Ty Mansfield highlights the complexities of the Latter-day Saint LGBTQ+ conversation, advocating for a faith-integrated, compassionate approach that fosters belonging, challenges cultural narratives, and emphasizes marriage as a sanctifying experience.

This talk was given at the 2022 FAIR Conference on August 5, 2022.

Ty Mansfield, PhD, is a Marriage and Family Therapist, BYU Faculty member, and co-founder of Northstar, dedicated to supporting LGBTQ+ individuals in navigating faith, identity, and mindfulness.

Transcript

Ty Mansfield

Introduction:

The title of this presentation is “Loving Truth and Truly Loving: Mapping the Problems and Possibilities in the Latter-day Saint LGBTQ+ Conversation.” To give you a brief background, I spoke at the fair conference in 2014.

Reconciliation and Growth

For the last eight years, I’ve been involved in the Reconciliation and Growth Project, a group of mental health professionals from various ideologies discussing good therapy for people navigating difficult questions. Out of this, we created a guide called the Declaration on Avoiding Harm, identifying real harms in therapy. Where do we all agree the real harms are because progressive therapists can do harm, conservative therapists can do harm. And from there, a research project grew where we were looking at four different life paths for sexual minorities within the LDS Church: single celibate, single sexually active, opposite sex relationships and same-sex relationships.

If they’re going to stay in the Church they’re going to be either single or married to the opposite sex. And so what does it look like? How can they do that? Rather than saying, “Is it possible?” or assuming that marriage doesn’t work because we’ve heard the tragic stories, we can change the question to, “Why do they work when they work?” Because 80% of our sample who were in mixed orientation marriages reported being satisfied. We have to change the question so that we can help people who are navigating these questions in sensitive ways.

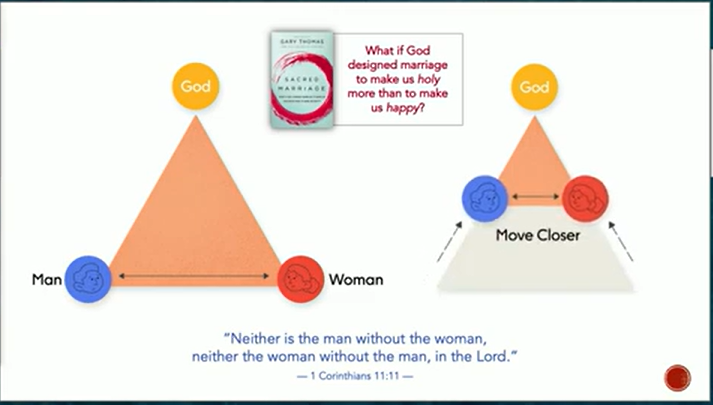

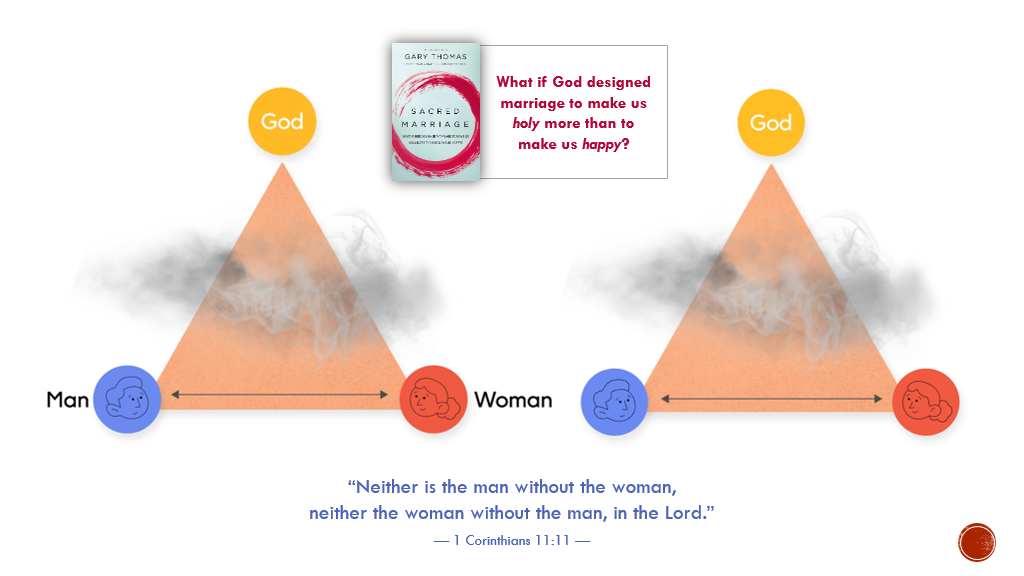

The Triangle of Covenant Marriage

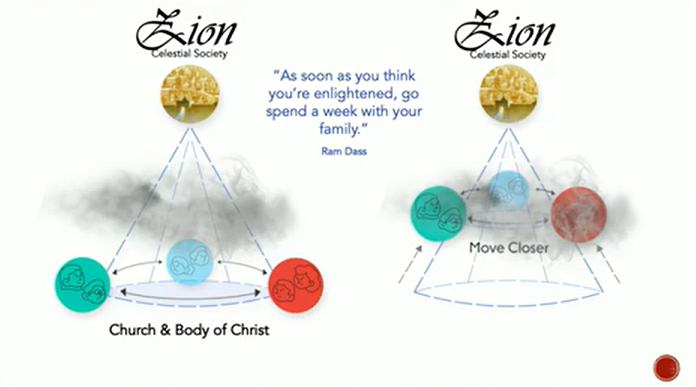

I want to start with an analogy or metaphor: the triangle of the covenant marriage. As we come into marriage, we are cleaving together in our covenant with God, involving three participants. Moving closer to God and nurturing ourselves spiritually brings us closer together. The oneness we seek can only come together in Christ.

The statement “neither is the man without the woman or the woman without the man in the Lord,” emphasizes this interconnectedness. Christian writer Gary Thomas, in his book Sacred Marriage, poses a profound question: What if God designed marriage to make us holy more than to make us happy? While happiness is essential, viewing marriage as a sanctifying experience, a crucible that pressures out our selfishness, can be transformative.

Impurities surface in marriage, acting as a crucible in a way that I believe God desires for us, a process of becoming holy. This process becomes challenging due to family of origin issues, wounds, cultural and value differences. We must press through and transcend these challenges to nurture the oneness essential for a successful marriage.

Becoming a Zion People

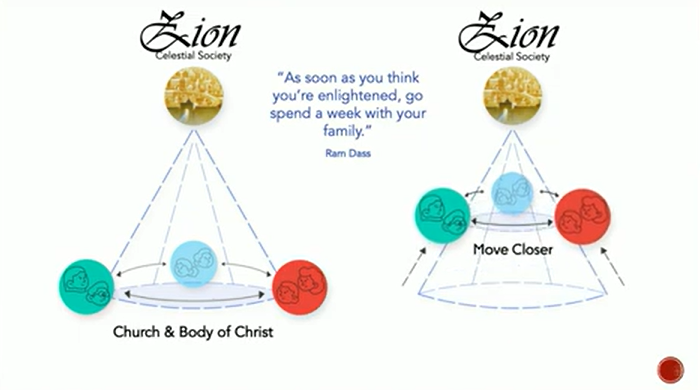

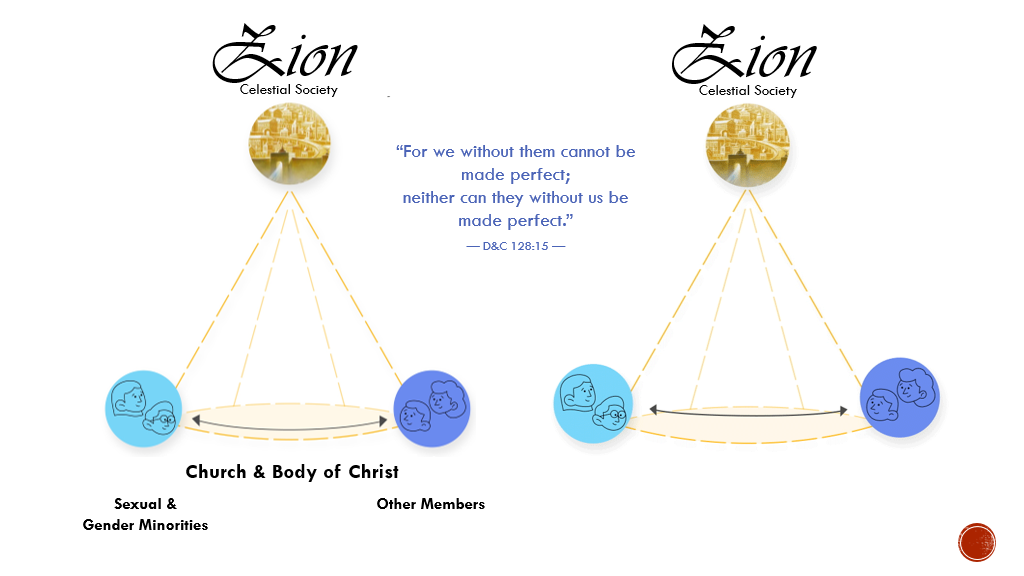

Extending this metaphor to the body of Christ, envisioning it as a cone rather than a triangle with infinite points, we unite in Covenant. Taking upon us the name of Christ involves actively participating in the eternal family today, mourning with those who mourn and comforting those in need. It transcends an ideal of eternal families to embodying the Eternal Family, singular.

As we strive to come closer to God and build Zion, we truly become one. Although Joseph’s statement in D&C 128 pertains to work for the dead, the idea that we cannot be made perfect without each other applies to our mortal interactions. In D&C 46, the Lord emphasizes that no one possesses all the gifts, reinforcing the need for each other’s diverse gifts within the body of Christ.

The Church as a Crucible

The Church serves as a sanctifying crucible, echoing Eugene England’s essay on why the Church is as true as the gospel. It is a community that goes beyond a consumer-oriented education program. Relationships within the church challenge us, providing the crucible for sanctification. As a colleague of mine said, “If you’re not offended at least once a week at Church, you’re probably not even that active.” We have to be in relationships in order for that sanctification to happen.

And as the contemplative teacher Ramdas said, “As soon as you think you’re enlightened, go spend a week with your family.” It’s easy to be enlightened on a yoga mat or on a mountaintop, but it’s really hard to be enlightened in relationships with people who trigger us or who just are different and they’re hard to understand, and we don’t feel seen and we don’t feel understood. But these are Goods that we want to seek.

But that also becomes different. People at Church have political differences and social differences and there’s just lots of different things that make becoming one in Christ a challenge. We have to press through those challenges, staying in covenant with God and each other in order to become everything that God is calling us to become.

Becoming Zion and Sexual Minorities

Now, applying these principles to the topic of addressing sexual minority issues, the focus shifts from discussing them as external problems to acknowledging the presence of sexual minorities within our congregations. Recognizing vulnerability and fostering a sense of community allows us to address real challenges faced by individuals rather than discussing them abstractly.

Sitting in an Elders Quorum class (I don’t know what Relief Society is like) when the lesson is on pornography or something, and we’re assuming that the only people who struggle are the people outside of the room, there’s just kind of a lack of vulnerability there and recognition that there are people right here who struggle, and how can we come together in community and brotherhood or sisterhood to help people through very real challenges, rather than just talking about them in the abstract as if they don’t apply? So there are sexual and gender minorities right in our congregations and potentially sitting right next to you.

One of my clients actually thought nobody would understand. As I encouraged him to create a support system, he decided to talk to his Bishop. When he opened up to his Bishop, his Bishop confided, “Yeah, that’s actually been part of my story, too.” He had no idea. The support that Bishop was able to offer, by virtue of his experience, became a crucial part of that ministry for this particular client.

I Need You and You Need Me

One of the things I forgot to mention, and I’m doing so very intentionally now, is a shift in language. We often talk about LGBTQ issues because that’s the social terminology. When it comes to understanding sexuality, however, it’s not the best term to use because it’s exclusive, focusing specifically on identity. Sexuality is complex—it’s a spectrum. There are many individuals who are navigating questions related to sexual identity who do not identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. When we talk only about LGBTQ issues, those who don’t identify often feel alienated and unseen. This becomes a challenge.

As a Church in a covenant relationship with each other, we cannot be made perfect without them, nor can they without us. I need you, and you need me, in order to be made perfect. As we listen to each other and discuss what it means to create Zion in a way that respects each of our life experiences, we’re all doing our best. But this becomes challenging when cultural dynamics make talking about sexuality in our culture very problematic.

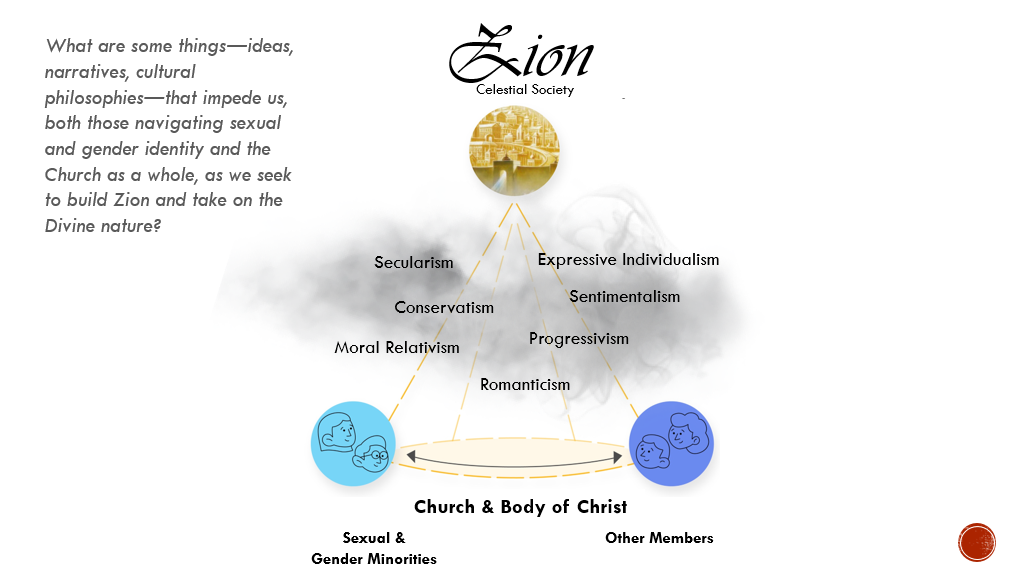

Questions to Consider

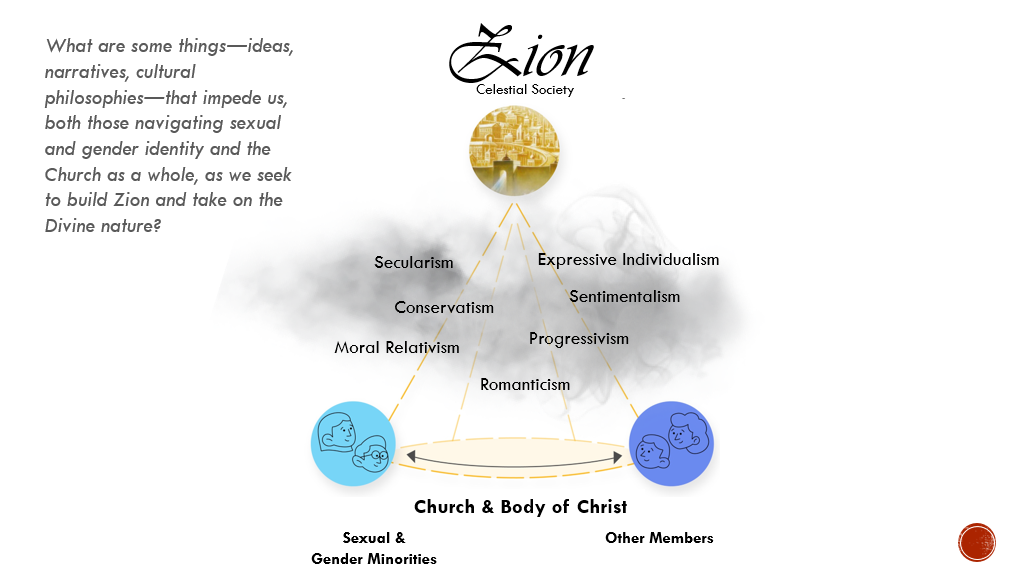

With all of this framing in mind, there’s a critical question I’d like to consider with you: What are some of the ideas, narratives, and cultural philosophies that impede us—both those navigating sexual and gender identity, and the church as a whole—as we seek to build Zion and take on the divine nature? These are kind of like the air we breathe or the water we swim in—they impact us every day. I’ll talk more about these as we go, but I want us to think about this.

Elder Maxwell once said, “If we are to see things more clearly, we must lift ourselves above the secular smog.” If you remember when the “Witnesses of Christ” videos came out, Elder Maxwell did his video from a telescope. He used that as a metaphor—there are reasons telescopes are built on mountaintops. They have to be above the smog, the pollution, and even artificial light, which can also be a form of pollution. If we are truly going to see the things of eternity clearly, we have to get above the artificial and other things that obscure or color our vision.

Moving Closer to Zion

I’m breaking up my thoughts today into three general sections: the vision, the challenges and problems, and the possibilities. What are some things we can consider as we move closer to Zion?

So, with this question—what are these ideals? I don’t know if there’s a more important question than this that we as Latter-day Saints should be asking in an ongoing way. It’s certainly not a question of whether we should be nurturing integration, support, and belonging—that should be a given. The critical question for true believers is “How?” Because a number of Latter-day Saint ministries that address LGBTQ issues seem to be high on expressive individualism, sentimentalism, and queer liberation, and low on actual grounding in the restored Gospel of Jesus Christ, offering what often feels like a Mormon-flavored iteration of what one sociologist of religion termed “moral therapeutic deism.”

In a world where conceptions of love are often rooted more in sentimentalism and moral relativism, this reminder couldn’t be more relevant. Rainbow pins and pride flags mean different things to different people, and because of this, they can send mixed messages when it comes to how we understand covenantal faith. While they can certainly send meaningful messages of love, inclusion, and acceptance to some, they are also extremely alienating to others.

Growth and Development

As such, there are a lot of declarations made about the particular unfairness around different life circumstances, but I’m not sure fairness is the right way to characterize the differences in the experiences we all have. I think that if our perspective focused less on what is fair or not, and more on what God sent us here to learn so that we can become more like Him, developing essential attributes of godliness, it would shift the attitude of many navigating these issues. We could then confidently settle into the “yes” of what we are becoming, rather than the “no” of what we perceive we are being denied here in a mortal, fallen world designed specifically for the purpose of spiritual education.

That said, while there are certainly real inequities in life that our covenants of consecration call us to minister to, I also believe that with an eternal perspective, God views our experiences far less in terms of fairness and more in terms of potential growth and development. As much as the Jews wanted a political Messiah, Jesus did not come to free the Jews from the Romans; He came to free them from themselves.

Where are we looking?

So, in our efforts to love, include, and minister to sexual and gender minorities, are we resourcing the restored doctrine and gospel of Jesus Christ, or are we resourcing queer liberation ideologies or other culturally informed resources with assumptions and values that are either wrong or antithetical to the gospel and doctrines of Jesus Christ?

What we need is a lot less shame around “same-sex attraction”; a lot less LGBTQ pride, for shame and pride are two sides of the same coin; and a lot more sexual and spiritual humility. We need a lot more trust that when God says, “For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways, and my thoughts than your thoughts,” He actually means it.

Again, in framing my exploration of these questions, I’m setting it out in the following way: what is our vision of Zion or a celestial society? This is our “yes.” I think about this all the time. Having some vision of what we’re becoming can focus us in a very powerful way, but without that vision, the opposite is true. As the proverb has said, “When there is no prophetic vision, the people live without restraint.”

A Transcendent Vision

I think it’s important to start with a larger vision and narrative as context for exploring sexual and gender minority concerns because a lot of our conversation today, even among Latter-day Saints, feels very earthy and presentist. It often feels more like we’re lost in 20th and 21st-century Western American socio-political values rooted more in progressivism or conservatism than stretching toward a transcendent vision rooted in the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

One of my favorite quotes is from President Oaks, who once said,

There is a lot of wisdom in liberalism. I see a lot of wisdom in conservatism. I see a lot of wisdom in intellectualism. But there is salvation in none of them.”

The more attached we are to our social philosophies and judge the Church by those terms, including conservatism, the more vulnerable we are to being worldly and more.

Growing Toward the Vision

With that vision in mind, we can better see how we are positioned in the process of growing toward that vision, both as a Church and as sexual and gender minorities who often feel torn living in a world between worlds. Awareness precedes power, and I believe that as we become more conscious of the cultural waters we swim in, we can better navigate those waters rather than becoming hindered or blinded by them.

Finally, I hope to explore what we can, as a faith community, do better to come more closely toward that Zion ideal and to provide a more life-giving place of belonging for sexual and gender minorities.

The Vision

So, the vision—what is Zion? Or, in a more cosmic sense, what is the nature of celestial sociality we’re preparing for and practicing to become? How do we understand the nature of love and the quality of relationships in that world?

Because of an experience I had, which I’ll share in a moment, these questions have become very relevant to me and it has come to define the way I see my life journey. I think about these things constantly.

Known Truths

Some principles: we know God is a being whose defining essence is love and who is the literal embodiment of the fullness of light and truth. Furthermore, in Joseph Smith’s vision of the Kingdoms of Glory recorded in D&C 76, he saw in the celestial glory where we receive of His fullness, we have a quality of relationship where we see as we are seen and know as we are known. That is the very essence of the definition of the word intimacy, which we gravely distort when we use that word as a euphemism for sex.

In this celestial world, we also become beings as God is, who are the literal embodiment of a fullness of love, light, and truth. We dwell in a place of perfect love and unity, with one heart and one mind and souls knit together, and who have a complete unity of heart and perfect intimacy with each other. I don’t think we can comprehend just how profound these truths really are.

My Experience

Several years ago, shortly after I had worked through an existential crisis around reconciling my own experience with sexuality in my faith, I had finally come to a place where I had decided that I was all in the Church. I had concluded that I wouldn’t marry in this life, and I had come to a place where I was at peace with that.

Even as I continued to experience some emotional ups and downs, I was earnestly seeking additional divine guidance when Fall General Conference came along that year. I wrote down some of my most heartfelt questions and went into the Saturday morning session fasting. At the beginning of the afternoon session, as soon as the opening prayer was given, I felt completely enveloped in the Spirit. I received what I think of as a vision, but it wasn’t a vision of seeing—it was a vision of feeling.

The feeling was unlike anything I had ever felt. For nearly two hours, all the hurt, pain, the confusion, the frustration were completely gone. In their place was a feeling of Divine love that I had never experienced. With that feeling came an understanding that this was pure Celestial love, and I heard the words,

Stay with me. If you do, this is the feeling you will someday feel, and it will become a permanent part of your being.”

As the end of the session approached, the feeling left. I didn’t know how I would eventually grow into that feeling, but I trusted that God would lead me. What felt most remarkable was the contrast between that experience and the way we talk about love, sex, intimacy, and romance in our culture, including LDS culture. It all feels very earthy and hollow compared to the divine love I had felt.

Another significant realization was that any thought of trying to overcome same-sex attraction or changing my sexuality felt irrelevant. My overarching desire became simply for God to teach me that kind of love, and for me to dwell in it more often.

Divine Love

This experience provided new meaning to Moroni’s teaching on charity—the pure love of Christ, which endureth forever–is bestowed upon those who are true believers in Jesus Christ and pray with all the energy of their heart that they may be filled with this love which He hath. Divine love, as I understood it, surpassed earthly or celestial projections of human romantic and sexual love. Trite sayings like “all love is love” and “you can’t choose who you love” ring shallow compared to the Divine love that God is calling us into—a spiritual gift that subsumes any love experienced outside of Him.

Not all that we call love is actually love, but true charity does love all. Said differently, I believe that the love we will all feel for and with one another in the Celestial Glory is more powerful, more transcendent, than any love we can experience in this world, including in earthly marital relationships.

Concerning the narrative that for sexual minorities the most authentic “love” is that pursued in same-sex relationships, I would suggest that there is not a single gay or lesbian couple, even the most loving or connected of all gay or lesbian couples, who love each other more than God loves us, or more than each of us all will love each other in the Celestial world.

A Call to Love More

So the call for sexual minorities is not to love less or some trite restriction that they aren’t allowed to love who they love. It’s a call to love more.

Same-sex love and intimacy is beautiful and good when we understand it in an eternal perspective. But we are called to channel and cultivate that love within the bounds the Lord has set. This kind of love actually is a choice, and more than that it is a divine gift that we can choose to accept and cultivate daily. Personally, I believe that orientation as we understand it becomes irrelevant, swallowed up in this more transcendent experience of perfect love and intimate relationship we will all experience together.

As we seek to create a Zion reflective of this heavenly manifestation, we ask ourselves how we can create spaces here and now where all people can experience deeper love, intimacy, belonging, and spiritual family. It seems that this should be one of our prime focuses in the Church. And with Church leaders recently noting that more than half of all adults in the Church are single, and with an increasing epidemic of loneliness in Western culture, it’s more important now than ever.

This is particularly true in the domain of sexuality and gender, causing heartache for sincere Latter-day Saints trying to understand these issues within the context of the Restoration in a way that feels loving, equitable, and ultimately true.

It seems to me that the number of people who have left, or considered leaving, the Church over the last five to ten years because of the Church’s position around these issues has dramatically increased.

The Prophet Joseph Smith taught that there would be generational Abrahamic tests. I have long felt that LGBTQ issues would be ours. While there is far more to say about this than I can address today, I would like to provide a high-level overview of some intersecting themes that compound the challenges we face around these issues today.

The Issues

One, there is a simplistic or problematic view of sexuality. Two, there is a simplistic or problematic view of the doctrines of the Gospel, including marriage. Three, the obscuring of both sexuality and restored doctrine by cultural philosophies, both in and out of the Church.

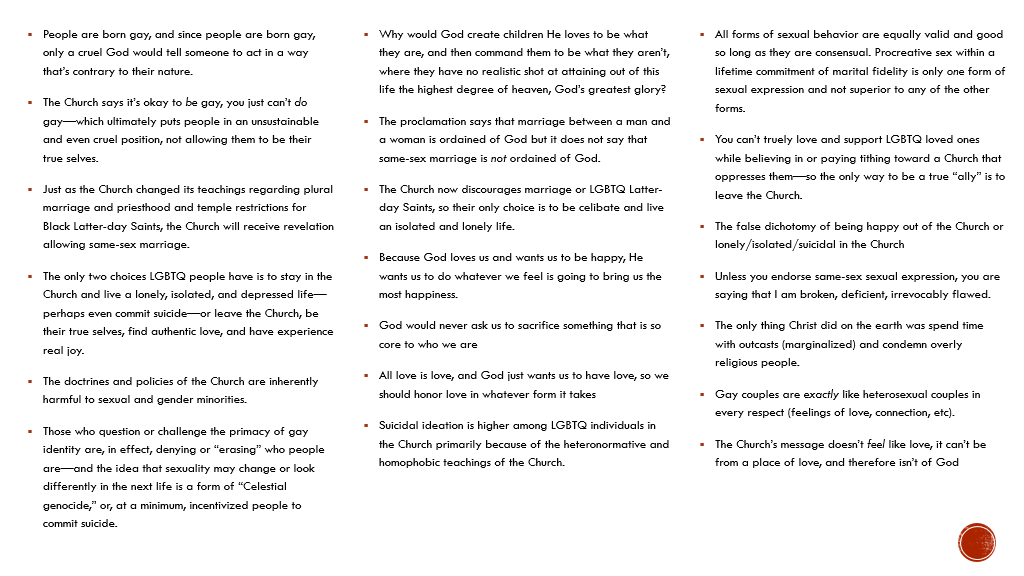

The combination of these issues has led to several statements many of you may have heard, such as:

- “People are born gay, and since they’re born gay, only a cruel God would tell someone to act in a way that is contrary to their nature.”

- “The only two choices LGBTQ people have are to stay in the Church, live a lonely, isolated, and depressed life, perhaps even commit suicide. Or leave the Church, be their true selves, find authentic love, and experience real joy.”

- “Just as the Church changed its teachings regarding plural marriage and priesthood and temple restrictions for Black Latter-day Saints, the Church will likely receive a revelation allowing same-sex marriage.”

- “The doctrines and policies of the Church are inherently harmful to sexual and gender minorities, causing suicide.”

These are just a few of the statements tied to these complex issues.

The Themes

I’m not going to spend time on all of these, but I do want to highlight some themes—some important themes—to get underneath them and shed some needed light. These are the themes that we, as a culture, are going to have to transcend and address if we’re going to nurture a community that reflects the love of God sufficiently to keep those who are struggling with what often seem to be more attractive alternatives.

Viewing Sexuality

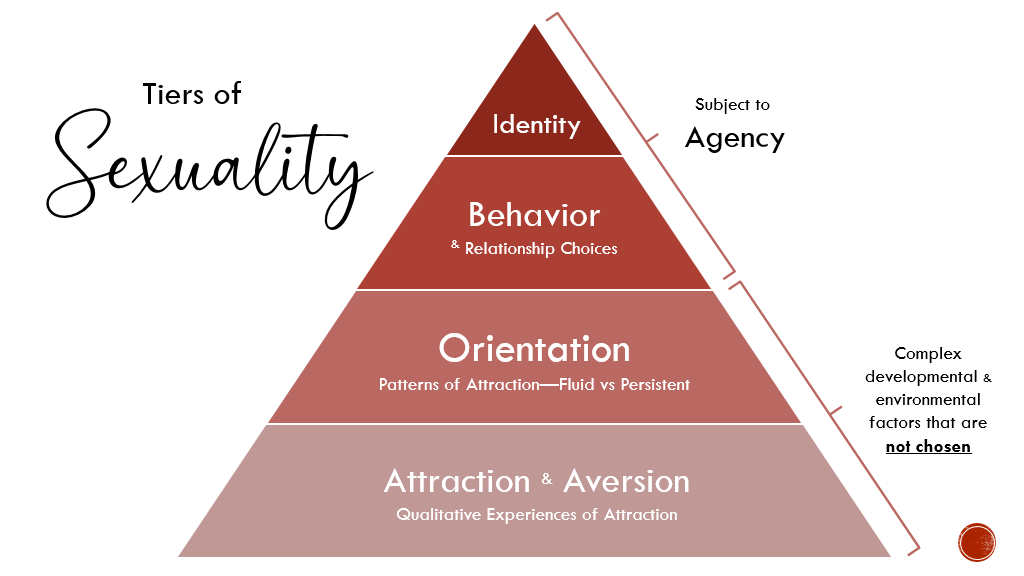

To the first point: we need a less shallow understanding of the complexities of sexuality. Having a more nuanced view of sexuality is important not just because it helps us relate to sexuality in a healthier way, but because it also shapes the story of sexuality.

We are meaning-making and storytelling creatures and communities. We can’t get away from it. Our brain is a narrative brain; it takes data and then seeks to interpret that data into a story through which we try to make sense of ourselves and the world around us.

So, while I’m going to spend more time on the narrative piece—because that’s the part that most people seem to be blinded to—I do think it’s important to lay out some key themes regarding sexuality that complicate our simplistic cultural constructs. This piece was the focus of my 2014 address, so I’m not going to spend much time here; I just want to reiterate that sexuality is layered and much more complex.

Tiers of Sexuality

I have a four-tiered framework for how we think about this. First, we have attraction and aversion—the qualitative experience of attraction. There are different domains of attraction: erotic, romantic, affectional, aesthetic, social, and even spiritual. Many of these attractions can be experienced with friends in platonic ways, but when we’re drawn to someone, there is a feeling of attraction for any number of reasons.

Certain domains are platonic, but they can overlap with erotic or romantic attractions. Then, we have orientation, which involves patterns of attraction—sometimes situational—which tend to be more persistent over time. Next, we have behavior and relationship choices. Finally, there is identity.

The bottom two are not really subject to choice; there are complex developmental and environmental factors at play. The top two, however, are very much subject to agency. We choose our behavior, but we also have a choice in how we think about and narrate our sexuality.

Labels and Identity

Sometimes we are apt to confuse labels with identity. We can get hung up on what labels or words someone is using or not using. While there can be some overlap between the two, it’s also possible for two people to use the same label or descriptive word but have very different identities. Because identity is more about the narrative or worldview that provides the interpretive lens through which individuals understand and make meaning around their sexuality, and then incorporate that meaning into a sense of self or selfhood.

This latter category is where I want to spend a little more time simply because it’s more subjective and interpretive and very much relevant to Latter-day Saint conversations around sexual and gender minority issues. Words are powerful, and the narratives they both reflect and shape cannot be underestimated.

Identity Constructs

Robert McFarland, a British writer and researcher, has written that “language does not just register experience; it produces it.” Lisa Diamond, a University of Utah researcher, noted that we must acknowledge that sexual categories or identity constructs are mental shortcuts that may be helpful in making quick judgments, but they can also be problematic as they reflect or lead to biases. She noted that when we impose these identity constructs, we’re not cutting nature at its joints; rather, we’re imposing joints on a very messy phenomenon. We have to be careful about presuming that these sexual identity categories are natural phenomena.

So, when we talk about sexuality and identity, there are all sorts of assumptions embedded that most people aren’t even conscious of—assumptions about why people experience sexual feelings they do, assumptions about what it means to have a self or a true self, and values about what kind of life is the most meaningful to live.

The True Self

Joshua Knobe, a Yale professor in cognitive science and philosophy, has explored this question of selfhood and how people conceptualize what it means to have a “true self.” In one study conducted by him and his colleagues, they asked participants to identify their socio-political leanings. Some of them identified themselves as conservative, while others as liberal, and then they provided a series of different vignettes representing conflicts between their rational reflection and deeply held values on one hand, or feelings, emotions, desires, or passions on the other.

Interestingly, what they found was that there was no consistency between liberals and conservatives regarding which parts of their experience represented the true self. On one question, liberal participants might identify beliefs and values as the true self, and on another question, they might identify feelings and emotions as the true self. The same was true of conservative participants.

What seemed most consistent in the responses was that the part that participants identified as the true self was the aspect of self that they saw as the valuable one, the good one, the part worth preserving. ”People’s ordinary understanding of the true self appears to involve a kind of value judgment–a judgment about what sorts of lives are really worth living.”

Attractions

When we talk about attractions, whether those attractions are fluid or fixed, we are simply talking about the qualitative inner experience. But when we talk about identity, we’re talking about what those attractions mean for us. We story them in ways that not only reflect current experiences but also shape future trajectories. It isn’t an objective, impartial, or value-neutral process. Identity and meaning-making never occur in a vacuum; we negotiate our identity to some degree or another with our relationships and our environment.

Whether it be through religious messages, socio-political discourse, or popular entertainment media, we consume a steady diet of external ideals and values that shape us significantly. We are often completely unconscious of its impact on us—it’s the water we swim in, the air we breathe. As a famous French lawyer once said, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are.”

Nebuchadnezzer’s Dream

However one understands sexuality, and however one chooses to self-identify here in a fallen temporal world, limited by human culture and language, I firmly believe, like Daniel’s interpretation of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream in which all social and political systems were swallowed up by the gospel stone that rolled forth to consume the nations, so will the spiritual ideals and identities of the Kingdom of God and of the celestial nature swallow up all of our social identity constructs that blur eternal identity.

The more deeply we understand and feel spiritually connected to eternal realities and our eternal identity, the less meaningful any proximate mortal identities or labels will feel to us.

Cultural Narratives

To return to our metaphorical frame of the Triune relationship, what are some of the dominant cultural assumptions and narratives, both in the Church and in the broader culture, that hinder sexual and gender minorities who are striving to stay on the covenant path and that impact the ways in which Latter-day Saints engage with them? Some examples include secularism, expressive individualism, conservatism, sentimentalism, moral relativism, progressivism, and romanticism. I believe there is something happening in the lay Latter-day Saint community that we need to be conscious of.

As an analogy for how powerful cultural forces can shape the Church, in his Truman Madsen lecture on Joseph Smith and the Recovery of the “Eternal Man”, Robert Millett, former dean of religious education at BYU, talked about the changes in the Christian concept of God that took place within the early councils, such as Nicaea and Constantinople, quoting evangelical scholars who remarked on the many insights that emerged from this inevitable encounter between the gospel and the larger culture and the influence of Hellenistic philosophy, which also helped Christians evangelize Greek culture.

Quoting these scholars, Millett continued:

Along with the good came a certain theological virus that infected the Christian doctrine of God, making it ill and creating the sorts of problems mentioned above. The virus so permeates Christian theology today that some have come to take the illness for granted, attributing it to Divine mystery, while others remain unaware of the infection altogether.”

I believe that something comparable is happening in the Church today, the lay community, regarding ideologies surrounding love, marriage, sexuality, and gender. Cultural movements such as secular humanism, expressive individualism, Romanticism, and sentimentalism, which have given rise to sexual liberation and subsequent gay and queer liberation movements, have influenced even members of the Church in ways that most simply don’t comprehend. Just as Greek and Pagan cultures of old, they have, in many ways, infected the worldviews of many Latter-day Saints and become a kind of theological virus or spiritual cancer.

A Backdrop for Doctrine

Elder Bednar once said:

Never has a global society placed so much emphasis on the fulfillment of romantic and sexual desires as the highest form of personal autonomy, freedom, and self-actualization. Society has elevated sexual fulfillment to an end in itself rather than as a means to a higher end. In this confusion, millions have lost the truth that God intended sexual desire to be a means to the Divine ends of marital unity, the procreation of children, and strong families.”

These cultural narratives shape, in very significant ways, the backdrop for how we think of the doctrine of marriage in the Church, particularly with a growing belief among a subset of members that the Church is likely to change its doctrine to accommodate same-sex marital sealings. Some Latter-day Saints have gone to great lengths to show how that could be a theological possibility.

Two of the most common analogs for that anticipated change are: one, changes in the Church’s teachings relative to priesthood and temple restrictions for Black Latter-day Saints, and two, changes in the practice of plural marriage. While changes relative to Blacks and temple or priesthood restrictions have tended to be the more popular analog, I actually believe it’s the weakest.

Evolution of Marriage

All analogies have their limits, but I believe that changes relative to teachings around plural marriage, and more specifically, the nature of Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo teachings on marriage and the evolving cultural backdrop for those teachings, might actually be the best analog to understanding the current cultural moment we are in relative to LGBTQ issues, though probably not for the reasons many would think.

Latter-day Saint doctrine has a high—and I would even suggest unsentimental—view of marriage. What we have called Eternal Marriage is, in actuality, an order of the Priesthood (D&C 131:2). A panoptic covenant built on preceding covenants of death and rebirth in Christ, priesthood, sacrifice, consecration, obedience, chastity, and with Abrahamic promises and stewardships regarding eternal lives and a continuation of the seeds forever and ever. I actually believe that we can’t truly comprehend the doctrine of marriage if we do not comprehend the doctrine of consecration.

A Modern View of Marriage

Even so, a growing number of Latter-day Saints have imported or grafted in a more Disney-fied view of marriage—what I like to call “Disney Forever.” They may still believe in marriage as a covenant that is bound to last eternity but with primarily a companionate view of marriage that is based almost exclusively on committed partnership, emotional bonding, mutual egalitarian consent, authentic self-expression, and personal fulfillment.

They read God’s declaration in Genesis that “it is not good that the man should be alone” as if His only concern for Adam was that he not feel lonely. Except for the need to produce biological children, sexual and gender complementarity are unnecessary, and gender itself becomes near irrelevant. If these are the preeminent values and narratives of marriage, then does sexual or gender complementarity really matter? Is a heterosexual attachment bond really that much more valuable than a same-sex attachment bond?

What can sustain a marriage?

Beyond the religious ritual and stated ideal of Eternal Marriage, one consideration that has felt increasingly significant to me over the last several years is: what is a narrative of marriage that can actually sustain a marriage for eternity? Because many of the companionate, romantic, or fulfillment narratives of relationships in our culture—including greater normalization of cohabitation, serial monogamy, consensual non-monogamy, and polyamory—have made relationships increasingly unstable and unsustainable, even for a significant period of mortality, to say nothing of eternity.

Signing our name on a piece of paper and kneeling across an altar for 15 minutes does not magically endow it with the constantly renewed, ever-expanding creative vitality necessary to make an eternal union truly sustainable through the eternities. Some of you may have known somebody who’s been married in the temple and divorced, right? There are reasons that marriages end, so there has to be something deeper within marriage that can actually sustain it. The idea of what we believe about marriage is important.

While there are some cultural values around relationships that the Church will never endorse, there are certain narratives—like the romantic and companionate focus—that we’ve made strong cultural concessions to because until recently, they seemed compatible with, or at least not in opposition to, Joseph Smith’s restored view of Eternal Marriage. While both of these attributes can certainly be valuable components in the quality of marriage, they have been a double-edged sword.

Love-Based Marriage

Stephanie Koontz, a prominent historian of marriage, has noted what she calls the “Paradox of Marriage,” that the love-based marriage, as it was known in the 18th and 19th centuries, became a destabilizing force in the institution of marriage.

Koontz notes that

Marrying for political and economic advantage remained the norm until the 18th century. Lifetime marriage was the norm, and divorce rates were low. Marriage as an institution was quite stable. But, at the end of the 18th century, shortly before the dawn of the Restoration, it started to become more common and accepted for men and women to be able to choose or refuse a marriage partner. For the first time in 5,000 years, marriage came to be seen as a private institution between two individuals rather than a link in a larger system of political and economic alliances.”

Koontz also noted, ironically, that every place the development of love as the basis for marriage has come with attendant ideals of free choice, individual negotiation, and voluntary compliance to the standards of marriage—all ideals that Latter-day Saints would rightly subscribe to, I would add—the demands for divorce have also risen. The rates of divorce have risen significantly.

Good Marriage

When marriage is good, people report, on average, far higher levels of satisfaction than they’ve ever reported in history. We demand more of a successful marriage today than we’ve ever demanded in history. “When a marital relationship works today,” Koontz notes, “it is fairer, more intimate, more mutually beneficial, and less prone to violence than ever before, and individuals are less willing to stay in a relationship that doesn’t confer these benefits.”

When it comes to Latter-day Saint ideals of marriage, we certainly want to understand the component parts of satisfaction, the substance of marriage, but we also need a narrative of marriage that nurtures the setting of an eternally enduring foundation.

Marriage in Nauvoo

But even more relevant to our discussion today are these cultural evolutions regarding the romanticization of marriage and the tensions they invoke, with the revealed and doctrinal development of marriage in Nauvoo, ultimately providing perhaps the best analog to our conversation around sexual minorities in the Church today.

In Nauvoo, Joseph began to teach the eternal sealing of men and women as a third order of the priesthood, requisite to obtaining the highest heaven or degree of celestial glory. At which time, he also privately introduced the practice of plural marriage. These theological developments increasingly placed Mormonism at odds with the dominant culture of Victorian Romanticism.

Communal Covenants

Kathleen Flake, the chair of Mormon studies at the University of Virginia, has written that the spirit of the marital covenant Joseph Smith taught in Nauvoo was a love subordinated to religious devotion and ordered by religious, not romantic, ideals. Joseph’s marital covenant “secured men and women in a required reciprocity of a gendered priestly order created by their temple rituals and in an intimate network of highly ritualized covenant attachments.”

Whatever role marital sealings would play in the eternities, it seemed that in Joseph’s cosmology, marriage would be an extension or perhaps the culmination of his vision of collective, communal covenant relationships revealed early in his restoration efforts.

The Sealing Covenant

While the American cultural concept of marriage provides a kind of analogy, Joseph Smith was also revealing or restoring something much more expansive and transcendent. Joseph’s sealing covenant, while often termed marriage, was actually an initiation or an ordination into an order of priesthood, bestowing a kind of priestly authority on men and women to do priestly work: to establish Zion on the earth and to further the work of salvation by assisting eternal intelligences to further their progression by raising and nurturing them within that covenantal bond.

Joseph’s system of marriage would provide a sharp challenge to prevailing cultural notions of increasingly individualistic and romantic marital ideals, and it would be challenged by them. While these ideals continued to grow in popularity in Western culture, Joseph’s revelation moved marriage in the reverse, tying marriage back to a larger system of relationships and priesthood social orders.

Plural Marriage

Plural marriage, as an element in this restored vision, was the part that scandalized Victorians the most, but his restored view of marriage as a priestly institution was the even more radical departure from it. This growing tension between cultural ideals of romantic marriage and the priestly doctrine of marriage would increasingly challenge the Saints as well.

Flake observes, “These mutually interdependent priestly identities conferred through temple marriage stood in opposition to the romantic oneness that defined men’s and women’s relationships in Victorian marriage.” She also notes that, as plural marriage was more openly practiced in Utah, those who were more likely to struggle in a plural marriage were those who were more emotionally attached to the Victorian ideals of romantic love and expression, while those who were more likely to thrive in a plural marriage had come to embrace or at least accept this more priestly view of marriage that Joseph had taught.

”In the order of the priesthood that was Latter-day Saint marriage,” Flake continues, “The power to birth was related to the power to redeem or save souls, not merely to a numerical increase.” Joseph Smith bestowed upon their participants powers that made childbirth and child-rearing priestly acts that required the exercise of salvific powers.

Priestly Acts

There were examples of this connection in 19th-century rites officiated respectively by women and men: the women washing, anointing, and sealing blessings on their sisters for birth; the men rebirthing children through rituals of baptism, confirmation, and ordination. Speaking more cosmically, one group was engaged in priestly acts of literally birthing or endowing a spirit with a body to make a living soul, while the other group was engaged in priestly acts of administering ordinances preparatory to the ultimate rebirth of resurrection.

While this priestly view of marriage seemed to be more pronounced in the 19th century, and while it seems that plural marriage required a more priestly view if one was going to thrive, Flake’s articulation of the priestly narrative of marriage is perhaps still the best description, even in the context of monogamy, of what it means for us today for marriage to be an order of priesthood.

Changes in Rhetoric

At the turn of the century, as the Church was seeking to integrate back into the mainstream of the United States, the Church discontinued the practice of plural marriage. The Church continued to practice the theology of eternal sealing and developed a theological rhetoric of eternal families, but there also seemed to be a lessening of some of the priestly rhetoric relative to marriage and childbearing.

There has also been a simultaneous increase in the romanticizing of theological structures of Latter-day Saint marriage, as seen in cultural productions like “Saturday’s Warrior.” The lessening of the priestly rhetoric and the adoption of a more inward-focused romantic rhetoric of marriage in the Church has, I believe, been a huge contributor to some of the confusion that Latter-day Saints may feel as they wrestle with LGBT issues and wonder why the love and companionship of same-sex couples can’t be provided the same value as the love and companionship of opposite-sex couples. And they have a point.

Understanding the Doctrine

If marriage is merely a vehicle for companionship, pleasure, and personal satisfaction, there isn’t any non-theological reason why this should exclude same-sex parents or any other variety of couplings or polyamorous unions that we might envision. As Church leaders remind the Saints that the doctrine of marriage and chastity will not change, it’s easier to understand those teachings in the context of this procreative, covenantal, and cosmic view of marriage.

The priestly narrative that underlies our doctrine of marriage is once again, though for very different reasons, at the heart of the cultural tensions within the Latter-Day Saint community and it stands in opposition to the competing narratives of marriage that are rooted almost exclusively in the values of companionship, emotional bonding, egalitarian consent, and authentic self-expression and personal fulfillment.

What should we do?

Okay, I’m going to summarize. I’m going to have to pick through this last section. So, what do we do with all of this? Beyond simply being conscious so that we can, with an eternal perspective, stay rooted deeply in the gospel, we keep building Zion. For gender and sexual minority Latter-Day Saints who believe in the restored gospel and desire to stay on the covenant path, how do they do so in a way that fosters true flourishing? And how can the rest of the body of Christ best support them?

While there are a number of needs we all have, I believe that our core needs, the needs that are truly requisite for flourishing, can be roughly categorized into two genres of needs: having a sense of meaning and positive identity; and experiencing connection, intimacy, mutual understanding, and belonging.

A Vocation of Yes

Because very often the teachings are framed as what you can’t do—right? The feelings aren’t a sin; just don’t act on them. People often feel a kind of limiting view of where their place in the Church is. But as Wesley Hill, a gay Christian writer, articulated it, we need a “vocation of yes.”

Vocation is not a word traditionally used by Latter-Day Saints, but I like it. In Catholicism and among other traditional Christians, it’s the feeling of mission for how God calls you to serve Him in the world. Eve Tushnet, a gay Catholic writer, phrased it, “You can’t have a vocation of not gay marrying or not having sex. You can’t have a vocation of no.”

To find our “yes,” we need to feel that the key experiences we have in mortality are here by purpose and design. We each have a customized curriculum. Several years ago, the Spirit taught me that I knew in the premortal world that same-sex attraction would be a part of my mortal experience and that it would be tied to my mortal mission. That knowledge has completely reshaped my relationship with my experience. The questions I had for the Lord shifted more to what He wanted me to do with it—how I could consecrate it to the building up of the Kingdom—rather than feeling a sense of loss that my life looked so different from those closest to me. This was in the years that I believed I would never marry.

Building the Kingdom

We all have unique gifts, as Elder Christofferson has told us, that we can contribute to the Kingdom.

Everyone has gifts. Everyone has talents. Everyone can contribute to the unfolding of the divine plan in each generation. Much that is good, much that is essential, even sometimes all that is necessary for now, can be achieved in less ideal circumstances. So many of you are doing your very best, and when you who bear the heaviest burdens of mortality stand up in defense of God’s plan to exalt His children, we are all ready to march.”

Having our “yes” and finding ways to contribute it positively to the Kingdom may not always make our lives less challenging or without sacrifice, but meaning always sanctifies that sacrifice.

And then finally, I believe that all of these things are critical considerations for the Church, particularly given our high view and vision of the kind of community we’re all striving to live toward as an eternal family. How can we move closer to that Zion space of connection, belonging, and intimacy, where we all feel more valued, known, and loved? For that is our spiritual birthright.

Thank you.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you very much for your words. I have several questions from the audience, and we’ll try to distill them, as there are a lot of duplicates. Your diagram of the cone that illustrates a society coming closer together as they come closer to God is fascinating. But what if some of us in society are not striving to become closer to God? Wouldn’t that make the distance between those who are coming closer to God and those who are not greater? What do we do about that?

Ty Mansfield:

Yes, so obviously, we’re beginning with the assumption that those with whom we’re in a relationship are also striving. If we’re coming closer together. I think, per the previous discussion, as we stay deeply rooted in the gospel, we can still minister in very powerful ways to other people and help them to grow. Just as Joseph Smith said, if I can’t convince somebody that my way is right, I’ll try to lift them up the best way that I can in their way, right?

Scott Gordon:

Okay, and another one says, “I’ve heard lots of people say that love is advocacy. How can I best show my LGBTQ friends and family that I love them while they also know that I do not necessarily agree with their life choices and that I would not take upon myself Pride symbols?”

Ty Mansfield:

The key piece there is developing a capacity to simply be with them, right? I think more often than not, people know what our values are; they know what our stance is. What they don’t know is if we can handle them, right? If we can be present with them, if we can love them where they are. So the piece of staying anchored is our personal piece. I think sometimes the Spirit calls us to open our mouths, and many times the Spirit calls us to just keep them shut and to just love people where they are. Let that love be a manifestation and a witness of the kind of love that God has for them. If we can make that real in people’s lives, I think they will be drawn to that because it’s real, it’s substantive. And over time, perhaps, maybe that can be a draw ultimately for them to greater light themselves.

Scott Gordon:

Yes, a number of them are along the same theme. One person writes about how they work together with LGBTQ and went to their weddings, their divorces, their get-togethers, but then he says, “After numerous online videos surfacing recently that feature teachers and others with influence over kids, I’m starting to feel betrayed and more defensive of my children. What can I do to still be accepting and tolerant to my brothers and sisters while trying to protect my kids?”

Ty Mansfield:

Now that’s a hard one, and I think that’s becoming increasingly challenging with social and cultural issues evolving, particularly in education. But I think it comes down ultimately still to the same principle: we stay deeply rooted ourselves, and loving people doesn’t mean we don’t have boundaries, right? Love requires boundaries; sentimentalism doesn’t, but love does.

So, for us to say, “These are the things that are okay or not okay for me or my family, or that I’m not going to allow in my home,” doesn’t mean that we still can’t be fully present with people in their journeys, just by virtue of learning how to be with them without worrying about whether me being in someone’s life is somehow endorsing something I don’t agree with. I think sometimes we can get a little too lost in that latter piece. We just show up and be with them, right? Jesus, you know, as he was ministering, I think what led people to feel most of his love wasn’t that he, you know, was condemning or even affirming. He just was with them. He just sat with them, and I think that’s what we can learn to do more ourselves.

Scott Gordon:

There is one here: “Do you foresee the Savior, through His Atonement and Resurrection, as being able to heal all the various intergender attractions that do not fit into celestial marriage in the resurrection, or perhaps even sooner in the spirit world, so that all of God’s children have an opportunity for the maximum eternal blessings? Do you foresee those perfect bodies including opposite-gender attractions?”

Ty Mansfield:

I don’t think we know. I mean, we don’t have a theology of what procreation or sexuality even looks like. We don’t know if resurrected bodies have testosterone. What we do know is we have a sense of this order. I really, just truly, believe that the quality of the experience we’re having—certainly a lot of what we feel—is rooted in the body, right? It’s just part of the mortal experience as we are inhabiting these bodies that develop within a social and environmental context, and develop differently for any number of reasons. But it’s all still part of our environment, right? Our spirits are inhabiting these bodies for a reason, right? For educative purposes, and as whatever is spiritual, you know, whatever is physical is going to be left behind. I think a lot of what we experience will be very different from what we think it will be, based on this mortal body as our only experiential reference point.

Scott Gordon:

So let me give you one final question. Let’s say we’re going along and our son or daughter or grandchild suddenly announces that they’re gay, or lesbian, or trans, or something. What action would recommend as our first step?

Ty Mansfield:

Ask lots of questions and listen before offering advice, right? Ask, “Tell me what that’s like for you,” right? “What has that been like?” Like, if they told you later, “What left you feeling that you couldn’t tell me before? Because if there’s something about our relationship that makes you feel like you don’t feel safe to be vulnerable, what can I do better as a parent to create more safety for you?” And just let that be a conversation without any judgments.

There needs to be, again, awareness before power. We need to understand first; we can work through all the other things later. But the first key piece is just listening and being with them.

coming soon…

- Date Presented: August 9, 2024

- Duration: 69 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2022 FAIR Conference, Experience Event Center, Provo, Utah

- Topics Covered: LGBTQ, Sexual minorities, Gay marriage, Same-sex relationships, Mixed orientation marriages, Mormon beliefs, Eternal marriage, Covenant marriage, Zion community, Cultural narratives, Secularism, Sentimentalism, Expressive individualism, Romanticism, Church teachings, Divine love, Identity constructs, Attraction spectrum, Priesthood order, Plural marriage, Doctrine of consecration, Emotional bonding, Procreation, Joseph Smith’s teachings, Nauvoo marriage practices, Gospel of Jesus Christ, Eternal families, Faith, Consecration, Personal sacrifice, Ministry, Community belonging, Church culture, Support systems, Inclusivity.

Why does the Church’s stance on same-sex relationships seem restrictive?

Ty Mansfield emphasizes that covenantal love calls for transcending earthly definitions, offering a vision of divine relationships in the celestial world.

How can latter-day Saints support LGBTQ individuals while staying true to gospel principles?

He advocates for compassionate engagement that fosters belonging while maintaining boundaries rooted in love and gospel teachings.

Exploring eternal perspectives on sexuality and marriage.

Challenging cultural narratives with restored doctrine.

Promoting Zion-like communities where diversity enriches collective growth.

LGBTQ+ and the church.

General questions about identity – FAIR

Same-Sex Attraction – the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Share this article