The Twelve Apostles during the Second British Mission, 1839-1841

The Twelve Apostles During the Second British Mission, 1839-1841

Elizabeth Kuehn

August 2019

Summary

Elizabeth Keene explores the Second British Mission of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (1839–1841). She highlights not only the spiritual and logistical efforts of the missionaries. Especially the overlooked sacrifices and voices of their wives left behind. She argues that these correspondences humanize early Church members and challenge us to better preserve and amplify women’s experiences in Church history.

Introduction

Scott Gordon: I’m excited about hearing our next speaker, Elizabeth Keene. Elizabeth received her Bachelor of Arts in History from Arizona State University. She received a Master of Arts from Purdue University in History, with a focus on religious history and women and gender studies in early modern European history.

She entered a doctoral program in history at the University of California, Irvine, and became a PhD candidate there in 2011. In 2013, she worked as a documentary editor and historian on the Joseph Smith Papers Project, based at the Church History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah.

She’s a co-editor of several documentary editions of the Joseph Smith Papers, including Documents, Volume 5. Both of which were published in 2017. She is currently the lead editor on Documents, Volume 10: May to August 1842, forthcoming in spring of 2020. There’s more there — but with that, we’ll turn the time over to Elizabeth Keene.

Presentation

Elizabeth Kuehn: Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be with you and to follow Angela’s remarks. I think our talks will blend well with each other.

Gender Imbalance in Historical Records

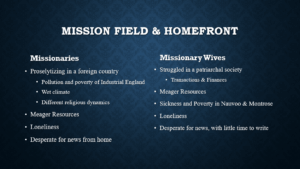

It is a sad truth that there is a profound gender imbalance in the contemporary records we have for early Latter-day Saints. The documents created by men were prioritized, published, and preserved. The records of male Church leaders–their public sermons, letters, and journals–were valued by the institutional Church and preserved by the historian’s office.

While some women’s records were kept by the historian’s office, they were often catalogued under their husband’s name or scattered across collections. This makes them hard to locate. Most records written by women were passed down through families. Some were eventually donated to the archives. Many others were lost over time.

This imbalance has made it more challenging to find and include women’s voices and experiences in narratives of Church history. This imbalance also makes it particularly difficult to compare the experiences of men and women to the same event or circumstance. And makes it difficult to analyze how they reacted.

There are a few moments where such comparison and analysis are possible in early Church history. Where the sources exist to provide multiple perspectives from both women and men.

The Second Latter-day British Mission–Words of the Apostles and Their Wives

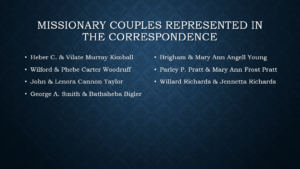

One such moment that I would like to focus on in my remarks today is the second British mission. This was a mission undertaken by the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles from 1839 to 1841. Over the course of these two years, the apostles and their wives exchanged dozens of letters.

While there are still far more surviving letters from men, the Church History Library has hundreds of extant letters from both the apostles and their wives. The women’s letters balance the story, reminding us about what the missionaries left behind. They provide insights into the families’ circumstances in Illinois and Iowa during these challenging years.

I started this research four years ago as an outgrowth of trying to find more contemporary records written by women in Nauvoo for use in annotation in the Joseph Smith Papers. As I became more familiar with the content of the letters, I was fascinated by the different ways the women and men reacted to their extended separation and their personal sentiments the letters contained.

These letters were the only way for these missionary couples to communicate. In our era of instant messaging, texting, and video chats, we have less appreciation for the loneliness and desperation for news that these men and women experienced during these two years of separation.

Humanizing the Early Saints

With the exception of journals such as those kept by Wilford Woodruff, these letters are also the most contemporary sources available. They document events as they happened and as they were communicated to their distant spouse. These are not the reflective compositions of autobiographies and memoirs. They are more automatic responses that capture the raw emotions and fears in the moment.

This was the couple’s only means of communicating. As such, many contained personal notes and sentiments that would normally be expressed privately and often never recorded. In that regard, some of these letters may best be described as love letters. But they usually contain both broadly important news and personal moments.

These letters and the emotions they capture help to humanize the early Saints. This is one of the many goals of the Joseph Smith Papers Project. It aims to make the early Saints more relatable. To show that they were women and men like you and I. And to hopefully take them off the idealistic pedestals we have a tendency to put them on in the Church.

I don’t mean to detract from their considerable faith, sacrifice, or perseverance. I hope this presentation demonstrates their powerful testimonies of the gospel and their willingness to sacrifice. And help us recognize that they were complex human beings. Their lives were far from perfect. We have a tendency to glorify their spiritual highs without recognizing their personal lows.

Relating to and Learning From Early Saints

I believe the struggles of the apostles and their wives are ones that we can relate to and learn from. In my research, I found the embedded testimonies of the gospel expressed in these letters especially poignant. Particularly those written by the apostles’ wives. I have desperately wanted them to be more widely known so that members of the Church today could understand the conviction of Phoebe Woodruff. The fortitude of Mary Ann Young. The patience of Bathsheba Bigler. The devotion of Vilate Kimball. And the forbearance of Leonora Taylor. Women who you may have no knowledge of, though their husbands are often well known.

Too often, when it comes to missionary work in the early Church, we follow the story of the missionaries and forget the family they left behind. That is frequently a result of using missionary journals as our main source and having little or no sources to document the family’s experiences while their missionary father is absent.

The precious letters of the second British mission allow us to better understand not only the missionaries’ experiences but the sacrifices endured by their families.

But before we get to the second British mission, I want to provide some background on the first mission to England and its historical context.

Background on the First British Mission

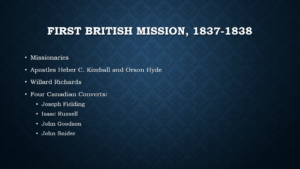

In 1837, amid a worsening national economic crisis and rising dissent among the Latter-day Saints in Kirtland, Ohio, Joseph Smith instructed Heber C. Kimball to lead a mission to England. He approached Kimball in the Kirtland Temple in early June 1837. Joseph told Heber he had received a revelation that he should go to England to “open the door of proclamation to that nation and heed the same.”

In many narratives of this period in Kirtland, Joseph Smith’s direction to Kimball is characterized as a sudden decision. To reassert leadership and divert attention from dissenters who were opposing Smith and arguing that he was a false or fallen prophet leading the Church astray. Although the decision might have seemed sudden to some, it was actually a natural extension of Church leaders’ desire to spread the gospel widely.

In a November 1831 revelation, Joseph Smith commanded the Church to, quote, “send forth the elders unto nations which are afar off, unto the islands of the sea, send forth unto foreign lands.”

After the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was organized in February 1835, Joseph Smith directed the apostles to, quote, “travel and preach among the Gentiles.” He instructed them that they held, quote, “the keys of the ministry to unlock the door to the kingdom of heaven unto all nations and to preach the gospel to every creature.”

Expanding Missionary Work

Over time, England became the first logical step to expand missionary work overseas.

In his autobiography, Parley P. Pratt recalled a blessing that Heber C. Kimball had given him. He prophesied that Pratt would preach in Canada and there find a people prepared for the fulness of the gospel. Kimball’s blessing also promised, quote, “From the things growing out of this mission shall the fulness of the gospel spread into England and cause a great work to be done in that land.”

Shortly after the dedication of the Kirtland Temple in March 1836, Pratt set off on a mission to Canada. For the next six months, Pratt preached in and around Toronto and converted over a dozen people. Among those he baptized were several recent immigrants from England. They include John and Leonora Taylor, Isaac Russell, John Goodson, John Snyder, and the Fielding siblings: John, Mercy, and Mary Fielding.

When Pratt returned to Canada the following spring, he found that these converts had informed their families in England about joining the Church and were eager to share the gospel with them. The Fieldings had written to their relatives, including their brother, Reverend James Fielding, who read their letters to his congregation.

Canadian Elders

In his autobiography, Pratt recalled that, quote, “Several of the Canadian elders felt a desire to go on a mission to their friends in that country,” end quote. Indeed, four of the seven elders who were part of the first British mission were Canadian converts.

Sending Kimball to England may have reasserted Joseph’s authority over the Twelve Apostles. Many of whom were among the dissenters opposing him in the summer of 1837. But it created additional tension between Smith and Thomas B. Marsh and Parley P. Pratt. Both Pratt and Marsh had intended to participate in a mission to England. Each had to reconcile the prophet’s decision to exclude them.

There is also no indication in the surviving documents for this period that the first mission was widely known among the Latter-day Saints in Kirtland. There were no farewell addresses, no announcements in the local Church newspaper. Only a small group of family and friends accompanied the departing missionaries to the harbor in Fairport. As such, it may not have combated the influence of dissenters as much as some scholars have assumed.

Heber C. Kimball was overwhelmed by the call to lead the mission. Writing later in his autobiography, Kimball noted that he, quote, “believed the time would soon come when I should take leave of my own country and lift up my voice to other nations. Yet it never occurred to my mind that I should be one of the first commissioned to preach on the shores of Europe.”

From New York to Liverpool

He departed Kirtland with Apostle Orson Hyde, Joseph Fielding, and Willard Richards on June 13th, 1837. They were joined by three of the Canadian converts — Russell, Goodson, and Snyder — in New York. The men worked to raise money for their passage and were finally able to set sail for England at the end of June. Their ship arrived in Liverpool on July 19th.

Correspondence

Unlike the numerous letters we have for the second British mission, there are only a handful between the missionaries and their families during this first mission. The largest collection of extant correspondence was exchanged between Heber C. Kimball and Vilate Kimball. Heber recounted the wonders of Europe and the disparity he saw between rich and poor. Vilate related the waxing and waning of dissent among the Saints in Kirtland and copied Joseph Smith revelations into her letters.

Siblings Joseph and Mary Fielding and Willard and Hubsaba Richards also wrote to each other. Joseph Fielding told his sister how their brother James had initially welcomed the missionaries. He allowed them to preach to his congregation in Preston, England. But as the missionaries converted more and more of his parishioners, his support waned. He soon refused to have anything to do with them.

Despite the rejection by his family, Joseph Fielding and his fellow missionaries proved successful in Preston and the surrounding area. By April 1838, the missionaries had converted over 1,000 members and established 20 branches of the Church in Preston and the surrounding area. Among their converts were individuals who would play meaningful roles in the future Church, including George D. Watt, William Clayton, and Janetta Richards — who would marry Willard Richards in the fall of that year.

Kimball and Hyde prepared to return to the United States in April, leaving Joseph Fielding in charge of the British Saints, with Willard Richards and William Clayton acting as his counselors. By the end of May 1838, Kimball and Hyde had returned to Kirtland. There they found a divided community and a group of Latter-day Saints preparing to travel to Far West. They joined the Saints heading west and arrived in Missouri in late July 1838.

Preparing for a Second British Mission

On July 8th, 1838, Joseph Smith received several revelations setting Church affairs in order and planning for the future. One of these revelations, now canonized as Doctrine and Covenants section 118, was directed to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. They were instructed to undertake a mission over the great waters and return to England as a quorum the following year. The revelation further directed that John Taylor, John E. Page, Wilford Woodruff, and Willard Richards be appointed apostles to replace those who had left the Church or died.

What had appeared to be an easy feat — setting out from the Far West temple grounds — became far more difficult a year later. The Saints had been forced from the state of Missouri and threatened with violence should any return. Yet despite the danger, several of the apostles gathered in Far West on April 26, 1839. They held a meeting to officially start their mission and set apart new apostles, including 21-year-old George A. Smith.

However, after holding the meeting specified in Joseph Smith’s 1838 revelation, they did not leave from Far West for England. Most of the missionaries would not arrive in England until between January and May 1840. Instead, they returned to their families in Montrose and Nauvoo. They spent their time receiving instruction and directions from the Prophet and setting their temporal affairs in order.

Off to England

By early July 1839, the missionaries had finished their preparations. On Sunday, July 7, 1839, hundreds of Saints from Illinois and Iowa gathered in Nauvoo to hear the farewell addresses of members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and Quorum of the Seventy who were leaving for England.

Sidney Rigdon addressed the missionaries, discussing the persecution and trials they would likely face while proselytizing. Woodruff recorded that Rigdon’s address, quote, “was of such a nature and appealing to our affections in parting with our wives and children, and the peculiarity of our mission, the perils that we might meet with, and the blessings that we should receive, that tears were brought to many an eye.”

After Rigdon, Joseph Smith spoke on a similar topic — the potential imprisonment and injustice the missionaries might face while preaching in England. Joseph alluded to the circumstances he had endured while imprisoned in Missouri, saying:

“Remember, brethren, that if you are imprisoned, Brother Joseph has been imprisoned before you. If you are placed where you can only see your brethren through the grates of a window while in irons because of the gospel of Jesus Christ, remember Brother Joseph has been in like circumstances also.”

“Reflections”

After recounting the day’s events in his journal, Woodruff concluded his journal entry with a section labeled “Reflections.” There he wrote:

“May the Lord enable us, the Twelve, ever to be more meek and humble, to lie passive in His hands as the clay in the hands of the potter. And may we ever realize that while we are in the service of God in doing His will, that though we may be surrounded by mobs and threatened with death, that the Lord is our deliverer, and He will support us in every time of trouble and trial.”

Woodruff and his fellow apostles had prepared themselves and their families spiritually and temporally. But the heavy emotional toll that would result from their separation was something they could not easily prepare for. While many 19th-century Latter-day Saint missionaries were married, most missionaries to this point were absent for weeks or months, not years.

The extended duration of the Twelve Apostles’ mission likely created a more pressing desire for frequent correspondence. This resulted in an impressive number of letters. A majority of which have survived and been preserved.

These letters are rare for the sheer number that have survived, as well as the number of letters written by women. 19th-century correspondence is often one-sided and predominantly male-centric.

Mission Delayed

Although the Twelve had given their farewell addresses and made their preparations to depart, their mission was unexpectedly delayed. Members of the Church in Illinois and Iowa began contracting malaria from the mosquitoes that were prevalent in the swampy floodplains around Nauvoo. Described as fevers and ague — meaning chills — Latter-day Saints of all ages contracted the disease.

By July, the disease had reached epidemic proportions, and hundreds were bedridden. Many Saints died that summer and in the following months and years as a result. This significantly delayed the missionaries, as they and their families fell ill. Because of their poor health and destitute circumstances, the potential missionaries did not leave as a large group. They staggered their departures as each felt they were well enough to travel and could leave their ailing families.

By early August, the first of the missionaries, Wilford Woodruff and John Taylor, set off. But they were far from healthy. Desirous to begin their mission, most of the departing missionaries left home while still ill or in the early stages of recovering. They found it necessary to rest and recover, often dependent on the care of strangers as they traveled east with limited funds.

Over the next several months, the other missionaries also left Nauvoo. Many were forced to stop along the way, either because of their ill health or their need to work to acquire funds to travel. The cost and time needed to travel to the eastern United States meant that it took the men months to finally gather as a quorum in New York City. From there, Woodruff and Taylor set sail for England in December. Young, Pratt, and others waited until March 1840 to leave for Britain.

Mission Challenges for Wives and Families Left Behind in Their Own Words

As difficult as the missionary circumstances were, the situation of their wives and children was much worse.

Most of the women were ill themselves and struggled to care for their young families, many of whom were also sick. Mary Ann Angell Young had given birth only 10 days before Brigham left in mid-September. Phoebe Woodruff was several months pregnant when Willard left. Nearly all of the families were left in impoverished conditions. They were financially dependent on kind neighbors and Church leaders for their care.

Joseph Smith had promised that the families of the Twelve would be provided for. With the limited resources of the Church, this was not easily realized. As the women noted in their letters, there was often a great distance between the promise and reality. Turning to the bishop for help was not always possible.

Lenora Taylor’s Experience

Lenora Taylor wrote that Bishop Vincent Knight had promised to pay her in bread and meat, as he had no money to offer. Vilate Kimball wrote:

“I have but one dollar of all that you left with me. I get not much from the bishop but bread and meat, and sometimes can’t get that. But I have the best of neighbors, so we do not suffer.”

With the absence of their husbands, conducting business and providing for the family’s needs fell squarely on the women’s shoulders. Each of the women mentions financial concerns in their correspondence.

Lenora Taylor and her children were forced out of the room in an old barracks in Montrose that they were sharing with Brigham Young’s ill family. She struggled to find a place for her family to stay with their meager finances. Writing to inform John how she had spent the money he had left with her, she listed the family’s need for medication, their cow going dry, and her one extravagance — the purchase of a single silver teaspoon.

Phoebe Woodruff moved five times during the course of her husband’s mission. She was threatened by two of her male neighbors with having all of her clothes and goods confiscated to pay for her sustenance.

Vilate Kimball

With a comfortable house, Vilate Kimball was better situated than most of the other missionary wives. She was able, with help from her neighbors, to plan ahead:

“Brother Joseph Young promised to get me a cow, and he has got me a good one, for which I feel very thankful. Brother Hubbard gave me a pig last spring, which I think, if well fattened, will make our meat for winter. I have plenty of potatoes and turnips, so I shall not have to buy much but bread.”

In perhaps the most financially dire straits, Mary Ann Young insisted that the family’s circumstances were poor but comfortable in her letters to her husband. It was only after Vilate Kimball wrote to Heber, noting that the Young family was living in a partially constructed home she would hardly call a shelter, that Brigham realized the extent of their circumstances.

Traveling without purse or scrip and dependent on the charity of others, the missionaries likewise found themselves in fluctuating financial circumstances. Each remarked on the generosity of the English Saints and thanked God for their needs being met.

Moving to England

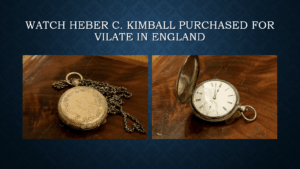

At various points in their mission, many of the men found themselves able to send money or gifts home. Fabric, shoes, or this watch. Realizing the difference in the cost of living between England and New York, Parley P. Pratt urged his wife to sell their household goods and bring their family to live with him more cheaply in England.

He refused to take no for an answer, writing:

“Courage, Mrs. Pratt. You have performed more difficult journeys than this, and if you will take hold with courage, the Lord will bless and prosper you and our own little ones and bring you over in safety.”

In asking this, Pratt revealed the most profound sacrifice identified by the missionaries: their separation from their wives and children. Traveling to what they described as a new world, a foreign land, and a strange land, left these men in unfamiliar surroundings and largely dependent on strangers.

This lengthy mission to England also removed them from their community and their domestic roles as husbands and fathers. In his letters, Brigham Young expressed his worry to his wife that the children would not recognize him when he returned.

The Children’s Experience

Lenora Taylor sadly related an incident to her husband where their youngest son, seeing Abraham Smoot, thought he was his father and ran and embraced his legs, repeating, “Papa, Papa,” only to be corrected by his mother and told that his father was still gone.

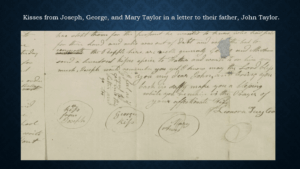

Each of the fathers sent kisses to their children, instructing their wives to kiss them on their behalf. Likewise, the wives and children sent their kisses and well wishes to their husbands and fathers. In one letter, Lenora Taylor had each of their three children kiss the paper. She circled and labelled each as a kiss from that child.

Those men who had older children, like John Taylor, wrote separate instructions for each of their older children, providing them with fatherly guidance. They would remind them to be good, to study, and to mind their mothers.

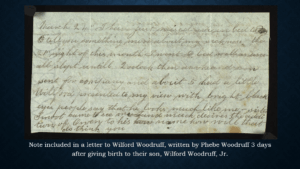

Phoebe Woodruff gave birth to their second child — a son she named Wilford — several months after her husband had left for England. As the time for the birth approached, Phoebe with increasing frequency wished that Wilford would return to her. She realized that was not possible, and relented that she knew the importance of the work he was doing and would not want to shorten his mission.

Dreaming of Being Together

That did not stop her from dreaming, however. She related how she dreamed that Wilford had returned to her, only to be crushed when she woke. Dreams of their spouses — and for the missionaries, of their homes in Iowa and Illinois — were a common occurrence.

Brigham Young related in his letters to his wife that he dreamed often of home and family. Dreams also seemed to foreshadow events, such as Wilford Woodruff’s dream that his young daughter, Sarah Emma, had died.

They also seemed to reassure. Heber C. Kimball, distraught about leaving his wife and family while sick, dreamed of an ill Vilate whom he raised from her bed, and she regained her strength. This comforted him, and he believed that she would be able to recover.

Several letters between the missionary couples relate having conversations and dreams during a time of disagreement. Both Vilate and Heber C. Kimball recounted dreams in which the other seemed distant to them. Heber went so far as to despair that the Vilate in his dream had turned a cold shoulder to him, while his wife wrote back that she believed such coldness would not be the case if they were actually together.

Longing and Loneliness

There is often a profound sense of longing and loneliness in many of the letters as they reflect on the distance between them and their spouses. As a postscript in one letter, Lenora Taylor wrote:

“I feel as if I want to get into this letter and go to you.”

Heber C. Kimball wrote to Vilate, noting:

“The love that I have for you has eclipsed all men’s on earth, and I believe it ever will while I live and through eternity, and then will never end. I am perfectly miserable out of your sight. I esteem you most precious of all things below this sun.”

He was very effusive. This is echoed in several of the women’s letters.

Phoebe Woodruff resolved that next time Wilford traveled to England, she and the children would go with him, as she was tired of being alone. Their devotion to their spouses was evident, as they each in their own way acknowledged what Heber C. Kimball plainly wrote:

“That no one in this world can make me as happy as you can.”

Brigham Young wrote that he loved his wife very much, even if he did not:

“Make quite so much a fuss about it as other men.”

George A. Smith, who had been courting his future wife, Bathsheba Bigler, before he was made an apostle and left for the mission to England, wrote in a December 1840 letter:

“I keep you still in memory, and the pleasant hours which I have spent in your society are also remembered, and the Lord willing, we shall see each other again and talk over matters. I am determined never to take another mission without you across the ocean, unless the Lord so order it.”

Request for More

Nearly every letter between the couples contains the request for more letters sent more frequently. Letters arrived, on average, about two months after being sent. With delays, some letters took four or five months, and some of those sent never arrived at all.

Many of the couples wrote letters in response to their spouse’s letters as they received them. Vilate and Heber C. Kimball wrote each other even more frequently, not waiting for a letter to arrive before starting on a new one.

In fact, Brigham Young commented on this frequency in a letter to his wife six months after leaving home, writing with evident envy:

“Brother Kimball has just received another letter from his wife, but Brother Brigham has received but one since he left home. I wish you would write but a few lines to him to comfort his poor heart.”

Later in the same letter, he coyly wondered if sending Mary Ann a provocative love letter would entice her to write. In the next sentence, he dismissed the possibility and said he was ashamed at the thought. He told her not to show the letter to anyone.

Woodruffs’ Misunderstanding

Through a misunderstanding, the Woodruffs experienced a delay of several months before they started corresponding regularly. Each was waiting for the other to write first, so for two months no letters were sent. Finally, Wilford broke the stalemate, asking Phoebe why she had not written to him. Phoebe replied that she’d been waiting for him to write.

Phoebe also faced further difficulties in writing. She was several months pregnant and caring for their toddler daughter, Sarah Emma. Experiencing what must have seemed an unendurable silence from his wife, Wilford Woodruff wrote more and more frequently, numbering the letters he sent—likely afraid that they were not being received.

Gratitude

In their letters, the apostles frequently expressed gratitude for the letters they received from their wives. Heber C. Kimball called one of his letters from Vilate a “tender morsel,” and wore another “threadbare with handling.”

However, sometimes letters were too limiting, and the couples noted their desire to be in each other’s presence. John Taylor related to his wife his eagerness to sit down with her in their chimney corner and talk about things past and new. Vilate longed to hear Heber’s gentle voice. Parley P. Pratt fondly remembered his last kiss with his wife.

In 1841, in one of his last letters from England, Brigham Young began by writing:

“Beloved Mary Ann,

This evening I have a few moments to converse in a lonely way. I am thankful I have the privilege of this letter, but I want to be where I can speak to you face to face. And the time is near at hand when we shall start for home.”

Health and Well-Being

Another shared and oft-repeated concern was news about their health and well-being. Nearly every letter between these couples includes reports on their own health, the health of others, and requests for information on the health of their spouse. Death was a very real fear. At several points both husbands and wives despaired that they would not see their spouse in this life and expressed their hope to be reunited eternally.

In fact, having accurate information relating to the welfare of their families was such a deep concern that the letters between the couples often mentioned the health of family and friends. Realizing those on the other side of the ocean needed reassurance, the wives commented on the general state of the other missionary wives and their children. The men commented on their fellow apostles’ health.

However, not all information was meant to be shared. Learning that a doctor had seen an ailing, pregnant Phoebe Woodruff, Lenora Taylor relayed to her husband that the doctor had said that Phoebe’s present situation was a difficult one and things would “go hard with her” pregnancy. She counseled her husband to keep this news from Brother Woodruff.

Frankness

Some couples were willing to be much more frank in discussions of health and well-being than others. After some dissembling letters between the couple that left Heber unsure where Vilate intended to move, he requested they be more familiar with each other and tell each other their situations clearly.

After relating how he had fainted and come very close to death because of malaria, Heber C. Kimball wrote:

“My dear companion, do not feel bad because I have told you the truth, for this I agreed to do when I left home. Now do the same for me, then we will be even.”

Following this direction, in a non-extant letter, Vilate apparently told him what she had suffered in his absence. She had come quite near to death herself and been tried and tempted. This deeply affected Heber, who replied that:

“I could cry like a child if I could get by myself.”

He mourned that he could be the cause of her suffering and assured her that he prayed for her constantly. As part of the letter, he pronounced a blessing on Vilate, asking God to deliver her from temptation and sorrow.

Fear of Death

Parley P. Pratt, learning from a letter from his wife, Mary Ann, that she and their children were dangerously ill with scarlet fever and not able to travel to England to be reunited with him as they had anticipated, expressed his fears and anxiety in a letter. After reading the troubling letter, he wrote:

“I cannot taste food; my feelings are such that my stomach will not bear it.”

Later in the letter, as he was overcome with fear for his family’s health, he asked Mary Ann:

“Why must we live separate? Why must I be forever deprived of your society and my dear little children? I cannot endure it. Why do you not come with me when I pressed it upon you last winter? Why did you not come now? My heart bleeds with a wound that is insupportable. I cannot endure it—and yet I must.”

Realizing that with these pleas he had seemed to place the blame for the family’s sickness on Mary Ann’s decision not to come to England, he clarified:

“But don’t for a moment suppose I blame you for not coming. It is only my feelings, which I cannot help expressing in the anguish of my heart.”

Pratt, in his letter, then pleads in a written prayer for his family to be healed. Unable to do anything themselves, Pratt, Kimball, and the other missionaries prayed for a loving God to do what they could not. To heal, bless, and protect their families.

Hope of Eternal Life

Pratt only had to face the prospect of losing his family and returned to New York to find them well. But the Woodruff’s two-year-old daughter died during the mission. Although Phoebe wrote him as soon as it happened, hers was not the first news to reach him. In a letter of consolation, he explained that he had seen their daughter’s name on a list of recent deaths in Nauvoo.

Recalling a dream he had had soon after leaving home, he told Phoebe that he had had conversations with her in his dreams.

“On one occasion Sarah Emma was not with us, and I inquired where she was, and you said she was dead and gave me something of an account of it. But as I had heard from you since, and she was well, it had almost slipped my mind.”

These dreams and warnings may have made his daughter’s death easier for him to bear. He also trusted fully in the hope of eternal life and being reunited with her one day.

Phoebe, although also resigned to the will of God, took little Sarah Emma’s death—only months after giving birth to her son—much harder. She was understandably distraught and lonely. She wrote that a gloom and darkness hung over her. Phoebe felt that the most trying aspect of their situation was that she and her infant son were her daughter’s only mourners.

Loneliness and Resilience

Phoebe had no relations to mourn with her. Although they were supported by friends and church members. Margaret Smoot especially, who lovingly prepared Sarah Emma’s body for burial. Wilford said he had discovered from his dream conversations with Phoebe that she had had:

“Many lonely hours and some gloomy meditations, as you were left alone so long and had no relations to keep you company. I know this is trying, and none would have borne it better than you have done.”

He praised her resilience. He reminded her of the many tribulations the Saints in all areas of the time had to endure, and the hope of the next life.

Eventually, Phoebe was able to echo Job, writing in her letter about Sarah Emma’s death:

“The Lord has given, and the Lord has taken away. Blessed be the name of the Lord.”

But the difficulties of her situation soon overcame her. She moved to her parents’ home in Maine for the duration of Wilford’s mission.

Missionary Couples’ Reactions to Their Struggles

These missionary couples reacted in disparate ways to the struggles they faced. But all believed in a loving God who would aid His children and reward their mortal trials. Heber C. Kimball characterized he and his wife’s period of separation as:

“One trial above the rest, so we have gained one more victory over the devil.”

Janetta Richards wrote a postscript in a letter Heber had composed to Vilate, offering her sympathy to her and the other missionary wives.

“I can truly feel for you and the rest of our sisters, who are called to sacrifice the company of so near and dear relation, and left as it were alone—though I must not say alone—for I believe that the Lord is and will be with you in their absence.

“Dear sister, we will lift up our hearts and rejoice, looking forward to that day when we shall meet never to part, which may our Heavenly Father grant.”

Loneliness and Isolation

Phoebe Woodruff reflected in one 1840 letter that those women who had never parted from the company of their husbands did not realize the blessing they had.

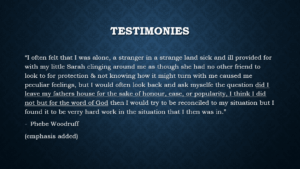

She further wrote of her great loneliness and isolation:

“I often felt that I was alone, a stranger in a strange land, sick and ill-provided for, with my little Sarah clinging around me as though she had no other friend to look to for protection.”

She continued:

“And not knowing how it might turn with me”—meaning whether she herself would recover her health or die—“that it left her with peculiar feelings.”

She then emphasized her commitment to the gospel, writing:

“But I would often look back and ask myself the question: Did I leave my father’s house for the sake of honor, ease, or popularity? I think I did not, but for the word of God.”

She concluded her letter noting that she would try to be reconciled to her situation but found it very hard work.

“In the situation that I then was in, once I had a kind Wilfred to cheer me in my lonely hour, but now I have none.”

Solace

Her husband tried to offer her solace in his letters, writing:

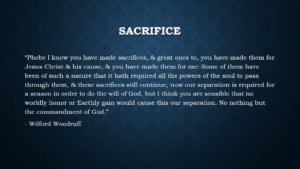

“Phoebe, I know you have made sacrifices, and great ones too. You have made them for Jesus Christ and His cause, and you have made them for me. Some of them have been of such a nature that it hath required all the powers of the soul to pass through them, and these sacrifices still continue. Now, our separation is required for a season, in order to do the will of God. But I think you are sensible that no worldly honor or earthly gain would cause this our separation—no, nothing but the commandment of God.”

Concerned about the impoverished conditions she faced and the sacrifices she was making, Brigham asked Mary Ann how he could help her. She replied that she would live anywhere, that no sacrifice was too much to bear.

This was a conviction recognized and shared by each of these couples as they resolved to do whatever was required of them to further the work of the Lord. The depth of Mary Ann Young’s and other apostles’ wives’ conviction may help us understand why they rarely discuss their trials in their letters.

Trials and Challenges

The apostles’ letters are sometimes quite direct and vulnerable in relating their trials and challenges. In contrast, their wives rarely go into such detail. They might mention poor health or challenging finances, but usually only in passing. None of the women offer an explanation for their reticence, so we can only guess as to their motivations.

Apostles’ Wives’ Frame of Mind

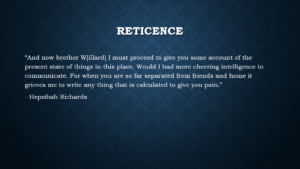

But Hepzibah Richards, in a January 1838 letter to her brother Willard—then serving in the first British mission—offers potential insight into the apostles’ wives’ frame of mind. She admitted her reluctance to share bad news with him.

“And now, Brother Willard, I must proceed to give you some account of the present state of things in this place. Would I had more cheering intelligence to communicate, for when you are so far separated from friends and home, it grieves me to write anything that is calculated to give you pain.”

Perhaps, similarly, the missionary wives were reluctant to burden their husbands with their hardships when they knew they had little ability to help. Nearly all of the apostles commented in their letters about the difficulty of inaction and only having prayer as an outlet to help their families.

These women realized firsthand the poverty Church members were facing and made do as well as they could. They avoided asking for additional assistance from Church leaders. Perhaps the women considered it their Christian duty to suffer in silence. Part of their commitment to the gospel and their husbands’ missionary labors.

Their humility in the face of daunting struggle is a testimony all its own. Although they rarely complained, we should not assume their circumstances improved or that it was a mark of cheerful forbearance. While the men felt free to expound their difficulties, their wives may have felt constrained by cultural or religious expectations.

Outcomes of the Second British Mission

Regardless of how openly they discussed their situations, the sacrifices of the missionaries and their families were of great significance to Church history. And the many thousands who joined the Church as a result of the apostles’ mission to England.

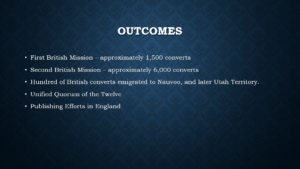

The spread of the gospel in Great Britain was unprecedented. The proselytizing of the first British mission had brought roughly 1,500 converts to the Church. The second British mission resulted in several thousand more. By April 1841, the last conference the missionaries held as a group in England, Church members there numbered just under 6,000. There was an increase of over 4,000 members in a year’s time.

Many of these converts would immigrate to the United States and join the Latter-day Saints in Nauvoo. Or later in Utah. The mission had many other successes, such as unifying the Quorum of the Twelve and the Church’s many publishing ventures started in England. But to my mind, these pale in comparison to the missionary work and the influx of members who would expand and reinvigorate the Church in the 1840s and 1850s.

Thank you.

Q&A

Question:

This question asks: Were you surprised to find so many letters and documents about the lives of the women?”

Answer:

Yes, this is a very surprising collection. It’s been highlighted occasionally—a couple here and there in BYU Studies and elsewhere. But kind of finding a register of all of the letters involved, coming up with spreadsheets of hundreds… only a fraction of those are written by women. Because the men are writing to their wives, we get a sense of what’s also in the letters that we’re missing. So it is a really phenomenal find.

Question:

Why no mention of plural marriage?

Answer:

This is before Joseph is sharing plural marriage. It’s only after this mission that Joseph includes a small number of the Twelve in his initial teachings of the practice. And then will go on through the later 1840s. Some scholars have seen this as kind of a preparatory step. For me, it’s kind of a bittersweet realization. To see how close these couples are, and then the contrast of the sacrifice of plural marriage.

Question:

How did the letters and packages get to them?

Answer:

It’s a great question. So they had something called packet ships, and this was essentially the British post office put on ships.

The one challenge for these missionaries is that they don’t usually have stable addresses—they’re moving around quite frequently. And so, in the second British mission, they set Willard Richards at kind of a stable location. That’s where all of the women write to. Then he’ll dispatch all the letters to the men as they either come see him or as he sends letters to them. So he was kind of the small post office for the missionaries.

Question:

Did I have a favorite?

Answer:

All of these couples have a different tone to their correspondence. Heber and Vilate are sometimes very melodramatic. Like that quote from Heber where he says, “You’re just the best in the world and I can’t live without you.” That’s kind of the tone of all of their letters. They’re very effusive.

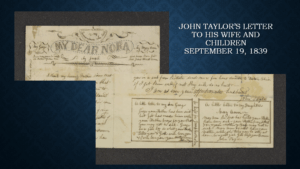

Phoebe and Wilford Woodruff are far more kind of humble. In fact, in one of her letters, Phoebe is writing from her bed—she’s bedridden in the late stages of pregnancy—and she’s very self-conscious of her writing. She says, “Don’t judge me. This is poor paper. I have a poor pen. I’m not spelling things well. I didn’t correct it.” So, kind of very self-conscious of how she’s representing herself to her husband. Who, in his letters, is cramming content in. These are two of Wilford Woodruff’s letter. You can see as he reaches the last inch that he’s just writing smaller and smaller to get everything he has to say in there.

Question:

This asks about publishing.

Answer:

I am trying to get this either on a website or published in some form. So yes, that is the plan.

Scott Gordon: It’ll be on our [FAIR] website.

Question:

In addition to encouraging my daughters to keep a meaningful journal record of their lives, what can I do to value, encourage, and celebrate female voices in the creation and sharing of Church history?

Answer:

And I would say: Come to things like this. Find avenues where you can find women’s voices. Do so in your own history or celebrate it in the history of the Church by supporting the Church History Department. Our base website, history.churchofjesuschrist.org, has a lot of these stories, and we’d like them to be more widely shared.

There’s a really great set of content called Pioneers in Every Land that is about modern pioneers, largely outside of North America. They highlight many important women there that are in South Africa or other areas of the world.

So I’d say just keep doing what you’re doing, and looking for those women’s voices.

Thank you.