Introduction

Josh Coates: Okay. Hi. My name is Josh. I studied computer science at UC Berkeley about 30 years ago, and I’ve been in the tech industry for a long time. But the last four years, I’ve been full time at the B.H. Roberts Foundation. Today we’re going to do a little bit of math.

The Questions

All right, so questions:

All right, so questions:

- Are the golden plates physically possible?

- If so, what size plates?

- How thick?

- Made of what kind of material?

- Could the entire Book of Mormon fit on the plates?

- How large of text, how many characters?

I think that these are not unsolvable problems.

This is About Math

Actually, the math is embarrassingly easy, it turns out. I mean, as far as arithmetic. Someone in high school could do the math required to solve these questions.

Here’s the thing, though. There’s Thomas Aquinas asking us how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. So none of this stuff actually matters. But, if you can solve some problems, you might as well solve them.

Here’s the thing, though. There’s Thomas Aquinas asking us how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. So none of this stuff actually matters. But, if you can solve some problems, you might as well solve them.

Influencers’ Criticisms

One of the reasons I was motivated to do the math is because this seems to come up often, and especially over the last year, a couple of specific influencers on the internet that talk about religion often, brought these up. We’ll just watch a quick clip of them.

“Basically, it’s a different language that we’re talking about here. But if that is the kind of information density that we tend to find in these sort of symbolic languages, it is difficult to imagine how somebody would take 270,000 words and fit them onto golden plates that, like, you know, but with sort of the size described. It seems like you have to have, like, entire paragraphs represented by like singular symbols.”

“This is a model of the golden plates, two thirds of which were sealed and allegedly couldn’t be opened. That means there were at most 40 plates each, six by eight inches, that were supposed to have contained information present in the 270,000 English words of the Book of Mormon. In order to contain that information, every character on one of these plates would have to represent 80 words.”

Okay, I’m sure those guys are really bright people.

Everything they said was wrong. So I’m just going to get to the summary here, and then I’m just going to show you how to work through some of the math and some of the research that I’ve done on this.

The Weight of the Plates

Can a bunch of plates made of gold alloy be about golden-plate-size and weigh less than 60 pounds?

Can a bunch of plates made of gold alloy be about golden-plate-size and weigh less than 60 pounds?

The answer is yes. Absolutely. 100%. Unequivocally yes. The math, the physics. This is the answer to the question. And it’s not an opinion. It’s just simple math.

Could the Plates Hold Enough Writing?

Next, can you put enough writing on the valid set of physical plates to hold the entire text of the Book of Mormon? Notice the asterisk, including the 116 pages. I’ll talk more about what that means exactly.

Next, can you put enough writing on the valid set of physical plates to hold the entire text of the Book of Mormon? Notice the asterisk, including the 116 pages. I’ll talk more about what that means exactly.

The answer to this is yes. Again, not speculation on an opinion. This is just simple math. The answer is absolutely, 100% yes.

Consistency with Historical Records

Can you do all of this and have it be consistent with the 19th century historical record reported descriptions?

Can you do all of this and have it be consistent with the 19th century historical record reported descriptions?

Yes, absolutely.

Can you do all of that and have it be consistent with the writing size and material found in ancient artifacts from the Old World and the New World?

Can you do all of that and have it be consistent with the writing size and material found in ancient artifacts from the Old World and the New World?

Yes, absolutely.

What I’m going to share with you is how you arrive at this.

If you actually want all the gory details, there’s the paper. It’s like 60 pages. So, if you want some bedtime reading, it’s available on the Interpreter Foundation‘s website. But this is the abbreviated, the abridged version of the paper.

The Two Components

So, how do you do this?

So, how do you do this?

We have two components that we have to work with, two sets of data. The first one is historical statements about the physical properties of the plates. And those are fuzzy, right?

Any time you deal with a statement from a person, it’s always going to be inexact, imprecise. So, that’s just what we have to work with. That’s the data set.

On the other hand, we have math and physics, which is not fuzzy. So we can rely on that. But we have to deal with both of these to come up with the answers to these questions.

So, there’s about 60 or so historical sources of the Book of Mormon, and there are varying qualities. Some are first hand eyewitness accounts, others of them are second hand or third hand. Some of them are contemporary, some of them are many decades late. So we have to deal with a lot of different types of witness statements.

How Does Math & Physics Work?

The Math

So let’s talk about how the math works first, so you understand kind of how to do this.

- Part one: figure out which configurations of the plates are physically possible.

- Part two: figure out which of those configurations the Book of Mormon could fit on.

Let’s do part one first. This is just an example of how if you sat down with a notepad and you decided, ‘hey, I think I want to do this myself’. This is how everyone who’s ever done this – and there’s been researchers over the last, well over 100 years, that have kind of wondered about this.

And this is how they basically do it.

And this is how they basically do it.

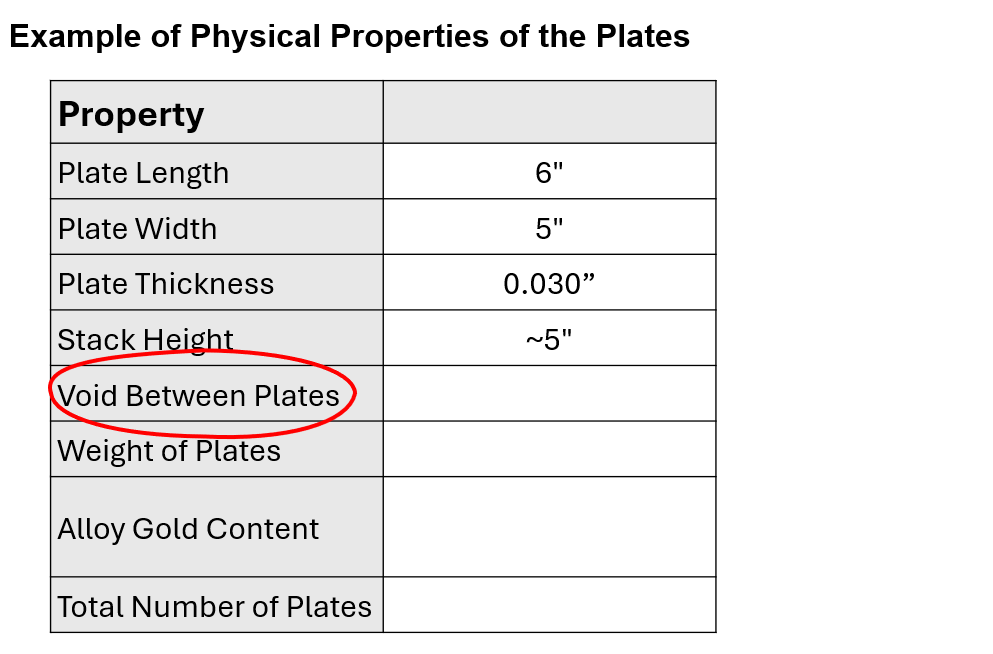

They’ll say, well, what’s a plate length? I don’t know, say they were six inches long, say they were five inches wide, maybe they were 30 thousandths of an inch thick. You know, these are just guesses, right? Maybe the stack of the plates was somewhere around five inches high. The void between the plates. Well, what does that mean, exactly?

Void Between Plates

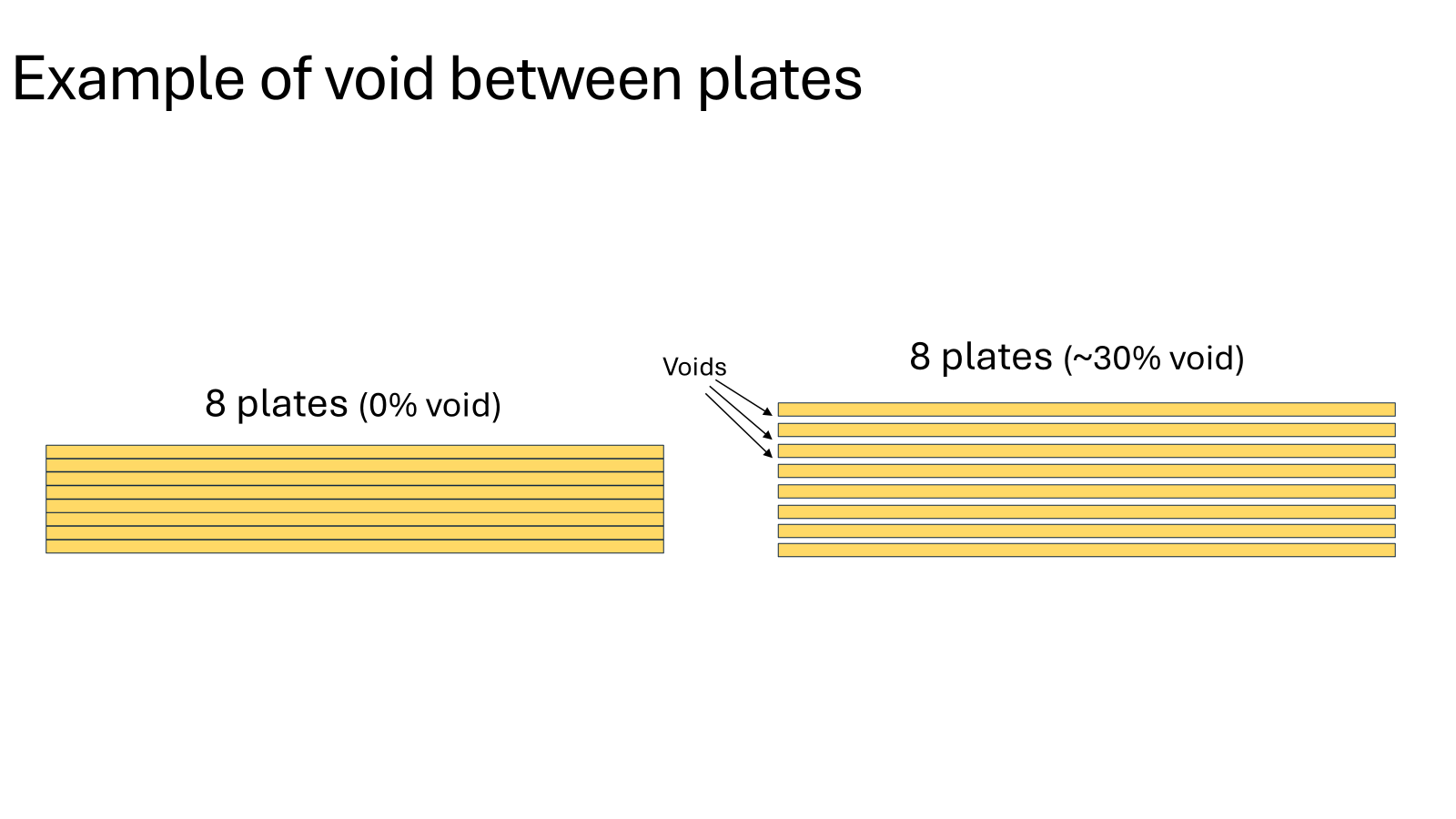

Just really quick, if you’re not familiar. This is a picture of eight plates. There’s zero void there. They’re exactly on top of each other. That’s not how actual physical plates work. There’s what we call ‘voids’ between the plates because they can’t be perfectly flat. So this is a pictorial example of, say, 30% void.

Just really quick, if you’re not familiar. This is a picture of eight plates. There’s zero void there. They’re exactly on top of each other. That’s not how actual physical plates work. There’s what we call ‘voids’ between the plates because they can’t be perfectly flat. So this is a pictorial example of, say, 30% void.

So let’s say there’s a 30% void. Now the gold alloy content – gee, you know, what were the plates made of. We’ll talk more about what that is and how that works. But for now we’re just going to say they were 55% gold and 40% copper and 5% silver.

Let’s say they were 43 pounds. Witnesses said all sorts of things so I’m just going to make up 43 pounds. And I don’t know how many plates or total, but this is what we’re going to work with.

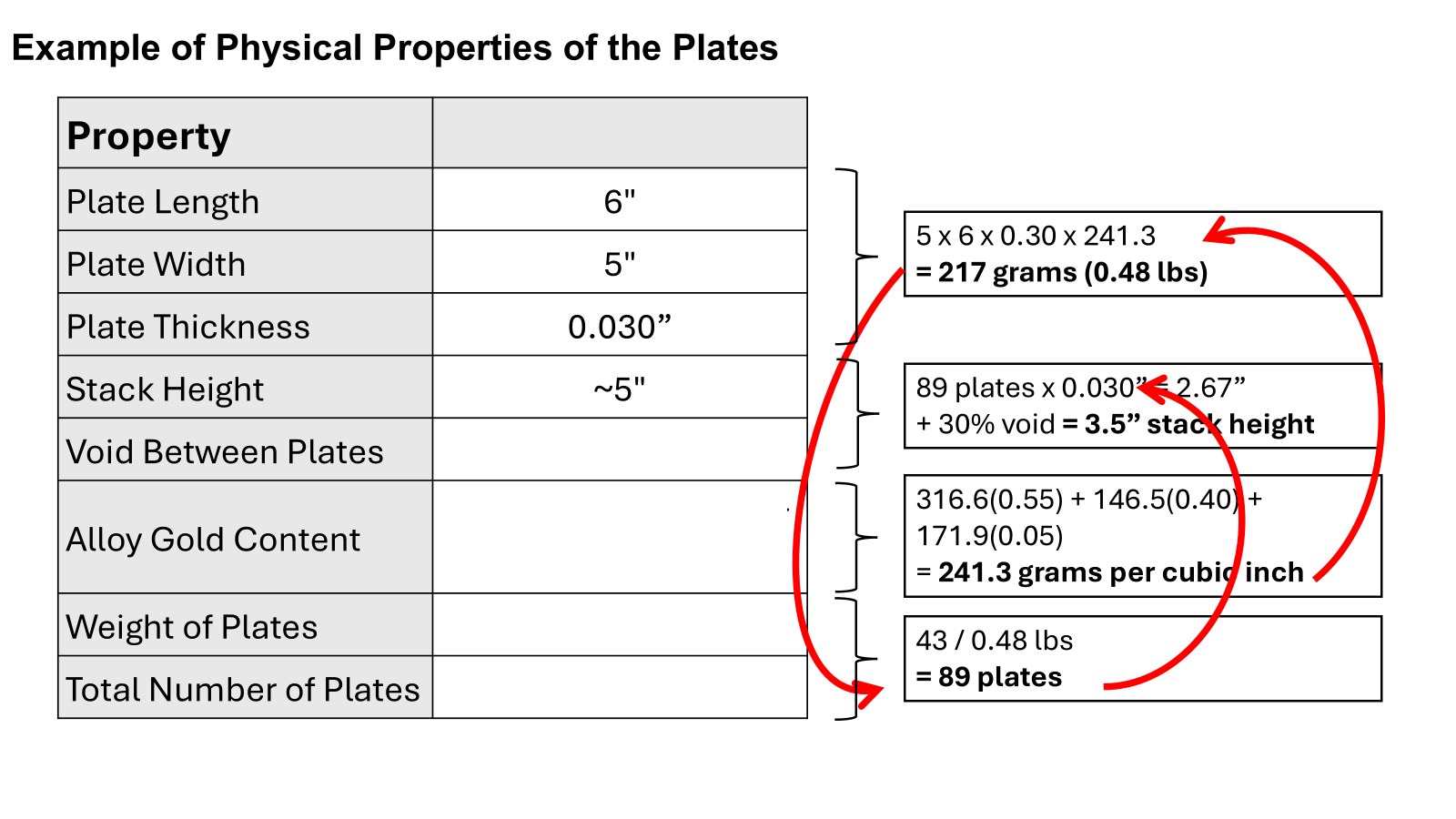

Physical Properties of the Plates

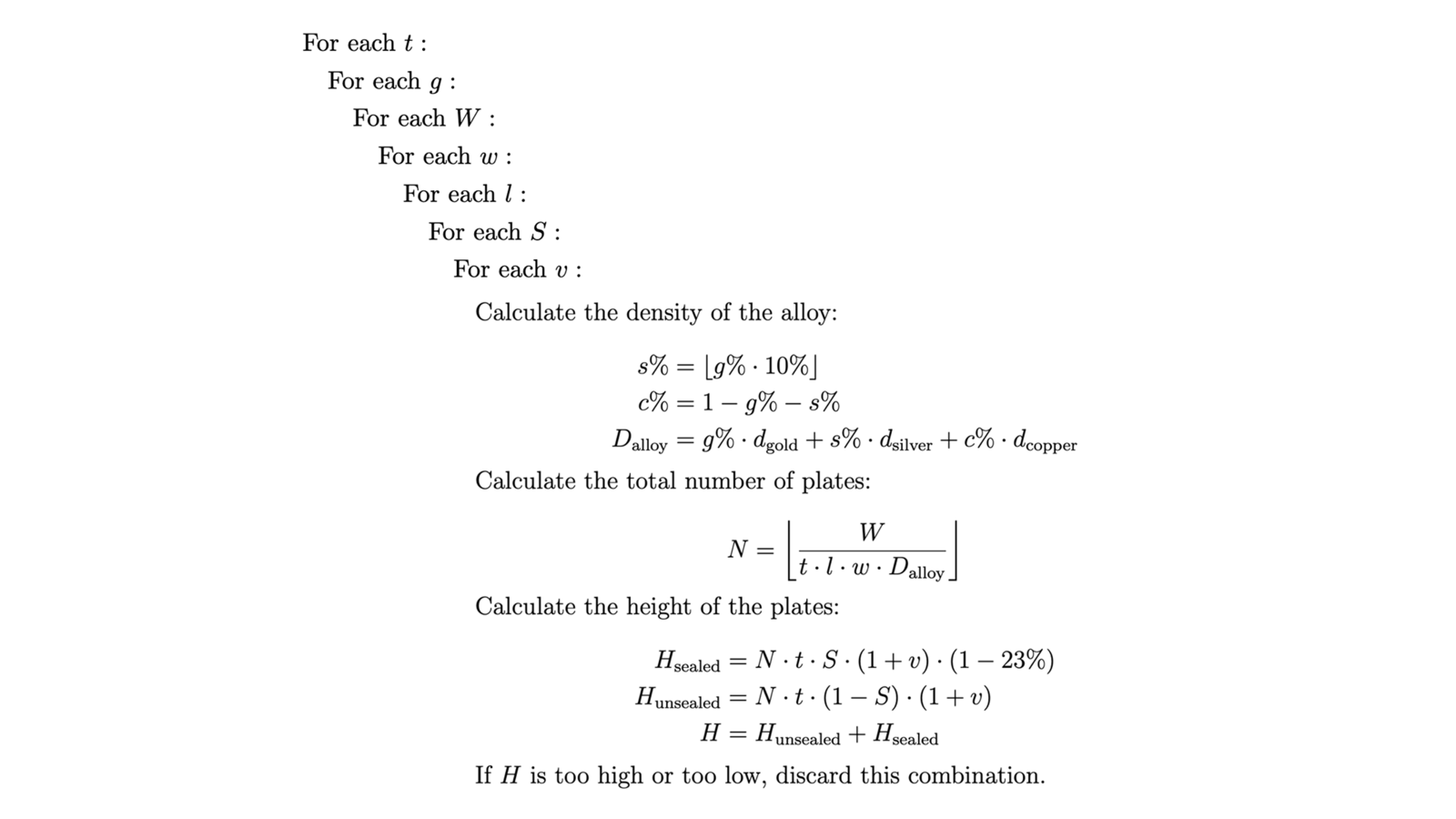

So, you write all this out and then you start doing simple math.

We know the density, the number of grams per cubic inch, because we know these elements and how much they weigh. Then we take that answer and we plug that into the dimensions of a single plate. Right?

That’s just basic, you know, length times width times height. And then after that, we take that and then we say, well, if there’s 43 pounds of this stuff, that means there’s about 89 plates.

Doing the Plate Math

And then we say, well, if 89 plates at 30,000th of an inch with a 30% void, that’s about 3.5 in high. So we just wrote this on the back of a napkin, and there’s our plates.

And then we say, well, if 89 plates at 30,000th of an inch with a 30% void, that’s about 3.5 in high. So we just wrote this on the back of a napkin, and there’s our plates.

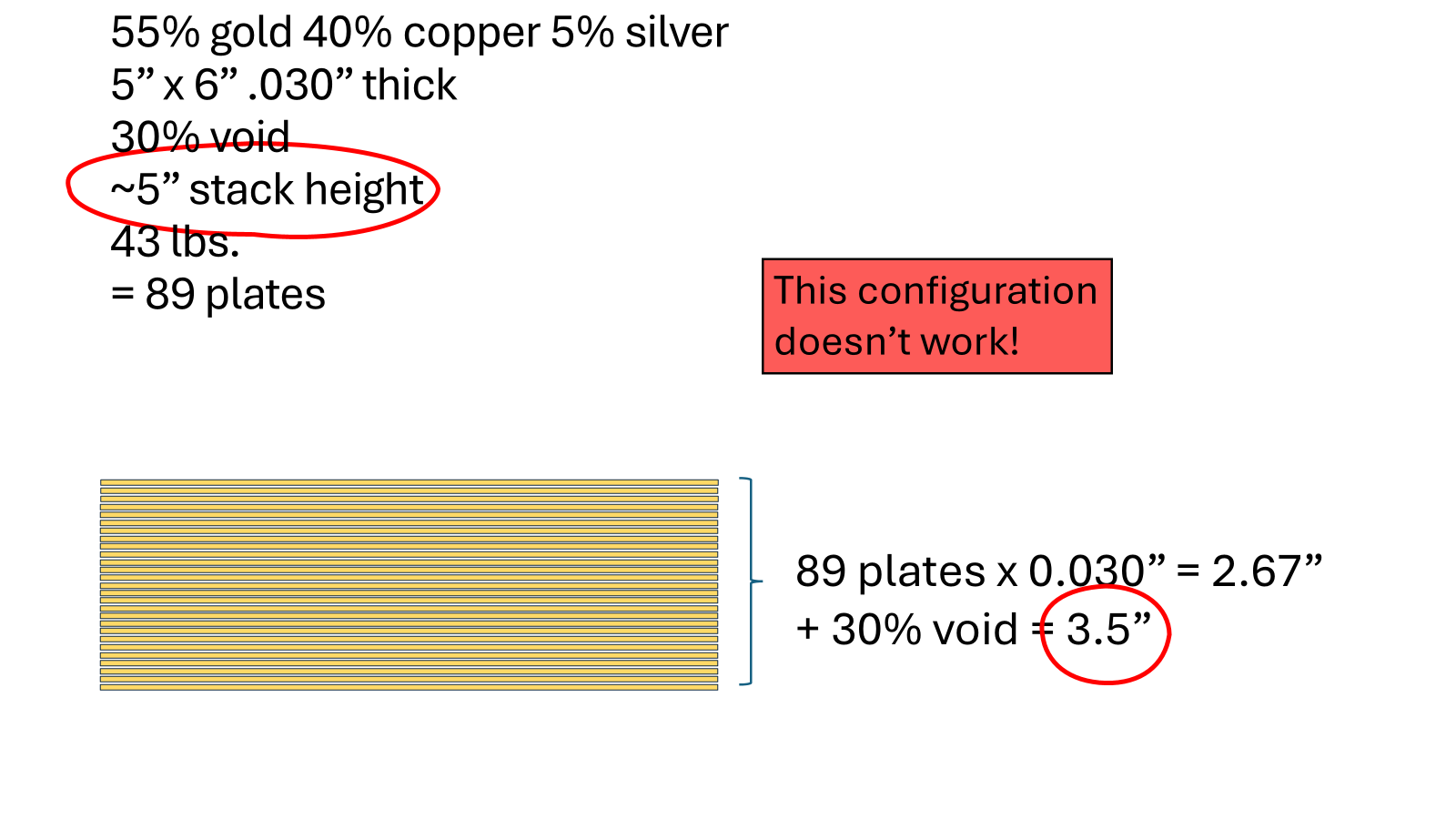

But there’s a problem. I said, well, this is going to be five inches high, but this math shows this is only 3.5 inches high.

But there’s a problem. I said, well, this is going to be five inches high, but this math shows this is only 3.5 inches high.

So we have an inconsistency, which means… the Church isn’t true anymore.

No, I’m just kidding. What you do is you go, ‘well, that didn’t work’, and you try a different one.

Changing the Variables

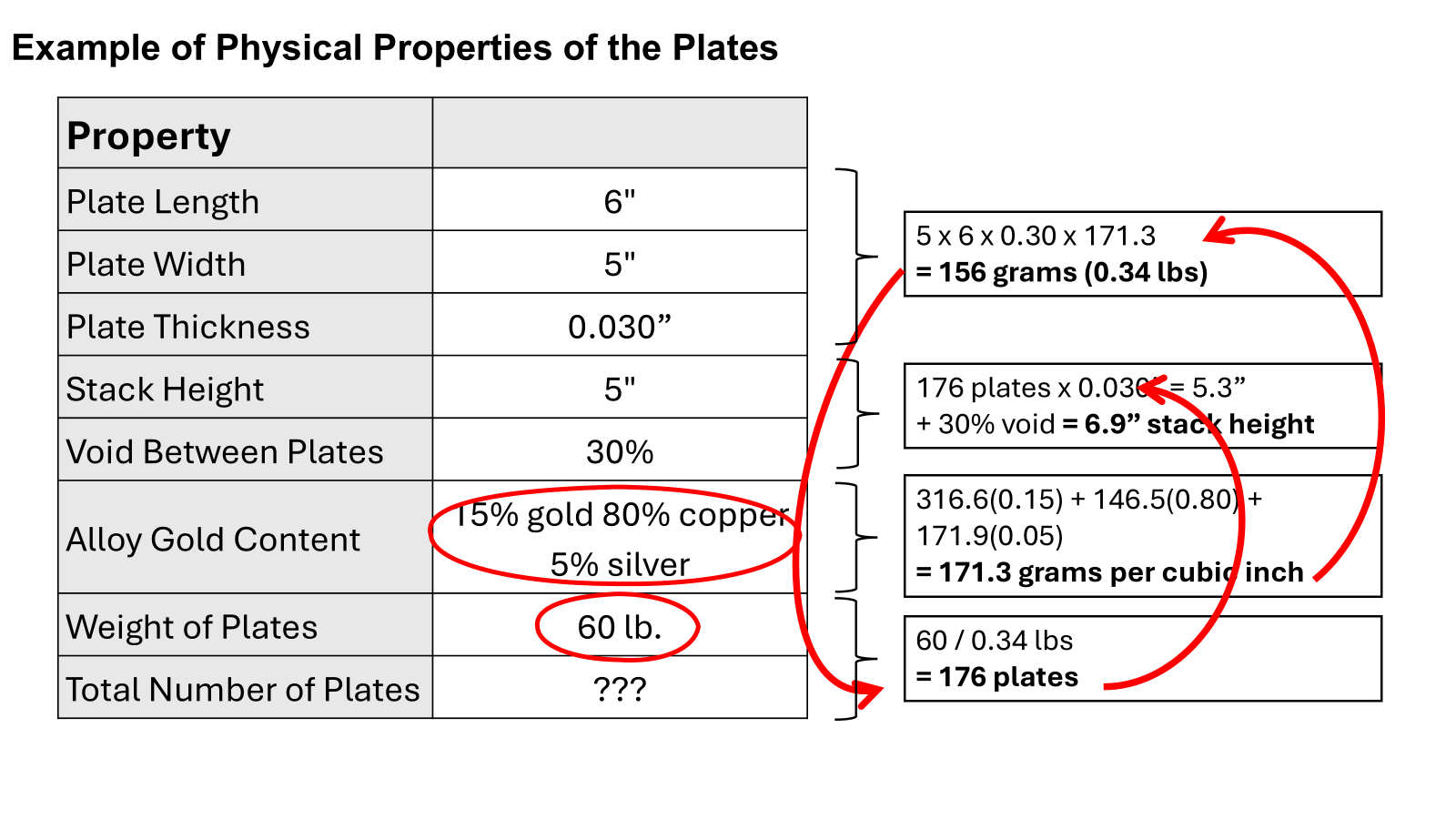

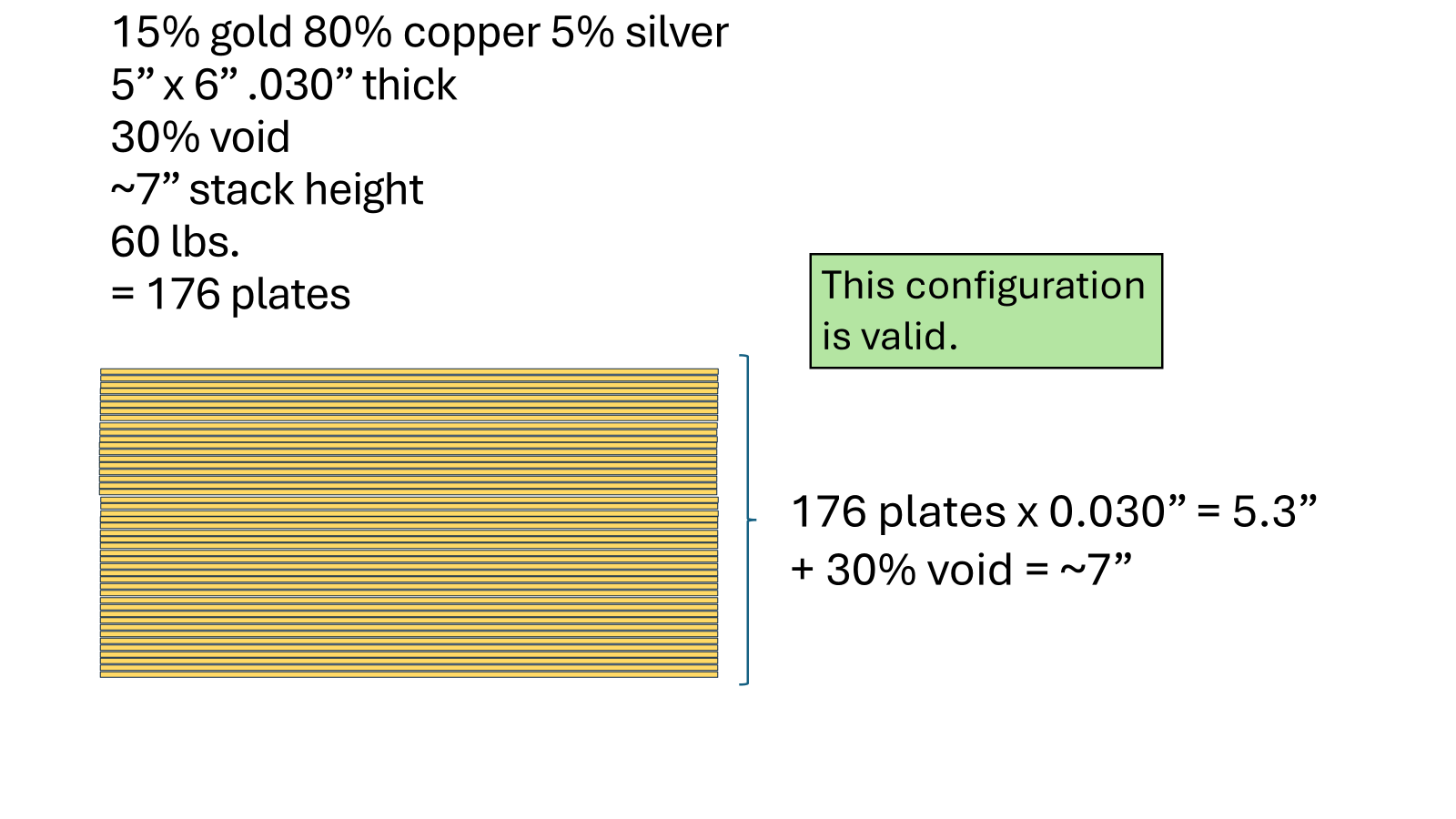

So this time we’re going to say, well, we’re going to change the alloy gold content. Let’s try 15% (gold), 80% copper, 5% silver. And then let’s say it weighs 60 pounds. We just try a couple different variables. We do some more math, we end up with… ‘oh my gosh, this works!’

So this time we’re going to say, well, we’re going to change the alloy gold content. Let’s try 15% (gold), 80% copper, 5% silver. And then let’s say it weighs 60 pounds. We just try a couple different variables. We do some more math, we end up with… ‘oh my gosh, this works!’

We found a valid configuration. Does this mean that the plates were like this? Well no, of course it doesn’t mean that. It just means we found a physical example of something that could work.

We found a valid configuration. Does this mean that the plates were like this? Well no, of course it doesn’t mean that. It just means we found a physical example of something that could work.

Could All the Words Fit on the Plates?

Can the Book of Mormon fit on this? Well, I don’t know. That’s a whole nother set of equations to go through. But this is just an example.

Combinatorics

Combinatorics

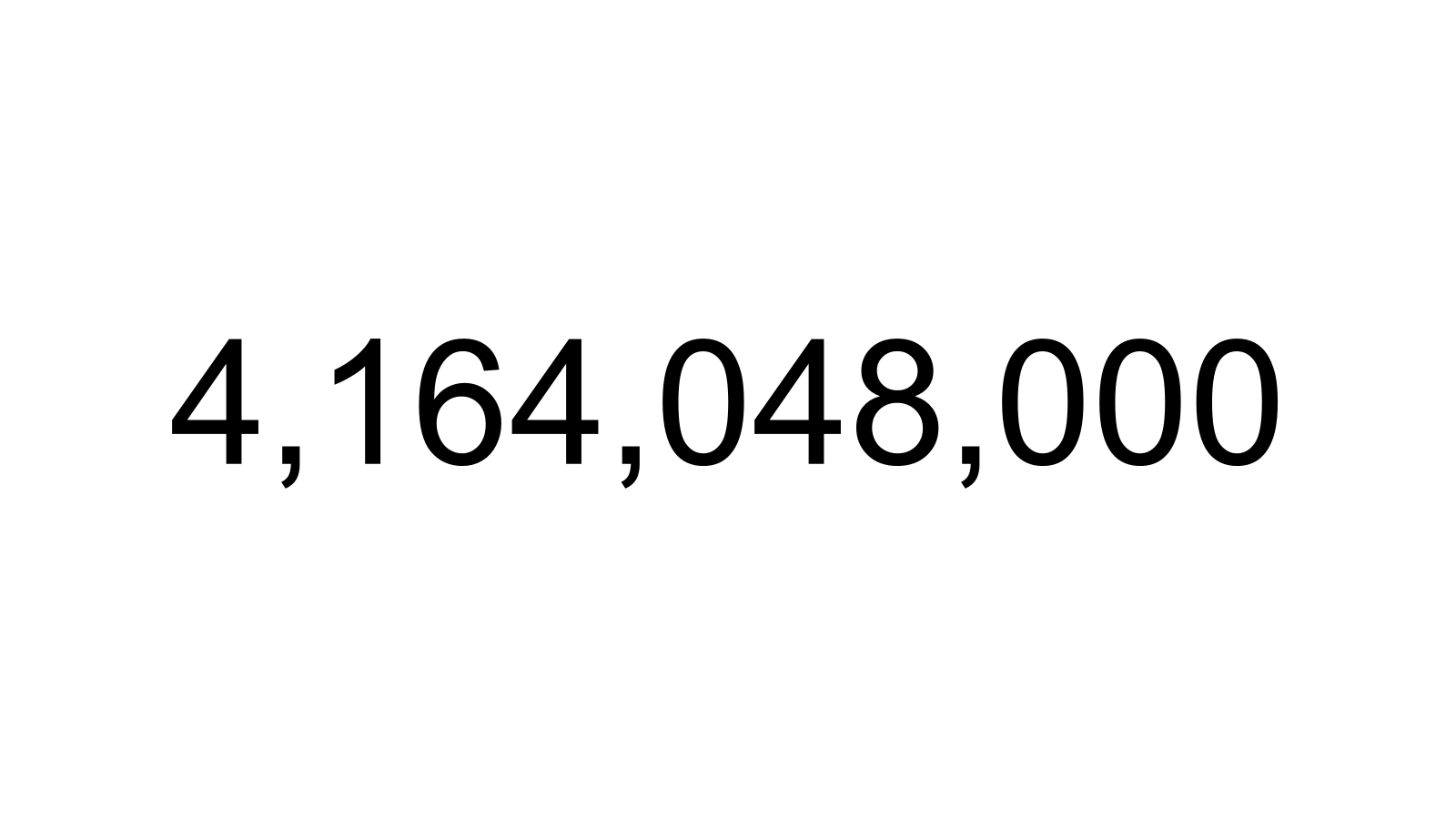

Now, what I’ve done is not just this. What I’ve done is something called combinatorics, which means we sort of do this, like 4 billion times, literally. You just take every possible permutation. This is not like a Monte Carlo simulation where you’re like, ‘hey, there’s a probability.’

No – we do every single possible configuration of all the variables.

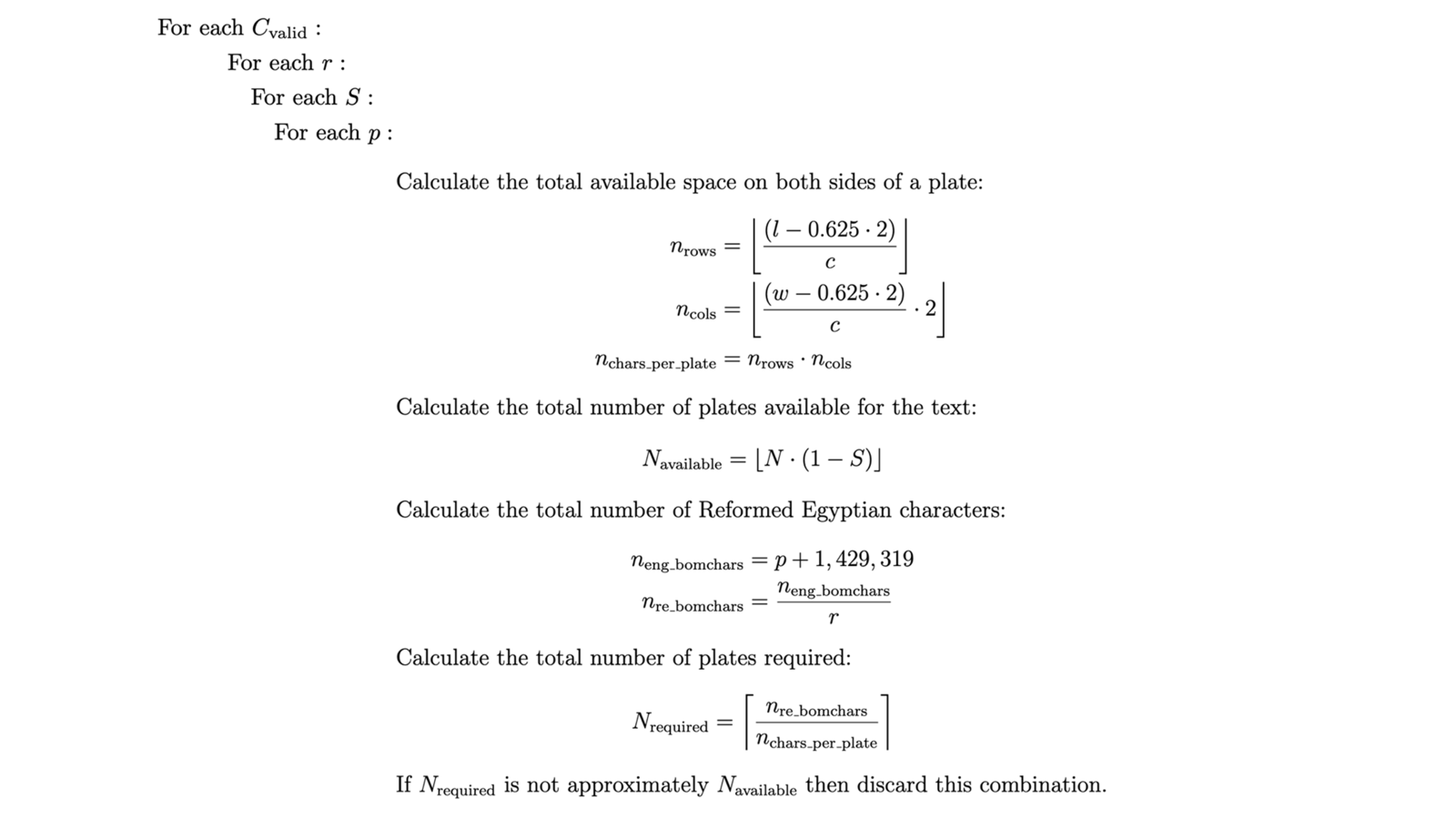

This is what the math looks like, the algorithm.

This is what the math looks like, the algorithm.

If you want to go home and program this yourself, knock yourself out. It’ll take you an afternoon. It’s not complicated.

Doing the actual computation on your computer or your laptop, depending on how clever you want to get with parallel processing, just in time compiling it, your computer might run for like 20 hours straight to do all the computations. But if you do some tricks, It can take about 20 minutes. So that’s combinatorics.

Let me go into the next level of detail of the actual variables that we have to use here. Because next we’ve got to deal with the documentary record. And we’ve got to ask ourselves:

- What do the witness statements and the news reports and the journal entries and the interviews say that the plates looked like physically?

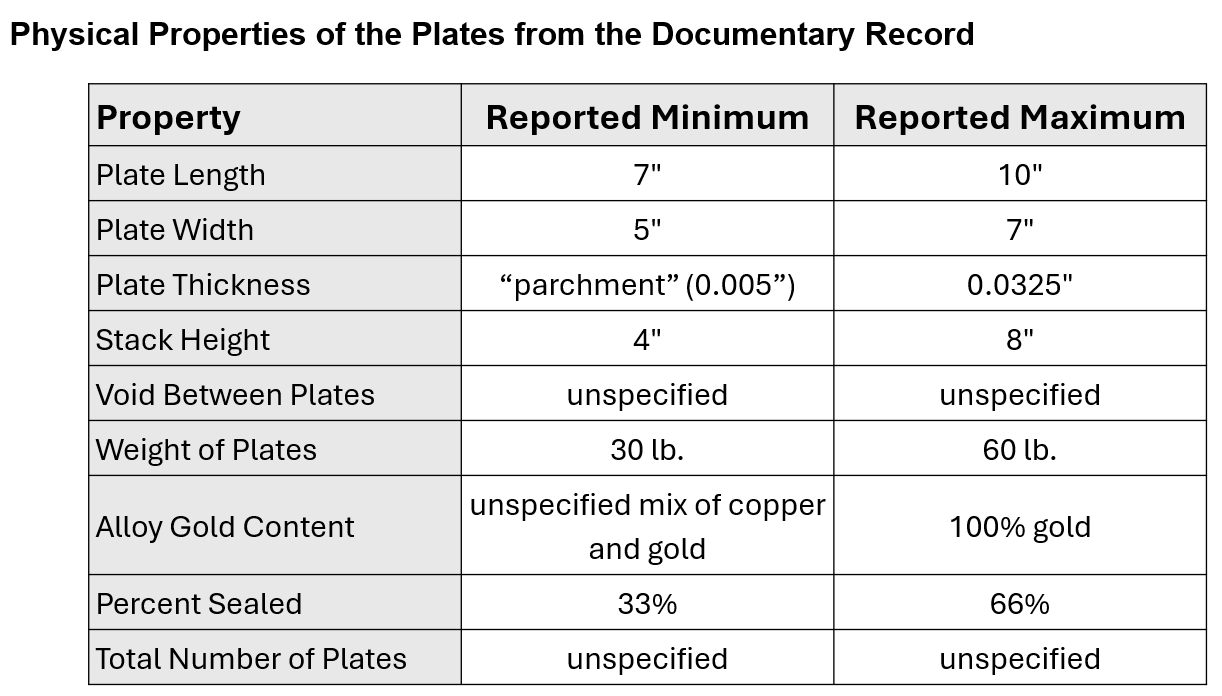

The Physical Properties from the Documentary Record

Length and Width

Length and Width

The minimum reporting was seven inches in length, and the maximum was ten inches.

Now, there’s a little asterix in this that I refer to in the paper. There were a few wild outliers on these minimums and maximums I’m about to share. The wild outliers are very unlikely to be true. So we’re just going to discard them because the vast majority fit in this narrow band.

These are the assumptions we’re making:

- Plate width five inches was the minimum,

- seven inches was the maximum reported plate width.

And again, this is all taken from the 60-70 witness statements that are available in the historical record.

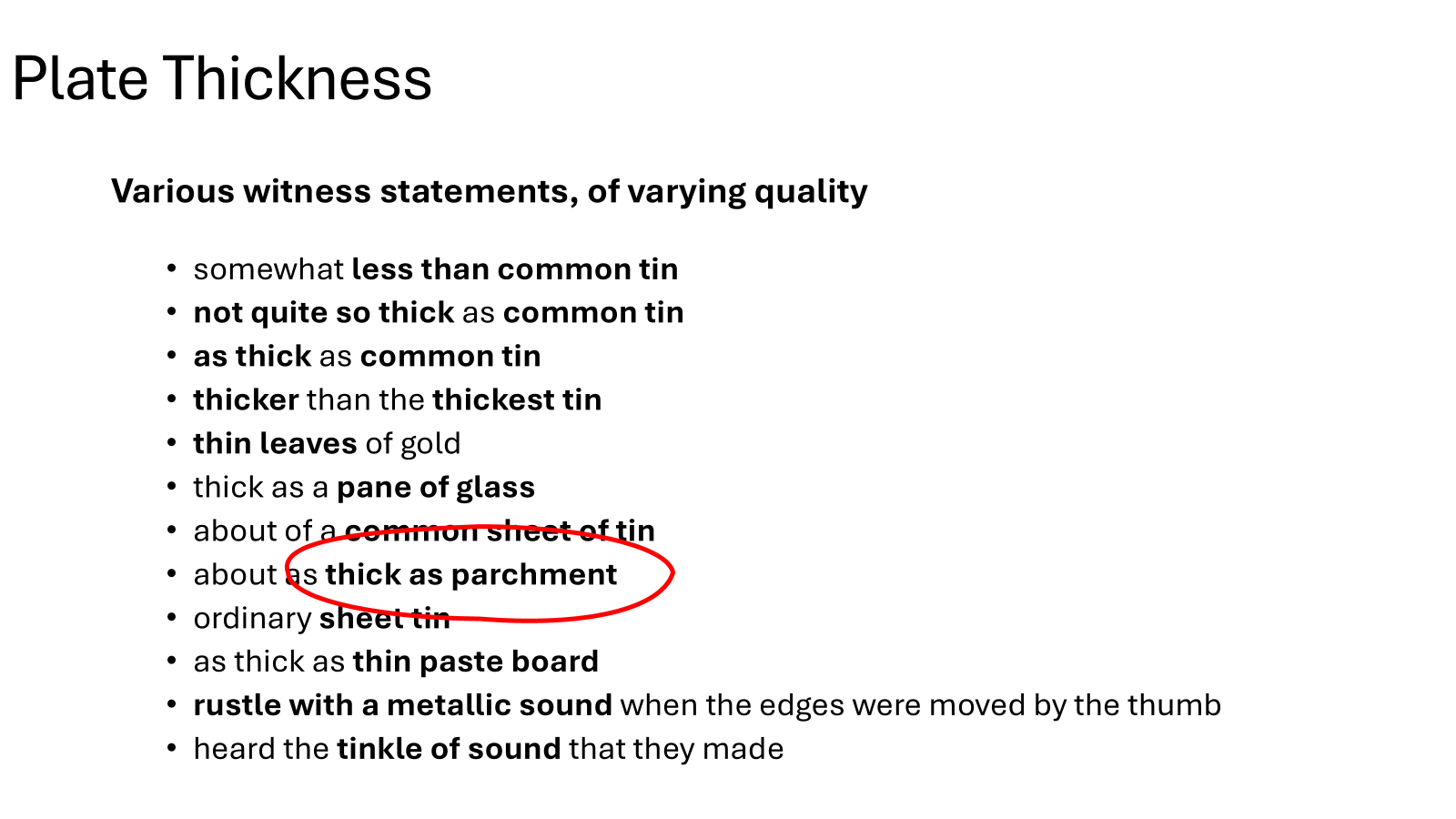

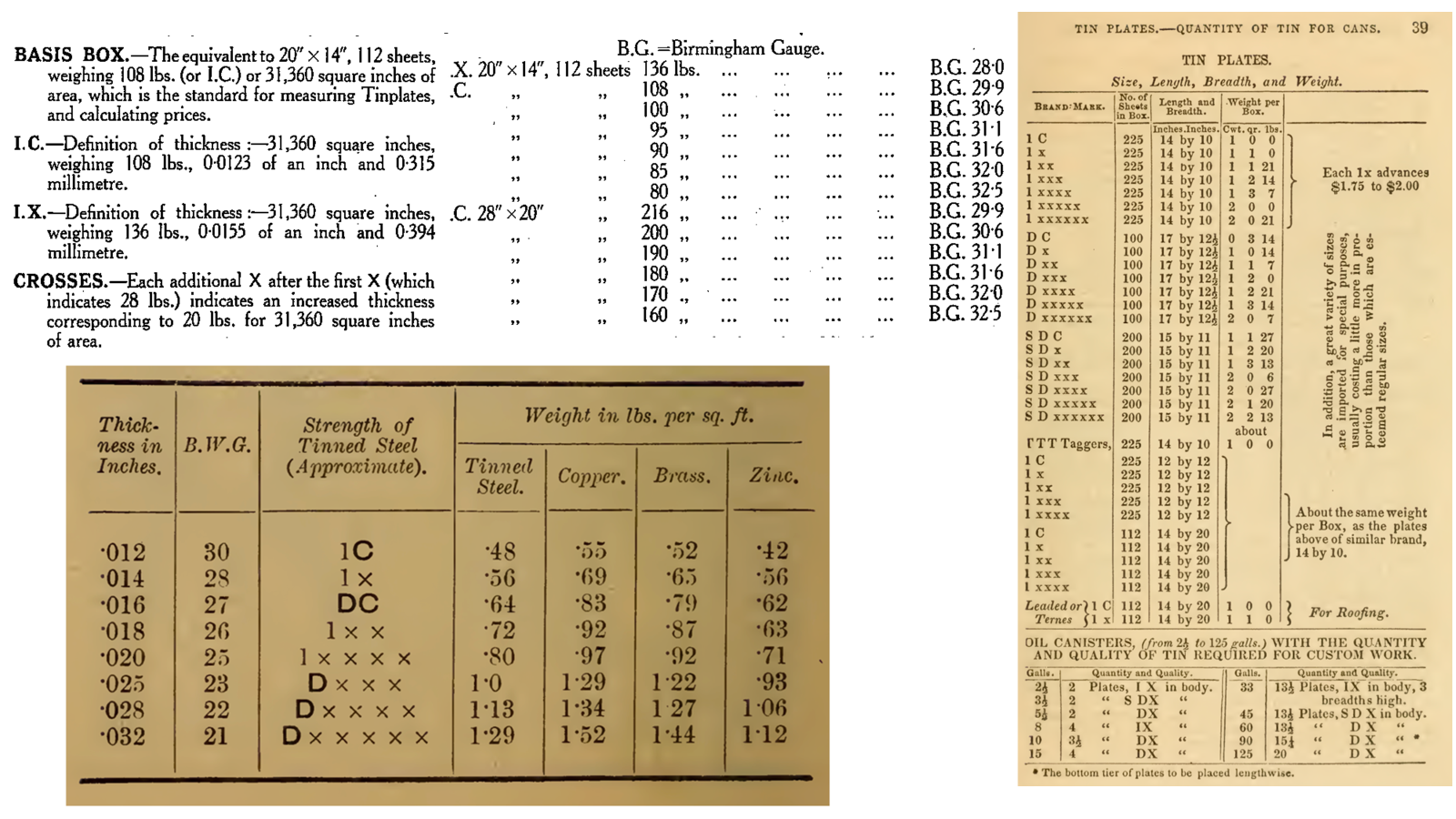

Plate Thickness

The minimum size thickness of the plates was parchment. Well, what does that mean? And the next one was 32 thousandths of an inch thick was a reported maximum.

Just really quick on thickness.

Here are some examples of plate thickness. There’s a lot of “tin” statements. We’ll talk about tin in a little bit–less than common tin, thicker than common tin, etc., etc. Thick as parchment. It was probably the thinnest one. So what was parchment in the 19th century?

About Parchment in the 1800s

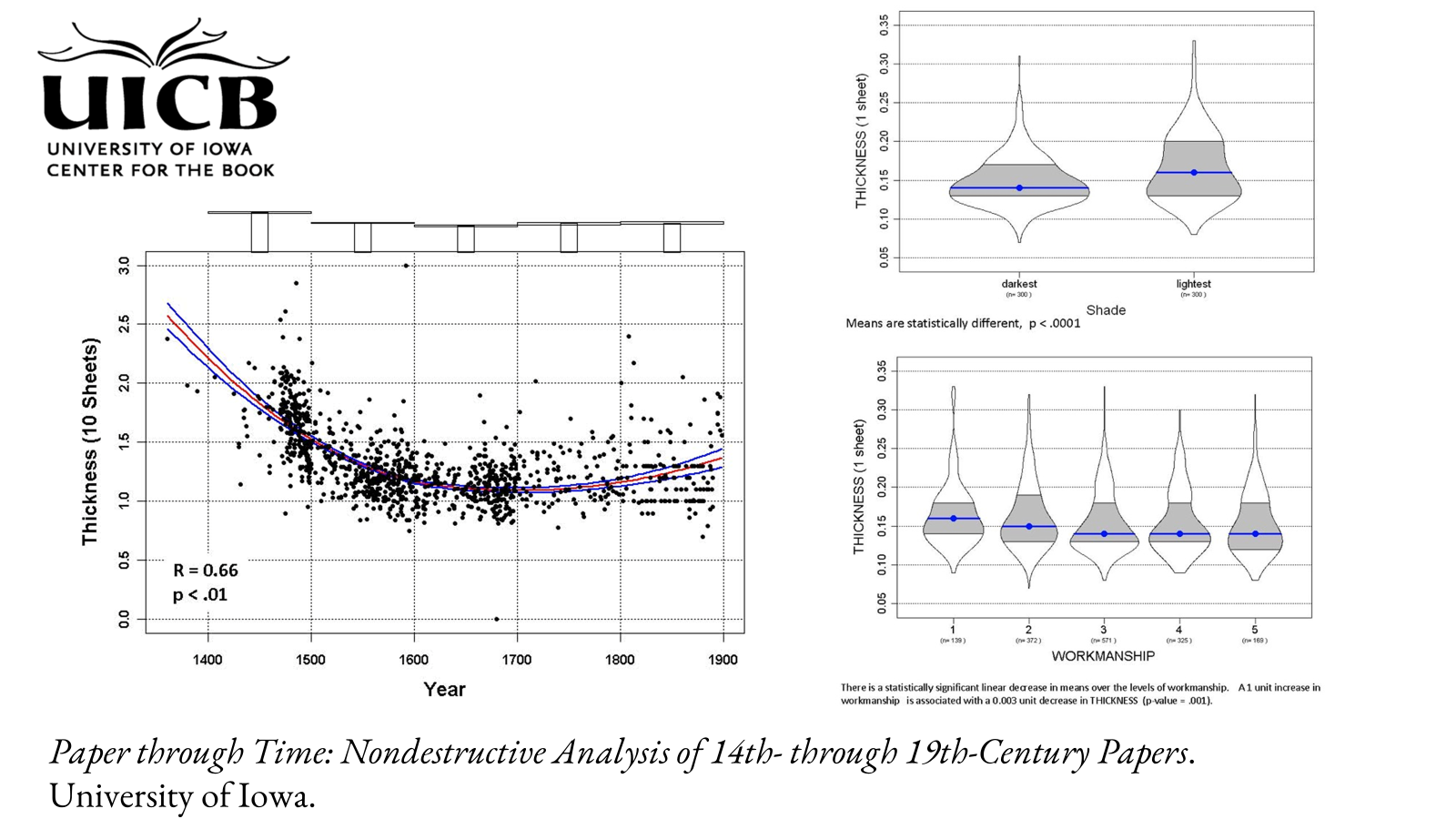

It turns out that the good folks at the University of Iowa, for some reason, felt compelled to measure 1500 books and the thickness of the paper. For the last 500 years, they have a collection of 1500 books, and they just measured all the paper. So I didn’t have to do that, which was really nice.

I can tell you what the typical American, mid 19th century, early 19th century page thickness was, and it was roughly, five thousandths of an inch. So that’s how we get that.

Stack Height

Next, stack height. Some people said four inches, five, six, seven; maximum was eight. So that’s our stack height range.

The Void Between the Plates

Next, the void between the plates. No one said anything about a void between the plates. I don’t know. Of course, they’re not going to say that as a terribly interesting thing to report on, on the plates.

So I just have to make something up, between 30 and 60%. I’ll talk more about experimental data on how we get to a good, good number there. But just bear with me for now.

Weight

The weight of the plates–between 30 and 60 pounds. This is basically the range that all the statements say. I think there was one person that said 20 pounds or somewhere near that. But we’re going with between 30 and 60.

Gold Content

Alloyed gold content. So…an unspecified mix of copper and gold was the minimum amount of gold, and then we had reports of 100% gold.

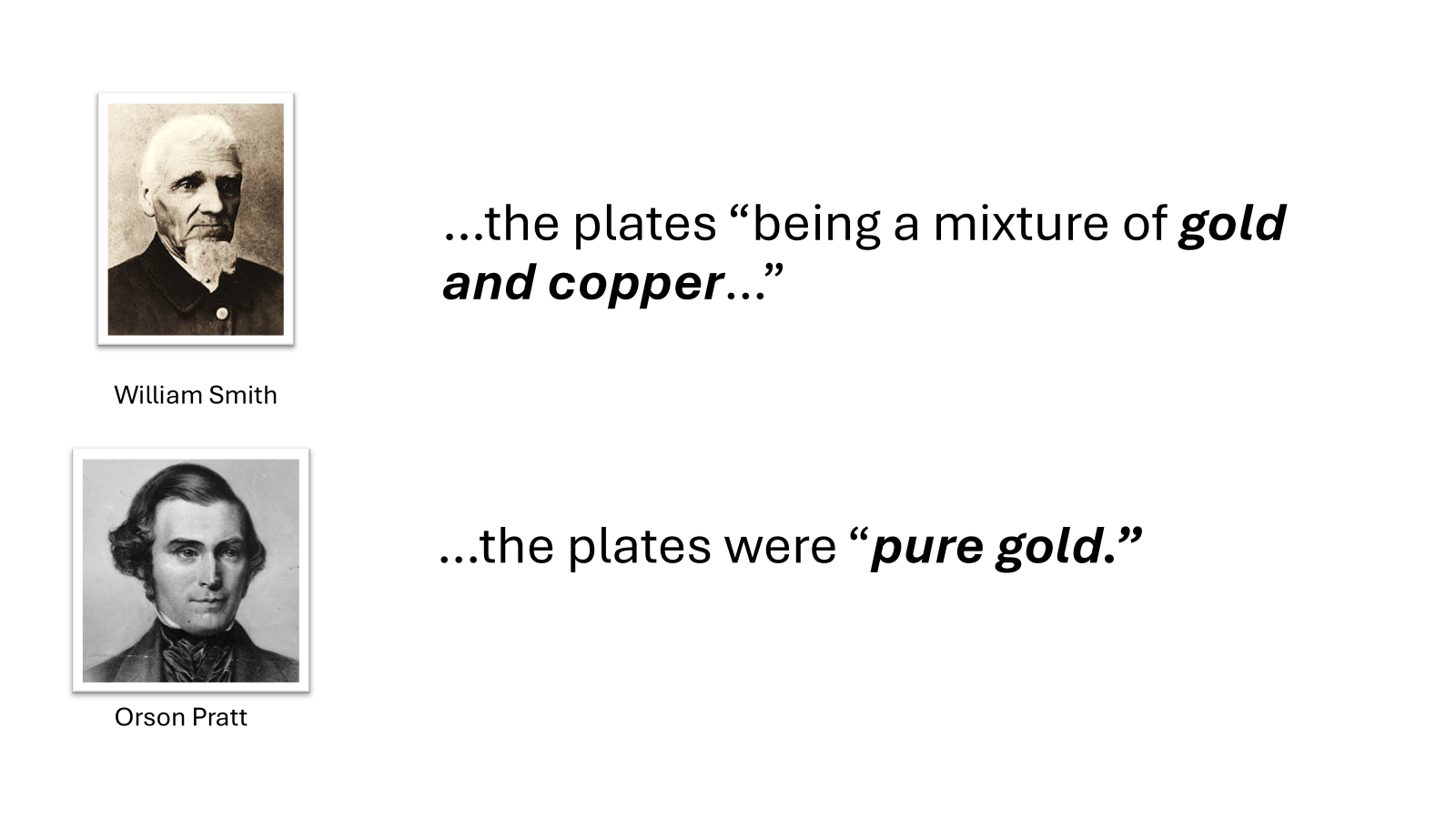

William Smith’s Description

So, just really quick on that. William Smith, many decades later said, ‘well, the plates were a mixture of gold and copper.’

We don’t know how he knew this. We knew he was some sort of a witness of the plates. He talked about hefting the plates. We don’t have any report near contemporary that said he actually saw the plate. But for whatever reason, William Smith said they were an alloy.

Orson Pratt’s Description

But then we have Orson Pratt say, ‘no, it’s totally pure gold’. So who knows?

But the good thing about this is we don’t actually care. We don’t care because we’re going to do all the numbers. We’re going to do every single type of alloy, every single type of weight, every single type of thickness.

We don’t have to figure out who’s right, because I don’t care who’s right. The only thing I care about is what are the minimums and maximums of the historical record.

What the Book of Mormon Says About the Plates

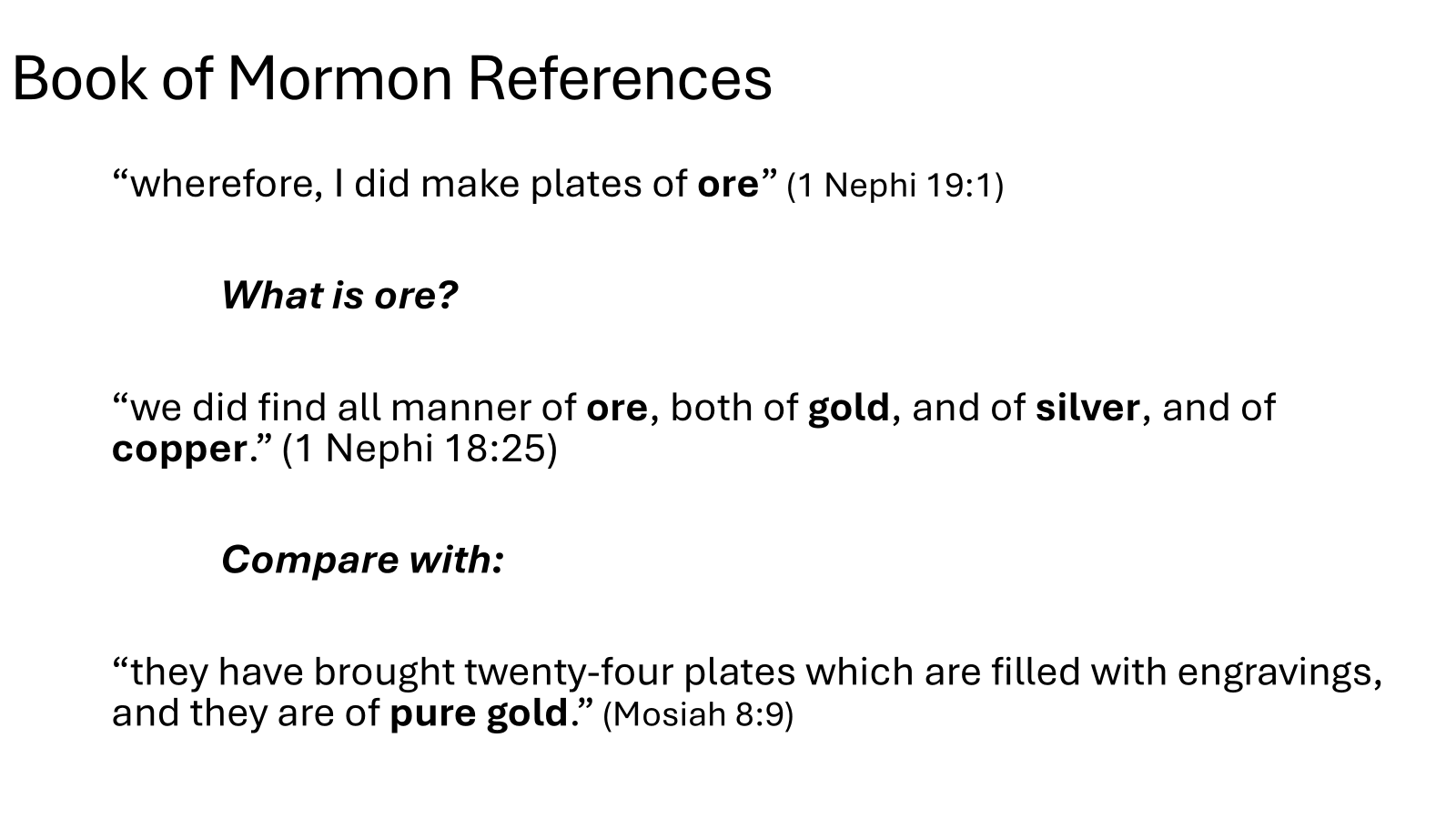

So let’s look at the Book of Mormon too, because that’s a source as well.

So let’s look at the Book of Mormon too, because that’s a source as well.

“Wherefore I did make plates of ore.” (1 Nephi 19:1)

So Nephi said they’re made of ore. Well, what’s “ore”? He mentions “ore” being gold, silver and copper. So there’s a vote for William Smith – an alloy. And then compare it also later in the Book of Mormon where we talk about plates of pure gold.

So it seems, and again, we’re guessing, but we don’t have to rely on these guesses, that there’s some differentiation between pure gold and an alloy in any case.

Historical Feasibility of Alloy

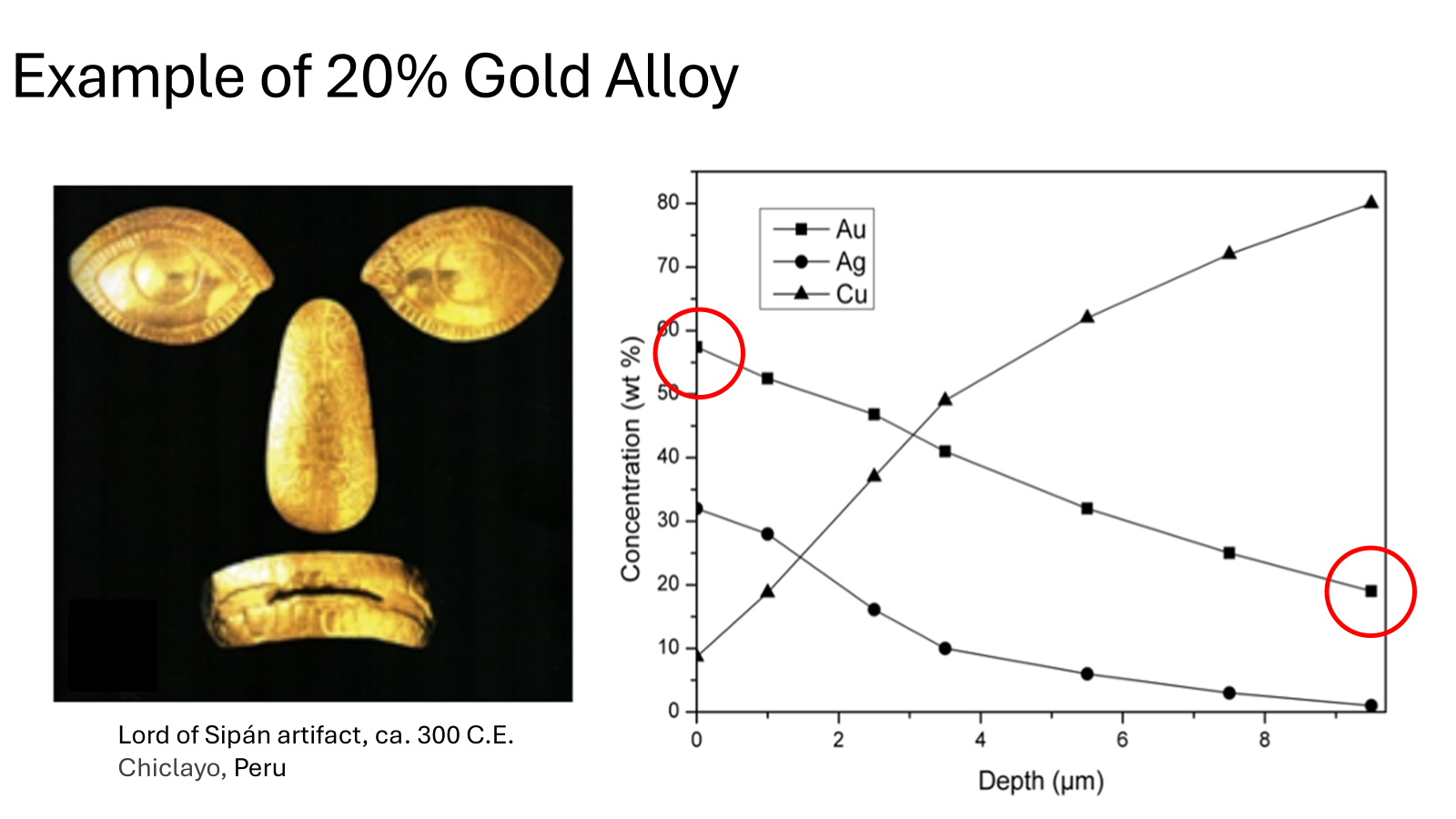

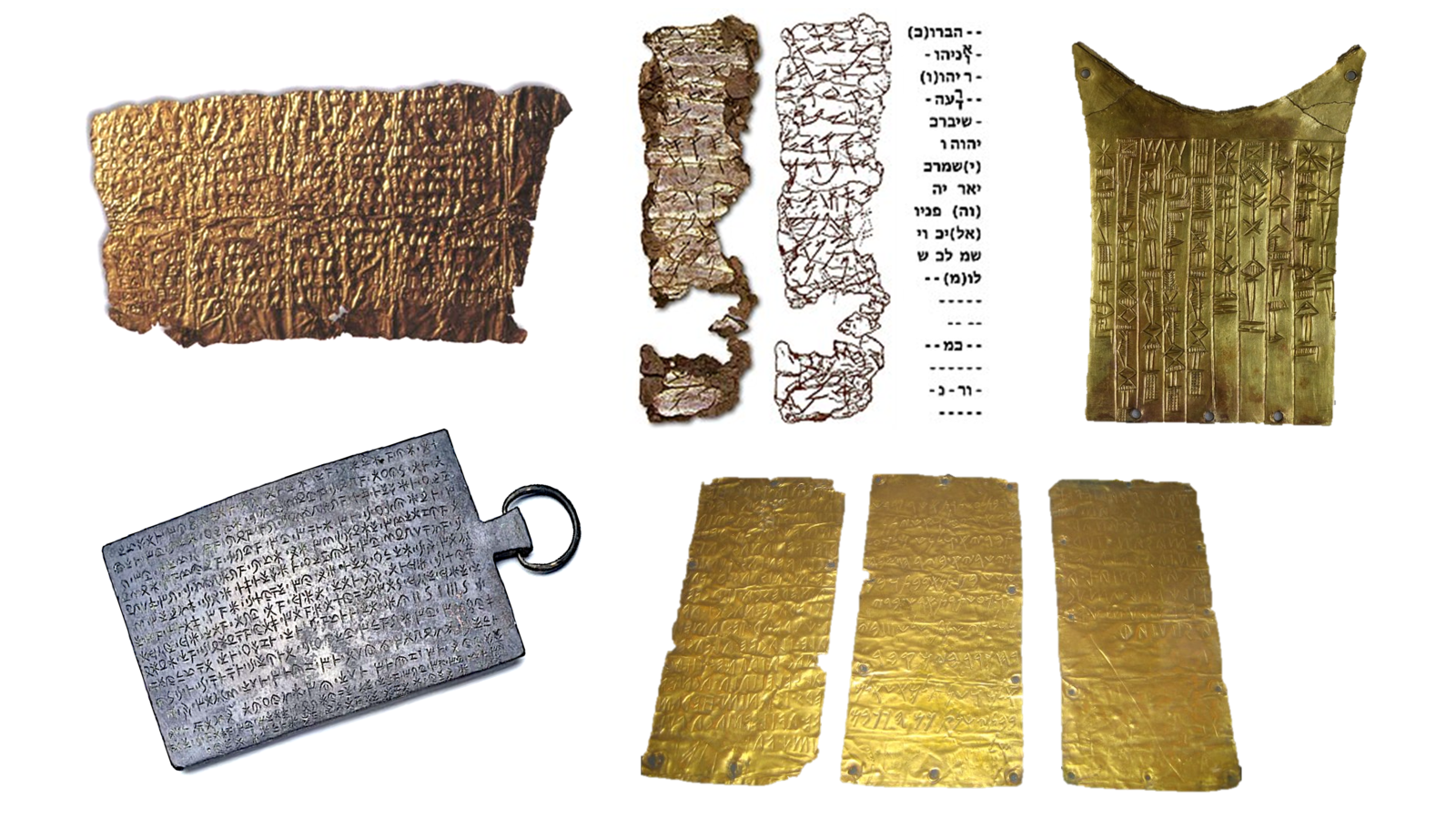

Oh, also this alloy concept, it’s in the old world. It’s in the new world. We have tumbaga, which is the New World name for it. But they had tumbaga in ancient Mesopotamia 2000 BC. And it looks like gold, but in fact, it’s significantly made of copper. So – Old World and New World.

Oh, also this alloy concept, it’s in the old world. It’s in the new world. We have tumbaga, which is the New World name for it. But they had tumbaga in ancient Mesopotamia 2000 BC. And it looks like gold, but in fact, it’s significantly made of copper. So – Old World and New World.

20% Gold Alloy

Here’s an example of 20% gold alloy. This is an artifact from Peru 300 A.D. And the surface of this is about 60% gold. So that’s somewhere, I don’t know, about 14 karat-ish or so.

Here’s an example of 20% gold alloy. This is an artifact from Peru 300 A.D. And the surface of this is about 60% gold. So that’s somewhere, I don’t know, about 14 karat-ish or so.

In fact, if you do XRF analysis, X-ray analysis, there’s actually only 20% gold in this artifact. But the surface is 14 karat, so, of course, this looks very gold; but in fact, it’s only 20% gold. So that’s how tumbaga works. That’s how this alloy works. We’ll talk a little bit more about that right here.

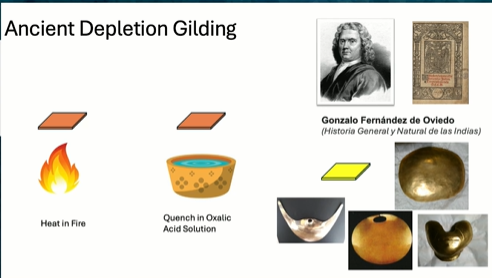

Ancient Depletion Gilding

This is called depletion gilding. So Oviedo, he observed what Mesoamericans did after the conquest of Mexico. If I recall correctly, he was in charge of some mining operations, and he was an administrator. And, he was really curious about how the ancients worked with their gold. And this is how depletion gilding works.

See that that kind of looks copper-ish? If you mix gold and copper and silver, it ends up looking pretty copper-ish.

What you do is you heat it up, and then you quench that piece of metal in oxalic acid. Oxalic acid comes from certain plants that are all over the Americas. So, what they would do is they’d chew up the plants and they’d spit into a bowl, and they would have a big bowl of acid-spit. And then they mixed water in there, and then they’d quench hot metal in it. If you do this enough times, you end up with a gold plating. This is how it works.

Different Stages of the Process

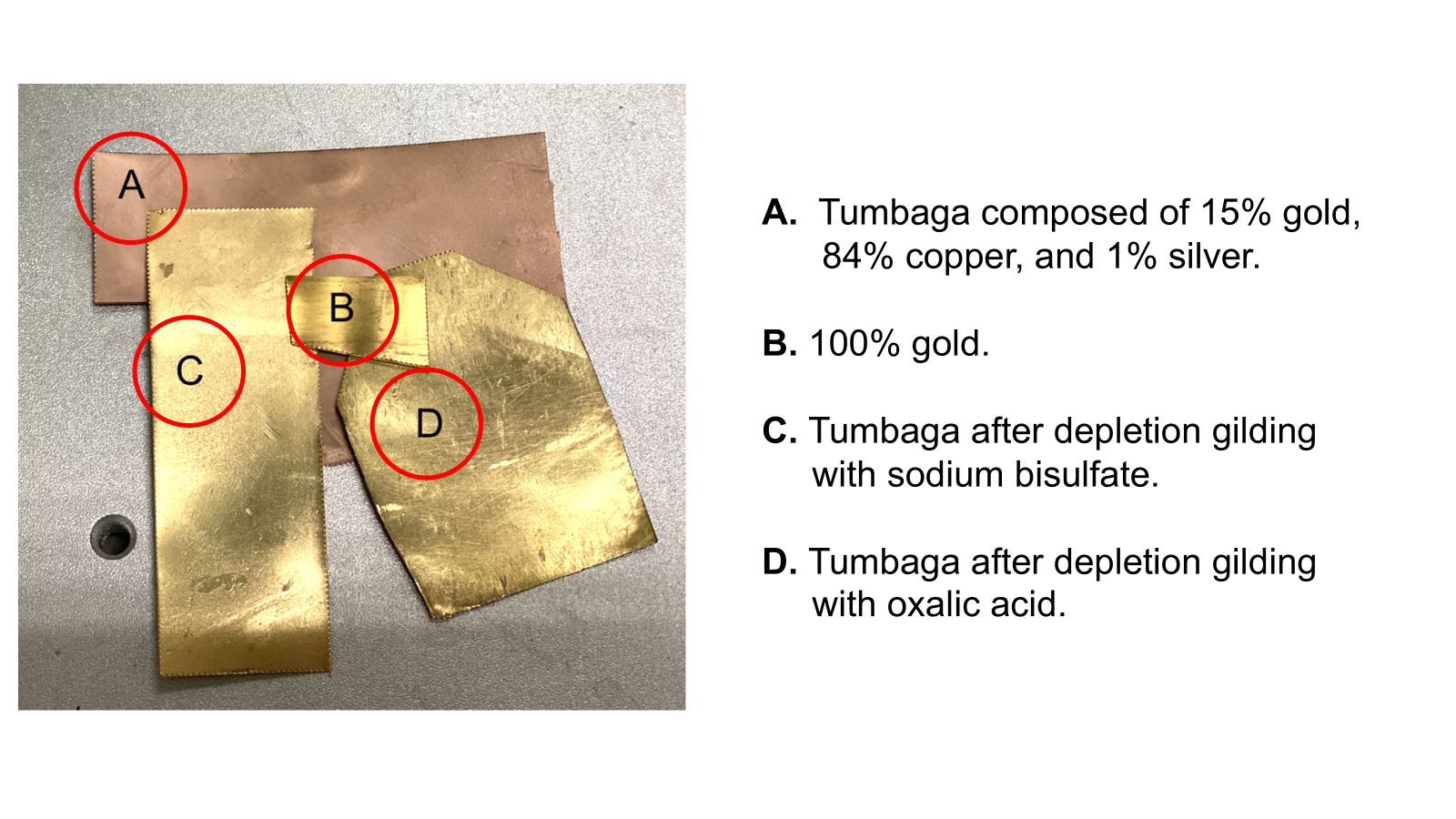

See this here:

See this here:

- That’s tumbaga. That’s 1584 1 tumbaga. It looks very copper-ish. Not very gold-ish.

- That’s pure gold. 100% gold.

- That’s tumbaga after depletion gilding with sodium bisulfate. You can deplete with lots of different types of acids.

- D is actually using literally oxalic acid.

As you can see B, C, and D look really gold don’t they? Whereas A, of course, doesn’t look gold at all. You’re going to learn so much about depletion gilding today. I know you really want to learn about this.

Gold Plating

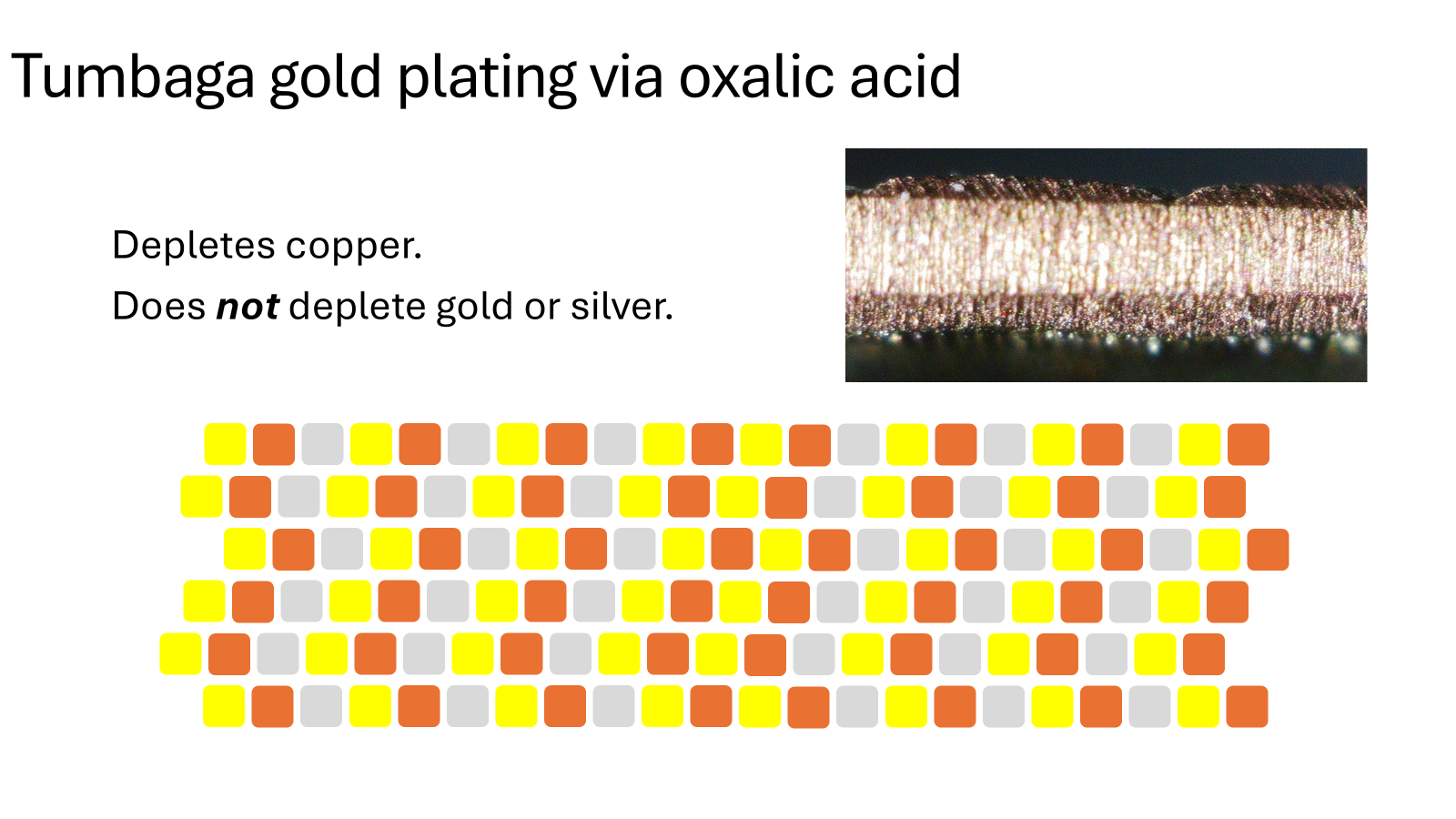

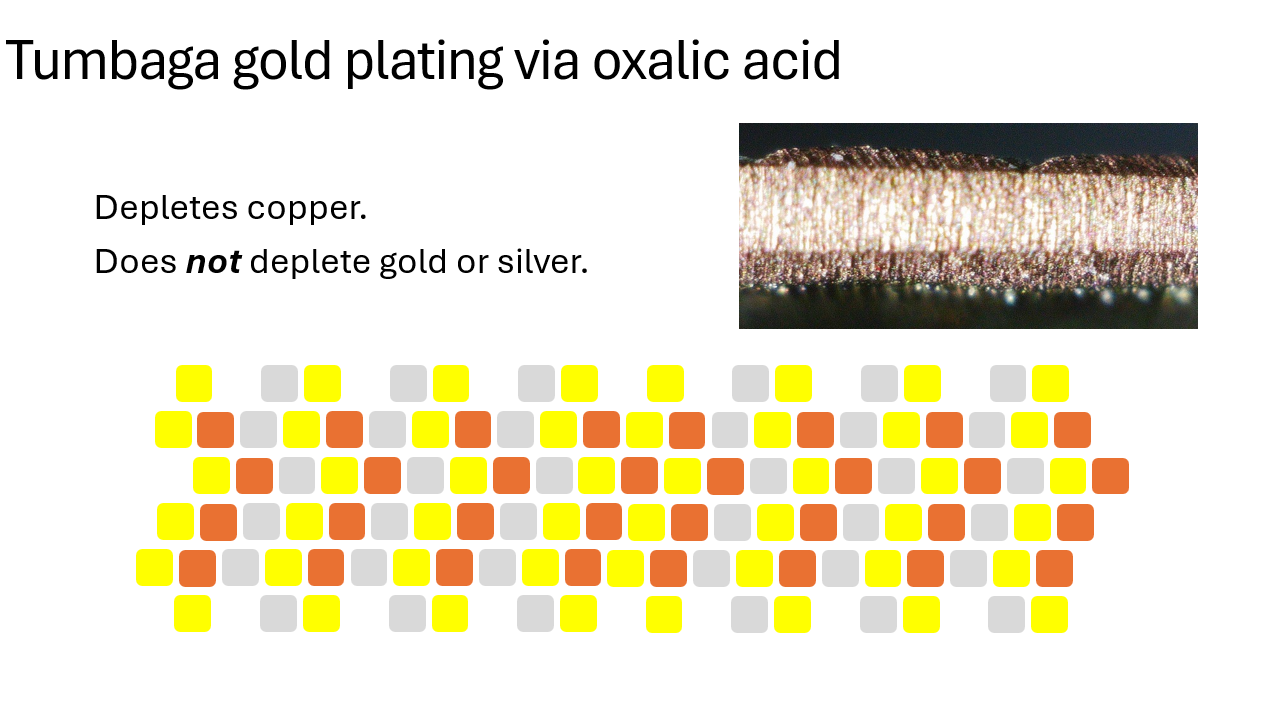

So, imagine all those little colored squares are like a metal, okay. And each one of those represents gold, copper and silver. So when you use oxalic acid, what it does is see, watch it.

So, imagine all those little colored squares are like a metal, okay. And each one of those represents gold, copper and silver. So when you use oxalic acid, what it does is see, watch it.

All the copper on the surface disappeared. What’s left is gold and silver. So, if you cut a plate like that, you see the top and the bottom are now gold plated. And the middle is this composite. Does that make sense? That’s how that works.

All the copper on the surface disappeared. What’s left is gold and silver. So, if you cut a plate like that, you see the top and the bottom are now gold plated. And the middle is this composite. Does that make sense? That’s how that works.

They didn’t have electroplating. This is how gold plating is done nowadays because it’s easy. It’s simple to do that. But, ancient Americans and in the Old World and into the New World didn’t really have access to electricity. So they used depletion, gilding. Okay. So that’s alloy gold content there.

We’re going to range from an eighth part gold, 12.5%, all the way up to pure gold.

Again, I don’t care what it is. I don’t care what the witness statement said. I just said, ‘look, what’s the minimum amount of gold that makes sense?’ And if you look at ancient artifacts in museums, right around 10-15% is the lowest gold content that we have examples of from the Old World and the New World.

Percent Sealed

Percent sealed. This matters, because you’ve got to fit the words of the Book of Mormon on it. So you have to know how much is sealed and how much isn’t. Some reports are 33% sealed and other reports are 66% sealed. And then there are reports in between that.

Just really quick on that.

Just really quick on that.

- “A part was sealed,”

- “half was sealed,”

- “a third was sealed,”

- “a large portion was sealed,”

- “two thirds were sealed.”

We just have pretty vague statements. Again, I don’t have to interpret who’s right. I’m just going to do all of them.

Total Number of Plates

And then the total number of plates, we don’t know. We’re going to do the math and it’s going to spit out how many plates make sense.

Possible Configurations

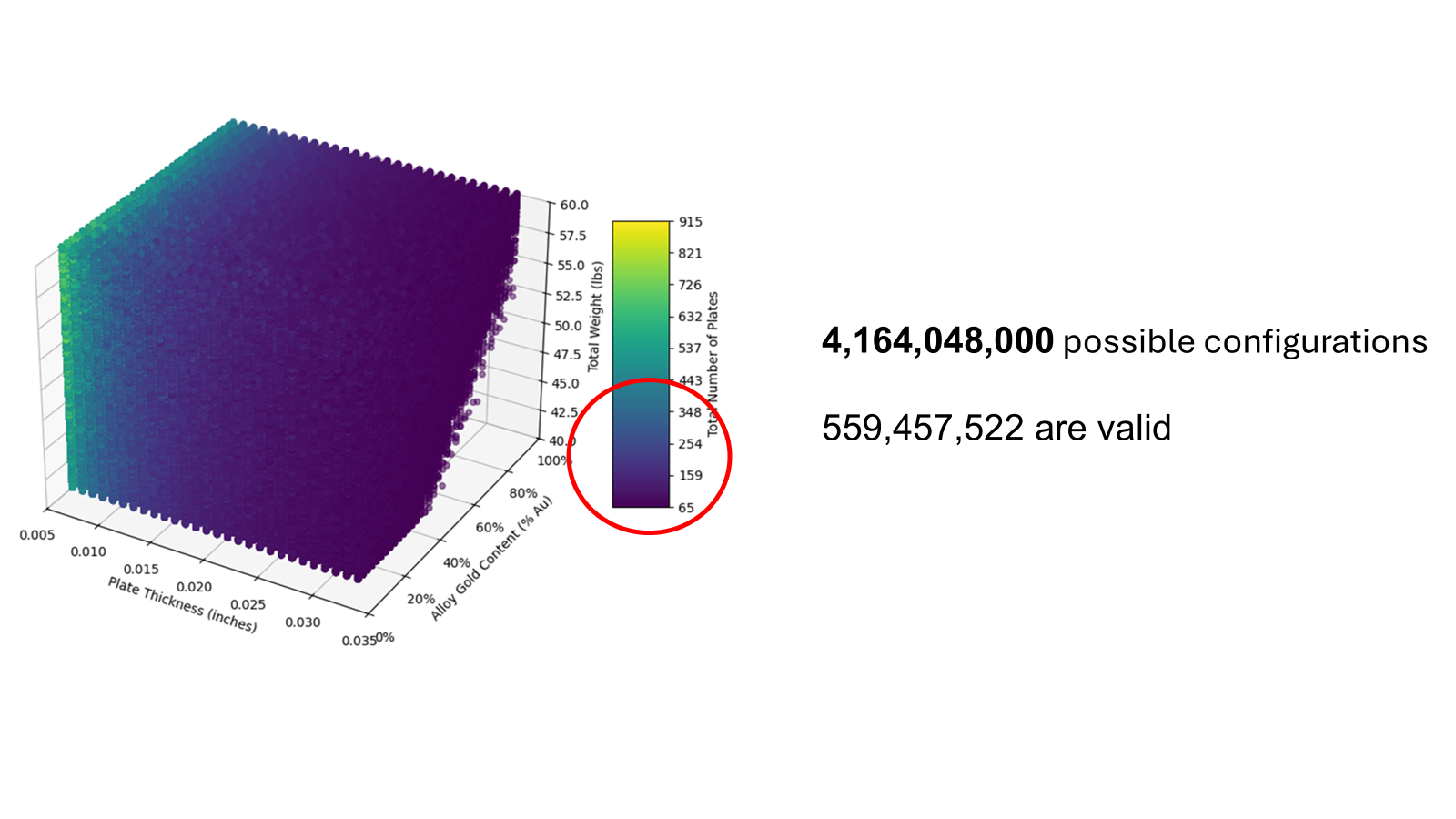

So, anyway, you do this math, all those different variables, you do every single possible combination, and there’s 4 billion different combinations.

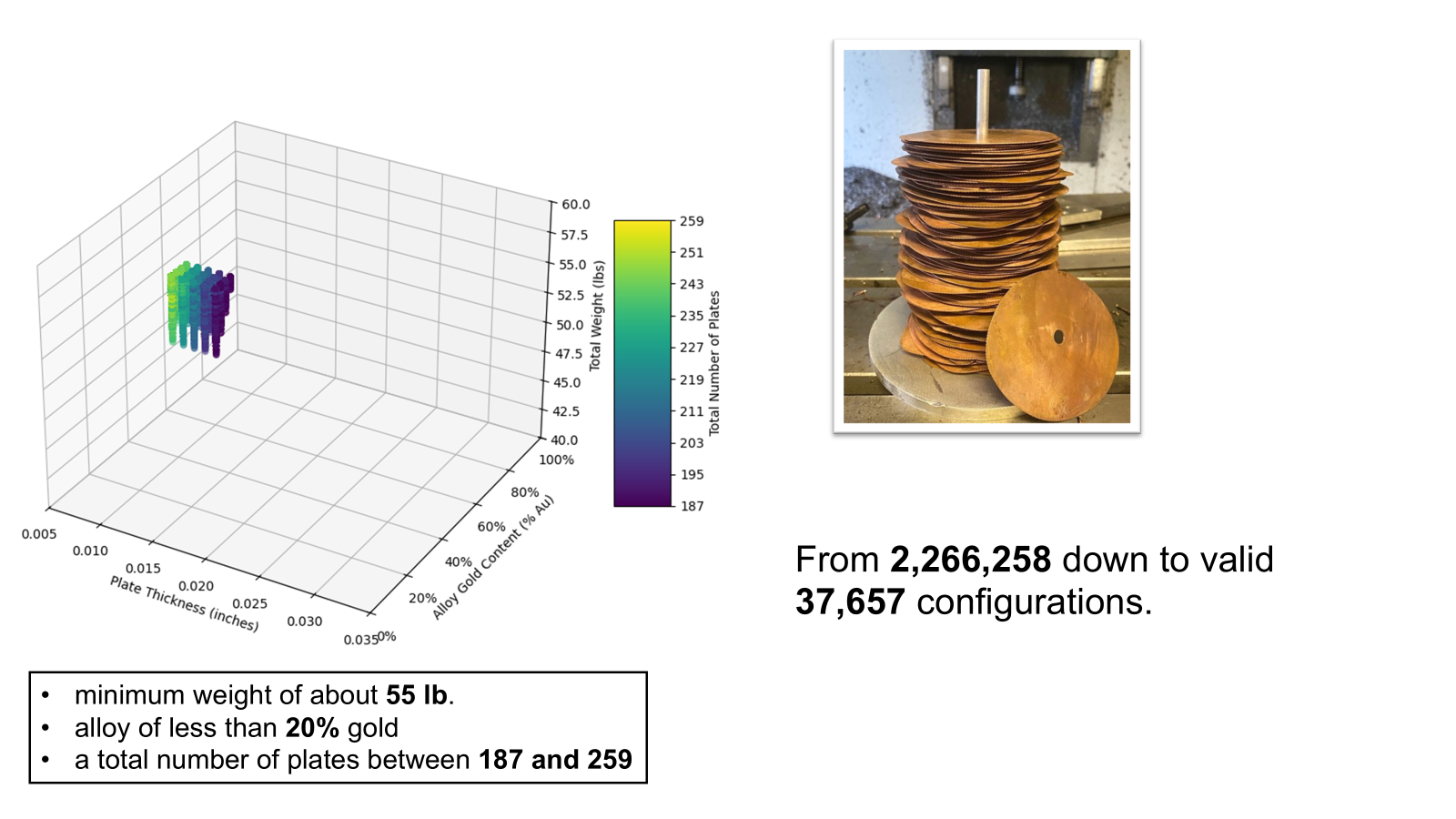

This graphic is a depiction of one axis of the thickness of the plates, the other one, the gold alloy content. And then the weight is the Z axis there. The colored bar shows how many plates there are.

This graphic is a depiction of one axis of the thickness of the plates, the other one, the gold alloy content. And then the weight is the Z axis there. The colored bar shows how many plates there are.

Out of the 4 billion – remember, I showed you an example of an invalid version that didn’t work, it was too short of a stack. And then I showed you a version of the valid one. Okay, so out of 4 billion, only half a billion are valid. Of course, half a billion is a whole lot of, you know, examples of a good valid plate configuration.

Interesting things to take out of this. The most possible plates at this level of just broad data, 900 plates total. But that’s the yellow. That’s the top of the bar there. And you see very little yellow on the three dimensional graph. It’s all the way to the left. Mostly it’s here.

65 is the lowest number of plates, and then it gets up to about 300. So that’s the range where it’s most commonly actually valid. We’ll refine this a little more because it’s not very satisfying to say, “Well the number of plates could be 65 or 900, and there’s half a billion combinations.”

I mean, on the one hand it’s satisfying. It’s like, wow, there’s so many ways it could work. But I want to know more about what the plates may have actually looked like.

So, here’s your answer to this question. Yes, the math is super easy, and there’s 500 million different ways the plates could totally work physically. So ta da, we’ve answered that.

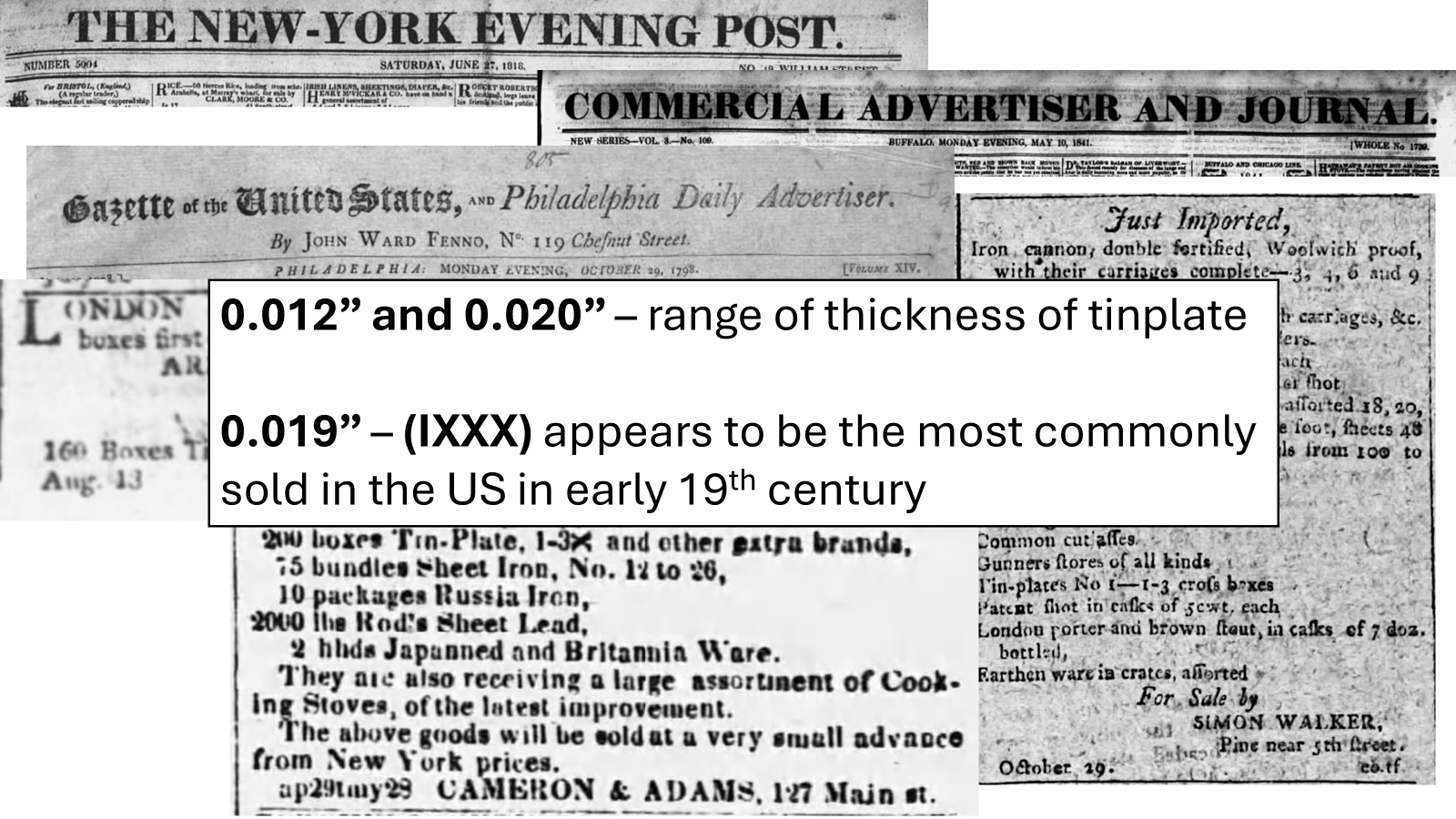

Joseph’s Description

Next, let’s see what Joseph Smith says, okay? Because he’s probably the most familiar with it. So we’re gonna prioritize his statement. He says:

Next, let’s see what Joseph Smith says, okay? Because he’s probably the most familiar with it. So we’re gonna prioritize his statement. He says:

“Each plate was six inches wide and eight inches long and not quite so thick as common tin. . . the volume was something near six inches in thickness.”

So that’s the height of the stack.

That’s in 1842. Probably a little over a decade or so after the last time he saw the plates. But, you know, I think he’s a pretty good witness. So, we’re going to see if we take his numbers and kind of do a plus or minus range, but kind of narrow it down a little bit and see what we got, see if we can get more specific.

About Tinplate

Real quick on tinplate. So I kind of did a deep dive on tinplate. Most tinplate was made in Wales in the first part of the 19th century and imported into the US. It was made of iron, not steel. (Modern tinplate is made of steel.) And, you know, they made stuff out of it. So what was common tin in the 19th century?

Real quick on tinplate. So I kind of did a deep dive on tinplate. Most tinplate was made in Wales in the first part of the 19th century and imported into the US. It was made of iron, not steel. (Modern tinplate is made of steel.) And, you know, they made stuff out of it. So what was common tin in the 19th century?

Well, first of all, I had to go look at a lot of industry literature from the 19th century and learn about all the designations, technical industrial designations, for tinplate thickness.

And then I looked at all the newspapers of the 19th century to see what kind of tinplate thickness was for sale. And it turns out that in America, basically, 19,000th of an inch was pretty much the only thing for sale. That’s IXXX in industrial terms, that’s the most common tin. So, that’s a pretty decent guess about what ‘common tin’ meant.

Using Joseph’s Description to Refine our Results

We’re going to put a range in for this next level and say, ‘well, if we narrow this down, what does the Joseph Smith description get us?’

We’re going to put a range in for this next level and say, ‘well, if we narrow this down, what does the Joseph Smith description get us?’

Well, what it does is it basically goes from half a billion, and now only about 2 million that are valid. So we’ve narrowed it down a little bit. We have a range here of plate thickness, and weight and size.

And so basically we’re down to, hey, they’ve got to weigh at least 42 pounds. They’ve got to have at least 48% gold in them. And the plates are between 151 and 259 in number of plates. So that’s what Joseph Smith gets us.

The Void Data

The next thing I got to look at is the void data. Because it turns out that’s a pretty important variable. And again, this is the space between plates.

The next thing I got to look at is the void data. Because it turns out that’s a pretty important variable. And again, this is the space between plates.

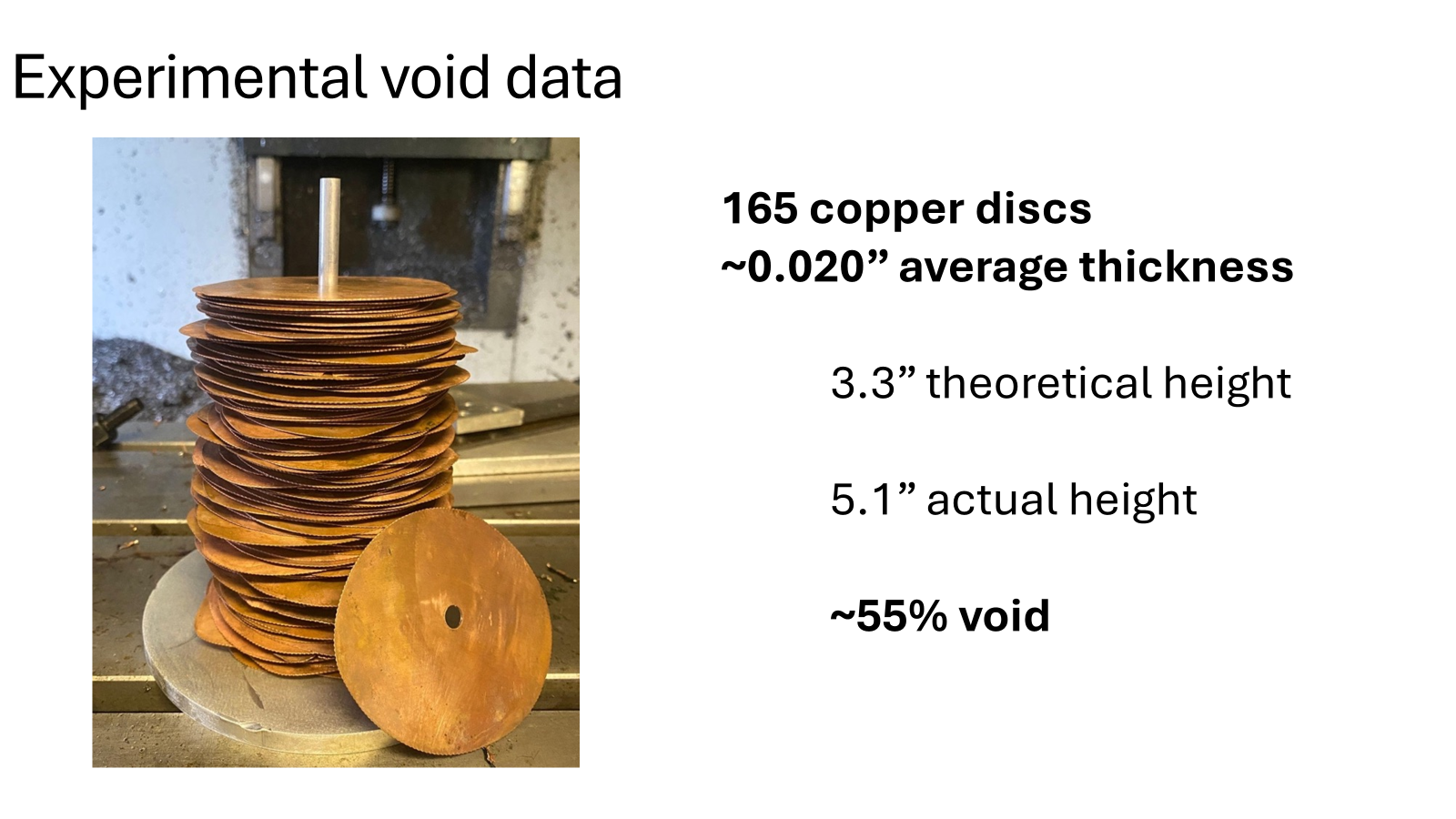

I went ahead and made 165 copper disks, at about 20,000th of an inch in thickness. And I just stacked them and I measured them because that’s a good way to figure out what the void might be.

It turns out that theoretically, this should be 3.3 inches high, if you multiply 165 by 20,000ths of an inch. But it actually ended up being 5.1inches, and that’s because there’s space in between, right?

And so that gives me about a 55% void. So if you stack plates, it’s about 55% void. And it turns out in some subsequent experimentation, the bigger the plates I made, the more the void was; which, you know, makes sense. Because the bigger the plate:

- the more imperfections you’re going to have in it,

- the more probability you’re going to have an increased void.

Narrowing it Down

So anyway, so if you take about a 55% void or with, you know, kind of narrowed in that range, well that gets us down to about 37,000 configurations that are valid. We’re really narrowing in on what the plates might have been like as far as this goes.

So anyway, so if you take about a 55% void or with, you know, kind of narrowed in that range, well that gets us down to about 37,000 configurations that are valid. We’re really narrowing in on what the plates might have been like as far as this goes.

This gets us to:

- a minimum weight of 55 pounds,

- an alloy of less than 20% gold, and

- the number of plates between 187 and 259,

based on this experimental data. So we’re starting to get more specific here.

Two Visualizations

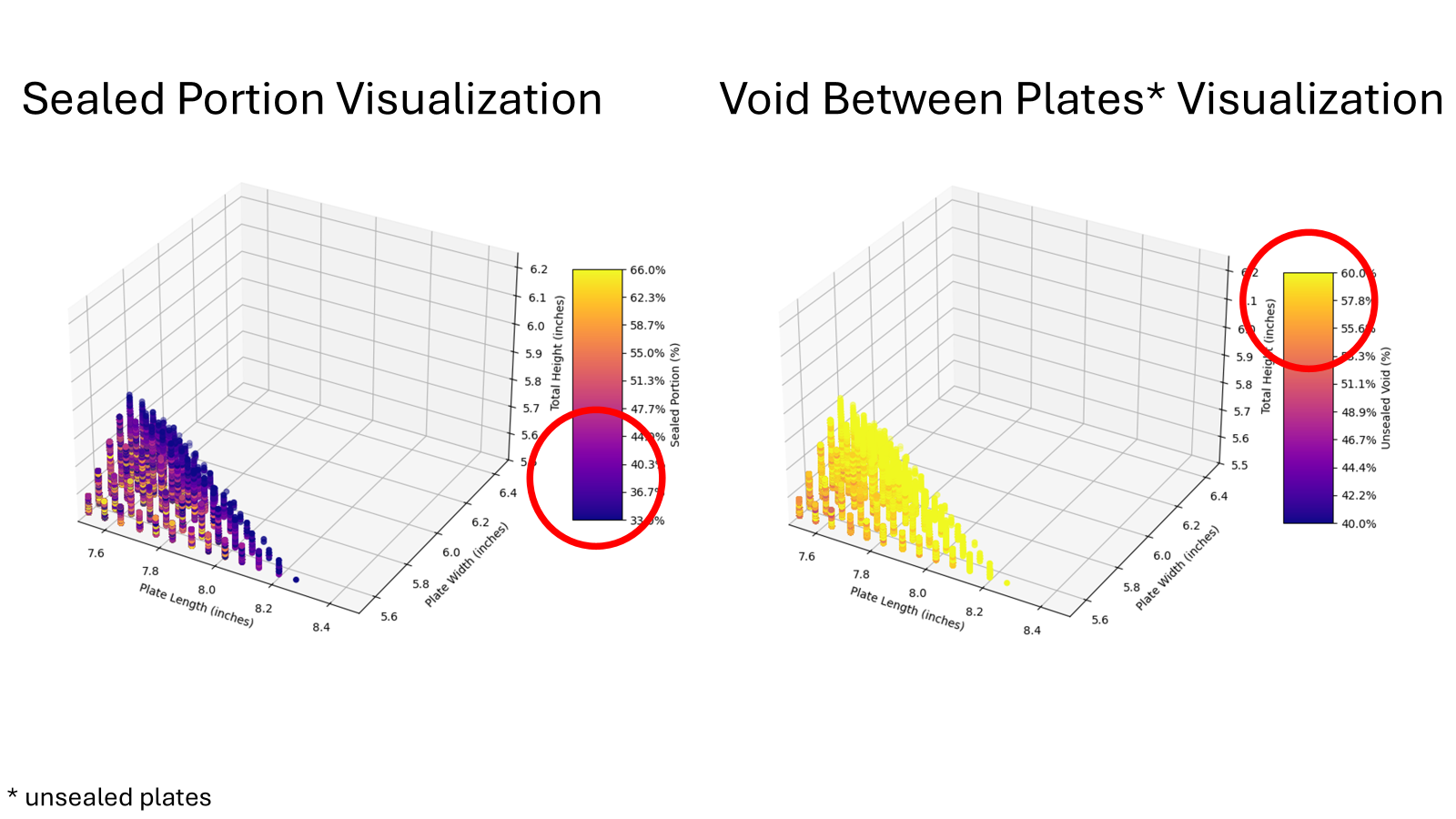

Also, where this gets us – the sealed portion. This is a graph that shows kind of how the sealed portion comes out. And I don’t know if you can see that. But this visualization shows (that dark purple) is dominant and that’s around 30 to 40%, as valid sizes of the sealed portion. So that’s kind of interesting, right?

Also, where this gets us – the sealed portion. This is a graph that shows kind of how the sealed portion comes out. And I don’t know if you can see that. But this visualization shows (that dark purple) is dominant and that’s around 30 to 40%, as valid sizes of the sealed portion. So that’s kind of interesting, right?

If someone says, ‘two thirds were sealed’, I’m going to say, ‘yeah, the math doesn’t support that’. If someone says it was half sealed, I’d be, I mean, maybe if you squint, you can make that work, but it’s really a third. It’s a third or very close to a third.

The void between the plates is dominated by yellow color. That’s around 50-60% void. That matches up pretty well with the experimental data. Okay, so we did part one.

Which Configurations Fit the Book of Mormon?

Let’s get to part two. How many of these configurations still work with the valid Book of Mormon? Because we’ve got 37,000 valid configurations where the physics and the math just nails it.

Let’s get to part two. How many of these configurations still work with the valid Book of Mormon? Because we’ve got 37,000 valid configurations where the physics and the math just nails it.

So we’re good, right? And that’s the most narrow we can get. That’s favoring Joseph Smith’s description, that’s including experimental data around the void. This is the most conservative number. We’ve got tens of thousands of valid configurations.

So how do we put this on those? Well, this is kind of fun. Watch what we do here.

So how do we put this on those? Well, this is kind of fun. Watch what we do here.

Text Questions

So first of all we have to say how much text is there? And then we got to say how big is the text? Like physically. Is it like really big font sizes or really tiny? And then we’ve got to say how dense is the translation?

So first of all we have to say how much text is there? And then we got to say how big is the text? Like physically. Is it like really big font sizes or really tiny? And then we’ve got to say how dense is the translation?

How Much Text is There?

So, how much text is there?

So, how much text is there?

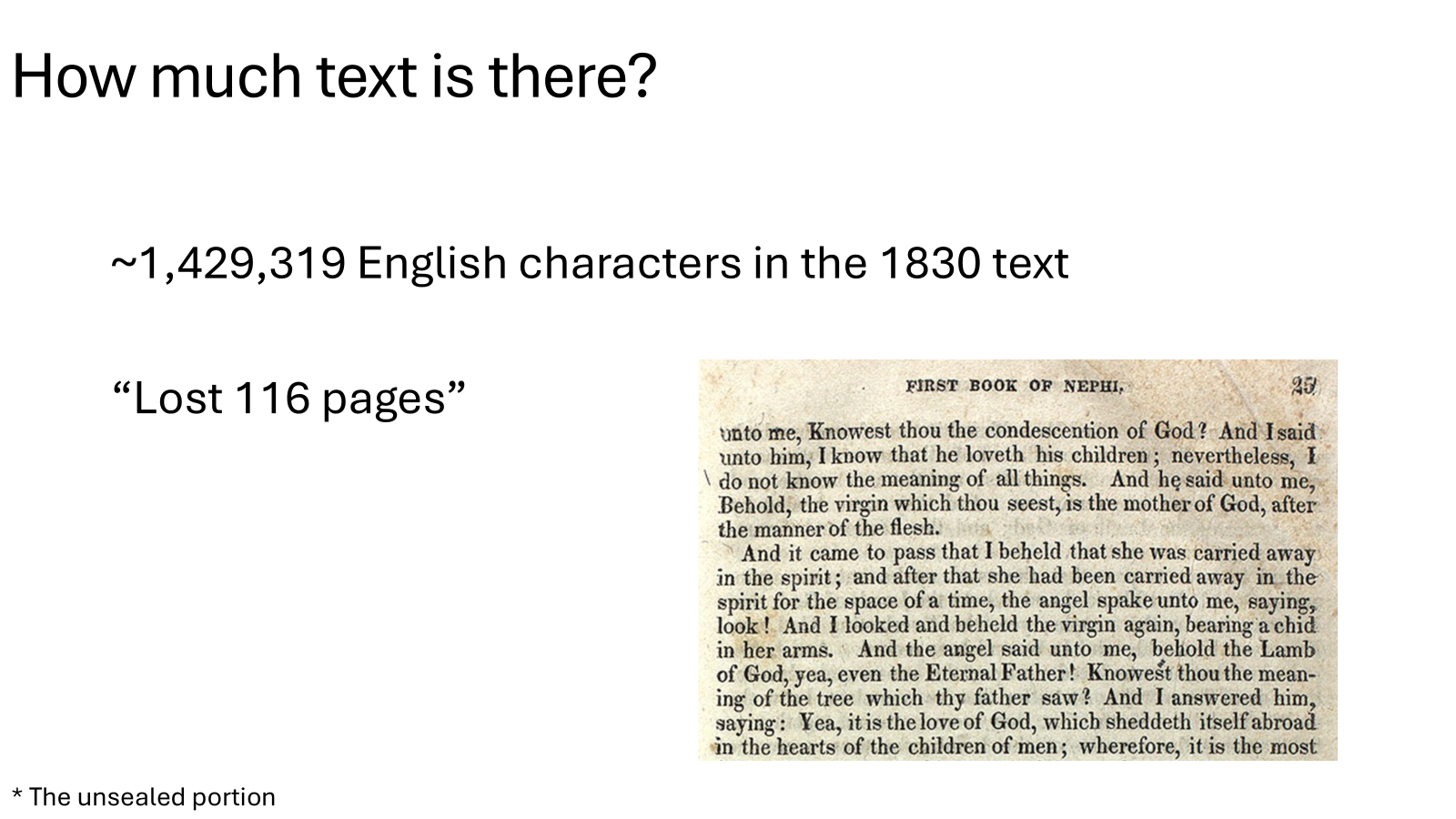

There were about 1.4 million English characters in the 1830 text. I don’t care about words. I just don’t care because words are different sizes. I just don’t care. What I care about is a character, because that takes up a space. I know what a character takes up, so that’s all I care about.

And then we’ve got to add in the last 116 pages. Of course, I don’t know what that means. When you say ‘116 pages’, I don’t know what that means. I don’t know, that’s just what they say. Okay.

Estimating the 116 Pages

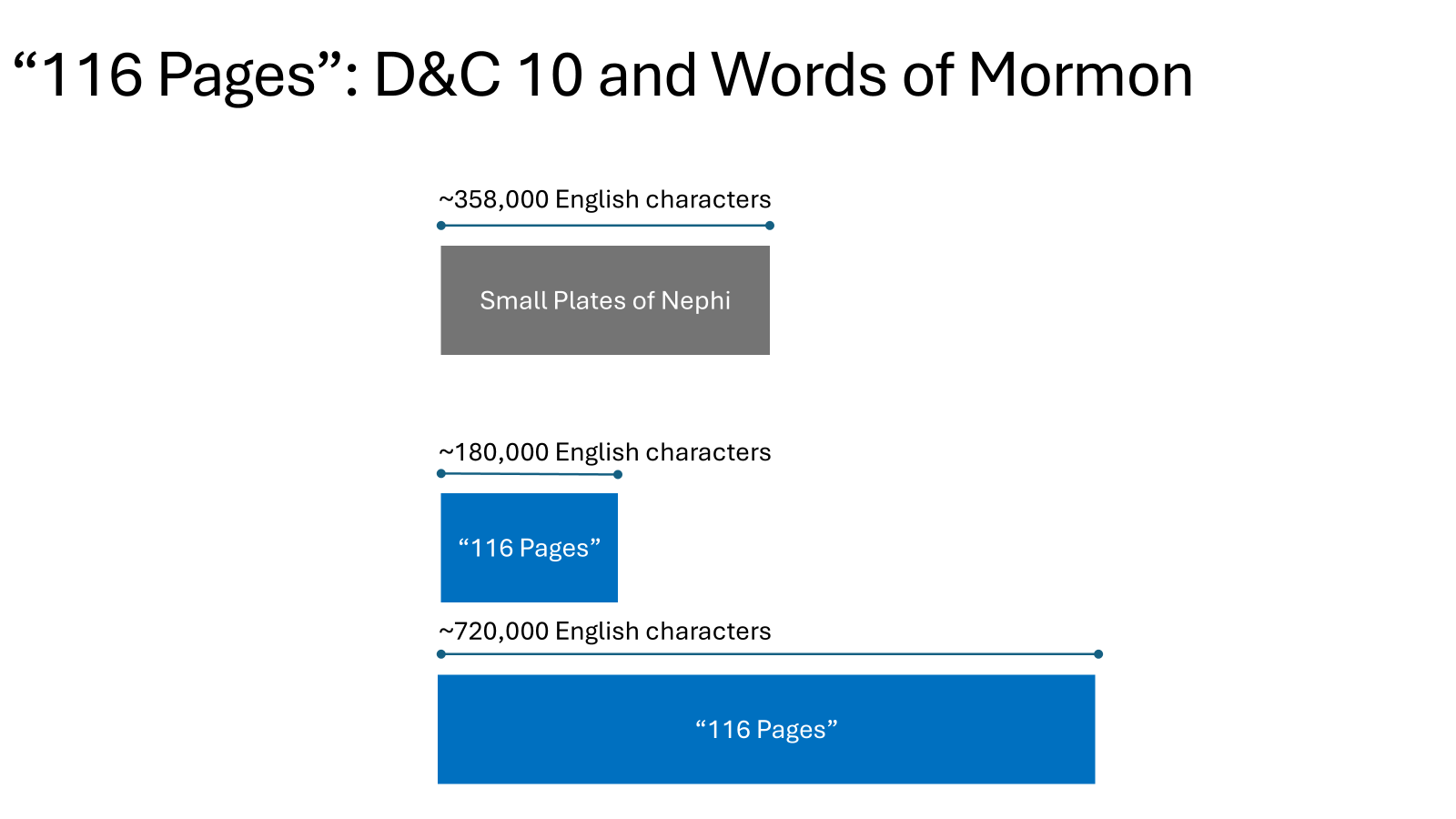

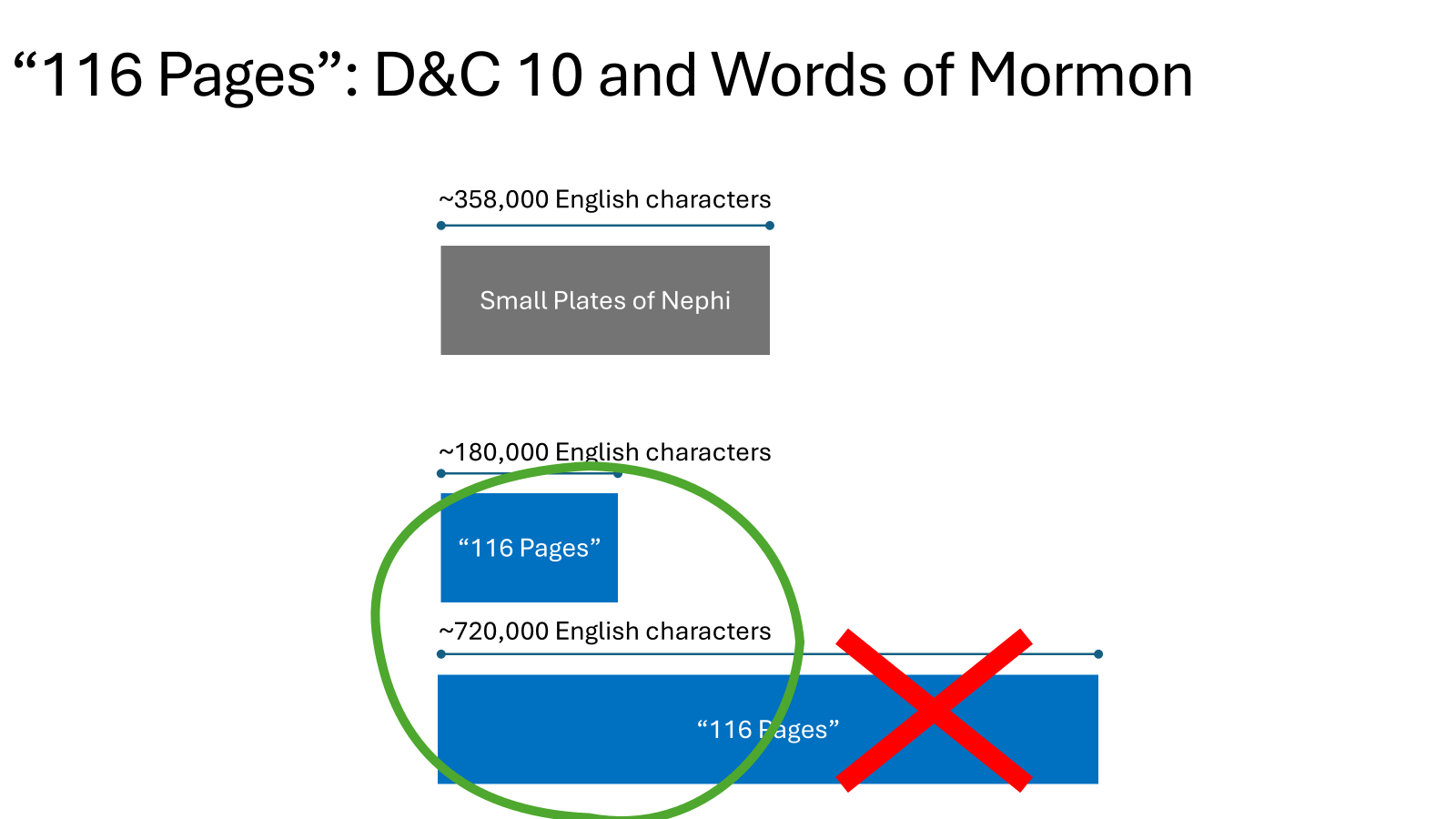

If you look at Doctrine and Covenants section ten and Words of Mormon, I think one of the things you can see is, well, the small plates of Nephi are somehow parallel with these 116 pages. There’s about 358,000 English characters in the small plates of Nephi.

If you look at Doctrine and Covenants section ten and Words of Mormon, I think one of the things you can see is, well, the small plates of Nephi are somehow parallel with these 116 pages. There’s about 358,000 English characters in the small plates of Nephi.

So, the 116 pages, maybe they’re half the size of the small plates of Nephi. Maybe they’re twice the size. I don’t know. We’re just going to say it’s one of those two or somewhere in between.

You can make an argument, “Oh, no, no, it’s three times. It’s five times.” Like, I don’t know. When I read D&C 10 and the words Mormon, I’m thinking, well, it’s a pretty decent range.

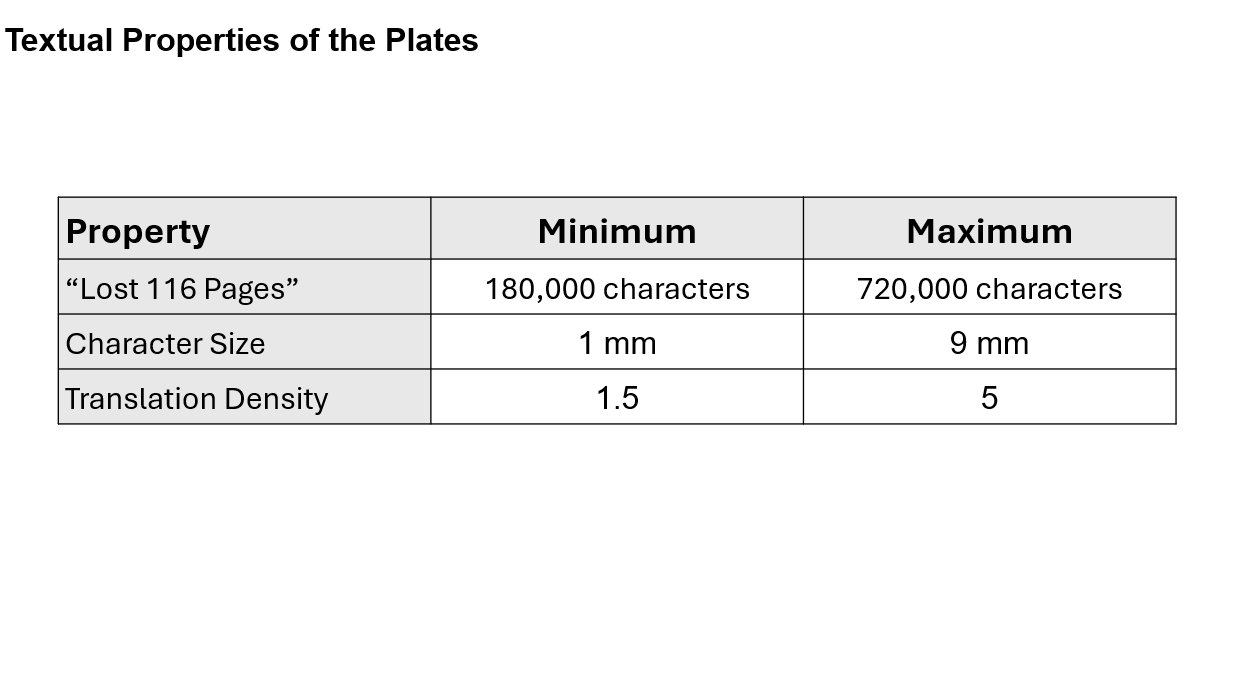

The Textual Properties of the Plates

Okay. So that’s what we do. We put 180,000 characters as our minimum. And then we put 720,000 for a maximum for that.

Okay. So that’s what we do. We put 180,000 characters as our minimum. And then we put 720,000 for a maximum for that.

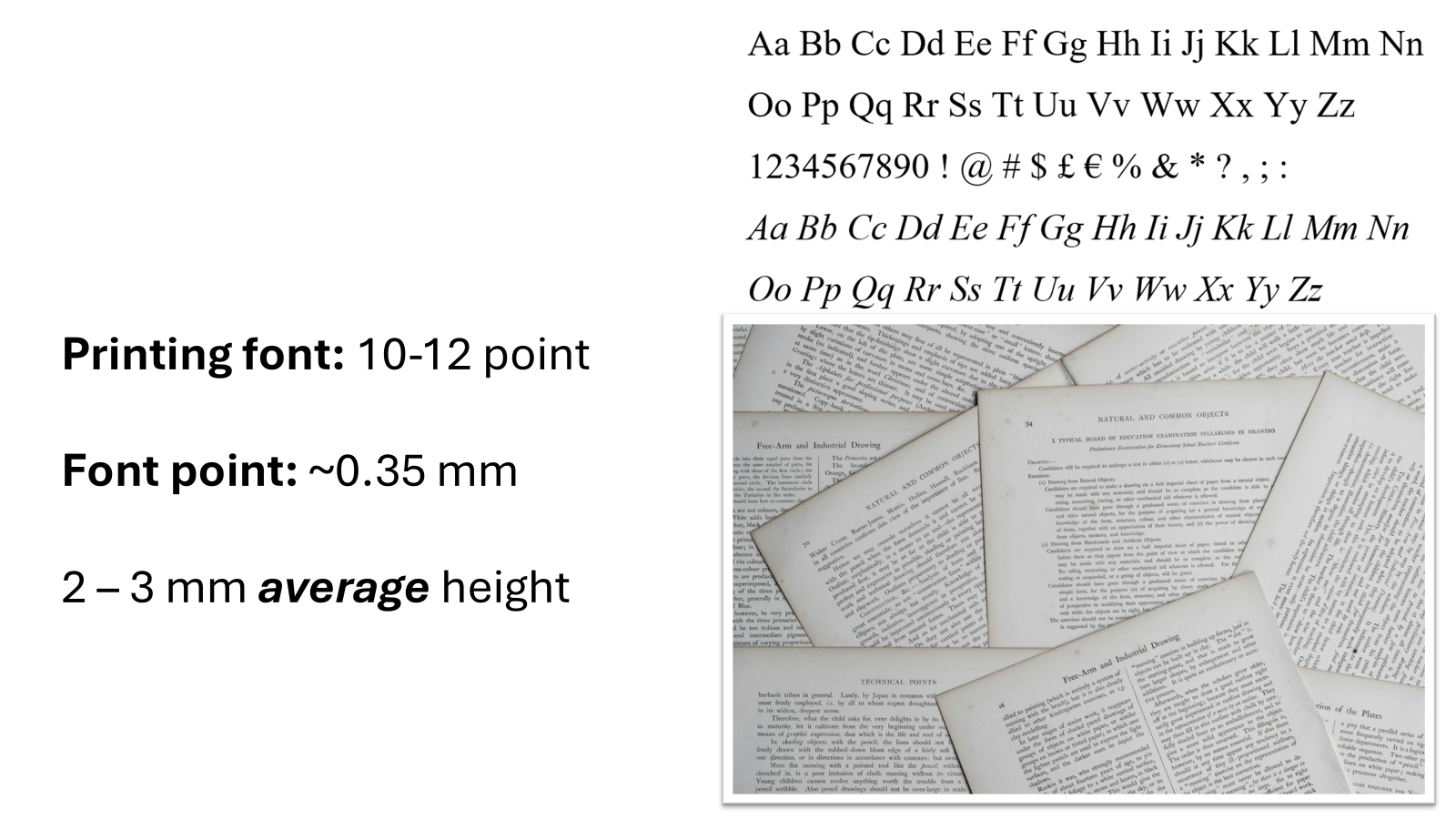

Character Size

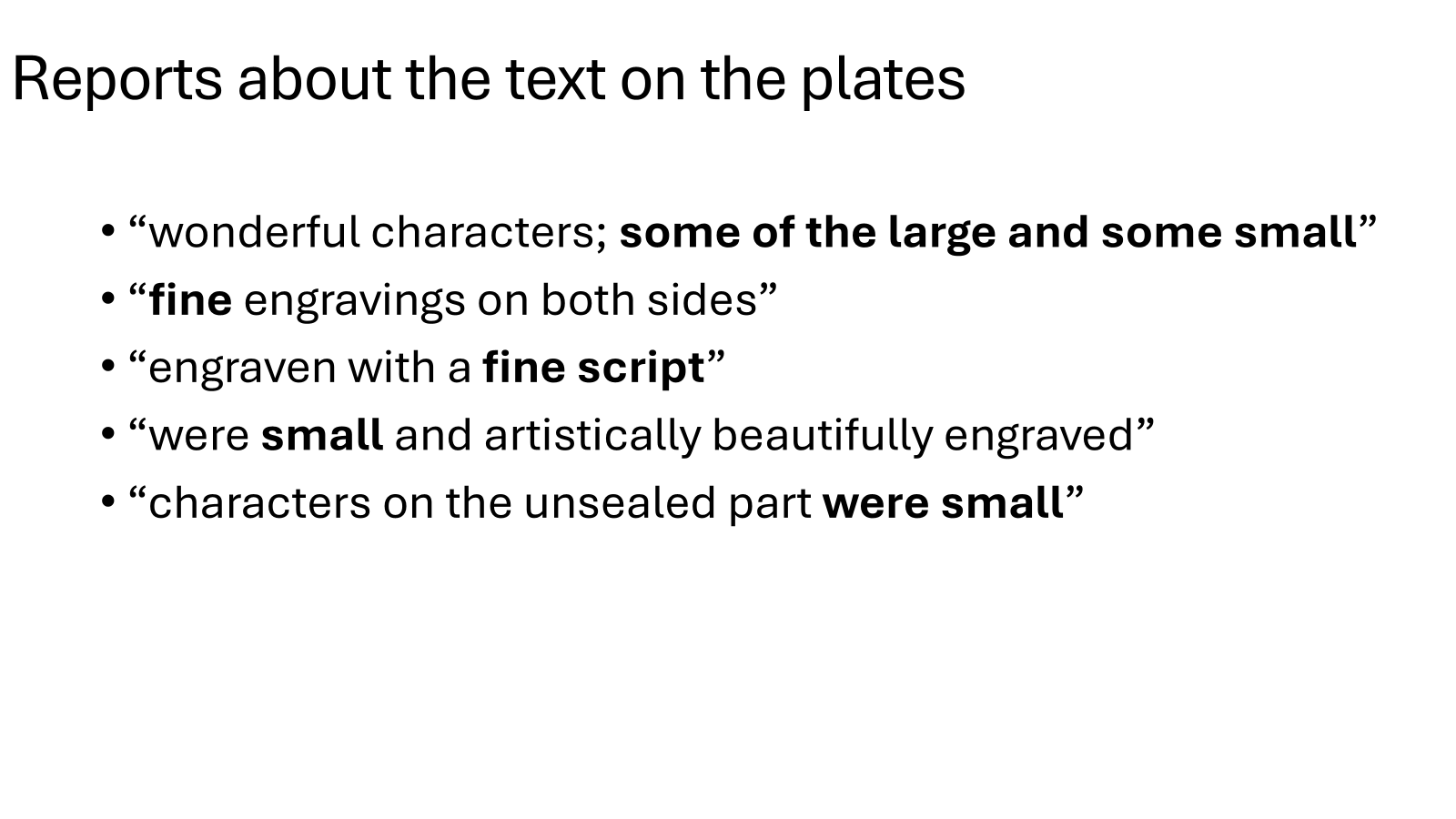

Next we got to deal with character size. So 1mm to 9 millimeters in height of character size. Now how do we come up with that?

Well, first of all, let’s look at the reports; the unreliable, flaky witness reports. But we’ll still look at them because we have to look at them. Right? So some of them were large and some were small, and there’s fine engravings and there’s fine script, and they’re very small and they’re really small.

Well, first of all, let’s look at the reports; the unreliable, flaky witness reports. But we’ll still look at them because we have to look at them. Right? So some of them were large and some were small, and there’s fine engravings and there’s fine script, and they’re very small and they’re really small.

So anyway, a lot of people said they were small, but that doesn’t mean anything. I don’t know what that means.

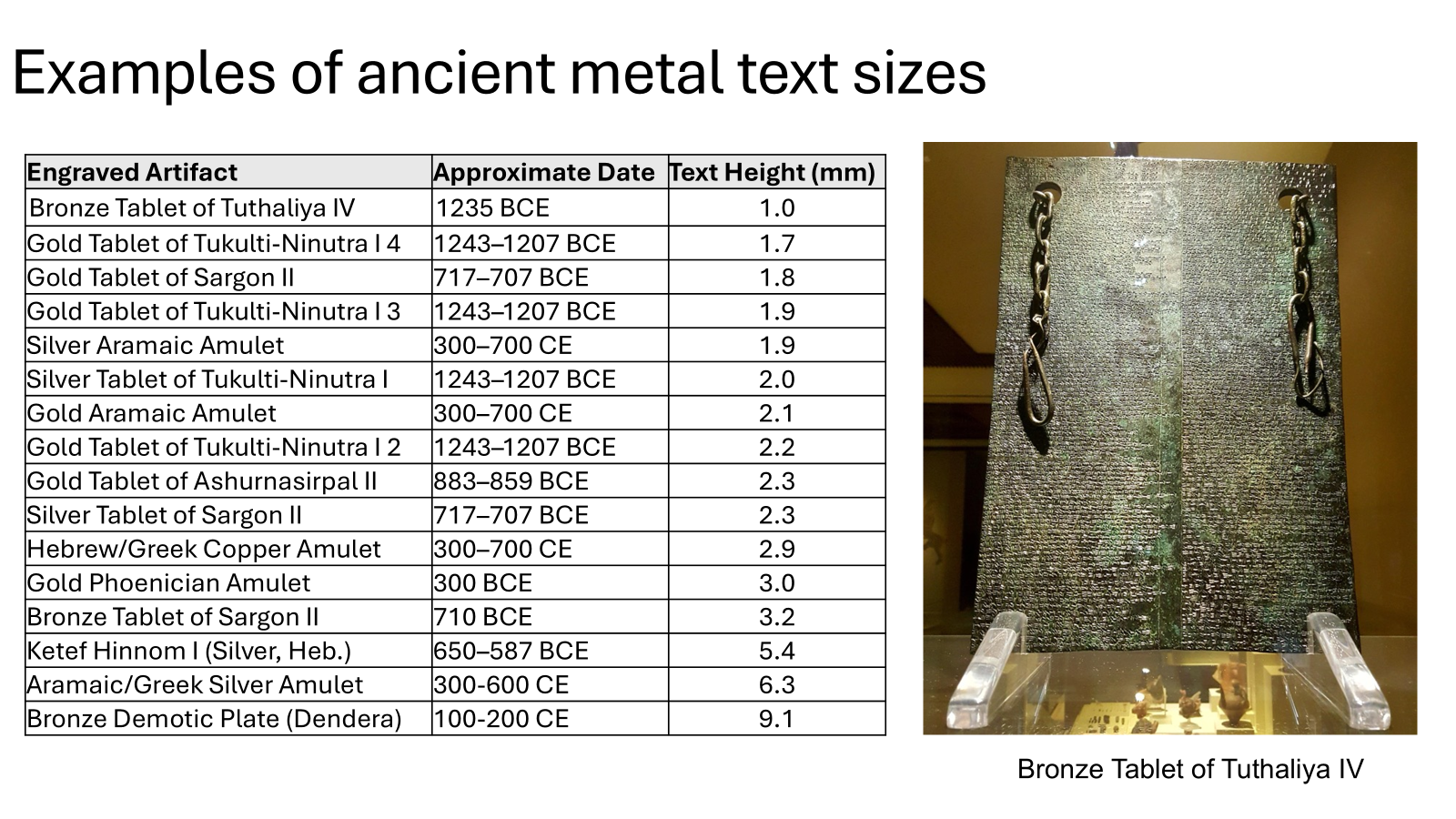

So what do we do? We look at actual records from the old world that have writing on them. Neal Rappleye did some great work on this. And I’ve taken some of his work and, and done some additional math on it.

So what do we do? We look at actual records from the old world that have writing on them. Neal Rappleye did some great work on this. And I’ve taken some of his work and, and done some additional math on it.

Ancient Text Sizes

I came up with this table of all these ancient artifacts and the size of the text on them. So there’s lots of them, and we can measure the size of the text of these characters. Again, I don’t care what language they are, they’re just characters. So long as we’re dealing with characters, we just have to deal with the size.

I came up with this table of all these ancient artifacts and the size of the text on them. So there’s lots of them, and we can measure the size of the text of these characters. Again, I don’t care what language they are, they’re just characters. So long as we’re dealing with characters, we just have to deal with the size.

Interestingly enough, if you look at published books, if you just pick up any old book, it’s going to be about 2 to 3 millimeters in height.

Interestingly enough, if you look at published books, if you just pick up any old book, it’s going to be about 2 to 3 millimeters in height.

Actually, back in the previous chart, the smallest text that we found, at least in that example set, is one millimeter, and the largest is nine millimeters. But you see most of them are 1.3 or 1.9 or 2.3.

You’re like, ‘gosh, two millimeters is so tiny’. It’s actually not. Most books are about 2 or 3mm. That’s how high the average text is. That’s somewhere around 10 to 12.4 font. And if you average the capital letters with a lowercase, that’s what you get.

So actually, ancient writing and modern writing, as far as text size, it’s kind of been about the same for thousands of years, which I guess makes sense if you think about it. So, that’s kind of our character range for the size of the characters.

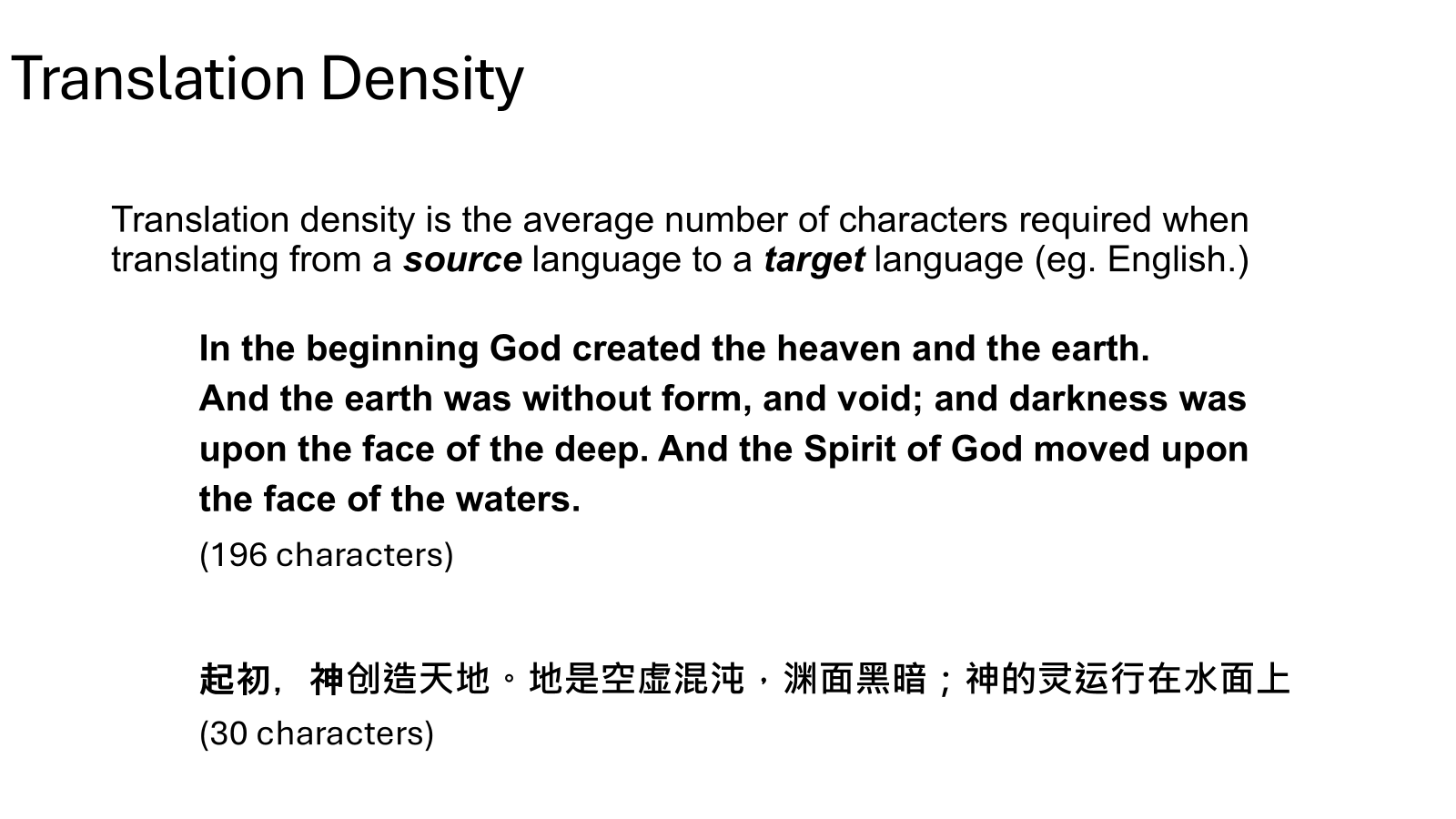

Translation Density

Next, translation density. I’ll explain what translation density is. Translation density is the average number of characters required when translating from a source language to a target language like English.

Next, translation density. I’ll explain what translation density is. Translation density is the average number of characters required when translating from a source language to a target language like English.

I’ll show you an example. So look, it’s the first verse of the Old Testament, and it’s 196 characters in English. In Chinese there are 30 characters. So you would say Chinese is a dense language. The translation between English and Chinese is very dense.

You need much less space to write something in Chinese than you do in English. That’s just the nature of the two languages when they’re written.

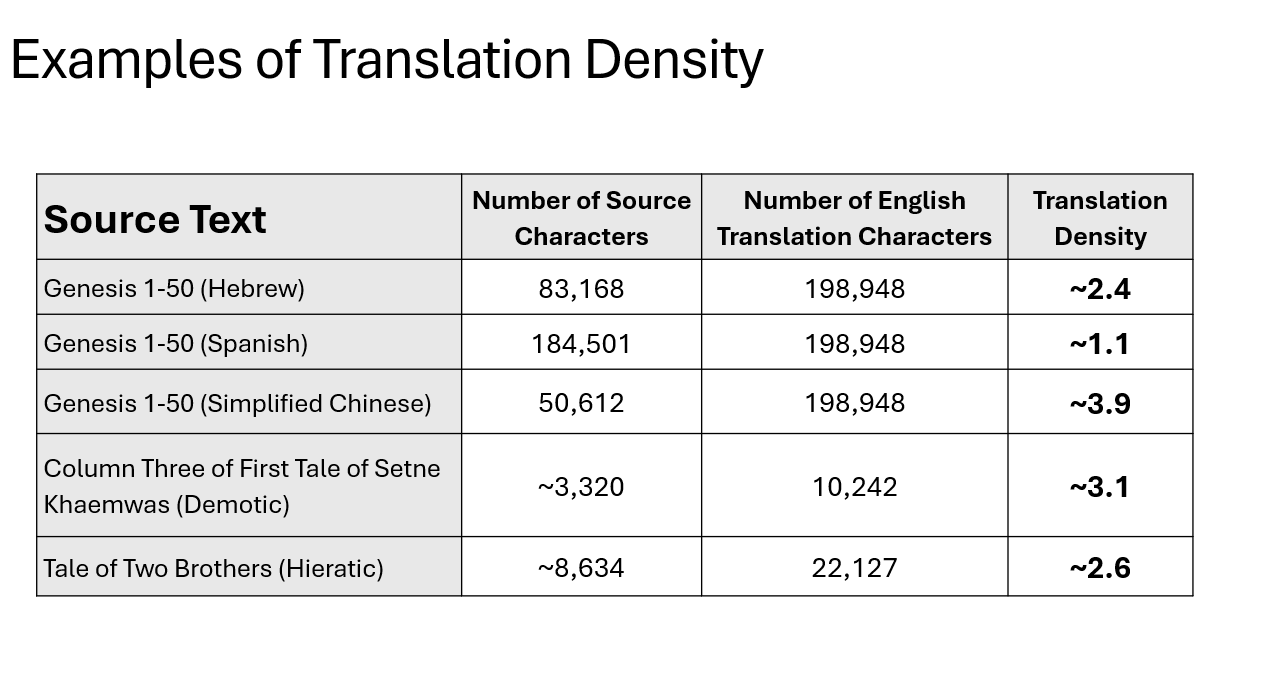

Examples of Translation Density

Let’s look at different languages out there. So, we did Hebrew. (We? I guess I did. I’m just used to saying we because I just want to be inclusive.)

Let’s look at different languages out there. So, we did Hebrew. (We? I guess I did. I’m just used to saying we because I just want to be inclusive.)

The first 50 chapters of Genesis is about 83,000, characters. And then if you translate it into English it is 198,000. So you get a density of about 2.4.

I think the way to think about that is, if you had, say, a 24 page book in English and you translated it into Hebrew, it would be ten pages. So ten pages in Hebrew equals 24 pages in English. Just because of the size difference. Spanish is almost 1 to 1. Genesis 1 through chapter 50 in simplified Chinese, ends up being about 3.9 as the density.

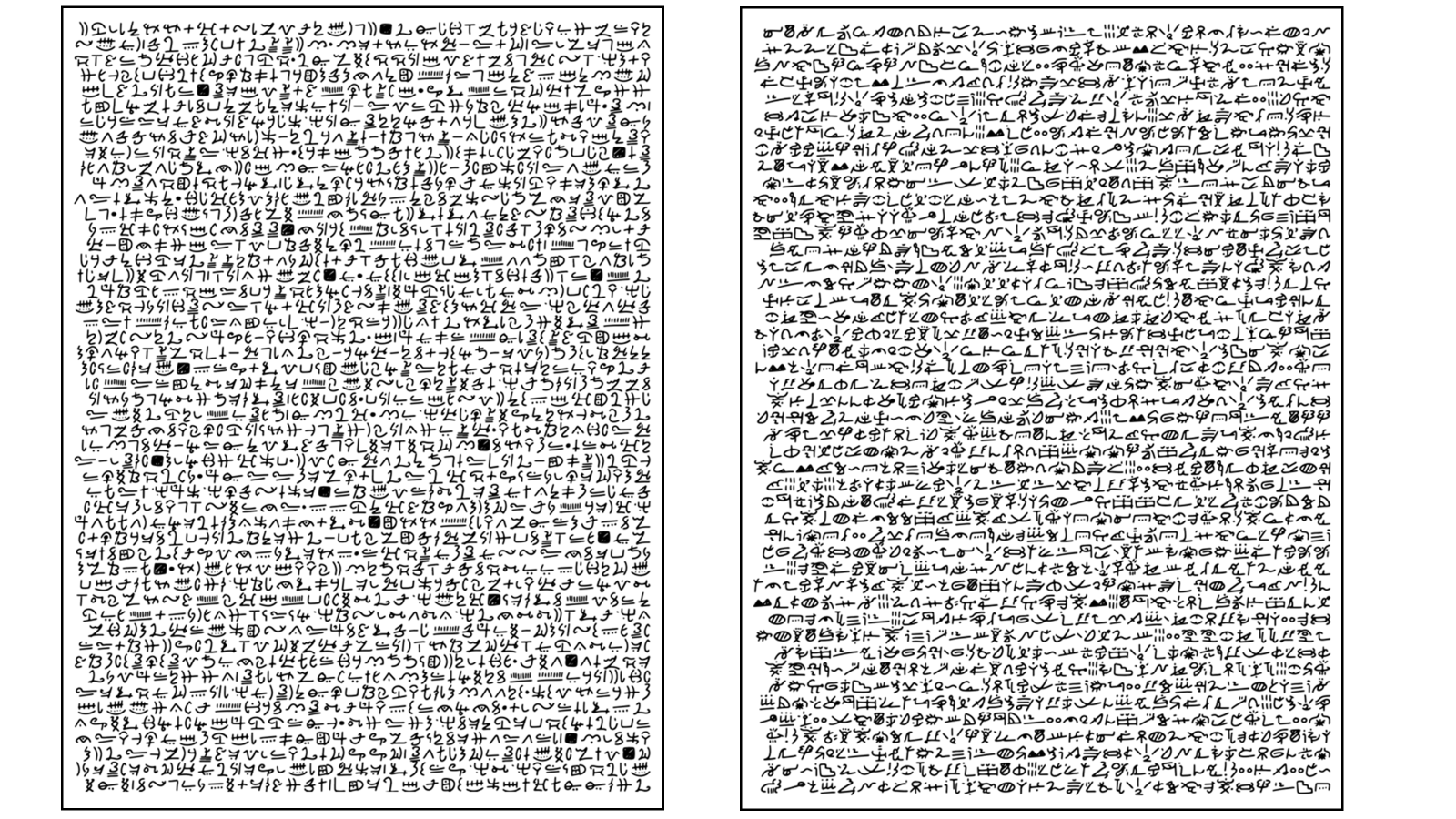

Now, this is where things get kind of interesting because we kind of don’t care about Spanish or Chinese because … Reformed Egyptian, isn’t that right? But, you know, we had to start somewhere. So let’s look at demotic, an ancient Egyptian-like language.

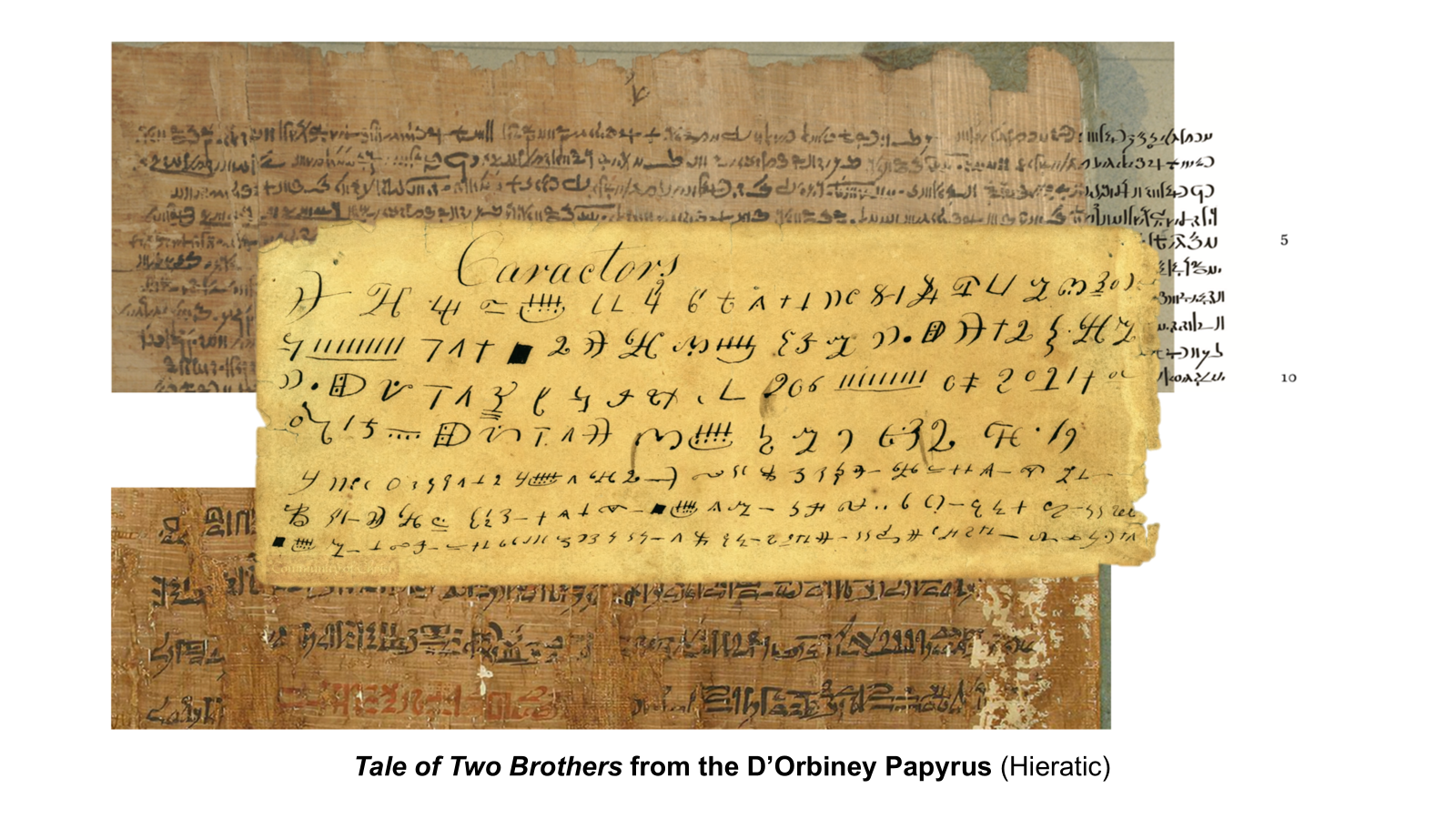

Demotic and Hieratic

So I looked at a couple of texts, the First Tale of Setne Khaemwas. This is a demotic text that has been translated into English. And then the Tale of Two Brothers, has also been translated into English from hieratic. So these are decent bodies of text that have been translated.

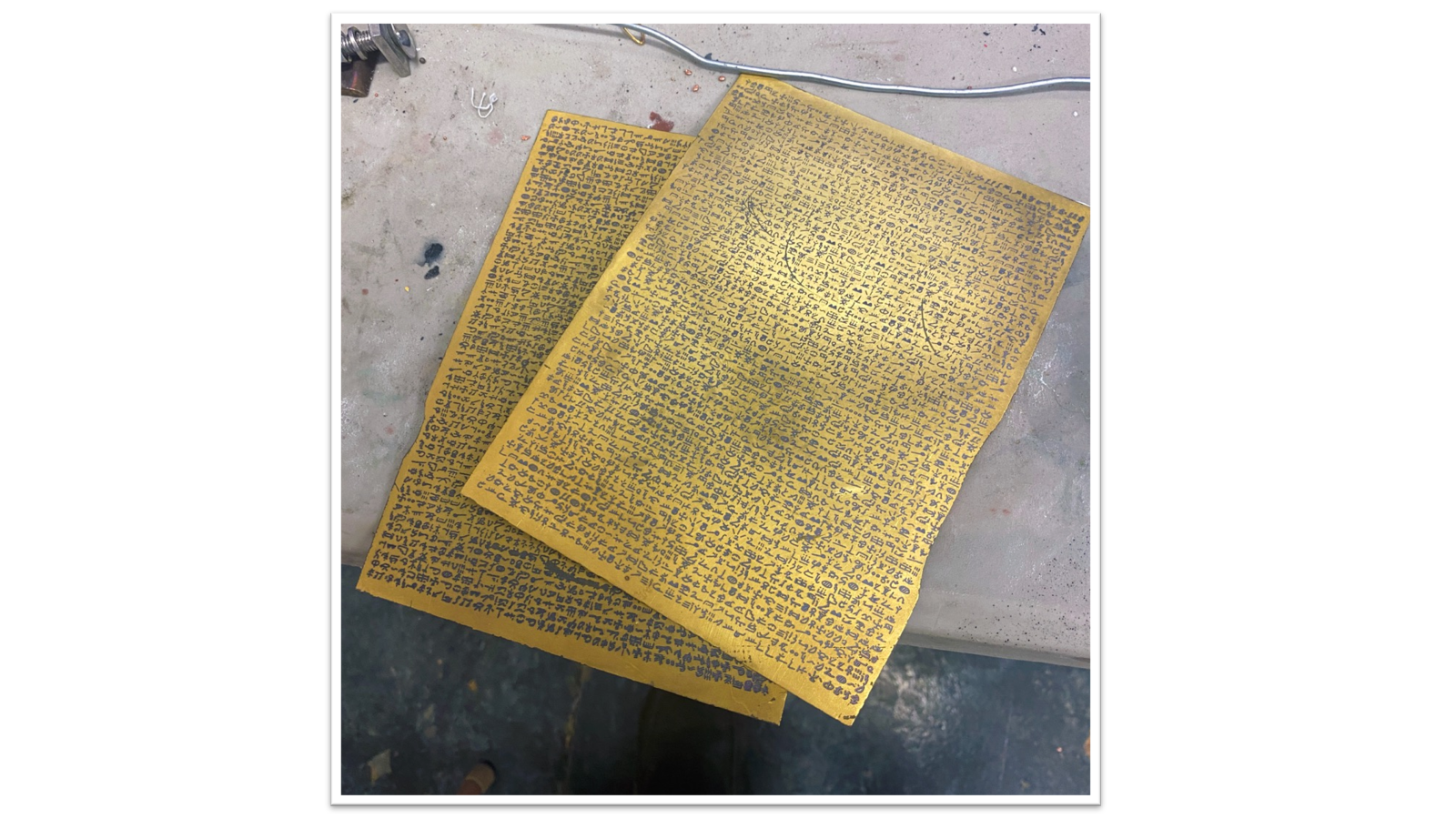

So what you can do is count the characters and then count the English translation. And by the way, this is the characters document. Look, it kind of looks like hieratic and demotic, doesn’t it? Weird, huh?

Anyway, okay, so it ends up we got about 3000 source characters. And then if you translate that into English, you get about 10,000. So that’s about a 3.1 ratio. So it’s a pretty dense language, Demotic. Hieratic is not as dense at 2.6.

Now, I wish I had larger bodies of these ancient languages. I guess if I spent more time I could find more. But that’s what we have to work with.

So that’s translation density. So we end up between 1.5 and 5. And what that means is again, we’re trying to figure out how dense is reformed Egyptian. And this is a range.

Combinatorial Testing With Characters

So when we do our testing, our combinatorial testing, we’re testing 1.5 and 1.6 and 1.7, 1.8, 1.9, all the way up to five. And then we combine that with 180,000 characters or 200,000 characters in the lost pages. And we do all the combinations, millions and millions of combinations because we don’t want to leave any stone unturned.

So, this is the algorithm for that. So you can go program this, if you like, and try it out yourself.

So, this is the algorithm for that. So you can go program this, if you like, and try it out yourself.

Density Results

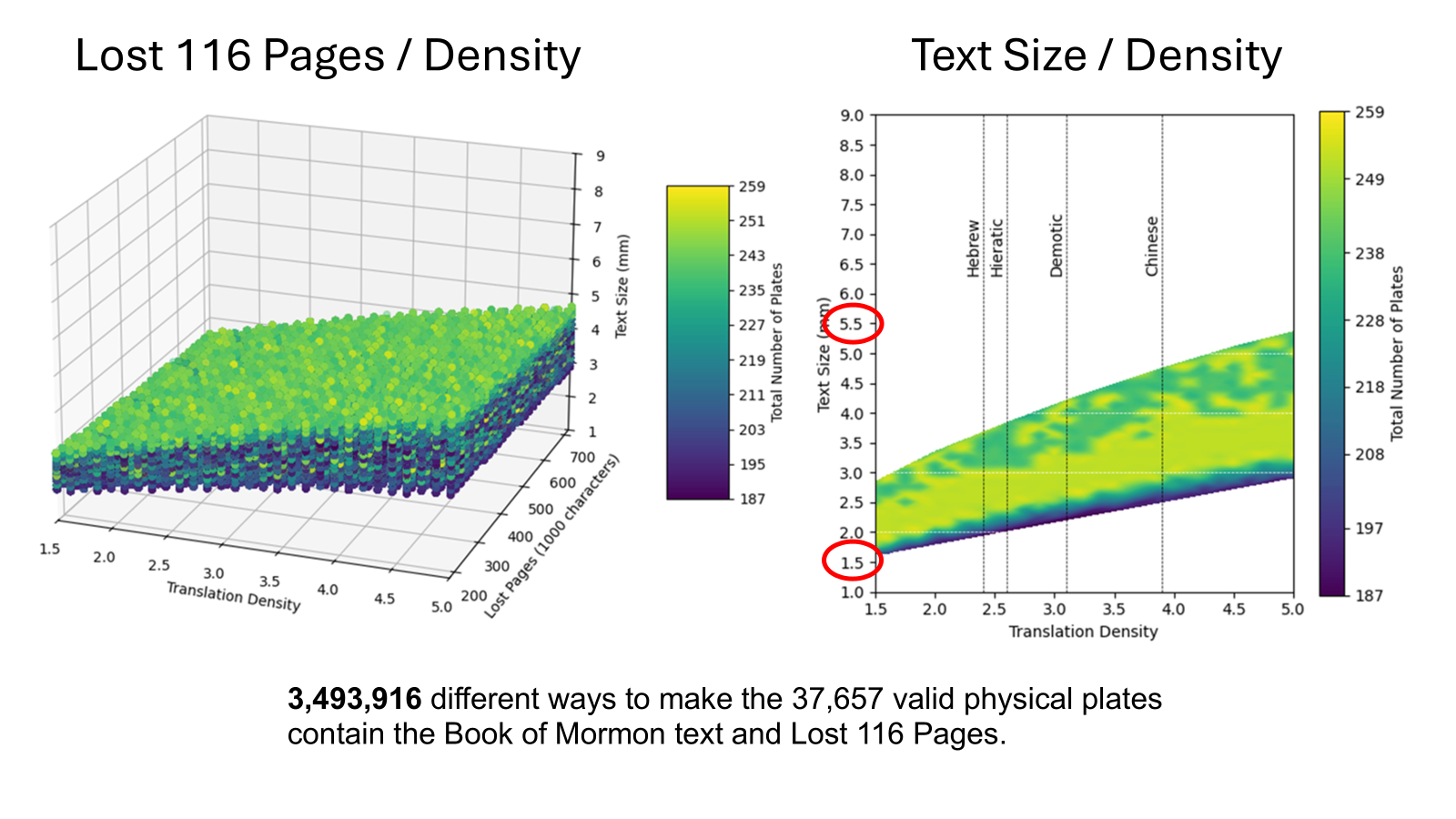

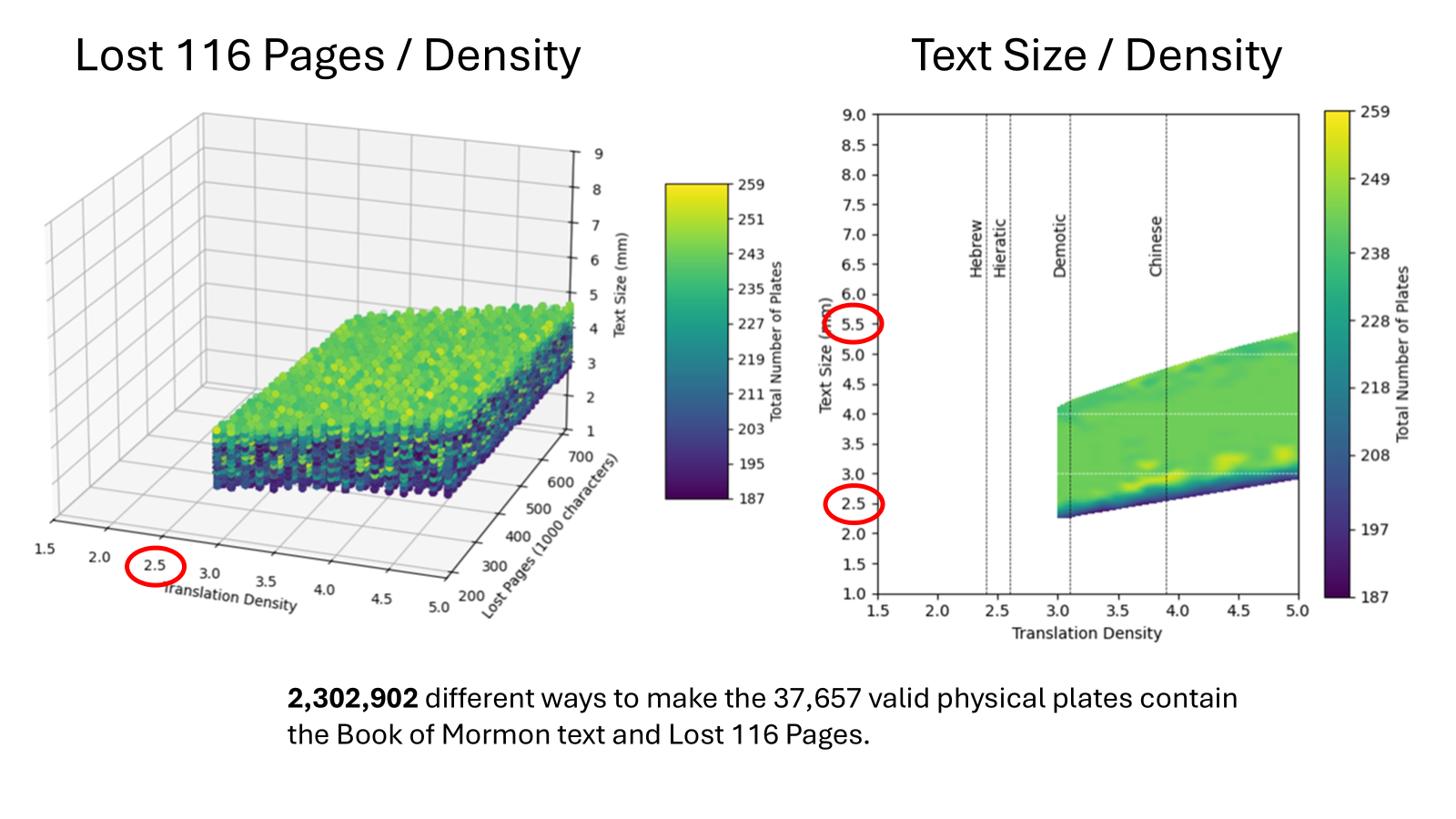

This is what we end up with, guys. This is the result. We end up with 3.5 million different ways to take the Book of Mormon and put it on 37,000 different valid physical plates, including all the different variations of the lost 116 pages.

This is what we end up with, guys. This is the result. We end up with 3.5 million different ways to take the Book of Mormon and put it on 37,000 different valid physical plates, including all the different variations of the lost 116 pages.

These are the two charts. On the left, translation density is one of those axes. And then you’ve got the lost pages’ length as another axis. And then the z axis is the text size. And then again the number of plates required to make this work is the color. So you notice the highest one is 259 plates to make it work. There’s not a lot of yellow there. There’s a little bit. Most of it is in the lower end.

Now if you look at the text size and density, that’s the next chart here. We mostly need two and a half to about 5.5 mm in height.

And by the way, we’re not just dealing with height. This is height by length. And if you look at text, almost every text, whether it’s demotic or hieratic or English, they end up being roughly within 10% square. So text is essentially square if you add the kerning and all the spacing. That’s just what the math ends up being on average.

And then you see those lines, you see Hebrew and hieratic and demotic just to kind of show you the delineations of our examples.

Conclusion: Enough Room for Book of Mormon Text?

All right. Let’s keep going. So can you put enough right in on the valid set of physical plates to hold the entire Book of Mormon? Yes. There are 3 million ways to do this. And it’s nothing weird or unusual. It’s very consistent with ancient writing.

All right. Let’s keep going. So can you put enough right in on the valid set of physical plates to hold the entire Book of Mormon? Yes. There are 3 million ways to do this. And it’s nothing weird or unusual. It’s very consistent with ancient writing.

But Let’s Get More Specific

Okay, we have more to do, right? We want to get a little more specific.

Okay, we have more to do, right? We want to get a little more specific.

We do know the Book of Mormon is like, ‘hey, Hebrew doesn’t work’, right? We needed more plates to put Hebrew, remember? That’s in Mormon. They say that.

What that tells me is that Hebrew is not dense enough, and reformed Egyptian is more dense than Hebrew. We don’t know how much more dense. We just know it’s probably more dense in Hebrew. So let’s go ahead and factor that in.

So we do the calculations again. We end up with 2.3 million valid ways if we chop off everything not as dense as Hebrew. So we chop that off. And then you see that big chop there in our text size density. So now the writing’s shifted just a little bit, but not much.

So we do the calculations again. We end up with 2.3 million valid ways if we chop off everything not as dense as Hebrew. So we chop that off. And then you see that big chop there in our text size density. So now the writing’s shifted just a little bit, but not much.

Accounting for the Lost Pages

Now let’s look at 116 pages.

So to be honest, there’s a lot of different ways to interpret this with a historical record. But if you just look at the scriptures themselves. In the appendix of the paper, I kind of go through my reading of section ten and the Words of Mormon. It sure seems to me that it’s really hard to argue that 116 pages were longer than the small plates. And so that leaves us with, ‘well, they were half the size or maybe the full size’. So that’s what I’m going to go with.

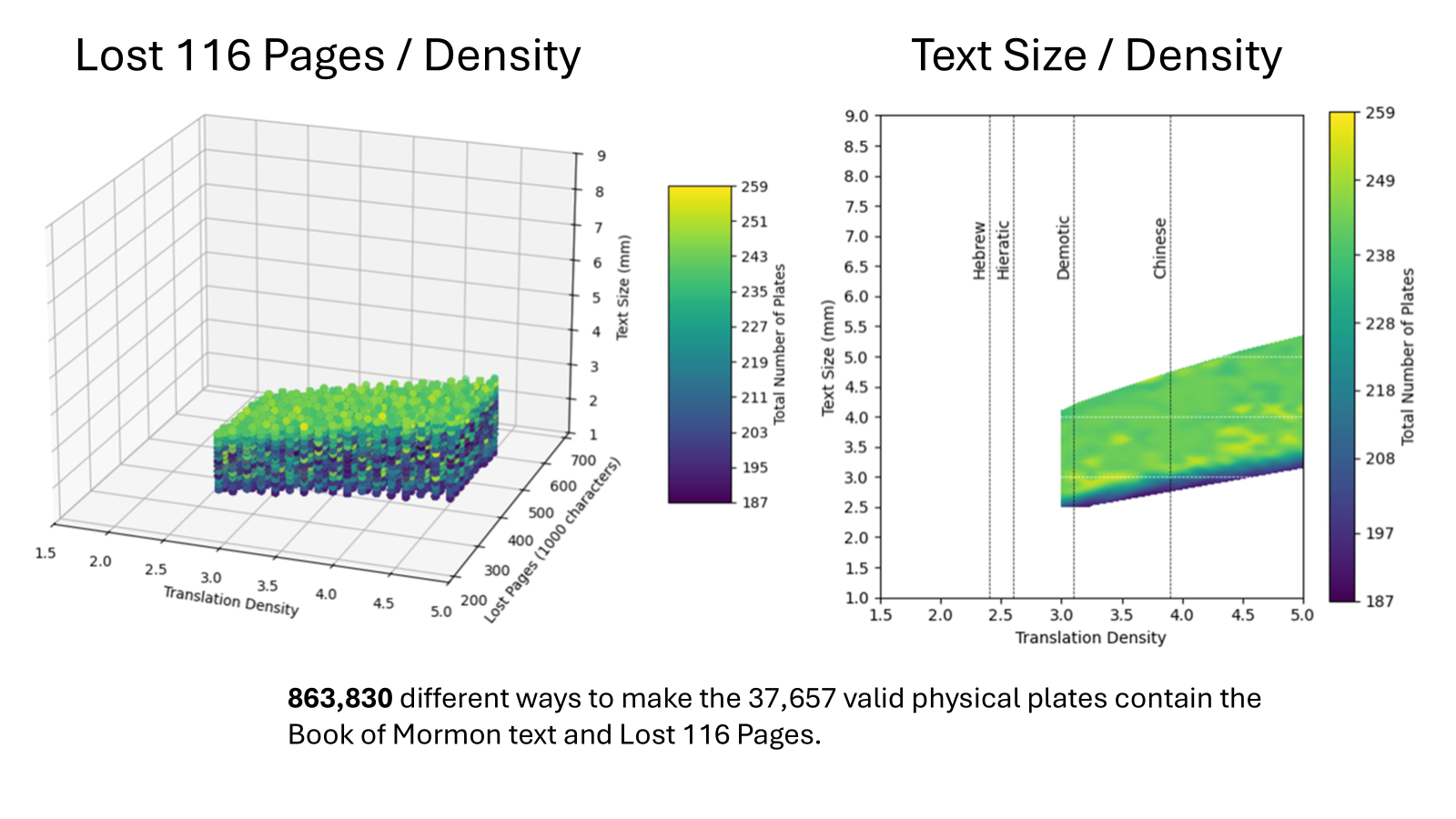

And so that narrows it even more, making it a more conservative estimate. I end up with 800,000 different ways, even with that narrowing, and that’s what they look like.

And so that narrows it even more, making it a more conservative estimate. I end up with 800,000 different ways, even with that narrowing, and that’s what they look like.

This is an example of what, a roughly six by eight size page, in this size of writing. On the right is hieratic. On the left are actually characters from the characters document. They look a lot alike. Like, I think if you put that in front of someone, they’d be like, I don’t know what’s going on. And if you mixed in demotic, then they get really confused.

But that’s what it looks like. If you changed those to like English, it would look like just normal reading book. But that’s the approximate size there.

Hey, you know what? I have talked so fast and gone through this so quickly, we’re going to have time for Q&A.

Conclusion

But here’s the conclusion.

But here’s the conclusion.

Alloy

Basically, the plates had less than 20% gold in them. And if someone says ‘no, no, they had more’, I’d be like, ‘yeah, no, they didn’t, like the math just doesn’t support more than 20%’. Not a big deal because they super duper look like gold. And there’s museums all throughout Central and South America packed full of gold things that actually are only 20% gold.

Weight

They weighed close to 60 pounds. They were not light plates. It’s very difficult to argue that they weighed less than 50 pounds. They weighed closer to 60. Not a big deal because, you know, a young man can heft 60 pounds. It’s not that big of a deal. He’ll just get all tired. And if people are, you know, chasing you in the woods, adrenaline kicks in. You’ll be fine.

Sealed Portion

The sealed portion was about a third. Again, you just can’t make them be a lot more than a third. It just doesn’t work. The math doesn’t work.

Total Plates

The total (number of) plates was somewhere around 200; you know, 230 maybe, 180 maybe, there’s some margin of error. But if someone said, “Hey, how many plates were there?” I’d say, “Well, probably around 200.” That includes the sealed portion. So a third of what we’re seeing there is all sealed up.

Dimensions

Dimensions are slightly less. So this is where Joseph Smith was wrong. He was wrong– I mean, a little bit. He was like within 10% of being right. 6” x 8” x 6” x 0.020”. They were slightly less than that. You really can’t make it work at 6” x 8” x 6”. But he was really, really close. And he didn’t get out a tape measure and measure it. Right? So he was actually remarkably accurate in his estimate.

My Experience Guessing

And in fact, you know, what I did? Well, I was complaining to my wife about this. I’m like, “Joseph was wrong.” And she’s like, “Well, it’s probably really hard to estimate.” I’m like, “How hard could it be?”

And so she picks up the first thing in front of her, which is like a book on the, on the, you know, the little piece of wood that’s next to your bed that you stack books that you don’t read. Yeah. And she picks up a book there and she’s like, “What’s this?” And I’m like, “Oh, well, 5 x 3 1/2 x ¾.” And then we got a tape measure out and I was totally wrong. So I’m like, okay, I’m going to cut Joseph some slack.

Experimenting on Guessing

In fact, I was so interested in this, I actually made three blocks of wood and painted them yellow. And one was 6 x 8 x 6, and the other one was about an inch bigger, and the other one was about half an inch smaller. And I go to people and say, “Here, tell me the dimensions of this.” And everyone gets every single one wrong every single time. Like, it turns out, it’s super hard to guess a three dimensional shape with any precision at all. So that was kind of a fun little exercise. But yeah. So Joseph Smith was really close.

Character Size

The characters were probably between 2 and 4mm in size, about font size 12. Each character represented about 3 to 4 English characters. So it’s very similar to demotic. The ratio of demotic to translated English. Again, this is just the math. This is how the math works. I’m not reading tea leaves. This is just the math.

Just a couple examples of plates there. These are gold, made of tumbaga, 20% gold. Well, these are closer to like 15-16% gold. But yeah, you can make plates.

Just a couple examples of plates there. These are gold, made of tumbaga, 20% gold. Well, these are closer to like 15-16% gold. But yeah, you can make plates.

The Math Doesn’t Prove the Book of Mormon but . . . it’s physically Plausible

So in conclusion, none of this math proves the Book of Mormon, but it shows that the golden plates described by witnesses are mathematically and physically plausible, with sufficient capacity to contain the Book of Mormon text consistent with other known ancient records.

So in conclusion, none of this math proves the Book of Mormon, but it shows that the golden plates described by witnesses are mathematically and physically plausible, with sufficient capacity to contain the Book of Mormon text consistent with other known ancient records.

And, you know, God is real and the Church is true. And I leave this with you in the name of Jesus Christ, Amen.

Q&A

How long did this take?

Scott Gordon: We have a couple of questions for you here. How long did it take for you to do this?

Josh: The math, I don’t know, a couple weeks, I guess, to work through it. I don’t know how many hours that is, but, just a couple. I mean, now that I’ve done it, I could sit down and help someone go through it in an afternoon.

But, you know, I was figuring it out as I was going. And then every once in a while, I’d be like, “Crap, this doesn’t work, the Church isn’t true, right? (Laughter) But then I’d be like, “Oh, whoops, I forgot to carry my one or, you know, whatever.” (Laughter) Yeah. And that I’d be like, “Okay, we’re good, we’re good. Yeah. We’re good.”

Scott: Which is kind of typically the argument people go through I see online a lot: The church isn’t true because . . . .

Josh: Oh, I know. Of course, I’m just kidding. But you know, honestly, I didn’t know. I mean, maybe I’d be backed in a corner where I’d be like, “Oh, maybe the plates were metaphysical.” And I mean, it’s like, fine, fine, if that was true. But it’s really cool that it’s like, oh no, they actually totally work, 100% as a physical object.

What did Joseph say about the sealed portion?

Scott: Yeah. So did Joseph Smith make any statements on the percent that was sealed?

Josh: I’d have to check. I don’t think he ever did. But again, I’d have to look at the appendix and look up who said what about the seal. But if memory serves me, he specifically didn’t give anything particular on it.

Scott: It seemed like he didn’t give a lot of things, like on his translation process or anything.

Josh: He wasn’t like a “Chatty Cathy” about this stuff.

Relationship between character size & translation density

Scott: Any relationship between a given language’s historical character size and translation density?

Josh: You know, that’s a good question. I mean, there might be a relationship. It’s not something I looked at. But I think essentially what they’re asking is, “Do higher density languages tend to be a smaller size or they tend to be a larger size? Does a less dense language have a relationship?” And, yeah, that’s a really good question.

Demotic and hieratic, the samples that I’m familiar with, tend to be written on papyrus or, you know, some sort of nonmetal. And that’s going to change because it is very easy to make large font sizes on paper, much more difficult on metal. So I think that would affect things.

So you’d have to, I think, find ancient languages, enough of an example, on metal, because I think there is a strong relationship between the material they’re inscribed on and the size. But I didn’t do that analysis because it wasn’t relevant to what I was doing specifically.

Accounting for the D-rings

Scott: Here’s an interesting question. What about the D rings on the plates? And should they be a cornerstone of my testimony?

Josh: Oh, yeah, the D rings. Yeah, for the math, I completely ignored them. And I also completely ignored the holes. Someone asked me, what about the holes? I’m like, yeah, okay, I didn’t do the holes. You can go do the holes yourself. It won’t matter. Like I promise. It makes no difference.

The other thing I did is I assumed a 16th inch margin all around the plates for the writing, and some people have asked, well, how’d you come up with that? I made it up. Yeah. I mean, you know, you have to have a margin, and I’m like, 16th.

The D rings, that’s going to add a little bit of weight. That’ll probably add, I don’t know, maybe a third of a pound. I mean it’s not going to change the weight much. Of course it won’t affect the writing at all. So yeah, if you’re locked in on those D rings with your testimony, I have more work to do for you, I guess.

“Nerd”

Scott: Here’s the last question I have, and I think this comes from your wife because it’s a one word statement that just says “nerd.”

Josh: Yeah, that’s probably my daughter, actually. She’s here.

What remains to be researched?

Scott: A couple more questions just came in. What needs further research?

Josh: You know, as far as this goes, I guess, I don’t know. I mean, this was enough to satisfy my itch. I mean, I think the nature of combinatorics is to do every combination. So it’s not like, “Oh, I need to do more.” No, it’s all done. It’s done. That’s the end.

I guess you know what would be cool? And this is not my bag, but if someone said, “Oh, look, I found some more ancient Egyptian type of languages and here’s some more translation density work.” That would be interesting, I suppose.

It wouldn’t change any of the math. But that would be kind of neat, because, you know, that probably took the most time for me because I’m staring at ancient documents, counting characters, or having interns at the B.H. Roberts Foundation count characters, and then word counting, the translations or letter counting, the translation. So I think there could be more research done by linguists.

But again, you don’t need to know the language to do this analysis, because I just don’t care what the translation is. I don’t care about how big the words are. I just want to say, how big is this symbol and how many symbols does it take to create an English translation and how many English symbols is that translation?

All someone needs to tell me is, this is a valid translation. And once they tell me that, I being an ignorant linguist, you know, as far as linguistics goes, I don’t know anything about it–I got like a C-plus in Latin–I just have to count it. Yeah, that’s all I gotta do is count.

What about the size of the box the Smiths hid the plates in?

Scott: Would the dimensions of the plates you calculated fit in the box the Smith family hid them in?

Josh: Well, I think they’ve got that at the Church museum, don’t they? The box? So they don’t let you measure it, it turns out. And trying to measure stuff through plexiglass doesn’t work super well. Based on the estimates, you know, eyeball estimates, yeah. A lot of these configurations could totally fit fine.

Yeah, that’s probably an area of study. It would be cool, but the Church museum’s just going to be like, “Uh, no.”

[Someone from the audience who worked at the museum interjects that they have measured the box at the museum. Their words are somewhat indistinguishable, however]

Josh: Well I’d love to get those measurements because there’s probably several configurations of the plates that could fit in there. And depending on the rings, if you lay them flat, or how high the rings stick out above the plates themselves, which, of course, we know nothing about. So maybe there’s a little more work to be done there. That would be interesting.

Back to the D ring testimony guy: There’s still hope. Or you might have a faith crisis. (Laughter).

Identity of the YouTubers Josh cited

Scott: So the last question, it’s not really a question for you even, it’s about what YouTubers were in the two videos that you showed us.

Josh: Trent Horn and Alex O’Connor. Is that it? Think so. One of them is sort of like a polite and friendly atheist. And the other one is maybe a slightly snarky, hostile Catholic.

But maybe those are just on bad days. I’m sure they’re very fine people. They do a lot of work. They have tons of followers, and I think it’s neat that they have an interest in Mormonism. I think that’s cool.

But on this topic in particular, I don’t know if they’re aware of my research or not, or if they care, but this is, this is a solved problem.

Scott weighs in

Scott: Just to interject my own thoughts on this. I constantly have people saying like, “What non-Mormon scholars do you have to look at?” It’s like, look, they don’t care. So there aren’t non-Mormon scholars that typically look at this stuff.

Josh: No, but if you can get clicks on YouTube, then they’re open to check it out.

Scott: Thank you so much. We really appreciate your time. All right. Excellent job.

TOPICS

Gold Plates

Joseph Smith

Reformed Egyptian

Lost 116 Pages

Translation