FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

| [[../Book of Mormon Concerns & Questions|Book of Mormon Concerns & Questions]] | A FAIR Analysis of: [[../|Letter to a CES Director]] A work by author: Jeremy Runnells

|

[[../First Vision Concerns & Questions|First Vision Concerns & Questions]] |

Unlike the story I’ve been taught in Sunday Schools, Priesthood, General Conferences, Seminary, EFY, Ensigns, Church history tour, Missionary Training Center, and BYU…Joseph Smith used a rock in a hat for translating the Book of Mormon."

Joseph Smith used both the Nephite Interpreters and his own seer stone during the translation process, yet we only hear of the "Urim and Thummim" being used for this purpose.

Emma Smith Bidamon described Joseph's use of several stones during translation to Emma Pilgrim on 27 March 1870 (original spelling retained):

Now the first that my <husband> translated, [the book] was translated by use of the Urim, and Thummim, and that was the part that Martin Harris lost, after that he used a small stone, not exactly, black, but was rather a dark color.”[1]

The Lord provided a set of seer stones (which were formerly used by Nephite prophets) along with the plates. The term Nephite interpreters can alternatively refer to the stones themselves or the stones in conjunction with their associated paraphernalia (holding rim and breastplate). Some time after the translation, early saints noticed similarities with the seer stones and related paraphernalia used by High Priests in the Old Testament and began to use the term Urim and Thummim interchangeably with the Nephite interpreters and Joseph's other seer stones as well. The now popular use of the term Urim and Thummim has unfortunately obscured the fact that all such devices belong in the same class of consecrated revelatory aids and that more than one were used in the translation.

The Nephite interpreters were intended to assist Joseph in the initial translation process, yet the manner in which they were employed was never explained in detail. The fact that the Nephite interpreters were set in rims resembling a pair of spectacles has led some to believe that they may have been worn like a pair of glasses, with Joseph viewing the characters on the plates through them. This, however, is merely speculation that doesn't take into account that Joseph soon disassembled the fixture, the spacing between seer stones being too wide for his eyes. The accompanying breastplate also appeared to have been used by a larger man. Like its biblical counterpart (the High Priest's breastplate contained 12 gems that symbolized him acting as a mediator between God and Israel), the Nephite breastplate was apparently non-essential to the revelatory process.

Martin Harris states that Joseph used the Nephite interpreters and then later switched to using the seer stone "for convenience." [2] In fact, Elder Nelson refers to the use of the seer stone in his 1993 talk:

The details of this miraculous method of translation are still not fully known. Yet we do have a few precious insights. David Whitmer wrote:

“Joseph Smith would put the seer stone into a hat, and put his face in the hat, drawing it closely around his face to exclude the light; and in the darkness the spiritual light would shine. A piece of something resembling parchment would appear, and on that appeared the writing. One character at a time would appear, and under it was the interpretation in English. Brother Joseph would read off the English to Oliver Cowdery, who was his principal scribe, and when it was written down and repeated to Brother Joseph to see if it was correct, then it would disappear, and another character with the interpretation would appear. Thus the Book of Mormon was translated by the gift and power of God, and not by any power of man.” (David Whitmer, An Address to All Believers in Christ, Richmond, Mo.: n.p., 1887, p. 12.) [3]

W.W. Phelps wrote the following in the January 1833 edition of The Evening and The Morning Star:

The book of Mormon, as a revelation from God, possesses some advantage over the old scripture: it has not been tinctured by the wisdom of man, with here and there an Italic word to supply deficiencies.-It was translated by the gift and power of God, by an unlearned man, through the aid of a pair of Interpreters, or spectacles-(known, perhaps, in ancient days as Teraphim, or Urim and Thummim) and while it unfolds the history of the first inhabitants that settled this continent, it, at the same time, brings a oneness to scripture, like the days of the apostles; and opens and explains the prophecies, that a child may understand the meaning of many of them; and shows how the Lord will gather his saints, even the children of Israel, that have been scattered over the face of the earth, more than two thousand years, in these last days, to the place of the name of the Lord of hosts, the mount Zion. [4]

It appears that the seer stone was also referred to as the "Urim and Thummim" after 1833, indicating that the name could be assigned to any device that was used for the purpose of translation.[5]

The rock in the hat is confirmed "in an obscure 1992 talk given by Elder Russell M. Nelson."

Gospel Topics on LDS.org:

These two instruments—the interpreters and the seer stone—were apparently interchangeable and worked in much the same way such that, in the course of time, Joseph Smith and his associates often used the term “Urim and Thummim” to refer to the single stone as well as the interpreters. In ancient times, Israelite priests used the Urim and Thummim to assist in receiving divine communications. Although commentators differ on the nature of the instrument, several ancient sources state that the instrument involved stones that lit up or were divinely illumin[at]ed. Latter-day Saints later understood the term “Urim and Thummim” to refer exclusively to the interpreters. Joseph Smith and others, however, seem to have understood the term more as a descriptive category of instruments for obtaining divine revelations and less as the name of a specific instrument. [6]

Gerrit Dirkmaat (Church History Department - January 2013 Ensign):

Those who believed that Joseph Smith’s revelations contained the voice of the Lord speaking to them also accepted the miraculous ways in which the revelations were received. Some of the Prophet Joseph’s earliest revelations came through the same means by which he translated the Book of Mormon from the gold plates. In the stone box containing the gold plates, Joseph found what Book of Mormon prophets referred to as “interpreters,” or a “stone, which shall shine forth in darkness unto light” (Alma 37:23–24). He described the instrument as “spectacles” and referred to it using an Old Testament term, Urim and Thummim (see Exodus 28:30).2

He also sometimes applied the term to other stones he possessed, called “seer stones” because they aided him in receiving revelations as a seer. The Prophet received some early revelations through the use of these seer stones. For example, shortly after Oliver Cowdery came to serve as a scribe for Joseph Smith as he translated the plates, Oliver and Joseph debated the meaning of a biblical passage and sought an answer through revelation. Joseph explained: “A difference of opinion arising between us about the account of John the Apostle … whether he died, or whether he continued; we mutually agreed to settle it by the Urim and Thummim.”3 In response, Joseph Smith received the revelation now known as section 7 of the Doctrine and Covenants, which informed them that Jesus had told the Apostle John, “Thou shalt tarry until I come in my glory” (D&C 7:3).

Records indicate that soon after the founding of the Church in 1830, the Prophet stopped using the seer stones as a regular means of receiving revelations. Instead, he dictated the revelations after inquiring of the Lord without employing an external instrument. One of his scribes explained that process: “The scribe seats himself at a desk or table, with pen, ink, and paper. The subject of inquiry being understood, the Prophet and Revelator inquires of God. He spiritually sees, hears, and feels, and then speaks as he is moved upon by the Holy Ghost.”[7]

In other words, he used the same “Ouija Board” that he used in his days treasure hunting where he would put in a rock – or a peep stone – in his hat and put his face in the hat to tell his customers the location of buried treasure

"Book of Mormon Translation," Gospel Topics on LDS.org (2013):

Joseph Smith and his scribes wrote of two instruments used in translating the Book of Mormon. According to witnesses of the translation, when Joseph looked into the instruments, the words of scripture appeared in English. One instrument, called in the Book of Mormon the “interpreters,” is better known to Latter-day Saints today as the “Urim and Thummim.” ....

The other instrument, which Joseph Smith discovered in the ground years before he retrieved the gold plates, was a small oval stone, or “seer stone.” As a young man during the 1820s, Joseph Smith, like others in his day, used a seer stone to look for lost objects and buried treasure. As Joseph grew to understand his prophetic calling, he learned that he could use this stone for the higher purpose of translating scripture.[8]

Joseph was given a set of Nephite interpreters along with the gold plates from which the Book of Mormon was produced. In addition, Joseph already possessed and utilized several seer stones. Although Joseph began translating the Book of Mormon using the Nephite interpreters, he later switched to using one of his seer stones to complete the translation. Critics (typically those who reject Mormonism but still believe in God) reject the idea that God would approve the use of an instrument for translation that had previously been used for "money digging."

The conclusion that Joseph used a "magical" or "occult" stone to assist in the translation of the Book of Mormon is entirely dependent upon one's own preconception that the use of such an instrument would not be acceptable by God. Believers, on the other hand, ought not to take issue with a distinction between one set of seer stones versus another. As Brant Gardner notes: "Regardless of the perspective from which we tell the story, the essential fact of the translation is unchanged. How was the Book of Mormon translated? As Joseph continually insisted, the only real answer, from any perspective, is that it was translated by the gift and power of God." [9]

"Behold, I am God and have spoken it; these commandments are of me, and were given unto my servants in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding."

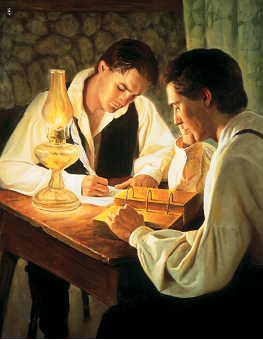

The above nine images are copyrighted by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. [images of Joseph looking at the plates in the open] Book of Mormon translation as it actually happened: [images of Joseph looking into a hat] Why is the Church not being honest and transparent to its members about how Joseph Smith really translated the Book of Mormon? How am I supposed to be okay with this deception?

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[10]

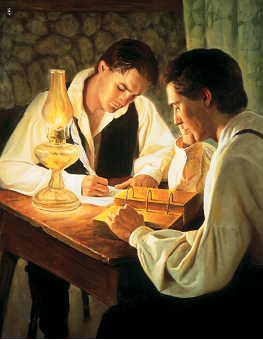

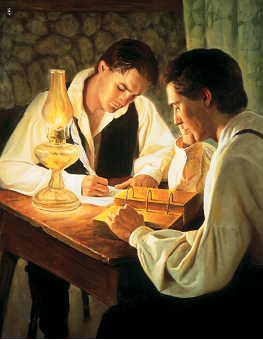

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [12] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[13]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[14] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[15]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[16] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[17] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[18] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[19] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[20] and the FARMS Review (1994).[21] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[22]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[23]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[24]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[25]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[26] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[27]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

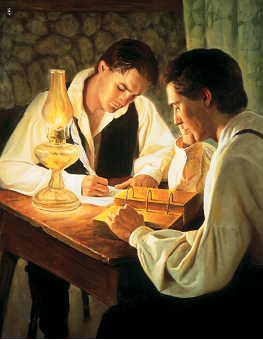

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

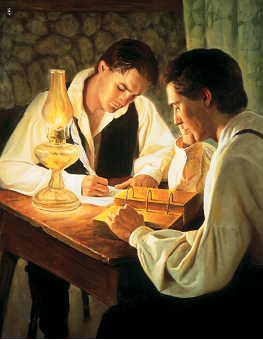

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

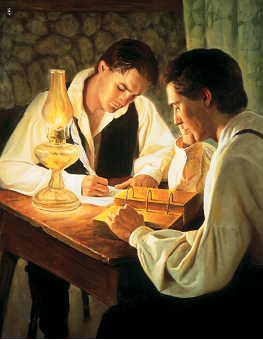

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

One of the strangest attacks on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an assault on the Church's art. Now and again, one hears criticism about the representational images which the Church uses in lesson manuals and magazines to illustrate some of the foundational events of Church history.[1]

A common complaint is that Church materials usually show Joseph translating the Book of Mormon by looking at the golden plates, such as in the photo shown here.

Here critics charge a clear case of duplicity—Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith are shown translating the Book of Mormon.

But as the critics point out, there are potential historical errors in this image:

The reality is that the translation process, for the most part, is represented by this image:

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

It is claimed by some that the Church knowingly "lies" or distorts the historical record in its artwork in order to whitewash the past, or for propaganda purposes. [3] For example, some Church sanctioned artwork shows Joseph and Oliver sitting at a table while translating with the plate in the open between them. Daniel C. Peterson provides some examples of how Church art often does not reflect reality, and how this is not evidence of deliberate lying or distortion on the part of the Church:

Look at this famous picture....Now that’s Samuel the Lamanite on a Nephite wall. Are any walls like that described in the Book of Mormon? No. You have these simple things, and they’re considered quite a technical innovation at the time of Moroni, where he digs a trench, piles the mud up, puts a palisade of logs along the top. That’s it. They’re pretty low tech. There’s nothing like this. This is Cuzco or something. But this is hundreds of years after the Book of Mormon and probably nowhere near the Book of Mormon area, and, you know, and you’ve heard me say it before, after Samuel jumps off this Nephite wall you never hear about him again. The obvious reason is....he’s dead. He couldn’t survive that jump. But again, do you draw your understanding of the Book of Mormon from that image? Or, do you draw it from what the book actually says?[4]

The implication is that the Church's artistic department and/or artists are merely tools in a propaganda campaign meant to subtly and quietly obscure Church history. The suggestion is that the Church trying to "hide" how Joseph really translated the plates.

On the contrary, the manner of the translation is described repeatedly, for example, in the Church's official magazine for English-speaking adults, the Ensign. Richard Lloyd Anderson discussed the "stone in the hat" matter in 1977,[5] and Elder Russell M. Nelson quoted David Whitmer's account to new mission presidents in 1992.[6]

The details of the translation are not certain, and the witnesses do not all agree in every particular. However, Joseph's seer stone in the hat was also discussed by, among others: B.H. Roberts in his New Witnesses for God (1895)[7] and returns somewhat to the matter in Comprehensive History of the Church (1912).[8] Other Church sources to discuss this include The Improvement Era (1939),[9] BYU Studies (1984, 1990)[10] the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (1993),[11] and the FARMS Review (1994).[12] LDS authors Joseph Fielding McConkie and Craig J. Ostler also mentioned the matter in 2000.[13]

Elder Neal A. Maxwell went so far as to use Joseph's hat as a parable; this is hardly the act of someone trying to "hide the truth":

Jacob censured the "stiffnecked" Jews for "looking beyond the mark" (Jacob 4꞉14). We are looking beyond the mark today, for example, if we are more interested in the physical dimensions of the cross than in what Jesus achieved thereon; or when we neglect Alma's words on faith because we are too fascinated by the light-shielding hat reportedly used by Joseph Smith during some of the translating of the Book of Mormon. To neglect substance while focusing on process is another form of unsubmissively looking beyond the mark.[14]

Those who criticize the Church based on its artwork should perhaps take Elder Maxwell's caution to heart.

From Anthony Sweat’s essay “The Gift and Power of Art”:

When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the draw- ings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [the Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately) but I thought just maybe I should still do it [the image of Joseph translating using the hat]. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[15]

Anthony Sweat explains more about the history of artistic depictions of the Book of Mormon translation in this presentation given at the 2020 FAIR Conference

Why, then, does the art not match details which have been repeatedly spelled out in LDS publications?

The simplest answer may be that artists simply don't always get such matters right. The critics' caricature to the contrary, not every aspect of such things is "correlated." Robert J. Matthews of BYU was interviewed by the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, and described the difficulties in getting art "right":

JBMS: Do you think there are things that artists could do in portraying the Book of Mormon?

RJM: Possibly. To me it would be particularly helpful if they could illustrate what scholars have done. When I was on the Correlation Committee [of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], there were groups producing scripture films. They would send to us for approval the text of the words that were to be spoken. We would read the text and decide whether we liked it or not. They would never send us the artwork for clearance. But when you see the artwork, that makes all the difference in the world. It was always too late then. I decided at that point that it is so difficult to create a motion picture, or any illustration, and not convey more than should be conveyed. If you paint a man or woman, they have to have clothes on. And the minute you paint that clothing, you have said something either right or wrong. It would be a marvelous help if there were artists who could illustrate things that researchers and archaeologists had discovered…

I think people get the main thrust. But sometimes there are things that shouldn't be in pictures because we don't know how to accurately depict them…I think that unwittingly we might make mistakes if we illustrate children's materials based only on the text of the Book of Mormon.[16]

Modern audiences—especially those looking to find fault—have, in a sense, been spoiled by photography. We are accustomed to having images describe how things "really" were. We would be outraged if someone doctored a photo to change its content. This largely unconscious tendency may lead us to expect too much of artists, whose gifts and talents may lie in areas unrelated to textual criticism and the fine details of Church history.

Even this does not tell the whole story. "Every artist," said Henry Ward Beecher, "dips his brush in his own soul, and paints his own nature into his pictures."[17] This is perhaps nowhere more true than in religious art, where the goal is not so much to convey facts or historical detail, as it is to convey a religious message and sentiment. A picture often is worth a thousand words, and artists often seek to have their audience identify personally with the subject. The goal of religious art is not to alienate the viewer, but to draw him or her in.

The critics would benefit from even a cursory tour through religious art. Let us consider, for example, one of the most well-known stories in Christendom: the Nativity of Christ. How have religious artists portrayed this scene?

As the director of Catholic schools in Yaounde, Cameroon argues:

It is urgent and necessary for us to proclaim and to express the message, the life and the whole person of Jesus-Christ in an African artistic language…Many people of different cultures have done it before us and will do it in the future, without betraying the historical Christ, from whom all authentic Christianity arises. We must not restrict ourselves to the historical and cultural forms of a particular people or period.[18]

The goal of religious art is primarily to convey a message. It uses the historical reality of religious events as a means, not an end.

Religious art—in all traditions—is intended, above all, to draw the worshipper into a separate world, where mundane things and events become charged with eternal import. Some dictated words or a baby in a stable become more real, more vital when they are connected recognizably to one's own world, time, and place.

This cannot happen, however, if the image's novelty provides too much of a challenge to the viewer's culture or expectations. Thus, the presentation of a more accurate view of the translation using either the Nephite interpreters (sometimes referred to as "spectacles") or the stone and the hat, automatically raises feelings among people in 21st Century culture that the translation process was strange. This type of activity is viewed with much less approval in our modern culture.

Key sources |

|

Wiki links |

|

FAIR links |

|

Navigators |

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now