Introduction

Scott Gordon: Our next speaker is Keith Erekson. He is an author, teacher, and public historian who has published on topics such as politics, hoaxes, Abraham Lincoln, Elvis Presley, and Church history. With that brief introduction, I’ll now turn the time over to Keith Erekson.

Presentation

(Keith Erekson) Wow, thank you all for being here today. I’m just honored and humbled by your presence, and I hope that I will do well enough for you. I want to thank Scott and the organizers, Delayna—this is something I’ve been hearing buzz about this conference for the past few days. People have been emailing, asking, “What do you think of this?” And this is great. So it’s fun to be here today and just feel the excitement in the room. Thank you for being here.

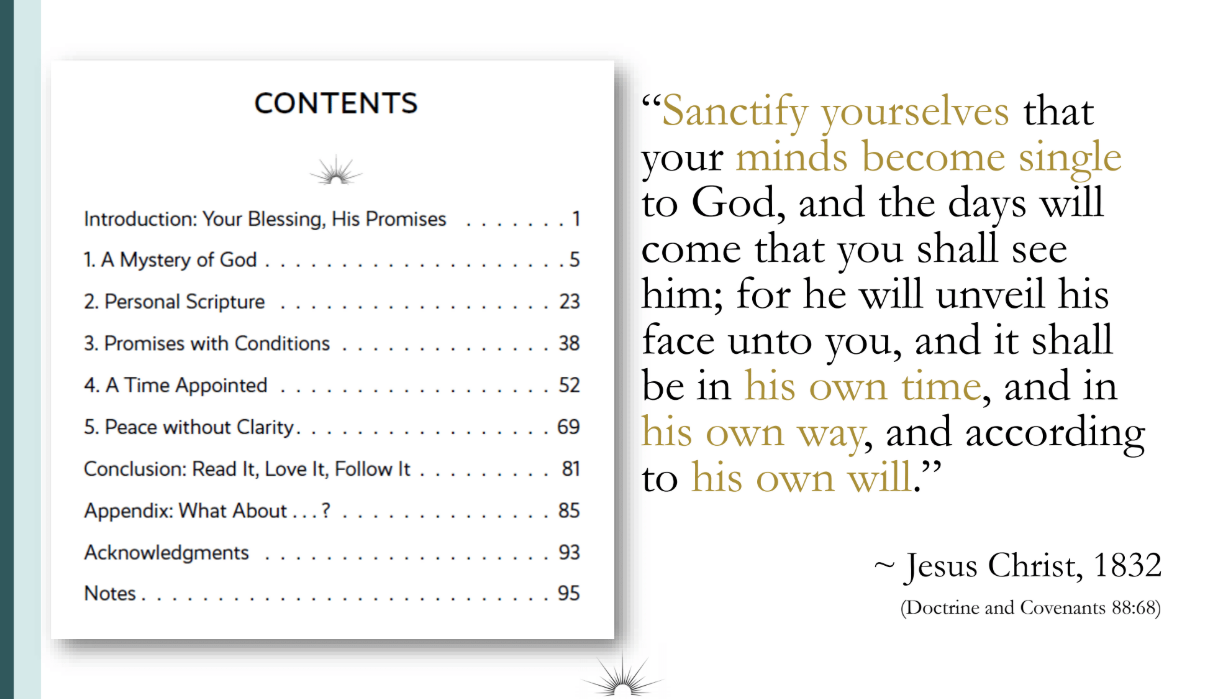

They have very kindly asked me to talk about a book that I have recently written, which was published in the last year, about patriarchal blessings.

Background on my Book

I thought I’d start by telling you a little bit about where the book came from and then talk about what is inside it. So, part of this began with me, right? Isn’t that where books come from? I received a patriarchal blessing when I was 16 years old, and there were things in it that I wondered about. They didn’t make sense to me—I didn’t know what they meant or how they would come to pass. I had one secret benefit that not everybody has: the patriarch who gave me my blessing was my grandfather, and he had been a patriarch for about 20 years before he gave me my blessing. Mine was number 1,393 on the list of blessings he’d given.

For the next 15 years, between my blessing and the time that he passed away, we had several conversations where we talked about patriarchs and blessings and how things worked. He was always very clear that he wouldn’t interpret it for me. I said, “That’s fine, just tell me how things go.” Then nine years ago, I stopped being a history professor and came to work for the Church, in the Church History Department. I served as the director of the Church History Library, which, among many things in our collection, is the repository for millions of patriarchal blessings.

During my time in that role, we were working with a large and fantastic team of talented people in developing an online system for patriarchs to submit their blessings online. People who lost their blessing, or maybe it was a blessing of an ancestor, could request it online and receive a copy. We spent lots of time and meetings talking with Church leaders, patriarchs, and local leaders. I felt like I learned so much along the way that I should share these insights. It didn’t seem fair to keep them all to myself.

I approached a couple of publishers, and they rejected the manuscript. I shouldn’t tell you this—you’re probably thinking, “Oh, what’s wrong with the manuscript?” I’m not interested, but let me tell you the context. The context they told me was, well, there already are books about patriarchal blessings written for 15-year-olds. There are too many on the market, and so there’s not a need for another book. It took me a while to get publishers to listen and say, “That’s not what this book is.” They would see the title and not be interested. I said, “This book is not about that. This book is the next book to those books. This book begins with, ‘You got your patriarchal blessing. Now what? What do you do with it? How do you make sense of it?’ This isn’t about wearing your Sunday best, fasting, and going to meet the patriarch to get it. This is about your relationship for the rest of your life.”

And the publishers would say to me, “Well, is there a market for that?” And I said, “Well, I mean, you’re the market people. I’m not a market person, but it strikes me that there are a couple thousand kids that turn 15 every year, and there are millions of Latter-day Saints who have a patriarchal blessing in their pocket that they’re wondering about. They got it, and they’re like, ‘Oh, okay, yes.’ That’s what the book is for.”

Making Sense of Your Patriarchal Blessing

And so that’s the opening premise: How do I make sense of this thing that I’ve received from God? I frame it around the revelation that Jesus Christ gave in 1832, with specific counsel about learning about God, approaching God, and communicating with God.

The elements in this passage become the stepping stones throughout the book. “Sanctifying yourselves” is the idea that there are conditions—these blessings aren’t just handouts. You have to prepare yourself, and you have to meet conditions. “That your minds become single”—we’ve got a lot of things in our minds: there’s the text in the blessing, there’s the mind of God, and all of these things have to become united. This is a personal scripture for you, and how can you find that unity? Then you will see that these things will come to you in God’s own time. There’s an important sense of timing for thinking about blessings, in His own way. That’s the part that doesn’t always make sense to us.

Then there’s the last part: “according to His own will.” That’s where the book opens—God’s will is often a mystery to us, and so how do we understand these mysteries?

Now, there are a couple of other things going on in the book, kind of under the hood, that I’ll just point out here. One is that a lot of times when we talk about spiritual things, we end up—and I think it’s just because we’re products of our own time and place and culture—we end up talking in little slogans, quick little things that are kind of quippy. You can put it on a refrigerator magnet or on a meme on social media. I think we’ve taken the idea of principles of the gospel and shrunk them down to these snappy little slogans. One of the things I wanted to do with each of these five chapters is articulate a principle. And principles take hard work—hard mental work to construct, and then hard work to unpack and apply. So, each chapter unpacks principles in a way that talks through their approaches, what we find, and what that means when you actually try and do something with it.

The other thing going on here is that the heart of the book, the heart of the story, is experiences from people—real people. Latter-day Saints who lived in the past, some still here in the present, wrestled with their patriarchal blessing, trying to figure out what it meant. As a historian, I went through the archives and found these experiences, sometimes in journals, in private places, and other times shared in public settings. The people who shared these stories—we walk with them in this sacred space where they try to encounter, understand, and commune with God. I thought today I would kind of walk through each chapter, share an experience or two, and just help you see how it works.

Principle 1: Mysteries of God

The first principle I unpack here is that a patriarchal blessing is a mystery of God. The scriptures talk about mysteries a lot, but not in the way we talk about mysteries—it isn’t a murder mystery or something like that. When the scriptures talk about mysteries, they mean things that God knows that we don’t know. That’s what a mystery is when the scriptures talk about it. Many times, the scriptures include the idea that God wants us to know those things; He wants to share them with us. That’s why we’re given a patriarchal blessing—because there are things God knows about us that He wants to share with us.

So, what does it mean to approach your blessing like a mystery of God? I’ll share an experience that I hope can illustrate some of the things I hope it means.

A young woman named Julie Bangerter was in high school, and she visited her guidance counselor as she was preparing for graduation and figuring out what to do. The counselor looked at her test results and said, “You really shouldn’t be thinking about college. You’re not very good at this. Maybe some kind of manual labor, or just be a mom, but really, the thinking space isn’t the space for you.” Julie had received a patriarchal blessing, and she went back and looked at it. She felt like she needed to go on and receive more education. Her blessing—the message she felt there—moved her in that direction.

So, she did. She went to college, graduated from Brigham Young University, and later married. We more often know her as Julie Beck. She became the General Relief Society president, served on the general and executive committees for the Church Board of Education, and after her Church service, she was appointed to the Board of Trustees for Dixie State. Here’s a person advised by her trusted advisers not to go to college, who ended up serving on the board of two universities because her patriarchal blessing told her a mystery that contradicted the opinion of her trusted advisers.

Not a Destination but a Doorway

When we approach a patriarchal blessing as a mystery, one way to think about it is that it’s not a destination but a doorway. Often, we think about the text—we think, “Oh, I have a problem, let me read my patriarchal blessing, and the answer will be right there in the text. My blessing is the destination, I’m going to go there and find it.”

But if you think about your blessing as a doorway, it means all of the answers aren’t necessarily written in there. It didn’t tell Julie, “Yes, you need to go to college because you’re going to become part of the Board of Trustees for two universities.” Those details weren’t there, but it was a doorway—it was a doorway to the Lord for her to approach, ask for help, and receive it.

In practice, this means we may find ambiguity or open-endedness in our blessings. It doesn’t tell you which school to go to, which program, which person to marry, or which job to take. It will be open-ended, and it may feel a little bit loose, but that’s because it’s an invitation—not to be the destination and tell you everything to do, but to be the doorway that invites you closer to God so that He can give you additional information.

Some implications of this are that length isn’t relevant. If you’re worried that everything in your life is supposed to be in your blessing, then you might start worrying, “Oh no, it’s really short; there’s not enough there.” But if it’s a doorway to God, it doesn’t matter how many words are there—you’ve got the open doorway.

Also important to remember is that the interpretation belongs to the Lord. Your guidance counselor isn’t going to interpret it, your spouse won’t interpret it, your bishop won’t interpret it, and the patriarch won’t interpret it. The interpretation belongs to the Lord, and so if you want to understand it, you need to go and commune with Him.

Principle 2: Personal Scripture

Right, a second principle here is to approach a patriarchal blessing like personal scripture. A story I want to share here is from another young woman named Louisa Bingham.

She received a blessing as a younger person, and it promised her the gift of healing, which is kind of a remarkable thing to promise to a young woman in the early 20th century.

She received a blessing as a younger person, and it promised her the gift of healing, which is kind of a remarkable thing to promise to a young woman in the early 20th century.

She thought about this, read the scriptures about healing, and pondered over the concept of healing. However, not fully understanding it, she continued to move through her life. She completed her education, got married, and had children. She had one particular son who was always ill or getting sick.

One day, when he was a toddler, while she was preparing something, she sent him into the pantry to fetch an ingredient for the cooking. Well, he walked into the pantry, a little toddler-sized child, and knocked over a container of lye. The lye spilled all over him—on his face, hands, and skin. He immediately began to scream because of the pain. Louisa rushed in, and in an instant, she saw her son screaming. Desperately pleading for help, she had a sudden idea: she noticed a barrel of pickled beets, kicked the lid off the barrel, picked up her son, and plunged him into the barrel. The vinegar from the pickling counteracted the lye—an acid and a base counteract each other—and her son’s suffering was relieved in that moment of inspiration.

A few years later, her son was a little older. While outside doing the things boys do, he ended in a broken a window, which left a deep gash in him that wouldn’t stop bleeding. Louisa tried everything she could to stop the bleeding, but nothing worked. In a moment of desperation, she prayed for inspiration on what to do for her bleeding son. The idea came to her to go to her bureau where there was a clean pair of stockings. She took it out, placed it in the wound, and then lit the stockings on fire. The burned stockings cauterized the wound, and the bleeding stopped.

Yet again, when her son was 18 or 19, he developed a cold that wouldn’t go away. He couldn’t breathe properly, and he couldn’t sleep because of his difficulty breathing. Once more, Louisa turned to the Lord for help, and she received inspiration to put a burlap bag under his chin, wrap it around his neck, and fill it with sliced onions. Her son slept through the night and eventually recovered from his illness.

One of the things Louisa learned from her experiences was that, when she first received the promise of the gift of healing and studied the scriptures, she imagined it happening in a certain way—the way we often see healings happen in the scriptures. What she found, however, was that the spiritual gift of healing had natural fulfillments. There were natural ways in which this gift came to pass in her life.

Her son Harold, with her maiden name Bingham and her married name Lee, survived all of those incidents and later became an apostle and president of the Church. Louisa felt that this was the hand of God, as she understood His will.

Not a Map but a Liahona

When we approach our patriarchal blessings this way, we may sometimes find—just as we do in the scriptures—passages that are clear and specific, which we can easily understand and apply. Other times, scriptures teach us concepts, and we have to think about how those concepts apply. Sometimes, scriptures use symbolism, and if your blessing mentions names or symbols, like “light,” “water,” or “rock,” these are scriptural symbols that have meaning and can help you understand your blessing. Even the names of people—if your blessing says you can be like Ruth or like Ammon—this is an invitation for you to go and study those figures in the scriptures and learn about their experiences, seeing how their stories might connect with your own.

Your Lineage

There’s another important symbolic name in your blessing: the name of your lineage.

President Nelson recently taught that through the inspiration of the Holy Ghost, the patriarch declares a person’s lineage in the house of Israel. That declaration is not necessarily a pronouncement of a person’s race, nationality, or genetic makeup. Rather, the declared lineage identifies the tribe of Israel through which that individual will receive his or her blessings. This lineage is our symbolic connection to the family of Abraham and the covenants made to Abraham, which include promises that can come to us as part of his family.

Principle 3: Conditions

Blessings also have conditions, and these conditions are about things that happen in the future. Humans try desperately to anticipate and predict what will happen in the future, but we’re not very good at it. We come up with ideas that sound like really great solutions—like giving every child the exact same test and relying on that to predict everything they will do in their college and career. Rarely does that work. We study past patterns, saying, “Here’s where the wind was, and here’s where it’s blowing,” but we’re not totally sure if it’s going to rain on your house or not—better be safe. We study economic markets, looking for past trends, knowing that anything can happen tomorrow and disrupt those trends. Sometimes, we even resort to gambling odds—those are the best predictors we have. What are the odds in Las Vegas on something? Other times, people turn to astrology or palm reading. We’re trying to figure out what happens in the future, but our patriarchal blessings don’t work like that. They don’t work like any of the ways we try to predict the future as humans.

Not a Fortune Cookie but a Gift in Trust

It’s not a fortune cookie; it doesn’t tell you what will happen.

Here’s a story that illustrates this idea.

Carlos Godoy was a young man living in Brazil. He had finished his studies, was married, and had a family of young children. He thought he was doing well by the standards of the people around him in Brazil. He was happy with his life, his family, his children, and the opportunities he had.

Then, one day, an old friend visited from the place where Carlos had grown up. This friend had served as Carlos’s bishop, a few generations older, but now meeting Carlos as a young adult. They started talking, and the friend was pleased to hear about Carlos’s success. But then he said, “Carlos, everything seems to be going well for you—your family, your career, your service in the church—but if you continue to live as you are living, will the blessings promised in your patriarchal blessing be fulfilled?”

Carlos said that he had never thought about his patriarchal blessing this way. He had read it from time to time and thought that there would be some blessings in the future, but he had never thought about using it to evaluate what he was doing in the present to meet the conditions for the future.

Carlos and his family—he and his wife—talked things over, and they decided to change everything they were doing. He left his well-paying, good job. His family left Brazil and moved to another country so that he could earn an advanced degree. They went from a life of material ease, having everything they needed, to living in tiny grad student apartments, eating canned food and ramen. They struggled through those years. But when Carlos finished his studies and returned to Brazil, he got a job that was even better, paid even more, and opened up opportunities for his family, his children, and his church service. These were the things that he valued, and they enabled him to do what his patriarchal blessing had counseled him to do.

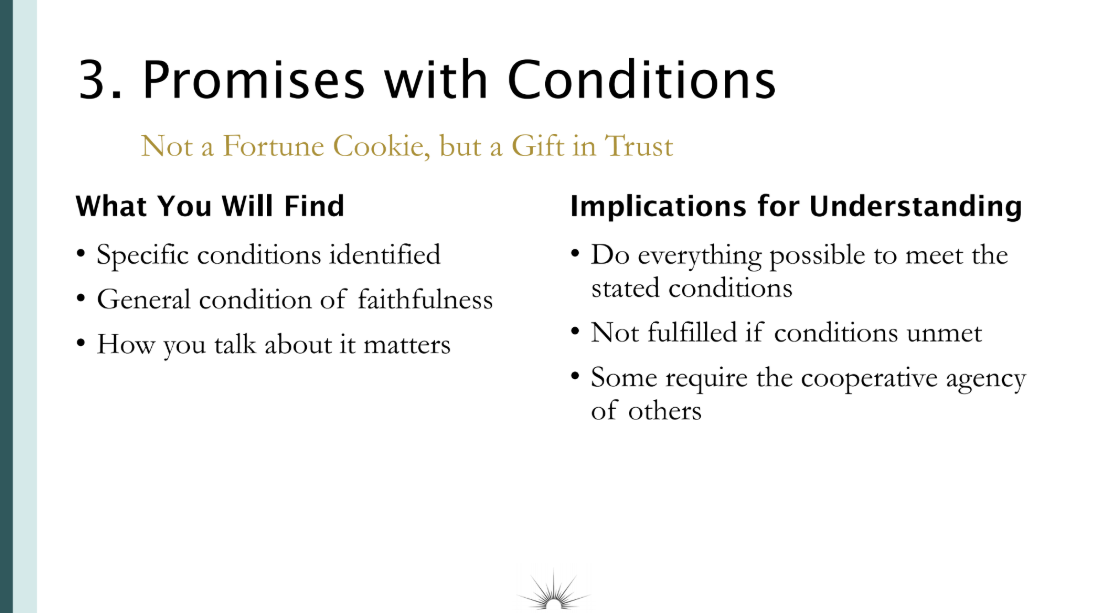

So, a patriarchal blessing is less like a fortune cookie and more like a gift given in trust. A good scripture story about this is the parable of the talents. When the Lord, or the master, gives gifts to His servants, there was no reason for them to have those things. He simply shows up with the gift and gives it to them with the trust that they will work on it in the future and make something out of it. If you think about your patriarchal blessing in this way, you’ll start watching for times when specific conditions may be identified for you. It may say, “If you do such and such,” or “If you are such and such, then something will happen.” If you get an “if-then” sentence construction, that’s a good one. Other times, it may be more general. At the beginning or end of your blessing, it may say something like, “All of these promises are given to you on the condition of your faithfulness.”

So, these promises are about our relationship with God, and God is trusting us. He is counting on us to do the things that will meet the conditions so we can get to the place where He wants us to go.

How We Talk About our Blessings

One of the important conditions surrounding patriarchal blessings is that how we talk about them really matters. They are sacred things, not to be trifled with.

One of the experiences I had in the Church History Library was when, before we had the online system, we would send out copies of blessings to people by mail. There was a general feeling from the Church leaders we worked with that they wanted people to understand how to talk about their blessings. I should note that the responsibility for patriarchal blessings belongs to the President of the Quorum of the Twelve, and he is the one who makes decisions and guides the process. As employees in Church History, we were responding to that guidance and doing everything we could to preserve the blessings, the best way we knew how. The instruction came that we should help people learn how to talk about their blessings.

In practice, this meant that the paper blessings sent out by mail included a letter from me—it was a form letter, not written individually for everyone. The letter had a paragraph that said, “Don’t post this on social media.” We have to remind people that this is sacred. Don’t post it online; it’s for you. How you talk about it matters. To this day, people still find me and say, “Oh, you’re the guy who sent me that letter and told me not to put my blessing on social media.” I ask them, “Did you follow it?” and they say, “Yes, I did.”

Meeting the Conditions to Receive the Blessings

So, there are some implications here when we think about blessings as having conditions that we need to meet. One is that we should do everything possible to meet those conditions. But an interesting thing about conditions in the gospel is that many of them are shared with other people. This flies in the face of a major tenet of some strands of American culture right now: “I’m an individual. No one can tell me what to do. The government can’t tell me what to do. My neighbor can’t tell me what to do. I’m my own person; I’ll take care of everything myself.” It turns out that this is not how God thinks about us. He doesn’t think of us as radically individualized, like Adam alone in the wilderness. We’re part of a constellation of other people, and they are part of the fulfillment of our blessing.

Sometimes this is very clear, like in a promise about marriage in a person’s future. That implies there’s another person who will exercise their agency and meet their conditions to enter a shared covenant with you. It also applies to things we don’t often think about. For example, if your blessing says something about being a good missionary, you’re going to have a companion with you for 24 hours a day for two years. That person will have to contribute by getting out of bed, teaching with you, and building a relationship with you. That companion becomes part of fulfilling the conditions, and your relationship with them becomes part of that fulfillment.

Another implication is that if we don’t meet the conditions, the promises won’t be given. This is the private part. The patriarch can’t answer it, your bishop can’t answer it—this is between you and the Lord. You know what the conditions are, and if you’re not meeting them, then you should. That’s what we should work toward.

Sometimes people ask, “What if there was a time in my life when I didn’t meet the conditions, and now I’ve got things back together—am I too late?” We’ll get to that in a second, in the timing part of it. But of course, God gave you the promise, and He didn’t undo the promise. So yes, go back through the doorway, commune with the Lord, and counsel with Him about the ways it will come together for you.

Okay, we’ve hinted at this next principle as we approach blessings.

Principle 4: A Time Appointed

Blessings have a time appointed for things to happen, and this is the Lord’s time. We saw in that revelation that He does things in His own time and in His own way. One of the things we have to figure out is what time is and how time works.

A young man named Heber Grant received a patriarchal blessing in his teenage years that told him he would be called to the ministry in his youth. Heber grew up in the Utah Territory in the latter part of the 19th century, and this was not the time when you sent in an application and said, “I’m ready, call me.” This was the time when you showed up at General Conference, and you would hear your name called to serve somewhere. Heber had this promise in his blessing, and he thought, “Great, I’ll be watching for this.” He knew about other young men like Joseph F. Smith, who had been sent on a mission when he was 15, as there were no standardized ages back then. So, he was excited.

Heber went to General Conference when he was 15, then 17, 18, and still did not receive a call. People around him—his friends, his peers—received calls, but he kept going, at age 21, 23, and 24, and still his name was not called from the pulpit to serve a mission. He went back to the text of his blessing and began to feel frustrated. He read it and thought, “What is going on here? It says I’ll be called to the ministry in my youth, and it hasn’t happened.”

As often happens, he entered a thought process where he began wondering about his blessing. He thought, “Maybe this is a mistake. Maybe the rest of the blessing is okay, but the patriarch just made a mistake on this one.” He rationalized that it was okay for a mistake to happen every now and then. But then he started to wonder, “Well, if this is a mistake, how do I know that the rest of it isn’t a mistake? What if every patriarch in the Church is just out there making stuff up, and none of this is inspired? What if the President of the Church isn’t inspired?” His thoughts spiraled in these directions as he wrestled with this unfulfilled promise.

One day, while walking down the street in Salt Lake City, carrying this burden of wondering about his blessing, about Church leaders, about the Church, and about the truth of everything he had ever thought about, he was deep in thought. He stopped and suddenly shouted out loud, “Mr. Devil, shut up!”

Now, there are people in Salt Lake City who yell things on the streets today, and we wonder about them. I probably would have wondered about Heber that day, stopping out of the blue and yelling. But he thought to himself and said aloud, “Mr. Devil, shut up! I don’t care if my patriarch made a mistake. I don’t care if every patriarch made a mistake. I know that this is the Lord’s work. I have personal experience with the Lord, and I will do what the Lord wants me to do.”

Shortly after that, Heber’s name was called over the pulpit—but it was not to be a missionary. As a 25-year-old single man, he was called to be the president of the Tooele Stake. Then, a year later, he was called into the Quorum of the Twelve.

He then went back and looked at his blessing and realized, “Oh, it hadn’t called me on a mission in my youth. It called me to the ministry, and this is the ministry that God has for me.” That was the realization he came to.

A lot of times, when we’re thinking about the timing of our blessings, we are using the cultural clocks around us. Heber was comparing himself to other people in his culture. “Well, there are young men who get called on missions; that’s the thing that’s supposed to happen to me. In my culture, people get married at this age. In my culture, this happens at this time.” That was his benchmark—what was happening to the people around him. His benchmark wasn’t, “What’s the Lord’s time? What is the time the Lord has appointed for this promise to be fulfilled?”

One interesting thing that happens is that, often, time is the most visible thing we wrestle with in our blessing because we think, “It’s too late; it’s passed.” But Heber’s experience reminds us that sometimes time is just the thing that gets our attention and reveals that we don’t understand things the way God understands them. This wasn’t a timing issue; it was an understanding issue. But timing caused him stress, and he later realized that he had been understanding it wrong. Time was just what he saw on the surface.

It’s Not a Timeline

Don’t think about your patriarchal blessing as a timeline. It’s not spelled out there. President Monson said to think of it more like a center line in the middle of the road. If you’re driving out in the backcountry where it’s really dark with no streetlights, there’s a line up the center of the road. If you stay close to that, even though you may not be able to see the edge, you know you’ll make it. So, your blessing is less of a timeline and more of a center line. You won’t find promises in there tied to culturally specific dates; instead, you’ll find broad outlines that give you guidance and direction as you begin to understand the Lord’s time.

There are some implications for this, and this one is really hard. When we see a gap in our blessing and the timeline doesn’t add up for us, we think something’s missing. We have to resist the urge to fill in the gap. Humans, for whatever reason, hate gaps, holes, and vacuums. We want to fill them in with something. But if it’s not the will of the Lord in His appointed time, we’re filling it in with our own assumptions, culture, or thoughts. We’ve got to train ourselves not to fill in those gaps and say, “You know what? I don’t know what that means. There’s a gap here, and I’m okay with it.”

One funny thing we do in our culture is that every month we have a meeting with an open microphone, and anybody can get up and say, “Here are the things I know.” In that hour, you hear the phrase “I know” dozens of times. Over time, we start thinking, “Oh, the only valid experiences of a disciple of Jesus Christ are to know stuff. The only people who get up are the ones who say they know things.” But if you actually read the scriptures, they are filled with stories of people who don’t know things.

Adam, why are you making that sacrifice? “I don’t know. I’m supposed to.”

Nephi, what does this thing mean in your vision? “I don’t know the meaning of all things, but I know God loves His children,” is Nephi’s answer.

So, one of the things we can learn is not to fill in these gaps but to be fine saying, “I don’t know. It’s okay that I don’t know, and I will understand this at the time that is appointed.”

Another thing to think about here—another implication—is that the Lord’s time teaches us to wait differently. In our current 21st-century, information-age culture, we hate waiting. If I’m trying to watch a video online and there’s a 12-second ad, I’m so mad. “Why do I have to wait 12 seconds? I’m trying to see this thing I clicked on!” If I get to the grocery store and all the lines are long, I go to self-checkout because it’ll be faster, and there are 10 people there, I’m so frustrated. “Why do I have to just wait and stand here?”

The scriptures talk about waiting. They use that word, but they use it in a different meaning. We still have this meaning in English, but we don’t think about it as often. The meaning survives in the people who serve you at a restaurant, who are now often called servers but used to be called waiters. If you’ve ever had a job in the food industry, you know that you do not sit around with nothing to do. You’re on your feet, running, attending to people’s needs.

My mother and my wife’s mother are both like this. When we go visit them, they don’t sit in a recliner and say, “Hey, welcome!” They come up, greet us, help with our coats, hug the children—they’re everywhere, waiting on us, attending to us, and helping us. One of the reactions when the timeline isn’t working is to learn how to wait upon the Lord in a way that means you’re full of motion. You’re doing the things God wants you to do. You’re keeping the conditions and preparing yourself for when the appointed time arrives.

One of the things God does with timing is give us the chance to prepare, and we have to be prepared for the moment when he is ready for us.

Principle 5: Peace without Clarity

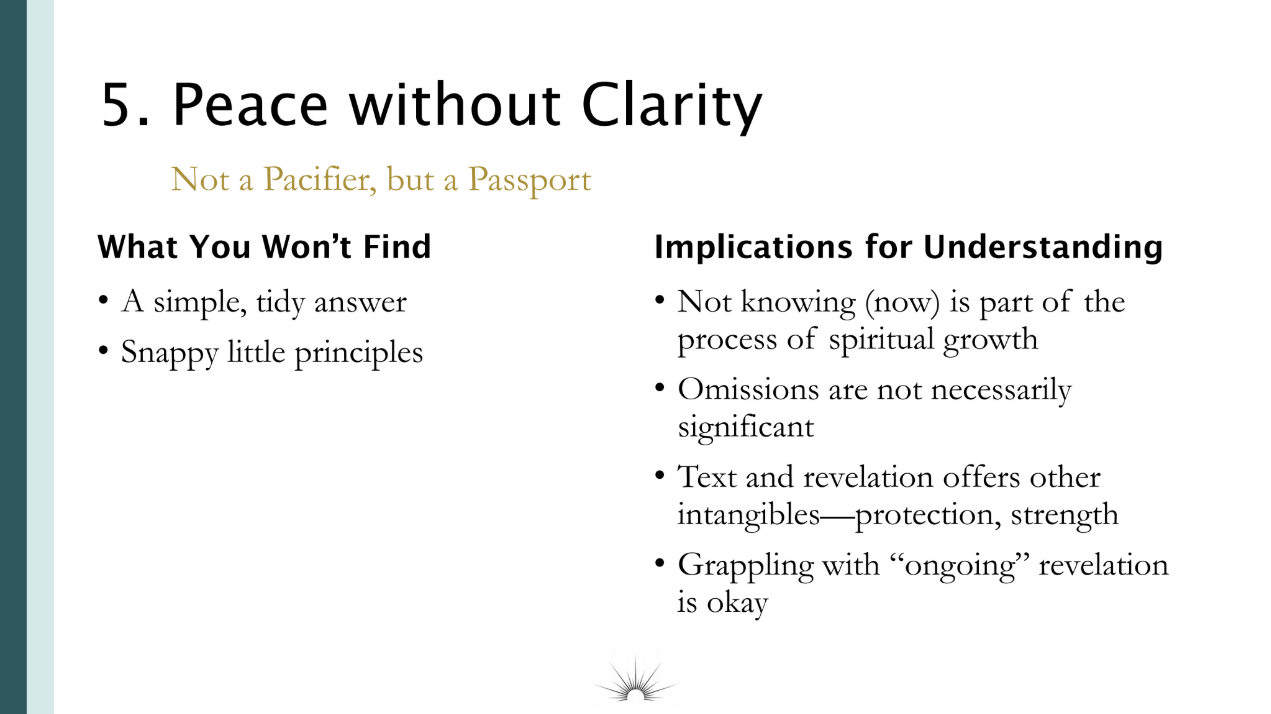

The last idea I want to share here is that approaching your patriarchal blessing requires us to seek for peace without clarity. Often, we think about peace meaning, “If we’re wrestling with something, or struggling with something, we’ll think, ‘Oh, if I can just get clarity on this, then I’ll have peace.'” And so, we link them together—we connect them. Clarity equals peace, and as soon as I find clarity, I will have peace.

Well, when Jesus talks about peace, the first thing He says, or one of the things He says, is, “My peace isn’t like the world’s peace.” It’s not an end of war; it’s not something that makes sense. It’s not the end of famine; it’s not people giving up their guns. It’s peace that doesn’t make sense.

Paul says it even clearer in his letter to the Philippians. He says the Lord offers “peace that surpasseth understanding,” meaning peace and understanding are separate. If you’re running a race, peace is way out here in front—it’s past your understanding, it’s surpassed it, it’s beyond your understanding. Understanding will catch up, but one of the things we need to accept is peace that doesn’t make sense.

So, I want to share a story here about a woman named Lydia Knight. She joined the Church in the 1830s and was one of the first in the late 1830s to receive a patriarchal blessing. One of the promises in her blessing was that her heart should not be pained because of the loss of her children.

Now, in the 1830s, this was a huge promise for women. The most common way that women died in the 19th-century United States was in childbirth. Infant mortality was extremely high, and the act of giving birth was an act of courage where your life was on the line. It still is today, though we don’t think about it much. For Lydia, the idea that all of her children would survive gave her great hope at a time when medical practices and the experiences of people around her showed that everybody loses a child—sometimes five or eight. You know this from your own genealogy; it was a common experience. Lydia had this promise.

Then, her infant son—childbirth had worked out okay—her young toddler James fell gravely ill for a long time, with no change or hope in sight. Over time, people around Lydia started preparing her for James’s death. Her own husband said, “You can’t just cling to him. This happens, it’s okay. We know that James is not going to damnation; the sacrifice of Jesus Christ covers James. Let him go, begin to have peace. You shouldn’t be clinging like this—it’s irrational, Lydia. You’ve got to prepare yourself for the obvious fact that James is going to pass away. It happens, that’s just how life works.”

He said to her (in Lydia’s words), “You cannot keep that child. Why do you cling to him? You will displease our Father in Heaven. Let him go, give him up, and his sufferings will be at an end.”

Lydia’s husband was saying that by continuing to pray and exercise her faith, she was the one keeping James here and prolonging his suffering. But Lydia wouldn’t let go. She knew the promise. It didn’t make sense to her; it didn’t match what she saw in her son. One day, she reported that little James lay like a breathing skeleton, with skin drawn tight, his eyes glassy, and his breathing all but stopped. Her husband came in and said, “It’s time to pray for strength. He’s gone. He’s barely even breathing. You need to pray for strength to bear this loss.”

That afternoon, Joseph Smith was walking down the street past their home, and Lydia called out to him. She told him about her blessing, showed him James, and shared her faith in the promise. Joseph said, “Sister Lydia, I do not think you will have to give him up. Call for the elders, bring them in, and give him a blessing.”

They had done this before, but she called for them again. And here’s James—he lived to be 71 years old. He crossed the plains and came to the territory. Lydia held on as tight as she possibly could to that promise, even when it didn’t make sense, even when it didn’t bring peace, and when everyone around her was saying, “It’s time to let go.” She held on, knowing that this was the relationship she had with the Lord.

So, when we think about peace without clarity, sometimes this means that we don’t find a simple, tidy answer in our blessing. We don’t get these snappy little slogans that we mistake for principles. Instead, we get difficult things that we have to hold on to, things we don’t know or understand. We get to learn that not knowing everything right now—not having all the clarity we desire—is part of the process of our spiritual growth.

We learn that omissions aren’t important. Sometimes people will read a blessing and say, “Oh no, this thing isn’t here!” But everything doesn’t have to be there. It’s not supposed to give you a clear explanation of everything that will happen. The text and the revelation surrounding it, the ongoing revelation, offers us other things that are less tangible: strength, hope, protection.

We’re in the Middle of Our Story

Now, I have to confess that the people whose stories I’ve shared with you today—and there are 10 times as many in the book—have one really significant advantage over the rest of us. They are all telling these stories while looking back on their experiences. One of the things that happens in life is that we have to live going forward, but we make sense of things looking backward. All of these stories have an ending, but this part about peace without clarity brings us to a really important point: you and I, we’re not at the end of our story yet. We’re not yet looking back, where everything makes sense. We’re in the middle, and in the middle, things aren’t clear—they haven’t been resolved, and the timing hasn’t been revealed to us.

So, one of the things our patriarchal blessing teaches us, and supports us in, is the really important idea that grappling, wrestling, and seeking is okay. Another strange thing we have going on in Latter-day Saint culture right now is the idea that asking questions is somehow bad. We don’t usually say this—nobody stands up at the pulpit and says, “Don’t ask questions”—but it’s more something you feel in Sunday School, like, “I probably can’t ask that here.” There are things we wonder about, and that can lead to a line of reasoning like this: “If I have a question, then maybe I have a doubt. If I have a doubt, then maybe I don’t have faith. If I don’t have faith, then maybe I don’t have a testimony. Why am I even here?” And culturally, we put all of that burden on the natural act of seeking, asking, and questioning.

I don’t know of any instruction or commandment that the Savior repeated more often than some version of “ask, seek, knock, come unto me, draw near unto me.” The Savior is begging us to come to Him with questions, with curiosities, with things we want to know. Our patriarchal blessing is a physical manifestation of that invitation—personally for us to draw near to the Lord—because He wants us to be people who seek, ask, and knock, and then people who pass through the doorway. Not the destination, but the doorway into revelation, guidance, and the interpretation that can come from the Lord.

Conclusion

I want to share a comment from Thomas S. Monson. He said, “Your blessing is not to be folded neatly and tucked away. It’s not to be framed or published. Rather, it is to be read, it is to be loved, it is to be followed.”

That has been my hope in preparing the book and in sharing some thoughts with you today. I hope that they’re helpful as you read, love, follow, wrestle, seek, and wonder. And then I hope and pray that you will encounter the mercy, kindness, and blessings of the Lord that will bring you peace without clarity, but also illumination, as you move forward on the path that He knows is your path. That is my prayer and hope for you. Thank you very much for being here today.

Q&A

Scott Gordon: We actually have two questions.

Keith: Great, let’s do it.

Scott: Does the Church translate blessings in other languages to English for the archives?

Keith: No. Blessings are given in the language that the patriarch speaks, which is not always the language that the recipient speaks. There are times where there’s not a patriarch ordained in someone’s native language, but we archive the blessings in the language the patriarch gave them. So, the system—here’s the geeky part of it—the system has to support all the different kinds of symbols that go with different languages. It made it complex and fun and gave people headaches, but yeah, they’re archived in the language of the patriarch.

Scott: This question came in very early, and I think you addressed it in your talk, but just to give you a chance to reiterate your thoughts: How can I trust my blessing or the concept of blessings in general?

Keith: I love this question because it’s about trust, and I think it’s really important. Sometimes we think about something in our blessing that we’re wrestling with, or it could be a question about Church history or something else we’re struggling with. We think of it as an information issue: “I’m trying to get information about what I should do in life.” But information doesn’t just float around by itself. We tell ourselves that this is the information age, but for humans, information is always attached to emotions and feelings. One really important feeling is trust.

Trust is not necessarily tied to information. I can’t give you ten facts that will make you have trust. Trust comes from experiences, from interactions. I’m inspired by a passage in 2 Nephi 4, which we often call the “Psalm of Nephi.” It’s a time when Nephi is a little bit guarded. He doesn’t tell us everything he’s struggling with, but we can piece it together: his father has died, the civilization is having issues, and there’s divisiveness. Nephi goes into this extended passage where he’s clearly worried, overburdened, and wrestling with things. But at the end of chapter 4, Nephi comes back to experience. He doesn’t say, “Oh yeah, I just remembered this fact that I forgot, and all my problems went away.” He says, “I know in whom I have trusted.” That’s a past experience: “I trusted Him before, I had an experience, and it worked, so I’m going to trust in God now.” Trust is experience-based, not fact-based or information-based. They’re connected, but an important part of learning the will of God for you is having experiences with God and reflecting on those experiences.

President Hinckley did something at General Conference once that fascinated me. He apologized for it—whenever he said something personal, he would apologize. He began with an apology but said, “I want to share with you a history of my testimony.” That’s a really interesting way to think about it. We often think testimonies are just, “Here are the facts I know.” But his testimony was a story, and he told about being a young child, growing up, and serving a mission—his life. That’s where trust comes from. It’s not from one more scripture, one more podcast, or one more fact. Trust comes from experience with God.

Scott: You know, I really appreciate that. It’s interesting because I just got an email the day before yesterday that I have to respond to from someone who’s thinking of leaving the Church, and it’s based on a YouTube video. Because of the conference, I haven’t had a chance to respond yet, but the YouTube video is essentially trying to undermine trust in the Brethren. That’s all it does, and it’s filled with half-truths and things like that. But I think the mistake would be to go through and say, “This is wrong, this is wrong, this is wrong.” Instead, I think it’s more important to deal with the trust issue.

Keith: Yeah, exactly. Good luck with that email.

Scott: Thanks, and thank you very much for your time—I really appreciate it.

Keith: Thank you.

TOPICS

Patriarchal Blessings

Questions

Waiting for Answers