The Old Testament and the Interpretive Bounds of Modern Revelation

When it comes to understanding the Old Testament, does modern revelation—both our canonized scripture and the interpretive magisterium of church leaders—do these function more as a straight jacket, binding us to difficult Old Testament interpretations like Young Earth creationism? Or does modern revelation function more like a parachute—something that helps us out of interpretive crises and difficult passages of the Old Testament? This is my topic today, and most of my argumentation about the Old Testament itself will be found in the published paper, because I’m already going to be talking for too long. Misinterpretation and Interpretation

Misinterpretation and Interpretation

Some years ago, President Hubie Brown quoted President Anthony W. Ivans: It is our misinterpretation of the word of the Lord that leads us into trouble. Well, if true, the question we should be asking ourselves is, how can we avoid misinterpreting scripture?

Well, we should begin by talking about what interpretation is. Interpretation is nothing more than attributing meaning to the text — what you think the text means, what you think the author was trying to say.

We should also understand that we are all interpreting all the time. It’s impossible not to interpret. We all bring different assumptions, knowledge, and background to the text when we’re interpreting — and those things shape the interpretation we give.

And oftentimes, when we find ourselves disagreeing with someone else’s interpretation, it’s because of those different things we are bringing to the text.

Two Key Interpretations

Now, there are two key interpretations in this topic that have to do with the nature of scripture and the nature of how we should read it. So first: assumptions about the nature of scripture. Is scripture authored from a single perspective — and that perspective would represent divine omniscience? If so, this gives us a concept of scripture as a univocal, quasi-inherent encyclopedia of static eternal truths of doctrine, history, and science. The one perspective represented in scripture would be God’s. And we can call this model the divine encyclopedia model of the nature of scripture. On the other hand, is scripture authored from a divinely inspired but human perspective — humans influenced by their culture, time, and setting? If this is our assumption when we read scripture, it gives us a concept of scripture which allows for multiple perspectives, as well as line-upon-line progressive revelation expanding and correcting partial truths and cultural assumptions. We might call this the inspired human author model of scripture.Methods of Reading Scripture

Now, that is scripture itself — but what about how we ought to read it? There are assumptions about our method of interpretation, our method of reading. And again, let me provide two of these. One says the meaning of scripture is self-evident and can be understood through face-value reading regardless of translation and without any significant attention to contexts. We can call this plain reading — you just read scripture and its meaning is plain. Now, I should also clarify that when I am talking about the meaning of scripture, I am primarily talking about the meaning as the authors intended anciently. I want to acknowledge that there is another meaning that’s important. President Oaks taught that scripture is not limited to what it meant when it was written, which is what concerns us today, but may also include what that scripture means to a reader today. The second is more of a devotional or spiritual aspect of reading scripture. And we need to be doing both.

But when I talk about scripture’s meaning, I’m primarily talking about the author’s original ancient intention — what Moses meant, what the Israelites understood.

So should we read it through plain reading? Or is the meaning of scripture accessible through careful attention to history, translation, and various kinds of context, such as cultural and literary context? We call this contextual reading.

Now, I should also clarify that when I am talking about the meaning of scripture, I am primarily talking about the meaning as the authors intended anciently. I want to acknowledge that there is another meaning that’s important. President Oaks taught that scripture is not limited to what it meant when it was written, which is what concerns us today, but may also include what that scripture means to a reader today. The second is more of a devotional or spiritual aspect of reading scripture. And we need to be doing both.

But when I talk about scripture’s meaning, I’m primarily talking about the author’s original ancient intention — what Moses meant, what the Israelites understood.

So should we read it through plain reading? Or is the meaning of scripture accessible through careful attention to history, translation, and various kinds of context, such as cultural and literary context? We call this contextual reading.

Our Intellectual Inheritance

Our Intellectual Inheritance

Now, because the church was restored in America in the 1800s, we have an American Protestant intellectual inheritance. These pushed us very strongly in the direction of the divine encyclopedia model of scripture and a plain reading method of interpretation.

Now, this has been pretty common in the church, but it’s competed with some other things — and that competition means that we have sometimes made fun of certain Protestants who say, The Bible says it, I believe it, that settles it.

But on the other hand, we have certain Latter-day Saints who may think that, Well, of course the Bible hasn’t been translated correctly, but modern revelation says it, I believe it, that settles it. That is still treating scripture like the divine encyclopedia model.

Now, the divine encyclopedia model and plain reading create many difficulties for us and bind us to difficult understandings of the Old Testament. This was our intellectual inheritance.

Modern Revelation as a Parachute

Modern Revelation as a Parachute

Today I will argue that the church’s position is that scripture is written from inspired human perspectives; that historical, cultural, and literary contexts are important; and that if we do not pay attention to those things, then we will not fully understand the meaning of scripture — and of course, ancient meaning, not Holy Ghost–inspired personal devotional discipleship application.

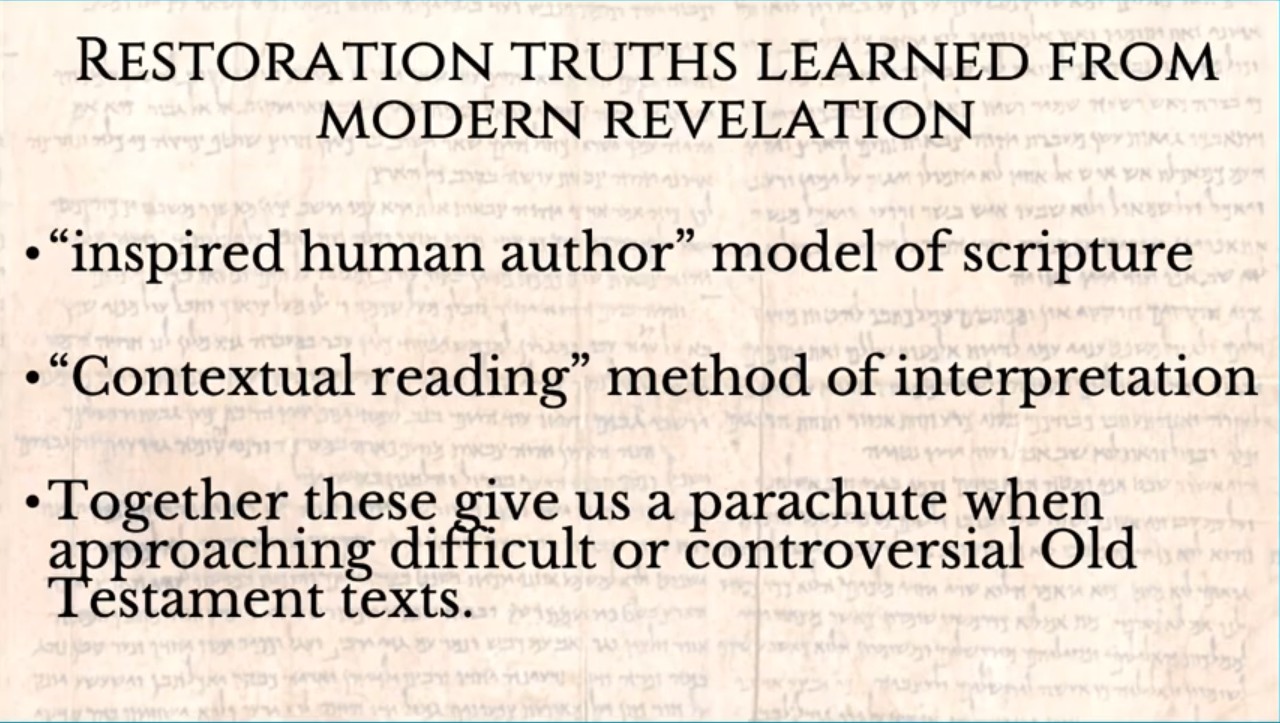

Now, if this was our intellectual inheritance, I would argue that as we study our own modern revelation closely, we are shedding that 19th-century Protestant inheritance for restoration truths about the nature of scripture and interpretation. Namely, we are embracing the inspired human author model of scripture and the contextual reading method of interpretation.

This is wonderfully liberating from the straight jacket, as we will see — and these come from studying modern revelation closely together. These give us a parachute when approaching difficult or controversial Old Testament texts instead of the straight jacket.

Principles from Modern Revelation

Principles from Modern Revelation

I’m going to be quoting a good bit today from a number of church sources — from four manuals and one new book from Deseret Book, which is different than a church manual, but it’s significant in the sense that Deseret Book, as a branch of the church, allowed it to be published.

I want to start, before quoting from these, by laying out several principles that we get from modern scripture and current church teaching that enable us to make sense of all of the Old Testament messiness.

There are seven of these, and I’m going to cover the first two together. They are the idea of prophetic co-participation in revelation — that is, the idea that human prophets are participants with God to some extent, that all revelation is going to be some human–divine mix — and second, that revelation is an ongoing and partial process as opposed to a singular event.

Now, close study of the Book of Commandments, according to BYU professor Grant Underwood, reveals this: Joseph’s revelations were not understood as infallible texts written in stone by the finger of God.</em> They came instead through a finite and fallible prophet who, along with his associates, was not short of his humanity in exercising his prophetic office.

Moreover, the revelation texts were not viewed as fixed and complete beyond revision, but as articulations that could and should be updated to reflect the ongoing flow of revelation to the church.

Now, close study of the Book of Commandments, according to BYU professor Grant Underwood, reveals this: Joseph’s revelations were not understood as infallible texts written in stone by the finger of God.</em> They came instead through a finite and fallible prophet who, along with his associates, was not short of his humanity in exercising his prophetic office.

Moreover, the revelation texts were not viewed as fixed and complete beyond revision, but as articulations that could and should be updated to reflect the ongoing flow of revelation to the church.

Prophetic Participation in Revelation

Now, Professor Underwood first gave this as a devotional at BYU–Hawaii, and then it came through a BYU publication, and then there is also an academic publication — and that’s the one I’m quoting from specifically here. He says elsewhere in one of these: Some Latter-day Saints may assume that the prophet was not involved in any way whatsoever with the wording of the revelation texts, that he simply repeated word for word to describe what he heard God say to him. But our investigation again into the Book of Commandments has suggested otherwise.

We need to see Joseph — and I would say other prophets, modern and ancient — as more than a mere human fax machine through whom God communicated finished revelation texts composed in heaven. Joseph had a role to play in the revelatory process.

He says elsewhere in one of these: Some Latter-day Saints may assume that the prophet was not involved in any way whatsoever with the wording of the revelation texts, that he simply repeated word for word to describe what he heard God say to him. But our investigation again into the Book of Commandments has suggested otherwise.

We need to see Joseph — and I would say other prophets, modern and ancient — as more than a mere human fax machine through whom God communicated finished revelation texts composed in heaven. Joseph had a role to play in the revelatory process.

Revelation as Ongoing Process

Revelation as Ongoing Process

Close study of the Doctrine and Covenants has revealed similar things. Steven Harper at BYU: Joseph knew better than anyone else that the words he dictated were both human and divine. There’s that composite. The voice of God clothed in the words of his own limited early American English vocabulary.

He regarded himself as a revelator whose understanding accumulated over time. Joseph recognized, as a result of the revelatory process — there’s that process word again — that the texts of his revelations were not set in stone. Rather, he felt responsible to revise and redact them to reflect his latest understanding.

And this is what happens when you look into the history of the Doctrine and Covenants. Joseph adapts and updates revelations as he gets more information. And there are examples of this as well in Moses and Abraham and Genesis and the temple, which I’ve spoken about earlier at FAIR, and also between the JST and the Book of Mormon.

Speaking of the JST, close study of the JST — or Joseph Smith Translation — has revealed that it was not a simple mechanical recording of divine dictum, but rather a study and thought process accompanied and prompted by revelation from the Lord. That it was a revelatory process is evident from statements by the prophet and others who were personally acquainted with the work.

Speaking of the JST, close study of the JST — or Joseph Smith Translation — has revealed that it was not a simple mechanical recording of divine dictum, but rather a study and thought process accompanied and prompted by revelation from the Lord. That it was a revelatory process is evident from statements by the prophet and others who were personally acquainted with the work.

Revelation in Modern Church Teaching

Revelation in Modern Church Teaching

Now, in a recent church manual, here we actually find an entire subsection talking about recognizing that revelation is a process.

It’s easy to imagine that when God wants to communicate something, he simply reaches out to church leaders to let them know. But the history of the Restoration demonstrates that revelation is a process of seeking to know God’s will and is most often received after pondering and pleading. The church’s policies, programs, organizations, and teachings have been revealed line upon line over months, years, and decades, and the process continues. As President Uchtdorf has said, the Restoration is ongoing.

Well, if revelation is a process, and prophets play a role in forming that revelation — in shaping it and giving voice to it — if this is true of modern prophets like Joseph Smith, how much more so of ancient ones?

Scripture from Inspired Human Perspectives

Scripture from Inspired Human Perspectives

Well, this brings me to principle number three, which is that scripture speaks from inspired and accommodated human perspectives.

Here is Come, Follow Me for 2026: Naturally, these Old Testament stories are told from a certain point of view. It’s inevitable that a historical account will reflect the perspective of the person or groups of people writing it. This perspective includes the writer’s national or ethnic ties and their cultural norms and beliefs. Knowing this can help us understand that the writers and compilers of the historical books focused on certain details while leaving out others. They made assumptions that others would not have made, and they came to conclusions based on these details and assumptions.

We can even see different perspectives across the books of the Bible — and sometimes within the same book. The more we’re aware of these perspectives, the better we can understand.

Again, from the same manual: You might think of the book of Proverbs as a collection of wise counsel from loving parents. But Proverbs is followed by the book of Ecclesiastes, which seems to say it’s not that simple. The two books look at life from different perspectives.

Even within inspired scripture, we find different perspectives represented because those perspectives are coming from humans with their own perspective and assumptions and culture and background.

Here is Come, Follow Me for 2026: Naturally, these Old Testament stories are told from a certain point of view. It’s inevitable that a historical account will reflect the perspective of the person or groups of people writing it. This perspective includes the writer’s national or ethnic ties and their cultural norms and beliefs. Knowing this can help us understand that the writers and compilers of the historical books focused on certain details while leaving out others. They made assumptions that others would not have made, and they came to conclusions based on these details and assumptions.

We can even see different perspectives across the books of the Bible — and sometimes within the same book. The more we’re aware of these perspectives, the better we can understand.

Again, from the same manual: You might think of the book of Proverbs as a collection of wise counsel from loving parents. But Proverbs is followed by the book of Ecclesiastes, which seems to say it’s not that simple. The two books look at life from different perspectives.

Even within inspired scripture, we find different perspectives represented because those perspectives are coming from humans with their own perspective and assumptions and culture and background.

The Principle of Accommodation

The Principle of Accommodation

Now, God himself may introduce human aspects into scripture through what we call accommodation. This is defined briefly: accommodation is God’s adoption of the human audience’s finite and fallen perspective. Its underlying conceptual assumption is that, in many cases, God does not correct our mistaken human viewpoints but merely assumes them in order to communicate with us.

Now, this is particularly clear to me in Genesis 1, where God assumes the ancient Near Eastern cosmology of a flat earth with a solid dome surrounded by the cosmic chaotic waters in order to teach the Israelites important things about the nature of creation, the nature of God, and the nature of humans in relation to that creation and to God. It was not about physical creation or the solar system or anything like that. God assumed that understanding to communicate these other things. He accommodated.

Accommodation in Church Sources

Accommodation in Church Sources

Well, here it is in the Liahona a couple years ago: God speaks in the cultural context of the life and time of a person or people. He communicates according to their understanding. The Lord kindly condescends to communicate his will in their language and culture so he can instruct and succor them.

Here is accommodation in recognizing that revelation is a process: Remember that God speaks to us according to our understanding. All human beings are shaped by culture — the beliefs, customs, languages, and values we share. Cultures vary greatly from place to place and over time. God’s willingness to deliver revelation that speaks to us within our cultures and according to our understanding is a beautiful truth of the Restoration.

Remembering this can help us approach the scriptures and the words of past prophets with humility. God spoke to the ancient Israelites according to their ancient Near Eastern understanding. He spoke to Joseph Smith using symbols and language from his 1800s American culture. And God communicates with us today according to our own limited capacity in ways that we can understand.

Avoiding Distortion Through Harmonization

Avoiding Distortion Through Harmonization

Now, I have actually spoken about accommodation at a prior FAIR conference, and you can go back and watch that — and there are lots of references. And this brings me to assumption number four that we find in current church teaching and from modern revelation, which is: harmonization may in fact distort understanding.

This is from a manual called Scripture Helps: Old Testament. It was released briefly as a mistake but should be released soon. I have a PDF copy.

Note what it says: Because we live in a very different world from the people who wrote the Old Testament, we might mistakenly apply our own modern views and cultural standards to what we are reading. This can lead to misunderstandings. Make an effort to see what you are reading from the perspective of the inspired authors in their original context.

Working to Understand the Past

Working to Understand the Past

Here’s another example from a different manual. This is also from the Answering My Gospel Questions manual under the subheading Work to Understand the Past:

When we study the past, we sometimes find that practices, teachings, and ideas we thought were unchanging have actually changed quite a bit. Core principles of the gospel are eternal. But the ways they are understood and expressed over time reflect the line-upon-line nature of revelation and the constant change of human culture. The principle of continuing revelation helps us navigate these changes.

And here I think we can see an example when we read the Book of Mormon closely. We have sometimes taken our understanding from the Book of Mormon and retrojected it into the Old Testament, trying to harmonize.

But note that Lehi has to assume the existence of a devil. It wasn’t common Israelite teaching or understanding. He derives it from something he’s read. Similarly, Lehi seems to have new revelation about the nature of a Messiah for the entire world. It does not seem that this was common Israelite understanding, but that it was special revelation.

And we shouldn’t take these things that are our understandings today and just retroject them onto the Old Testament, because that may distort our understanding.

Scripture Is Not Inerrant

Scripture Is Not Inerrant

Principle number five: scripture is not inerrant.

Now, we don’t use the term inerrant or inerrancy much in the church, but in fact many of us hold to inerrant ideas in practice. But I want to point out again how the manuals are speaking about this.

Come, Follow Me: In addition to being limited to a particular perspective — that is, in their time, place, culture, etc., except as God steps in with inspiration — scriptural histories are subject to human error.

Well, we get this in part from the Book of Mormon. The inspired word of God, even though like any work of God transmitted through mortals, is subject to human imperfections. The words of Moroni referring to the sacred Book of Mormon record that he helped compile are helpful here: “If there are faults, they are the mistakes of men. Wherefore condemn not the things of God.”

In other words, a book of scripture does not need to be free from human error to be the word of God. Latter-day Saints do not require inerrancy for inspiration, and neither does inspiration entail inerrancy.

Learning from Human Imperfection

Learning from Human Imperfection

Here again from Answering My Gospel Questions — Work to Understand the Past:

Remember that humans make mistakes. When we tell stories from church history, we tend to focus on heroic actions and happy endings. It is good to remember people when they were at their best. But we sometimes forget that Latter-day Saints of the past, including early Church leaders, were human beings. Human beings have weaknesses. They make mistakes. They sin. Remember that God uses imperfect people to accomplish His work. We can learn from both their contributions and their mistakes.

Oftentimes, when we read the Old Testament, we get confused at what we see role models doing because we assume scripture is telling this story to focus on heroic actions and happy endings. It may in fact be that the Old Testament recorded particular stories so that we can learn from mistakes as well. But they rarely made it explicit.

The Old Testament almost never borrows Mormon’s statement when he wants to step in and say, “And thus we see.” In case you’re missing the lesson. The Old Testament tends to make those lessons via other means than explicitly saying, “And thus we see.”

Scripture Was Addressed to Ancient Peoples

Scripture Was Addressed to Ancient Peoples

Principle six: ancient scripture was addressed to ancient peoples, and so ancient context is crucial to understanding.

Now, there’s an evangelical scholar who holds to inerrancy named John Walton who has given this principle a very pithy name that’s worth remembering: Scripture is for us but not to us.

The theological message of the Bible was communicated to people who lived in the ancient Near Eastern world. If we desire to understand the theological message of the text, we will benefit by positioning it within the worldview of the ancient world rather than simply applying our own cultural perspectives.

And I would point out that in a recent Church News interview with an institute professional, he mentioned John Walton as an Old Testament scholar whose work has been very useful. I have mentioned John Walton a good bit in my writings. I’ve also found his work very useful. But the fact that his name was allowed to be mentioned in that interview I think was significant, because in my experience, the church is very reluctant to name-drop particular non–LDS scholars lest people misunderstand that the church is somehow kind of standing behind everything they say.

But Walton’s point here is that if scripture was for ancient people and we want to understand it, we need to try to learn about those ancient aspects — their culture, their time, their history.

The theological message of the Bible was communicated to people who lived in the ancient Near Eastern world. If we desire to understand the theological message of the text, we will benefit by positioning it within the worldview of the ancient world rather than simply applying our own cultural perspectives.

And I would point out that in a recent Church News interview with an institute professional, he mentioned John Walton as an Old Testament scholar whose work has been very useful. I have mentioned John Walton a good bit in my writings. I’ve also found his work very useful. But the fact that his name was allowed to be mentioned in that interview I think was significant, because in my experience, the church is very reluctant to name-drop particular non–LDS scholars lest people misunderstand that the church is somehow kind of standing behind everything they say.

But Walton’s point here is that if scripture was for ancient people and we want to understand it, we need to try to learn about those ancient aspects — their culture, their time, their history.

Ancient Context in Church Teaching

Ancient Context in Church Teaching

Note the teaching of John Taylor as paraphrased in The Instructor: The Bible was written for the people of its day. Isaiah, Ezekiel, and so on had revelations for themselves, not us.

Note LDS Old Testament scholar Sidney Sperry, who wrote in the Ensign: We oftentimes read our Bible as though its peoples were American and interpret their sayings in terms of our own background and psychology. But the Bible is actually a Near Eastern book. It was written centuries ago by Near Eastern people and primarily for Near Eastern people. It may be “for us” in the sense that God, looking into the future, intended us to profit from scripture. But it was not written “to us.”

He’s using “for us/to us” slightly differently.

Now, just as general conference talks of the 1910s largely spoke to the issues of the 1910s and the American cultural idiom of that time, so too did Jeremiah’s preaching in the 7th century BC address issues of the 7th century and the idiom of their time.

Come, Follow Me on Ancient Audiences

Come, Follow Me on Ancient Audiences

Here — this is in Come, Follow Me:

People today aren’t the primary audience of the Old Testament prophets. Those prophets had immediate concerns that they were addressing in their time and place, just as our latter-day prophets address our immediate concerns today. When you read ancient prophecies, it can help to learn about the context in which they were written.

Well, indeed — if scripture is for us but not to us, we need that ancient context to understand it the way they did.

And here again, Come, Follow Me: You can find meaningful insights about a scripture if you consider its context — the circumstances or setting of the scripture.

The Need for Context: Revelations in Context

The Need for Context: Revelations in Context

Several years ago, the church provided this book for us called Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants. The introduction notes that, in many cases, the Doctrine and Covenants contains only half of the dialogue and does not contain the stories behind the revelations. While the section headings provide some context for the revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants, they don’t tell the complete story.

Well, for that complete story, we need context that scripture itself — even the Doctrine and Covenants — does not provide. This is why the church has given us Revelations in Context.

If that is true — that we need this kind of context for a book of scripture only 200 years old, revealed in America, in English, not in translation — how much more is context necessary to understand ancient revelations that came over a thousand years, in many different places, in at least two different languages, and with several different cultures involved?

The Importance of Context in Interpretation

The Importance of Context in Interpretation

And then in translation — well, this is why studying in context is emphasized. Here again, Answering My Gospel Questions teacher manual: Place things in context.

People in the past had different assumptions about the world than we do. If we want to better understand the words and actions of those in the past, we also need to understand the culture and context in which they occurred. Understanding historical context helps us keep from imposing our present views on people of the past in a way that prevents understanding.

Here again from the old Scripture Study: Power of the Word manual — Study in Context:

- We must seek to understand the time and place where scripture originated.

- Understanding culture will help in comprehending scriptures.

- Study the historical context and setting of scriptural passages. Study the cultures that influenced the peoples of the scriptures. Study the geography, climates, and seasons of scriptural lands.

- we have Mesopotamian cultures like Assyria and Babylon and even the Sumerians.

- We have Egyptian culture.

- We have Canaanite culture.

- We have numerous other peoples who are named and who they’re interacting with and having influence on.

Literary Context and the Importance of Genre

Literary Context and the Importance of Genre

Now, one particularly important kind of context is literary context. And I’m going to say genre. Genre is just a word meaning kind. Understanding what kind of thing I’m reading is really important.

This is because different genres have different purposes and different conventions. If we misunderstand what kind of thing we’re reading, we’re likely to ask the wrong questions and draw the wrong conclusions.

And this is something that’s been widely recognized. C. S. Lewis wrote that the first qualification for judging any piece of workmanship, from a corkscrew to a cathedral, is to know what it is — what it was intended to do, and how it is meant to be used. If you’re judging a cathedral based on whether it’s drawing tourists as opposed to hosting religious events, you’re not understanding it correctly. You’re not judging it based on proper conventions.

Similarly, an Old Testament professor named Walter Moberly writes: You cannot put good questions and expect fruitful answers from a text apart from a grasp of the kind of material it is in the first place. Misjudge the genre and you may skew many of the things you try to do with the text.

And here again, I think of Genesis and so many of the ways we try to extract scientific facts from Genesis or cram modern scientific facts into it. Genesis was not about revealing scientific facts about creation. It was about theology. It was about the nature of God and creation and humans.

And this is something that’s been widely recognized. C. S. Lewis wrote that the first qualification for judging any piece of workmanship, from a corkscrew to a cathedral, is to know what it is — what it was intended to do, and how it is meant to be used. If you’re judging a cathedral based on whether it’s drawing tourists as opposed to hosting religious events, you’re not understanding it correctly. You’re not judging it based on proper conventions.

Similarly, an Old Testament professor named Walter Moberly writes: You cannot put good questions and expect fruitful answers from a text apart from a grasp of the kind of material it is in the first place. Misjudge the genre and you may skew many of the things you try to do with the text.

And here again, I think of Genesis and so many of the ways we try to extract scientific facts from Genesis or cram modern scientific facts into it. Genesis was not about revealing scientific facts about creation. It was about theology. It was about the nature of God and creation and humans.

Genre in Church Teaching

Genre in Church Teaching

Now, Come, Follow Me says things about genre: Knowing what kind of book or section you’re studying can help you understand how to study it.

This has long been recognized, although many Latter-day Saints were unaware. Here is Elder John Widtsoe:

As in all good books, every genre is used in the Bible that will drive the lesson home. It contains history, poetry, and allegory and other genres. These are not always distinguishable now that the centuries have passed away since the original writing.

That is, when we pick up ancient scripture, we have this tendency to try to read it through our own ideas of genres, and we’re not culturally capable of picking up on the markers that might have indicated a different genre to them.

Recognizing Biblical Poetry

Recognizing Biblical Poetry

We’ll talk about this with poetry a little bit, but note how Come, Follow Me acknowledges genre:

The books of Job, Psalms, and Proverbs are almost entirely poetry, as are parts of prophetic books like Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Amos. Because reading poetry is different from reading a story, understanding it requires a different approach.

Now, many Latter-day Saints, when we open up Isaiah or Jeremiah or Amos, are not aware that we’re reading poetry. And so they read it as if it’s prose. And this means we tend to try to get different things out of it that it’s not necessarily offering.

Well, how should we read poetry?

Here is an Ensign article on it from June 1990. And Come, Follow Me goes into this a little bit, although not as much depth as this Ensign article from June 1990.

Wisdom Literature

Another genre that is recognized in Come, Follow Me is what’s called wisdom literature. One category of Old Testament poetry is what scholars call wisdom literature. Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes fall into this category. Now, we tend to be reading scripture looking for “How should I be living my life?” And a lot of scripture wasn’t written for that purpose. Leviticus wasn’t written for that purpose. Genesis wasn’t written for that purpose. But wisdom literature was explicitly about: How do I live the right kind of life? How do I live wisely? Recognizing that genre — and that it’s kind of limited to these and not the others — can be very helpful. History as Genre and the Limits of Historicity

History as Genre and the Limits of Historicity

Now, another kind of literary context under the heading of genre is history. Also, thanks to our Protestant intellectual inheritance, we tend to assume that inspiration entails history.

This is not the case.

This is Father Raymond Brown, a Catholic New Testament scholar. He notes:

“Often it is thought that inspiration makes everything history. It does not. There can be inspired poetry, drama, legend, fiction, etc.”

And this is not a function of disbelief. This is a function of him having studied ancient texts enough to start to learn how to recognize ancient genre markers and therefore say, “Oh, this is poetry. Oh, this is fiction.”

And of course, Jesus’ favorite method of teaching was fiction. We call that genre parables. The convention of parable is not that it’s trying to teach historical facts; it’s trying to use a short realistic story to make a moral or ethical point of some kind. Their truth does not depend on their historicity. They are fictional.

How Manuals Address Genre and Historicity

How Manuals Address Genre and Historicity

Now, here again — how do our current manuals address this kind of thing?

The Old Testament writers did not intend to provide a comprehensive historical account in their writings — from the Scripture Helps manual.

And here from Come, Follow Me:

Don’t expect the Old Testament to present a thorough and precise history of humankind. That’s not what the original authors and compilers were trying to create. Their larger concern was to teach something about God. Some Old Testament writers did not aim to be historical at all. Instead, they taught through works of art like poetry and literature.

And I should point out here, as we’re getting to another level, you can write boring prose that is completely fictional, and you can also write poetry about historical events. So we have to be careful to not make easy equations between what something appears to be and what it actually is — and what it’s trying to do.

Intellectual Humility and Careful Reading

Intellectual Humility and Careful Reading

Now, this brings me to my seventh and last principle, namely intellectual humility and careful reading.

This is something I’ve been guilty of myself at times. In spite of my training, I am still sometimes guilty of it. It is something that we have to check ourselves on constantly, regardless of whether we are lay person, prophet, or scholar.

When we are not careful, we end up overclaiming. We overclaim when we insert knowledge beyond what the Lord has revealed through both ancient and modern prophets. We are being dogmatic when we express our opinions as if they were indisputable facts and are intolerant of ambiguity when there are not clear answers.

Now, overclaiming tends to happen more if we are approaching scripture with the divine encyclopedia model and the plain reading model.

Warnings from Church Leaders About Overclaiming

Warnings from Church Leaders About Overclaiming

And this kind of thing has been noted in the past by general authorities. For example, the First Presidency in 1958 said that sometimes the brethren in the earlier days advanced ideas for which there is little or no direct support in the scriptures. They are largely speculative, concerning which the Lord has not yet revealed the truth.

In 1954, J. Reuben Clark in the First Presidency, regarding claims by individual church leaders — President Clark cautioned us to be wary of adventurous expeditions of the brethren into highly speculative principles and doctrines. And this was published as an important pamphlet. It was actually a corrective to some Young Earth speculation that was being popularized heavily through the Church Education System and BYU at the time.

Ambiguity and the Desire for Definitive Answers

Ambiguity and the Desire for Definitive Answers

Now, sometimes these adventurous expeditions, these speculations — especially if it seems to be coming from someone we hold to be a prophet, seer, and revelator, whether in 1850 or 1950 — they can seem very definite. They can seem very unambiguous.

Per President’s directive — and it’s pithy and easy to remember — We follow the brethren, not the brother.

When it comes to these quotes that can seem very unambiguous and definite, there’s a statement by Elder Paul Johnson, former Church Commissioner of Education and now the Sunday School President:

Many of us have a difficult time dealing with ambiguity or saying “I don’t know,” especially in issues concerning the church. In fact, we may be drawn to use quotes in our teaching that are definitive because they seem to dispel the ambiguity. But some quotes are definitive on issues where there is no official answer. People who are more tentative on a subject that hasn’t been revealed or resolved don’t get quoted as much, but may be more in line with where our current knowledge is. We follow living prophets, not dead ones.

Avoiding Overreading Through Careful Observation

Avoiding Overreading Through Careful Observation

President Oaks has told a story about reading carefully and avoiding overclaiming:

I remember the reported observation of an old lawyer as they traveled through a pastoral setting with cows grazing on green meadows. An acquaintance said, “Look at those spotted cows.” The cautious lawyer observed carefully and conceded, “Yes, those cows are spotted, at least on this side.”

He was careful not to overclaim beyond what could be observed, because it wasn’t certain.

Example: The Book of Job

Example: The Book of Job

Now, having gone through these seven principles, I want to look at one brief example. I intended to look at a lot more, but I didn’t think I would have time. The published paper will have a good number more.

So for this example, I want to look at the book of Job.

Now, as many Latter-day Saints know, Doctrine and Covenants alludes to Job where God says directly to Joseph Smith, Thou art not yet as Job.

Now, from this — as well as our inherited Protestant instinct to assume that inspiration means history — many Latter-day Saints have assumed that Job is a history.

And this creates discomfort, because the book of Job opens with the accuser — or Satan as the King James has it — goading God into torturing Job. Job becomes painfully ill. All his children are killed. All of his livelihood is killed. And he goes from a prosperous, pleasant, fruitful life to covered in painful boils with his wife telling him to curse God and die.

I am not comfortable with a God who is insecure enough to be goaded by Satan into doing that to a mortal.

Job as Parable

Job as Parable

Now, back in 1921, the First Presidency allowed:

that the book of Job was one of the kind prevailing in olden times, setting forth certain principles in the form of a parable, as it was with the parables of Jesus Christ in the flesh.They allowed for that possibility. They didn’t like it, but they allowed for it. Well, what does Come, Follow Me say? The opening chapters of Job emphasize in a poetic way Satan’s role as our adversary or accuser. They don’t describe an actual interaction between God and Satan. There is the parachute.

Modern Scholarship and Fictional Illustration

Modern Scholarship and Fictional Illustration

Now, this book is being published by Deseret Book in October of this year. This is BYU’s Joshua Sears, A Modern Guide to the Old Testament.

He says:

We should be careful not to confuse an allusion with a historical evaluation. The Lord and his prophets can quote or allude to fictional characters and narratives without making a judgment about the reality of those characters and narratives outside their literary world. The Cheshire Cat has been quoted several times in general conference, but this does not make the cat historical.

And I would point out as well that Jean Valjean from Les Mis has been quoted multiple times, as has Bart Simpson, as have a number of other clearly fictional things.

Joshua Sears continues in a similar manner:

When the Doctrine and Covenants compares Joseph Smith to Job, we should not assume that the allusions in and of themselves confirm the historicity of those stories. That would be overreading. That would be overclaiming.

Conclusions

Conclusions

First

What we learn from modern revelation and church teaching leads us away from our inherited 19th-century Protestant models of scripture as divine encyclopedia and plain reading. What we learn from these are the seven principles of:- prophetic co-participation in revelation,

- revelation as an ongoing and partial process,

- scripture speaking from inspired and accommodated human perspectives, not divine omniscience,

- harmonization may distort understanding,

- scripture is not inerrant,

- ancient scripture was addressed to ancient peoples. Therefore, ancient context is crucial if we want to understand the way ancient people did,

- and there is a role for intellectual humility and close careful reading that we need to emphasize more.

Conclusion number two

Conclusion number two