Summary

Mike Ash and Ugo Perego address claims that DNA evidence disproves the Book of Mormon’s historical authenticity by not finding Israelite DNA among Indigenous Americans. They propose that Lehite groups, described in the Book of Mormon, would likely have mixed with a larger existing population in the Americas, explaining why no identifiable Israelite DNA may be traceable today. They further argue that DNA analysis on this issue is limited by factors like genetic drift and admixture, which can obscure small groups’ DNA over generations, and advocate for a nuanced approach to scripture and science.

This talk was given at the 2023 FAIR Annual Conference at the Experience Event Center, Provo, Utah on August 2, 2023.

Michael R. Ash is a longtime FAIR contributor and author known for his thoughtful defenses of the faith. He has written extensively on Latter-day Saint topics, including Shaken Faith Syndrome and Bamboozled by the CES Letter.

Transcript

Introduction by Scott Gordon

Our next speaker is Mike Ash. Mike Ash is a veteran member of FAIR. He’s been with us forever—at least as long as I can remember. He is a former weekly columnist for the Mormon Times in Salt Lake City’s Deseret News and has presented several papers at LDS-related symposiums. He is the author of Of Faith and Reason: 80 Evidences Supporting the Prophet Joseph Smith, Shaken Faith Syndrome: Strengthening One’s Testimony in the Face of Criticism and Doubt, Bamboozled by the CES Letter, and Rethinking Revelation. He has written hundreds of articles defending the faith, which have been published by FAIR, FARMS, Sunstone, Dialogue, and the Ensign.

His co-author on this talk is Ugo Perego. Ugo Perego is a native of Italy. He received a BS and MS in Science from BYU Provo and a PhD in Genetics and Biomolecular Sciences from the University of Pavia, Italy, under the mentorship of Professor Antonio Torroni. His PhD dissertation focused largely on the original migrations of Native American populations using different genetic markers. Ugo is currently a full-time biology instructor at Southwestern Community College in Iowa. He lives with his family in Nauvoo, Illinois.

So, with that, we’ll have Mike Ash come forward.

Presentation

Mike Ash:

Good morning. It’s exciting to be here today. Yes, I co-wrote this with Ugo, and it’s a topic that he obviously has all the technical background in. He’ll be here for the Q&A to answer any questions that go way over my head. But this is a paper we worked on together because I have an interest in assumptions and the human element that makes this a faith challenge for some people.

Theories Regarding Early Population of the Americas

When the Book of Mormon first came forth, there were several theories regarding how the Americas were first populated. The Book of Mormon seemed to provide some support to a common early American theory that the New World was originally populated by people from Old Testament days, perhaps even from the Lost Tribes.

Over time, however, newer scientific studies indicated that the ancient Americas were mostly, if not wholly, populated by Asiatic groups that came to the New World thousands of years before any Book of Mormon peoples might have arrived.

DNA studies, for instance, are among the scientific fields of research that have contributed to answering the question of New World population origins.

Members of the Church see mortality as a testing ground where we must live by faith. Deep down inside, however, most of us think it would be comforting to find secular evidence that would prove to the world that Joseph Smith was a prophet.

Individuals hostile to our theology, on the other hand, are typically convinced that Joseph Smith was a fraud and they are confident that science will eventually find a “silver bullet” to end his prophetic pretense.

DNA Studies and The Book of Mormon

DNA studies appeared to be the kind of scientific weapon that would either vindicate the Church or substantiate the critics’ attacks. This idea sounds good on the surface, but does not really hold up under scrutiny. As one vocal critic explained, even if modern DNA studies exhibited an Israelite presence in the ancient Americas, it would not in the slightest lend some credence to Mormon truth claims.

All such a find would do, he argued, was confirm what many people in Joseph Smith’s day already accepted—the common belief in the United States 175 years ago that the “Red Man” was a descendant of the Israelites.

This consideration, of course, is mostly accurate. While the discovery of Israelite DNA from ancient America would be consistent with the Book of Mormon story, it would not prove that the Book of Mormon was true or that the DNA belonged to Lehi and his descendants.

If, on the other hand, no Israelite DNA could be found in modern indigenous peoples of the Americas, it might again appear to be a victory for those arguing against the historicity of the Book of Mormon. And that is exactly what happened.

There is strong DNA support for the Asiatic origin of the indigenous peoples of the New World. This creates an apparent discrepancy between the Book of Mormon narrative and modern science. According to DNA data, the New World was not first populated by people from the Tower of Babel or Lehites from Jerusalem.

The scientific evidence regarding the origin of the Amerindians has been used by some critics as a favorite weapon with which to bludgeon Joseph’s prophetic abilities. The Book of Mormon, they argue, is of fictional nature and simply repeats a common 19th-century myth regarding the population of the Americas.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as an institution, is a large canopy. It embraces a diversity of family members, some of whom have slightly different viewpoints on certain beliefs. The Book of Mormon has often been the topic of both under the canopy family disagreements as well as food fights.

Although some members believe that the Book of Mormon can be both sacred scripture as well as a fictional tale dictated by Joseph Smith, orthodox members traditionally accept the book as a record written by real ancient prophets about ancient New World Christians and pre-Christians.

Ugo and I accept the traditional narrative of Joseph Smith and the translation of the Golden Plates. We believe that Joseph Smith received real metal plates that contained records of real people who once lived in the ancient New World.

This record-keeping people, whom we know as the Nephites, recorded not only their religious history, but also their interactions with God and a visitation from the Savior.

For those of us who accept the traditional narrative, the DNA data—unless more closely examined—could present a stumbling block to faith. In the paper which Ugo and I wrote, we discussed the limitations of a generalized, all-or-none approach to the relationship between the Book of Mormon in its proper religious context and the genetic history of the ancestors of the Amerindians.

We also restate fundamental basic principles governing the field of population genetics within the proper historical context of the Book of Mormon narrative.

As we will show, the critics’ assumption that DNA studies prove the Book of Mormon to be fictional is erroneous because the DNA/Book of Mormon issue is more complex than simply looking for the presence or absence of Old World DNA in modern or even ancient Amerindians. It’s important, however, that we first examine common assumptions and expectations to determine if genetics can provide a reliable testing hypothesis for the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon record.

What does the Book of Mormon say, and what doesn’t it say? What should it say, and what shouldn’t it say?

The Book of Mormon’s Say About the Native American Population

The traditional folk interpretation of the Book of Mormon suggested that the Jaredites were the first people to come to the Americas and as their civilization was coming to an end, the Lehites and the Mulekites arrived in the New World.

These three groups, according to the traditional interpretation, were responsible for populating virtually all of the Americas. Such was the conclusion of most, if not all, early Latter-day Saints. This reading has been perpetuated as a tradition among members of the Church, although an official statement on this matter has never been made.

While the Church said little about the issue until recently, the hemispheric geographic model has been rejected by virtually all Latter-day Saint scholars.

The Church recently published two articles titled The Book of Mormon and DNA Studies and Book of Mormon Geography, assuming a limited rather than hemispheric geographic model. While the articles in question do not declare the issue to be doctrinally relevant, the fact that they are posted on the official Church website does suggest a quasi-official endorsement of the best current academic perspective regarding Book of Mormon geography.

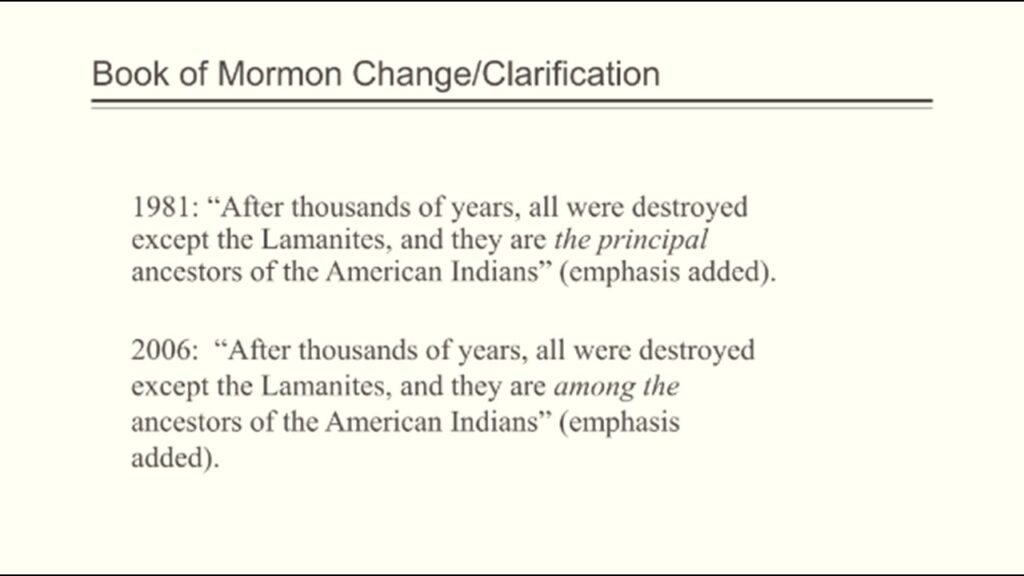

In recent years, renewed emphasis on this subject sparked for a change the Church made in the introduction of the Book of Mormon.

The 1981 text read, “After thousands of years, all were destroyed except the Lamanites, and they are the principal ancestors of the American Indians.” (Emphasis added.)

In 2006, a minor change was introduced: “After thousands of years, all were destroyed except the Lamanites, and they are among the ancestors of the American Indians.” (Emphasis added.)

Since this introduction was not part of the original Book of Mormon manuscript, it was a modern addition to help prospective readers understand the book’s claims. This change seems intended to clarify, not modify, the Book of Mormon‘s narrative pertaining to population dynamics.

In fact, both terms implicitly acknowledge the existence of other populations at the same time as the Book of Mormon peoples.

The logic of the early Latter-day Saints’ interpretation derives from the following assumptions, which were prevalent in Joseph Smith’s day:

- The Noachian flood wiped out all but a handful of humans who ended up in the Middle East.

- The peopling of the Americas had to come after the universal flood and was likely initiated by a group or groups of individuals who came to the Americas from the Middle East.

- The Ten Lost Tribes of Israel had been dispersed to remote regions of the world, including quite possibly the Americas.

While the Book of Mormon does not teach the Jaredites, Lehites, and Mulekites were part of the Lost Tribes, the story of the three Middle Eastern migrations meshed quite well with the popular early American view that the native peoples of the Americas were descendants of Israel.

Revelation vs Assumption

Without revelatory course corrections, Latter-day Saints—like all humans do—believed, defended, and promoted the ideas that made the most sense from their own paradigms. And this dynamic applies to prophets as much as it does to any other person. In the absence of revelation, every prophet—from Adam to Moses to Paul to Joseph Smith to Russell M. Nelson—has the freedom to voice their opinions and come to their own conclusions, even if those opinions and conclusions are incorrect.

Based on a 19th-century American paradigm, the plain reading of the Book of Mormon text generated an interpretation that, while blending comfortably with the assumptions of an earlier generation, did not accurately (from today’s academic perspective) account for how the text should read if it truly came from the ancient past. As most scholars understand today, there is no such thing as the “plain reading” of the text.

As Bruce Malina, a social scientist and American biblical scholar, explains, “Meaning does not come from the words; meaning invariably derives from the general social system of the speakers of a language.”

Malina’s colleague New Testament Richard Rohrbaugh, noted, because all readers “must interact with writings and ‘complete’ it if it is to make sense, every written document invites immediate participation on the part of the reader. Thus writings provide what is necessary, but cannot provide everything.” Everything we read is filtered through our thoughts, perspectives, and assumptions.

“The facts of the world,” notes science writer and historian of science Michael Shermer, “are filtered by our brains through the colored lenses of worldviews, paradigms, theories, hypotheses, conjectures, hunches, biases, and prejudices [which] we have accumulated through living. We then sort through the facts and select those that confirm what we already believe and ignore or rationalize away those that contradict our beliefs.”

For example, in 1963, more than a decade before Black Latter-day Saints were allowed to receive the blessings of the priesthood, the late Latter-day Saint scholar Eugene England met with the Apostle Joseph Fielding Smith (who later would become President of the Church) and discussed the common Latter-day Saint belief that Black members were less valiant in the premortal existence.

England recalled,

I got an appointment with Joseph Fielding Smith and asked him directly if I must believe in the pre-existence hypothesis to have good Church standing. He replied, ‘Yes, because that is the teaching of the scriptures.’ I asked him to show me the teaching in the scriptures since I had not been able to find it there. President Smith patiently went through the sources with me, particularly the Pearl of Great Price, and then he said something quite remarkable: ‘You do not have to believe that Negroes are denied the priesthood because of the pre-existence. I have always assumed that because it was what I was taught, and it made sense, but you don’t have to believe it to be in good standing, because it is definitely not stated in the scriptures. And I have received no revelation on the matter.’”

Assumptions drive our inferences about the things we encounter. Sometimes they’re right, sometimes they’re wrong. This gets more complicated when we try to interpret the writings of authors who lived in a time and culture far removed from our own.

As historian Sam Wineburg explains,

Because we more or less know what we are looking for before we enter this past, our encounter is unlikely to change us or cause us to rethink who we are. The past becomes clay in our hands. We are not called upon to stretch our understanding to learn from the past. Instead, we contort the past to fit the predetermined meanings we have already assigned it.”

Modern prophets have not received revelatory details needed to clarify our historical and geographical understanding of the Book of Mormon. Instead, they receive revelation on how the Book of Mormon works as a spiritual instrument.

Our human nature, however, leads us to demand responses for all unanswered questions. Therefore, assumptions about the earliest American populations and how they’re related to the Nephite scripture have emerged from supposition, as well as from the informed and uninformed opinions of both Latter-day Saint leaders and the general membership.

These speculations and opinions were shared—and are still shared—from the pulpit, as well as in religious classroom settings. The things one hears casually mentioned in Sunday School often acquire quasi-official status, and these unofficial “truths” become culturally entrenched until someone questions whether such interpretations are truly official, as was expressed in the story of Eugene England and Joseph Fielding Smith.

Science vs Religion

An analogist case is the apparent discrepancy between biological evolution and the biblical account of the Creation. Scientific evidence abounds when it comes to the evolutionary processes involved with the formation of the Earth and everything within and upon it.

Evolutionary theories, however, are often rejected by those who adopt what they believe is a plain, literal reading of the biblical text. So who is right—science or scripture?

As evangelical biologist Jeff Hardin explained to writer William Saletan,

when the two… don’t seem to match, the error might be in his own understanding of the Bible. Rather than reject what science has discovered, [Hardin] asks how scripture can be understood better so that it fits the scientific evidence.”

Even the Church recently suggested a more nuanced approach to the biblical account of the Creation, reminding us that many of the details surrounding this event have not yet been revealed. We should learn to take a similarly nuanced approach with the Book of Mormon text.

Just because most past and current members believe that the Lehites populated the entire New World does not mean that such a view is taught in the text.

In fact, thanks to science, we cannot deny the existence of perhaps millions of people in the Americas prior to the purported arrival of Book of Mormon immigrants, and this must be taken into consideration as we read and interpret the Nephite records, regardless of what anyone has said in the past about the contribution of Lehi’s party to the population.

So, to quick- I’m going to put in a shameless plug here to a book that FAIR published of mine a couple of years ago called Rethinking Revelation: The Human Element in Scripture/The Prophet’s Role as Creative Co-Author, ‘cause this ties to this topic that I’ve discussed so far, in how God speaks to all of us, including prophets, through the manner of our own language, and how cultural biases, and opinions, and so forth still affect the language in which revelation is given—it’s the “manner of our language.”

LDS Scholars’ Studies of Peoples in the Book of Mormon

Long before James Watson, Francis Crick, and Rosalind Franklin discovered the double helix structure of DNA, a number of Latter-day Saints were coming to realize that the Book of Mormon peoples might not have been the sole parties responsible for populating the entire Western Hemisphere.

Based on a close reading of what the text did and didn’t say about itself, these Latter-day Saints scholars concluded that the Lehites represented a small incursion into a larger existing American indigenous population.

This reminds us that this perspective is not a recent development cobbled together to save a “floundering Book of Mormon” from the threat of DNA science, but that it arose long before DNA science became a tool to criticize the Book of Mormon’s historicity.

Scholarly views of the Book of Mormon changed not because of DNA studies but because a growing number of Book of Mormon students were attempting to understand the text from within a larger framework.

This expanded view approaches the Nephite text not only with an acceptance of what modern science tells us but also with the understanding that the original text was written by ancient Old World and New World authors who had pre-scientific worldviews.

Because Latter-day Saint scholars have changed some of the ways we look at the Book of Mormon as history, some critics have accused believing scholars of making ad hoc alterations to salvage the book’s historicity.

Modifying paradigms, however, is a legitimate scientific approach for dealing with anomalies and should not simply be brushed aside.

For example, Daniel Little, a philosophy professor and chancellor at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, claims that when scientists encounter anomalies in their theories, they

must choose whether to abandon the theory altogether or to modify it to make it consistent with the contrary observations. If the theory has a wide range of supporting evidence (aside from the contrary experience), there is a powerful incentive in favor of salvaging the theory”

by modifying the original paradigm. These progressive modifications are integral to paradigm maintenance, and anomaly management is typical in science.

In line with these principles, Guy Consolmagno, director of the Vatican Observatory, summarized a similar concept for stating that science is not meant to prove anything but to describe what we humans observe. In his experience, what humans have seen for centuries needs continual reevaluation based on better technology and understanding.

The Book of Mormon text has changed very little over time. What has changed is our capability to understand its narrative from with an ever-growing body of evidence regarding the origins of America’s first inhabitants.

John Charles Duffy, a former Latter-day Saint and current visiting assistant professor of religion at Miami University, carefully reviewed the arguments of Latter-day Saint critics and apologists.

Observing that the critics’ accusation that Latter-day Saint scholars resort to the ad hoc fallacy by modifying their Book of Mormon paradigm to accommodate non-Lehites in the New World, he wrote,

“I am not moved by revisionist complaints that the apologists invent ad hoc hypotheses to protect and maintain a crumbling central hypothesis.”

I am not moved by these complaints because the majority of tone aside,

they accurately describe what all scholars do. In the face of contrary evidence, all scholars invent hypotheses that will preserve the paradigm to which they are committed…”

unless extra-scientific forces prompt them to convert to a different paradigm.

“All scholars assign the greatest relevance to those facts for which their paradigm accounts. Facts they cannot explain, they set aside as problems for which solutions will later have to be found.”

Scholarship is a strenuous and devoted attempt to force nature into the conceptual boxes supplied by one’s paradigm.

“This is as true for orthodox scholars as it is for the revisionists.”

While Latter-day Saint scholars’ modifications directly impact the DNA argument, it should be pointed out that this reframing preceded the Book of Mormon DNA issue. Greater understanding of the Book of Mormon came and continues to come from more careful textual analysis, efforts to interpret the text from an ancient perspective, and other scientific and historical discoveries.

Most Latter-day Saint scholars believe—and have believed for a while—that the Americas were inhabited thousands of years before any Book of Mormon civilizations arrived. Various clues from when the Book of Mormon itself, the text, as well as recognition that the text was written by a tribal dynasty in ancient times, suggest that the Lehites not only would have encountered these native populations but also would have been absorbed into these larger populations.

Unfortunately, we are not privy to the details regarding the text of these assimilations—how soon after the arrival of Lehi’s group the admixture took place, or even when this admixture happened.

Most of these events would have taken place during the first few generations after the arrival of the Book of Mormon migrants to the promised land. If these events were mentioned at all, details, encounters with local indigenous groups, degrees and timing of admixture (if any), and all related population events would have been contained in the 116 pages of the lost manuscript, which covered a period of nearly 450 years.

These difficulties play a fundamental role in determining what a valid hypothesis that could be tested through genetic evidence would look like. We simply do not know enough about the early population dynamics of Book of Mormon people to confidently infer what we should realistically expect to find (or not find).

In the DNA of modern and ancient Native Americans we will not here recite the many Book of Mormon textual evidences that suggest the presence of others in the New World or how the Book of Mormon groups retained the apparent dominant tribal identity even when they mixed with populations larger than themselves.

These issues have already been answered by many others. The resolution of most objections to historicity on genetic grounds hinges on setting realistic expectations about what genetic evidence could possibly be found to validate such arguments.

Cultural Identification vs Genealogical Identification

First, however, we must address a few common questions that are asked by many critics and some members. If the Lamanites were a small group who left no DNA trace because they were absorbed into a larger population, then who are the Lamanites today? Why did Joseph Smith call Native Americans Lamanites? And to whom was the Book of Mormon written?

While DNA tests may be able to determine biological affiliation to past individuals, it is not the only way to recognize tribal descent. The other two major indicators for tribal pedigree are cultural and genealogical factors.

In most cultures, including ancient cultures, people use exonyms to refer to anyone outside of their group. An exonym is a foreign-applied label rather than the name that people give themselves.

Germans, for instance, do not typically call themselves Germans; they refer to themselves as “Deutsch.” Italians call Germans “Tedeschi,” while the French refer to the Germans as “Allemands.” The Hawaiians were known to others as “Kanakas,” and the Greeks referred to one of their neighbors, known as “Mizraim” to the Hebrews, as “Egyptians.” During the Old Kingdom, Egyptians referred to themselves as the “Remtju ni Kemet,” which meant “people of the black land.”

Likewise, many tribal groups in the Americas are known today by the names that have been given to them by European colonizers or other enemy tribes, and not by how they identified themselves culturally and traditionally through the centuries.

For example, the Navajo people call themselves “Diné,” which means “The People.” The name “Navajo” was introduced by the Spaniards in the 18th century. Similarly, while the term “Native American” is the current label for all groups whose ancestors lived in pre-Columbian America, these people were labeled in the near past with the term “Indian.” These native groups, however, were not known as either “Indians” or “Native Americans” to themselves until they were labeled as such by outside cultures.

We find in the Book of Mormon that the Nephite and Lamanite were also socio-political names. Book of Mormon writers and their followers were called Nephites, and virtually everyone else was called Lamanites. While Laman’s brother Lemuel was not a descendant of Laman, nevertheless, he and his children were called Lamanites because they joined with Laman. Any other Lehite or Nephite who joined the Lamanites would also have been called Lamanite.

People can join and leave cultural groups and their attached labels. Someone of any descent or ethnic background can be an American, African, Asian, or Latter-day Saint.

Jews in Utah can be termed as “Gentiles” because they are not Latter-day Saints. Even outside of Utah, the term “Jew” is applied to someone descended from Judah, as well as someone who adopts Jewish culture and religious life. Someone can be born a Jew or become a Jew through conversion.

Likewise, in 1 Nephi 14:2, we read that righteous Gentiles would be numbered among the House of Israel, as well as the seed of Lehi.

From Latter-day Saint point of view, whenever a dispensation of the fullness of the gospel has been on the earth, missionary work was priority to bring repentant souls back into the flock. These teachings were regularly found in the Book of Mormon narrative.

The term “Lamanite” meant different things to Nephi, Alma, Mormon, and even Joseph Smith. Like someone adopting the label “Jewish” or “Latter-day Saint,” we read in the Book of Mormon that someone could become a Lamanite.

After Christ’s visit to the New World, the Book of Mormon peoples lived in harmony for many decades. During this time, there were no Lamanites nor any manner of -ites, but they were all in one, children of Christ. We read of a small revolt several decades later by the people who had taken upon themselves the name of Lamanites. Therefore, there began to be Lamanites again in the land.

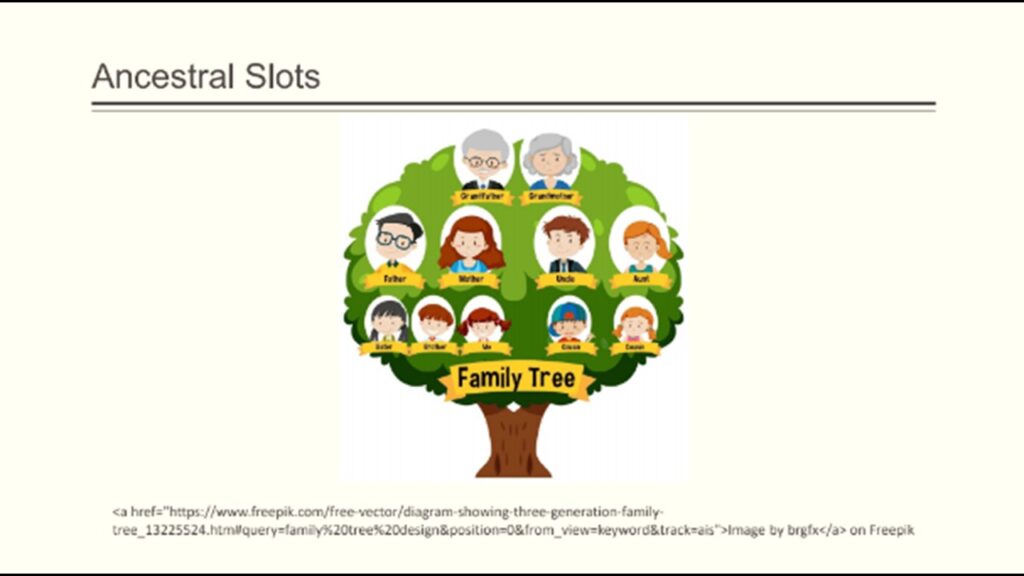

Genetic vs Genealogical Ancestry

Finally, it is important to differentiate between genetic ancestry and genealogical ancestry. As we fill the slots of a family tree, we find that as we go further back—from parents to grandparents to great-grandparents, and so forth—some of our ancestors will show up in more than one ancestral slot. Every person has two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, and so on.

As researcher Scott Heschberger explained, the number of slots grows exponentially. By the 33rd generation (about 800 to 1,000 years ago), we have more than eight billion of ancestral slots. That’s more than the number of people alive today and certainly a much larger figure than the world population a millennia ago. The reason this happens is that many of your ancestors occupy multiple slots in the family tree.

If we follow our ancestral tree back far enough, and as our ancestors appear in more slots, we eventually come to the “genetic isopoint”—the point in time at which every member of the entire historical population of a geographical area was an ancestor of the entire current population of that area.

The genetic isopoint for living Europeans, for instance, occurred just over 1,000 years ago. If there was a real Laman that had children and grandchildren in the New World, the chances are extremely likely that all modern Native Americans would be able to claim Laman on their family tree, assuming such a tree could be compiled, even if they did not retain any of his DNA. Let’s now see why.

Mathematical models of pedigree charts have shown how quickly these ancestral charts coalesce, thus supporting a much closer relationship between all humans than normally thought.

To start, every living individual has 1,024 ancestors at the 10th generation level. Each of these ancestors is essential for that one descendant to exist 10 generations later.

However, statistically, approximately 10 to 12 percent of these 1,024 ancestors would have contributed any DNA to the present time, 10 to 12 percent, with the rest of the ancestors’ DNA being lost due to chance. Therefore, while all 1,024 genealogical ancestors are absolutely needed for their one descendant to be alive, genetically, only a small fraction of them share any DNA with their posterity. As Heschberger points out, research indicates that we carry genes from fewer than half of our forebears from 11 generations back.

The process of genome inheritance is totally random, but plays a drastic role in the amount of genetic material that would be expected to survive to the present time—particularly if, in this case, admixture with local populations took place shortly after the Lehites’ arrival in the Americas, and if, as seems likely, the host population was millions of times larger than the Book of Mormon party.

Moreover, to add to the implausibility of any Lehite DNA surviving, let us consider that every Native American living today would have had more than 1 billion potential ancestors 30 generations back, or even 750 years ago, if we assume an average of 25 years per generation. Going back to the time of Lehi’s landing, that number would be in the range of 2 to the 100th power, or more than a nonillion (which is one followed by 30 zeros).

Of course, the actual number of Native Americans that lived approximately 2,500 years ago would have been a tiny fraction of that—perhaps in the order of a few tens of millions. What this means is that someone could genealogically be a descendant of an ancestor who lived hundreds or even thousands of years ago without carrying a single genetic marker from that progenitor.

While Native Americans may not retain DNA markers that tie them to the Book of Mormon Lamanites, it can certainly be argued that they have Lamanite ancestry based on genealogical and cultural affinity. In fact, from the Nephite perspective, it could be proper to refer to anyone in the Americas that lacked the knowledge of Christ from the time of Moroni to the days of Joseph Smith as a Lamanite.

If we read the Book of Mormon as an ancient text written by real ancient people with ancient perspectives and assumptions, we find evidence that merges with what we also learn from science—that Lehites were a small incursion of Israelites who joined the existing native population while continuing to write a book that tied them to their ancestral Israelite heritage. The DNA question then becomes not “Why do modern Native Americans not have Israelite DNA if ancient Middle Easterners were responsible for populating the Western Hemisphere?” but rather, “Is it possible to find Israelite DNA from a minor tribe who interbred with a larger existing population more than 2,500 years ago?”

When asked that question, several non-Latter-day Saint geneticists have confidently answered that it would be very difficult to find.

Quotes from those non-LDS scientists can be found in our paper, but to cite just one of these non-LDS geneticists, Daniel Hartl says, (and this is a paraphrase of a quote),

“If a number of Semitic-speaking people from the Middle East settled in North America about 2,500 years ago, and the indigenous population was large, ‘the probability’ that the DNA markers of the Semitic-speaking group would be lost ‘…is reasonably high.’”

DNA and Population Studies

Although some critics might view the arguments we present as apologetic dodges manufactured by believing Latter-day Saint scholars, the field of population genetics is rooted in the very principles we’ve described, and these stand at the very base of the DNA research discipline. Even when two populations have an equal start—same population size, same chance of survival, equal mating opportunities, and so forth—from the time of their admixture and onward, it’s expected that the genetic variation will inevitably change over time. The future gene pool resulting from the merging of these two different populations will include a greater genetic presentation from one group and less from the other. This natural process is called genetic drift and has been observed among many organisms, not just humans.

Simply stated, it is the probability of DNA to be selected and propagated when new offspring are conceived, generation after generation. There are several factors that can play a crucial role in the process of selection, and they have already been addressed elsewhere in light of the Book of Mormon and DNA studies. Obviously, if one of these two populations is disproportionately larger than the other—as in the case of the indigenous people of the Americas versus the colonizing group from Jerusalem—genetic drift will unsurprisingly work in favor of the host population’s gene pool and at a much faster rate.

Moreover, as Native American author Kim TallBear clearly and emphatically elaborated, outsiders should be very careful and particularly sensitive when defining individuals by their “blood” when describing Native American heritage. To Native Americans, their blood link is not as important as their cultural and traditional ties to the indigenous past.

Likewise, although the Book of Mormon peoples purportedly came from the Old World, their main objective was not to genetically colonize the Americas, but to find a haven in which to live their religious and cultural traditions. These were the values that they used to identify themselves. It was either acceptance or rejection of this system of beliefs that determined who was a Nephite and who was a Lamanite, regardless of biological issues.

We can look at similar issues to a similar issue; the lack of Roman DNA in the modern population of the United Kingdom as a model for our research of Lehite DNA. Population geneticist Jennifer Raff, for example, provided the following three postulates as explain of the lack of ancient Roman DNA in the modern population of the United Kingdom:

- Genetic drift may have erased their traces from the population.

- They may not have left numerous, or any, descendants in the population.

- They may simply not have been sampled yet.

Her article rings familiar if we attempt to discover genetic evidence for or against the Book of Mormon.

To be sure, DNA is a remarkable tool to answer questions about an individual population’s past. Through DNA testing, criminal cases are resolved, paternity is ascertained, and thousands of people are discovering their genealogical connections to their genetic cousins. DNA, however, is not the golden key that opens all doors. Certain questions will have conclusive answers, while others will provide diverse degrees of certainty.

Through DNA, we cannot prove, for example, the absolute existence or non-existence of famous historical figures unless we are able to find their remains and definitively recognize them as such. This does not mean that such people did not exist, and neither can we say that DNA is an inaccurate instrument. As one of the authors of this essay, Ugo, recently reported, “Uncertain tools work well for certain questions, and matching the tools to the proper question is both wise and productive, while applying a tool to a question it is not designed to address, brings confusion and dissatisfaction.” This also applies to the inability of using DNA testing to conclusively identify Israelite migrants potentially arriving to the American continent two and a half millennia ago.

Thank you.

Audience Q&A

Q&A

Scott: I think we’re going to have Ugo with us in just a moment. I believe he’ll be on the screen at some point. So, I have a couple of questions here for you:

Q: In Third Nephi 5:20, Mormon declares, “I am Mormon, and a pure descendant of Lehi.” The fact that he claims to be a pure descendant of Lehi implies that there are people who are not descendants of Lehi; otherwise, everyone would be a pure descendant of Lehi. What other parts of the text of the Book of Mormon imply the presence of other peoples?

A (Mike): Boy, right off the top of my head, I’m not able to think of several verses. There have been several articles written on this. Brandt Gardner has written some, if I’m not mistaken. There’s some at the Interpreter Foundation, and even some earlier articles — this has been going on for a while. John Sorenson wrote about it. So, there are several verses that basically suggest the presence of others. And again, we have to remember these were pre-scientific people, so they’re not looking at bloodlines. It’s cultural affinity that’s important to them.

And, like I said in my book Rethinking Revelation, I have a large section that talks about the cultural aspects of how that’s really what being Latter-day Saints is all about — it’s what being a child of God is all about, what being a covenant people is all about. And that’s how it’s understood today in a gospel aspect, and it was, of course, understood even more so in a cultural aspect before people understood DNA or any kind of genetics.

So, off the top of my head, I can’t think of the verses immediately, but if you even go to FAIR’s website or Interpreter’s website, you’ll find several articles that give better information on that.

Scott: We’d also like to welcome Ugo Perego here, our DNA geneticist.

Ugo: Can I add something to that question?

Scott: Yes, please.

Ugo: One concept that we need to remember is that the Book of Mormon is a summary, and it’s not a full story, okay? We forget it is an abridgment. And that, Mormon, when he wrote it, made a selection of what he was going to include in those writings. We often forget that part, and that tells us that we don’t have the full narrative.

Second, the first 450 years of the history of the Nephites is the one that was found in the 116 pages that were lost in the manuscript. We think that the small plates replace their history, but they don’t. Nephi is very clear that he’s not going to include historical factors in the small plates. And so, we’re missing from the summary, from the narrative that Mormon made, we’re missing 450 years of history, which are the first 450 years where all the dynamics would have taken place. They would establish the interactions and the changes and the mixture that we’re trying to infer from the Book of Mormon, so we are missing the story. We’re recreating a story without having the story.

Adding to that, even with the huge gap — and it’s a huge gap — number one: The Book of Mormon does not tell us that there were no other people, first of all, okay? So, we might say, “Well, it doesn’t say that there are people,” but it also doesn’t say that there are no other people.

Second, there are verses that actually can be interpreted if you want in that direction. We have Second Nephi Chapter 5, which is basically the only chapter in the small plates that Nephi tells us anything about their arrival in the Americas and their interactions in the Americas. Nephi, in 2 Nephi Chapter 5, lists every single group of people that are going to be divided. It says, “Everyone, every Laman and Lemuel not following me,” and the family, and it says, “You know, Zoram is following me, and my brother Sam is following me, and my sister.” It lists every single one of them. And at the end of this list, which is a comprehensive list based on what we understand were the people on the boat that came with him, at the end of the list, it says, “And all others that wanted to follow me.” He had this thing about “all others” after he had exhausted the list of people that we know were with him. So, who else is “all others”?

And Sherem, in Jacob Chapter 7, looks like he’s an outsider. He’s familiar with the language; he’s familiar with the culture. Why do you have to say that about this individual when that individual should be part of your ethnic and language group? Why do you have to stress or emphasize or highlight that he knows about you guys, and that it took a long time for him to meet Jacob’s among the Nephites? How long would it take to meet someone in a group of 200–300 people, you know? So, he must have heard of him and found an opportunity to meet with him.

And there are plenty of others, you know, the concubine issues described by Jacob. The plural marriage, like how they were taking multiple wives and concubines. We know from the Bible that concubines are usually somebody not from your own family, tribe, or ethnic group. So, there are little hints here and there. I mean, we cannot, for sure, say, “Here it is, the evidence,” but it’s definitely not completely silent about this matter.

Scott: Thank you very much. That’s good. So, here’s the next question:

Q: Would the mixing of native populations account for the Lamanite curse of darker skin from Jacob 3:9?

A (Mike): Well, again, taking a scientific approach to what ancient people would have written, I mean, we understand the curse a lot differently today than the early Latter-day Saints did. Skins are represented, not skins like we see today. In fact, we actually see it even today. I mean, there are things that we learn as Latter-Day Saints — covenant Latter-Day Saints — that tie to skins and from Adam and Eve, that don’t necessarily apply to the physical touch skin. It has to do with a change of character, and that’s actually what’s been the case throughout ancient cultures. In most ancient cultures — and we still see it today — it’s always an “us and them” mentality. I mean, we’re the good guys, they’re the bad guys. The Book of Mormon is written by a group of people. We don’t have a book written by the Lamanites from their perspective, right? But, they’re the bad guys; they’re the outsiders. So, it was viewed culturally as that — a “skin of blackness” means that these people are loathsome. In fact, it’s mentioned in the Book of Mormon: “loathsome.” It’s because they’re the outsiders; they’re the bad people.

So, the curse is not anything to do with a physical change, but it has to do with being part of the covenant people. So, there’s a change in nature. When we’re baptized, we’re changed. We, in a sense, acquire a new skin as well. We become new creatures in Christ. Well, that’s, again, symbolically described many times as skins. This is a common theme throughout history and in the scriptures.

Scott: Thank you. Can you briefly describe the differing paradigms between DNA analysis that is used as evidence in a court of law versus DNA evidence that critics use to try to discredit the Book of Mormon? I’m not sure who that’s for.

Ugo: I can take that question. I do several courses for a forensic department at the University in New Haven, so I have come to learn very well about what constitutes genetic evidence versus what is maybe a genetic hint, or something that might point you in the right direction.

For something to be considered as an incriminating factor, you need to have an exact match with an individual or a relative, like the one you use for genealogical purposes, like ancestry, for example. They’re using that nowadays to actually find potential criminals in cold cases, but the reality is that’s only going to point to a suspect. Then, when you have the suspect, you need to collect an additional DNA sample from the suspect that exactly matches the DNA collected in the crime scene, and that’s what constitutes the evidence — not the fact that you’ve been able to reconstruct a potential link to the individual through DNA. You need the final DNA sample.

So, in our case, if we find a grave that says “Lehi” on it and we test the bones of that person, you know, then we can probably see how well that DNA fits with the Israelite model of what the DNA looks like. But until we have the exact match or the exact identification, what we’re going to do is gonna be a statistical analysis. You know, you’re going to get some sort of idea, a general idea, but not enough to create and constitute incriminating evidence. You know, does that make sense, with it? So, we have to be very careful. They will not take in a court setting something that you think could be, but it has to be an absolute match.

Scott: Thank you. To go along with that, how would you answer the critics stating the Book of Mormon has large populations — 23,000 Nephites is a common number tossed around — and thusly challenge the idea that Nephites were just a small tribe?

Mike: Well, they would have started off as a small tribe, but we know, you know, the whole point is that it was a small incursion into a larger population. That’s just it. How these numbers expand exponentially it’s because there were other populations there, so there was intermingling, there was admixture. And I mean, that’s actually, you know, a point in favor of the LDS scholarly approach — that they were a small incursion into this population. And again, if you become a Latter-day Saint and you were something else before, now you’re a Latter-day Saint; you’re part of that cultural population. You become a Nephite, you’re part of that. And so they can correctly claim thousands, or millions, or whatever numbers. You know, and even numbers, sometimes in ancient cultures — there were, you know, exaggerations and stuff. But nevertheless, the populations grew as people joined.

Ugo: Can I add one thing really quick?

I want to go back to the interpretation of skin color that was in the previous question. We as Europeans, with our classical model of understanding, which is what we inherited from the Greeks, we tend to interpret everything literally. When we say 1,000, we mean 1,000, one-to-one. When we refer to “skin,” we mean the skin, the organ of our body that we identify as skin. But that is a literal interpretation of writings. In the Semitic model those things had different meanings. There are several books that help you understand this. My good friend, sitting there in the audience, once gave me a book called Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes. It explains that, in reality, skin meant something different.

So skin, as Mike explained, is a symbol of the soul. You know, we still use words nowadays like “dark countenance” or “I have a bright idea.” These things identify positive and negative by using the imagery of light and shadows. The same thing goes with numbers, you know — “a thousand people” or “a million people” just means a lot of people to them. It was such a large number that it was hard to define or count. We tend to take that very literal, but that’s our problem interpreting the scriptures, not a problem with them writing these concepts.

Scott: Thank you. So, we’re out of time. I have one last question I’m going to blindside you with. Ready?

Has your uncle, Dieter Uchtdorf, read any of your books? [Laughter]

Mike: I know he’s read at least some of them.

Scott: Okay, thank you very much for your time, and Ugo, thank you for your time.

Endnotes & Summary

Summary: Genetic vs. Genealogical Ancestry and the Limits of DNA Evidence

In the concluding section, Ash and Perego explain the difference between genetic and genealogical ancestry, showing that one can be a descendant of a historical figure like Lehi without retaining any of that person’s DNA. Using concepts like the genetic isopoint and pedigree collapse, they demonstrate how DNA from small groups can disappear over time—especially when assimilated into much larger populations.

They emphasize that cultural identity, not genetic purity, defined who was considered a Nephite or Lamanite in the Book of Mormon. Just as terms like “Jew” or “Lamanite” can reflect affiliation more than biology, so too can ancestral claims in scripture be understood through a sociocultural lens.

The authors caution against misapplying modern forensic DNA standards to ancient population studies. Unlike courtroom evidence, ancient DNA research often deals in probabilities, not certainties. Citing scientists like Daniel Hartl and Jennifer Raff, they affirm that it would be statistically unlikely for Lehite DNA to survive detectably, and they stress that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Ultimately, they advocate for a nuanced, informed approach to both science and scripture, reminding us that revelation operates within human language and understanding—and that the Book of Mormon should be read in light of both its ancient worldview and our modern scientific insights.

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 2, 2023

- Duration: 50:34 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2023 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: DNA evidence, Book of Mormon historicity, population genetics, genetic drift, admixture, Israelite ancestry, Native American DNA, cultural identity, genealogical ancestry, scriptural interpretation, prophetic fallibility, revelation and assumption, ancient migration, lost 116 pages, Lehite assimilation, Lamanite identity, skin of blackness, forensic DNA standards, small vs. large population dynamics, limited geography model, paradigm shifts, scientific literacy, genetic isopoint, Nephite and Lamanite labels, ancient worldviews, cultural exonyms, Church statements on DNA and geography

Common Concerns Addressed

Concern: DNA evidence disproves the Book of Mormon

Many critics argue that the absence of Israelite DNA among Indigenous Americans proves the Book of Mormon is fictional.

Clarification: This talk explains why expecting to find Lehite DNA is scientifically unrealistic. Ash and Perego show how genetic drift, population dynamics, and intermixing with larger native populations would make such DNA undetectable after 2,600 years.

Concern: The Church changed its narrative to hide past mistakes

Some claim that the Church’s shift from calling Lamanites the “principal” ancestors of Native Americans to “among” their ancestors is an attempt to quietly backtrack.

Clarification: The talk clarifies that this shift reflects improved scholarly understanding—not a retreat from doctrine. It underscores that earlier assumptions (including by Church leaders) were shaped by 19th-century worldviews, not revelation.

Concern: If prophets speak for God, how could they be wrong about things like race or population history?

Critics often cite perceived prophetic errors as reasons to question prophetic authority or reject Church teachings.

Clarification: The presentation distinguishes between revelation and assumption, explaining how prophets, like all humans, interpret truth through cultural lenses. Ash emphasizes that spiritual authority can coexist with human fallibility in non-revealed matters.

Concern: Cultural identity vs. biological ancestry—Who are the Lamanites today?

Some members and critics struggle to reconcile scriptural claims about Lamanite identity with modern scientific and genealogical evidence.

Clarification: The talk explains that “Lamanite” in the Book of Mormon refers to a sociopolitical and religious identity—not a genetic lineage. Cultural affiliation, not bloodline, defined group membership, much like terms such as “Jew” or “Christian” today.

Concern: Critics say Latter-day Saints are “moving the goalposts” to keep the Book of Mormon credible

Apologists are often accused of inventing new interpretations only when science contradicts previous beliefs.

Clarification: Ash and Perego show that the limited geography model and recognition of others in the Americas long preceded the DNA controversy. The shift is not ad hoc but grounded in decades of careful textual and archaeological scholarship.

Concern: Science and religion are in conflict

Many assume that scientific findings inherently contradict scriptural claims.

Clarification: This talk shows that faith and science address different questions and can complement rather than contradict each other. The speakers invite a mature, nuanced view of both scripture and evidence—one that acknowledges what science can and cannot prove.

Apologetic Focus

Topic: Population Genetics and DNA Evidence

Concern: DNA studies seem to undermine the claim that Book of Mormon peoples came from Israel.

Clarification: This talk explains how small migrating groups can lose genetic visibility in large populations over time. It outlines scientific concepts like genetic drift, admixture, and the genetic isopoint to demonstrate why the absence of Israelite DNA is expected, not troubling.

Topic: Historical Accuracy of the Book of Mormon

Concern: The Book of Mormon claims to describe ancient peoples in the Americas—but scientific findings show no evidence of these migrations.

Clarification: Ash and Perego show that the Book of Mormon never claimed to describe all ancient Americans. The limited geography model, supported by Church materials and academic research, provides a plausible historical context for the narrative.

Topic: Revelation and Prophetic Fallibility

Concern: If early prophets were wrong about who the Lamanites were, how can we trust their teachings?

Clarification: The talk distinguishes between revelation and assumption, using examples to show that prophets may express culturally shaped opinions in the absence of revelation. This framing strengthens trust in revealed doctrine while allowing space for human error.

Topic: Cultural vs. Genetic Identity

Concern: Critics argue that if there’s no genetic trace of Lehites, then “Lamanites” must be a myth.

Clarification: This presentation explains that Lamanite identity was based on religious and political affiliation, not DNA. Just as modern Jews or Christians may be converts or descendants, Lamanite identity functioned culturally within the text.

Topic: Harmonizing Science and Faith

Concern: Can faithful Latter-day Saints accept modern science without compromising their beliefs?

Clarification: Ash and Perego argue that scientific tools can enrich—not diminish—faith when properly understood. The talk encourages believers to engage scientific findings with humility, recognizing their limits and their value.

Share this article