Summary

Egyptologist Kerry Muhlestein offers a detailed examination of the Egyptian Papers and their relationship to the Book of Abraham. Through logic, historical accounts, and document analysis, he challenges the common assumption that the Egyptian grammar and alphabet documents (GAEL) were used as tools in the translation. He argues instead that the translation was achieved through divine inspiration, and urges a shift in scholarly focus toward more fruitful lines of inquiry.

This talk was given at the 2020 FAIR Annual Conference on August 6, 2020.

Kerry Muhlestein is a professor of Ancient Scripture at BYU and a trained Egyptologist, known for his research on the Book of Abraham and his faith-based approach to Latter-day Saint scholarship.

Transcript

Introducing Kerry Muhlestein

Scott: Our next speaker is Kerry Muhlestein. He received his BS from BYU in Psychology with a Hebrew minor. Kerry received an M.A. in Ancient Near Eastern Studies from BYU and his PhD from UCLA in Egyptology. He’s taught many courses and he has a long bio in your program. But with that short intro, we’re going to turn the time over to Kerry.

D. Kerry Muhlestein

What the Egyptian Papers Can and Cannot Tell Us About the Translation of the Book of Mormon

Presentation

Kerry: Good morning. It’s wonderful to be with everyone in whatever way we are being together. Kind of different circumstances, but I’m glad that I’m here. I’m really impressed with how FAIR has thought this through and put it together so that we can still learn from each other and be edified. I think it’s just a great opportunity.

So, I’m also excited for the chance to talk to you today about what is an important subject, I believe. Some of it will be somewhat technical, but I hope we can kind of get through it in a way that makes sense to everybody. But let’s just jump right in and see what we can do.

Method of Translation

One of the questions that has been a bit of a buzz lately is, what is the method of translating the Book of Abraham? And there are a number of questions that come up in regard to this. But today, we will, in particular, address the question as to whether the Egyptian alphabets, and the grammar and alphabet of the Egyptian language that were created somewhat by Joseph Smith, largely by his associates, and we’ll talk about that as we go along, we’ll address whether that was the tool used for translation. But before we address that, I’ll address first, limitations and then some assumptions that are really, really key.

Limitations

First of all, the limitation is that, while we could get into a thousand things about what we could call the Egyptian papers–which are the translation manuscripts that are now extant of the Book of Abraham, the earliest ones we now have, which don’t seem to be the earliest ones, the various copies of Egyptian characters, and the three documents known as the Egyptian alphabet, and a larger one called the grammar and alphabet of the Egyptian language–there are a thousand things we could do with those. We are only going to be addressing this one question today, which is, what is the relationship between the Egyptian alphabets and the grammar and alphabet, and the translation of the Book of Abraham? And in some parts, we’ll only address very specific parts of that.

Assumptions

But even before we do that, I think it’s important to address some basic assumptions.

And one of those assumptions, and I’ve spoken about this actually before, but I think it bears keeping in mind again, one of those assumptions is that everybody comes in with an initial assumption. People either, and it’s a religious choice whether someone is secular or not, if they’re secular, they have made a religious choice, and the religious choice is, do you believe that Joseph Smith could possibly translate Egyptian?

We know we couldn’t translate Egyptian via ordinary means, the way that we would today using the grammars that we’ve developed and so on. That was not within his capacity. And so, if he was going to translate, it would be through inspiration. So, you have to make a choice: could he possibly translate through inspiration or not?

If you have made the religious choice to believe that he could not, that will color your assumptions. If you’ve made the religious choice to believe that he could, that will also color your assumptions. And that’s something we have to think through.

But too often, those who have chosen to believe he could not, act as if that then is the more objective position. And we need to be clear, that is not a more objective position. In fact, I would argue that if you are aware of your assumption and the way that it colors the way you look at things and interpret evidence, that you are closer to being objective than someone who thinks they’re being objective but actually, in fact, they’re coloring things by their assumptions.

Guiding Principle for Joseph Smith

And I would argue that that is actually good scholarship. It is proper and good scholarship to be aware of the assumptions that are made and how they affect you. And it’s poor scholarship, and I believe intellectually dishonest, if you pretend that you’re objective when you’re not or if you pretend that you don’t have any assumptions; that will inevitably affect you more than if you are aware of and trying to deal with those initial assumptions.

Let’s just use one example of this assumption. Another assumption I should say, you can ask yourself is revelation a guiding principle for Joseph Smith or is it not? That’s, even for a believing scholar, you will have to operate under that assumption. What was the guiding principle for Joseph Smith? Let me give you an example. This won’t be the focus of today’s talk, but I think it’s a good example of the kind of the way that our assumptions color our scholarship.

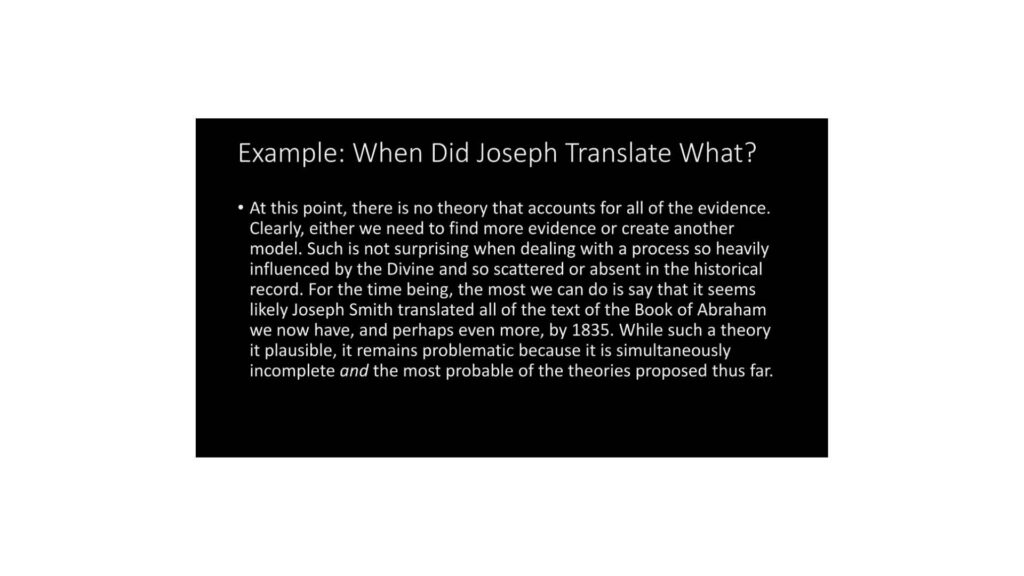

So one of the questions that people have asked frequently is, when did Joseph Smith translate what of the Book of Abraham? And while there are two main camps, there are all sorts of nuanced positions on a continuum between, but there are two main camps. One of those would be that he translated everything we currently have, and perhaps or maybe even probably even more, by the end of 1835. And the other would be that he translated up through Chapter 2, verse 18 by the end of 1835, and the rest of the Book of Abraham, he translated into a few weeks in 1842.

Probable Theory

And people get quite worked up about this. I’m not sure, well, for a long time I wasn’t sure exactly why. In a minute, I’m going to tell you what I think the reason is. But people get worked up about this, and I have done a fairly lengthy investigation of this. I’ve been interested to see that people say, “I am absolutely sure that it was all translated in 1835,” and I’ve had people say, “I was absolutely sure it was all translated in 1842,” or that much of it was translated in 1842. So, let me read to you what I’ve actually said about this, and then we’ll see if we can understand why people care about this.

This is something I published. It says,

At this point, there is no theory that accounts for all the evidence. Clearly, either we need to find more evidence or create another model. Such is not surprising when dealing with a process so heavily influenced by the divine and so scattered or absent in the historical record.

For the time being, the most we can do is say that it seems likely Joseph Smith translated all of the texts of the Book of Abraham we now have, and perhaps even more, by 1835. While such a theory is plausible, it remains problematic because it is simultaneously incomplete and the most probable of the theories proposed thus far.”

Examples of Evidence

So, at least I think I’m saying there that we’re not sure, but one seems more likely than the other, but really we can’t tell, we’re not sure. I think actually we can tell a little bit more now, we’ll get into that later. But still, I’ve been perplexed why people were so adamant about this, and wondered why do people care so much. And finally, it occurred to me that it’s because of some assumptions about how Joseph Smith interacts with revelation.

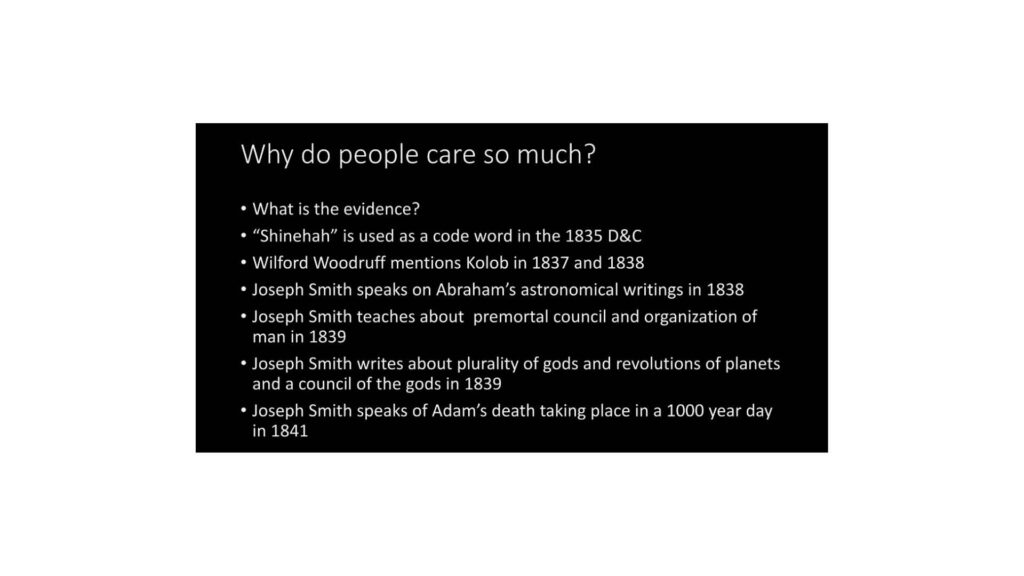

And I think we can see this best if we look at what is the evidence, or some of the evidence. There’s a lot of different evidence, let’s just look at one kind of evidence that suggests that he had translated what we have now, and perhaps even more, by the end of 1835.

So, I’ll just give you a smattering of examples, there are more than this.

- For example, the word “Shinehah” is used as a code word in the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants. That word is also used in the Book of Abraham. And so, it would seem that that comes from the Book of Abraham text.

- Wilford Woodruff mentions Kolob in 1837 and 1838, which comes from the Book of Abraham. That’s where we get that.

- Joseph Smith speaks on Abraham’s astronomical writings in 1838. So, all of this is before 1842, right?

- Joseph Smith teaches about pre-mortal council and the organization of man in 1839, which is something that’s in the Book of Abraham text.

- Joseph Smith writes about the plurality of gods and revolutions of planets and a council of the gods in 1839, all of which is in the Book of Abraham text.

Assumptions of the Book of Abraham

He speaks of Adam’s death taking place in a 1,000-year day in 1841. Now, you actually can get that from the Joseph Smith translation, but also in the Book of Abraham text.

And I was perplexed after going through this evidence that some people did not see this as any kind of evidence that he had translated anything in the Book of Abraham that had to do with this before 1835, until I realized from a podcast I listened to that their assumption actually was that Joseph Smith had these ideas and they were kicking around in his head and then he created the Book of Abraham to codify and justify those ideas. And these are believing scholars.

That is an assumption, right? I was operating under an assumption that Joseph Smith received things from revelation, such as translating the Book of Abraham, and then the things he’d received in revelation would work his way into his thoughts and thus into his speeches and his writings. Whereas others were operating on the opposite assumption that he had things in his thoughts and that then created revelation or translation of scripture. I reject that hypothesis myself, but that is the kind of assumption that colors what we think and how we interpret evidence.

So, with all of that in mind, let’s look at an untested assumption that has to do with the translation of the Book of Abraham. And we can phrase this as if we are playing clue, we can ask: was the translation done by Joseph Smith in the Whitney store using the grammar and alphabet of the Egyptian language? That’s the question that we’re addressing today.

Revelations Volume 4

And again, if we’re going to talk about untested assumptions, the recent Joseph Smith Papers Project, Revelations volume 4, which is a very, very valuable tool, and in a moment I’ll show you just how valuable it can be. But it also has some assumptions in it.

It doesn’t state it explicitly, but in talking with its editors, I understand that they had assumptions that actually it was–and it’s present if you look for it, you’ll find that in the footnotes and in the apparatus, though it’s never stated explicitly–there is an underlying assumption that the grammar and alphabet and the Egyptian alphabet—I’m just going to, from now on, call those the grammar and alphabet, knowing that there are a couple of different documents but it gets too long to say both every time—that the grammar and alphabet were the tool that was used for translation.

That’s an assumption that was made and is made by a number of people and that undergirds much of Revelations Volume 4.

Creating a Hypothesis

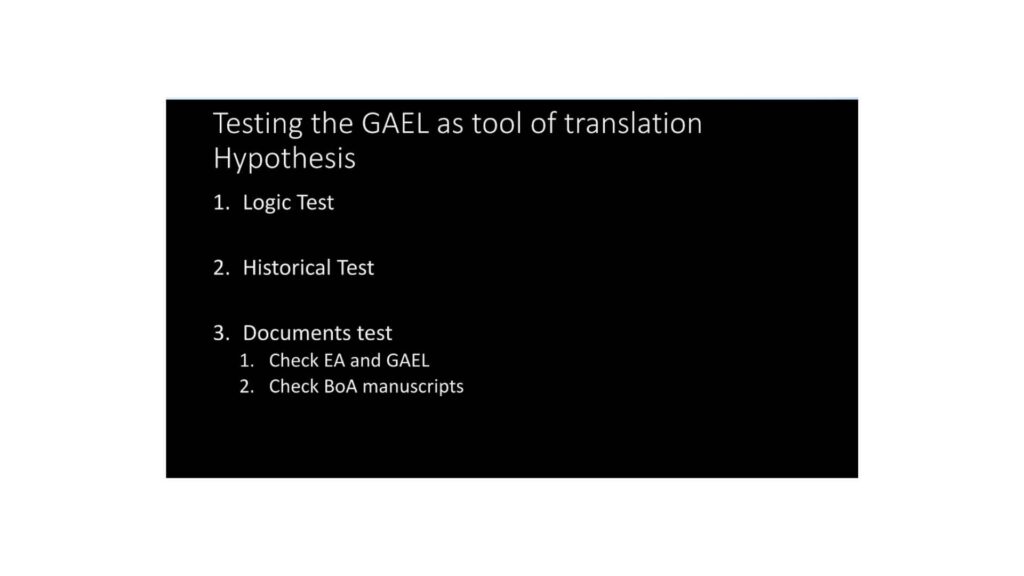

So, let’s turn this assumption into a hypothesis. If we’re going to turn it into a hypothesis, that means we have to test it. We recognize it, we state it, and we test it. That’s what will make it a hypothesis. So, we’re going to use this, the grammar and alphabet of the Egyptian language or GAEL as a Tool of Translation Hypothesis. We’ll test this. There are a couple of ways we can test this.

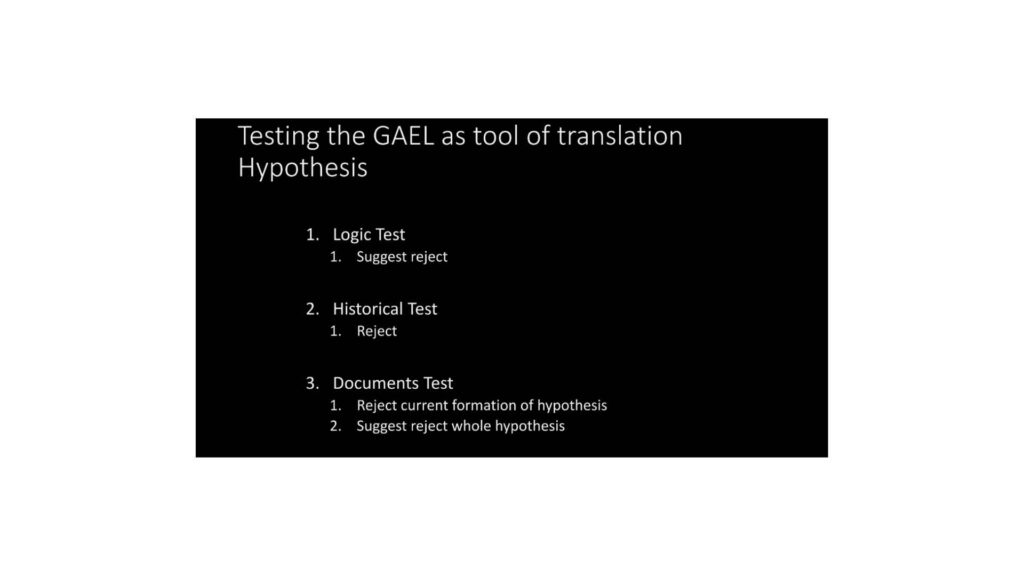

One is a logic test. We’ll address each of these in turn. Another is to look at the historical test. What do the historical records tell us? And then we can do a documents test. What do the actual documents—the grammar and alphabet, the Egyptian language, the Book of Abraham manuscripts—what do they tell us?

And there are a couple of subsets that we’ll check—the Egyptian alphabet and the GAEL, and we’ll look at the Book of Abraham manuscripts that we now have, the earliest ones we now have, which as I said earlier, are probably not the earliest ones.

Logic Test

Let’s just look at the logic test, and this one won’t take us long. But just ask yourself, is it reasonable to have a text in characters you don’t understand, in a language you don’t understand, and just look at it and create a grammar, and then use that grammar to translate the document in front of you? And we can even ask ourselves, can it be done this way, and has anyone ever tried to do it this way?

And the answer for both is no. It makes no sense. Even W. W. Phelps, who was very, very much involved in this, and in fact, is almost certainly the driving force behind most of these documents, and W.W. Phelps was a little bit crazy about his language ideas. He really, he had some gifts and he had some crazy ideas. Before working with Joseph Smith on the papyri, he was working on translating the Adamic language based on like three or four words.

But still, even Phelps didn’t start to try and create a grammar until he had a translation of some words. Even he didn’t do that. Logically, this doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t make sense that they would try, and no one ever had, and I think still no one ever has. And so, this suggests rejecting the hypothesis. It’s not strong, it’s not conclusive, but it suggests rejecting the hypothesis.

Historical Sources Test

Now, let’s look at something we can test much more firmly, and that’s the historical sources. What do the historical sources tell us about the translation and how it happened? So, we’re going to look at the official history of the Church. Not what will become, but it was an official history of the Church. The entries we’re going to look at were probably written by W.W. Phelps and probably written later. But still, Phelps was an eyewitness. He was there when all this was happening and was very much a part of the process.

And Phelps says in the history that the next day after Joseph Smith receives the papyri, that the next day he brought a translation which Chandler, who they were going to purchase the papyri from, looked at and examined that translation. And so, the very first day, Joseph has a translation. Let’s keep that in mind.

A little bit later, that same history writes this, “Immediately after acquiring the papyri,” so he brings a translation beside the papyrus, then” we commence translation of some of the characters or hieroglyphics,” and “the Lord is beginning to reveal the abundance of peace and truth.” So, again, the first thing is translation, and both of the official entries that we get there, the first thing is a translation. That’s what we get. Alright, words like reveal are used, nothing about a grammar is mentioned.

Okay, then after a few weeks of journal entries, and again, these are all being made afterwards, but still, they’re trying to reconstruct how things happened. Then they write, “The remainder of this month, I was continually engaged in translating an alphabet of the Book of Abraham and arranging a grammar of the Egyptian language as practiced by the ancients.”

John Riggs

So, the first thing we get are mentions of translations, and later, a mention of an alphabet and grammar. That exactly fits with the logic test, right? Because logic is, you have a translation, and then you use that translation to try and create a grammar. So, so far, the historical text matches with the logic text. But we have a lot more in the historical record.

John Riggs, who is a young man, whose father owned the inn where Michael Chandler stayed and was the boy who was sent to get Joseph Smith the night that the papyri were brought there, and was told that Joseph was busy and he’d come the next day. And he went back and relayed that message and then he was there when Joseph came the next day.

And he tells us that Joseph wanted to take the papyri home and examine them, and that his father, and by the way at this point John Riggs is not a member of the Church, and his father Gideon Riggs is not a member of the Church, his father vouched for Joseph’s character and that convinced Chandler to allow Joseph to take the papyri home and examine them.

Alright, so we get all of that from John Riggs. And then this is what John Riggs says, “the morning following,” so Joseph has brought them home, looked at them over that night, “the morning following, Joseph came with the leaves which he had translated, which Oliver Cowdery read.” So that means in one day Joseph Smith had produced several pages of translation.

Not a grammar and alphabet, that’s not what is mentioned, but a translation. Several pages of a translation. Which also suggests that we’ve translated a little bit more than two chapters, but anyway, so we’ve got that eyewitness account.

Timing

Joseph Smith will also say in that history we were talking about, and again this is probably actually Phelps recording it. But anyway, “I with WW Phelps and Oliver Cowdery as scribes commenced.” Then this is written above the margin, “translation of some of the characters” or hieroglyphics, “and much to our joy found that one of the rolls contained the writings of Abraham.” Again, it tells us immediately translation happens. In all accounts so far, everything they say, translation is first, that’s what they see.

This is a second-hand account. Benjamin Bullock is the man who was related to the Kimballs and came with Michael Chandler to Kirtland. Not a member of the Church, and we have his account as given from his granddaughter. So it’s a secondhand account, but this is what he passes on to his descendants as they remember it. “Joseph Smith first used the Urim and Thumim to determine that the papyri were of interest and that he produced a translation that first day.” Now it’s second hand, years later and yet it matches so well with what others.

The Urim and Thumim, no one else had mentioned that at this point. We’ll see that mentioned again in a moment but this idea that he produced a translation that first day matches so well. We’re just getting a variety of witnesses that that’s what happened.

Pratt’s Account

Orson Pratt is a second-hand account of the first day. He wasn’t there on that first day but he is a firsthand account of some of the time of translation. And this is what Orson Pratt says,

The prophet translated the part of these writings which as I have said is contained in the Pearl of Great Price and known as the book of Abraham. Thus you see one of the first gifts bestowed by the Lord for the benefit of his people was that of revelation. The gift to translate by the aid of the Urim and Thumim. The gift of bringing to light old and ancient records.”

Again, nothing about a grammar and alphabet. The historical record is all about translation through revelation and gift from God.

Eyewitness Accounts

Warren Parrish, who at the point time he gives this statement is an enemy of Joseph Smith, no longer a believer, this is how he described, and he’s a scribe. He is very much a first-hand witness. He says, “I have sat by his side and penned down the translation of the Egyptian Hieroglyphics as he claimed to receive it by direct inspiration of Heaven.” Again, nothing about grammar and alphabet. Parish has some handwriting in the grammar and alphabet, he’s very familiar with it, he knows what it is, and when he describes the translation process he says nothing about that, he uses direct inspiration.

Now this gets to be hard to argue against. If you want to claim that it’s by any method other than direct inspiration or revelation from God, you have to disagree with every eyewitness account about it.

John Whitmer, who may not have been there the first day but is around enough he must witness some of this, he says, “Joseph the seer saw these records and by the revelation of Jesus Christ could translate these records which gave an account of our forefathers.” Again, revelation is the word he uses, not grammar and alphabet.

I know I jokingly put ‘fourth hand account,’ it’s really a third hand account. She’s not an eyewitness to the translation process but she’s heard about it from her son and she’s the one who shows the mummy and some papyri and so on to others, and then we get what she says from others as they record it from at least a couple of different instances. And so this goes through a few filters but in each case, they talk about what Lucy Mack Smith said regarding the translation. There are at least two times where they say not only that it happened by inspiration, but that Lucy claimed that Joseph could translate parts of the papyrus that weren’t even there.

Lucy Mack Smith

At one time she compares it to Daniel knowing King Nebuchadnezzar’s dream even though he hadn’t seen it. It can only happen through inspiration or revelation. So again Lucy Mack Smith believes that this happens through inspiration and revelation so again every historical account talks about inspiration and revelation nothing regarding grammar and alphabet as a tool of translation. If it was the tool, you’d think one person would have said it once somewhere, but that’s not what we get.

So if we continue to look at how we’re testing this, the logic test suggests that we reject it, the historical test says reject it–the hypothesis is incorrect according to the eyewitnesses, the people who are actually there. That’s not how the translation happened.

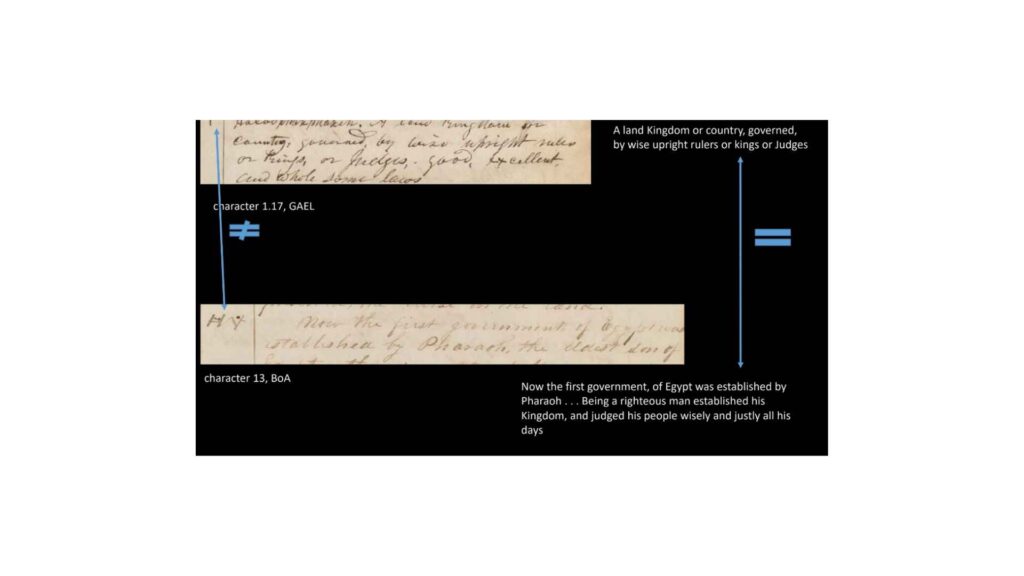

Documents Test

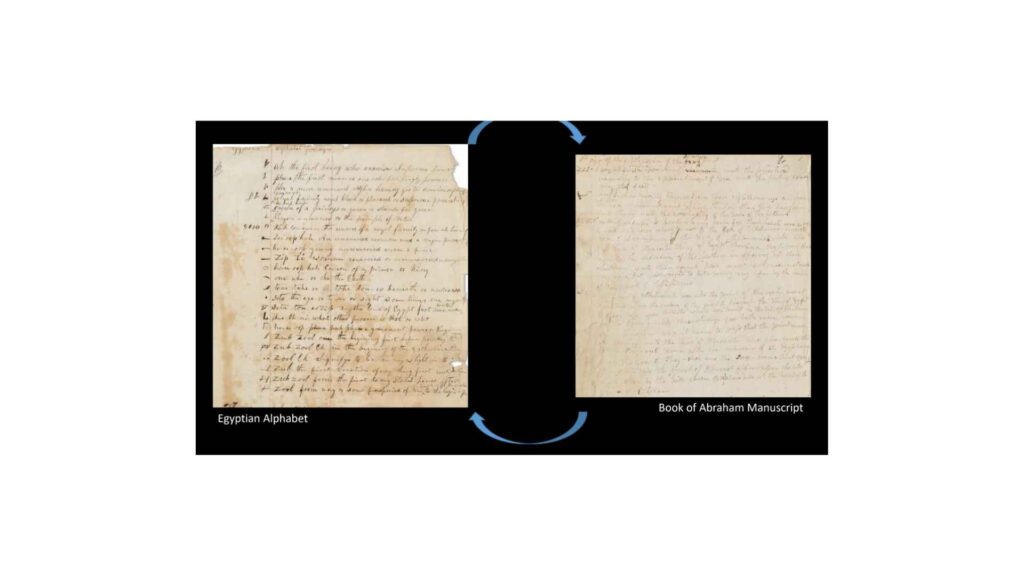

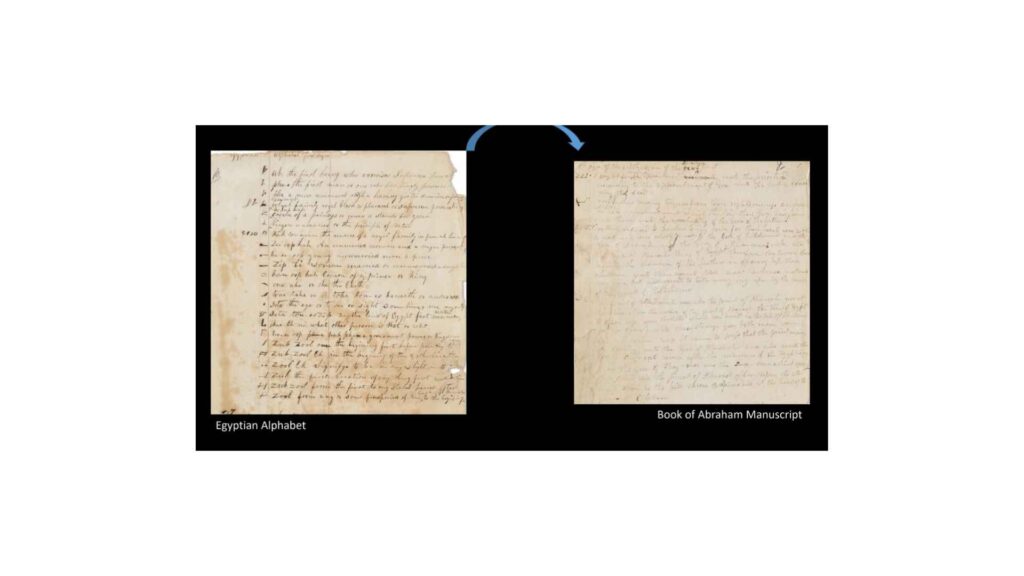

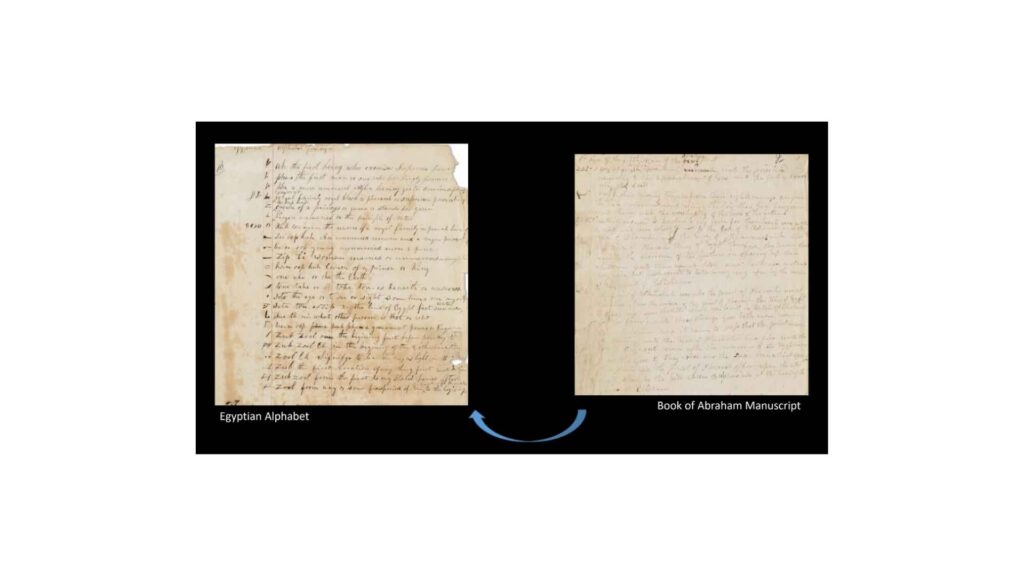

Now let’s look at the documents test and this is the part where we’ll get a little complicated but I’m confident we can get through this and understand some of what is going on. The idea is, and let’s say that as we look at the documents we’re actually only testing one part of this idea. So, if we were to go back here, remember that the hypothesis we’re testing is whether the Egyptian alphabet and the grammar and alphabet of the Egyptian language was the tool that was used for translation, and we’ve been able to look at that large hypothesis as we’ve looked at the logic test and the historical test.

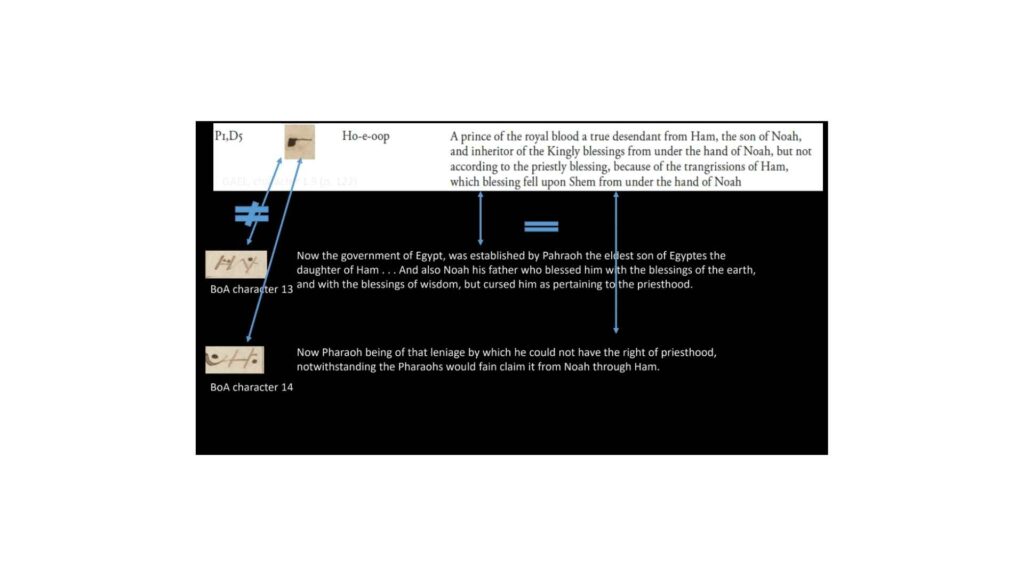

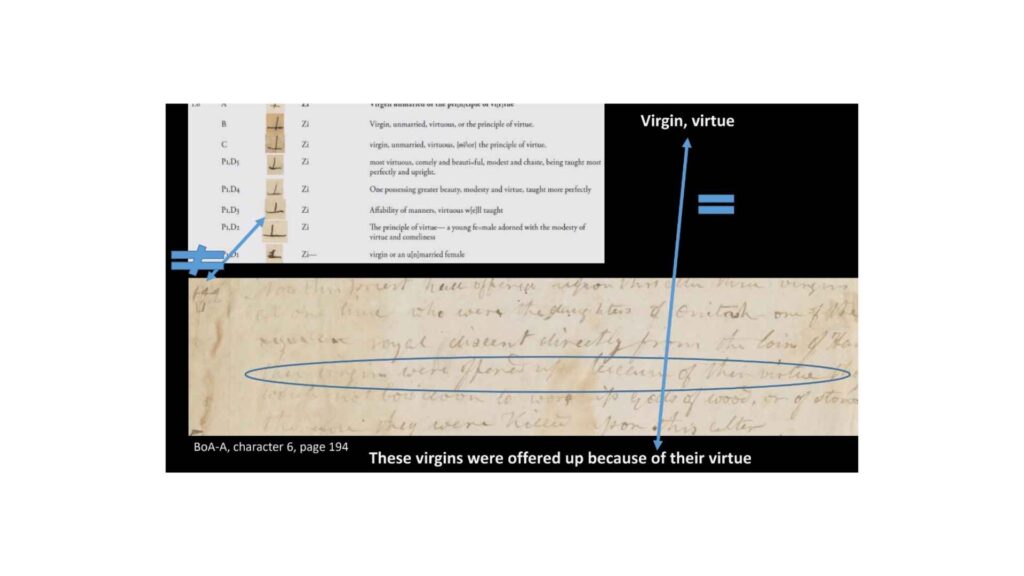

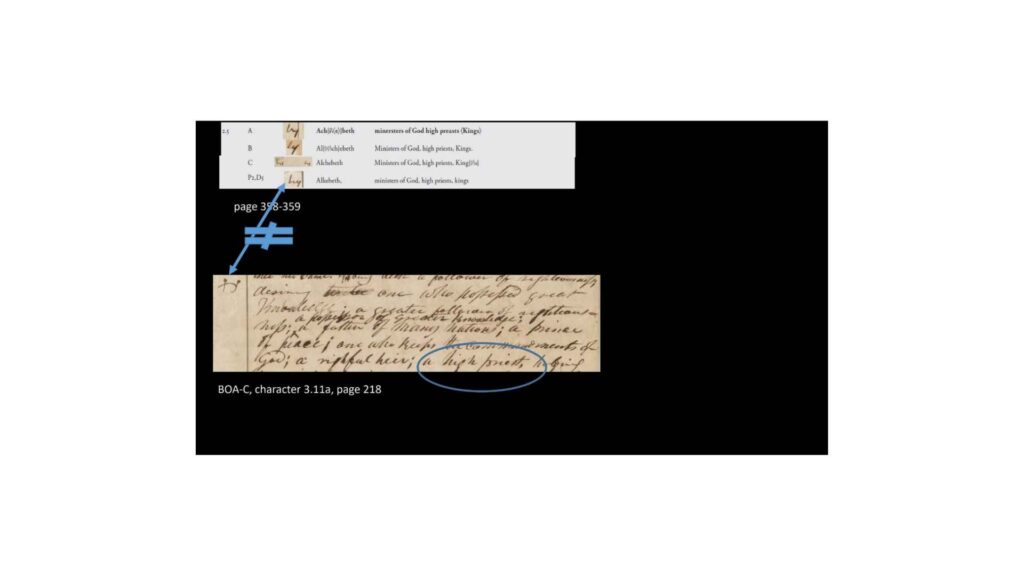

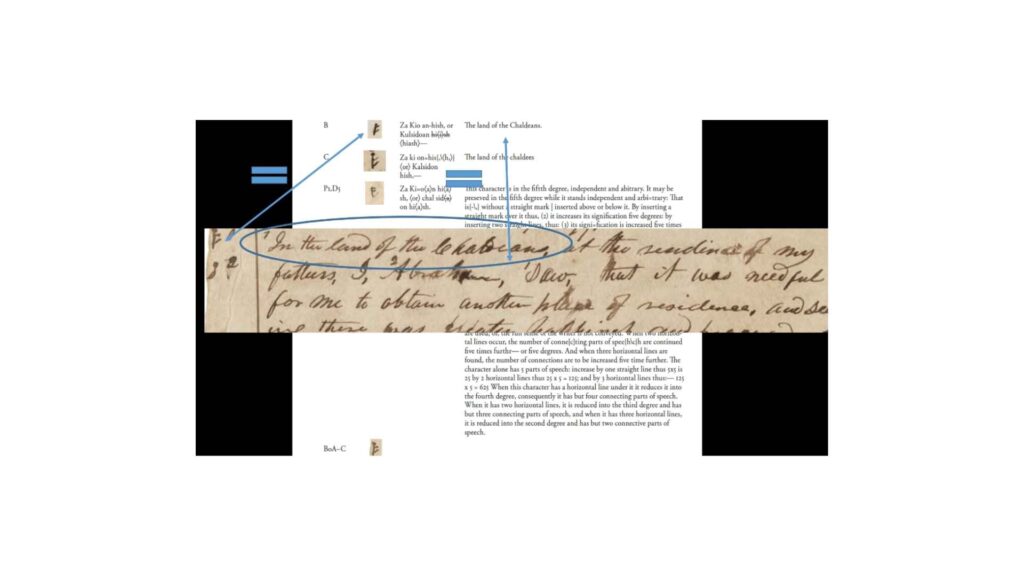

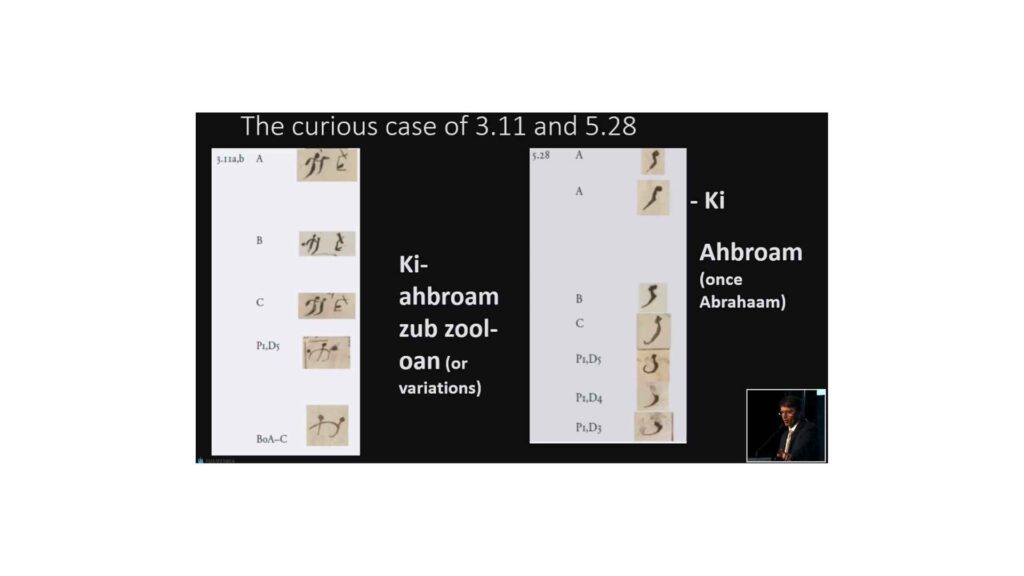

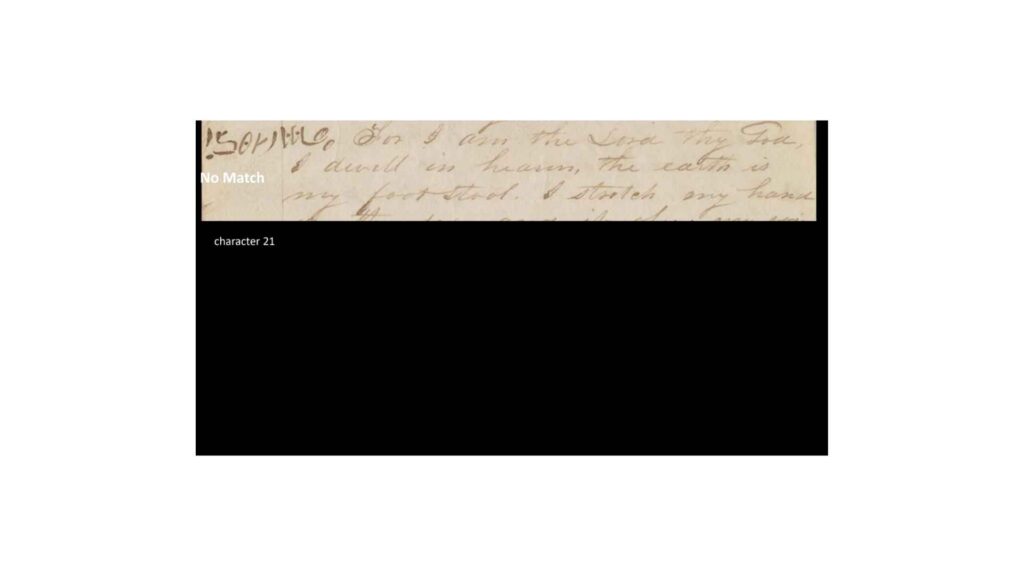

As we look at the documents test, we’re going to look at only a subset of that. If you look here, what we have on the left hand side, the Egyptian alphabet, one of the Egyptian alphabets. And you’ll see as I go through, I’m not going to explain it every time, but there are three; so they’re labeled a, b, and c. And then we’ve got Book of Abraham manuscripts, and they’re a, b, and c, and so on.

I won’t talk about a, b ,and c, each time. They’re on the PowerPoint so that you can see which one when you want to, but you can see that in the Egyptian alphabet, there are characters on the left and then there are often definitions or explanations and all sorts of interesting things on the right. And they’re not always uniform; they’re done differently by different scribes and so on.

Grammar, Alphabet, and Translation

Then, if you look on the right, you’ll see a Book of Abraham manuscript. And you’ll see there are characters in the margin, and then there’s the text of the Book of Abraham on the right. The going hypothesis for those who subscribe to the idea that the grammar and alphabet was used to translate the Book of Abraham, the most common way that is expressed is to say that the grammar and alphabet was used to translate the characters in the margin of the Book of Abraham manuscripts.

So, those on the right, the Book of Abraham manuscript, you can see those Egyptian characters on the left, that the grammar and alphabet was used to translate those characters into the text that we see on the right of the Book of Abraham manuscripts. So, it’s that specific subset of the hypothesis that we can test as we go through and look at the documents, all right?

The question is, did the grammar and alphabet yield the Book of Abraham manuscript, or was the translation of the Book of Abraham used to try and recreate a grammar and then alphabet? And it may be that it’s something completely different. In fact, the more I look at this, the more I think that we don’t understand at all what the relationship is between these documents, but those are the two kind of going hypotheses.

Now, of course, there’s a whole bunch of stuff in these alphabets and the grammar and alphabet that aren’t in the Book of Abraham text at all. The question is, is that because they’d already translated more and they’re using portions of the translation we don’t currently have, or is it because they’re just coming up with other sources? And in the end, we don’t know.

Complex Matters

In fact, what I should probably stress about this is that there’s a whole lot we don’t know, and everyone who acts or pretends like we do know is oversimplifying for you, and that’s something you should be very careful of. In fact, I believe Dr. Gee will speak about this later, but all of our studies having to do with the ancient world and ancient texts or studies having to do with modern translation by revelation or with the Egyptian documents, these are always in all cases complex matters, and you can only study them in a complex way. Anyone who gives you a really, really simple explanation, you should have some questions about that. It’s complex, and if someone’s simplifying, they’re leaving things out to try to make their point, and I would be suspicious in any case.

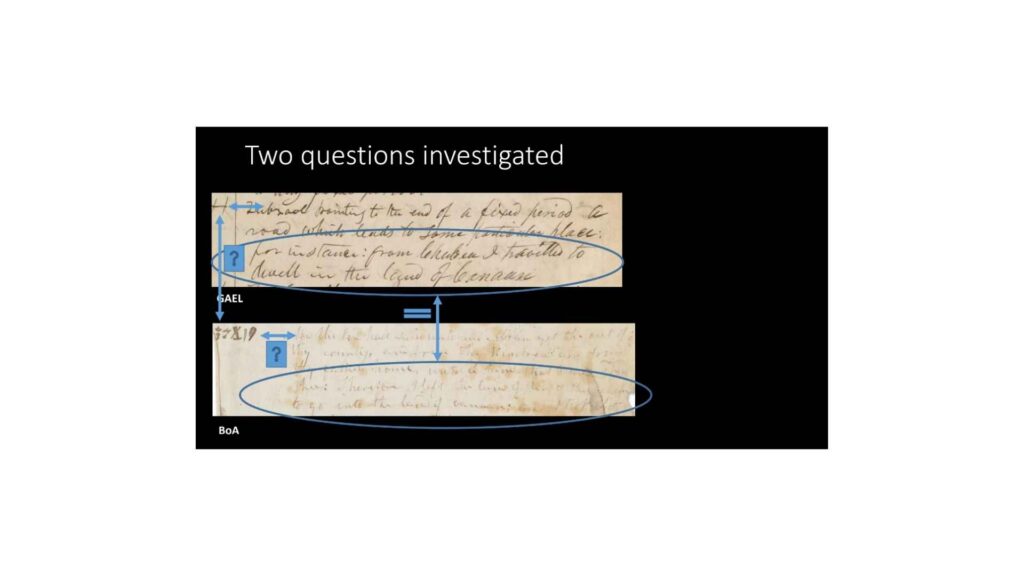

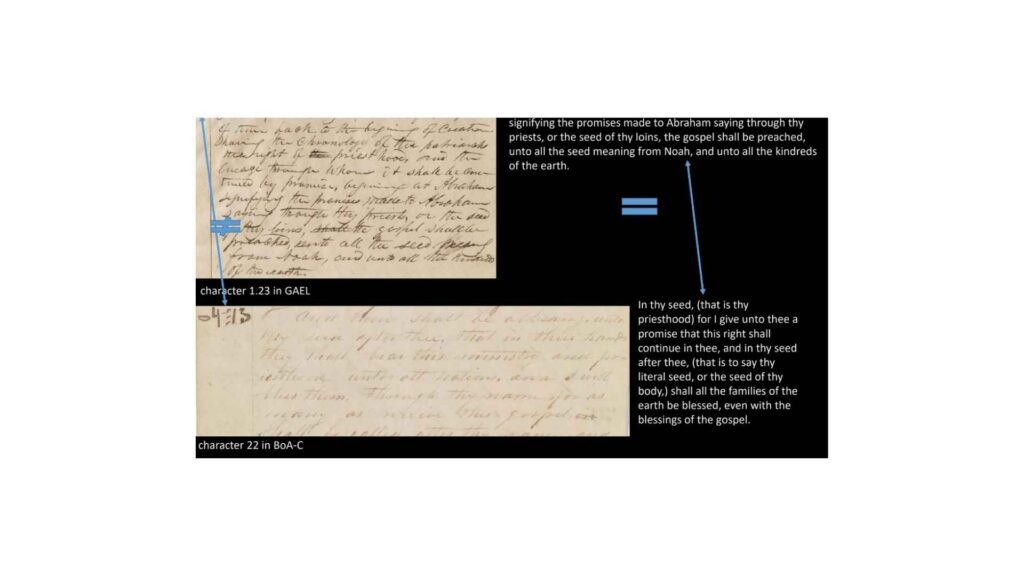

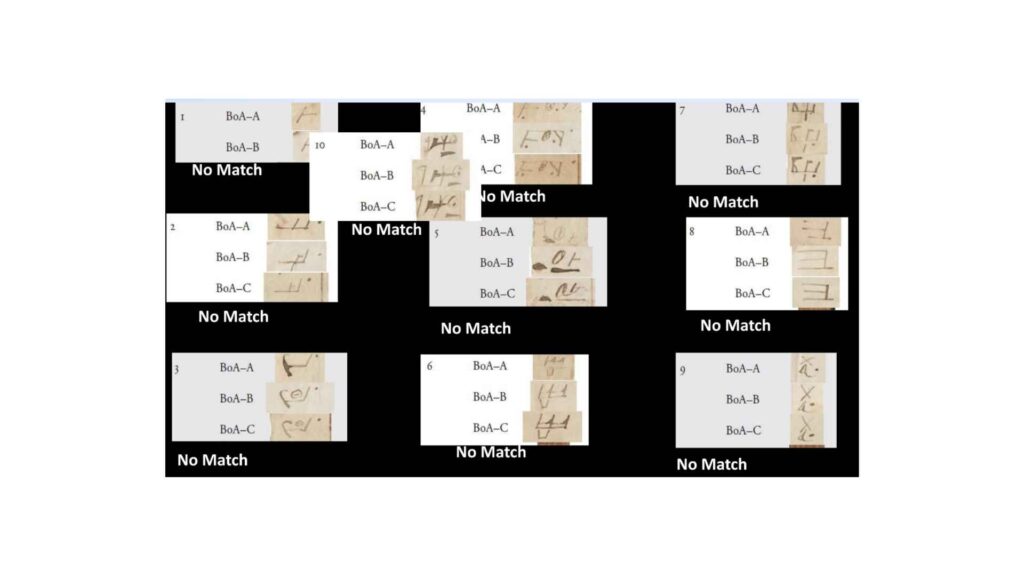

So, this is somewhat complicated, but hopefully, we can narrow it down. We’re going to look at two specific questions as we look at whether the grammar and alphabet was used to translate the characters in the Book of Abraham manuscripts into the text in the Book of Abraham manuscript. One is, we’re going to look at the Egyptian alphabets in the grammar and alphabet, and we’ll look at the characters in the margin and the definitions next to them, and then we will compare them to see when there is text that matches text in the Book of Abraham manuscript, that matches the text in the alphabet and grammar.

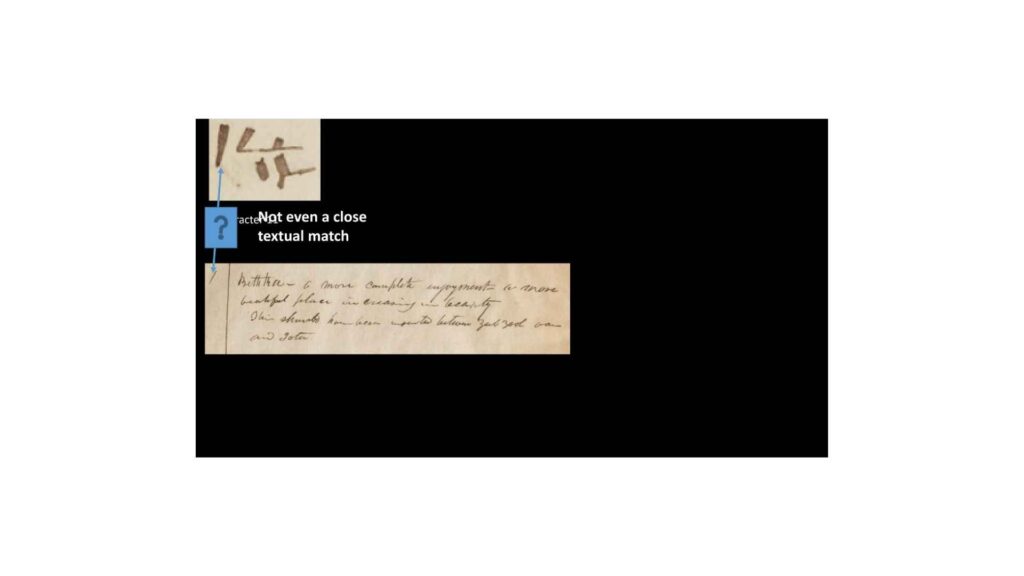

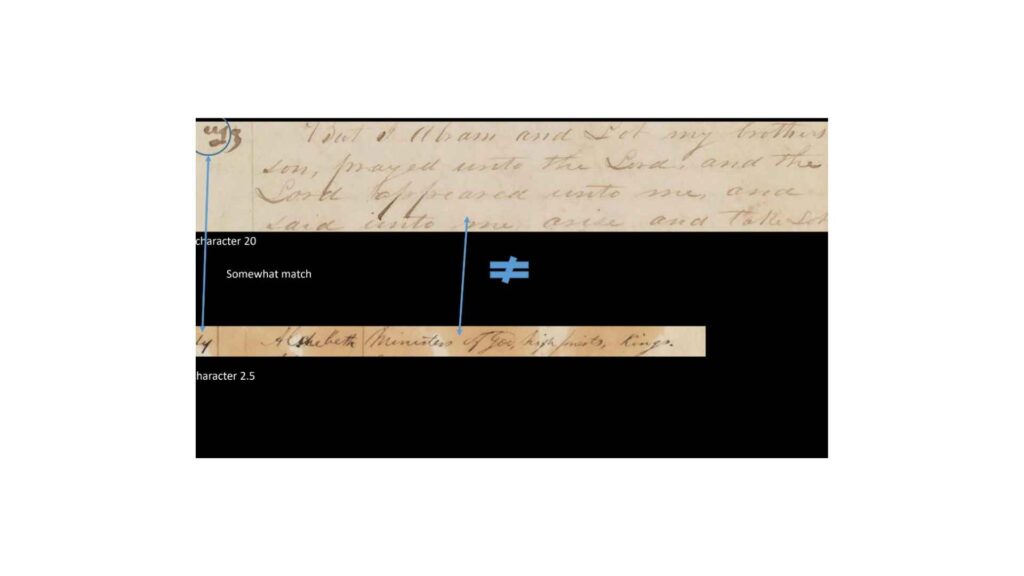

Translatable Match

So, you can see, in this case, that the text, it’s not a perfect match, but it’s a rough match. It’s a translatable match. So, when they match, do the characters match? So, you can see what we’re doing. If the grammar and alphabet is being used to translate the characters and the margins, then we should find some match between those, right?

The second question then is, we’ll look at, we’ll do it in the reverse order, so these are very related questions but you have to examine both. We’ll look at the characters in the Book of Abraham manuscript and see if we can find those characters used in the grammar and alphabet, and if so, does the text match in that case, all right? They’re similar things but you have to do both to be able to cover all of your bases.

First Question

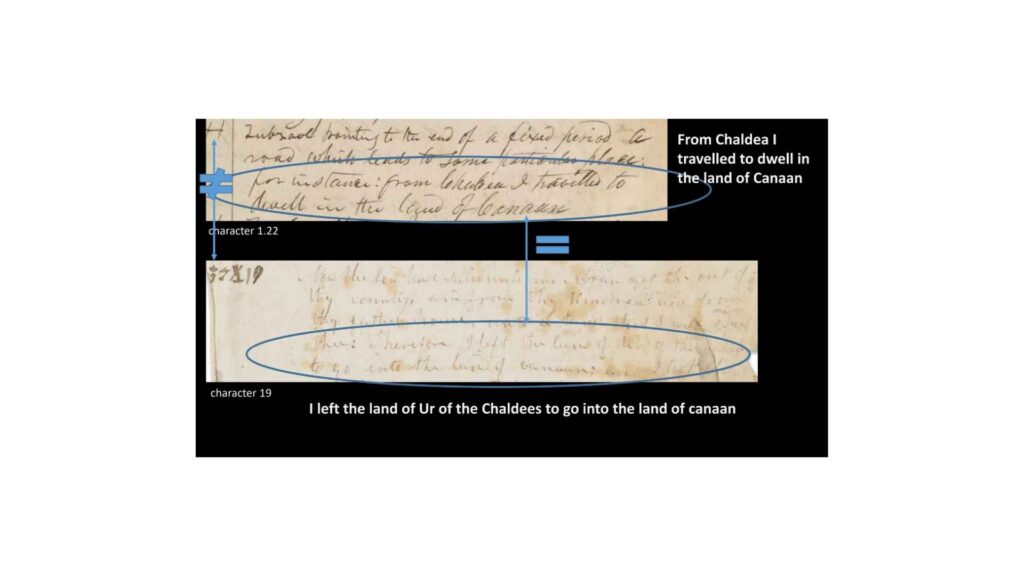

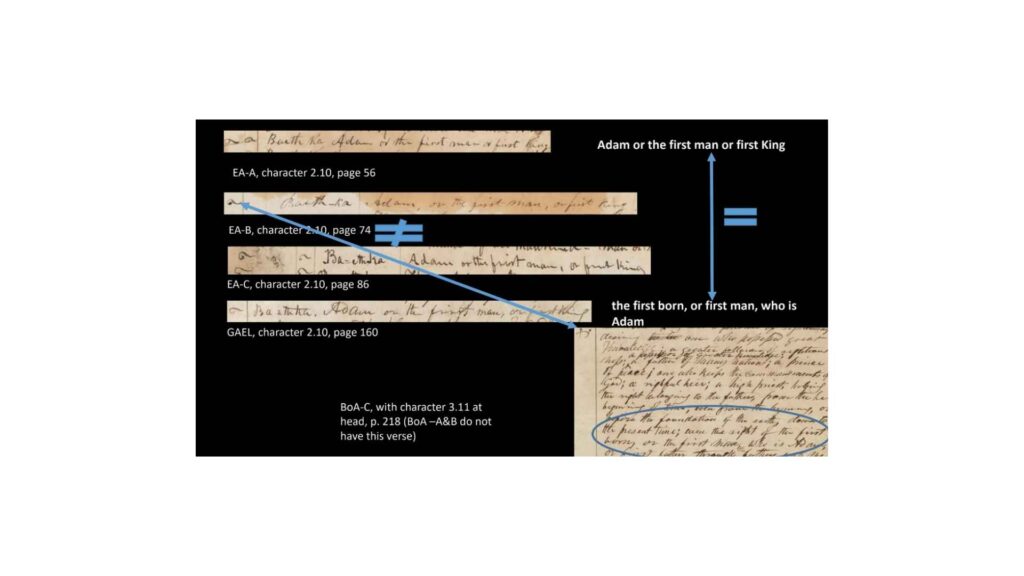

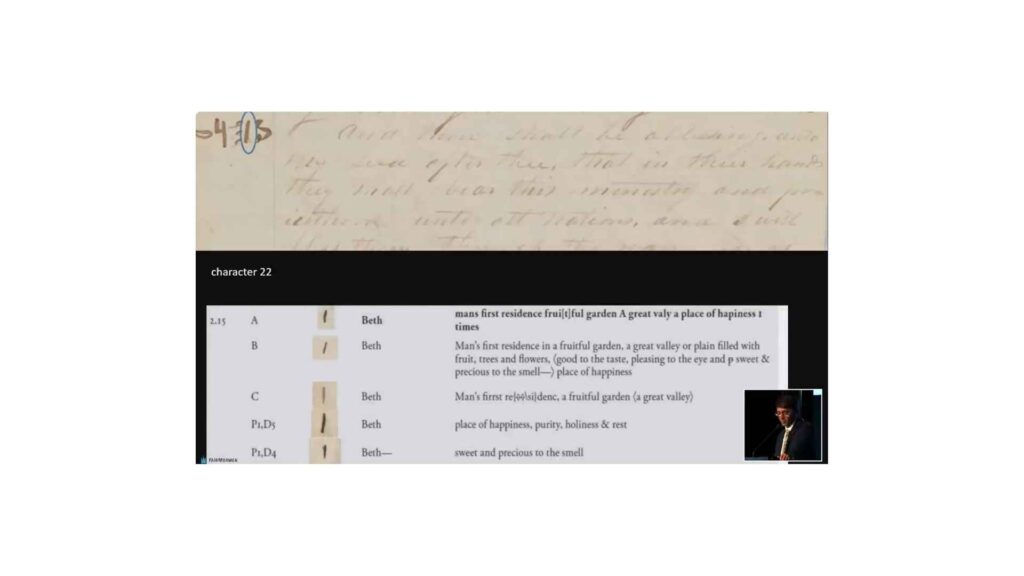

We’ll start with the first question, the idea of looking for textual matches in the grammar and alphabet in the Book of Abraham manuscript and see if the characters match, okay? So, we’re going to do this, and again, this is one of the wonderful beautiful things from Revelations Volume 4, that they have listed all sorts of characters and they’ve given them numbers, and that allows us to find more easily when we’re looking at the same character and it gives us the ability to talk about it.

So, I can say character 1.22, you may have no idea what that means, but you could go to Revelation Volume 4 and see. And I now have a number. I tried to do this once before they were given numbers and it was so difficult to talk about these things because I’d say, well, the character that’s the fourth character down and the left column on page five, and that was difficult.

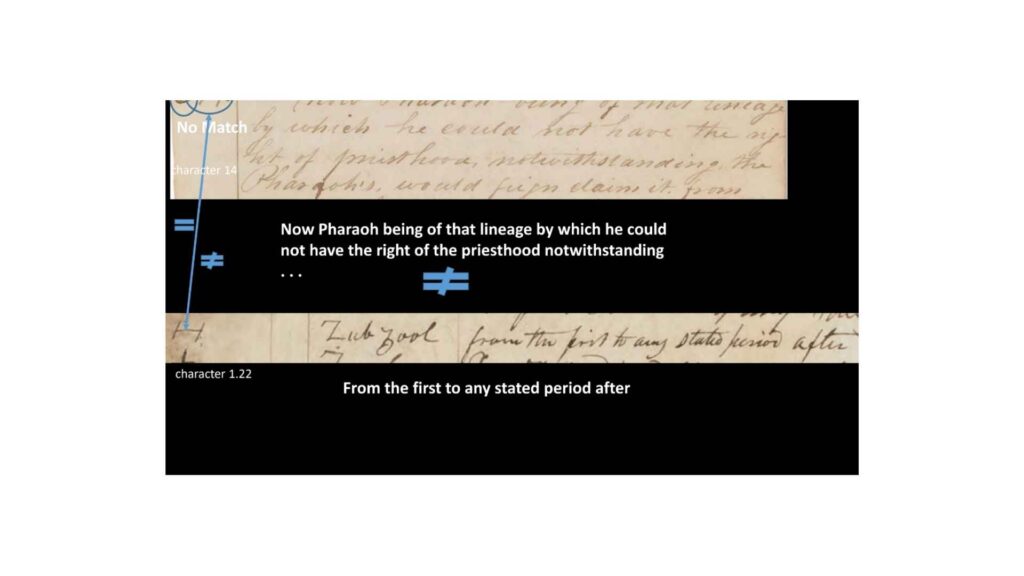

So, we’ll now talk about character 1.22 which you can see in the margin there, and you can see that the text talks about going from Chaldea and traveling into the land of Canaan, all right? So, “from Chaldea I traveled to dwell in the land of Canaan.” If we look in the Book of Abraham manuscript, we get “I left the land of Ur of the Chaldeas to go into the land of Canaan.”

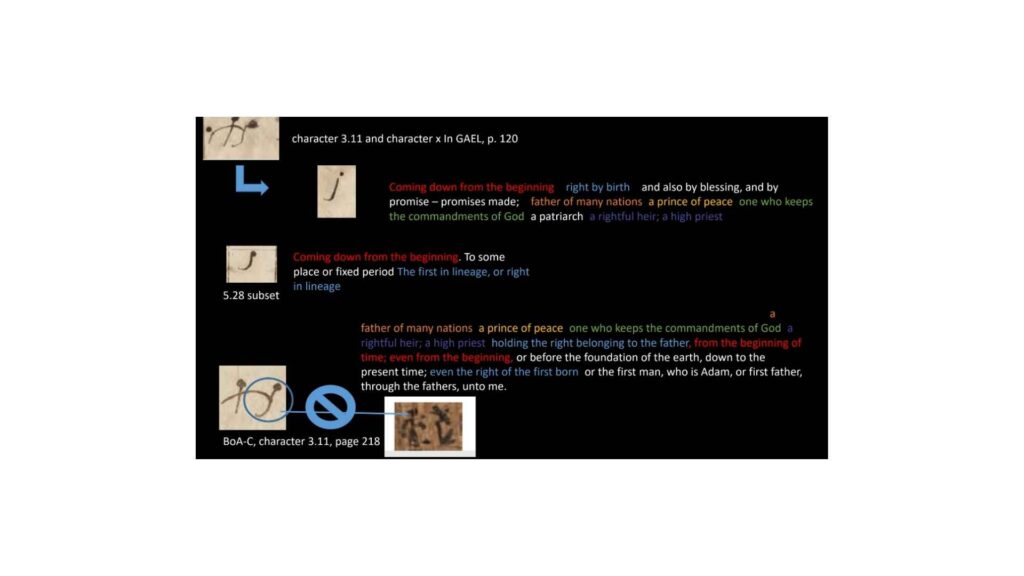

GAEL

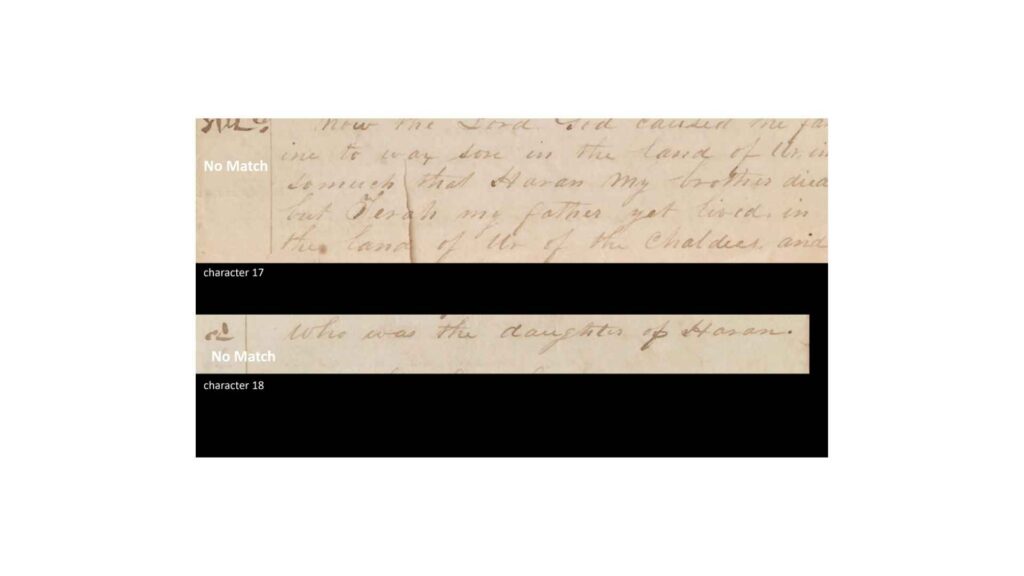

Not a perfect match, but that’s a good enough translation match. So the text matches fairly well there as you can see, but the characters do not match at all as you can also see. So this will get tedious. In a minute I’ll go through it more quickly, but I want you to get the idea of what I’m doing. This took a very long time to go through all these in a very tedious way.

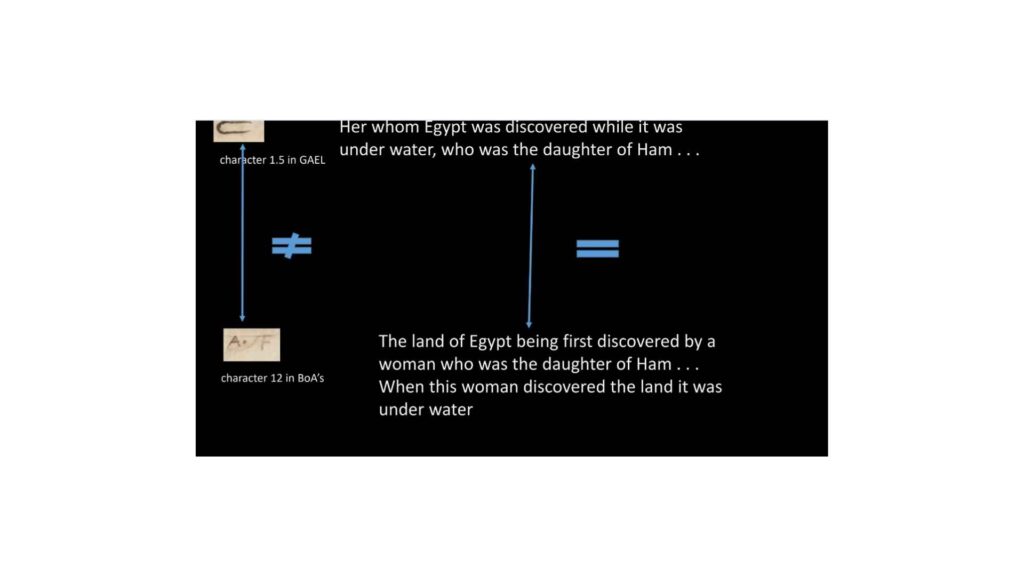

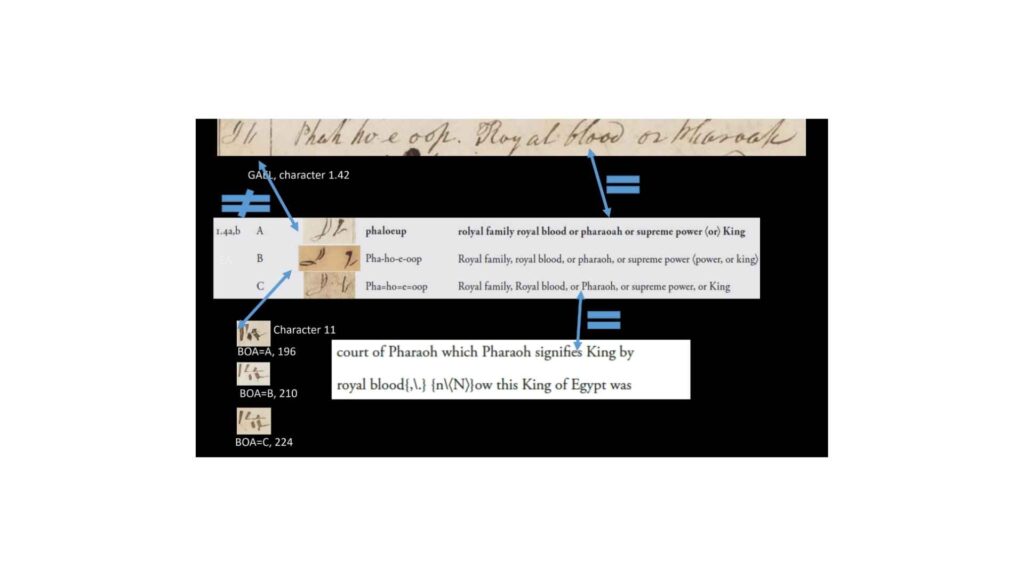

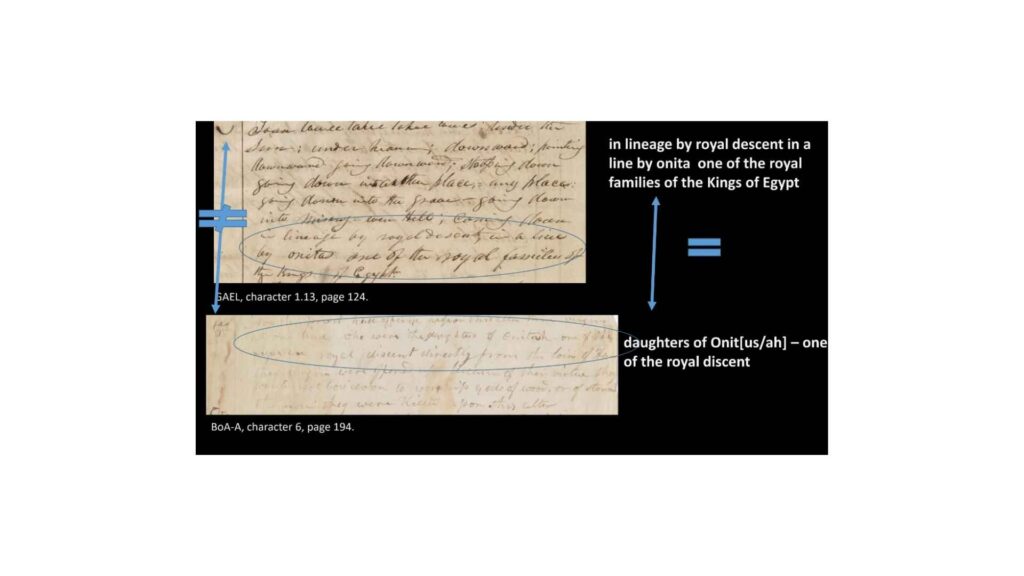

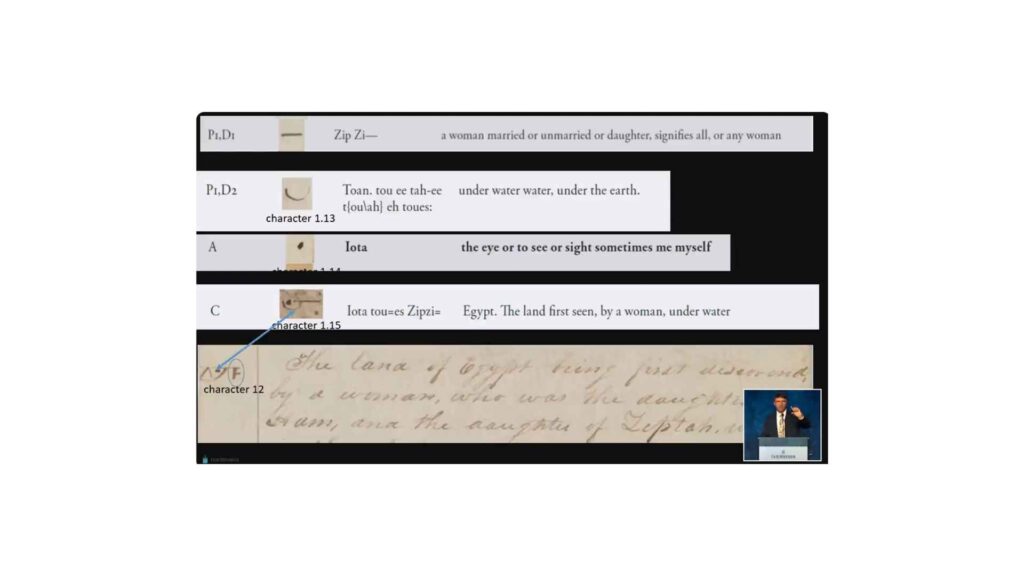

Character 1.5 in the GAEL has a definition of “Her whom Egypt was discovered while it was under water, who was the daughter of Ham. . . Character 12 in the Book of Abraham manuscript says “The land of Egypt being first discovered by a woman who was the daughter of Ham. . . When this woman discovered the land it was under water.” Alright, so you can see again, not a perfect match but a good enough match that we can say that’s a good textual match. But again, the characters don’t match at all.

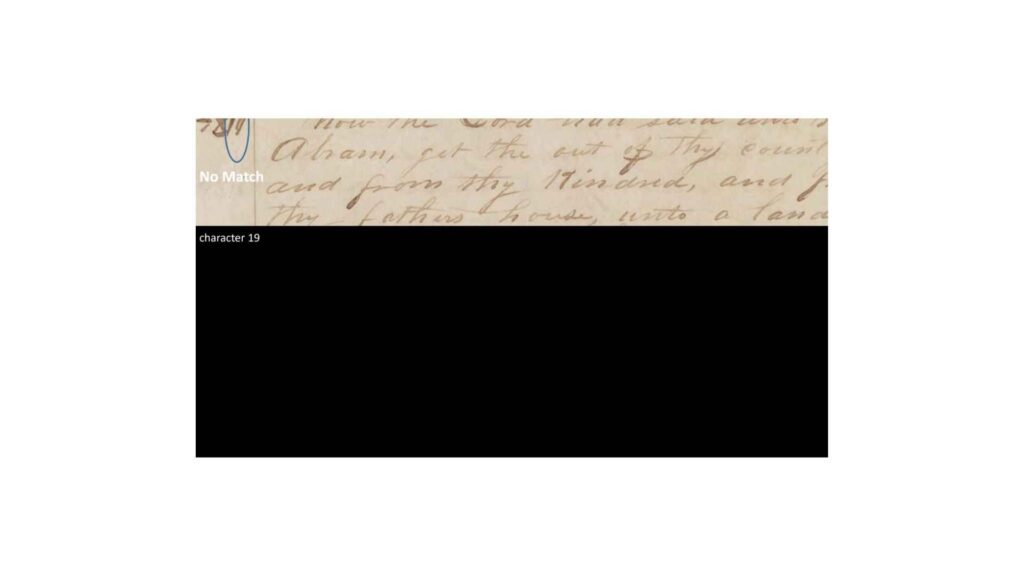

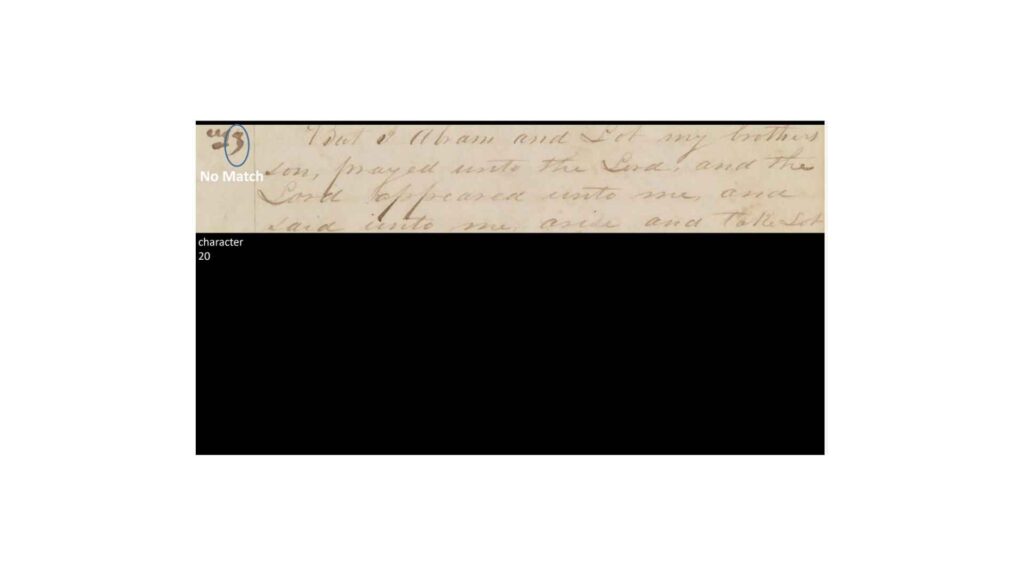

And now we’ll just go through this a little bit more quickly. You can see we’ve got text matches but the characters don’t match. And again, text matches but the characters don’t match. Then text matches but the characters don’t match. That just keeps happening with each textual match I was able to find. I tested it and in all the ones I’m showing you right now, when the text matched, the characters did not match.

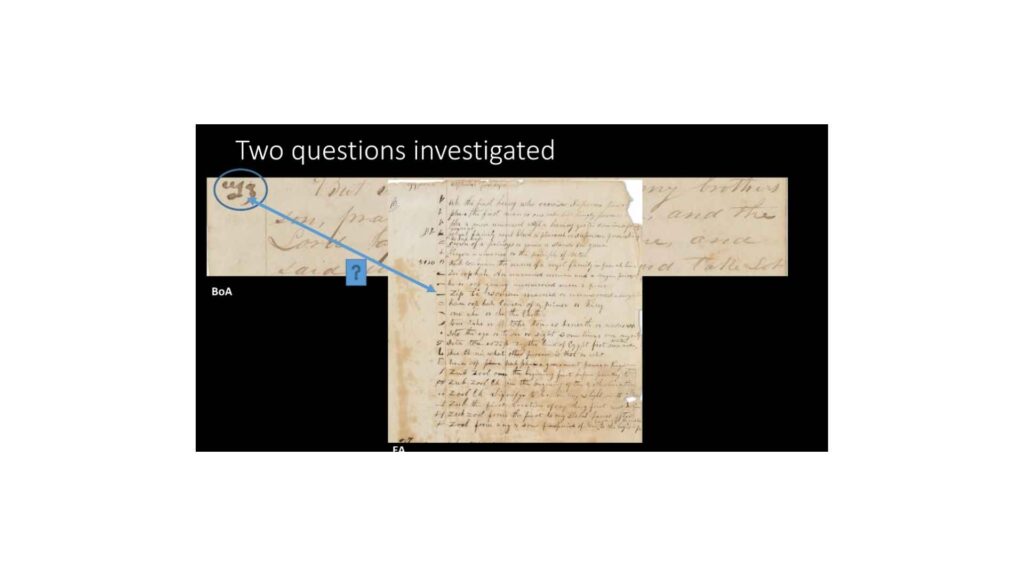

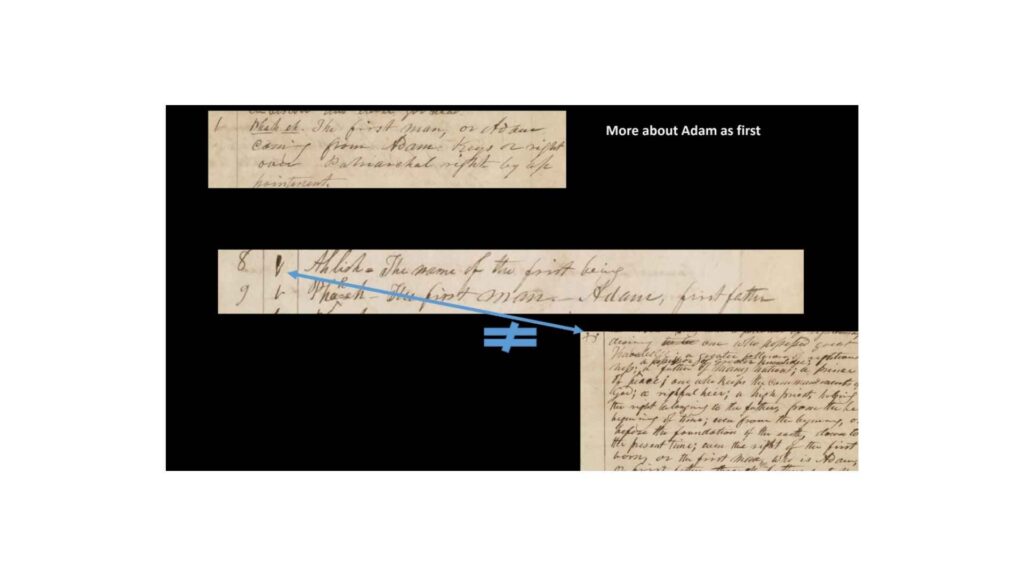

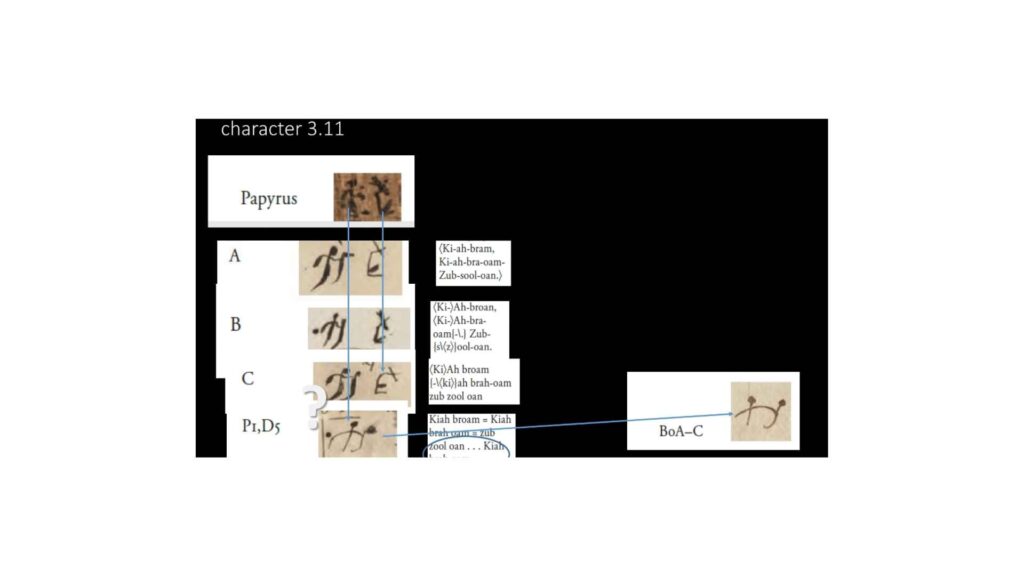

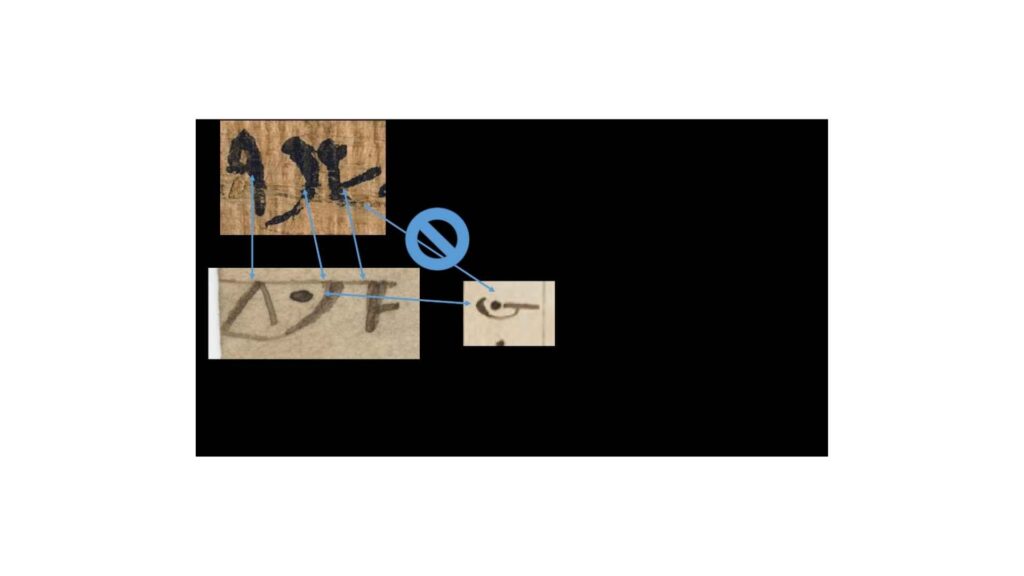

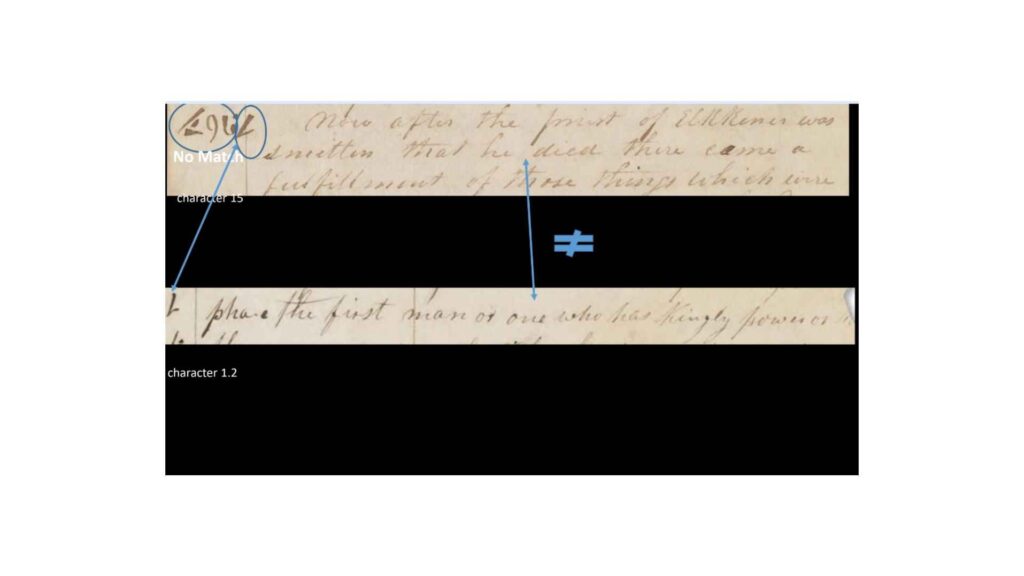

Here’s a really interesting one. So as we look at the characters on the papyrus—and that’s part of what we have to do as well, is look at the papyrus characters and see how they end up on the alphabet and grammar, and so on and so on.

Comparing Characters

(Papyrus) So here you can see these papyrus characters, and you can see how they end up in the Egyptian alphabet, and you can see how those characters, not particularly well drawn, but you can see how the papyrus characters become the characters that we find on the alphabet. It’s not perfect, but it’s a decent enough match.

(A) And then you can see in another one of them, so these are each documents written by a different hand, so in another one, still kind of, you can tell, but it’s not a great match. But I think it is the same one.

(B) This one, it’s even harder to tell, but I think they’re the same one.

(C) And then we get in the Book of Abraham manuscript, we get this.

So there’s nothing matching the character on the right and kind of matching the character on the left. In case you’re wondering whether these really are the same characters in the alphabet and grammars, and in the Book of Abraham, you see they all have the same transliteration. Oh sorry, the bottom one is the grammar and alphabet. I said it was the Book of Abraham, it’s the grammar and alphabet. And then we get that character in the grammar and alphabet showing up, or it seems like the same character showing up in a Book of Abraham manuscript.

It Seems to Match

So this would suggest, in this case, that it came from the papyrus. Because if we go back, you’ll see that the Book of Abraham manuscript, you cannot recognize that as having to do with what’s on the papyrus at all, but you can see it kind of going through variations that could arrive at that symbol. And so if that were the case, then that would suggest that the Egyptian alphabet was used to at least create the character that is on the Book of Abraham manuscript. But it turns out this one is not so simple.

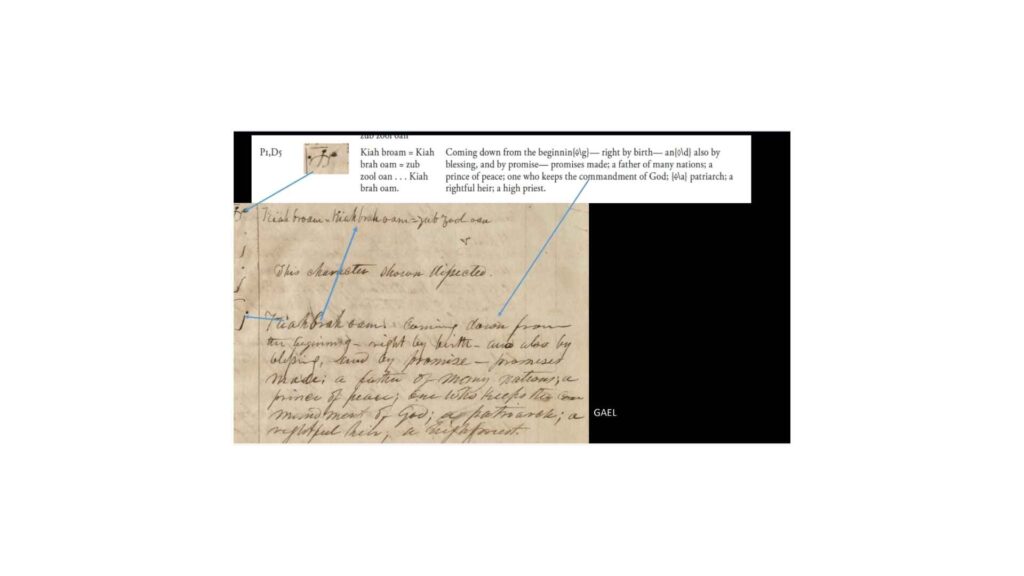

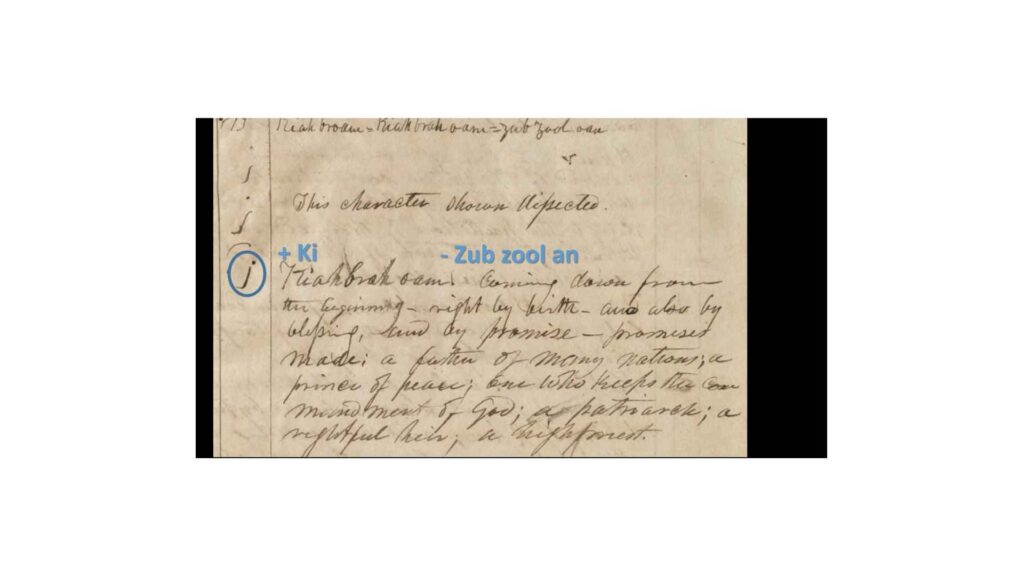

This one’s actually quite complicated, and I’ll try to show you why. So we have there the grammar and alphabet character, and I’m showing you the actual writings in the and the typescript of it, so that you can read it a little bit more easily, typed up there.

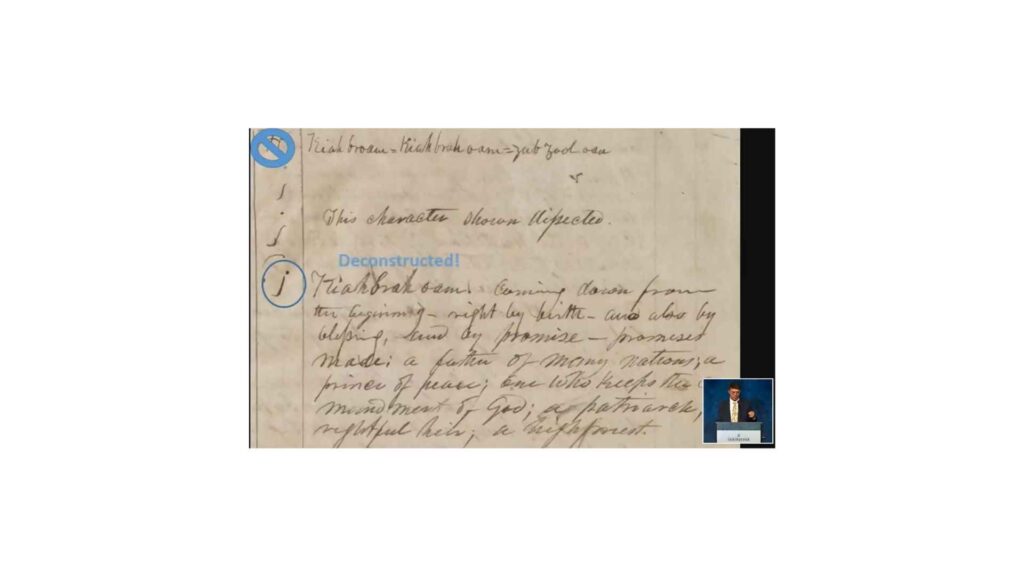

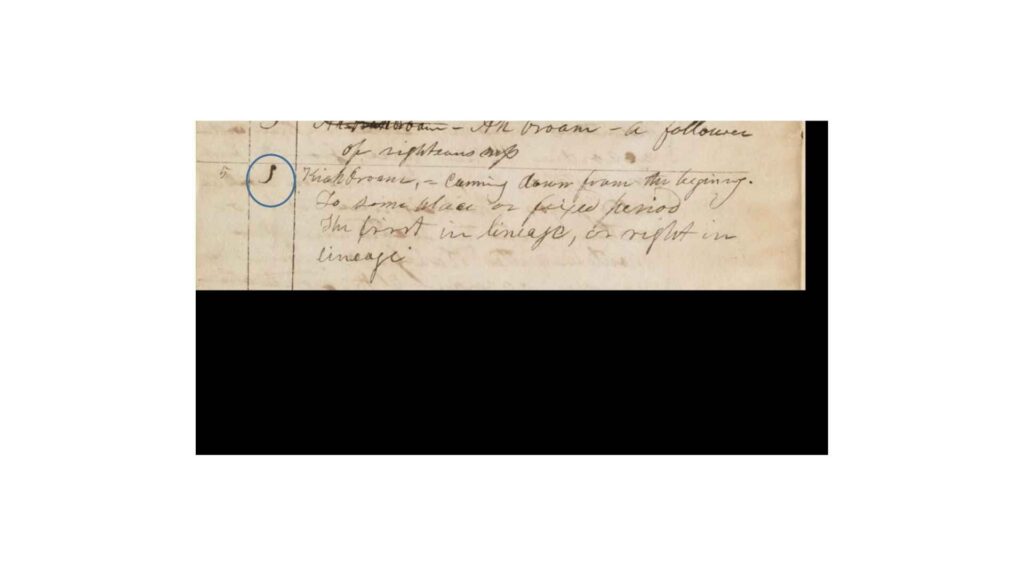

So we’ve got that actual character, in the GAEL or the grammar and alphabet of the Egyptian language. And you can see in the up at the top where you’ve got the full character, it says “Kiah broam, Kiah broam, zub zool oan.”

But in that bottom part, and I want you to look in the middle, so you’ve got it saying “Kiah broam, zool oan.” And then you say, this character shown dissected, and then you just get parts of the character, and one part of the character does say “Kiah brah oam.” So it seems to match that text up above.

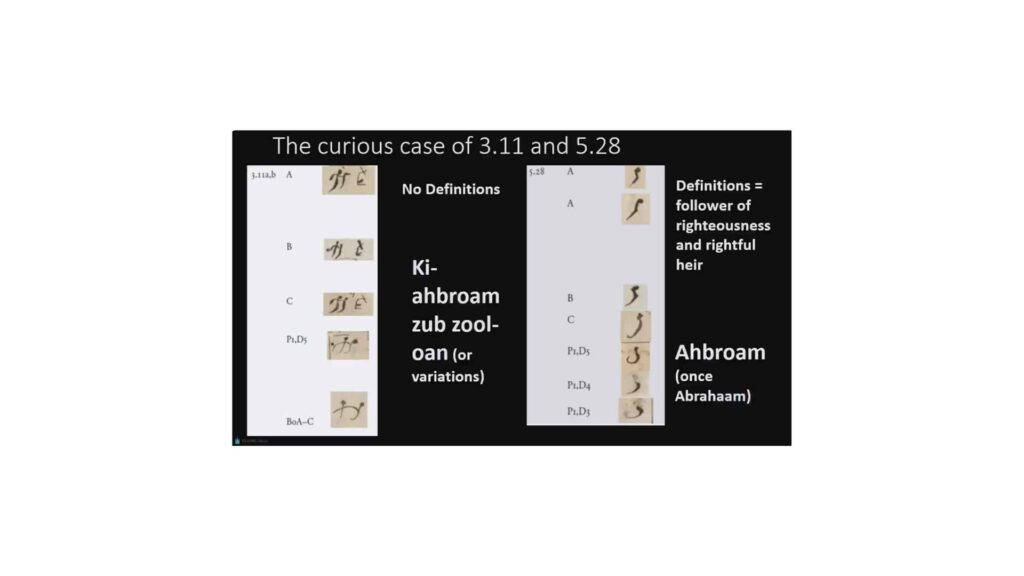

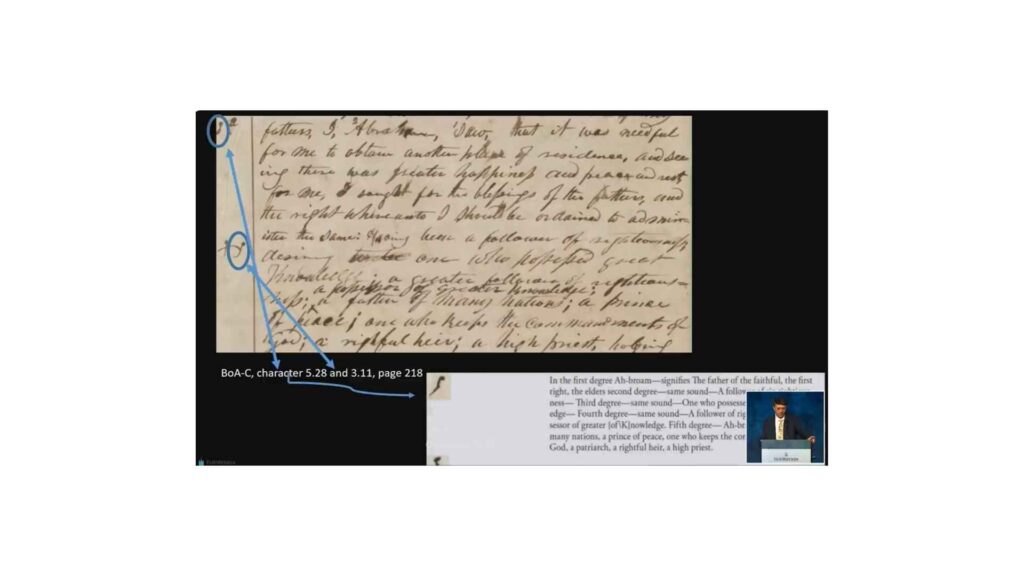

“Follower of Righteousness and a Rightful Heir”

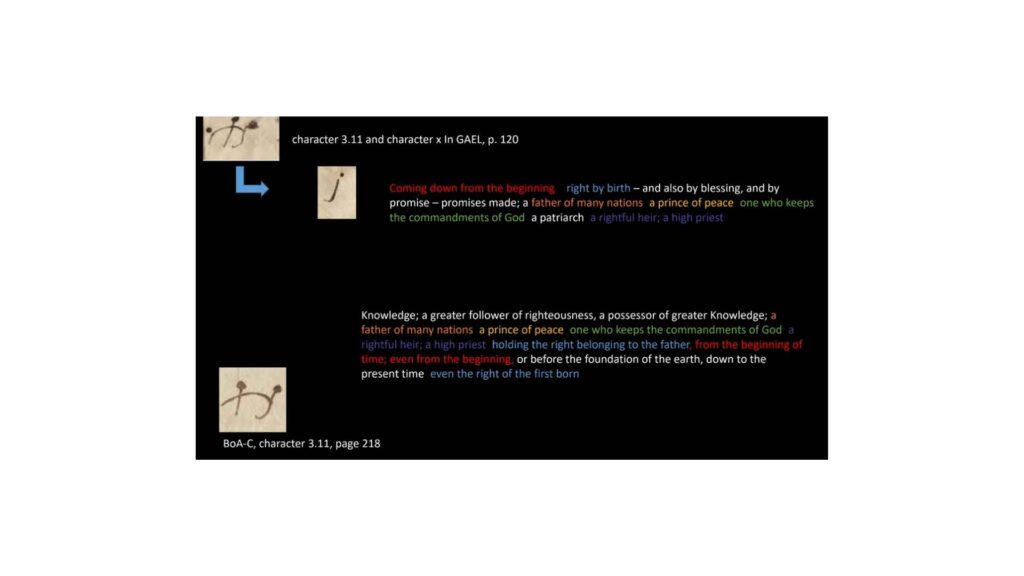

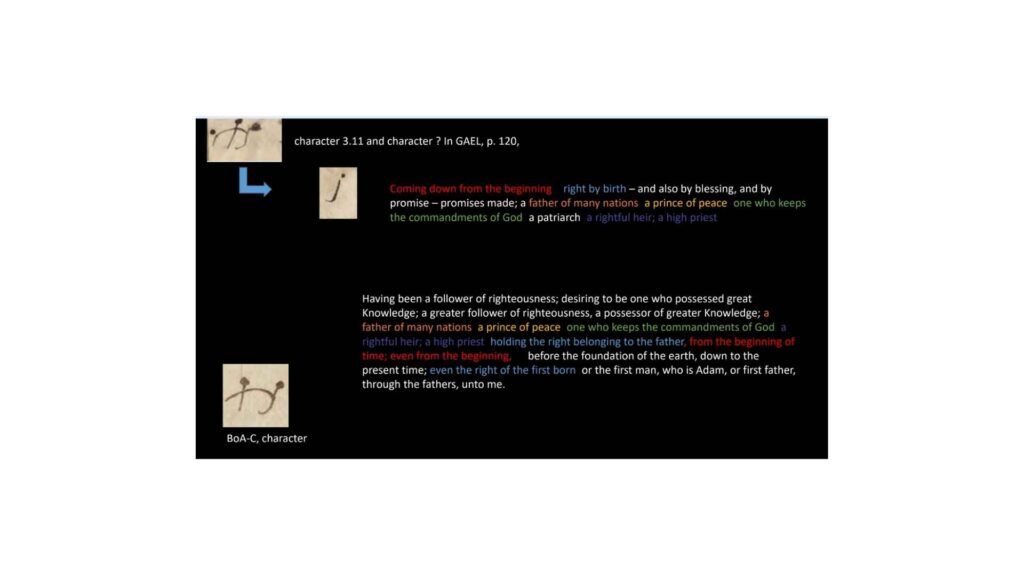

But the interesting thing is that we have another character that’s labeled. So the characters on the left are labeled character 3.11 and the character on the right is 5.28. And that one is Ahbroam, alright, Ahbroam (once it’s Abrahaam). So, and you can see that it is similar to the right-hand part of character 3.11, which is Ki-ahbroam zub zool-oan, or its variations. So 5.28 doesn’t have Ki and it doesn’t have zub zool-oan.

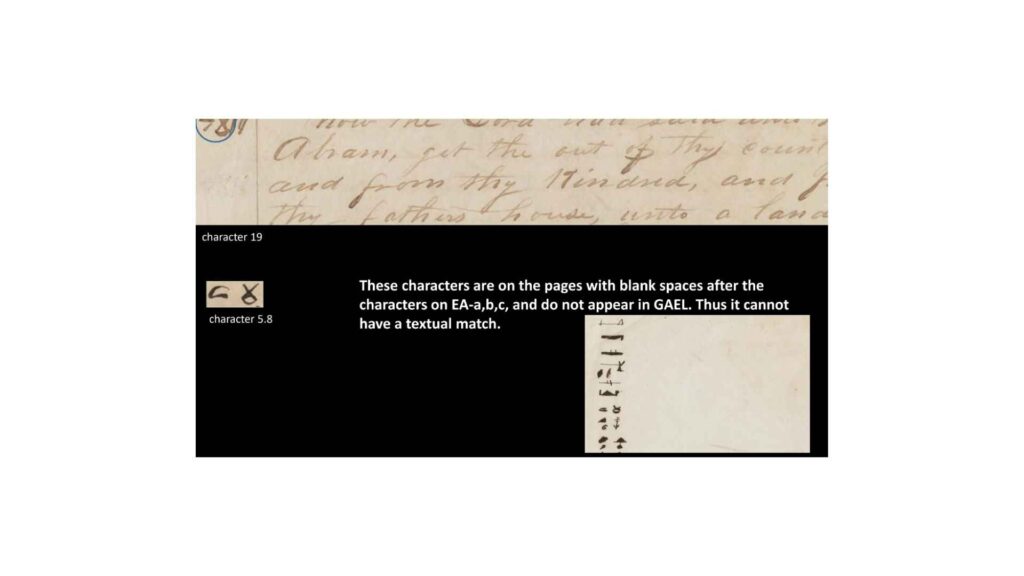

But let’s look at this character that was not given a number in Revelations volume 4, but that’s because they were just creating the tool that now allows me to do this analysis to see, oh, there’s something going on here that it should have had a number. I’m not criticizing them for that, in fact, they’ve told me, oh yeah, now I see that we should have given that a number, but they created the tool that made it possible for us to see that.

So we’re going to call this character x. And character x, you see the Kiahbrah oam, right there, it has the Ki added, that’s different than what’s in 5.28, but it doesn’t have the zub zool-oan, alright.

3.11 and 5.28

Now as we look at this character in the Book of Abraham manuscript, you can see that it’s got 5.28 up there, and then it’s got 3.11, but that part of it is similar to 5.28, and you’ve got a textual match there. They do seem to be similar with that textual match, right, just for that part of the character which agrees with the character 5.28.

So the whole character doesn’t match but the partial character does match when it’s deconstructed. And that character actually seems to have become a different character. That 5.28 when it’s deconstructed or dissected, it seems to become a different character that is used elsewhere and that’s when we get the textual match when it’s used elsewhere.

So it may actually be that it’s not character 3.11 that matches but it’s character 5.28 and so this may not actually show us anything about that little trail we saw of the papyrus characters and how it came down into various characters in the Egyptian alphabet and grammar because this translation seems to be coming from a different character, but we can’t be sure. In any case, this little part of it here does not match in any way at all what’s on the papyrus.

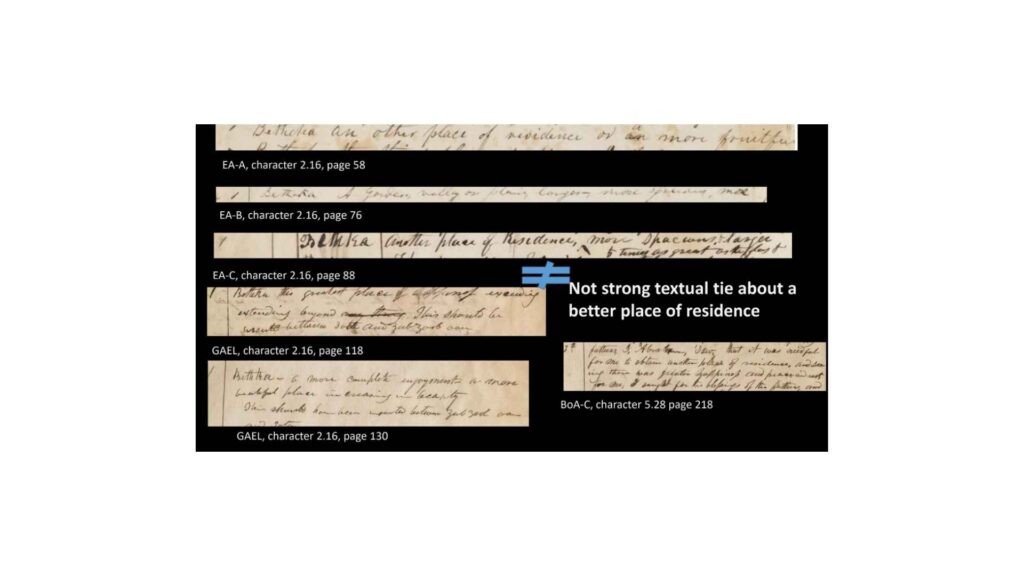

You get one character who says a woman is married or unmarried, signifies all or any woman and another that says underwater and another that says the eye, or to see or sight, or sometimes me, myself. And then when you see all the characters put together it says “Egypt.The land first seen, by a woman, under water.” And you can see that character here where it says “The land of Egypt being first discovered by a woman, who was the daughter of Ham and the daughter of Zeptah” and so on and so on.

So you can see the character matches are not perfect, but it’s fairly decent there and so this suggests that it goes in reverse order.

Translating Then Creating a Grammar

What you have is a papyrus character that’s all put together, but then when you dissect it, and then they re-put it back together, it gives us this translation. And so that seems to be coming from the papyrus and the translation first and going in reverse order to the alphabet and grammar.

And so that suggests as as we get from this character on the papyrus, that suggests that when we get this little character created here, obviously it doesn’t match so we’re going from papyrus, the character on the left is the Book of Abraham manuscript, the character on the right is the alphabet and grammar. And so it would seem that we’ve gone from the papyrus to the Book of Abraham manuscript, and then to the alphabet and grammar. So that suggests that we’re translating first and then trying to create a grammar afterwards.

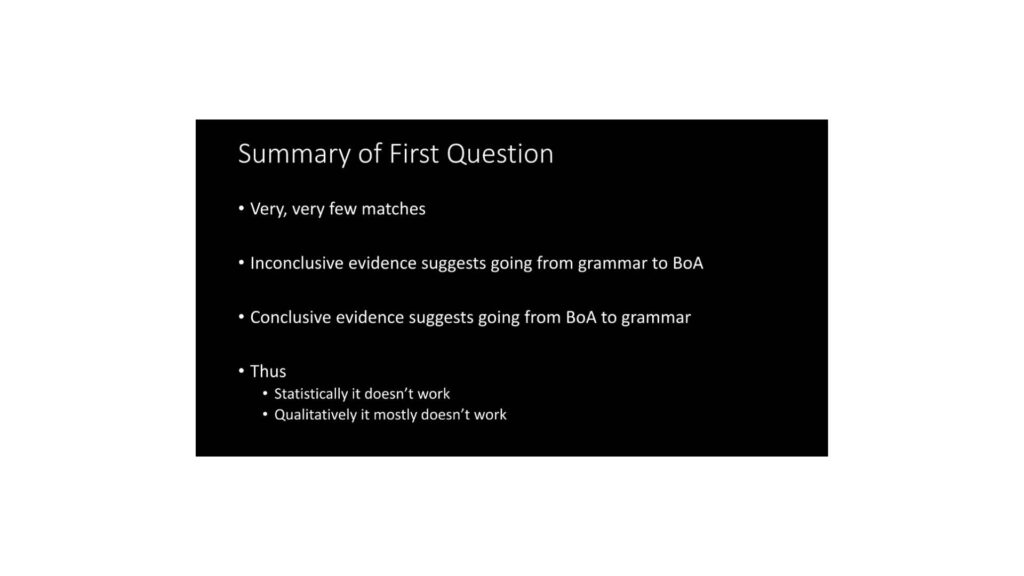

Summary of First Question

So if we’re going to summarize this first question, and we need to hurry here, there are very, very few matches, and inconclusive evidence suggests possibly going from the grammar to the Book of Abraham but more conclusive evidence suggests going from the Book of Abraham to the grammar. Thus statistically, or quantitatively, because there are so few matches, this theory that they’re using the alphabet grammar to translate the characters in the margin, it just doesn’t work, and neither does it qualitatively. It just doesn’t work.

Second Question

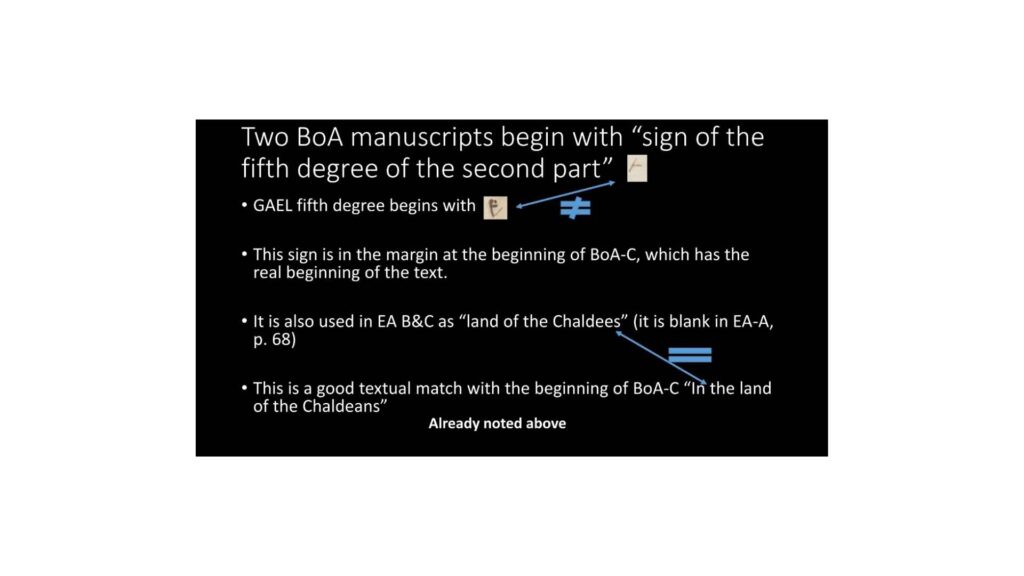

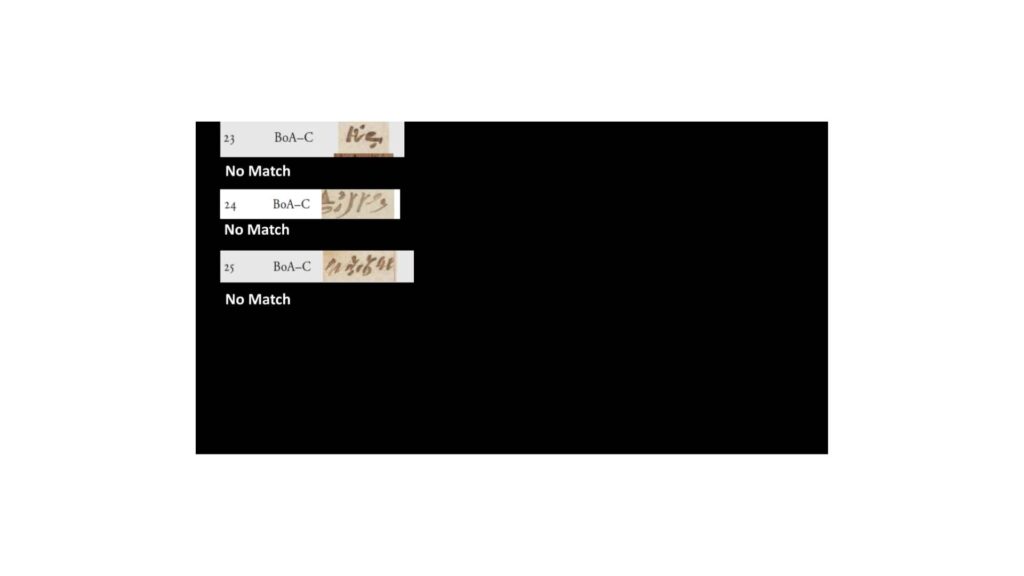

Let’s look at the second question and we can do this one very quickly. How are the characters next to the Book of Abraham text used?

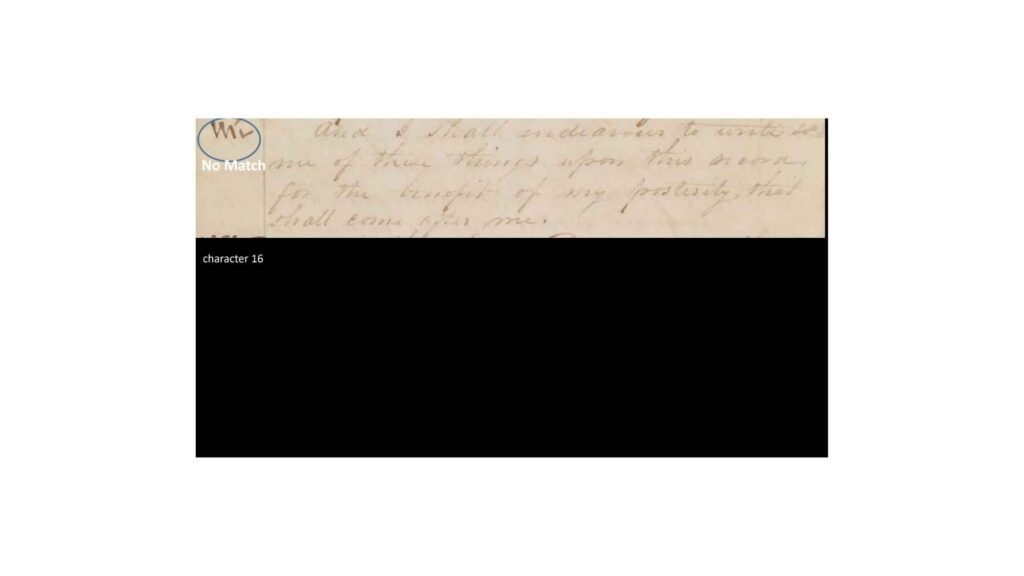

So two Book of Abraham manuscripts begin with this, the “sign of the fifth degree of the second part…” And you can see the character that they have there. In the GAEL, “the fifth degree” looks somewhat similar, but really not. But this is the sign that’s in the margin at the beginning of the Book of Abraham C, which is the only one that has the real beginning of the text.

And it’s also used in the Egyptian alphabets, say “land of the Chaldees.” It’s not in one of the Egyptian alphabets. So that’s a good textual match with a character match there. But those actually, sorry, no, the characters don’t match, but the textual text does match. So the characters don’t match well, but the text does match, and that’s already something that’s a character we looked at earlier.

Summary of Second Question

Let me then summarize this for you, okay?

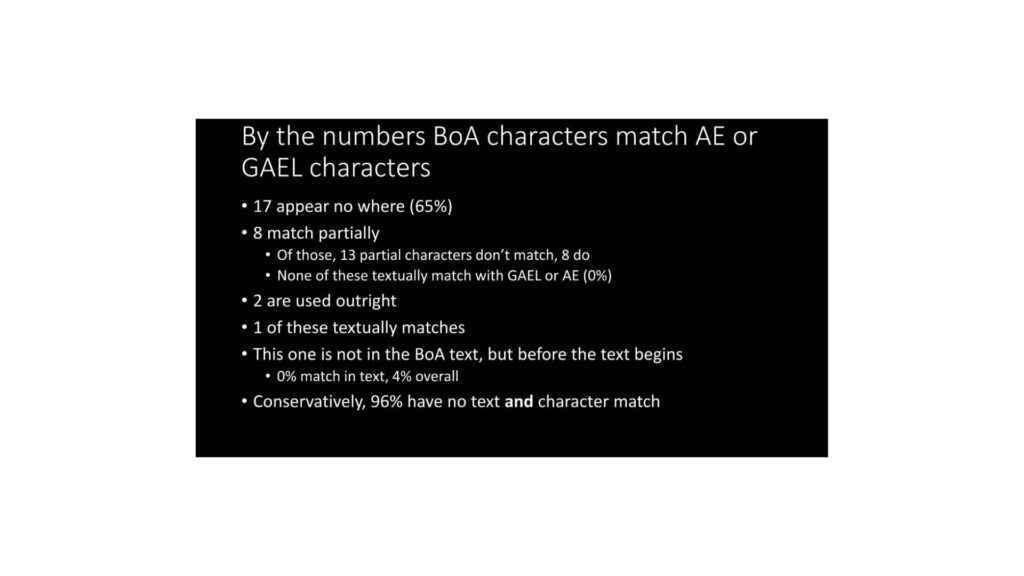

Seventeen, or 65% of the characters in the Book of Abraham manuscripts don’t appear anywhere at all in the alphabets and grammar and so on. So 65 percent of them appear nowhere. Eight have partial matches. Of those, 13 partial characters don’t match, but eight do. None of those textually match, so there’s a zero percent textual match. Two characters are used outright, and one of those has a textual match, but that’s not in the Book of Abraham text, but it’s in the margins before the text begins.

Again, we have a zero percent match in the text, but, four percent overall, meaning conservatively we can say that 96 of the characters do not have a text and character match, right? So 96 percent of the time, the characters in the margins of the Book of Abraham translation have no match at all in the alphabet and grammar.

98%

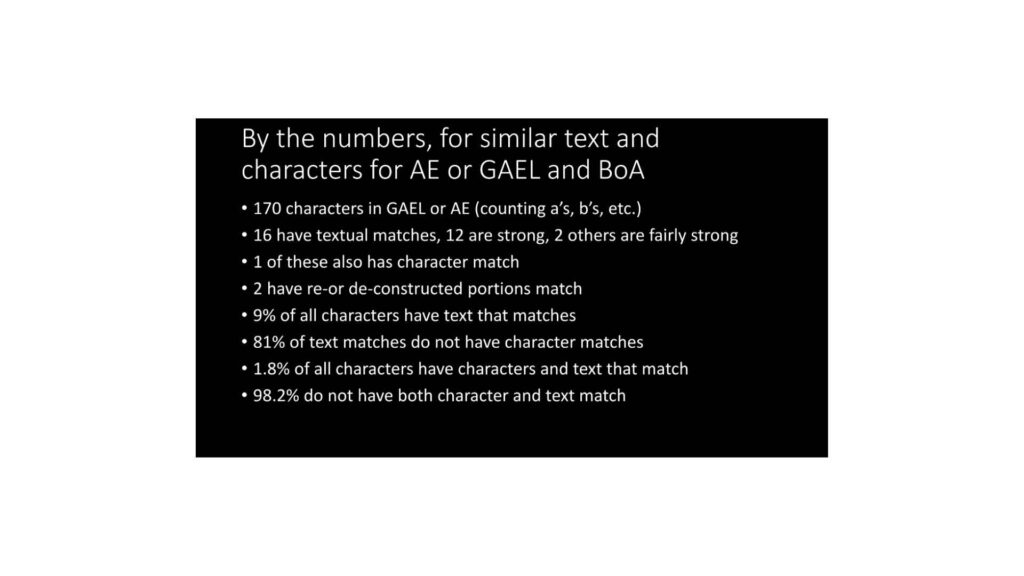

By the numbers, if we’re going to look at this, 170 characters, if we count all the different things that are in the GAEL or AE, 16 have textual matches, 12 are strong, two others are fairly strong. One of these also has a character match, and two, when we re-or de-construct them, have portions that match. So what we end up with is 81% of the text does not have a character match, but only 1.8% of all characters have characters and text that match. Which means that 98% of the time they don’t match, right? Ninety-eight percent of the time there’s no match whatsoever.

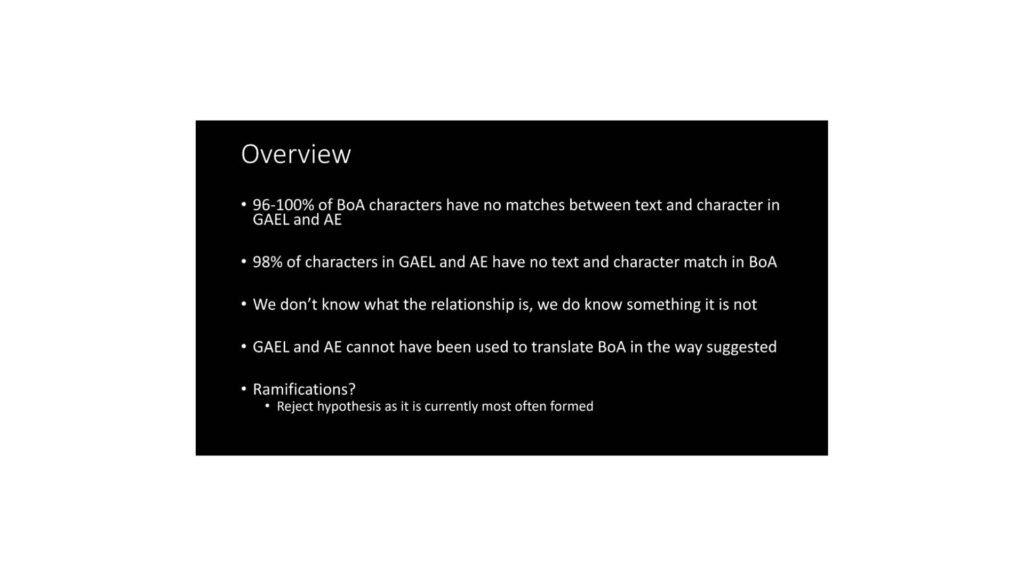

Conclusion

What that tells us is that we don’t know what the relationship is, but we do know what it’s not. It can’t be the way that it’s been suggested that they use the grammar and alphabet to translate those characters in the Book of Abraham manuscripts because either in 96 or 98 percent of the time, that doesn’t work, and those are fairly high numbers, right?

What are the ramifications? Well, it looks like the way that we typically form that part of the hypothesis, we have to reject it.

So to summarize with the logic test, we reject that the grammar and alphabet was used as a tool of translation. With the historical test, well, we suggest we reject it. It’s not a strong rejection. The historical test, it’s a strong rejection. With the document test, at least the way it’s most often formulated, we have to reject it, which suggests again, we reject the whole hypothesis.

Thank You

So I would conclude that once we’ve turned this assumption into a hypothesis, we have to reject it. That means really we’re best served by moving on. If we want to understand what’s going on with the alphabet and grammar, let’s not keep spending our time on a hypothesis that we now know does not work. Let’s spend our time looking into other possibilities and maybe then we can come to understand them better. Thank you very much.

Audience Q&A

Scott Gordon:

Dr. Muhlstein, that was interesting. So to summarize, your argument is that the argument put forth most frequently by the critics about the alphabet and grammar and the translation Book of Abraham, doesn’t work. Is that correct?

Kerry Muhlestein:

That’s exactly right. And I know the last part is very technical and it’ll be easier to understand when you read it written. So the first parts, I think, are easier to understand and deal with the whole global hypothesis, and the last part only with part of it. But in all cases, it tells us this just doesn’t work. Let’s move on.

Scott Gordon:

Okay. And I have a few questions that people have emailed to me. It says, what do you think of this statement from Joseph Smith in the discourse circa May 1841 where he says, “Everlasting covenant was made between three personages before the organization in the earth and relates to their dispensation of things to men on the earth. These personages according to Abraham’s record are called God the first, the creator; God the second, the Redeemer; God the third, the witness or testator.” That’s from the Joseph Smith papers. This information does not appear in the extant Book of Abraham text nor the GAEL documents. Do you think it’s evidence that more texts in the Book of Abraham were translated beyond what we currently have?

Kerry Muhlestein:

I think it suggests that, and I love this question. I’ll tell you why for a couple of reasons. But one, I think it suggests that again, I don’t know that we can say for sure, but it certainly suggests that. And there are a number of other things that we’ll find Joseph Smith referring to with the records of Abraham that aren’t in the text we now have. Which suggests that he has translated it. It’s possible that he’s just looking at it, had enough revelation to know more of what’s in there, but I think it suggests he’s translated. But I’ll tell you a reason why I love this, and it’s because I think that this question, too often we get distracted by all the little details I just went through. Now we need to go through those details and it’s important. Sometimes it’s boring, but we need to go through those details and we need to look at these periphery issues. But sometimes these periphery issues, how did he translate, when did he translate? Sometimes we get so carried away with those things that we forget to look at the text and the teachings of the Book of Abraham.

The Book of Abraham clearly teaches about the covenant. And that statement, I think, is powerful in helping us understand the covenant and so is the Book of Abraham. And so what I hope that indicates is that this person is not only looking at the peripheral issues but wanting to find out what can we learn doctrinally from the Book of Abraham and what Joseph Smith learns by translating the Book of Abraham. And that’s where the real power is. If you want to really test the Book of Abraham, look at the teachings that come from the Book of Abraham.

Scott Gordon:

Okay. How can we better communicate a defense of the translation of the Book of Abraham when the sophisticated arguments can get very complicated but detractors often persuade members effectively with simplistic and superficial arguments?

Kerry Muhlestein:

I think that is so 100 percent true. And as I said, I believe Dr. Gee will be addressing that later. So this is the problem. It’s an unfair game that we let be played because people are willing to be taken advantage of by simplistic statements. It’s actually the same problem we have in politics and a whole bunch of other things right now. Everyone wants a 30-second sound bite, and it’s easy to say somewhat true but seductive things in a 30-second sound bite, and it’s difficult to say actually true and important things in it on complicated matters in a way that’s understandable. And so I hope what we do, and I probably just failed at this, but I hope what we can do is provide both the details and then a summary of those details that is less complicated so that those who want to go back and see if it’s true, can go back and look at the details. But the summary should be clear enough.

So maybe I should say one more time the summary is: Every way we look at testing this hypothesis, it doesn’t work. The grammar and alphabet could not have been used to translate the Book of Abraham, at least according to every way I can conceive of testing it. And so let’s try and get those simplified summaries out there as long as they’re backed up by the actual complicated truth.

Scott Gordon:

Thank you. What are some of the other possibilities for understanding the nature of the GAEL if it were not used for the translation of the Book of Abraham?

Kerry Muhlestein:

That’s a great question, and that’s where I think we’ve spent so much of our time barking up the wrong tree. I hope we can come to understand that better as we try and bark up different trees. Some people have tried. William Shriver and others have done that, and I hope that we will continue to try and understand it. I would say right now, my best guess is that once they had a translation, they were trying to recreate a grammar, but it seems to me like even that is too simplistic. That there’s something more going on, and I don’t profess to understand what it is, but I hope that we’ll put our energy into something more worthwhile at this point.

Scott Gordon:

Okay, another question. A person wrote, Are you saying there is no relationship between the AEP and the glyphs on the recovered papyri?

Kerry Muhlestein:

No, I don’t think that there’s no relationship. I’m saying, and I think, so again, I can see I didn’t explain this well enough, but at least one of my bullet points in there says we don’t know what the relationship is. We just know what it’s not. So what it’s not is a tool of translation. There is some kind of relationship. I don’t profess to know what that relationship is.

Scott Gordon:

Excellent. And then who do you think put the characters in the margin? Phelps, Joseph, others who tried to learn Egyptian?

Kerry Muhlestein:

That’s a great question, and you know, it’s particularly difficult with something like that to tell because typically we’ll turn to handwriting to be able to tell that. But we’re looking at handwriting of people who are using a script that they don’t ever write in and not copying it particularly well anyway. So it’s pretty hard to use that as a handwriting analysis. If I had to just guess, I would guess that it’s largely Phelps. In the end, we could say, well, whoever’s handwriting is in the right-hand side with the text probably did the characters, but that’s an assumption. I don’t know that it’s a safe assumption. I really don’t know. I wish I understood what those are doing. In some cases, you can tell they’re written after because they overwrite, but I think we have no clue what they’re doing with those characters. And everyone who has professed to know what they are and who says they know what they are is not being fully honest with you because it’s too complex to be able to say that.

Scott Gordon:

Okay, the next question is, what do you believe? Is it the missing scroll theory? Is it the catalyst theory and why?

Kerry Muhlestein:

It depends on what day you ask me and what hour of the day you ask me. To be honest, I don’t think we have a model that can account for all of the evidence that we currently have. And so it’s difficult to know what theory to go with. And I actually find that comforting and to be expected. It was frustrating for a while and then I thought about it. I thought, well, if we are dealing with revelation coming from the Divine, I don’t know why I would expect to be able to easily fully understand the process or the little bits of evidence that we have. And so to me, the fact that we can’t find a model that works, is a testament that there’s something beyond our normal abilities at work here. And I believe that’s God.

Scott Gordon:

I really like that answer. When people talk about how Joseph Smith didn’t translate something correctly, my thought is always well, since you’re such an expert on the Divine, how should he have done it?

Kerry Muhlestein:

Yeah.

Scott Gordon:

And there’s a lot of things we don’t understand and don’t know. With that, I know it’s a complicated subject and yet you laid it out very clearly for us. We really appreciate that and we appreciate your time and thank you very much.

Kerry Muhlestein:

Thank you.

Endnotes & Summary

Jeffrey’s talk, What Do We Treasure?, explores how different worldviews shape our understanding of the gospel and influence what we see as the “good life.” He identifies four primary worldviews—the Expressive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, and Redemptive Gospel—each defining success and fulfillment in different ways. While Expressive Gospel prioritizes self-expression, Prosperity Gospel equates righteousness with financial success, and Therapeutic Gospel emphasizes emotional well-being, the Redemptive Gospel teaches that true success is found in reconciliation with God. By examining these perspectives, Jeffrey warns that misplaced values can lead people to misunderstand the gospel’s true purpose.

The talk highlights how Gospel Counterfeits arise when cultural influences subtly redefine gospel vocabulary and shift the focus away from Christ. He provides examples of how phrases like non-judgmental love and authenticity take on different meanings depending on the worldview, leading to confusion and potential spiritual drift. Many individuals, even those originally converted to the Redemptive Gospel, gradually adopt cultural values while still using gospel language. This process results in a faith that, while still appearing religious, may no longer align with the teachings of Jesus Christ.

Jeffrey concludes by emphasizing the need for spiritual discernment and doctrinal clarity. While Gospel Counterfeits persist because they offer comfort, validation, or worldly success, the Redemptive Gospel calls for transformation through Christ. Faithful discipleship requires prioritizing God’s values over societal expectations, measuring spiritual success by personal sanctification rather than external achievements. By recognizing and rejecting distorted versions of the gospel, believers can ensure their faith remains rooted in eternal truths rather than cultural trends.

All Talks by This Speaker

coming soon…

Talk Details

- Date Presented: August 9, 2024

- Duration: 26:31 minutes

- Event/Conference: 2024 FAIR Annual Conference

- Topics Covered: Redemptive Gospel, Prosperity Gospel, Therapeutic Gospel, Expressive Gospel, gospel counterfeits, authenticity, covenant-keeping, LDS worldview, personal fulfillment, character transformation, reconciliation with God, faith crises, gospel vocabulary, Maslow’s hierarchy, LDS apologetics

Common Concerns Addressed

Joseph Smith used the GAEL to translate the Book of Abraham.

Comprehensive tests—logical, historical, and textual—undermine this assumption.

Joseph Smith created the Book of Abraham to retroactively justify his ideas.

Historical evidence suggests Joseph taught principles from the Book of Abraham before 1842, supporting earlier revelation.

Apologetic Focus

Revelation as a legitimate method of translation

Importance of recognizing scholarly bias

Methodological rigor in apologetic research

Explore Further

coming soon…

Share this article