Summary

Dan Ellsworth argues that defending the Old Testament requires choosing the right battles: we don’t need to defend inerrancy or rigid interpretations of peripheral “brain-teaser” details, but we should defend core Restoration doctrines and sound, humble ways of reading scripture. It critiques common assumptions in biblical studies and urges Latter-day Saints to recognize worldview and epistemology at work in scholarly claims while also correcting internal misreadings of prophecy that can foster confusion or apostasy.

Presentation

Why the Old Testament Matters in the Restored Gospel

When, as Latter-day Saints, we speak of defending the Old Testament, there are several ways to think about the task. Our first thoughts should focus on the importance of the Old Testament in the restored gospel.

In my case, this is a recent understanding. I count myself among many members of the Church who grew up avoiding the Old Testament in favor of the Book of Mormon and other more reader-friendly works of scripture and commentary. For most of my life, the Old Testament seemed like a pile of frustratingly incoherent puzzle pieces from which I could not easily derive a clear picture. Knowing that the Book of Mormon provides robust summaries of essential Old Testament events and doctrines, I was always happy to defer to it as the path of least resistance for benefiting from the Old Testament.

But some years ago, I underwent a shift. Facing the prospect of teaching the Old Testament in Sunday School, I sensed that if I were going to open that volume and teach from it, I should first have a better understanding of what exactly I was looking at. Many books, lectures, and podcasts later, I settled into a view of the Old Testament that differed from my previous assumptions in important ways. As a result of that learning process, I have undergone a change in perspective about what it means to defend the Old Testament.

Choosing Our Battles When Defending the Old Testament

When it comes to that defense, we would be wise to choose our battles. This means making distinctions between what precisely needs to be defended versus which questions, arguments, and controversies are not our circus and not our monkeys.

There are questions around the Old Testament where flags of firm conviction must be planted.

And there are others where we can be more flexible and neutral.

I begin with something that should bring a sense of relief for any Latter-day Saint looking to defend the Old Testament. I will review a number of items that we should expend no time and effort to defend.

What Not to Defend

The Idea that Scripture is Inerrant or Infallible

First, we do not need to defend the idea that everything in the Old Testament is a divine communication. When we affirm in the Articles of Faith that we believe the Bible to be the word of God “as far as it is translated correctly,” this is best understood as a statement of how the Bible functions.

President Dallin H. Oaks explained the Latter-day Saint position in a 1995 article:

Some Christians accept the Bible as the one true word, completely inspired of God in its entirety. At the opposite extreme, some other Christians consider the Bible as the writings of persons who may or may not have been inspired of God, which writings have little moral authority in our day. The Latter-day Saint belief that the Bible is the word of God as far as it is translated correctly places us between these extremes. But this belief is not what makes us unique in Christianity.

What makes us different from most other Christians in the way we read and use the Bible and other scriptures is our belief in continuing revelation. For us, the scriptures are not the ultimate source of knowledge, but what precedes the ultimate source. The ultimate knowledge comes by revelation.

Scripture as a Vehicle for Revilation

To see scripture as a vehicle for revelation is perhaps the best understanding of what it means for the Bible to be the word of God. The Bible is an offering of ancient peoples who did their best to explain their experiences with God. Like the rest of the world, we have choices in how to receive that offering.

President Oaks referred to extreme views of inerrancy versus skepticism, and we are under no obligation to defend either of those extremes. We can revere the Bible as a sacred offering that has been ordained of God to reveal God’s purposes for humanity without allowing the human processes of production, transmission, and translation to diminish the value of that offering.

Our Personal Mental Models

Second, we do not need to defend all of our mental models of passages in the Old Testament. We recall in the Book of Mormon the moment where Nephi read to Laman and Lemuel from the brass plates, and they responded by asking:

What meaneth these things which ye have read? Behold, are they to be understood according to things which are spiritual, which shall come to pass according to the spirit and not the flesh?

This question reveals that even among ancient Israelites, there was an understanding that it was possible to form different mental models of scripture. In our time, Elder Bruce R. McConkie spoke of elements of the Garden of Eden story as being true in a figurative sense.

The Old Testament was recorded using ancient conventions that modern readers sometimes struggle to understand. Ancient Israelites presented their stories to us using different genres of prose, polemic, allegory, satire, poetry, and more. Utilizing modern scholarship, we can sometimes gain a better sense of the mental models which they held toward the world and the labor of telling their stories. However, even the best scholarly tools will produce inconsistent views of the ancient scriptural past.

On questions such as the exact mechanisms used in the creation or the specifics of the great flood it is fine for us to form our own mental models, but we would do well to hold those mental models as tentative, flexible, and open to revision. To form a rigid viewpoint on a scriptural brain-teaser that is only peripheral to the gospel, and then defend that viewpoint as infallible, is an exercise in misplaced zeal, and it does not advance the cause of the restored gospel.

What We Should Defend: Core Doctrines of the Restored Gospel

Knowing that when it comes to scripture there are some things that do not need defending, we now proceed to the question: What should we defend?

I suggest that a good answer is that we should defend the core doctrines of the restored gospel. In a 2007 commentary on the Church Newsroom website, we read:

Some doctrines are more important than others and might be considered core doctrines. For example, the precise location of the Garden of Eden is far less important than doctrine about Jesus Christ and his atoning sacrifice. The mistake that public commentators often make is taking an obscure teaching that is peripheral to the Church’s purpose and placing it at the very center. This is especially common among reporters or researchers who rely on how other Christians interpret Latter-day Saint doctrine.

In a talk addressed to modern Latter-day Saints, Elder Neil L. Andersen offered an insight about doctrine that I consider to be helpful as we read ancient scripture. He said:

A few question their faith when they find a statement made by a Church leader decades ago that seems incongruent with our doctrine. There is an important principle that governs the doctrine of the Church. The doctrine is taught by all 15 members of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve. It is not hidden in an obscure paragraph of one talk. True principles are taught frequently and by many. Our doctrine is not difficult to find.

The Old Testament is full of what we might creatively call statements by ancient Church leaders. Some of those statements are going to be in harmony with doctrine that has been consistently revealed over time and affirmed by living prophets and apostles in the present day. Others statements might simply represent an ancient writer’s best understanding of a concept in their time.

What We Should Defend

To illustrate, consider Lehi’s epiphany after spending time reading the brass plates:

And I, Lehi, according to the things which I have read, must needs suppose that an angel of God, according to that which is written, had fallen from heaven; wherefore, he became a devil, having sought that which was evil before God.

Think of Lehi’s perspective up to that point. How limited access to scripture had resulted in significant gaps in his understanding of the nature of Satan and opposition in the world. We sometimes assume that the people of scripture understood the gospel like we do today, but Lehi’s experience helps us to see that ancient Israelites’ understanding of God and the world around them was greatly constrained by their lack of access to information.

All of this is to say that in defending the Old Testament, we should exercise caution, focusing on defending concepts in the text that rise to the level of confirmed Restoration doctrine.

What We Should Defend Against

This brings us to the next question. When we defend the Old Testament, what exactly are we defending it against?

Our first instinct might be to see ourselves as firefighters, putting out the fires of criticism set by our detractors.

In 2019, Elder and Sister Renlund offered a different metaphor, that of a game of whack-a-mole, where we are frantically trying to counter a never-ending series of objections to our faith.

Both metaphors are useful. They illustrate that if our approach is reactive, we will never have enough time and energy to defend the faith. It is too easy for our detractors and critics to formulate and repeat objections. And frankly, many in their audiences are in a cognitively shallow space where they are unlikely to ever explore our responses to a helpful depth.

This is not to say that traditional defensive apologetics are not important. They definitely are. But traditional apologetics should also be paired with apologetics that explore problems of bias and worldviews that shape critical views. And apologetics should be accompanied by explorations of basic questions of epistemology which our critics strenuously avoid.

Two Fronts of Attacks

The cause of the restored gospel benefits from defenses of the Old Testament along two fronts.

- The first is external attacks from non-believers.

- The second front is the work of believers, many among us, who misinterpret and wrest the Old Testament text in ways that undermine the truth.

External Attacks

Worldview-Level Attacks (Methodological Naturalism)

Addressing the first front of attack, let’s focus on the field of biblical studies. In biblical studies, the dominant paradigm is sometimes called methodological atheism or methodological naturalism. This means that researchers adopt a set of assumptions about reality that predetermine a set of possible conclusions that do not involve God.

When the Old Testament text claims, for example, that Isaiah saw far into Israel’s future and spoke about it, biblical scholars rule out the validity of that claim in advance. And the decision to rule out that claim is not the product of scientific investigation or any other rational process. It is simply an assumption that scholars consider to be useful.

Theologian Walter Wink expressed the problem when he said that “People with an attenuated sense of what is possible will bring that conviction to the Bible and diminish it by the poverty of their own experience.”

And philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer famously said that “Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world.”

In the use of methodological naturalism, the field of biblical studies imposes an attenuated sense of what is possible in an artificially narrow field of vision upon its participants. Over time, many of them come to believe that the field’s methodological paradigm allows for all that is possible to see.

Zombie Mormon History

Years ago, Alan Goff published a fantastic article in the Interpreter Journal where he referred to “zombie Mormon history.” The basic idea is that when historiography does not account for a historian’s personal factors and does not explore the impact of personal intellectual biases, the historian is operating without the kind of self-awareness that is a prerequisite for any claim to objectivity. Without some training in philosophy, scholars end up with this problem of operating like zombies, following intellectual impulses that they never honestly examine.

Lack of Philosophical Maturity

Philosopher Eleanor Stump spoke of this problem, the lack of philosophical maturity in the field of biblical studies.

Surely some detailed acquaintance with biblical criticism is crucial for understanding the religion one is attacking or defending, and the philosophical examination of Judaism and Christianity will not be done well without some attention to the best contemporary understanding of the biblical texts on which those religions are founded.

On the other hand, however, the final judgment regarding historical authenticity may turn out very differently if biblical scholarship is subjected to analysis and questioning by philosophers. Many cannot survive philosophical scrutiny and bringing philosophical analysis to bear on biblical criticism often alters the historical conclusions which can be justified by that discipline.

When Stump asserts that the findings of the field of biblical studies cannot survive philosophical scrutiny, she is correct. In the field of philosophy, we utilize a number of tools to establish the validity of claims. One of those tools is basic deductive logic. Another is the identification of logical fallacies that weaken or nullify the validity of a claim. And philosophy holds a deeper tool set in the sub field of epistemology that explores more foundational commitments such as scientism and positivism and empiricism that artificially constrain the possibilities of researchers.

Philosophical Maturity

For a good example of lack of philosophical depth in the assumptions held by scholars, consider this statement from biblical scholar Bart Ehrman.

If historians can only establish what probably happened, and miracles by their definition are the least probable occurrences, then more or less by definition, historians cannot establish that miracles have ever probably happened.

The ending statement that “historians cannot establish that miracles have ever probably happened” is true. The tools of historiography cannot establish anything about miracles other than the fact that people through the ages have claimed to experience them. But to frame miracles in terms of probability or likelihood is the wrong way to think about them.

What is Likely vs. Probable

To illustrate why, consider this personal story. Years ago, my young daughter came to me and said there was something on the floor of my home office and it looked like a huge spider. I went to see what she was talking about and I found there, on the floor, a big crawfish. How in the world would a big crawfish appear on the floor of my home office? I do not have an aquarium or a pond containing crawfish and I had not purchased any takeout meals of crawfish. Before that moment, if someone had told me a big crawfish would mysteriously appear on the floor of my home office, I would have said that was not just unlikely or improbable, I would have said it was impossible.

But here are some relevant facts to consider. There is a farm pond a 1/4 mile away from my house and I have a cat named Tiger. Tiger likes to hunt and bring home his trophies. And Tiger has a cat door into my home office.

Tiger is afraid of water, though. So, this is where I was stumped in my quest to reconstruct the journey of the crawfish to my home office floor. But with a little online research, I discovered that crawfish can walk out of their water habitats and move on land, sometimes over surprising distances.

Probability

With this collection of facts, now, is it improbable that a crawfish appeared on my home office floor? In my 20 years of living where I live, this was the only instance of a crawfish appearing on my home office floor. So, on any given day, is it probable or improbable that a crawfish will appear on my home office floor?

There are two ways of answering that question. One is to simply consider how often the circumstances arise that would lead to this thing happening. If that is all we do, we will consider the appearance of the crawfish on my office floor to be improbable.

The other way to answer the question is to consider what was likely to happen with all of the right circumstances in place–with a farm pond nearby out of which emerged a land crawling crawfish, and a cat in the area who was roaming and hunting and eager to bring home a trophy. All of a sudden, the appearance of the crawfish on my home office floor was not improbable at all. It was more or less inevitable.

Blanket Statements About Miracles

This explains why it is simply poor quality thinking to make a blanket statement that miracles are probable or improbable. Miracles happen or they do not happen. I speak from personal experience in affirming that they do. And if I am right, then the likelihood of a miracle in any given instance is a question of conditions and circumstances that lead to it happening or not.

For people with direct personal experience of miracles, there is no question that they happen. So most of our discussion around miracles focuses on creating the right conditions and circumstances for miracles to become increasingly more possible in the world around us.

Latter-day Saint scholar Phil Barlow offered this insight.

. . . some critics steeped in modern assumptions may exceed necessary critical thought by too facilely discounting the witness of earlier generations as self-evidently a product of wish fulfillment. Rather than suspending judgment, they may start with the post enlightenment assumption that miracles–say the resurrection–cannot have happened because such things do not happen. No one they respect has witnessed one.

Paradigm Differences and Projection

Assumptions

This tendency to assume that our mental horizons are the only possible mental horizons goes beyond the question of miracles into questions around authorship. Consider these two statements that are typical of claims that we read in biblical scholarship.

- “These verses were inserted by a later author. They were not written by Jeremiah himself.”

- “This chapter reflects a shift in thinking and therefore could not have been written by Isaiah.”

Now consider those two statements but with the addition of a frank acknowledgement of the scholar’s personal perspective.

- “These verses were inserted by a later author. They were not written by Jeremiah himself. This is obvious to me as they do not reflect what I personally would have said if I were in Jeremiah’s situation.”

- “This chapter reflects a shift in thinking and therefore it could not have been written by Isaiah. I know this because I personally have never undergone this kind of a shift in my thinking, and therefore I cannot accept that Isaiah did.”

Both of these revised statements expose the undeclared baggage of paradigm that pervades the claims of biblical scholars. They have an understanding of what they would do if they were an ancient prophet or scribe. They then work backwards from those paradigm level assumptions. And as they analyze textual and historical data, they make decisions around evidence that reflect and affirm their paradigms.

Paradigm and Projection

Biblical scholar Robert Funk made a refreshingly honest statement about his field when he said “Methodology is not an indifferent net. It catches what it intends to catch.”

This is not a bad thing when we have good reasons to catch a particular thing. For example, in much of the book of Romans, we witness the Apostle Paul’s personal shift in methodology from a non-Christian interpretation of scripture to a new Christian interpretation of scripture. Having become an eyewitness of the risen Christ, Paul was now compelled to change his methodological net to catch new principles and concepts that were more aligned with reality.

But it is also possible to create methodological nets that catch and affirm delusions.

Assertion vs. Conculsion

For example, biblical scholar Steven McKenzie said:

The intent of the genre of prophecy in the Hebrew Bible was not primarily to predict the future, certainly not hundreds of years in advance, but rather to address specific social, political, and religious circumstances in ancient Israel and Judah. This means that there is no prediction of Christ in the Hebrew Bible.

This statement is an example of some of the poor quality reasoning that we often find in biblical studies. McKenzie is offering a naked assertion here, not a conclusion derived from scientific or other objective analysis, but he presents it as a self-evident fact, when in reality all he has shown in this statement is a glimpse of his arbitrarily chosen methodological net. And undoubtedly his net catches exactly what it intends to catch, a de-Christianized Old Testament.

McKenzie’s methodological net differs from that of the Apostle Paul because Paul had personally witnessed some realities that McKenzie has not.

Another Example of Methodology Leading to Delusion–BofM Provenance

As another example of methodology leading to delusion, think of the field of Mormon studies and its numerous contradictory conspiracy theories around the provenance of the Book of Mormon.

- One theory holds that the Book of Mormon was the product of a process of automatic writing.

- Another theory claims it is the product of plagiarism from numerous sources.

- Another claims it was authored by people around Joseph Smith.

- Another claims that it was the product of psychedelics and more.

Similar to what we find in the field of biblical studies, the problem for the field of Mormon studies is that only one of their theories can be true. This means that with each of these theories, a scholar or researcher fashioned a methodological net that was intended to catch their chosen narrative and ignore or refute other rival narratives.

Again, since only one of these conspiracy theories can be true, if there are six conspiracy theories around the provenance of the Book of Mormon, and we pretend for the sake of argument that one of them is true, that means five of them are delusional.

If those five delusional theories have been produced by credible scholars casting methodological nets that use sound argumentation and rigorous scholarly evaluation of sources, then it follows that in most cases this robust scholarly tool set is used by historical critical scholars to give academic respectability to their delusional narratives of history.

In fact, we might say that often historical critical scholarship is used as a tool set for alleviating the intellectual discomfort of the scholar.

Incoherent Claims of “Evidence” and Tunnel Vision

For people like me who follow true crime podcasts, there is a phrase used in criminal investigations and it is “tunnel vision.” The basic idea is that when investigating a crime, people carry a tendency to zero in on a narrative of events early in the process, which excludes a number of other viable possibilities for investigation.

If an indictment emerges from an investigation plagued by tunnel vision, it is likely to result in acquittal, as a defense attorney operating free of the investigator’s tunnel vision, will have the ability to present the jury with other plausible narratives of the crime.

Example: Criminal Investigation

Imagine, for example, a criminal investigation where DNA and fingerprints are found on a weapon early in the investigation. In this case, we assume the case has been solved definitively and everything about the crime scene and a hundred other relevant facts are justifiably seen as evidence for the narrative.

But suppose later in the investigation, it becomes clear that the weapon had been stolen and used by an individual who wore gloves to hide their own fingerprints and DNA. And security cameras show that the initial suspect had been shopping in a store at the time the crime was committed. And the second suspect offers a full detailed verifiable confession.

Now all of a sudden everything observed at the crime scene and all of the other facts gathered by investigators are no longer seen as evidence of the first narrative. They are now seen as evidence for the second and final narrative.

Intellectual Whiplash

When these kinds of reversals occur in true crime podcasts, listeners like me experience a kind of intellectual whiplash. The field of biblical studies is full of intellectual whiplash.

Reading early and mid 20th century studies on the authorship of the Pentateuch, we might see the voluminous evidences marshaled by researchers and conclude that the documentary hypothesis is a decisively established fact, the only possible explanation for the formation of that part of the biblical text.

But reading biblical scholarship from later in the 20th century and beyond, we are likely to experience intellectual whiplash as we see how thoroughly more recent scholars have dismantled the arguments of their predecessors.

Or in an example more relevant to those of us who believe in the historicity of the Book of Mormon, if we were to spend time reading scholars who have imagined multiple authors and textual divisions in Isaiah chapters 40-66, we might experience intellectual whiplash reading scholars like Shalom Paul or Benjamin Summer who have amassed extensive “evidences” that establish single authorship for all of those chapters.

Claims of Evidence

Consider these statements from Benjamin Sommer.

Was there in fact a third Isaiah or perhaps several third Isaiahs? It seems to me that no convincing evidence has yet been marshaled to demonstrate such a thesis.

The even distribution of these thematic and stylistic features in Isaiah 35 and 40-66 is highly significant. It suggests that a single author wrote all these chapters relating to older texts in a consistent fashion throughout.

Now consider the views of scholar Hugh Williamson responding to Benjamin Sommer.

A work as stimulating as this deserves a much fuller evaluation than can be offered here. I must therefore restrict myself to just two initial reactions. In the first place, there is a danger (and Sommer is by no means alone in falling for it) that discovery of some new data may blind the critic to the force of other considerations which need to be kept alongside it. The critical conclusions which he rejects have been achieved over a long period of time and on the basis of many converging lines of evidence.

Here are two scholars who both possess what is considered to be the best possible training in the tools of the field of biblical studies and yet they cannot agree on basic questions of evidence. Why not?

Not an Indifferent Net

Repeating the insight of Robert Funk, “methodology is not an indifferent net. It catches what it intends to catch.” These two scholars intend to catch different things. So they have fashioned different methodological nets.

The reality of the field of biblical studies might be summarized as this. Anytime you read mainstream peer-reviewed studies in that field, you are reading narratives of cultural context of authorship of authorial intent and more. Most of the items of “evidence” in support of those narratives have been discussed by numerous other scholars in the field who have either refuted those items outright or have presented them as evidence in support of a different narrative that is in conflict with the one you are reading.

When you look at the long rows and tall shelves full of books in your university library’s Biblical Studies section, you are seeing an enormous amount of well researched, well documented, rationally argued claims that few or no people in that field believe to be factually true.

Misunderstandings of the Nature of the Biblical Studies Field

And that is because most of the output of the field of biblical studies is not produced with the aim of establishing what is factually true.

To be sure, some things in that field can be said to be true in a definitive way. Biblical scholars can make objective claims about, say, the number of times a particular Hebrew verb is used in the Maseretic text rendition of the book of Micah or the characters and images on an ancient artifact. Those are objective facts which cannot be rationally disputed.

But most of the output of the field of biblical studies is not of that kind. Most of the output of the field of biblical studies is analysis that reflects any number of subjective judgments that are informed by worldview and other personal factors.

Biblical scholar Michael Legaspi frankly describes his field as “best understood as a cultural political project shaped by the realities of the university.”

I repeat, it is a naive mistake to think of the field of biblical studies as an enterprise that is trying to tell us what is true about the Bible.

Scholars Playing a Game

Compare the field of biblical studies to a game being played by scholars. When an article passes the process of peer review for a journal in biblical studies, that does not mean that the peer reviewers believe the article’s contents are correct. Their approval means that they believe the article conforms to the rules of the game of biblical studies as understood and applied by that particular journal.

And just like different basketball leagues have different rules, different academic journals, publishing houses, and university biblical studies departments hold to different sets of rules in the game of biblical studies.

By now it should be clear that objectivity cannot be a rule of the game of biblical studies. But in case that is not clear, consider what biblical scholar Jacque Berlinerblau said of his discipline.

Defending Against External Challenges

The unspeakable that I allude to in my title concerns what we might label the demographic peculiarities of the academic discipline of biblical scholarship. Addressing this very issue 30 years ago, M. H. Goshen-Gottstein observed, “However we try to ignore it, practically all of us are in it because we are either Christians or Jews.”

In the intervening decades, very little has changed. Biblicists continue to be professing (or once professing) Christians and Jews. They continue to ignore the fact that the relation between their own religious commitments and their scholarly subject matter is want to generate every imaginable conflict of intellectual interest. Too, they still seem oblivious to how strange this state of affairs strikes their colleagues in the humanities and social sciences.

. . . What results is a situation in which biblical scholarship’s secular wing is more like a reformed religious or liberal religious wing.

Exiting Objectivity

Of course when Berlinerblau mentions the problem of conflicts of intellectual interest, this is not a problem when, for example, a scholar is counting usages of a particular phrase in the Septuagint book of Genesis. Those usages are simply data. But when a scholar decides that those data are evidence of a narrative about those data, we exit the realm of objectivity. A scholar’s background, worldview, and any number of other personal factors will steer the scholar’s adoption of that narrative over a different narrative held by other scholars who have similar training.

The Old Testament presents ancient Israelites narratives of their history. And when a modern scholar comes along and claims to be able to give you an objective view of what really happened instead, it is obvious that the field of biblical studies is simply not equipped to offer that in a reliable way.

When the reliability of the Old Testament is challenged from secular corners like the field of biblical scholarship, we would do well to assess whether the battle is worth fighting, whether anything of real doctrinal value is at stake. If it is, then we should examine the methodology and the irrational biases or “isms” like naturalism and positivism that shaped the weapon of attack. We should examine the choices in epistemology that constrain our opponent’s views.

Misunderstandings of the Nature of the Field

What Christian philosopher Peter Van Inwagen said of New Testament scholarship applies to biblical scholarship as a whole.

First, ordinary Christians, Christians not trained in New Testament scholarship, have grounds for believing that the gospel stories are essentially historical–grounds independent of the claims of historical scholarship. Secondly, New Testament scholars have established nothing that tells against the thesis that ordinary Christians have grounds independent of historical studies for believing in the essential historicity of the gospel stories. Thirdly, ordinary Christians may therefore ignore any skeptical historical claims made by New Testament scholars with a clear intellectual conscience.

This argument is sound and it helps to clarify our grounds for belief. For example, most of our core doctrines are supported to some degree by direct modern witness testimony from prophets and ordinary saints.

Sports as a Comparison

Therefore, when our opponents make subjective epistemic choices to exclude restoration witness testimony, our efforts to defend or persuade end up playing out like a baseball team trying to score a home run on a soccer field. Different choices in epistemology leave us playing fundamentally different games on different kinds of fields with different rules and objectives. When we really understand the various games being played in the arena of biblical studies, we are equipped to make better assessments about the real quality of its claims.

After we adjust the field of biblical studies for inflation, so to speak, I suggest that very few of its narratives amount to credible attacks on the restored gospel.

Internal Attacks: Misinterpretation by Believers

Having addressed the first front of external attacks, let us move on to the second of internal attacks. How do we defend the Old Testament from poor interpretation by fellow Latter-day Saints?

Conceptual vs. Other Forms of Revelation

A good rule of thumb is to hearken back to the principle that Laman and Lemuel had internalized from their own religious upbringing. It is the principle that prophecy can be interpreted in ways that are literal and observable or in a conceptual way. What Laman and Lemuel referred to as being fulfilled “according to the spirit.”

Recall Ezekiel’s vision of a field of bones. In that vision, Ezekiel is shown a valley full of many bones, and he is commanded to prophesy upon them. Ezekiel prophesies their resurrection, then witnesses its fulfillment before him. He is then told that the bones are the entire house of Israel.

An erroneous interpretation of this passage could lead us to undertake a search for the specific valley of bones. We might form teams of experts combing the Levant for the site and making theoretical calculations about what quantity of bones the field would contain if it were all the house of Israel. Of course, that would be preposterous.

A Conceptual Level

In Ezekiel’s vision, it was represented to him the reality that physical resurrection is part of God’s plan for the restoration of his covenant people. And this was represented to him on a conceptual level. The vision had the purpose of conveying to Ezekiel the concept of resurrection in a way that he could understand. And the particulars of the fulfillment of this prophecy are not something that we should try to attach to a specific single moment and location in the future.

If we can understand that the Old Testament contains some prophecy intended to be conceptually interpreted, we can avoid any “doubtful disputations.” These contentious and pointless brain teaser battles tend to arise when we lack humility about our interpretations.

Defending the Old Testament involves proactively teaching the humble and careful interpretation of prophecy.

Applicability Is Not the Same as “About Us”–Misinterpretation

A final front of defense is to understand that much of Old Testament prophecy has applicability to us, but that does not mean it is about us.

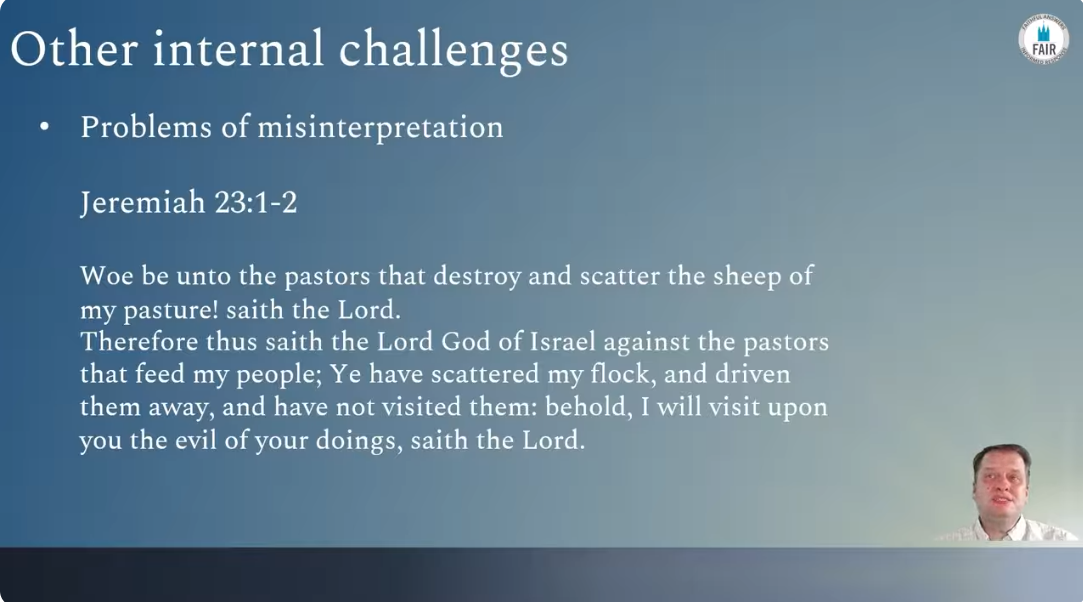

To illustrate why that is important, consider a recent conversation I had with an individual who referred me to Jeremiah 23’s condemnation of wicked pastors.

Woe be unto the pastors that destroy and scatter the sheep of my pasture! saith the Lord.

Therefore, thus saith the Lord God of Israel against the pastors that feed my people; Ye have scattered my flock, and driven them away, and have not visited them: behold, I will visit upon you the evil of your doings, saith the Lord.

In our conversation, this individual told me that according to this passage, our current First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles are under condemnation from God.

I replied to him that no, this passage is not referring to our current Church leadership. It was a statement made toward ancient Israelite spiritual leaders. The principles in Jeremiah 23 might have some general applicability to a number of situations through the ages, but when Jeremiah gave us this passage, he had his time and context in mind, not ours.

Other Internal Challenges

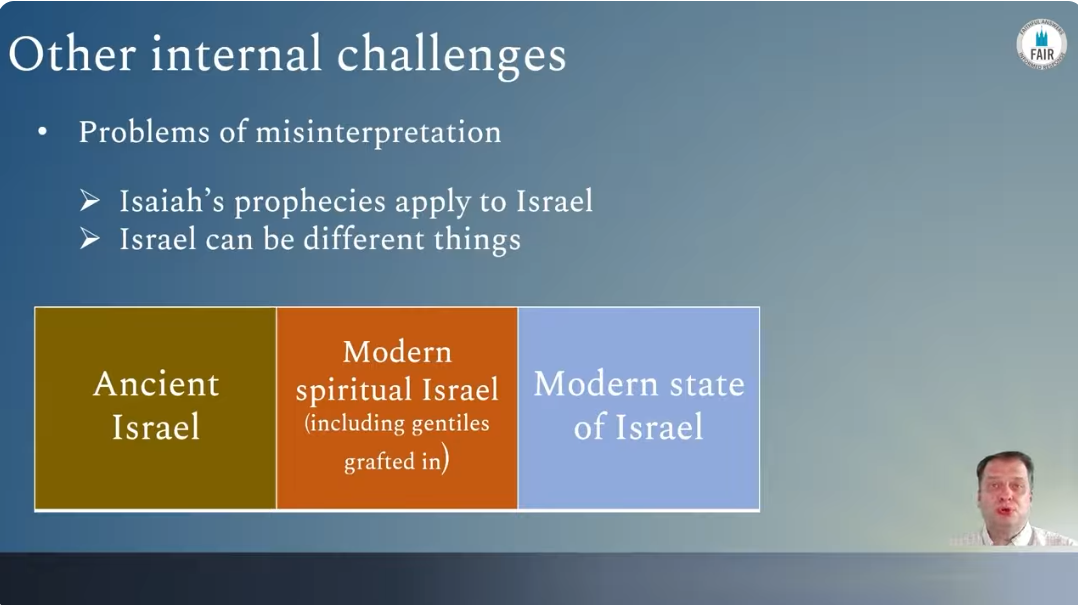

Similarly, disaffected Church members often use passages from the Book of Isaiah in an attempt to give some kind of authority to their own personal murmuring toward current Church leadership.

The Book of Mormon states that Isaiah prophesied to all of the house of Israel. And this is sometimes erroneously interpreted to mean that every passage in Isaiah is somehow about us. That is not true.

Some passages in Isaiah have direct application to our time and context, while other passages do not apply. Instead, they convey general patterns and principles that all of the House of Israel can apply to their own time and context using wisdom and discernment.

Defending the Old Testament means being aware of how misinterpretations and misapplications of Old Testament prophecy can lead to apostasy, and inviting those that misunderstand to adopt better interpretations that lead to sustaining God’s ordained servants today.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is my hope that this presentation can help Latter-day Saints to critically think through our defenses of the Old Testament. Specifically, what aspects of the Old Testament we ought to defend and the nature of the attacks that believers are likely to encounter in our day.

When Latter-day Saint understanding and defenses of the Old Testament bring us into conflict with the field of biblical studies, our attention to foundational questions of worldview and personal factors and our willingness to forthrightly articulate how those influence our own perspective give us an opportunity to model honesty in those disagreements.

- To defend the Old Testament is to defend scriptural texts that formed the basis for the religion that Jesus adhered to in mortality.

- To defend the Old Testament is to defend the prophetic mantle.

- To defend the Old Testament is to defend the value of ancient Israel’s sacred offering of scripture to the world.

And to defend the Old Testament carefully, intelligently, with wisdom, maturity, and discernment is to defend the restored gospel.

Thank you.