Ma”We mean to elect him”: Electioneer Experiences during Joseph Smith’s 1844 presidential campaign

“We Mean to Elect Him.” Electioneer Experiences During Joseph Smith’s 1844 Presidential Campaign

Derek Sainsbury

August 2021

Summary

Derek Sainsbury explores the religious and political motivations behind Joseph Smith’s unprecedented run for U.S. president. The campaign was ultimately doomed by Smith’s assassination. However, it left a lasting legacy in the westward migration and political structure of early Utah.

Introduction

Scott Gordon: Eric has worked for 26 years in the Seminaries and Institute of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Currently, he’s an instructor in the Church History and Doctrine Department at Brigham Young University. He holds a PhD in American History from the University of Utah. He’s the author of Storming the Nation and many other things. And so with that, I’m going to turn the time over to Derek Sainsbury.

Presentation

Derek Sainsbury: Thank you. I’m really happy to follow right after Rebecca. There’s a bit of a pattern there that my work has, but I’ve only got one woman. So we’ll look at that.

“We mean to elect him,” penned Apostle Willard Richards in a letter to the Saints’ influential ally John Arlington Bennett in Long Island. The date was June 20, 1844. The “him” was Joseph Smith, and the election was for President of the United States.

On behalf of Joseph, Richards was responding to Bennett’s recent letter. He wrote that Joseph’s campaign, as far as politics go, was a wild goose chase. Richards wrote from a Nauvoo that was in chaos. The Nauvoo Expositor, with distorted half-truths and acerbic accusations, had exposed Nauvoo’s two great secrets: plural marriage and the Council of Fifty.

When Richards wrote to Bennett, Joseph had already ordered the destruction of the Expositor press, been arrested twice, released twice, and had declared martial law as mobs began to circle. Despite all of this, Richards was adamant that they were doubling down on the election. “We mean to elect him, and nothing shall be wanting on our part to accomplish it.” And why? “Because we are fully satisfied that this is the best or only method of saving our free institutions from a total overthrow.”

For the Saints, the unfortunate but hauntingly familiar storm gathering around Nauvoo only highlighted why Joseph’s campaign was necessary. Instead, a week later, Joseph’s bullet-ridden body marked him as the first assassinated presidential candidate in United States history.

Why Did Joseph Run? Was He a Serious Contender?

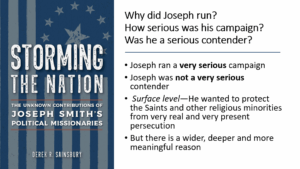

So why did Joseph run for president? How serious was his campaign? Was he a serious contender before his death—or if he had lived?

Several articles, books, chapters, and small treatises have offered a wide variety of answers. My book Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries was released last year. It is the first academic book-length treatment of the election and the election years. It was followed this year by Spencer McBride’s book Joseph Smith for President.

Due to the publication of the Council of Fifty minutes in 2016, we both had the advantage of knowing what Church leaders’ private deliberations were about the campaign. The minutes, for me, only strengthened what my dissertation earlier that year had argued and what our books have concluded. Joseph Smith ran a very serious campaign for president, but he was not a very serious contender to win.

Or, as Bennett wrote to Richards, “If you can, by any supernatural means, elect Brother Joseph Smith, I have no doubt he would govern the people in righteousness. But I can see no natural means by which he has even the slightest chance of receiving the votes of one state.”

Joseph, Church leaders, and their hundreds of electioneer missionaries sincerely believed a heavenly influence could—maybe would—pave the way to victory. Historically speaking, absent such an influence, the prophet’s chances were negligible. So why did he run then?

The most succinct, surface-level answer is that Joseph wanted to protect the Latter-Day Saints and other religious minorities from very real and very present persecution.

Understanding the Campaign and it’s Roots

The wider, deeper, and more meaningful answer is more complex. But it is crucial to understanding the campaign and the beliefs and actions of Church leaders and their electioneer missionaries during it.

This deeper understanding has metaphorical roots, a trunk, and branches of fruit.

As the trunk, the campaign was the prophet’s practical application of two revelatory roots to his contingent realities that he hoped would bring the desired fruit of government protection.

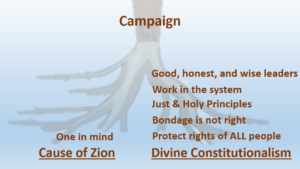

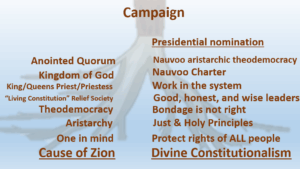

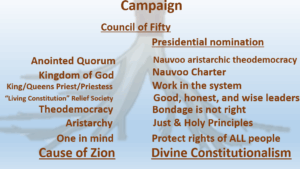

The Cause of Zion

The first root was the cause of Zion.

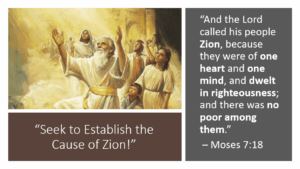

New scripture defined Zion as a society whose inhabitants were one in mind—a political governing component. One in heart—a social connecting component. Dwelt in righteousness—a religious spiritual component. And there were no poor among them—an economic component.

Other revelations required the Saints to gather, build a temple city, and establish Zion with all her components in order to prepare for Christ’s millennial reign and return.

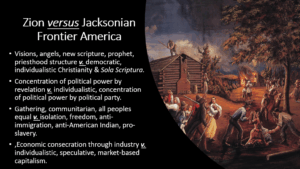

However, each component conflicted with contemporary Americans, especially on the frontier where God had told the Saints to build. Visions, new scripture, and revelations coupled with gathering under priesthood authority seemed blasphemous and despotic to individualistic and democratic Protestant America that preached sola scriptura.

Collective power in the name of religion, untethered to political parties, was anathema in an age of individual liberty and partisan party politics. Building a community that declared all peoples as equals collided with frontier individuals seeking freedom and isolation, and who viewed immigrants, American Indians, and Blacks as lesser beings. Economic consecrated cooperation challenged individualistic, speculative, market-based capitalism.

Tragically, conflicting beliefs on the frontier often meant vigilante violence. Mobs persecuted and exiled the Saints first from Jackson County and then from the entire state of Missouri.

As Joseph pled with the Lord, he received revelations that included heavenly truths and instructions to interact with the government and Constitution of the United States. That the Lord said he instituted, quote, “by the hands of wise men who He had raised for this very purpose.”

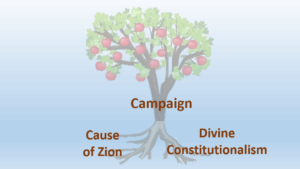

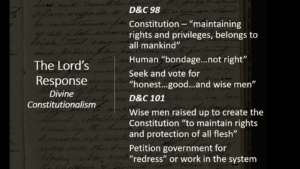

Divine Constitutionalism

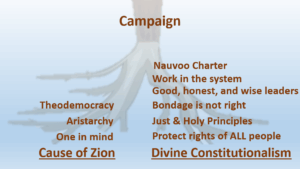

These truths and instructions, which I will label divine constitutionalism, became the second revelatory root of the campaign.

Joseph learned that the Constitution should be maintained for the rights and protection of all flesh, according to just and holy principles. Thus it was not right that any man should be in bondage one to another.

Further, the Lord explained: when the wicked rule, the people mourn; wherefore, honest men and wise men, the Lord instructed, should be sought for diligently, and good men and wise men ye should seek to uphold.

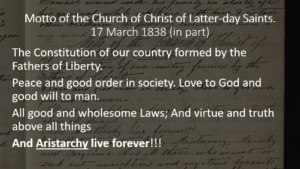

Aristarchy

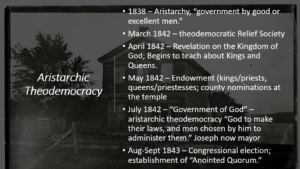

Thus began Joseph’s articulation of aristarchy. A contemporary term defined as a body of good men in power or government by excellent men.

In an official Church motto published just six months before the extermination order, Joseph declared, in part:

“The Constitution of our country, formed by the Fathers of Liberty; peace and good order in society; love to God and goodwill to men; all good and wholesome laws; and virtue and truth above all things; and aristarchy, live forever.”

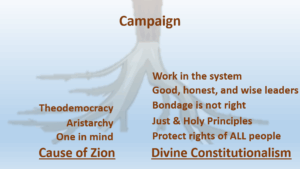

Besides aristarchy, this motto spoke of good, wholesome, virtuous, truthful, and godly government. Something Joseph would later call theo-democracy. Government where, “God and the people hold the power to conduct the affairs of men in righteousness for the benefit of all.”

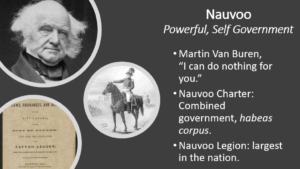

Additionally, the Lord commanded the Saints to work within the system to seek redress from the government. They were unsuccessful in all their attempts. This includes President Martin Van Buren, who famously told the Prophet to his face, “Your cause is just, but I can do nothing for you.”

Joseph believed that politics and government had become corrupt and broken and would not protect them.

Zion in Nauvoo needed protection from correct and powerful self-government to avoid another Missouri. The Saints fortuitously received this in the Nauvoo Charter and Legion.

The two revelatory roots — Zion’s unity governance and defending the rights of all using divine constitutionalism — continued to develop in the contingent context of the Nauvoo era.

Theodemocracy

In 1842 and 1843, Joseph created a theo-democratic Relief Society, revealed temple anointings of kings and queens, priests and priestesses, taught a future theocracy, and nominated at the temple site the correct men for elected office.

For example, Joseph was elected mayor, and Hyrum and the Apostles were elected to the city council.

These were all steps that led to establishing aristarchic theo-democracy — and consequently, Joseph’s presidential campaign and the Council of Fifty.

Confrontation Inside and Outside the Church

Theo-democratic Zion in Nauvoo created confrontation from inside and outside the Church.

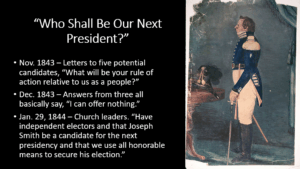

Looking for protection, Joseph wrote to the five potential presidential candidates of 1844. Quote, “What will be your rule of action relative to us as a people should fortune favor your ascension to the chief magistracy?”

None offered help.

Therefore, on the 29th of January, 1844, Church leaders nominated Joseph Smith for President. They committed to, quote, “use all honorable means to secure his election.” This included having independent electors for the Electoral College, creating the infrastructure necessary to translate possible states won into proper electoral votes, thus revealing a serious campaign.

Joseph Smith’s Election Plan

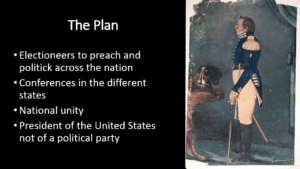

Joseph’s enthusiastic response to his candidacy exhibited his sincere intent. He would send missionaries, “throughout the land to electioneer and make stump speeches and advocate for the Mormon religion.”

The electioneers would advocate for a president independent of political party. For a longed-after national unity that realistically had only existed partially under George Washington.

The new presidential candidate boasted that, “there is oratory enough in the church to carry me into the presidential chair on the first slide.”

These were resolute words, concrete plans, and idyllic ideas outlining a very serious campaign. But only if the ideas, words, and plans were put into action.

The Election Plan in Action

Over the next five months, they were. The two intertwined roots — unifying Zion government and divine constitutionalism to protect all people — fused into the Prophet’s campaign.

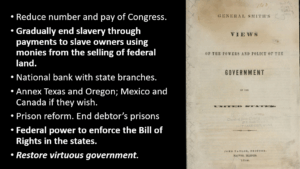

Joseph published a political pamphlet named General Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States. I will refer to it as Views.

Scholars have studied how the pamphlet’s ideas fit in the wider political context and the circumstances leading to Joseph advocating for them. However, his proposals also came from these two revelatory roots.

Here are just two examples:

Joseph called for the end of slavery through gradual remunerated emancipation, using monies from the sale of public lands. In the revelatory roots, Zion was open to everyone. The rights of the Constitution belonged to all — including Black flesh — for bondage was not right.

The Prophet’s chief concern was that the U.S. Constitution and government had failed his people. At that time, the Constitution only protected the Bill of Rights at the federal level, not within the individual states. This had allowed for the tragedy of Missouri.

“I am the greatest advocate of the Constitution,” Joseph pronounced, “but it is not broad enough to cover the full ground.”

Joseph proposed that the president have power to protect the rights of all people within the states. Joseph again was returning to the revelation that the Constitution was to protect the rights of all peoples. Including unpopular minorities like the Latter-day Saints.

One other part was that he believed that the government had fallen into apostasy. Just as Christianity had fallen into apostasy. He saw his campaign as restorative. He asked the American people to cheerfully help him restore the nation’s unity.

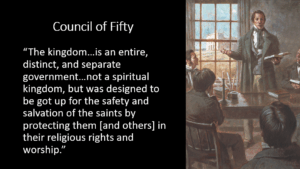

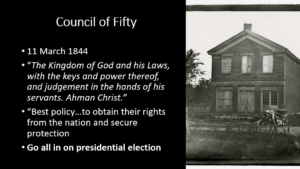

The Council of Fifty

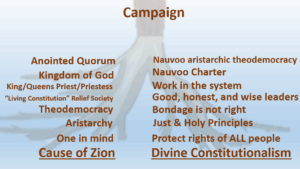

Joseph established the Council of Fifty on March 11, 1844. It was the final fusion of the revelatory roots of Zion governance and divine constitutionalism.

Considered separate from the Church, this Council of Fifty was the literal political Kingdom of God. Established to protect Zion and the rights of all and prepare to eventually govern on the earth during the Second Coming and into the Millennium.

The revelatory title of the confidential council was “The Kingdom of God and His Laws with Keys and Powers Thereof and Judgment in the Hands of His Servants. Ahman Christ.” It was the ultimate expression of aristarchic theo-democracy.

Joseph selected by revelation good, honest, and wise men — who were mostly anointed kings, or aristarchy — to govern as a living constitution that counseled together and with heaven to find God’s will, accept it, and then execute it on behalf of all people, or theo-democracy.

The Council explored several options to defend Zion before settling on the election as, “the easiest and best way to accomplish the object in view.”

“All who could should go electioneering,” Joseph announced. They would, “have more power and might, and more means than they have ever had before, a hundred fold.”

Willard Richards wrote similar sentiments about the missionaries to a distant church leader. “If God goes with them, who can withstand their influence?”

Speakers at the April 1844 General Conference strongly hinted at the ideas being shared in the Council of Fifty, which were wrapping church and state closer together. In the context of repeated teachings of a literal Kingdom of God, and their Prophet energetically running for President, the Saints came to understand they were offering the nation religious and political salvation.

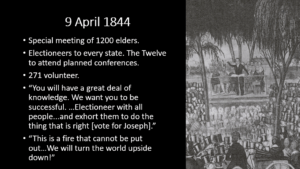

Electioneering Missionaries

The missionaries called on the fourth and final day of the conference would be the messengers. Twelve hundred men gathered and learned that the Church was sending electioneering missionaries to every state, preaching the restored gospel and politicking for Joseph. The Apostles would attend scheduled conferences throughout the states to promote both objectives. At these and other meetings, assigned State Presidents would organize the electioneers and choose state electors for the Electoral College.

The rhetoric in the meeting was direct, enthusiastic, and confident. For example, Hyrum Smith said: “You will have a great deal of knowledge. We want you to be successful electioneers with all the people, and exhort them to do the right thing. [that is, vote for Joseph].”

Brigham Young bellowed, “This is a fire that cannot be put out! We will turn the world upside down!”

Young then called for volunteers. Two hundred seventy-one immediately signed up. The following week, Nauvoo newspapers published a list of missionaries, now numbering 336, with their respective assignments.

How They Were Called

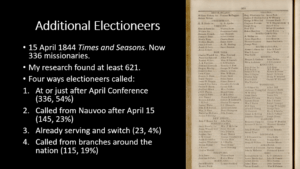

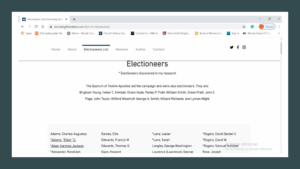

In my decade-plus of over 5,000 sources, I have found that there were a total of at least 621 electioneers. This does not include the 12 Apostles. Almost doubling the number we believed had served before.

They were called in four different ways:

- The 336 (or 54%) were called at or just after the April Conference.

- 145 (or 23%) were called from Nauvoo after April 15th.

- 23 of them (or 4%) were already serving missions and switched to electioneering.

- And finally, 115 (or 19%) were called in the conferences where local stakes called in the conferences throughout the nation.

The cadre of electioneers was the largest missionary effort in Joseph’s lifetime by far. Another strong indication that the campaign was serious. In fact, the next time 621 missionaries were in the field was 1905 — 60 years later. Still today, there has never been a missionary group as proportionately large relative to total membership.

So who were these electioneers?

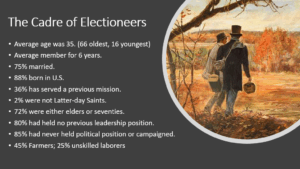

- Their average age was 35. Samuel Bent, 66, was the oldest, and Charles H. Bassett, at 16, was the youngest.

- Their average length of membership in the 14-year-old Church was six years. Ezra Thayer was among the very first. Breed Cyril was baptized during the campaign, ordained, and immediately became an electioneer.

- Three-quarters of the missionaries were married.

- 88% were born in the United States.

- 2% were not Latter-day Saints.

- Strikingly, only 36% had served a prior mission.

- 72% were elders or seventies.

- 80% had never held a leadership position in the Church.

- Despite living in the most partisan era of American history, 85% had never held any political or elected position. Nor had they campaigned in previous elections.

- Economically, 45% were farmers and a quarter were unskilled laborers.

- Most had experienced the hell of Missouri and the coldness of the government’s response to their plea of redress.

Reversing Policy

Every man possible was encouraged to go. This reversed a recent policy of only sending out missionaries with settled family and economic situations.

This meant that some, like James C. Snow and Alfred Cordon, left their families without even a pound of flour. Widowers left children in charge of others, or even their oldest children. Some even sold family heirlooms to finance the mission.

Despite the sacrifices, they left understanding the urgency of their mission.

Electioneer John D. Lee, tearfully leaving his family, expressed:

“The importance of my mission came to mind, banishing grief and anguish. I felt highly honored to electioneer for a Prophet of God.”

Traveling

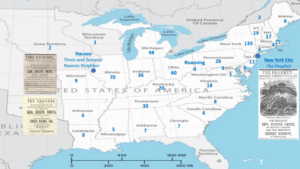

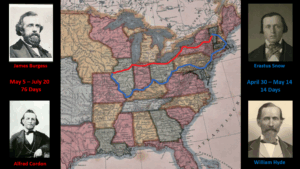

This map shows the number of electioneers assigned to each of the states and territories.

New York, with 133, had almost twice as many as the next, Illinois, with 70. Church leaders usually assigned the missionaries to their former home states to build a base of support amongst family and friends.

The campaign was headquartered in Nauvoo and New York City. Both published newspapers advocated for Joseph, publishing reports of the conferences and electioneer activities, and creating confidence in the campaign.

Electioneers traveled by walking, riding horses or in carriages. Taking steamboats and canal boats. And even, for a few, the railroads of the East. Yet all walked some of the way — and most walked all of the way.

Here are two companionships assigned to Vermont, one of the furthest states from Nauvoo.

State campaign president Erastus Snow and William Hyde departed by steamboat on April 30th. They switched boats in St. Louis, disembarked in Pittsburgh, took canal boats and railroads across several states, and arrived in Burlington on May 14th. A two-week trip.

Recent converts and English immigrants, James Burgess and Alfred Cordon, left May 3rd without a dollar between them. They traveled the entire 1,177 miles on foot, reaching Burlington on July 20th, only to read in the newspapers that their seven-week journey was for naught. Joseph was dead. However, like the other missionaries, Cordon and Burgess preached and politicked all along the way.

Teaching & Campaigning

In fact, electioneers taught and campaigned constantly. On steamboats, on canal boats, on the railroads, in private homes, in public squares, schoolhouses, courthouses, large rented public halls. They even hijacked some extended religious camp meetings.

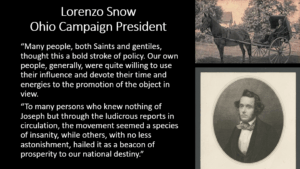

Lorenzo Snow, who was the campaign president for Ohio, was the first to leave. He departed by steamboat on April 10th, the day following the electioneer meeting, and delivered, “the first political lecture that was ever delivered in the world in favor of Joseph for presidency.”

Snow illustrates in word and deeds the general work and reception of the electioneers. He procured copies of Joseph’s Views and crisscrossed the state distributing them and stumping for Joseph. He held his organizing convention in the Kirtland Temple — an appropriate venue given the dual nature of their missions. Snow then assigned the electioneers specific congressional districts to operate in.

He later recorded the typical reactions of fellow Latter-day Saints and other American citizens:

“Many people, both Saints and Gentiles, thought this a bold stroke of policy. Our own people generally were quite willing to use their influence and devote their time and energies to the promotion of the object in view. To many persons who knew nothing of Joseph but through the ludicrous reports in circulation, the movement seemed a species of insanity, while others, with no less astonishment, hailed it as a beacon of prosperity to our national destiny.”

The Electioneers’ Experiences

I want to give you a taste of the electioneers’ experiences using one of my favorite movie titles: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

The Good

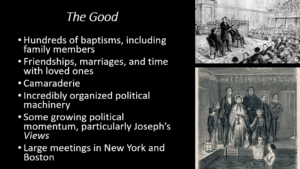

As they stormed the nation, preaching and politicking, much good followed the missionaries. They proclaimed to anyone who would listen the Book of Mormon, Joseph Smith, and the Restoration. Their preaching netted several hundred baptisms, including some family and friends. Daniel Hunt and Lindsey Brady baptized over 20 people in Kentucky, 12 of whom were Hunt’s relatives.

Even when friends and family rejected the message, the missionaries enjoyed spending time with loved ones. Moses and Nancy Tracy — Nancy being the one lone female electioneer — brought their four children with them to New York to meet their grandparents for the first, and what would be the last, time.

While called to New York, David Pettigrew also spent time visiting relatives in Vermont and New Hampshire. He also placed gravestones on his parents’ long unmarked graves.

Strengthening Relationships

Most developed strong friendships with their companions or deepened existing ones. The two British converts, Alfred Cordon and James Burgess, became lifelong friends even after Burgess refused to come west. Wilford Woodruff was thrilled to work in Maine with Milton Holmes, a former companion he had not seen for a decade.

It was often a family affair. German immigrant brothers George and John Riser labored in the German-speaking areas of Ohio. Eighteen-year-old Lorenzo Hatch and twenty-six-year-old Thomas Fuller traveled east together. Hatch became extremely ill from sleeping so often in the rain and stopped to convalesce at the former home in New York.

He quickly fell in love with his nurse — Thomas’s 17-year-old little sister, Hannah. When Father Fulmer figured out what was happening, he sent Lorenzo packing to his assignment in Vermont. When Hatch returned a year later to Nauvoo, Hannah was with him. They had eloped.

The electioneers also experienced many of the feelings and experiences common to missionary work even today. Franklin D. Richards penned love letters to his young bride. Alfred Cordon thought parts of Michigan looked like his native England, bringing pains for long and faraway family and friends.

Success

Several went sightseeing. Those in or traveling through upstate New York often visited Niagara Falls and the Hill Cumorah. William Appleby investigated the still-smoldering ruins of a Catholic neighborhood decimated in the Philadelphia Bible Riots. Some noted watching fireworks on Independence Day. More than one companionship crashed wedding receptions or other public events where there was food. In the middle of a terrifying lightning storm, Jeremiah Curtis and his nephew-companion Joseph witnessed a bolt strike and kill a man.

Despite the odds, the electioneers found some success in their politicking. Most state campaign presidents, as we saw with Lorenzo Snow in Ohio, did not disappoint. Charles C. Rich and Harvey Green created a campaign machine that modern parties would be impressed with, in Michigan. They had Views printed and distributed by the thousands and assigned companionships to their congressional districts. All the while they crisscrossed the state, stumping for Joseph, and coordinating and encouraging their electioneers.

Charles Wandell and Markellus Face did the same thing in New York, seemingly everywhere. Daniel Spencer had his electioneers in Massachusetts zone in on their congressional districts and created a good amount of public interest in Boston, leading to the campaign’s largest convention.

Building Momentum

Into late June and early July there was real but modest momentum building. Newspapers throughout the nation were commenting — mostly ridiculing — Joseph’s campaign and the electioneers were arriving in their states. However, non-Latter-day Saints did attend political conferences, meetings, and stump speeches anywhere they happened. Electioneers often noted the interest and even approval of many regarding Joseph’s policy ideas and the belief that the country needed reforming.

In Kentucky, George Miller attended a large Whig political barbecue. He started talking with some of his old acquaintances about Joseph’s Views. Soon, more were trying to listen to Miller than the Whig speaker. Sensing the moment, he jumped up on a large stump and commenced reading Joseph’s Views. Most of the crowd approved and abandoned the barbecue, carrying Miller on their shoulders to a tavern to give him a proper meal.

Making Headway

A two-day mass meeting in New Hampshire, heavily attended by non-Latter-day Saints, had a “spirited and interesting discussion.” Resolutions passed with only five dissenting votes to use “all lawful ways and means to reform the abuses of trust in power” by backing independent candidates. The popularity of Joseph’s Views amongst the group rendered him worthy of their votes.

In most states, the electioneers were making some headway. Journalists’ articles on mass meetings in Boston and New York proved the point.

The Bad

However, not all — or even most — experiences were positive.

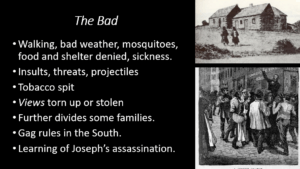

Most left Nauvoo during the Great Flood of 1844, the largest recorded still today flood of the Upper Mississippi. Rain-soaked clothing turned roads to mud, made rivers and streams dangerous, and produced a plague of mosquitoes, which they all seem to note in their journals, with malaria in its wake.

Many went hungry for days with lack of money or charitable meals. Often denied board because of who they were, they spent more nights under the rain than under the stars. Several became very ill.

Jacob Hamblin was so desperate to sleep indoors and have a decent meal that he offered his extra cold clothing for payment — to no avail.

Opponents injured some electioneers by throwing sticks, stones, and anything they could put their hands on. They particularly enjoyed spitting tobacco juice in missionaries’ faces. One electioneer recorded that the people treated them like dogs. Another said like black slaves.

Enemies

Enemies tried to stop the electioneers any way they could. During a large meeting in New York City, someone intentionally broke the building’s gas pipe feeding the lanterns, ending the meeting in darkness and confusion.

Some would strip the Views pamphlets right out of the electioneers’ hands and tear them up. Some would even steal them from the printing shop. This was especially prevalent in the South because Joseph’s Views called for the gradual emancipation of slaves.

In Tennessee, campaign president Abraham O. Smoot ordered 3,000 copies of Views but never received them. A prominent attorney threatened to sue Smoot, the printer, and the Church for allegedly violating a state law that forbade “any publications calculated to excite discontent, insurrection, or rebellion amongst the slaves or free persons of color.”

Of course, the most difficult experience the electioneers faced was the news that a conspiratorial mob had murdered their prophet and presidential candidate. I’ll cover that a little later.

The Ugly

As bad as these experiences were, there were uglier ones.

Opponents made death threats against Joseph. Eerily, a few antagonists alleged that there were already men organized to assassinate Joseph before the election. The death threats extended to the missionaries as well. A man in Ohio publicly damned the missionaries and threatened to “stain his hands with their blood” if they called Joseph a prophet.

After George Miller’s success at the Whig barbecue, someone ordered him to leave the area and stop “preaching your religious views and political Mormonism,” or his slaves would lynch him.

Past Threats

In some cases, things progressed past threats. A mob tarred and feathered Eli McGinn. A few companionships did face mobs intent on killing them. Benjamin Brown and Jesse Crosby held the door to their room against the ruffians three times in one night. A sad foreshadowing of their prophet-candidate, who would fruitlessly attempt to hold the door against his assassins.

David Hollister was electioneering with remarkable success on a steamboat when suddenly an enraged Missourian drew a bowie knife. Hollister evaded the knife and quickly had the Missourian over the rail. Bystanders intervened, perhaps saving both of their lives.

In Boston, the convention for Joseph Smith’s campaign filled the thousand-seat Melodeon Hall. Towards the end of what had been a very successful day generating good non-Latter-day Saint interest, chaos erupted. Several young Whig agitators started fist fights, which escalated until the police arrived. By then, most of the attendees had fled outside, unceremoniously ending the convention.

Sister Camp

Abraham O. Smoot and his electioneers held a conference with interested locals in the courthouse of Dresden, Tennessee, when a mob suddenly launched bricks and sticks through the windows.

A week later, they met again — this time with hickory sticks in hand. Again, a mob formed, led this time by the local sheriff. They forced their way in and surrounded the gathering. When one of the men moved to assault Smoot, Sister Camp — a six-foot, 200-pound local Latter-day Saint — intervened:

“You dare touch one of them elders,” she roared, “and I will see your heart blood.”

The sheriff backed down, as did the mob. Sister Camp led the missionaries out of the courthouse, hickory sticks at the ready.

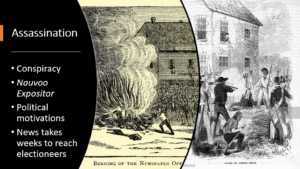

Assassination

Ultimately, the ugly violence reached the electioneers’ prophet and presidential candidate. A conspiracy of disaffected Saints and Joseph’s local and regional political enemies used the Nauvoo Expositor experience to get him into Carthage Jail.

In a solemn conversation on the morning of June 27th, Joseph lamented that this was not the season they had supposed.

“We have the revelation of Jesus and the knowledge to organize a righteous government upon the earth,” he explained, “to give universal peace to all mankind if they would receive it.”

They didn’t. Later that day, the mob forced the prison and assassinated him.

The violent end of the campaign shocked and traumatized the electioneers. News traveled slowly, and most heard the awful truth weeks later. They believed they were on heaven’s errand to bring religious and political salvation to the nation. It had never entered their minds that it would all end in Joseph’s assassination.

Here are two of the dozens of recorded reactions from the electioneers.

Reactions of the Electioneers

The only female electioneer, Nancy Tracy, wrote:

“We were horror-stricken. My husband sobbed out loud, ‘Is it true? Can it be true, when so short a time ago he set us apart to fulfill this mission and all was right?'”

John Loveless heard the news on a steamboat headed back to Nauvoo:

“A perfect shout was set up by the devil’s incarnate on our boat, who were on their way to fight the Mormons. Had I possessed the strength of Samson, I would, like him, have sunk the whole mess in one gulf of oblivion and sent them to their congenial spirits — the howling devils of the infernal regions.”

Following the example of the apostles, most electioneers returned to Nauvoo. Brigham Young, reflecting on the situation, said:

“As rulers and peoples have taken counsel together against . . . Joseph, and have murdered him who would have reformed and saved the nation, it is not wisdom for the Saints to have anything to do with politics, voting, or president-making at present.”

The campaign, with its martyr candidate, was officially over.

The public and private words and actions of Joseph, other church leaders, and the electioneers conclusively show that the presidential campaign and its election efforts were serious. In Joseph’s case, deadly serious.

Just a week after his campaign began, Joseph declared:

“If I lose my life in a good cause, I am willing to be sacrificed on the altar of virtue, righteousness, and truth in maintaining the laws and the Constitution of the United States, if needs be, for the general good of mankind.”

That sober statement became a prophetic summation of his campaign.

No Room in the Nation for the LDS Zion

The campaign and its outcome demonstrated that there was still no room for the Latter-day Saints and their Zion in America. The Saints weren’t alone in being persecuted. That same summer, nativist Protestants murdered Catholics and burned down a Philadelphia neighborhood. Freedom of religion was not for non-Protestant Saints and Catholics, who, despite being Caucasian, were considered not white, but viewed as a separate race more akin to American Indians, Mexicans, and Blacks.

So, in 1846, the Saints fled the nation and began implementing what they called Joseph’s measures, including creating aristarchic theo-democracy.

Electioneers and the Establishment of Zion in the Great Basin

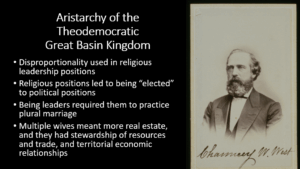

They established a strong theo-democracy that would hold against the federal government for half a century. The electioneers were right in the middle of it.

The campaign had a strong, lasting, and identifiable effect on the electioneers: they became the fruit of the tree. They developed into the foundation of the theo-democracy the apostles built.

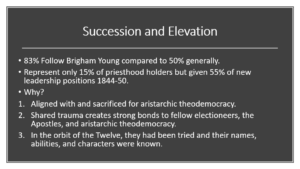

In fact, 83 percent followed the apostles west, compared to an estimated 50 percent of all Saints. From 1844 to 1850, Church leaders placed electioneers in 55 percent of available leadership positions, including all four new apostleships, despite representing only 15 percent of available priesthood leaders. This disproportionate trend continued throughout the decades.

Theo-democratic Kingdom

In the Great Basin theo-democratic kingdom, religious position encompassed all of Zion’s components. Church leaders nominated ecclesiastical leaders to parallel political offices, and the Saints voted them in. For example, the bishop of a town was elected mayor. Stake presidencies served as territorial legislators and county judges. And so on.

As religious and political leaders, they were expected to practice plural marriage. Because men with plural wives received extra land for each wife, and these leaders managed the natural resources and trade in their jurisdictions, they also became economic leaders. They were the workhorses of Zion — and disproportionately, they were electioneers.

The question is: why?

While there’s no smoking gun as to why they were used more than others, in my qualitative and quantitative research, I have found that:

“No other pre-campaign variables could predict the high number of electioneers in post-martyrdom leadership — not income, previous church position, age, occupation, family connection, priesthood office, mission, or missionary service.”

Three Reasons:

So again, why? Three reasons:

- First, their words and actions in the campaign demonstrated that they believed in and sacrificed for theo-democracy.

- Second, psychologists have long established that shared trauma creates strong relational bonds. Even in strangers, let alone a group of men (and Sister Tracy) who were already one in mind and heart. The intense trauma of learning of Joseph’s tragic assassination forged unique bonds to one another, the apostles, and theo-democratic Zion.

- Third, the electioneers were in the orbit of the apostles, who led, instructed, and labored with them. They experienced together the sacrifice for theo-democracy and the trauma of Joseph’s tragic death. The Twelve had seen the electioneers’ work, knew their names, abilities, and characters. When the apostles assumed the helm, it came naturally to choose them.

Just quickly to end with, I want to share three quick things:

First, I found my own fourth great-grandfather was an electioneer. He was at that fight — I’m not sure if he hit or got hit — but he was there.

The other is that the electioneers have tens of thousands of living descendants. 99.9 percent of them have no idea their ancestor campaigned for Joseph Smith. They’ve missed out on this important part of their family history.

A Special Bond

I have a website — stormingthenation.com — that lists all 621 electioneers, plus the Quorum of the Twelve who led them. If you have any Church ancestors in America during 1844, it’s worth your time to take a look.

I feel a special bond with these men and Sister Tracy. I’ve dedicated 15 years to them and their cause of Zion. I’m slowly publishing small biographies linked to their names.

Finally, see if this sounds familiar:

They worked in a time of governmental corruption, blinding bigotry, intense partisanship, partisan and misleading media reports, riots, and political violence.

Unity is Power

The Views pamphlet the electioneers carried contained this simple phrase:

“Unity is power.”

May we be committed and courageous to promote unity in our time. Thank you.

Q&A

Scott Gordon:

Thank you, that was very interesting. I think that’s an area of Church history that we don’t look at very much. So, a few questions here. Did Joseph Smith run as an independent candidate or as part of a political party? If so, what party?

Derek Sainsbury:

He ran as an independent. Eventually, they named their party “Jeffersonian Democracy.” It connected with those who didn’t like the second-party system, with the major political parties and all that had happened. So, he was running as an independent candidate, but eventually they called their party Jeffersonian Democracy.

Scott Gordon:

With that party, which party would you guess it would siphon the votes from?

Derek Sainsbury:

That’s a great question. Where they were getting the most action was from people that were disconnected from both [parties]. The weird little thing is, Polk wins the election and the vote in New York was razor, razor thin. The Saints in New York and their supporters all ended up voting Democrat, which gave Polk the win. So if the election had continued, there is a small chance that he might have been a spoiler if people had actually intended to vote the way they were showing some interest.

Scott Gordon:

Were his assassins from the party that they would have siphoned the votes from?

Derek Sainsbury:

Mostly from the Whigs, yeah. There are several great books that you can read about. As far as political affiliation and how politics meshed into the conspiracy.

Scott Gordon:

Of course, the Whigs are such a strong party today… (laughs)

Derek Sainsbury:

Joseph had a prophecy about that.

Scott Gordon:

Is it possible that Joseph’s campaign accelerated his assassination?

Derek Sainsbury:

I would say most likely yes.

Scott Gordon:

One side effect of this electioneering effort was to have most of the Twelve safely out of town at the time of his martyrdom. Only two apostles who did not go electioneering were both killed in Carthage, and John Taylor was very nearly killed — (that’s just a statement from somebody.)

If Joseph Smith had lived and if he had been elected president, do you believe he would have been able to use the power to protect constitutional rights in the states? That power was not granted to the president by the Constitution — the 14th Amendment was passed in 1868.

Derek Sainsbury:

Yeah, but my answer to that is: he had no chance of winning. Unless there was a great Pentecostal spiritual awakening in America that decided to go for Joseph. The politics of that time were too complex and too complicated to believe that had he gotten in. He would be able to solve that problem.

Scott Gordon:

Do you think a sitting prophet will ever run for public office in the future?

Derek Sainsbury:

(Laughs) Well, I’ve been told not to talk about the Council of 50… No, I don’t think so.

Scott Gordon:

Has any other presidential candidate been detained in jail during their campaign? Or has any other presidential candidate ever been killed during their candidacy, to your knowledge?

Derek Sainsbury:

Bobby Kennedy is the only other one assassinated. In fact, that’s what I’m writing my next book on — as a comparison of the two of them. As far as Latter-day Saints who ran, I don’t ever know of George Romney or Mitt Romney ever being in jail.

Scott Gordon:

Well, you wrote an excellent book. Thank you.