August 2017

The operator says “Calm down. I can help. First, let’s make sure he’s dead.” There is a silence, and then a shot is heard. Back on the phone, the guy says, “OK, now what?”

I’m a firm believer that truth is truth regardless of the source. As Joseph Smith said, “One of the grand fundamental principles of Mormonism is to receive truth, let it come from whence it may.”[i] While no endeavor in which humans are engaged can be infallible, I find that “science” (as an umbrella term for multiple disciples) typically moves forward in our understanding of the cosmos and how our planet and life evolved to its current state. Scientific discoveries shed increasing light on how we humans fit into this world.

While scientific findings have, at times, contributed to the faltering of testimonies, I personally find that science illuminates belief in positive ways and sheds light on obscure or misunderstood areas of religious understanding

My interest in these and other scientifically-related topics, and how they can be understood from within a framework of belief, compelled me—a couple of years ago—to begin a book-length project addressing this general theme and how Latter-day Saints can embrace, rather than distress over scientific discoveries and their sometimes apparent clash with religious beliefs.

While engaged in my project (which probably has another year of work to go before it’s finished) I’ve taken a particular fascination with Cognitive Science and related fields such as psychology and neuroscience. In my book Shaken Faith Syndrome, I spent some time discussing cognitive dissonance—or thought disharmony—and how we humans typically react and respond to informational threats that challenge our religious beliefs. My continued studies in the cognitive sciences, highlighted the fact that there are interesting and important convergences between how we understand and embrace or reject scientific precepts, and how the recognition of our cognitive limitations can illuminate our understanding about the gospel or the history of how the gospel has been received.

Cognitive studies have shed some interesting light on how and why people often do the things they do, think the things the thing, or react in the ways they react. The joke about the guy shooting his hunting buddy is a good example of how one’s mind might get mixed up. It’s easy for our minds to get mixed up—in fact they get mixed up far more often than we might recognize—and they get mixed up because that’s simply a byproduct of our limited minds.

Sometime in the 1950s my grandfather, like many Americans in his day, bought his first television. The images, of course, were in black and white. Then, in the early 1960s color TVs began appearing in the market. My grandfather wanted a color TV, but didn’t want to spend the money replacing his properly working set, so he continued watching his shows in black and white. One day a door-to-door salesman claimed to have a product that would attach to the front of his black and white TV and convert it to color. The cost was low, so my grandfather bought the product. The contraption consisted of a frame with a transparent acetate filter that was affixed to the front of the television. The filter was divided into the three horizontal bands of color. The top was blue, the middle was pinkish, and the bottom was green. Supposedly the top band would add color to the sky, the middle to skin tones, and the bottom to images of grass on the TV screen. Needless to say, my grandfather wasn’t happy with his purchase.

My grandfather’s inability to watch proper color TV wasn’t because color shows weren’t being broadcast, the problem was that his TV was of the older variety—it didn’t have the technological advances to render and display the color images being broadcast.

Every human being has limits—both physical and cognitive limits. No matter how fit you are, you cannot run 100 mph. Even if you can dunk a basketball, you cannot (unassisted) jump 40 feet into the air. Even if you are the most brilliant person alive, have a photographic memory, and have read every book you’ve ever touched, you cannot know the answers to everything, or solve every problem. Our cognitive weaknesses include ignorance, misunderstanding, inflexibility, bias, short-sightedness, and even stupidity.

As neuroscientists study the brain and psychologists study human behavior, it becomes increasingly apparent that we are masters at making assumptions. While we are certainly capable of deep thought, analyzing data, and weighing evidence, most of the time our brains need to make snaps decisions in order to navigate the world. We typically don’t have the time to think everything through on every decision we make. Much of our lives are set to autopilot with our actions becoming almost mechanical. As with a modern aircraft autopilot systems, in order for the brain to make these nearly mechanical snap decisions it must rely on programs or templates that guide the decisions. As we encounter a wide variety of things and circumstances in our everyday lives, our brains look for patterns to which it can assign the incoming information. As agnostic researcher Dr. Michael Shermer explains,

The brain is a belief engine. From sensory data flowing in through the senses the brain naturally begins to look for and find patterns, and then infuses those patterns with meaning. The first process I call patternicity: the tendency to find meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless data. The second process I call agenticity: the tendency to infuse patterns with meaning, intention, and agency. We can’t help it. Our brains evolved to connect the dots of our world into meaningful patterns that explain why things happen. These meaningful patterns become beliefs, and these beliefs shape our understanding of reality.[ii]

Our brains automatically connect the dots—engage in patternicity—when encountering various forms of input. We may, for example, walk through a dark alley and see what appears to be a person standing behind a dumpster. The hair on our neck stands up as our flight or fight responses begin to weight our options. As we draw closer, however, we discover that what we thought was a person is actually an old rolled up carpet that someone set against the wall.

When it comes to visual input, our brains use intrinsic patterns to rapidly correlate fuzzy or unfamiliar objects with things that make sense to cognitive patterns, past memories, expectations, and worldviews. We especially, for example, like faces. Studies indicate that from birth (if not earlier[iii]) human babies are attracted the to the general template of a human face—three dots that represent the two eyes and the mouth. By four to six months old, a baby’s brain can process face recognition faster than the recognition of other objects.[iv] This face-finding process remains active in the normal brain throughout one’s life and is the reason we still see faces in places where we shouldn’t see faces—like in clouds or other random arrangements. This phenomenon is known as pareidolia (or what Shermer calls patternicity).

When it comes to visual input, our brains use intrinsic patterns to rapidly correlate fuzzy or unfamiliar objects with things that make sense to cognitive patterns, past memories, expectations, and worldviews. We especially, for example, like faces. Studies indicate that from birth (if not earlier[iii]) human babies are attracted the to the general template of a human face—three dots that represent the two eyes and the mouth. By four to six months old, a baby’s brain can process face recognition faster than the recognition of other objects.[iv] This face-finding process remains active in the normal brain throughout one’s life and is the reason we still see faces in places where we shouldn’t see faces—like in clouds or other random arrangements. This phenomenon is known as pareidolia (or what Shermer calls patternicity).

This intuitive and inescapable cognitive feature serves as both a benefit and a liability and ultimately comes from our evolutionary heritage. As anthropologist Dr. Stewart Guthrie explains, “it is better for a hiker to mistake a boulder for a bear than to mistake a bear for a boulder.”[v] In other words, generating a false positive—a false pattern even when such a pattern doesn’t actually exist—is better for the survival of the species. Animals which make connections to false patterns are more likely to live and to pass on their genes and pattern-connecting proclivities to their progeny.

Even without an obvious benefit, however, we still can’t help but see parallels in some patterns. As Thomas Gilovich points out, “We do not ‘want’ to see a man in the moon. We do not profit from the illusion. We just see it.”[vi] Pareidolia is associated with intuitive brain assumptions about what we see and what our brains expect to see from our environment and past experiences—in other words, the brain makes assumptions about the visual data coming from our eyes. And we see with our brains, not with our eyes.

Studies suggest that the brain’s process of interpreting data into images is apparently so difficult that it nearly defies the impossible. Harvard Psychologist Steven Pinker calls the process “inverse optics” which basically means to reverse engineer an image—including its shape, texture, size, color, depth, and even distance from our eyes, based on bits of data that somehow manage to collectively assign such details. “Inverse optics,” notes Pinker, “is what engineers call an “ill-posed problem.” It literally has no solution, yet “your brain does it every time you open the refrigerator and pull out a jar. How can this be? The answer is that the brain supplies the missing information, information about the world we evolved in and how it reflects light. If the visual brain ‘assumes’ that it is living in a certain kind of world—an evenly lit world made mostly of rigid parts with smooth, uniformly colored surfaces—it can make good guesses about what is out there.”[vii]

According to Pinker, our brains are programmed (thanks to evolution) with templates wherein the eye-brain combo assembles data to reflect what it assumes it’s supposed to look like. “Since Planet Earth has, more or less, met the even-illumination assumption for eons,” writes Pinker, “natural selection would have done well by building the assumption in.”[viii] The assumptions are still enforced, however, even if we change things up, which results, at times, in illusions.

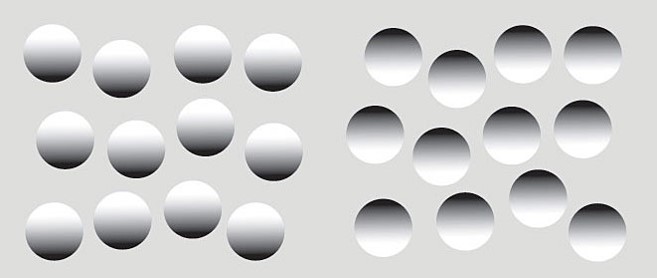

In a Scientific American article,[ix] for instant, researchers show how our brains interpret shapes (even 2-day shapes) based on the assumption of light and shadows. By darkening or lightening specific areas of objects, the brain can be fooled into not only assuming three dimensions with light and shadows, but the brain can almost be forced to assume specific contours.

In this first slide, for instance, the “the disks are ambiguous; you can see either the top row as convex spheres or ‘eggs,’ lit from the left, and the bottom row as cavities—or vice versa.” In this next slide “the disks that are light on the top always look like eggs, and the ones that are light on the bottom are cavities.” As our researchers explain, our visual system “expects light to shine from above.” In this last slide, “you find that you can almost instantly mentally group all the eggs and segregate them from the cavities.”

The coloring of some animals has evolved to leverage this brain-eye assumption. Gazelles, for instance, are lighter on the bottom, and darker on top, reversing the natural shading scheme, which helps camouflage them against predators.

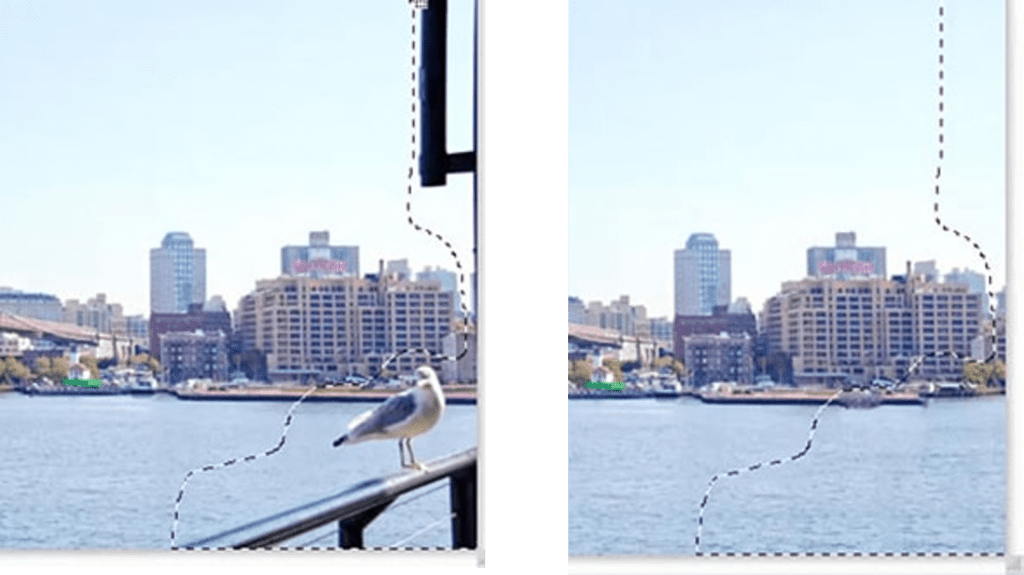

Not only are our brains wired to rapidly make connections to internal patterns or templates, in order to achieve quick results, the brain is and expert Photoshopper that fills in any missing details. For those of you familiar with Adobe Photoshop, you might know that an experienced user can get rid of unwanted items or fill in areas which have been missing in the captured image.

Our eyes and brains do the same thing. As most people know, light passes through the pupil in the eye, strikes the retina in the back of the eye, and then light-sensing proteins on the retina send that information along the optic nerve to the brain. The problem is that where the optic nerve exits the eye, there is a visual gap, a hole, a blind spot where the eye can’t see part of the incoming image. With binocular vision, the other eye helps fill in the missing information—helps—but because of what’s known as the parallax problem it can’t always fill in the missing details. And if you look at things with one eye closed, you don’t see the hole—the blind spot. Why? Because the brain fills in the missing information in almost Photoshop fashion. Your brain fabricates a reality so your vision makes sense. And in order to makes sense of the world, our brains have to rely on internal patterns or templates.

Pareidolia is not limited to sight. We can also experience the phenomenon with things we hear. Electronic Voice Phenomenon, for instance, is what we find utilized by ghost hunters who pour over hours of static audio or white noise to pick out a few sounds here and there that sound like spoken words. Any changes in the level, tone, or oscillation of the static is seen as a pattern of human voices. On a more common level, how often do we mistakenly think someone said something that was different than what they actually said. We mishear when our brains fill in fuzzy audio with what we assumed they’d say.

Lastly, and I don’t have time to go into more detail in this presentation, erroneous pattern-matching can happen not only with visual and auditory input, but with the recalling of memories, and even when we formulate inner cognitive arguments, logic, and rationale.

We often feel compelled to assign meaning to perceived patterns—this is known as apophenia (or what Michael Shermer referred to—above—as agenticity). Sometimes it’s too easy—and we feel almost obliged—to connect the dots. The connections may seem too obvious to avoid connecting. And, of course, that’s where the liability of the feature can emerge—we can assign meaning when no meaning is really there, because the pattern of dots parallels our assumptions.

While can’t always un-see a face in an inanimate object, but we can consciously decide that the shapes only coincidentally seem to show a face and that there isn’t some hidden meaning behind the illusion. This is sometimes easier said than done, because brains like to make sense of things and the best way to make such sense is to fit data pegs into holes with which we are already comfortable. Even with our best efforts we will never escape all the cognitive baggage that impedes our ability to fully understand and analyze the data we encounter.

We cannot escape the limits of our own physical and cognitive parameters or get out of your own heads. We also cannot fully understand another person’s suffering, joy, or thought process. It is not humanly possible to see, hear, and feel things as they really are. It is not humanly possible to fully understand God’s mind and will or even, I believe, to fully understand His communications. We are trapped in black and white TVs even though color signals go racing above our heads.

Heavenly Father is aware of our limitations and knows the factors which contribute to our limitations. Despite our deficiencies, however, He also knows how to communicate important directives as we are able to receive them. Telling your two-year-old not to let go of your hand in a crowded parking lot probably sounds—to your child—a lot more like a demand for blind obedience than advice based on logic and circumstance. As the child grows older and understand the risk of cars, your directive might morph to “stay next to me,” or later “watch out for the cars.” While your guidance as a parent is the same in each instance of your child’s life, the words, metaphors, examples, or logic you use changes according to their stage of life. You, as a parent, know how to modify your communication according to your child’s cognitive limitations. God does the same thing. In D&C 1:24 He says: “Behold, I am God and have spoken it; these commandments are of me, and were given unto my servants in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding.”

What this means is that God communicates to all people (and that includes prophets) through their own language. When we hear the word language we generally associate the term with spoken or written words—such as the languages of English, Spanish, German, Chinese, or Klingon. But in the context of D&C 1:24, I believe that language refers to a much broader composition and includes not only spoken and written words but context influenced by cultural, education, era, as well as cognitive, visual, and auditory disabilities or vulnerabilities, including bias, assumptions, and pre-conceived notions.

Non-LDS theologians often refer to God’s ability to tailor His communication to mortals as Divine Accommodation, or less frequently as Divine Condescension. As non-LDS theologian Stephen D. Benin writes: “Divine accommodation/condescension alleges, most simply, that divine revelation is adjusted to the disparate intellectual and spiritual level of humanity at different times in history.”[x]

As near as I can tell Latter-day Saints have not generally used the term “accommodation” to refer to God’s method of adapting His word to His children ability to hear, and the term “condescension” in LDS terminology, generally refers to act of Christ leaving his pre-mortal status in the heavens to descend to earth and take on mortal flesh. As President Ezra Taft Benson taught, divine condescension refers to Christ coming “down from an exalted position to a place of inferior station.”

While the LDS and non-LDS terminology may different, Latter-day Saints likewise believe that God accommodates His word to conform to the recipient of the word. Our ability to comprehend God and His directives is limited. God must descend to our level and speak our language in order for us to comprehend.

We have a great example of human-generated accommodation in the Book of Mormon. When Ammon, one of the sons of Mosiah, went to teach the Lamanites, he was captured, brought before King Lamoni, and eventually was assigned to guard the king’s flocks. Ammon proved to be a kind of Nephite-ninja and after saving the king’s flocks from some wannabe-thieves, Ammon was brought again before the king—this time to explain why he was so tough. As Ammon began his explanation he asked King Lamoni, “Believest thou that there is a God?” to which Lamoni answered, “I do not know what that meaneth.”

We have a great example of human-generated accommodation in the Book of Mormon. When Ammon, one of the sons of Mosiah, went to teach the Lamanites, he was captured, brought before King Lamoni, and eventually was assigned to guard the king’s flocks. Ammon proved to be a kind of Nephite-ninja and after saving the king’s flocks from some wannabe-thieves, Ammon was brought again before the king—this time to explain why he was so tough. As Ammon began his explanation he asked King Lamoni, “Believest thou that there is a God?” to which Lamoni answered, “I do not know what that meaneth.”

And then Ammon said: Believest thou that there is a Great Spirit?

And he said, Yea.

And Ammon said: This is God (Alma 18:26-28).

Now critics have tried to use this passage to say, “See, the Book of Mormon teaches that God is a Spirit!” They completely miss the point of the Ammon/Lamoni exchange, however. Ammon was trying to explain who God was by teaching in concepts which Lamoni understood. Ammon accommodated his discourse so that it made sense to Lamoni. According to how Lamoni understood God—which was a great spirit—Ammon’s power came from that same being—the Great Spirit, God. The details could be explained later. The initial purpose was for Ammon to explain some basic principles.

Some scholars have pointed out that Paul likewise accommodated his message according to his audience—tailoring his message and words depending on whether he was addressing Jews or Romans. “‘The Romans,’” writes Dr. Stephen Benin, “‘still required much accommodation. Paul was waiting for faith to be first of all fixed in their hearts. He feared that he would prematurely and too quickly pull up the weeds and along with them the plants of sound instruction. [Matt 13:29.]’”[xi]

My own studies lead me to conclude that Divine Accommodation is only half of the communication dilemma between God and His children. God knows that we are incapable or unprepared to receive all of His teachings, therefore His communication accommodates our deficiencies. But the other problem is that our deficiencies impede our ability to properly hear, understand, nor interpret those things which God attempts to convey. Paul told the Corinthians that we mortals “see through a glass, darkly,” (1 Corin. 13:12)—imperfectly, or dimly. Even if God were to send a full color signal, our minds are like black and white TVs and are incapable of receiving the full spectrum of His word. This, of course, applies to each of us as we receive personal revelation, as well as to prophets who receive revelation for their greater sphere of responsibility.

Divine communication appears to be a mix of God’s Divine Accommodation and humankind’s Recontextualization. As human creatures whose mortal characteristics are the byproducts of millions years of evolutionary development, we are unable to process ideas without recontextualizing them according to patterns. These patterns could be a result of nature and nurture, and likely represent both. Data—visual, auditory, recollective, contemplative, or even revelatory, must be processed by a human mind that will recontextualize the data according to internal patterns. Now it’s important to note that these patterns need not be rigid. Most people think about things differently at 5, 25, 55, and 75 years of age. We change our minds and gather new data—new information can cause us to modify, reject, or replace previous patterns. When we uncompromisingly cling to patterns, however, we risk constructing a fundamentalist mind-set.

I won’t go have the time to into the details in this presentation but I’ve written just a bit more about our pattern-seeking brains in my chapter in the newly released book by Kofford books. In brief, however, our brains process information by fitting (even force-fitting or recontextualizing) data into the context of our own personal paradigms. From the perspective of LDS scholarly and apologetics studies, the recognition of or limited ability to accurately hear God’s word is found in at least 3 layers—or what I call the three Rs: Receiving, Recording, and Recontextualizing.

- Receiving: The ability to accurately and exhaustively receive the Word of God is dependent on the person receiving the information. Because all mortals have minds like black and white TVs, no human can fully receive all the colorful details of every revelation which God would like to share. Each individual person or prophet will be unique in their ability to accurately hear the word of God; the accuracy or completeness, of which, might depend on the person’s sphere of responsibility, worthiness, education, culture, circumstance, and expectations.

- Recording: When scripture moves from mind to pen, another layer of complication is added to the communication process. God may help here (such as when Joseph translated the Book of Mormon) but the words must still must be recorded in the weakness of human language.

As I explained in greater detail in Shaken Faith Syndrome, words do not have “plain” meanings; they only have meaning in the context of a language, culture, timeframe, and in relation to other words. Authors write from within both a cultural and personal context, and readers automatically recontextualize those words according to their own cultural and personal context. At least some ambiguity and misunderstanding (or at least an incomplete understanding) is inevitable. So even if a prophet received word for word instructions from God—void of any association to the prophet’s cultural and personal worldviews—those who read or hear the prophet’s words would still be unable to completely understand the fullness of all of God’s words because their own personal worldviews and context inequalities would be slightly (or vastly) different than the context in which the original words were given. When we add to this the problem of contextual segregation caused by big differences in time or cultural distance between the prophet’s time and culture and the reader’s time and culture, the problem of fully understanding the prophet’s word (God’s words) becomes even more difficult.

- Lastly, we have recontextualizating: This basically refers to how a prophet (or reader of the scripture) automatically will recontextualize or interpret the word of God according to all of those patterns that are set in the mind by either nature, nurture, or both.

My bigger project is working on showing some of many examples where we see this process happening in the scriptures or in LDS history. Because the project is still a work in progress, and because of the time limitations of today’s presentation, I’ll give a couple of examples as teasers and note some of the areas I’m exploring.

First, here’s a pretty innocuous one that comes from the D&C 17 which comes from an 1829 revelation through Joseph Smith telling the Three Witnesses that the time would come when they would be privileged to see the plates. Verse 1 reads, in part, SL43 “Behold, I say unto you, that you must rely upon my word, which if you do with full purpose of heart, you shall have a view of the plates, and also of the breastplate, the sword of Laban, the Urim and Thummim, which were given to the brother of Jared upon the mount….” Similar promises were in the Book of Mormon itself.[xii]

While Joseph Smith dictated the original revelation to Oliver in March of 1829, the original copy of this revelation was eventually lost.

In 1833 the Saints gathered as many of Joseph’s revelations as they could find and printed them under the cover of the Book of Commandments, but a number of revelations—including the 1829 revelation to the Witnesses—were not included. [xiii] The Book of Commandments project was abruptly terminated when several hundred Missouri vigilantes stormed the printing office and destroyed the press and most of the books—fewer than 30 copies are known to exist today. It didn’t take long for the Saints to try again, this time culminating in the 1835 compilation known as the Doctrine and Covenants.

Some between November 1834 and the publication of the Doctrine and Covenants, Josephs’ scribe Frederick G. Williams created a copy of the 1829 Witnesses revelation, and that copy was used for what we have in Chapter 17 of the Doctrine and Covenants (and the Church still has the 1834 copy in Williams handwriting). We know that an earlier copy of the revelation really existed because in 1831, Ezra Booth—a Methodist minister who became Mormon then left the Church less than a year later—mentioned in an exchange with the editor of the Ohio Star that he “an opportunity to examine a commandment given to these witnesses, previous to their seeing the plates.”[xiv]

To summarize this timeline: Joseph dictated a revelation to three Witness in 1829. The revelation was never included in the Book of Commandments in 1833. Around the end of 1834 Williams made a copy of the revelation and uses it for the master of D&C 17. Why is any of this important?

The 1834 manuscript copy of the revelation uses anachronistic language—terms that would likely would not have been used in 1829 when the revelation was originally dictated and recorded. It’s important first to remember that Latter-day Saints have never believed in an unalterable book of scriptures. Oliver Cowdery amended and corrected what he saw as transcriptional errors in the original Book of Mormon manuscript when he copied it to the printer’s manuscript. Joseph smith amended and corrected errors in the subsequent Book of Mormon editions when it was time for a new printing. The LDS church now makes corrections when they see errors which need correcting. So likewise, the D&C was amended and corrected as needed. Some of those corrections called for updating language in order for the revelations to make more sense and to be more congruent with other revelations.

In Williams’ 1834 copy of the 1829 revelation, for example, we read that the Three Witnesses would be privileged to see the “Urim and Thummin.” In 1829, however, the two-stoned translating device buried with the plates were not yet called the Urim and Thummim. When Joseph retrieved the Book of Mormon plates, he also found a breastplate and the Nephite “interpreters.” In LDS literature the interpreters were not known as the “Urim and Thummim” until roughly 1833.[xv] From 1827—when Joseph actually took possession of the plates and the interpreters—until about 1832 or 1833, the translating device was known as the “spectacles.” Evidence suggests therefore, that the current rendition of the 1829 revelation anachronistically refers to the “spectacles” as the “Urim and Thummim” even though that would not have been the term used to denote the interpreters in the original dictation of the revelation.

The emendation was made either by Williams, a previous editor, or Joseph Smith himself, in order to recontextualize the revelation to the current usage of terms. If the term “Urim and Thummim” was anachronistic for the 1829 D&C17:1 revelation, it is equally anachronistic in Joseph’s recollections as recording in Joseph Smith History 1:35 wherein he says that in 1823 Moroni referred to the translating stones as the Urim and Thummim.

There is nothing inherently wrong with using familiar terms to describe foreign objects, events, places, people, animals, and so on. If you go on a modern cruise you might set “sail” near sunset even though the cruise ship has no sails. Your computer “save” icon may depict a floppy disk although computers today don’t use floppy disks. Is it wrong to refer to Roman soldiers knowing that the world “soldier” is a French word that wasn’t created until at least six hundred years after there were Roman soldiers? By the time Joseph recounted his history, and by the time the Doctrine and Covenants was printed, the “spectacles” were known among the Latter-day Saints as the “Urim and Thummim.” Using the then-current LDS term more clearly communicated the intent of the term to an LDS audience.

Applying the reception, recording, and recontextualization approach to the Book of Mormon helps us to understand, in part, why there are different views on Book of Mormon geography. Joseph apparently didn’t receive revelation as to the geographic locations for Nephite events, but was left to recontextualize from what he believed about the world around him.

In Joseph’s day, many Americans believed that Native American were the descendants of the 10 lost tribes of Israel. The Book of Mormon was brand new. And while it was instrumental in helping to launch a new religion, there weren’t any real scholarly studies of the book. Statistics show that during the nineteenth century, the Book of Mormon was cited far less in conference talks than citations of the Old and New Testaments.[xvi] The early Latter-day Saints were still trying to figure out what the Book of Mormon was saying—not only in spiritual teachings but from the perspective of an historical record. They attempted to recontextualize an early Israelite American population as recording in the Book of Mormon with the scientific view of their day.

When Joseph translated the Book of Mormon, the Saints learned that the theories of ancient Old World inhabitants living in the Americas was true. In the language of the early Latter-day Saints, every mound was somehow linked to the Nephites or Lamanites, and all ancient bones unearthed were undoubtedly evidence of the Lamanite and Nephite wars.

In 1834 while traveling to Missouri with Zion’s camp, Joseph and several other members passed through Pike County, Illinois, which was dotted with Indian burial mounds, bones and other artifacts. Writing to his wife Emma, he recounted how their group had wandered over the plains of the Nephites and the mounds of the Book of Mormon people, “picking up their skulls & their bones, as a proof of its divine authenticity….”[xvii] Joseph, like all people, recontextualized the bones with the Nephites. Similarly, the shape of North and South America, with a narrow neck of land in modern-day Panama, was too easy not to connect the dots. It was only after some Saints began more a more rigorous examination of the actual Book of Mormon text before limited geographic models appeared.

Bible: Ben Spackman may likely touch on this in his talk tomorrow, but the Noachian flood’s treatment in the Book of Mormon is also a likely consequence of the same limited revelatory process. Many Latter-day Saints have found support for a global flood within the pages of the Nephite record, but a closer examination reveals that such a conclusion is not required. In Ether, for example, we read that “after the waters had receded from off the face of this land it became a choice land above all other lands” (Ether 13:2). We know that the Jaredites (as interpreted by Moroni) were familiar with Noah’s ark (Ether 6:7) so these verses imply a world-wide global flood. It’s important to remember, however, that the Book of Mormon peoples themselves didn’t experience the flood. Neither Moroni nor Ether would have known from personal experience that the waters receded from the face of the New World. They believed that this is what happened, but that’s not the same as claiming to be witnesses to the event.

It’s entirely possible that either Ether, Moroni, or even Joseph Smith included the comment about the waters receding from the land based on their understanding of the ancient New World and according to their interpretation of the Noachian flood as recorded in Genesis.

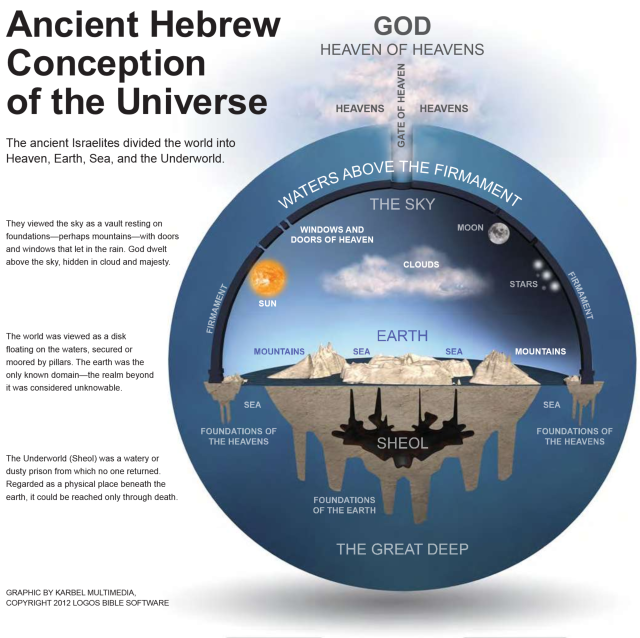

If we apply the framework to other scriptures we open the doors to greater enlightenment and wisdom as well. I suspect that Ben Spackman will give us some great examples tomorrow, but it seems unescapable to recognize that those who wrote Genesis recorded their understanding of God’s relationship with the Earth and His children according to the recontextualizations of inspired truths and the prevailing cultural understanding of the cosmos.

Ugo Perego’s talk tomorrow on evolution may address the nineteenth century recontextualiztion of Genesis and how many assumed it should respond to the development of earth life compared to how science reveals the development of earth life.

The Book of Abraham: Both believers and critics typically bring a set of assumptions to the study of the translation of the Joseph Smith Papyri. Critics approach the translation already knowing that Joseph Smith couldn’t actually translate Egyptian and unsurprisingly find evidence that favors their expectations. Many believers, on the other hand, approach the study of the JSP with the assumption that God divinely revealed an authentic ancient Book of Abraham text to Joseph Smith and unsurprisingly find evidence which favors their assumptions. My project will address the possibility that there is more going on than is adequately addressed by either assumption and posits that the translation—which I believe came by divine revelation—may be a nineteenth-century inspired recontextualization of an ancient recontextualization of an inspired narrative.

The Joseph Smith Translation: If we recognize the Triple R infrastructure in revelation, we can appreciate that the JST is possibly an inspired nineteenth-century recontextualization of the Bible, and not necessarily a retranslation of missing parts of original Biblical manuscripts.

Early LDS history: Brigham Young very likely recontextualized common Protestant beliefs about African Americans and applied that recontextualization to the prohibition of black members holding the priesthood. Later Mormons recontextualized verses from the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and the Book of Abraham to maintain and defend the prohibition. The Word of Wisdom, Temple ceremonies and attire, and Plural marriage practices were all likely recontextualized by prophets and members in a synthesis of cultural expectations and assumptions, and actual revelation.

When Joseph Smith received his First Vision it seems inescapable to me that the vision had to be framed from within a context—a recontextualization—of what Joseph Smith might have expected or understood about God and Jesus. Christians are those who typically see (either automatically or with a bit of suggestion) the face of Jesus in burnt toast. If a baby boomer, who for some reason never had any exposure to Jesus or pictures of Jesus, saw the burnt toast, he might easily see the face of a 1960s rocker from Woodstock.

Catholics are the more likely persons to see the figure of Mary in water stains. In a 2007 FairMormon Conference address, Blake Ostler suggested that we adopt “religious inclusivism,” and recognize that God can share light to people in many different ways and under many different circumstances. “Now we may be called into question,” he wrote, “if somebody has a vision, for instance, of the Virgin Mary; because I don’t believe that the LDS believe that the Virgin Mary puts in many appearances. However I suggest that we look beyond what divides us and look to ‘inclusivism,’ and that is, ‘What is it that they learned? What does their religious experience teach them?’ Because God will adapt his message to any culture, and any means that He can, to increase the light of a person….”[xviii] I think this is great advice, because certainly God (as well as the human brain) can recontextualize spiritual promptings for a Catholic that involves “the manner of language” that belongs to Catholicism. He can communicate via human recontextualized language to give wisdom, comfort, and inspiration.

Critics connect the dots between environmental parallels and the Book of Mormon or Joseph’s revelations thereby creating a pattern which they believe demonstrates a cause and effect relationship. Joseph eclectically selected from the teachings (or even names) from his environment as he assembled and solidified his new religion. But this is not the only way to connect the dots and to address any parallels. I maintain that because Joseph was a cultural, spiritual, and biological product of his environment, there was no other way for him to receive, record, and recontextualize God’s word without involving the manner of his language. There is no other way for humans to share or even to understand and internalize information—worldly or other-worldly—without filtering and framing that information according to what their brains allow them to perceive and assume. We have black and white receptors even when God communicates in 8K color.

Revelation will unavoidably and necessarily reflect—to some degree—the receiver’s human limitations. The Book of Mormon reflects the recontextualizations of not only each author, and each redactor, but also that of the translator and each reader. Joseph’s revelations as well as his speculations are also colored with the patina of his environment, because he was human and that’s how the mind works—but the tinting of mortal minds doesn’t preclude a belief that those divine instructions also reflect divine input. People tend to look like their parents. I look like my Dad, but that doesn’t mean that I also don’t also look like my Mom. I’m a blend of them both, just as the receiving, recording, and recontextualization of revelation is blend of both divine instruction and a filtering of the receiver’s humanity.

The Lord, in His wisdom, knows that His children are unable to escape from the boundaries of their psychological, cognitive, and cultural enclosure while they remain mortal. He knows that they will get things wrong, describe things inaccurately, point to non-existent evidence while rejecting very real evidence, and will, at times, make a mess of the historical recitations of the stories that tell of God’s encounters with past generations. Knowing all the challenges, God also knows that the only way that we can understand the important and basic principles of discipleship is by having his teachings revealed in the weak manner our “language” so that the weak things will become strong enough to put us on a course that brings us back home to the Father (see Ether 12:27).

Q&A

Q 1: Is Adam-Ondi-Ahman a possible re-contextualization rather than an historical site?

A 1: That’s actually one area I’m working on and I think that there’s a lot in the history of Joseph Smith. Sometimes it’s a blend and a fine line of things that are revealed, true things that are revealed but we still have to put in a format that we can understand. So I’ll put that as “not fully answered”.

Q 2: In your opinion, did Joseph Smith start calling the[m] spectacles because those of his day were calling it so or because those of his day starting calling spectacles the Urim and Thummim because Joseph Smith was calling it? So which came first.

A 2: I actually had to cut in order of the interest of time. The Urim and Thummim in Joseph Smith’s day, there were many books written by scholars [and] religious pundits that talked about it as a means of divine communication and they were seeing it, of course, from the Bible. I think it was, and I’m trying to remember it now, if it was W. W. Phelps that we use his [statement] from an article in 1833 where we find the first usage of the term Urim and Thummim. [There] he says it would have been something “like the Urim and Thummim”. And I think people said, “Oh, yeah, that’s good.” So whether he came up with it or not, it’s hard to say. I think that it’s possible. We[‘ll] never know if Joseph Smith was the first to suggest that. But the reason they called it spectacles is that’s what it looked like. Or so we’ve been told. Again, that’s an interesting part of my project that I’m working on. We’ll come around to that at some point when I’m finished.

Q 3: You seem to wholeheartedly accept the scientific assumptions about human evolution. While I’m interested in Ugo Perego’s talk on the topic tomorrow, I would be interested to hear a brief explanation of your belief in evolution in the context of faith.

A 3: I won’t jump at this because I think Ugo’s going to do a wonderful job on this tomorrow. I’ve changed through the years, my assumptions have changed. When I was younger I kind of had the Creationist view, and as I get older, I think that, like I said at the beginning, “truth is truth”, that God reveals things through Latter-day Saints, through scientists, maybe through Atheists, definitely through Catholics and Buddhists and so forth. Truth is out there and we have to fight really hard to stick to any kind of view that is not supported by evolution. There’s too many forms of convergence of science that point to it in my opinion, and I think it’s completely acceptable and falls in line with the gospel, and that’s again at least one of the chapters that I’m working on.

Q 4: If everyone, prophets included, “see through a glass darkly” in what we individually and collectively decide is valid, is truth inescapably arbitrary?

A 4: That’s a good question, you know, how do we know? I think that the key is that the Lord knows, and that’s where faith comes in. We’re not going to have that sure knowledge, we’re going to stumble. But it’s a matter of where our hearts are. Are our hearts aligned with the principles of the gospel? Are we really trying? Are we recognizing our limitations and are we trying to understand the will of God? And there are some people that I believe will stumble. Initially I said we can never know another person’s joy, suffering, pain and so forth; and I think the same thing’s true for those that fall away. We don’t know why they fell away. We can guess, but we don’t know. We’re not in their shoes. We don’t have their cognitive limitations, emotional baggage and so forth; we have our own. We can’t get outside of our head. So we have to trust God that if there were factors in that person’s life that just made it overwhelming that they had to fall away, the Lord’s loving. He’s going to be able to unravel these things. That’s not our job. We can help people along, to show them, “Here’s the other side of the coin, here’s how we can look at different things.” But that’s, I think, one of the big reasons we’re told not to judge: we can’t get inside of their heads.

Q 6: How do we show LDS researchers are as trustworthy as non-LDS researchers?

A 6: I spend at least a good chapter of that in the book that I’m working on and quite a bit of it in Shaken Faith Syndrome: every person on this planet has bias. That’s one of the things I talk about in my previous book, that the critics often say, “Well, you can’t trust the Latter-day Saints scholars because they’re Mormon, so of course they’re gonna stick with the story.” Well, that’s meaningless. Everybody has a perspective, everybody has a bias. We’re all coming from a position, and it might be somewhere in between there, but we can’t escape it.

Q 7: Can we have an enduring testimony of the gospel without accepting the Atonement of Jesus Christ?

A 7: Again, that’s a tough one because I think it comes down to Christ. We have to have a testimony of Christ. But why does somebody not have a testimony of Christ? They and God know. We don’t. It’s not up to us to decide, we have to look into ourselves. We’re in this all together, as a family, as God’s children, but we have to work individually. Ultimately it comes down between us and God. There’s no shirttails to ride on to get to Celestial glory. We have to strengthen ourselves and help to strengthen those around us, but we can only lead horses to water, we can’t make them drink. So we put faith in God that He’ll sort this all out. He knows what’s going on in their hearts and minds. We don’t.

Endnotes

[i] Joseph Smith, Discourses of the Prophet Joseph Smith

[ii] Michael Shermer, The Believing Brain: From Ghosts and Gods to Politics and Conspiracies: How We Construct Beliefs and Reinforce Them as Truths (Henry Holt and Co., Kindle Edition), 5.

[iii] Vincent M. Reid, Kristy Dunn, Robert J. Young, Johnson Amu, Tim Donovan, and Nadja Reissland, “The Human Fetus Preferentially Engages with Face-like Visual Stimuli,” Current Biology at http://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(17)30580-8?_returnURL=http%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0960982217305808%3Fshowall%3Dtrue (accessed 1 August 2017).

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Stewart Guthrie, Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion (Oxford University Press, 1993), 6.

[vi] Thomas Gilovich, (2008-06-30). How We Know What Isn’t So (Free Press. Kindle Edition, 30 June 2008), 164-165.

[vii] Steven Pinker, How the Mind Works (W. W. Norton & Company, 1997, Kindle Edition), 28.

[viii] Ibid., 29.

[ix] Vilaynur S. Ramachandran and Diane Rogers-Ramachandran, “Shading Illusions: How 2-D Becomes 3-D in the Mind,” at https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/seeing-is-believing-aug-08/

[x] Stephen D. Benin, The Footprints of God: Divine Accommodation in Jewish and Christian Thought, xiv.

[xi] Quoted in Footprints of God, 64.

[xii] See Ether 5:2-4, and 2 Ne. 11:3, 27:12.

[xiii] See http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/book-of-commandments-1833/1#historical-intro

[xiv] Ohio Star, 27 October 1831, available at http://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/BOMP/id/509/rec/119

[xv] See Michael Barker, “Doctrine and Covenants Sections 14, 15, 16, 17, 18: An Historical Perspective,” 22 February 2013 at http://rationalfaiths.com/doctrine-and-covenants-sections-14-15-16-17-18-an-historical-perspective/, accessed 31 July 2017. See also http://en.fairmormon.org/Book_of_Mormon/Translation/Urim_and_Thummim (accessed 31 July 2017).

[xvi] See Statistical breakdown of LDS (Mormon) scripture citations at http://scriptures.byu.edu/#0d5276:t41ee2$112245:fNYNY726744020d5276 (accessed 28 July 2017).

[xvii] Joseph Smith, Letter to Emma Smith, 4 June 1834 at http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-to-emma-smith-4-june-1834/2 (accessed 20 July 2017).

[xviii] Blake Ostler, “Spiritual Experiences as the Basis for Belief and Commitment,” at https://www.fairmormon.org/conference/august-2007/spiritual-experiences-as-the-basis-for-belief-and-commitment (accessed 20 July 2017).