August 2019

I’m very pleased to be here and to be able to talk to you about Saints. It has been a privilege to be able to work on Saints as a writer and as a literary editor. I’m going to speak to you from that perspective today and talk a little bit about some of the stories that we’re going to be able to hear from women’s perspectives in Volume 2 of Saints.

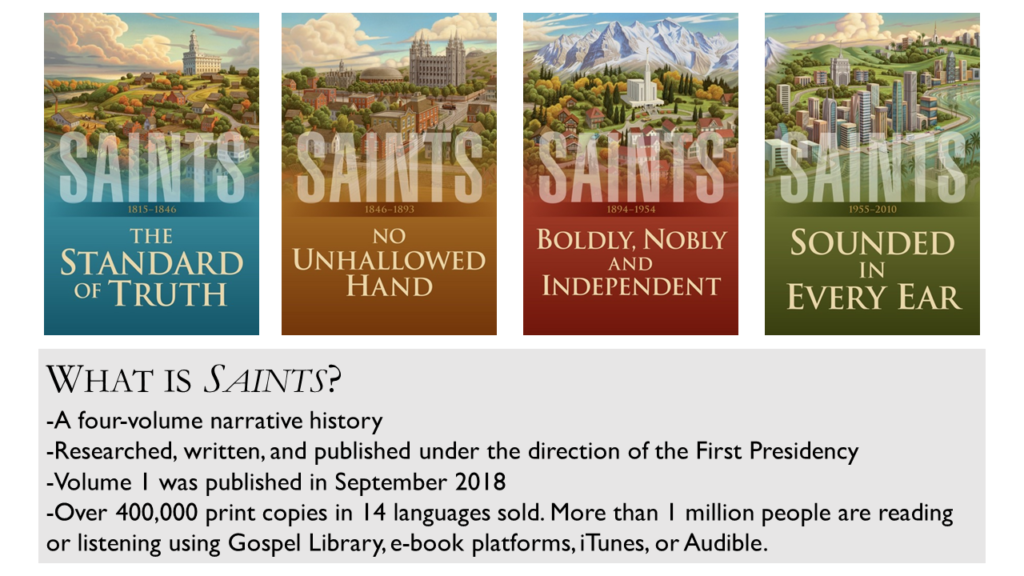

For those of you who might not be aware of Saints—I’m assuming most of you here probably already are aware of it—but for those of you who aren’t, Saints is a four volume history of the Church researched, written, and published under the direction of the First Presidency. Volume 1 was published in September of 2018, and there has been a great response to it. Over 400,000 print copies in 14 languages have been sold, and more than a million people are reading or listening using the Gospel Library app or EBooks or ITunes and Audible. We have found that the response has been very gratifying, in that it has been helpful to many people to be able to access Church history in a narrative way.

So what about Volume 2? That’s the question that I get often—when is Volume 2 coming out? It is scheduled to be released in the spring of 2020, and the first 6 chapters are going to be serialized. Some of you may have already read the first two chapters, which have appeared in the Ensign. Chapters 1–3 will appear in print and digital, and Chapters 4–6 are digital only.

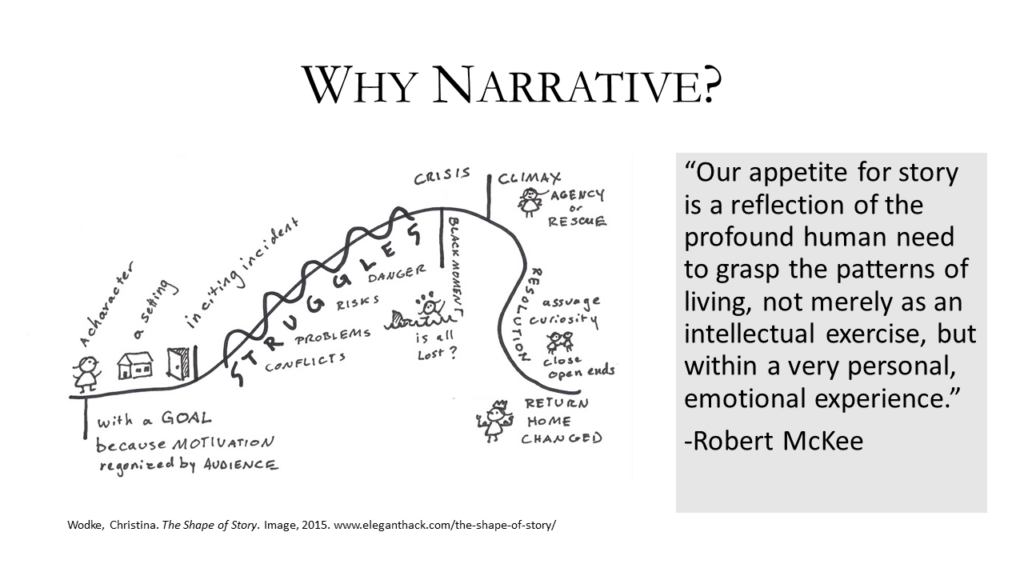

Now I want to talk a little bit about the choice that we made to write Saints in a narrative fashion. Why did we choose to create a book that is full of scenes and characters and dialogue, instead of what you would see as a more traditional history? One of the reasons is because narrative is inherently interesting. We are a story-making and a story-seeking people. When we look at stories we are able to see different perspectives. We are able to see different viewpoints and put ourselves in a story in a way that can draw us in.

You’ll see here on the screen—some of you may remember this from high school English class—the narrative triangle that looks like a witch’s hat, that has exposition and rising action and climax and falling action and denouement. This is a similar look at that kind of a narrative chart, but it has some elements to it that I think are important. When you’re trying to write a good narrative, you start out with a character who has a goal. Your character needs to want something and want it intensely. Then something happens that kicks off a series of events, and as we progress toward the climax, there are conflicts and problems and difficulties that need to be faced. Often there is what sometimes narrative theorists will call a “dark night of the soul,” or a time when it seems like all is lost. And then we finally reach the climax, where either through the character’s own agency or through rescue—and I personally prefer stories where it is the character’s own agency that provides the climax—the character chooses an action that allows things to resolve. We have the climax which leads to the resolution, and then – this is important as well – then our main character returns home changed. There is change as a part of good narrative. As writers on this project, that’s what we want to help readers understand and see as they are looking at the stories in Saints.

One of the important things about stories is that they help us do a couple of really vital things as readers or as listeners. Stories create community and enable us to see through the eyes of other people. They open us to the claims of others. “We tell stories to cross the borders that separate us from one another.” That’s a quote from a writer named Peter Forbes.

The photo that you’re looking at was taken in 1905 on Pioneer Day, and it is a gathering of all of the pioneers of 1847 who had come together for a photo. We know that the founding stories of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have helped to bind us together as a community. Those are the stories that we look to and say, “These are our people. This is the community that I belong to.” And it is our hope that as writers on Saints, as we continue through Volume 2 and then 3 and then 4, that we are going to be expanding the stories that we all collectively know as members of the Church. We will include global stories and stories that may not be as familiar that will help to continue to bind us together.

We also tell stories to “cross the borders that separate us from one another.” One of the wonderful aspects of storytelling is that it allows us in a risk-free way to pop into the life or the mind of someone else and to be able to experience vicariously what someone else is going through. When we are in narrative, we are able to sink into that more deeply and connect to people whose experiences are very different from ours in ways that we couldn’t otherwise do.

So then the question is, why am I talking about women specifically here? The first reason is because I was asked to talk about women specifically. But it’s also important to note that there are reasons we are trying to foreground the stories of women. One reason is because historically women have not been well represented in all history, not just in Church history, but in history in general, and it’s important for representation. As a woman, I know that I appreciate hearing stories of other women. They resonate with me; there are things that I can identify with. But I think it’s just as important that men hear the stories of women for the very reason that I just mentioned, that it helps to increase empathy. Storytelling is an empathy-building exercise. I would even say it’s a charity-building exercise. And so when we allow ourselves to participate in the story of someone whose experience is different from our own experience, we grow. Also, these stories are just plain interesting. I think you’ll find the stories of women in Volume 2 very fascinating.

What I’m going to do now is to highlight a few specific women that appear in the pages of Saints Volume 2.

The first one here is Emmeline Wells, and she is a more well-known Latter-day Saint. I’m sure many of you are already familiar with her. I’m going to start with a quote that comes directly from her.

Although the historians of the past have been neglectful of women, and it is the exception that she be mentioned at all; yet the future will deal more generously with womankind, and the historian of the present age will find it very embarrassing to ignore women in the records of the nineteenth century. We may say with propriety that there is a class of women on earth now whose lives and labors are likely to be recognized even by the average historian.

I hope that the average historians are doing their best to recognize the lives of these women in the nineteenth century. Also, the title of this presentation is “Women’s Voices in Volume 2 of Saints.” I could have read you some of the scenes from Saints that we writers created, but I decided that I wanted to share some of the source material directly, the voices of the women themselves, their own writing. Part of the reason is because all the women that I’m highlighting today are fabulous writers and storytellers in their own right. I wanted some of their words to be able to speak for themselves.

Now a little bit about Emmeline. She joined the Church in 1842 at age 14. She was married soon thereafter to a young man who had also joined the Church, but after they arrived in Nauvoo she had a baby that died, and she was abandoned by her husband. After that happened, she married Newel K. Whitney. They were married until he died. Then she married Daniel Wells. We’ll talk a little bit more about Daniel Wells in a minute. Her first child was a son who passed away, and then she subsequently had five daughters.

She was the editor of the Women’s Exponent from 1877 to 1914, and it was a powerfully influential magazine that really informed the thinking of members of the Church at that time. So she had a profound influence. She oversaw the Relief Society’s grain storage efforts and was a leading voice in the women’s suffrage movement, was the secretary of the Relief Society for over 20 years, and then at the age of 82 was called to be the General President of the Relief Society. Imagine that calling coming at age 82, but she was up for it.

I have a few quotes here directly from Emmeline. As I said, she was a powerful force for women’s equality and for religious freedom. Beginning in the 1870s and escalating up until the early 1890s the Saints were experiencing increased persecution at the hands of the government. Emmeline did all that she could to try to help defend their rights. As we see in this first quote, she said:

I desire to do all in my power to help elevate the condition of my own people, especially women. (Emmeline Wells’ diary, Jan 4, 1878)

And she did that, was an advocate in many different forums. As you’ll see in Saints, on two different occasions she spoke directly and met directly with presidents of the United States, first in 1879 with President Rutherford B. Hayes and then in 1886 with President Grover Cleveland. Both times the presidents who met with her privately were respectful and listened to her. However, they were not moved to any action really to help the Saints at this time with issues pertaining to their religious freedom. The political opposition was just too great.

After that second meeting she wrote in the Women’s Exponent:

All that can be done here in presenting facts and seeking to remove prejudice seems only a drop in the ocean of public sentiment, but one must not be weary in well doing, even though the opportunities may be few and the prejudice bitter. (“Notes from Washington,” Woman’s Exponent, May 1, 1886)

And she continued, never wearying for years and years and years as an advocate.

She was also very dedicated to the Relief Society and saw her work for women’s rights and her work for the Relief Society as connected in very meaningful and important ways. In 1892, we highlight in Saints the 50th anniversary of the Relief Society founding. They had a Jubilee celebration, and this is what she wrote about that:

What does this women’s Jubilee signify? Not only that 50 years ago this organization was founded by a Prophet of God, but that woman is becoming emancipated from error and superstition and darkness. That light has come into the world, and the Gospel has made her free, that the key of knowledge has been turned, and she has drunk inspiration at the divine fountain. So much good has been accomplished, not only in works of charity and blessings, but in the development of the higher attributes of the human soul that tend to purify, exalt, and uplift the world. (“Relief Society Jubilee,” Woman’s Exponent, Apr. 1, 1892, 20:140)

She saw her role in the Relief Society, her experiences in the Relief Society, as an opportunity not only to better herself, but to better the world.

So now I’m going to talk a little bit about some women who might not be as well known. I primarily worked on the last quarter of Volume 2. During this time in Church history, as I said, there was a lot of persecution that was happening related to plural marriage. Some of the stories that we are going to be telling about this struggle have to do with women who are dealing with some very difficult issues and have to make some incredible sacrifices. Some people might say, “Why are we telling these stories about plural marriage? Stories about plural marriage make me uncomfortable. They’re hard. They’re difficult.” My answer to that, at least in this context right here, is twofold. The first reason is because by telling these stories we honor the struggle. This quote is by M. Russell Ballard:

We owe much to the pioneers and must never forget that the success of today is built upon the shoulders and courage of the humble giants of the past. (M. Russell Ballard, Ensign July 2013)

Often when we hear a quote like that, what’s the first thing that we think of? We think of Missouri. We think of Illinois. We think of the trek west. But I hope that you will find, after reading Volume 2 especially, that these sacrifices did not end once the Saints came to Utah. They were made over and over and over again–sacrifices that greatly strengthened the people who chose faithfully to endure challenges and came out stronger and better for it. This is just as much a part of our heritage as a church as those pioneers crossing the plains stories.

The other reason we’re telling these stories—and this is coming from a more narrative perspective—is that when we are reading a book, when we’re reading a story, we need a reason to keep turning the pages. There is an old adage that writers use: only struggle is interesting, or only conflict is interesting. None of us wants to read a book that says there were two beautiful, fascinating, talented people who met each other at the prime age for marriage. They got married. They had a fabulous marriage. They had four gorgeous and exceptional children, and they had a life full of delights and wonders, and then at the age of 85 they both died on the very same day.

That’s good for them. Yay for them! But that’s not necessarily a book that you want to read, because in a narrative, people need to have struggles and challenges and issues and conflicts that they are striving to overcome. This quote is by John Gardner, who is a writer and expert on narrative. He says:

In the relationship between character and situation there must be some conflict. Certain forces within and outside the character must press him toward a certain course of action, while other forces both within and outside must exert strong pressure against that course of action. Both pressures must come not only from outside the character, but also from within him, because otherwise the conflict involves no doubt, no moral choice, and as a result can have no profound meaning. (John Gardner, The Art of Fiction)

There’s a part of me that likes looking back at pioneer stories and thinking, “Wow, they are so impressive. They faced everything with courage. They never doubted. They never faltered. They never questioned. There was never a stumbling block that they could not overcome.” But in other ways, it’s not as helpful for me to only see the stories of triumph, because then I tend to see the pioneers as flawless heroes, completely divorced from who I am as a fallible person who is dealing with doubt and conflict and trouble. For me, it’s more helpful to see some of these people struggling with some of these issues and to see how they overcome them.

I also wanted to give a little background about plural marriage in the 1880s. By this point most Latter-day Saints accepted and defended plural marriage as a doctrine of the Church, but the practice itself was declining. It was mainly practiced in the American West. There were places around the world where Latter-day Saints lived where it was not nearly as prevalent. The 1850s was the height of the practice of plural marriage. Around 50% of the people in Utah could expect to be a part of a plural family either as a child or a spouse at some point in their lives. But by the 1880s it was around 20–30%, and that was shrinking, especially with the generation that was coming into marriageable age right around 1880.

Also, just a little bit of background about some of the issues that were happening at this time in the country. Beginning in 1862 the U. S. Government passed laws against plural marriage. And in 1879 the U. S. Supreme Court ruled that the laws were constitutional, and those who practiced plural marriage were prosecuted, fined, and jailed. The laws became even more punitive in the 1880s with the advent of the Edmunds Act. The Edmunds Act, which was a federal statute that was signed into law in 1882, disenfranchised participants in plural marriage, not allowing them to vote or run for office. It created a new category of crime. Instead of being able to be arrested for polygamy, which was harder to prove, people were being arrested and jailed for unlawful cohabitation, where you didn’t necessarily have to prove that they were married. You just had to prove that they were living together or having children together, and that made prosecutions easier.

And then in 1887, the Edmunds-Tucker Law was passed. That disenfranchised all Utah women. Before that point Utah women had the right to vote, but after Edmunds-Tucker was passed, that right was taken away. No matter if they practiced plural marriage or not, they were just disenfranchised. Also, the government then had the right to confiscate all Church property valued over $50,000, which of course included the temples. So the government was definitely waging a war against The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints through laws and the courts and other methods.

Because so many men particularly—although some women also went to jail—but because so many men who practiced plural marriage during this time were being arrested and thrown into jail, men and women went on what was called the underground, essentially hiding from the federal marshals. Some women who had more means, they would go live somewhere else, and their husband could provide them with a home, and they could live there. For other people who didn’t have means, they might hide in someone’s house. You couldn’t go out during the day because there were informers who would say that you were there. The reason that women, second, third, and fourth wives in plural families, went on the underground was because if federal marshals found them—and they would knock on people’s doors and bust in and go search through everything to find them—they could compel them to testify against their husband, and that would then cause their husbands to have to go to jail. If they refused to testify, they themselves would go to jail. So some men went on the underground. A lot of women went on the underground as well.

The first woman I want to talk about is Ida Hunt Udall. I think because I’ve been writing about all of these women for so long now, I really do just love them all. They’re all wonderful, but Ida Hunt Udall is especially wonderful.

She is the granddaughter of Addison and Louisa Pratt, and if you’ve read Volume 1, Addison and Louisa Pratt are characters in Volume 1. She’s their granddaughter. She lived in Beaver, Utah, and then helped settle Snowflake, Arizona. She was a very talented musician and writer and teacher, a very intelligent woman. She married David Udall as a plural wife in 1882 at the age of 24. Those of you who are familiar with Arizona politics might recognize the last name Udall, and that’s this family. She lived on the underground for three years, from 1884 to 1887. There is a wonderful book written about Ida by her granddaughter Maria Ellsworth, called Mormon Odyssey. It uses Ida’s journals and letters to tell the story of her very eventful life.

So just a little bit of background about Ida. Ida did not grow up in a plural marriage. But she respected those who did practice plural marriage. When she was 18 years old, her family was asked to move to Arizona and to help settle Snowflake, Arizona, from where she had been growing up in Beaver. Her beloved grandmother lived in Beaver, and so Ida stayed behind in Beaver for a little while to help her grandmother while the rest of her family went to Snowflake. At some point her family said okay, we want you to come with us. We know you like it there in Beaver, but you need to come be with us in Snowflake. So Ida went with a family that was also traveling to Arizona to go meet up with her family in Snowflake. The family that she was traveling with was a plural family, and Ida found herself very impressed with them. The women, she wrote, had a very unselfish quality, and there was a harmony and a cohesion in the family that she admired. She decided at that point that she wanted to participate in plural marriage. And as I said before, fewer and fewer people of her generation, of her age, were choosing to participate in plural marriage. But she decided that she wanted to.

She arrived in Snowflake, and she had a boyfriend named Johnny back in Beaver who wanted to marry her, but he didn’t want to practice plural marriage, and so she turned him down. She was getting a little bit older by the standards of the time and was 23 years old and not married, and her younger sister had gotten married, but she was waiting for the right guy. She was working in a nearby town called St. Johns, at the co-op store that was run by the bishop, David Udall, and she was friends with his wife Ella. David had been a little hesitant to practice plural marriage, but because he was bishop he felt that he had to set a good example. So he and his wife talked it over and decided that it was time for them to find another wife to join the family. But unfortunately anytime David would suggest someone, Ella would come up with a reason why she wasn’t good enough for him, she wasn’t good enough for the family.

But then Ida comes along, and there is nothing that Ella could see to say badly about her. She was kind and smart and talented and just wonderful. And so they decided that David should propose to her. But it was very, very difficult for Ella. After David proposed to Ida, Ida could see how difficult it was for her friend, and so she decided to leave and go back to Snowflake. She wrote a letter to Ella and said, “I don’t want to do this if you are not behind it, because that’s not what I want to do.” She waited for a response, and finally she got a response from Ella that said,

The subject in question has caused me a great amount of pain and sorrow, more perhaps than you could imagine. Yet I feel as I have from the beginning that if it is the Lord’s will, I am perfectly willing to try to endure it and trust that it will be overruled for the best good of all.

At that, they decided that she would go ahead and be sealed to the family and planned to travel together to St. George to be sealed in the temple. At this point Ella and David have a little girl. They come by Snowflake, and they pick up Ella, and they take off across the desert. But it’s a little bit uncomfortable for Ida, because she can tell that Ella is struggling, and she doesn’t know what to do about it. This is an entry from her own journal in May:

Twenty-first Sunday was a beautiful day. The bright fields of Lucerne green orchards and singing birds made Kanab seem almost like a paradise after leaving such a country as the Colorado traverses. [They were stopping at Ella’s sister’s house.] After meeting repaired to Ella’s sister Sarah’s, where we partook of the bounteous repast, spent a pleasant evening in conversation, songs, and music. But with all the merriment I felt lonely and depressed, like a stranger in a strange land. The sorrow another was passing through seemingly on my account, though I was powerless to help it, the constant strain my mind had been on during the whole journey, lest by word or look I should cause her unnecessary unhappiness had weighed upon my spirits greatly, and I retired from the scene that evening with a feeling of dread and fear at my heart impossible to describe. Afterwards was greatly reassured by a moonlight walk, a conversation with the one dearest on earth to me, who brought light and hope to my heart once more, with loving, encouraging words, so that I finally went to bed feeling that in striving to obey the commandments of God with a pure motive, I had everything to live for. No matter how severe the trial, what a privilege to pass through it in such a glorious cause. (Ida Hunt Udall’s Journal, Sunday, May 21, 1882)

I found that an interesting description of a difficult choice that she had to make. You will find with Ida, that over and over and over again, she turns to her faith, and she turns to the Lord to receive strength and understanding and the ability to move forward in creating her family. There is a lot more that happens to Ida, and if you want to find it out, you need to read Saints, Volume 2.

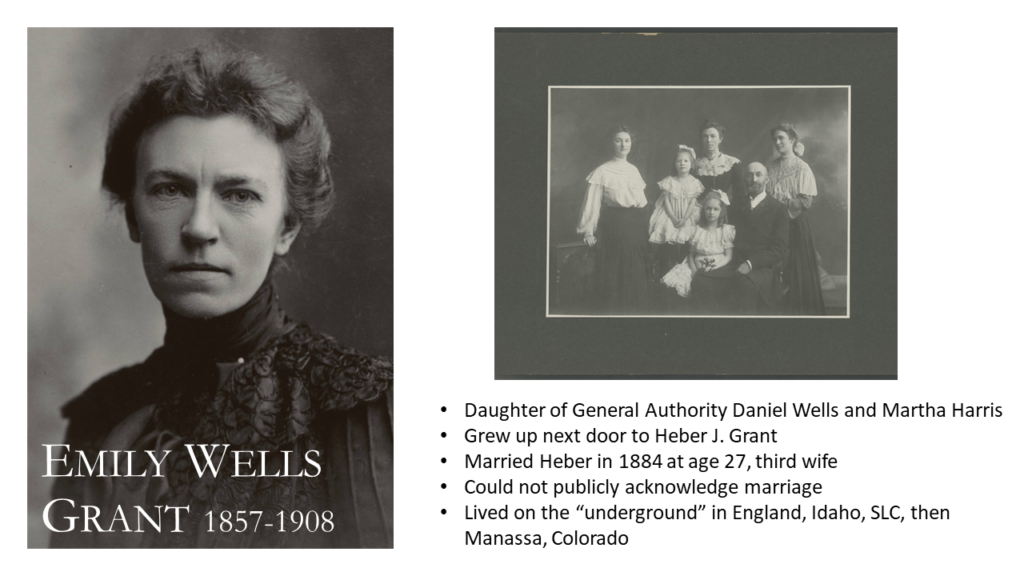

The other woman that I want to talk about is Emily Wells Grant. Some of you may be familiar with her. She is the daughter of the General Authority Daniel Wells and Martha Harris. She grew up in a large plural family. Emmeline Wells actually was one of her father’s other wives. She grew up next door to Heber J. Grant, and they were essentially high school sweethearts and dated throughout their teenage years. But when it came time to talk about marriage, they had a bit of a falling out. She did not want to practice plural marriage, and he felt that that was what the Lord wanted him to do. And so, she basically said, “I’m sorry. We’re going to have to break up, because I don’t want to practice plural marriage.” Heber then married another woman and went on with his life.

Emily was kind of a socialite of the time in Salt Lake City and was very popular and received a number of proposals that she turned down, partially, in reading between the lines, I think, because she was still in love with Heber. And Heber still was in love with her. Eventually he proposed to her again in 1883, and she turned him down. And then in 1884 he proposed to her again, and this time she said yes. At the time that they were married the persecution against the Saints had really ratcheted up, and at this point Heber J. Grant was a new apostle. And so he was on the list. If you were a well-known Latter-day Saint you were more likely to be arrested. They couldn’t let anybody know about their marriage, and she immediately went on the underground.

During Emily’s time in the underground she had two daughters. She moved from England to Idaho to Salt Lake City until she finally moved to a place called Manassa, Colorado. I don’t know if any of you have ever been to Manassa, Colorado, but it’s a place you’ll get to know in Saints. A number of polygamous families had settled in Manassa, since it was so far out of the way. It was a place where federal marshals – they were all over in Utah – but it was way kind of out in the boonies, so they weren’t as likely to bother the Saints there. And if the federal marshals did come to try to find you, there were ways that people could be notified that they were coming. Different laws also applied in Colorado, since it was a state, than in Utah, which was a territory. So some Saints just felt like Colorado was safer.

There were plural families that had relocated to Manassa, but there were also a number of women like Emily – they called themselves widows – who relocated there. About 10% of the population of Manassa at this time were wives in plural families who were establishing different households. Emily became one of those women and went there with her two little girls, and it was hard for her. It was, like I said, kind of out in the boonies. It was this treeless, flat land where the wind would just howl. And she was a young mom and has two kids, and wants to be near her husband and family, but instead is out here in Manassa. It’s important to remember with history that we know what ends up happening, but in the moment when we’re writing the story, the characters don’t know what is going to happen. For Emily at this time there was a real chance that she might have to live there forever, and that was something they had to prepare themselves for, which was hard for her to reconcile.

I am going to read just a few quotes directly from Emily’s letters. I’m going to go back to this picture. You look at this picture and you look at the picture of so many pioneer women, and they’re just so buttoned-up, and they seem like they are just so proper and maybe even stern. But then you read their writing and you get to know them as complicated, interesting, and even funny people. And I find that that’s true with Emily.

She wrote a lot of letters to her husband while she was in Manassa. These are just a few excerpts from these letters.

It is against my principles to allow the 27th to ever pass without writing you a letter [they were married on May 27th, so every 27th they both made sure that they wrote to each other] and telling you how fondly I love your dear self. (July 27, 1890)

And in another letter:

I feel so grateful and love you so very much I cannot satisfy myself telling you how I feel & just wish I had an opportunity to express my true sentiments in a more substantial manner than having to resort to our old stiff pen and some horrid ink to tell you that you are the best and kindest old darling the sun ever shone on. (August 11, 1890)

Then she also is very open about her struggles, which personally I think that can be very healthy in a marriage. So I’m glad to see that she is open with her husband about some of her concerns.

The worst part of this programme is when you leave me. I am so grateful and so happy to have you come, so homesick and forlorn when you go. (April 27, 1890)

And one important thing to also point out with Emily, which is interesting, she was living in Manassa under an assumed name, so she was not going by her married name. She even gave her two daughters different names than the names they had been given at birth. Marshals would sometimes talk to children because they wouldn’t edit themselves, so Emily told her children that Heber was their Uncle Eli. These girls didn’t even know that he was their father, in order to protect him. Heber would come to Manassa occasionally, but the girls would think that it was their Uncle Eli who would come to visit.

I love this quote:

I am so tired and disgusted with the sight of cows, I feel like cussing at the very thought of them. (October 27, 1890)

And then this is how she signed off one letter:

I love you devotedly, but my heart is nearly breaking. You can give me credit for trying to write you a cheerful letter. (October 27, 1890)

And then another signoff:

We are well & just as tired, disgusted & homesick as ever we can be. (May 27, 1890)

Then this last one is kind of funny. There were a number of polygamy widows that were in Manassa, and when some of the Church leaders would come around to visit, people were always excited, as they often are when Church leaders come to visit. And a lot of the women who were there were kind of lonely. So the First Presidency had come for a visit, which was very exciting, and in the note that Emily wrote to Heber about that visit, she said:

In all my life I never enjoyed a sermon as much as the one preached by Brother Joseph F. He has grown handsomer than ever, I think, and is so very pleasant. We are all dead in love with him, and one of the widows remarked that she wished she was not married. Brother Cannon was perfectly irresistible too. (August 19, 1890)

Just a little tweak right there. But her voice and her personality that come through in these letters is just delightful. And just looking at the time, I’m just going to read one more about her desire to rise to her challenges.

I feel lonesome of course since your departure. Never expect to see the day when I can help regretting that we can’t see more of each other. Still I appreciate small favors, and were it not for the little visits we have with each other from time to time, life would not be worth the living. I rejoice in our love for each other and would rather the fire burned, even if it hurts occasionally, than to become hardened and indifferent. (September 14, 1890)

(I love that last line: would rather the fire burned, even if it hurts occasionally.)

And then finally:

I’ll tell you, sweetheart, what I have decided to do, to give myself up entirely to good books & to pray to my Heavenly Father constantly to aid me, to understand and appreciate what I read, to never shirk a duty, but take everything as it comes along as uncomplainingly as possible, to be prayerful under all circumstances, and acknowledge the hand of the Lord in all things…. The wind may blow and the chickens fail to hatch, let the frost come, who cares if we can all only be well and have that comforting spirit at all times…. (June 24, 1890)

I’m going to just cover Lorena very briefly, and unfortunately I’m not going to be able to get to Susa Young Gates.

Lorena Larsen’s story is also a fascinating one. She also lived on the underground and for her, hearing about the Manifesto was difficult because she had sacrificed so much to live in plural marriage. She was worried as the second wife what the Manifesto meant regarding her status with her relationship with her husband. Lorena, you will find in Volume 2, is a very spiritually powerful, even a visionary woman. She had a number of dreams. She had a number of very powerful spiritual experiences that showed her that God was with her. Now I am just going to read her description of finding out about the Manifesto. She and her husband had been living in Colorado also, in a different town, but he couldn’t make a living, and so they had turned around and were coming back to Utah during the time of general conference when the Manifesto was read.

My husband came to our tent and told me about it, and my feelings were past description. [He had gone outside the tent to ask people who had actually been in Salt Lake if that actually did happen, because they weren’t sure if they believed it.] I had gone into that order of marriage … because I believed God had commanded his people to do so, and it had been such a sacrifice to enter it and live it as I thought God had wanted me to. And as I thought about it, it seemed impossible that the Lord would go back on a principle which had caused so much sacrifice, heartache, and trial before one could conquer one’s carnal self and live on that higher plane and love one’s neighbor as one’s self. My husband walked out without saying a word, and as he walked away I thought, “Oh yes! It is easy for you. You can go home to your other family and be happy with her, while I must be like Hagar, sent away.”

My anguish was inexpressible, and a dense darkness took hold of my mind. I thought that if the Lord and the Church authorities had gone back on that principle, there was nothing to any part of the gospel. I fancied I could see myself and my children and many other splendid women and families turned adrift, and our only purpose in entering in it had been to more fully serve the Lord. I sank down on our bedding and wished in my anguish that the earth would open and take me and my children in. The darkness seemed impenetrable.

All at once I heard a voice and felt a most powerful presence. The voice said, “Why, this is no more unreasonable than the requirement the Lord made of Abraham when He commanded him to offer up his son Isaac, and when the Lord sees that you are willing to obey in all things, the trial shall be removed.”

There was a light whose brightness cannot be described, which filled my soul. And I was so filled with joy and peace and happiness that I felt that no matter whatever should come to me in all my future life, I could never feel sad again. If the people of the whole world had been gathered together trying with all their power to comfort me, they could not compare with the powerful unseen presence which came to me on that occasion. (Autobiography of Lorena Larsen)

This is a really amazing spiritual experience. And Lorena has a number of them. Lorena’s story is also fascinating, and much more happens to her. If you want to know what happens to Lorena, read Saints Volume 2.

So Susa Young Gates is also fascinating, but our time is short. She’s a little more well known, and I hope you enjoy reading about her in Volume 2.

I want to conclude with a quote that was written by Lorena’s eldest son that I found when I was doing some of the research on this character. To me, it encapsulates what reading Saints is all about. This is the message that I hope and believe that Saints portrays for people:

Mother believed in a live Church, a divine Church in which the Father in Heaven communicates with His prophets for the solving of contemporary Church problems. Mother believed that the universe is a society of individuals. In this society there is need for much cooperation, where we all work together for the common good. This requires both leadership and followership training. This requires loyalty and the helping of others. But also in this plan of salvation, this scheme to develop each and every individual to his highest earthly capacity, there is much need for individual initiative and responsibility. One responsibility is to know and understand both the letter and the spirit of the gospel of Christ. (B.F. Larsen, son of Lorena Larsen, Lorena Larsen Family History Book)

That’s what Lorena’s life taught her, and that’s what I hope that by reading Saints, we can learn through her and people like her. Thank you.

QUESTION 1: OK, this is a good question. We hear that almost everyone living in plural marriage was miserable. What is your view?

ANSWER: My view is that is absolutely not. It was a challenge. Marriage is a challenge. Living in plural marriage amplified the challenge of marriage. But there were many Saints who had happy and fulfilling experiences alongside the challenges of plural marriage. But that’s not to say that there was not a great deal of sacrifice that was involved. And there were people who did have difficult and challenging experiences in plural marriage. You have to acknowledge that, of course.

QUESTION 2: Are there any fictional characters, events, or conversations in the Saints series?

ANSWER: No. As writers, we are definitely constrained by the source material. Actually when I was writing an Emily Grant scene early on when I first came onto the project, I had always been taught as a writer to show, don’t tell. So instead of saying someone was scared, show that they’re scared. So in my first scene that I wrote, Emily is letting her daughters go play with their half-sisters for the first time, and they’ve been with her for so long, and she’s really nervous, and in the account it says Emily was scared to see them go. In my mind as a writer, I’m like, well OK, I’ll just have her holding her hand and say, “Emily was holding her daughter’s hand and was squeezing it tight.” Oh no, no, no, no, no. You can’t do that. It doesn’t say anywhere in the source material that she was holding her hand. So trust me, if there are quotations around something it’s because there was dialogue in the source. If it says it was raining, it was because it was actually raining. All of that is sourced.

QUESTION 3: Obviously part of the purpose of Saints was to include historical incidents which some find troubling. How do you decide what to include?

ANSWER: That’s a good question. I will first say there are lots and lots of people with input about what goes into Saints. And there are lots and lots of discussions. But I think the most important thing is that we are doing our best to provide an honest, transparent, well-rounded view of Church history with a view toward bolstering faith, answering questions and bolstering faith. That doesn’t mean that we are ignoring things that are difficult. We don’t want to ignore things that are difficult. But it means that we also feel part of our job is to show a nuanced view of challenging experiences. Like these stories of plural marriage–while it was undeniably difficult, it also contributed to building faith and strengthening people’s relationship with God. We are trying to balance those two things.

QUESTION 4: Critics suggest the Manifesto was a result of government pressure, not revelation. How can we respond?

ANSWER: I think this will be a very interesting aspect of Volume 2 for so many people who read it. There is no doubt that there was an incredible amount of government pressure that was happening at this time. All the things I talked about were really bearing down on the Saints, but it was also a revelatory experience for Wilford Woodruff when he decided to move forward with the Manifesto. Prophets operate in the era that they are a part of, and Wilford Woodruff was operating in the era that he was a part of, but he also received revelation from God in making that decision. So I don’t think it has to be either or. I think that it’s both.

QUESTION 5: Will we have in our future government restrictions on the Church like the Edmunds/Tucker Act?

ANSWER: Unfortunately I don’t have a seer stone, so I do not know. I hope not, but it is a good reminder of why religious freedom is an important thing for us to be mindful of.

QUESTION 6: Is there a reference for the Lorena Larsen quote on the Manifesto and Abraham?

ANSWER: Yes. So her autobiography was published by her children. I think BYU has a copy of it. The Church History Department has a copy of it. It’s called The Autobiography of Lorena Larsen, and you can find it there.

[This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and readability.]