“Book of Mormon Voices” by Paul Fields et al. from the 2021 FAIR Conference

Book of Mormon Voices

Paul Fields

August 2021

Summary

This presentation applies stylometric analysis—a statistical study of writing styles using function words—to demonstrate that the Book of Mormon contains distinct authorial voices that differ from both Joseph Smith and 19th-century fiction writers. It shares various scientific tools that help us identify and know the various writers of the Book of Mormon.

Introduction

Scott Gordon: Our next speaker is Paul Fields, and he has brought a host with him, so he’s going to be putting on this presentation. He’s worked with the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship on stylometric and authorship attribution studies of the Book of Mormon and other documents. He has more in his bio. Because of the length of his presentation, we’re going to forego the Q&A on this one. And so, with that, I’ll turn the time over immediately to Paul Fields.

Presentation

Paul Fields: Thank you, Scott. It’s great to be here today. Ladies and gentlemen, let’s talk about the Book of Mormon voices.

I have my team with me here today, and each of us will take an opportunity to speak with you and share with you the work that we’ve been doing.

Stylometry and Authorship

You know, whenever you read a text, often you read that and say, “You know, there’s a familiar ring to that. It sounds like maybe Mark Twain might have written that,” or, “Perhaps it was written by Ernest Hemingway.”

When you read these words:

“Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.”

You know that those are the words of Robert Frost. It’s iconic words—in all of the English language—are those right there. And you know who the author is simply by reading those words.

We work in an area of research called stylometry. Stylometry is simply a statistical way of measuring an author’s style. We can answer questions like, “Who wrote that text?” or “Whose style is this the most familiar to? Who’s similar to this in their writing habits?”

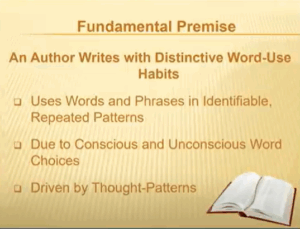

Because we deal with a fundamental premise: that all authors have a writing style. They have a habit of forming expressions where they use identifiable words and phrases and a profile of frequency that is unique to them and the way they form their thoughts.

This is subconscious—and more often, unconscious—expressions. The style markers that we use are what are called function words. In the English language, there’s about 300 function words. They’re words like “the,” which is the most common word, “a,” “an,” “but,” “with,” “without,” and so on.

Now, when you hear those words, you don’t know what the speaker might be referring to, so we call those non-contextual words. But they do form the structure that the speaker—the writer—is using to make their expression and deliver their message.

How Stylometry Works

Let me show you how this works.

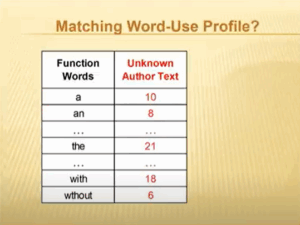

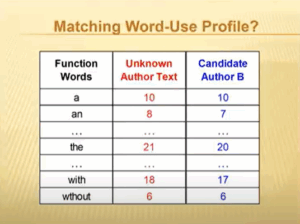

If we have a list of function words on the left-hand side, and we have a text of unknown authorship in red, we can look at the frequency with which those function words are used in the text.

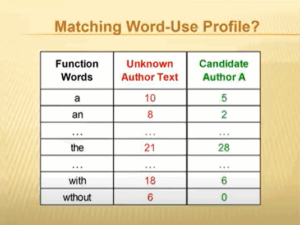

The word “a” is used 10 times. The word “and” is used 8 times. “The” is used 21 times, and so on—a profile of word frequencies. We take a candidate author, and we compare his or her frequency of the use of those same words and see if they’re similar.

If we look down the list of the green words for the Candidate A author: 5 is not very close to 10, 2 is not close to 8, and so on.

But on the other hand, Author B—his or her profile matches more closely the word profile frequencies for those function words in the unknown text. And so B is probably a more likely candidate for the writer of the words in the unknown text.

The statistical technique that we use is called discriminant analysis. We want to discriminate between things. We want to be able to classify objects. And so we look for those things that are similar, but also those things that are different.

Where are the Differences

Now, I’m sure you’ve played this game before where you have two pictures and you ask the question: “Where are the differences?” And when you look at them, they look very similar, but there are distinct places where they are different.

So what we do is we compare the features that best separate those things that might otherwise look very similar. There are the distinguishing features.

And then we take and we order those in sequential order, from most distinguishing to least distinguishing. And then we have a set of features that can distinguish—discriminate—between one text and another.

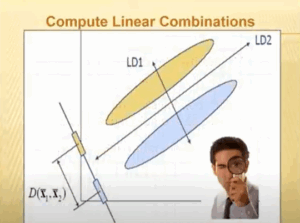

Mathematically, we create what are called linear combinations of those features. We simply add them together in a way that will show where the separations lie. So we can then visualize graphically where the distinctions might be.

Frequency

We have a plot that might look like this. We would have one text that would be in yellow, and another text would be in blue. And we can look along the axes to see where the differences lie.

Now in stylometry, we use these most frequent words—the frequency of the words—to make the distinctions. So we count up: how many times does an author use these distinguishing words? How do the authors compare?

The Federalist Papers Case Study

The classic example of this technique was with the Federalist Papers.

The problem was this: The Federalist Papers were written between 1787 and 1788 and published in New York City newspapers encouraging the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. There were 85 in total, and they were published anonymously under the name of “Publius,” which means “The Federalist.”

Of those 85, though, 12 of the papers were of disputed authorship—although we knew that Hamilton, Madison, and John Jay wrote all 85 of them in some sequence. The authors were dead, and Hamilton and Madison had very similar writing styles, so distinguishing the 73 known authorship and the 12 disputed authorships was quite a statistical problem.

Mosteller and Wallace in 1964 undertook the challenge of seeing if statistics could be used in the way that I’ve described to identify who the unknown authors might be.

One of the things that they found was that Hamilton preferred to use the word “while” and used the word “upon” very frequently. Madison, in comparison, preferred to use “whilst” instead of “while” and didn’t use “upon” hardly at all. So those were distinguishing style markers that could be used to identify who might have written the 12 disputed papers.

And it turns out that the styles in the disputed papers are far closer to Madison than to Hamilton.

Book of Mormon ”Wordprints”

In 1980, three researchers at BY–Wayne Larson, Al Rencher, and Tim Layton–inspired by Mosteller and Wallace, undertook to apply these techniques to the Book of Mormon.

They used non-contextual words, looking at the frequencies throughout the Book of Mormon for evidences to see if there’s multiple authors throughout the Book of Mormon, as is claimed by the text. The researchers also noted that Joseph Smith’s style did not match any of the styles within the Book of Mormon. They actually coined the phrase “wordprint analysis” as a play on words for “fingerprint” to describe this approach.

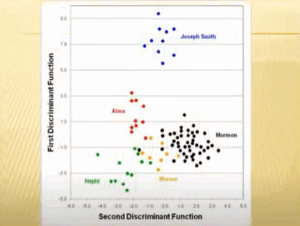

And this is a graph that they produced in 1980 showing the distinctions between Mormon on the right-hand side in black, Nephi on the left-hand side in green, Alma in red above them with Moroni in between. Quite interestingly, Moroni is close to his father, Mormon. But Joseph Smith, in blue, is unlike any of the Book of Mormon speakers.

Another Approach

Another approach was taken by John Hilton at the University of California, Berkeley, and then at BYU. He came up with the same conclusions, although he used a different methodology. His methodology was verified when the FBI asked him to examine the manifesto from the Unabomber to see if it matched the writing style of one of their suspects. They were very disappointed when he told them that the styles did not match, but his methodology was verified when they later discovered that he was right and they were wrong—and their suspect was not the real Unabomber.

[Video Plays: John Hilton Explains Principal Component Analysis]

Hilton: Here’s the way we statisticians like to display a great amount of information. It’s called Principal Component Analysis. It’s a way of trying to put most of the variables that we’re going to measure in all of my 65 wordprints into two or three or four dimensions so we can get a grasp of it.

You’ll notice here that Joseph Smith, the little red one—we see that he clusters very tightly. Now the clustering means that while he’s writing the same way, statistically he looks like himself. The little red one down here represents Joseph Smith when he wrote letters to Emma and to the Church—his own handwriting material, together with “Joseph Tells His Own Story.”

Now then we compare that with Oliver Cowdery—who sometimes is accused of having written the Book of Mormon. We compare it against Oliver Cowdery’s own writings. Oliver Cowdery did a great deal of it, so we’ve got a lot of examples of his own writing. He clusters very much off across the page from Joseph Smith. And therefore, they’re completely different writings. We aren’t surprised.

[Video Continued]

Then let’s look at what happens when we do the Book of Mormon. Now, this is of course assuming that the Book of Mormon was an invention of 19th-century English—as some people might speculate. And if so, we find that Alma sits completely independent of both Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery. And that Nephi, and we had almost 20,000 words of Alma and 15,000 words of Nephi which can be directly compared, but we find that they’re completely on the other part of the probability curve of where this kind of author stands.

So what this has done is it has completely negated the hypothesis in which this study was made—that is, that it was all a 19th-century-type of English production by somebody. It certainly wasn’t by Joseph Smith, and it certainly wasn’t by Oliver Cowdery. But it turns out that it wasn’t by anybody—because there are at least the two independent ones. [End of video]

Modern Computational Tools and Expanding the Analysis

Paul Fields: I thought it was quite clever of Brother Hilton to make that three-dimensional model to show the relationships of the speakers in the Book of Mormon.

Well, that was 40 years ago. Most of that was done by counting things by hand. But today we have vastly more powerful computers that we can use. We have more sophisticated statistical analysis that we can use, and far better graphical techniques.

And with these, we can answer more questions. Questions like: Can authors actually create distinctive styles for fictional characters? Let’s take a look at some 19th century novelists.

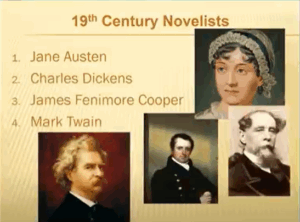

19th Century Novelists

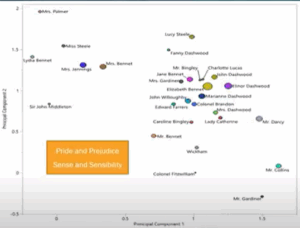

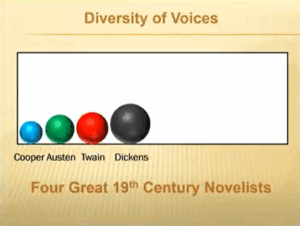

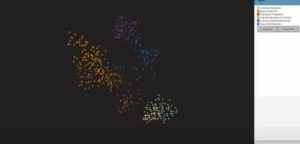

Scout Collins: My name is Scout Collins, and this is what we did. We took four 19th-century novelists—Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, James Fenimore Cooper, and Mark Twain—and we examined two books by each author, and every character in their books that contained more than 500 words. We did a stylometric analysis, as Dr. Fields was explaining, using the principal components. And we see that each author has certain plots.

Now, these represent the various characters in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility. From the principal components, you can see that the characters that Jane Austen is able to create are distinct from one another. Elizabeth Bennet is different from Mr. Darcy.

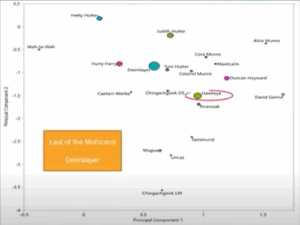

This pattern is repeated across other authors.

Charles Dickens—two of his most popular books. A lot of these books are ones that you would have read in high school or college, in English class. Easy to tell when you’re reading them that distinct characters are speaking. The analysis tells us the same thing: that the greatest authors of the 19th century, and great authors in general, are able to create characters whose word prints reflect differences, and in some cases similarities.

This is James Fenimore Cooper.

And lastly Mark Twain—Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn actually have some similarities in the way that they speak.

Character Distinction

But overall, we’re concerned with examining the question of: how distinct are these characters? How good can an author be at creating characters with different word prints within their own book. Because we know that authors have their own word prints, but now we’re seeing that characters have their own as well.

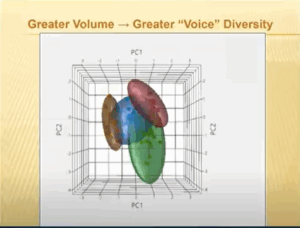

The way that we measure this—the distinctness of the characters and that overall dispersion of differences and/or similarities—is by using an extra principal component.

If we can plot them in three dimensions, then you can see that the points occupied in the space form sort of this ellipsoid, right? Like a football-looking thing in three dimensions. The larger that football, the larger that ellipsoid, the more different the characters are within an author’s novel. So the closer these points are together, the more similar these characters are in terms of their speaking styles. The further apart they are, the larger that volume is, and the more different that these characters are.

And so that kind of opens up questions that we can now examine, and this is going to be important for when we examine texts other than those written by these 19th-century authors.

How Does The Book of Mormon Fit Into This?

Larry Bassist: Thank you, Scout. My name is Larry Bassist. I’m going to talk about an LDS question here. How does the Book of Mormon fit into this?

If you notice—I’m just going to go back real quick—those four different blobs there, or ellipsoids, are close to each other. They’re somewhat similar. That’s interesting.

How does the Book of Mormon square with all of that? Do the speakers in the Book of Mormon have different voices? Different wordprints? Like the characters of these great 19th-century novelists? Or are the characters in the Book of Mormon just all packed together with a similar voiceprint? And how do they compare? Could Joseph Smith have just written the Book of Mormon as a novel?

Oh my—look at that.

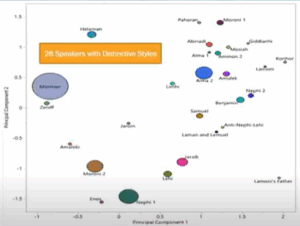

The characters in the Book of Mormon are vastly different from each other. In fact, here we have 28 speakers with distinctive styles.

Not only that—remember Scout talked about how big those ellipsoids are is a measure of the distribution of the speakers’ voices?

How big is this distribution, compared to the 19th-century novelists—is it smaller than, about the same as, or what?

Variation

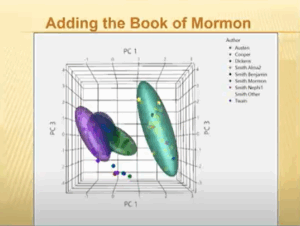

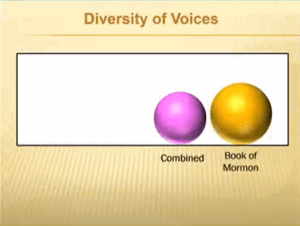

The one on the right is the Book of Mormon. Look at that. It’s huge compared to those 19th-century novelists combined. And notice: the 19th-century novelists on the left are again kind of all packed together. Those are these novels’ fictional characters, in the Book of Mormon, there’s something different about those characters.

Now, this is just the first three principal components, but this is a multi-dimensional problem—many dimensions. So the volumes here of these ellipsoids only account for a small fraction of the overall variation in multiple dimensions.

If we measure that variation in the multiple dimensions and use it to depict the differences between the different authors, we get this for the 19th-century authors:

Cooper has the smallest variation between speakers, whereas Dickens has a lot larger variation between speakers. Some people refer to Dickens as one of the greatest character developers in literature.

Now, what if we put all four of these together?

We had eight books, four authors, and 104 different total characters. And the volume of that, relatively, is bigger—as you would expect.

Where does the Book of Mormon compare to this?

Conclusions

Whoa. That’s astounding!

One book has more character diversity in only 28 speakers—compared to eight books by four talented authors with 104 characters.

That’s gotta trigger some thoughts.

So what conclusions can we make from this?

- Great literary talents can create characters with different wordprints.

- The speakers in the Book of Mormon have different wordprints.

- But the diversity of style in the Book of Mormon indicates not just a single author, but multiple authors.

But how in the world did they make such a great diversity of style? Maybe it’s because they’re talking about real people—and not just fictional characters.

Virtual Reality App

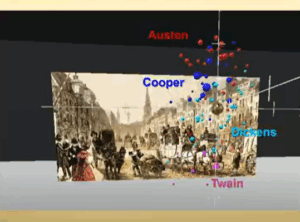

Justin Mott: My name is Justin Mott. If you thought all of that data was cool, you’re in for a ride next. As Dr. Fields previously mentioned, more powerful computers and technologies have made it possible for us to have much more effective and accessible visualizations of this data.

One way we can do this is by stepping into the Book of Mormon through virtual reality.

We’ve been able to create an app that displays this data in a 3D graph in a virtual environment—with a Liahona that can guide you around the different elements of it. It allows us to compare, in a little bit different way, the 19th-century novelists to the speakers in the Book of Mormon through the data views that are in there.

You’ll see some screenshots of this app in just a second. The sizes of the spheres indicate the number of words used by each speaker or character. And the separation of them in the 3D graph indicates the difference in diversity of the styles between the way these characters, or people, speak.

Here’s a shot of the novelists: Jane Austen, Dickens, Cooper, and Mark Twain. They’re kind of separated on this vertical plane. You can see that despite distinct differences, there are still similarities between the characters written by these authors.

Authors

Compared to when we look at the Book of Mormon–and you can see the massive spread that occurs now. It really, truly shows us that not only would Joseph Smith have to have been on the same level as Charles Dickens or these other people—but a substantially greater author to have written this diversity of speakers.

The other cool thing is that you can try this VR app out here today. We’ll be running the demo after our presentation, just outside these doors. I’ll be there with our headset and helping anyone who wants to try it out.

This is cool—but it’s so much cooler when you can actually see it inside the app.

Thank you.

Paul Fields: Thank you, Justin. That’s great diversity of speakers within the Book of Mormon, from Abinadi to Zeniff. Of course, Mormon has the biggest sphere.

Does the Book of Mormon look like a 19th-century novel to you?

If you reject the assertion that it was a translation by the gift and power of God, then you’d also have to say that Joseph Smith was the greatest novelist of the 19th century. But no one who knew him would agree with you.

Addressing Plagiarism Claims

The issue that always seems to be coming up is: well, Joseph Smith wasn’t a great talent, but he just plagiarized these works.

So in answer to that question, what we’ve done is we’ve looked at the pseudo-biblical corpus—all of the texts that were available at that time from about 1750 to 1850 in the United States written in a pseudo-biblical style. Looking at this—well, it sounds like a “could have been” problem.

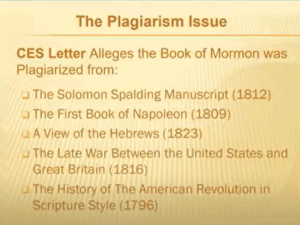

All right, if we’re going to address plagiarism, then—as alleged by the infamous CES Letter—we’ll have to take a look at the Solomon Spalding manuscript, The First Book of Napoleon, View of the Hebrews, The War Between the United States and Great Britain, and A History of the American Revolution in Scriptural Style.

Those are the ones that have been most strongly alleged as plagiarism sources for Joseph Smith.

Technology helps us to easily address that question. We looked at 30 different plagiarism software packages that are readily available. We tested them against what we call positive and negative controls–where we knew there was plagiarism–would it detect it?– and where we knew there was not plagiarism–a negative control–would it say if there was or wasn’t?

Readily Available Software

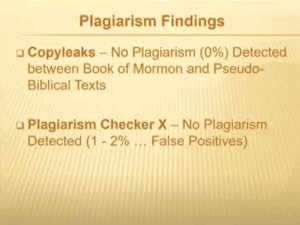

Looking at positive and negative controls we narrowed those 30 pieces of software down to the 2 who did the very best–who didn’t make mistakes, either positive or negative mistakes. And those were: Copyleaks and Plagiarism Checker X. They are readily available. They’re free and you can download them yourself and do the same tests that we have done.

Copyleaks said that comparing the Book of Mormon to those other pseudo-biblical texts—zero detection of plagiarism. Plagiarism Checker X said there was no plagiarism. It said, maybe one or two false positives where there could have been some, but we knew that they weren’t real.

You don’t have to take our word for it. For something to be scientific it must be replicable. The works that were allegedly referred to in the CES letter have never been replicated. You can replicate this yourself. All you have to do is download that software. And if you want our copies of those texts, we’ll be happy to give them to you for free.

Measuring Influence with Consensus Networks

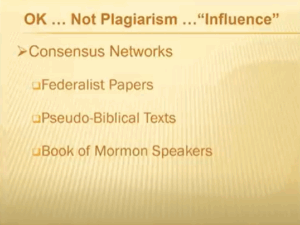

After we dismiss plagiarism, people say, “Well, it wasn’t plagiarism, but it was influence; Joseph Smith was influenced by these other texts.”

I don’t know what that means. Do you know what that means? What does influence mean? Anything that you’ve experienced in your life, in some way, influences you. So how do you measure influence?

Well, what we have developed are called consensus networks to look at the structure inside of a text. And what we’ve done is we’ve looked at the Federalist Papers, which we referred to earlier. We took a look at the pseudo-biblical texts, and we looked at the Book of Mormon speakers.

I’d like to introduce you to Alex Lyman, who’s going to be with us via Zoom from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Alex, tell us about influence.

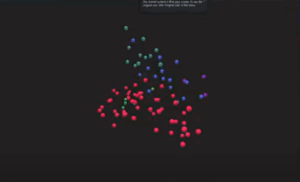

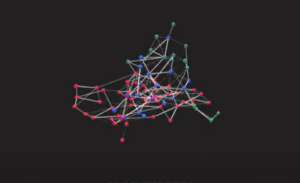

Alex Lyman: Thank you. So, influence is obviously a nebulous claim to be able to substantiate. But we developed a 3D graphing visualization so we can rank different texts by their similarities to one another. The idea that if one text influenced another, they should be more similar than two texts that did not influence one another. I’m going to be walking us through a number of these networks to show our findings.

Federalist Papers

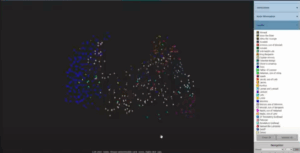

This is a three-dimensional representation of the Federalist Papers. Each of these spheres is one of the Federalist Papers and their coloring is given by the traditional author that was ascribed to each of those before that famous 1960 study by Mosteller and Wallace. And as you can see we have these dots sort of hovering in three-dimensional space.

They have connections between them, and in the bottom right hand corner you can turn those connections on or leave them off for a clearer view. [Shown is a dynamic, interactive computer model].

Now, because I’m on a two-dimensional screen, I’m going to flatten this network down into two dimensions.

And as you can see, there is a perfect separation of each of the authors of the Federalist Papers. So, in the bottom left-hand sort of third, we have all of Hamilton’s Federalist Papers. In the bottom right area, we have all the ones that John Jay wrote. And then, up at the top of the pyramid—so to speak—we have all of the ones written by both Madison and the ones that were of disputed authorship.

Our software shows the same findings that Mosteller and Wallace had—that Madison was the one who wrote these Federalist Papers.

Proof of Concept

And so, this is convincing proof of concept that our software works—that we can group texts by their authors, taking into account both the style of the authors and the topics they’re covering.

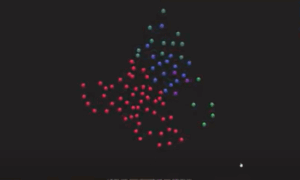

Now, as Dr. Fields mentioned, we were able to apply this to the pseudo-biblical texts that many detractors of the Church have alleged that Joseph Smith may have copied from.

Once again, it’s a three-dimensional representation that I’ll smash down into two dimensions. And when we smash it down into two dimensions—and I just think this is fantastic—we get an incredibly clear separation between, on the left, the Book of Mormon, and on the right, these other five texts that are alleged sources of influence for the Book of Mormon.

Just a simple linear classifier—if I just draw a line through the middle—this simple line classifies, with over 98% accuracy, whether any given text belongs to the Book of Mormon or to these other pseudo-biblical documents.

The Most Exciting Thing

And so, what we’ve been able to show here is, very convincingly, that these texts are much more similar to one another than they are to the Book of Mormon. And any influence that would exist does not extend to Joseph Smith and his writing of the Book of Mormon.

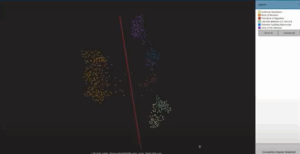

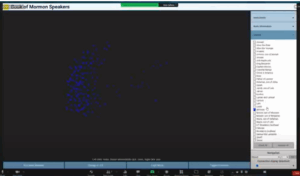

Now, the most exciting thing I think that we’ve been able to do with this technology comes—or is sort of in concert—with our effort to look at Book of Mormon voices.

And so, in this very complex-looking network that you have in front of you, each of these dots represents about a thousand words spoken by a given speaker. So, somebody went through, divvied up every single word in the Book of Mormon, and assigned who wrote it.

You’ll see on the left-hand side, we have a very large blue cloud, and that is Mormon—he’s the speaker of those. Obviously, we know that it’s the Book of Mormon, and he’s responsible for penning quite a bit of it. But the spatial relationships in here are very interesting. I’m going to walk us through a few examples of what this can show you—both as a study aid and as a faith-promoting tool.

Walk-Through of the Tool

On the right-hand side, there’s an interactive legend where you can uncheck the different boxes and make those dots appear or disappear.

So the first example is, like I said, Mormon—who wrote a lot of the Book of Mormon–most of his text is clumped in one area and then sort of spreading off to the side.

And then his son follows a very similar pattern, which is something that we would expect.

Another example that I found very compelling was: if we go through and take all of the heavenly beings, I guess—so all of the angels, Christ in His visit to the Americas, the Godhead—whenever they appear, and the Godhead as quoted from the Old Testament—they all appear in this sort of area along the far side of the graph, opposite Mormon’s writing.

And Isaiah—who Nephi makes special mention that he testifies of Christ; Christ also in America talks about the worth of Isaiah’s prophecies—Isaiah is just hooked in on this far other end. [He references the far right-lower dots].

And so, when we see this network, on the one hand we have Mormon, who’s generally talking about more secular things. He’s talking about the wars—and obviously there’s a spirituality in everything he writes—but the purely spiritual tends to be on one side, and the more secular tends to be on the other side.

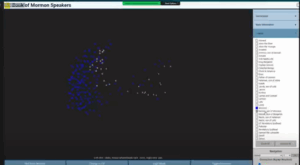

The Story of Lehi

Another example that I find compelling is the story we see at the beginning of the Book of Mormon.

We start with Lehi—this is the space that his words occupy.

Then we can add in his son Nephi,

his [sons] Laman and Lemuel, Jacob,

and then finally his grandson Enos.

And once again, they tend to occupy the exact same space.

We know that this story of the first many chapters of the Book of Mormon—Nephi and his brothers, I guess—really describe both spiritual prophecies they have and the goings-on of their lives.

And so, we would expect them to be in the middle, as sort of a bridge between the more secular on the left and the more spiritual on the right.

Potentially Unexpected Connections

And what is interesting about these networks—or part of their value—is that they can provide potentially unexpected connections and show us things that we wouldn’t maybe even think of reading through the Book of Mormon for ourselves.

One that I discovered just this last week, that I found very interesting, is: if you add in Abinadi—a prophet who prophesied, sort of, destruction on people, and it went poorly for him; Samuel the Lamanite—another prophet who preached repentance and it did not go very well for him (they threw rocks and arrows at him); and then Nephi, Helaman’s son, who prophesies from a tower and ends up being jailed and falsely accused of murder because of his prophecy—they also occupy a space.

And while the distinction of prophets who weren’t received very well isn’t a distinction that I would make, this network does make it—and groups them in a very compelling fashion.

A final example that I just wanted to share that I found is very fun: when you’re interacting with this graph, you can click on any node or document to view its connections— which documents are most similar to it.

Faith-Promoting Experiences

And if we click on the words of Lamoni, the two dots that it connects to are Ammon and Lamoni’s dad. And I just thought that was very impressive—that our algorithm pulled that out, that Lamoni, Lamoni’s dad, and Ammon had a little story together.

This has been a wonderful tool that we’ve developed, and it has fantastic applications both as a study tool that you can use, and also as a faith-promoting experience showing the diversity of voices, topics, and styles in the Book of Mormon. Thank you.

Paul Fields: Thank you, Alex.

Our statistical analysis can show the distinctions between the speakers, but it also shows that there is no possible influence between the pseudo-biblical texts and the creation of the Book of Mormon. And even further, the consistencies within the text are so strong, they could not possibly have been created by something as nebulous as “influence.”

Resource Access

Now, if you’ll get out your phone and take a snapshot of those QR codes, you can access on your phones—or take the URLs home—and on your computer, you can see those consensus networks.

This is the Federalist Papers.

This is the pseudo-biblical text.

And this is the Book of Mormon speakers.

So, we find at least 28 styles in the Book of Mormon—28 voices. We can see the complex structure of this text through the networks.

It would have been very difficult for one writer to have kept track of those 28 different styles and used them consistently and congruently throughout all 268,000 words in the Book of Mormon.

Let’s pull up the website.

Matt Roper

Hi, I’m Matt Roper, and I’ve been helping with some of the content for the Voices website here. [Interactive website is demonstrated]. Here on the main page, you can see we have different resources.

If you scroll down and go over to the right—you see that “Did You Know?” What we want to do is we want to look at the different speakers or writers in the Book of Mormon, and we look at their voices. We want to see: do their words—the way that they use particular words and so forth—does that provide insight into each of these speakers? And is there something we can learn from that about what they were like? What was of importance to them?

We have what we call “cameos” for each of the speakers and writers in the Book of Mormon. And at the top of the cameo for each one, sometimes we have more than one cameo for the different speakers—at the top of these cameos it might say something like:

“Amulek is the only speaker in the Book of Mormon to use the word charitable.”

Which is kind of interesting. You think about what Amulek went through.

“Mormon and his son Moroni have the most correlating speech patterns of all speakers.”

They’re both father and son, they were very close, and so it doesn’t surprise you.

“Nearly all of Alma’s sermons reference his experience with the angel in his conversion.”

Nature of Evidence

Ryan talks a little bit about how you have this multifaceted nature of evidence for things like Alma 36, and Alma’s experience with the angel. One of the things we also find is that nearly all of Alma’s sermons echo this experience in the words that he uses to teach people. It’s something that stayed with him throughout his life. It’s very significant.

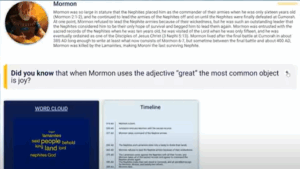

Scroll back up to the top of the main page and go to “Speakers.” If you then scroll down to “Mormon,” and this is just one example–I think for Mormon, we’re actually going to have several–here you have a little biographical statement with the timeline—when he lived and so forth. But go to where it says “Did You Know?” and you see:

“Did you know that when Mormon uses the adjective great, the most common object is joy?”

Now this is interesting. This is an example of a cameo that we have for Mormon where it goes through, talks just briefly about his life, and some of the highlights of what we found about words that he uses and what that suggests about Mormon—his perspective and his interests.

Great

And if you look at words—if you break down Mormon’s words—you look at how he uses the term great. And if you notice the term great, which is used, I think, 274 times in the Book of Mormon—but if you look at how it’s used, and what is the object of great when Mormon talks about this, the thing that he refers to the most is great joy, which is kind of interesting.

If you think about Mormon—you think about what he went through with his life, and all the stuff that he had to go through with what was going on with his people, he witnessed their gradual—well, fairly rapid—descent into destruction, their wickedness, all the things that he saw in war and so forth, and what is he thinking about? He thinks about the great joy that the gospel of Jesus Christ offers to people.

And this is the person who is the primary abridger and historian of the Book of Mormon, who wants us to get the message of what is important. And Mormon focuses on the great joy. With all that he could have said about other things, that’s what he wants to get across. And this comes across in the words that he uses.

So this is one example of how we can focus on what a speaker says, and what those words, and the peculiar word usage to each individual speaker or writer, can tell us about them. What was of interest to them in their message. Thank you.

Paul Smith: My name is Paul Smith. I’ll be introducing some tools we have for each speaker.

Helaman

If we go to the Helaman page, we’ll start off with the biography here. If you just read through it real quick, you’ll notice that it is not a comprehensive description of Helaman’s life, but rather, it’s more of a screenshot—like a moment in the life of Helaman that can help us understand his character and life a little bit better. And it helps excite the audience—you—to go and read more about Helaman in the Book of Mormon.

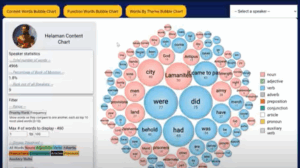

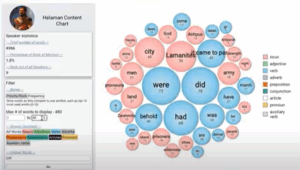

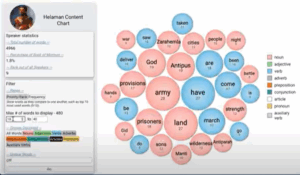

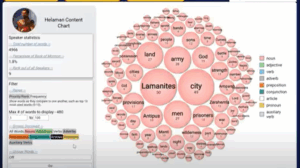

And if you scroll down a little bit, you’ll see this word cloud here. This word cloud contains the top 10 content words spoken by Helaman. And you can see at a glance, in this word cloud, the primary message Helaman is trying to get across.

You can take those words and look for them as you read about Helaman in the Book of Mormon as a kind of marker to help you enhance your study.

Then to the side of the word cloud, we have this mini-timeline that shows some of the key events in the life of Helaman—and our best guess as to what date that occurred in.

Now, in Helaman’s case you’ll see that Helaman was very likely born in the land of Helam and was a little child when his people were enslaved by the Lamanites, and then miraculously delivered by the power of God.

Our Goal

That is something that would have had a great impact on Helaman’s life, but we don’t really consider that when we read the Book of Mormon because Helaman isn’t mentioned until he’s an adult in about 74 BC.

So these context clues, we sometimes lose track of or lose sight of when we read the Book of Mormon. But this timeline can help us understand a little bit more who Helaman was as a person.

And that’s kind of our goal with all these tools—to help us understand not only the different people in the Book of Mormon, but also the different messages they have to offer us.

Other Tools

Adam Ryan: Hey guys, I’m Adam Ryan. I’m going to walk you through some of these tools that we’ve created to bring these people to life—because obviously there’s so many insights and discoveries that we can make, and we want to make those more available.

We’re going to start with the timelines. And it’s just going to display simple visuals to help bring these people to life. And there’s a little box just showing the lifespan of Helaman in the context of the whole Book of Mormon, starting at about 650 BC to 425 AD—when his life takes place.

We have a connections diagram of how these speakers are related. Over the top, the black ones are going to be the language connections—and this data was pulled from the data that Alex was showing earlier with that huge 3D graphic. And on the bottom are the social connections. Alma the Younger—his son was Helaman. And then Helaman’s grandson was Nephi, because it was Helaman, Helaman, and Nephi, right? And these are just simple visuals to help these connections and relationships be more easy for us to picture. These boxes at the bottom are going to show those same things—just in text—to make it all super easy to understand.

All right, now we’re going to take a closer look at the word cloud.

The Word Cloud

This is a display of the words that all these speakers use. And it’s just a really quick way to see: what did they talk about?

On the top are the different types of charts. Right now, the default is just the content words—your nouns and verbs—to see what topics they are saying.

The function words chart is your “does,” your “ands,” your “thats.” And we’re going to go back to the content words to look at how this works—which is awesome.

So right now it’s displaying the top 1 to 100 words for Helaman—of his content words. And you can adjust that to where you want.

Let’s set the top to 40. And it’s automatically going to cut down those lower words.

And let’s set the bottom to 10. Let’s get rid of the first few—so say you want what he talks about, but not like the first few words. And there it is—super, super easy.

And you can toggle over to frequency where you can do the same thing but order it by how many times the word is used.

The Point

And the point of this—you know, there’s probably a lot of irrelevant things we could find, like, “Oh, why would we need to know that?” Right? But the discoveries that we can find just with these simple tools are going to be so, so great for us.

Going back to the priority rank one— you can change which words you want.

We’re going to turn off verbs—and these are all the nouns that Helaman uses. And as you can see, they’re going to match somewhat he word cloud that Paul was just talking about:

“Lamanites,” “God,” “city,” “land.”

These are the things he talks about.

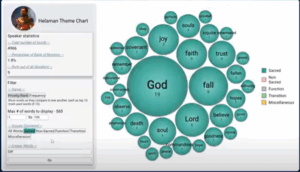

You can also look at the words by theme in a bubble chart. What we’ve done is just categorized all the words by: what kind of word are they? What are they talking about? What’s their theme? And we’re going to turn off non-sacred words. We’re going to turn off function words, as well as transition and miscellaneous.

A Voice

So these are the words that we’ve deemed as sacred words—or spiritual words—that Helaman talks about. Obviously he’s involved in the war—he’s going to be talking a lot about secular, war things. But he’s still a spiritual leader. And we can see that here by his word choice. He talks about God, talks about faith and joy. And it’s just so easy for us to know that this is what he’s talking about.

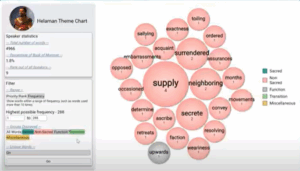

If you do “Unique Words,” down to the bottom—these are all the words that are only used by Helaman. So that kind of gives you an idea of what his uniqueness as a speaker. What are the things he talks about?

And of course you’re going to have “supply,” “neighboring,” “surrendered”—words that are involved with war.

I’d like to point out: exactness is there at the top. If you remember, the stripling warriors followed the orders with exactness—and that’s Helaman. He’s the only person who ever says that.

So these tools are just a great way for us to visualize who these speakers are—give them a voice—make them real to us.

Conclusion

Paul Fields: Thank you, Adam.

The Book of Mormon speakers are not fictional characters. They’re real. They’re real people.

The most common word in the Book of Mormon is the—of course, that’s the most common word in the English language. But interestingly, the word unto is used very frequently throughout the Book of Mormon by all of the speakers. It’s the unifying theme of the Book of Mormon in phrases such as: say unto you, come unto the Lord, come unto the Son, come unto God, come unto Christ.

Truly, the Book of Mormon is another testimony of Jesus Christ.

The Lord’s words come unto us through the Book of Mormon—inviting us to come unto Him, and directing us to do as He did and give service unto His children.

A testament of Jesus Christ.

We found 28 witnesses in the Book of Mormon—28 testimonies. May we all hear their real voices. May we take their messages—as we can see through this website—into our hearts, and into our minds, and into our lives. In our every word and action, raise our voice in witness—in the testimony of Jesus Christ.

As living disciples, may we say with Mormon:

“I am a disciple of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. I have been called by Him to declare His word unto His people, that they might have eternal life.”

We testify that He lives. That He is the path to salvation and exaltation in the Kingdom of God. And to this we bear our humble witness, in His holy name—Jesus the Christ, our Lord and Savior. Amen.