Barrett Burgin outlines key principles to guide the creation of films within the Latter-day Saint community. These pillars emphasize authenticity, diversity, artistic excellence, collaboration, and the importance of reflecting gospel values. The speaker encourages filmmakers to produce content that not only entertains but also uplifts and inspires, contributing to a broader cultural impact aligned with the faith’s teachings.

This talk was given at the 2022 FAIR Conference on August 5, 2022.

Barrett Burgin, an award-winning filmmaker known for works like Cryo and The Next Door, explores the potential of Latter-day Saint cinema and its intersections with technology, media, and immortality.

Transcript

Barrett Burgin

Introduction

Thank you everyone. It’s such a blessing to be here with you today. I’d like to talk about Five Pillars for a new wave of Latter-day Saints cinema. I’ll explain, as I get into my presentation, exactly what I mean by that.

About Me

First, you are probably wondering “who the heck are you? We’ve never seen you before. Who’s this random guy?” I’m Barrett Burgin, residing in Springville with my wife, Jessica, and our young daughter, Roxy. Both Jessica and I work in the film industry together. I graduated from BYU’s film program about two and a half years ago. I make movies, write about movies, and particularly focus on Latter-day Saints in movies and Latter-day Saints making movies. And some of those concepts.

Throughout my presentation, when I use terms like “Mormon” and “Mormonism,” I do so within cultural contexts and quotes, respecting President Nelson’s commission to emphasize the true name of The Church as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and our true identities as Latter-day Saints.

Latter-day Saints and LDS Concepts in Film

In 2017, I wrote an essay and published some research that served as a sort of manifesto on the marketability of Latter-day Saint ideas, concept, doctrine and culture in cinema. It was published as part of a book titled “Mormonism in the Movies.” It predicted an increasing trend, year over year, of exploring Mormonism in media, encompassing not just our church but also fundamentalism, break-offs from the Church, and historical aspects.

I firmly believe that the aspects and ideas related to Mormonism, broadly defined, are highly marketable to a general audience. I have tested this thesis in my own work, to pretty good effect.

My short film The Next Door is a psychological thriller about missionaries. It’s not uplifting or preachy, just focusing on missionaries and their investigator who goes missing. They embark on a journey to figure out where he’s at, framed as a noir detective movie. The film is currently on Prime Video.

One response from the Flathead Lake International Cinema Fest, a film festival, supported the thesis that people were interested. A judge mentioned

I seldom pause in the midst of judging films to write a filmmaker, but I wanted to do so in this instance. I’m not LDS, but I found your portrayal of missionaries to feel authentic and accessible. You humanized them for me, giving me a new appreciation for what it might be like to knock on doors all day/week/month.”

One of the reasons I think he found this film accessible is it wasn’t trying to persuade him of anything. It was just a story based on my experience as a missionary, and some of the interesting ideas I had while I was out there.

Father of Man

A few years later, I made another film with BYU, my capstone short film called Father of Man. It’s aimed more toward a Latter-day Saint audience and is available, or will soon be available on Deseret Video for streaming. While targeting a specific audience, I aimed to make it as accessible and universal as possible, exploring Latter-day Saint ideas, iconography, doctrines, concepts, etc.

The film won the Association of Mormon Letters award that year. The review stated,

Father of Man boldly envisions the unique LDS doctrine of Eternal Progression, therefore, post-mortal imperfection through its main character, Boyd, a flawed and unsupporting father. After experiencing an untimely death, he finds himself entrenched in weaknesses in the afterlife. The film bypasses common Protestant concepts of a perfect and carefree afterlife, instead leaning into a network of imperfect individuals on all sides of the veil, working together to repent, forgive, and reconnect for salvation.”

Cryo

Most recently, I finished a feature film co-written with my colleague, sold to Sabon Pictures, called Cryo. It’s my darkest picture, a sci-fi thriller murder mystery available on Apple TV, Prime Video, Google Play, Vudu, Direct TV, among other platforms. It won several awards in various festivals, and incorporates aspects of my faith as a Latter-day Saint.

This is not a movie tailored for a faith audience, specifically. It’s not particularly uplifting, but it is entertaining. It explores ideas and concepts that I, as a Latter-day Saint, am interested in, and it doesn’t shy away from that uniqueness. Not all reviews were great, but some were pretty good.

Cryo will melt your brain and will undoubtedly become the next streaming cult title once the audience discovers this gem of an indie film on their platform of choice.”

“I was surprised to find out that this was an indie film with a small budget because it definitely surpasses other high-budget films.”

“Cryo is a mystery thriller brimming with suspense, keeping you guessing, with no mention of Latter-day Saint concepts, which no one had any issue with because they were intertwined into the narrative.”

So, why am I telling you all this? It’s not to come and try to pitch my film work, I promise.

A New Wave of LDS Cinema

I want to give you some examples of what I’m proposing for a new wave of Latter-day Saint Cinema. There’s a whole history to Latter-day Saint Cinema, not super well-known but well-documented and published in depth by many great scholars and researchers.

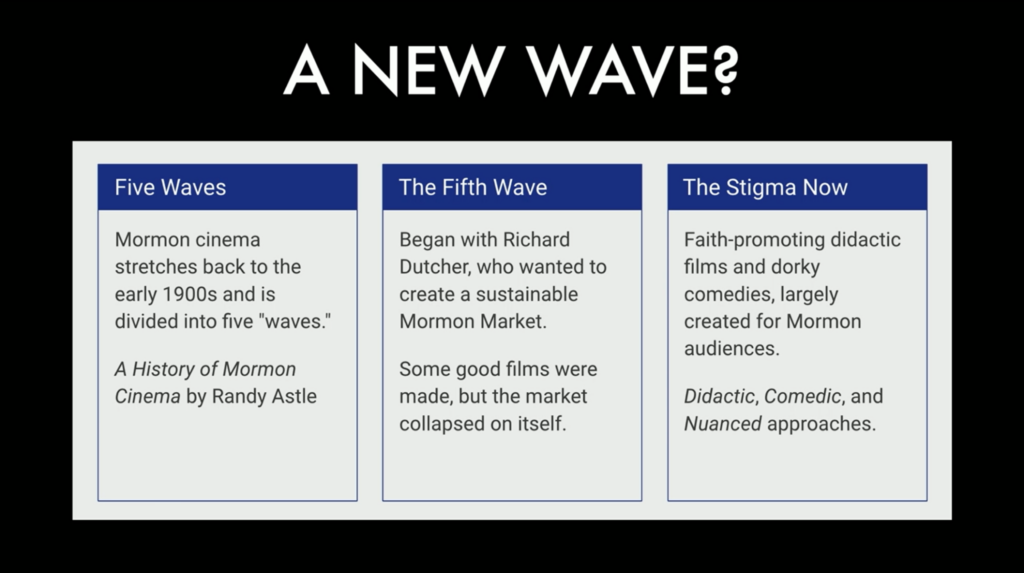

To give you a brief summary, what has been termed Mormon Cinema, I now call Latter-day Saint Cinema out of respect for proper terminology. Mormon Cinema stretches back to the early 1900s, divided into five waves, as found in A History of Mormon Cinema, an essay part of the BYU Studies book about Latter-day Saints and film.

These five waves span the past century, with the fifth wave widely seen as beginning with Richard Dutcher and Mitch Davis, known for films like God’s Army and The Other Side of Heaven, aiming to create a sustainable Mormon market. Some good films were made, but many writers and filmmakers agree that the market seemed to collapse in on itself. It’s not what it once was, and this is the stigma, particularly among my generation.

My Research

In a survey I conducted, I found that the stigma around Latter-day Saint cinema, or Mormon movies, among my generation is that they are faith-promoting didactic films, or dorky comedies largely created for Mormon audiences.

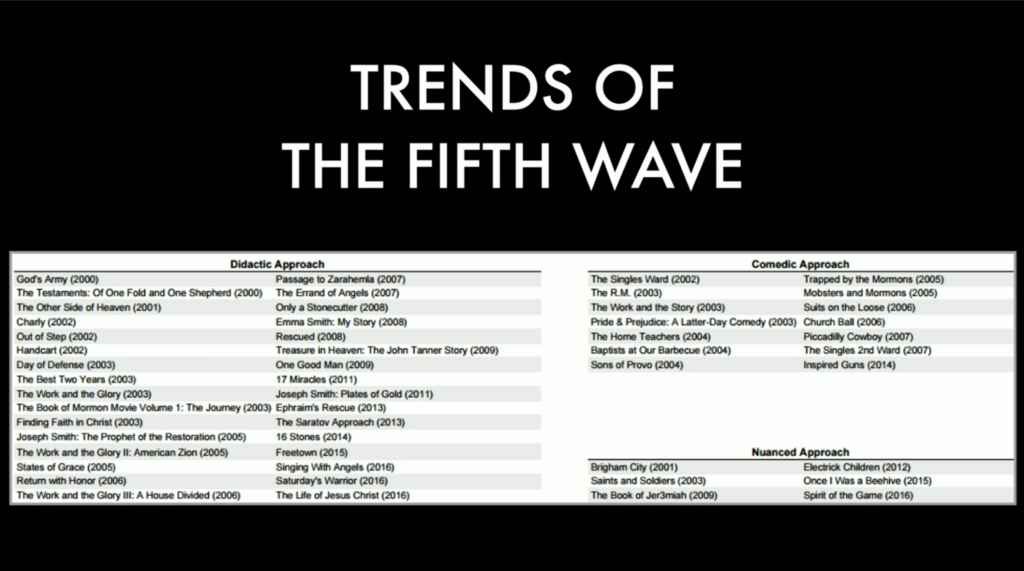

In my 2017 essay, I tried to categorize the films made by, for, and about Latter-day Saints, into three categories: didactic, comedic, and nuanced. Nuanced meaning ambiguous films that weren’t trying so hard to preach a message, but rather just trying to tell a good story, but were unabashedly Latter-day Saint in their context. Didactic is the largest group by far, followed by comedic, which includes self-referential films, and the smallest category is nuanced films. We’ll get back to that in a moment.

The Mormon Market

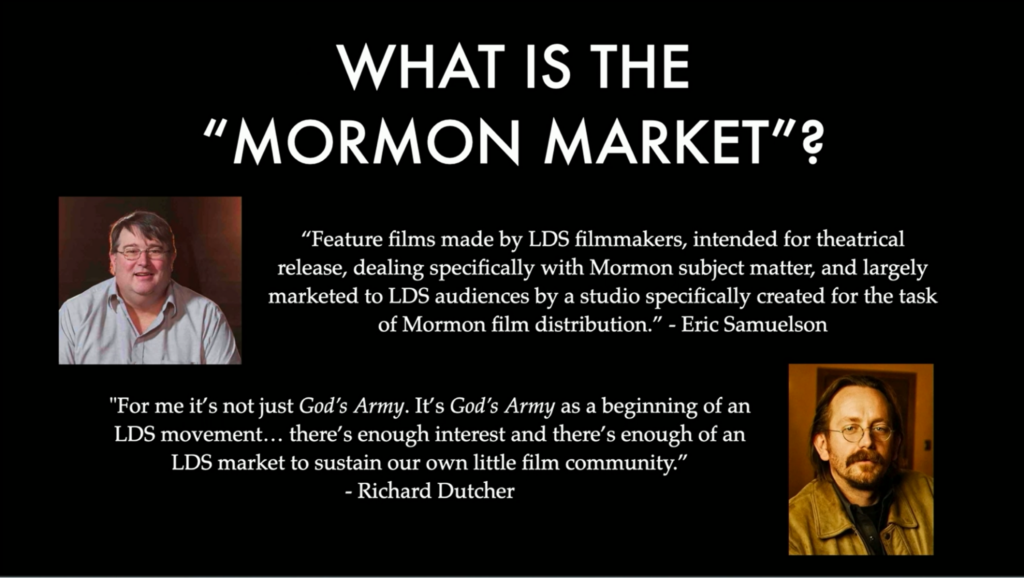

The Mormon market can be defined as feature films created by LDS filmmakers for theatrical release, focusing on Mormon subject matter and primarily marketed to LDS audiences by a studio established specifically for Mormon film distribution. Richard Dutcher, with the film God’s Army, aimed to build a market within the LDS community.

He said,

For me it’s not just God’s Army. It’s God’s Army as a beginning of an LDS movement… there’s enough interest and there’s enough of an LDS market to sustain our own little film community.”

Initially, there was a distinction between movies, TV, and stories about Mormons, and those made by Mormons for themselves. Richard Dutcher envisioned creating a niche for LDS films within the community.

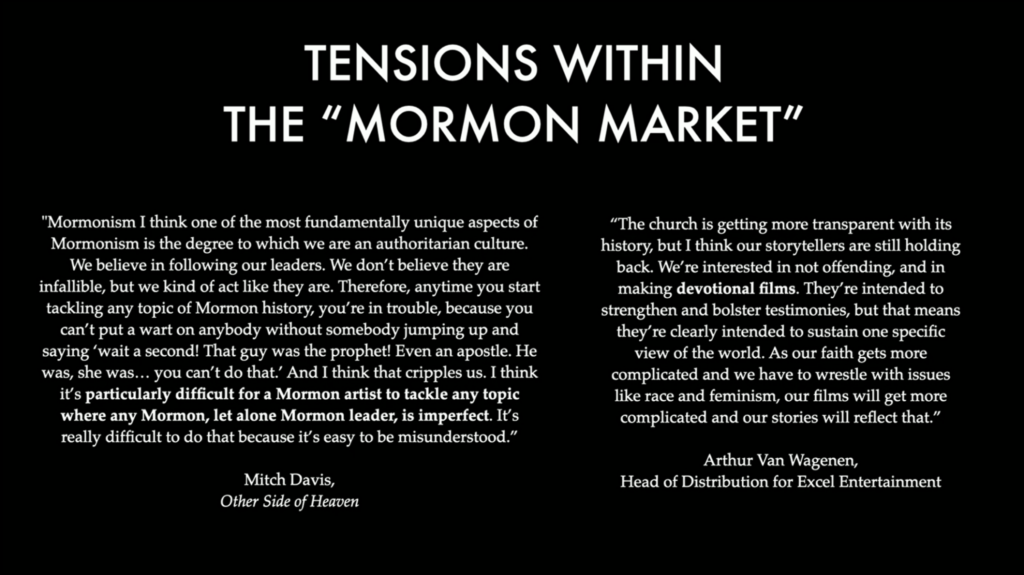

However, inherent tensions exist within the Mormon market, as Mitch Davis, director of The Other Side of Heaven, noted at an LDS Film Festival. He said,

I think one of the most fundamentally unique aspects of Mormonism is the degree to which we are an authoritarian culture.

We believe in following our leaders. We don’t believe they are infallible, but we kind of act like they are. Therefore, anytime you start tackling any topic of Mormon history, you’re in trouble, because you can’t put a wart on anybody without somebody jumping up and saying, ‘Wait a second! That guy was the prophet! Even an apostle. He was, she was… you can’t do that.’ And I think that cripples us.

I think it’s particularly difficult for a Mormon artist to tackle any topic where any Mormon, let alone Mormon leader, is imperfect. It’s really difficult to do that because it’s easy to be misunderstood.”

Arthur van Wagenen, head of distribution for Excel Entertainment, said, “The Church is getting more transparent with its history, but I think our storytellers are still holding back.” We’re interested in not offending, and in making devotional films. They’re intended to strengthen and bolster testimonies, but that means they’re clearly intended to sustain one specific view of the world.

As our faith gets more complicated and we have to wrestle with issues like race and feminism, our films will get more complicated and our stories will reflect that.

These proposals are not unprecedented, as evident from Arthur, and from Mitch, and truthfully, some of this is happening already, both from within and without, both favorable depictions, and not so favorable depictions.

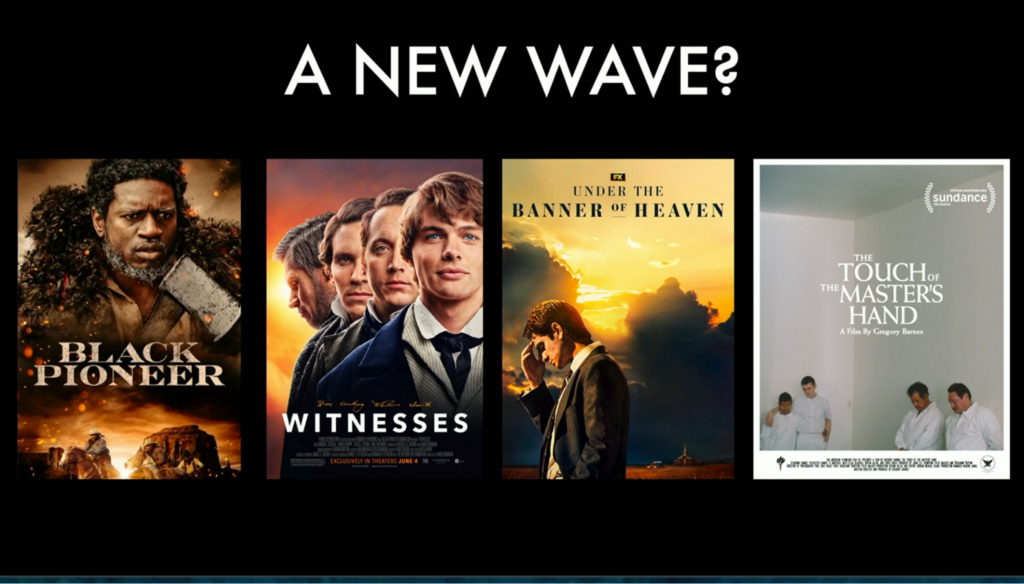

Films like My Name is Green Flake, recently renamed Black Pioneer on Paramount Plus for broader distribution, and Witnesses, discussed by Dan Peterson later, exemplify a nuanced approach to Latter-day Saint Cinema. These films aim for honesty, transparency, and engagement with various themes, while still being representative of Latter-day Saint perspectives.

Simultaneously, there is a surge in films created by former Church members or non-members, showcasing a growing interest in the subject. A prime example is Under the Banner of Heaven and the lesser-known The Touch of the Master’s Hand, a Sundance award-winning short film that diverges from the devotional genre into a somewhat mean-spirited comedy.

Five Pillars of Latter-day Saint Cinema

My proposal is to organize and look to five pillars for a new wave of Latter-day Saint Cinema. I don’t claim sole credit for these ideas, positioning myself more as an artist and organizer seeking to unite and identify cultural weak points in our storytelling. While recognizing that not everyone here may be filmmakers, I encourage you to observe what young, devoted Latter-day Saint filmmakers and artists are doing.

Understanding our perspective may contribute to reshaping and building a new, sixth wave of Latter-day Saint Cinema. If we do not tell our own story, someone else will.

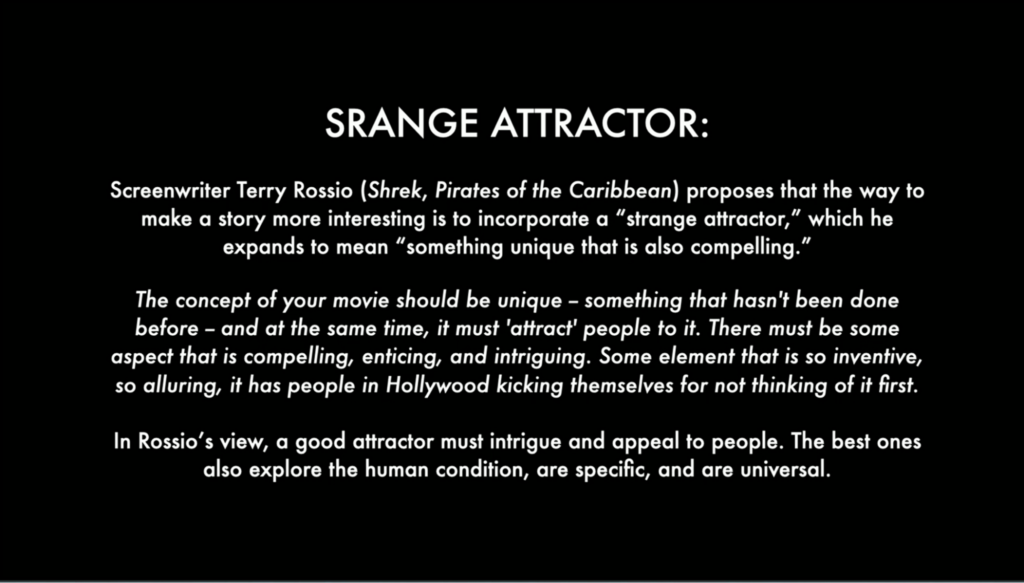

What do I mean by “strange attractor?” Screenwriter Terry Rossio, who wrote Shrek, Pirates of the Caribbean, and other very successful, popular films, proposes that the way to make a story more interesting is to incorporate a “strange attractor,” which he expands to mean something unique, that is also compelling. He goes on to say,

The concept of your movie should be unique-—something that hasn’t been done before-and at the same time, it must ‘attract’ people to it. There must be some aspect that is compelling, enticing, and intriguing. Some element that is so inventive, so alluring, it has people in Hollywood kicking themselves for not thinking of it first.”

In Rossio’s view, a good attractor must intrigue and appeal to people. The best ones also explore the human condition, are specific, and are universal.

Our Faith as a Strange Attractor

Personally, I’ve observed that our faith movement functions as a strange attractor. Friends who have submitted scripts or pitched concepts get more attention outside of our community, when incorporating Latter-day Saint elements, not in a preachy or protective way, but in an honest portrayal, expressing the uniqueness of our community. These stories garnered attention, feedback, and prestige.

Beyond anecdotal knowledge, I aim to demonstrate the extent of the strange attractor effect within our unique, and still largely misunderstood faith, goes.

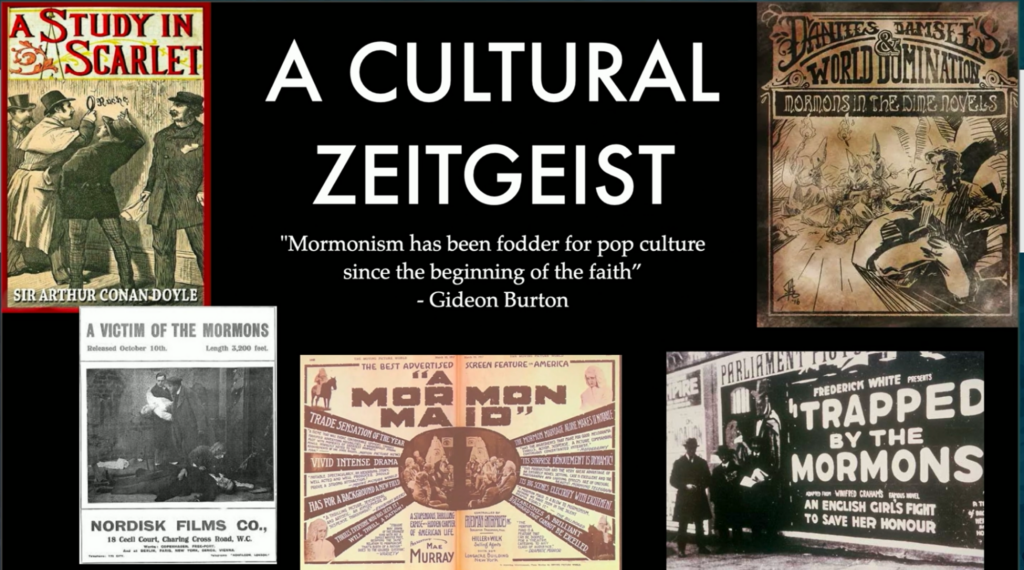

Gideon Burton once said, “Mormonism has been fodder for pop culture since the beginning of the faith.”

Sherlock Holmes’ first mystery involved the Danites and Mormons in Utah, and how dangerous they might be. Films and Dime novels such as A Mormon Maid, and Trapped by the Mormons, which were a huge deal. Dime novels about Porter Rockwell and the avenging angel that he might be, all of this kind of mystique and interesting fascination came because the history was so different from what people were used to.

Over the years, depictions persisted in musicals and films, offering varying critiques and fairness, some more nuanced and balanced, perhaps inaccurate, but trying to explore deeper themes and ideas. They have been consistently inspiring, creative fiction for outsiders.

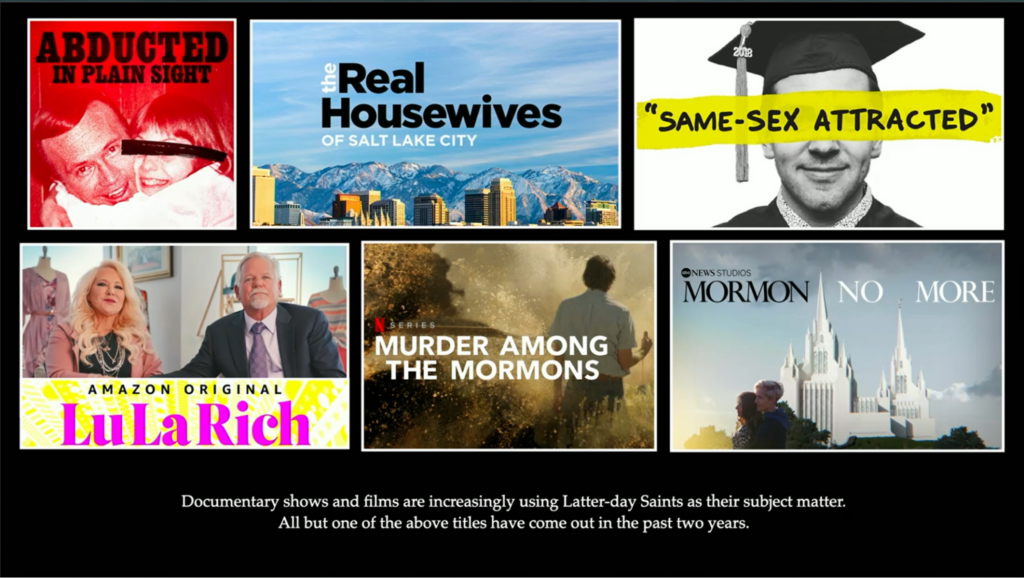

However, in the last decade, this recent trend has intensified to a rate that most of you are now noticing. Under the Banner of Heaven, extensively discussed, is worth scrutinizing. However, I’ll highlight other examples.

Examples

Gritty westerns frequently feature Latter-day Saint characters. AMC’s Hell on Wheels depicts Brigham Young as a main supporting character, vying to get the railroad to come through Salt Lake City instead of north through Ogden, I think. Godless, on Netflix, portrays a protagonist shaped by the Mountain Meadows Massacre, harboring a deep-seated hatred for religion.

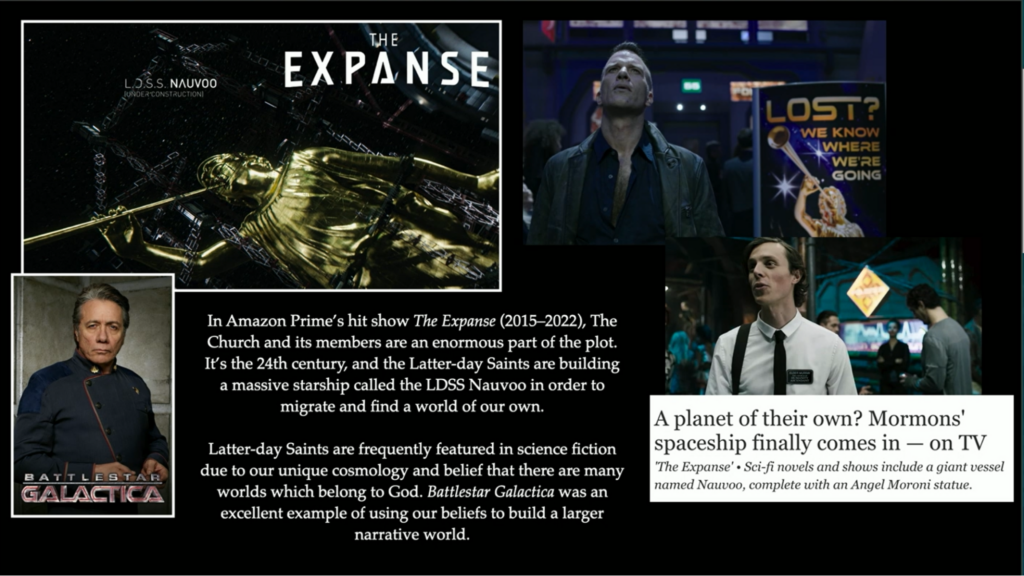

These examples aren’t necessarily favorable or unfavorable; they are just examples.

The Expanse is one of the most popular Sci-Fi shows on Amazon Prime, the LDS Nauvoo is a starship intended to transport Latter-day Saints to a new planet, emphasizing their desire for autonomy. I believe the starship gets taken away from them, but they are just depicted as this powerful group that is just trying to do their own thing. And of course, Battlestar Galactica, penned originally by a member, has lots of lore and cosmology from our own background and ideas about the planets and their rotation and things like that, as well as a quorum of the twelve, and all these references.

So, Westerns, Sci-fi increasingly feature one-off depictions of Latter-day Saint characters. Although these shows might inaccurately represent certain aspects, the characters themselves play central roles.

For instance, in New Amsterdam, a gay missionary grapples with his faith, and whether he is going to stay and finish his mission or whether he is going to depart from it.

Quantico, a character poses as a good guy while being a villain, and the show assumes you will think he’s a good guy because he is a member of the Church.

In Room 104, missionaries stay in a motel, which seems unlikely, and wrestle with their ideas and their faith.

Fargo, a very, very good and well made TV show. In its most recent season, 2020, it features Detective Deffy, who comes into Missouri from Salt Lake City in the 1950s. He never swears, won’t smoke or drink, and is constantly referring to the Nephites, Lamanites, and the 10 lost tribes of Israel. He’s even reminded that there is still an extermination order against him.

Recent Examples

Moving to recent examples. I gave you some thematic stuff. Again, in 2020, Messiah on Netflix, depicts the President of the United States, President Young, dealing with a Messianic character claiming to be the Messiah. And this president has to wrestle with that. It even cites, “the one mighty and strong,” from the Doctrine and Covenants, which I found kind of surprising.

In Tokyo Vice, which is like a journalistic thriller show, one of the characters is a woman who was a missionary and then ended up stealing from her mission, and staying in Japan and fleeing. A private detective is hired to go find her and bring her back to the United States. But she looks back very fondly on her mission and wishes that she had that more pure, simple life of being a missionary. I was surprised at how accurate they portrayed Latter-day Saint missionaries. This was in 2022; it just came out in April.

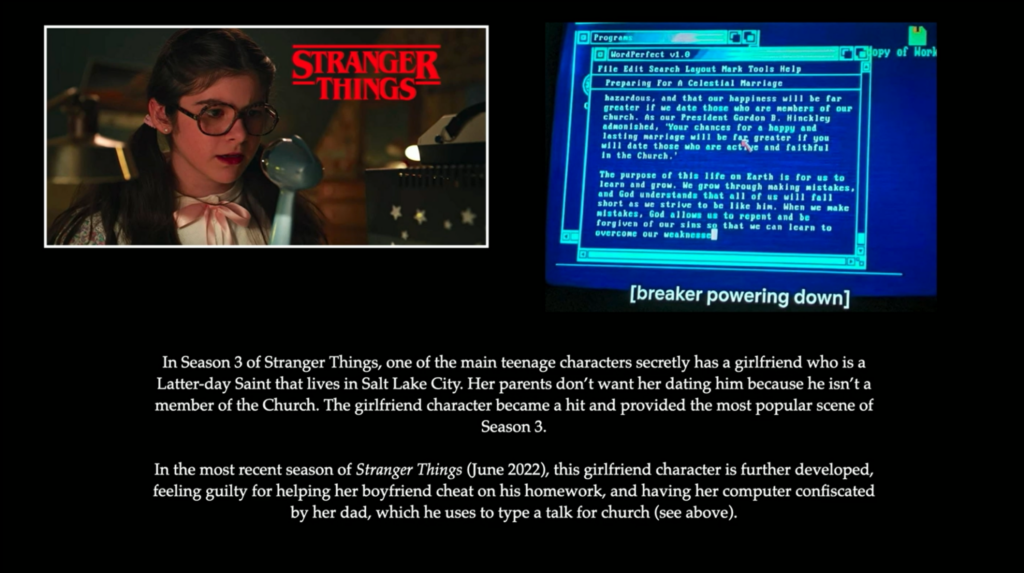

Stranger Things Season 3 has a main teenage character with a Latter-day Saint girlfriend from Salt Lake City. Her parents don’t want her dating him because he’s not a member of the Church. She goes on to have a big role in season 4 as well. In the slide, you can see where her dad is typing up a talk he’s going to give in Church on marriage. I read it and it’s not bad. Maybe I’ll take some notes

Recent Examples, Continued

At the Sundance Film Festival, there are films like The Touch of the Master’s Hand, which is kind of a short comedy, and The Mission, which was made by a non-member, a long documentary depicting what a mission might be like. The important takeaway is that the Church itself was a compelling enough subject matter to play at Sundance, whether or not the depiction was negative.

Coming out later this year is The Whale, featuring Brendan Fraser. He is a very, very overweight man, an atheist, who is befriended by a Latter-day Saint missionary, Elder Thomas, who is trying to help save him both physically and spiritually. Where Elder Thomas’ companion is, who knows, but at least Elder Thomas cares about poor Brenden Fraser. This film is part of what people are calling the Brendan Fraser Renaissance. He may be up for an academy award, because he’s back in the spotlight, and to be sure, The Whale and the depiction of a Latter-day Saint missionary will be part of it.

One that was recently announced, and had serious backlash, Sinner Versus Saints tells the story of the Manacled Mormon case. There was already a documentary made about this called Tabloid where a woman kidnapped a missionary and raped him. It’s being presented as a comedy, and if it’s not canceled, it’s set to go into production soon.

Polygamy has been a popular subject for a long time, and various shows, movies, and featurettes have incorporated it. In my opinion, until we have the courage to represent our own history with this, in a balanced and historically accurate light, we can’t complain about being dragged into that version by implication. Many of these shows touch on the Church, and while some do a better job of showing the separation of the two communities, like it or not there’s some link there, and we’ve never told our own version of this, at least on the screen.

Moving beyond traditional media, even video games delve into our faith. The Last of Us has a climactic point in front of the Salt Lake Temple. Fallout features characters who are unmistakably Latter-day Saints. It’s after a nuclear holocaust and they’re living and trying to rebuild their community and their society. Bioshock has a character likely based on Brigham Young. Far Cry 5 introduces a character who bears a resemblance to Joseph Smith.

Reclaiming and Telling Our Own Stories

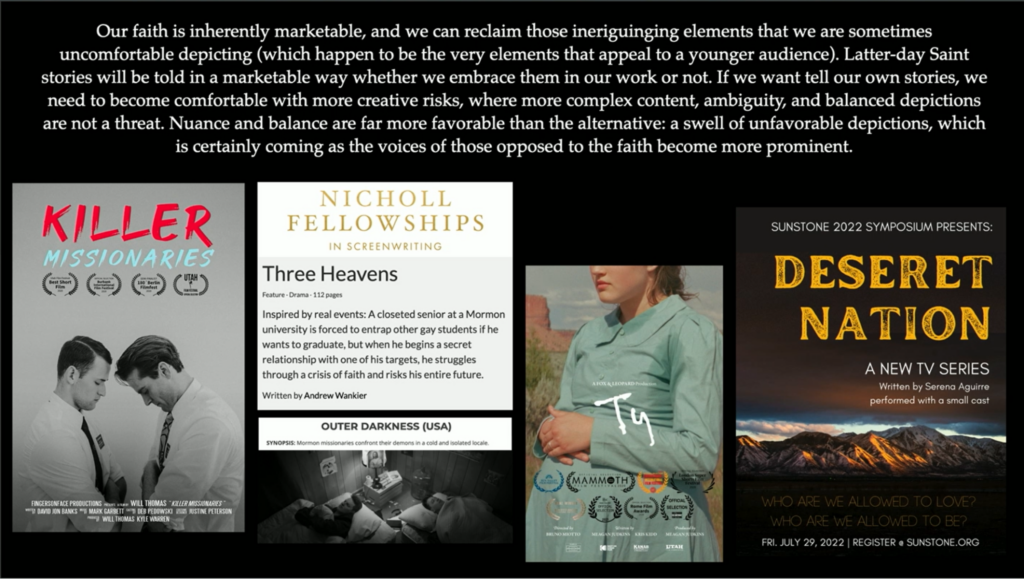

These examples are some of the more local ones that show that our faith is becoming more prominent in various productions, both big and small. As more young artists leave the faith and want to explore ex-member stories, perspectives that were once uncomfortable to depict are now gaining traction. Our faith is inherently marketable, and we can reclaim these intriguing elements that are sometimes uncomfortable depicting. These are usually the very elements that appeal to a younger audience, the hot button things. We don’t have to exploit them, but we can reclaim them and paint them in our own light.

Latter-day Saints’ stories need to be told in a marketable way, whether we embrace them in our work or not. If we want to tell our own stories, we must become comfortable with taking more creative risks, presenting more complex content and ambiguity, and balanced depictions are not a threat. Nuance and balance are far more favorable than the alternative of the swell of unfavorable depictions which is certainly coming, as the voices of those opposed to the faith become more prominent. I would suggest that it’s only beginning now.

Like I said, Latter-day Saints are sitting on a gold mine. Instead of telling each other our stories, which most of us already know, we should be telling the interesting and unique, and often complicated stories in our own voice, and in our own way, and take advantage of how popular and interesting our identity is to the rest of the world.

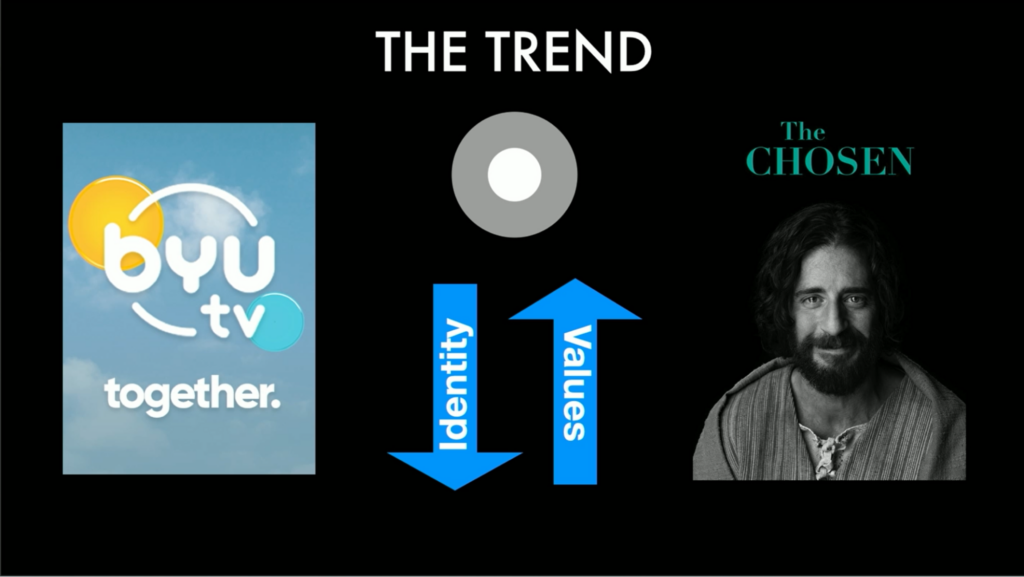

This is the current trend. I want to be clear; I don’t see this trend as entirely negative.

Identity and Values

In the Latter-day Saint film community, there seems to be a tendency to downplay our specific identity and to up-play our shared family values. The idea is that to appeal to the broader Christian audience, we should avoid being too Latter-day Saint, and focus on creating family-friendly Christian content.

The visual representation of this approach is depicted by two circles – one representing the Mormon or Latter-day Saint market and the other, a gray circle outside of it, symbolizing the potential reach beyond our specific identity. We can reach wider by doing that. BYUtv’s recent emphasis on shows and films aligns with this strategy, in their own words. That may be shifting, but this was the case when I put these slides together. The Chosen, a popular show among Christians, and that Latter-day Saints have been part of making, reflects this approach. Although maybe you’ve seen how hairy that can get to our other Christian brothers and sisters.

Widening Our Reach

My proposal is that the widest reach can be achieved by up-playing our identity and downplaying such specific values. I argue for exploring a diverse range of values and themes, as demonstrated by my short film, The Next Door, which is not particularly about trying to inspire or convert, but rather just tell a good, relatable human story, and yet so identifiably Latter-day Saint missionaries. These are examples of shows and movies that had a wide reach and are unabashedly about either Latter-day Saints or Latter-day Saint adjacent concepts.

I’d like to read a bit from this essay I have that goes into this, and hopefully I will be publishing this and these five pillars soon.

We should reject the growing tendency to downplay our unique Latter-day Saint identity in order to appeal to a wider, faith based audience. This practice is usually accompanied with doubling down on certain themes by using messages targeted to a generally Christian worldview.

“While an understandable attempt to reach more viewers who share our values, the reach of these films is still extremely limited.

We instead propose Latter-day Saint filmmakers lean further into the uniqueness of their identity, and broaden the values, themes and messages of their films to be more humanistic, dramatic, and widely accessible.”

To Be Clear

Now, I want to pause here and clarify: I am not suggesting at all that the specific beliefs, truths, and doctrines we know, cherish, and hold dear, need to serve broader values or mass appeal. I’m talking about stories and filmmaking, something very different from missionary work or sharing a sermon in church.

Though faith-based or family films are noble, they are not the only stories worth telling or watching. There are many other concepts, genres, and themes that regularly reach wider audiences, and placing them within a Latter-day Saint framework blends them with that elusive strange attractor. Why turn our backs on our most marketable features?

“Although these types of films will demand a leap into content, subjects and stories that other members of the Church may bristle at at times, it’s better than the alternative—allowing someone else to tell our rich stories without the same nuance, balance, or ethnographic accuracy that a participating member of our community could provide. Latter-day Saints can, and should, reclaim their own peculiar identity and narrative by taking advantage of Mormonism (that broad canvas) as a strange attractor, and reframing it in their own voice.”

I’m not saying this definitively, but this is a suggestion: perhaps the fellow faithful are the wrong audience. The wider you reach, the further your influence. If you want to look at this in some kind of missionary work way, just look at those messages that were sent to me. People feel more tender, more open, and more at ease with the idea of our church, which could, in turn, eventually lead to a missionary opportunity if that’s supposed to happen.

As I mentioned, the trends of the fifth wave, you can see this from my 2017 essay, which is available. Look at how large the amount of didactic films is compared to the comedic, and that small group of nuance. This has changed since 2017, but clearly, we have a proclivity for these, and that’s no problem.

I will readily admit, I love the devotional stuff. On Sundays, my wife and I will pop out old Seminary videos that can be found on YouTube or old Church movies, and we’ll cry and feel touched. It’s sweet and it’s true, and I care about it. I’m not saying that those are not worth something. But especially to younger audiences, those cannot compete with broader, wider, more interesting, well-produced entertainment.

Perhaps the most persistent problem in Latter-day Saint cinema is the tendency to lean into the didactic approach. Latter-day Saint texts and the didactic approach are above all else concerned with their mission and their message. These films tend to be heavy-handed, preachy, and moralizing, aimed to convince or confirm to the viewer that the restored gospel is true. The majority of films produced by Latter-day Saints, especially since the beginning of the fifth wave, have adopted this didactic approach to varying degrees.

The Art of Storytelling

Consider this: how often do you come across movies with noticeable political agendas that you may not necessarily agree with, and how does that make you feel about said movie? Do you want to watch more of said movie?

While it’s understandable for a proselytizing religious tradition to focus on its mission, this emphasis doesn’t always serve the art of storytelling. If a writer is too preoccupied with inspiring, teaching, uplifting, persuading, or representing, they are going about it in the wrong order. Those characteristics are not the measure of a good movie; they are the measure of good propaganda.

Although good stories certainly have clear themes and ideas, they are not mission oriented. A good story is good because it adheres to the rules of good storytelling. It was written for the sake of being a good story, rather than to achieve a desired change or measurable outcome in the audience’s overall viewpoint. The values or worldview of the filmmaker should not overshadow the values of the story and its characters.

Mission-based, Message-Driven

Both members and ex-members of the Church fall into the tendency of putting a propagandistic spin into their work, whether in defense of, or criticism towards, the faith. This criticism has been directed at films like Under the Banner of Heaven, which aim to convince viewers that the Latter-day Saint community is problematic, odd, and fundamentally violent. Both approaches qualify as mission-based, message-driven filmmaking.

We propose that the solution lies in prioritizing story over sermon, regardless of the message, and striving for total balance in a work, free from personal convictions or vendettas.

Portraying true ideological conflict can prove to be especially challenging for Latter-day Saint filmmakers, who have often been unwilling to depict the community, or even certain characters, in a less-than-positive light.

A telling example of this can be found from the set of The Work and the Glory II: An American Zion, where a producer asked if they had gone “too far” by portraying Joseph Smith Jr. as someone who gets angry. This could also be extended to one-dimensional portrayals of the opposing ideology, who say and represent an idea that the text is trying to discredit.

These flat, straw man characters can be seen all over cinema “for” and “against ” Latter-day Saints, exemplified by dirty Missourians and vampiric Mormons. Neither of those are completely true.

Measuring success in filmmaking does not mean the text is barred from making any claims; however, just as the first rule of persuasive writing is to qualify one’s argument, the themes of film will work better when they are honestly interrogated. The most poignant assertions are a balancing act, simultaneously extolling virtues and exposing weaknesses. Their criticisms are constructive and condemnations are counterbalanced by research, empathy, and patience.

Creating Balanced Themes

Here are some suggestions for creating balanced themes:

- Show both sides of the theme. Play devil’s advocate with your own themes and your own beliefs. Ultimately, if you have something you want to say by the end of the film, say it. But play devil’s advocate with it. We need more conflict and scrutiny, especially if the message is going to land.

- Explore strong internal conflicts within the primary character, the war within.

- Illustrate the theme in action—show it, don’t tell it.

Some Latter-day Saint artists may feel a commission to uplift, inspire, exhort, and preach the gospel through their artwork, it is not incumbent upon them to do so, that’s not their job. Missionaries, bishops, teachers, and apostles are called and set apart to provide instruction, artists are not. If they are, that’s that one artist’s calling.

However, if a Latter-day Saint artist insists on proclaiming the restored gospel through her work, she might align her understanding of it with definitions provided by early Church leaders, such as Brigham Young; in that it incorporates every system of true doctrine on the earth—whether it be ecclesiastical, moral, philosophical, or civil. It circumscribes the doctrines of the day, takes from the right and the left, and brings all truth together into one system.

Our gospel makes substantial claims, allowing exploration of broader themes through a gospel lens. These thoughts come from a place of faith and love. While they may seem unique, observing my generation, I find it important to take larger steps.

I mean, context over content here. The portrayal’s context becomes a more significant measure than scrutinizing the content itself. For instance, when assessing whether a film is family friendly or not, and how family friendly. Obviously, there are things that we need to avoid as Latter-day Saints; things that we covenant to be careful about, including our consumption of media.

But if we’re so careful and so picky about whether the film is family-friendly, or that’s the measure of how good it is, then that will diminish the quality and its outreach. Of far more import is the purpose these elements are being used for, and to what degree.

Imagine a film as a house; focusing solely on the type of lumber used without considering the architecture diminishes its quality. This does not mean mature content must be present in a film to make it worthwhile, nor do we sanction the gratuitous use of sais elements simply for the sake of it being lewd, vulgar, or profane. It simply means that the absence of adult content should not be an identifier for the new wave. Identifying a work by what is absent, rather than what is present, is a poor measure of quality.

Brigham Young talks about our duty to study evil and that there’s a difference between studying it or portraying it, and enacting it, or doing it in your own life. Again, this can be a slippery slope. You don’t want to go too far, but there is room.

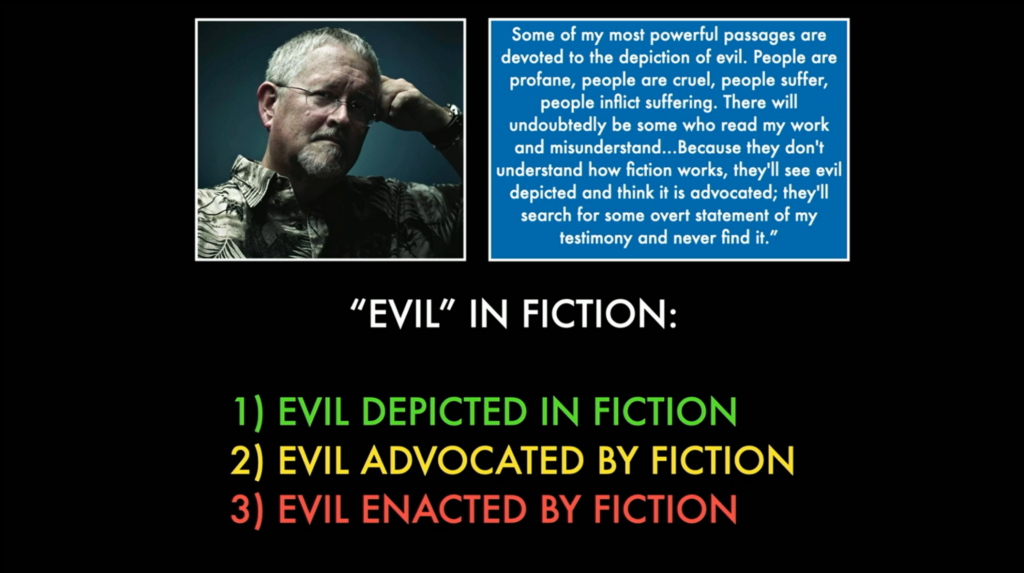

Orson Scott Card talks about evil in fiction, and how many people who consume fiction don’t completely know the difference between evil depicted in fiction, evil advocated by fiction, and evil enacted by fiction. An easy example of evil enacted by fiction would be pornographic novels or films. Pornography is evil, the thing is evil. Evil advocated by fiction would be a film or a movie saying that evil is okay. Where that is ultimately the theme. Evil depicted in fiction shows you that those things are present, but is not advocating for them in its overall message.

In the film program at BYU, we learned how to discern between depicting and advocating evil. You want to depict it without advocating it. At BYU’s Film School, the movies available on our canopy account, and shown in classes, are probably broader and more mature, or adult, than the typical taste of a Latter-day Saint. Since Latter-day Saints are not the primary audience, creating content that stretches beyond their preferences requires an understanding of how to depict, without advocating for evil.

Pillar IV – Excellence and Expertise

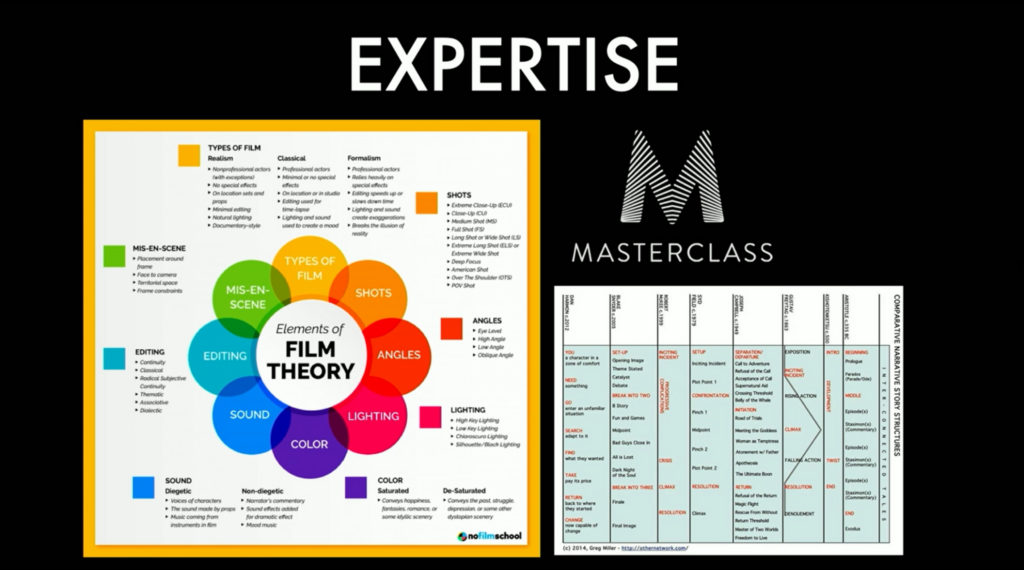

Moving on to the fourth pillar, Excellence and Expertise. One of the problems we run into is sometimes the intent is good and the story is well-written, but lacking the execution does not have the budget or expertise, or director’s vision behind it that ultimately makes it something that is marketable to a general audience, or that one could sell to a distributor.

For expertise, what I advocate is before venturing into making Latter-day Saint films, or telling these stories, the writers, producers, directors, art designers, cinematographers need to understand and learn things like film theory, go to school or take master classes, and learn your craft. If you’re not building your stories around proven structures and styles, then it’s likely to fail, No matter how well intentioned it needs to be good.

Filmmakers need to know the business of film, starting with local communities like Excel Entertainment, is essential. They should aspire to graduate to larger platforms and studios such as Netflix or Warner Brothers or even independent ones. Filmmakers need to know how to pitch materials and navigate different film rights.

Community is very important; rather than competing, filmmakers should support each other, creating an environment that discourages the release of subpar content. Help create a community where you can critique and improve one another’s work.

Some great examples of this are the Movie Brats from the 1970s. Most of you have probably heard of the Inklings, where Tolkien and C.S. Lewis collaborated with some others as well. The Lost Generation and some of these have existed within our own faith and belief movement. And the Archive, which is a current art community that makes interesting and new, unique Latter-day Saint art.

This might be the most complicated; who should be telling Latter-day Saints stories? This one is complicated, and might be where we, as active members of the Church, get the most flack and the most push back for being uncomfortable with our stories being told by those who have left the faith. I think there’s some fairness in that. To be part of something and then to step away from it, the longer you are away from it, the more different your perspectives and your represented reality becomes.

There are some things I’d like to share here from my essay.

The final pillar of the Saints new wave is perhaps the most difficult to define or quantify. It stems from the question of qualification: who is qualified to tell Latter-day Saints stories? Is it an active member of the Church? Is it a disaffected member who retains his membership? Is it any person who has had previous involvement with the Church? Is it someone from an adjacent breakoff sect? Is it anyone who has ever even known a Latter-day Saint?

“There’s a broad spectrum of belief within the Church, and an even larger one throughout the Latter-day Saint movement as a whole. Nevertheless, as participants in a niche and misunderstood culture, and much like any other minority faith, the qualifications of who should be telling Latter-day Saint stories are worth consideration. These qualifications are especially needed because depictions of Latter-day Saints have historically been so inaccurate, sensationalist, and exoticizing.”

Artist Intent

Here’s my largest proposal for this. Perhaps far less important than whether an artist is active or less active, or a non-member, or an ex-member, is the intent of the artist. A writer or director’s artistic intent colors every aspect of the film. In this spirit, a better way to consider whether a film should be part of the new wave is for the author of the piece to scrutinize his own intent. The point of the new wave is to examine, embrace, and incorporate Mormonism into our work.

In doing so, here are some rhetorical questions a filmmaker might consider:

- Is your position one of nuance, balance, fairness, and empathy?

- Would a Latter-day Saint recognize himself, or herself in your work?

- Are you looking to engage with the tradition, community, and institution, or to deconstruct it?

- Does your Latter-day Saint heritage have a meaningful and current impact on your life?

- Does your story come from a place of sincerity, grace, familiarity, and claim on the whole of the Latter-day Saint identity, including its connection to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints?

- If your relationship with the Church is strained, do you at least claim it as a constructive part of your identity, or recognize areas where it is a force for good?

- Do you purport some level of personal investment in, or ownership of the faith?

It’s hard to examine or judge exactly where someone is in their journey, but as artists and Latter-day Saint filmmakers ask themselves those questions, they’ll be better equipped to decide whether or not they really want to be part of something like this. And if the answers to those questions are any indicator, they may not want to be part of this as Latter-day Saint artists.

Diversifying

Beyond questions of belief, there are alternative avenues to explore the identity of who should be telling Latter-day Saint stories. Black Pioneer excels in this aspect by examining the broader worldwide network of Latter-day Saints, delving into diverse stories across various cultures, communities, and regions we’ve never tapped into. Those Latter-day Saint experiences are just as interesting, marketable, real, powerful, and artistic as the pioneer story is.

There are an increasing number of productions that effectively utilize cultural authority, code switching, and intersectional identities to their narrative advantage. We believe that adding Mormonism into this mix will only enhance dramatic possibilities and will increase the unique qualifications of the filmmaker.

A marker of the new wave should be its exploration of Latter-day Saint stories from every nation, kindred, tongue, and people. And we look to highlight the voices of diverse writers and directors who are best suited to share these lived experiences. Just as we are best qualified to share our own story.

A Call to Action

These pillars are designed as both a call to action and a guide for young filmmakers to return to. They build upon the five previous waves of Latter-day Saint cinema, in order to intentionally ignite a Saints new wave.

Given the increasing interest toward Mormonism in Hollywood, a sixth wave will inevitably occur, with or without our intentionality. Latter-day Saint stories will be told. It is simply up to us to decide whether we will be the ones to tell them as well. Thank you.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you very much for that. As you were speaking, I was thinking about some of the shows that we’ve watched, that my wife watches. We have Hallmark’s “When Calls the Heart” and “Blue Bloods,” where Protestantism and Catholicism are overtly and unapologetically portrayed. And yet, with Latter-day Saint cinema, we tend to either overly emphasize the point or depict characters as peculiar “Mormons.” Why do you think we are so uncomfortable with portraying the Latter-day Saint faith in cinema?

Barrett Burgin:

That’s a good question. First of all, I think sometimes it’s still our focus that there even needs to be a point, rather than merely showing Latter-day Saints in film. Unlike Catholicism and Judaism, which boast a rich spectrum of cinematic depictions, including works by Catholics and Jews who are not trying to promote any didactic agenda, certainly not clear cut, a lot of Latter-day Saints go back to “Fiddle on the Roof,” but even Fiddler on the Roof is about challenging convention throughout the thing, while still staying true to what makes somebody Jewish. I think we are uncomfortable with depictions sometimes, and branching out because we, as Latter-day Saints are a persecuted people, and we’re also an idealistic people. We strive for Platonic art versus Aristotelian art. Platonic art is all about the ideal. Aristotelian art is all about the reality, depicting what is real. Active members of the Church try to strive for the ideal in their lives. We bristle at depictions that are not striving for the ideal. And so sometimes what happens is we conflate unfair depictions with unfavorable depictions. Those aren’t necessarily the same thing. And I think unfavorable depictions of a character not living up to what they should be doing are okay as long as it’s accurate and real.

What we really bristle at, and are sensitive about are the unfair depictions. I think as we become more comfortable letting our guard down, knowing we don’t have to show our perfect side all the time in telling our story, and realizing that sometimes an unfavorable depiction actually humanizes a subject and endears someone to them because it’s like, “well, I’m not perfect either,” and then seeing them go through a very human journey, we can better differentiate between what is unfavorable and what is truly unfair.

To add to that, I think we’re better at forgiving and being fine with unfavorable depictions that we would never say are anti-such and such. You would never call Fiddler on the Roof anti-Jewish, but there are plenty of things that poke fun at themselves, for a wide audience to see, but they’re fair.

Scott Gordon:

I can see the headline now: “LDS Filmmaker says Not All Latter-day Saints are Perfect.” Gosh, I’m shocked. Here’s a question. Do you consider Napoleon Dynamite an LDS film?

Barrett Burgin:

Yeah, I would. Certainly there have been more discussions about Mormon or Latter-Day Saint cinema outside of my context. Plenty of people consider it yes, no. I think some of the attributes in it are undeniably pulling from his Latter-Day Saint rural Idaho experience. When I think of trying to create a new wave movement, I find it productive to push for something that is very identifiable and explicitly Latter-Day Saint. So it’s made by and about, but not for, Latter-day Saints, but rather for a general audience.

Jared Hess, the creator of Napoleon Dynamite, came to a BYU writers’ conference and some of the BYU writers asked if he got a lot of pushback in Hollywood for his “Mormonness.” “Not at all,” was his response. “People are fascinated by it.”

Sometimes in an insular kind of community bubble, the pushback becomes more aggressive, but in reality, outside of the “Book of Mormon Belt” a lot of people just don’t know much about Latter-day Saints and are curious. And so you can tap into that.

Scott Gordon:

I was thinking, especially for those involved in apologetics, criticism is often seen, but it comes from a small minority. Most people are simply curious and have no strong feelings either way.

Barrett Burgin:

It’s funny you say that because I want to be clear; I appreciate and admire Latter-day Saint apologetics. It’s not a bad word; it’s logical and reasonable, offering counterarguments. However, films should not be apologetic. It’s a disservice. The reason I wanted to present this at FAIR is because the most apologetic thing you can do in making a Latter-day Saint film is NOT make it an apologetic film. Make a balanced film, make a nuanced film. It will be more vulnerable and accessible. Leave apologetics to debates, papers, and social media.

Scott Gordon:

This goes along with the new missionary push, doing things in a natural, normal way. Showing how Latter-day Saints naturally live, and what our lives are like, that might be helpful to people. We don’t sacrifice young people in the temple. Yes, we’re weird, but we’re not that weird.

Barrett Burgin:

We’re weird enough to market it. Weird’s not bad, it’s good.

Scott Gordon:

There are several questions here. One person suggested making the Hole in the Rock Expedition, a film. One observation is that classic films with religious elements, as discussed in a BYU theater class, offer opportunities for discussion based on character interactions and experiences. Some of our existing films are heavy-handed in pushing a dogma, such as ‘Under the Banner of Heaven,’ which portrayed Mormons negatively.

Barrett Burgin:

The director even clarified his point. This is the point I want to make.

Scott Gordon:

Right. And he could have made a wonderful film about a very tragic event. And instead he used it to just push his theme. And I’m sure people feel the same way about some of our films.

Barrett Burgin:

I actually think his themes would have been more effective if he backed off a little. When I watched all of ‘Under the Banner of Heaven’ and a couple of episodes in, I was a little bit like, ‘Oh, okay. I guess it’s not going to do the damage it thinks because it’s clobbering me over the head with it.’

I think also that, as Latter-day Saints, we should not be afraid of a lack of clarity or ambiguity. It’s so interesting because, you know, even our Temple experience is benefited from not having everything very clear. You have to wrestle with it, engage with it. Sometimes I find the Lord is in the paradox. It’s in the tension and wrestling before God. Another term or another definition of Israel: let God prevail, but also the wrestle. You can’t let Him prevail unless there’s a wrestle, and then ultimately, let God prevail. That would be my thought on it.

You know, I think it’s so hard for Latter-day Saints. This is why they’re not my target audience. So hard for Latter-day Saints to watch a film about themselves and be able to disengage and let it be unclear at the end, or let it be kind of ambiguous or not strongly stating, ‘This is where we stand.’ Yet, that’s such a component of our Doctrine, a valuable, beautiful thing that we embrace in other areas.

Scott Gordon:

Yet, we find when we watch other shows, that’s not what they do. We learn how characters grow and develop and learn new things without being clobbered over the head. So, we don’t need that.

Barrett Burgin:

Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

Scott Gordon:

So here’s one, Without giving away any secrets, if you had an unlimited budget and had access to all the actors that you wanted, and somebody said, like, ‘Hey, we recognize you as a filmmaker. We’re going to give you everything you want.’ What story would you like to do?

Barrett Burgin:

Unlimited budget and a Latter-day Saint-themed idea. I suppose, I think a mini-series of ‘Rough Stone Rolling,’ a mini-series of Joseph Smith that is just as complicated and beautiful and rich and powerful. You know, and some people wouldn’t like it, and some people would love it, and the truth is it can’t be too far one way or the other because miracles happened, and the guy was enigmatic. You know, and that, to me, is a prophet. I mean, that’s powerful stuff.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you very much. We really appreciate you coming to us.

Barrett Burgin:

You’re welcome. Thank you for having me, everyone. Appreciate it.

coming soon…

Why should Latter-day Saint filmmakers lean into their unique identity?

Barrett argues that authenticity and embracing the distinctiveness of Latter-day Saint culture make stories more compelling and marketable.

How can filmmakers balance faithfulness to gospel values with artistic freedom?

By prioritizing context over content and focusing on meaningful storytelling, filmmakers can create works that inspire while remaining true to their beliefs.

Exploring the potential of nuanced, balanced portrayals of Latter-day Saints in cinema.

Emphasizing the importance of reclaiming the narrative by telling authentic stories.

Advocating for the integration of faith, artistry, and universal themes.

Share this article