Summary

TL:DR

Old Testament covenants with Noah, Abraham, and Moses are not static agreements but living relationships whose meaning unfolds over time. Scripture repeatedly expands and reinterprets these covenants to meet God’s purposes in each dispensation. In the Restoration, Joseph Smith continues this scriptural pattern—not by inventing new covenants or merely reviving ancient ones, but by expanding their meaning through modern revelation, temple ordinances, and covenant living for today’s Saints.

Why This Matters

If you’ve ever wondered whether modern Latter-day Saint covenants feel different from what you see in the Bible, you’re not imagining things—and that difference doesn’t mean something has gone wrong. Scripture itself shows that God has always taught His people through covenants whose meaning grows and deepens over time.

The Restoration fits that same pattern. Rather than being a break from biblical faith, modern covenants reflect God’s consistent desire to meet His children where they are and patiently shape them into a covenant people. Doubt doesn’t mean you’re outside the story—it may mean you’re engaging with it honestly.

Introduction

Introduction

Jennifer Roach Lees holds a masters degree in Divinity as well as a masters in Counseling Psychology. She’s best known for her research into how the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints handles cases of sexual abuse. She’s spoken at the annual FAIR conference on this topic, as well as the dynamics involved in bishops interviewing teenagers alone. Jennifer is a licensed mental health therapist and lives in Utah. She is also co-host of the Me, My Shelf, and I podcast, and does other podcasts for FAIR.

Presentation

I am Jennifer Roach Lees. This is my paper From Sinai to Salt Lake: Sacred Promises Reimagined for a New Dispensation.

Restoring Lost Truths

“I have a work for you to do.”

I am Jennifer Roach Lees. This is my paper From Sinai to Salt Lake: Sacred Promises Reimagined for a New Dispensation.

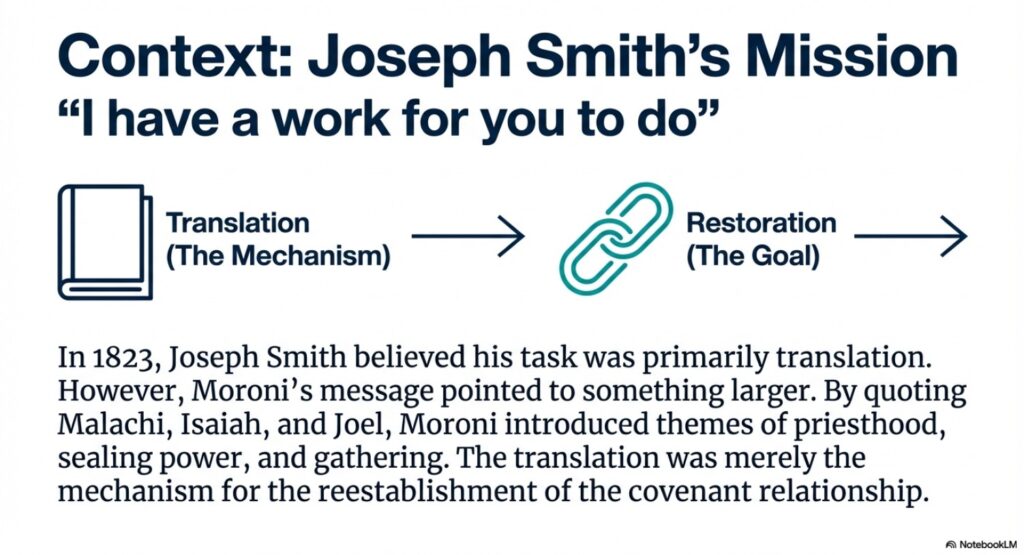

The instructions Joseph Smith received from Moroni in 1823 were primarily centered on the translation of the gold plates. The angel describes the plates, their location, their accompanying interpreters, and the divine purpose behind their translation. Joseph was told that he must not seek the plates for personal gain, but rather to fulfill God’s work.

The bulk of these conversations should be understood as the angel giving instructions to Joseph about how he was to begin his prophetic career and bring forth the Book of Mormon. But it also marked the beginning of his role in restoring lost truths.

This was communicated to Joseph when Moroni quoted passages from Malachi, Isaiah, and Joel—scriptures that speak of the priesthood restoration, the sealing power of Elijah, and the gathering of Israel. These references pointed beyond just translation of scripture to a broader divine agenda: the reestablishment of sacred covenants between God and His children.

Covenants and the Restoration

The Book of Mormon, just like the Bible, is saturated with covenant language—promises of land, prosperity, divine favor that’s contingent on obedience, and others. Thus, while the immediate task was translation, the ultimate goal was restoration: priesthood authority, temple ordinances, the covenant path, and all that would prepare us for Christ’s return.

When Heavenly Father spoke through the angel Moroni and told Joseph, “I have a work for you to do,” He meant far more than a translation project. Joseph didn’t know it yet, but translating the Book of Mormon was to go hand in hand with restoring the relationship between God and His children through covenants.

Covenants in Joseph Smith’s Day

So, what do we know about Joseph’s understanding of covenants? What were covenants like in Joseph’s day?

Well, in the early nineteenth-century context, most Christians—especially those involved in Protestant traditions—would have had a very strong conceptual framework for understanding covenants, often through a theological lens shaped by the Reformation or by proto-evangelical thought.

Charles Spurgeon, an incredibly popular minister during Joseph’s day, said:

There is no more blessed way of living than a life of faith based upon a covenant-keeping God. To know that we have no care, He cares for us, and we have no need to fear, except to fear Him, and we have no troubles because He has cast our burdens upon the Lord, and our conscience that He will sustain us.

Additionally, many Christians would have understood covenants as binding spiritual agreements that would have involved both divine promises and human responsibility.

Presbyterian clergyman Lyman Beecher put it this way:

The covenant of grace is not a cold contract, but it’s a living bond. He who enters into it must walk upright before the Lord, for the promises are only to the faithful.

Baptism and communion were seen as signs or seals of covenant membership. Sermons in that day frequently emphasized the importance of keeping one’s covenants with God through moral living and personal conversion.

Covenant Language and Religious Memory

While the theological vocabulary certainly varied across denominations, the idea that God relates to His people through covenants was deeply embedded in the religious imagination of Joseph’s day.

He was not inventing a new concept—the concept of covenants. He wasn’t even introducing it for the first time. Rather, Joseph was restoring aspects of making covenants with God that had been lost.

Latter-day Saints and Ancient Scripture: Searching for Covenant-Making

However, confusion sometimes arises for Latter-day Saints when they turn to the Old Testament, or even sometimes the Book of Mormon, hoping to find specifics about the practices of covenant making in those ancient texts.

One young missionary recently said, “Hey, I’m here working to help people onto the covenant path. The first covenant is baptism. I can easily go to 2 Nephi 31 to see the origin of baptism. But where can I go to find the other covenants that we make?”

This elder really wanted to be pointed to a specific passage where he could see the origins of covenants that involve the laws of obedience or of sacrifice, the gospel or chastity, the law of consecration.

And certainly, scriptural support can be found for concepts behind those covenants, but we don’t see the actual wording of those covenants as we know it today found in the Book of Mormon, in the Doctrine and Covenants, or in the Old Testament.

Alma the Younger instructs his son Corianton about the law of chastity, but they are not sitting in a temple making a formal covenant when he does so. The concepts are there. The exact covenant formation isn’t.

Is This a Problem?

So, is this a problem? Should modern Latter-day Saints be concerned that the covenants we consider to be restored ancient truths are not presented in scripture in the same way that they are today?

To address this concern, this paper is primarily concerned with demonstrating that the covenants found in the Old Testament are not one-time static events intended only to be understood one way and never again reinterpreted.

Rather, they are continually evolving in their meaning and renewed in subsequent contexts.

In a similar way, the Restoration is not a carbon copy of some ancient point in time, but it’s a rearticulation of eternal principles for today’s Saints.

When Joseph Smith restored covenants, he was not introducing something new. The idea of covenants already existed in his day. He was recontextualizing them for a deeper meaning.

The Major Covenants of the Old Testament

The Old Testament presents four major covenants, and they’re each named after the prophet or leader involved: Noah, Abraham, Moses, and David.

We’re going to deal with the first three in this paper. David should be saved for another paper.

Those living in the times of the Old Testament—and those reading it during the New Testament era—would have understood the word covenant to refer to those four covenants.

The Noahic Covenant

So we’ll start with Noah.

Established in Genesis 9, the Noahic covenant represents God’s enduring promise to all living creatures following the great flood. After Noah and his family exit the ark, God pledges to never again destroy the earth by flood. The sign of this covenant is the rainbow set in the clouds as a visual testament to His mercy and faithfulness.

A unique feature of this covenant is that it is a one-way covenant. It’s not based on their faithfulness. The Lord makes a promise to humanity, and the promise is His to keep alone. It really does serve as this kind of foundational moment in biblical theology. It illustrates God’s grace and commitment to preserving life despite human fallibility.

Expanding Meaning in Later Scripture

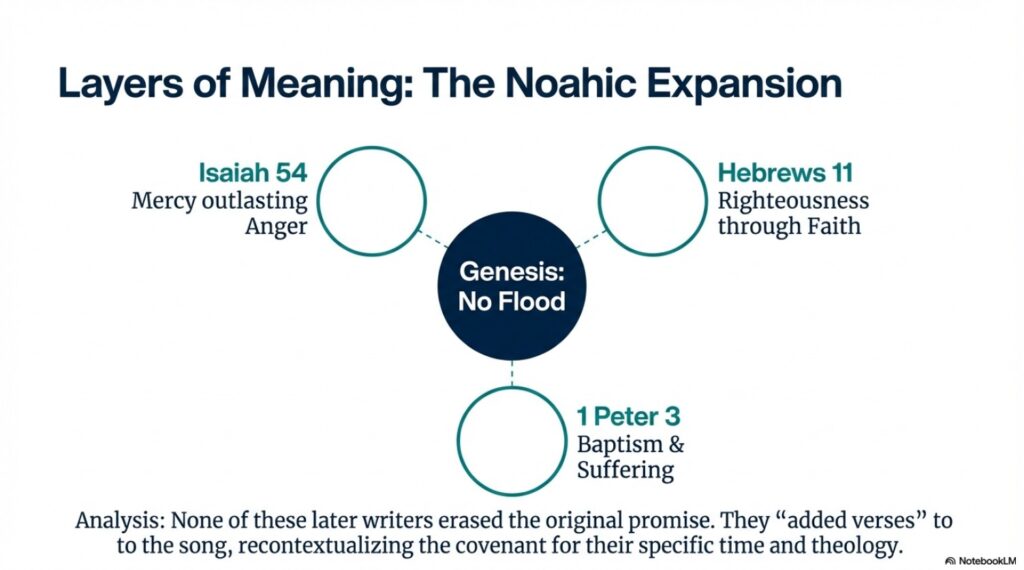

While God is true to His promise never to flood the earth again, the theme would reemerge in later scripture. If we fast forward all the way to Isaiah 54, God is speaking words of reconciliation to Israel over His previous anger with them. The people had persisted in their disobedience and idolatry, and God had expressed His anger to them.

In verse 9, the Lord says, “For this is as the waters of Noah unto me. For as I have sworn that the waters of Noah should no more go over the earth, so have I sworn that I would not be wroth with thee, nor rebuke thee.”

So while the initial covenant had to do with the physical condition of the earth—I will not flood the earth again—here God expands it to include the idea of His anger flooding over them.

The Covenant Continues to Evolve

And then we see it again. It continues to evolve. Fast forward all the way to the New Testament in Hebrews 11:7. Noah is praised for his faithfulness. Here, this covenant is way less about God’s promises of mercy, but now it’s about how Noah gained righteousness by participating in this covenant.

Hebrews 11:7: “By faith, Noah, when warned about things not yet seen, in holy fear, built an ark to save his family. And by faith, he condemned the world and became an heir of the righteousness that is in keeping with faith.”

How interesting. All of a sudden, it’s not about the physical condition of the earth or even about God keeping His covenants. The meaning continues to morph and evolve.

Baptism, Suffering, and New Creation

First Peter 3 provides an entirely different take on the meaning of covenant. The Apostle Peter explained that the flood was like a baptism for the whole earth. He sees it as a fresh start for all of humanity, and he leverages it into a call to righteous living.

Peter appeals to the suffering of Christ and implores his readers to willingly take on suffering that may come as the result of following the Savior. For Peter, the covenant associated with Noah is about accepting what is given to you in baptism and choosing to live differently because of this grace, even though it will cause suffering.

As you can see, at different times in scripture, different emphases have been put on the meaning of the Noahic covenant.

Layer upon Layer of Meaning

Sometimes it’s about a literal flood of the earth. At other times, it’s about the Lord promising His mercy will outlast His anger. On some occasions, it’s about obedience bringing righteousness, or about accepting suffering just as the Savior did.

Each time a scriptural writer talks about this covenant, they’re not trying to erase the previous meaning—they’re adding to it. The covenant does not change with each additional passage; rather, it is expounded upon.

Joseph Smith and the Restoration of Covenants

So we return to our question. What was Joseph Smith doing when he restored the idea of covenants?

As shown, the idea of covenants was already well established in his lifetime. When Joseph spoke about covenants, he was speaking to an already well-established understanding of them. But when the Lord spoke of the Noahic covenant in Isaiah 54, He was also speaking into a well-established idea about what the Noahic covenant meant.

The people of Isaiah’s day would have easily retold the story of Noah and provided appropriate commentary on the meaning of that covenant—until the Lord speaks through Isaiah and offers additional meaning.

Adding New Verses to an Old Song

Fifteen hundred years later, God brings up the covenant again and adds more meaning to it. Seven hundred years after that, in the New Testament, we get more additional meaning from Peter and the writer of Hebrews.

No one living in Israel prior to Isaiah would have articulated that the Noahic covenant was about the relationship between God’s mercy and His anger, or that it was about baptism or righteous living. They would have expressed the original meaning: that the covenant was about the Lord promising to never flood the earth again.

But the meaning of the covenant did not stay static. God is adding new layers of nuance as the circumstances of His children demand. It is as if the Lord is writing new verses to an old song—the same tune, but with additional and expanded meaning.

Restoration as Living Revelation

So when the prophet Joseph Smith begins talking about the restoration of covenants, we still have to ask what was being restored. Is it simply that Joseph discovered some old text, dusted it off, and called it a restoration? It does not appear to be the case.

Instead, Joseph is participating in this grand tradition in scripture. He allows God to use him to add a new verse to an old tune.

While God has certainly established His covenants in scripture, He continues to speak in our day and brings layers of new meaning to these promises. Joseph Smith is not simply restoring old covenants; he’s helping to co-create and expand them.

It is my meditation all the day to know how I shall make the Saints of God comprehend the visions that roll like an overflowing surge before my mind. Oh, how I would delight to bring before you the things you never thought of.

—Joseph Smith

The Abrahamic Covenant

We’ll move on to the Abrahamic covenant.

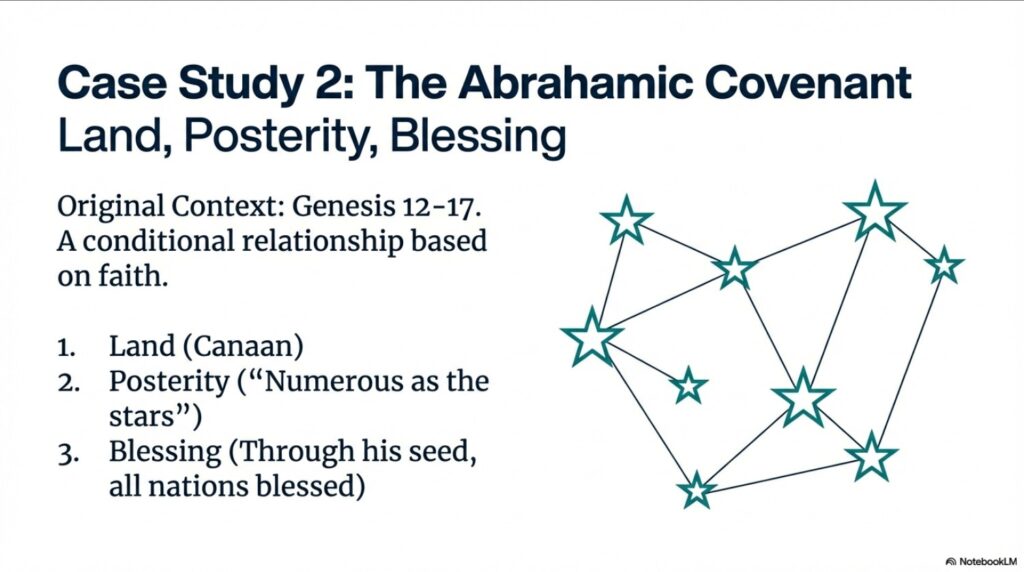

It’s introduced in Genesis 12, and it’s expanded through chapters 15 to 17. We’ve got a lot of scriptural real estate text about this. The Abrahamic covenant marks a very pivotal moment in biblical history. God initiates a lasting promise not just with Abraham, but with his descendants forever. And it has three core components.

- The promise of land—the land of Canaan.

- The assurance of posterity, especially as it relates to the coming generations for him—his posterity—they will be as numerous as the stars.

- The declaration that through Abraham’s seed all nations of the earth shall be blessed.

Land, posterity, blessings for all the world.

This covenant is conditional and involves Abraham’s faith and obedience, and it’s everlasting, forming the theological backbone for Israel’s identity and destiny. It also establishes a relationship not just based on divine favor, but on mutual commitment.

Expanding the Abrahamic Covenant

And just like with the Noahic covenant, over time we see the Abrahamic covenant expanded in scripture. The details of those expansions are very, very numerous—more numerous than the covenant with Noah—but we will address a few in this paper.

For we see the same idea: God is adding a verse to the song where the meaning of the covenant is added to and expounded upon. Perhaps this covenant, more really than any other, illustrates the work which the prophet Joseph Smith was doing to both restore and expand.

Restoration Compared: Joseph Smith and Alexander Campbell

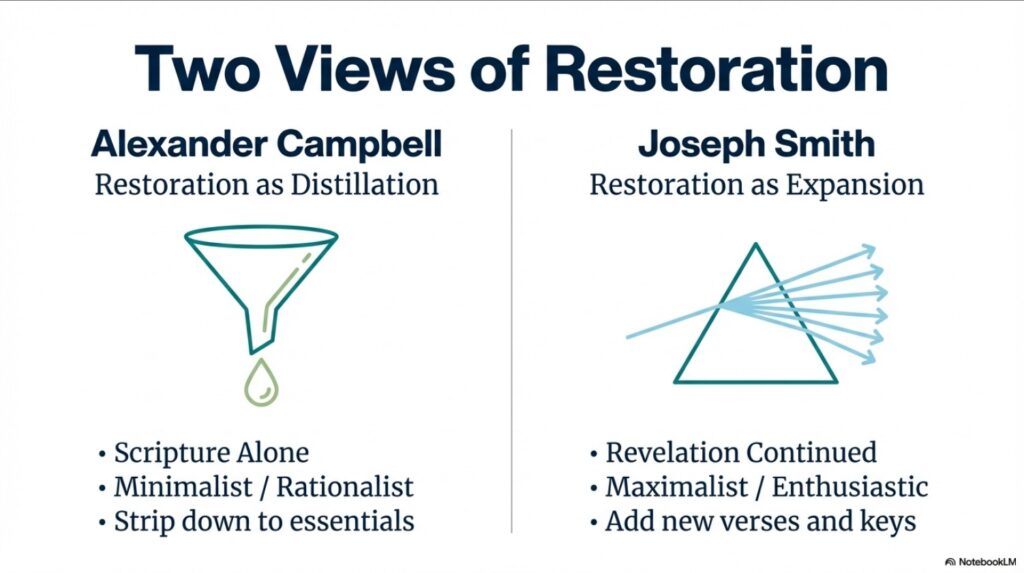

In her excellent book, Alexander Campbell and Joseph Smith, 19th Century Restorationists, RoseAnn Benson discussed this dynamic by contrasting Joseph Smith with another religious leader from his day, Alexander Campbell.

He also considered himself to be the one to restore the true church. But his vision was very, very, very different than Joseph Smith’s.

Campbell favored this minimalistic restoration. He wanted to focus on stripping Christianity down to its New Testament essentials. His restoration was like a distillation.

RoseAnn Benson writes:

Alexander’s restoration focused on a rational and reasoned interpretation of the scriptures through the lens of enlightenment philosophy, while Joseph Smith approached restoration through what the nineteenth century called enthusiasm.

Campbell believed his restoration would bring Christianity back to its primitive church practices. He says:

“Restoration of the ancient order of things is all that is necessary to the perfection and happiness of society.”

He’s on the right track, right?

But by this, he meant there was a very, very limited number of things necessary for the church to be able to function, and there was no need to ever add any more to it.

He emphasized the importance of scripture alone, baptism, weekly observance of the Lord’s supper—for him, those were the fundamentals. Little else was needed. His restoration was to take the church to its barest essentials without any superfluous ideas or practices.

Joseph Smith’s Expansive View of Restoration

And Joseph Smith could not have viewed the restoration any more differently.

In one sense, Campbell used the term restoration in its most obvious form—to bring back something that had been lost. However, Joseph’s view of restoration was expansive, imaginative, and revelatory.

Quote from RoseAnn:

Not only did he want to bring back the ancient priesthood, covenants, and temple worship, but Joseph wanted to introduce new ideas, new scriptures, and new verses to the song the original covenants had sung in the Old Testament.

Expanding the Abrahamic Covenant through Temple Ordinances

This is well illustrated by his expansion on the Abrahamic covenant.

During the dedication of the Kirtland Temple, Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery received priesthood keys from a prophet named Elias, who committed the Abrahamic promises to him—enabling the gathering of Israel and the sealing of families.

The original Abrahamic covenant promised that Abraham, one specific man, his seed would be spread throughout the earth and that all would be blessed through him.

Joseph took this covenant and specified exactly how that would happen—and it would be through the sealing ordinances.

What is only hinted at in the Abrahamic promise becomes very specific through Joseph Smith, and it leads to our entire system of temple worship today.

The Mosaic Covenant

Moving on, we’ll talk about Moses.

Established between God and the Israelites at Mount Sinai, the Mosaic covenant was a conditional agreement laid out in terms that Israel could remain God’s chosen people.

It included the Ten Commandments and a broad legal code for government, moral, civil, and ceremonial life. The covenant emphasized obedience—blessings would follow if Israel kept God’s laws, and curses would follow when it was disobedient.

It also introduced a priesthood, a sacrificial system, and a sacred space—the tabernacle—to facilitate worship and atonement.

The Mosaic covenant is a foundational moment in scriptural history by illustrating God’s desire for a holy people and the challenges of human fidelity.

Living the Mosaic Covenant

But this covenant is different from the others that we have discussed as well.

It is not just modified by subsequent prophets in the future as the others were. It is essentially surpassed by the New Covenant in Jesus Christ.

For the sake of brevity in this paper, we’ll only consider the Mosaic covenant on its own without analyzing its relationship to the New Covenant—but you should have in the back of your mind how radically this is transformed by the New Covenant.

The Mosaic covenant also differs from the previous ones that we have talked about in that the trajectory of understanding is not in how meaning is layered on top of what has been given, but in how meaning was developed by the people living it.

This covenant certainly does receive additional layers of meaning as new scriptures are written and new prophets teach these principles, but the real change intended here is in the life of the person called to live the covenant.

A Peculiar People

While all Christians resonate with this covenant, Latter-day Saints can see a special kind of mirroring happening in it—similar to how we see ourselves as a peculiar people.

In this sense of the word, “peculiar,” of course, doesn’t mean odd or eccentric. Rather, it means set apart—as a people with a divine mission in life on behalf of those who have come before.

The Mosaic Covenant as a Framework for Covenant Living

So how do we see this playing out in the Mosaic covenant?

The Mosaic covenant is a multifaceted agreement between God and the Israelites that is more than just a set of rules. It’s an entire comprehensive framework for learning to live as God’s covenant people.

It includes the Ten Commandments; what they call the Book of the Covenant, which is essentially Exodus 21–23, which contextualizes the Ten Commandments into civil and social law; ceremonial law, which teaches the people about ritual purity, priestly duties, holy days, consecrations, and festivals; the sacrificial system, which details instructions for sacrifices when the laws are broken; instructions for the priesthood and the tabernacle; blessings and curses that come with obedience and disobedience; and finally, a covenant ceremony where the people affirm their willingness to enter into this covenant.

Modern readers sometimes read these rules and regulations and get so lost and so bogged down in the details that they sort of miss the theme. You can’t see the forest through the trees.

To be fair, many of the commandments are written for a society that is very, very different than ours. To understand further, some historical context is needed.

Brief History of the Israelites

So, at the beginning of the book of Exodus, we find God’s people enslaved to the Egyptians. God promises to rescue them, and He does.

And once the people are in the desert, it becomes obvious that living as slaves in Egypt did not prepare them for living a covenant life of trusting God as He led them through the wilderness. They are not practiced in the attitudes or behaviors required to allow them to be led in this way.

So God intervenes by giving the Ten Commandments and the Mosaic law.

Separation Laws and Identity Formation

To illustrate this point, let’s look at Exodus 23:19: “Do not cook a young goat in its mother’s milk.” The law is actually given to the people three times—Exodus 23:19, Exodus 34:26, and Deuteronomy 14:21.

Modern reader, you would not be wrong to wonder why the people needed to be told three times that they should refrain from cooking a young goat in this manner. Why is this commandment here in the first place? Right? Like, we’re not wrong to be confused by that.

And there have been many interpretations of these verses over time, ranging from the practical to the completely esoteric.

Rabbinic tradition uses this verse to build the separation of meat and dairy in Jewish dietary laws, and maybe that’s as good an interpretation as any of the others, right?

Observant Jews today still maintain separate dishes, utensils, and even sinks and counter space for meat and dairy—have a meat sink and a dairy sink. Their kitchens are built in such a way that you could not cook cream of mushroom soup with the same utensils that you would use to make a turkey sandwich. They must be separate.

Why?

Learning to Be a Peculiar People

Well, as God reveals these laws for living to the people, the observant reader notices that God has commands about keeping some things separate from other things.

These include things such as no intermarrying with people who are not Jews, no mixing of two types of fabric unless they’re specifically instructed to do so.

Later in Leviticus, along these same lines, we find many things God wants to keep separate. And there are certain things you can’t touch, like dead bodies. And if you do, you’ll be considered unclean for a period of time. You must keep yourself separate from them.

Certain animals had to be kept separate from other animals. Some animals are for eating, and some animals are not. The people must separate themselves from impure practices and from certain foods.

What’s happening here is the Lord is trying to teach them in a way that they can understand.

What does “purity” mean?

The point of all these purity laws—and “purity” here means keeping one thing separate from another—all of these separation laws, is to help them understand that God’s people are to be distinct or peculiar.

They are not to mix—not because the other people or groups aren’t God’s children as well—but because God has chosen to work through one nation to bless all the other nations. They are not to mix this and that because they are to be distinct.

The whole point of keeping things separate is to give them a living example of keeping themselves separate from the false teachings and practices around them, of which there were many.

The Lord is not being unreasonable. He’s trying to shape the people into understanding that creating an idol, like they did with the golden calf, is not going to help them become His people.

Instead of just telling them this, He wanted them to have reminders of it all the way down to how they cook a young goat, or how they sew a sweater.

They belong to God, and He cannot shape them into the nation they need to be if they are following the same practices as everybody else. God is using these rules as identity formation.

Redemption as a Process

A careful reading of the text reveals a God who cares about the redemption of His people.

Frequently, as impatient beings, we would like redemption to be instant and complete, and to be some kind of magic thing that happened to us. We don’t necessarily want an opportunity to live in a context where redemption can be played out by us.

After the golden calf incident, the Lord could have fixed everything with Israel and just tried to continue leading them as before. But the people would not have changed. They still would not have been ready to live as His covenant people.

God doesn’t usually magically zap change into human beings. And He also doesn’t expect us to change on a dime.

One day, these Israelites—they really have no idea how to trust God—and the next day they’ve left Egypt and they’re expected to get it right every single time? Well, that’s just not how God handles them.

Instead, He provides a structure in which they can learn over time how to become His faithful followers.

The trajectory of change here is not to the covenant itself—at least not this time. It’s to the development of change that happens to a person who seeks to follow the covenant.

Modern Application

Like most Christian Latter-day Saints, we don’t follow the Mosaic covenant today.

However, we do have our own set of rules and practices that help us to be formed into the kind of people that God can work with.

Old Testament Covenants—God’s Unfolding Relationship with Humanity

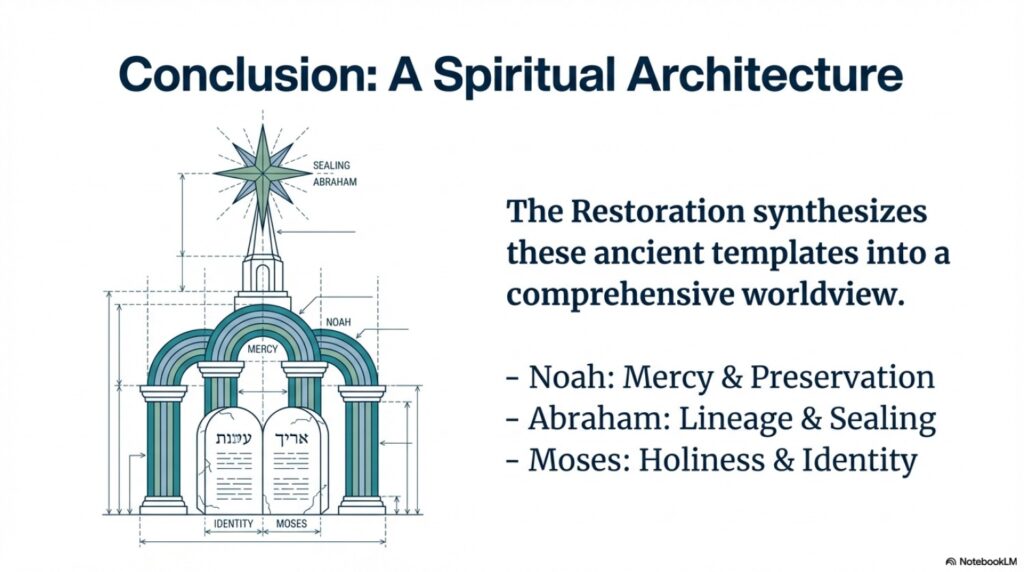

So, in conclusion, the covenants we get from Moses and Abraham, along with Noah, represent distinct stages in God’s unfolding relationship with humanity. And yet, their meaning stretches far beyond the historical moments in which they were established.

For Latter-day Saints, these covenants form a spiritual architecture that reveals sacred patterns over time. Rather than offering direct analogues to modern ordinances or temple covenants, these biblical agreements operate as theological templates—each illuminating principles such as obedience, lineage, divine protection, and communal identity.

Importantly, restoration scriptures and modern revelation reinterpret those covenants through the lens of continued progression, portraying them as expressions of God’s endearing desire to bind Himself to His people.

Covenants as a Living Narrative

The layered meaning of these ancient covenants encourages Latter-day Saints to see their own spiritual journey as part of a larger covenantal narrative. As we study these foundational agreements, we gain tools for interpreting modern covenants—not in isolation, but as echoes of eternal themes.

God’s promise to make a people holy, preserved, and chosen reverberates through the patriarchs and prophets. Eventually converging in restoration doctrine and still being revealed today.

In this way, the covenants become more than static contracts. They evolve as relations tailored to the unfolding dispensations, allowing modern Saints to find relevance and renewal in ancient words.

Search topics

Old Testament covenants; Noahic covenant; Abrahamic covenant; Mosaic covenant; covenant theology; biblical covenants; Genesis covenants; Exodus law; Ten Commandments; covenant renewal; covenant expansion; progressive revelation; Restoration theology; Joseph Smith restoration; continuing revelation; temple covenants; sealing ordinances; gathering of Israel; covenant path; peculiar people; CES Letter; Mormon Church abuse; Mormon LGBTQ; LDS finances; polygamy; Mormon racism; Mormon women; LDS temple ordinances; Book of Mormon; are Mormons Christian