Presentation by LaJean Purcell Carruth

Transcript

Introduction

[Scott Gordon:] LaJean Purcell Carruth is a professional transcriber of 19th and early 20th century documents written in Pitman and Taylor shorthand, and in the Deseret Alphabet at the Church History Library. I don’t know why we don’t teach Deseret Alphabet in school anymore. I just can’t figure that out! She’s transcribed Mormon and Quaker sermons, minutes, legislative proceedings and court proceedings, journals, letters and other items. And there’s a lot more you can read online in her bio; but with that short introduction, I’m going to turn the time over to LaJean Carruth.

[LaJean Carruth:]

There was a man named George Watt

Who could improve Brigham Young, so he thought.

So he took out words here,

And he added words there,

And his accuracy was not what it ought!

– LaJean Purcell Carruth

Introducing George D. Watt

When George D. Watt was baptized by Heber C. Kimball on July 30, 1837, in the river Ribble, he was the first convert baptized in England into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. He won a foot race for that privilege.

That same year, Isaac Pitman published his new shorthand method, Pitman shorthand. It was the first English shorthand that permitted a skilled reporter to report what a speaker said verbatim — at least until the speaker became excited or angry and sped up. These two events converged. The shorthand records written by George D. Watt in Pitman shorthand include some of the most significant records of 19th century church history.

Watt reported sermons, meetings, private discussions, court records, dedicatory prayers, other prayers (I love Brigham Young’s prayers. When Brigham Young prayed, the lion of the Lord became a pleading, humble servant. I love his prayers), legislative reports of the Utah territorial legislature, his 1851 journal from Liverpool to Chimney Rock, and rough drafts for letters, including some to prospective plural brides, all in Pitman shorthand.

Shorthand: Pitman, Taylor and Deseret Alphabet

I am a professional transcriber of manuscripts written in Pitman shorthand, Taylor shorthand and in the Deseret alphabet at the Church History Library. I learned the Deseret alphabet at age 11. And then I decided, with all the wisdom of an 11-year-old, that I was going to be a professional transcriber of Deseret alphabet manuscripts when I grew up. This interest led years later to my learning old Pitman shorthand.

I have spent many, many years transcribing the shorthand of George D. Watt and others. And through this work, I have learned how his long-hand transcripts of his own shorthand, and the published versions of those transcripts differ, often significantly, from his original shorthand record; the transcripts and published versions of other shorthand writers also differ from their shorthand records.

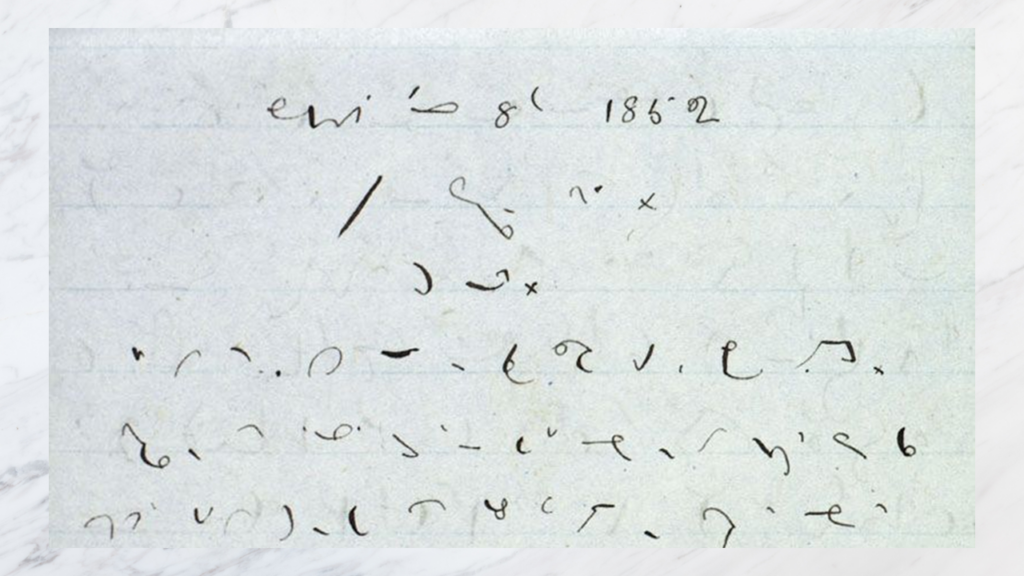

Shorthand is a quick way of writing. You’ll see an example here. This is what I read. It took me 30 years, from when I first learned shorthand, to be able to read George D. Watt’s shorthand: 30 years and thousands of hours of work. Shorthand is a quick way of writing using curved and straight lines, circles, dots, dashes, and other symbols to record the sounds of words. These symbols often have multiple meanings. Shorthand is cryptic, often ambiguous, and a challenge to read. Sometimes it’s like putting together a jigsaw puzzle, especially when read by a person who didn’t write it. When a person writes shorthand, they have a memory of what was said, and they also know how they write shorthand. I wasn’t there when Brigham Young and others spoke.

This shorthand reads: “Sunday morning, August 8, 1852. Judge Phelps prayed, Governor Young,” then three lines of his sermon, “I will read a revelation given to Joseph Smith Jr. and Sidney Rigdon. Previous to my commencing upon the subject that I expect to lay before the people this morning. I will say to them my understanding with regard to preaching the gospel.”

George D. Watt’s Shorthand

Unfortunately, George Watt left no record of how or when he learned shorthand. He apparently learned it before he arrived in Nauvoo, because he advertised in a Nauvoo paper in 1842 for shorthand classes. The first extant shorthand we have in his hand is from April 1845. Joseph Smith did not use shorthand writers. There are a few words written by scribes in his journal, but there’s no shorthand record of any sermon given by Joseph Smith, unfortunately.

George Watt recorded a few sermons in Nauvoo in 1845. He recorded the trial of the murderers of Joseph Smith in shorthand. Then he returned to England and Scotland on a mission. He arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in September 1851. He kept a journal about that journey, which was completely unknown until I found it 150 years later and transcribed it. From this journal, and from his letters, we know that he was an excellent writer. Hence my line: “Could improve Brigham Young, so he thought.”

Origins of the Journal of Discourses

He began recording various talks and sermons in shorthand almost immediately upon his arrival in Salt Lake Valley. But a problem arose: Willard Richards was editor of the Deseret News. He wanted Watt to write shorthand of sermons, transcribe them, and give him give them to him for publication in the News, but he didn’t want to pay him. And Watt had a large family, he needed some income.

They had a fairly acrimonious exchange of letters; we have George’s drafts in shorthand. And then finally, they reached an agreement. George Watt would transcribe his shorthand and give it to Willard Richards for publication in the Deseret News, but then he would send it to England and publish it privately as the Journal of Discourses, for income to support his family.

So, the Journal of Discourses was a private venture with the written support of the First Presidency.[1] The intent was to support George Watt and his family. Later, the church took ownership of the Journal of Discourses and paid Watt a salary, but it was never considered an official church publication. And it is never considered a statement of church doctrine.[2]

On May 15, 1868, Watt asked Brigham Young for a raise. Young became angry; the two men’s tempers flared. Young denounced Watt that afternoon in the School of the Prophets. Watt took it all down in shorthand and left. That’s the last shorthand we have any knowledge of written by George Watt. (I can’t help but hope that there are more journals out there — if anybody has any knowledge of any, let me know.)

What Was Published Differs from What the Speakers Said

As Watt transcribed his shorthand and prepared for publication, he did what every other shorthand writer that I’ve ever encountered did: he altered it. He added words and passages that were not in the shorthand, including many scriptures. He omitted some passages and words that were in the shorthand. Sometimes he transcribed them and crossed them out. But often he never transcribed them. He changed words, changed questions to statements, changed pronouns and nouns, and made other changes. Watts longhand transcripts show that he made most of these changes while he was transcribing.

I’m often asked if these are later editorial editions, but we have his transcript and right in the line of his writing, right when he was transcribing the first time, it’s right there — that’s where most of the changes were made.

This is simply what shorthand reporters of the time did. And it’s important to understand this: their ideas of accuracy were very, very different from ours. Now, understanding is not excusing, and there’s no reason to excuse, but it is important to understand how different those ideas of accuracy were then than now. And George Watt, like all human beings, was a product of the time in which he lived.

We owe a tremendous debt to George Watt for his shorthand record, which is an invaluable resource in church history and for items he transcribed and published. I cannot overstate that. But while we neither condemn nor excuse Watt’s changes, it is vital that we understand that what was published differs, often significantly, from what the speakers actually said. That what we read in the Journal of Discourses and in the Deseret News (which is the same material) is too often the words of George Watt and other shorthand reporters, not the words of Brigham Young and other speakers.

If we are to understand the teachings, ideas, speaking and style, and personality of Brigham Young and others, it is vital to read what they really said. The original shorthand record is the closest we have, until sound recording came in the late 1890s. And even after that, shorthand records are often the closest we have to what really went on — what was said.

We Need to Judge on Correct Information

Understanding this can help us better evaluate what was published and judge our response to it. A few years ago, a neighbor’s son, who was a law student, told me he had some friends leaving the church over the wording in the Journal of Discourses. I gasped, “They can’t do that!” I stopped and said, “Well, they can do what they want.” I mean, I have total respect for others’ agency, but they’re leaving the church over the wording of George Watt, and others. We just need to judge on correct information.

Watt’s Changes to Brigham Young’s Words Were Significant

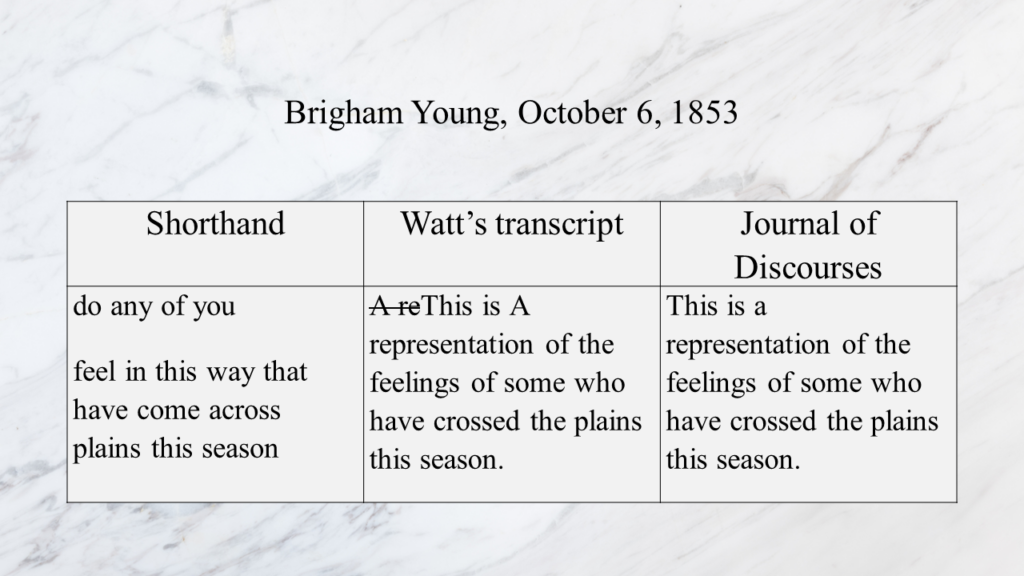

Watt’s changes to Brigham Young’s words were significant enough to change our perception of Brigham Young’s personality. For example, when Young said “heart,” Watt repeatedly changed it to “mind,” moving the statement from the realm of the spirit to the realm of the intellect. Young often addressed the congregation in questions, which Watt repeatedly changed to answers, which changed his style in speaking.

On October 6, 1853, Young spoke with those who lost heart crossing the plains. You’ll see on this next slide, he addressed a question to the congregation, which Watt changed to a statement; and Young’s question, inviting thought, became something of an accusation, a change in personality — from understanding to accusing. So, Brigham Young said, “Do any of you feel this way that have crossed the plains this season?” And Watt changed it to, “This is a representation of the feelings of some who have crossed the plains this season.”

The change of question to statement occurs repeatedly through Watt’s transcription of Young’s words. Changing his frequent questions to statements makes him sound more authoritarian, less understanding, than his original words — what he really said, and who he really was.

Some Specific Examples of Changes in the Text

I will now go through examples of several ways in which the text of the Journal of Discourses differs from the original shorthand record. Although these changes are pervasive throughout the Journal of Discourses, and the sermons in the Deseret News (which again is the same material), for today I have chosen to take all the rest of my quotes from one talk given by Brigham Young on December 23, 1866,[3] to show how many differences exist in a single sermon. And we’ll discuss why these changes matter in terms of our understanding what Brigham Young and others really said, and who he was: how changing the words changed his personality.

Some of the most pervasive differences between the original shorthand record and the Journal of Discourses are additions and omissions: text in the Journal of Discourses that is not in the shorthand record, but which was written and added (presumably by the transcriber), and text that is in the shorthand that was not included in the journal of discourses — omissions.

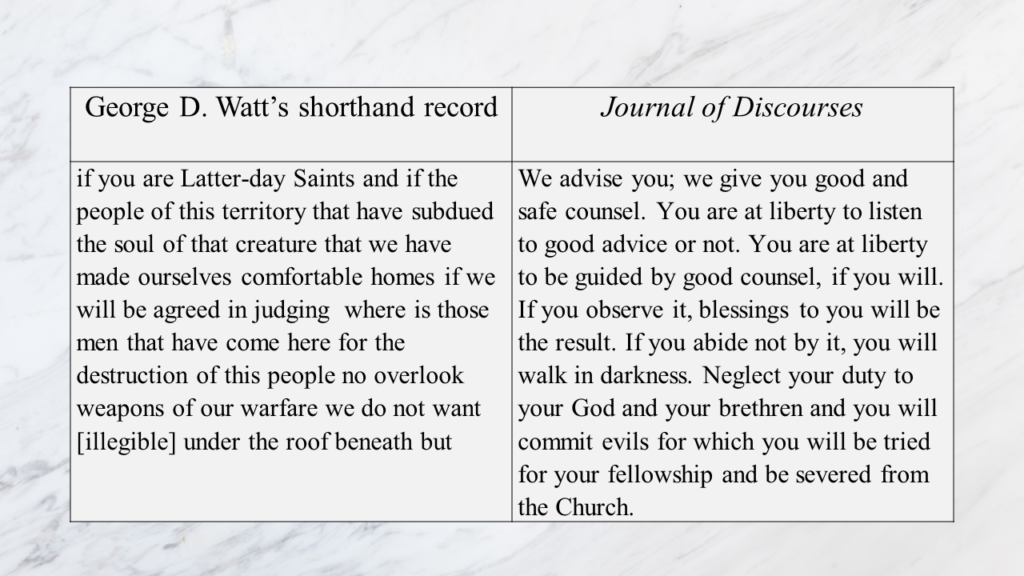

Additions

Watt added many words and phrases to the Journal of Discourses that are not in the shorthand record at all. Sometimes the content of a passage is completely unrelated to the shorthand, as here. In this talk, when I have them in parallel columns, the content just before this quote, the shorthand and published versions agree — maybe not perfectly, but they agree. And in the content just after this quote, they also agree. But you can see here that they are completely different.

As these slides move, I will read the shorthand. And you can follow along in the Journal of Discourses content in the slide. And on this slide, in my final preparations, I went back to the shorthand and was able to clean it up a little bit. So, what I read will differ slightly from what you have on the screen.

The shorthand of Brigham Young speaking reads: “If you are Latter Day Saints, and if the people of this territory that have subdued the soil to that degree that we have made ourselves comfortable homes, if we will be agreed in waging war with those men that have come here for the destruction of this people, no weapons of our warfare we do not want under the roof beneath but.”

Watt Added Teachings Brigham Never Taught

You can see in the Journal of Discourses column, there’s just no similar content. There’s no relation. In the next quote, slide five, Watt added teachings about God and Christ that are not mentioned in the shorthand at all, or in any other Brigham Young sermon I have read. Note also the shift in style from verbal style in the shorthand to grammatically more complex written style in the published text.

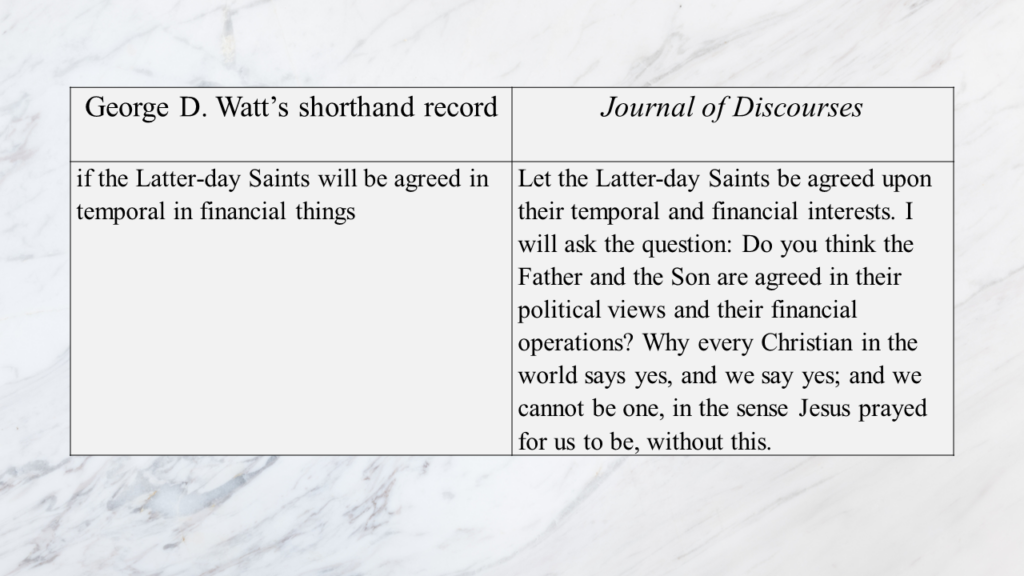

So, the shorthand record reads, “If the Latter-day Saints will be agreed in temporal in financial things.” That’s all he said. You can read what the Journal of Discourses says. Brigham Young didn’t say this. And it’s not fair to judge him on things he didn’t say, or anyone. Watt’s edition of this passage defines “being one” in a complex way that Brigham Young did not. Additions of words often change the meaning of the passage.

Changing Words Changes Meaning

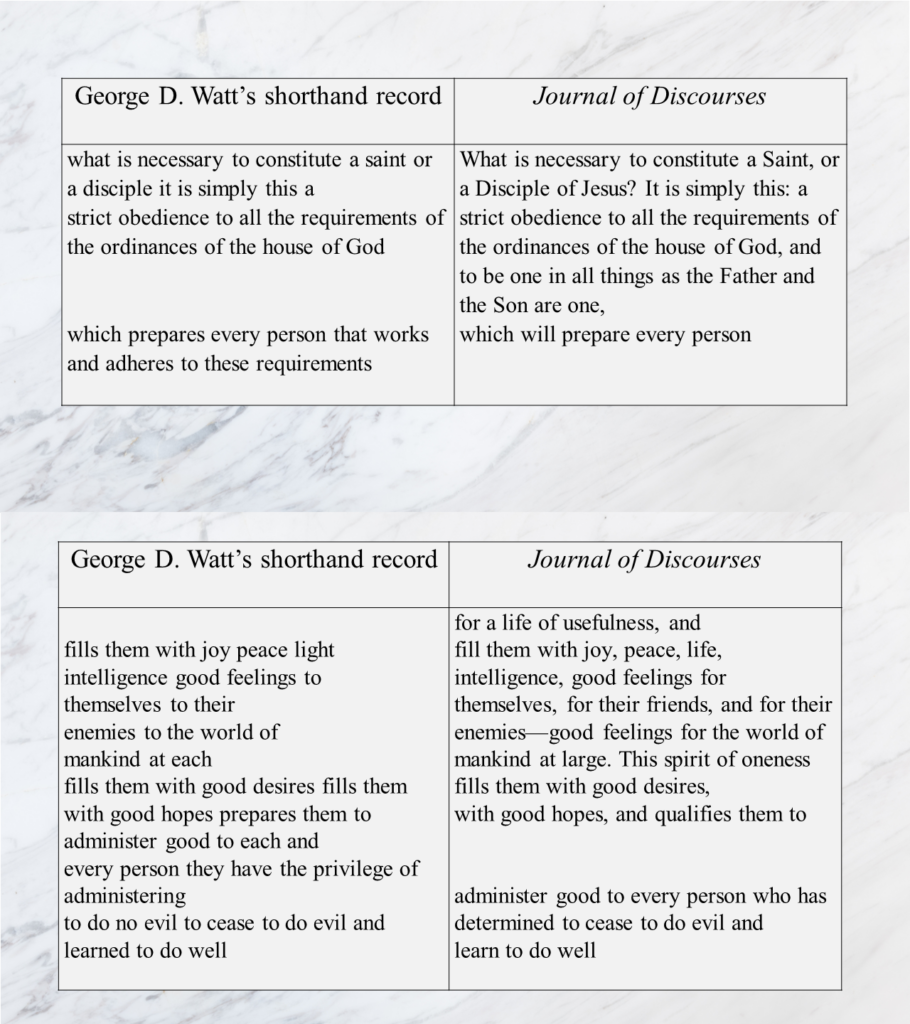

In this next quote, which has two slides, the repeated addition of ‘spirit of oneness’ changes the teaching about what constitutes a saint from obedience to being one: from something within the aspiration and effort of each individual to a group activity — a significant difference in meaning.

Again, I will read the shorthand: “What is necessary to constitute a saint or a disciple? It is simply this: a strict obedience to all the requirements of the ordinances of the house of God, which prepares every person that works and adheres to these requirements…[next slide] fills them with joy, peace, light intelligence, good feedings to themselves, to their enemies, to the world of mankind at large, fills them with good desires, fills them with good hopes, prepares them to administer to each and every person. They have the privilege of administering to, do no evil, but Cease to do evil, and learn to do well.”

Note the change at the end. The shorthand describes actions of the person administering, which the Journal of Discourses text changes to qualify those who should be administered to: “to administer good to every person who has determined to cease to do evil and learn to do well.” It sounds like everybody else isn’t worth administering to, but that’s not what he said. Brigham Young spoke of the privilege of the saints to do no evil, but to do good: the Journal of Discourses changed this to define those to whom the saint should administer good, which is a significant difference.

Additions – Why does it matter?

I have experienced a tremendous amount of personal slander in my life. I know what it is like to be condemned and punished for things I not only did not say or do, but did not even think about saying or doing, and would never say or do. This has made me fierce in seeking the truth and then judging on correct information, both as a person and as a professional historian.

When we judge Brigham Young and others on incorrect texts, on what they not only did not say, but would not say, we cannot judge them with equity and fairness. It is something like the fake news of our day. We need to take the same care in evaluating historical sources as we do anything else if we are to arrive at the truth.

Scriptures

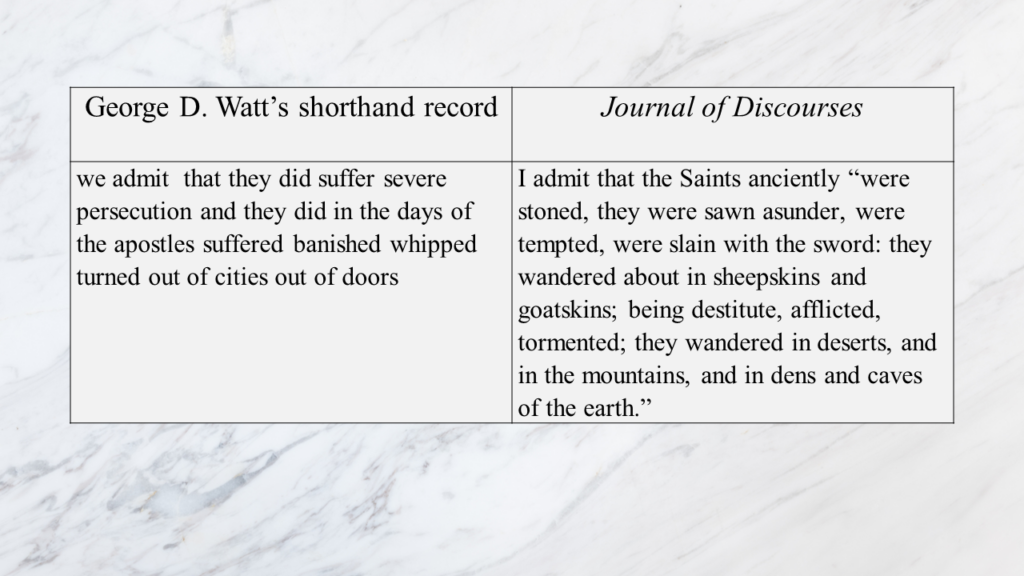

Some of the scriptures in the Journal of Discourses sound like they were just plopped in; well, they were. A significant portion of the scriptures in the journal discourses are editorial or transcriber additions. They have no content in the shorthand at all. Here are some examples from our sermon of December 23, 1866.

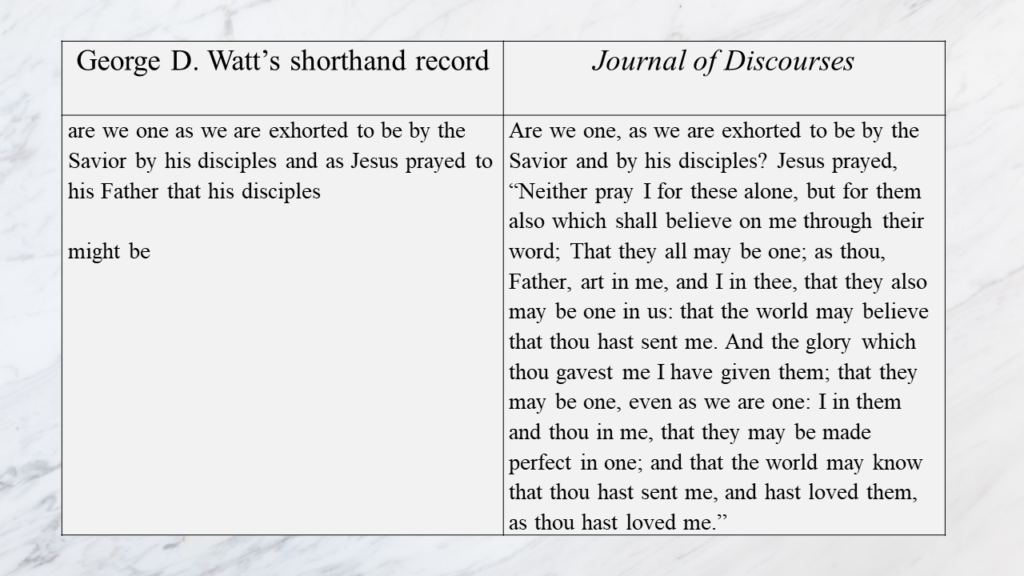

Brigham Young: “Are we one, as we are exhorted to be by the Savior by his disciples and as Jesus prayed to his father that his disciples might be?” And you can read what it says in the Journal of Discourses. And these are pervasive — these additions are pervasive through the Journal of Discourses. There is a difference between referring to something mentioned in the scriptures and quoting the scripture itself. Here, Brigham Young mentioned Christ’s prayer, but he did not quote it. The scripture is added.

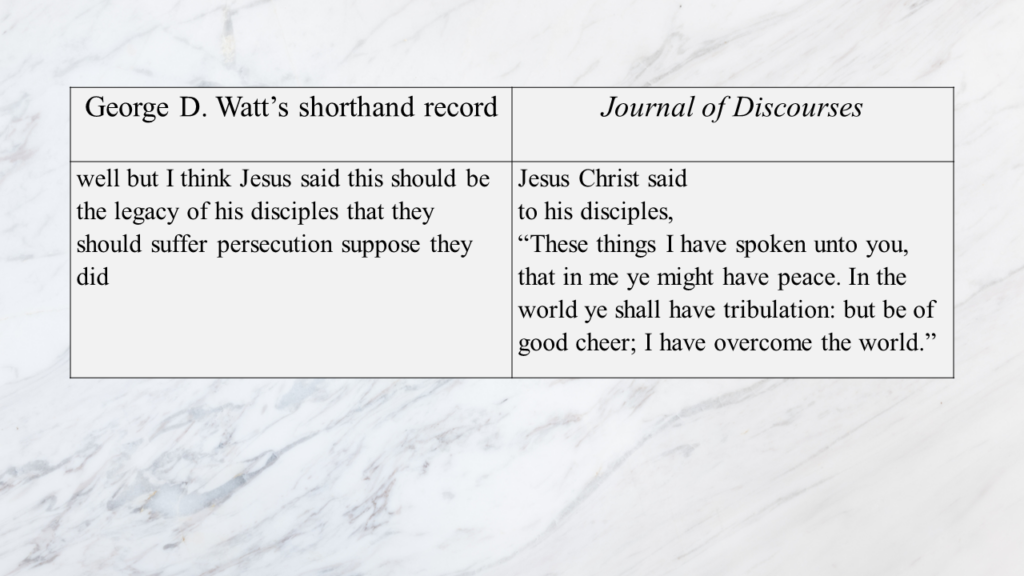

Another example: “Well, but I think,” and here he was referring to what other people said to him, “but I think Jesus said this should be the legacy of his disciples that they should suffer persecution, suppose they did.”

Again, there’s nothing in the shorthand record that suggests he quoted the scripture (and there are scriptures quoted, usually paraphrased, because memories aren’t perfect). There’s nothing in the shorthand record to suggest that he quoted the scripture or spoke of peace. And the same in the next example — Watt inserted the scripture.

“We admit that they did suffer severe persecution. And they did in the days of the apostles suffered, banished, wept, turned out of cities and out of doors.” Note, also, the change from the inclusive “we” in the shorthand to the “I” in the Journal of Discourses. Brigham Young was much, much, much more inclusive in his speaking, as he really spoke.

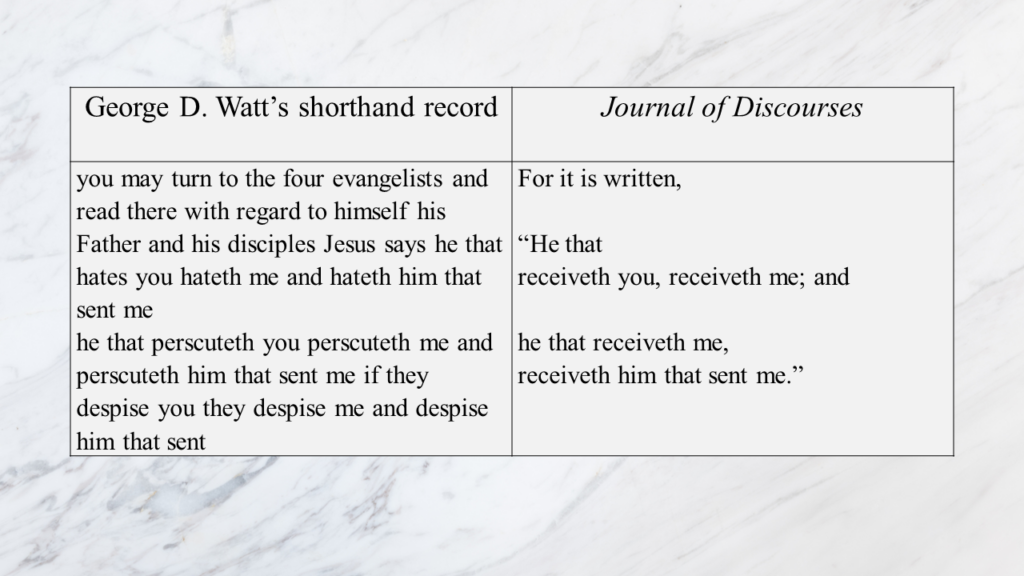

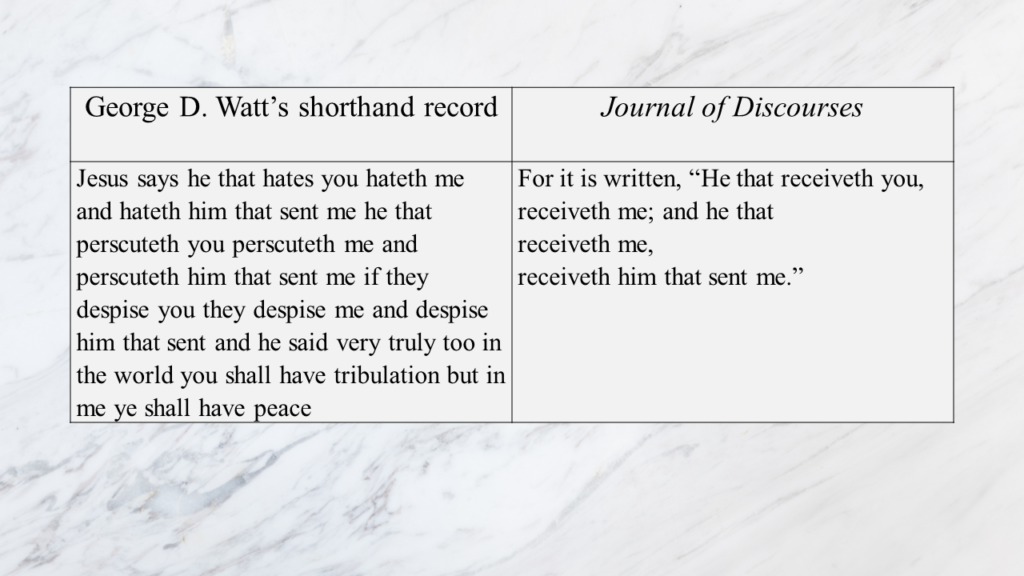

In the next quote, Watt inserted a scripture that is the opposite to what Brigham Young said. Brigham Young said that Jesus taught that those that hate his disciples hate him and his Father. Well, the Journal of Discourses reads that those who receive them receive him and his Father. And the Journal of Discourses omits the section on persecution.

“You may turn to the four Evangelists and read there with regard to himself, his Father and his disciples. Jesus says, He that hates you hateth me, and hateth him that sent me. He that persecuteth you persecuteth me, and persecuteth him that sent me. If they despise you, they despise me, and despise him that sent me.” You can see that has no content to the Scripture quoted, except “you and me and him that sent me.”

Scriptures – Why does it matter?

Anyone studying what scriptures were actually quoted by Brigham Young and other speakers needs to study the transcripts of the original shorthand, not the revised, edited, added-to published versions. Those who study the use of scriptures in the Journal of Discourses, the Deseret News, or the original longhand transcripts are too often studying scriptures added by the transcribers and the editors, not scriptures used by the actual speakers.

Omissions

Watt did not transcribe many words, phrases, even long sections of the shorthand record. Now some passages he apparently omitted because the shorthand became difficult. It is difficult. I remember when I discovered that time after time after time when I ran into trouble with the shorthand and referred to the Journal of Discourses for vocabulary, the section just wasn’t there. But other times he omitted material, and we have no idea why.

The following quote doesn’t have a slide, but it is part of a long section that Brigham Young spoke on December 23, 1866, about Moses. This was completely unknown until the shorthand was transcribed.

About our travels from Nauvoo to this place, suppose [that had] been the travels of children of Israel, and I had to bear what Moses had to bear.. . . I was thinking how free I was in my travels from such impertinences as Moses had to bear. Whenever the cloud started, it was “Strike your tents! The cloud is moving!” [They would ask:] “Moses, how long [have we] got to stay here?”

We stopped to Pisgah and Garden Grove, Winter Quarters etc., but we had not the cloud. We had to follow the providences of God which was dealt out to us. I was happy to think I was clear, free of this, steady. But they was rebellious full of fight. . . They would raise mischief and [make] no mistake about it just as wicked as could be. . . how rebellious they were! This is speaking for the encouragement of Latter-day Saints; if there is greedy Mormons and [biased?] Mormons and those that cannot see, they are not so bad as children of Israel were

This is fascinating material. It was completely omitted, it wasn’t transcribed. It was lost until I found it. And though Brigham Young is often referred to as the American Moses, I am convinced he would not like that title. He was far more Enoch. His goal was to build Zion. And he certainly would not have wanted to lead the people that Moses led.

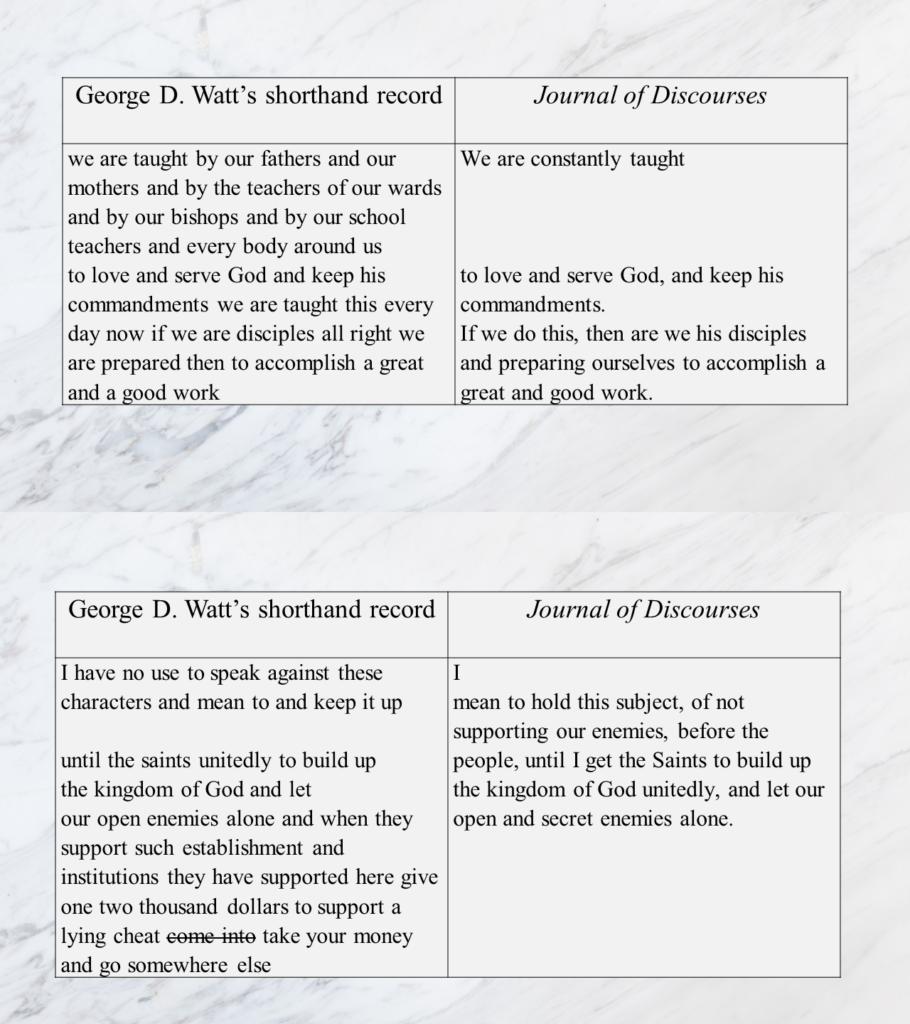

Note the omissions in the following section. “We are taught by our fathers and our mothers, and our teachers of our wards and our bishops and fire school teachers, and everybody around us to love and serve God and keep His commandments. We are taught this every day. Now, if we are disciples, all right, we are prepared to accomplish a great and a good work.”

Brigham Young struggled to get the saints to stop shopping with the merchants who would charge exorbitant prices and then haul precious wheat and very limited cash outside of the territory. But part of his teachings were omitted.

“I have no use but speak against these characters and mean to and keep it up until the saints unitedly to build up the kingdom of God and let our open enemies alone and when they support such establishment and institutions they have supported here give one $2,000 to support a lying cheat, take your money and go somewhere else.”

Note also the change from “until the saints” in the shorthand to “until I get the saints” in the Journal of Discourses. Changes like this portray Brigham Young as far more authoritarian than his real words.

Omissions – What does it matter?

When words phrases and entire passages were not transcribed, the reader of the transcript doesn’t know they were there. Removing words can and often does completely change the meaning of a passage and the impact of a text. Omitted content is lost until the original shorthand is transcribed, and if the original shorthand is extant; much of it isn’t.

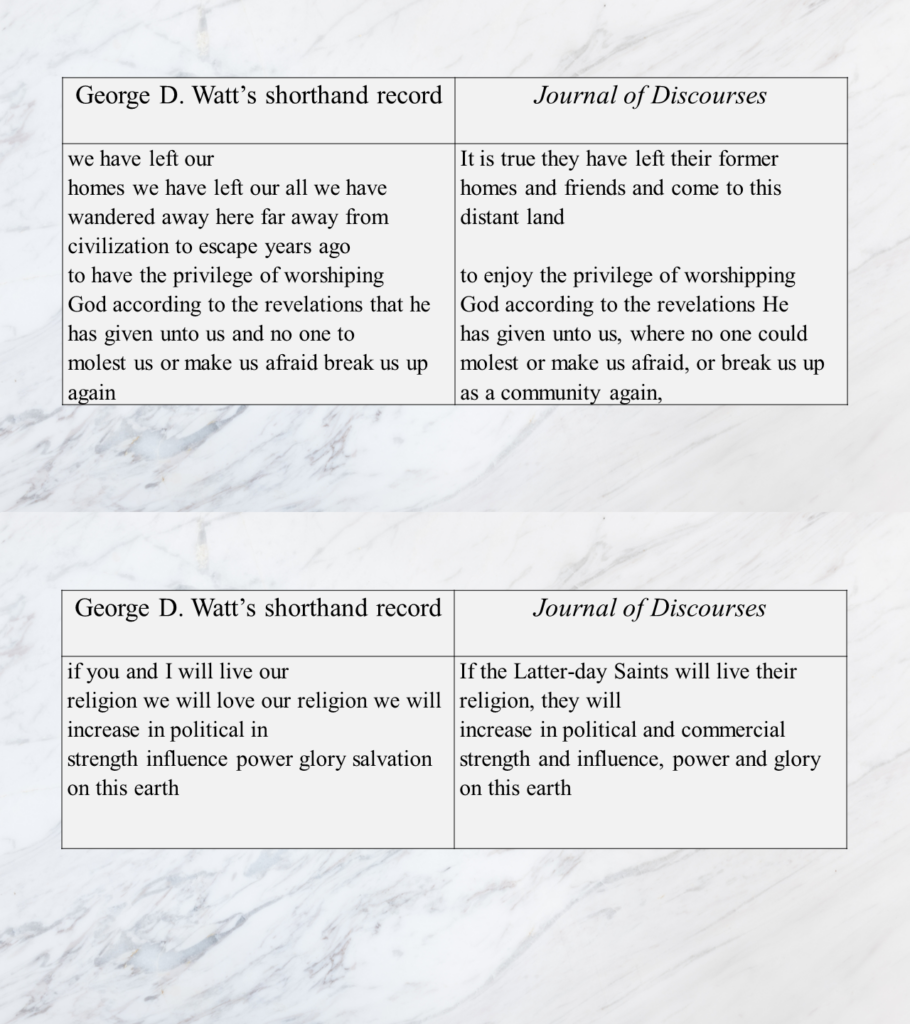

Change in Person

George Watt changed pronouns from first person to second person or third person and vice versa: he changed “I” to “you” or “they” or “he” and so on. This changed the meaning and intent of the passage. Note the change from the first person to third person in the first part of the published text.

“We have left our homes we have left our all we have wandered away here far away from civilization to escape years ago to have the privilege of worshipping God according to the revelations that he has given unto us and no one to molest us or make us afraid break us up again.” The shorthand is much more inclusive – “we” instead of “they.” Again, in the Journal of Discourses as “they” and then it goes back to “us.”

Another example: “If you and I will live our religion we will love our religion we will increase in political in strength influence power glory.” In the Journal of Discourses this is third person: “if the Latter-day Saints will live their religion.” Again, Brigham Young as he really spoke was far more inclusive, using “we” a lot more than he’s known through his published words.

Change in Person – Why Does it Matter?

Changes in person change what was really said and about whom, and often change the emotional content of the passage. Brigham Young was much more inclusive as he really spoke – another change in his personality. A lot of statements Brigham Young made about himself are lost, because the “I” was changed to another pronoun.

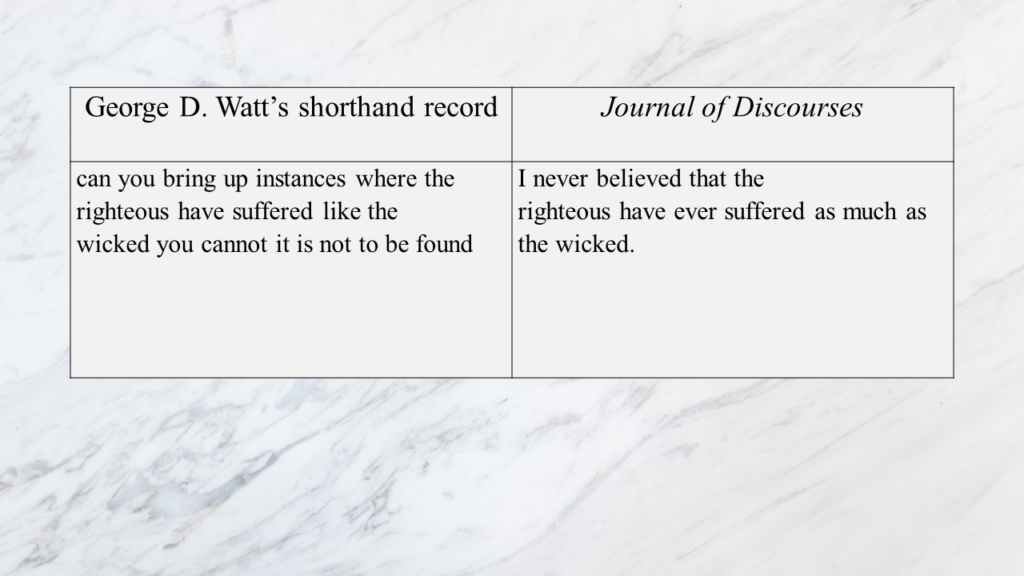

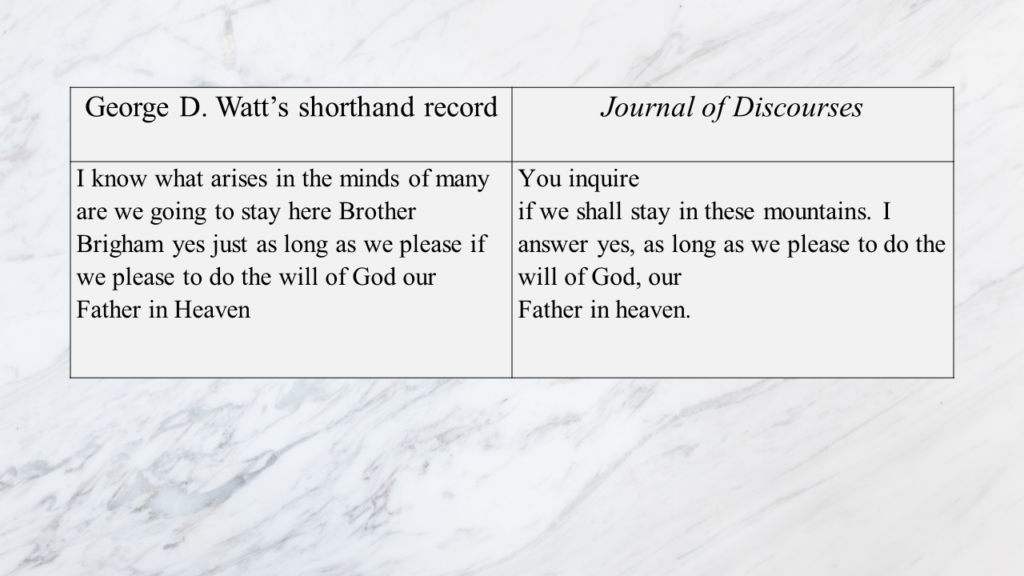

Questions to Statements

Brigham Young frequently addressed the congregation with questions, but this was not known until I transcribed the original shorthand and started comparing it to the Journal of Discourses. Here are two examples:

“Can you bring up instances where the righteous have suffered like the wicked? You cannot, it is not to be found.”

“I know what arises in the minds of many: are we going to stay here, brother Brigham? Yes. Just as long as we please to do the will of God our Father in heaven.” So, the shorthand is a direct question: he’s quoting people, or he’s quoting what he knows about what people think, “are we going to stay here?” And it’s changed to an indirect question, a statement.

Questions to Statements – Why Does it Matter?

Brigham Young’s questions often showed understanding or invited introspection and thought. When Watt changed his questions to statements, he changed the depiction of Brigham Young that has come to us through his words. Brigham Young was a much more understanding, caring, and likeable person, and spoke with much, much greater power, according to the shorthand record.

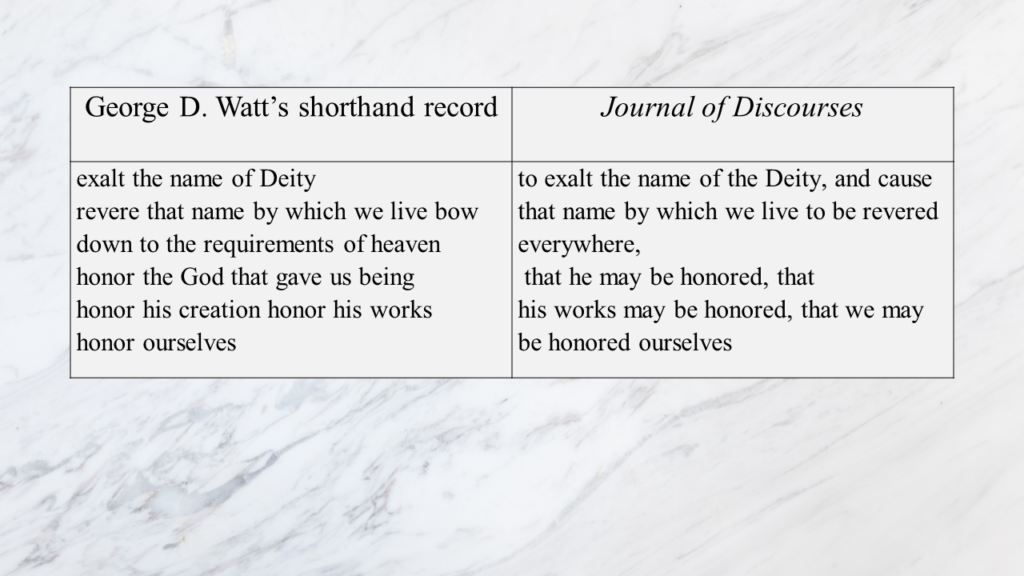

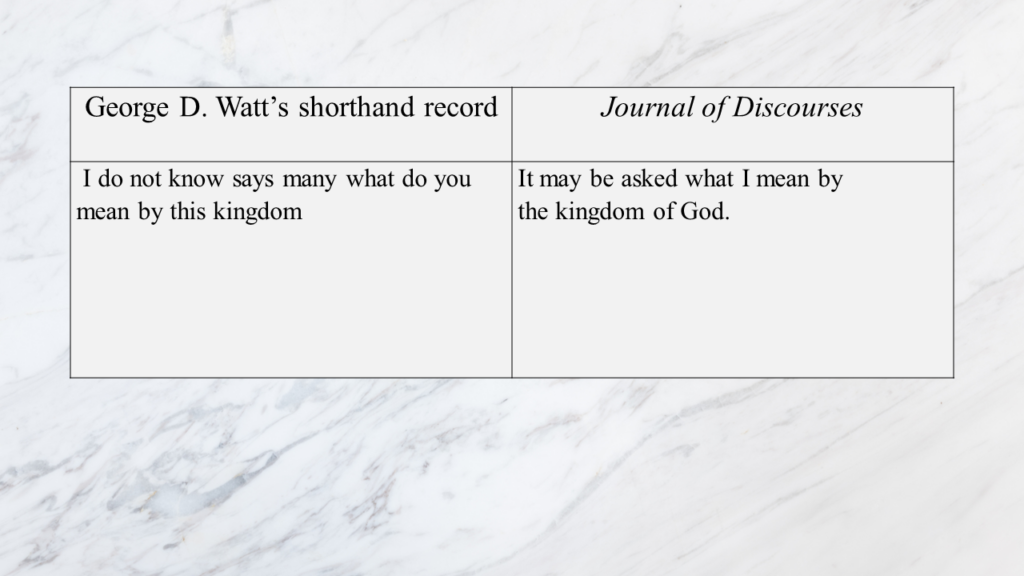

Active to Passive

Watt changed many statements from active voice to passive voice. This changed the emphasis from who performed the action to the action itself, or to the recipient of the action. Notice the change in energy in the following quote, as active voice was changed to passive.

“Exalt the name of Deity. Revere that name by which we bow down to the requirements of heaven. Honor the God that gave us being, honor His creation, honor his works, honor ourselves.” It’s much more direct, it’s much more powerful.

The change from active voice to passive often obscures the subject or who did it, as it does in the next quote:

“I do not know says many what you mean by this kingdom.” Journal of Discourses: “It may be asked what I mean by this kingdom of God.” Again, it’s more direct. It’s more powerful.

And briefly, one more quote that we’ve already seen, changed from “Jesus says” to “it is written,” obscuring the identity of the speaker, and here it diminishes the authority. “Jesus says,” is far more authority than, “it is written.” “It is written,” could be written anywhere.

Active to Passive – Why Does it Matter?

Changes from active voice to passive often reduce the power and energy of a statement and shift the emphasis from the subject – who did what – to the action. And it is not what he said.

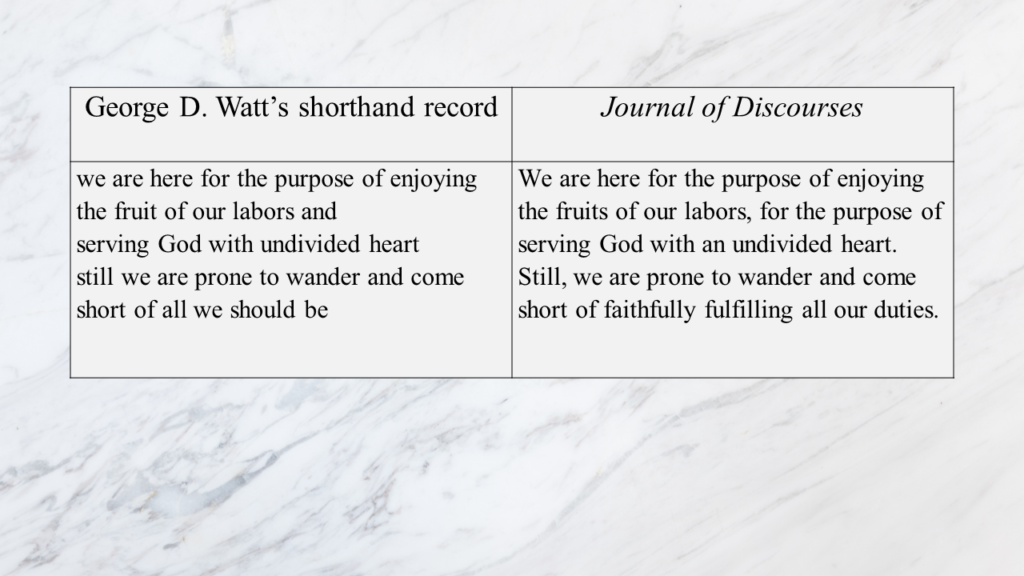

One last example how Watt’s alterations changed the meaning of the words that Brigham Young spoke. “We are here for the purpose of enjoying the fruit of our labors and serving the god with undivided heart. Still, we are prone to wander and come short of all we should be.”

Brigham Young said we are prone to come short of what we should be; Watt changed the words to we’re prone to come short of fulfilling our duties – a significant shift from being and becoming to doing.

Conclusion: What does it All Matter?

When George Watt and others changed Brigham Young’s words, when they omitted, twisted, added to, and otherwise changed what is in the original shorthand record – they changed the depiction of his personality. We’ve come to know Brigham Young through his words. And the printed versions of his sermons are at times a poor caricature of who he was and how he really spoke.

Also, accepting incorrect, altered words and doctrines as truth – as what was spoken – and making a judgment based on those words, is making a judgment on incorrect information. If you’re going to make a correct judgment, it needs to be made on correct information.

I’m also concerned that many pick up the Journal of Discourses and think they’re picking up a modern conference report, which it emphatically is not. Modern conference talks are written and rewritten and shared and vetted. These were spontaneous speeches, even at conference. It was considered almost a lack of faith to prepare beforehand: one was supposed to speak as guided by the Spirit. A spontaneous statement in a Sunday meeting is not the same as a conference talk and should not be given the same importance.

I’m often asked if the church is going to republish the Journal of Discourses. No. Most of the shorthand isn’t extant. It was lost. It was tossed after it was transcribed. And a lot of it is really irrelevant: there was one general conference about 1860, where the major theme of the conference seemed to be “keep your cattle out of the grain.” A lot of it is relevant. Brigham Young said, every young woman, every girl should learn to spin and weave – well, I’m all for that. But a lot of it isn’t relevant. And there really is no need to republish. However, all my transcripts are being released in the Church History Public Library.

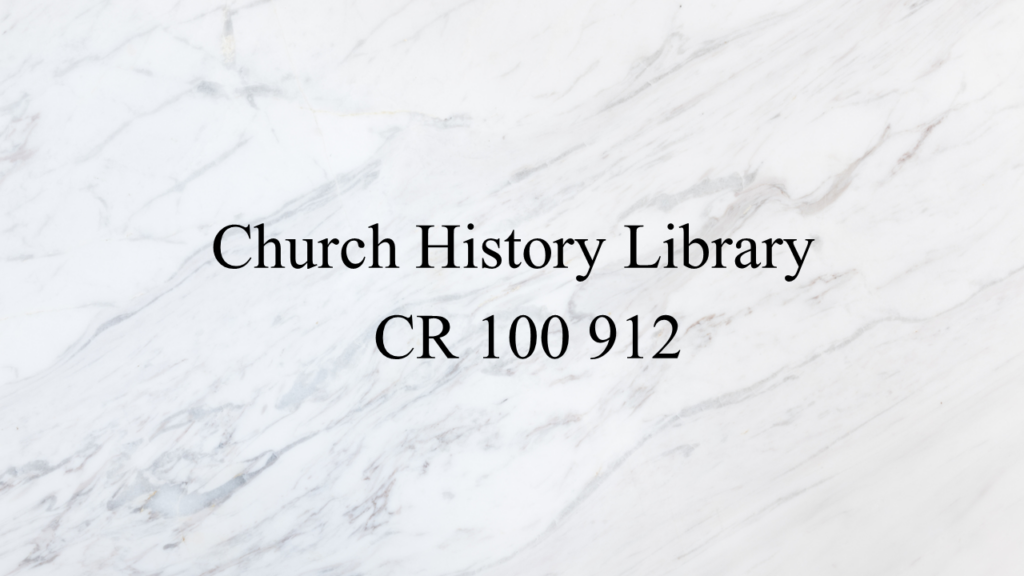

You can Google ‘Church History Library,’ there’ll be a search box. You can search for collection CR 100 912. There are three collections there. The first, “Lost sermons,” has a very few transcripts. The second, “Addresses and sermons,” has literally hundreds and hundreds of sermons. And the third, “Parallel columns comparisons,” contains over 50 sermons with the my transcript of the shorthand, the longhand transcript (when it is extant), and the text as published in Journal of Discourses. If you want to study Brigham Young’s words, that’s where to go.

Now, in conclusion, I’m going to read my two favorite quotes. A lot of what Brigham Young said about himself was not transcribed. He was baptized in 1832. He had explored church after church after church and had not found one that agreed with the Bible. So, when he encountered Mormonism, he was skeptical — he had been disappointed so many times — and he investigated it for two years before he was baptized in April 1832. In the fall of that year, he went to Kirtland to meet Joseph Smith for the first time. The first quote is a description he gave in 1859 of a conversation he had with a friend on his way to meet Joseph Smith.

“I recollect when I was going to see brethren for the first time, one of my Methodist friends, I do not know whether Methodist or not but he was a preacher. I recollect calling on him; he began to tell what old Joe Smith [had] done . . . this, that, and [the] other thing. What [power did he do it] by? By the power of the devil! [He said that Joseph Smith was] one of wickedest men [to] ever live.

“Says I, hold on a little! Let me talk. Joseph Smith I have never seen, to my knowledge, though I have always lived close by him. And the revelations that the Lord has revealed through him is the same as he revealed through his ancient prophets and apostles, and by his Son Jesus Christ. I have taken the rule laid down there, and in the late revelations, to know whether they are true or not. [I thought], if they are true, the Lord will tell [me], he will answer [me], he will reveal [it to me]. Go to the Father in [the] name of Jesus Christ, and all these things shall be made known.

“Now, says I, I do not know anything about Joseph. But the doctrine [that has been] been revealed through him, I do know to be the plan of salvation according to the New and Old Testament[s], and the signs God has given me. He may act like the devil for aught I care: I did not call him to be a prophet, deliver the plates of [the] Book of Mormon [or] send Moroni to administer to him. And I had nothing to do with him, and do not care to the latest day he lived what he do. It is not my business to call in question an act of his life: he was in the hands of him that called him, and the doctrine, and the author could do as he pleased with his servant.”[4]

Then in April 1864, Brigham Young described his first meeting with Joseph Smith. I have transcribed thousands and thousands and thousands of pages of shorthand; this is my favorite quote.

“After I was baptized and built quite a number of branches, I had to see the prophet in the fall. I wanted the hand of [the] prophet in my hand, his eye to look in mine; I wanted to look in his eye, and I wanted to read that man’s heart, and I wanted to know for myself and not for another. I saw him and heard him speak; he was chopping in the woods. [He] stopped and shook hands with us. All right. He put down his ax. I said, I can chop this, so we chopped and loaded a little while, and then [he] said come, let’s go to the house.

“I knew then for myself and not for another. I wanted to see this man that dictated and led and guided and the Mormons. where they lived together. and then for the world I defy it to produce any community like this that is governed and controlled by words and words alone.”[5]

Brigham Young, in his own words, as he actually spoke. Thank you.

Scott Gordon

All right, so lots of questions. I’m going to combine some of them a little bit because there’s a lot of duplications. The first one is do you have plans to rewrite The Journal of Discourses and come out with a good version?

LaJean Carruth

I think I answered that. I’m transcribing as much as I can. I’m 71 I don’t have an heir. I have tried to teach some very, very brilliant people. I have a wacky brain: I can’t drive, I can’t do a lot of other things that normal people can do, but I can read shorthand. I have hopes for my daughter. We are releasing what I have transcribed, but not republishing the Journal of Discourses. Most of the shorthand is gone.

Scott Gordon

Is there any evidence that Brigham Young read this or approved this or actually gave some approval to what was published? Or do we know?

LaJean Carruth

There is scant evidence. On April 4, 1860, Brigham Young said, and I quote, “I never look at my sermons.” There are a couple of references before that about him reviewing them. But as I said, when George Watt transcribed, he made most of the changes as he wrote. If you’re writing longhand, and you leave out several lines, and you just keep writing longhand, the omission was made at that time. Brigham Young wasn’t behind his shoulder telling him to leave that out. And some of the changes like repeatedly changing the word “heart,” to “mind,” and questions to statements, passive active: the patterns are pervasive, and we know it wasn’t how he spoke.

LaJean Carruth

Heber C. Kimball, got up one day. John V. Long was the shorthand reporter. This was on April 6, 1864. And as he was speaking, he said: “Here is our reporters, here is George D. Watt. More than half his time with writing revelations and John Long’s will bel but do not stick in your own stuff put in words said.” [6]. And during the Utah war, there was a newspaper reporter from somewhere in the country; there are a few pages of what he wrote about Brigham Young, and he’s talking about how hard the editors had to work to make his speech better. So, you know, the overwhelming evidence from the transcripts themselves is Watt and the other shorthand reporters made the changes. And some of them were read to Brigham Young, but there’s no evidence that these changes were his. In the collection I told you about, there are several sermons where I have the longhand transcript is extant and I put it in all the parallel columns. So, you can see, you can look at the longhand transcript and see what I’m talking about, where the changes are made. That’s the collection of those up there, the CR 100 912.[7]

Scott Gordon

And I think you’ve already answered this question, but I’m going to ask it again, just to make sure everybody’s really clear. It says but couldn’t Watt be expanding on his notes, at least some cases based on his memory of what Brigham Young said?

LaJean Carruth

You know how it is, somebody asks you a question over and over again, and you finally come up with an answer. And then nobody asks you. If anybody here can stand up and give me a verbatim account of a sacrament meeting talk from last Sunday, I want to talk to you. We don’t have that kind of a memory. Some of the ancients and non-literate societies apparently did. But no; and we don’t know. There’s no indication how much time went between when he took it down and when he transcribed it, and I do not believe that he would write “heart,” and then say “Oh, yeah, I wrote ‘heart’ again, but he really said ‘mind.'” Over and over and over — no that’s unsupportable.

Scott Gordon

Does the shorthand record clarify the Adam God statements?

LaJean Carruth

This is my personal – and only my personal take – on Adam God. Brigham Young said one day “let doctrine alone you do not understand.”[8] I don’t understand Adam God. Unfortunately, the shorthand for his sermon on April 9, 1852, is not extant. That was a significant Adam God talk. He did teach it. I’m sorry. I’ve got a good mind. I cannot understand Adam, God. There are some teachings scattered throughout.

Scott Gordon

Brigham Young’s infamous February 1852 speech before the territorial legislature regarding black people and the priesthood appears to have been recorded by George D Watt. Do we have the original shorthand of that speech?

LaJean Carruth

Yes. And it has just been released[9]. Paul Reeve, U of U Professor Paul Reeve and Christopher Rich and I have just re-sent back to Oxford University Press, the final manuscript of our book (it’ll probably be out in a year) called This Abominable Slavery.[10] The 1852 territorial legislature was the earliest record we have of the priesthood ban, Brigham Young’s speech of January 23, 1852. Brigham Young, in a conversation, just said, “They can’t hold the priesthood.”[11] And it’s apparent from the conversation that everybody knew about it. It wasn’t news. Somewhere between 47 and 52, this was set in place. We don’t know why. If you want a history of the priesthood ban, the best is Paul Reeve’s book Religion of a Different Color. And then our book that will be out in a year. These documents have recently been released to the Church History Library public catalog. Some of them are Orson Pratt’s famous anti-slavery speech, where he said, “to enslave the African because his skin differs in color to ours is enough to cause this angels in heaven to blush,” that is now released. It was I think, January 27, 1852[12]. If you go to this collection, and then scroll down to the Utah territorial legislature, but Brigham Young’s talks and Orson Pratt’s talks and Orson Spencer’s talks are under their name, you can find them. Again, these have just been released to the public catalog. Brigham Young was a person of his time; he said things that we wish he didn’t say: but, you know, I’ve said a few things I wish I hadn’t said either. We don’t excuse them. But we can extend understanding.

Scott Gordon

Where can we get a copy of that last quote by Brigham Young when he first encountered Joseph Smith?

LaJean Carruth

Oh, that’s easy. It’s in the same collection. It’s in the same collection was up there. The first quote about his encounter with a preacher was April 7, 1859.[13] The one about his first meeting with Joseph Smith was November 20, 1864[14] And you’ll have to find them in the speech. I think I’m right; if I’m wrong, write FAIR and I’ll give you the correct date. But I think that’s the correct dates. I love those quotes. I just love — they’re pure Brigham Young.

Scott Gordon

So, do you have any thoughts about what George Watt’s motivation was in making these changes?

LaJean Carruth

Everybody did it. I was given some Quaker sermons to read by the Friends Historical Society library. And there’s one speech that they started out on fairly accurately, and then went like this, and by the end, the shorthand and contemporaneous transcript were vaguely on the same subject. I transcribed 1400 pages of shorthand from John D. Lee’s trials for the Mountain Meadows massacre and developed PTSD. There’s one of the closing arguments in the first trial that the transcript made soon after the trial is basically a novel. They — the transcriber did a page and a quarter I think it is quite accurately. The shorthand’s miserable. I had two shorthands — had to claw my way through that with two shorthands — we couldn’t align them. The previous speaker, Janice Johnson, and I were working together to align them – you cannot align them, they’re just completely different. He just sat down and typed. This is just what they did. I’ve done court cases, I’ve done journals. I did Quaker sermons. I did the memoirs of Joseph Smith III, the later memoirs for the RLDS church. It’s just what people did; everybody did it. And that’s not an excuse but it is understanding, because we’re all people of our times and their ideas of accuracy were very, very different.

Scott Gordon

Are you telling me they didn’t have video cameras back then to record everything? Or their cell phones?

LaJean Carruth

Yeah. Oh, what I would give for one!

Scott Gordon

So finally, this is a statement not a question, actually. It says, “Now you know why we don’t quote from the Journal of Discourses in church magazines!” (Comment submitted by Michael of the Liahona.) Thank you very much for your time. Really appreciate it.

BYU Studies article: Gerrit Dirkmaat and LaJean Purcell Carruth, “The Prophets Have Spoken, but What Did They Say? Examining the Differences between George D. Watt’s Original Shorthand Notes and the Sermons Published in the Journal of Discourses,” BYU Studies 54:4.

Preached vs. Published, a three part blog published by the Church History Department:

Transcriptions in Church History Library Catalog are in collection CR 100 912.

[1] Ronald D. Watt, “The Beginnings of The Journal of Discourses: A Confrontation Between George D. Watt and Willard Richards,” Utah Historical Quarterly (2007) 75 (2): 134–148.

[2] “Journal of Discourses”, in Ludlow, Daniel H. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 769–70.

[3] For complete transcript of this sermon, see Brigham Young, 23 December 1866.

[4] Brigham Young, 7 April 1859; transcribed from George D. Watt’s shorthand record by LaJean Purcell Carruth; punctuation and capitalization added.

[5] Brigham Young, 20 November 1864; transcribed from George D. Watt’s shorthand record by LaJean Purcell Carruth; punctuation and capitalization added.

[6] Heber C. Kimball, 6 April 1864, transcribed from John V. Long’s shorthand record by LaJean Purcell Carruth; punctuation and capitalization added. This comment shows his awareness and disapproval of the alterations made in the transcription and publication of his sermons.

[7] CR 100 912, Parallel Column Comparisons.

[8] Brigham Young, 19 February 1854; transcribed from George D. Watt’s shorthand record by LaJean Purcell Carruth.

[9] Brigham Young, 5 February 1852; transcribed from George D. Watt’s shorthand record by LaJean Purcell Carruth.

[10] For a collection documents on slavery and the priesthood ban, see This Abominable Slavery.

[11] Brigham Young, 23 January 1852; transcribed from George D. Watt’s shorthand record by LaJean Purcell Carruth.

[12] Orson Pratt, 27 January 1852.

[13] Brigham Young, 7 April 1859; transcribed from George D. Watt’s shorthand record by LaJean Purcell Carruth.

[14] Brigham Young, 20 November 1864; transcribed from George D. Watt’s shorthand record by LaJean Purcell Carruth.