FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

FAIR Answers—back to home page

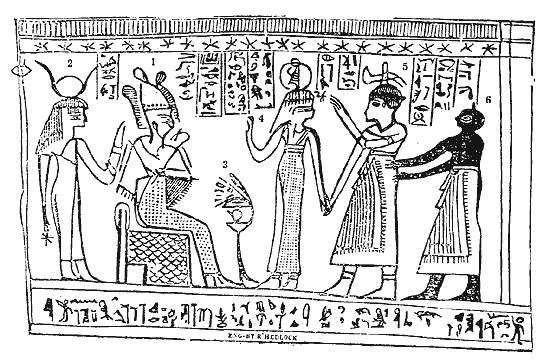

Figure 2, identified by Joseph as "King Pharaoh" and figure 4, identified by Joseph as "Prince of Pharaoh" are obviously drawn as female figures. The fact that they are drawn as females is so obvious, in fact, that critics take this as evidence of Joseph's lack of ability to interpret the facsimiles in any fashion whatsoever. Since the figures would obviously have appeared as females even to Joseph's eye, why then are they interpreted as two of the primary male figures?

Regarding the identification of these figures, John Gee notes,

Facsimile 3 has received the least attention. The principal complaint raised by the critics has been regarding the female attire worn by figures 2 and 4, who are identified as male royalty. It has been documented, however, that on certain occasions, for certain ritual purposes, some Egyptian men dressed up as women. [1]

The identification of these obvious female figures as male does suggest that Joseph was using the existing image to illustrate a concept.

Robert K. Ritner, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Chicago, states that "Smith’s hopeless translation also turns the goddess Maat into a male prince, the papyrus owner into a waiter, and the black jackal Anubis into a Negro slave."[2]

Larry E. Morris notes the following in response to criticism leveled by Professor Ritner at the Book of Abraham,

Furthermore, Ritner does not inform his readers that certain elements of the Book of Abraham also appear in ancient or medieval texts. Take, for example, Facsimile 3, which depicts, as Ritner puts it, "enthroned Abraham lecturing the male Pharaoh (actually enthroned Osiris with the female Isis)." [3] In what Ritner describes as nonsense, Joseph Smith claimed that Abraham is "sitting upon Pharoah's throne . . . reasoning upon the principles of Astronomy" (Facsimile 3, explanation).

Clearly, Joseph Smith's interpretation did not come from Genesis (where there is no discussion of Abraham doing such a thing). From Ritner's point of view, therefore, this must qualify as one of Joseph's "uninspired fantasies." But going a layer deeper reveals interesting complexities. A number of ancient texts, for example, state that Abraham taught astronomy to the Egyptians. Citing the Jewish writer Artapanus (who lived prior to the first century BC), a fourth-century bishop of Caesarea, Eusebius, states: "They were called Hebrews after Abraham. [Artapanus] says that the latter came to Egypt with all his household to the Egyptian king Pharethothes, and taught him astrology, that he remained there twenty years and then departed again for the regions of Syria."22

As for Abraham sitting on a king's throne—another detail not mentioned in Genesis—note this example from Qisas al-Anbiya' (Stories of the Prophets), an Islamic text compiled in AD 1310: "The chamberlain brought Abraham to the king. The king looked at Abraham; he was good looking and handsome. The king honoured Abraham and seated him at his side."23 [4]

Morris concludes,

Ritner may counter that such parallels do not establish the authenticity of the Book of Abraham. That is true, but certainly they deserve some mention. At the very least, these parallels show that "all of this nonsense" is not really an appropriate description of Joseph Smith's interpretation. Fairness demands that Ritner, in his dismissal of the content of the Book of Abraham, at least mention similarities between it and other texts about Abraham and point readers to other sources of information. [5]

Notes

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now