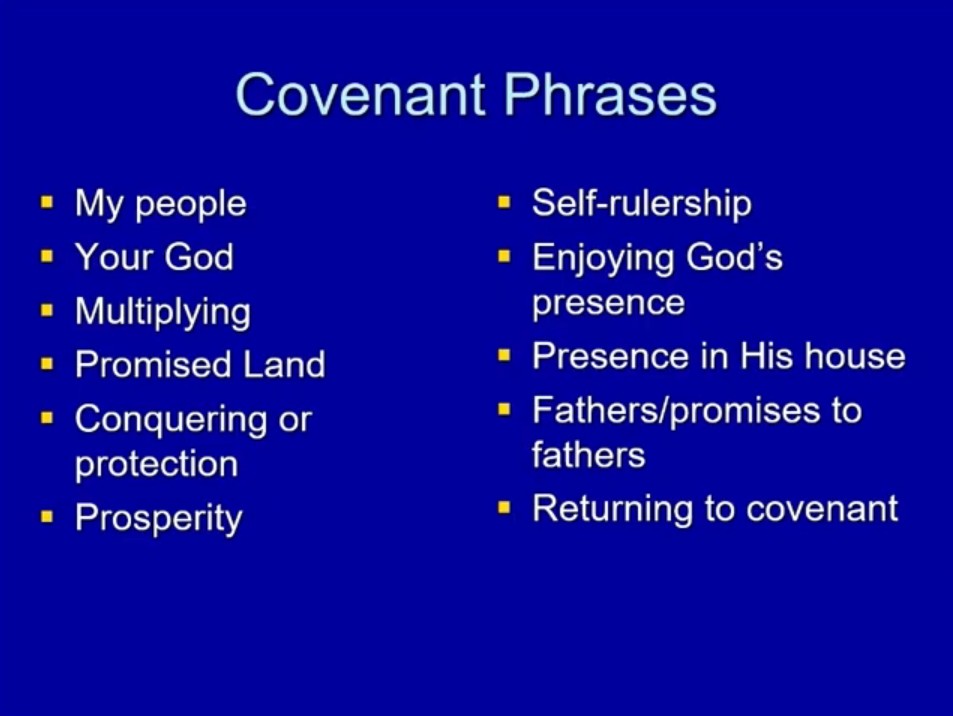

Look for Covenant Phrases

Look for Covenant Phrases

All right? I also want you to look for covenant phrases. This is really important and these will stem from those blessings we talked about. If you can find phrases that bring up what the blessings he’s talking about, you’ll recognize he’s talking about the covenant.

So, for example:

- Anytime he uses or any of the prophets use the phrase my people or his people, that’s the primary way God uses to talk about the covenant — us being his people and him being our God.

When you see that phrase, you know he’s talking about the covenant. Have that lens on and say, “Okay, I need to see what he is saying about the covenant here.” - The same thing when he says that he is our God. Any variations of that phrase — you know he’s talking about the covenant.

- When he talks about multiplying, making it so they have more seed, anything along those lines — he’s talking about the covenant.

- When he talks about a promised land — he is talking about the covenant.

Let me just give you one example that will help you. You’ve probably heard the commandment, “Thou shalt honor thy father and thy mother.” And then you may remember the associated promise or blessing with that: that thy days may be long in the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee.

Think of that. He’s talking about so that you can live in the promised land for a long time. He’s talking about covenant.

So in the end, that’s a shorthand for saying, “Honor your father and your mother so that I can give you all the covenant blessings.”

See, when we put that covenant lens on, what happens? It changes even little things like that. So, keep that covenant lens on:

“He was talking about the promised land — ah, covenant. Let me read that into it.”

Other covenant indicators:

- When he talks about conquering others or being protected from others conquering us — that’s covenant.

- When he talks about prospering — that’s covenant.

- When he talks about being able to be ruled by righteous rulers — covenant.

- When he talks about being able to enjoy his presence or come to him — covenant.

- When he talks about his house or being able to go into the temple — covenant.

- When he talks about promises to fathers or just fathers in general — covenant.

- When he says, “Come return to me” or “return to the covenant” — obviously covenant.

All right? So, those are some phrases that I hope you will remember, and when you see them, you’ll recognize he’s talking about the covenant.

That’s a lens that will help you get so much more out of the scriptures.

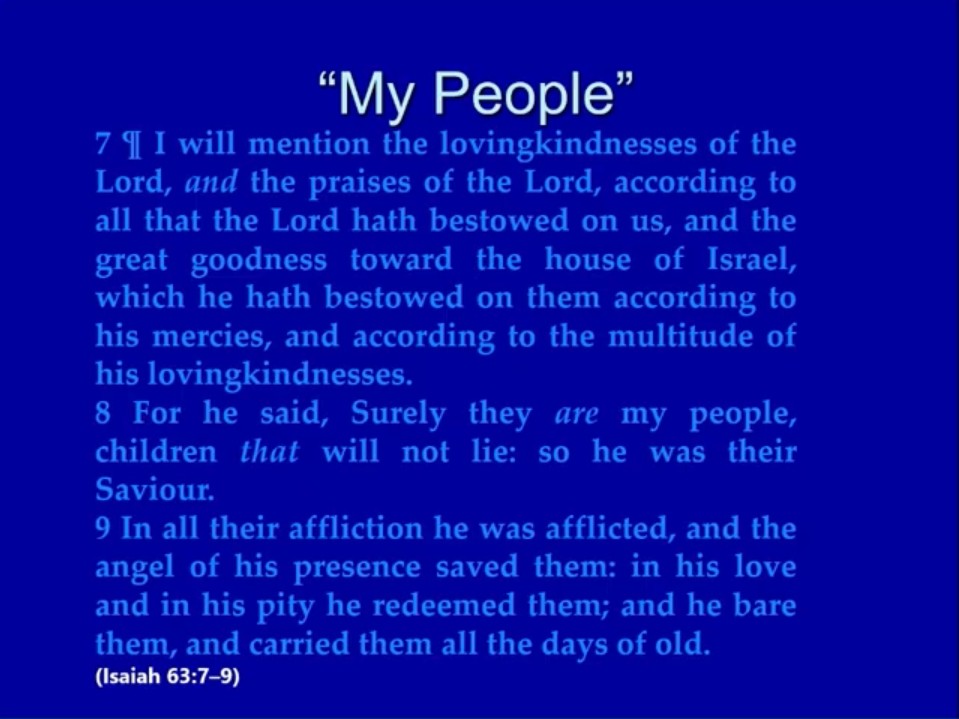

Example from Isaiah: “My People” Unlocks the Covenant

Example from Isaiah: “My People” Unlocks the Covenant

Let’s just use a couple of examples here. We have in Isaiah:

“I will mention the loving kindness of the Lord…”

So, just the loving kindness — that should clue you in.

“…and the praises of the Lord according to all that the Lord hath bestowed on us, and the great goodness toward the house of Israel…”

That should also clue you in.

“…which he hath bestowed on them according to his mercies and according to the multitude of his loving kindness…”

Hesed again.

But now look at verse eight:

“For he said, Surely they are my people, children that will not lie: so he was their savior.”

And then verse nine:

“In all their affliction he was afflicted, and the angel of his presence saved them; and in his love and in his pity he redeemed them; and he bare them and carried them all the days of old.”

This tells us that what he’s describing there — because verse eight leads to verse nine — what is that beautiful description in verse 9 about him redeeming us and carrying us? It is because of the covenant. And “my people” — we’ve got lots of other little clues — but once you see “my people,” you know for sure that’s what he’s talking about here.

And so we color the way we understand this because of the covenant.

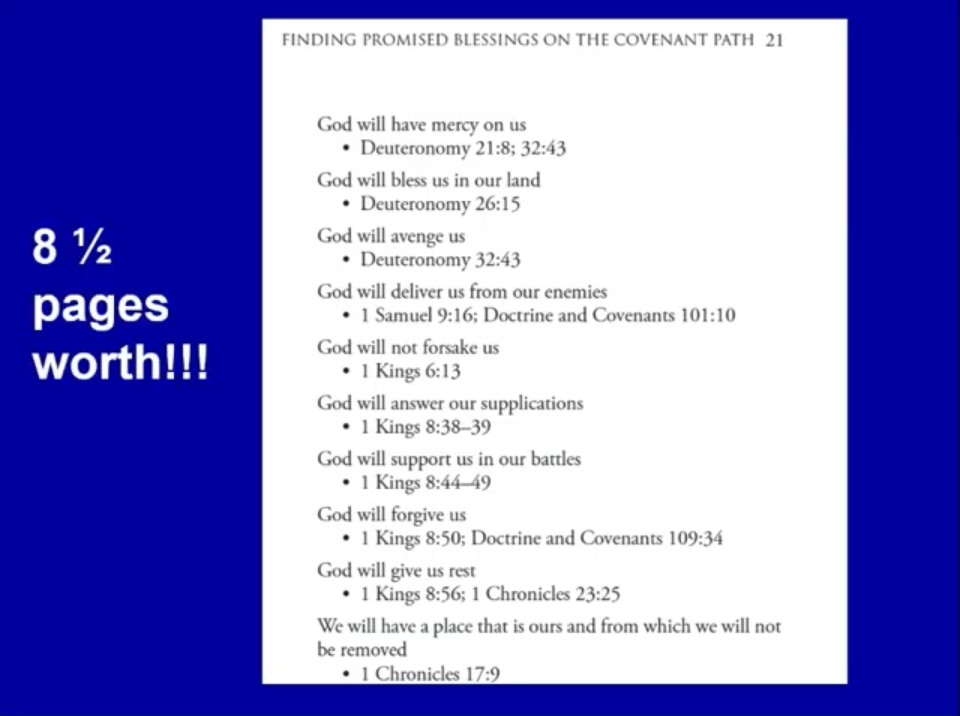

“My People” Appears Everywhere

“My People” Appears Everywhere

Now that was just one example. I once collected as many places as I could see a variation of my people or thy people or his people in the Old Testament — actually in scriptures in general, all throughout the scriptures.

And it blew my mind.

I published this, and I had eight and a half pages of summary of God doing something for his people.

Eight and a half pages of promised blessings using the phrase my people — so that you start to recognize he’s talking about covenant blessings.

It was amazing.

Covenant Promises Bring Comfort

And in fact, as I was one day reading this for the audio book, it was a day where I had just learned about some terrible things that had happened to a dear, dear loved one, and terrible things that loved one had done.

And it was a depressing day. It was one of the worst days of my life. Probably the worst day of my life at that point.

And then I went and read these blessings, and it became a tremendously wonderful and comforting experience.

I no longer feared for my loved one after reading all the blessings and mercies that God was promising that loved one.

And it came because I recognized the covenant phrases from God saying we are his people.

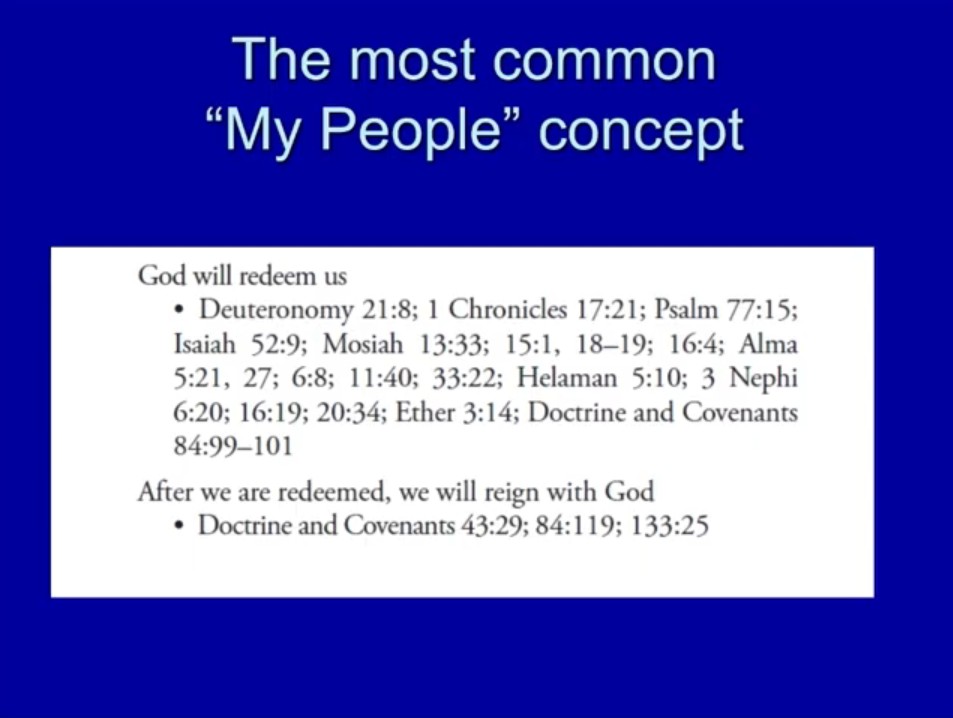

“My People” and the Most Common Covenant Theme

“My People” and the Most Common Covenant Theme

Now let’s just look at the most common “my people” concept. I then — when I collected all of these — I said, okay, what does he talk about the most when he uses the phrase my people?

And it’s redemption.

That’s the most common thing that God speaks of when he calls us his people. There’s something powerful just in that, isn’t there?

Do you see the kinds of things that can happen when you start to recognize covenant phrases in the scriptures? It’s a powerful lens.

So again, these are the phrases that I hope you will look for and recognize that God is talking about the covenant.

Examples: Reading Isaiah with the Covenant Lens

I’ll just give you another example. When um Isaiah says that we need to enlarge our tents and strengthen our stakes, what he’s saying is we have to do that because suddenly we’re going to have lots and lots and lots of children. So what he’s saying is, I’m going to give you these covenant blessings, right?

Another one that people often mistake: when Isaiah says, “Woe unto those who build houses one close into another.” When I was younger, I thought, “Wow, he really doesn’t like like uh duplexes or he doesn’t like apartment buildings or something.”

No.

If you read the whole thing, what he’s saying is: you had built lots of houses one unto another, but they will be destitute. No one will live in them. So suddenly what you realize — what he’s saying — is:

“Woe unto you because you were experiencing covenant blessings and now you’re not.”

But then he goes on to say that eventually you’ll have so many children that all the areas you’ve lived in won’t be enough. You’ll have to live in other areas because you’ll have so many children.

So he’s saying:

- Woe to you because you were experiencing covenant blessings

- Now you’re not

- But when you repent, you can experience those blessings again — even greater than you ever have

Recognizing that helps us understand what Isaiah is really saying.

Summing Up: The Blessings and the Gathering

Summing Up: The Blessings and the Gathering

Now, let’s sum up with one last thing. We’ve looked before at the blessings promised when we keep the covenant. I want to look in particular at several of these. In some ways, you could say all of them, but several of these — having a closer relationship with God and prospering and having a place to prosper and posterity and mercy.

All of these end up in the promise that God will gather us when he scatters us.

And so, of course, the scattering and gathering of Israel is one of the lenses we should have on all the time we’re reading the Old Testament.

And we understand this best if we combine all these things — we’re talking about understanding the nature of God, looking at the whole story, looking at symbols, especially symbolic actions and symbolic stories, reading to see the covenant, and so on.

The Long View: A 2,500-Year Gathering

The Long View: A 2,500-Year Gathering

So, let’s just talk very quickly, very big picture.

God scattered the northern tribes. It’s tempting to think that’s the end of the story. He did that in about 720 BC and then he begins officially gathering with power in about 1820–1830 AD.

This is a 2,500-year cycle.

If it takes God 2,500 years to bring Israel in, then that’s what it takes. See how the story is not over yet? He’s continuing to work with us. He will gather Israel in even if it takes him 2,500 years — because that’s what it needed to humble Israel to the point where they were willing to come back to him.

That’s the story of the Old Testament. That’s putting on enough interpretive lenses that we get out of it some of the power that God wanted us to get out of it.

Family History About Coming Home

Family History About Coming Home

So, I hope we will recognize that this is family history and it’s family history about coming home. Maybe to this promised land, but really to promised lands as in gathering together and belonging together and coming back to God together.

That is what we will see. It’s an interpretive lens we can use, but it’s also what we will see when we use these interpretive lenses — so that we can come to Malachi 4:6, the very end of the Old Testament, and it says:

“He shall turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers.”

That’s covenant language actually, and it’s what God is asking of us and hopefully what we see in the Old Testament this year.

Thank you very much.