Summary

Jeffrey Thayne explores how Jesus Christ provides a foundation for Christian apologetics. Thayne argues that understanding Jesus as the “Truth made flesh” allows believers to address contemporary challenges to the faith, emphasizing the relational and transformative aspects of Christian doctrine. He discusses how this perspective can be applied to defend the faith against modern philosophical and cultural critiques, encouraging a deeper engagement with both theology and apologetics.

This talk was given at the 2020 FAIR Annual Conference on August 5, 2020.

Dr. Jeffrey Thayne holds a doctorate in psychology from BYU and specializes in worldview analysis and apologetics. He is dedicated to exploring how values shape faith and gospel living. He runs an active practice and frequently speaks and writes on psychology, faith, and culture.

Transcript

Introducing Jeffrey Thayne

Scott Gordon: Our next speaker is Jeffrey Thayne. Jeffrey has a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree from BYU, and his Ph.D. is from Utah State University. He runs the popular Letter to Saint Philosopher’s blog, and he has written an amazing book. I’ve never been shy about the fact that philosophy is not my thing. It’s not something I’ve often been interested in, but when I picked up his book and started reading it, I was immediately engaged and just had to say ‘wow’. So, I’m looking forward to Jeffrey’s talk, and with that, I will turn the time over to Jeffrey Thayne.

World View Apologetics

My name is Jeffrey Thayne, and I do what some might call world-view apologetics. Rather than focusing on the historical details of the restoration or the Book of Mormon, as vitally important as those things are, I’m interested in the foundational worldviews that inform our faith, our convictions, and our doubts. As apologists, we spend a lot of time exploring questions. Questions never form in a vacuum and are always informed by premises. Many of those premises are invisible to the person asking the questions, like the air that we breathe.

We often have very little idea what various worldviews are shaping our faith, our questions, our doubts, our convictions, and so forth. Those worldviews can be philosophical; they can be cultural, political, theological. We can absorb them from our cultural and intellectual zeitgeist without ever even knowing it. We can also embrace them knowingly but without realizing that there are alternatives. Whatever the case may be, these worldviews invariably frame the questions that we ask.

So here are some examples of questions that I’ve encountered from friends, family, and acquaintances.

Question Examples

For example, if temple rituals were revealed by God, why have they changed over the past 150 years? If prophets teach truth, then why did earlier prophets teach things that are disavowed by current prophets? Why does the Church emphasize “backwards and dated” beliefs on gender and marriage? If the temple teaches truth, why do we not broadcast what we do there to the world? These are just a few.

There’s an endless well of questions like this that I’ve encountered, and each of them carries a number of worldview assumptions that can be interrogated and challenged, and many of those, most of those, are beyond the scope of today’s presentation. Today, I argue that all these questions and many more, embrace the same modernist understanding of truth, and that there is an alternate way to think about truth.

Now, I want to be clear that this alternative way to think about truth doesn’t make these questions disappear, but it does change the way we think about them, and I think this alternative way of thinking about truth invites us to ask different questions instead – questions that tilt us towards faith and fidelity instead of doubt. So let me jump right in.

Christ is Literally the Truth

Nearly 2,000 years ago, Jesus Christ was asked by His followers, “How can we know the way?” Christ’s reply was simple and profound: “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” Christ did not say, “I know the truth” or “what I teach is truth.” He said, “I am the truth.” This is a bold declaration. My presentation today hinges on the question: What if we take this literally? What does this imply about how we understand our faith?

I’m not the first to ask this. James Faulconer wrote, ‘Suppose that we take the claim that Christ is the truth made flesh quite seriously, not immediately dismissing it as metaphor.’ Then the path and the truth and the force of life are the same thing in Jesus.

Richard Williams, the former director of the Wheatley Institution at BYU, said something similar. He said, “The truth, the word, the understanding, the message from God comes to us not as a principle or as, I might put, a set of ideas, but as a person.“

Now, my co-author, Dr. Ganta, and I owe a great debt to Dr. Brent Slife and Dr. Jeffrey Reber, who are both former psychology professors at BYU, and I want their names up here big and bold for just a moment because we owe almost everything that we do to them. They are the ones that introduced me to these distinctions, and the following concepts are inspired by their work. Dr. Ganta and I have merely expanded upon these ideas and applied them to an apologetic context.

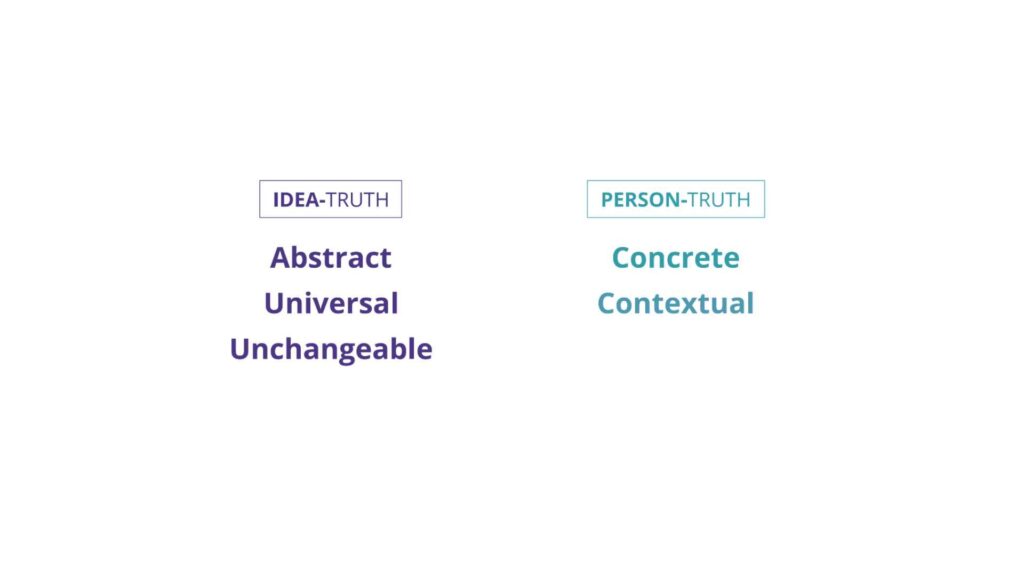

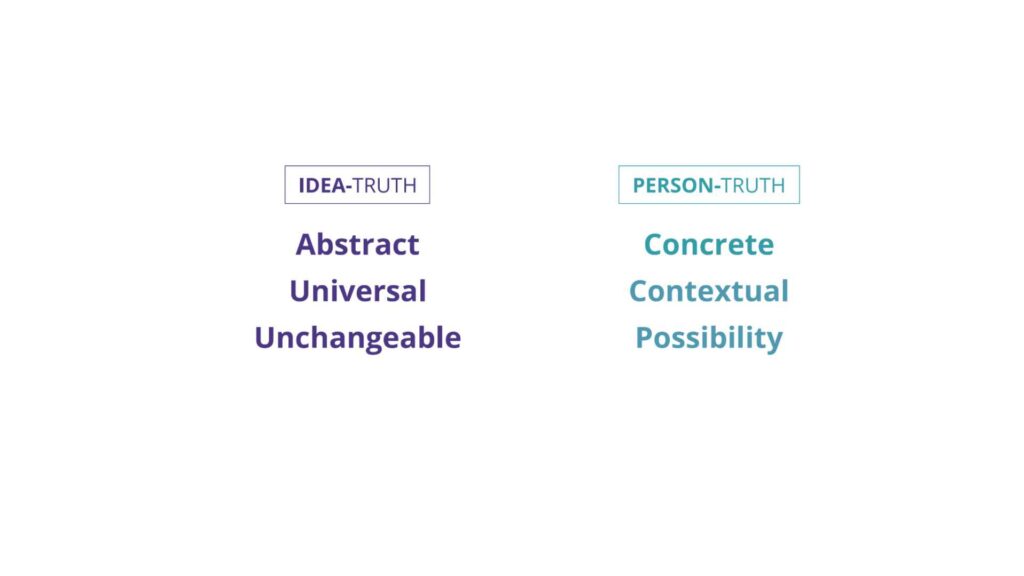

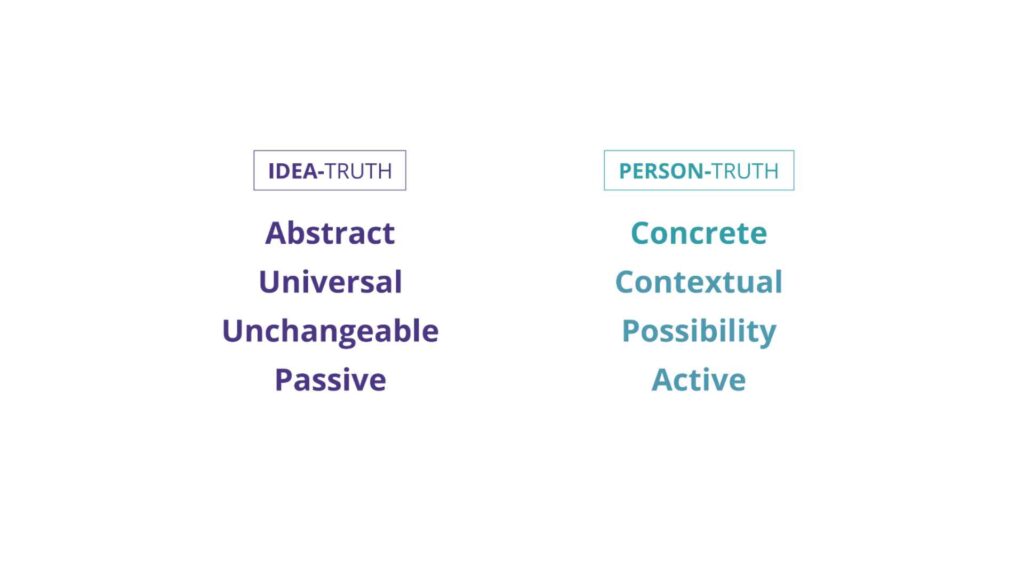

Idea Truth vs. Person Truth

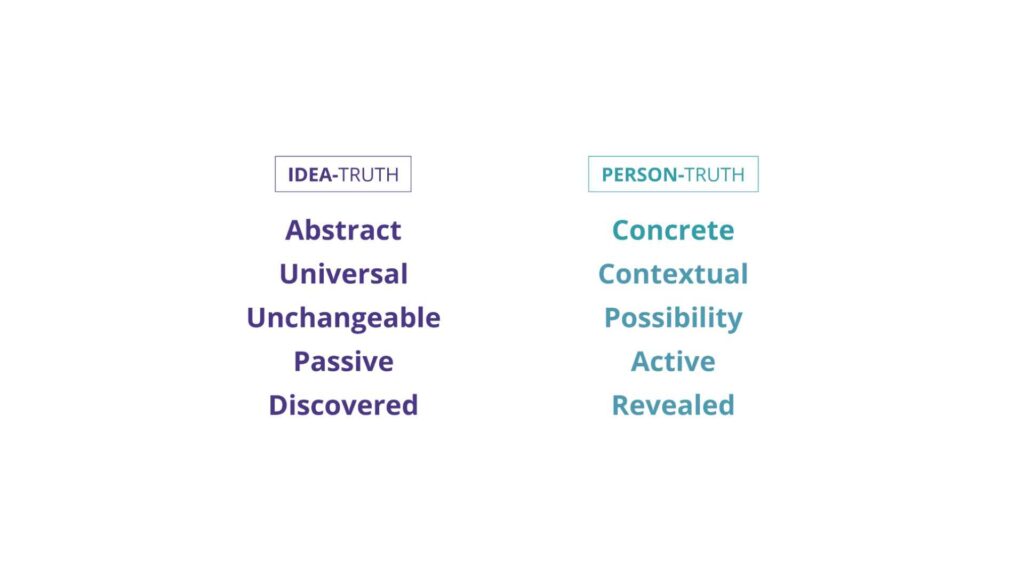

For millennia, philosophers have wrestled with the question, “What is truth?” The question itself presumes that truth is a thing, a what. Most of us see truth as a series of ideas that we grasp with our minds and store in our memory. From this view, we know truth when we have the right set of ideas about the world. I call this the Idea View of truth or Idea Truth. In contrast, what if truth is not a set of ideas but a divine person, a being of flesh and blood and incomparable love? I call this the Person View of truth or Person Truth. And as a twist on the question before, Dr. Ganta and I have named our book Who is Truth to illustrate this distinction. Let’s compare and contrast.

Idea Truth is best expressed as a set of abstract ideas. We cannot see, hear, taste, or smell the underlying order of the universe, so we can only talk about it abstractly. Abstract ideas describe a pattern we might observe in the world, such as “it is always wrong to kill an innocent person” or “the circumference of a circle is twice the radius times pi.”

These abstract statements make claims about the underlying order of the universe, and they can be a moral principle, a mathematical theorem, or a law of nature. In contrast, Person Truth is concrete. You can see truth, hear truth, and even touch truth. As Christ told His frightened apostles, “Behold my hands and my feet, that it is I myself; handle me, and see; for a spirit hath not flesh and bones, as ye see me have.” And I would add, neither does an abstraction.

Weep With You

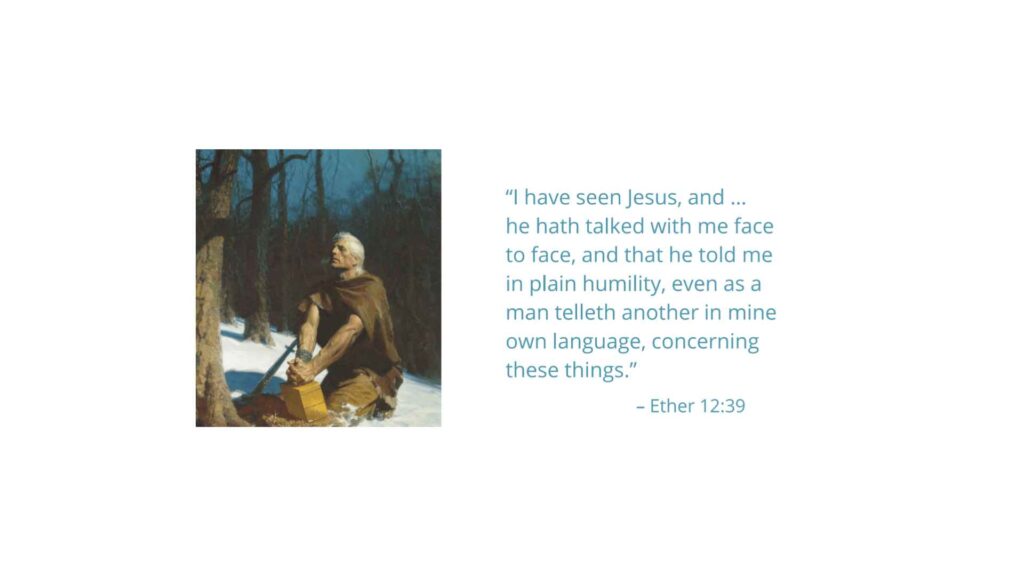

Moroni wrote, “I have seen Jesus. He hath talked to me face to face, and He hath told me in plain humility even as a man telleth another in my own language concerning these things.” That is not something the Pythagorean theorem can do. This verse illustrates the concreteness of personified truth in Christ Jesus. Furthermore, from an Idea View of truth, we can discover scientific laws or universal moral maxims and admire their intellectual elegance, but we could never call them friends except perhaps metaphorically. In contrast, Person Truth can love you, embrace you, and even weep with you.

Eight years ago, Terryl Givens invited us to consider the implications of a God who weeps. Today, I’d like to invite us to consider the implications of a Truth who weeps.

Idea Truth

Idea Truth is also seen as universal. Setting aside postmodernism, at least from a modernist view, not all facts are capital “T” truth. Truth consists of the facts that transcend the particularities of history, culture, and experience. Idea truth cannot just be true for us here and now; it must be true everywhere and anywhere, as well as any time and every time. Statements that fall short of the standard are merely facts to be explained by truths that do transcend context. Furthermore, when we write what we know about the law of gravity or the categorical imperative on paper, our expression of these truths exists in a specific place and time. But the law of gravity and the categorical imperative themselves have no time or place; they are everywhere and yet nowhere at all.

If that sounds familiar to anyone listening. In contrast, Person Truth, the resurrected Christ, visited a young man named Saul one morning on the side of a road between Jerusalem and Damascus, and a young man named Joseph in a grove of trees in upstate New York. In these examples, Truth was in a particular place at a particular time, saying and doing particular things with a particular person. The implications of this are far-reaching: truth can exist within our context and address the particulars of our place and time.

Terryl Givens wrote, “In the Book of Mormon, prayer frequently and dramatically evokes an answer that is impossible to mistake as anything other than an individualized dialogic response to a highly particularized question.” Because of this, God’s instructions cannot always be reduced to universal maxims. God can institute different laws for different dispensations or even within the same dispensation as the social, cultural, and historical context change. God can dwell with us in the here and now, and His instructions extend far beyond mere timeless abstractions.

Changeableness and Truth

From the Idea View of truth, truth cannot be different than what it is. It represents not just what is the case but what must be the case. In other words, ultimate truth is not just unchanging; it is unchangeable. I’m going to draw a connection here between Idea Truth and Greek philosophy, but I want to add the caveat that Idea Truth is not the same thing as Greek philosophy. We just see some of the assumptions of Greek philosophers embedded in our understanding of the modernist understanding of truth.

James Faulkner wrote,

The Greeks believed that change is a defect, that whatever is ultimate must be static and immobile. What changes, including the world that we experience, is of a lesser order than what does not change. For the ancient Greeks, the genuine truth seeker sifts through the dynamic variety of life and extracts from the world of chaos and change whatever is the same in every place, every time, in every context.”

For inheritors of Greek traditions and swimming as we are in a modern worldview, it makes sense for us to seek stability in the terms of unchanging universals.

His Character

In contrast, Person Truth is unchangingly reliable, but this reliability is expressed in more relational terms rather than philosophical terms. God’s reliability is a matter of His character – that is who He is and who He chooses to be. Noel Reynolds wrote that Hebrew thought, in contrast with Greek, places emphasis on covenant as a means of establishing stable expectations in a changing world. God is reliable because He has made covenants with us and is true to those commitments, not because His instructions cannot change across time and place.

But perhaps more relevant, this means that the instructions of God may be subject to possibility.

For example, the ordinance of baptism holds tremendous meaning for us and is a marvelous symbol of rebirth, of shedding old ways of being, entering into new ones, of becoming clean. But is it the only possible symbol God could have used for this covenant? Can we conceive of an alternate universe, different from ours, in which God uses different symbols which are just as meaningful in the history and context of that alternative world? That something could be different does not, from the view of Person Truth, diminish its importance to us. It is upon divine promises that we rely, not philosophical unchangeables.

Passivity and Truth

Next, Idea Truth is passive. For example, the Second Law of Thermodynamics cannot come looking for us; it can only wait for us to discover it. Idea truth simply exists as it must, unconcerned about our lives, the world, or indeed anything at all. In contrast, Person Truth is active. It is not some idea waiting out there for us to come and find it. Instead, Person Truth can interrupt us when we are on other errands. The scriptures are full of such stories, such as those of Moses, Enoch, Noah, Samuel, Alma, and others. The scriptures are as much about the activity of God as they are the activity of man. Furthermore, Truth did not just reach out to prophets but also to each of us.

C.S. Lewis described his conversion experience in these terms: as an atheist, he did not want to answer to any divine being. However, he wrote,

You must picture me in that room night after night, feeling, whenever my mind was lifted even for a second from my work, the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet. That which I greatly feared had at last come upon me. I gave in and admitted that God was God and knelt and prayed: . . . perhaps that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.”

Most of us have felt God’s hand gently tug us away from forbidden paths and back into His fold. Certainly, there are things that we can do to invite God into our lives, but He can step over the threshold at the door just as eagerly and actively, and I would suggest that He usually makes the first move.

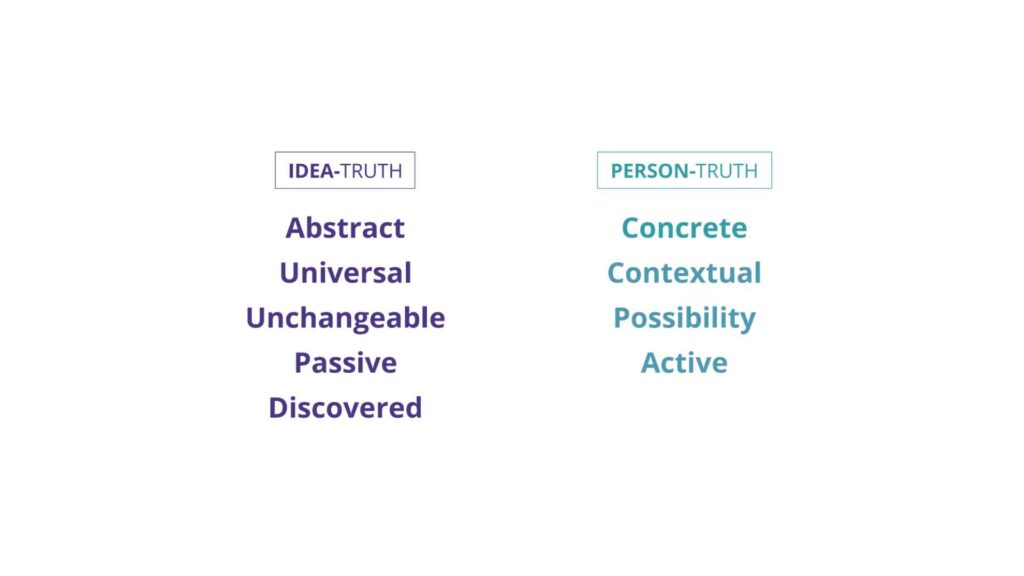

Comprehending Truth

Finally, from a modernist view, the world generally assumes that Idea Truth is comprehensible. We may have a hard time understanding it – most people, for example, struggle to understand quantum mechanics. But from this view, we will eventually figure out the fundamental truths of the universe with enough study, observation, and ingenuity. It is something that we discover through our own endeavors, observations, and reasoning.

This is not true of Person Truth. The Book of Mormon prophet Jacob declared,

Behold, great and marvelous are the works of the Lord. How unsearchable are the depths of the mysteries of Him; and it is impossible that man should find out all His ways. And no man knoweth of His ways save it be revealed unto him. Wherefore, brethren, despise not the revelations of God.”

Consider the ramifications of Jacob’s statement: this implies that reason, observation, or any other human strategy can never get at God unless God decides to reveal Himself to us. We learn about God on His terms and at His discretion. As C.S. Lewis put it,

When you come to know God, the initiative lies on His side. If He does not show Himself, nothing you can do will enable you to find Him.”

Thus, Person Truth is a revealed truth.

Characteristic Summary of Idea Truth vs. Person Truth

To summarize, Idea Truth centers our attention on ideas and not just any ideas – it centers us on ideas that are abstract, universal, and unchangeable. In contrast, Person Truth centers our attention on the divine personage of God and His messengers and embraces instruction and direction that might be highly situated and context-dependent, subject to possibility and change. In the latter worldview, we find our grounding not in abstract universals but in the divine character of God, our experiences with Him, and His promise-keeping. As Taylor Halverson mentioned earlier this morning, both in our own lives and throughout recorded history, the scriptures invite us to trust in God by calling to remembrance the captivity of our forebearers and the deliverance God worked in their lives.

Why Does it Matter?

So, Idea Truth, Person Truth – why does this all matter? I want to explore here some potential ramifications of this worldview that have broad implications for apologists.

Faith as Trust and Fidelity

First, faith can be thought of as trust and fidelity rather than unjustified belief. So often when we talk about faith, we talk about faith as some sort of mental ascent or even a form of mental exertion – believing in truth claims without enough evidence to claim knowledge, whatever epistemic threshold that might be. But if we think of truth as a person, faith begins to take on a dimension of fidelity to, and trust in, the divine person of Christ. When talking about ideas, trust implies epistemic uncertainty; however, we trust in people precisely because we do know them, or at least because we’re coming to know them.

As we experience the hand of God in our lives and make covenants with Him, we come to trust Him and are faithful to Him precisely because we have experienced His steadying hand in our lives and have records of His promise-keeping through history. And this implies also that the first step in growing our faith is indeed to study God’s activity through history, the scriptures, to seek personal encounters with God, and to make sacred promises to Him.

Religion as a Way of Life

Second, religion can be thought of as a way of life instead of as a set of doctrines. Instead of asking what abstract doctrines we believe in, we might ask what shared commitments we have made. Some say that figuring out our doctrine is like nailing Jello to a wall. Doctrines that were emphasized in some decades are de-emphasized in others. The enormous corpus of sermons and literature written by Latter-day Saint leaders and thinkers contain a number of apparent internal contradictions. And this is because, I submit, doctrine in a sense of an unchanging abstract belief system, is not the object of our worship. Rather, the object of our worship is the living and dynamic God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

As William Barrett hopefully explains,

The Hebrew is concerned with practice and the Greek with knowledge. Right conduct is the ultimate concern of the Hebrew, right thinking that of the Greek.”

A bishop living in Brigham City, Utah, might have some eccentric and wrong beliefs about the Atonement, but he might still faithfully keep his covenants and live out his faith in an exemplary way. From the personal view of truth, he is more faithful to truth than someone who has all the right ideas about the Atonement but does none of those things.

A Caveat

I’m going to add a caveat here. I want to be careful. I will argue that promoting teachings that are contrary to the fierce moral witness of prophets and apostles and seeking to undermine the endeavors of God’s servants can be a form of infidelity, a betrayal of our shared commitments. So while this framework suggests that covenant living should be prioritized over doctrinal orthodoxy, this in no way excuses those who treat orthopraxy as the pretext for apostasy.

We might not have to rationally or mentally ascend to the various rational theologies that members or even leaders sometimes construct, but we might be required to believe that God has asked us to live the law of chastity or to compassionately feed and clothe the hungry, and the naked, to share the gospel with our friends and neighbors, and so forth. Otherwise, we might believe in a god who asks for different sacrifices and makes different demands of us than the God of Israel.

Changes in Church Teachings

Third, Church teachings can change, and that’s okay. Idea Truth requires that the shared beliefs of religion remain consistent across time and context. If the current prophet contradicts an earlier prophet or seems to, we assume that the precepts of men, either in the past or in the present, have been passed off as revelation. In contrast, according to Marvin Wilson,

To the Hebrew, the deed was always more important than the creed. He was not stymied by language that appeared contradictory from a human point of view. Neither did he feel compelled to reconcile what seemed irreconcilable. He believed that God was ultimately greater than any human attempt at systematizing truth.”

Furthermore, the God of the Restoration is, above all else, a God who speaks.

James Falconer wrote, “Since Latter-day Saints insist on continuing revelation, they cannot have a dogmatic theology that is any more than provisional and heuristic, for a theology claiming to be more than that could always be trumped by new revelation.“

I’m going to add a caveat here. There are many changes that would add new meaning and evolve our understanding of what has come before. Other changes would make nonsense of what’s come before. I believe that narrative continuity is a strong characteristic of divine teaching, which, though different from the unchangeableness of Greek thought, means that this isn’t a free-for-all.

Both Groups

Some Latter-day Saints argue that we should not become dogmatically attached to the Proclamation on the Family because the Church will someday adopt a more enlightened view of family and sexuality. As Latter-day Saint blogger J. Max Wilson has pointed out, “Just like fundamentalists who reject the living prophets by following dead prophets, [some] reject living prophets by following anticipated future prophets.”

Both groups assume that if one prophet contradicts another or seems to, one must be wrong. But from a personal view of truth, believing in the unfolding restoration does not in the slightest mean that we can blindly ignore the moral witness of the prophets and apostles of our generation.

Ideology vs. Divine Instruction

Fourth, we should be cautious about elevating ideology over divine instruction. I’ve seen far too many friends and acquaintances relinquish their commitments and step off the covenant path because of what seems to be a higher commitment to a political or moral ideology. When we evaluate the teachings of God’s servants against our ideological worldview, whether it be progressivism, libertarianism, conservatism, or any other perspective, we adopt the Idea View of truth.

In other words, the problem isn’t libertarianism, progressivism, conservatism, or any other belief system; the problem is with “-isms” entirely. When those -isms lead us to prioritize abstract ideologies over ongoing divine instruction, or what I might call ideolatry. When we do this, we have supplanted the living God with an idea or a set of ideas.

Understanding the difference between Idea Truth and Personal Truth helps me to see that Latter-day Saints can be flexible in matters of abstract belief while being resolute in matters of loyalty to God and His servants, and also invites us to be more wary of the dangers of ideolatry.

Covenants and Truth

Fifth, truth is known in part through covenant making and covenant keeping. The concept of sacred knowledge is foreign to the modern mind and largely incompatible with the Idea View of truth, which leads us to value observations and methods that are transparent, replicable, verifiable, and accessible to public scrutiny. Anything else takes on a cultish quality. However, from the Personal View of truth, our journey back to God involves more than a disclosure of doctrinal teachings; it involves the self-disclosure of the divine person of God.

In the concept of marriage, we are entirely comfortable with the idea of disclosures that are guarded by pledges of fidelity and largely kept private from public scrutiny, and so it is with our relationship with Personal Truth. The temple rituals, which symbolize divine disclosure and divine encounters guarded by covenants, are far more at home with a Personal View of truth.

It invites us to consider covenant as another dimension to epistemology, and fidelity as an essential prerequisite to knowledge. Further, unlike Idea Truth, Personal Truth can and does intrude upon our lives and makes demands of us. Personal Truth can look you in the eye and ask you why you lied to your mother or deprioritized the things of God. Our moral responsiveness can contour our capacities to know God.

Losing Our Understanding

As Alma taught Zeezrom,

And therefore, he that will harden his heart, the same receiveth the lesser portion of the word; and he that will not harden his heart, to him is given the greater portion of the word, until it is given unto him to know the mysteries of God until he know them in full. And they that will harden their hearts, to them is given the lesser portion of the word, until they know nothing concerning his mysteries.”

Like all relationships, when we alienate ourselves from someone we love, we also lose the ability to understand them, to be at peace with them, to love them. Couples who separate often forget the best things about each other and filter their memories through their present resentments. In the same way, those who depart from their covenants often articulate their former beliefs in ways that seem a mere caricature, a straw man of what they used to believe. We really can lose our understanding of the person of God and His activity in the world as we forsake His ways.

Truth’s Messengers

Sixth, Truth can commission messengers and act through mortal agents. From a modernist perspective, someone is a legitimate authority if they obtain expertise in a verifiable and replicable manner and if their truth claims are based on public observations that contribute to expert consensus. If we think of truth as a person, someone can be a legitimate authority even if they cannot open their methods to public scrutiny and even if they defy expert consensus in ways that don’t lead to future expert consensus.

Personal Truth can commission individuals to act as His spokesmen and His messengers, to be fierce moral witnesses against the sins of our generation. Understanding the difference between Idea Truth and Personal Truth helps us make sense of divine messengers, prophets, and apostles. They are more than just sages handing to us the unchangeables of eternity, who are rendered unnecessary once we sufficiently understand the underlying truths. They are one of our connections with the divine person of God, and they are one of the ways in which He dwells with us in our various historical contexts.

Sin and Repentance

Seventh, and this is one of my favorites, rather than a violation of abstract laws, sin and repentance can be understood in relational terms. From the Idea View of truth, an action is wrong when it violates abstract universal moral truth. For example, some respond to concerns by teasing out doctrine from culture, treating the former as a set of universals and anything else as less important, such as dress or grooming or dietary restrictions, and so forth.

In contrast, from a Personal View of truth, sin is less about whether our behaviors comply with some abstract universal moral code and more about our relational stance towards God and our fellow man. Any behavior that stems from a heart full of pride, a desire to assert our own preferences over the teachings of God and the instructions of His servants, can be sinful, even if they cannot be universalized across time and place. Further, the focus of our relationship becomes the focus on our relationships rather than on abstract compliance.

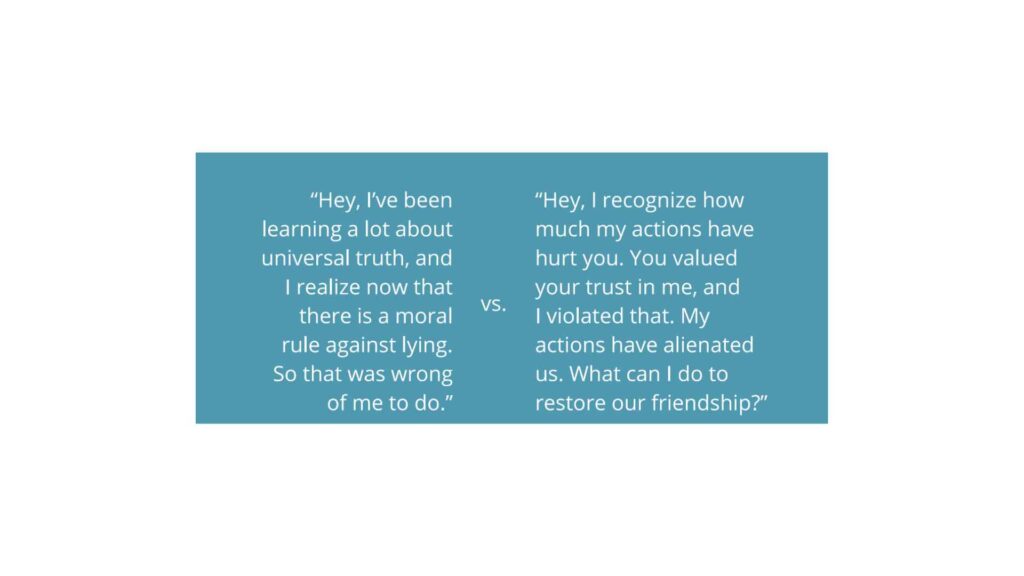

Example

For example, imagine that your friend lied to you about something that was important to you, and as a consequence, your friendship is strained. Later, he approaches you and says, “Hey, I’ve been learning a lot about universal truth, and I realize now that there’s a moral rule against lying, so that was wrong of me to do.” Would this apology restore your trust and repair your friendship? But consider instead if your friend said, “Hey, I recognize how much my actions have hurt you. You valued your trust in me, and I violated that. My actions have alienated us. What can I do to restore our friendship?” This is a far more meaningful reconciliation.

In the same way, sin is wrong not because it violates some abstract rule but because it alienates us from our Creator. We can comply with all the rules, every single one of them, and yet still be at odds with Him, just like we can be just as hurt by a spouse who washes the dishes spitefully than one who never washes them at all.

This provides context for why perfect compliance with moral rules cannot save or redeem us without a covenant relationship with Christ. It is not compliance with abstract rules, but humility and fidelity before the divine person of God that marks us as members of His fold. We will never face an abstract principle to account for our actions, but we will face God.

Enemies of Truth

And finally, truth has enemies in the world who are just as active as truth. If we take the Personal View of truth seriously, we also change our view of falsehood. Lucifer, the father of lies, personifies falsehood and deception just as surely as God personifies truth. And just as with Personal Truth, we can make pacts with the adversary, and the adversary can work in the world through mortal agents.

Our great task is not to sort between true and false ideas but to learn to discern the voice of Truth and the disguises of his enemy. In other words, the grand question is not what to believe but who to follow. From the Idea View of truth, there are no false ideas that we cannot think our way out of. We can always revise our ideas based on systemic observation and rational analysis, no matter how wrong they were to start with. False ideas cannot come looking for us or actively keep us prisoner. But just as the Person View of truth makes Truth more personal, it implies that falsehood is more dangerous.

Idea View

Mormon tells us, at one point, “Satan did go about leading away the hearts of the people, and thus Satan did get possession of the hearts of the people again, so much that he did blind their eyes.” In other words, there may really be intellectual snares and traps that, once sprung, we cannot think our way out of.

This is an apologist’s worst nightmare. It is possible to be held captive by a lie or possessed by a false view of the world. When this happens, even our questions become distorted, their very framings tilting us towards falsehood and deception, infidelity, and covenant-breaking.

From an Idea View of truth, the proper treatment would be rational counterarguments. Apologists are good at that, but there may be many occasions in which no rational argument will be good enough, no matter how convincing we are, no matter how thoroughly we rebut the claims and assertions of our enemies. There are deceptions that, as Jesus said, do not go out except by prayer and fasting.

Mosiah could not persuade his sons; it took a divine encounter to do that. And this means that when we are dealing with those who are struggling with doubt, confused about Church history, experiencing difficulties with our doctrines and standards, we should do more than make counterarguments. Our goal must also be to put them in positions to encounter God in their lives. The Sunday school answers, ‘prayer, Church attendance, fasting, scripture study, ministering, and service’ are perennial answers to age-old questions for very good reasons.

Key to Conversion

And this, I believe, is the key to all conversion, for both those coming into our faith and for those already here and looking for a reason to stay. I appreciate the way it was framed by Bessie VanDenBerghe, who wrote,

While the ‘what’ of gospel doctrine is important and indeed fills the bulk of our sermons and Sunday school lessons, it ultimately can’t walk with us or save us. Looking to the Who reframes our gospel questions . . . and not only leads to a richer faith, but helps us move through even the valley of the shadow of death knowing we’re not alone.”

Every conversion we see in sacred scripture is grounded in divine encounters with God, either directly through the Holy Spirit or through the ministry of those who serve Him. Because ultimately, that conversion is far more than being persuaded to embrace a set of doctrines or ideas; it has been the beginning of a relationship marked by sacred ordinances and sanctified through covenants.

Reevaluating Gospel Questions

Let’s go back to the list of questions from the beginning of this presentation.

I’m not going to answer these; I’m just going to say that some of our questions, many of our questions, are like looking for the corner of a round room. The premises themselves are flawed, so the answers are nowhere to be found. We wrongly take this as evidence against our convictions. But when we adopt the Person View of truth, we might ask God very different questions, questions that are entirely different in kind.

For example, we might ask, “How can I be a better spouse? How can I invite your hand into my marriage? What can I do to serve you in my family responsibilities?” Our concern here becomes about how we can fulfill our covenants and our duties to God and our families.

Consider the source of questions that God answers in the scriptures. When Nephi was asked to build a ship, he asked, “Lord, whither shall I go that I might find ore to molten, that I might make tools to construct a ship after the manner which thou hast shown me?” Nephi’s question was one of action: how could he serve God and fulfill his commandments?

Person Truth

Similarly, when prophets receive revelations of a doctrinal nature, it is usually to seek clarity on how to minister to those in their care, to solve a particular problem in a particular context. When Aaron taught the Lamanite king about the plan of salvation, the king asked,

What shall I do that I might have this eternal life of which thou hast spoken? Yea, what shall I do that I may be born of God, having this wicked spirit rooted out of my breast, and receive his Spirit, that I may be filled with joy, that I may not be cast off at the last day?”

As if to emphasize the relational nature of this conversion, shortly after, the king prayed and asked God, “Oh God, Aaron hath told me that there is a God; and if there is a God, and if thou art God, wilt thou make thyself known unto me, and I will give away all my sins to know thee?”

These are the sorts of questions that presume a Person Truth, and these are the sorts of questions that invariably find divine response. And as we ask questions like these, our lives become populated by spiritually defining moments that, as the dews from heaven, settle into a conviction that this Church was established by God and is led by Him through prophets who speak forth His word. This is how I have found my own testimony.

Conclusion

I want to end today with my witness that Jesus Christ is the Way, the Truth, and the Life, the Alpha and the Omega, the Author and the Finisher of our faith. I want to testify that through experiences too numerous to enumerate and too personal to relate in this setting, that He is real, that He is a divine person of infinite love, mercy, compassion, and discernment. I testify that the purpose of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its teachings, its ordinances, are to help us make and keep sacred covenants that enable us to form a saving relationship with the Savior. And I say that in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Audience Q&A

Scott Gordon:

We appreciate you taking the time to share your thoughts with us. We’re here in our socially distanced question-answer format so, I have a few questions for you. This first one says: Of all the things which you discussed, which misunderstanding about the nature of truth do you find most problematic for the rising generation? In what ways can we best begin to address it without overwhelming them? And what mindsets do we encourage early on?”

Jeffrey Thayne:

Um, which misunderstandings about the nature of truth do you find most problematic, especially with the rising generation, with our youth? That’s a great question. I don’t know if I can answer it exactly because, I haven’t really stacked them in any sort of order of priority in that way. But I will say that I have had a number of friends and acquaintances who have come to question their commitment to the Church, in large part because they discovered, I think, that they had this idea that the teachings and emphasis of the Church must be the same across all time and space. And so, if they find things that were taught by Ezra Taft Benson that they don’t find emphasized, or they might find even contradicted in today’s teachings, that throws them into doubt. And that’s one of the reasons why I started exploring this in the first place. Because for me, I believe, as I talked about in this presentation, that the directions of God are inherently contextual, and that what prophets teach us today are what we need to hear for our day and time. And that doesn’t necessarily mean they can be universalized for all generations or that they might be just as important for somebody 50 years from now, for example.

Scott Gordon:

Excellent. Here’s another question from our audience: How would you suggest building trust and loyalty in God over a set of beliefs and ideologies? What might this look like on a practical level in seminary, Young Women’s, Young Men, and families, etc.?”

Jeffrey Thayne:

I think that our emphasis is, when we teach doctrine, we teach doctrine for the purpose of connecting people to God and our goal should be to get students, for example, to pray, to study the scriptures, to attend the temple, to minister. That’s our goal, not necessarily to explain to them all the answers of the universe because we don’t have them. But what we can do is we can invite them and put them in positions to encounter God.

Scott Gordon:

I really like that. Just on my own note, I always get a little frustrated when people say, “I love our Church because it gives all the answers.” And my thought was, that’s news to me, because there’s lots of things I don’t know. But, I do know a few things, and that’s what I hang on to.

Here’s another one that says, not a question, just a note: Your conception of truth as a person instead of an idea is an interesting one. Have you encountered the work of Brent Schmidt on the ancient concept of faith or pistis? He similarly argues that faith has a lot more to do with trust and loyalty to a covenant or person than about an unsubstantiated belief.

Jeffrey Thayne:

I’ve encountered it, yes, but, I encountered it after we finished and published the book. But yeah, I’m familiar with it.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you. Here’s another one: I love this idea, but how would you propose we understand the foundational historical truth claims within this paradigm? For example, the First Vision really happened; the Book of Mormon is an ancient record, etc.

Jeffrey Thayne:

Exactly as that.

Scott Gordon:

Is there really anything wrong with systematizing these doctrines in logical ways and against the backdrop of philosophy?

Jeffrey Thayne:

That’s an excellent question. I will say that I think it’s okay to have convictions, and I don’t want anything that I’ve said today to imply that it’s not okay to have convictions. It’s important to have convictions. I think that what I would invite us to do is to not harden those convictions to the point where we are resistant to ongoing instruction from God’s servants. I think that’s the point here. We should be soft-hearted about our convictions, especially in the face of ongoing instruction from God. And I think that’s really the only point. My argument would be that we also need a little bit of humility in this as well. But especially when it comes to our abstract beliefs, like, for example, the spirit world. President Oaks recently told us that we don’t actually know as much about the spirit world as we think we do sometimes. And if we take what we think we know and reify it into some sort of dogmatic ideology that we hold with a conviction that is unassailable and beyond teachableness, then we close ourselves off to further understanding that might come from God over time. I think that’s the point.

Scott Gordon:

I think that’s very good. I think there’s a lot of things we don’t know about the spirit world, the pre-existence, or the pre-earth life. All those areas, there’s very little information on. That’s very good. Here’s the last question I’ve received: Since a strong belief in God can be encountered through many religions, how should one distinguish what makes this Church unique in its truth? Can this idea of truth as God be used to convince members that certain doctrines or practices, such as polygamy, temple rituals, chastity, are dispensable as long as they believe in God?”

Jeffrey Thayne:

So, there’s really two questions there. The first question is what makes our Church unique, how can we distinguish our Church from others? And the second question is, can this idea of truth as God be used to convince members that certain doctrines are dispensable? Alright, so the first question: What makes our Church unique? I’m going to draw from Elder Holland’s priesthood talk from a number of years ago, “Divine Authority by Direct Revelation.” I believe that, and through all my encounters with the Spirit and as I’ve come to have a relationship with God, it has come with an unassailable witness that this church does indeed have divine authority, that God really did choose and commission messengers, prophets, and apostles to lead us in the last days to prepare the world for the Second Coming. And I believe that’s what makes us unique. Of course, other religions will dispute that, but that has been what I have encountered in my relationship with God.

Okay, and the second question was, can this idea be used for people that some beliefs are dispensable as long as you believe in God? I would argue that we should be committed and faithful to our covenants, and that is not dispensable. What that means for us might be different depending on the social-historical context of our generation. For example, today we’re not asked to live polygamy; the saints a hundred years ago or 150 years ago were. I don’t have all the answers for that, but because I believe in a God who speaks, because I believe in ongoing revelation, I’m comfortable with the idea that those sorts of things can change across time.

Scott Gordon:

Excellent. So, I’ll repeat what I said before. As you know, I teach accounting and international business, and so, philosophy is not my strength, and when I picked up your book, at first, I thought, ‘another philosophy book that I have to read,’ I suppose, and yet I was immediately grabbed by it. I immediately had aha moments that I had not thought of before. So, I want to thank you for writing the book because it was engaging and very interesting. I immediately took it to my wife and said, “You have to read this. This is really good,” which I’m sure she was surprised at because, again, I’m not, that’s not my genre usually. You know, if it’s a good Excel spreadsheet, that’s good for me.

Endnotes & Summary

Jeffrey’s talk, What Do We Treasure?, explores how different worldviews shape our understanding of the gospel and influence what we see as the “good life.” He identifies four primary worldviews—the Expressive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, and Redemptive Gospel—each defining success and fulfillment in different ways. While Expressive Gospel prioritizes self-expression, Prosperity Gospel equates righteousness with financial success, and Therapeutic Gospel emphasizes emotional well-being, the Redemptive Gospel teaches that true success is found in reconciliation with God. By examining these perspectives, Jeffrey warns that misplaced values can lead people to misunderstand the gospel’s true purpose.

The talk highlights how Gospel Counterfeits arise when cultural influences subtly redefine gospel vocabulary and shift the focus away from Christ. He provides examples of how phrases like non-judgmental love and authenticity take on different meanings depending on the worldview, leading to confusion and potential spiritual drift. Many individuals, even those originally converted to the Redemptive Gospel, gradually adopt cultural values while still using gospel language. This process results in a faith that, while still appearing religious, may no longer align with the teachings of Jesus Christ.

Jeffrey concludes by emphasizing the need for spiritual discernment and doctrinal clarity. While Gospel Counterfeits persist because they offer comfort, validation, or worldly success, the Redemptive Gospel calls for transformation through Christ. Faithful discipleship requires prioritizing God’s values over societal expectations, measuring spiritual success by personal sanctification rather than external achievements. By recognizing and rejecting distorted versions of the gospel, believers can ensure their faith remains rooted in eternal truths rather than cultural trends.

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 9, 2024

- Duration: 26:31 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2024 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: Redemptive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, Expressive Gospel, gospel counterfeits, authenticity, covenant-keeping, LDS worldview, personal fulfillment, character transformation, reconciliation with God, faith crises, gospel vocabulary, Maslow’s hierarchy, LDS apologetics

Common Concerns Addressed

Church doctrines change; how can they be true?

Truth as personhood allows for change based on divine relationship and contextual revelation.

Prophets contradict each other.

Continuing revelation means God’s instructions adapt over time; personal truth allows for historical flexibility.

Apologetic Focus

Covenant as a vehicle of divine knowledge

Relationship over ideology

Faith as loyalty and trust

Personalized, active revelation as the path to truth

Explore Further

coming soon…

Share this article