- Dan Peterson

- August 2025

- Summary

Dan Peterson examines Brigham Young’s views and actions regarding slavery, servitude, and race in the 19th century, pushing back against modern assumptions that frame the issue only in terms of absolute slavery or freedom. He emphasizes that Brigham Young should not be judged by oversimplified modern categories but understood within his historical context.

Presentation

Introduction to the Clip

What I’m going to do first is show you just a short, five minute clip from something that we’re working on right now. Some of you saw the film that we did called Six Days in August.

We’re following it up with a series of short video documentaries that we’ve called Becoming Brigham, and they’re going to address all sorts of issues, background information, lots of interviews, some of it filmed on scene, and dealing sometimes with difficult issues–Brigham Young and race, Brigham Young and women, Brigham Young and violence, things like that.

And we’re getting really good contributions and cooperation from the Church Historical Department, which I’m very pleased about.

Format and Release

So what I’m going to show you today, they will normally be, I think, about ten, 15 minutes long, probably closer to 15. This will be about five minutes long, but it’s just a sample of what it will feel like. We’ll start coming out with these, I think probably in October-ish.

And they will be available for free. We want to get them as much as we can, as widely as we can.

So, anyway, take a look at this. It’s just a short sample.

- Camrey Bagley Fox: Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints represent a faith practiced by millions, a faith which has also inspired its share of controversy.

- Man: I think if you look at Brigham Young’s whole life, well, it’s a conundrum.

- Fox: It almost seems like he’s a human?

- I’m Cameron Bagley Fox, and together with John Wilson and Professor Daniel Peterson, we work to uncover unexpected twists in the character of a man that we thought we already knew.

- LaJean Carruth: So this is Pitman shorthand. It was published first in 1837, but I think. . .

- Fox: This is mind blowing to me because this is just little squiggles. I can’t. . .

- Carruth: I’d been working in shorthand for 30 years before I could really just read George well. I can put him together like a jigsaw puzzle. It was the first English language shorthand that allowed a skilled reporter to get a man’s or a women’s words verbatim, until the speaker got excited or mad and sped up, and then the shorthand deteriorates and I get very frustrated.

- Fox: Doctor Peterson sent me to meet LaJean Carruth, a premier shorthand expert who was first given a job transcribing shorthand 50 years ago for $1.60 an hour, and has been immersed in the work ever since.

- Fox: So this is different than this.

- Carruth: Yes. This is that. Yeah, yeah, it’s the angles and this is dark and this is light.

- Fox: The darkness and lightness makes a difference?

- Carruth: Yes.

- Fox: Okay. LaJean, I want to know how you got started in this work.

- Carruth: When I was 11 years old, I went down to the basement of my parents home and found an old “Improvement Era” open to an article on the Deseret alphabet. I was instantly, completely hooked, and decided, with all the wisdom of an 11 year old, that I was going to transcribe Deseret when I grew up, professionally.

- Fox: It seems like it’d be really difficult. You must be the most patient person on the planet.

- Carruth: A college roommate told me once. . . She said “LaJean, you’re an odd mixture of patience and impatience.” And she was right on. Frankly, it’s a gift. It’s tedious, it’s meticulous, it’s difficult. I pray a lot. People say, ”You have a fun job.” I say, “No, it’s not fun. It’s tedious and meticulous, and deeply, deeply meaningful.”

- Fox: I think we sometimes envision Brigham as kind of a harsh, forward man. What have you learned about how he treated others?

- Carruth: Those of us who have worked with Brigham Young’s words, either from the letters he wrote, or I’m working with the words in this shorthand, we see a completely different man, a kinder man, a caring man. He was bluntly spoken. He spoke in hyperbole, but he knew, and everyone who heard him knew, he spoke in hyperbole. A lot of his harshness is from incorrect transcription of the Journal of Discourses.

- George D. Watt published the Journal of Discourses. He had a large family to support. Willard Richards wanted him to take down sermons in the Tabernacle for him to publish in the Deseret News, but he didn’t want to pay him, and that doesn’t work. So after some rather acrimonious exchanges of letters, it was decided that George D. Watt would be allowed to publish these in England as a private venture, but with the endorsement of the First Presidency.

- But as George D Watt transcribed, and I will say, as everybody I have seen transcribe, he changed the words.

- Fox: Really?

- Carruth: Brigham Young in 1853 was talking to saints who had just crossed the plains that season. And in those early days, it was really an arduous trip. And he said some had lost faith because the trip was too hard.

- And then he said, “Do some of you who have come this year feel this way? Kind of an understanding question. But Watt changed it: “Some of you who came this year feel this way.”

- Brigham Young said one day, “If I am perfect in my sphere. . . .” Watt changed it to “I am perfect in my sphere.” Watt made up things that were simply never said.

- Brigham Young would say “we.” For example, this is a quote, just an example, “We need to do better.” George Watt would change it to “You need to do better.”

- And so the changes from questions to statements, just the changes in his language: Brigham Young would say “heart” over and over and over again. Watt changed it to “mind” over and over again. From the realm of the spirit to the realm of the intellect. So the changes in his words drastically changed how he appears to us and how he’s seen.

- Fox: Absolutely. It makes him seem a lot more authoritarian rather than . . .

- Carruth: And a lot more critical. Brigham Young knew he was human. He knew about his tongue. Once he said, if you see me just standing quietly, I’m trying to get a hold of myself. He said he was as naturally tempted as any other man, but the cry of his soul, the longing of his soul, was to find the truth, live the truth, and serve God.

- But his heart was pure. He wanted to build Zion, that is Brigham Young that I’ve come to know and love.

- Fox: Thank you.

Modern Attacks Against Brigham Young

That’s a good setup for what I’m trying to do today. One of the things that I’m taking issue with, and that has been a motivating factor in Six Days in August and this project and so on, is I am very disturbed by attacks that I see, including from members of the Church against Brigham Young, that Brigham’s being thrown under the bus in many ways.

And one of those areas is his views on race. And one of the things that has always made that worse for me was the idea that Brigham Young presided over the passage of a law in 1852, in the Utah Territory, that authorized and legalized slavery within the boundaries of the territory. I’m going to be responding to that claim in this.

Responding to the 1852 Claim

Now, recently, and I’ll just read the first part. I’ve actually chucked how I was planning to speak to you. I was trying to put together a very tight case, which I can make, against the claim that Brigham Young favored slavery. But I couldn’t get it below 60 pages, and that was a little bit long for this presentation. So I’ve decided to just wing it to a certain extent. So I hope you’ll bear with me. But I will read a couple of portions.

Extreme Accusations

Recently, an irresponsible and inflammatory article about the reelection of Donald Trump to the presidency January 7th, unleashed a flood of insulting comments about Latter-day Saints and their leaders, both historical and contemporary. In one of them, a vocal critic confidently declared that Brigham Young’s views on race were essentially indistinguishable from those of the Nazis.

Now, while extreme such sentiments are far from rare, I’ve encountered them a lot. He was a vicious, horrible racist who hated blacks and so on. But that accusation simply cannot be sustained. And I’ve often seen the claim that this 1852 act in relation to service was a way of Brigham Young endorsing black slavery in the territory.

Clarification

I accepted that idea uncritically – I thought it was true. There was no question about it. I regretted it, I thought it was really unfortunate.

But it is not true. And so, I want to address that in what I’m having to say today.

Historical Context and Quotation

Now let’s stipulate upfront that Brigham Young said some things about race and about blacks that make us cringe today.

I’ll give you just one example.

“I will say then, that I am not, nor ever have been in favor of making voters of the Negroes or jurors, or qualifying them to hold office, or having them to marry with white people. I will say, in addition, that there is a physical difference between the white and black races, which will forever forbid the two races living together upon terms of social and political equality.

“Inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together, they must be the position of superior and inferior. And I as much as any other man, am in favor of the superior position being assigned to the white race.”

That was a quotation from Abraham Lincoln1, the Great Emancipator. It’s not from Brigham Young.

Nineteenth Century Americans and Race

Brigham Young was born in 1801, Abraham Lincoln in 1809. They were rough contemporaries, and attitudes like that were common in their day, even among opponents of slavery.

The majority of Americans who opposed slavery in the 19th century did not do so because they believed black people to be equal to white people, but because they believed slavery to be wrong and immoral.

Illustrations of Attitudes

I don’t want to belabor the point too much, but I want to justify my claim with a few more illustrations. And these could be multiplied at length.

John Jay was an author of The Federalist Papers and the first Chief Justice of the United States. His son Peter was an ardent opponent of slavery. In fact, he was the former president of the New York Manumission Society, advocating the freeing of slaves, and he was a delegate to New York’s 1821 Constitutional Convention.

While he was there, he remarked that in his opinion, “In general, the people of color are inferior to the whites in knowledge and industry.”

Samuel Young’s Argument

And a delegate named Samuel Young to that same New York convention, and this is in the North, is no relation to Brigham, took these opinions even further.

Young argued that:

“The minds of the blacks are not competent to vote. They are too much degraded to estimate the value or exercise with fidelity and discretion that important right. It would be unsafe in their hands. Their vote would be at the call of the richest purchaser. So this class of people should hereafter arrive at such a degree of intelligence and virtue as to inspire confidence, then it will be proper to confer this privilege upon them.”

For the present, however, his advice was to:

“Emancipate and protect them, but withhold that privilege which they will inevitably abuse.”

Common Opinion in the North

He expressed an opinion that was common throughout the North: Black people should be freed from slavery, but they should not be made equal members of the community.

They were essentially a dependent population, much like women and children.

Brigham Young as a Man of His Time

Now, please note that neither Abraham Lincoln nor Peter Jay nor Samuel Young invoked any religious justification for their opinions. This is the way people thought.

I’m not playing the venerable game of ‘what about’ ism, I think it has very little value. And I’m certainly not trying to denigrate Abraham Lincoln, for whom my admiration is enormous. But I will argue that in this specific regard, Brigham Young was a man of his time, as was his great contemporary, the 16th president of the United States.

We might wish that he were a little bit different, but prophets are human, and that’s the way it is.

Progressive for His Era

And in fact, I’m going to argue that by the standards of his time, he was progressive. And I don’t mean that in the current sense. (I’m not meaning that as a negative, by the way.)

But he was at the vanguard of opinion in terms of his views of blacks, but he was a human. Except in the case of his only perfect, begotten son, Elder Holland pointed out in his April 2013 General Conference address, imperfect people are all God has ever had to work with. That must be terribly frustrating to him, but he deals with it. So should we.

And when you see imperfection, remember that the limitation is not in the divinity of the work.

Lessons from History

Now, one of the great epiphanies that the study of history can offer is the realization that just as our ancestors had funny attitudes, wore funny clothes, held odd ideas, and suffered from surprising blindspots, morally and otherwise, our descendants view of us will probably be tinged with at least some condescension and even some disapproval, probably laughter. It’s inevitable.

“For what do we live,” says Mr. Bennet, in Pride and Prejudice, “but to make sport for our neighbors and laugh at them in our turn?”

Sources on Brigham Young and Slavery

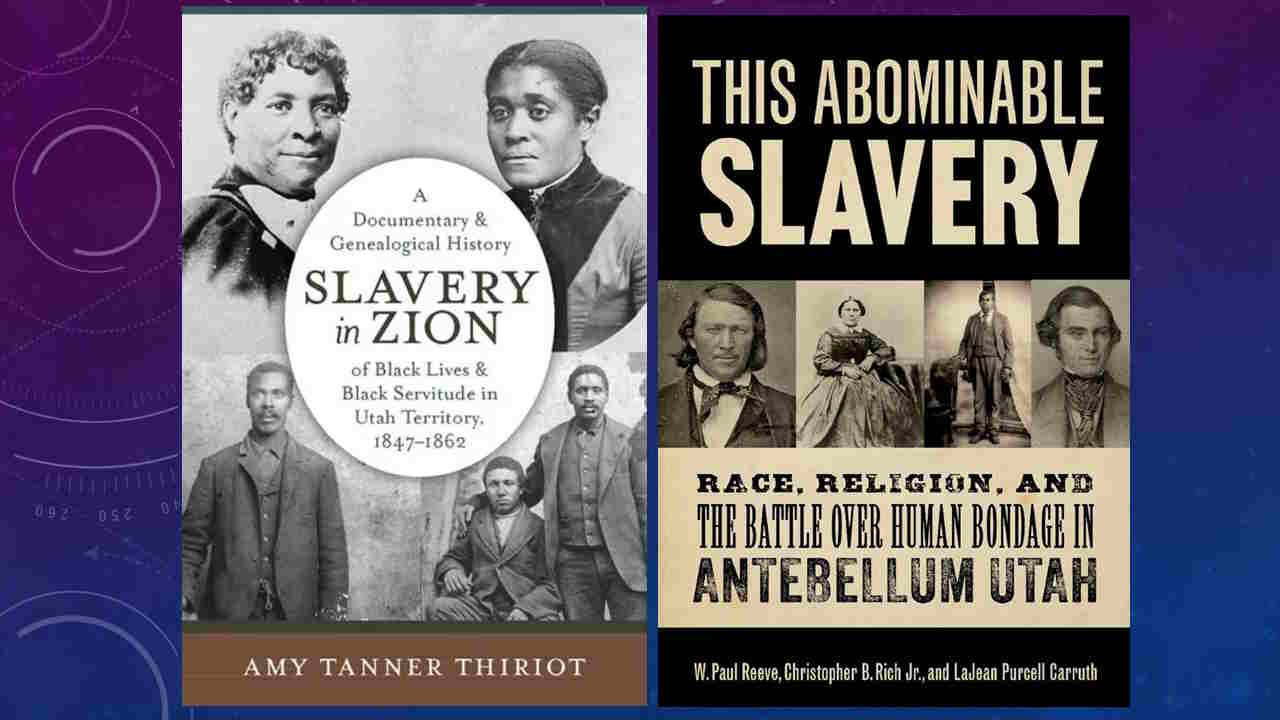

Now I will be relying for this presentation on two books that have fundamentally transformed my views on the subject of Brigham Young, race and slavery.

They are First, Amy Tanner Theriot”s book, Slavery and Zion, and second; Paul Reeve, Christopher Rich and LaJean Purcell Carruth (whom we just saw in that little clip) called This Abominable Slavery.

Latter-day Saints and the Issue of Slavery

Latter-day Saints had to face the issue of race and slavery very early. On July 22nd, 1847, when the first 40 immigrants arrived in the Salt Lake Valley.

Among them were three enslaved men, two of whom had membership in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The valley was also home to members of the indigenous Ute tribe, who would sometimes barter captive women and children to Spanish colonizers. So slavery and race were issues from day one.

The Question of Slavery in Zion

So the question of whether Latter-day Saints would accept or reject slavery in the territory in their new Zion confronted them on the day they arrived.

Five years later, after Utah had become an American territory, its legislature was prodded, forced really to take up the question which was then roiling the nation: would they be slave or free?

Records of the 1852 Legislative Session

Now, George Watt, whom we’ve also heard about, who’s the official reporter for the 1852 legislative session, reported debates and speeches in Pitman shorthand.

They remained in their original format, virtually untouched for more than 150 years, until LaJean Purcell Carruth transcribed them.

And that’s one of the great contributions of this book, This Abominable Slavery, that the authors draw extensively on these new sources, the records of the territorial debates, during which the legislature passed two important statutes that I’ll come to, and, and I’ll show you how those differ from slavery.

The Context of Sectional Divide

And This Abominable Slavery puts the debates within the context of the nation’s growing sectional divide.

You may have read some of American history. You may know that in the 1850s, slavery was becoming an issue, and some were worried that it might turn into a conflict.

Did it? Yeah. Almost 650,000 people died in that conflict, and there were people who were trying to avoid it.

Sources for This Talk

I’m going to draw heavily upon these two books. I make no claim of originality for what I’m doing today or even in this paper, the 60 page (actually it will probably get longer), which I’ll put out somewhere, sometime when I finish it.

But, I’m drawing on them and repurposing what they had to say. These are very dense books, and I wanted to make an argument with them about Brigham Young.

Early Attitudes Regarding Slavery

Before I enter the main body of my argument, though, I want to quote a couple of paragraphs from the introduction to a book by Eric Metaxas called Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery.

This is what Metaxas has to say. And I think we have to think ourselves into this mindset. It’s hard for us. We see slavery is just simply evil. How could anybody possibly ever have backed that?

Quotation from Amazing Grace

“There’s hardly a soul alive today who wasn’t horrified and offended by the very idea of human slavery. We seethe with moral indignation at it, and we can’t fathom how anyone or any culture ever countenanced it.

But in the world into which Wilberforce was born, the opposite was true. Slavery was as accepted as birth, and marriage and death was so woven into the tapestry of human history that you could barely see its threads, much less pull them out. Everywhere on the globe for 5000 years, the idea of human civilization without slavery was unimaginable.

“The idea of ending slavery was so completely out of the question at that time that Wilberforce and the abolitionists couldn’t even mention it publicly. They focused on the lesser idea of abolishing the slave trade, on the buying and selling of human beings, but never dared speak of emancipation, of ending slavery itself.

Their secret and cherished hope was that once the slave trade had been abolished, it would then become possible to begin to move toward emancipation. But first they must fight for the abolition of the slave trade. And that battle, brutal and heartbreaking, would take 20 years.”

Applying the Background to Brigham Young

So it’s against that background that we need to view the question of Brigham Young and slavery.

And so that’s what I’m going to try to do.

Types of Labor Relationships

One thing that we need to understand is that for people in Brigham Young’s era, there were different gradations, different kinds of relationship between master and employee or employer and employee.

We tend to see a binary. There is free labor, there is slave labor, nothing really in between. But for somebody in the early 19th century, there were all sorts of gradations.

Examples of Labor Systems

If you were in Russia, there was serfdom. If you were in the United States, and Great Britain, there were apprenticeships which were not very different in some situations from slavery for a temporary period.

There was indentured servitude, people that I know of who came over, even as Latter-day Saints who couldn’t afford the passage, would sell themselves into indentured servitude for a period of 5 or 10 years or something like that.

Brigham Young’s Own Experience

People of that era were used to the idea of not quite free labor, but for a term. And then, of course, also with slavery.

Brigham Young himself had been an apprentice. And, that was very like slavery, as I say. So that we need to understand.

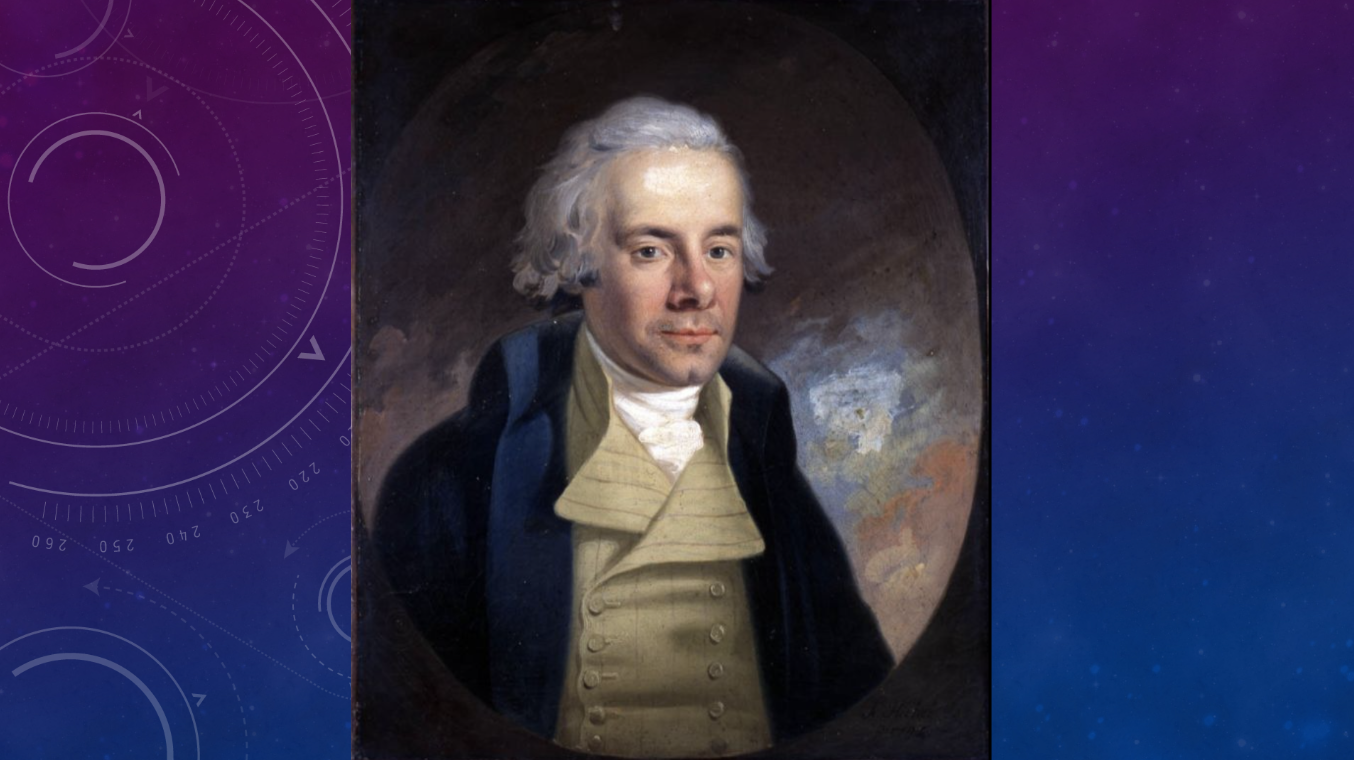

Joseph Smith’s Ideas on Slave Emancipation

Now, first I want to say something very briefly about Joseph Smith. There’s an actual photograph of him. (Laughter) You didn’t know they had color photography at that period, but they did, clearly.

Joseph Smith had to deal with the question of slavery. One of the first members of the church in Kirtland was a black man, a free black man. But there were questions about what to do about free blacks and unfree blacks and so on. And he had to deal with the question division.

When members of the Church in the North heard that there were members of the Church of the South who owned slaves, they were horrified by it. And there was a fear that the Church would break apart about that sort of thing as the country would eventually break apart when he ran for the presidency.

I’m not doing justice to Joseph’s attitudes on slavery or race issues. They are complex and interesting, and in some ways, they raise all sorts of questions. We know he ordained black people. Brigham Young in 1849 described one of those men ordained by Joseph as one of the finest elders in the Church.

But I’m not going to deal with the priesthood issue today. Too little time. But in Joseph’s presidential campaign, one of the things that he suggested in his platform was using public money to free the slaves.

Joseph Smith’s Proposal

The idea was to respect the property rights of enslavers by paying them off, trying to avoid strife, by giving them fair market value, in a way, for their possessions, their property.

And so Joseph proposed two ways of doing that: selling public lands and reducing the salaries of members of Congress. Wonder why that idea never caught on.

British Example

But that was his proposal. And when the British Empire finally did end slavery, not just the slave trade, but slavery altogether, abolished it in 1833, the British Empire paid 20 million pounds sterling to buy off the slave owners, mostly in the West Indies, to buy their property from them so that they could avoid social strife.

Is that an evil thing to do to pay enslavers for their “property”?

Well, yeah. On one level I see the objection, but on the other it avoids a war. And, and so it was a prudent thing to do.

How much was 20 million pounds sterling in 1833. How much would that be today? I’ve seen various figures in different sites give different estimates of it, but one that I saw, I put it as high as $450 billion. That’s not an inconsiderable sum.

And Wilberforce learned about this just before he died. And he said, I am so grateful that the Empire has been willing to put up that money to end this blight upon us.

Returning to Africa

Okay, so that was Joseph’s idea of, of purchasing the freedom of slaves and also of sending some of them back to Africa, as many of them were first generation.

This was also an idea that was in the wind. You know of the country of Liberia with the capital called Monrovia, named after President James Monroe. That was the idea of sending people back to Africa, if not to the Africa they came from, at least to Africa, where they could govern themselves.

Slavery in Early Utah Territory

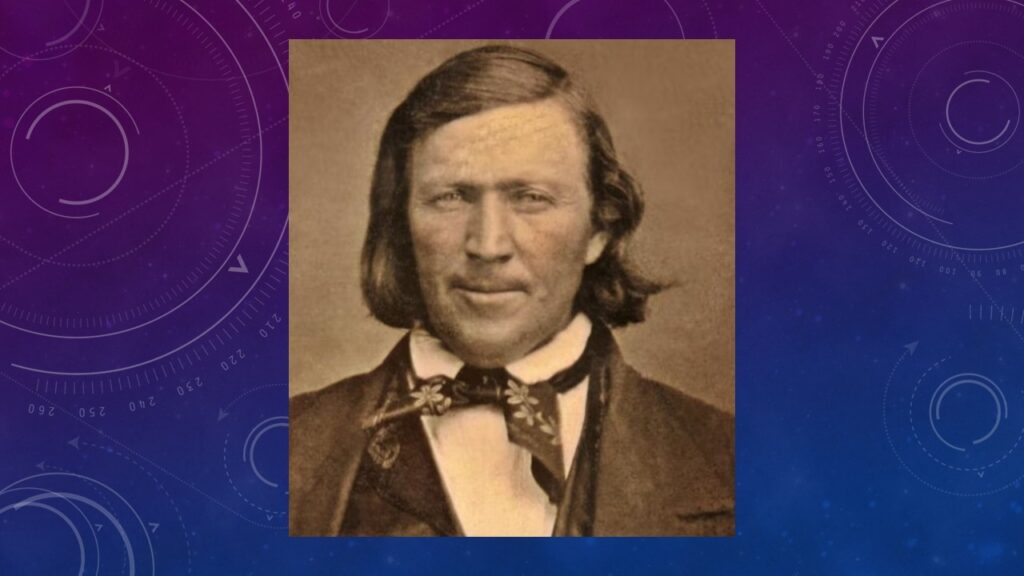

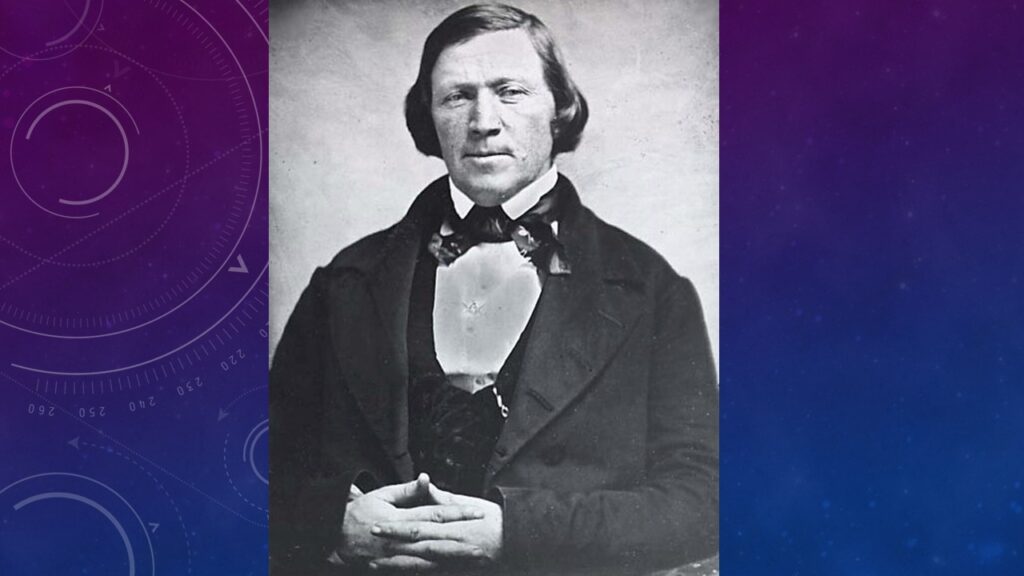

But what about early Utah? Well, let’s get to the man that I’m really talking about here. And that’s a suitably grim looking picture.

The Scale of Slavery in Utah

The scale of the problem in Utah was not large. There were, by most estimates– I’ve seen it in print–I asked Paul Reeves about this just last week during the interview that I was doing for this Becoming Brigham series.

The estimates are generally between 30 and 40 enslaved people in Utah during the 1850s. That’s not a huge number. And so it was probably not at the top of Brigham Young’s priorities. He had lots of issues to deal with, but he still tried to deal with it.

Neutrality as the First Approach

Now, the first attempt was neutrality. And you have to understand that, according to the Somerset decision said in 1772 issued by Lord Mansfield in the British High Court, if there were no positive laws enshrining slavery, slavery could not exist.

Slavery was not a natural state. It had to be approved, authorized by positive law. So his argument was slavery could not exist within Great Britain, in its possessions, maybe, but not within Great Britain.

Early Latter-day Saint Attitudes

When the latter day Saints came to Utah, you see from their debates and the records we now have that their attitude at first was, “We have not authorized slavery, therefore, there can be no slavery here. Slavery will not be recognized in Utah.”

They didn’t ban it. They didn’t authorize it. It wouldn’t exist, would have no legal status. It could not be enforced by a court because there was no law to do so.

And so that was their initial approach, their initial idea.

Southern Enslavers in Utah

Now, it could cause problems because there were some southern enslavers who came to Utah bringing their slaves with them. What do you do with those slaves? What if they try to run away? Should the government try to enforce their slave status?

The general attitude of the Latter-day Saints and the leaders in the legislature who were basically leaders of the church was: no, no, we will not do it. Until the problem is forced upon us, we won’t do it.

Ute Slave Traders

The problem was forced upon them in a way they probably hadn’t anticipated. I mentioned already the Ute tribe, who were famous for their slave trading and had been for about 200 years.

Within a few months at most, maybe within a few weeks, there are cases reported of Ute slave traders coming to Latter-day Saint settlers, offering them slave children for sale.

The Latter-day Saint Response

The Latter-day Saint response was horror, and these are mostly northerners. The idea of owning a human being, they didn’t like it at all, and they said no.

To which the Ute slave trader responded in at least two cases that I know of, and several others that are rumored, “Well, if you won’t buy the slave, the slave is of no value to me, and I’ll kill it.”

Tragic Outcomes

And the latter day Saints don’t believe it. And so the child is killed in front of them.

They had, in one case literally dashed against rock, in which case the Latter-day Saints say, “Okay, okay, okay, we’ll buy his sister.”

The Indian Indenture Act

Well then, what’s the trouble? With the laws of economics, supply and demand, you start buying slaves. What are you going to get? More slaves. They’ll bring them to you.

The Utes traveled as far as California and New Mexico and Colorado and maybe beyond selling their slaves. Now they have a market right in their backyard. This is great. So they start coming with more slaves.

Latter-day Saints are faced with an issue. What do we do with this? We don’t recognize slavery. There’s no legal status for it. But also there was some worry. What if we do buy them? Then the feds could come down on us and say, well, you’re violating the prohibition of slavery in the territory. We could go to jail. Or we could have a property taken, things like that.

We need to deal with this. So they began thinking they needed to come up with a law, which they did, called the Indian Indenture Act, which forced them to begin to deal with slavery.

Brigham Young’s Position

Now, on the one side was Brigham Young. Well, on one side to the far side were the enslavers who just wanted slavery legalized there.

Brigham and others said, “No, we will not do it, but we will come up with some sort of moderate middle ground if we can.”

Orson Pratt’s Opposition

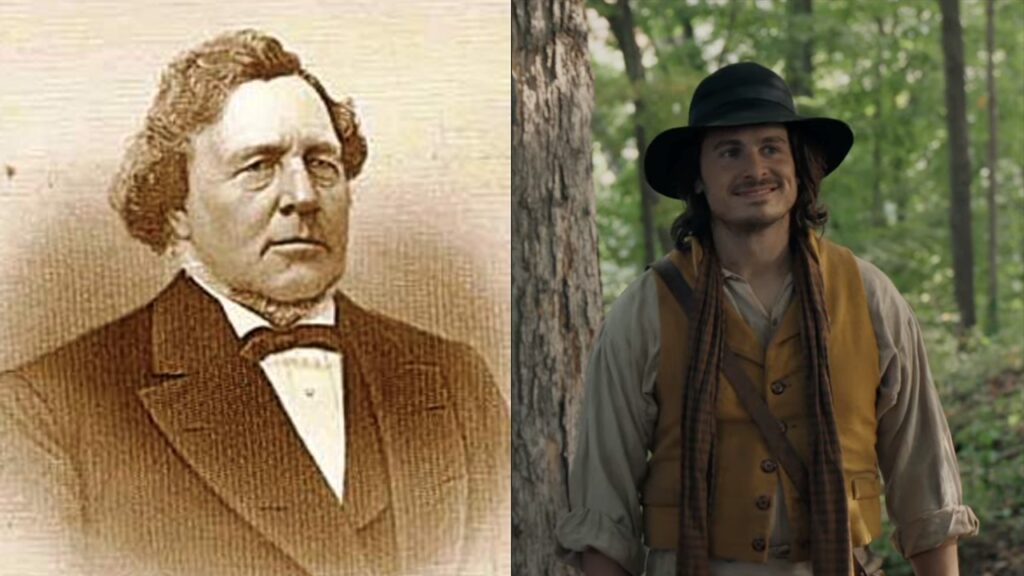

One who opposed that was Orson Pratt. Orson Pratt was a member of the legislature and, of course, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve.

And Orson thought this was all slavery. Indentured servitude was slavery. Apprenticeships were slavery. This is wrong. He’s the one on the opposite side, the person arguing against what Brigham eventually tried to put through.

Objections in the Legislature

To that there were many objections. One is George A. Smith, who is shown as he really looked on the right, and then saw this impression of him on the left (laughter).

George A. Smith was one of those who did combat with Orson Pratt in the legislature.

George A. Smith’s Position

He said, no, we are not trying to introduce slavery here. This is not slavery.

We want to introduce a form of indentured servitude or something like that, apprenticeships or something, where we can bring these children into our homes, raise them, and then after a fixed term, they’ll be able to be free.

Brigham Young’s Attitudes on Race

So now let me, let me come back to Brigham Young. What were his attitudes on race? It’s quite clear that Brigham Young had the notion, based on his understanding of the Bible, probably notions that he’d picked up from his Protestant background in the Protestant environment, and it was around the Latter-day Saints, that blacks were determined by divine law to be servants.

This is the rule of Canaan, you know, descent from Canaan, descent from Ham, all those sorts of ideas went into it, that blacks were meant to be servants of others, the seed of Abraham. But he did not believe that that meant slavery.

Brigham Young and Slavery

Now, this is important to understand. Brigham Young throughout his life, continually from an early period, says it is not right to own property in human flesh.

Chattel slavery is immoral. It does damage not only to the slave, but to the person who owns the slave. It corrupts everybody, and it’s wrong, and it has no place in Utah. I will not allow it here.

So get that out of your mind that Brigham Young favored slavery. He didn’t, absolutely did not.

But he did think, and we would see this as racist obviously today, he did think that, well, blacks are meant to be servants of the seed of Abraham. And what he was trying to do is hold together some sort of middle ground, find a middle ground where there would be peace within his community, between the southerners who had come with their property, expecting the government to enforce their property rights, and most of the saints who said this is wrong shouldn’t exist. We don’t like it.

Gradual Emancipation Laws

So what he tried to do was come up with what are called gradual emancipation laws. And, and that is really important to understand.

There were such laws in various places, notably in Indiana, Illinois, and some places in the northeast, that were clearly set up with an intent to end slavery gradually, peaceably, as much as they could. And the law that Utah would eventually come up with is based on that.

Historical Models

In 1833, when the British Parliament did its Slavery Abolition Act, one of the things it did was to set up a system of apprenticeship, the idea that people wouldn’t move from slavery to total freedom, there was worry about how they even handle that, but set them up in a system of apprenticeship that would eventually have a term and allow them to be free.

Even Quakers, who were generally considered abolitionists in the broad sense, many of their newspapers opposed immediate abolition. And that’s what the territorial legislature of Utah tried to do.

An Act in Relation to Service

An Act in Relation to Service (1852)

Now, I want to go through this in some detail. I’m already running out of time. You could see I could not have made the 60 page paper work here.

But as I say this, what was called “An Act in Relation to Service,” that was passed by the Utah Legislature in 1852, dealing with black servitude. Brigham Young insisted that it not be called an act in relation to slavery because this is not slavery. We don’t want slavery here.

So it was patterned on the gradual emancipation laws of the Northeast, the Midwest, rather than on the slave codes of the South. And that’s really important to understand.

What is clear is that the law didn’t include an absolute prohibition of slavery, but it didn’t include any express approval or protection of slavery, as the New Mexico law did a decade later.

Brigham Young and Slavery as Contract Labor

And, and you can see that what it actually did was to create a system of quasi indentured servitude for enslaved African Americans that closely approximated laws in Indiana and Illinois after the passage to the northwest Ordinance.

It tried to shift chattel slavery into a system of contracted labor. The idea was to treat slavery as contract labor. And I’ll give you specific examples how.

Protections for Servants

The act limited the term of service. The bill unambiguously recognized servants as human beings with personal agency.

They were, for example, permitted to testify in court. And they did, in some cases. The sample’s very small, 30 or 40 people, not that many court cases, but we know cases where they did, and they could even testify against their master.

And if the court found that the master was not obeying the rules of the bill, that person would be freed–not just transferred to some other owner, freed. Labor could only be sold with the consent of the servant.

You think, did they all consent? We don’t know in reality. But the law forbade the breaking up of families, which was done. If you read Uncle Tom’s Cabin, that was done in southern slavery.

It forbade sexual abuse or rape. Now, if you know anything about southern slavery, you know that there was a lot of that kind of abuse going on between masters and slave women. It forbade it and punished it severely.

Living Conditions and Education

The master must, according to the bill, provide, “comfortable habitations, clothing, bedding, sufficient food and” get this, “recreation.”

There were no slave hunting parties. If a servant under this law escaped, ran away, there would be no posse sent out to get him or her.

The master must provide at least 18 months of education between the ages of six and 20 years. It was a requirement that stood in stark contrast to the slave codes in many southern states, which made it a crime to teach a slave to read and write.

In Utah, you were supposed to get 18 months of education which, frankly, probably compares fairly well with what a lot of the white people were getting during that period in Utah. They didn’t go to school very long in many cases.

Legal Protections

Masters were forbidden to engage in cruelty or physical abuse, and the person being abused could sue.

Masters were limited to requiring, “reasonable hours of work.” The bill proposed no restrictions on property ownership by a servant or the ability to testify in court, didn’t require travel with a pass or contain any of the other countless disadvantages that American legislatures had shackled slaves with in the past, and unfree laborers, even free black people, were under some of these rules, but not in Utah.

Any punishment should be “reasonable and guided by prudence and humanity.” If not, a probate judge could remove an enslaved person from a household.

Brigham Young’s Intent

“Let servants live with their masters, and serve out the time agreed on when they came here, and when the master forfeits the rights of their servants, let them be free, the same as white people. For master violated provisions,” this is Brigham Young speaking, “the servant should go free rather than be transferred to a different master.”

This was a significant policy change.

One of the goals of the bill seems to have been to discourage slaveholders from bringing slaves into the territory, because their property rights would be endangered.

You bring a slave into the territory, he or she belongs to you completely, and the offspring belong to you completely. In Utah that wasn’t going to be the case.

Children Born Free

Possibly most importantly, section three of the bill said that enslavers don’t have a permanent hereditary claim to a slave’s descendants. Children born to an enslaved mother are born free.

And this is the really clear gradual emancipation aspect of it. The second generation would not be slaves or servants at all. They were born free.

Limits on Masters

It limited a master’s authority over a servant. A servant was not a commodity to be bought and sold.

If the person wanted to sell your labor to someone else, you had to consent to that, and you would be brought in to testify before a probate judge without the master present under the provisions of the bill.

So to me, this is very clearly not slavery. It’s something very different from what we saw in the South.

And there are scores of quotations from Brigham Young saying this is exactly what he intended. He wanted some middle ground that it would be more like indentured servitude or apprenticeship, but it would never be slavery. He would not permit slavery to exist within the territory of Utah.

Transition to Case Studies

Now I want to talk about a couple of specific cases.

Jane Manning James and Isaac James

Jane Manning James and Isaac James

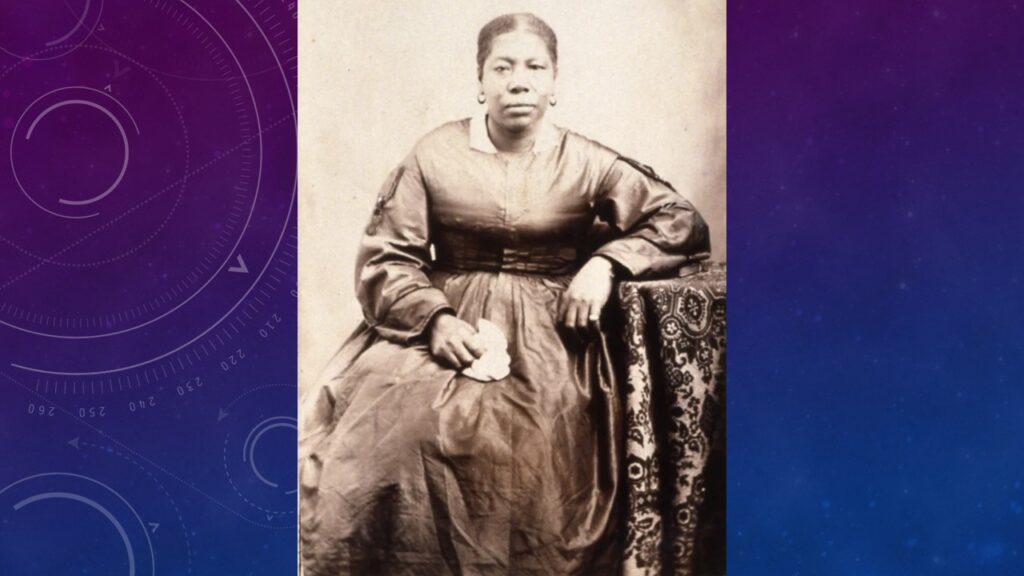

This is a famous picture of Jane Manning James, who is possibly the most famous 19th century black member of the Church.

I want to say something about her and her husband. Mark Ashurst-McGee just kindly shared with me a story that is really interesting.

The Kanes and the Saints

You may remember Thomas Kane, a friend to the Latter-day Saints, but his wife, Elizabeth never really warmed up to the Saints, or to her husband’s clear affection to them.

In one of her accounts she tells the story of being with a group traveling to the south of Utah. And Issac James, who was her husband, was not feeling well, he was suffering from rheumatism.

So a Latter-day Saint member of the company puts Isaac James in his wagon because he thought it would be more comfortable for him, that he could ride in that wagon.

Elizabeth Kane’s Shock

And Elizabeth Kane, although her husband is a noted abolitionist, was more of the upper crust society, was shocked by this.

Why would a white man allow a black man to ride in his wagon?

And then she’s really horrified when she comes into a house in Fillmore, I think, and Brigham Young is there, it’s a hotel actually.

Brigham Young is there and because poor Brother James is suffering from rheumatism, Brigham Young helps him on with his coat.

An Illustration of Brigham Young

To see a white man, to see the pontiff of the Mormons treating a black man like that? It shocked her. She was horrified by it.

That, I think, says a lot about Brigham. It’s a nice illustration.

Green Flake

Green Flake in the Salt Lake Valley

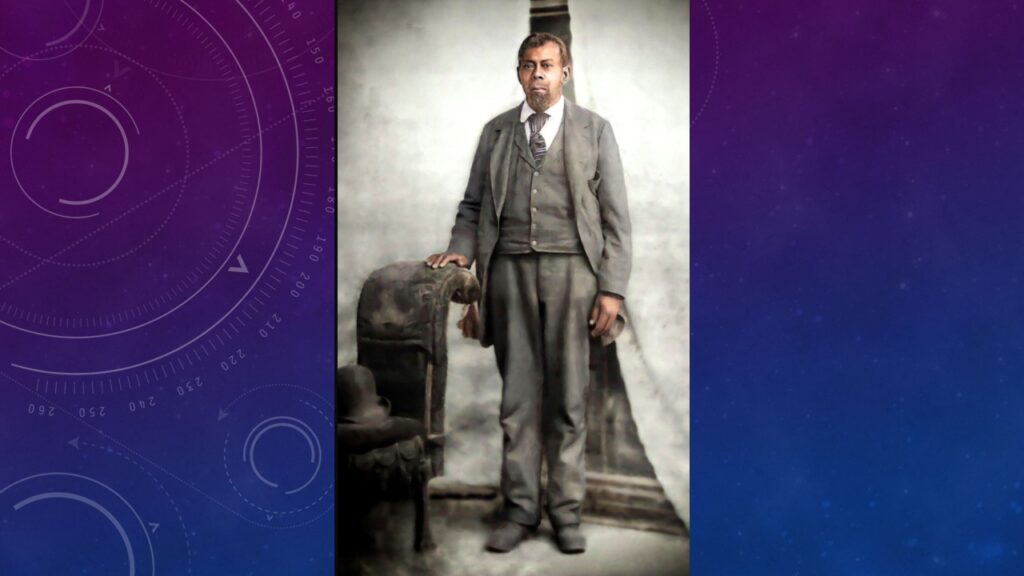

Or Green Flake, the other most famous black member of the Church. Green Flake was one of the first three to come into the valley. There were three enslaved people I mentioned, he was one of them.

Brigham Young allegedly, according to many accounts, turned to them, to those three black men, when Brigham arrived there and was standing next to them, he said, “Brothers, you are now every bit as free as I am.”

Brigham Young and Green Flake

Now it didn’t work out quite that well. But by 1853 at least, Brigham Young had purchased Green Flake from his owner, and had freed him and set him up with a farm in Salt Lake Valley.

And here’s another interesting story: Green Flake, about that same time, marries a woman named Martha, who belonged to a family.

And Green and Martha were taking produce from their farm and giving it to the family that enslaved her as payment for her freedom.

Brigham Young heard about this and said to them, “Don’t you give them another thing. You owe them nothing.”

A Rejection of Chattel Slavery

Does this sound like a passionate fan of chattel slavery to you?

When Brigham Young dies, Green Flake comes, and he insists on digging the grave for Brigham Young because of his affection for him.

Green Flake lives into the 1900’s, early 1900’s, and is held in great affection by people across the valley.

Context of Brigham Young and Slavery

I don’t want to say everything is rosy but it’s not Nazi Germany. Good grief, come on.

And it is not southern chattel slavery, by any means. I could tell you more stories, but I’m almost out of time.

Conclusion

Let me just conclude with something I wrote up for the original paper–sort of.

It’s become fashionable in recent years to demonize Brigham Young as a racist, even a vicious one; in some cases to essentially to forget that there was anything else to him. I resist this.

He wasn’t perfect, of course, nor has any subsequent apostle or president of the Church been perfect, nor am I, nor are his critics.

Brigham Young, Race, and Perspective

“Use every man after his desert,” wrote Shakespeare in Hamlet, “and who should ‘scape whipping?”

Or to paraphrase, “treat everybody purely according to his or her merits, and who wouldn’t be worthy of censure or even punishment?”

In racial matters Brigham Young said some things that jar us today and that we cannot endorse. There’s no denying this.

He was as we all are, even the prophets among us, a man of his time and culture and background.

But he was a good man, a remarkable man, indeed, a great man. A sincere disciple of the Lord and a prophet who sought to do God’s will.

Brigham Young and Slavery in Context

He was a racist by our standards, yes. So was Abraham Lincoln. So was probably every abolitionist, or almost every abolitionist, of the 19th century. But his was a paternalistic racism.

Contrary to the accusation that I opened my remarks with, he wasn’t the toxic and genocidally lethal racism of the Third Reich.

Although many would be surprised, and those who hate him will be displeased to learn it, Brigham Young opposed slavery–vocally, repeatedly, loudly, and effectively.

Hoping to avoid conflict, he favored gradual emancipation, as did others across the nation.

And his fear of conflict wasn’t misplaced. In 1861, only nine years after the act that he sponsored in the legislature, the American Civil War erupted.

Final Reflection

It killed more than 620,000 people and injured several million more.

It left a gash across the nation that maybe has not fully healed even now. And remember, those figures are out of a much smaller American population than today.

Standing with Brigham Young

I have to be straightforward, I choose to stand with Brigham Young.

The soul that on Jesus hath leaned for repose,

I will not, I cannot desert to his foes.

Brigham Young and Slavery: A Peaceful Solution

And on the specific issue of slavery, President Brigham Young was, notwithstanding the dismissive stereotype of him that is currently in vogue, on the side of the angels.

He was trying to work out a peaceful solution to the problem that would eventually almost destroy the United States.

A Final Note of Defiance

And I would say finally, as a final note of defiance, anybody who presumes to pontificate on the subject of Brigham Young and his attitudes toward people of black African descent, without being thoroughly familiar with the information contained in Slavery in Zion and This Abominable Slavery, simply doesn’t deserve a hearing.

They don’t know what they’re talking about. That’s the bottom line of what I wanted to get across to you today.

Thank you.

Q&A

Reliable Books

Scott Gordon: Are you aware of any other books in addition to This Abominable Slavery that have been, or will be written, that will help correct past incorrect impressions of Brigham Young?

Dan Peterson: Well, I think This Abominable Slavery is important partially because it represents new sources. What might be in the works now, I don’t know. But nobody’s had access to these territorial legislative debates until now. So now we can see, what were they thinking when they framed this bill? What were the issues? And you have over and over again, explicit denials from Orson Spencer, George A. Smith, Willard Richards, and others who say, “This is not slavery. We don’t want slavery. We’re trying to create something that isn’t slavery here.” I don’t think there is anything else that has come out yet on the basis of those materials.

Black and White Thinking

Scott: So do you think our modern black and white political positions impact this discussion at all, whether you’re all in for slavery or all out for slavery?

Dan: I think they do, because, of course, racism is one of the worst things you can be accused of now. And nobody wants to defend slavery. There may be somebody somewhere, some whack job, but almost nobody wants to. And so if Brigham Young is accused of favoring slavery, that automatically makes him look terrible. But if you understand the nuances of the situation, realize he was not talking about slavery, that changes everything.

But we have this binary view, as I said. We see slavery or free labor. Well, for a 19th century American, that wasn’t the way it was. There were all sorts of forms of unfree labor that many of them had worked under. They had been apprentices or indentured servants and so on. So it wasn’t so foreign to them. This is something you just did.

Slave Trade in Native Americans

Scott: What did Brigham Young do about the Utes selling and or killing kids they wanted to sell to the Saints? How did that resolve itself eventually?

Dan: Well, eventually what happens is that there were several wars and the Ute trade in slaves was gravely damaged. It really hurt the Ute economy. But by authorizing Latter-day Saints to purchase children from the Utes but not make them slaves, that kind of helped with the issue; that you could buy them and bring them into your household.

So Brigham Young himself had a girl that worked in his household named Sally, who was a Paiute or Goshute, I don’t remember which, who had been captured by Utes, and, directly or indirectly, he bought her. He bought several slaves we know of, including black slaves, and then freed them. So that’s what he did.

She grew up free working in his household, not necessarily treated as his daughter, but treated reasonably well. And, and then eventually, some of you may recognize this name, she married Chief Kanosh, which I think was rough for her. It was a cultural shock for her to go from this really nice house in Salt Lake to living down south in an Indian tribe, and she died about three years later.

Second Class Saints

Scott: Interesting. Do you have any thoughts on the book Second Class Saints by Matthew Harris?

Dan: The main thought I have on that is that I bought it today. I haven’t read it yet.

Plans for Publication

Scott: Are you expecting to publish a longer paper in addition to what you put with FAIR?

Dan: Yeah, probably. I just realized about Tuesday night that I cannot do this. I can’t do it in time for Friday. And so I’m going to have to get back to it and write it up. Now again, I say, this will not be original research on my part, for the most part. It’ll be using other people’s. They have done marvelous things. And both those books that I recommend are very dense. They have prowled through the primary sources and so on. But what I do is take it and kind of make an argument, that’s implicit in their books, I think. I don’t think they disagree with what I say, but, I want to draw it out and make that point about Brigham Young.

Recommendations

Scott: Make it more explicit. Yeah. What are your best recommendations for looking into sources on Brigham Young?

Dan: The Leonard Arrington book on Brigham Young is a very good one. I’ve recommended, and this may surprise some, some of you have seen me recommend it before, I really loved the book Brother Brigham by Eugene England, which gives a really affectionate personal portrait of him, I think in a way that a lot of members of the Church, even, aren’t familiar with.

Now, some will know that Gene was liberal in politics and so on and so forth. But he loved Brigham Young. And I just found out by interviewing a couple of historians within the past few months for this, Ron Esplin in particular, “Oh, yeah. We helped Gene with that. We supplied material for him.” So it’s a very solidly based historical book. And you’ll come away, I think, as I did, loving Brigham Young as Gene did.

Brigham Young Bashing

Scott: Well, I think there’s a new fashion out there to bash Brigham Young. “Brigham Young poisoned Joseph Smith so he could take over.” I think it’s kind of interesting that he did that when he was in a different country at the time (laughter).

Dan: Yes. Brigham was very, very skillful (laughter). No, that one, I have to admit, that’s one of the things that’s really gotten me going, is the view, and I’ve heard it from members of the Church, believe it or not, that Brigham Young presided over the plot to kill Joseph and Hyrum. And his agents, since he wasn’t there, were John Taylor and Willard Richards.

I’m sorry. Someone approached me on Facebook, oh, probably a couple of years ago, and wanted to know what I thought of that theory. And I said that my response was [the name of the fellow who did it], I said, I just regret that he can’t be excommunicated a second time (laughter). And he saw what I’d written and went ballistic.

Denounce Slavery

Scott: So as a final thought, do you denounce slavery?

Dan: Do I denounce slavery? I better because I know that some of the people who watch me will be announcing that I did a defense of slavery at FAIR. No, obviously I don’t believe in slavery. I think it’s immoral. Humans don’t have a right to own other human beings, but these other pre-modern forms of labor contract, you know, they worked for a while. They were not bad.

I mean, someone told me just the other day, her great, great, great whatever grandmother had wanted to come to Zion but didn’t have the money, sold herself as an indentured servant for six years. Came over, the person paid her passage, she paid him off for six years, and then went off and got married and lived happily thereafter.

But by the standards of the day, you get to Utah. Utah couldn’t purchase the freedom of slavery. It was a cash poor economy. All you could barter with was labor, really. We didn’t have money out here in 1852 or 1847. People paid with labor and that’s the way they did it. We don’t do that now. And I’m glad we don’t have indentured servitude. But by the standards of the day, it was not an inhumane way of doing things, provided the master was reasonable.

But then, remember, under the law in Utah, an abused servant could sue. There’s at least one case that I know of where the suit was successful and the court freed him. The court said, you know, the bond between you and your master is dissolved. You’re free to go.

Scott: Thank you so much for your time. We really appreciate you as always. And I got several people thanking you for your talk. Thanks, Dan.

TOPICS

Brigham Young

Race

Slavery

Servitude