August 2017

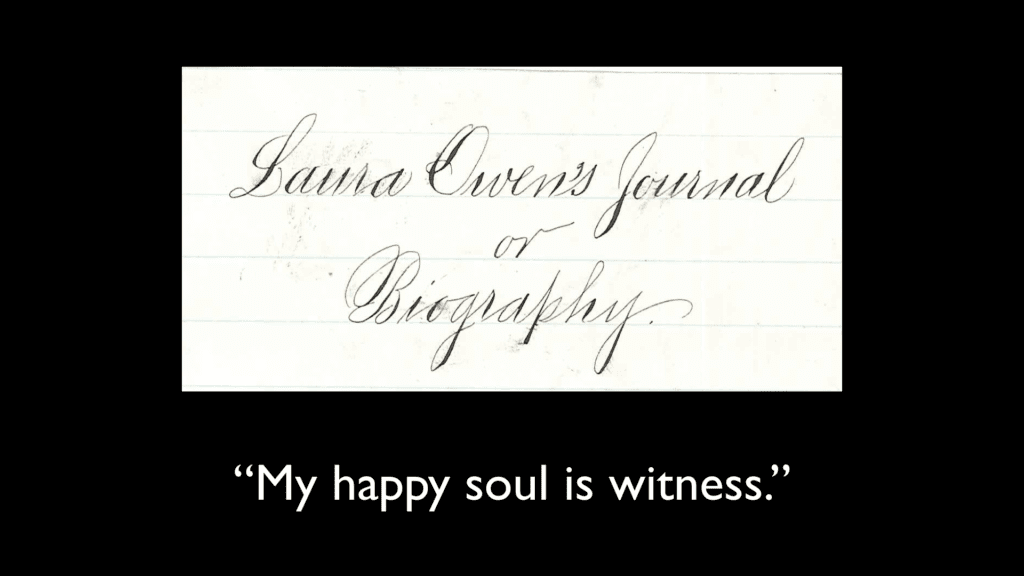

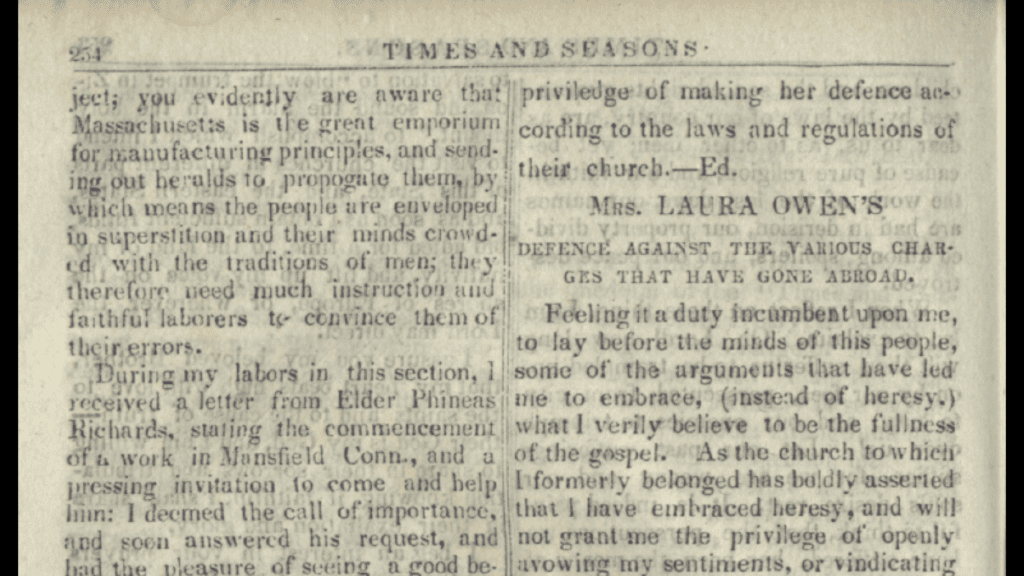

She exulted, “If this is delusion, then happy delusion!” She felt it was “a duty incumbent upon” her to witness to that which she “verily believed to be the fullness of the gospel.” And testified, “I longed for union, and for latter-day glory; and my happy soul is witness that it has commenced.”[1]

Laura’s Defence of Mormonism would be lost to history were it not for an editor at the Times and Seasons in Nauvoo, who though “it of too much value to be lost” and reprinted it.[2] I think about that prescient editor and how he recognized the value of Laura’s voice though she would never be one of the leading sisters of Zion nor play a central role as the Restoration moved forward. Hers was still an important contribution to the tapestry of the Restoration—her soul, her experience, and her voice is of infinite worth.

Several years ago I saw several medieval unicorn tapestries at the Met’s Cloisters for the first time and marveled at these gorgeous textiles created in the early sixteenth century. Medieval Christians appropriated pagan symbols and transformed them into a Passion narrative—the unicorn became representative of Christ.

A few years ago I saw weavers in Scotland’s Sterling Castle work to recreate similar unicorn tapestries that once flanked the walls. Weaving is a complicated and an intricate skill. Yet, no matter the extensive investment in the original tapestries, over time they will deteriorate.

Over time sections of the tapestry will be lost. Faces, characters, textures, and colors can all fade.

For me, a tapestry in need of restoration accurately continues to depict our current understanding of the Restoration. A tapestry requiring continuing attention, meticulous research, and detail work so that we can take it in, in all its grandeur—an ongoing Restoration. Some of the parts of the tapestry retain their central place, though perhaps some of their detail and their shadows have dulled over time. Much work has been done in the recent past to restore parts of the tapestry, but there are still many parts almost lost to time. Many colors and textures and details once essential now faded. We see the tapestry so often that sometimes we don’t even notice.

One of the significant frayed sections of the tapestry depicts women, but it is not the only part of the tapestry in need of continued work. Today I will focus on what we miss when women’s voices and experiences—like Laura’s—become threadbare. At the Mormon History Association conference this June, Elder Steven E. Snow, Church Historian and Recorder, remarked, “For too long [Mormon women’s] voices have not been fully recognized and we as a Church suffer because of this.”

As a religion professor with my students, in interactions with friends, and on social media I daily feel reminders that our suffering is current—Elder Snow’s choice of the present tense was purposeful. A powerful reminder that we need to do better.

This has gone on for too long, however this element of the tapestry has not always been missing and in fits and starts began to be included years ago.

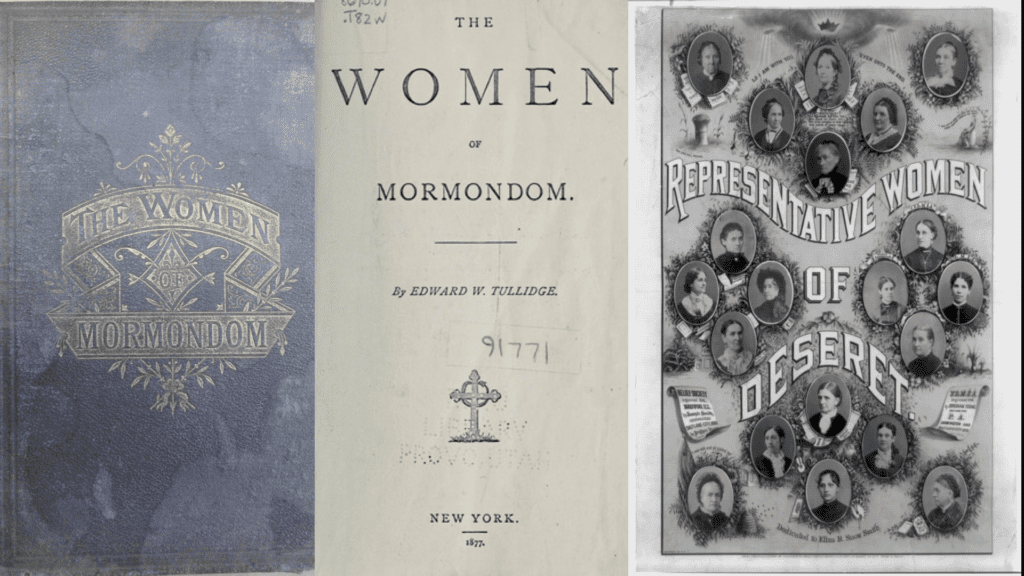

Beginning in the 1870s there were several efforts to collect and publish Mormon women’s experiences. The Relief Society encouraged women to contribute to Edward Tullidge’s Women of Mormondom first published in 1877. Though to access those women’s voices you have to wade through Tullidge’s dense and flowery prose, the women’s voices still provide a significant contribution which stand apart. Several years later Augusta Joyce Crocheron also collected women’s primary accounts to create Representative Women of Deseret.[3]

But far and away the most abundant single source of nineteenth-century Mormon women’s voices come in the Woman’s Exponent. Though privately funded, the Woman’s Exponent was the magazine of the Relief Society from 1872 to 1914. Brigham Young directed Editor Emmeline Wells to publish “the record of [women’s] work and a portion of Church history” and gave her “a mission to write brief sketches of the lives of the leading women of Zion, and publish them.”[4] On the newsprint of the Exponent women testified, theologized, and gave voice to their experiences. It not only records the “leading women of Zion” but an extensive spectrum of distinct women. Some only identified by their initials or a pseudonym.

In the intervening years the Restoration’s tapestry has altered. The process of deterioration began.

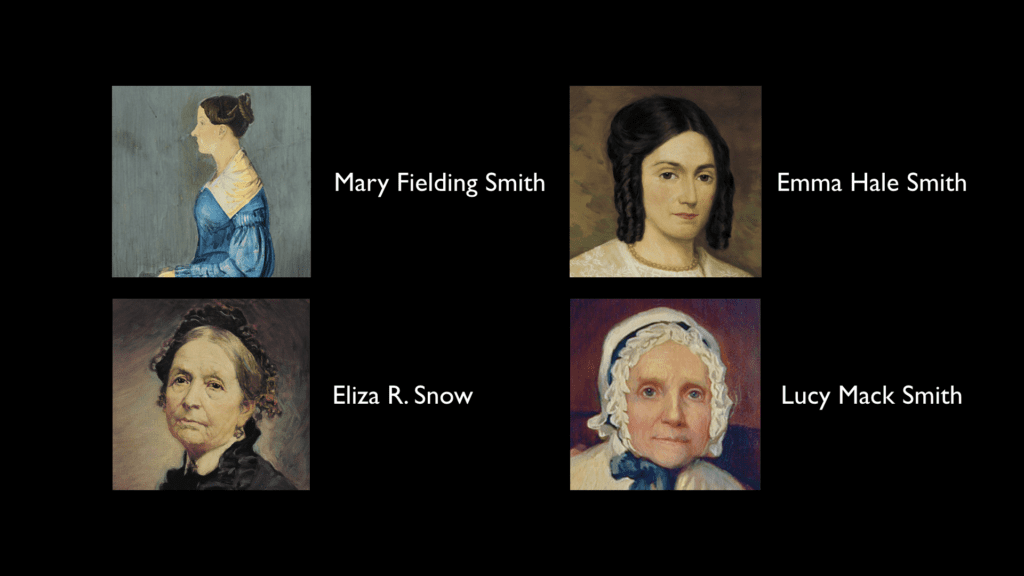

A few years ago women’s history specialist Brittany Chapman sent out a survey and asked different groups of Latter-day Saints, “How many women of the Restoration can you name?” I have continued Brittany’s efforts to much the same result.

In nearly every instance, the same four women were named—Mary Fielding Smith, Emma Smith, Lucy Mack Smith, and Eliza R. Snow. Every once in a while another woman would be thrown in for good measure—most often demonstrating someone had been doing their family history recently. While I am certainly a fan of those four, I lament that the history of at least half of those who believed in the Restoration has been reduced to four women. And often any details of their lives, beyond connections to husbands, were supremely vague.

We all can do more to educate ourselves, yet until more recently official church materials have not come to our aid. Though Mormon women’s history began to recover these women’s lives beginning in the 1970s, it has still only entered the devotional narrative of LDS History in cursory ways. In part, we might account for this because Mormon Women’s History has been overwhelmingly biographical. While compensatory history is essential and the biographical form is great to learn about the women of the Restoration; it is not always easily incorporated into the larger devotional narrative of church history.

In example, in the Gospel Doctrine manual for this year—Doctrine and Covenants and Church History—there are a total of ten specific women included in the lessons in the manual. Twice women’s names are just mentioned, three stories are told about Lucy Mack Smith, four times women’s own accounts are referenced, once a picture of a woman is suggested, and four examples of contemporary women are used. Not a single talk by a woman in a contemporary leadership position is quoted. If you go to the fantastic additional resources made available by the Church History department from Revelations in Context and history.lds.org those numbers expand considerably—but one has to go beyond what is specifically included in the manual. As a BYU student recently told her religion professor, “Just saying that we value women is not enough. We didn’t read any women’s accounts this semester.” We need to hear women’s voices. We need to read their words. We need to know of their experience.

When Christ came to the Americas, he asked to see the Nephite records. For all their attention to records, he knew they were incomplete. They were missing the record of Samuel the Lamanite. Jesus asked, “How is it that ye have not written this thing that many saints did arise and appear unto many and did minister unto them?” He asked the question and it was simply fixed—“it was written as he commanded.” (3 Nephi 23:9–13) No fanfare or lamentations at their mistake. It was just fixed.

Without the experience of at least half of those who believed in Joseph’s message of restoration, our understanding is incomplete. Our fulfillment of that commandment given the first day of the newly organized Church of Christ that “there shall be a record be kept among” us, remains incomplete. (Doctrine and Covenants 21:1)

When I cracked open my copy of Rough Stone Rolling for the first time and read Richard Bushman’s prologue to his biography of Joseph Smith, I began to understand the almost hackneyed Josiah Quincy quote about Joseph Smith. Quincy waxed prophetic asking, “What historical American of the nineteenth century has exerted the most powerful influence upon the destinies of his countrymen? And it is by no means impossible that the answer to that interrogatory may be thus written: Joseph Smith, the Mormon prophet.”[5] Bushman argues that Quincy was so wrapped up in the personality of Smith that he could not see Joseph as did his followers, as a prophet.[6] I then read the words written by an early convert, Phebe Crosby Peck, to her sister, “Did you know of the things of God and could you receive the blessings that I have from the hand of the Lord you would not think it a hardship to come here for the Lord is revealing the misteries of the heavenly Kingdom unto his Children.”[7] It was a poignant moment for me because I knew someone had not only read something that I published, but they thought it significant enough to quote it.

Phebe Crosby Peck was a widow with 5 young children living in Colesville when she heard of Joseph Smith from her sister-in-law Polly Peck Knight. She wrote that letter to her sister who had stayed behind in New York instead of gathering with the Saints.

I recognize the calculated choice that was the inclusion of Phebe’s words. Bushman doesn’t even call her by name, it is only the pronoun that tips us off to the gender of the source. Bushman could have more easily found a quote from male LDS Church leadership that would have reflected essentially the same sentiment. But not only male LDS Church leaders believed Joseph a prophet, “approximately half the people in the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have been women.”[8] This seemingly tiny thing becomes weighty in context. Including Phebe reminds the reader of experience of this other “half,” juxtaposes nicely with “The Great” Josiah Quincy, and in the process produces a more balanced representation of the past. It brings out yet another color and corner of the tapestry of the Restoration.

It takes time and effort to conceive of a more complete and whole narrative of LDS history. Academics have begun the process of a more comprehensive understanding, but we are still waiting for that more inclusive narrative to be accessible to LDS Church membership as a whole. This may seem a very simple thing and it is—it really is, but we still have miles of thread to sew.

Former Relief Society General President Julie B. Beck taught, “We study our history to learn who we are.” The more readily we all see examples of strong, faithful women, we give all more opportunities to better “know their identity, value, and importance.”[9]

As I study the lives of early women of the Restoration, I am changed. The things that I learn help me to better value the souls of those I come in contact with today and value our different experiences and contributions.

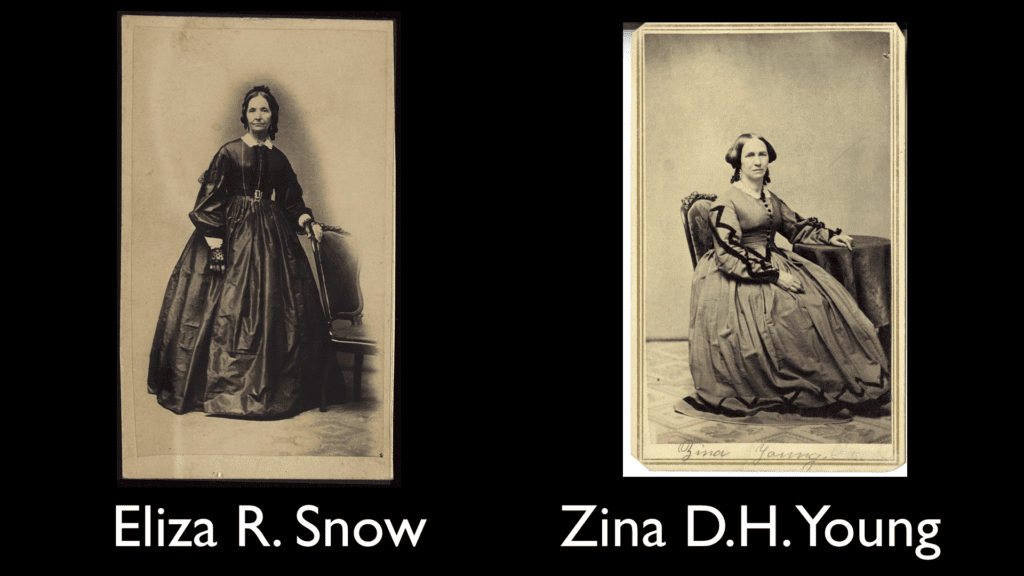

I recognize that not all women of the Restoration were painted with the same brush. These two women are emblematic of some of those differences. If we compare Eliza R. Snow and Zina D. H. Young on paper we might focus on the similarities: they were both plural wives of Joseph Smith and then Brigham Young, sister-wives living in the Lion House in Salt Lake, they both became General Relief Society presidents in Utah. We might assume they have similar fashion sense.

Yet, if we look at their paths to conversion, we could not see two more distinct women. Zina was 14 when she first saw a Book of Mormon—on a windowsill of her family’s home. She recounted, “One day on my return from school I saw the Book of Mormon, that strange, new book, lying on the window sill of our sitting-room. I went up to the window, picked it up, and the sweet influence of the Holy Spirit accompanied it to such an extent that I pressed it to my bosom in a rapture of delight, murmuring as I did so, “This is the truth, truth, truth!”[10] For Zina it was almost instantaneous and that sweet influence would stay with her.

In contrast, Eliza R. Snow’s mother and sister were baptized in 1831. Eliza met Joseph Smith and liked him, she heard the testimony of the three witnesses—“such impressive testimonies” she “had never before heard.” But she was worried that it might be a “flash in the pan” or a “hoax”—she didn’t want to be deceived. It took Eliza four years of study before “her heart was fixed” and she decided to get baptized.[11] Her heart would remain fixed.

Jill Derr commented, Eliza and Zina “were the yin and yang of nineteenth-century Relief Society: where Sister Eliza was the head of the women’s work, Aunt Zina was often said to be its heart.”[12] The church needed Eliza as much as it needed Zina.

The missionary in me desperately wants gaining a conviction of the Restoration to be as easy as it was for Zina for everyone, but the pragmatist in me knows that conversion is as distinct as we are. Sometimes we need the head and sometimes we need the heart—these differences remind me that just as there are “diversities of operations” in leadership (Doctrine and Covenants 46:16), there is no one way to be a Latter-day Saint woman and serve God. We all have something to contribute; we all belong to the body of Christ.

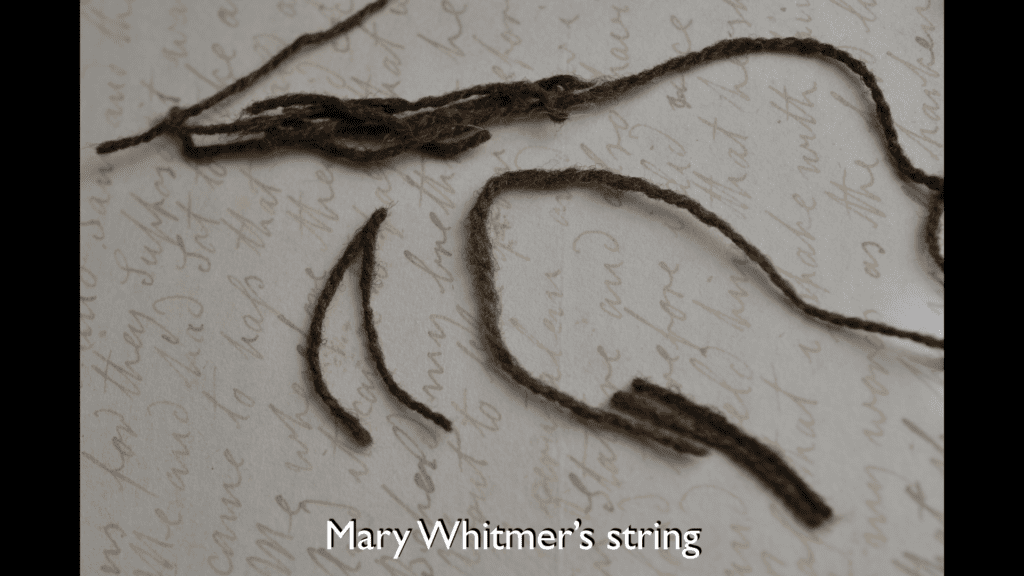

Sometimes we overlook the objects that women leave behind and the witness that comes through those objects. Mary Whitmer provided the homespun wool to tie the Book of Mormon manuscript together.

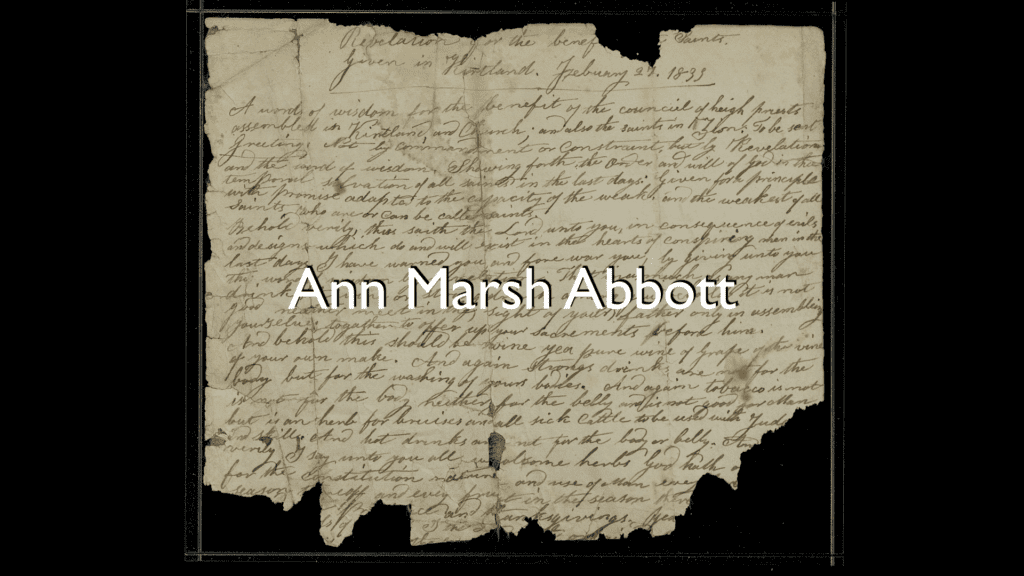

This is perhaps the only known revelation manuscript penned by a woman—Ann Marsh Abbott’s personal and well-worn copy of the Word of Wisdom.

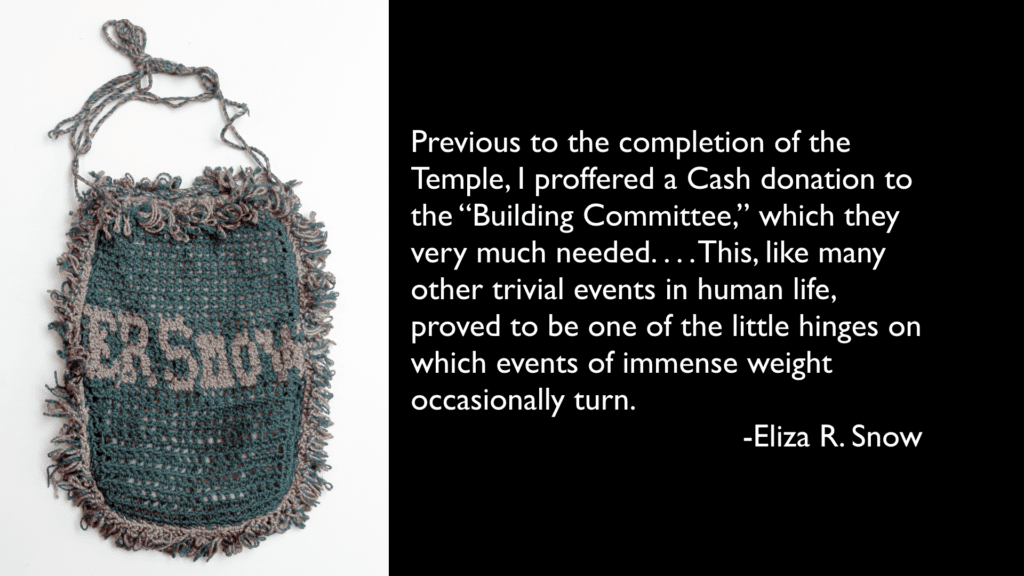

Eliza R. Snow crocheted this reticule to hold her temple donation. Early on she established a pattern of donating; “This, like many other trivial events in human life, proved to be one of the little hinges on which events of immense weight occasionally turn.” Later when she received her inheritance she donated it to the temple. The pattern had already been established.

Julie Beck argued that, “The ability to qualify for, receive, and act on personal revelation is the single most important skill that can be acquired in this life.” We learn as we see everyday individuals work out their salvation and learn to hear the voice of the Lord and apply it in their lives.

Before Mary Fielding gained another last name and paid her tithing against all odds, she was a single woman making her way in Kirtland. She, her sister Mercy, and her brother Joseph had joined the church together in Toronto and soon gathered to Kirtland. But her sister married and Mercy and her new husband were called back to Canada on a mission. Her brother Joseph was called to England leaving Mary alone in Kirtland. She wrote a letter to Mercy in fall 1837 amidst uncertainty in her personal life and chaos in Kirtland. Mary had taught school for a month, but it was not ideal and quickly coming to an end. She explained, “The time expires tomorrow when I expect again to be at liberty or without employment. But I feel my mind pretty much at rest on that subject. I have called upon the Lord for direction and trust he will open my way.” She spent the rest of the letter describing the turmoil in Kirtland as apostasy and economic uncertainty spread. Mary though it was comparable to the biblical narrative of Numbers 16 when Korah and his company rose up against Moses and Aaron—however she could not tell “whether The Lord [would] come out in a similar way or not.” (For those of us who don’t remember that bit off the top of our heads—the ground split open and swallowed up all the apostates.) In the process of writing the letter Mary was able to find a position as a governess. It was certainly not lucrative, but she was hopeful. Ironically in the post script of the letter Mary mentioned a friend who had just married a widower with five children. Hyrum Smith had also just become a widower as he lost his wife Jerusha. And two months later, on the day before Christmas Mary Fielding would marry Hyrum and instantly become a mother to five children herself.

In 1880, Desideria Quintanar de Yañez was sixty. She lived in a small Hidalgo village about 75 miles north of Mexico City. One night she dreamed of a pamphlet being printed in Mexico City—Voz de amonestación (A Voice of Warning). She sent her son, Jose Maria on what must have seemed like a wild goose chase to find the men printing the pamphlet. After hunting “for a long time” he found a Mormon elder correcting printer’s proofs for the pamphlet and expecting him to arrive. Desideria would have to continue to wait for A Voice of Warning, but the other pamphlets sent with Jose were enough for the moment. She too knew he had been successful by revelation and anticipated Jose’s return. She would become the first woman baptized a member in the mission. Though Desideria would never leave her pueblo, never reach Mexico City, let alone Salt Lake City—her faith and the clarity of the instruction she received from the Lord encourages me.

If we return to the tapestry for another moment, not all sections of the tapestry are bright and cheery. Contrasts offer depth. Some women’s experiences remind us of the oppositional nature of mortality and some of the joyful and some of the dark corners of the tapestry.

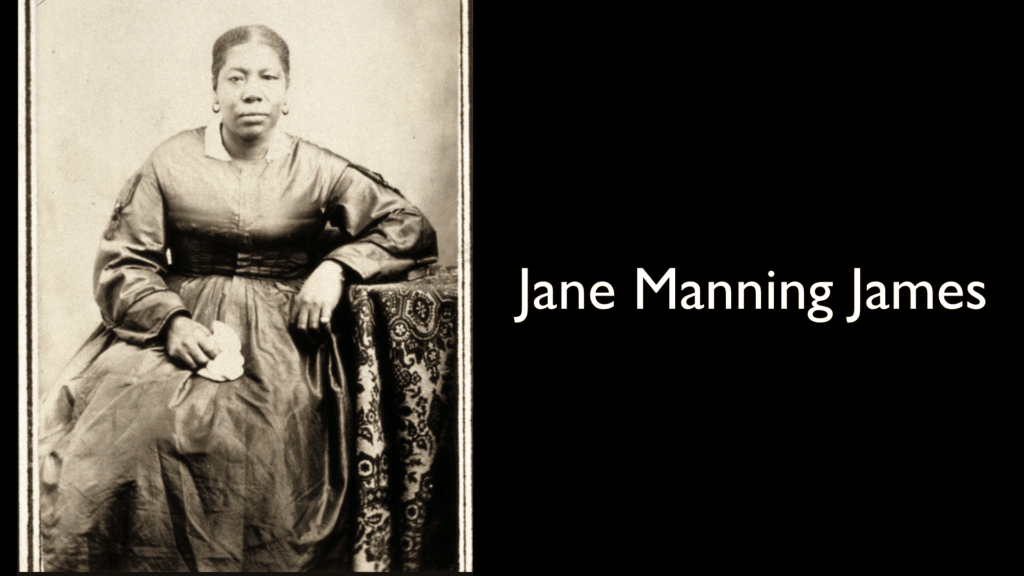

Jane Manning James and her family chose to trek the 800 miles to Nauvoo on foot after a rude ship’s captain would not let them board because they were African American. Though Jane found joy through her faith in God, her road was never easy. She and her family rejoiced to arrive in the City of the Saints, yet they were met with “hardship, trial, and rebuff.” Thankfully, Emma and Joseph welcomed them into their home.

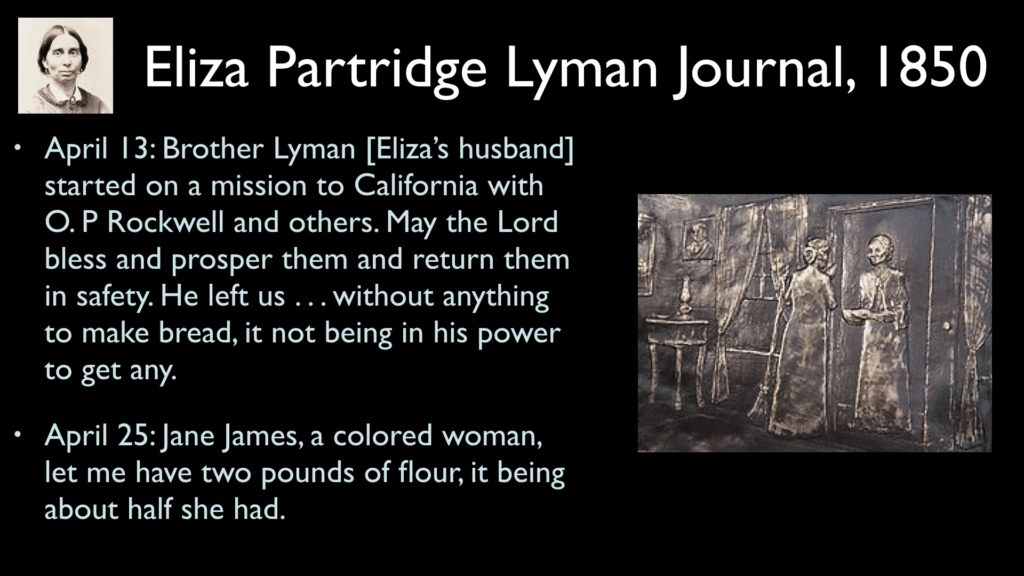

Jane emigrated to Utah with the Saints and from someone else’s journal we see a glimpse of Jane’s life in 1850. Jane shows up in a line. April 13, 1850 Eliza Partridge Lyman’s husband had just left on a mission to California. “He left [them] without any bread,” Eliza added, “It not being in his power to get any.” Certainly Eliza was in dire straits almost two weeks later when her sister Jane showed up at her door with 2 pounds of flour, “it being about half of she had.” If Jane only had 4 pounds of flour, she was not particularly stable herself, but she consecrated what she had and helped her sister.

Jane remained faithful as she was excluded from essential salvific ordinances in the temple. Yet she was not satisfied with a negative response to her petitions for those ordinances. After Elijah Able’s death she would continue to petition for temple ordinances on his behalf also. After attending a dinner which included church President John Taylor in 1884—she wrote him. In the letter we see Jane’s persuasive theological arguments reclaiming the promises of the Abrahamic covenant for her and her family. She argued, “as this is the fullness of all dispensations is there no blessing for me?” Jane’s sense of self worth, her artful theology, and persistence stands as a witness to us today. In her interview given the year of her death, she witnessed, “The Lord protects me and takes good care of me…my faith in the gospel of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is as strong today—nay it is if possible stronger—than it was the day I was first baptized. I try in my feeble way to set a good example to all.”

Really seeing the experience of others can yield empathy, if we let it. Letting go of assumptions and judgments opens the way for love and compassion.

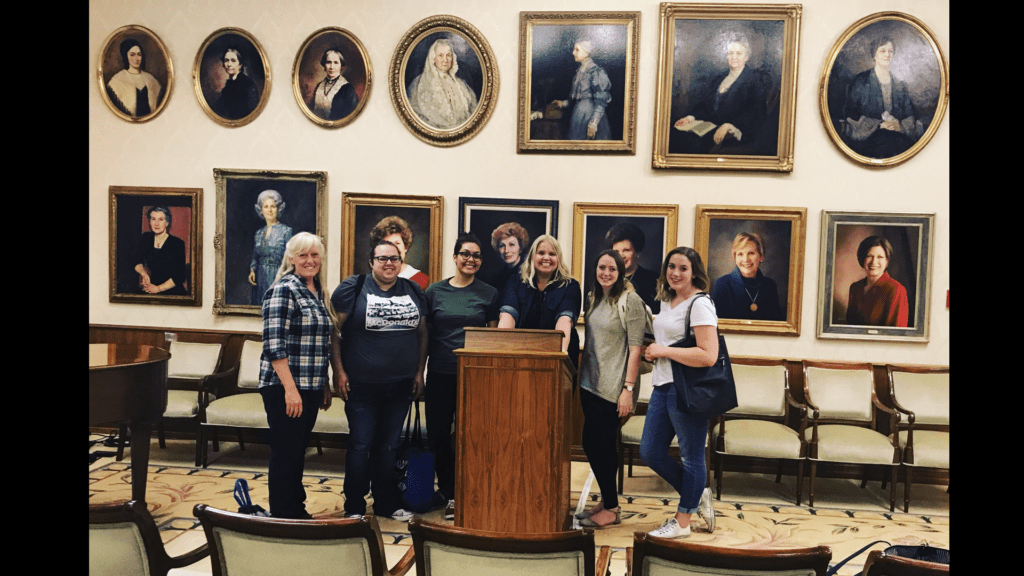

This semester I had the opportunity to teach a Women of the Restoration religion class at BYU-Idaho. It was the first time, hopefully not the last, that this class was offered. We walked through early church history from women’s perspective. We talked history, and experience, and theology through women’s sources.

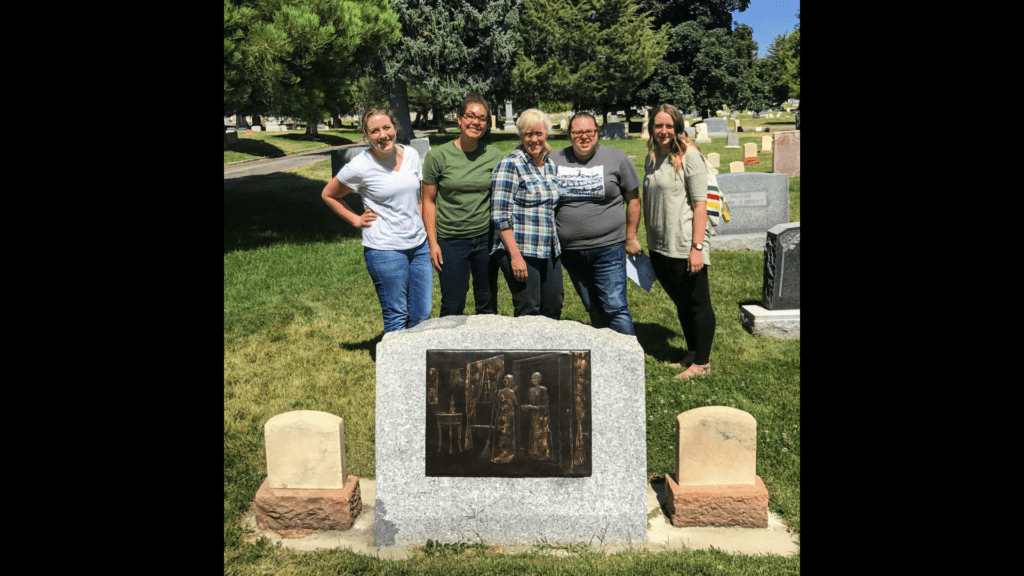

This photograph includes a few of my students as we made a pilgrimage to Jane James grave in the Salt Lake Cemetery. Though I love all my classes—well usually, this class was the highlight of my week. Though we found many similarities among us, there were also an abundance of differences. Returned missionaries, moms returning to school, those struggling to attend church, those who had never considered not going to church, converts, life-long members, students from different geographical locations, different cultural heritages, lovers of Rexburg, mild tolerators of Rexburg, and even a couple of men. I love teaching religion classes for the mix of the academic and the spiritual. Though we read and talked about academic arguments, this was always focused on the spiritual to a depth that I had not experienced in a class before. I sensed that for many of them this was a key moment. Several of the women in the class told me how they were led to the class and how they saw it as an answer to prayer. This did not mean consistent holding hands and singing kumbayah. People came to the class with different perceptions, desires, and needs.

For several, learning how to deal with hard things was key. One student detailed, “Despite the sunshiney rhetoric that is often used within the Church when discussing times of great misery, I have learned that the Lord does not require people to be happy or thankful for the difficulties they are enduring at the time…. As Mormons are so fond of saying, it takes the bad to know the good, but I believe that means truly understanding and coming to terms with how the bad makes us feel, so that we can overcome it and move on to something better.” Another student illustrated, these women “led their lives in such a way that they could stay close to Christ, even though they went through great trials.…Through these experiences their testimonies were deepened and they became more convicted in the cause of Christ.”

And for another it was very simple, she commented, “I think that the most important thing I learned is that women matter. I know that may sound cheesy, but in the world we live in, we can lose ourselves. I often wonder my worth. These women were a key component to the Church’s restoration. …I take comfort and guidance in their life stories.”

On reflection, I believe I saw the fulfillment of Julie Beck’s prophecy that as we study the past we “learn who we are.” And that “we” is both individual and collective. One student wrote, “I think this class was the first time I felt that as a woman my value in the church wasn’t just implied in the word ‘men’–I actually felt it and saw it in the examples of women we studied.” For others, reading about the lives of early Mormon women and listening to their fellow students was an exercise in empathy and stretching themselves to value and to work to understand others.

Not only women need to hear women’s stories, we all need to hear women’s stories. “The worth of souls is great in the sight of God.” (18:10) If we count ourselves disciples, we value all of the voices—all the threads making up the tapestry of the Restoration. Women’s voices are essential, but that should not be our only concern. At the risk of mixing metaphors—I will appropriate Elder Jeffrey Holland’s recent words: we need “those who speak different languages, celebrate diverse cultures, and live in a host of locations.” We need “the single…the married,” those with “large families, and…the childless.” We need “those with differing sexual attractions…those who once had questions regarding their faith and…those who still do.”[13] All the action doesn’t take place in the center. We need all the colors and shadows and all the textures of the Restoration. We need those in the center and those on the corner hem.

If we are to recognize the miraculous amidst the mundane, we need to look everywhere. The way that we tell our stories has the capacity to limit us, but it also has the capacity to expand our view and enlarge our souls. We can learn who we really are.

Q&A

Q 1. Your book is the tip of the iceberg. [Yes, I agree.] You have had opportunities to read many stories and biographies. What stories would you like most to see published, heard, that have not been told?

A 1. All of them. Is that acceptable? I know that is kind of a copout. Sorry.

Q 2. Are you working on another book in this area of expertise?

A 2. Jennifer Reeder and I at the end of last year published The Witness of Women with Deseret Book. We also just finished a manuscript, a study guide for The First Fifty Years of Relief Society. We realize that that book is a momentous achievement, but it is also pretty dense, and kind of difficult for ordinary people to be able to access. But the treasures that are in that book … and so we have worked on a study guide to help make that resource more accessible.

Q 3. When will someone tell Emma’s story with the attention it deserved?

A 3. I don’t have a good answer for that but I really hope that … I know there are some people who are working on Emma, on her story, and I hope that they are able to do the justice that she deserves.

Q 4. I feel that certain practices in the temple teach us a sacred, and less loud, less lauded power in women, but only because of its sacred nature, not because of inequality. How would you take this possible explanation as to why women are less lauded in scripture? So “Mary kept all these things and pondered them in her heart.”

A 4. I think that we certainly can talk about women’s desire sometimes to not need the spotlight as a reason for women not always consistently being central in scriptural texts, but I also think that that is a little bit of a copout. I think that scripture comes through culture. None of us are immune to the culture in which we are raised. Some of the effects of that culture are to our benefit, and some of the effects of that culture are to our detriment. I think that particularly just as I have been studying Joseph’s teaching to the Relief Society in Nauvoo, understanding the position of women, the temple is essential to understand that position of women.

I think that even though culture often dictated that men who wrote scripture were not particularly attuned to including women’s narratives, I think that should highlight for us those times when they do include women’s narratives. Nephi does not even tell us his wife’s name in his narrative, yet he does tell us in very explicit detail in 1 Nephi 5 when Sariah receives her witness that Lehi was called of God to bring them into the wilderness. And that conviction that his mother felt sticks with him thirty years later when he is writing that narrative of The Book of Mormon. And I think that it is important for us to take hold of those examples that we see and to recognize the value that is there with those examples.

Endnotes

[1] Laura Farnsworth Owen, Autobiography, CHL; Laura Owen, “Defence Against the Various Charges that Have gone Abroad,” republished in Times and Seasons 2, no. 4 (15 December 1840): 254–56; 2, no. 6 (15 January 1841): 278–80; 2 no. 7 (1 February 1841): 301.

[2] Laura Farnsworth Owen, Autobiography, CHL; Laura Owen, “Defence Against the Various Charges that Have gone Abroad,” republished in Times and Seasons 2, no. 4 (15 December 1840): 254.

[3]Augusta Joyce Crocheron, Representative Women of Deseret, a Book of Biographical Sketches to Accompany the Picture Bearing the Same Title (Salt Lake City: J. C. graham, 1884).

[4] Emmeline B. Wells, “The Jubilee Celebration,” Woman’s Exponent 20, no. 17 (15 March 1892): 132.

[5] Josiah Quincy, Figures of the Past From the Leaves of Old Journals, 3rded (Boston, 1883), pp. 376-400.

[6] Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 6.

[7] Phebe Peck to Anna Pratt, 10 August 1832, CHL.

[8] Richard E. Turley and Brittany Chapman, eds. Women of Faith in the Latter-days, Vol. 1-2, “Introduction.”

[9] Julie B. Beck, “‘Daughters in My Kingdom’: The History and Work of Relief Society,” Ensign, November 2010, 114.

[10] Zina D. H. Young, “How I gained My Testimony,” Young Woman’s Journal 4, no. 7 (April 1893): 318.

[11] Eliza R. Snow, “Sketch of My Life,” in The Personal Writings of Eliza R. Snow, ed. Maureen Ursenbach Beecher (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 2000), 8 and Eliza R. Snow, in Tullidge, Women of Mormondom, 63–64.

[12] Jill Mulvay Derr et al., Women of Covenant: The Story of Relief Society (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1992), 127.

[13] Jeffrey Holland, “Songs Sung and Unsung,” General Conference, April 2017.