Summary

Historian Mark Ashurst-McGee explores the Joseph Smith Translation (JST) of the Bible in light of recent research suggesting that Smith drew upon Adam Clarke’s Bible commentary. In his FAIR Conference presentation, Ashurst-McGee addresses the complex balance between inspiration and scholarly influence, arguing that claims of plagiarism are speculative and uncharitable. He contextualizes the JST in terms of early Church publishing practices, translation theory, and 19th-century intellectual culture.

This talk was given at the 2020 FAIR Annual Conference on August 6, 2020.

Transcript

Introducing Mark Ashurst-McGee

Scott Gordon: Mark Ashurst-McGee is the senior historian in the Church History Department and the senior research and review editor for the Joseph Smith Papers. He also serves as a specialist in document analysis and documentary editing methodology. He holds a PhD in history. With that short introduction, we’re going to turn the time over to Mark.

Mark: Thank you.

So today, I’m going to talk about Joseph Smith’s new translation of the Bible, commonly called the JST, his apparent use of Adam Clarke’s Bible commentary, and the question of plagiarism, which has been raised recently. There’s been a lot of talk about this recently based on a study which has just come out showing these parallels between Joseph Smith’s new translation of the Bible, and Adam Clarke’s Bible commentary.

Mark Ashurst-McGee

Joseph Smith and the Question of Plagiarism

Overview

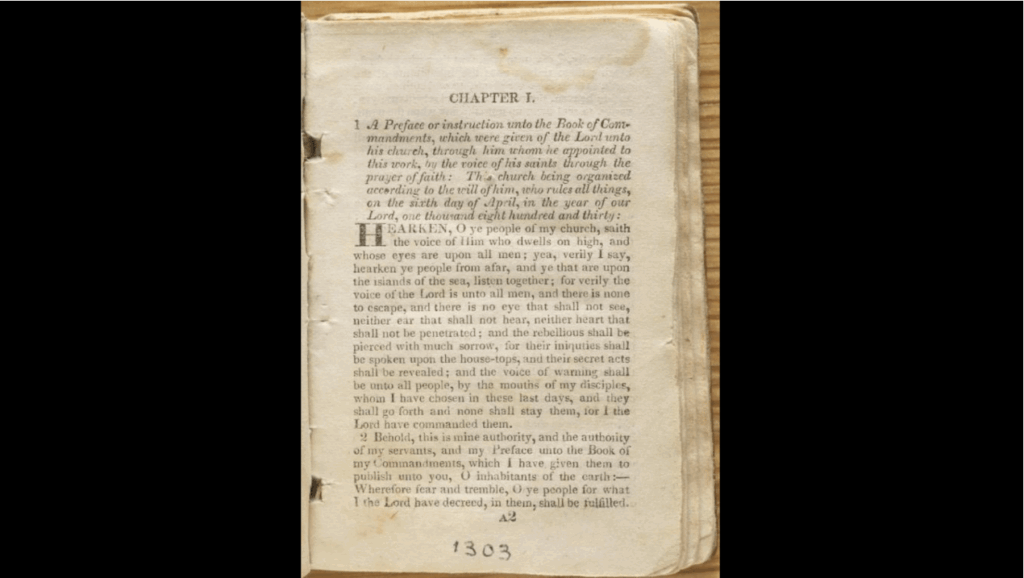

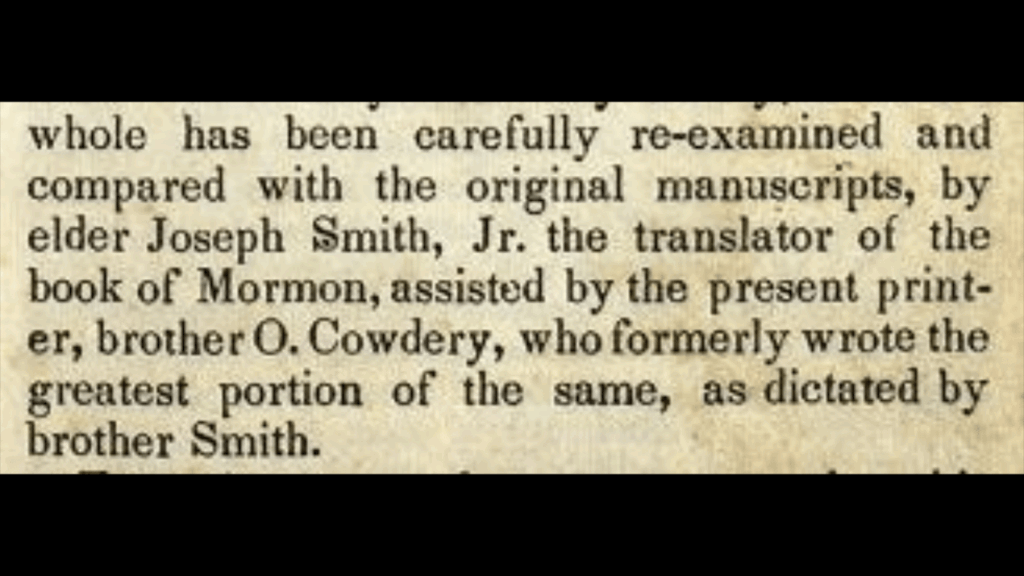

I’m going to try to give a quick overview of everything I’m going to talk about so that things will kind of make sense as we go along. So, for background, between 1830 and 1833, Joseph Smith worked on the Joseph Smith Translation of the King James Version of the Holy Bible. Extracts from the Joseph Smith Translation appear in the Pearl of Great Price as the books of Moses and Joseph Smith and Matthew. Church historians have long recognized that in addition to these and other expansions to the text of the Bible, there are hundreds of slight alterations that require no revelation or inspiration and are more plausibly explained as a simple modernizing of the text from the 17th century King James English to the 19th century Latter-day Saints’.

So, the Joseph Smith Translation is apparently a combination of supernatural translation given by God, and a natural modernization by Joseph Smith himself, and we’ll look at examples of that. Recent research seems to show that Joseph drew upon Methodist theologian Adam Clarke’s Bible commentary for several significant revisions in the JST, perhaps accounting for about five percent of the changes. Some detractors say that Joseph Smith is therefore guilty of plagiarism.

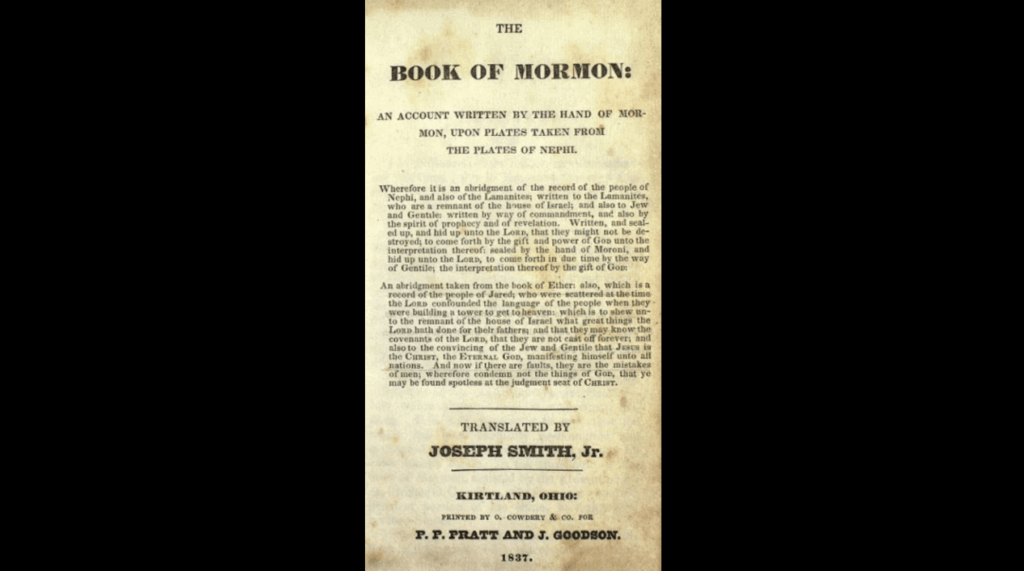

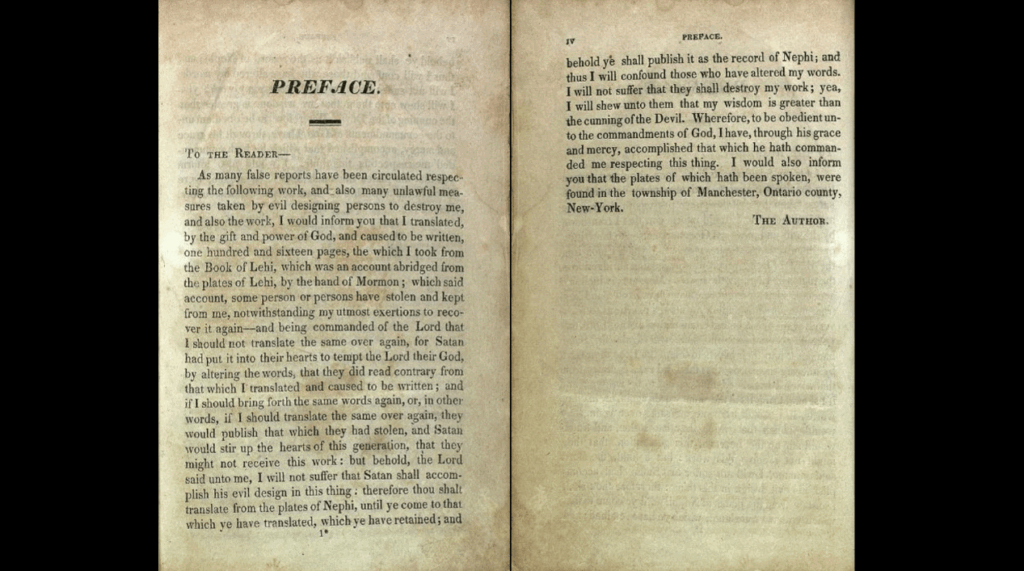

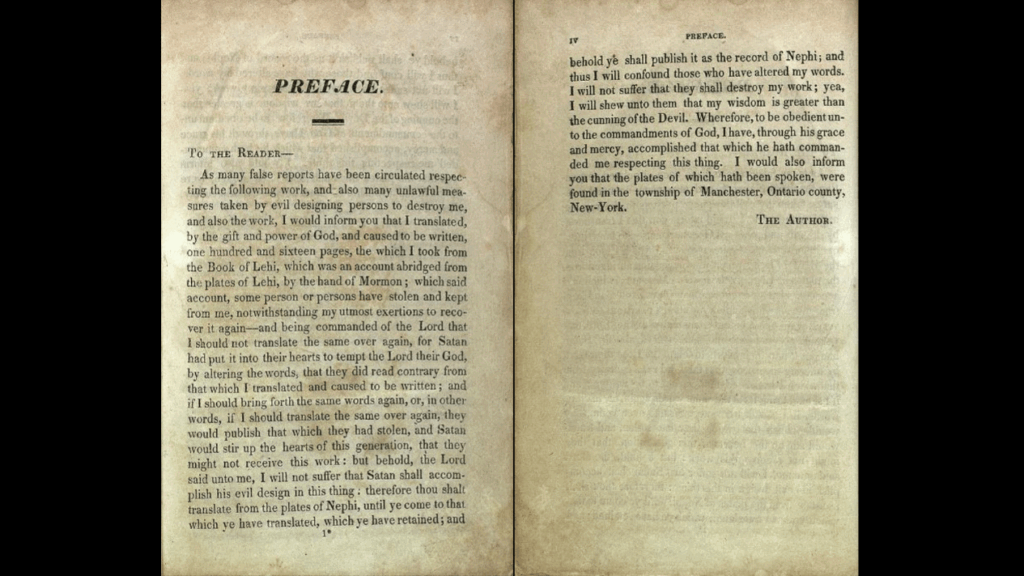

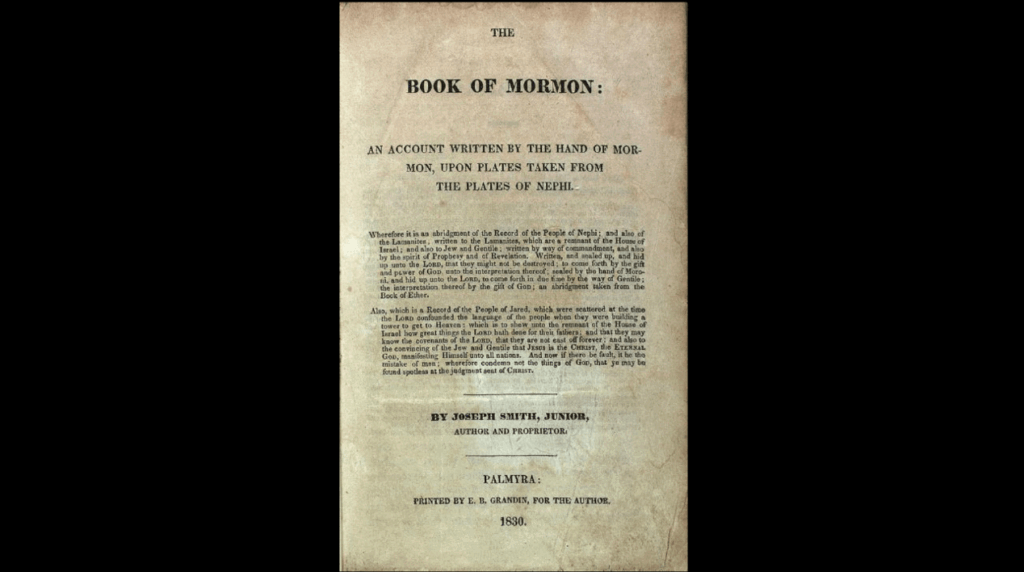

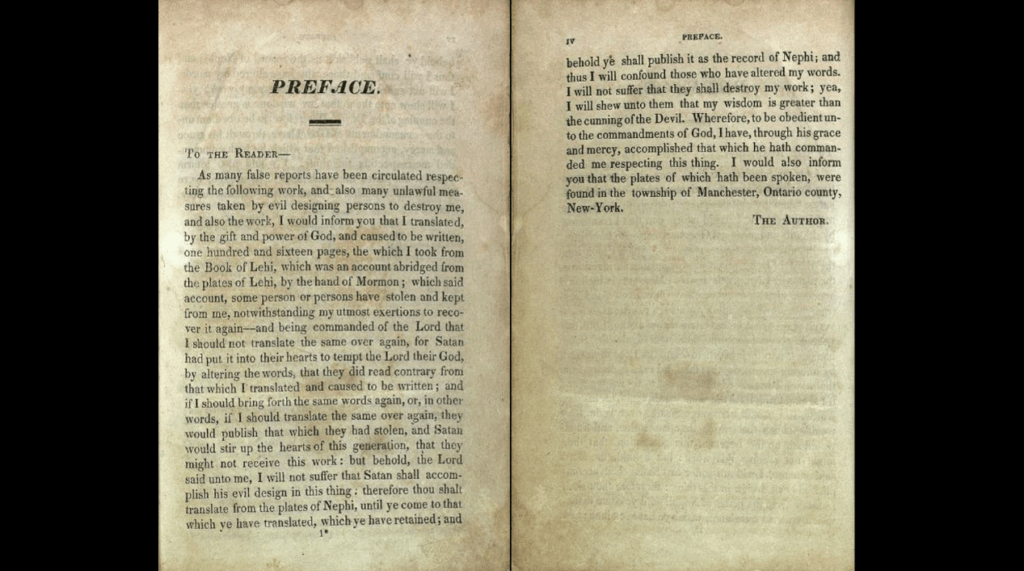

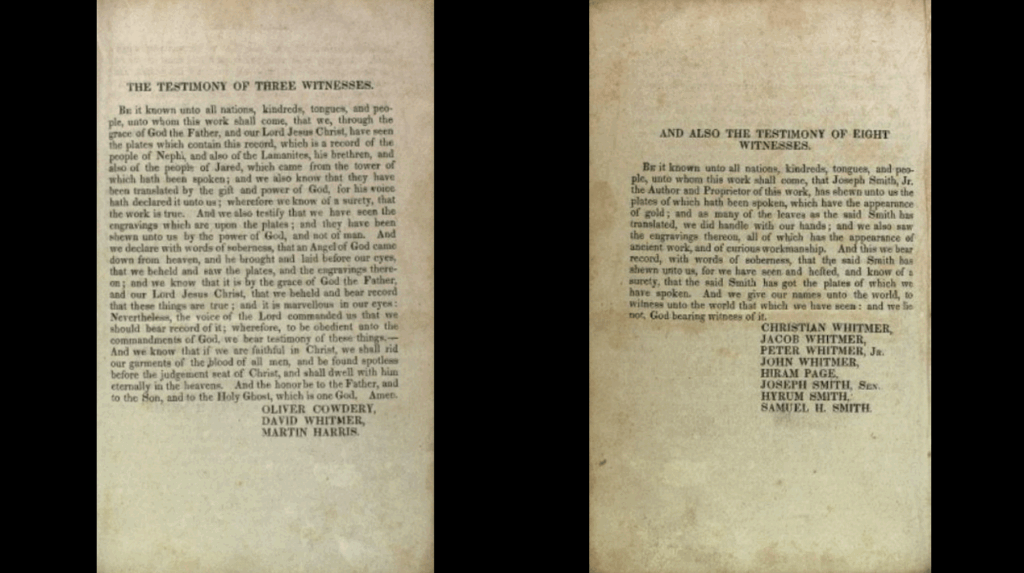

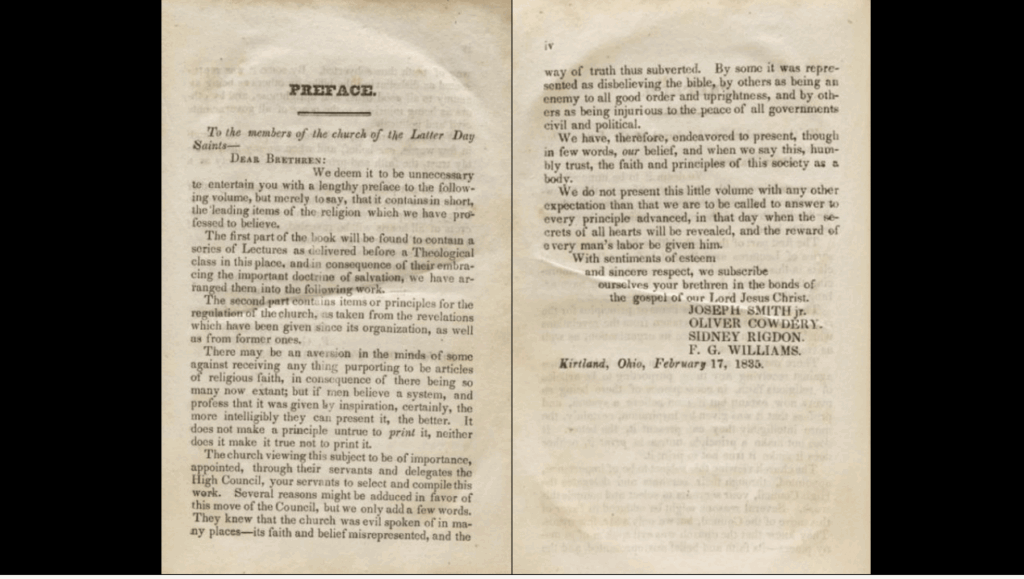

Attribution

However, the word plagiarism means borrowing without attribution. Smith never published the JST as he had planned, so we do not know how he would have presented it. Each of the books of Church scripture published in Joseph’s lifetime includes introductory material providing some explanation for the book’s contents. If the JST had been published, it likely would have included such an introduction, like the other books of Church scripture. Such an introduction may well have given some kind of attribution to Clarke or to outside sources generally. Since we don’t know whether Joseph Smith would or would not have attributed any outside sources, the detractors’ charge of plagiarism, of borrowing without attribution, requires jumping to a conclusion.

Okay, that’s the overview.

And actually, I talked about the book and the plagiarism issue on the FairMormon blog just last week. And I think where the book is set to get roasted next week on the Fair Voice podcast, which is fine because, because you know, you got to have a thick skin in this business. So, let’s look at this article then.

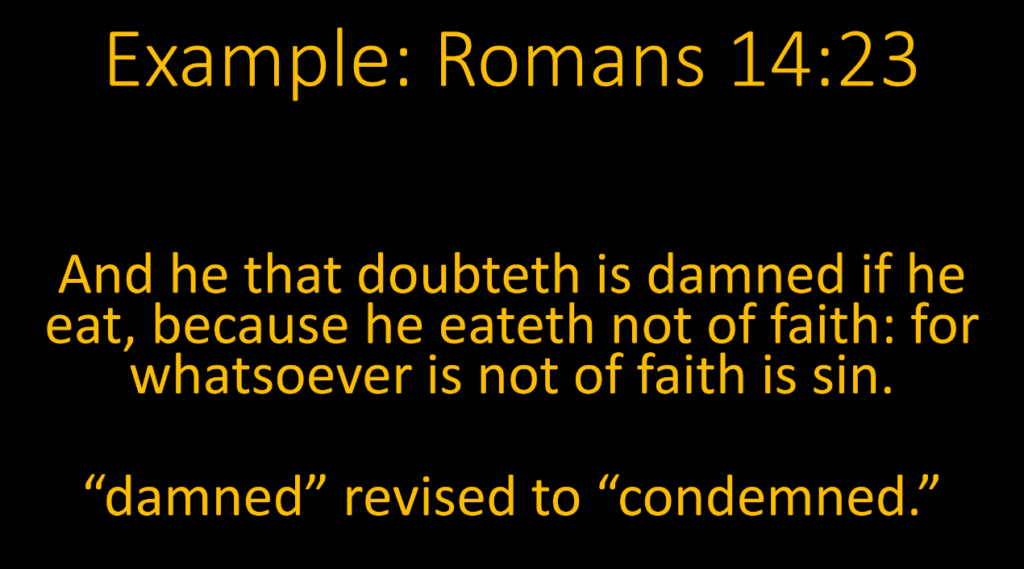

“And he that doubteth is damned if he eat, because he eateth not of faith: for whatsoever is not of faith is sin.” JST revises “damned” to “condemned.” This is the exact same change advised in Clarke’s commentary. So if you eat the wrong thing at the wrong time, you’re not absolutely going to hell forever.

Here’s a third example from Romans 11:2. “Wot ye not what the scripture saith of Elias? How he maketh intercession to God.” In the JST, “intercession” is revised to “complaint.” This is the same change recommended by Clarke in his commentary.

So we’ll look at one more that’s kind of interesting and fun that you might be familiar with, which is that in the JST, the Song of Solomon is rejected as uninspired. That’s kind of interesting because Clarke argues strongly against the Song of Solomon. He says, you know, this is erotic love poetry and it doesn’t say anything about Jesus or the gospel. And he essentially rejects Song of Solomon, and the JST does as well.

Parallel Text

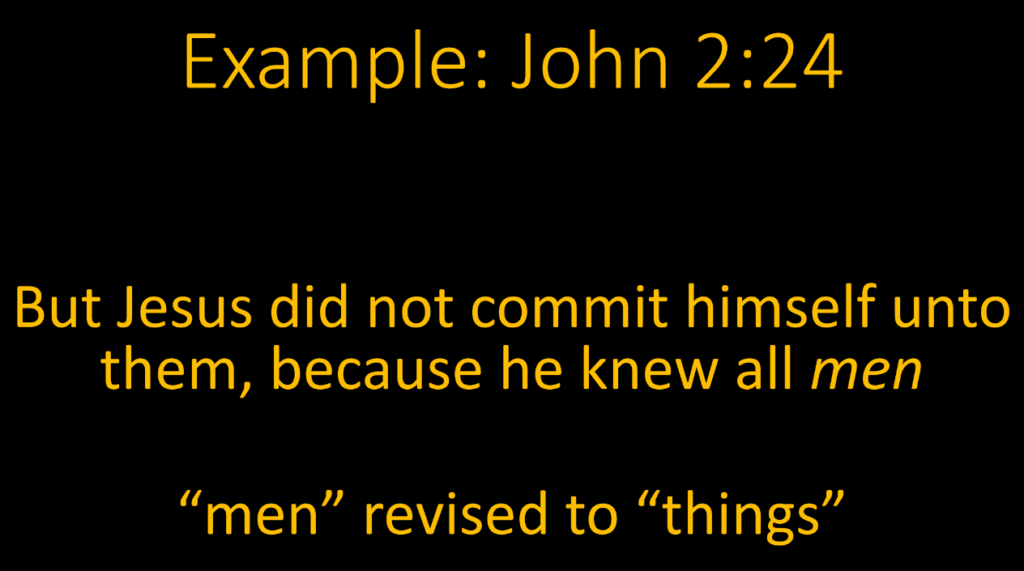

So, there’s a few examples. There’s many more. I’m not going to keep going–just want to give you a bit of a taste of that, and I’ve picked examples that make for simple slides, but there are many examples like that. I reckon that there’s going to be other scholars that come forward and really push back against this idea that the JST is using Clarke; I’m looking forward to seeing that scholarship. I’m not sure if this is absolutely proven, but there’s definitely a pretty persuasive set of parallels, and so it looks like a plausible scenario that we need to look at and deal with.

Okay, so back to the article. In this chapter of the book, they lay out several of these different examples of parallel text, and I’m gonna go to some of their conclusions in terms of what they make of all this.

So here’s part of the conclusion:

A careful analysis of the revisions made throughout the Bible confirm a genuine difference between the changes to Genesis 1:1 through 24:41 and the remainder of the Bible revision. The difference may be explained by a change in the mechanics of the translation process. In short, it may have shifted from a more revelatory mode to a more secular mode.”

I’ve gone through the whole JST, and that pattern is pretty obvious.

They also point out that in the large expansions of material about Moses and Enoch and the last days in Matthew chapter 24, those are pretty obviously intended to be understood as revelatory restorations to the Bible, or revelatory additions to the Bible, at least. And Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon did not find any trace of Clarke’s influence in those major expansions that we have canonized in the Pearl Great Price, so that’s noteworthy.

Wilson-Lemmon

And here’s another part of their conclusion:

The echoes of one of Smith’s earliest revelations in which the voice of the Lord admonished Oliver Cowdery to ‘study it out’ as part of the translation process are now much more obvious in Smith’s Bible translation process. This encouragement to ‘study it out’ could mean more than simple mental exertion. It could be an informed mental engagement with all available resources within and without the mind and one that eventually relied upon actual study in available published resources. Joseph Smith leaned into the logic of the revelation.”

Alright, so those are their conclusions at the end of this chapter in the book. And now we’re going to talk about the parting of the ways between these two co-authors; and we’ll start with Haley Wilson-Lemmon.

This is her graduating from Brigham Young University.

Wilson-Lemmon has left the Church, has been speaking out on anti-Mormon or ex-Mormon or critical post-Mormon websites, podcasts, and she has been calling Joseph Smith’s use of Adam Clarke’s commentary ‘plagiarism.’ So let’s just see exactly what this issue is that we’re addressing. The fact of the matter is that this plagiarism thesis is not simply coming from Wilson-Lemmon. This thesis is actually constructed in the dialogue between Wilson-Lemmon and the podcasters. So I just want to look at that and show you exactly how this is working.

Reel: I want to ask if you could maybe give us a feel for just how much Joseph is directly borrowing, and for the sake of this conversation, I think it’s fair to say plagiarized.

Wilson-Lemmon: Yeah, it is.

Reel: And I think plagiarism would have been a much different understanding than in today’s scholarly way of seeing plagiarism, but let’s just use the word plagiarism. Can you give us a feel for just how much plagiarism Joseph is doing with the Joseph Smith Translation using Clarke’s commentary?

Wilson-Lemmon: He plagiarized Clarke about 30 times in his New Testament translation, and there’s about 15 direct parallels in the Old Testament. There’s a lot.

Reel: And to go one step further, Joseph Smith would have plagiarized from Adam Clarke ideas that Clarke had that may not be up to par with the best scholarship today.

Wilson-Lemmon: Yeah.

Reel: . . . or even accurate if we just say . . . like truth and error.

Wilson-Lemmon: Yeah, that’s fair.

Reel: Right.

So, you can see how the thesis is actually constructed in the dialogue between Wilson-Lemmon and her interlocutors. Then you have, after the interview, you have the packaging, okay? So here, for example, is the title of this podcast that I’ve just given you excerpts from, Episode 299, Haley Lemmon: The Joseph Translation – Revelation or Plagiarism?

Mormon Stories Interview

Okay, and then the little preface to the interview has this:

The major discovery here was that Joseph Smith directly borrowed or plagiarized heavily from Adam Clarke’s commentary in order to carry out his Bible translation. There is a multiple of tangents we can take this conversation. What led to this research? How pervasive this plagiarism was.”

Okay, so now we’re going to look at the other major source of the plagiarism thesis, which is Wilson-Lemmon’s podcast interview on Mormon Stories. Okay, again, we’ll see how the thesis is constructed.

Dehlin: From this article you talk about various types of plagiarisms or borrowings. I don’t think the term plagiarism is used in the article, but . . .

Wilson-Lemmon: No, but . . .

Dehlin: . . . I talked to you beforehand, you’re okay using that term.

Wilson-Lemmon: Yeah.

Dehlin: . . . and I’m okay using that term because we know Joseph Smith plagiarized in the Book of Mormon . . .

Wilson-Lemmon: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Dehlin: . . . and you know, elsewhere.

So really quickly, why . . . what makes this plagiarism, you know, we talked about that before. What about this qualifies it in your mind as plagiarism?

Wilson-Lemmon: So . . . honestly, it’s the sheer number of examples . . . uh . . . just the sheer amount . . . of . . .

Dehlin: I mean, I guess he’s not . . . citing it and telling us where . . .

Wilson-Lemmon: No, he’s not!

Dehlin: . . . where . . . what his source is, right?

Wilson-Lemmon: Yeah, I mean, and obviously, you know, 19th century plagiarism ideas are different from our modern sensibilities of plagiarism. I mean, probably to him, he wasn’t. I don’t know, who knows what he was thinking, but yeah. So the sheer number of instances makes it plagiarism, but I also think the implications of some of these changes, like the implications that Joseph Smith was relying on an outside source to do something that he claimed was an inspired act, I think is what ultimately kind of makes it such a big deal, right?

Dehlin: Yeah, he’s claiming it’s from the gift and power of God, and he’s not giving the source where it comes from.

Wilson-Lemmon: Yes.

Dehlin: Yeah.

Dehlin: The other word for that is plagiarism, right?

Wilson-Lemmon: Yes, yes.

Interview Continued

So again, you can see how it’s not just Wilson-Lemmon, it’s really the dialogue between the two. And let me just say really quickly, I made as exact transcripts of this as I could, and so that’s why it has like the uhs and the ums and the mumbles and burbles and stuff. And I think I probably right now, I’m doing that more than they do, so, this is not to try to make them look bad. Don’t let that be a red herring, okay?

Alright. So then, at the end of the interview, Dehlin’s kind of like talking about the conclusions of the chapter, and he says:

Dehlin: So you do just basically say without saying Joseph Smith engaged in a lot of plagiarism when he created the Joseph Translation. Now, I don’t think Thomas Wayment would use that word, but that’s your conclusion.

Wilson-Lemmon: Yeah.

Dehlin: Yeah.

Okay, now let’s, those are the main excerpts, let’s go to the packaging. Episode 1338, Haley Wilson-Lemmon: The BYU Undergrad Who Discovered Joseph Smith’s Plagiarism in His Bible Translation. And here’s the preface,

In the summer of 2015, something truly remarkable happened. A BYU undergraduate, along with her professor, discovered yet another example of plagiarism on the part of Joseph Smith–this time in the canonized Joseph Smith Translation.

Join me and scholar Haley Wilson-Lemmon today as we discuss this groundbreaking research she conducted at BYU alongside Professor Thomas A. Wayment . . . as together they discovered literally hundreds of instances where Jesus would plagiarize portions of the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible directly from Adam Clarke’s Bible commentary.”

Ten Questions Interview

Okay, so that’s Haley Wilson-Lemmon. Now let’s talk about the path followed by Thomas A. Wayment.

Let’s start with his Ten Questions interview with Kurt Manwaring for the From the Desk series sponsored by BYU Studies. In this interview, Wayment says,

When news inadvertently broke that a source had been uncovered that was used in the process of creating the JST, some were quick to use that information as a point of criticism against Joseph or against the JST. Words like “plagiarism” were quickly brought forward as a reasonable explanation of what was going on. To be clear, plagiarism is a word that, to me, implies an overt attempt to copy the work of another person directly and intentionally, without attributing any recognition to the source from which the information was taken.”

And then he says that the way he looks at it,

to the best of my understanding Joseph Smith used Adam Clarke as a Bible commentary to guide his mind and thought process to consider the Bible in ways he wouldn’t have been able to do so otherwise. Joseph didn’t have training in ancient languages or the history of the Bible, but Adam Clarke did. And Joseph appears to have appreciated Clarke’s expertise and in using Clarke as a source, Joseph at times, adopted the language of that source as he revised the Bible.”

Gospel Tangents Podcast

OK, now let’s go to his Gospel Tangents podcast.

Wayment says,

It’s conclusive that Joseph Smith used Adam Clarke, and when I say used, I want to stick by that term.”

So he’s addressing the plagiarism issue here. This isn’t him simply saying,

Okay, here’s three sentences in Clarke. I’m going to copy it out and call that inspiration. It’s not that. He has some words that come from Clarke, that now come into a kind of expanded sentence that Joseph has created.”

Okay, now we’ll go to his recent article in the Journal of Mormon History, Joseph Smith, Adam Clarke, and the making of the Bible Revision.

In the article, he focuses a lot on the labor-intensive process of the JST, with Joseph Smith working with his scribes and how they were marking up a Bible with changes and some of the dynamics there. And he also talks about the kinds of changes that are made that appear to be related to Clarke, and shows how the use of Clarke is very selective, and how the use of Clarke is often adapting what’s there. So he really presents it more in terms of a critical utilization as opposed to massive hunks of direct borrowing or plagiarism.

Plagiarism Through Time

Alright, so let’s talk about this framing in the first place. If we’re framing this kind of borrowing as plagiarism, is that problematic? We’ve already kind of covered some hints that the word ‘plagiarism’ has connotations that have changed over time, and it was different in the culture of Joseph Smith’s time than it is today where we have such common college education and journalism standards, and things have changed a lot there. But it is a word in Joseph Smith’s world. Okay so here it is in the 1828 edition of Webster’s dictionary.

“Plagiarism–The act of purloining another man’s literary works,” (so you’ve got some sexism there, fitting the time) “or introducing passages from another man’s writings and putting them off as one’s own; literary theft.” So it is a word in Joseph Smith’s culture, not entirely different from our current understanding. But then there’s the issues of what actually constitutes plagiarism in our culture and what actually was considered plagiarism in Joseph Smith’s time.

Bricolage or Repurposing

Okay, some other ways to think about this are offered in this new book, The Pearl of Greatest Price by Terryl Givens with Brian Hauglid. Givens talks about this concept of bricolage. Givens is kind of a historian of western civilization and culture and literature, and he talks about how everything is always influencing everything. Everyone’s always recycling and remixing things. They break down parts and rearrange them in different ways. This is a concept that the anthropologist or sociologist Levi-Strauss calls bricolage, and Givens talks about that.

Okay, here’s another recents treatment that is a different way to look at this. Sam Brown’s new book, Joseph Smith’s Translation. And he recently just did a 10 questions interview and in the last chapter in that book, he talks about the Mormon temple endowment and some of the elements of freemasonry that appear there. There’s a great quotation there where he kind of explains this idea.

There’s definitely a thread of repurposed masonic ritual in the endowment, but the masonic component is more like several pieces of brightly colored string in a robin’s nest, rather than the entire structure. We shouldn’t confuse components with the whole.”

In logic that’s the fallacy of division, that what’s true of the whole is also true of the parts. Or the flip side of that would be the fallacy of composition, what’s true of the parts is true of the whole.

William Blake

Okay, now I’m going to talk about one more idea here. This is from Steve Fleming’s dissertation where he’s talking about E.P. Thompson’s evaluation of the sources of inspiration drawn upon by William Blake. Blake never cites any sources of inspiration, so there’s lots of scholarly literature kind of battling over what influenced him or what inspired him.

You’re probably most familiar with his art from Blake Ostler’s Mormon Theology series.

So this is E.P. Thompson on Blake:

We have become habituated to reading in an academic way. We learn of influence, we are directed to a book or a reputable intellectual tradition. We set this book beside that book. We compare and cross refer. But Blake had a different way of reading. He would look into a book with a directness which we might find to be naive or unbearable, challenging each one of its arguments against his own experience and his own system. He took each author, even the Old Testament prophets, as his equal or as something less, and he acknowledged as between them; no received judgements as to their worth, no hierarchy of accepted reputability.”

So this kind of explains how Blake has this different way of reading, and maybe, almost like kind of a prophetic posture where he’s considering himself standing shoulder to shoulder with the prophets and measuring everything against this inner spirit of truth inside of him. It kind of makes sense why he never cites anybody. This is kind of a different way to look at the issue.

Types of Revisions

Another problem with the plagiarism thesis and most critique against the JST is that it sets up a straw man of what Latter-day Saints are supposed to believe the JST is.

So let’s just go to the Bible Dictionary really fast. “Joseph Smith Translation (JST)–A revision or translation of the King James Version of the Bible.”

Here’s another example. Robert J. Matthews quoted in the Ensign magazine, the Church periodical, “The translation was not a simple mechanical recording of divine dictum, but rather a study and thought process accompanied and prompted by revelation from the Lord.”

So revelation prompts Joseph Smith to enter into this study and thought process, and as he’s doing the study and thought process he’s accompanied by revelation from the Lord, but it’s not ruling out the possibility of any little change not being a direct result of pure revelation with no thought in his own mind.

Modernization

So let’s get into the nitty-gritty on this for just a few minutes so you can see what I mean when I talk about mundane changes or modernizations. Okay, so here is just one simple example.

This is the JST from Mark 12:32. “There is one God; and there is none other but he.” And in the JST Joseph Smith changed “he” to “him.” “There is one God and there is none other but him.”

There are hundreds of exchanges like this in the JST. Must we assume that when Joseph Smith changed he to him, he meant for us to understand that change as a result of pure revelation? That’s the question.

I recently went through the JST, so this made a huge impact on me. There’s several examples of modernization where he’s taking 17th century King James English and making a modern adaptation for 19th century Latter-day Saints; changing thee to you, changing thou to you, changing ye to you.

There’s about 82 instances of changing ye to you. Do we have to believe that every single one of those instances of changing ye to you must be a direct result of revelation and that Joseph Smith means for us to accept it that way?

Okay let’s look at some more. Wotteth to knoweth, wot to know, wist to knew,

holpen to helped, dwelt to dwelled, shalt to shall,

draweth to draw, seeketh to seek,

spake to spoke, gat to got, bewrayeth to betrayeth,

hath to has, hast to has,

afore to before, aforehand to beforehand,

alway to always, amongst to among.

And again, there are hundreds of these. I made a register of all of these. By my account there’s over 1200 changes like this. Do we have to assume that Joseph Smith, when he changed amongst to among, that every time he did that he meant for us to understand every single instance of change like that to be the result of pure revelation?

Editorial Decisions

I think it’s theoretically possible that Joseph Smith saw the whole JST as inspired in terms of being generally inspired to modernize all these hundreds of words. But in terms of each individual change, while it’s theoretically possible that every single little change like this is a product of pure revelation, I and others actually think it’s as much or more plausible that this is Joseph Smith making some minor changes in the Bible. And if that’s the case, what that means is that the JST is a combination of both divine revelation from God to Joseph Smith, and Joseph Smith’s own editorial decisions.

This is crucial because if Joseph Smith is himself, on his own, the source of some of the changes in the Joseph Smith Translation, now you have to look at him in his environment, because Joseph Smith’s mind is not hermetically sealed off from his family and friends and his acquaintances. It’s not sealed off from interactions with other people, like his scribes. We know that Joseph Smith discusses the Bible with other people. There are many examples of that. And we have good reason to believe that Joseph Smith is discussing things with his scribes as they’re working on the JST.

Social Revision

One case in point is Doctrine & Covenants 76. If you read the introduction to Section 76, the vision of the three degrees of glory, in the History of Joseph Smith, it’s not totally explicit, but they’re apparently having a conversation about the meaning of John chapter 5 verse 29. So a revelation comes from that, but before the vision comes, they’re doing the JST and they’re talking about what passages mean. So if Joseph Smith is, himself, a source for some of the changes in the JST, that means Joseph Smith in his interpersonal relationships with his scribes, and perhaps others, is working on the JST.

And it goes beyond these interpersonal relations with scribes, because Smith and his scribe are part of a wider religious culture. So they’re part of a wider oral culture of Church meetings and preaching and expounding from the Bible. And they’re part of a wider literary culture of tracts and pamphlets and religious newspapers and books that have biblical exegesis in them, or Bible commentaries.

And so once you can accept that Joseph Smith himself is a source of the JST, you can see how much sense it makes for if it is him making a change, that’s him making a change in the culture, in the total environment of his own thoughts, of his conversations with scribes and others, and in the wider culture of sermons and biblical exegesis; which can include printed sources.

Did Joseph Smith and his scribes consider themselves forbidden from looking at any Bible commentaries? It just doesn’t make sense to try to seal off Joseph Smith from his culture. In fact, it makes a lot of sense for Joseph Smith, as you’re working on the JST, to be reading the text, thinking about the text, discussing the text, and maybe even reading other things.

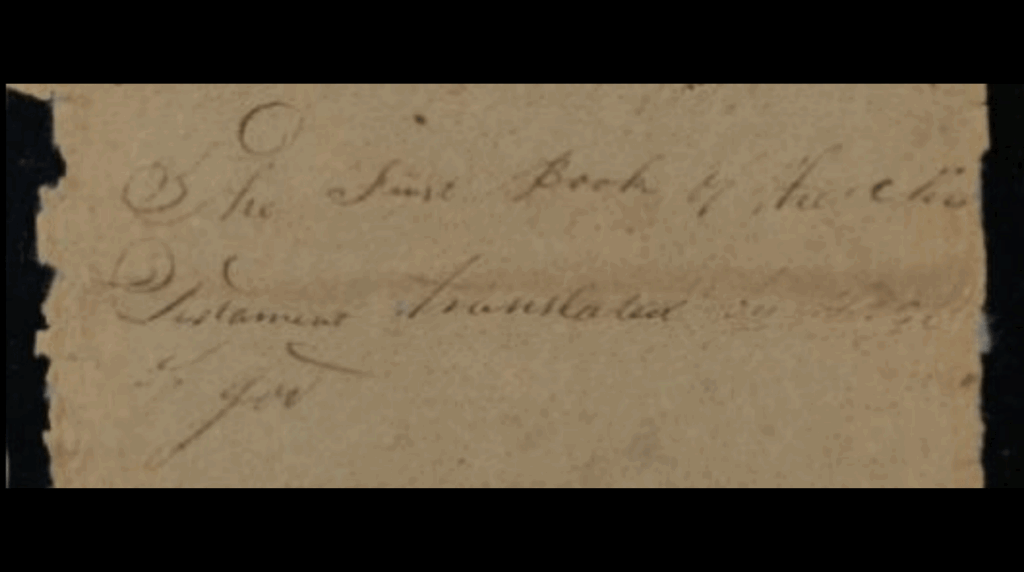

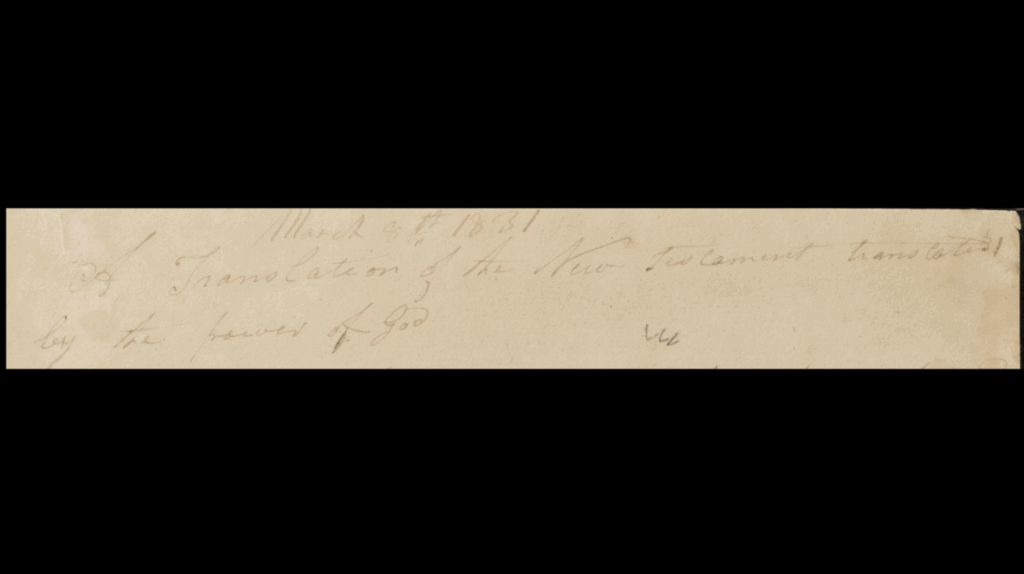

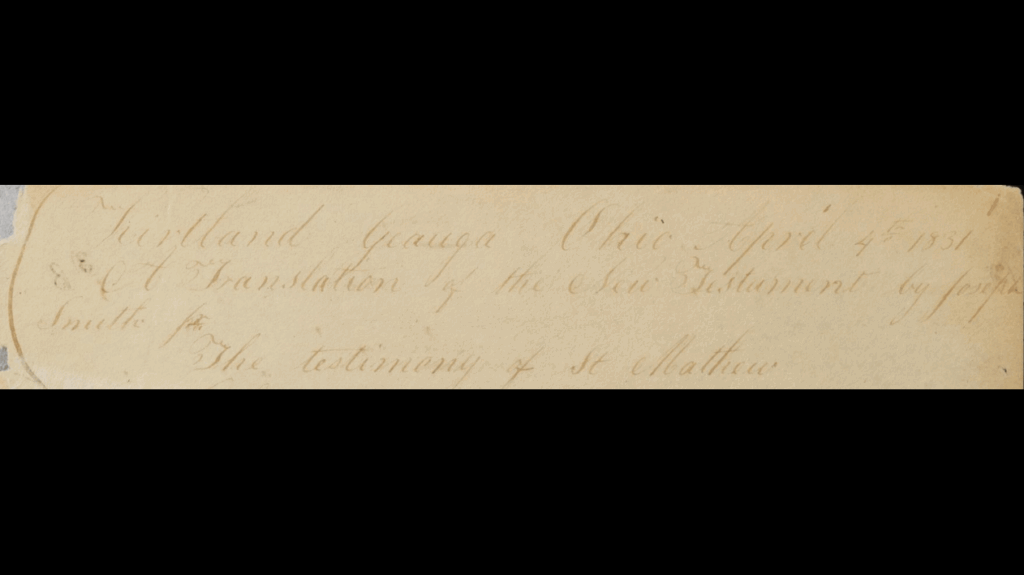

Okay, so let’s compare those. “A Translation of the New Testament Translated by the Power of God.” That’s it, that’s the New Testament One Manuscript Headnote. And the New Testament Manuscript Two Headnote: “A Translation of the New Testament by Joseph Smith.”

Okay, now, we could make too much of that. The second title, I don’t think, is implying that they no longer consider the JST to be a product of revelation. But the timing between New Testament Manuscript One and Two is around the time when Joseph Smith finishes the major expansions in Genesis, and they move to the New Testament and start comparing the synoptic gospels, and apparently, this is around where they start using Clarke. So, it’s possible that this revised title does reflect a changed understanding of the project. And again, you can make too much of that, but this is an interesting change that may reflect the change that does happen in the JST process.

Early Church Publications

Okay, I’m just going to say that working for the Joseph Smith Papers Project, I’m familiar with many books like the Scriptory Book, the Book of the Law of the Lord, where a book starts, it receives a title, and as the project goes along, the nature of the methodology of documentary production changes.

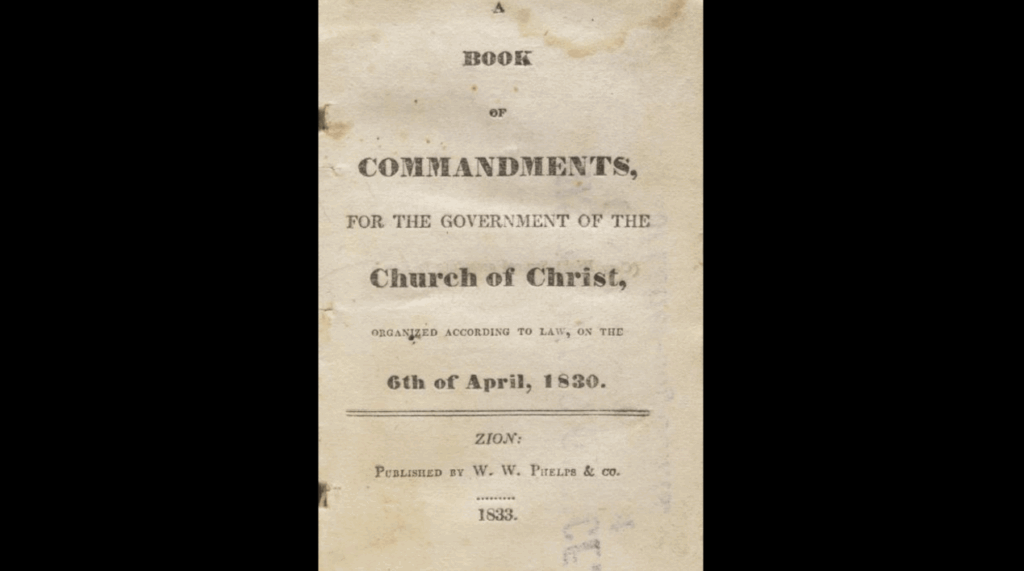

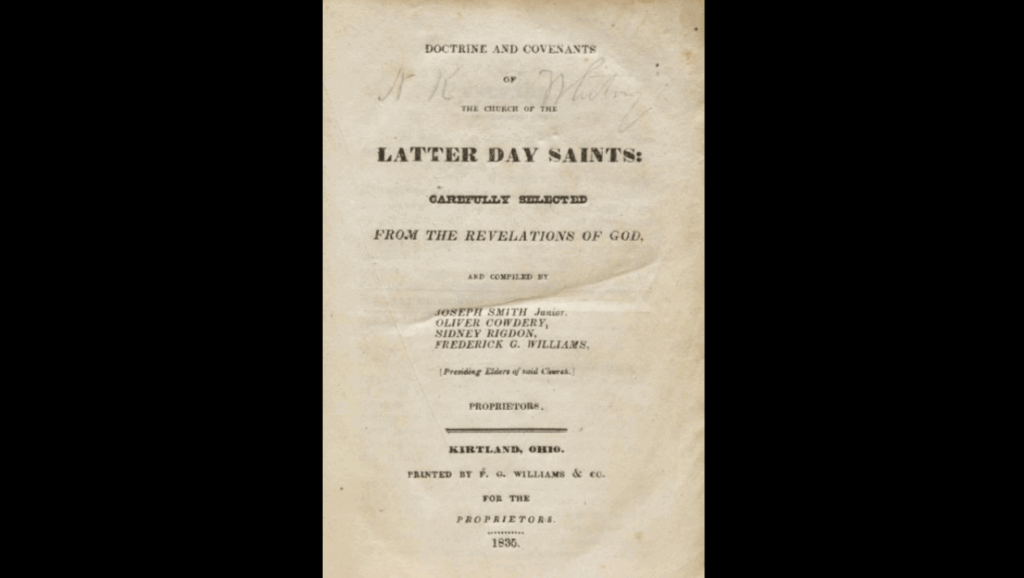

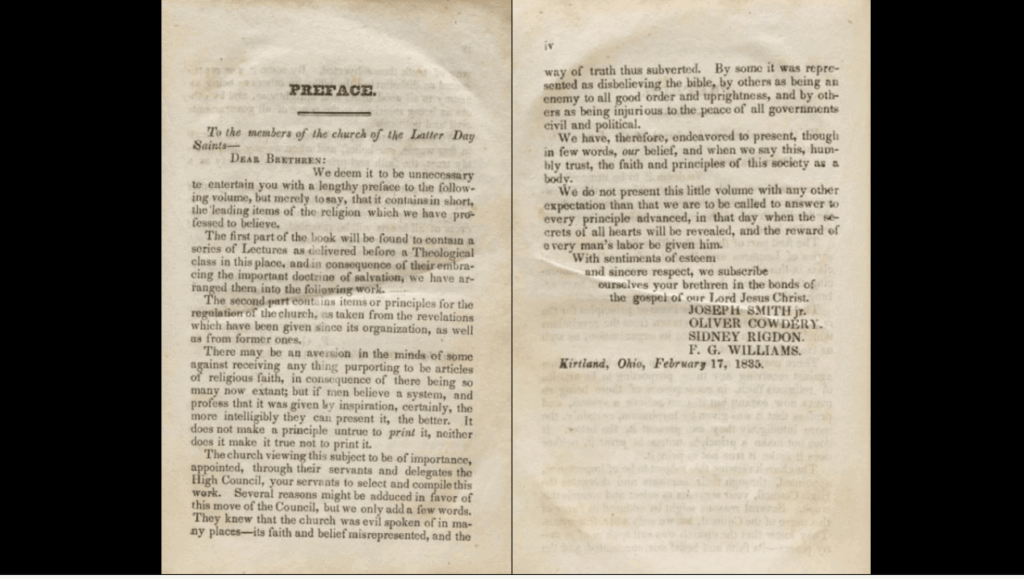

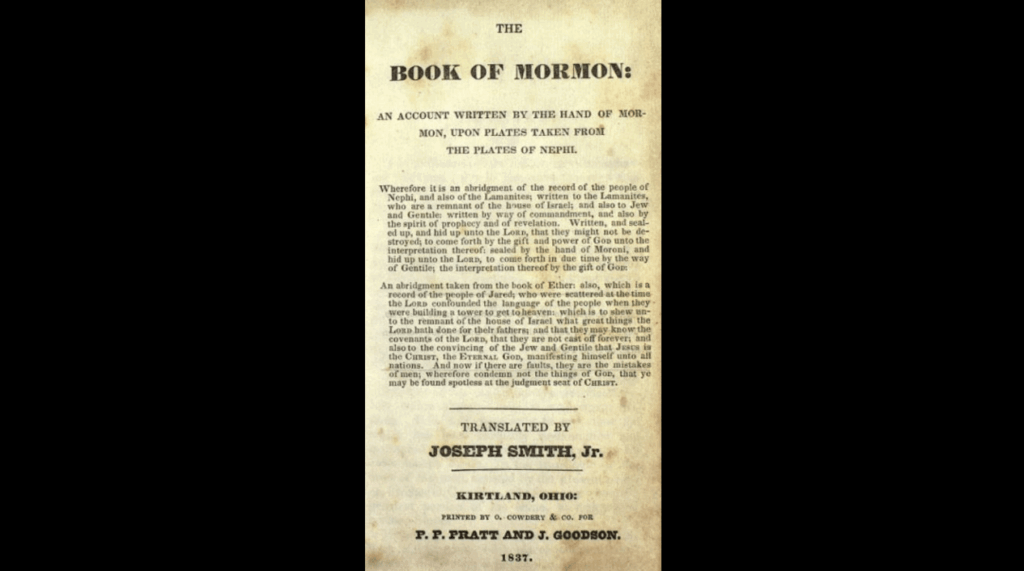

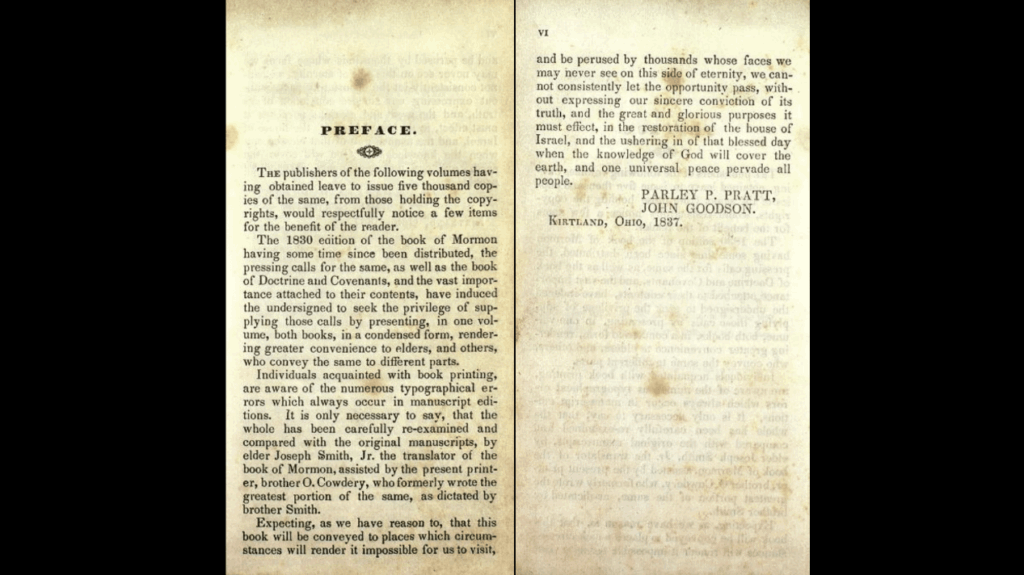

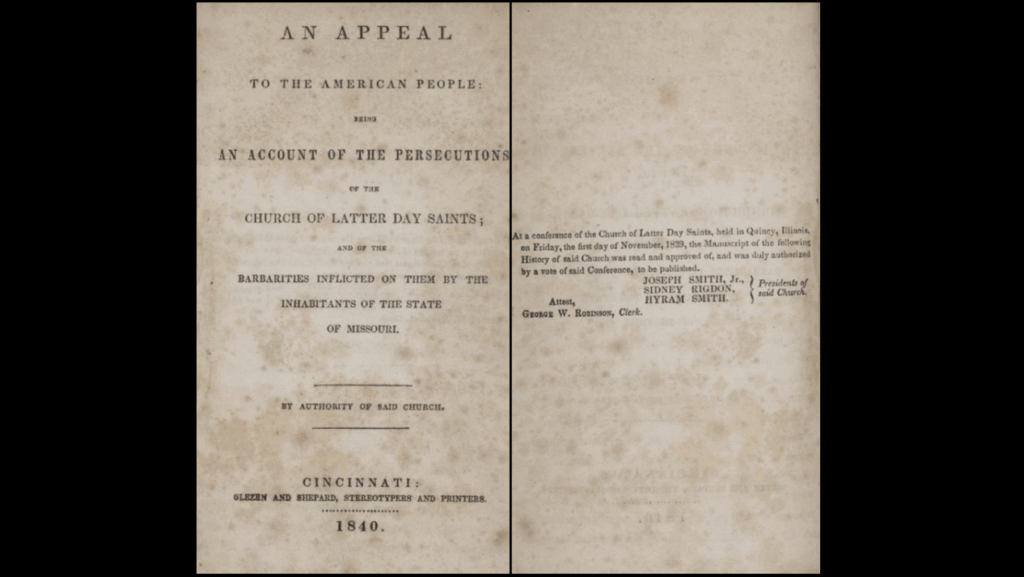

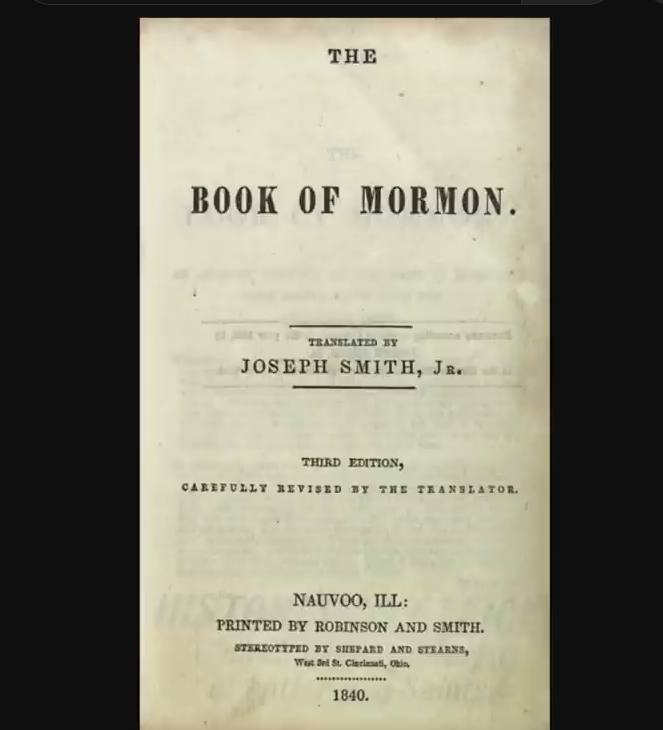

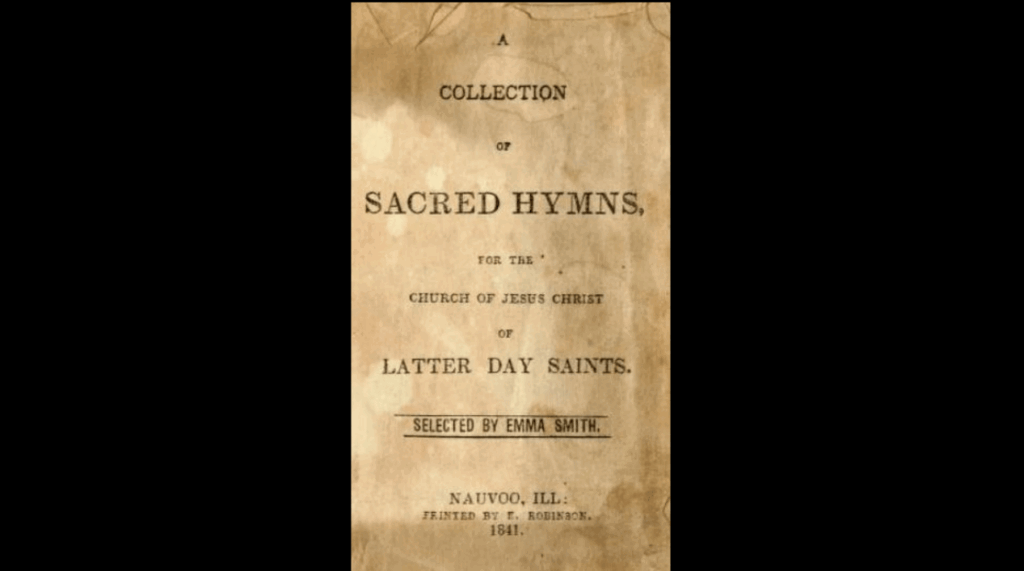

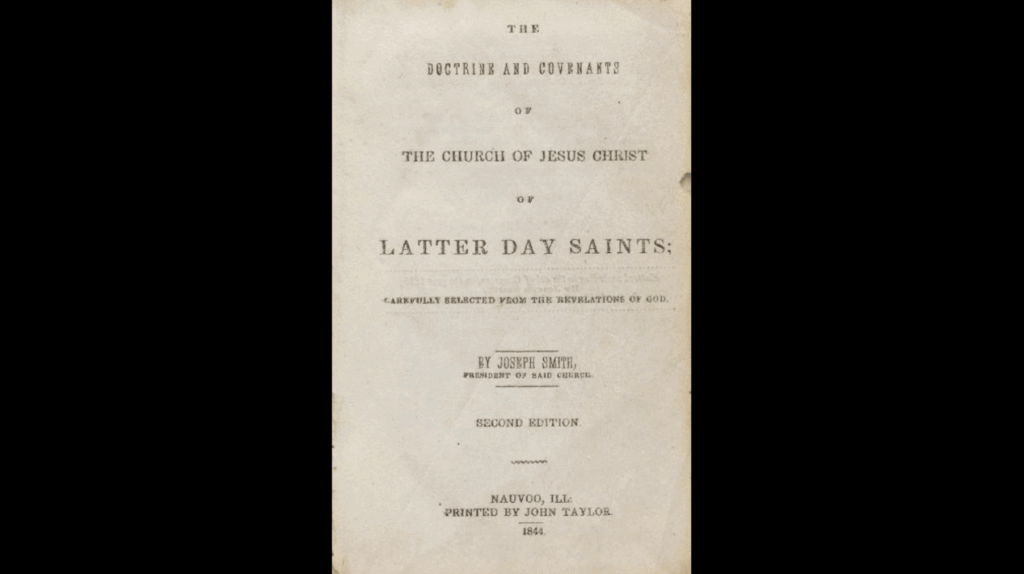

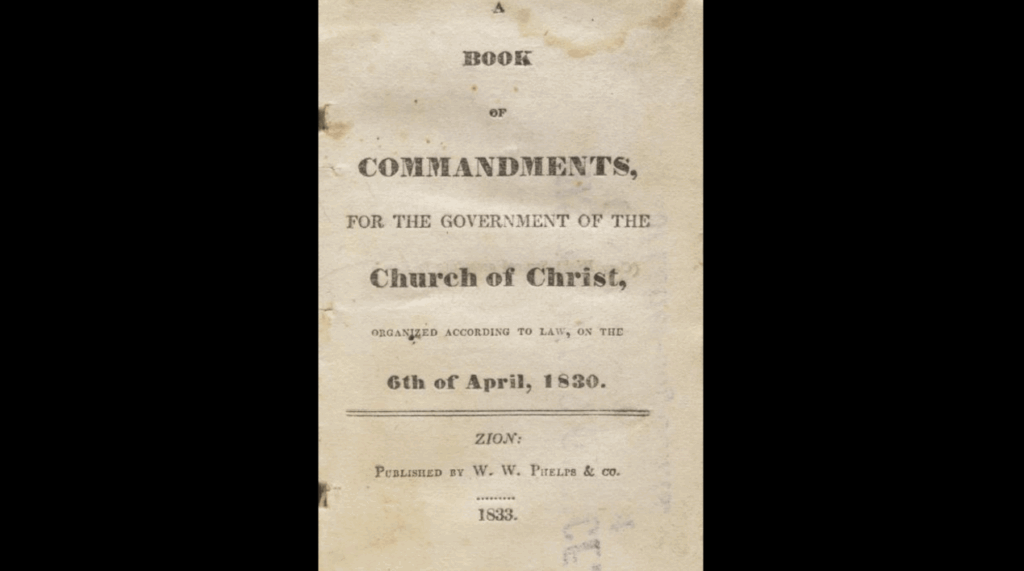

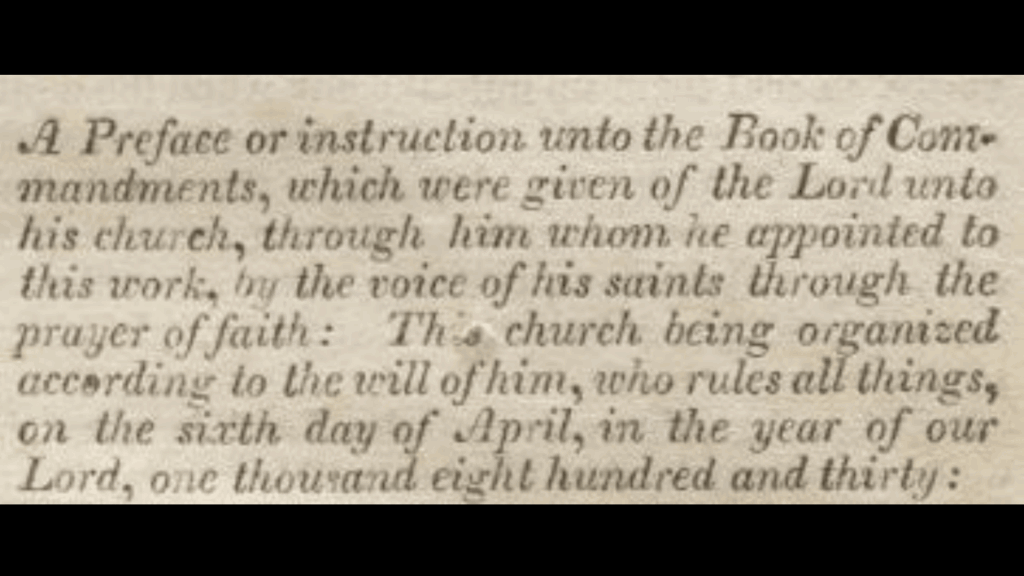

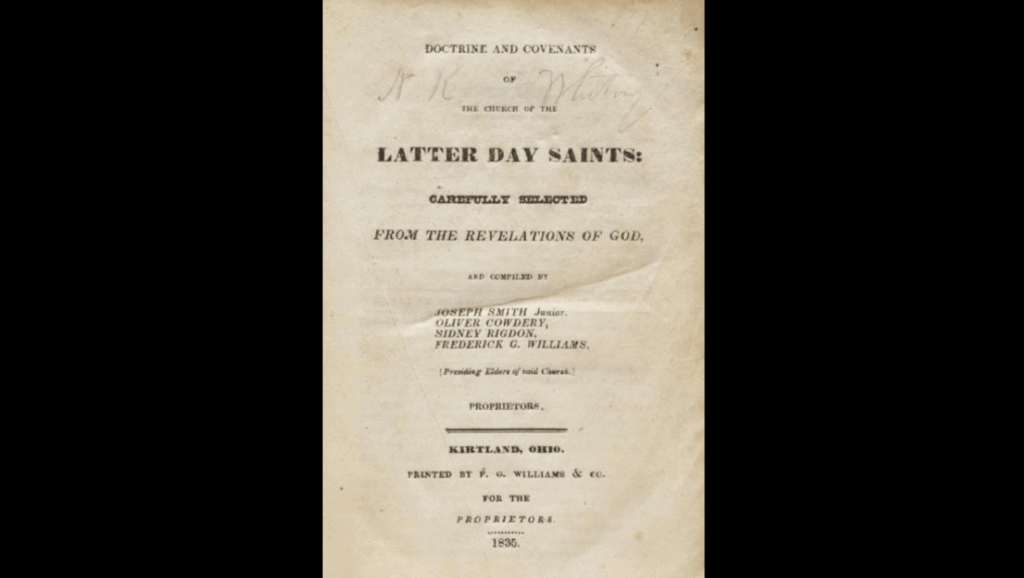

Okay, now quickly, we’re going to run through the context of early Church publications. And this is what I really think maybe I can add to this discussion. Everything we’ve talked about so far, a lot of people are kind of getting at, Wayment is getting at himself and other commentators, but this is something new that I think is worth looking at, and that is the context of early Church publications. We’re going to do this really fast.

Again, no preface.

Patterns in the Books

These are all of the Church books published in Joseph Smith’s lifetime.

Okay, if there’s a pattern there, maybe it’s that Church books have prefaces and then when they’re reprinted, they have a slightly longer preface, and then in the third edition, the prefaces get dropped for some reason. I don’t know why, but maybe it’s because these books now have a reception history in the community and people know what they are.

So looking at the Book of Mormon and the D&C, if the JST was published, it would probably have a preface like these other books. Maybe it would be like the Book of Mormon where it says this is revelation. But another possibility is it’s going to be something like the D&C preface where it says some of this is divine revelation and some of this is theological explication.

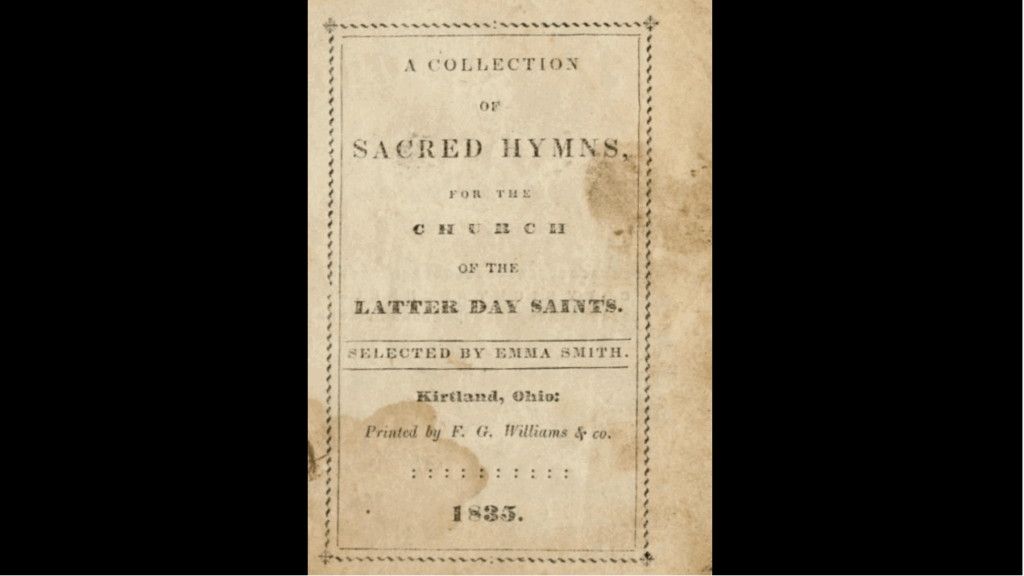

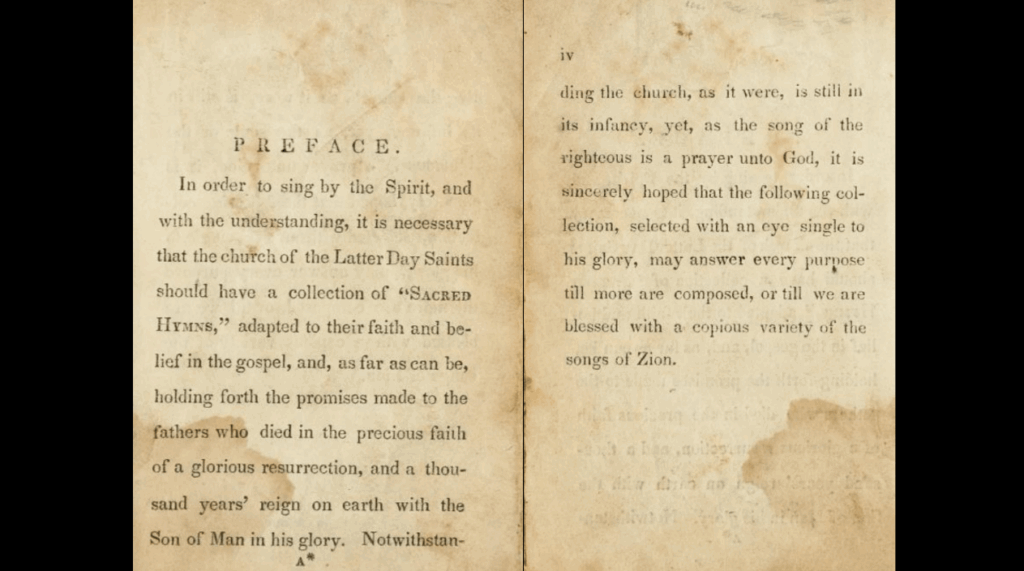

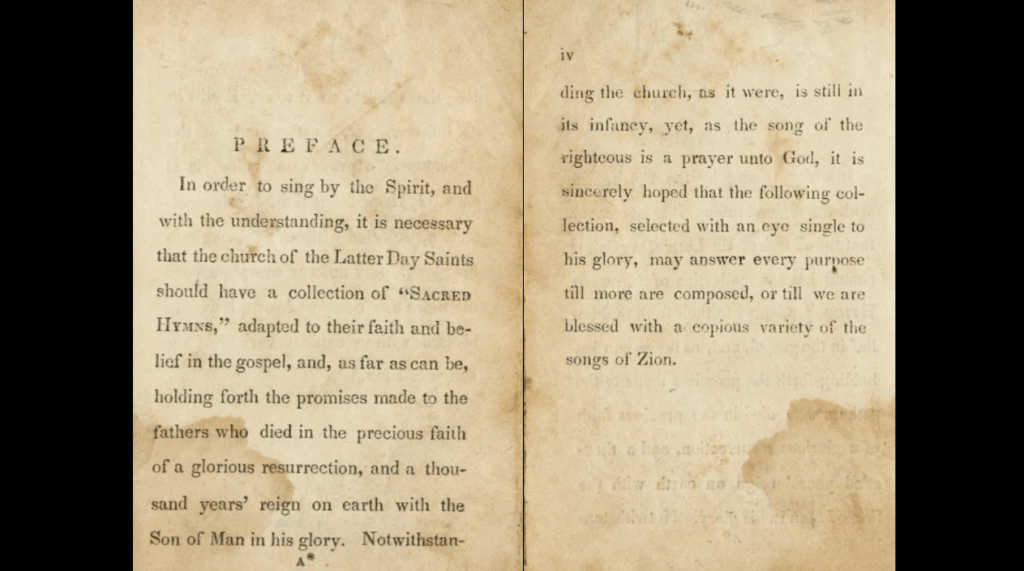

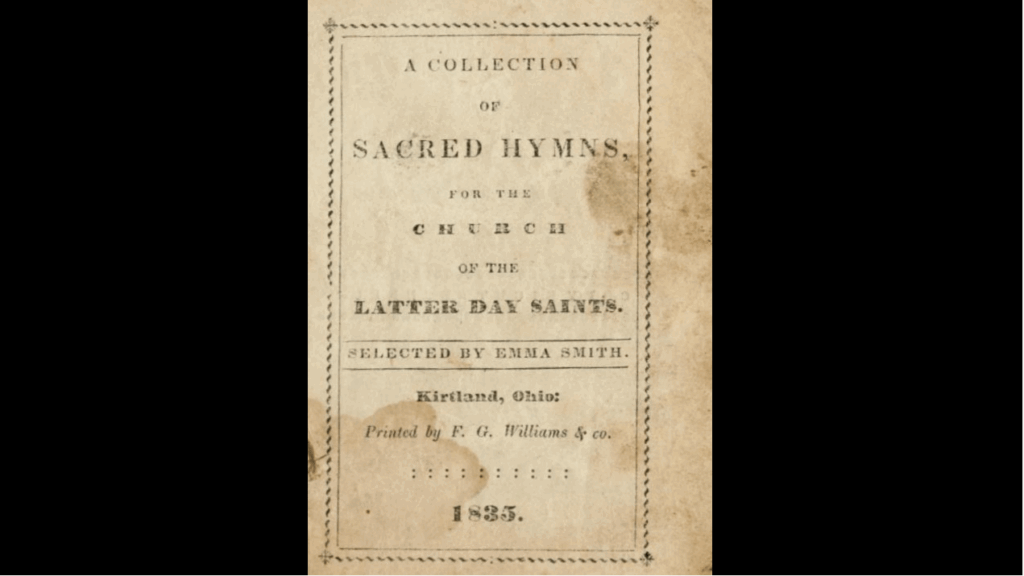

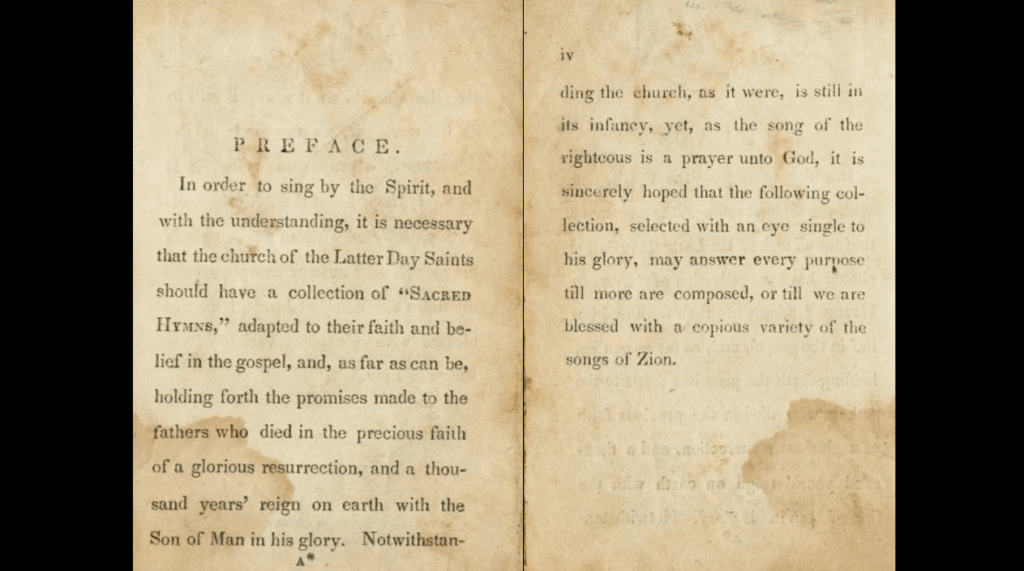

And the preface to the hymnal explains that the hymnal has a few songs of Zion, which are songs written by Latter-day Saints for Latter-day Saint worship. And it says, we hope in the next edition of the hymnal, we’ll have more of these songs of Zion. The rest of the hymns in here are presumably borrowed from other hymnals, and the preface says that some of them have been adapted to their faith, the Latter-day Saints’ faith, and belief in the gospel, and that could be demonstrated, how some of the hymns are adapted.

Audience Q&A

Scott Gordon:

So, a few questions. The first question has to do with the general assumption about the Joseph Smith translation, and you addressed it somewhat, but I’m going to ask you a different way. I’m looking at a copy of the Letter to a CES Director, and he talks about “The Book of Mormon includes mistranslated biblical passages that were later changed in Joseph Smith’s translation of the Bible. These Book of Mormon verses should match the inspired Joseph Smith translation instead of the incorrect King James version, which Joseph Smith later fixed,” and he gives some examples. Now, there’s one problem in the letter: the examples that he gives, he’s matching the wrong verses. In other words, he says, “Look, they don’t match,” that’s because it’s actually the wrong verses he’s matching. But what do you think about his underlying premise that Joseph’s mistranslation of the Bible is the inspired version, should therefore, at least seems to me he implies, should be the perfect translation of what should be in the Book of Mormon and such.

Mark Ashurst-McGee:

So, my point of view there would be, the Book of Mormon does not present itself as perfect. It does present itself as a scribal tradition that has been kept more pure than what the Bible’s gone through. But at the same time, it’s absolutely explicit that it contains mistakes of men, and that’s what’s on the golden plates. And after the long, massively complex, transmission history of Nephite records, you also have the translation issues with Joseph Smith.

And I’ve talked about what I think is a different but related set of translation issues with the JST. And so, I just don’t really see a problem there, and I think that thinking that way is problematic.

Now, growing up in the Church, going to Sunday school and seminary, it’s easy to inherit a simple view like that, but I would emphasize that Church historians and scripture scholars have been showing the more complex reality for decades, to the point where this is filtered into the Ensign magazine, as I showed, and the Bible Dictionary, which is printed in our scriptures. So, I feel like here today I’m just trying to add to that and help us have a more developed understanding of the JST.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you. Next question is, since we know the JST was a collaborative effort with the participation of Sidney Rigdon and others, how much can we confidently ascribe the use of Clarke specifically to Joseph himself, as opposed to other participants in the project? In other words, could the use of Clarke have come through Rigdon or another participant, or is this distinction between the participants too atomizing and not warranted?

Mark Ashurst-McGee:

So, this is a hypothesis that’s been forwarded in the original chapter by Wayment and Wilson-Lemmon, and I think there is reason to look into that, but I haven’t found anything more than they did, which is hardly anything.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you. Today, in modern biblical translations, the translator will make all kinds of word choices that are informed by mountains of biblical scholarship, but usually, they do not provide footnotes or a bibliography or otherwise explicitly cite their sources, and this is not considered plagiarism. Granted, Joseph Smith’s translation was not necessarily like that of modern translators trained in biblical languages. Might Joseph Smith’s use of Adam Clarke be similar? Clarke’s work informed some of his word choices the way scholarship often informs modern translators’ word choices.

Mark Ashurst-McGee:

I think that is a very good point. I think there’s a lot to that. It’s not an uncomplicated issue. As a counterpoint, I’ll just bring up Adam Clarke’s own commentary where he does quite a bit of work without attribution, some of which he does accomplish in a general manner in his preface. And then he also does have lots of footnotes with what even today we would consider adequate scholarly documentation. That guy is amazing, but I don’t think he’s the standard to measure Joseph Smith against. I appreciate this question because it gives me a chance to say, trying to frame this stuff as plagiarism, in addition to the fact that we don’t know how Joseph Smith would have presented it, it’s just a very ungenerous, hypercritical way of framing the whole issue that’s kind of driven by the hermeneutics of suspicion in anti-Mormon or ex-Mormon dialogue. You know, you can see where they’re coming from on that, right, and how they try to make that argument, but it’s actually, highly problematic and questionable and a very ungenerous way to approach what’s going on.

Scott Gordon:

So, let me read the next question. Haley Wilson-Lemmon and Tom Wayment acknowledge that Adam Clarke does not account for the larger portions of the JST, such as the Book of Moses. How would you categorize this large expansion of scripture: restoration of a lost text, revelation of a new text, pseudographia, or something else entirely?

Mark Ashurst-McGee:

Okay, tough question, fair question. It’s clear, from other paratexts that I didn’t have time to cover, that that material is presenting itself as revelation or revelatory translation, and that’s how I look at it myself personally, and I believe that it’s based on actual history. Not quite sure what I think about whether this stuff was written down in that way at that time. I think some of the text is kind of presenting itself that way, and others maybe not. Okay, my answer is I don’t know enough about that.

Scott Gordon:

I guess what you’re saying in all of this comment is you’re not saying the Joseph Smith Translation is a restoration of the Bible back to its original form, correct?

Mark Ashurst-McGee:

Well, not necessarily. I don’t know enough to say that. Okay, there certainly could be some of that; there are passages that seem to make the most sense in that way, but there are others that are not like that, so I think it is a combination of various things.

Scott Gordon:

Interesting, that’s really interesting. So, your final question is, good luck with this one. It says, do you have an example of a broader Christian hymn that was adapted to the restored gospel?

Mark Ashurst-McGee:

The one that pops right into my mind is an old camp meeting song, and I’m sorry I can’t remember the title, but Willian W. Phelps adapts it, just like it explains in the preface to the Church Hymnal, adapts it for Mormon usage, and he changes this kind of generic camp meeting salvation song to a song about the Lamanites. That’s a very clear and specific instance of exactly what the preface to the hymnal is talking about: borrowing material from outside, bringing it in, and adapting it to the needs of the Church. And that’s exactly how I would look at the Adam Clarke Commentary utilization: it’s consulted, selectively utilized, and adapted to make the Bible more understandable, and that Joseph Smith is not necessarily intending that readers take that as an instance of pure revelation.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you. We really appreciate your time. And thank you very much.

Endnotes & Summary

Jeffrey’s talk, What Do We Treasure?, explores how different worldviews shape our understanding of the gospel and influence what we see as the “good life.” He identifies four primary worldviews—the Expressive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, and Redemptive Gospel—each defining success and fulfillment in different ways. While Expressive Gospel prioritizes self-expression, Prosperity Gospel equates righteousness with financial success, and Therapeutic Gospel emphasizes emotional well-being, the Redemptive Gospel teaches that true success is found in reconciliation with God. By examining these perspectives, Jeffrey warns that misplaced values can lead people to misunderstand the gospel’s true purpose.

The talk highlights how Gospel Counterfeits arise when cultural influences subtly redefine gospel vocabulary and shift the focus away from Christ. He provides examples of how phrases like non-judgmental love and authenticity take on different meanings depending on the worldview, leading to confusion and potential spiritual drift. Many individuals, even those originally converted to the Redemptive Gospel, gradually adopt cultural values while still using gospel language. This process results in a faith that, while still appearing religious, may no longer align with the teachings of Jesus Christ.

Jeffrey concludes by emphasizing the need for spiritual discernment and doctrinal clarity. While Gospel Counterfeits persist because they offer comfort, validation, or worldly success, the Redemptive Gospel calls for transformation through Christ. Faithful discipleship requires prioritizing God’s values over societal expectations, measuring spiritual success by personal sanctification rather than external achievements. By recognizing and rejecting distorted versions of the gospel, believers can ensure their faith remains rooted in eternal truths rather than cultural trends.

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 9, 2024

- Duration: 26:31 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2024 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: Redemptive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, Expressive Gospel, gospel counterfeits, authenticity, covenant-keeping, LDS worldview, personal fulfillment, character transformation, reconciliation with God, faith crises, gospel vocabulary, Maslow’s hierarchy, LDS apologetics

Common Concerns Addressed

Joseph Smith plagiarized Adam Clarke.

Plagiarism involves uncredited use in published work. The JST was never published by Smith, and we don’t know how he would have credited sources.

Inspired texts shouldn’t rely on outside sources.

Biblical prophets and modern Church materials frequently incorporate outside insights. Revelation can coexist with intellectual inquiry.

Apologetic Focus

Revelation and reason are not mutually exclusive.

Plagiarism claims rest on modern assumptions and unproven hypotheticals.

Framing matters: charitable vs. suspicious hermeneutics.

Explore Further

coming soon…

Share this article