Summary

Ryan Saltzgiver frames his presentation around the importance of adopting a global perspective when examining the priesthood ban and its 1978 removal. He explains that understanding this history requires moving beyond an American-centric lens to appreciate the experiences of Black Saints across Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

This talk was given at the 2020 FAIR Annual Conference on August 6, 2020.

Ryan Saltzgiver is a historian and project lead in the Church History Department’s Global Histories initiative, specializing in documenting the experiences of Latter-day Saints worldwide and exploring the global context of pivotal Church revelations.

Transcript

Ryan Saltzgiver

Without Regard for Race or Color

Presentation

Before I begin, there are a few things I think it is important to acknowledge: First, I think we must acknowledge the moment that we are in. Headlines and social media feeds are currently dominated by debates about systemic racism, its extent and consequences, and how we-–as a national and global community— should act to reverse and eradicate harmful racial attitudes and practices. While I believe that that is an important conversation, I am not here today to comment specifically about the contemporary political and social climate.

Second and lastly, I want to be clear that while I will draw on official sources and statements of the Church, I am solely responsible for the content of this presentation and this is not an official statement of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Some of what I will say today is just my opinion and I will attempt to clearly indicate when this is the case.

My hope for my remarks today is to show that the history of race within the Church is best understood when we consider the complexities of race relations globally. This perspective allows a better understanding of both the timing of the revelation in 1978 and offers insight for Church members as we attempt to move beyond past racial attitudes toward a more diverse and inclusive present.

Background

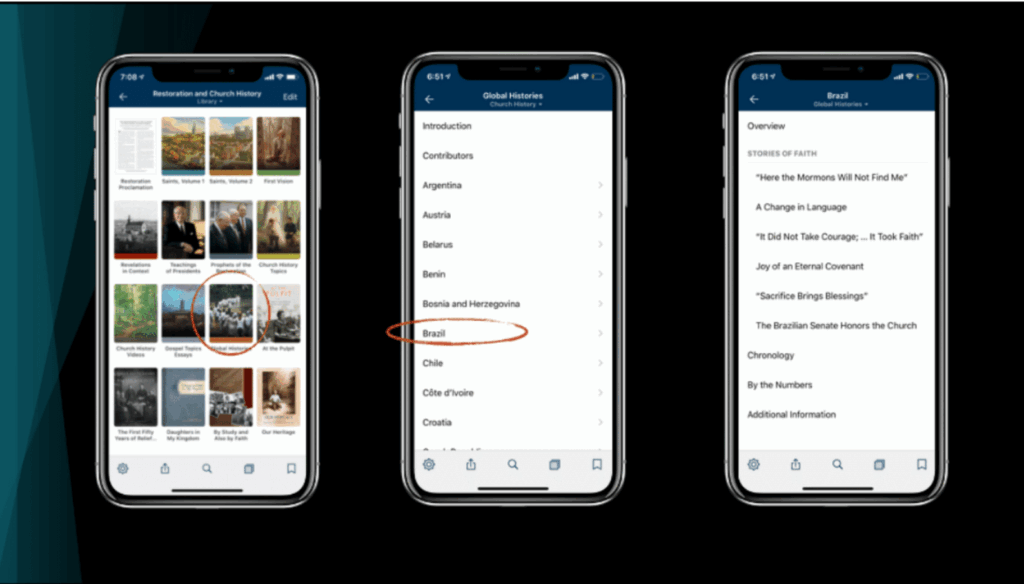

By way of background, let me provide a brief overview of my experience with the Church history department. Over the past five years, my day job has been as the project lead of the Church History Department’s Global Histories project. Global Histories are very brief histories of the Church in the countries and locales throughout the world where the Church operates. These histories include a brief overview, a selection of stories of faith, a short chronology of Church events, a ”by the number” page with demographic information of religious affiliation and Church growth in that place, and a selected bibliography.

The Stories of Faith section, which includes between one and seven stories about the Saints who have lived, worshipped, and shared the gospel in each place, are the centerpiece of these histories. In the global histories, we have attempted to adopt a local perspective—to see the Latter-day Saints from that place as they see themselves—and to share stories that are most meaningful to them.

Global Histories is now available in the Church’s mobile reading app, Gospel Library (as shown here) or online by visiting globalhistories.churchofjesuschrist.org.

While working on this project, I have been able to read and listen to the stories of thousands of Latter-day Saints, truly from “every nation, kindred, tongue, and people” (Doctrine and Covenants 77:8, among others). I have thrilled at their triumphs, shed tears at their defeats, and exulted in the universality of God’s love for all His children. His arm is truly “stretched out” to the nations (Doctrine and Covenants 136:22). In addition to providing greater awareness of the work of members generally, this has also been an opportunity to show many members that the Church is aware of their work.

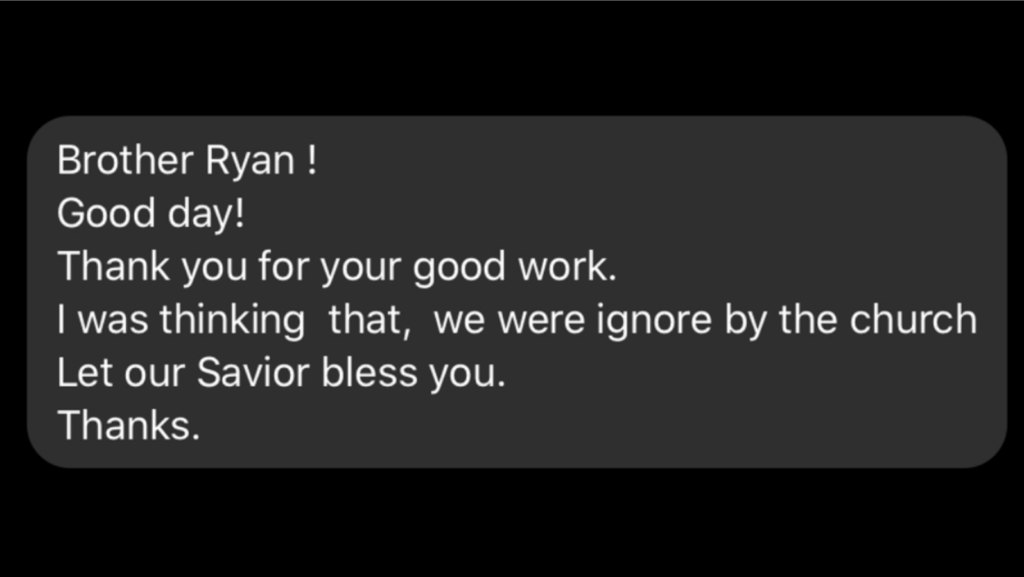

A Pioneering Member in Brazzaville

I was recently communicating with a pioneering member of the Church in Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo. Our conversation began after I found him on Facebook and sent him a private message introducing myself and the Global Histories project and asking if he had any additional personal or Church records that might help us to better understand the establishment and growth of the Church in his country. He responded enthusiastically and sent me several emails with notes, records, and photographs of early members in both Brazzaville and in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Over the course of several weeks, we continued to communicate both in email and through Facebook messenger, sharing personal details, life experiences, and testimony.

Early one morning, I awoke to a notification of a message on Facebook.

When I opened the app, this is what I found. “Brother Ryan! Good day! Thank you for your good work,” he wrote. “I was thinking that, we were ignore[d] by the church. Let our Savior bless you. Thanks.” I was struck by this message. Here was a faithful member of the Church, one of the first members and an early priesthood leader in his country, who even spent time working for the Church, and he still felt ignored.

In a global Church which continues to expand into more and more diverse places, it is crucially important that we recognize and appreciate our fellow Saints who may not look like us, sound like us, or live like us, but who has accepted the same restored gospel, made the same sacred covenants at baptism and in temples, and who are striving each day to live and share that gospel message.

Global Perspective

That brings me to my main message today: Understanding the racial history of the Church and how we can best move forward requires that we adopt a global perspective.

The prohibition of persons of African descent from holding the priesthood, participating in temple ordinances, and serving as missionaries and leaders in the Church has been the subject of considerable scholarship and discussion. Several articles, speeches, and many award-winning, thorough, and thoughtful booklength studies including those shown here have been written. In general, this scholarship focuses on historical analyses of the origins, the perpetuation (generally via racist folklore and misreadings of scriptural texts), the process for receiving the revelation ending the ban, and the status of race relations in the Church since 1978.

Scholars have convincingly established that while some Church leaders espoused and publicly declared racist ideas (most notably Orson Hyde who first posited premortal disobedience as the cause for blackness, and Brigham Young), the ban itself began in 1852 when Young asserted in the Utah Territorial Legislature that Blacks were descendants of Cain and therefore were not entitled to the priesthood. These ideas were solidified in the subsequent decades as the prohibition was further delineated and codified by Young’s successors.

By the early 20th century, the prohibition on ordination of Black men to the priesthood, denial of temple participation to all Black members, and the refusal to allow Black members to proselytize or represent the Church in any official capacity was firmly entrenched. Much of this historical context is tied directly to American racial politics.

Race in the Early Church and American Politics

For example, Young’s 1852 comments have been demonstrated—most effectively by Paul Reeve—to have been part of a national conversation on race. Reeve, in his groundbreaking book Religion of a Different Color, has argued that nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints were engaged in an often-illogical debate about their own racial purity.

“In telling the Mormon racial story,” Reeve argues, “one ultimately tells the American racial story, a chronicle fraught with cautionary tales regarding whiteness, religious freedom, and racial genesis.” Five years ago, during the 2015 FairMormon Conference, Reeve in fact argued that throughout the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Church members were “attempting to claim a white and pure future” while others were “attempting to trap [them] in a racially suspect past.”

This contest over Mormon whiteness, Reeve argues, led Young and others to abandon the racially inclusive attitudes found in Latter-day Saints scripture and encouraged by many early Church leaders (including Joseph Smith and Brigham Young). Perhaps no verse is more unequivocal on this point of inclusivity in Book of Mormon than 2 Nephi 26:30 in which Nephi declares “He [the Lord] inviteth all unto him and partake of his goodness; and he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile.”

Preaching in Africa

Similar inclusion is evident in Joseph Smith’s revelations. For just one example, the 1 November 1831 revelation now canonized as Section 1 of the Doctrine and Covenants, calls on the people “from afar” and “upon the islands of the sea” to hear the restored gospel. Joseph Smith’s call of missionaries to Europe, the Islands of the Pacific, Jamaica, and other foreign lands indicates his early understanding of a global ambition for the Church. Several evidences exist that early Latter-day Saints understood that the Lord expected them to preach to Africans.

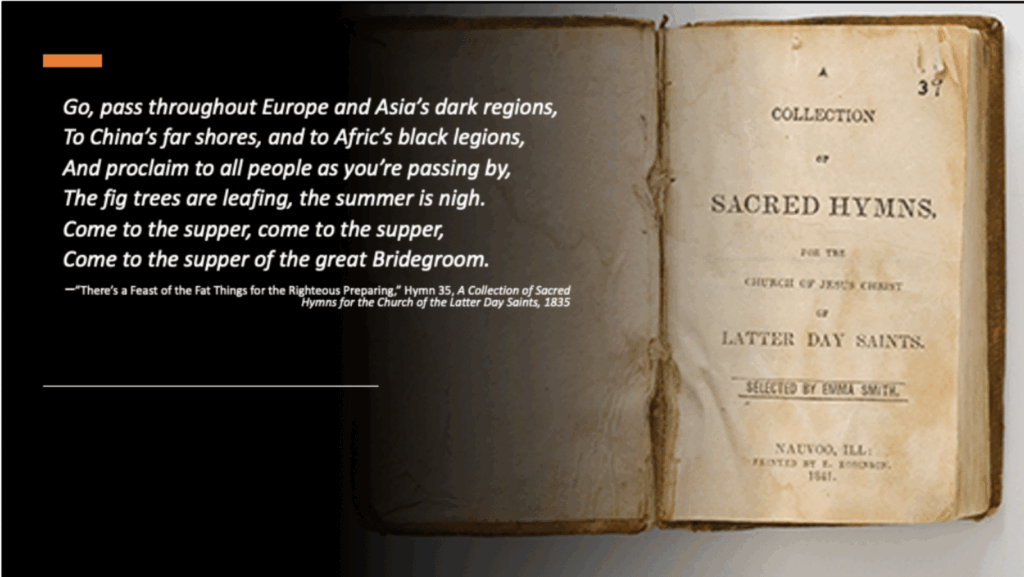

This idea is even found in early hymns. For example, the fourth verse of the hymn “There’s a Feast of the Fat Things the Righteous Preparing,” written by W. W. Phelps and included in Emma Smith’s first Latter-day Saint hymnal, unambiguously calls for Saints to “Go, pass throughout Europe and Asia’s dark regions, To China’s far shore, and to Afric’s black legions.”

This Hymn, later called “Come to the Supper,” appeared in all Latter-day Saint hymnals until 1912, although this verse (and the fifth) were omitted sometime around 1886.

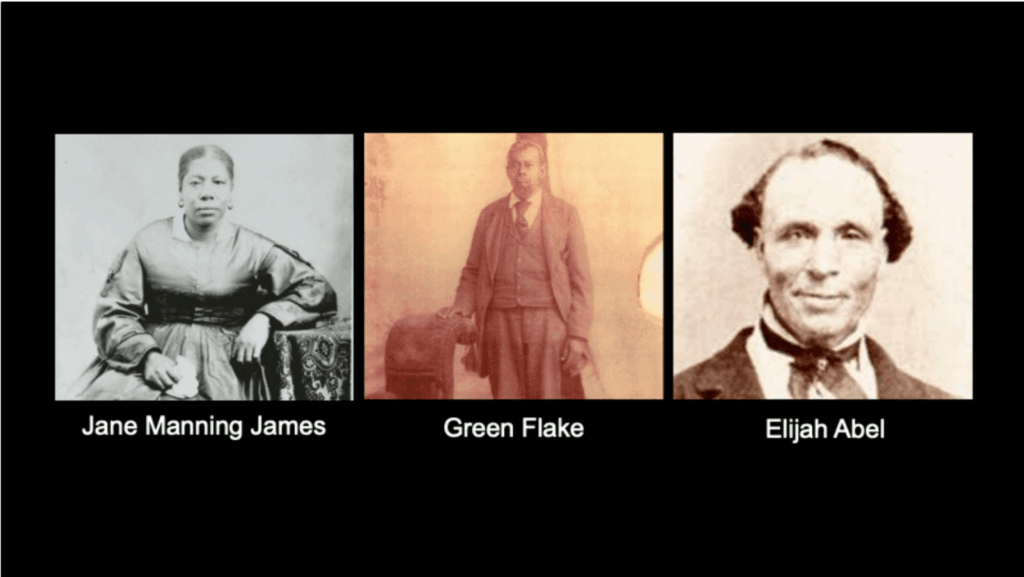

And perhaps no greater evidence of early inclusivity in the Church can be found than in the lives of early Black Saints who continued stalwart even as they endured increasingly exclusionary racial policies in the Church. Their struggle for and eventual loss of full inclusion in the Church was a process that began in direct response to contemporary America political pressures.

Seeking Revelation

With a few notable exceptions, however, much of the scholarship likewise places the end of the ban in the context of American racial politics, particularly the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s and an attendant increase in racial consciousness among Americans in the 1970s. In their introduction to Black and Mormon, editors Newell G. Bringhurst and Darron T. Smith asserted that African American Latter-day Saints were “those individuals most directly affected” by both the ban and its end, despite later citing statistics of Church growth in Black communities which are overwhelming “in sub-Saharan Africa, Brazil, and throughout other parts of Latin America.”

I certainly do not think that the political environment surrounding Church leaders in Salt Lake City—which included protests at Church headquarters and against Church-sponsored sports teams at BYU—made no impact on their thinking. There is clear evidence, in fact, that the racial views of Church members—who were still predominantly American—were taken into account as Church leaders prayerfully considered the ban.

I argue, however, that it was encounters with Black Latter-day Saints (both baptized and unbaptized) particularly but not exclusively abroad coupled with the increasing impossibility of establishing a functional Church structure globally which had the most profound impact on their racial notions and sparked their desire to seek the revelation which ultimately ended explicitly exclusionary racial practices.

Increasing International Encounters and the Ban

There is clear evidence that this was the case in the first paragraphs of the widely-distributed 8 June 1978 letter announcing the revelation ending the ban.

The First Presidency stated that

As we have witnessed the expansion of the work of the Lord over the earth, we have been grateful that people of many nations have responded to the message of the restored gospel, and have joined the Church in ever-increasing numbers. This, in turn, has inspired us with a desire to extend to every worthy member of the Church all of the privileges and blessings which the gospel affords.”

Two Church leaders—David O. McKay and Spencer W. Kimball—stand out as examples of the impact contact with diverse Church membership had on the changes in their racial attitudes.

For example, in 1921, while in Japan on the first leg on his year-long global tour, McKay experienced ”profound culture shock” (Reid L. Neilson, “Turning the Key that Unlocked the Door: Elder David O. McKay’s 1921 Apostolic Dedication of the Chinese Realm,” Mormon Historical Studies 10, no. 2 [Fall 2009], 86). He later said he “felt as though he was standing on his head” as he observed cultural practiced that felt strange.

After one lunch appointment where he inadvertently offended his gracious host, McKay determined to approach his encounters with other cultures with more empathy. “Right from that moment on I said, I am going to try to see things here in Japan from the Japanese standpoint, and it is wonderful how things changed.” This lesson impacted the remainder of McKay’s life and ministry as an apostle and eventually as Church president (see Gregory Prince and Wm. Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism [Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005], 371).

Travelling Outside the U.S.

As Church president, he undertook several key initiatives to encourage greater participation among Latter-day Saint converts throughout the world. These initiatives included concerted efforts to meet with foreign dignitaries and accept interview requests from the press to improve the Church’s international image, an emphasis on members remaining in their homelands rather than moving to the United States, the establishment of the first stakes and the dedication of temples outside the United States.

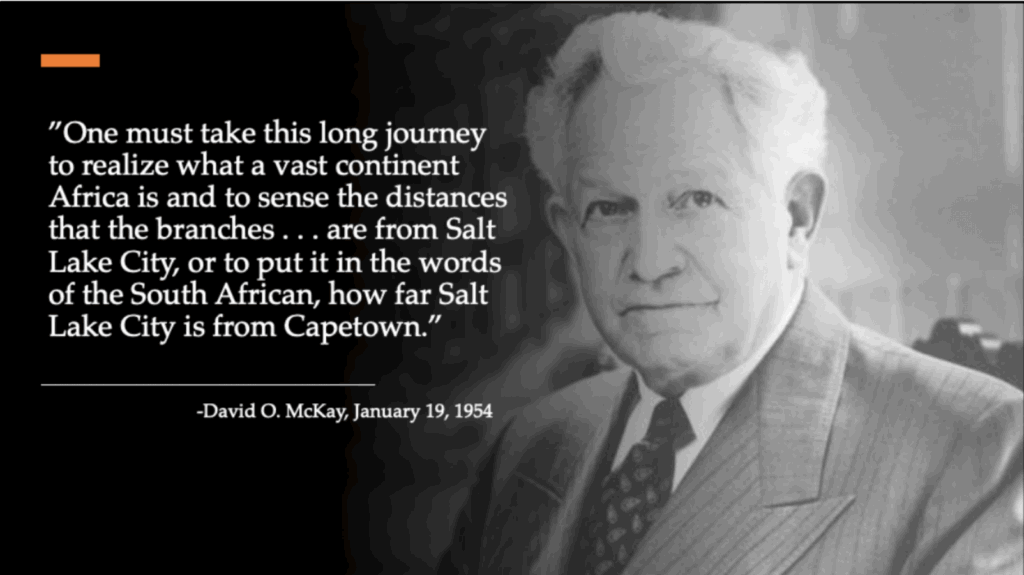

In 1954, while traveling in Latin America and South Africa, McKay was again impressed with the greater understanding that is afforded Church leaders when visiting members in their homelands. In a letter written while in South Africa, McKay reflected that “One must take this long journey to realize what a vast continent Africa is and to sense the distances that the branches . . . are from Salt Lake City, or,” he added, hearkening back to his lesson three decades earlier in Japan, “to put it in the words of the South African, how far Salt Lake City is from Capetown,” (as quoted in Prince and Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, 373).

After returning to Salt Lake City, McKay told his counselors and the Twelve that “The concepts that we get from reality are entirely different than the concepts we have from reports.” He soon insisted that General Authorities, particularly Apostles, make regular visits to Church members outside the United States.

That same year, McKay appointed a special committee of the Quorum of the Twelve to “study the issue” of the priesthood ban. They concluded that there was “no clear basis in scripture but that the Church members were not prepared for change” (Edward L. Kimball, ”Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood.,” BYU Studies 47, no. 2 (2008), 19).

Fernandez

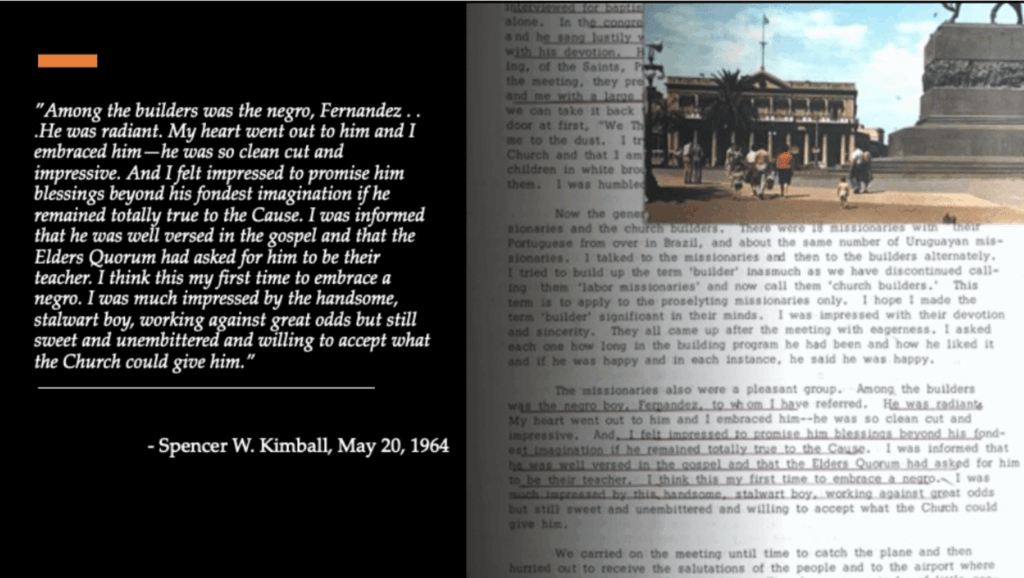

Spencer W. Kimball, who was a member of the Twelve at the time, immediately began to make regular visits to members throughout Latin America. During his travels, he frequently encountered faithful Black members of the Church and was impressed by their dedication. While traveling in Uruguay in 1964, Kimball and his traveling companions stopped at a meetinghouse construction site where ”Church builders,” local members who were called as missionaries specifically to build meetinghouses, were working.

Throughout the day, a young Black member named Fernandez drew Kimball’s attention.

He was radiant,” Kimball recorded in his journal. “My heart went out to him and I embraced him—he was so clean cut and impressive. And I felt impressed to promise him blessings beyond his fondest imagination if he remained totally true to the Cause.

I was informed that he was well versed in the gospel and that the Elders Quorum had asked for him to be their teacher. I think this my first time to embrace a negro. I was much impressed by the handsome, stalwart boy, working against great odds but still sweet and unembittered and willing to accept what the Church could give him.”

The Complexity of Determining Ancestry

In addition to these types of heartbreaking experiences, leaders also dealt with the increasing complexity of determining ancestry in communities throughout Latin America and the Caribbean where large African and mixed-race communities existed.

As the apostles began to make more regular visits to members globally, as many members of the Church today know, letters from interested people throughout Africa were being received at Church headquarters (see James B. Allen Would-Be Saints: West Africa Before the 1978 Priesthood Revelation, Journal of Mormon History 17, no. 1 [1991], 207–247, and the Global Histories for Ghana and Nigeria). As early as 1946, Africans who had learned about the Church in a variety of ways, wrote a steady stream of letters to Church Headquarters.

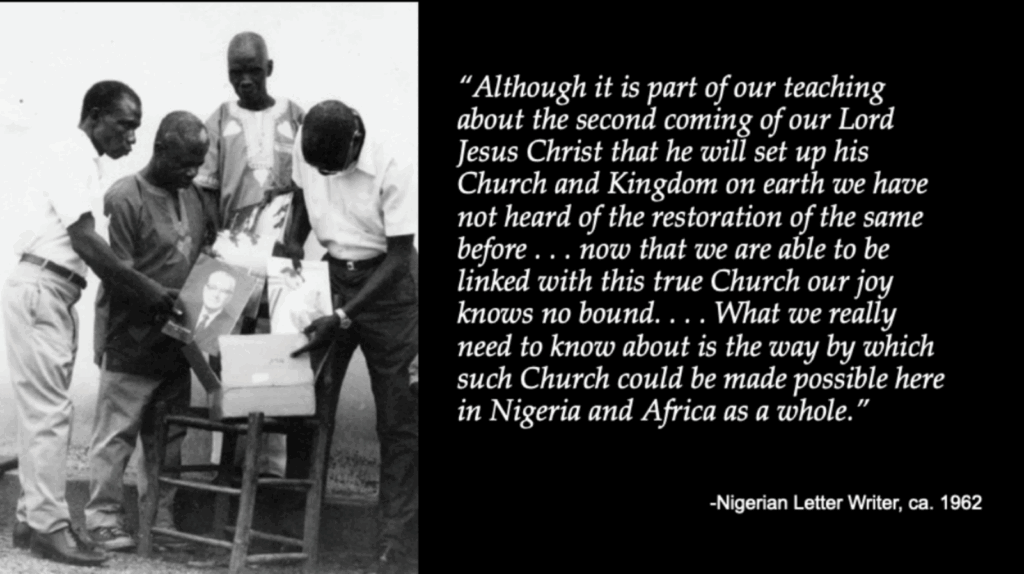

Lamar Williams, an employee in the Church’s Missionary Department, was given the task of reading and responding to these letters. While he was specifically directed to make it clear that the Church had no foreseeable plans to establish itself in predominantly black nations, Williams was given latitude to maintain correspondence. Williams collected the overrun materials from the Church’s printing operations and distributed them to a regular group of correspondents in Nigeria and Ghana.

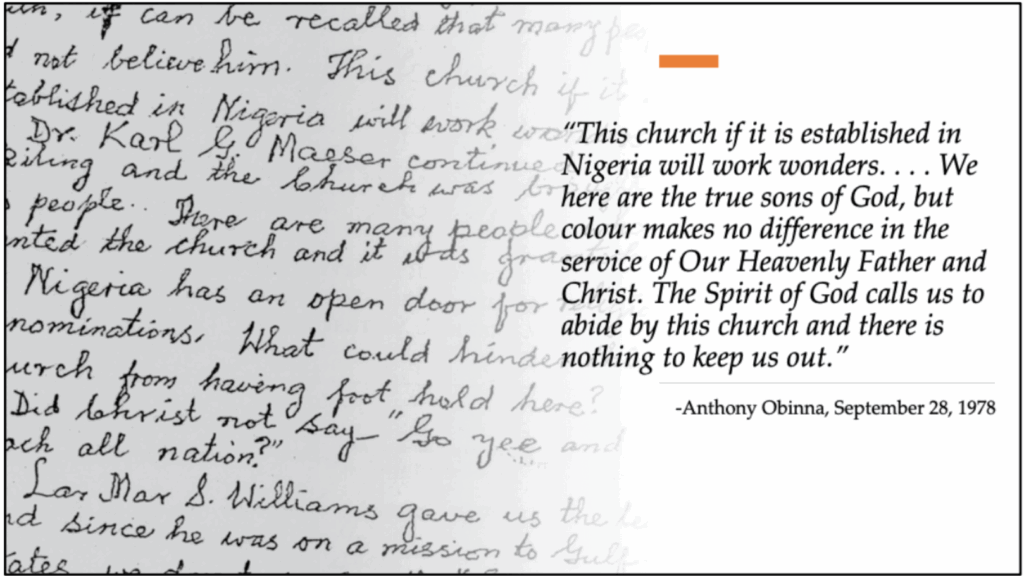

Many of the letters are similar to this excerpt here, which I will allow you to read for yourselves, and frequently professed the writer’s faith in the truthfulness of the restoration, testified of Joseph Smith’s divine call as a prophet, and of the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon. Many also report large groups of believers meeting regularly and most asked for additional Church materials—including scriptures, teaching manuals and tracts—be sent, and several asked how they could assist in facilitating the establishment of the Church in their homelands.

Letter Writing

These letters demonstrate that the materials Williams sent were well-used and thoroughly studied. Many were aware of the ban, but articulately asserted that there was no evidence that it was supported by scripture, particularly by Latter-day revelation.

Williams’ ongoing correspondence with West Africans eventually led to a series of meetings in February and March 1962, in which President McKay outlined the establishment of a mission, with Williams as president, that could organize of the “auxiliary organizations of the Church . . . among the existing groups” in Nigeria, but that no formal branch organizations would be established (Allen, 214).

After learning of the ban and the racial folklores commonly used to defend it, Nigerian officials, however, refused to grant visas. After Williams made several unsuccessful attempts to obtain government permission, plans for the mission were abandoned shortly before the outbreak of Nigerian-Biafran War, a civil war that engulfed the country for more than two years during the latter part of the 1960s.

Requests for baptism from unbaptized black converts in Africa continued to pour into the offices of the International Mission throughout the 1960s and 1970s, while members in Latin America and the Caribbean were joining in increasing numbers.

Anthony Obinna, who learned about the Church through a dream and a Reader’s Digest article he read while avoiding the conflict of the Nigerian Biafran War. Obinna was soon writing regular letters to Lamar Williams and reported more than 100 converts regularly attending meetings he conducted. Like so many others, Obinna continued faithfully writing letters, studying the gospel, and praying for the day when he too would be able to hold the priesthood.

Enforcement of the Ban

In addition to the disappointing visa negotiations with Nigerian officials which were scuttled by the racial policies and folklore, Church leaders found the ”one drop” policy—the idea that anyone with “one drop” of African blood was subject to the ban—increasingly cumbersome to enforce.

As my colleagues Jeremy Talmage and Clinton Christensen have shown, in places where no law or settled customs existed for determining an individual’s race (i.e., Jim Crow laws in the United States or the Apartheid system in South Africa) “leaders had to rely on their own interpretations” (Jeremy Talmage and Clinton D. Christensen, “Black, White, or Brown? Racial Perceptions and the Priesthood Policy in Latin America,” Journal of Mormon History 44, no. 1 [January 2018], 139).

Latin America and the Caribbean nations, where large portions of the population are descended from African slaves, presented particular challenges for these determinations. Assessments of race were wildly inconsistent, frequently relied on the racial perceptions and biases of missionaries or local leaders, often required difficult and costly investigations, and occasionally required the intervention of members of the Twelve.

When preaching first began in Brazil in the 1930s, missionaries were directed to “ask where someone else lived” if a person who appeared to be black answered the door while they were tracting. In other areas—such as Esmeraldas, Ecuador, where the population is 80% African—mission leaders delayed sending missionaries to simply avoid the potential problems.

Inspiring and Heartbreaking

Occasionally, accusations of mixed-racial heritage were a point of division and contention in small branches. In San Pedro Sula, Honduras, for example, shortly before the son of one branch president was to receive the Aaronic Priesthood, the missionaries accused his mother of being black. The district leader feared that the unresolved question of her ethnicity might “unravel the leadership of other branches throughout the country.” In response, he took two long bus trips, including one to Juticalpa, a small village 110 miles away in an area where bandits had recently highjacked a bus and murdered all its passengers, to determine that her parents were “Indigenous” and “Italian.”

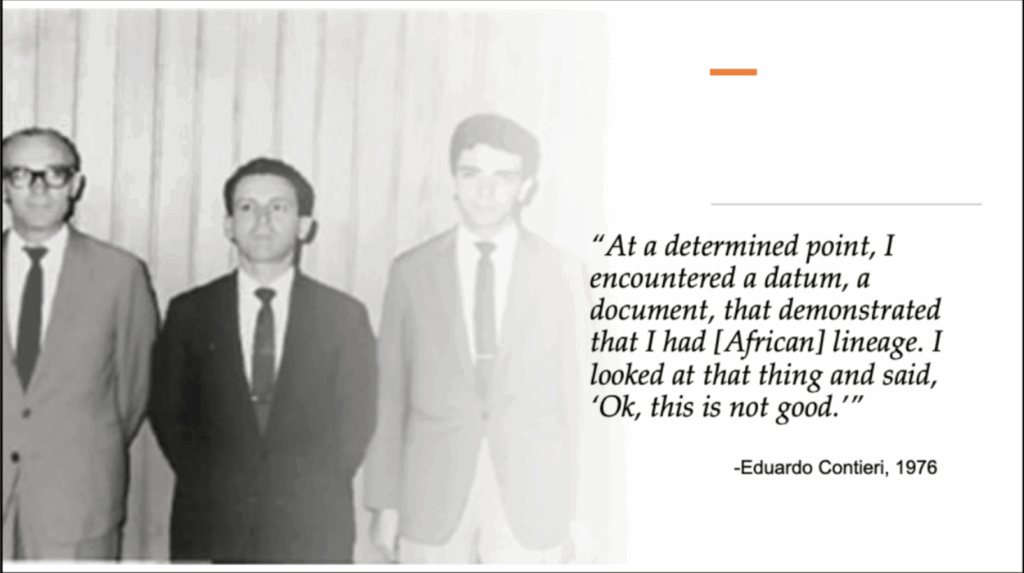

Occasionally, the stories of recent converts valiant attempts to conform to the policy, even at great personal sacrifice, are equal parts inspiring and heartbreaking. That is the case with Eduardo Contieri of São Paulo, Brazil. Shortly after joining the Church, Contieri received a priesthood blessing from the missionaries and was miraculously healed of injuries that he had suffered in a serious car accident.

Soon after, he was called as president of the São Paulo Ipiranga Branch. As he and his counselors reviewed the status of the branch, they determined that the one area where members could make better progress was in doing genealogical research. Contieri, wanting to be an example to the members in his branch, began researching his own family.

Contierie’s Lineage

“At a determined point, I encountered a datum, a document, that demonstrated that I had [African] lineage. I looked at that thing and said, ‘Ok, this is not good.’” Contieri had discovered a picture of a maternal grandmother who he had never known. The woman in the picture appeared black to Contieri.

“Naturally I understood that I had [African] lineage . . . and in my heart I sensed that force of the gospel that I had embraced and in that moment I felt the most blessed of men for if I remained faithful until the end, especially if the priesthood I had received remained, one day, at some time, I could use it and be counted as the seed of Abraham,” Contieri said later.

Although heartbroken, Contieri felt that this was a moment of personal revelation which “filled [him] with happiness.” He immediately reported his discovery to the mission president. Contieri was told that he should not use his priesthood to perform any public rituals and he would be released from his position as branch president, but he was allowed to continue to use the priesthood in private to bless his family.

While the years that followed were difficult for Contieri, he remained faithful, even paying for a young man in the branch to serve a mission. In 1966, when Spencer W. Kimball organized the São Paulo Brazil Stake, he became acquainted with Contieri.

The Nugents

”Brother Contieri’s story is interesting and faith promoting and heart breaking as are most of the others,” Kimball wrote in a letter to Elder Gordon B. Hinckley in 1969. In 1971, the First Presidency reviewed Contieri’s case, determined that the evidence of his blackness was insufficient and lifted the suspension of his priesthood in public. In 1973, five years before the priesthood ban was lifted, Eduardo Contieri, a Latter-day Saint who self-identified as of African lineage, accepted the call to serve as bishop in the São Paulo I Ward.

While the issues of determining and enforcing the racial policy among mixed race people are heartbreaking, the stories of Saints who were unquestionably barred by the policy and yet reconciled themselves to the prohibition are inspiring.

Vincent and Verna Nugent were first introduced to the Church in Jamaica in 1973 after a coworker saw Victor reading his bible during his breaks. His coworker, Paul Schmeil, came to the Nugent’s home and shared several Church videos, the Book of Mormon, and taught the family several principles of the restored gospel. Near the end of the evening, Schmiel explained that, because of their African heritage, Victor would not be allowed to hold the priesthood and the family could not go to the temple. “My ego was hurt, but I had a strong feeling that the message was the truth,” Victor later recalled, “and more was involved than pride and vanity.”

Painful Aspects

Drawing on his study of the bible, Victor began to reconcile himself to the ban. “I had been reading the bible so intensely that I honestly knew many things that many other people probably didn’t,” he explained later. ”I understood that the priesthood is not something you gain by study or by buying it . . . I also understood that it was not the proper thing to covet priesthood authority, because the priesthood is the power and authority of God. He’s the one who decides who has or who should exercise the priesthood or who should not. . . . I went and I prayed about it, and I got a good feeling.” After several more months of lessons from Schmiel, Victor, Verna, and their oldest son, Peter, were baptized.

Despite the confirmation that he received that night, there remained aspects of the ban that were painful. In 1975, Victor and Verna traveled to Salt Lake City for the first time where they toured Temple Square. During their visit, they walked around the temple and marveled at the sacred feeling that they felt there.

“I remember walking up to the temple and putting my hand out and touching . . . the granite wall,” Victor recalled in 2012. “[And] saying, ’I’ll never get into this building. I’ll never get inside the temple, but I can stand here and I can touch this holy building.’”

Those familiar with the story of Helvecio and Ruda Martins and their family will hear a similar echo in the story of Victor and Verna Nugent I just shared.

Remain Faithful

Helvécio and Rudá, both of African descent, pointedly asked the missionaries in their home in 1972, “How does your religion treat blacks?” Concerned how the family would react to the Church’s restriction, the missionaries asked to pray with them first.

They then explained to the best of their ability the Church’s teachings on priesthood and the temple. “The missionaries’ explanations seemed clear to me,” Helvécio said later. He remembered the “calmness, serenity, and happiness” that entered their home. The couple was soon baptized.

By 1975, Helvecio was working as a spokesperson for the Church in Brazil when the São Paulo Temple was announced. Helvécio traveled the country, explaining its significance to others. When the cornerstone of the temple was laid, President Spencer W. Kimball spoke to Helvécio privately. “Remain faithful,” Kimball encouraged, “and you will enjoy all the blessings of the gospel.”

During construction of the temple, Helvecio and Ruda were able to walk inside the foundation of the building. While standing in the area where the celestial room would one day stand, they had a powerful witness that they would enjoy the blessings of the temple at some point in the future. “We were overcome by the Spirit. We held each other and wept.”

The revelation that was received June 1, 1978 and announced to the world a week later was the product of years of study and prayer for President Spencer W. Kimball. I encourage you to read Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood by his son Edward published in BYU Studies in 2008. The “long promised day” was a moment of celebration for members all over the world, of all races.

Lifting the Ban

Within days of the announcement countless Black members were ordained and began making preparations to attend the temple. In June 1978, Victor Nugent, Helvecio Martins (and his son Marcus) were ordained to the priesthood. That fall, both families were sealed in the temple.

This letter, written in late-September 1978, it is interesting to note that none of the Church leaders who were currently writing to Obinna, despite several letters and visits to the country since June 1978, had not yet informed Obinna of the revelation and the change in policy. In November 1978, when missionaries did come to Nigeria, Anthony Obinna was the first to be baptized. He was ordained the same day and set apart as the first branch president in the country.

While the revelation on the priesthood ended the ban and Church leaders have “disavow[ed] the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse, or that it reflects unrighteous actions in a premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else,” certain racial attitudes continue to exist and the priesthood ban, as a part of our shared history, is something that Latter-day Saints must continue to reconcile themselves to.

Elder Sitati

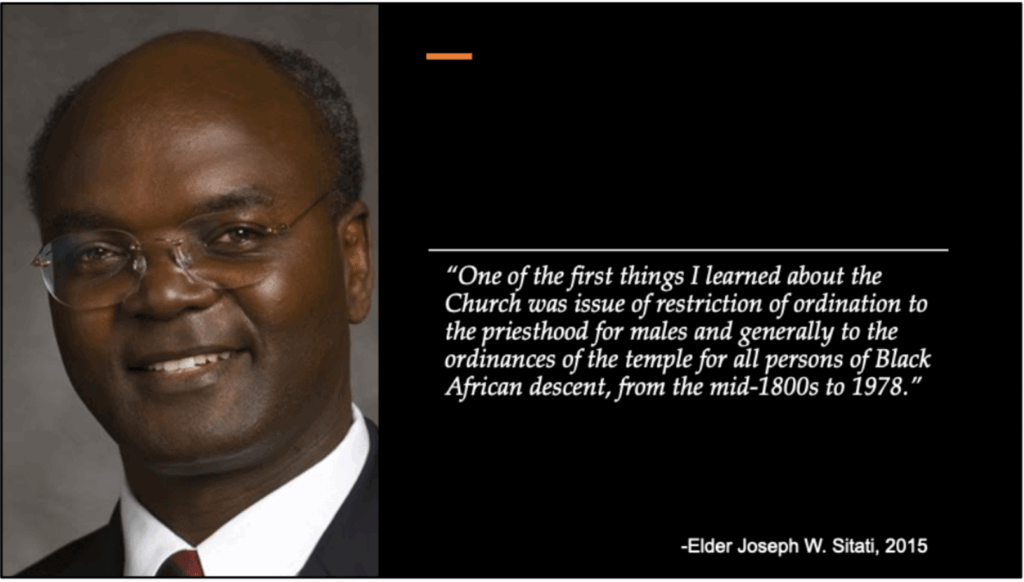

Looking to the examples of Black members who have confronted this topic is, I believe, particularly helpful. In 2015, speaking at the “Black, White, and Mormon,” Conference at the University of Utah, Elder Joseph W. Sitati who joined the Church in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1986, shared his own experience on reconciling the ban.

Although the ban was lifted 8 years earlier, Elder Sitati has said,

One of the first things I learned about the Church was issue of restriction of ordination to the priesthood for males and generally to the ordinances of the temple for all persons of Black African descent, from the mid-1800s to 1978.”

The sense of peace that Elder Sitati and his wife, Gladys, felt when attending church meetings, however, encouraged him to continue to study the issue.

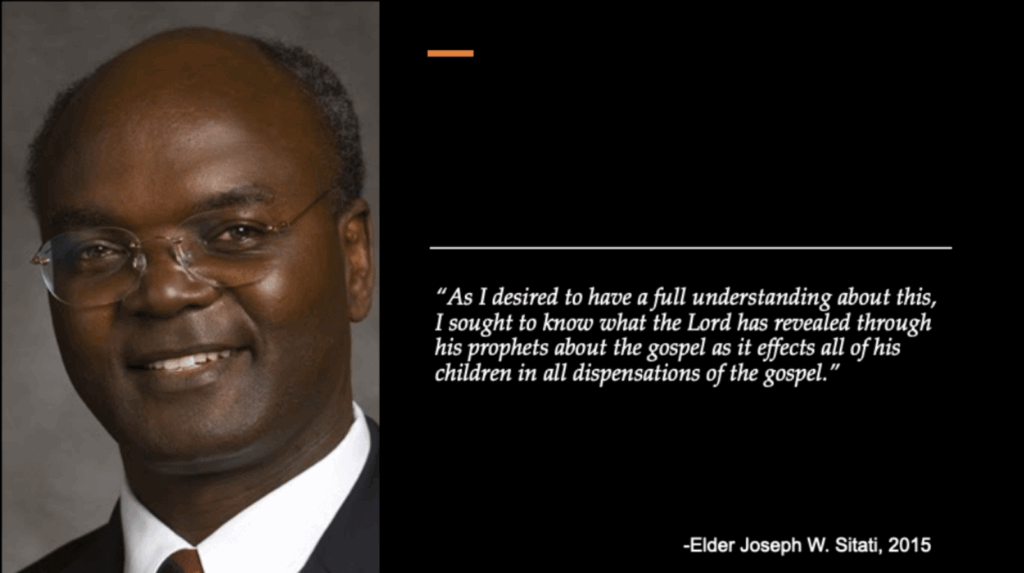

As I desired to have a full understanding about this, I sought to know what the Lord has revealed through his prophets about the gospel as it affects all of his children in all dispensations of the gospel.”

Similar to the experience of Victor Nugent, as Elder Sitati studied the scriptures, he came to the profound truths contained in the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants that I referenced at the beginning of my presentation.

All people are alike unto God and He ‘inviteth all men to come unto him,’” Elder Sitati said.

“The apostles that Christ chose to lead his early Church did not, at first, fully understand [the universal nature of the gospel] due to the prevailing worldview which was shaped by the law of Moses. As they were considering how to take the gospel from the Jews to the Gentiles according to the commandment given to them by the resurrected Christ, Peter resisted this direction in the vision in which the Lord offered him all manner of beasts and bid him to kill and eat.”

Understanding Discriminatory Practice in Our Time

Drawing on the existence of individual and collective racial prejudice found in scripture, Elder Sitati provides a useful heuristic for understanding discriminatory practices as they are found in our own time. Peter’s experience with initially rejecting God’s vision and his subsequent realization that “of a truth, God is no respecter of persons,” becomes a model for understand contemporary historical events when God, and more often God’s people have initially balked at heavenly direction that all men everywhere are the children of God entitled to the blessings of the gospel.

Since 1978, more than half a million members have joined the Church in Africa and significant growth has occurred in Black and Mixed-race communities in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Most active African Saints who have joined the Church since [1978],” Elder Sitati observed, “know that this is a reality of the past and have found individual answers in the restored gospel of the plan of happiness that give them understanding and peace regarding the unfolding events of the gathering of the Saints in these last days. Those who have found answers, choose to look forward to the future, with faith and assurance that all things are before the Eternal Father.”

Elder Sitati placed the revelation and the responses of converts throughout Africa since 1978 in the context of African Nationalist movements of the 1950s and 1960s which did away with colonialism and created many of the independent African states that exist today.

In some respects, the restriction of the priesthood is viewed by Africans in the same way as the practices of the time that defined the colonial, social, and cultural hierarchy,” Elder Sitati asserted. “This included the practices of long-established, foreign-based Christian churches in Africa during that time. . . . The Church is not perceived as American, white, or racist anymore than other churches originating from the United States.”

Conclusion

The analysis of the 1978 priesthood revelation in the context of American political history, as much of the literature on the topic has done, ignores the majority of Black Mormon experiences. Indeed, in an American context, the timing of the revelation feels like a delayed response that was at best a decade late.

It is clear from the records of Church leaders during the 1960s and 1970s, that their encounters with Black Saints, primarily but not exclusively in countries outside the United States, prompted much of their reflection on race issues. By reading and sharing the stories of Black Saints from around the world, we are all better able to find the peace and assurance that Elder Sitati spoke of and to look to the future of the Church fully inclusive of ”every nation, kindred, tongue, and people.”

Thank you.

Audience Q&A

Scott Gordon:

Thank you for your timely and interesting presentation. I really appreciate it, thank you. I’m going to start with a theological and not historical question, probably the most difficult question, I think. So, we claim to be led by prophets of God and apostles, and yet some of these practices of racism and things seem to have been at least followed by these Church leaders. How do we reconcile that?

Ryan:

I think the best way to reconcile that is to—I’m going to use the word disabuse because I think it’s the most appropriate here—disabuse ourselves of the notion that because someone is called of God, they no longer have any human frailties, that they are now infallible. It is certainly true that we are influenced all the time by the things that are happening around us, the pressures that are put on us by daily life, by politics, by just the encounters that we have with people. I think, just like Elder Sitati pointed to Peter’s reticence about going to the “unclean things of the world,” a worldview that was shaped by the law of Moses and by other things that he had experienced, latter-day prophets, apostles, and Church leaders were also shaped by prejudices that they encountered in their own cultures and which the gospel is intended to eradicate from us. You know, Mosiah 3 tells us that the natural man is an enemy to God, and I think that means we’re also enemies to God’s children until we put off those things through the atonement of Christ and become more fully inclusive and welcoming of God’s children and empathetic to them.

Scott:

That’s very good. So, here’s my first question from the audience: COVID-19 has caused the Church to limit mission calls to members’ home countries. Do you think this will be a long-lasting change, and how do you think this cultural isolation among young missionaries will affect racial attitudes in the Church?

Ryan:

There are two thoughts that I have there. First, I hope that that’s not a permanent thing. I really think that it is encounters with others, you know, to use the social science theory here, that the encounter with the other is the way that we’re able to overcome our racial prejudice. So, I hope that we are only doing this temporarily as an expediency to fight this pandemic. But there is also the call to allow people to hear the gospel in their own way and to preach to their own people. So, I think it’s a balance that I hope we can strike between allowing Church members the opportunity to interact with one another in Church settings, on missions, and in other ways, but also to allow people to hear the gospel in their own tongue.

Scott:

This is a follow-up, I think, to the same question: Our immediate Church communities are local in nature—wards, stakes, etc. Can you think of new ways that the Church can facilitate members building bridges and relationships with the global community of Saints?

Ryan:

I think that’s the million-dollar question when it comes to the globalization of the Church: How can we foster better relationships amongst people of diverse backgrounds and locales? That is, in part, the goal of Global Histories and other projects like it, including “Saints,” which is the four-volume history that we’re currently working on, which is an attempt to encourage people to understand the universal nature of God’s message, to see each other as Saints.

The other thing is the possibility of sharing those stories as we publish them in our meetings, in our Sunday School lessons, in our Primary lessons, and in those types of settings, is always the first step. Aside from that, greater inclusion in general conferences and other settings would be one place where I would love to see more members of diverse backgrounds having that opportunity. I think we saw an example of that in the last general conference with youth speakers who came and spoke, and continuing to increase those types of opportunities, I think, would be wonderful.

Scott:

I’m really grateful for the things in “Saints” and some of the things that are happening, as you say. I remember when we started working with FAIR originally, and as I learned more about the Black Saints in our history, I realized— forgive the expression—but we pretty much white washed it and forgot about them. So, it’s nice to see those stories coming forward again and being talked about. So, what type of multicultural orientation do current general authorities and officers receive when they visit or are called to serve long-term in areas that they are culturally unexposed to or unfamiliar with?

Ryan:

Unfortunately, I think the only answer I can give to that is, I don’t know. I’m not privy to what kind of training they’re given. I hope that it’s extensive, but I have no idea.

Scott:

What official explanation is given to Black converts as to why there ever was a priesthood ban for Blacks?

Ryan:

The current official position of the Church is, we don’t know. That’s the position that President Hinckley began using in the early 2000s as this became a common theme in the interviews he was taking with the press, that we really don’t know. We can talk about places where we first start seeing it, but actual reasons or justifications or assumptions are all just that—reasons, justifications, and assumptions.

Scott:

How would you respond to persons who try to create a parallel between the end of the ban on race and an imagined future change of the law of chastity and temple covenants to embrace same-sex marriage?

Ryan:

That is a topic where—and, you know, we see this frequently—I think that if that change is imminent, it would happen in the exact same way, where it would be the matter of careful study, prayer, and revelation that seeks complete unanimity within the Quorum. I’m not sure that that is something that is coming in the future, and my faith is that if it is intended to happen, then God will do it in His time, and if it’s not, then it won’t.

Scott:

Okay, so here’s kind of a heartfelt question: Did Brigham Young actually say before the legislature on slavery what is attributed to him? Is there any way to know? I’m a mother of five Black children, and this is important to us.

Ryan:

We do have fairly substantial records of those meetings in early 1852—I believe it was January 5th. We have an 800-word account of that meeting, a summary of what Brigham Young said, written by Wilford Woodruff, and then we have a shorthand transcript of that speech that was taken by George Watt, which has recently been translated by LaJean Carruth from our department. So, we do have fairly good records.

The interesting thing about that meeting is to compare his comments to those of Orson Pratt in the same setting, who very adamantly denied this racial idea, fought against it, and did not want it to happen. In fact, this public debate he had with Brigham Young eventually led to Brigham Young censuring him, but there’s some very difficult things that are said in that setting, and we do have good records of it.

Scott:

I appreciate that. So, just to repeat, there were members of the Church and leaders in the Church who were very opposed to the Church’s position or the Church’s policy on race?

Ryan:

Absolutely, absolutely. So, unlike when the revelation was received in June of 1978, where unanimity existed amongst the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve who were in that setting—all of them—even those who had publicly made statements that were racist, disavowed those statements. Bruce R. McConkie, for example, said, “We have further light and knowledge now, so anything we said before June of 1978 is no longer true.” That unanimity did not exist in the Quorum in 1852. Brigham Young, I wouldn’t say was unilateral in it, but he was the leading voice in announcing a policy in a ban on Black members, while other members of the Quorum, including both Pratt brothers, were against it.

Scott:

Interesting. Why do you think Church leaders were not more influenced by African Americans?

Ryan:

I wouldn’t say that they weren’t influenced by African Americans. I think the Genesis Group protests that were happening in the United States and other things were definitely part of their thinking, but I do think that the experiences and encounters that they had with Black members outside of the United States, in political contexts where they wouldn’t have understood possibly the local politics, were more impactful on them. I think that was just a heightened sense of the difference that was around them.

Scott:

We often hear that the Black ban on priesthood has no basis in scripture, but the Book of Abraham certainly references such a ban. While we rejoice in the 1978 revelation, why do we ignore this reference in scripture?

Ryan:

This is referring to Canaan and that Pharaoh was of the lineage which had no right to the priesthood. So, there are instances of localized bans—groups that don’t have the ability to hold the priesthood—at various times throughout the scriptures. This is one instance in Abraham. Likewise, in ancient Israel, only the Levites could hold the priesthood, and the high priests could only be the oldest sons of descendants of Aaron. So, there are these other instances. Elder Sitati does talk about those things as part of his scriptural heuristic for looking at these things. And whether or not those are things that are imposed by God or other things, we’re not clear on.

Abraham, certainly in the Book of Abraham, the reference here does not give us a particular reason why he would be prohibited from having the priesthood, except that it has something to do with his ethnicity. It doesn’t, for example, tie it to Ham or to Cain or to any other folklores that are existing at the time, though obviously Pharaoh is a descendant of Ham, and so the supposition is easily and understandably made.

Scott:

I guess so. I don’t want to speculate too much here, but the existence of limitations on priesthood ordination is found in the scriptures, but very rarely are reasons given. More often, God is inviting all to come unto Him; He’s extending revelations to His prophets and leaders, which are inviting all His children to accept and enjoy the full blessings of the gospel.

So, maybe one more question—I know there’s a few more I’m not able to get to because of time, and I apologize to those who sent them in. What should we do now as members of the Church? I mean, we continue to have more members of African-American or African descent join the Church. We continue to also have areas that are mostly white, and we have isolated members in congregations who sometimes feel unwelcome. So, what should we do?

Ryan:

I think open communication. I think we need to have the opportunity to sit down with one another and to learn more about each other. I was recently watching a documentary where they brought in a group of people who were from a variety of racial backgrounds and racial opinions, and there were two people—one who was of African descent and one who was a fairly conservative white person—and they just had them have a conversation. They put a bowl of questions in front of them, and there were things like, “Tell me about your family,” and they found out that both of them were the children of divorce, that they had gone to similar schools, they had similar interests in movies and music. And as they learned more about each other on a personal level, they were able to empathize better with one another and to look beyond some of the racial attitudes that they may have had before—going both directions.

I think in the gospel, we have the added benefit as members of the Church of being able to connect on the level of testimony and of the Spirit, which has testified to all of our hearts. Sharing those experiences where the Lord has touched us, where the Spirit has come and testified to us, is one more dimension in healing and becoming closer to one another as fellow citizens in the Kingdom of God and as children of a loving Heavenly Father.

Scott:

Well, thank you for giving this very important and interesting presentation. We really appreciate it.

Ryan:

Thank you.

Endnotes & Summary

Jeffrey’s talk, What Do We Treasure?, explores how different worldviews shape our understanding of the gospel and influence what we see as the “good life.” He identifies four primary worldviews—the Expressive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, and Redemptive Gospel—each defining success and fulfillment in different ways. While Expressive Gospel prioritizes self-expression, Prosperity Gospel equates righteousness with financial success, and Therapeutic Gospel emphasizes emotional well-being, the Redemptive Gospel teaches that true success is found in reconciliation with God. By examining these perspectives, Jeffrey warns that misplaced values can lead people to misunderstand the gospel’s true purpose.

The talk highlights how Gospel Counterfeits arise when cultural influences subtly redefine gospel vocabulary and shift the focus away from Christ. He provides examples of how phrases like non-judgmental love and authenticity take on different meanings depending on the worldview, leading to confusion and potential spiritual drift. Many individuals, even those originally converted to the Redemptive Gospel, gradually adopt cultural values while still using gospel language. This process results in a faith that, while still appearing religious, may no longer align with the teachings of Jesus Christ.

Jeffrey concludes by emphasizing the need for spiritual discernment and doctrinal clarity. While Gospel Counterfeits persist because they offer comfort, validation, or worldly success, the Redemptive Gospel calls for transformation through Christ. Faithful discipleship requires prioritizing God’s values over societal expectations, measuring spiritual success by personal sanctification rather than external achievements. By recognizing and rejecting distorted versions of the gospel, believers can ensure their faith remains rooted in eternal truths rather than cultural trends.

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 9, 2024

- Duration: 26:31 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2024 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: Redemptive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, Expressive Gospel, gospel counterfeits, authenticity, covenant-keeping, LDS worldview, personal fulfillment, character transformation, reconciliation with God, faith crises, gospel vocabulary, Maslow’s hierarchy, LDS apologetics

Common Concerns Addressed

The priesthood ban was purely doctrinal and inspired.

Saltzgiver situates the ban within historical and cultural pressures, emphasizing that revelation came after deep reflection and encounters with global members.

The Church is still racially exclusive.

Points to global membership growth, diverse leadership, and current efforts like Global Histories to amplify voices of all Saints.

Apologetic Focus

The value of global perspectives in overcoming racial bias.

Revelation as a process informed by faith, study, and lived experience.

The healing power of sharing diverse Saints’ stories.

Explore Further

coming soon…

Share this article