Summary

Gardner explores how the Book of Mormon fulfills its two central purposes, as stated on the title page. One, to show the great deeds the Lord has done for the House of Israel. And two, to convince both Jews and Gentiles that Jesus is the Christ, the Eternal God. He explains how Mormon, the compiler of the Book of Mormon, illustrates the coming of Christ through both prophecy and fulfillment. And how he conveys God’s continuing relationship with His covenant people as a promise that what God has done in the past, He will continue to do in the future.

Brant A. Gardner

Richard Dilworth Rust declared: “One mark of great literature is that it shows a concept concretely and avoids telling or explaining it abstractly. Appropriately, then, the Book of Mormon purposes to ‘show unto the remnant of the House of Israel what great things the Lord had done for their fathers.’”[1] Immediately after that statement on the Title Page, Moroni added: “And also to the convincing of the Jew and Gentile that Jesus is the Christ, the Eternal God, manifesting himself unto all nations.” According to Moroni, Mormon had two overriding purposes, and he wrote the Book of Mormon to show both.

Showing That Jesus Is the Christ, The Eternal God

Joseph Smith taught: “It is necessary for us to have an understanding of God himself in the beginning. If we start right, it is easy to go right all the time; but if we start wrong, we may go wrong, and it will be a hard matter to get right. There are but a very few beings in the world who understand rightly the character of God.”[2] Long before Joseph Smith, Mormon understood the same problem. It is essential that one understand the true God. That’s why Mormon did not simply write to show that God was more powerful than other competing gods. As we see so often in the Old Testament.

From the book of Mosiah to the first part of 3 Nephi, Mormon told tales of apostates. Some may have completely adopted foreign gods. Some, however, such as the priests of Noah, continued to teach the Law of Moses. The language of the Title Page is so familiar to modern readers that we easily miss the reason that it is such an important part of Mormon’s message. The very first statement is that Jesus is the Christ. In more time-appropriate language, this would be Jesus is the Messiah. That shifts the framing of the concept just a little for a modern reader. This shift is to dramatically reframe.

The Book of Mormon Messiah is not the familiar military leader from the Old Testament. Beginning with Lehi and Nephi, the teaching about the Messiah is intimately linked to his atoning mission (1 Ne. 11:19).

Declaring God’s Atoning Mission

Speaking of the Jews Nephi1 declared: “But, behold, they shall have wars, and rumors of wars; and when the day cometh that the Only Begotten of the Father, yea, even the Father of heaven and of earth, shall manifest himself unto them in the flesh, behold, they will reject him, because of their iniquities, and the hardness of their hearts, and the stiffness of their necks” (2 Nephi 25:12).

Mormon’s purpose wasn’t to declare God, but to declare God’s atoning mission as the Messiah. The Nephite God was Yahweh, just as he had been in the Old World. Mormon included numerous prophecies concerning what for most of Nephite history was a God of the future. Abinadi specifically declared: “I would that ye should understand that God himself shall come down among the children of men, and shall redeem his people: (Mosiah 15:1).

Mormon showed that there were prophecies. He dramatically fulfilled his task of showing when a group of people gathered at a temple in Bountiful and witnessed God himself descend.

The description of the event in 3 Nephi 11 captures some of the wonder of that event:

A Man Descending Out of Heaven

And now it came to pass that there were a great multitude gathered together, of the people of Nephi, round about the temple which was in the land Bountiful; and they were marveling and wondering one with another, and were showing one to another the great and marvelous change which had taken place.

And they were also conversing about this Jesus Christ, of whom the sign had been given concerning his death.

. . . .

And behold, the third time they did understand the voice which they heard; and it said unto them:

Behold my Beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased, in whom I have glorified my name—hear ye him.

And it came to pass, as they understood they cast their eyes up again towards heaven; and behold, they saw a Man descending out of heaven; and he was clothed in a white robe; and he came down and stood in the midst of them; and the eyes of the whole multitude were turned upon him, and they durst not open their mouths, even one to another, and wist not what it meant, for they thought it was an angel that had appeared unto them. (vv. 1–2, 6–8)

Their God had undeniably come down. They also needed to know that Christ had completed the atoning mission. Yahweh’s descent did not demonstrate that. That demonstration came as he stood before them.

Wright’s Words

Mark A. Wright noticed

When Christ appeared to the Nephites, he may have been communicating with them according to their cultural language when he invited them to come and feel for themselves the wounds in his flesh. He bade them first to thrust their hands into his side, and secondarily to feel the prints in his hands and feet (3 Nephi 11:14). This contrasts with his appearance to his apostles in Jerusalem after his resurrection. Among them, he invited them to touch solely his hands and feet (Luke 24:39–40).

Why the difference? To a people steeped in Mesoamerican culture, the sign that a person had been ritually sacrificed would have been an incision on their side — suggesting they had had their hearts removed — whereas for the people of Jerusalem in the first century, the wounds that would indicate someone had been sacrificed would have been in the hands and the feet — the marks of crucifixion. [3]

The Wounds

The difference was not simply in the type of wounds. More importantly, the wounds defined the person who stood before the apostles in the Old World and stood again before those gathered in Bountiful in the New World. They knew Jesus had died; had witnessed his death. They needed to know that the very Jesus they had seen die was now the living being before them.

In Bountiful, the people knew that a living God had descended. They needed to know that this living being had once died. Marks in the hands and feet would not show them that. The killing wound in the side would. This God had descended to them in glory. But in another location had descended and died as a mortal. Just as Nephite prophets had declared.[4] The descent of their God clearly fulfilled both the prophecy that Yahweh would come down as well as that Yahweh would be Jesus the Messiah who provided the atoning sacrifice. After 3 Nephi, there was no more need for Mormon to show that Jesus is the Christ. Mormon no longer entered sermons or discussions of Jesus the Messiah.

Showing Unto the Remnant of the House of Israel What Great Things the Lord Hath Done for Their Fathers

When Mormon showed that Jesus is the Christ, he could do so with fulfilled prophecy. His message for his future audience required a different method. The phrase “what great things the Lord hath done for their fathers” hints at how Mormon intended to show his purpose for the remnant of the House of Israel. When Mormon wrote to show that Jesus is the Christ, it is clear why we think that was important. However, why would it be interesting to know that God had done great things in the distant past? The only way that showing “what great things the Lord hath done for their fathers” could have any impact at all for a future audience came from a cyclical worldview. What the Lord had done is evidence for what he will do.

Historical Consciousness and Things that Repeat

Humankind observed nature long before it observed anything that might be called history. Indeed, their ability to survive depended upon their ability to understand the natural world around them. One of the most important concepts nature taught early humanity was that repetition was inherent to existence. The sun rose and set on a regularly repeating pattern. The position of the sun along the horizon changed, but regularly repeated the same pattern every year. Stars had predictable movements. Seasons might not be precise, but they clearly repeated. Thus, things that repeat became important to the intellectual world of our ancestors.

Mormon participated in a worldview that saw history as a thing that repeated. The cycles might be longer or shorter, but they were cycles nonetheless. It is an idea that he shared with multiple Mesoamerican cultures. It could easily have been inherited from Old World Israel.[5] Geoffrey F. Spencer described that historical worldview:

The genius of the Old Testament prophets was not that they produced oracles about future events but that they were inspired to understand God’s action in their people’s history and in the crises of their own days. Only in this context could they assert with confidence the plan of God’s judgement and salvation in the time to come. History becomes prophetic because what God has done becomes the key to what he will do.[6]

Repeated Patterns

Therefore, when Mormon showed what great things God had done for the Lamanite fathers, he explicitly promised that God could and would do the same for his future audience. Inside that framework, Mormon had to show the repeated patterns that would provide the promise for the future.

Understanding how Mormon expanded upon this concept of repeating time and history benefits from a slight sidestep into Hebrew poetry. Scholars have long recognized that Hebrew poetry consists of different types of repeated phrases. Thus, in transmitting the larger stories, Hebrew storytellers and later writers used literary repetition. There are two that are important to the discussion of Mormon’s use of historical repetitions.

Synonymous Parallels

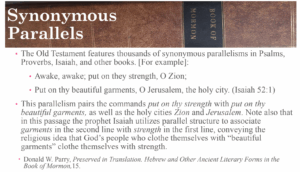

One type of poetic form was two lines with parallel meanings. Donald W. Parry explains and provides examples of literary parallelisms:

The Old Testament features thousands of synonymous parallelisms in Psalms, Proverbs, Isaiah, and other books. [For example]:

Awake, awake; put on they strength, O Zion;

Put on thy beautiful garments, O Jerusalem, the holy city. (Isaiah 52:1)

This parallelism pairs the commands put on thy strength with put on thy beautiful garments. As well as the holy cities Zion and Jerusalem. Note also that Isaiah utilizes parallel structure to associate garments in the second line with strength in the first line. This conveys the religious idea that God’s people who clothe themselves with “beautiful garments” clothe themselves with strength.[7]

Thus, a simple repetition is that the same thing occurs, hence a synonymous parallel. However, the expectation of the repetition highlights when the parallels intentionally reverse expectations. Parry notes that an “Antithetical parallelism generally consists of two lines and is characterized by an opposition or contrast of thoughts (that is, an antithesis) between two lines.”[8] As an example, he lists Isaiah 65:14.

Antithetical Parallels

Behold my servants shall sing for the joy of heart,

But ye shall cry for sorrow of heart.

Scholars have extensively documented many examples of literary parallels in the Book of Mormon. Synonymous or antithetical parallels had the two lines in close contact. However, Mormon’s thematic parallels require a wider vision of the text. Nevertheless, Mormon used both synonymous and antithetical thematic parallels.

In the following discussion, multiple examples of synonymous thematic parallels will be examined. Followed by the important cases of the antithetical thematic parallels. First, we must make clear that the discussion of Mormon’s use of parallels hits an immediate wall. We lost what Mormon wrote as the beginning of his book, and the small plates replaced it with the same basic stories. But those were different authors with different purposes and different writing styles.

Although we have the important history, we have lost the way Mormon couched that history for his own ends. The prevalence of thematic parallels in the books from Mosiah through 3 Nephi are sufficient to establish thematic parallels as an element of Mormon’s art. It is improbable that Mormon only began those thematic parallels in the book of Mosiah. Thus, the lost pages must have contained the first element of thematic parallels, which we can infer from the second element preserved in Mormon’s record. For convenience in following the historical arcs, this examination will begin with those implied thematic parallels. This beggars patience as the concept becomes more established in the book of Mosiah.

Thematic Parallels Beginning in the Lost Pages

The lost 116 pages consisted of the book of Lehi and the beginning chapters of the book of Mosiah. There have been two attempts to recover what might have been in the lost 116 pages which were the original opening of Mormon’s book.[10] Neither of those speculative reconstructions suggested a missing part of a thematic parallel. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that Mormon saw a fundamental shift in Nephite history occurring between the book or Lehi and the book of Mosiah. There is a thematic parallel between Lehi and Nephi establishing the Nephite nation and the new Nephite nation established under Mosiah1.

| Lehi/Nephi | Mosiah1 |

|---|---|

| Lived in the land of his inheritance | Lived in the land of first inheritance (the common designation for the land of Nephi) |

| God warns that Lehi’s life is in danger | God warns him that his people’s lives are in danger |

| Flees with his family and leaves the land of his inheritance | Flees with his people and leaves the land of their first inheritance |

| Arrives in a new land | Arrives in a new land where he encounters a new people with a different religion and language |

| Nephi becomes king over the newly established city | Mosiah1 becomes king over the newly united people. |

The exodus from the land of Nephi to the land of Zarahemla was an historical event. Mormon added meaning beyond history to that event. By writing Mosiah1 as a thematic parallel to the origin story of the Nephite nation, Mormon declared that there was a renewed Nephite nation in the land of Zarahemla. That renewal became explicit when King called for a newly united people under a new name and a new covenant with their God (Mosiah 4).

Implication

Positing this thematic parallel has an important implication. Scholars have long noticed that Nephi never mentioned meeting the people already inhabiting the new world. Even though archaeology tells us that there were other people present. However, if we read the beginning of the Nephite nation through Mormon’s thematic parallel, the meeting with the Mulekites undoubtedly paralleled Lehi and his family meeting of a new people who had a different language and religion. That point would have been important for Mormon’s thematic parallel. But it obviously wasn’t important for the reasons Nephi wrote of those same events.

There is a secondary thematic parallel where both sides of Mormon’s parallel have been lost. Words of Mormon 1:13–16 describes events just prior to King Benjamin’s speech. There was a war with the Lamanites. Verse 16 notes that there were also “many dissensions away unto the Lamanites.” It is possible that Mormon saw this dissension to the Lamanites as parallel to the original Lamanite dissension.

A much longer thematic parallel is Nephi1’s creation of the Nephite nation and Nephi3’s creation of a new Nephite nation in 4 Nephi. Prior to Christ’s arrival, the Gadiantons succeeded in dissolving the Nephite nation into tribes. Following Christ there were no -ites. To tell his story of the Nephite nation, Mormon needed to have Nephites during his days. Mormon likely gave Nephi3 that name so he could become the ruler of the reconstituted and reconstructed Nephites.[11] By recording two thematic parallels of the renewal of the Nephite nation (under Mosiah1 and Nephi+), Mormon reinforced the cyclical nature of history. Having happened twice before, a future renewal of the Nephite nation, defined as a covenant people, became implied prophecy.

Thematic Parallels Beginning in the Book of Mosiah

We lost the introduction that would have tied together all the stories Mormon told from Mosiah to 4 Nephi. That story likely appeared in the early chapters of Mosiah, which were lost along with the book of Lehi. Were it not for the book of Omni, we would forever have lost the first half of the important pairing of Mosiah1 and Mosiah2.

It is in the book of Omni that we learn that after Mosiah1 arrived in Zarahemla, the Nephites had their first introduction to the Jaredites.

And it came to pass in the days of Mosiah, there was a large stone brought unto him with engravings on it; and he did interpret the engravings by the gift and power of God. And they gave an account of one Coriantumr, and the slain of his people. And Coriantumr was discovered by the people of Zarahemla; and he dwelt with them for the space of nine moons. It also spake a few words concerning his fathers. And his first parents came out from the tower, at the time the Lord confounded the language of the people; and the severity of the Lord fell upon them according to his judgments, which are just; and their bones lay scattered in the land northward. (Omni 1:20–22)[12]

Moroni’s Editing

This is the first part of a thematic parallel between Mosiah1 and Mosiah2. Perhaps Mormon manipulated their names so readers would more easily understand they should see the two rulers as thematic parallels. The parallels are deeper than the shared name:

| Mosiah1 | Mosiah2 |

|---|---|

| King in Zarahemla | King in Zarahemla |

| Ruled over a newly united people | Ruled over a newly reunited people (after Benjamin renewed the covenant) |

| Translated a Jaredite record that involved Coriantumr | Translated a Jaredite record that ended with the last king, Coriantumr |

| Created a new government combining Nephites and Zarahemlaites under a single king. | Created the reign of the judges |

Mormon did not directly quote from the Jaredite records. Indeed, were it not for Moroni’s editing of the book of Ether, we might not know the source for many of the themes Mormon based on the Jaredite record. It is unclear how Mormon understood that his readers would see the thematic parallels he used. He did promise that the book of Ether would be entered into his record at a future point (Mosiah 28:19).

Undergirding the Nephite story from the book of Helaman to battle at Cumorah was Mormon’s thematic parallel between the Jaredites and the Gadiantons. Both Jaredites and Gadiantons had secret combinations. For both the Jaredites and the Gadiantons, their secret combinations worked to destroy a previously covenant people. Mormon made that thematic parallel explicit in Helaman 2:12–14:

Gadiantons as Destroyers of Nations

And more of this Gadianton shall be spoken hereafter. And thus ended the forty and second year of the reign of the judges over the people of Nephi. And behold, in the end of this book ye shall see that this Gadianton did prove the overthrow, yea, almost the entire destruction of the people of Nephi. Behold I do not mean the end of the book of Helaman, but I mean the end of the book of Nephi, from which I have taken all the account which I have written.

The righteous Jaredites perished by secret combinations. The righteous Nephites would meet their demise through secret combinations embodied in the various groups Mormon labeled Gadiantons.[13] One thematic parallel that is unique to Moroni is the linking of the Jaredite hill Ramah with the Nephite hill Cumorah (Ether 15:11). Mormon did not make that explicit connection. But it fits within the framework of the thematic parallel between the demise of the Jaredites and that of the Nephites.

Text Introducing the Jaredite/Gadianton Thematic Parallel

The most significant parallel is the connection between the two Mosiahs and a Jaredite record. Mormon highlighted the importance of that connection by twice telling the story of finding the book of Ether. The way Mormon told that story also reveals information about how he used his source material to create his story.

The book of Omni preserves a story from the early part of Mosiah:

And now I would speak somewhat concerning a certain number who went up into the wilderness to return to the land of Nephi; for there was a large number who were desirous to possess the land of their inheritance. Wherefore, they went up into the wilderness. And their leader being a strong and mighty man, and a stiffnecked man, wherefore he caused a contention among them; and they were all slain, save fifty, in the wilderness, and they returned again to the land of Zarahemla.

And it came to pass that they also took others to a considerable number, and took their journey again into the wilderness. And I, Amaleki, had a brother, who also went with them; and I have not since known concerning them. (Omni 1:27–30)

The Loss of the Story

The loss of that story from early in the book of Mosiah means that when Mormon returns to the story, it has only a brief mention.

And now, it came to pass that after king Mosiah had had continual peace for the space of three years, he was desirous to know concerning the people who went up to dwell in the land of Lehi-Nephi, or in the city of Lehi-Nephi; for his people had heard nothing from them from the time they left the land of Zarahemla; therefore, they wearied him with their teasings. And it came to pass that king Mosiah granted that sixteen of their strong men might go up to the land of Lehi-Nephi, to inquire concerning their brethren. (Mosiah 7:1–2)

The brief mention in the book of Mosiah belies the importance of what will come. These two verses introduce the most complicated combination of the narration time. They also include a flashback that would require two stories that occurred simultaneously.

Following the large plate timeline, Mormon told the story of Ammon and his company’s departure to find the people who had been separated. Mormon does not give much of the backstory of Limhi’s people but concentrates on the meeting between Ammon and Limhi. Even though the story of Ammon and Limhi could only be entered into the Nephite record after Limhi’s people returned to Zarahemla, Mormon skips any intervening Nephite history. He enters the story of Ammon’s meeting with Limhi in the order it would have appeared on the large plates.[14] The story of Ammon traveling to the land of Nephi and meeting with Limhi covers Mosiah V (7–8).

Zeniff’s Record

What Mormon does next is interesting. Mormon tells the “real time” story up to a point, and then stops. He abruptly shifts the timeline to the past by inserting Zeniff’s record (Mosiah VI (9–10). Zeniff is the one who led the party to the land of Nephi. He is the grandfather of King Limhi with whom Ammon had been conversing. Thus, Mormon begins to tell a parallel story that took place in a different land and at an earlier time by inserting a record of that people. That story follows the Zeniffite timeline until the people of Limhi and Alma both return to Zarahemla. There the large plate timeline picks up the story at the end of Mosiah 24, which is the end of the inserted record of Alma1.[15]

Why did Mormon elect to enter the Zeniffite record after Ammon’s meeting with Limhi? The answer is inherently speculative. But it is important to note the final event of Ammon’s meeting with Limhi that Mormon recorded before his abrupt shift to the different record and time. He waited until Limhi told the story of sending a search party to find Zarahemla. That search failed in the main goal, but rather found the land of a destroyed people. They brought back artifacts. Most importantly, they brought back a record.

Translation

Limhi was anxious to have the record translated, and asked Ammon if there was one who could do so. Ammon declared that there was a seer in Zarahemla. “A man that can translate the records; for he has wherewith that he can look, and translate all records that are of ancient date” (Mosiah 8:13). There are many important stories Mormon told about the people of Zeniff. These include Abinadi before Noah and Alma1’s conversion and creation of a church. However, before telling those stories, Mormon introduced the Jaredite record and Mosiah2 as the translator.[16] Mormon never told any story without a reason. Mormon did not haphazardly stop right at the point where he introduced both the book of Ether and established the second part of the thematic parallel between Mosiah1 and Mosiah2.

Finding the Jaredite Record

In the context of the different record, Mormon retold the story of finding the Jaredite record. In this second telling of the story, Mormon repeated the essentials:

Now king Limhi had sent, previous to the coming of Ammon, a small number of men to search for the land of Zarahemla; but they could not find it, and they were lost in the wilderness. Nevertheless, they did find a land which had been peopled; yea, a land which was covered with dry bones; yea, a land which had been peopled and which had been destroyed; and they, having supposed it to be the land of Zarahemla, returned to the land of Nephi, having arrived in the borders of the land not many days before the coming of Ammon.

And they brought a record with them, even a record of the people whose bones they had found; and it was engraven on plates of ore. And now Limhi was again filled with joy on learning from the mouth of Ammon that king Mosiah had a gift from God, whereby he could interpret such engravings; yea, and Ammon also did rejoice. (Mosiah 21:25–28)

Importance

The physical process of engraving upon plates had to have been laborious. Despite the labor, Mormon elected to tell this story twice. His plausible reason for telling the very same story in two different places was to highlight the importance of that event.[17] The translation of the book of Ether provided Mormon with this thematic parallel of secret combinations between the Jaredites and the Gadiantons.

Mormon supported the thematic parallel of Jaredites and Gadiantons by using vocabulary that served as foreshadowing of destruction. For example, when Mormon inserted geographic information in Alma 22, he labeled the land northward as Desolation. “It being so far northward that it came into the land which had been peopled and been destroyed, of whose bones we have spoken” (Alma 22:30).[18] Mormon obviously knew that his Nephites were seeing their end in that very land Desolation. He also used the theme of desolation in connection with destruction when the city of Ammonihah was destroyed, becoming the “Desolation of Nehors” (Alma 16:11).

The Thematic Parallel between Jaredites and Mulekites

We do not have the Mormon’s story of Mosiah1’s meeting with the people of Zarahemla. We cannot know how he couched that story. However, later information tells us that Mormon saw the people of Zarahemla (descendants of Mulek) as a destructive force that he linked to the Jaredites. The strongest connection between the people of Zarahemla and the Jaredites comes when Mormon declares that they come from the same place.

The Nephites had taken possession of all the northern parts of the land bordering on the wilderness, at the head of the river Sidon, from the east to the west, round about on the wilderness side; on the north, even until they came to the land which they called Bountiful. And it bordered upon the land which they called Desolation, it being so far northward that it came into the land which had been peopled and been destroyed, of whose bones we have spoken, which was discovered by the people of Zarahemla, it being the place of their first landing. (Alma 22:29–30)

Mormon records that the people of Mulek first landed in Jaredite territory around the time that Lehi had landed further south.[19] When Mosiah1 found the people of Zarahemla, they were no longer in the place where they landed. And no longer in Jaredite lands. Nevertheless, they were tied to those lands of origin. And to the final Jaredite ruler, Coriantumr, who lived among them for several months.

Connection

For Mormon, that connection between the people of Zarahemla (as descendants of Mulek) and the Jaredite land of Desolation created a conceptual link to a dangerous potential enemy. Until the explicit appearance of the Gadiantons, the greatest danger to the Nephite nation came from Mulekites. In Mormon’s thematic parallels, Mulekites serve as stand-ins for the Gadiantons. The Gadiantons take over in the book of Helaman.

Given Mormon’s manipulation of names,[20] it cannot be certain that the people he has descending from Mulek descended from a person with that very name. The reason that name is in question is that Mormon makes great use of it. A different name might not have so easily fit his didactic purposes.

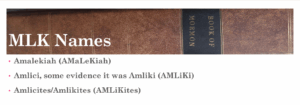

MLK was a Hebrew root for “king.”[21] Thus the name Mulek carries with it the connotations of kingship. It is not only the Mulek name, but his declared heritage as the son of the king. Mormon creates names for his antagonists that reflect their Mulekite inherited desires for a king. Thus, Mormon tells the story of Amalekiah (AMaLKiah) who led a rebellion that intended to reinstate a king. The implied schism with MLK-named men who desired to be king is made explicit beginning in Alma 51:5 where Mormon introduces king-men who dethrone Pahoran.

A Reason for the Confusion

The name we have as Amlici may actually have been intended as Amliki. Making it an MLK name. Royal Skousen notes that the original is not extant at this point. In the printer’s manuscript the name of the person appears to be consistently spelled Amlici. However: “On the other hand, the first two occurrences in [the printer’s manuscript] of Amlicites (in Alma 2:11–12) are spelled Amlikites.[22] There is some confusion about peoples named Amalekites and Amlicites in the Book of Mormon. A plausible reason for the confusion is that Mormon used the same MLK name to describe different groups.[23] Mormon cared that they were dissenters. He cared less about the specific details.

Thematic Antithetical Parallels and Repentance

The predominant use of thematic parallels was to present them as synonymous. When Mormon deviates from his predominant methodology it signals that readers should pay attention. When there is a thematic antithetical parallel, it occurs in a context that suggests that Mormon uses that reversal to show repentance. Too many of Mormon’s thematic parallels, and events he personally witnessed, dealt with thematic parallels that showed Nephite apostasy. Mormon’s message, although dealing with difficult apostasy and destruction, was not one of melancholy or submission. It is a message of redemption through Jesus the Christ and the process of repentance. Mormon showed repentance through his antithetical parallels.

Amulek (AMuLeK) has a MLK name and lived in Ammonihah, a city that was antithetical to the Nephite religion. Nevertheless, Amulek heeds an angel and shelters Alma2. Amulek becomes Alma2’s stalwart missionary companion. The reversal in the expectation behind the MLK name provides the antithetical parallel. Amulek was previously at least among apostates, but he became an example of righteousness.

Alma and Alma

Mormon also tells the stories of Alma1 and Alma2. Conveniently bearing the same name to assist in seeing the thematic parallels. Both Almas taught against the Nephite religion. Had a dramatic event that triggered their repentance process. Became important to the development and structure of Nephite government and religion.[24]

Mormon used a Jaredite name to signal the thematic antithetical parallel embodied in one of Alma2’s sons. When Mormon wrote about Alma2 giving a final blessing to his sons, he spent time on Helaman but gave a similar blessing to Shiblon. Mormon’s version of the blessing spends the most time with the third son, Corianton. Corianton is a Jaredite name. By using that name, Mormon primed his readers for the story of an apostate. Indeed, we get that story. However, we often miss that Corianton reverses that apostasy and becomes a stalwart missionary.[25] Hence, Corianton becomes an example of an antithetical parallel of the expectation of the name.

Thematic Antithetical Parallel Mormon’s

Repentance was Mormon’s ultimate thematic reversal. While Mormon’s daily language may have been long different from ancient Hebrew, the biblical concept of repentance may have colored any other word used for that concept. The Hebrew word teshuvah is typically translated as repentance, but it literally means a return, a turning back to a previous state.[26] For Mormon, repentance meant returning to the covenant body of the House of Israel. Mormon’s first purpose to show that Jesus the Christ was accomplished by showing fulfilled prophecy. That method of showing was unavailable for his second purpose.

The second purpose was to “show unto the remnant of the House of Israel what great things the Lord had done for their fathers.” That showing consisted of demonstrating repentance to return to the covenant. The covenant had not changed and remained (and remains) available to all who would repent and return to it. That hope underlay Mormon’s final message, directed to future Lamanites:

Mormon’s Final Message to the Lamanites

And now, behold, I would speak somewhat unto the remnant of this people who are spared, if it so be that God may give unto them my words, that they may know of the things of their fathers; yea, I speak unto you, ye remnant of the house of Israel; and these are the words which I speak:

Know ye that ye are of the house of Israel. Know ye that ye must come unto repentance, or ye cannot be saved. (Mormon 7:1–3)

Mormon set the stage for a future return to the House of Israel by presenting a thematic parallel between two conversion stories. The first, and most explicitly described, was the conversion of the people who eventually took upon themselves the name Anti-Nephi-Lehies. Mormon told their story in detail. Including the incident where they gave up their weapons of war and vowed not to take them up again. The Anti-Nephi-Lehies tragically demonstrated the power of that vow when apostate-Nephite led Lamanites fell upon them and killed so many. We rightly read this as a story of their great faith, and it was. However, if we focus too much on faith we miss the real reason for the story, which is Lamanite repentance. The Anti-Nephi-Lehies were non-covenant Lamanites. But upon conversion and acceptance of the gospel became at least as righteous as the Nephites. Perhaps even more.

Anti-Nephi-Lehies/Nephi and Lehi Converts

The thematic parallel to that story is told in Helaman 5. Just as missionary brothers went to Nephite lands and converted the Anti-Nephi-Lehies, so in Helaman 5 do two brothers, Nephi and Lehi, go to Lamanites and convert a body of people. The parallel to the Anti-Nephi-Lehies is explicit in Mormon’s summary of their missionary efforts:

And it came to pass that they did go forth, and did minister unto the people, declaring throughout all the regions round about all the things which they had heard and seen, insomuch that the more part of the Lamanites were convinced of them, because of the greatness of the evidences which they had received. And as many as were convinced did lay down their weapons of war, and also their hatred and the tradition of their fathers. (Helaman 5:50–51)

Given Mormon’s penchant for using names to further his story, it is plausible that Mormon intended the names Anti-Nephi-Lehi and the names of the later brothers, Nephi and Lehi, as signals to his readers that they should see the thematic parallel between the two stories.

Mormon further demonstrated the ability of Lamanites to not only repent, but to become a righteous people. They could send the prophet Samuel the Lamanite to preach to the Nephites. The prophet’s name was Samuel, but Mormon intentionally underscored that this was a Lamanite prophet. Mormon highlighted the reversal of expectation by implying that these Lamanites had become more righteous than the Nephites. That was the historical story, but the cyclical history story was that Lamanites could do so again. This pattern repeated in the past and can be expected to repeat in the future.

Conclusion

Mormon showed that Jesus is the Christ, the Eternal God by demonstrating that it was fulfilled prophecy. The prophecy was that God himself would come down. Mormon wrote the story of when God himself came down to the people gathered in Bountiful.

Mormon still needed to fulfill his desire to show a future remnant of the House of Israel. Nevertheless, Mormon showed that in the repeating nature of history, the miracles and promises that God had made with their Fathers were available to them. Even more importantly, Mormon used the story of the Anti-Nephi-Lehies to show that repentance was possible. Repentance could result in true righteousness. He reinforced that historical story with a latter thematic parallel perhaps linked by the names of the missionaries who converted the later people, Nephi and Lehi. The conversions were similar. In the repeating cycles of history, there was already a demonstrated repeated pattern in which future readers can have faith that their repentance can likewise unite them with the covenant God made with the House of Israel.

Thank you.