Summary

John Gee argues that defending the Church is most effective when informed by actual data rather than anecdotes. Drawing from extensive social science research, he shows that apostasy is often driven more by behavioral issues, such as sin, pornography use, divorce, and moral relativism, rather than purely intellectual doubts. Gee defenders of the faith to focus on truth, be concrete and credible, and respond to doubts early and supportively to strengthen belief and preserve faith.

This talk was given at the 2020 FAIR Annual Conference on August 6, 2020.

John Gee is a professor of Egyptology at Brigham Young University and a respected scholar of ancient texts and religious studies. In addition to his work on the ancient world, he brings a data-driven approach to modern faith challenges, exploring how behavioral patterns influence belief and apostasy.

Transcript

Introducing Dr. John Gee

Scott Gordon: Our next speaker is John Gee. Dr. John Gee is the William Bill Gay Research Professor in the Department of Asian and Near Eastern Languages at Brigham Young University. He has authored over 150 publications, including three books, and editor of eight books, and has edited a peer-reviewed international professional journal, and served on the board of trustees of national and international organizations. With that, we’ll turn the time over to Dr. John Gee.

John Gee: Thank you. I’d like to thank Fair Mormon for inviting me to come. I hope that what I have to say might be of some benefit to you. I am going to take a step back from my usual focus on the ancient world and ancient scripture to look at the larger issue of what sort of defense of the Church is actually effective.

John Gee

By the Numbers: Saving Faith

Presentation

Elder Neal A. Maxwell was passionate about using data to make decisions. His biographer related:

Neal always liked having reliable data as the homework for a large institution, including the Church, to understand what is really happening in making major policy decision. That was the impulse that had prompted him to ask for demographic projections of Church growth, which helped President Lee to explain the need for the regional representatives. A similar urge had prompted Neal as Commissioner of Education to request a study of the educational needs of international Church members, which helped clarify the policy of giving high and rapid priority to religious education, rather than simply building more Church schools. This approach was Neal’s analytical vision at its best.”[1]

To that end, when Elder Maxwell was put in charge of Church Correlation, he created a new division in Correlation, now called the Correlation Research Division, to evaluate the effectiveness of various Church programs, because the Church was now so large and so diverse that the General Authorities could no longer rely on their own first-hand impressions to know what is going on in the field. As Neal liked to say about the limits of informal data-gathering processes, let’s avoid being “victimized by our own personal impressions and anecdotes.”[2]

Sometimes when new programs were proposed, Neal would try to help everyone see that those giving overall direction to Church programs need to be “in on the takeoffs as well as the crash landings.”[3]

The Importance of Data

In defending the Church most of the time we approach the problem without having gathered data. Most of us, indeed most of you, defending the Church have gathered our data by relying on first-hand impressions gained from experience and swapping anecdotes. This has its place. Anecdotes help illustrate data and make it concrete. But it does not replace actual data.

Although the Correlation Research Division does have data, it is for the use of General Church leaders, which most of us are not. But there is a great deal of data already out there that can be used to understand how to defend the Church better. This is publicly available data, some of it extremely high quality and others not so much. We can analyze and study this data and use it to determine what practices work best.

The data that I’m using, coming from over three hundred studies, was not always gathered with our interests in mind, and may not answer all the questions that we have, but we should still use the information at our disposal. I have assembled a lot of this in my new book, Saving Faith,[4] and you are welcome to look at it there. I’m not going to cover quite the same ground in quite the same way that I did in my book. Many things that I only have time to cover briefly here are covered in more detail there. Here I want to look at what the outside data tells us are the best practices in defending the Church, which is the purpose of this conference.

Caveats

Right up front I want to emphasize a couple of caveats. Although I am using social science research I will be translating the social science terminology into terms that Latter-day Saints are more likely to understand. Social scientists might object to carefully crafted nuances being lost in translation. For the sake of clarity, I will dispense here often with nuance.

The second is to remind you that while I will describe general patterns that apply in many, and perhaps most cases, there are exceptions to the general rule. As one Relief Society president put it: “We will establish the rule first, and then we’ll see to the exception.”[5] So I will talk about the general rules here, not exceptions. If we do not know what the general rule is, we cannot even tell if something is an exception. And I will be hitting a large number of topics, so discussion will be brief.

Leaving in Droves

In 2011, 2012, the story circulated that a certain General Authority had said in a meeting that the Church was losing youth in droves. This story is not true. Not only is it untrue, it is not true in two different ways. In the first place, the General Authority did not say that the Church was losing youth in droves, he was responding to someone else who claimed that.[6]

In the second place, we are not losing members in droves. That does not mean that we are not losing members. If we were not, none of us would be here. There would be no point to be here except to massage our own egos. While most other denominations are losing members—for example Mainline Protestant denominations lose two-thirds of their youth and young adults[7]—yet according longitudinal studies by the Gallup organization, “membership in a place of worship has been stable among Mormons, near 90% in both time periods . . . over the past two decades.”[8]

Of those who stay, they are more faithful and become more faithful over time.

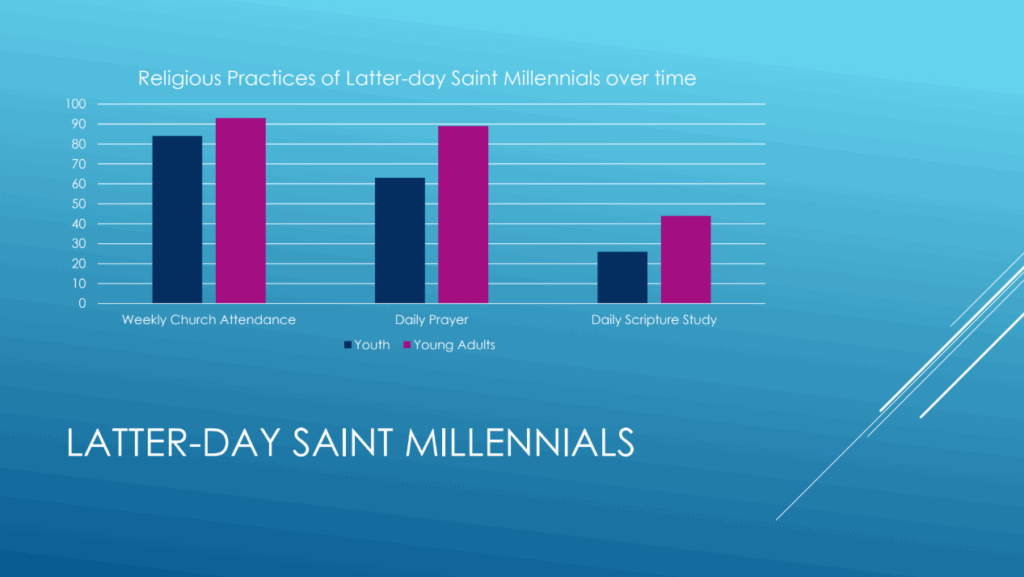

The longitudinal National Studies of Youth and Religion found that Latter-day Saint Millennials became more faithful over time, not less. Thus, weekly Church attendance went from 84% of Latter-day Saint teenagers to 93% as young adults. As teenagers, 63% of Latter-day Saint Millennials prayed daily, but as young adults, 89% did. As teenagers, 26% of Latter-day Saint Millennials read their scriptures daily, but as young adults, 44% did.”[10]

Conversion and Apostasy

Most of you have come to this conference in hopes of finding tools to prevent apostasy, and most likely of loved ones, because you see a departure from the “plan of happiness”[11] as adversely affecting the long term happiness of those who apostatize. Secularists see such an exercise as either misguided or pointless. From their perspective, truth is either determined by the individual, or does not exist, or is not whatever Latter-day Saints think it is.

Secularists tend to be relativists, and from a relativistic perspective conversion and apostasy are two sides of the same coin. When one switches religions, one apostatizes from one religion and converts to another. At least, that’s their relativistic view. Nearly half (44%) of Americans will adopt a religion different from the one they were raised in.[12] But some of the sociological research shows that this is not the case.

Sociologically apostasy and conversion look very different both in causes and effects. Thus conversion and apostasy “are associated with different factors, and are best understood as distinct processes.”[13] There are “personality, family, behavioral, and contextual factors” that influence apostasy, while demographic factors “do not appear to have much of an effect at all. On the other hand, demographics are very important predictors of considerable increases in religiosity.”[14] Who one is plays more of a role in conversion, while what one does plays a greater role in apostasy.[15]

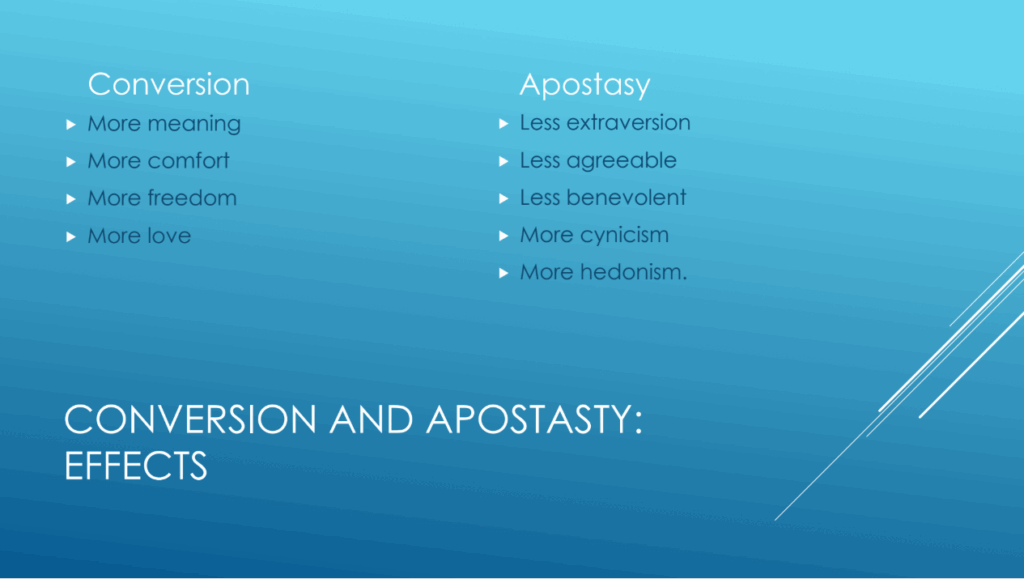

The outcomes of apostasy and conversion are also different.

Why Converts Switch Religion

“Converts perceive more meaning in life,”[16] as well as comfort, freedom, happiness, and love.[17] And this tends to follow a distinct pattern of a substantial initial increase in the first week, followed by a dip about a month out which, if persisted in, “increases again and stabilizes at an intermediately high level within 6 months following conversion.”[18]

Apostasy, on the other hand manifests a decrease in extraversion, agreeableness, and benevolence, while showing an increase in social cynicism and hedonism.[19] About half of those who apostatize experience an increase in anxiety and depression, and for about half it is the opposite.[20] Apostates tend to be less emotionally stable, and to trust people less.[21] Apostates who oppose their former religion may do so as “a way to shift blame away from self.”[22]

What this boils down to is that converts switch religion based on who they are and the conversion tends to be a positive experience causing them to feel more freedom, happiness and love. Apostasy tends to be a negative experience founded on what people do and tends to be a negative experience that causes people to be less trusting and emotionally stable, and may lead to an increase in anxiety and depression. Religion switching is a neutral term used in the social science literature but it disguises the fact that there is a difference between switching to a religion, which tends to be positive, and switching from a religion, which tends to be negative.

It does make sense to have conferences, such as this one, that focus on reducing the detrimental effects of apostasy.

Major Issues

Now if you look at the topics discussed at FAIR conferences over the years, you will find a number of intellectual issues addressed that individuals have trouble with: for example, the Book of Mormon, the Book of Abraham, the prohibition against those of African descent holding the priesthood that ended forty years ago, the practice of polygamy that ended one-hundred thirty years ago, to name but a few.

The Church has also published the Gospel Topics essays dealing with these topics. While I do not wish to minimize the importance of these topics—after all, I usually speak on one, and Elder Ballard said that we should know the Gospel Topics essays “like you know the back of your hand”[23]—a body of social science research indicates that these may not be the only intellectual issues that are corrosive to the faith of Latter-day Saints. And I want to highlight some of these corrosive issues.

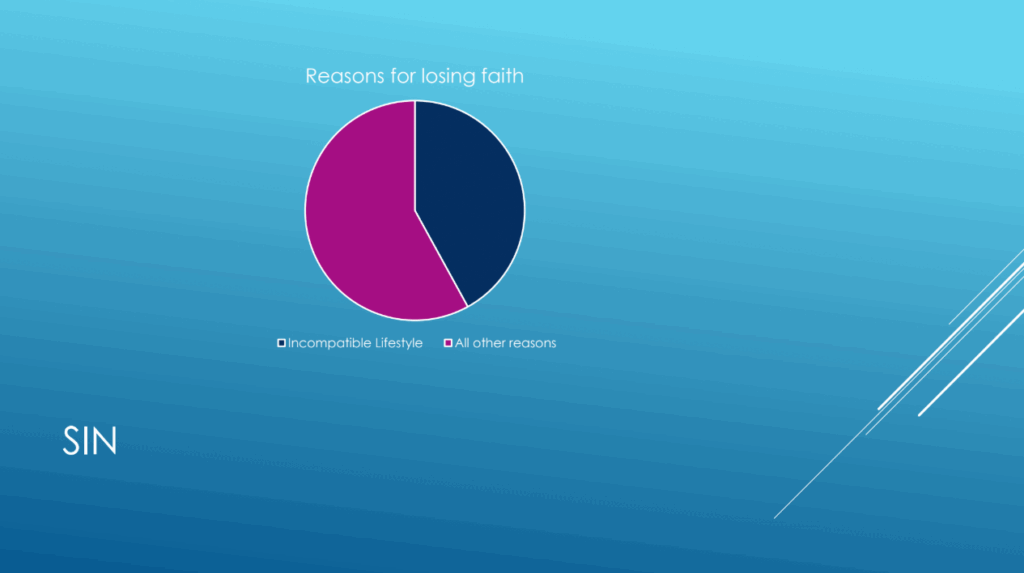

Sin

If the general research on religious switching indicates that behavior influences apostasy, then we need to look at the role that sin plays in the loss of faith. I will start by looking at two surveys of former Latter-day Saints, each of which was extremely flawed in their data gathering methods. Both surveys were started as a means of providing apologetics for those leaving the Church—that is the intent was to defend and excuse those abandoning their faith and their covenants—but both revealed something else.

In one case 42% and in another case 38% of respondents admitted that their lifestyle was no longer compatible with the teachings of the Church.[24] This was the most common reason given for abandoning faith. And we have to deal here with another issue that may be reflected in these numbers: social desirability bias. Social desirability bias occurs when individuals give answers that reflect societal expectations on them in some way rather than the truth.

Intellectual Issues

There is some social scientific literature on this subject particularly relating to Latter-day Saints. One pair of researchers determined that “Mormons and Jewish youth are clearly the least likely to give socially desirable answers” to surveys.[25] On the other hand, “less religious people are actually more hesitant to report” immoral behavior.[26] Given that these individuals have left their religion, it is likely that the numbers of those who left because their lifestyle was not compatible with Church teachings is even higher. This still does not mean that everyone who loses faith does so because of sin, but it is still a major factor that, because it shows up in about half of cases, cannot be completely removed from discussion.

A number of years ago, I heard of a former member of the Church who was disappointed because he was excommunicated for adultery when he wanted to be excommunicated for intellectual issues. I think his attitude may be typical because currently it is seen as more respectable to lose faith over intellectual issues rather than behavioral ones. So many would rather bring the intellectual component to the fore and not talk about the behavioral component.

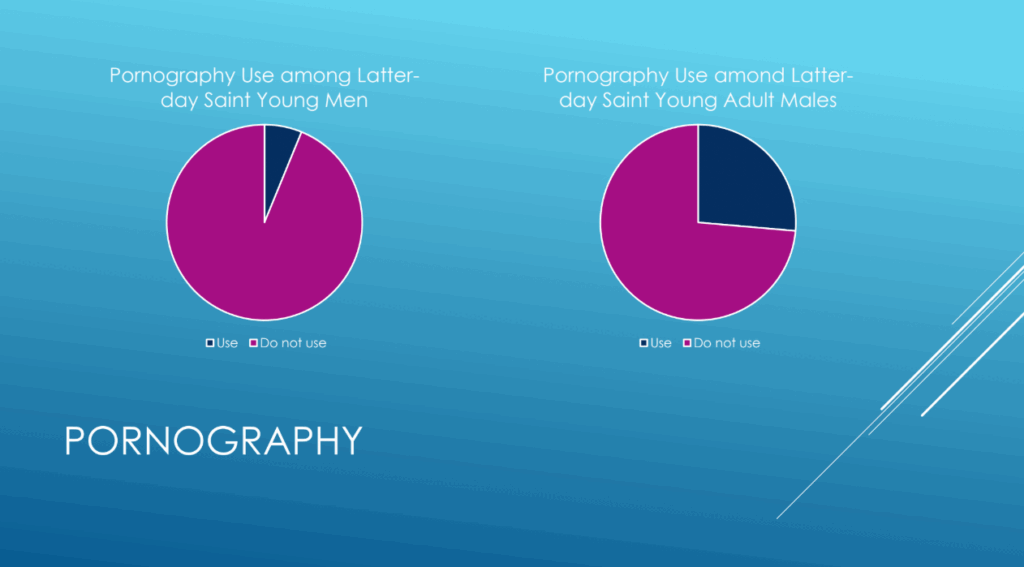

Pornography

Immoral behavior brings us to its precursor, immoral thoughts.

Estimates of pornography use among youth at large range from 7 to 98%,[27] which looks like the numbers are guesses. Among Latter-day Saints 6.2% of youth use pornography, which increases to 26.3% of young adult males.[28] Pornography has long-term deleterious effects to faith. One study found that “persons who viewed pornography reported more frequent religious doubts, lower levels of religious salience, and lower prayer frequency” six years after they viewed the pornography even if church attendance only decreased slightly.[29] Viewing pornography as a teenager correlates with decreases in service attendance, frequency of prayer, the importance of faith, closeness to God, and doubts about religion.[30] Because pornography also tends to cause a number of other side effects, these can potentially serve as indicators of this problem. These effects may include:

(2) lower grades in school,[32] (3) accepting and favoring premarital and extramarital sex,[33] (4) a shift in political views towards more liberal or progressive views,[34] (5) an acceptance of same-sex marriage,[35] (6) participation in homosexual practices,[36] (7) boredom, sadness,[37] and depression,[38] (8) decreased sexual desire and satisfaction,[39] (9) decreased happiness in marriage,[40] (10) a distancing of oneself from ones own children.[41]

Of course, pornography is not the only cause that produces some of these effects, you might be distancing yourself simply by watching your cell phone too much, and it does not necessarily produce all these effects in a particular user. But given the long term negative effects, we would be remiss not to include it in concerns.

Divorce

Another moral issue negatively impacting faith is divorce. For some less-religious or non-religious families, a divorce might encourage children to seek religion,[42] but that is more exceptional.

Parents getting a divorce doubles the chances that their children will apostatize, and triples the chances when the parents were religiously active. [43] The connection between divorce and loss of religion is so strong that some sociologists have argued that the rise of the nones, meaning those who have no religion, “may result partly from long-term increases in divorce and their impact on intergenerational solidarity and religious formation.”[44]

Social Club Members

In the gospel of Jesus Christ we are all spiritual sons and daughters of God and consequently, we are all brothers and sisters. We generally want to make each other feel welcome in the covenant. We usually love each other and get together and enjoy each other’s company. But the Church is a covenant organization not a social organization. In a longitudinal study of those who view church more as a social organization, in the next wave of the survey, nearly a quarter stopped attending (23%), or stopped believing (1%).[45] Friendship is not enough to keep people in the faith. On the other hand, whether youth like the people at Church does not predict their commitment as adults.[46] Focusing on friendship at the expense of covenant[47] is foolish.

Moralistic Therapeutic Deism

A number of counterfeits of the Gospel of Jesus Christ are also circulating among the Saints. One of these has been labeled Moralistic Therapeutic Deism. It is moralistic rather than moral because it is not concerned with being moral but having the appearance of being moral; “that means being nice, kind, pleasant, respectful, [and] responsible,” but not actually “honest, true, chaste, benevolent, [and] virtuous.”[48] It is therapeutic because it is designed to make the individual feel good about himself or herself. It is deism because it does believe in God, but in God as the cosmic butler, who comes at your beck and call and helps you out if you need him but otherwise leaves you alone.[49] This is not the God of the scriptures.

I had a conversation with someone last year where I was told that the gospel could be summed up with two words: be nice. This is completely unscriptural. The scriptures never command, exhort, or even suggest for us to be nice. Furthermore, there is some research that suggests that people who are moral and not considered nice tend to be highly religious while those who are nice and not moral tend not to be religious.[50] Niceness does not correlate with either morality or religiosity. (And as a side note, until the eighteenth century, to call someone nice would have been seen as an insult.)[51]

Relativism

Various forms of relativism also present a pernicious problem. While we all have our own point of view, truth is true regardless of one’s own point of view. If I throw an old shingle off the roof, which I used to have to do, it will fall to the ground regardless of whether I think it should soar or float.

About one third of young adults nationally are strong moral relativists.[52] And about half of them seem to want to resist relativism, but most do not know how.[53] “Six out of ten (60 percent) of the emerging adults . . . interviewed . . . said that morality is a personal choice, entirely a matter of individual decision. Moral rights and wrongs are essentially matters of individual opinion, in their view. Furthermore, the general approach associated with this outlook is not to judge anyone else on moral matters, since they are entitled to their own personal opinions.”[54] This is nationally. In some pockets things are worse: One evangelical pastor reported that for six years at the end of his catechetical classes for teenagers every pupil responded that “the deity and resurrection of Christ are . . . mere matters of personal opinion.”[55]

Judging

We have seen the rise in recent decades, and sadly in the Church of Jesus Christ, of those who claim that the greatest form of sin and intolerance is judging someone else; it is something that they will not tolerate.[56] Beyond the irony of the intolerant judging of those who are accused of judging, such claims make neither neurological[57] or scriptural sense.[58] Neurologists tell us that we judge constantly, and “Some scriptures command us not to judge and others instruct us that [we should not judge… or that] we should judge and even tell us how to do it.” For those interested in a reasoned analysis of the Church’s position on judging, I recommend the 1998 talk by President Oaks titled Judge Not and Judging,[59] which begins with the lines I have just quoted. Basically, you can oversimplify this as we do not get to decide who goes to heaven and who goes to hell but we do get to decide who and what we put our trust in in our journey there and we need to be able to judge where they will take us.

Doubt

Most of the presentations here will deal with some aspect of doubts that arise in people’s minds. If this conference is like most of these conferences the presenters will deal with various intellectual issues, and may or may not address how to respond to people’s doubts, which is what you have come to hear. Some past presenters seem not to understand the purpose of this organization and why people come here. But they will probably not deal with the question of why doubts infect some people more than others, and there is research on this topic.

The first thing to realize is that when individuals lose their faith, about half of the time they cannot articulate why they lost their faith.[60] They may not know, or cannot tell why that is the case.

When looking at why young people have a sudden loss of faith, researchers have found that doubts only play a role when other factors are in play. In other words, people do not lose their faith by doubt alone. The research shows that doubts are a factor when the following five conditions are present:

- 1) Faith is not important to the individual’s parents.

- 2) Faith is not important to the individual (or not that important.)

- 3) The individual has slackened on their prayers and scripture reading.

- 4) The individual has few adults in the congregation that he or she can turn to for help.

- 5) The individual has some doubts.[61]

Safety Net

This study was done on teenagers, but based on my own experience it seems generalizable. In this case, with the exception of doubt, all of the other factors are negative, something is missing from an individual’s life. Doubts become a problem when the individual lacks a safety net.

Now I hope that you can see the role that you play in this scenario. In some cases, you may be the parent, but you are much more likely to be in the position of the adult in the congregation that others can turn to for help. You can make a difference. Those of us who do research may be able to come up with answers and responses, but we cannot be in every ward, branch, stake, or district. And as much as we might like to help everyone who needs our help, we cannot reach them all on our own. We need you, just as you need us. You are the first line responders and may be the only thing standing between an individual and his or her loss of faith.

Next, we need to realize the major consequences of doubt. Doubts are three times more likely to cause someone to stop attending than they are to stop believing.[62]

Faith Crisis

How big a problem is doubt?

One in three Latter-day Saint young adults have at least a few doubts (33%), but only one in twenty-five (4%) have many doubts.[63] Doubts are part of the mortal condition. If we have to live on faith in this life, and if this mortal probation is to test us and to try us, then we have to expect to have occasional doubts. But those doubts need not linger, and probably will not if we do not dwell on them.

On the other hand, of the youth who have doubts who have adults in their congregations who can help them through their doubts, 60% of them end up in the highest religious category as young adults.[64] Only 0.8% of them ended up in the bottom quartile of religiosity as young adults.[65] Thus helping people through a faith crisis has a high success rate. What are you waiting for?

Voicing Doubts

Indeed, the only caveat to this deals precisely with waiting. The key, as Elder Maxwell put it, is “interven[ing] intelligently in a timely fashion.”[66] Doubt is a disease, and letting it fester without treatment can be fatal for the patient.[67] We cannot help unless we find out early enough.

President Russell M. Nelson taught that one of the first rules in medical inquiry is “Ask the patient where it hurts. The patient will be your best guide to a correct diagnosis and eventual remedy.”[68] The malignant tumor of doubt if allowed to remain and grow saps the doubter’s spiritual health. As one study put it: “At whatever point one articulates one’s doubts, one may appear to have been dissembling or hiding one’s ideas, raising questions about one’s truthfulness in both the past and the present.”[69] If people will not let you know about their doubts there is not much that you can do to help them. It’s like calling in the doctor after you have already received a Stage 4 Cancer diagnosis.

Helps for Preserving Faith

Researchers have only discovered four things that are strongly correlated with preserving faith in youth, and these are:[70]

- Daily prayer

- Weekly Church attendance

- Regular scripture reading

- Keeping the law of chastity

Though I suspect that there are other statistically relevant factors, it would be foolish to ignore the factors that we know about. One of the more important points here is that all of these are things that the individual must do for himself or herself. No one can read your scriptures vicariously for you. We have seen that these items are part of the safety net protecting people from doubt, so when in doubt, apply the safety net.

Apologetics that Do and Do Not Work

The prophets and apostles have been very clear about what type of apologetics they expect from researchers, which is probably not most of you, but some of you. A year and a half ago, Elder Holland told scholars at Brigham Young University, “We ask you as part of a larger game plan to always keep a scholarly hand fully in the face of those who oppose us.”[71]

The year before, President Dallin H. Oaks reminded the faculty at BYU that three years previously, “I encouraged BYU faculty to offer public, unassigned support of Church policies that others were challenging on secular grounds. Note that word unassigned. The Church should not have to ask or assign. The duty is inherent in the position.” After citing a comparison that Elder Maxwell made about the needs for scholars building the kingdom to be able to use both trowels and muskets, President Oaks said: “I would like to hear a little more musket fire from this temple of learning.”[72]

It needs to be simple, concrete, and credible.[73] This puts us at a disadvantage. In order to be truly credible, our arguments have to be true. And that often works against being simple and concrete. The Book of Abraham is the prime example here. Critics of the Church often propound positions that appear simple, concrete and credible, but are false. And for example, one dubious studies claims that “the only specific historical or doctrinal issue to rank among the top ten was the concern about the historicity of the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham”[74]

One of the reasons that the historical authenticity of the Book of Abraham is in question is that the answers are not simple. They are so complicated that I have seen critics so intent on undercutting certain members of the Church that they did not realize that they undercut their own argument in the process. Complicated arguments are harder for people to understand. The more complicated the argument, the harder to follow and the more likely you are to lose your audience.

Written Testimony

Arguments also need to be concrete. In direct response to Elder Holland’s talk, one individual openly disparaged the “emphasis on propositional claims”[75] claiming that “the strongest defense . . . rests on . . . that power of Jesus which is manifest to those who are not altogether devoid of perception.”[76]

These words may be stirring and eloquent but they are also hopelessly vague. They need to be concrete. To give an example of concrete: the only way now to experience the testimony of a Neal A. Maxwell, a Hugh Nibley, a Bill Hamblin, or even an Origen is not through their life but what they wrote.

On the local level, questioning individuals may or may not know something of your life and whether the power of Jesus is manifest in it, but we who do research will, for the most part, be known only by our scholarship. Needless to say scholars who publish nothing defending the Church will not even be known for that.

Arguments in defense of the Church also need to be credible. They need to be accurate and as solid as we can make them. We need to correct errors as we find them. Truth is ill-served by a bad argument.

I am told that a number of years ago, one volunteer at FAIR was constantly criticizing others at FAIR because he thought there was a problem with their tone, a subjective criterion that never seems to be defined. The research seems to indicate that we should not be overly concerned about tone.

Content Over Style

In the first place, research has shown that we are not nearly as good as we think we are in detecting tone. While most people think that they are really good at accurately detecting the tone of written works 89% of the time, in reality they are only slightly more accurate than they would be if they flipped a coin (56%).[77]

Other research on prejudice and offensive beliefs shows that “the content of belief played a much stronger role than the style of belief.”[78] What people find offensive is the content of your beliefs, not the tone in which they are expressed. Tone thus becomes a way to object to the content of beliefs without appearing to do so, a way of dismissing your opponent’s arguments without dealing with them, and a way for critics to accuse others of their own bigotry

Research also shows that those who moderate their tone tend to end up watering down their beliefs.[79] In this regard, the words of Elder Neal A. Maxwell are apropos:

We should judge the warnings given to us by their accuracy and relevancy, not by the finesse or the diplomacy by which the warnings are given. The disciple’s commitment to truth must be to truth, without an inordinate concern for the method of delivery. Of course, it takes real humility to listen under some circumstances. The Paul Reveres in our lives may have voices too shrill, use bad grammar, ride a poor horse, and may pick the oddest hours to warn us. But the test of warnings is their accuracy, not their diplomacy.”[80]

Do not be overly concerned about your eloquence at the cost of your accuracy.

Accuracy

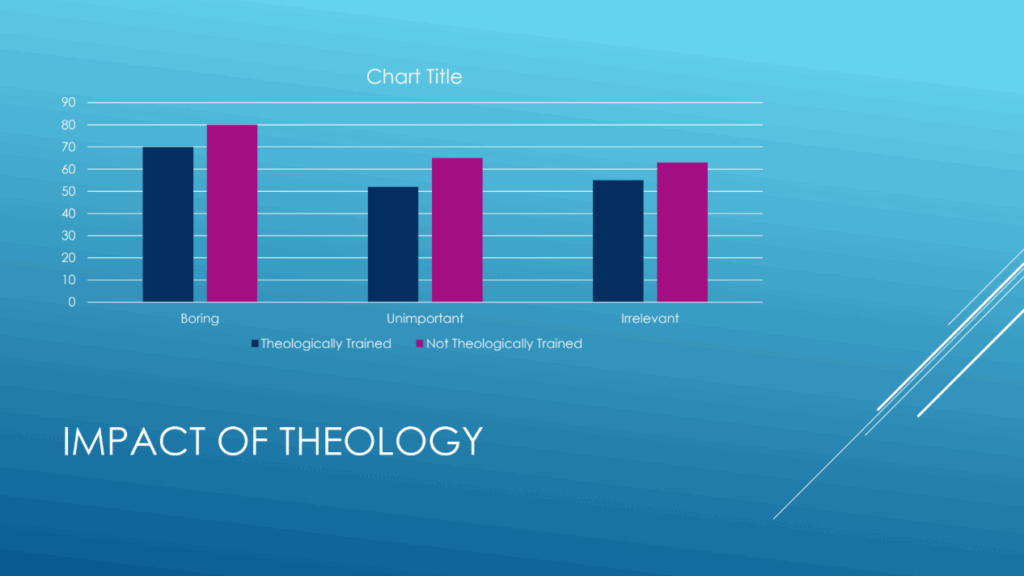

Theology, the systematic study of divine things without the aid of revelation, has been promoted by some as an effective response to criticism.

A study, however, of the impact of theological education found that more than half of those with theological training found theology boring, unimportant, and irrelevant to their lives and among those without theological training the numbers only went up.[81] Unfortunately, the study did not measure the impact of theology on the faith of those who was taught it, but given that those receiving that training thought it was unimportant and irrelevant, it would be difficult to argue for effectiveness.

The religious studies approach is also not helpful. Doing comparative religious studies strikes most people of faith as blasphemous.[82] It is a two-edged sword as it either “results in dilution of traditional religious commitments or production of stronger boundaries.”[83] It is therefore worth remembering where and what the boundaries are. They need to be recognized, maintained, policed, and defended.

Hope for Return

Social science research on return to faith is harder to come by, and here are some things that might give you some hope.

The first is that unbelief is the least stable of all religious categories.[84] There are even those who have argued that we are neurologically wired to believe.[85] If young single adults constitute a category that is most likely to fall into inactivity or disbelief, marriage and child-birth are the events most likely to trigger a return to faith.[86] Communication with parents and trusting parents are two conditions that correlate with returning to faith.[87] The family normally plays a stronger role on children’s behavior and religious experience than anything else. “The greatest predictor of the religious lives of youth is the religious lives of their parents.”[88]

Religiously Active Social Circle

“Nones [those who subscribe to no religion,] whose social contacts included religiously active peers were more likely to believe in God; but only 1 in 5 Nones had such friends.”[89] “Nones whose mothers and fathers did not attend religious services regularly were more likely to affirm atheist or agnostic views than Nones whose mothers and fathers did attend regularly. And Nones whose mothers and fathers did not attend religious services regularly were also more likely to disbelieve in heaven than Nones whose mothers and fathers did attend religious services regularly.

In short, religiously active parents, like religiously active friends, make a difference.”[90] One thing that appears to influence individuals to come back to faith and faithfulness is for friends and family to remain faithful.

When faith was originally borrowed into the English language it meant not belief but loyalty. Thus faith in Jesus Christ also entails loyalty to Jesus Christ. When family members fall away, we need to remain loyal to Jesus Christ. Yes, we still love our family members, but as Jesus told us: “He that loveth father or mother more than me is not worthy of me: and he that loveth son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me. And he that taketh not his cross, and followeth [not] after me, is not worthy of me.” (Matthew 10:37–38)

Conclusions

Defending the faith takes two types of people: researchers and local people. The job of the researcher is to confront the arguments and deal with them. To rebut them, refute them, diffuse them, whatever necessary. But no matter how we write about them, nearly half of our readers will misinterpret our tone. But while researchers should, at least occasionally, work with individuals on a one-on-one basis, we cannot work with everyone. We need people like you to take the information and help those around you who need it.

Defending the faith generally has really good results. A majority of those who work through their doubts come out with stronger faith. The exceptions to this are: First, those whose lifestyles are no longer compatible with the teachings of the Church. This is known as cognitive dissonance, where one’s behavior is incompatible with one’s beliefs. The usual course for those with cognitive dissonance is to change one’s beliefs to coincide with one’s behavior, not the other way around. When the behavioral component is not addressed, the intellectual component usually cannot be.

Second, those who stew too long in their doubts before getting help. Like ceviche, they have marinated in the acids of their doubts so long that they are already done without even being cooked.

Final Sound Bites

So if you want some sound bites to sum this up, the data do not indicate that the Church is losing youth in droves. There is a difference between apostasy from and conversion to a religion; they are not different sides of the same coin. Prevention and retention are easier than reclamation. The biggest reasons that people leave the Church are behavioral rather than intellectual.

While we appropriately focus on the material in the Gospel Topics Essays, other intellectual issues may loom larger in creating doubts. God is not your butler or your buddy. The Church is not a social club. And you do not get to define truth or have your own version of it. Prayer, reading scriptures, attending Church, and keeping the commandments make a big difference, and should be the first line of defense and first course of treatment. And if you want your loved ones to return to the faith, then you need to be grounded in your faith and covenants and not compromise them.

None of this is particularly new, or ground-breaking, or earth-shattering. When tremors of doubts ripple through lives, you do not want to be earth-shattering. You want to be solid, grounded, rooted, settled, established, built on the rock of your Redeemer, Jesus Christ, whose Church this is, and in whose work we are all hopefully engaged. And may God bless you in your efforts to defend it.

Audience Q&A

Scott Gordon:

Okay, thank you for that talk. My first comment is, I think most people expect you to come and talk about the “Eye of Ra” or something along those lines, and there’s probably a lot of people out there surprised that you’d be talking about sociology and those types of things. How did you stumble into this line?

John Gee:

Well, I actually tell the story in the preface to my book. But, basically it was from watching General Conference in 2005. In the priesthood session President Hinckley cited a study, and I thought this sounds interesting, I’d like to look at it. So I got the book and I read it, and I said this is really interesting stuff. And so for years I followed these studies and looked at some other information. But I was mainly doing it as a father, and thinking I’ve got kids and I want them to keep the faith. What do I need to be doing? What do I need to be looking for? What do I need to watch out for? And, I won’t go through, here, all of the story, that’s in the preface of how this ended up as a book.

And I thought I would pull the information that is most applicable to the people who go to this conference, who are interested either in defending their own faith, defending the faith of those that they love, defending the faith of those in their congregations. What would be the most useful information that I have come across that would help them?

Scott Gordon:

So how are we going to respond to those who are going to skim over the first part of your presentation and say John Gee is just attacking us because he believes that you leave the Church if you sin?

John Gee:

Well, what I’m saying here, and I cited studies that were designed by people who want to defend those who were leaving the Church. But they point out that nearly half of those who did, in their study, did so because their lifestyle isn’t compatible. So, even if we take the lowball, even if a third, and the smallest number was actually larger than that, even if a third of the people are leaving because of their lifestyle, then we can’t take that out of the equation as much as we might like to. I would rather not discuss their sins; they can discuss that with their bishop. But to ignore the role that that plays is to skew both our approach and our results and the data that we’re working with.

And I know people who didn’t leave because of sin. They do exist. So we can’t say that that works in every case. But to take it out of the equation is to take one of the major factors out of the discussion. And it distorts our view of how we deal with it. So as much as I might like to avoid the topic, I usually deal with intellectual topics, we can’t ignore the topic.

Scott Gordon:

That makes sense. So, next question says to what do you attribute some of the differences between your findings and those by Jana Riess and her 2019 book ‘The Next Mormons,’ for example, you indicate that people leave the Church over behavioral issues at a higher rate than she does.

John Gee:

Well, I talked about social desirability bias. There are a number of studies out there; she indicates that it’s a major issue, you know, and there are different studies that cite different results. But all of the ones that I’ve seen, it’s between a third and half, even Jana Riess’, so we can’t ignore the problem. I have a review of Jana Riess’ work; I think there are some problems in the way she gathered her data and how she interpreted it. There were some things that she says she was surprised at which I think if she looked further in the literature, she wouldn’t have been so surprised at. There are some good things in her study, but it’s one that I find that I can’t use uncritically.

Scott Gordon:

Okay, very good. Here’s an interesting question: How has your work in Egyptology influenced your work on this social science topic?

John Gee:

If you read my book, you will see a couple of places where it pops up. I can’t think of any sociologists who would cite an ancient Egyptian proverb, which I do. But actually, there’s the flip side of this because I’ve done a paper that I’ve submitted to an Egyptological venue where I actually, because the topic came up, I pull in the modern sociology before I look at the ancient Egyptian evidence to give an idea of what you look for in the modern world and what we might be looking for in the ancient world. So yes, it has bled a little bit in both directions.

Scott Gordon:

So if someone wanted to find out more about this, what is the name of your book again?

John Gee:

The book is called Saving Faith, and it came out in May from the Religious Studies Center and Deseret Book. So, it’s available on, I checked, it’s listed on the Fair bookstore app, it was there this morning. It’s also available at Deseret Book, it’s available at Amazon, all of the usual places. I’m sure that given this is the Fair conference, we would prefer them having to buy it from the Fair bookstore because that way some of the proceeds will contribute to the marvelous studio that we have here that we’ve been able to do this conference in, and also the ongoing work of providing answers.

Scott Gordon:

We do have the book in stock. I also should comment that your last book just flew off the shelves,

John Gee:

Well, The Introduction to the Book of Abraham I understand is still in print so you can order that too.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you for your time and we’ll see you again, I’m sure.

John Gee:

Thank you for the invitation to come. Thank you all for attending, virtually or in person, and I wish you the best in your efforts to spread the gospel and to save and preserve faith.

Endnotes & Summary

In “By the Numbers: Saving Faith,” Egyptologist John Gee takes a data-driven approach to understanding apostasy and retention in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Drawing on over 300 social science studies, Gee argues that behavioral issues—such as sin, pornography use, divorce, and moral relativism—play a far more significant role in faith crises than intellectual doubts. He emphasizes that early, supportive intervention by trusted adults greatly increases the likelihood that struggling individuals will remain faithful. Gee critiques the common overemphasis on tone and intellectual argumentation in apologetics and instead recommends responses that are truthful, concrete, credible, and timely. He concludes with hope: most who work through their doubts emerge stronger, and faith—when supported by daily spiritual practices and community—is both resilient and restorable.

- [1] Bruce C. Hafen, A Disciple’s Life: The Biography of Neal A. Maxwell (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002), 427-28.

- [2] Hafen, A Disciple’s Life, 427.

- [3] Hafen, A Disciple’s Life, 426.

- [4] John Gee, Saving Faith (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, 2020).

- [5] Boyd K. Packer, “The Father and the Family,” General Conference April 1994.

- [6] Gee, Saving Faith, 1, 24.

- [7] Gee, Saving Faith, 21.

- [8] Jeffrey M. Jones, “U.S. Church Membership Down Sharply in Past Two Decades,” accessed November 2, 2019, https://news.gallup.com/poll/248837/ church-membership-down-sharply-past-two-decades.aspx.

- [9] Stephen Cranney, “Who Is Leaving the Church? Demographic Predictors of Ex–Latter-day Saint Status in the Pew Religious Landscape Survey,” BYU Studies 58/11 (2019): 101.

- [10] John Gee, “Conclusions in Search of Evidence,” Interpreter 34 (2020): 173-74.

- [11] Alma 42:8, 16.

- [12] Gee, Saving Faith, 34-35.

- [13] Mark D. Regnerus and Jeremy E. Uecker, “Finding Faith, Losing Faith: The Prevalence and Context of Religious Transformations during Adolescence,” Review of Religious Research 47/3 (2006): 231.

- [14] Regnerus and Uecker, “Finding Faith, Losing Faith,” 231-32.

- [15] Gee, Saving Faith, 36.

- [16] Raymond F. Paloutzian, “Purpose in Life and Value Changes Following Conversion,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 41/6 (1981): 1157.

- [17] Paloutzian, “Purpose in Life and Value Changes Following Conversion,” 1153.

- [18] Paloutzian, “Purpose in Life and Value Changes Following Conversion,” 1157-58.

- [19] C. Harry Hui, Sing-Hang Cheung, Jasmine Lam, Esther Yuet Ying Lau, Shu-Fai Cheung, Livia Yuliawati, “Psychological Changes During Faith Exit: A Three-Year Prospective Study,” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 10/2 (2018): 108.

- [20] Hui, Cheung, Lam, Lau, Cheung, Yuliawati, “Psychological Changes During Faith Exit,” 114.

- [21] Hui, Cheung, Lam, Lau, Cheung, Yuliawati, “Psychological Changes During Faith Exit,” 115.

- [22] Adam R. Fisher, “A Review and Conceptual Model of the Research on Doubt, Disaffiliation, and Related Religious Changes” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 9/4 (2017): 363.

- [23] https://www.lds.org/broadcasts/article/evening-with-a-general-authority/2016/02/the-opportunities-and-responsibilities-of-ces-teachers-in-the-21st-century:

- [24] William S. Bradshaw, Tim B. Heaton, Ellen Decoo, John P. Dehlin, Renee V. Galliher, and Katherine A. Crowell, “Religious Experiences of the GBTQ Mormon Males,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54/2 (2015): 313; Jana Riess, The Next Mormons (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 223-24.

- [25] Mark D. Regnerus and Jeremy E. Uecker, “Religious Influences on Sensitive Self-Reported Behaviors: The Product of Social Desirability, Deceit, or Embarrassment?” Sociology of Religion 68/2 (2007): 153.

- [26] Kyler R. Rasmussen, Joshua B. Grubbs, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Julie J. Exline, “Social Desirability Bias in Pornography-Related Self-Reports: The Role of Religion,” The Journal of Sex Research 55/3 (2017): 389.

- [27] Gee, Saving Faith, 99.

- [28] Gee, Saving Faith, 100.

- [29] Samuel L. Perry, “Does Viewing Pornography Diminish Religiosity over Time? Evidence from Two-Wave Panel Data,” Journal of Sex Research 54/2 (2017): 220–21; Aaron M. Frutos and Ray M. Merrill, “Explicit Sexual Movie Viewing in the United States according to Selected Marriage and Lifestyle, Work and Financial, Religion and Political Factors,” Sexuality & Culture 21 (2017): 1075; Gee, Saving Faith, 102.

- [30] Samuel L. Perry and George M. Hayward, “Seeing Is (Not) Believing: How Viewing Pornography Shapes the Religious Lives of Young Americans,” Social Forces 95/4 (2017): 1757–88; Gee, Saving Faith, 102.

- [31] Peter and Valkenburg, “Adolescents and Pornography,” 521; Doornwaard, van den Eijnden, Overbeek, and ter Bogt, “Differential Developmental Profiles of Adolescents Using Sexually Explicit Internet Material,” 270; Koletić, “Longitudinal associations between the use of sexually explicit material and adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors,” 126.

- [32] Doornwaard, van den Eijnden, Overbeek, and ter Bogt, “Differential Developmental Profiles of Adolescents Using Sexually Explicit Internet Material,” 270; Koletić, “Longitudinal associations between the use of sexually explicit material and adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors,” 128.

- [33] Zitzman and Butler, “Wives’ Experience of Husbands’ Pornography Use,” 216-17; Wright, “U.S. Males and Pornography,” 66; Peter and Valkenburg, “Adolescents and Pornography,” 519-20; Doornwaard, van den Eijnden, Overbeek, and ter Bogt, “Differential Developmental Profiles of Adolescents Using Sexually Explicit Internet Material,” 269–70; Frutos and Merrill, “Explicit Sexual Movie Viewing in the United States,” 1066, 1076; Koletić, “Longitudinal associations between the use of sexually explicit material and adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors,” 126-27.

- [34] Regnerus, Cheap Sex, 123-24; Frutos and Merrill, “Explicit Sexual Movie Viewing in the United States,” 1075, 1078.

- [35] Regnerus, Cheap Sex, 125; Frutos and Merrill, “Explicit Sexual Movie Viewing in the United States,” 1075, 1078.

- [36]

- [37] Regnerus, Cheap Sex, 127.

- [38] Newstrom and Harris, “Pornography and Couples,” 417-18; Brown, Durtschi, Carroll, and Willoughby, “Understanding and predicting classes of college students who use pornography,” 114.

- [39] Perry, “Does Viewing Pornography Reduce Marital Quality Over Time?” 550; Peter and Valkenburg, “Adolescents and Pornography,” 521; Koletić, “Longitudinal associations between the use of sexually explicit material and adolescents’ attitudes and behaviors,” 126-27; Brown, Durtschi, Carroll, and Willoughby, “Understanding and predicting classes of college students who use pornography,” 114.

- [40] Perry, “Does Viewing Pornography Reduce Marital Quality Over Time?” 551, 553; Frutos and Merrill, “Explicit Sexual Movie Viewing in the United States,” 1076; Perry, “Pornography Consumption as a Threat to Religious Socialization,” 439.

- [41] Chisholm and Gall, “Shame and the X-rated Addiction,” 260; Perry, “Pornography Consumption as a Threat to Religious Socialization,” 440.

- [42] Melinda Lundquist Denton, “Family Structure, Family Disruption, and Profiles of Adolescent Religiosity,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51/1 (2012): 54–60; Gee, Saving Faith, 81-82.

- [43] Hsien-Hsein Lau and Nicholas H. Wolfinger, “Parental Divorce and Adult Religiosity: Evidence from the General Social Survey,” Review of Religious Research 53/1 (2011): 95, 93, 92; Jeremy E. Uecker and Christopher G. Ellison, “Parental Divorce, Parental Religious Characteristics, and Religious Outcomes in Adulthood,” Journal of the Scientific Study of Religion 51/4 (2012): 786-88; Gee, Saving Faith, 80.

- [44] Christopher G. Ellison, Anthony B. Walker, Norval D. Glenn, and Elizabeth Marquardt, “The Effects of Parental Marital Discord and Divorce on the Religious and Spiritual Lives of Young Adults,” Social Science Research 40 (2011): 549; Gee, Saving Faith, 19.

- [45] Lisa D. Pearce and Melinda Lundquist Denton, A Faith of Their Own (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 101; Gee, Saving Faith, 52-53.

- [46] Christian Smith and Patricia Snell, Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 219; Gee, Saving Faith, 32.

- [47] J. Spencer Fluhman, “Friendship,” Mormon Studies Review 1 (2014): 6–7.

- [48] Article of Faith 1:13.

- [49] Christian Smith and Melinda Lundquist Denton, Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 162-63.

- [50] Lazar Stankov and Jihyun Lee, “Nastiness, Morality and Religiosity in 33 Nations,” Personality and Individual Differences 99 (2016): 56–66.

- [51] Gee, Saving Faith, 127.

- [52] Smith et al., Lost in Transition, 29.

- [53] Smith et al., Lost in Transition, 33.

- [54] Smith et al., Lost in Transition, 21.

- [55] Ron Sider, The Scandal of the Evangelical Conscience (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2005), 91; Gee, Saving Faith, 159.

- [56] D. A. Carson, The Intolerance of Tolerance (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012), 11-12; Gee, Saving Faith, 139.

- [57] Carmen Simon, Impossible to Ignore (New York: McGraw Hill, 2016), 214–25

- [58] Gee, Saving Faith, 133-38.

- [59] https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/dallin-h-oaks/judge-judging/

- [60] Gee, Saving Faith, 62-63.

- [61] Gee, Saving Faith, 63-64.

- [62] Gee, Saving Faith, 63.

- [63] Gee, Saving Faith, 63.

- [64] Smith and Snell, Souls in Transition, 221; Gee, Saving Faith, 66.

- [65] Smith and Snell, Souls in Transition, 221.

- [66] Neal A. Maxwell, A More Excellent Way: Essays on Leadership for Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1967), 53.

- [67] Gee, Saving Faith, 67-70.

- [68] Jeffrey R. Holland, “Witnesses Unto Me,” General Conference April 2001.

- [69] John D. Barbour, Versions of Deconversion: Autobiography and the Loss of Faith (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994), 106.

- [70] Gee, Saving Faith, 231-33.

- [71] Holland, “The Maxwell Legacy in the 21st Century,” 14.

- [72] Dallin H. Oaks, “Challenges to the Mission of Brigham Young University,” https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/dallin-h-oaks/challenges-mission-brigham-young-university/

- [73] Chip Heath and Dan Heath, Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die (New York: Random House, 2007), 25-62, 98-164.

- [74] Jana Riess, The Next Mormons: How Millennials Are Changing the LDS Church (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 233.

- [75] Terryl Givens, “Apologetics and Disciples of the Second Sort” in BYU Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship Annual Report 2019 (Provo, Utah: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2020), 45-46.

- [76] Terryl Givens, “Apologetics and Disciples of the Second Sort” in BYU Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship Annual Report 2019 (Provo, Utah: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2020), 43.

- [77] Justin Kruger, Nicholas Epley, Jason Parker, and Zhi-Wen Ng, “Egocentrism over E-Mail: Can We Communicate as Well as We Think?,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89/6 (2005): 926, 928; Gee, Saving Faith, 11-12.

- [78] Mark J. Brandt and Daryl R. Van Tongeren, “People Both High and Low on Religious Fundamentalism Are Prejudiced Toward Dissimilar Groups,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 112/1 (2017): 85, 93-94; Gee, Saving Faith, 144.

- [79] Brandt and Van Tongeren, “People Both High and Low on Religious Fundamentalism,” 93-94; Gee, Saving Faith, 144.

- [80] Neal A. Maxwell, Wherefore, Ye Must Press Forward (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1977).

- [81] Christian Smith, Kyle Longest, Jonathan Hill, and Kari Christoffersen, Young Catholic America: Emerging Adults In, Out of, and Gone from the Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 262; Gee, Saving Faith, 245.

- [82] Gee, Saving Faith, 246.

- [83] Grace Yukich and Ruth Braunstein, “Encounters at the Religious Edge: Variation in Religious Expression across Interfaith Advocacy and Social Movement Settings,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53/4 (2014): 791; Gee, Saving Faith, 88.

- [84] Gee, Saving Faith, 256.

- [85] Robert N. McCauley, Why Religion is Natural and Science is Not (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- [86] Gee, Saving Faith, 257-58.

- [87] Gee, Saving Faith, 258.

- [88] Melinda Lundquist Denton, “Family Structure, Family Disruption, and Profiles of Adolescent Religiosity,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51/1 (2012): 43

- [89] Tim Clydesdale and Kathleen Garces-Foley, The Twenty-something Soul: Understanding the Religious and Secular Lives of American Young Adults (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 152.

- [90] Clydesdale and Garces-Foley, The Twenty-something Soul, 153-54.

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 6,2020

- Duration: 49:52 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2020 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: Faith crises, Apostasy, Conversion, Behavioral influences on faith, Pornography and religiosity, Divorce and religious disaffiliation, Moral relativism, Social club mentality in church, Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, Doubt and spiritual resilience, Youth retention, Parental influence on faith, Apologetics strategies, Effectiveness of Church defense, Correlation Research Division, Tone in apologetics, Religious switching, Returning to faith, Cognitive dissonance, Church attendance, Scripture study, Prayer, Law of chastity, Social science in religious studies, Theology vs. revelation, Relational support in faith crises

Common Concerns Addressed

People leave the Church due to intellectual issues.

Research shows behavior (e.g., lifestyle conflicts) is a more common driver.

Doubt alone causes faith crises.

Doubt only destabilizes faith when paired with disconnection from spiritual habits and support.

Tone determines whether apologetics are effective.

Content, not tone, influences belief retention.

Apologetic Focus

Reframing apologetics to prioritize credibility over eloquence.

Addressing behavioral patterns alongside doctrinal questions.

Advocating early, faithful intervention in faith crises.

Explore Further

coming soon…

Share this article