In his presentation “Real Vs. Rumor” from the 2021 FAIR Conference, Keith Erekson addresses how to discern between truth and misinformation within the context of Latter-day Saint history and culture. Erekson emphasizes the importance of critical thinking and careful investigation to distinguish facts from myths and rumors that often circulate within religious communities.

This talk was given at the 2021 FAIR Conference on August 6, 2021.

Keith A. Erekson is the Director of the Church History Library and a historian known for his work in helping members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints navigate complex historical topics with faith and clarity.

📖 Book by the speaker: Real vs. Rumor: How to Dispel Latter-day Myths

1

Transcript

Keith Erekson

Introduction

Well, thank you very much for the invitation to be here. It’s great to see all of you who are here in the room, and I’ve been enjoying imagining those of you who are gathered electronically. They asked me to speak about a book, and rumor has it that I’ve written one. The title is called “Real Versus Rumor,” and I’m excited to share this with you.

Rumors and Misinformation

Today, we live in a time that is particularly beset by rumors and misinformation, and it comes at us in all arenas of life. We see it in politics, we see it in healthcare, we see it in journalism, we see it in religion, we see it in popular culture. The types of information or the quality of information varies greatly. Sometimes they’re just errors or simple misinformation. Sometimes there are deliberately fabricated hoaxes or conspiracy theories. Sometimes it’s just outright distortion with the intent to deceive and manipulate.

The way this happens is all over the board. There may be photoshopped images, deep-faked video, misattributed quotes, or just made-up information. So the challenge for someone who lives in the 21st century is how to survive in a time like this.

Now, one of the things that we’re learning during the information age is that Americans are particularly bad at verifying information. Lots of research has been done about this. They study people and what they know and how well they do at identifying what are facts and what are falsehoods. A couple of interesting findings: one of them is that if the information comes from someone in the same group as you, then you are much less likely to accept errors. Social media has done a great job of putting us in groups in which we drop our barriers because they are in our group, and so we think that the information is great. False information now in the 21st century spreads faster and farther than correct information.

Falsehoods

Now, you’d think that Latter-day Saints would have a particular advantage. We’ve been talking for about 200 years that these are the last days or the latter days, and we know that in the latter days, there will be falsehoods. There’ll be false accusers. It’ll be a time of error and commotion. For thousands of years, prophets have been warning us, so we should have a head start. One of the scriptures that I remember kind of pondering as a teenager was this one in Isaiah.

He predicted a time when people would call evil good and good evil. I marveled at that, wondering how it could be so blatant, calling the opposite thing what it is. Yet, here we are in the 21st century, if you take a highly scripted television show and put the word “reality” in front of it, all of a sudden, people think that it’s totally unscripted and real and authentic.

Another word doing this work today in our society is the word “freedom.” You can take any kind of lie or misinformation and put the word freedom in front of it, and at least 47% of the population will be right there with you, without even thinking about it.

Unfortunately, Latter-day Saints don’t fare much better than the American population in general.

A couple of headlines on the screen from right here in the shadows of the Wasatch Front. One of them is a question, and the answer in the article was yes – Utah does deserve the title “the fraud capital of the United States.” We see repeatedly times where Latter-day Saints are deceived, duped, tricked, and fall prey to the false information that surrounds us.

Seeking Reliable Sources

Earlier this year, a new passage was added to the general handbook about seeking information from reliable sources. This is not just a Wasatch Front problem, and we’re encouraged now to avoid things that promote anger, contention, fear, or baseless conspiracy theories. This counsel joined counsel that had been in the handbook for a long time about rumors, innuendos, and misattributed quotes to general authorities.

More than 50 years ago, President Harold B. Lee said,

“It never ceases to amaze me how gullible some of our church members are in broadcasting sensational stories or dreams or visions or purported patriarchal blessings or quotations supposedly from someone’s private diary.”

So, this isn’t a new phenomenon for Latter-day Saints to struggle with information.

So, what do we do, and what’s the harm with there being a little bit of error or falsehood or bad information out there?

There are rumors, errors, things like this; they contaminate our thinking. They cause confusion, concern, personal stress, and they prevent us from accepting the truth. As a result, you’ll see Latter-day Saints who stand up and present things as truth that are really just family folklore, false quotes, or political party talking points, and they can’t differentiate the difference. Many times people will feel betrayed when they later learn accurate information. People struggle to find peace. One of the most challenging aspects is that if we can’t sort out what’s real from what’s rumor, we have a hard time understanding and knowing the dealings of God and drawing close to Him.

Why Church History

So in the book, I tackle rumors from Church history. Part of that is a function of my training; I earned a Ph.D. in history. I’ve been a history professor for a couple of decades. For the past seven years, I’ve served as the Director of the Church History Library in Salt Lake City, and so that is something that I’m familiar with, but at a little bit of a larger level. History is an important part of our devotional activities as Latter-day Saints. We are reading historical texts in our scripture study. We study them each week in our curriculum; they’re part of our aspirations to learn things that have been, are, and which will be as we grow in intelligence.

History also infuses our Latter-day Saint culture. We sing hymns about our history; we celebrate holidays; we tell family stories. Places are named after events and characters from our history. Within this space of Church history, there are also lots of rumors and legends and false quotes, and frankly, many of the scams, the antagonistic attacks, crises of faith involve appeals to history or claims about our history. So Church history seemed like a place to start to make sense of what’s real and what’s rumor.

To do so, I play with three meanings of the word myth. The subtitle of the book is “How to Dispel Myth,” and so at one level, we use the word myth to talk about simple errors that stand in opposition to facts, and we’ll talk about the myth versus the fact.

Myths

At another level, there are myths in our culture that are big sweeping cultural stories. They live deep in our minds, giving meaning to what we do. It almost doesn’t matter what the facts are for these kinds of myths; these are mythic stories. They’re part of the stories of nations, civilizations, and the early days of the church. They can be kind of a founding myth around which we try to rally and give meaning to our relationship as a people.

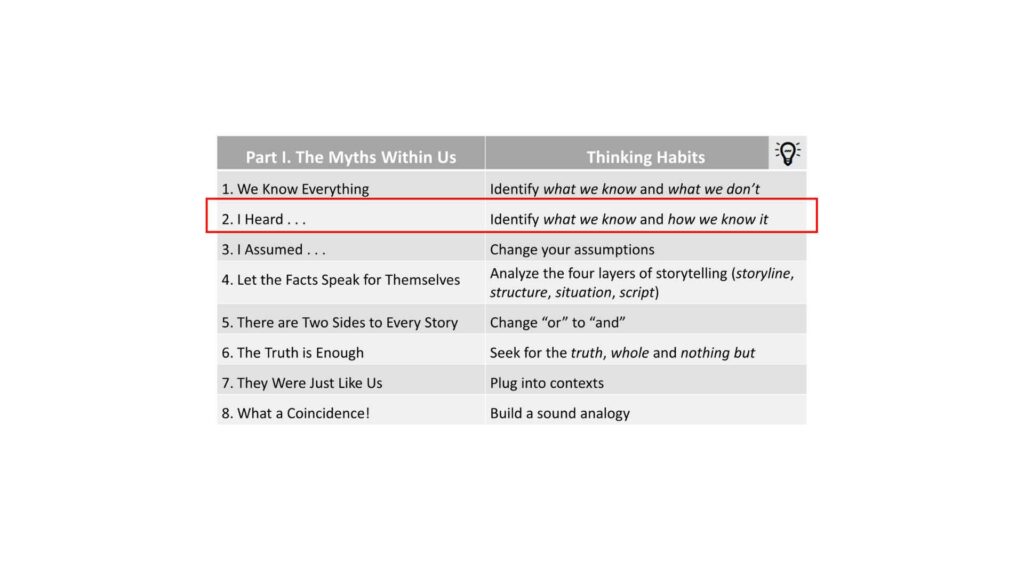

Throughout the book, there are more than a hundred examples of these first two types of myths that are addressed. But the real work of the book is tackling the third one. These are things that I describe in the book as being the myths within us. They’re the things that we carry with us when we walk around, when we think about things or when we don’t think about things. They’re the mental shortcuts that frame the way we respond to information around us.

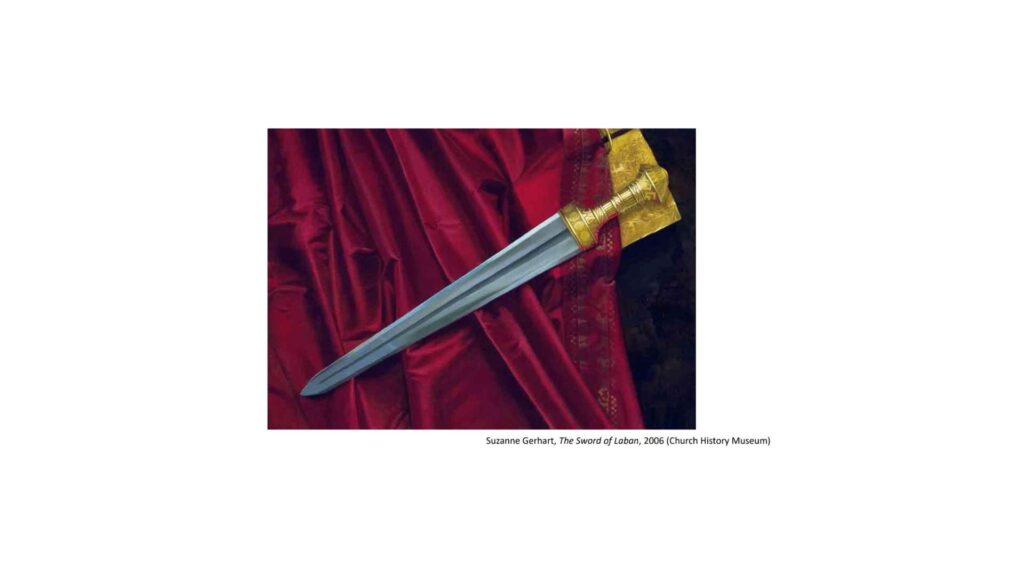

The best way to do this would be to illustrate how this works with the question that has been most frequently asked to me over the past seven years. Whenever anybody finds out that I’m the director of the Church History Library, almost inevitably, they ask, “Do you have the sword of Laban?” Far and away, the most common question I’ve been asked in this position.

Library Metaphor

Now, there’s one interesting thing here to me. The first thing is kind of an assumption people make that I want to dispel with a metaphor for libraries. Most people interact with public libraries, and a common experience is you go there, something gets checked out to you, and you take it with you and bring it back. Well, using that metaphor, the gold plates were checked out from Moroni’s library or archive to Joseph Smith. He had to return them a couple of times; he lost his borrowing privileges for a while.

The interpreters, the stones with the breastplate, they were checked out to Joseph Smith, but the sword of Laban was never checked out to any mortal in the 19th, 20th, or 21st centuries. Therefore, there’s no way. The only way I get things in the Church History Library is if a mortal dies, or maybe before they die, and they give it to us. So, there was never an avenue for the sword of Laban to even come into our collection because it was never checked out of Moroni’s collection.

What We Know and How We Know It

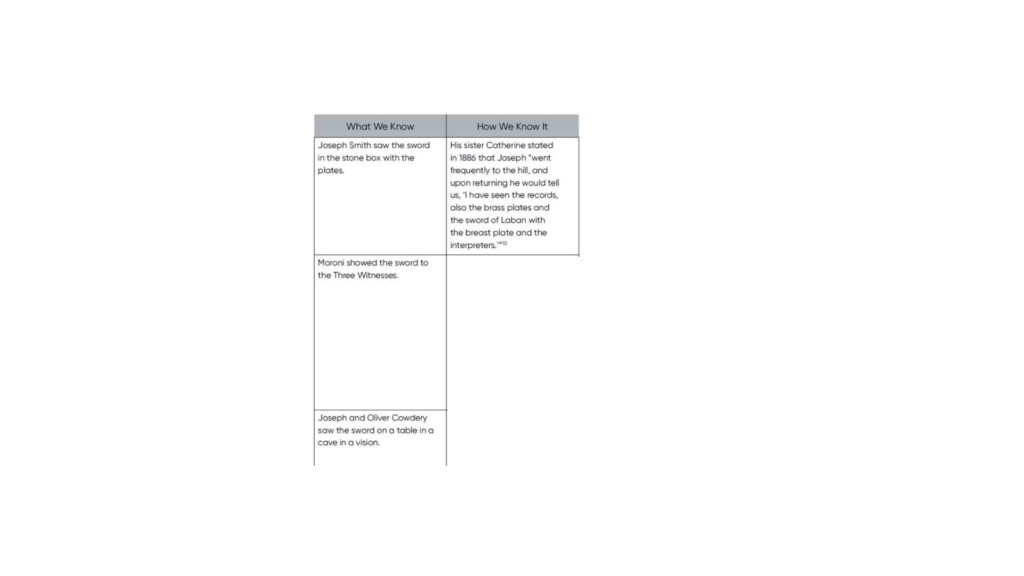

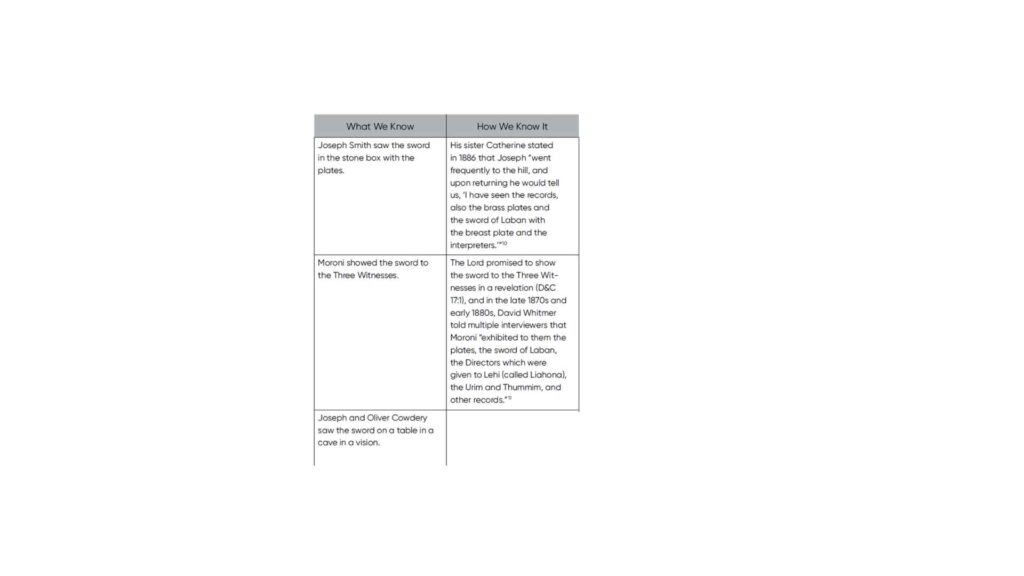

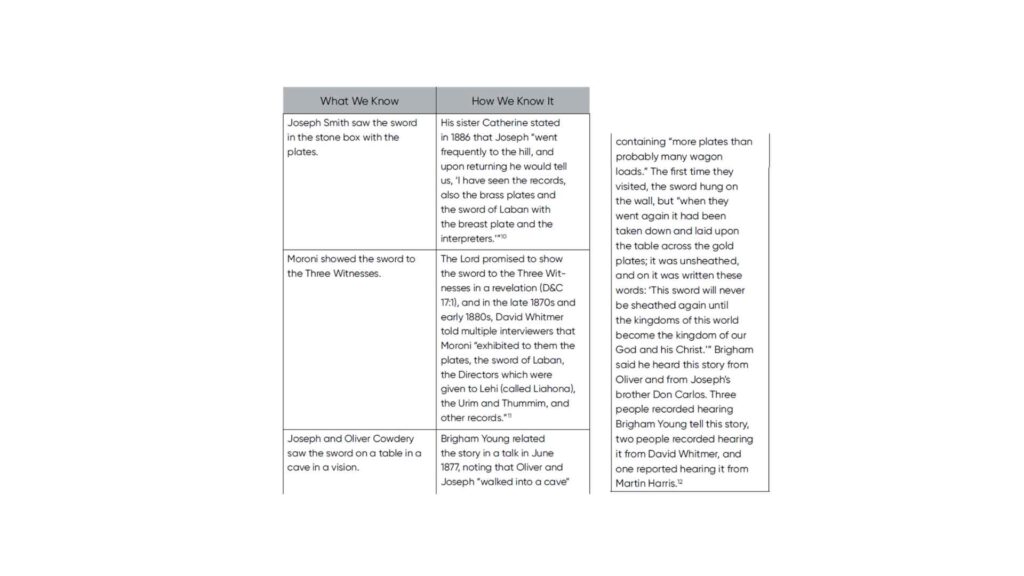

Now, one way to think about this is to think about what we know about the sword of Laban and how we know it. So one of the things I’ve said is that it was never transferred to someone’s custody. What we know about it is that it has only been seen in modern times. Joseph Smith saw the sword in the stone box; Moroni showed the sword to the three witnesses. Then there’s another experience where Joseph and Oliver see the sword on a table in a cave as part of a visionary experience that they had. Sorting out what we know about things is a first step, and then a second step is to ask how do we know that thing.

The Sword

So in the case of Joseph Smith seeing the sword, that comes from his sister, from a reminiscence that she shared in the 1880s. For the part about Moroni showing the sword to the witnesses, there’s a promise in the Doctrine and Covenants, in what is now Section 17, indicating that such an event could occur. Later, particularly David Whitmer, gave several statements about them seeing the sword, as well as the Liahona and other artifacts, as part of that experience.

Now, the most common promoter or influencer of Joseph and Oliver’s visionary experience is Brigham Young. He regularly recounted the story, deriving it from Oliver. Brigham also heard it from Joseph’s brother, Don Carlos, and several accounts exist of people hearing Brigham Young share this story during visits for stake conferences or other settings. Others also heard the story from David Whitmer and Martin Harris.

Building Thinking Habits

So one of the things I encourage in the book is to build thinking habits, making them reflexes. We’re all excited watching the Olympics now, watching the top athletes perform. One of the ways they get to that level is by developing something we commonly call in sports, muscle memory. But the memory part is not really in your muscles, it’s in your mind. It’s a thinking habit. You repeat an action so many times that under stress, under exhaustion, under pressure, under heat, you can do that action. The same needs to be true for our thinking habits. We need to develop them.

The book identifies them, it spells them out. Whenever encountering information, it should become a reflex to question what we know and how we know it. This is the challenge; show me the evidence. Don’t just tell me the thing, how do you know that? And that needs to become a reflex for the information we encounter.

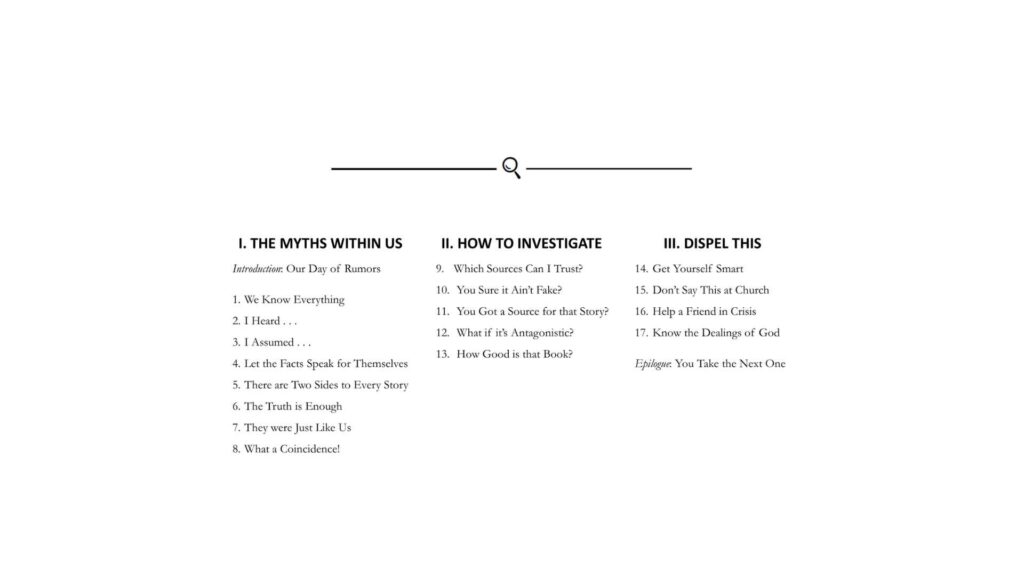

The first part of the book comprises eight chapters discussing various myths that are within us. I’ve talked about the one from chapter two.

Sometimes we go astray because we think we know everything. Well we don’t! We need to identify what we know and what we don’t know. We need to resist the urge to fill in gaps, because, especially in history, the past is gone, the people are dead. There are gaps in our knowledge. We have to get comfortable with gaps in our knowledge.

Ways We May Stray

Another way we go astray is by assuming things. A fourth way is you will regularly hear people say, “I’m just going to present the facts. I’m going to let the facts speak for themselves.” Well that’s a lie–facts don’t speak for themselves, storytellers do. We must cultivate a habit of asking who selected this fact, because there are lots of facts out there. Why this fact, why this group of facts, why in this order and what did they omit? This needs to become one of our reflexes.

Another one that sounds good until we think about it is we’ll say, “I want to hear both sides of the story.” The first problem here is that there are frequently more than two sides to a story. The second problem is that often in situations where what we know is very well established, the plea to include two sides of the story is a way to admit really stupid ideas into the conversation that don’t belong there. They’ll say you need to hear both sides of the story, and many times the other sides are really lame, because one of them is very well established with evidence, and demanding both sides in well-established situations can introduce unnecessary and baseless ideas into the conversation.

The Whole Truth

Another way that sounds good until we scratch the surface a little deeper is to say that “the truth is enough.” In this chapter, I use a phrase common in courtrooms in many nations. That it’s not just enough to talk about the truth, because anybody can pick up one fact off the internet and say it’s true and run around and try and convince people. I want to know the WHOLE truth. What are the things that you’re not sharing which are also true. And I also want “nothing but the truth,” because exaggerations creep into stories that we talk about as being true. Then there are efforts to put things into proper contexts and draw sound analogies.

Sniff Tests

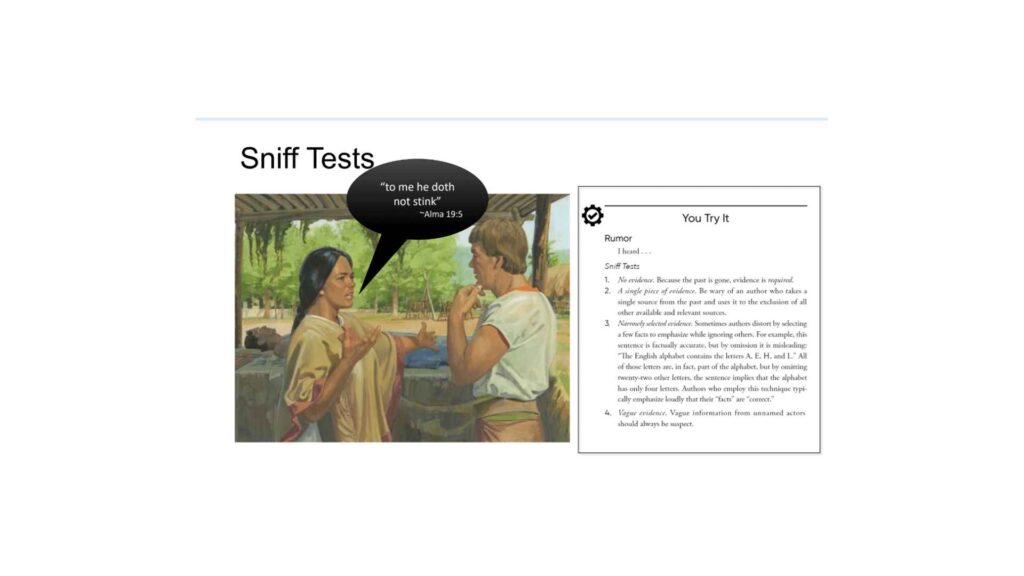

Now there’s no way to be an expert in everything. There’s no way to know everything about everything. I don’t know everything about everything in Church history. I learn something new each day. So one of the things that the book encourages is the development of “sniff tests.”

I drew inspiration from the story in The Book of Mormon when the Lamanite king is presumed to be dead. He’s collapsed in front of his servants, and his wife, the queen of the Lamanites, is wondering what to do. The servants tell her that the king is dead and he stinks and they should bury him. She calls in Ammon, who was part of the reason, but not the main reason, but he was part of the context for why the king collapsed and asked Ammon what to do. She rehearses that the servants say he’s dead and should be buried, but that “to me he does not stink.” So what I learned from this example of this queen is that while she’s not a medical expert, she wasn’t even in the room, but she knew enough to say that something doesn’t smell right.

That’s what I encourage with these sniff tests. In each chapter, after going through these different myths, and then providing the reflexes for how to deal with them, I introduce sniff tests, which are just being aware of warning sign, red flags. You may not even be able to put your finger on it, but you can say something’s not right here, something doesn’t smell right.

Evidence

From Chapter 2 on evidence, you can see if there’s no evidence, that’s huge. If you ask, how do I know that, and there’s no evidence, that’s something that should cause you to think twice. If there’s just one piece of evidence or a really narrow definition of evidence, or if it’s really vague, again, these won’t tell you the full answer, but they’ll give you a clue that something’s not right before you click “like” and share it with all of your friends on Facebook. If you see these sniff tests, you’ll pause and make sure you can figure it out.

So those habits come together, and midway through the book, I put them into a little model for investigation, which becomes kind of a larger habit as we encounter information. Survey the situation from which it has come, really dive in and analyze the contents, then plug things into all the appropriate contexts to make sure that we’re understanding things in all of the ways that they should be understood, and then ultimately draw conclusions to evaluate the significance of the information.

So, I’ll illustrate this with another story from Church history.

Story From Church History

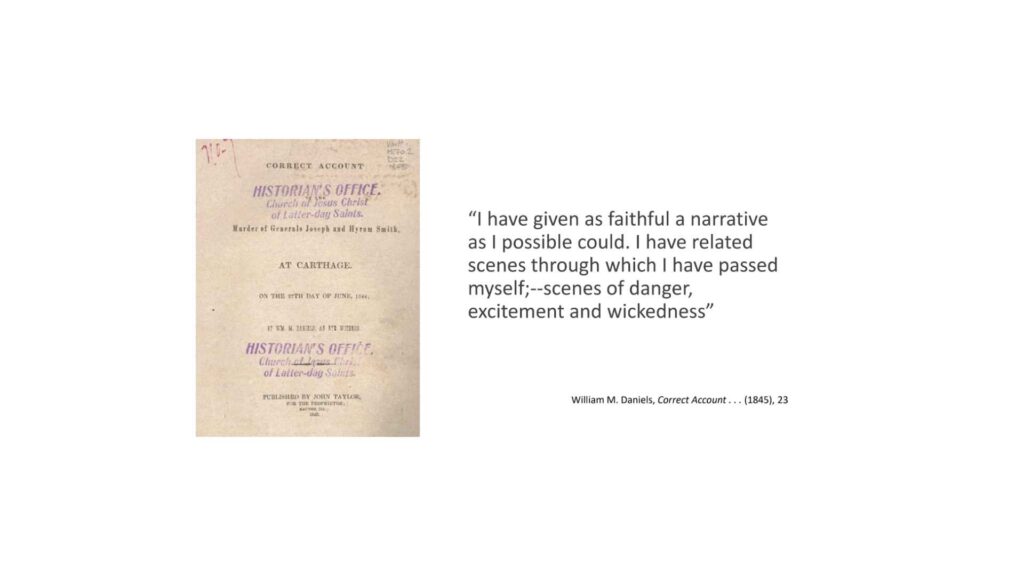

There was a man in Carthage at the time that Joseph and Hyrum were murdered. His name was William Daniels. He was not a member of the Church, but he was appalled by what he saw, the kind of mob rule, the chaos, the murders, and that outraged him. Eventually, he felt the need to write down his experience as a witness to this injustice on the frontier. In the coming months, he also learned more about the Church and was baptized, became a member of the Church. The following year, he published a pamphlet called ‘A Correct Account of the Murder of Generals Joseph and Hyrum Smith at Carthage,’ a nice long 19th-century title. But in there, he gives his testimony as an eyewitness, as someone who was in Carthage.

‘I’ve given as faithful a narrative as I possibly could. I’ve related scenes through which I have passed myself, scenes of danger, excitement, and wickedness.’ Now, Daniels described a lot about Carthage, about the setting, about the jail, about the layout, about how the mob appeared.

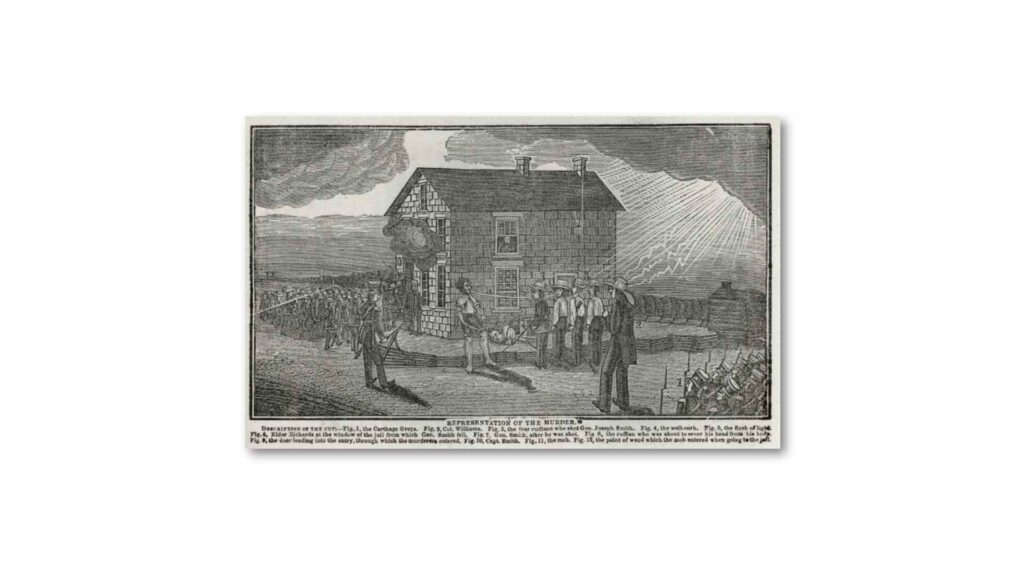

One of the stories that he told was illustrated with a woodcut and it took on a life of its own. Daniels reported as a first-person witness of the experience that after Joseph was murdered and fell out of the window, one of the ruffians, that was the term that Daniels used, came up and said aloud to his fellow murderers that he was going to cut off Joe Smith’s head. So, you can see the depiction there, and Daniels relays the story that as the ruffian went up and attempted to decapitate Joseph’s dead body, a ray of light, a flash of lightning came from heaven and froze him in his tracks, and he was unable to desecrate Joseph’s body.

Discredited

Such a powerful story, exciting story, a tale of excitement and drama that Daniels promised, and it was illustrated. We know today we swim in a visual culture, but illustrations are particularly powerful at presenting information and kind of stamping it into people’s memory.

Well, it turns out that shortly after publishing the pamphlet, Daniels was called in to testify as part of the legal proceedings about what happened in Carthage. Eventually, the alleged murderers were all acquitted, but in that process, Daniels was cross-examined. He was asked about this story, and under cross-examination, he had first said that it was inserted by the publisher, that he didn’t know anything about it. Then he kind of confessed that it was all made up.

So very quickly, the story was discredited, but the pamphlet had much longer legs than the account, the notes, and the minutes of the trial. So the story was running wild among Latter-day Saints. The retraction under cross-examination, not so much. This is a story that fired the imaginations of Latter-day Saints throughout the 19th century, and some in the 1880’s or so.

Corroboration

Some corroboration appeared. I hope you’ll watch for sniff tests as we go through the story. A letter was discovered; it was written by a man named William Webb and dated October 14, 1844, and it described the same story, the same experience to lend corroboration to the events. But the letter was written to an unnamed newspaper that never published the letter. That newspaper was acquired by a new unnamed owner who found the letter in the papers of the business that he had acquired.

The unnamed owner then passed the letter to an unnamed friend to look at for a few days, and coincidentally during those few days two missionaries, Elder McEwen and Elder Warren, made a copy of the letter and testified that the copy was accurate. The original was never seen again, but this corroborating copy was published, and so off it went.

One young convert, who arrived in the Utah Territory and began to paint the scenes of the early restoration, heard about this story, heard about the corroboration and C.C.A. Christensen put this scene into brilliant color, brilliant detail, and this story was one that B.H. Roberts spent much of his time trying to eradicate.

Now, in the Church History Library, we host a database of missionaries. Our goal is to identify every missionary who served in the first hundred years of the Church’s history. I can tell you that Elder McEwen and Elder Warren aren’t on the list, which shouldn’t be a surprise. That string of unnamed, vague evidence, that vague trail is definitely something that tells you that something is amiss.

How to Investigate

So in part two, all of those skills come together to investigate. It walks through sources, primary sources like Wilford Woodruff’s journal. It walks through stories that people tell later, like Lucy Smith’s history, and how we can judge the reliability of her history. It also walks through modern studies, books, and articles and talks about how they work. Along the way, I stop and talk about forgeries and also antagonistic writing, because these same principles of analysis apply to all of these different kinds of material.

The book concludes in part three with a charge to the reader, and since you’re hearing about it today, I’ll extend the charge to you. We have to go out and dispel the myths and the errors and the rumors and the misinformation around us. I identify four specific places where we are desperately in need of this kind of help as Latter-day Saints. One of them is in personal devotion, personal studies, and so there’s a chapter about our own quest for knowledge and information.

We can’t sit around and wait for the Church to tell us something, for the Church to say something at a general conference, for the Church to put it in the curriculum materials. Part of being a disciple of Jesus Christ is that we follow what appears to me to be his most oft-repeated counsel to ask, seek, knock, “come unto me,” “come follow me.” He is repeatedly urging us to be seekers, to be inquisitive, to seek for knowledge about Him.

Our Roles as Church Teachers and Speakers

A second space where Latter-day Saints need to be actively involved in dispelling the misinformation around us is in our Church roles as teachers and speakers. We regularly have opportunities to teach, and so in those opportunities, we need to make sure that what we share is the best possible information. A few years ago, there was a Young Women’s camp here on the Wasatch Front, and they selected as a theme for their conference “Aim High.” The goal was to encourage the girls to be everything that they could be, to strive for their best, to gain education, to build their talents, to aim high.

So they selected as a scripture to accompany this theme a passage from the Book of Second Nephi, and it says something loosely like, “I will ascend unto the clouds, I will be like God.” It’s a paraphrase. So they plastered this theme and this scripture everywhere on the water bottles, on the study notebooks, on the posters, on the T-shirts. The speakers referenced it, the stake president, his counselors, bishops, stake leaders. This theme, this scripture, were the message for the girls during this week at camp.

Context

Well, one night, one group of girls had the idea, let’s read the whole chapter where this passage comes from. And so they opened it up in Second Nephi. It turns out that it’s from the Isaiah chapters, but it turns out that the teenagers were smart enough to understand Isaiah. It’s not as difficult as sometimes we make it out to be.

So they’re reading along, it’s sounding interesting, it’s symbolic, and they’re making sense of it. Then they get to a part where Lucifer starts to speak, and it’s a few verses ahead of their verse, and they say, “Oh no.” And they keep going, and sure enough, the passage, the words “I will ascend upon high, I will be like God” are Lucifer’s aspirations for dismantling the plan of salvation. The girls looked around at each other and they said, “What kind of camp are we at now?”

Just cherry-picking a verse, ripping it out of context, placing it where it shouldn’t be is the first problem in this story, but there’s an even more tragic one. The girls took the finding to their stake leaders, and they said, “Look, look where this passage came from.” And the leaders said to them, “Yeah, we actually noticed that, but it was after we’d printed all the posters and everything, so we hoped you wouldn’t. Please don’t tell anyone.” Well, two of the girls brought me the materials and told me the story. So I think we need to share stories like this and not do this. We need to quote sources; we need to use them appropriately.

The Last Days

I think a third place where correct information is extremely helpful is with helping our friends who are in crisis. This is part of the last days. It was prophesied that perilous times would come; there would be false information. It shouldn’t be a surprise to us that people are struggling with false information. In a certain way, we should say, “Oh good, those two thousand year old prophecies are accurate, okay.” So let’s dive in, but this is definitely a place where good thinking, good habits, the ability to evaluate information, is helpful.

Good Information and Knowing the Dealings of God

The final chapter talks about the role of good information, accurate historical information, in knowing the dealings of God. There are a couple of scriptures in the Book of Mormon that really inspire me in this context. One of them comes in the Second chapter of First Nephi. In the very beginning Nephi’s talking about his brothers, Laman and Lemuel, and this is long before his brothers will tie him up or try and kill him or separate into warring civilizations, this is at the very beginning. Nephi makes an observation that at this point in their story his brothers murmured, but Nephi gives a reason. Nephi says they murmured because they knew not the dealings of that God who created them.

This phrase about knowing the dealings of God shows up again in Mosiah 400 years later in the timeline of Book of Mormon history and it’s kind of a high point for wickedness among the Lamanites. It talks about their murders and their idleness and all kinds of things, but then it wraps up the list by saying the reason they do this is because they don’t know the dealings of the God who created them. So to me it feels like knowing the dealings of God is something really important for Latter-day Saints and I think we need to be more clear and specific about this than we are a lot of times.

We’ll just kind of cozy up to something, we’ll describe an experience and then we’ll say, “gee that couldn’t have been a coincidence” and that’s like our half-embarrassed, half-sloppy way to say that we think God was helping us. Or maybe sometimes we wink “that sure wasn’t a coincidence.”

Acknowledging God

Well I don’t think God has dealt with the children of men throughout the history of the world and commanded prophets to record his dealings, for us just to go around winking about coincidences. I think that God wants us to study the history of his dealings and to walk away with them being able to say positive things about how God deals with people. Not just to wink and say we think somewhere in those coincidences is God, but to be able to positively say a member of the Godhead, the Holy Ghost, brought this message to us.

To be able to see, to be able to say things like “God gave people agency” and “I can see the operation of their agency in this setting.” To be able to say things like “God is a merciful being and this act is a tender mercy.” Elder Bednar used this phrase recently but it goes back. Nephi was using it in chapter one, the author of the Psalms uses the phrase; and I think we can be more positive in acknowledging that God is alive, that He’s present, and that His mercies are visible and they’re part of our experiences, and what we can know.

Your Next Task

So, ultimately this points to the epilogue which points back to you. You have to take the next one, I don’t know what it’ll be. Maybe it’s a video on youtube about the end of the world. Maybe it’s something that somebody says in sacrament meeting. Maybe it’s information that you get from a family member. I don’t know what it will be, but I promise you that in the 21st century, in this information age which includes misinformation and disinformation and errors and rumors and hoaxes and conspiracy theories, every one of us will be called upon to verify information.

Just last night one of the relatives on my wife’s side of the family posted something really really stupid on facebook. My wife said “listen to this,” and I said “well that’s easy.” They named a person who’s on Google and it took five seconds to find out that the information was wrong. But the relative had already shared it and other people had chimed in. They were getting angry about it, they were getting excited about it. For the record it had to do with vaccinations, and what was posted was why they’re not effective. But anyway, they were off in their little circle of misinformation. And it literally only took five seconds.

Living in the Information Age

I like to talk about our age as the information age and not to criticize the Internet; this is sometimes a reaction. People will say, “Well, the internet did this, the internet is bad.” In the information age, the internet is our best friend. Within a couple of seconds, we can verify things, corroborate information, and see if others have done that homework.

So, may God be with you as you strive to sort out what is real from what is rumor in these perilous times. Thank you.

Scott Gordon:

So, I have a quick anecdote. I was mentioning something to my grown daughter. I think the comment was, “Well, don’t believe everything you read on the internet.” And she turned to me and said, “Dad, ‘FAIR’ is on the internet.”

Keith Erekson:

Well you said, ‘Don’t believe everything.’ You can believe some. As long as you check it.

Scott Gordon:

The first question is: If you had the sort of Laban, would you admit it?

Keith Erekson:

My answer is there’s no way for me to even have it. But they say we sing in our hymn that angels are silent notes taking. So if any of those note-takers know Moroni, let him know we are ready for it. We’d be happy to put it on display and show it if only he would loan it to the library.

Scott Gordon:

Of course, I had another one of the same thing. It says, “Of course, you don’t have it. It’s in the First Presidency vault with the Urim and Thummim and the Liahona.” But that’s awesome.

So, how do we work to counter bad or harmful history, and then name one particular pro-American book and its sequels published by someone such as Deseret Book, whose imprimatur carries an aura of authority for many members?

Keith Erekson:

Yes, so there are some books that contain bad information, information from Deseret Book. How do we deal with that? Let me say this in the most polite way that I can. There’s bad information everywhere. So, I think one shortcut that people often use is, “Well, it came from a certain place or source or whatever, so I don’t have to think about it.” My answer to that would be you should be thinking about questioning, challenging everything that you encounter.

A few years ago, there was a study done of artwork in Church curriculum materials, Church magazines. The painting that appeared most frequently about the Book of Mormon translation was one in which (and this is on the cover of the Ensign, this is in Church manuals, Church materials) the painting was one in which the gold plates are uncovered on the table, and Oliver Cowdery is sitting there scribing. There isn’t even a seer stone or anything like that. This is just kind of obvious. There would be no need for three witnesses, that whole experience, if Oliver had seen something. Yet the painting openly depicts the plates sitting on the table, Oliver sitting there, Joseph dictating. So, yeah, there is bad information everywhere, and just because there’s bad information everywhere doesn’t mean you immediately jump to the conspiracy theory that somebody evil has created that and they’re trying to trap you. There’s just bad information all around, and so we just need to get into the habit of always having the radar up, always sniffing things out, no matter where it comes from.

Scott Gordon:

How can we extend trust in ancient scripture when we often don’t have the same access to sources and paper trails to evaluate the provenance of those stories?

Keith Erekson:

Yeah, so ancient scripture is definitely harder. You know, Old Testament times, we have fewer, the New Testament a little bit more. One of the blessings of the modern restoration is that it was in an era of paper records and more record-keeping and publishing. So we have more, but even then, we’ve lost so much. And I think one of the things that I learned from the study of history is to be humble, to start by acknowledging that there are so many things that we don’t know. The people are gone, the sources are missing, they were never recorded.

One of the errors, one of the myths that we carry is that we know everything, and people get up and say, “This happened in history.” Any kind of story like that that begins with this kind of absolute certitude of everything being known, they’re covering up something. History, if anything, prompts humility because we just don’t know things. And I think prophets, ancient prophets, serve as models in this. Nephi says things like, “I don’t know the meaning of all things, but I know God loves His children.” And those kinds of phrases, I think, should surface more. I don’t know everything about Emma. We talked about Emma this morning. What’s missing from Emma? Oh, I don’t know. How about any record that shares her internal thoughts? She didn’t keep a journal. We’ve got a couple of letters. Jenny went through some of the external sources. You know, she did an interview, and there are revelations that talk about her. We know where she moved, and she travels with Joseph. We can reconstruct public Emma quite well, actually. But what was she thinking? What was she feeling? That’s not there. And it’s not just a problem with Emma. After George Washington died, his wife burned all of their personal correspondence. So we know a lot about where Washington fought and when he needed more troops and when he wrote to Congress. But what he thought, what he was feeling, that, for us, is forever gone. And so we’re always being humble in what we can know about history.

Scott Gordon:

I appreciate that. So, we have one person here who’s hoping you’ll clarify something that’s in your book. She’s concerned about a statement that says the Church is moderate on abortion, and they said it’s not; it’s pro-life. They’re hoping that you’ll expand on that a little bit.

Keith Erekson:

Oh, that’s a great question. So, this comes in that chapter about there being two sides to every story. This is particularly true; I mean, American culture is extremely polarized right now, and it’s bigger than Church questions. Politics want to polarize: vote for us. If you vote for the other side, the nation goes to hell. But, so, I talk about in there the problems of polarization and I introduce some strategies, and one of them, where this reference comes from, is that one of the strategies of a polarized choice is that there are only two things. One counter is to look for something in the middle.

Now, that doesn’t mean it’s exactly in the middle. I think that that’s an error sometimes people make: well, it has to be exactly in the middle, the arithmetic mean or whatever. No, it just means that as things get stretched in two directions, there’s probably somewhere in the middle that is different. And so, we have two extreme positions on abortion in our debate right now: yes, always, and no, never. Well, what’s the Church’s position? It’s actually neither of those. We’re not yes, always, and we’re not no, never. You read in the General Handbook, and you hear it from general conference addresses, there are instances that they name where abortion is an appropriate solution: the health of the mother, the health of the child, rape, incest. And so, if you do the thought experiment, if there’s a regime that imposes no, never, could we practice what our leaders teach is our beliefs? And we couldn’t. So, that’s not the center of the yes, always, or no, never debate, but it is somewhere in the middle, and it is importantly somewhere that’s not one of those angry extremes. And if we can move beyond those to looking for other answers, then we can start to, one, dial back the anger and contention, and then, two, as Latter-day Saints, we can try and practice things that we believe.

And while we’re talking politics, Latter-day Saints see this on other questions like immigration, like care of refugees. So, there are lots of ways where we need to step in and say the current polarization is not where our faith lies. Let’s advocate for spaces where we can do what we need to do as disciples of Jesus Christ.

Scott Gordon:

Appreciate that. So, one more question here. I read somewhere that while the story of seagulls devouring crickets happened, some contemporary accounts make no mention of it. Could this be a story that improved with age?

Keith Erekson:

Yeah, this one shows up in chapter six in the analysis. And this is where I use that framework of the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. And so, there are parts of the seagull and cricket story that are true. The saints were there; they were struggling; crickets came, seagulls came. Those parts are true. The part about the whole truth is that there are other factors that get omitted. The saints that year were actually more worried about drought and frost. The frost was late; it was freezing in May and June. And so, crops would freeze at night, and then the crickets or the katydids would eat them during the day. And so, there were lots of threats, and by just focusing on the crickets, we forget the wider context.

And then, yes, the nothing but the truth part applies over time. People started to tell the story; they started to exaggerate it. The book goes through in detail, but many of the exaggerators were people who weren’t in the territory at that time. They were on missions or away somewhere else. So, they hear it second hand; they exaggerate it, and ultimately, it becomes a story where the only thing that happens is crickets show up, and then the only thing that happens is the birds come and eat them. When you go back to the contemporary records, one of the things you see is that the birds leave before all the crickets are even gone. And so, it wasn’t kind of that simplified; this is a way that we oversimplify things, but I get it. And this is a charge: if there are any artists in the room, the next monument, I challenge you to depict drought and freezing, not just the crickets.

Scott Gordon:

It’s difficult to do. Yes. So, with that, we really appreciate your time, and you’ll be back at our author table right by outside the door to sign books if people are interested. Thank you so much.

coming soon…

Why do historical accounts differ?

Differences often reflect varying perspectives, purposes, or audiences. Examining multiple sources helps build a more complete understanding.

How can we reconcile faith and difficult aspects of Church history?

Understanding the historical context and recognizing the evolving nature of revelation can help reconcile faith and complexity.

Encouraging thorough research and context-based understanding.

Addressing challenging topics with a faith-centered approach.

Emphasizing the compatibility of faith and historical study.

Share this article