Jeff Bradshaw’s presentation honors Hugh Nibley’s groundbreaking work on ancient Enoch texts, particularly the Book of Moses and the Book of Giants (BG), and highlights significant new findings since Nibley’s time. Bradshaw discusses the striking thematic and narrative similarities between the Book of Moses and BG, emphasizing the shared elements that strengthen the case for the antiquity of the Restoration scripture. He concludes by urging continued exploration of ancient sources to deepen understanding of modern revelation

This talk was given at the 2021 FAIR Conference on August 4, 2021.

Jeffrey Bradshaw, holds a Ph.D. in Cognitive Science, is an award-winning researcher, and is best known in the Church for his detailed commentaries on the Book of Moses, Genesis 1–11, and temple themes throughout the scriptures.

Transcript

Introduction:

The title of my presentation is Since Hugh Nibley: Remarkable New Findings on Enoch and the Gathering of Zion.

Honoring Hugh Nibley in Word

Like the wonderful presentation we heard this morning from Kirk Magleby, my purpose is to commemorate Hugh Nibley on the occasion of the 111th year since his birth. First, I will share some of the ways he is being commemorated in word by making his life and work better known to a new generation. Then, I will talk at greater length about our efforts to remember him in deed by building on lines of research that he began.

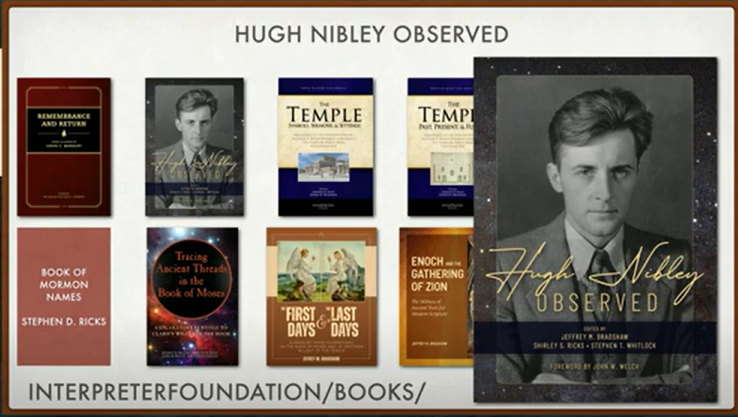

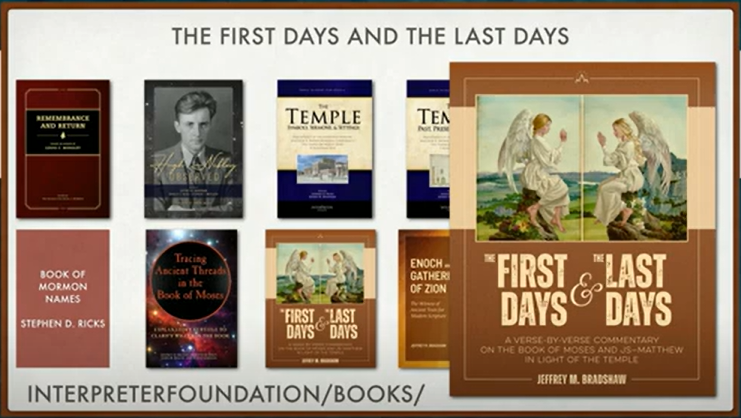

2021 is a landmark year for book publishing at the Interpreter Foundation, with four new books in print so far this year and four more to come. We hope you will take a look at all of them at the Interpreter display table and in the FAIR bookstore. We’re grateful for our longstanding partnership with Bret Eborn at Eborn Books.

We’re especially proud of the joint work with Book of Mormon Central and FAIR on the landmark volume entitled Hugh Nibley Observed, an in-depth look at the story behind the scholarship and the man behind the legend.

Media Resources

As an even easier introduction to Hugh Nibley for a new generation, we have created a series of blog posts, podcasts, and twenty-three YouTube videos on his life and work. We have also posted a new version of the wonderful biographical film The Faith of an Observer, including, for the first time, complete subtitles.

All these media resources, along with details on Hugh Nibley Observed, are available at the link shown here.

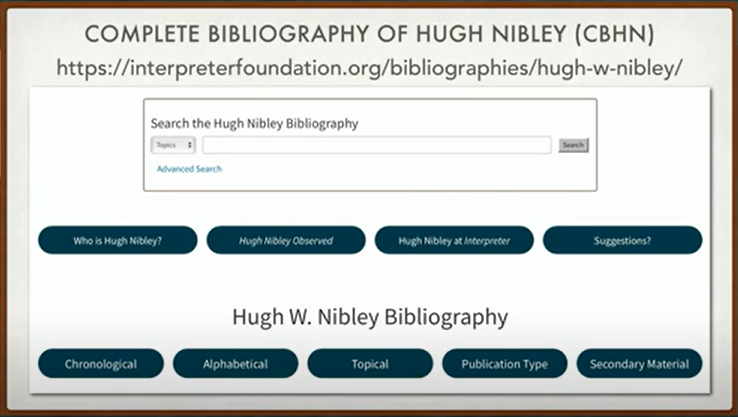

Today, we are pleased to announce the public launch of the Complete Bibliography of Hugh Nibley (CBHN), another collaboration with Book of Mormon Central. It contains over 1,400 references to published and unpublished writings by Hugh Nibley and others, many with freely downloadable content and others with links to bookstores where physical items can be purchased.

It is still a work in progress, with hundreds of additional references—including PDF, video, and audio files—to be added in the future. Please excuse our growing pains as the software and content are gradually improved.

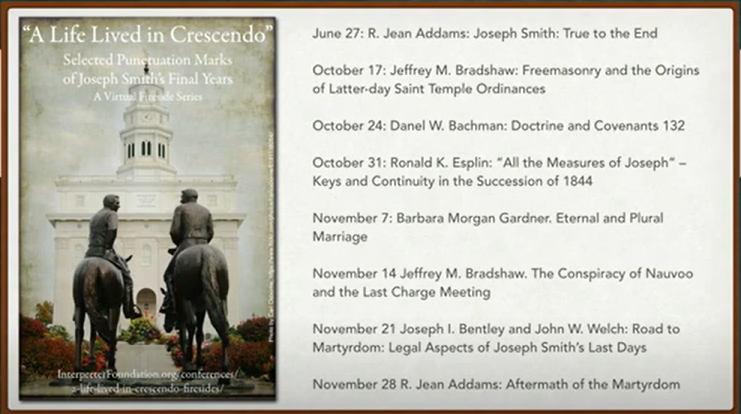

Nibley wrote profusely in response to critics of the Prophet Joseph Smith, so we decided to sponsor a series of virtual firesides this year, featuring new research on misunderstood and sometimes controversial events and teachings from the last few years of Joseph Smith’s life.

An introduction to each of the firesides will be provided by former Assistant Church Historian, Richard Turley.

In partnership with BYU Religious Education, FAIR, and Book of Mormon Central, we have worked to remedy the past neglect of serious study on the Book of Moses.

The Book of Moses

Nibley said that if we really understood the treasures it contains, it would “put to rest the silly arguments about who really wrote the Book of Mormon, for whoever produced the Book of Moses would have been an even greater genius.”

In honor of Hugh Nibley, we have sponsored two conferences applying serious scholarship to evidence of “ancient threads in the Book of Moses.” We have now published a two-volume work of more than 1,300 pages with our results, available in inexpensive digital and softcover editions, as well as in online videos.

Elder Bruce C. Hafen, pictured here with his companion Marie, who provided the keynote for the first conference, beautifully summarized our consensus when he said:

The Book of Moses is an ancient temple text as well as the ideal scriptural context for a modern temple preparation course.”

Readers of this book will find ample evidence for this truth.

The First Days and the Last Days

Two other books on the Book of Moses will be released this fall in time for the 2022 Come, Follow Me curriculum.

This scripture commentary, titled The First Days and the Last Days, not only has a meaningful title but also features a beautiful cover—with angels as bookends looking both forward and backward to Christ’s mission in the meridian of time.

This imagery attests to Nibley’s view that both the story of Enoch and the “little apocalypse” of Joseph Smith—Matthew “belong together in the same book.”

Enoch and the Gathering of Zion

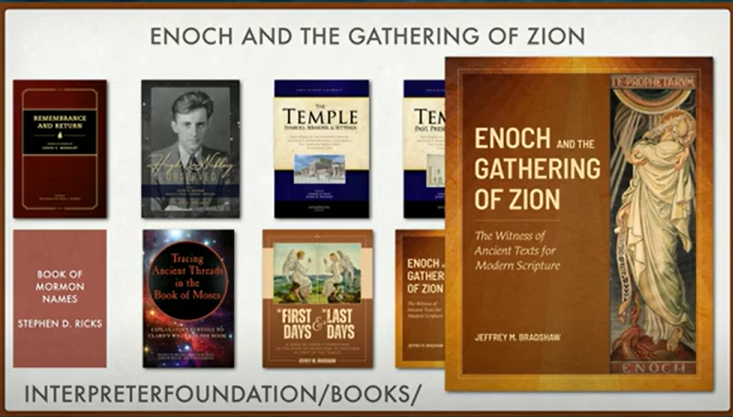

Finally, we come to the book that best fits today’s topic: Enoch and the Gathering of Zion.

Here, we will see the full context of what we now know about the culture, geography, and characters of Enoch’s time and story—assembled for the first time from ancient sources and modern scripture into a single unified story.

I like to think of it as adopting the spirit of Nibley’s wonderful book, Lehi in the Desert, but now applied to Enoch and his people.

And, we might add, applied to ourselves, for as we will get a small glimpse of later in this presentation, Enoch’s story of the first days is also our story, the story of the last days.

Book of Giants

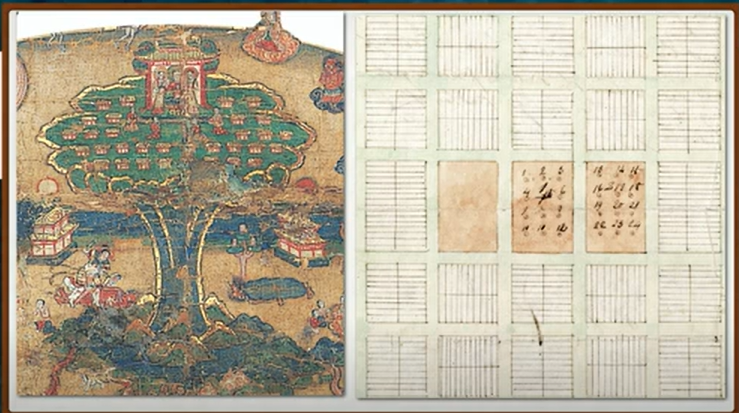

The photo shows a fragment of BG written in Aramaic, found among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Besides being the most popular Enoch book at Qumran—even more popular than the better-known 1 Enoch—BG also appears to be the oldest extant Enoch manuscript found anywhere.

It was first discovered in 1948 and first published in English in 1976.

Other fragments, in six different languages, have been found among the writings of Mani, founder of a religious sect called Manichaeism, and were published in English in 1943.

Thus, both these books were not available in the time of Joseph Smith.

I want to mention two important things that you should know about BG.

Mighty Men

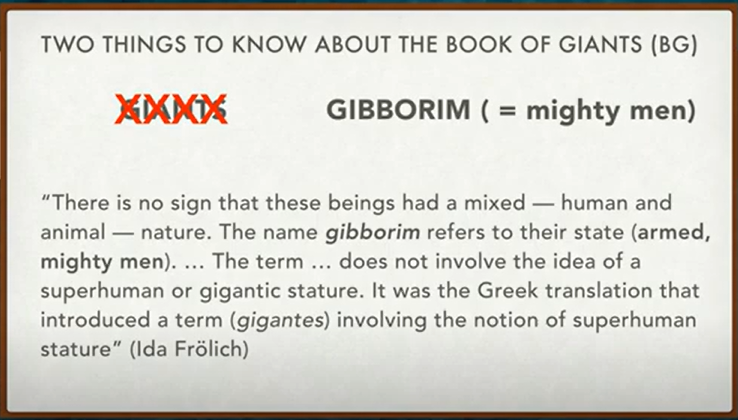

First of all, there are no actual “giants” in the Book of Giants. The word translated as “giants” is gibborim, which means something like “mighty men.”

According to Ida Fröhlich, among others:

There is no sign that these beings had a mixed—human and animal—nature. The name gibborim refers to their state (armed, mighty men). … The term … does not involve the idea of a superhuman or gigantic stature. It was the Greek translation that introduced a term (gigantes) involving the notion of superhuman stature.”

This is important to know because the Book of Giants, like the Book of Moses, is mainly concerned with Enoch’s dealings with wicked people—the all-too-human gibborim.

Both books differ from 1 Enoch’s Book of Watchers, which relates Enoch’s dealings with wicked superhumans—fallen angels with a fantastical physical form.

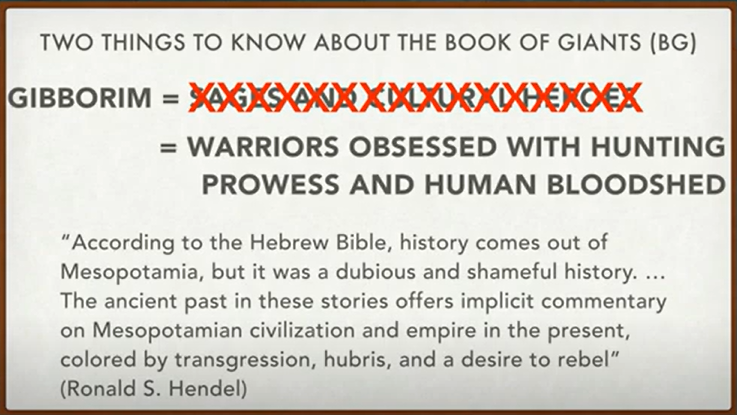

A second important thing to know is that BG is somewhat of a critique of Mesopotamian civilization—a parody of the near neighbors of the Israelites in the east.

While Mesopotamian legends tell stories of the mighty deeds of their great sages and cultural heroes, BG paints a different picture. It describes the gibborim as arrogant warriors, obsessed with their hunting prowess and human bloodshed.

Enoch

Ronald Hendel writes:

According to the Hebrew Bible, history comes out of Mesopotamia, but it was a dubious and shameful history. … The ancient past in these stories offers implicit commentary on Mesopotamian civilization and empire in the present, colored by transgression, hubris, and a desire to rebel.”

Hendel’s brief description of the culture of the people to whom Enoch preached gives us the key context needed to understand the story of Enoch in BG and the Book of Moses.

In 1976-77, Hugh Nibley rapidly produced one long, heavily footnoted article after another each month for a series about ancient Enoch manuscripts and Moses 6–7 in the Church’s Ensign magazine.

As he was finishing the last article in the series, he received—just in time—a long-awaited volume describing fragments of the Book of Giants.

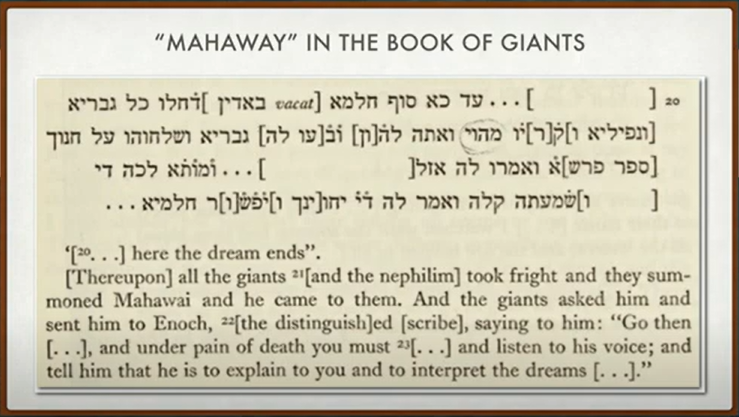

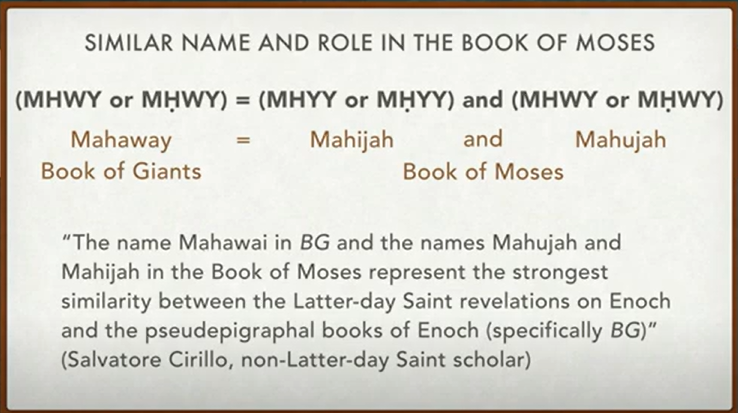

If you look closely at the pages in his personal copy, you will see that he circled the Aramaic version of the name “Mahaway.”

This unusual name matched the only other named character in Moses 6–7 besides Enoch himself.

Though different scholars render the English version of the names with different vowels, most agree that the names are equivalent.

For example, non-Latter-day Saint scholar Salvatore Cirillo concluded:

The name Mahawai in BG and the names Mahujah and Mahijah in the Book of Moses represent the strongest similarity between the Latter-day Saint revelations on Enoch and the pseudepigraphal books of Enoch (specifically BG).”

This important discovery caught the attention not only of Cirillo, but also of at least one other non-Latter-day Saint scholar, Matthew Black—a co-editor of the first English translation of BG.

The full story of Matthew Black’s impromptu visit to BYU to learn more about the Book of Moses is told for the first time in full in the book Hugh Nibley Observed.

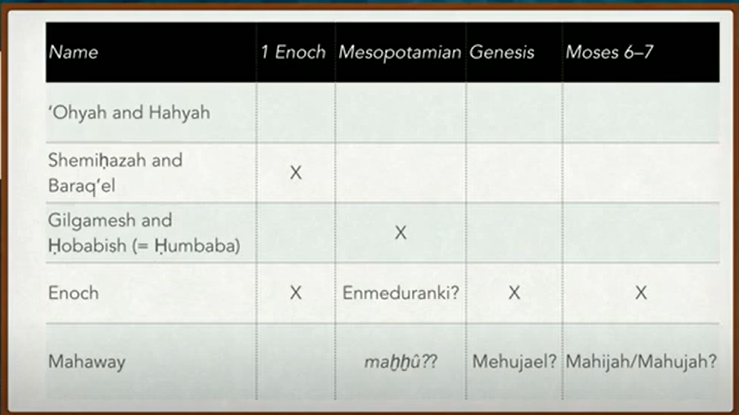

This table summarizes the results. Prominent names with similar characteristics are grouped together in each row.

To begin, remember that there are only two names mentioned in Moses 6–7: Enoch and Mahijah/Mahujah.

As for BG, scholars have observed that it is unique among contemporary Jewish apocalyptic literature because it actually provides names for some of the gibborim.

In the full chapter of the conference proceedings, it is argued that Enoch and Mahaway—the same two names that appear in the Book of Moses—are the best candidates for historicity when compared with the others.

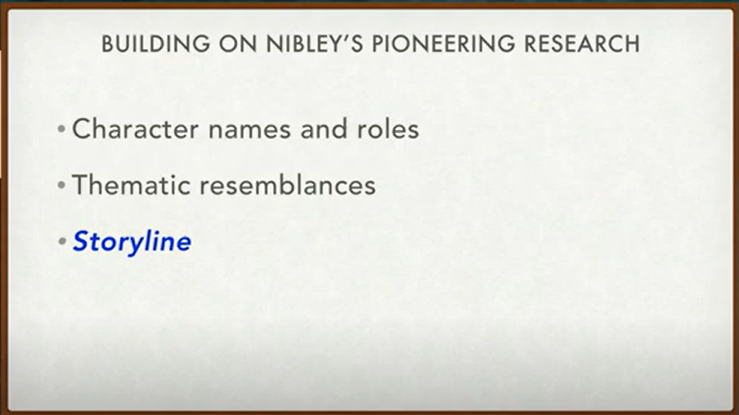

Next, let’s examine thematic resemblances between BG and the Book of Moses Enoch account.

Nibley found some very interesting parallels, but new textual discoveries have now led to many more.

Thematic Resemblances

Now let’s examine the thematic resemblances between the Book of Giants and the Book of Moses’ Enoch account—and it only gets better and better.

Nibley was really on to something. He identified a few key parallels and pointed them out, some from other ancient Enoch books.

But with new textual discoveries, we are finding more and more connections specifically in the Book of Giants.

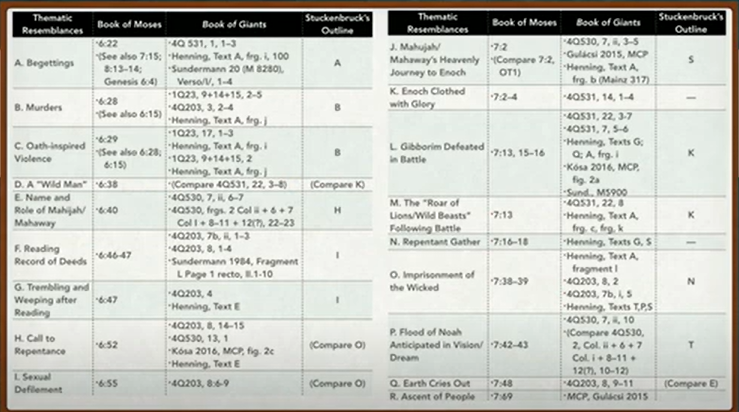

Let me show you eighteen major thematic resemblances between the Book of Moses and the Book of Giants. Each one is sourced in multiple ways from different fragments and different copies of the BG text.

The eighteen parallels are displayed here in tiny print, arranged in the same order as they appear in the Book of Moses.

In the rightmost column, you can see the results of BG scholar Loren Stuckenbruck’s detailed analysis, where he worked to reconstruct the story sequence of the surviving fragments of BG.

What’s most fascinating is that not only do we see these eighteen specific thematic parallels between BG and Moses 6–7, but they also appear in practically the same sequence.

Resemblances

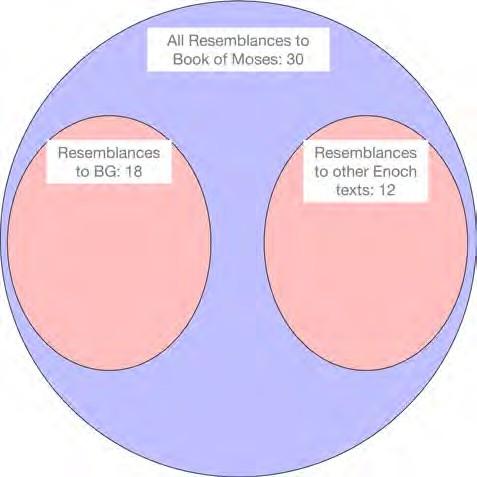

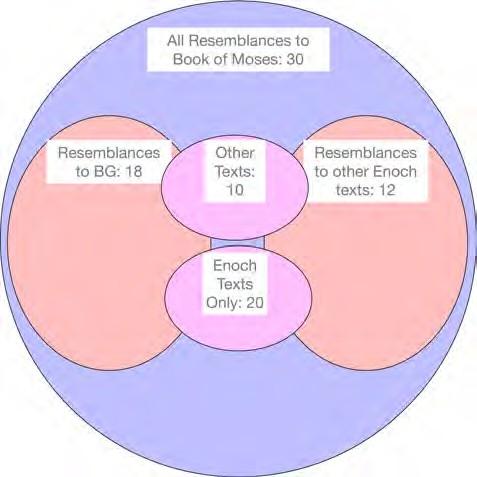

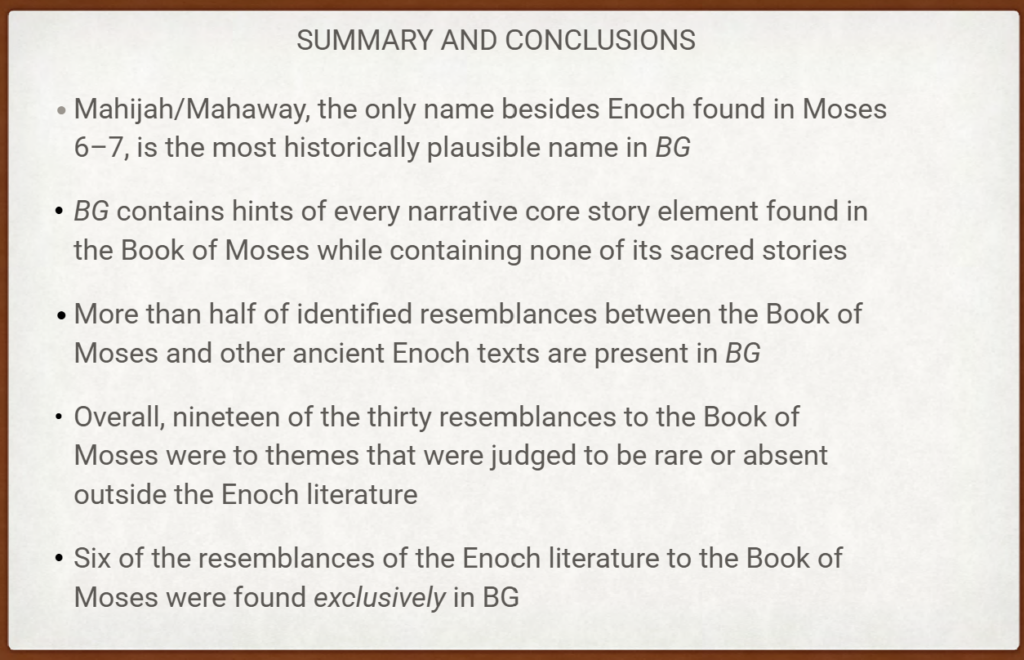

Let’s take a moment to discuss the number of resemblances.

A first question might be: “What proportion of the identified thematic resemblances in Moses 6–7 come from BG versus other ancient Enoch texts?”

The answer? 18 out of 30—that’s nearly two-thirds of all identified parallels—are found in the Book of Giants.

Beyond the high density of these resemblances in BG, it’s also crucial to remember that they appear in almost identical sequence to the Book of Moses.

This provides a strong comparative indicator, significantly reducing the likelihood that these similarities are just coincidence.

Of course, some of the thematic resemblances between Moses 6–7 and ancient Enoch texts are stronger and more specific than others.

To assess this, we needed to determine how many of these parallels could also be found in the Bible or other ancient Jewish texts, versus how many were unique to Enoch texts.

The results? Impressive.

Out of the 30 identified thematic resemblances, a striking 20 were rare or entirely absent outside of Enoch literature.

The Significance

This tells us something significant:

The Book of Moses is not merely drawing from common biblical or Second Temple themes—it is deeply tuned into motifs that are specifically Enoch-related.

This further strengthens the case that the Moses account of Enoch aligns with authentic ancient Enoch traditions rather than being a product of later interpolation.

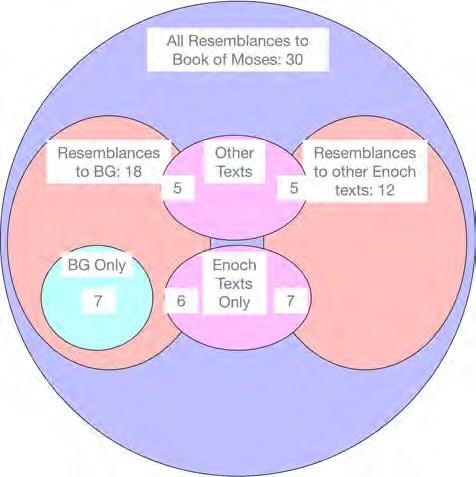

We have already seen that Moses 6–7 contains more thematic resemblances to the Book of Giants (BG) than to all other ancient Enoch literature combined.

But here’s the next question: How many of these resemblances are unique to BG?

The answer: 7 out of BG’s 18 resemblances are found only in BG.

This means that while the Book of Moses aligns with other ancient Enoch texts in many ways, it has a particularly strong and unique connection to the themes of BG.

This deepens the case that Moses 6–7 is not just loosely connected to ancient Enoch traditions but is especially aligned with the themes found in the oldest known Enoch manuscript, reinforcing its antiquity and authenticity.

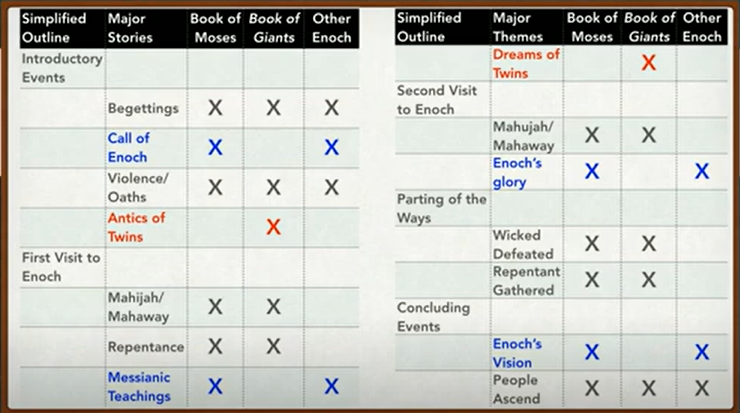

Storyline

An investigation was undertaken to determine which major elements of the storyline in the Book of Moses are also found in BG and other ancient Enoch literature.

This is an important step in understanding how Moses 6–7 fits within the broader tradition of ancient Enoch texts. By comparing key narrative elements, we can see how BG and the Book of Moses align not just in themes, but also in structure and plot progression.

The table summarizing the results of this investigation reveals some interesting patterns:

- Core Narrative Elements (Black)

- These are the essential story components in the Book of Moses, and they are always present in some form within BG.

- Sacred Teachings, Heavenly Encounters, and Rituals (Blue)

- These are completely missing from BG, even though they are found in other ancient Enoch texts.

- BG-Unique Themes (Red)

- These are nowhere else in Enoch literature, mostly involving the antics of the twins ‘Ohyah and Hahyah’, which seem like embellishments added to make the story more engaging.

Key Observations

- BG = All Black and Red, No Blue

- BG retains core narrative elements from the Book of Moses but omits all sacred elements.

- The sacred stories missing from BG do appear in other ancient Enoch texts, suggesting they were intentionally removed from BG.

- Possible Explanation

- BG may have originated from the same Enoch tradition as the Book of Moses, but over time, it was edited to remove sacred material.

- Early Christian precedents show that new initiates were sometimes given shortened versions of sacred texts, with deeper teachings reserved for the initiated.

Now, let’s dive into two key storyline examples, starting with Mahijah’s two encounters with Enoch.

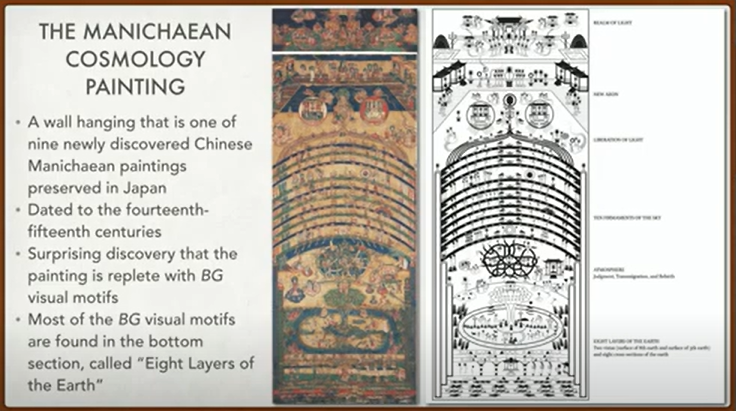

Manichaean Cosmology

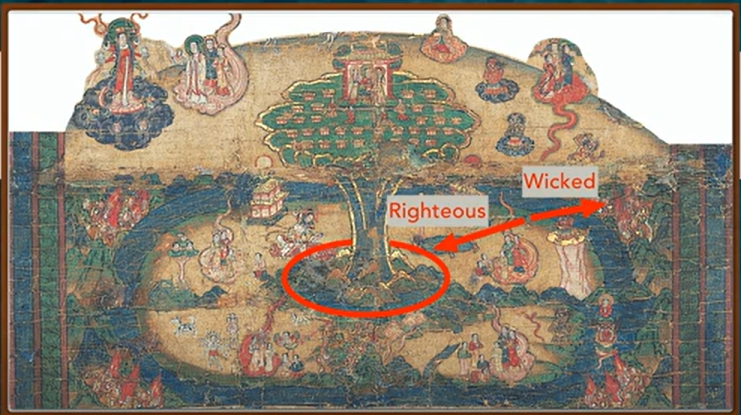

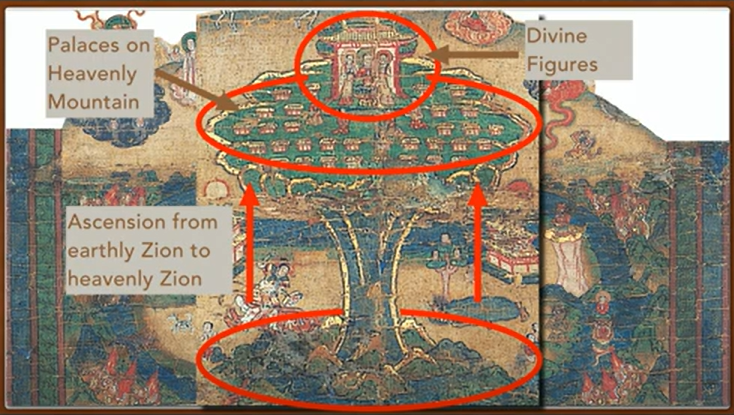

One of the exciting discoveries in recent years is the Manichaean Cosmology painting, a 14th or 15th-century wall painting that traces back to Manichaean traditions from around the turn of the first millennium. What’s fascinating is that most of the themes in this painting are actually related to the story of Enoch. This means we can now use an ancient Chinese painting—one that connects back to the time of Christ—to help illustrate Enoch’s story. It’s fun to see how they depicted Enoch and how these paintings were used for teaching in the Manichaean tradition. In some cases, they even help fill in gaps in what we know.

Most of what I’ll talk about today comes from this bottom-most section of the painting. You can see the four continents of the earth below a large tree-like mountain—in East Indian tradition, this is called Mount Sumeru, a sacred center place. The plane below represents the earthly realm, while the area above symbolizes a heavenly plane.

And here’s what Enoch was thought to look like. He’s surrounded by four angels, though they’re a bit hard to see in this image—it’s not the best resolution.

The Story

Now, let’s talk about the story. In the Book of Moses, Enoch preaches repentance to the people from a “book of remembrance” in which their wicked deeds were recorded. In ancient Enoch literature, the equivalent record is written on two tablets.

The Book of Moses tells us that Mahijah was present for Enoch’s teaching—that’s Moses 6:40. We don’t really know who Mahijah was or what he was doing there, but he asked Enoch a direct question: “Tell us plainly who thou art and from whence thou comest.”

Although there’s no explicit record of Mahijah’s first visit in the Book of Giants, some fragments refer to either a first or second journey to see Enoch. So, it’s clear he visited twice.

This is where the Book of Giants fills in the gaps. It says that Mahijah was sent to Enoch by the prominent gibborim to find out what was going on. His role is hinted at in his very name.

His Name

Prominent biblical scholars suggest his name could be linked to the Akkadian word mahu—though there are other possibilities, this is the one I prefer. In Old Babylonian texts, mahu refers to a certain class of priests and seers. Their role? Among other things, the royal archives of Mari describe mahu (or Mahuja/Mahaja) as intermediaries and messengers, bringing warnings from the gods to the king.

That description perfectly matches Mahijah in the Book of Giants—some scholars have even called him “the messenger par excellence” of the gibborim.

What’s fascinating is that Hugh Nibley pointed this out back in 1976—without knowing about this specific derivation. Yet, he still recognized that in the Book of Moses, Mahijah serves in one role only: as a messenger. A perfect match.

So there we are. Here are some of Enoch’s listeners, likely some of the gibborim, based on other commentary on this painting. And some of them are converted.

The Book of Moses tells us: “As Enoch spake forth the words of God, the people trembled and could not stand in his presence” (Moses 6:47). The Book of Giants gives a parallel account, saying that “they prostrated and wept” before Enoch when he read to them from the two tablets.

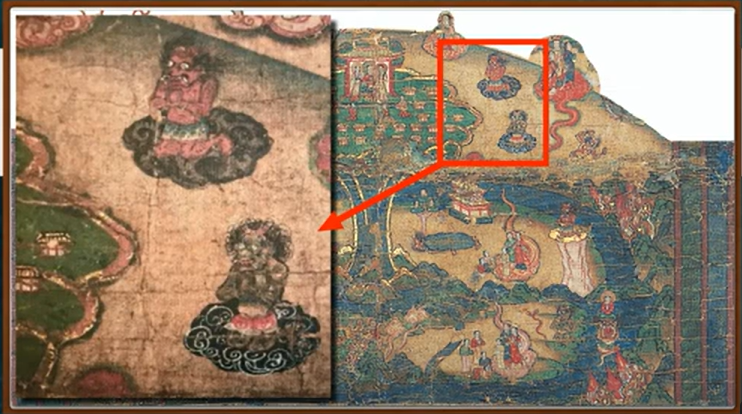

The Lone Figure

Now, in another part of the painting, a lone figure kneels repentantly on what appears to be the only other mountain in the scene. It resembles the sacred mountain, and it’s positioned closer to the center than the others who are also kneeling in repentance in the upper right-hand corner.

As far as I know, no BG scholar has yet attempted to identify this unique and highly prominent figure. But to me, it seems evident that the best candidate is Mahijah/Mahaway.

And why would a repentant Mahijah/Mahaway be alone on a mountaintop? Well, the missing pieces of the story come from the Book of Moses.

To answer this question, we need to look at Mahijah/Mahaway’s second encounter with Enoch. Unfortunately, we can only give a brief “fly by” version of the story.

Second Encounter

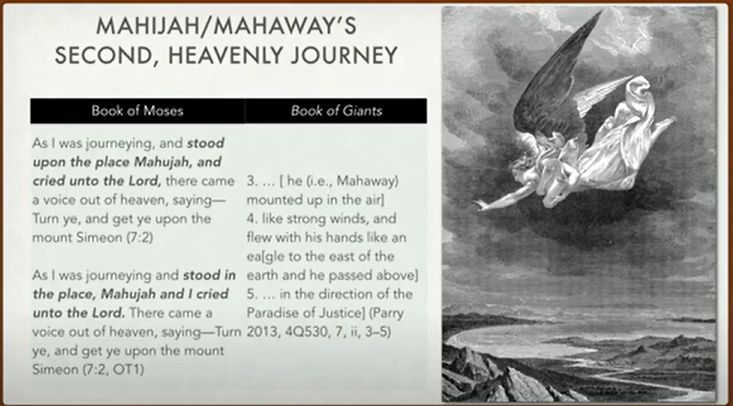

From the Book of Giants, we learn that Mahaway had to mount up “in the air like strong winds” and “fly like an eagle” to reach a distant paradisiacal place where he met Enoch.

The Book of Moses describes this moment in a similarly intriguing way. It tells us that Enoch “stood upon the place” when God spoke to him. Kent Brown has pointed out that in a biblical context, references to “the place” (Hebrew maqōm, Greek topos) often describe a special or sacred location.

Now, in an attempt to argue that Joseph Smith borrowed this story from BG, non-LDS scholar Salvatore Cirillo claimed: “The emphasis that [Joseph] Smith places on Mahijah’s travel to Enoch is eerily similar to the account of Mahaway to Enoch in [BG].”

However, Cirillo missed a critical detail—the Book of Giants wasn’t discovered until 1948, more than a century after the Book of Moses was published. So, the idea that Joseph Smith could have copied from BG is simply impossible.

In the canonized version of the Book of Moses, we read that “the place” is called “Mahujah”, which is generally considered a variant of the name “Mahijah.”

However, in Joseph Smith’s original dictation manuscript (OT1), “Mahujah” was not a place name but a personal name. The original manuscript suggests that Mahujah and Enoch prayed together in “the place” before Enoch ascended to Mount Simeon to be transfigured. In this earliest version, the verse reads: “Mahujah and I cried unto the Lord”, implying that Mahujah actively participated in the events.

Interestingly, there’s also the idea that Mahijah received a new name, becoming Mahujah, in that sacred place—just as Abram was renamed Abraham in a covenant-making event.

Mount Simeon

Here we have the first portrait of Mahijah.

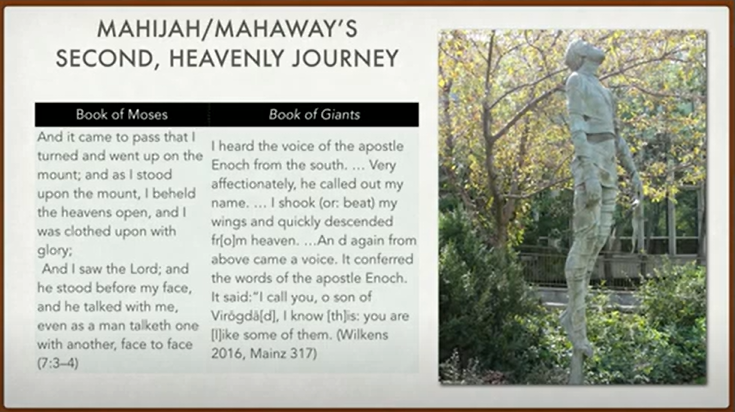

The Book of Moses makes it clear that both Enoch and Mahijah were commanded to ascend Mount Simeon—the phrase “Turn ye” uses a plural pronoun. However, it seems that only Enoch responded immediately: “I turned and went up on the mount” (Moses 7:3).

As Enoch stood upon the mount, the heavens opened, and he was “clothed upon with glory.” The process of Enoch’s transformation is described in greater detail in 2 Enoch and 3 Enoch. These texts outline a two-step initiatory procedure, where Enoch was first initiated by angels and then by the Lord Himself.

In 2 Enoch, God commands His angels: “Extract Enoch from (his) earthly clothing. And anoint him with my delightful oil, and put him into the clothes of my glory.”

In 3 Enoch, after this transformation, Enoch so closely resembled God that he was even mistaken for Him.

Mahaway’s Final Decision and Tragic End

Unlike Enoch, Mahaway does not follow as he departs. In the Book of Giants, Enoch seems sad about this. Many scholars note that Enoch’s final plea to persuade Mahaway includes a pointed reference to his parentage: “I call you, oh son of Virogdad, I know [th]is: you are like some of them.”

This warning suggests: “You are too much like some of them.” In other words, Mahaway’s hesitation to fully embrace Enoch’s call made him dangerously similar to the wicked gibborim.

If we allow some speculation, Mahaway’s story in BG can be seen as a parable—similar to Jesus’ encounter with the rich young ruler. Just as Christ invited the rich young ruler to forsake all and follow Him, Mahujah/Mahaway may have been offered eternal life if he had followed Enoch’s path completely. However, he ultimately refused to take the final step.

The original manuscript of the Book of Moses describes Enoch and Mahujah crying together in a sacred place. Enoch affectionately warns him, but Mahujah/Mahaway ultimately sides with the wicked and perishes.

The Book of Giants records a lament for his death:

“Slain, slain was that angel who was great, that messenger whom they had. Dead were those who were joined with flesh.”

Earthly Work

Reflecting on Mahaway’s story, one thought stands out: One never wants to leave this life without accomplishing their work on the earth.

This reminds me of Hugh Nibley, who was given a patriarchal blessing stating that he would live to complete his work. As he labored for decades on his final magnum opus, One Eternal Round, he would joke that his delays were keeping him alive.

Then one day, unexpectedly, he allowed friends to take dozens of boxes of overlapping manuscripts. It seemed he had finally realized that this was not the unfinished work he had been kept alive to complete—that work was something else, something very different.

Hugh Nibley’s Final Lesson

This photo captures Hugh Nibley with his son Alex and a granddaughter during a period when he was spending significant time in the hospital.

Around this time, his friend Louis Midgley shared a touching experience:

Phyllis, Hugh’s wife, called Midgley and urged him to visit. When he arrived, Hugh was lying in a hospital bed, barely able to speak. He would mumble, and they would talk back and forth as best as they could.

Then, two Relief Society sisters knocked on the door. They had brought Hugh dinner. As soon as they saw him, they rushed over, hugged him, and kissed him. Hugh wept.

After they left, Phyllis turned to Midgley and asked, “Did you notice that?”

Midgley replied, “Yes, I did.”

Phyllis continued, “Have you ever seen my husband show emotion?”

Midgley answered, “No, never.”

She explained: “He couldn’t.” Hugh had grown up in a strict Victorian home, where showing emotion was not allowed.

Yet in his final days, reduced to lying in bed, unable to talk, he told Phyllis:

“Phyllis, I have been kept after school by the Lord so I could learn a lesson that I needed to learn before I pass away.”

Joy

That was the lesson he learned.

Many of you will recall the life-changing near-death experience Nibley had as a young man. But in his final months, he had a second visit to the other side—one that prepared him to let go of unfinished projects and embrace whatever the Lord had in store for him next.

In a newly released video, Brent Hall recounts this experience, and Shirley Ricks shares Hugh’s own words about what he learned:

Brother Nibley said he didn’t sleep a wink last night. He knew where he was going and what the purpose of everything was.

Brent Hall asked, “So, Brother Nibley, can you share with us what that purpose is?”

Nibley paused and then simply replied:

“Joy.”

He went on to explain that the glory of God is intelligence—that when we pass on, we have great intelligence, which allows us to solve problems. And solving problems brings joy.

Then, with confidence, he reassured them:

“Don’t worry a minute about what’s going to happen after this life.”

He was actually looking forward to it. At one point, he even said:

“I could go this evening, or even tomorrow.”

And he sounded very pleased with the prospect.

You will recall from the Book of Moses that the righteous were brought to a place of safety, where “the Lord came and dwelt with his people. … And the Lord called his people ZION.”

According to the Book of Giants, four angels ultimately led the wicked away from the sacred center to their destruction in the east, while the righteous journeyed westward to inhabit cities near the holy mountain:

“One half of them eastwards, and the other half westwards … towards the foot of the Sumeru mountain, into thirty-two towns which the Living Spirit had prepared for them in the beginning.”

The mention of divinely prepared “towns” in BG recalls descriptions of the City of Enoch in the Book of Moses.

Additionally, BG describes the righteous dwelling “on the skirts of four huge mountains.” This imagery significantly parallels Moses 7:17, which states:

“They were blessed upon the mountains, and upon the high places, and did flourish.”

Divine Association

Book of Giants scholar Gábor Kósa identifies the thirty-two palaces at the top of the tree-like Mount Sumeru as having a divine association. This is reinforced by the presence of three divine figures in front of a larger thirty-third palace, where:

The central figure is seated on a lotus throne, with two acolytes standing on either side.

Kósa suggests that this imagery confirms the purely divine nature of the Manichaean Mount Sumēru.

Additionally, Kósa notes that the mountain’s tree-like iconography echoes descriptions of the mountain of God and the Tree of Life.

While Kósa acknowledges the existence of thirty-two towns at the base of the mountain, he does not explicitly connect them to the thirty-two palaces at the top. He observes that no text currently explains how this relationship came to be

To make sense of these anomalies, we should remember that the Book of Moses describes how earthly Zion, symbolically located at the foot of the mountain of the Lord, was transformed into a heavenly Zion.

Redemptive Descensus

This process represents a redemptive descensus—a descent initiated by Jared and his brethren—that ultimately led to the glorious ascensus under Enoch.

As recorded in Moses 7:69:

Enoch and all the people walked with God, and he dwelt in the midst of Zion; and it came to pass that Zion was not, for God received it up into his own bosom; and from thence went forth the saying, Zion is fled.”

This transformation mirrors the heavenly ascent represented in the Book of Giants, further reinforcing the idea of a divinely guided journey from the earthly realm to the heavenly presence of God.

Earlier in the presentation, I mentioned my conjecture that Enoch’s story of the first days is also our story—the story of the last days. Whether by sheer coincidence or divine design, the symbolic geography shared by the Manichaean Book of Giants and the Manichaean Cosmology Painting appears to be mirrored in the itinerary of the gathering and layout of Joseph Smith’s City of Zion in Missouri.

This latter-day city is described in modern scripture in direct connection with descriptions of Enoch’s ancient city. Just as the righteous of Enoch’s day were remembered in BG as being divinely led westward, so too were the early Saints commanded by the Lord:

“Gather ye out from the eastern lands” and “go ye forth into the western countries”

(Doctrine and Covenants 45:64, 66)

A Hierocentric Place

This destination, in the middle of the continent, is identified as a sacred, central location—a hierocentric place.

- For Enoch’s people, this sacred center was Mount Sumeru, the mythical mountain in the middle of the world map.

- For the early Saints, the sacred center was “Mount Zion, which shall be the city of New Jerusalem”, a central location in North America.

- In revelation, this city of New Jerusalem is explicitly called “the center place” or “center stake.”

Thus, in the Manichaean depiction of the Book of Giants, in the Book of Moses, and in the Latter-day vision of Zion, God dwelt in the midst—both literally and symbolically central in the eyes of His people.

Where in all the ancient Enoch traditions do we find anything resembling Enoch’s gathering of repentant converts to cities in the mountains—preparing as a people for an eventual ascension to the bosom of God?

Only in BG and the Book of Moses.

It does not seem unreasonable to conclude that an Enoch book, which was buried until 1948, and an Enoch book, which was independently translated in 1830, may be related—despite their differences in province, perspective, and contents.

It is my hope that scholars interested in the origins of the Book of Moses will take into serious account the literary affinities between Moses 6–7 and the ancient Enoch literature as they continue their work.

In Closing

In closing, I want to express my love for the Book of Moses. It is a joy and a privilege to live in a day where this sacred text is widely available, allowing us to immerse ourselves in its inspiring stories and eternal truths. Just as prophets have spoken of God’s hand in modern technological advancements, I believe He is equally involved in the discovery and elucidation of ancient documents—ones that strengthen our testimony and increase our understanding of Restoration scripture.

I firmly believe that many more discoveries about ancient scripture are yet to come. Moreover, I believe that the Lord expects us to seek them out diligently, since only the Latter-day Saints hold the keys to fully understanding and applying them.

Hugh Nibley once wrote that discoveries in ancient digs and ancient texts, tangible artifacts that sometimes provide striking witnesses of the truths restored in our day, serve as a:

“Reminder to the Saints that they are still expected to do their homework and may claim no special revelation or convenient handout as long as they ignore the vast treasure-house of materials that God has placed within their reach.”

May we all resolve to search, study, and understand with greater diligence the “vast treasure house” of knowledge that the Lord has placed within our reach.

Thank you.

Scott Gordon:

So, there’s a lot in the book of Moses. There’s a lot in the Book of Giants. What is the one thing—if you could just summarize everything—what’s the one thing you wish all Latter-day Saints knew about the Enoch material in the book of Moses?

Jeff Bradshaw:

I am still very much impressed by the fact that Enoch seems to be the culminating story for a temple text. It’s no coincidence that we start with Adam and Eve in chapter five being obedient to the commandments of the Lord, having their posterity as they were commanded in the earlier chapters, and performing sacrifice—obedience and sacrifice—and ending, after having traversed all the other principles, with the law of consecration in Enoch. I think if we read the book of Moses, including the story of Enoch, as a temple text, it would be a wonderful thing.

Scott Gordon:

Are there any onomastic word plays with the book of Moses and the name Enoch?

Jeff Bradshaw:

Oh, wow. We should have Matthew Bowen here to talk about that. What I recall that he taught me is that it has a lot to do with teaching the word. The roots for “Enoch” and “initiatory” are tied together, and in many ancient texts where they’re doing plays on their name, he’s a hierophant. That means someone who initiates others—who kind of passes through the veil and has others follow him.

Scott Gordon:

So, I happen to have this book on my lap that you also have in front of you. Could you tell the crowd what that is again? Go ahead and tell us—what is it?

Jeff Bradshaw:

Yes, okay. So, this is the result of two conferences—I don’t know if there’ll be more or not, there might be—but it’s talking about why those of us who contributed, including editors such as Scott, believe that the book of Moses is an ancient text. It’s not okay to just think, “Joseph Smith made it up with a lot of nice stories.” There’s evidence from everything, from detailed textual work by people like John Carmack to Elder Hafen’s wonderful work in there from a temple text perspective. There’s Richard Bushman’s talk comparing it to the work of Eric Auerbach, Mimesis, and all kinds of perspectives. I think you’ll enjoy it.

Scott Gordon:

I really enjoyed, as I was looking at the manuscripts and such, how it talks about how the Book of Mormon is such a literary, historical book where you have stories and histories. Then, shortly after—almost no time at all—Joseph Smith does the book of Moses, and it is certainly not that kind of story. It’s much more heavenly, you know?

Jeff Bradshaw:

Yeah, apocalyptic.

Scott Gordon:

Apocalyptic, yes. It’s really fascinating.

Jeff Bradshaw:

I was going to say that this goes with what Nibley said: that whoever wrote the Book of Moses would have had to be an even greater genius than the writer of the Book of Mormon. So, I guess God in both cases.

Scott Gordon:

Yeah, and I think it’s interesting when people say, “Joseph Smith made this whole thing up.” You look at the Book of Mormon—that gives you one element. Then look at the Book of Moses—that is a completely different element. Then you look at the Book of Abraham, which gives, again, a completely different element. And then you look at the Doctrine and Covenants, which is different again. I think people who dismiss Joseph Smith—it makes it very difficult to dismiss him just out of hand.

Jeff Bradshaw:

I wish it was more difficult to dismiss him. Yes, but it’s hard for me to dismiss it.

Scott Gordon:

So, I wish we had this book in the bookstore. We don’t yet. Do we know when it might be coming out?

Jeff Bradshaw:

So, I was just waiting to see these physical copies—which I got yesterday—to order them because sometimes the cover gets a little funny or whatever. But I just have to—well, Delayna can get with me after the event, and we can actually go ahead and order them today, as many as she wants. The Kindle versions are already up on Amazon, and the PDFs—she already has a copy.

Scott Gordon:

I was just going to say, we do have the PDF version up in our bookstore online. So, if you want to download this book in PDF format, you can just go to the FAIR Latter-day Saints bookstore and download it—as of about 10 minutes ago. We just got it up there.

Jeff Bradshaw:

Thank you, Scott. Thank you, DeLayna, and everybody.

Scott Gordon:

So, we look forward to having this. We’ll make sure we let everyone know when it’s available in our bookstore so that people can order it. Thank you for all that you do. I know you do a lot with Interpreter and a lot with this. I think your leadership on the Book of Moses scholarship has been outstanding. So, thank you so much.

Jeff Bradshaw:

Thank you. Nice to have you as a friend, Scott.

coming soon…

Are the Enoch parallels coincidental?

The sequence, specificity, and frequency of these similarities make them highly improbable as mere coincidence.

How could Joseph Smith have known about these ancient texts?

The Book of Giants was discovered in 1948—over a century after the Book of Moses was revealed—making textual dependence impossible.

The antiquity of the Book of Moses.

Strengthening faith through historical and textual scholarship.

The enduring relevance of Enoch’s teachings in modern times.

Share this article