Summary

John Welch discusses the seven seals from the Book of Revelation, through the context of ancient sealed military diploma plates that granted eventual Roman citizenship to long-serving soldiers. He examines the method, purpose, and deferred promises of these plates and compares them to the judgment, tribulation, and final triumph of good over evil that faithful saints will eventually experience.

Introduction

Scott Gordon: I am very pleased to introduce our next speaker, Jack Welch, who has recently returned from a mission. He is the Robert K. Thomas Professor Emeritus of Law at the BYU Law School and former editor-in-chief of BYU Studies. He practiced law in Los Angeles, founded the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, and has been involved in founding Book of Mormon Central. Jack has made a significant impact on Latter-day Saint scholarship. With that, let’s introduce Jack Welch.

Presentation

John Welch: I am so grateful for this FAIR conference, its many volunteers, attendees, technicians, and the outstanding presentations—many of which offer strong preludes to my own presentation about understanding the New Testament Book of Revelation better. This is a book I love and know to be true and relevant to our day.

As George Mitton has discussed here, the scriptures dramatically portray for us the contrast between the forces of good and evil, and certainly the Book of Revelation does that. As Neil Rappleye has shown, heavenly spiritual visions, even those seen with spiritual eyes, are substantively real. What John the Revelator saw was not just an apparition. And as Michael Brent Collings has shown us, horror is a necessary part of God’s plan, just as fear, suspense, horrors, symbolism, and hope are necessary parts of the Book of Revelation.

The Basic Argument

My argument today is that seeing the Book of Revelation in light of a particular, pervasive, official Roman practice may unlock the contrast between the horrific ways of the Roman world and the glorious rewards of the New Jerusalem, promised to God’s soldiers enlisted here in the conflict with sin and evil.

My comments on the Revelation of John build upon my article in the well-deserved Festschrift for Dan Peterson. I begin with personal words of appreciation for Dan’s remarkable ability to draw important connections spanning eras and bridging dispensations. One of the many things Dan does so well is to understand the significance of crucial ideas in some overlooked cultural context, whether Jewish, Canaanite, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, or Christian. In his honor, I approach the Book of Revelation through some overlooked aspects of one part of its first-century Roman context. I hope this brings a classic “Dan Peterson aha” smile of interpretive success.

“One of the Plainest Books?”

Although Joseph Smith, in 1843, called the Book of Revelation “one of the plainest books God ever caused to be written,” that book remains notoriously difficult to understand. As one great help in this regard, I recommend the BYU New Testament Commentary volume on the Book of Revelation by Richard Draper and Michael Rhodes. And today, I wish to add a new interpretive key: numerous points of parallel between the issuance of Roman military diplomas—brass plates sealed with seven seals—and the shaping of John’s apocalypse, which contrasts everything celestial about the everlasting kingdom of the New Jerusalem with everything terrestrial about the world of Rome, as seen through the lens of these Roman metal plates.

Research Background

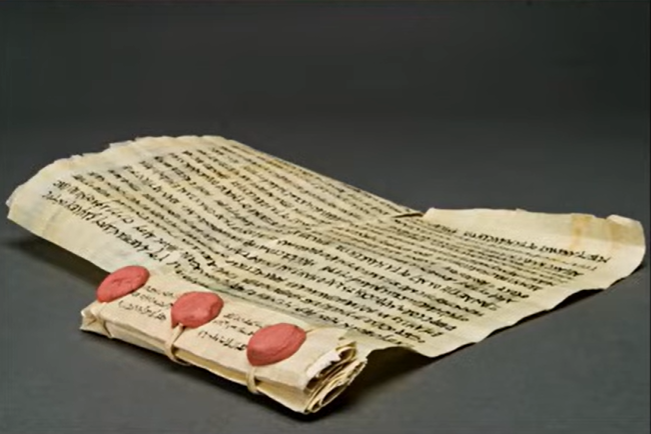

By way of research background, my interest in this subject began 30 years ago when I was a law professor teaching a course on biblical law. I became intrigued with a text in Jeremiah 32, which tells of a land transaction between Jeremiah and one of his unbelieving nephews. Jeremiah gives us a detailed description of that transaction, which was documented with what we would call a deed, as you can see here: open on the bottom, subscribed by witnesses, with a duplicate copy of the text of the deed sealed as a backup copy on the top in a bundle.

That bundled document was sealed by three witnesses, as required by Hebrew law, to be buried in a stone jar and preserved for many days.

This whole thing intrigued me, and for obvious reasons, I began asking people, “What kind of legal document is Jeremiah talking about here? And have any such deeds survived from antiquity?” Well, I checked the main commentaries on Jeremiah and discussed it with people, but I found no help.

So, on my way to a conference on ancient Near Eastern law at the Papyrological Institute in Leiden, I decided to stop first in Oxford and London, at the Bodleian Library and the British Museum. To my surprise and disappointment, I found no help in either of those places. So, I traveled on to Holland.

At the conference in Leiden, I sat in the same chair all three days in the library conference room at the Papyrological Institute. On the third and final day of the conference, as some of the papers got a little boring, my eyes wandered to the shelf of books behind my seat. There, I found dozens of books, articles, and technical papers on double-sealed, witnessed documents, called in German “Doppelte Urkunden” (double documents). That treasure trove came as an answer to my prayers and questions and has proven to be of interest to those studying biblical law, the Book of Mormon, and, as we will see today, anyone interested in the Book of Revelation.

Having access to that shelf of resources allowed me to write a long chapter in the Festschrift for John Sorenson, published in 1998, which analyzed a wide spectrum of double-sealed witness documents from the ancient world, especially that transaction in Lehi’s time mentioned in Jeremiah 32.

Ancient Double-Sealed Plates

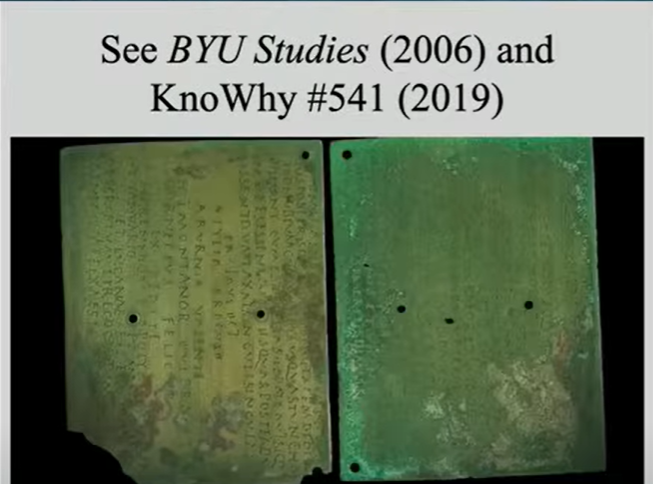

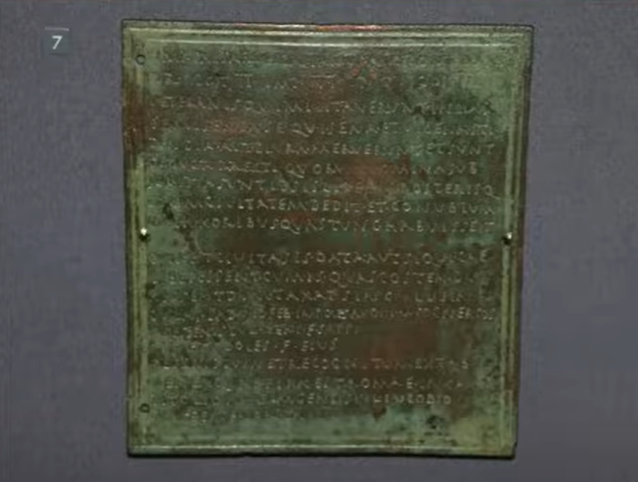

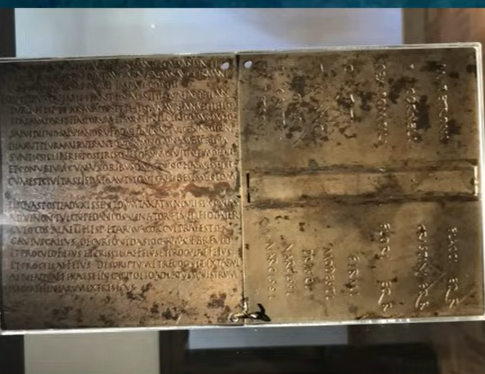

That heavily illustrated chapter attracted the attention of an antiquities dealer in Los Angeles named David Swingler, who put me in touch with an auction house in London. That auction house just happened to be selling an original set of two ancient double-sealed Roman brass plates, pictured here. Within 24 hours, four donors had joined me, and together we were able to acquire and donate this rare complete set of brass plates to BYU.

Such documents are called “diplomata,” literally “diplomas,” each consisting of two plates originally sealed together, with the wording of the retirement award written on the outside of the first plate and a duplicate copy written on the interfaces of the two plates. This particular pair of double-sealed Roman brass plates was issued by the Roman Emperor Trajan in the year 109, as discussed in BYU Studies in 2006. The year 109 was not long after John wrote the Book of Revelation.

This photograph shows the interior sides of the two plates, dating them to the day before the Ides of October. When I first explained this to one of the potential donors, he asked, “What’s the Ides of October?” When I told him it was October 14th, he immediately blurted out, “That’s my birthday! Count me in!”

And then, just four years ago, in December 2019, Book of Mormon Central released its KnoWhy #541, crafted by Neil Rappleye and our KnoWhy team, whom I very happily acknowledge here. That KnoWhy asks the question, “Why was the heavenly book in Revelation 5:1 sealed with seven seals?” That’s the question I want to experimentally push even further today. To see how this whole Roman military retirement practice can help us unpack the core message of John’s Book of Revelation. So, how did this Roman practice work?

In general, these double-sealed metal plates granted Roman citizenship after 25 years of military service. Not every soldier, of course, survived 25 years, and the work they performed was strenuous. The recipient of such a document kept his diploma much like we keep our passports today, as evidence of citizenship, with all its valuable rights and privileges.

Roman citizenship could also be purchased, but at great cost, and not many people could afford that. One famous example comes from the story of Claudius Lysias speaking to Paul in Acts 22, where he explains that he bought his citizenship with a large sum of money. In contrast, Paul was born a Roman citizen, as his father had Roman citizenship, making Paul a rare exception in his day. For most people, the best way to earn Roman citizenship was by serving 25 years in the Roman army.

The word “diploma” or “diplomata,” along with similar terms, became technical words for official legal documents in general. For example, when the Centurion sent an official report explaining to Governor Felix the legal charges against Paul, that legal record was also a double-sealed document, as mentioned in Acts 23.

Several of you might have seen the exhibit we’ve had here at the conference about such Roman plates. Many of the pictures I’ll show during this presentation come from that display or similar exhibits.

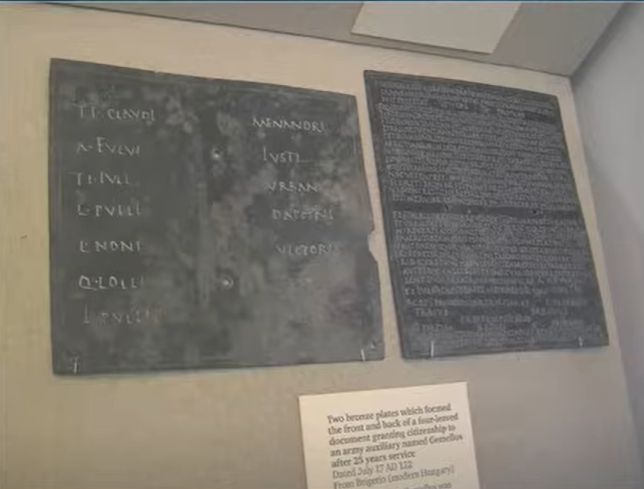

These diplomas were, and still are, highly valued. Here’s one pair from 122 AD on prominent display at the British Museum in London.

Another set is proudly displayed in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

In my travels, I have stumbled upon examples in places like Austria and Romania, though they are not easy to find.

For instance, here’s the front plate of one pair at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Up close, that plate says it was awarded to a retiring soldier who had fought in what is now Hungary.

Here’s another set from the National Museum of History in Bucharest, Romania, from the area where the Roman province of Dacia once was, where the BYU Roman plates were also discovered.

The “Biblos” in the Book of Revelation

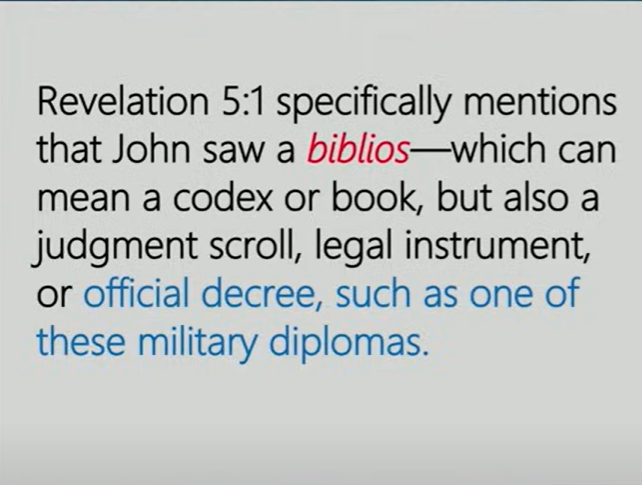

So, what do these Roman plates have to do with the Book of Revelation? As you may recall, John’s vision begins in chapter 4 with a magnificent scene: the Throne of God, surrounded by four beasts and 24 elders. In Revelation 5, John is shown what is called a “book” in the King James Version, but it’s not what we would normally think of as a book. What John saw was small and thin, held in one hand by the one seated upon the throne. Chapter 5 is pivotal to the entire Book of Revelation, so understanding Revelation 5:1 is crucial to grasping the main messages and subtexts of this vision.

Revelation 5:1 says this sealed document was held by the one seated on the throne, and it’s called a “biblos,” which in Greek can mean several things, including a codex or book. However, ancient codices were usually bulky, so this might not be the best interpretation of the word here. For our purposes today, it’s significant that “biblos” can also refer to a judgment scroll, a legal instrument, or an official decree, including military diplomas.

Most significantly, John describes this book as being written on the front, within, and on the back, sealed with seven seals. We will examine the Greek text of this verse later, but this description is an exact match for a Roman diploma.

The Number Seven

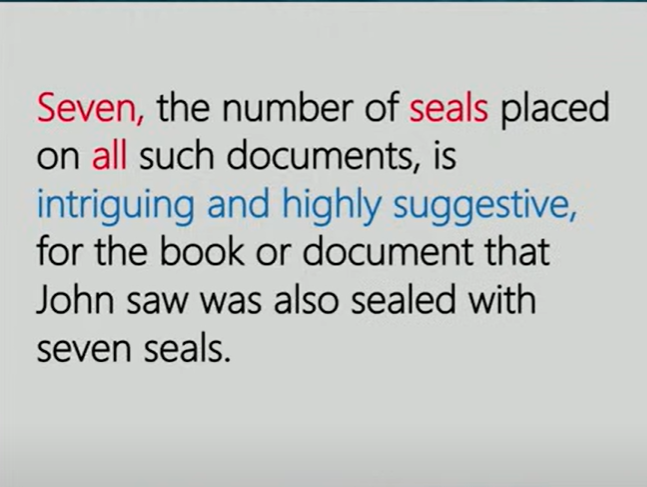

Now, let’s talk about the number seven. These plates were all sealed with seven seals—the number used on all Roman metal diplomas. To have a document sealed with seven seals is otherwise unheard of in the ancient world of legal documentation. Many ancient documents required two or three witnesses, but never seven—except in this case. Seven high-ranking witnesses were required to certify, with their personal seals, the content and worthiness of these numerous military diplomas, which only an imperial judge could open them. It’s possible that John the Revelator recognized the powerful symbolism of this imperial convention when he saw this book with seven seals, which Jesus Christ would open at the time of God’s judgment.

The Book of Revelation frequently uses the number seven—55 times, to be precise. John mentions seven churches, candlesticks, stars, horns, eyes, thunders. Seven heads, crowns, angels, seven spirits, trumpets, vials, seven mountains, kings, and so forth. However, the seven seals may be the most fundamentally and culturally significant of all these various uses of the number seven and all its symbolism.

Seven may convey a sense of many positive things such as in the sabbatical renewal or divine abundance. Seven can also be the number of completeness, such as in complete punishment or the full reward, or purification and penitence. It can also be associated with Satan attempts to mimic God as George Mitten has mentioned earlier in this conference. For instance, Revelation 13 describes the infernal beast with seven heads.

In Revelation 5:5, we read, “Weep not: behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, hath prevailed to open the book and loose the seven seals thereof.” The implication is that He will do this completely, perfectly, and authoritatively.

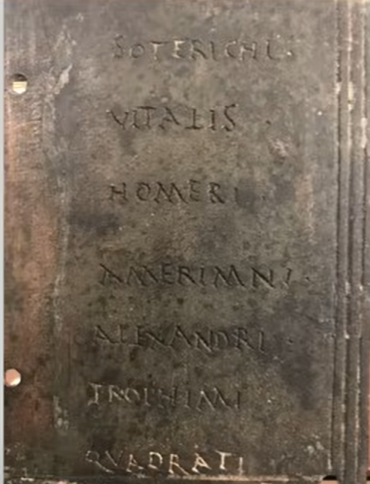

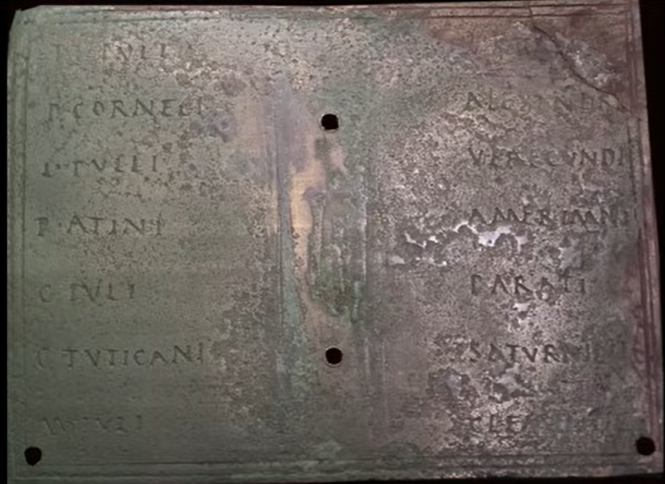

Here on this slide, you can see the names of the seven authoritative Roman witnesses listed on the back of one such plate.

Here you see the full exterior, or backside of the second of the BYU plates, listing the names of the seven officials who approved that particular diploma. Every Roman had three names. The first name of each witness is here on the left of the middle section of this plate, and the second name, or principal family name. The third name or cognomen (or nickname), often identifying a branch of a family, was then placed on the right side with the seal box originally in between the two sets of names. It was fixed using the two holes in the middle with a wire, and their seals placed in between. Each official was required to give their full name to certify the document. Names are also important in the Book of Revelation as well.

Here is one such signet ring to seal something. As sealing in our temples does not merely mean closing an envelope shut or to close a deal, so also in these ancient cases, to seal meant to stamp a document with an authoritative personal seal, somewhat like applying a personal signature.

How the Roman Sealing Process Worked

How this sealing process worked for these Roman military diplomas is very interesting. On the front side of the first plate was the full text of the retirement reward, and on the backside of the second plate was a seal case, which is between where those Roman officials’ names stood, as we’ve seen in the previous example..

The seal case held wax, which was poured over the wire when it was warm, and as it cooled, the personal seals of each of the officials was placed between their first and second and third names, in the middle of their signature. It was then covered with a tightly sealed piece of wood to protect the seals. And, as you can see on the bottom here, you have two rings in the corners of the two plates, so that after the sealing wire had been opened, the plates could be opened like a little book. And with this, the official who had the authority to open the seals could compare the text on the front plate with that of the interior text, which you might say is the backup copy or the recorded copy.

Why would they do this? Well, if the text had become damaged, they wanted to be sure that they could get access to the official document the way it had been awarded and before any damage might have taken place.

The History of the Sealed Documents

The use of these doubled sealed witness documents for military retirements actually begins around 54 AD, during the reign of Emperor Claudius, the same time Paul introduced the Gospel to the Roman province of Asia where the Seven Cities that John will then address at the beginning of the Book of Revelation are found. But by the time of the writing of John’s Revelation, the practice had become widespread, with awards being granted to soldiers from as far north as England and as far east as Jerusalem.

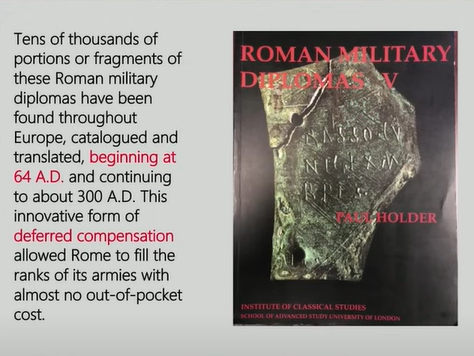

Tens of thousands of fragments of these plates have been found throughout Europe and they’ve been cataloged and translated in publications such as this one.

This practice continued until about 300 AD. Offering and then granting these significant retirement benefits to soldiers was an innovative and highly desired form of deferred compensation that allowed Rome to fill its ranks of armies with almost no out-of-pocket costs.

In a similar way our promised blessings in heaven are also given in a form of deferred compensation. Some payments and benefits, of course, are felt here, but just as the Roman soldiers waited to get their final benefits at their retirement , we will receive the greatest rewards also, in the world to come.

Speaking of the widespread nature and well-known practice of these plates, this map shows where intact plates (shown in black) and a few fewer than a dozen complete sets of both plates were found. Notice that most of the complete sets were found in the area around Romania and Bulgaria, where the BYU plates were discovered.

And here’s another one of those complete sets. I ran across this in Croatia, in a museum in a city on the Danube River. It was, in Roman times, a frontier outpost, and this particular plate is dated to 64 AD. It’s the earliest surviving diploma in existence. This set, as you can see, is very beautifully inscribed, cast, and elegantly crafted. Unlike others that come along later, as time goes on, the process becomes a little more routine, and the plates are not quite as elaborate. Nevertheless, the form and use of the seven witnesses is continued exactly in this way, clear to the very end of their use.

Thus, I think we can conclude, as we look at this, that the allusion here in Revelation 5:1 to this distinctive Roman practice would have had a widely recognized, powerful impression, with many implications in the minds of all readers who saw that John was seeing a book. Whether they were Romans or Christians, it would have meant a lot to them in one way or another. Significantly, the audiences to whom the Book of Revelation was addressed can be identified not only by the seven churches in chapters 2 and 3, but, in contrast, by the reference to the seven mountains in Revelation 17:9, which is widely recognized as an allusion to the famous Seven Hills in the city of Rome, where these royal awards legally originated.

What the Military Retirement Granted vs What Faithful Christians are Granted

These military diplomas granted each retiring soldier very significant citizenship benefits. Citizenship bestowed a powerful status in Roman society, and it came with the rights to vote, to wear the toga, to hold public office, to be exempt from all taxes, to be protected against local lawsuits, and to have the right to appeal directly to the Roman Emperor for any action brought against that Roman citizen by any provincial authority. Receiving this status, a Roman soldier would have thought he had died and gone to heaven, which actually is the very point of John’s Revelation. You couldn’t think of any benefits greater than these, not in that world.

When faithful Christians die, they go to heaven; their reward will be of like kind, but even greater than the benefits afforded by Roman citizenship. Although citizenship per se is not mentioned in the Book of Revelation, the whole purpose of that book is to reassure all faithful Christians that they will, in the end, become residents and citizens in God’s holy heavenly city, the New Jerusalem. They would have the right to wear, not a toga, but sacred garments. They would have the right to appeal, not to the Roman Emperor, but to God the Father, with Jesus Christ as their advocate. And just as Roman citizens paid no taxes, by the same token, Jesus had said that God does not extract taxes from those who are the sons and daughters of God, as he says in Matthew chapter 17.

Notice also that these military diplomas contained a detailed report of the places where the retiring soldier had faithfully and loyally served. The Latin word for faith is fides, meaning faithfulness and loyalty. As in the Marine Corps motto Semper Fidelis, this word in John’s day meant more than just belief. Thus, John’s encouragement to the members of the seven churches in Asia did not just ask them to believe the gospel, but to live and serve as true, loyal followers and servants of Christ.

In addition, these military diplomas were all produced in Rome and were then issued and delivered from there. The reward was also posted in a public place designated in each particular diploma. These rights, therefore, were public knowledge; the provisions of these diplomas could be read by anyone—the citizen himself, his family members, local officials, or business people. Likewise, but in contrast, the Gospel of Jesus Christ is open to all people, and the opening verses in John’s Revelation declare it to be open and public in nature, stating that God had given this revelation in order to make known to his servants things which must shortly come to pass.

John continues, “Eternally blessed and exalted (makarios) are all who read and understand the words of this prophecy and keep, obey, and protect the things that are written in it.” The text of John’s Revelation was not intended to be concealed or held closely in the hands of just a few but was to be made known to all who would acknowledge, respect, and serve the Lord Jesus Christ.

Certification and Opening of Sealed Document

As mentioned previously, these diplomas are certified by seven high-ranking Imperial officials. An official delegation personally handed the recipient his pair of sealed bronze plates. Here we see yet another parallel to John’s Revelation, where seven angels step forward one at a time to break each of the seven seals and unleash the otherwise restrained judgments of God. It would likely not have been lost on contemporary readers of all kinds that these seven messengers of God had even greater powers than any of these seven Roman officials.

Normally, only a judge or high official could break open the seven seals on these diplomas, loosening and unwinding their sealing wire. By opening all seven seals, a judge could then officially read the interior seal and compare it, as we’ve said, with the correct open version—the open and closed versions could be compared to confirm authenticity. The Book of Revelation shares a common point here, helping us appreciate how The Book of Revelation ends with a stern warning that people should not tamper with its wording. This complex operation that the Romans went through was to ensure that their decrees were not tampered with.

The Book of Revelation ends: “If any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the Book of Life, and out of the holy city, and from the things that are written in this book.”

Besides echoing such curses—which were commonly placed on people in antiquity who tampered with important legal documents, either by adding to or taking away from them, as is found in Deuteronomy chapters 4 and 12—the diploma’s format made it easy for any tampering to be detected and swiftly punished.

The Book of Revelation also, I think, alludes to several ceremonial formalities used in awarding these military diplomas. We have accounts of these triumphal parades where banners, chariots, horsemen, and trumpets were used on such grand, martial occasions. In John’s Revelation, one can see the validation and awarding of heavenly citizenship with even greater heavenly pomp and circumstance, including a vanguard of seven angels with seven trumpets saluting a parade of seven lamps or torches ahead of the throne, instead of the Roman imperial dais, blessed by seven spirits of God, seven claps of thunder, and even an earthquake shaking the foundations of earthly kingdoms.

For John, an official squad of seven heralding messengers signals to everyone the conclusion of the official parade. You might wonder why all of these things are mentioned in the Book of Revelation. Of course, they’re there because they’re real; they’re things that are actually going to be represented, and so they have eternal value and value to us. But to the people in Roman times, they would have recognized all of these elements as inevitable allusions to any Roman military triumphal event, which actually pales in comparison.

Various Textual Readings of Revelation 5:1

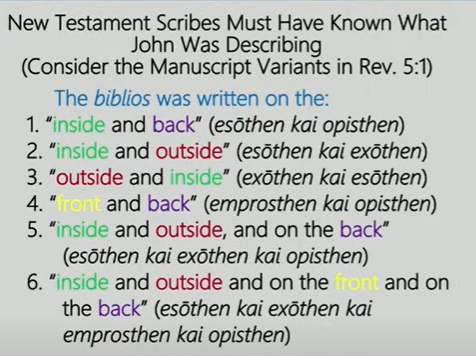

And now, as promised earlier, we are prepared to take a closer look at the key text in Revelation 5:1, in which John saw that biblos with seven seals. I think clinching my thesis concerning this reading of the Book of Revelation is the fact that there are various textual readings of this particular verse—six different readings, in particular, in the ancient Greek manuscripts.

But consider how this set of variants as a whole struggles to explain something that I’ve had a hard time explaining to you. You might imagine that the scribes had an impression that people weren’t all going to understand what was being described. So, one scribe wrote that the book was sealed on the “inside and the back”—that’s in the Alexandrian text, followed by the King James Version. Another scribe wrote that it was sealed on the “inside and outside”—that’s in the Leningrad 9th-century manuscript and others, with Origen and the Vulgate commonly following that reading.

Third, one scribe said it was written on the “outside and the inside.” Another scribe said it was written on the “front and on the back”—that’s in Codex Sinaiticus, a 4th-century Coptic text, and Origen uses that expression twice. Fifth, one scribe said it was written on the “inside and outside and on the back.” Now that’s getting quite precise: inside, outside, and back.

And finally, we have one scribe—rather late—who says, “Well, I’m going to explain it all so there will be no confusion.” This text reads, “It was written on the inside, the outside, the front, and the back,” so we have all of these options covered.

But I think what’s going on here, and why these scribes would describe it this way, is that we have a set of variants written by people who knew these procedures. As scribes, professionally, they would have known of these various forms of sealing legal documents, and they would have assumed that their readers were somewhat familiar with it as well. What they’re trying to do is depict this complex process completely.

So, scribal analysts or textual critics might ask, “Well, which of these six different descriptions is the right one?” My answer would be that they all are. The documentary pattern that stands behind this group of variant readings is the full pattern that we’ve seen followed in producing these Roman doubled-sealed military diplomas, written on the front and back, the inside and outside, and, as we have said, sealed then by seven seals. As far as I know, no one has suggested this reading before, as we have here in Provo, so we’ll hope it is seen as one of those aha moments that provides an understanding of many things that come up in the full unfolding and opening of the Book of Revelation.

John’s Use of the Seven Seals Imagery

In conclusion, let’s consider two final questions. First, when and where would John the Apostle have possibly learned all of this? He may have learned it anywhere in the Roman Empire, as these kinds of things were being done. But where would he have learned so much about Rome and how Rome, in general, behaves? And where would he have been so impelled to discount the supposed glories of Rome in favor of the eternal glories of God’s city?

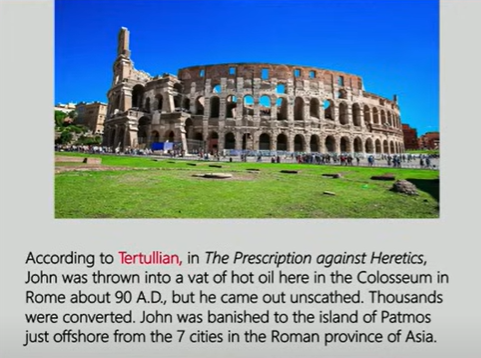

Well, in the late 80s, according to early Christian tradition, John was in Rome, and the persecutions against Christians were occurring at that time during the reign of the Roman Emperor Domitian. According to Tertullian, in the middle of the 2nd century, in his work called The Prescription Against Heretics, John was thrown into a vat of boiling oil in the Colosseum in Rome, around 90 AD. The Colosseum, which held 90,000 people, had recently been completed, paid for with 10,000 talents of gold brought back to Rome after the ravaging of the holy city and the Temple of Jerusalem.

Ironically, its gladiator battles to the death in all kinds of ceremonial games—which Hugh Nibley’s dissertation analyzes as manifestations of the religious-year rite temple festival—places all this in the context of religious, temple, and eternal symbolism. The Colosseum had thus become a slaughterhouse for faithful Christians, who were seen as public enemies of the Roman gods, Roman rulers, and Roman wealth.

But the Apostle John, who had come to see all of these things—the decadence and horrors of Rome up close, surprised everyone that day. On that one day, by coming out of persecution, being put in a vat of scalding oil, he emerged unscathed. According to Tertullian, the result was that thousands were converted, and John was sent to the Isle of Patmos in banishment and prison, just offshore from the seven cities in the Roman province of Asia.

So this was personal for John, and he could understand, as would others who were suffering similarly, the subtext of the power of God to prevail over the persecutions that Christians were enduring.

Finally, this brings us to a concluding point: what significance must John’s detailed allusions to these practices have had in the minds of Christians and Roman readers? These allusions were not just vague references or images for John—they were hard facts of world realities, just as the Christian promise of eternal life was new on the religious scene in the first century, so too was the Roman incentive of lifetime military retirement benefits. Both emerged in Rome in the 50s and 60s; both competed for the loyalty, faithfulness, and uncompromising dedication of their adherents.

In this war of competing paradigms of “The Good Life,” John presents a series of detailed visual images of the rewards to the righteous that will be far superior to anything the Roman Empire could ever offer.

In Jerusalem, the new King will bestow all privileges of divine citizenship not just upon individual loyal soldiers but upon his people as a whole, but also with an everlasting inheritance upon the posterity of each good soldier-servant, just as the diplomas granted citizenship not only to the retiree but to his sons and daughters.

The city of God will open its gates to all who come under Christ the Lord, and not just through the gates on the Roman roads leading into Rome, but through the twelve golden gates of the holy city, into a haven of heavenly health, protection, happiness, and devotion to the true Lord of Hosts.

This is a divine upstaging of the whole Roman Empire, surpassing any earthly privileges, benefits, or powers offered by any kingdom on Earth, then or now, whatever the dispensation or era in world history. This underlying dichotomy is always basically the same: good against evil, wickedness against righteousness, materialism against spirituality, Satan and his beastly minions against the building of God’s people of Zion.

For John, the rewards given to Roman soldiers after 25 years of service in the Roman army, obedient to the emperor, pale when compared to the everlasting rewards to be had as a people in the New Jerusalem under the Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.

Thus, the Book of Revelation can be understood as being about the granting of full citizenship rights to all heirs in the heavenly kingdom—all who complete their tours of duty, marshaled and directed not only here on Earth but ultimately in heaven.

John’s Revelation thus culminates with a thundering voice saying, “For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth.” Having cultural artifacts and historical backgrounds helps us see, even more clearly than ever before, how the Book of Revelation, as Joseph Smith called it, is indeed one of the plainest books God ever caused to be written.

In the name of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, amen.

Topics

The Book of Revelation

Seven Seals