https://www.youtube.com/live/ILU1mGUxEVo

An Egyptian Context for the Book of Abraham

Stephen Smoot

August 2021 (Special Evening Session sponsored by the Interpreter Foundation)

Summary

Stephen Smoot explores how understanding ancient Egyptian religion, cosmology, and temple theology can illuminate the context of the Book of Abraham. He argues that many of the themes in the Book of Abraham align well with known Egyptian religious concepts and practices and also addresses critiques of the Book of Abraham. Smoot emphasizes that, while not a translation in the modern sense, the Book of Abraham represents a text deeply rooted in the ancient Egyptian religious world.

Introduction

Steve Densley: Welcome to the evening session of the FAIR Conference. My name is Steve Densley. I am the former Vice President of FAIR and current Executive Vice President of the Interpreter Foundation. Tonight, we’ll be privileged to hear from Stephen Smoot. His presentation is entitled An Egyptian Context for the Book of Abraham.

Stephen O. Smoot is a doctoral student at the Department of Semitic and Egyptian Languages and Literature at the Catholic University of America. He previously earned a master’s degree from the University of Toronto in Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, with a concentration on Egyptology. Smoot earned a bachelor’s degree from Brigham Young University in Ancient Near Eastern Studies, with a concentration in Hebrew Bible, and German Studies.

His areas of academic study and research include the Hebrew Bible, ancient Egypt, and Latter-day Saint scripture and history. From 2015 to 2020, Stephen was a research associate with Book of Mormon Central. He’s currently a research associate with the B. H. Roberts Foundation.

Stephen served as a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in northern New England—the New Hampshire Manchester Mission. It included six months at the Joseph Smith Birthplace in Sharon, Vermont.

And with that, I’ll turn the time over to Stephen Smoot.

Presentation: An Egyptian Context for the Book of Abraham

Stephen Smoot: Well, it’s good to see you all again, brothers and sisters, here. Thank you for coming out tonight for, I guess, round two of Stephen Smoot gets cancelled by the internet by talking about controversial things.

You know, I spoke earlier today on the Bible and LGBT issues. I was thinking to myself, “What’s a really safe, non-controversial topic that nobody has really strong opinions or feelings about?” And—oh! Book of Abraham, of course! You know, why not?

But in all seriousness, I am grateful to be here to be able to speak with you again. I appreciate the opportunity. And I think for this discussion tonight, I’m going to be a little more informal than my earlier presentation. I’m going to both speak a little freely with you but also have some prepared remarks. I figured we’re kind of winding down at the end of the day. It’s kind of a more intimate crowd here with the people that came later. So I figured I could kind of go that way there.

Ground Rules

Now, to lay a couple of ground rules or to start off with some preliminary remarks.

I am here for a few things tonight. I want to discuss the tour [to Egypt] that Steve Densley mentioned. Number two, I want to also discuss this website: Pearl of Great Price Central, a little bit. And then number three, we’ll discuss, as the topic is, an Egyptian context for the Book of Abraham.

Just very briefly—I have been on the Interpreter tour of Egypt, and it was a fantastic experience. I can wholeheartedly recommend the tour. Hany Tawfiq, who is on the tour that I was on, he’s a tremendous guy. Dan, of course, is tremendous, and Steve and everybody else involved in the operation. So if it’s something that interests you, I can absolutely, unreservedly recommend you consider the tour. I think you’ll have a great time.

Pearl of Great Price Central

Okay, with that out of the way—we can talk a little bit about Pearl of Great Price Central. Most of the content I’m drawing from for my presentation is coming from this website.

Some of you may have heard of Pearl of Great Price Central already. I think it’s been mentioned a few times in the conference, perhaps. Or just on your own you may have encountered it. But basically, Pearl of Great Price Central, is sort of a break-off endeavor from Book of Mormon Central.

Kirk Magleby, the executive director at BMC, spoke earlier today. So you have a sense, I hope, of what Book of Mormon Central is. Pearl of Great Price Central—kind of going along with the theme of centralizing things—is sort of a break-off or spin-off project from that.

The mission of Pearl of Great Price Central is to make the Pearl of Great Price accessible, comprehensible, and defensible to the entire world.

Sometimes the Pearl of Great Price gets kind of overlooked or neglected as a book of scripture, which is unfortunate. But hopefully, resources such as Pearl of Great Price Central can help you in your research of the text.

Interviews and Resources

One thing that I have been very privileged to do is to work with these two fine gentlemen — and Steve Thompson. This is John Gee and Kerry Muhlestein. John Thompson and myself were the principal authors and researchers behind the content that you will encounter on PGC.

Because I don’t want to just talk about this all night — if you want to get kind of a video rundown of what Pearl of Great Price Central is, and specifically what we have on the website that addresses the Book of Abraham, I would recommend that you check out these two videos on the Book of Mormon Central YouTube channel. If you subscribe to the YouTube channel, you can find these videos there. These are relatively short interviews with John Gee and Kerry Muhlestein. They give kind of a guided overview to both Book of Abraham issues and also the content on Pearl of Great Price Central relative to the Book of Abraham.

Also, I’m going to discuss these insights — these Book of Abraham Insights. These are just short articles that are meant to be read and consumed. You don’t have to have an expertise in Egyptology or anything like that. But they’re trying to elucidate or clarify things about the Book of Abraham, provide context for your study of the Book of Abraham. In a few instances answer questions or perhaps criticisms that people may have of the Book of Abraham.

Concise Research

You may be aware of the Book of Mormon Central “Know Why”s. These are very similar to these short “Know Why” articles. You can read these pretty quickly. They shouldn’t be too technical, I hope.

We have, I think, forty of these at this point. If you don’t want to slog through all of those, we have two nice little videos that we’ve made that summarize a lot of this research. This time it’s on the Evidence Central YouTube channel, which is another spin-off project from Book of Mormon Central. So if you go to Evidence Central and subscribe, you can find these two little videos that we’ve done on the Book of Abraham.

Book of Abraham Insights

Last thing that I’ll mention, just by way — you may be interested: the Book of Abraham Insights. If you go on the Pearl of Great Price Central website, there’s about, I think, forty of them. These forty articles or insight articles are being right now expanded for book form.

So myself, John Gee, Kerry Muhlestein, and John Thompson, we are working on both expanding and revising these insights. And including some additional insights that aren’t on the website. We hope to have these in book form sometime, perhaps next year. I’m just kind of giving a little teaser. Something to look out for in the coming months and perhaps next year.

So if this whets your appetite, stay tuned. Because hopefully next year we’ll have a book version of these that includes additional content. Just wanted to very shamelessly plug that while I was here and I have my little bully pulpit.

So go check out www.pearlofgreatpricecentral.org and hopefully there will be lots of content there for you to examine.

Egyptian Contexts in the Book of Abraham

Now let’s get into the meat of things here. When we’re talking about an Egyptian context for the Book of Abraham, I think it’s useful to think of two different kinds of contexts that we can kind of construct for the Book of Abraham. There’s the world outside of the Book of Abraham, and the world inside of the Book of Abraham. And here’s what I mean by that.

So the Book of Abraham is — well, it’s a book, right? You can open it up and read it. And there’s a world inside that this text describes, that Abraham is a part of. You can read it independent of the broader ancient Near Eastern world that we have been able to recover through over two centuries of archaeological work, textual studies, and related fields.

So when we’re discussing the Book of Abraham, you can approach it from one of two ways. You can either take the text of the Book of Abraham and sort of see how it fits in the broader world around it, right? But you can also go inside the text and see what things are in the text that provide an ancient context for it.

Another way to maybe think about it is: the world outside the Book of Abraham is the culture, the history, and the peoples of the ancient Near East that did their thing regardless of what’s happening in the Book of Abraham. But the world inside of it. You can think of it as its own self-contained sort of world — what the text describes and depicts. So hopefully that makes sense. Kind of very roughly, these two kinds of contexts that we’re going to try to approach tonight.

The World Outside the Book of Abraham

And we’re going to start with the world outside the Book of Abraham. So we’re going to discuss what was going on culturally, historically, and to some degree geographically in the broader ancient Near Eastern world. Or, I guess, more specifically, ancient Egypt. Regardless of what’s actually said in the Book of Abraham.

The Egyptian Papyri of Joseph Smith

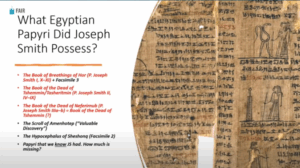

So let’s start, first of all, with this question: What Egyptian papyri did Joseph Smith possess?

We all know the story. In July of 1835, this guy named Michael Chandler rides into Kirtland, Ohio. He has these mummies and these papyri, and he sells them to Joseph Smith. And we used to tell this nice story, but we need to take a step back. What Egyptian papyri did Joseph Smith actually own that we know of? We’ll get to that in a second.

In November of 1967, eleven fragments from Joseph Smith’s papyri collection were returned to the Church. It was assumed for a long, long time that they had all been destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. We can actually trace, after Joseph Smith’s death, where the mummies and papyri went to. Who owned them for certain times. We know which museums they ended up in. A good chunk of them ended up in the Woods Museum in Chicago. Which unfortunately was totally obliterated in the Chicago fire.

And so it was assumed that all the papyri were gone and all the mummies were gone. Until it turns out that there are some that weren’t. A collection of Joseph Smith papyri made their way to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. They were returned to the Church in 1967. Because of that, and because today Egyptologists can read and translate the Egyptian language, we now know that these are the papyri fragments that we know Joseph Smith had.

By the way, the text in red — these are the fragments that were returned to the Church in 1967. So this is what we know Joseph had and what was returned to him.

The Book of Breathings

Let’s start off with the first one: the Book of Breathings of Hor, or Horus. One of the texts that came into Joseph Smith’s ownership was a copy of what is called the Book of Breathings. Sometimes it’s called the Document of Breathings. John Gee has made an argument that it should be called the Letter of Fellowship.

You may not have heard of this book before, so let’s discuss what its purpose was. The Book of Breathings was traditionally understood by the Egyptians to have been written by the goddess Isis, who was the sister-wife of the god Osiris. The title the Egyptians gave to it, was The Document of Breathings made by Isis for her brother Osiris.

The purpose of this book was to provide the deceased with the essential information they needed in the afterlife to be resurrected and hence start breathing again. This sense of breathing — you want to revive the deceased and resurrect the deceased and give them a glorified afterlife with the gods. It contains — you can call them the spells, perhaps. I like to avoid that language because it’s kind of pejorative to talk about magic and spells. But it provides the information that the deceased needs to be resurrected and deified as a god.

The Book of Breathings, cont.

I’m going to read actually the opening lines of the Book of Breathings, which says:

“The Document of Breathings, which was made by Isis for her brother Osiris, to cause his soul to live, to cause his body to live, to rejuvenate all his limbs again, so that he might join in the horizon with his father Ra, the sun god, to cause his soul to appear in heaven as the disc of the moon, so that his body might shine like Orion in the womb of Nut.” Nut is the starry sky that the Egyptians imagined — a goddess of the starry sky.

There are thirty-three known copies of the Book of Breathings. The Book of Breathings that Joseph Smith got — that was owned by this fellow named Hor or Horus (we’ll talk about him in a little minute) — is, so far as we can tell, the oldest copy. The oldest extant copy was the one that Joseph Smith ended up with.

There’s a reason why this is all important. We’ll get to that in just a second. But that’s a brief rundown of the Book of Breathings.

Book of the Dead

Now let’s skip down to the Book of the Dead. Just by raise of hands — how many of you have at least heard of the Egyptian Book of the Dead? You’ve probably seen The Mummy with Brendan Fraser — right? Classic movie.

So some of you are probably familiar, somewhat, with the Book of the Dead. Well, Joseph Smith owned a copy of the Book of the Dead owned by a woman named Tshemmin, or Tshenmin. Depends on how you want to transliterate the name.

As some of you may know, basically the Book of the Dead — first of all, is a modern name. That’s the name that modern Egyptologists give this book. The ancient Egyptians themselves called it The Utterances of Coming Forth by Day.

The purpose of this book was to protect the deceased — the owner of the text. It gives various recitations for aiding the spirit to become exalted. To become deified. Ascend and descend from the presence of a god. Transform into different forms of animals or creatures. And to provide post-mortem protection in the afterlife.

Many of you have probably seen, very famously, the judgment scene from the Book of the Dead, where you have the deceased and they have their heart being weighed on a scale and all that good stuff. That’s coming right out of the Book of the Dead.

Temple Purpose

Joseph Smith owned a copy of this. He came into possession of this copy owned by a woman named Tshenmin.

What’s interesting is, even though the Book of the Dead is sometimes called a funerary text, we also know for a fact that the Book of the Dead was used in the Egyptian temple. It wasn’t strictly a funerary text — it had a temple purpose. There are some significant implications this may have. Both for the Book of Abraham and for the Latter-day Saint temple endowment.

I will refer you to the marvelous work by Hugh Nibley, The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. There’s a rich treasure trove there to mine of material that may be relevant for Latter-day Saints. That’s something that is interesting.

Just for the sake of time, I’m not really going to be able to run down through the rest of this. But like I said, if you go to Pearl of Great Price Central, you can dive into this a little more deeply.

Questions of Missing Papyri

But I also want to stress that these are the papyrus fragments that we know Joseph Smith had. There’s a question about how much papyrus is missing? How many papyri fragments were destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire? How many rolls? Certainly the mummies were destroyed. Facsimiles 2 and 3 are no longer extant — the originals — so they were destroyed, presumably. And there remains a serious question: How much papyrus did Joseph Smith have originally? And did that include potentially the copy of the Book of Abraham that Joseph had — that he translated, right?

So that’s something to consider. This is what we know he had. But there’s a big question mark about what else he may have had that is just now presumably lost.

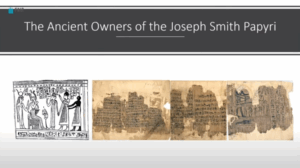

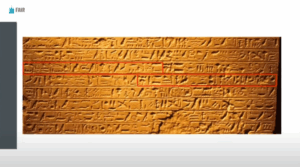

So I mentioned this guy named Hor, who had this copy of the Book of Breathings. By the way, here’s what the Book of Breathings would have looked like originally. You have Facsimile 1 here, which you’ll recognize there on the far right. Then you have these columns of hieratic Egyptian text. And we’re pretty sure that Facsimile 3 would have been at the end of this text, among other reasons because the name of the owner — Hor or Horus — actually appears in Facsimile 3. So if you look down at the bottom row of hieroglyphs there, and you look towards the right, you see that little bird or falcon figure. When you go look in your facsimiles at home sometime, that’s his name. His name also appears in the second column there on the far right by Facsimile 1.

So for a number of reasons, we’re pretty sure that this is what his Book of Breathings would have looked like originally.

Reconstructing Hor

We know what it looked like. And we have his titles and his genealogy. So we can actually reconstruct who Hor was and what his jobs were. And that’s actually really important and really interesting, and it may have significance for the Book of Abraham.

So, Hor lived around the same time of the Rosetta Stone, which is around 200 BC. We know that because we’ve done his genealogy. I’m not joking — we’ve done his genealogy. Because his dad and grandpa and other family members and some of his ascendants had copies of the Book of the Dead and Book of Breathings. So we can reconstruct their family line.

We know that he was a prophet or a priest of three principal Egyptian deities at the temple in the ancient city of Thebes. You’re going to go visit there on the tour.

His job as a prophet, anciently, was to be a spokesperson for these gods. And he was going to interact with these gods in their temples on a daily basis. He would have been initiated into the sacred space of the temple, which represented heaven. And he would have made covenants or promises to maintain strict standards of personal conduct and purity.

Abraham Stories Were Circulating

As a matter of fact, I mentioned how the Book of the Dead was used in a temple context. One portion of the Book of the Dead was actually used in priestly initiation. Sort of their temple recommend questions, if you want to call it that. There’s this series of personal standards of purity and morality that the priests had to maintain. They were getting that from the Book of the Dead. But that’s maybe another discussion.

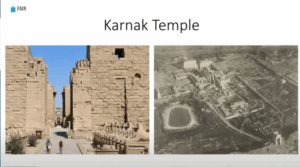

Being a priest or a prophet in ancient Thebes had its perks. For example, Hor would have had access to the great temple libraries at the Karnak Temple at Thebes. He would have been literate. He would have had access to narratives, reference works, manuals, as well as scrolls on mythology, religion, ritual, and history.

It also happens that Hor lived at a time when ancient Egyptian religion was highly syncretic. Where elements of Greek, Jewish, and ancient Near Eastern traditions made their way into the religious culture that Hor was living in. In other words, Hor lived at a time when stories about Abraham were circulating in Egypt. So if any ancient Egyptians were in a position to know something about Abraham, it would have been the Theban priests like Hor. And we’re going to see that in a second.

The Gods That Hor Served

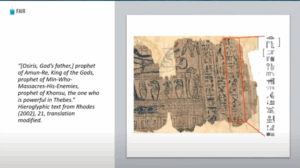

So let’s go through the different gods that Hor served. Everybody have their seer stones out? Because we are going to read some Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Thanks to our ability to read these hieroglyphs in the far-right column, we know what occupations Hor had. We know he was a prophet of Amun-Ra, the king of the gods. He was the prophet of one of my favorite Egyptian deities, Min, Who Massacres His Enemies — that’s his name, right? Min Who Massacres His Enemies. And he was also a prophet of the god Khonsu, The One Who is Powerful in Thebes. I mean, if you don’t believe me, it’s right there. You can read this, so you know I’m not pulling a fast one here.

Let’s go through who these different gods were and why we care about this. Well, Min Who Massacres His Enemies was a lesser-known deity. He was a syncretized deity between the Egyptian god Min and the Canaanite warrior god Resheph. This deity was worshiped by performing human sacrifice in effigy. Two rituals are known for certain with this deity. One involves subduing sinners by binding them, and the other involves slaying enemies and burning them on an altar. These rituals seem to have also been part of an execration ritual that Hor would have performed as a prophet of Amun-Ra. So that may be ringing a bell in some of your ears, right?

Plausability

So what about the god Khonsu, or Chespesichis in Greek? In this capacity Hor would have been involved in a temple that dealt with healing people. With protecting them from demons. The founding narrative of this temple deals with a pharaoh who had extensive contact up in northern Mesopotamia. He takes any woman that he thinks is beautiful as his wife, and asks and receives directions from God. Hor would have been familiar with this story as part of this temple cult.

So knowing about Hor’s occupations, we can say something about the plausibility of a text like the Book of Abraham perhaps having attracted his interest.

If we assume that Joseph Smith had an ancient copy of the writings of Abraham, we have to explain: what on earth was an ancient Egyptian priest doing with a copy of the Book of Abraham?

Well, I think this may go toward explaining a plausible scenario. Or plausibly answering why or how he would have had an interest in a text like the Book of Abraham. I find that highly significant. There’s more I could say here, but I’m just zipping along for time. We’re going to have to move along.

Where Hor Worked

By the way, here’s the Karnak Temple. This is where Hor worked as the prophet of Amun-Ra. Those on the tour are going to go to this temple. On the right there is a lovely aerial photograph that was taken back in 1914 of the whole temple complex. And I think you’ll spend a good solid day there, exploring the Karnak Temple and the surrounding area of Thebes. If you want to go and see the place where Hor worked, this is a great chance to do that.

The Ancient Egyptian View of Abraham

Let’s talk about this issue: what did the ancient Egyptians know about the biblical figure of Abraham, if anything? Did they have any knowledge of biblical figures, including Abraham?

In fact, there is evidence to suggest that they did. This goes a long way toward creating a plausible scenario outside the text of the Book of Abraham. We can imagine a text like the Book of Abraham would have circulated and perhaps have been transmitted. Evidence survives indicating that stories of Abraham were known to the ancient Egyptians as early as the time period of the composition of the Joseph Smith papyri.

So let’s run through a couple of examples of these texts. The first and most important text — and this is going to shock you — is the Bible. The Bible was circulating in ancient Egypt at the time of the Joseph Smith papyri. Hanna Syriac, yesterday in her talk, mentioned the Septuagint. The ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible that was done in ancient Egypt. That was done in or near Alexandria. So they had the Bible circulating at this time period.

Authors

How about some others? We have a text attributed to a fellow named Hecataeus of Abdera. He’s a Greek historian. Unfortunately, this text doesn’t survive; it’s only quoted by other ancient authors. But they attribute this text to him, wherein he supposedly writes an account about Abraham going down into Egypt.

We have another author named Eupolemus. He recounts how Abraham lived in Heliopolis and taught astronomy and other sciences to the Egyptian priests. That should send off some alarm bells.

We have another author — and by the way, some of these texts in antiquity are attributed to these figures. Modern scholars today may debate or doubt whether these figures actually composed these texts. But what’s important for our purposes is that in antiquity, at the time, they were attributed to these individuals. Whether they actually wrote them or not is a question. The texts for sure were real and were circulating. We just can’t always be sure about their authorship.

So how about the Egyptian Jew Artapanus, who lived in the first century BC and who wrote an account of Abraham teaching astronomy to the Egyptian pharaoh. Not just the priests, but specifically to the pharaoh. That should call to mind Facsimile 3.

We have Philo, the first-century AD Egyptian Jew, who wrote a lot about the Bible. In one of his works, he claims that Abraham studied astronomy, the motion of the stars, mathematics. He claims he used his reasoning on these to understand God.

Texts

We have this text called the Testament of Abraham. It describes Abraham’s tour of the next life before he dies. This was probably written in the first century AD by an Egyptian Jew. It is notable for its reinterpretation of the Egyptian judgment scene from the Book of the Dead in a Jewish fashion. That also may be very significant.

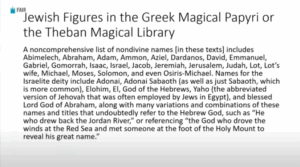

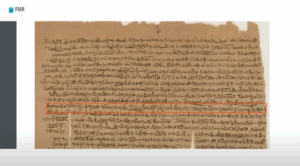

Now there’s also something else. Some of you may have seen this picture before — of this papyrus here. This papyrus comes from a corpus of texts called the Greek Magical Papyri, or sometimes the Theban Magical Library. What these are is a group of texts from ancient Thebes — from ancient Egypt. They contain magical spells, formulae, hymns, and rituals. And they were written between the second century BC and the fifth century AD.

The reason why I’m highlighting this papyrus is because I have underlined there in red at the bottom the name of Abraham. Abraham and other biblical figures are used in these magical papyri.

In this case, this is a love spell. The woman is on the lion couch, and it seems some kind of a pun is going on, where the woman will be consigned to the flames of love. But consigned to the flames by reciting this magical spell. The name of Abraham is invoked in the series of magical words that are used in this spell.

Ancient Egyptians Knew About Abraham

But it’s not just this one. Here’s a nice quote from Kerry Muhlestein, who’s done some great work on this. If you look through all these papyri, these spells, and you isolate biblical figures that are used, a non-comprehensive list includes: Abimelech, Abraham, Adam, Ammon, Azazel, Dateros, David, Emmanuel, Gabriel, Gomorrah, Isaac, Israel, Jacob, Jeremiah, Jerusalem, Judah, Lot, Lot’s wife, Michael, Moses, Solomon, and — my favorite — Osiris-Michael (like the archangel).

You have Israelite names for deity such as Adonai, Adonai Sabaoth, El, Elohim, Yaho— the abbreviated form of Jehovah. It goes on and on.

Abraham and Moses were particularly popular amongst the Theban priests that composed this corpus of papyri. They used the names of Abraham and Moses very frequently. They invoked them in certain ways in these spells.

What this shows is that the ancient Egyptians, around the time of the Joseph Smith papyri, knew about Abraham. There were stories circulating about Abraham. There were accounts circulating about Abraham. And so this creates a plausible sort of transmission route for how an Egyptian priest like Horus could have known about Abraham.

It doesn’t prove that he did, mind you, but it’s a way to plausibly account for it. If we make certain assumptions.

Jews in Ancient Egypt

Let’s talk about this place: the island of Elephantine, or Elephantine. I think you’re going down to Aswan, right, Steve? So somewhere in the vicinity you’ll see it. You’re not going to actually go on the island, but you are going to sort of sail right past it.

The reason why this is important is because there was a very prominent Jewish settlement here on this island. Way down in southern Egypt, near modern Aswan. Historians and archaeologists have been able to trace that, from around 700 BC or so down into the Greco-Roman period, you had massive waves of migrations of Jews — or you could say Semites or Levantine peoples, perhaps — coming from Syria, Canaan, or Palestine down into Egypt.

Not only that — not only did they come down — they brought with them their texts and their traditions. They brought with them their language, obviously. They brought with them their religious customs and they created settlements all over Egypt — not just in Elephantine, but elsewhere.

Evidence

Okay, Alexandria, that’s another obvious example. We have a thriving Jewish community in Alexandria. We have other sites like Leontopolis, Oxyrhynchus, and Thebes where we have locations with attested Jewish presence. They are all over the Faiyum — this oasis that was created sort of southwest of modern Cairo.

Significantly, we have synagogues. That’s how we know that we have ancient Jews in Egypt. Among other reasons, we have been able to uncover synagogues. Or we have texts that describe synagogues appearing in these locations.

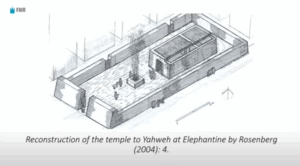

As I mentioned, they also brought their texts with them, which were disseminated. Here’s the great kicker: there are at least two known Jewish temples to Jehovah that were built in Egypt. One of them was built in Leontopolis — which is in the Nile Delta. The other was built right down here at Elephantine.

Here is a nice little reconstruction of this temple. And as you can see, it follows very nicely the tripartite division of Solomon’s Temple or the Jerusalem Temple. You have the outer court, the inner sanctuary, and the Holy of Holies. This is well known and well documented.

How Did Abraham’s Writings Get Into Egypt?

So if we want to ask ourselves the question: “Okay, how does a copy of Abraham’s writings get into Egypt?” Well, this might very well explain how. It could be that Abraham’s descendants brought the text with them. Which was then subsequently transmitted and copied until a copy ended up in the possession of this priest named Hor. Hor had this papyrus that later, Joseph Smith found.

Again, for this to work, you have to assume that there is an actual ancient Book of Abraham text that Joseph Smith was translating. There’s another thought or theory that Joseph Smith was simply revealing the text of the Book of Abraham with the papyrus acting as a sort of catalyst for revelation. That’s a perfectly fine and interesting theory. If that’s the case, then this maybe doesn’t have a lot of relevance. But if you do want to believe that there were some ancient Abrahamic writings that Joseph Smith translated, this could explain why. I believe it provides a plausible scenario that explains why.

So I hope that gives you kind of a brief rundown of what we have here on the world outside the Book of Abraham.

The World Inside the Book of Abraham

Now, with about fifteen minutes left — we can discuss the world inside the Book of Abraham. Let’s take a look at some of the features of the text of the Book of Abraham. We can fashion a plausible ancient Egyptian context by converging what is described in the text with what we know from the outside world.

Human Sacrifice

First off, whenever you talk about the Book of Abraham, you’ve got to talk about this: human sacrifice. This is what Facsimile 1 is depicting. And right off the bat in Abraham chapter 1, this is what is happening to Abraham. He narrates how he ran afoul of his countrymen up in Ur of the Chaldees because he would not worship their false gods. So they were going to sacrifice him.

Now the question becomes: did ancient peoples practice human sacrifice? More specifically: did the ancient Egyptians practice human sacrifice?

We need to ask this question because in the first chapter of the Book of Abraham, the people in Ur of the Chaldees are said to sacrifice Abraham “after the manner of the Egyptians” (verses 9 and 11). The priest of this god named Elkenah is said to also be a priest of the god Pharaoh. Which is an Egyptian god.

So Abraham’s kinsmen in Ur of the Chaldees clearly had some conception of Egyptian practice. And they seemed to be imitating Egyptian practice.

So, did the Egyptians ever practice human sacrifice? That’s a question scholars have discussed and debated. A big part of the debate is what terminology do we use. Do we call it “human sacrifice”? Do we call it “ritual slaying”? “Sanctioned violence”? “Sanctioned killing”?

Ritual Sacrifice

Whatever you want to call it, basically, the answer is: yes. We now have pretty good textual and archaeological evidence that the ancient Egyptians would ritually slaughter human beings in some kind of ritualized manner. Frequently, they would do it in response to a trespass or a breach of some kind.

For example, there is archaeological evidence for human sacrifice at the Egyptian fortress of Mirgissa in what is now northern Sudan. During the time of Abraham, this part of the world was part of the Egyptian empire. Under Egyptian control. Discovered at the site was an archaeological deposit that contained various ritual objects. Melted wax figurines, a flint knife, and the decapitated body of a foreigner slain during rites designed to ward off enemies.

Almost universally, this has been interpreted by Egyptologists as evidence of “human sacrifice.”

So we have both texts that describe this. They’re called the execration texts. And the point of the execration texts is to ward off evil through ritually slaying or destroying effigies. And it seems that on some rare occasions, this was actually done to human victims. We seem to have at the site at Mirgissa an example of actual human sacrifice. That’s what various Egyptologists have called it. That’s not my editorializing. So that seems to be highly significant.

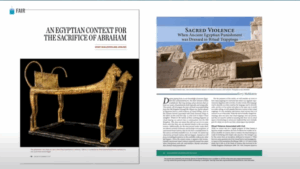

Egyptian Context

There’s more we could talk about on this, obviously. But I think it’s safe to say, whatever terminology we debate using, the basic answer is yes.

And I will refer you to these two pieces for your further reading. If you’re interested, these are free on the Pearl of Great Price Central website. We have a bibliography for resources on the Book of Abraham, and these two articles are:

- “An Egyptian Context for the Sacrifice of Abraham” by John Gee

- “Sacred Violence: When Ancient Egyptian Punishment Was Dressed in Ritual Trappings” by Kerry Muhlestein

By the way, Kerry Muhlestein did his dissertation work on the subject at UCLA, and his dissertation has been published. It’s great. If you really want to nerd out like I do about this stuff, definitely hit up Kerry Muhlestein’s dissertation on sanctioned killing in ancient Egypt. I’m seeing everyone’s eyes roll already as I say the name. But it’s really good stuff, I promise.

So you have a pretty strong way that you can create an Egyptian context for something that’s depicted inside the Book of Abraham.

Did Abraham Lie About His Wife Sarai?

Let’s pick out another example. Oh, here’s a big question: did Abraham lie about his wife Sarai?

You remember the story, right? This appears both in Abraham chapter 2 and Genesis chapter 12. He’s about to go down into Egypt and he stops and says, “Okay, Sarai. When we get down there, make sure that you tell the Egyptians that I am your brother and not your husband.”

He does this clearly to preserve his life. The assumption that Abraham seems to have is because Sarai is so beautiful, the Egyptians will see how beautiful she is. They will become uncontrollable with their lust. They’ll want to kill Abraham and take Sarai for themselves.

We know the story from the Bible — it’s in Genesis chapter 12. But the key difference with what we have in the Book of Abraham is, in the Book of Abraham, God tells Abraham to do this. God appears to Abraham in vision and says, “Before you go down into Egypt, tell the Egyptians that Sarai is your sister and not your wife.”

Well, this has proven kind of problematic for some people, because it seems like God is telling Abraham to lie. So the Book of Abraham was published in March of 1842. As early as July of 1842 I can document anti-Mormons raising this point: Joseph Smith’s Book of Abraham blasphemes God by having him tell Abraham to lie. So this is serious stuff, and it’s been around with us for a while.

Ambiguous

There are a couple of things to point out here. First of all, Genesis chapter 20, verse 12, identifies Sarai as Abraham’s half-sister. So it’s possible that he meant “sister” purely as sort of an ambiguous term. “Oh, she’s like a relative of mine,” right? You could maybe sort of make that argument, I suppose. He was just being ambiguous; he wasn’t necessarily outright lying.

There are also people who’ve pointed to the fact that Mesopotamian legal documents of the time will use the language of “sister” to describe a woman that a man has care or legal responsibility for. That argument has come under debate. Some scholars push back against it. But it’s another argument that’s been made, just so that you’re aware.

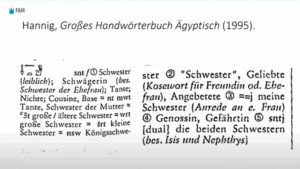

For my money, this is an argument I’m especially fond of and that I think is especially interesting. It has to do with what the ancient Egyptians may have thought about this.

Who here has knowledge of German? Who here is good with their German? I know Dan Peterson’s good with German. I know probably some others are as well.

Definitions

This is from a standard Egyptological lexicon and dictionary. As a matter of fact, I use this dictionary in my classes that I’m taking right now. It’s standard in the field. If you look up the entry for “sister” in Egyptian — snt, and this is the form of Egyptian spoken in Abraham’s day that this dictionary is covering — you’ll discover a couple of entries.

First of all, you’ll see the straightforward entry for Schwester — so, “sister,” right? And specifically leiblich, a bodily or corporal sister. A physical, actual sister — that’s what snt can mean. Okay, that’s fine. It can also mean like an aunt or a niece or a cousin or something like that. So you’ve got a little more ambiguity there.

But look at definition two. Schwester in scare quotes. Geliebte, in other words, it’s a term of affection, a term of endearment for a female lover, romantic partner. Freundin or Frau, a wife.

So, if Abraham is going into Egypt and the Egyptians say, “Who is this person?” and he says, “Oh, this is my snt,” as far as the Egyptians know, he can mean one of these two things. And they wouldn’t be able to really tell the difference.

Is Abraham Lying?

So is Abraham lying? I don’t think so. I think he’s being deliberately vague. And I think you have a plausible way that you can understand why he was being deliberately vague. And how he was being deliberately vague. It has to do with this ancient Egyptian terminology.

If you want a wild ride, go read some Egyptian love poetry, where the lovers in the poems refer to each other as “brother” and “sister.” I don’t know about how the kids are texting and dating these days, but that’d be kind of weird, right? To be calling someone you’re interested in “sister” or “brother.” But whatever — no judgments — that’s what the Egyptians were doing. That’s what they were into, I guess.

So you can see this ambiguity here at play. I think that’s what’s happening in the Book of Abraham. That helps us understand the story better.

By the way, it’s noteworthy to point out that there is a text called the Genesis Apocryphon discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls that depicts Abraham as being warned in a dream that he’s going to face danger in Egypt. And so this prompts Abraham to lie — well, to call Sarai his sister instead of his wife. It doesn’t explicitly say in the Genesis Apocryphon that God told Abraham to do this. But it very heavily implies that this is what happened. That God sent him this dream where he was warned about it, and so he came to this conclusion.

For whatever it’s worth, I think that harmonizes nicely with the Book of Abraham account. That’s just another interesting piece of ancient evidence that could help us make sense of this interesting story.

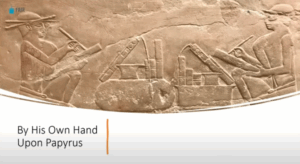

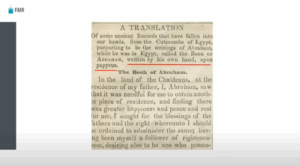

“By His Own Hand”

Let’s move on to another topic. Let’s talk about this idiom: “by his own hand upon papyrus.” If you open up your Book of Abraham and you read the introductory paragraph to it, you will see, “Translated by Joseph Smith from the Egyptian papyrus, called the Book of Abraham, written by his own hand upon papyrus.”

Here you go — this is the 1842 Times and Seasons superscription that Joseph Smith gave to the Book of Abraham. He says it’s “written by his own hand upon papyrus.”

First problem. Does this mean that Abraham himself physically wrote the papyrus that Joseph Smith received from Michael Chandler? It seems that Joseph Smith and other early Latter-day Saints believed that. That seems to have been the assumption they had when they got this papyrus from Michael Chandler.

The evidence for that is kind of ambiguous in some ways. It comes from more secondhand, hearsay sources. They could have been confusing what Joseph meant by saying this. It’s still an open question. I think he probably did — he and the early Saints probably made this assumption — but that’s an open question.

The First Problem

That’s the first problem: was this written by Abraham? But if it was, we have another problem. The papyri date to about 200–250 BC, but Abraham lived around 2000–1800 BC. So we have an incongruity here. How could he have written this manuscript when it dates to well over 16 centuries after he lived?

Well, I have good news for you all. The good news is that the phrase or idiom “by the hand” is attested in ancient Egyptian. And in ancient Hebrew, for that matter. In the Bible, “by the hand” simply means “from someone.” That’s all that it has to mean. It does not necessarily have to mean that the individual themselves wrote the record that has this reference to it.

If you look at these Egyptian grammars that discuss the Egyptian language of his time, and you look up this phrase “by” or “in the hand,” you’ll see it can mean “in the possession of,” “in the charge of,” “from,” “through,” “because of,” “done by,” or “done through so-and-so.” It simply denotes agency. It’s describing the agency of the document to the person who either wrote it or commissioned it. Or had it created or was responsible for it.

This becomes less problematic for the Book of Abraham, I feel.

Example

Let me give you some examples of what I’m talking about. Sorry, we’re going to have more hieroglyphs, so I hope you still have your seer stones out. This is the famous Kamose Stela. Kamose was the pharaoh who unified Egypt after the Hyksos divided it into separate dynasties. There was a big civil war, and Kamose came along and made things right again.

In the Kamose Stela, there’s his big victory stela commemorating his defeat of the Hyksos. He says, “I found it,” referring to a letter. I should step back and say that in the stela, Kamose says how he found the messenger for the enemy king. A guy by the name of Ahusara. So he finds the messenger boy for this king and the messenger has this letter from the king that he’s holding. So he says, “I found it,” meaning the letter. Saying in writing, [outlined in red on the slide] “by the hand of the ruler of Avaris, Ahusara, the son of Ra Apophis. Greetings to you, my son, the ruler of Kush.”

So it’s a letter from the king to his son being delivered by this messenger. It’s right here– “by the hand of the king of the Hichsos ruler of the city of Avaris.” It’s said to be “by his hand.” It uses that literal idiom to describe it. Almost certainly, the king did not himself write this letter. Assuming it was a real letter that was actually composed, it would have been composed by court scribes. But he claims authority and possession of it. So he says it was “written by my own hand.”

Second Example

Second example: this is the Story of Setne Khamwas. It’s written in a form of Egyptian script called Demotic. It dates to the Roman period — a little after the Book of Abraham papyri, but not too much.

In it, and I’ve highlighted it here for you, a woman magician says to Setne: “If it so happens that you want to recite a writing, come to me, so that I can have you taken to the place where it — this particular book or literally papyrus — of which Thoth was the one who wrote it with his own hand himself, when he had come down after the other gods.” So it uses this idiom again — “written with his own hand” — which in Demotic denotes necessarily nothing more than authorship.

So, we have two examples of this phrase where we don’t necessarily have to assume that the person who “wrote it by his own hand” actually wrote it by his own hand. That may seem counterintuitive and weird to us, but this is the idiom that the Egyptians used. As I mentioned, the Hebrew Bible has examples of this too. A prophet gives an oracle to the people, and it’s written down or commissioned. And the oracle is said to be bayad, “in the hand” or “by the hand” of the prophet. That’s very well attested.

Options

We have two options. Either Joseph Smith did, in fact, assume that the papyrus was written by Abraham himself. And he just simply had that assumption. it was a mistaken assumption, but that’s okay. Or, and this is the alternative that people like Hugh Nibley have suggested, the whole phrase “The Book of Abraham, written by his own hand upon papyrus” was actually the ancient title for the Book of Abraham. That phrase “written by his own hand” would have been the ancient designator attributing the text to Abraham as the author. Not necessarily the physical scribe, but the originator of the content.

Conclusion

So, let’s quickly wrap this up here with this conclusion. Here’s what I am not trying to do. I am not trying to say that all of this proves the Book of Abraham is true. So please don’t walk away saying, “Stephen Smoot has once and for all proven the Book of Abraham is true beyond any shadow of a doubt. Take that, anti-Mormons!” Right? That’s not what I’m trying to do here.

Rather, what I am trying to do is to show that this context—both outside and inside the world of the Book of Abraham—can plausibly situate this text in the ancient environment that it purports to be deriving from. It can also inform us how we approach the text and how we read the text. And I believe it does positively affect how we evaluate Joseph Smith’s claims to having been an inspired translator.

I also believe very strongly that reading the scriptures in a real-world context can help you better understand and comprehend the message. It sort of brings it to life. It can help resolve questions we might have, or it might answer incongruities that we may see in the text. And it makes it, I guess, sort of come alive.

“Ask the Right Questions and Keep Looking”

This is also why I recommend, if you get a chance, to visit places in Israel and Egypt. Visit the Holy Land or other ancient Near Eastern settings—or perhaps with Church history, visit Church history sites—to help you visualize and make really concrete connections with what you’re reading in the text and what you’re seeing around you.

Finally, this is kind of my own personal guiding paradigm when it comes to the Book of Abraham. It’s what Hugh Nibley said many, many years ago. The key with approaching the scriptures from a scholarly perspective is to “…ask the right questions and keep looking.”

Like I said, we’re never going to prove the Book of Abraham is true. And that’s not what I’m doing here tonight. But we can ask good questions. We can evaluate it based on the evidence we have. And we can keep looking for more. All the while being assured from a spiritual witness that the scriptures are true, and complementing that with these academic resources and evidences.

Thank you very much for your attention tonight.

Q&A

Steve Densley:

We don’t have any time for questions, but let me ask you just a couple of things really quick. I mean, we got a number of questions. But you would have to give a whole new presentation, I think, on most of these questions.

Let me just put a plug in again: PearlGreatPriceCentral.org. These articles there would be a great resource for preparing to go to Egypt. So you ought to take a look at those.

Really quickly, can you recommend something that people could read about? You mentioned some of the traditions of the early life of Abraham that talk about him being in Egypt. They’re outside of the Bible or Latter-day Saint scripture—what could you recommend?

Stephen Smoot:

Well, there’s a really great book that was published back in 2001 called Traditions About the Early Life of Abraham. This is a great book. The problem is it’s like 600 pages, and it’s out of print, and copies run for like 200 bucks. So if you’re really adventurous and really gung-ho about learning about that, check out Traditions About the Early Life of Abraham.

However, most of you probably won’t want to do that or can’t do that. So, John Gee’s book, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham, kind of distills some of these traditions in a chapter or two that he’s written. Also, on the Pearl of Great Price Central website, in the bibliography is a spin-off article that the late John Tvedtnes, who was one of the editors of this Traditions book,wrote. A spin-off article summarizing the most salient traditions that he was able to identify. You can access that on the Pearl of Great Price Central website.

So check out John Gee’s book, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham. And check out John Tvedtnes’s article, which you can get on the Pearl of Great Price Central website.

Steven Densley:

Okay, two more quick questions. One, you talked about Elephantine and that there was an Israelite temple there. What’s the significance of finding an Israelite temple outside of Jerusalem?

Stephen Smoot:

Well, among other things, it indicates very clearly that ancient Israelites didn’t have a problem with building temples outside Jerusalem. And we now have that abundantly demonstrated and documented, because we’ve actually found other ancient Israelite temples outside of Jerusalem. And so it shows that they didn’t have a problem with it. I mean, go into Google Maps and look at the distance between Elephantine Island and Jerusalem. You’ll see that’s pretty significant for the ancient world, right? Traveling that far outside of the land of Israel. So even when they were pretty far-flung, they still thought it was important enough to build an ancient temple.

It also indicates that there was enough of a Jewish presence there that they needed a temple, right? You don’t need a temple, really, if it’s just you and your family, basically, right? It’s once you have an established community that needs to keep these religious rites going to keep the community going. That’s when you need a temple. And they had that.

Steve Densley:

And what time did that community date to?

Stephen Smoot:

So the first Jews arrive at Elephantine, we think, sometime around 700 BC. They were mercenaries for the Egyptian army preparing to fight against the Babylonians who were about to blitzkrieg their way through the ancient Near East.

So the first settlements there, we think, were around the Babylonian period. I said 700—I meant 600 BC, I’m sorry—around that time period after the exile. So after Babylon has destroyed Judah and they’ve sent the Jews into exile, that’s when we seem to have a lot more waves come down. So, in the Persian period, in other words. Right? So Babylon is replaced by Persia less than a century after the destruction of Jerusalem. And with the exile, many Jews are coming down into Egypt. Sort of as refugees, right? Displaced persons because their homeland has been destroyed.

Steven Densley:

All right. So critics of the Book of Mormon that say there’s no way that a community of Jews would build a temple outside of Jerusalem? We can find evidence that they did. About the same time that temples were being built in America, there were Jews building temples in Egypt.

Stephen Smoot:

Those critics are wrong.

Steve Densley:

And what else can we tell the critics about the name Sariah that comes from Elephantine Island?

Stephen Smoot:

Sariah is attested in Aramaic papyri written at the island. And I will refer you to the excellent article written by my friend and former Book of Mormon Central colleague, Neal Rappleye. It’s on the Interpreter website, and it’s about the name Sarai being attested as an authentic Jewish name at this island.

Steve Densley:

As a woman’s name.

Stephen Smoot:

That’s right.

Steve Densley:

Where we didn’t find it as a woman’s name in the Bible, right?

Stephen Smoot:

It’s a male—it’s a man’s name in the Bible. But it’s a woman’s name at Elephantine.

Steve Densley:

And when did they find that name?

Stephen Smoot:

When did they find it? It’s not in Joseph’s lifetime. It’s after Joseph’s lifetime. I don’t know the specific papyrus—Neal discusses it in his article—but it’s well after Joseph’s lifetime. And so there’s no way that he could know about it, right?

Steve Densley:

So anyway, thank you, Stephen. Fantastic. And hopefully, we’ll go to Egypt with you again sometime.

Stephen Smoot:

I hope so. Thanks, appreciate it.

Steve Densley:

Thank you all for being here tonight.