Audio and Video Copyright © 2018 The Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research, Inc. Any reproduction or transcription of this material without prior express written permission is prohibited.

August 2018

Introduction: From Dust to Dust

For dust thou art, and until dust thou shalt return. Dust is a subtle but pervasive symbol in the scriptures that, in light of modern biblical scholarship, takes on added meaning. That meaning fits remarkably well with the use of dust themes in the Book of Mormon, the voice from the dust.

For the first slide of this presentation, I chose an image from LDS.org of Mary standing at the empty tomb, wondering. Behind her is the gardener, actually the Lord, freshly risen from the dust, inviting us to come unto Him and through Him also rise from the dust and enter into a covenant relationship with God. These concepts are tied to the ancient motif of dust.

Dust, soil, dirt, ashes, and earth are terms that can describe the ground beneath our feet and the remnants of life after dying, decomposing, degrading, or becoming oxidized. Dust and its relatives are the raw materials for life, with plants literally rising from the dust or earth, and all of us figuratively rising from the dust. We are created from dust, and we return to dust. This has long been recognized in the Hebrew scriptures. But science also tells us that our entire planet is formed from the dust of ancient stars. How true it is that we are of the dust.

Motifs related to dust form an important complex in ancient scripture. When understood in light of modern scholarship, they can help us better appreciate the richness of the text and also clarify some puzzling issues and problems.

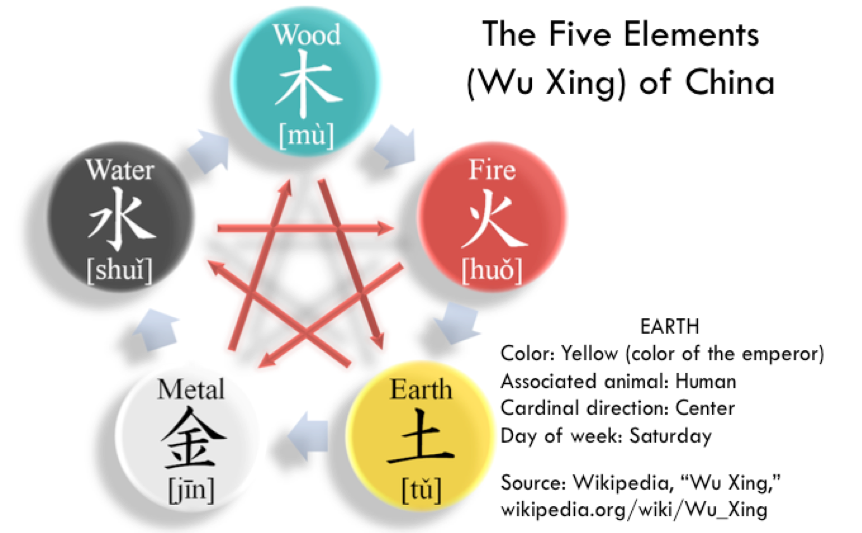

These themes are not unique to the Near East. In China, the ancient concept of the 5 elements, the Wu Xing, includes earth, metal, fire, wood, and water, each associated with a direction, a color, an animal, and a day. Interestingly, earth or dust is associated with the color yellow, which is the color of the Emperor and typically the color associated with the temple for Buddhists. The associated animal is human. The cardinal direction is the center, which we might view as if it were the axis of the cosmos that connects earth to heaven and the underworld. The day of the week is Saturday, the day in the Bible when the Creation was completed and rest could begin. Yellow is the color of dust in much of China. The yellow earth of northern China is the source of the silt that gives us the name of the Yellow River and the Yellow Sea.

The yellow dust of China can have fearsome power when combined with water, as shown in this image of hydraulic purging of a portion of the Yellow River. It can be equally fearsome when entrained in air, as shown in this approaching dust storm in Western China.

Noel Reynolds’ Work: “The Brass Plates Version of Genesis”

This study was sparked by a publication of Noel Reynolds, “The Brass Plates Version of Genesis,”[1] wherein Reynolds finds impressive links between the Book of Moses and the Book of Mormon. He offers compelling reasons why the parallels are suggestive of Book of Mormon dependency on the Book of Moses or rather, related material on the brass plates, and not the other way around.

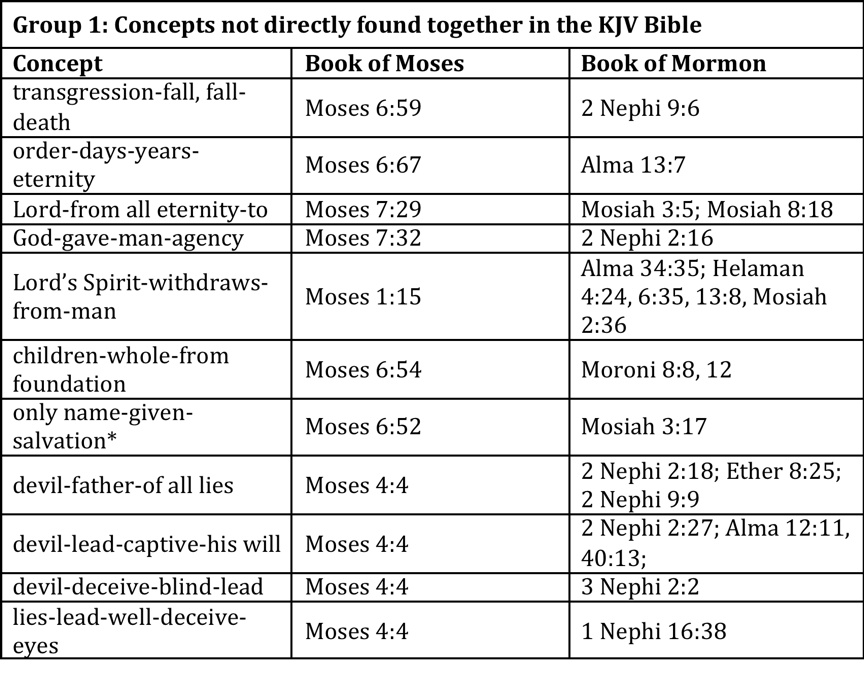

Reynolds found about 20 cases of phrases used in both the Book of Moses and the Book of Mormon that are not found in the KJV, indicating potential relationships. Some of these are intriguing and meaningful. A few are shown below:

Table 1. Summary of Reynolds’ Concepts in the Book of Moses and the Book of Mormon Without KJV Examples

Strength, Chains, and Lehi’s Farewell

Motivated by Reynolds’ work, I explored several other possible links between the Book of Moses and the Book of Mormon. Curiosity about the striking imagery of “chains of darkness” in Moses 7 led to some finds shared here, and led to three papers on the “Arise from the Dust” theme published at The Interpreter. I’ve prepared shortcuts at TinyUrl.com for these papers, so you can access them as https://tinyurl.com/arisedust1, arisedust2, and arisedust3.[2] Noel Reynolds’ paper is at tinyurl.com/arisedust4.

When I read Reynolds’ paper recently, I had been looking at some Book of Mormon passages related to the Exodus while preparing “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat,”[3] (available at tinyurl.com/arisedust8), a paper responding to a critic’s rather questionable assault on Lehi’s Trail. An Exodus-related passage I had just been reading, 1 Nephi 4:2, had a puzzling statement from Nephi: “Therefore let us go up; let us be strong like unto Moses.” My mental images of Moses and the Exodus had him as an aging man who was not particularly strong. In fact, during one scene (the Battle of Rephidim against the Amalekites, Exodus 17:8-13), he holds up his staff and needs two men to help him. Yes, it was tiring, but the scene does not speak to notable strength. The Old Testament text also does not speak about Moses’ strength. In the Pentateuch, Pharaoh is strong, the waters are strong, the Lord is strong, and Joshua is strong, but strength is not mentioned with respect to Moses. But Nephi appears to be citing something well known to his brethren. But what, I wondered. I began looking in the Book of Moses and quickly found 3 verses that could support the concept of the strength of Moses, most clearly Moses 1:25, which struck me with surprise: “Blessed art thou, Moses, for I, the Almighty, have chosen thee, and thou shalt be made stronger than many waters.” Another hit for Reynolds’ hypothesis.

Intrigued, I wondered if there might be more. Reynolds have relied on computer searches, looking for exact matches of specific words. But by looking at the broader concepts, I found 15 additional parallels consistent with what Reynolds taught.

The next example led me to the theme of dust. I was intrigued by the vivid imagery of chains of darkness or chains that veil the earth in darkness in Moses 7: 26, 57:

- “he beheld Satan; and he had a great chain in his hand, and it veiled the whole face of the earth with darkness” (Moses 7:26)

- “the remainder were reserved in chains of darkness until the judgment of the great day” (Moses 7:57)

I searched for “chains” and “darkness” in the same verse in the Book of Mormon, without success. But then I noted that in Lehi’s farewell speech in 2 Nephi 1:23, Lehi links “chains” and “obscurity” with parallelism. In Webster’s 1828 dictionary, the first definition of “obscurity” is “Darkness; want of light.” This could be a reference to “chains of darkness” in the brass plates. The term “chains of darkness” is not found in the KJV Old Testament but is found in 2 Peter 2:4 and Jude 6, so it’s not independent of the KJV. But the Book of Mormon usage may be especially interesting because it may involve a Hebraic wordplay as well: perhaps Nephi used the root ʿaphar (עפר) or ʾepher (אפר) for “dust” and ʾophel (אֹפֶל) for “obscurity.”

In Isaiah 29:4, speech whispers from the “dust” where “dust” is from ʿaphar (עפר) which occurs 15 times in Isaiah, always translated as “dust” in the KJV except in Isaiah 2:19 where it is “earth.” A closely related word is ʾepher (אפר) which can mean “loose soil crumbling into dust” or ashes. In the KJV, all 22 occurrences are “ashes,” but it is “dust” twice in the NIV. A word play with either of these possibilities could occur when coupled with the Hebrew word translated as word “obscurity” in Isaiah 29:18 in the KJV. The word is אֹפֶל, which can be transliterated as ʾophel:

ʼôphel, o’fel (from H651, ʼâphêl [אָפֵל]); meaning “dusk:—darkness, obscurity, privily, while ʼâphêl is “from an unused root meaning to set as the sun; dusky—very dark.” HALOT, 79.

It is a potentially interesting word play suggesting that Lehi or Nephi was giving poetic emphasis to dust and obscurity.

In this verse and in a major section of Lehi’s farewell speech, Lehi is clearly building on Isaiah 52:1-2, a passage that I argue may have been of great importance in Nephite religion:

- Awake, awake; put on thy strength, O Zion; put on thy beautiful garments, O Jerusalem, the holy city: for henceforth there shall no more come into thee the uncircumcised and the unclean.

- Shake thyself from the dust; arise, and sit down, O Jerusalem: loose thyself from the bands of thy neck, O captive daughter of Zion.

This beautiful passage was used by Lehi, Nephi, Jacob, Alma, Christ, and Moroni. In Lehi’s farewell, the theme of gaining promised covenant blessings in the promised land fits Lehi’s “prosper in the land” teachings (2 Nephi 1:20) and the goals of his speech. Obvious usage of this passage from Isaiah occurs as a full quotation in 2 Nephi 8:24-25 by Jacob and in 3 Nephi 20:36-37 by Christ. It is clearly being used in Lehi’s farewell, 2 Nephi 1:13-23 and in Moroni’s farewell, Moroni 10:31. It is alluded to in Jacob 3:11 (“shake yourselves … awake from the slumber of death; and loose yourselves”), in Alma 5:7 (“awake from sleep, remove bands of death”), in Alma 36 (chains, falling to the earth, a state of sleep and darkness, and arising) and perhaps in 2 Nephi 28:19 (“shake … everlasting chains”) or Alma 13:29–30 (“lifted up … bound down by the chains of hell”), among others.

The dust-related aspects of Lehi’s farewell speech include much more than the single verse that drew my attention in light of a possible relationship to the Book of Moses. His usage shows a remarkably poetic use of concepts from Isaiah 52:1-2 in 2 Nephi 1:13–23:

13 O that ye would awake, awake … and shake off the awful chains …

14 Awake! and arise from the dust.… [A] few more days and I go all the way of the earth.

21 And now that my soul might have joy in you, and that my heart might leave this world with gladness because of you, that I might not be brought down with grief and sorrow to the grave, arise from the dust, my sons, and be men, … that ye may not come down into captivity;

22 That ye may not be cursed with a sore cursing….

23 Awake, my sons; put on the armor of righteousness. Shake off the chains with which ye are bound, and come forth out of obscurity, and arise from the dust.

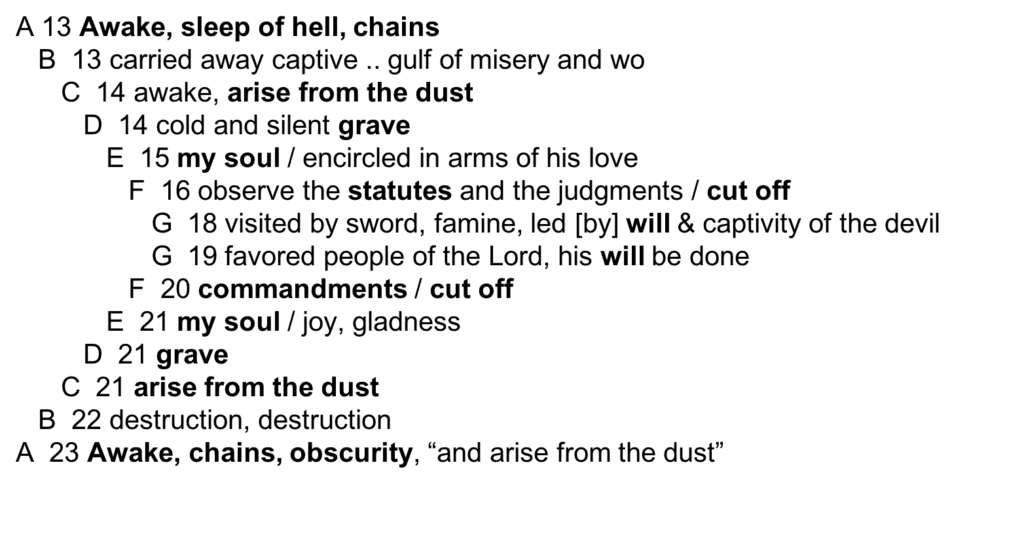

Indeed, this passage fits a fairly concise and clear 7-step chiasmus, shown here largely following the chiasmus shown by Donald R. Parry in Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon:[4]

Isaiah 52:1–2 is artfully woven into this chiasmus, emphasizing the importance of Lehi’s teaching. Interestingly, many of the Book of Mormon’s passages involving chains occur in chiasmic passages identified in Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon.

Modern Scholars on Dust and Covenants: Brueggemann and Wijngaards

Crucial insight into the significance of dust in the Old Testament comes from a paper published in 1972 by Bible scholar Walter Brueggemann, “From Dust to Kingship.”[5] Brueggemann explains that “the motifs of covenant-renewal, enthronement, and resurrection cannot be kept in isolation from each other.” Rising from the dust is related to enthronement and empowerment, with political and theological aspects.

His study began with 1 Kings 16:2, where he noted that the theme of dust is used both for the rise to power of King Baasha of Israel but also for his fall from power. The the Lord tells Baasha, “I exalted you out of the dust and made you leader over my people Israel.” But then comes the antithesis: “Behold I will utterly sweep away Baasha and his house” (American Standard Version), referring to Baasha losing his status and effectively returning to the dust.

Brueggeman also notes that the dust motif is obviously tied to the Creation, for God formed man out of the dust (Gen. 2:7) and we are dust and will return to it (Gen. 3:19). After being formed from the dust, Adam and Eve are put in charge of the Garden — given authority and responsibility, like a king and queen over the Garden — an aspect of “rising from the dust.”

Brueggeman makes several noteworthy statements in his study of the ancient dust motif:

- “Behind the creation formula lies a royal formula of enthronement. To be taken ‘from the dust’ means to be elevated from obscurity to royal office and to return to dust means to be deprived of that office and returned to obscurity.”

- “[T]o be taken from the dust means to be accepted as a covenant-partner and treated graciously; to return to the dust means to lose that covenant relation.”

- “To die and be raised is to be out of covenant and then back in covenant. So also to be ‘from dust’ is to enter into a covenant and to return ‘to dust’ is to have the covenant voided.”

His study drew heavily upon the previous work of J. Wijngaards, “Death and Resurrection in Covenantal Context (Hos. VI 2),” (tinyurl.com/arisedust10).[6]

Wijngaards argues that “dying and rising” describe the voiding and renewing of covenants. Likewise, calls to “turn” or “repent” involve changing loyalties or entering into a new covenant. Further, he states that New Testament themes of resurrection are built on Israel’s ancient enthronement rituals, and when Christ was “raised up” from the dead “on the third day,” that concept draws upon a variety of related Old Testament passages (e.g., Hosea 6:2’s reference to revival after 3 days of death). Again, OT dust motifs are grounded in covenant relationships as well as the concept of divine creation.

The Creation aspects of Lehi’s farewell speech in 2 Nephi 1 should be considered in light of Wijngaards’ work and the dust motif. Lehi deals with relevant concepts such as dust, arise, cursing, light and dark, creation (opposite is destruction), and agency (vs. captivity). Consider:

- 13: “awake from a deep sleep” (like Adam awaking from a deep sleep in Gen. 2:21).

- 23: come “out of obscurity” like coming out of the void in Genesis 1.

- Sword and the tree (visited by sword, v. 18), cut off from God’s presence (v. 20).

- “Cursed with a sore cursing” (v. 22).

- Putting on the armor of righteousness (v. 23) like Adam and Eve putting on their garments.

Creation concepts are clearly interwoven into Lehi’s speech and are one aspect of his use of the dust motif.

In addition to creation concepts, the political aspects of the dust motif may be particularly interesting in this part of the Book of Mormon, and reflect profound awareness of ancient dust motifs that may not have been recognized in Joseph’s day.

Politics and Nephi’s Use of Dust Themes

David Bokovoy, applying the political/enthronement aspects of Walter Brueggemann’s “From Dust to Kingship” to the Book of Mormon, saw the political implications of the dust theme in Nephi and Jacob’s writings.[7] He observed that Lehi’s charge to rise from the dust (and keep the covenant) is accepted by Nephi in 2 Nephi 4:28: “Awake, my soul! No longer droop in sin. Rejoice, O my heart, and give place no more for the enemy of my soul.” Further, Nephi also prays that he “may shake at the appearance of sin,” as in shaking off chains/bands per Lehi and Isaiah. This strengthens the case for Nephi as legitimate successor of Lehi, both as the political and spiritual leader. Two chapters later, Jacob, at Nephi’s request, quotes Isaiah 52:1-2. In context, Bokovoy says this helps cement Nephi’s legitimacy as ruler. He who rises from the dust is given authority and power.

Laman and Lemuel could reign if they would rise from the dust and be righteous men, as Lehi explained in 2 Nephi 1:28–29. But that honor goes to Nephi, and Lehi’s speech and Nephi’s response to it clarify that Nephi truly is the legitimate successor of Lehi. Lehi’s farewell speech and Nephi’s response may then be of vital importance in establishing the legitimacy of Nephi’s reign and of the whole Nephite enterprise versus the competing claims of Laman and Lemuel.

Redundancy or Poetry? Nephi’s Dusty Inclusio

In light of the ancient dust motif and ancient poetical tools, we can see further evidence of Nephi’s great emphasis on Lehi’s speech as we explore a Book of Mormon puzzle that the ancient dust motif helps resolve. The puzzle involves another dust-related passage, wherein the Book of Mormon quotes Isaiah 49:22–23. The puzzle is why this passage would be quoted twice by Nephi, in short order. The passage clearly has political overtones:

22 Thus saith the Lord God: Behold, I will lift up mine hand to the Gentiles, and set up my standard to the people; and they shall bring thy sons in their arms, and thy daughters shall be carried upon their shoulders.

23 And kings shall be thy nursing fathers, and their queens thy nursing mothers; they shall bow down to thee with their face towards the earth, and lick up the dust of thy feet; and thou shalt know that I am the Lord; for they shall not be ashamed that wait for me.

This is first quoted near the end of Nephi’s first book at 1 Nephi 21:22–23. Seven chapters later, it is cited again in 2 Nephi 6:6–7. Given the limited space on the plates and the difficulty of engraving, why would Nephi quote this passage twice?

In light of the ancient dust motif and modern scholarship on poetical techniques in Old Testament times, I would propose that this passage is part of the ancient Hebrew poetical technique known as inclusio, in which a common phrase or related material, often with common specific keywords, brackets the beginning and end of a portion of text. Chiasmus can be considered “recursive inclusio” with brackets within brackets within brackets. Inclusio can give special emphasis to the bracketed text and add to its meaning. Here a large dust-related inclusio highlights Lehi’s dust-related speech to set it off as a key passage in Nephite religion.

Below is the proposed structure of Nephi’s “dusty inclusio.”

A1. Isaiah on Dust Removal and (Ironic) Enthronement

Start: 1 Nephi 20:1 (Is. 48:1): Arising from the waters of Judah (baptism: washed).

End: 1 Nephi 21:22–26 (Is. 49:22–26): Kings and queens to lick the dust off the feet of the covenant people.

B. 1 Nephi 22 and 2 Nephi 1–6, including Lehi’s Farewell and Nephi’s Psalm. This passage involves themes of dust, deliverance from captivity, and redemption.

A2. Isaiah on Dust Removal and (Ironic) Enthronement

Start: 2 Nephi 6:6, quoting Is. 49:22–23 (kings licking dust from the feet)

End: 2 Nephi 8:24–25, quoting Is. 52:1–2 (“Awake, awake . . . Shake thyself from the dust, arise.”)

Here one can view baptism as a ritual of washing off sin (a type of “dust removal”) and rising from spiritual death to life. “Ironic enthronement” refers to the reversal in which gentile kings and queens descend from their thrones to the earth and then lick off the dust from the feet of the former scattered refugees who now ascend to thrones.

The opening bracket moves from washing to the licking of dust, and the closing bracket now starts with the licking of dust followed by a return to Isaiah 52:1-2, now quoted in full.

Seeing the redundant quotation of Isaiah as a deliberate dust-related inclusio around a highly-significant dust-related passage resolves the question about Nephi’s apparently wasteful and redundant duplicate quotation. The duplication via an inclusio highlights and expands upon the meaning of brackets the dust-related body, and signals the importance of related material inside. With this inclusio, arising (or being washed) from the dust is introduced as a vital and rich motif.

Similarly, the entire book of Second Nephi begins and ends with dust themes. Lehi’s speech in 2 Nephi 1 can be compared to Nephi’s closing words in 2 Nephi 33:13: “I speak unto you as the voice of one crying from the dust: Farewell until that great day shall come.” Various theories have been proposed for why Nephi split his work into two books, but one issue arising from consideration of the dust motif is that Lehi’s speech coupled with Nephi’s psalm (2 Nephi 4) support Nephi’s divine commission as a prophet and as king, in parallel to Lehi’s divine commission as prophet and leader in the opening chapters of 1 Nephi. In any case, the political and spiritual implications of Lehi’s farewell speech may have been of pivotal importance in Nephi’s mind, and thus is given emphasis not only through a dust-related inclusio, but also through setting it off as the beginning his second book.

The Complex of Dust Themes

At this point we have encountered a complex of concepts related to the dust motif. This includes dust as a symbol of death, decay, chaos, and the raw materials of God’s Creation. We also have rising from the dust related to keeping covenants, resurrection, receiving power and authority, enthronement, and salvation. Further, dust, like chains of captivity, needs to be shaken off, or washed or even licked off.

Related passages sometimes involve:

- Shaking such as shaking off of dust, chains, bands, etc.

- Repentance and cleansing.

- Singing and rejoicing. Those who arise from the dust and are freed from chains of darkness often break out into song or rejoicing.

- Rising (Hebrew quwm in Is. 52) is an important aspect of many dust-related passages, where the Hebrew word can also mean establish, stand, ascend. Along with standing and rising, references to feet can also play a role.

- Sitting (in authority, on a throne) is also part of the dust complex.

- Putting on robes of authority (enthronement) is an important aspect with both spiritual and political aspects.

- Encircling (chains, bands vs. robes/arms of the Lord). You can be encircled by the robes or arms of the Lord, or encircled by the chains and bands of death. It’s one or the other and it’s your choice, like the doctrine of the 2 ways we find in 2 Nephi 2.

- Resurrection

- Exaltation, enthronement

In any case, dust removal is the goal for humanity, and the Savior is the one who makes that possible.

Isaiah has other dust-related passages relevant to our discussion, such as:

- Isaiah 26:19: “Thy dead men shall live, together with my dead body shall they arise. Awake and sing, ye that dwell in dust: for thy dew is as the dew of herbs, and the earth shall cast out the dead.”

- Isaiah 61:3: “To appoint unto them that mourn in Zion, to give unto them beauty for ashes [dust], the oil of joy [anointing] for mourning, the garment of praise [royal robes] for the spirit of heaviness; that they might be called trees of righteousness, the planting of the Lord, that he might be glorified.”

For related details, see the discussion of chaos and creation themes in Avraham Gileadi, The Literary Message of Isaiah (San Diego, Hebraeus Press, 1994, 2012). This book examines the evidence for the literary unity of Isaiah, a study that began after noticing that Isaiah 52 and 53 on the enthronement of Zion were closely related to the fall to the dust of the King of Babylon in Isaiah 13 and 14, and that finding led to significant new discoveries that support the unity of Isaiah. Gileadi’s work incidentally helps resolve the apparent problem of passages from a later hypothetical Deutero-Isaiah being available on the brass plates before the Exile.

Dust Removal

Let’s return to the issue of dust removal. This seems to be a key theme of the Book of Mormon. In addition to shaking off dust or chains in order to arise from the dust, dust can be removed with washing and related means. Thus we can have (1) washing of the feet, which, like rising from the dust, can be viewed as a washing to remove dust, a symbol of cleansing and receiving authority or honor. We can also consider (2) licking the dust off the feet in Isaiah 49:23, and (3) washing eyes anointed with clay in John 9:6–7, where Christ heals a blind man. Here clay, like dust, is a symbol of the Creation or God’s creative power, according to Irenaeus. A number of commentators rejected that suggestion, but new evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls suggests Irenaeus was correct and that clay was used as a symbol of God’s creative power among ancient Jews. For details, see Daniel Frayer-Griggs, Journal of Biblical Literature.[8]

If washing eyes anointed with clay is linked to God’s creative work, this may shed insight on the story of Enoch in the Book of Moses who became a seer when God told him to anoint his eyes with clay and wash them (Moses 6:35–6). He receives this gift that allows him to see things that others cannot. The washing off of dust or clay, like the removal of sin and the conquering of chaos, seems to lead to the receipt of divine gifts. Is dust removal an aspect of baptism as one rises from the waters of chaos and death? I would suggest that it is, and that the covenant and ritual of baptism can also be considered in light of dust motifs.

King Benjamin’s Speech

The covenant-based elements of the complex of dust themes may help us better appreciate some scenes in the Book of Mormon, such as King Benjamin’s speech, a beautiful covenant-making episode. Near its beginning in Mosiah 2:25–26, King Benjamin speaks of dust several times, telling the people that they are less than the dust of the earth and that he, too, is dust and must perish soon:

Ye cannot say that ye are even as much as the dust of the earth; yet ye were created of the dust of the earth…

And I, even I, whom ye call your king, am no better than ye yourselves are; for I am also of the dust … and am about to yield up this mortal frame to its mother earth.

Following his speech, the people are ready to make a covenant in Mosiah 4:1–2. Their willingness to repent and enter into the covenant appears to be signaled by what will become a characteristic of Book of Mormon peoples at key spiritual moments:

[H]e cast his eyes round about on the multitude, and behold they had fallen to the earth, for the fear of the Lord had come upon them.

And they had viewed themselves in their own carnal state, even less than the dust of the earth. And they all cried aloud with one voice, saying: O have mercy, and apply the atoning blood of Christ that we may receive forgiveness of our sins….

The crying with one voice suggests their vocal response was scripted or orchestrated in some way. Might the falling to the earth also be a ritualized response to spiritual events in Nephite culture, influenced by dust motifs? It may be worth considering.

Falling to the earth can have several possible symbolic meanings, including:

- Physical death

- Spiritual death (falling away from God)

- Rebellion, sin, breaking the covenant

- Losing power, authority, life

- Destruction

Symbols that stand in contrast to falling to the earth can include rising, standing, resurrection, revival, receiving power, enthronement, covenant making and covenant keeping. Various scenes with falling to the earth may well be considered in light of such possibilities, especially when key words from the dust motif are employed or perhaps even emphasized such as “arise.”

Abinadi vs. the Priests of King Noah

Another prominent Book of Mormon scene where dust motifs may play a significant role and help resolve puzzles in the text is the encounter of the prophet Abinadi with the wicked priests of King Noah. The priests want to entrap the annoying prophet and find legal accusations against him. But their approach puzzled me for years. Of all the tricky questions they could toss at Abinadi, why do they ask him to explain “how beautiful upon the mountains are the feet” from Isaiah 52:7-10?

20 And it came to pass that one of them said unto him: What meaneth the words which are written, and which have been taught by our fathers, saying:

21 How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings; that publisheth peace; that bringeth good tidings of good; that publisheth salvation; that saith unto Zion, Thy God reigneth;

22 Thy watchmen shall lift up the voice; with the voice together shall they sing; for they shall see eye to eye when the Lord shall bring again Zion;

23 Break forth into joy; sing together ye waste places of Jerusalem; for the Lord hath comforted his people, he hath redeemed Jerusalem;

24 The Lord hath made bare his holy arm in the eyes of all the nations, and all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of our God?

Their goal is to refute, neutralize, accuse and perhaps even execute this enemy. Why use this route? Who cares what that passage means? Why do they care? Why make that a focus for their defense and counterattack?

In light of the complex of dust motifs, however, we can make a proposal: If Isaiah 52 were a foundational part of Nephite religion, as suggested by Nephi’s dusty inclusio, then the “feel good” part of Is. 52 with its beautiful feet, good tidings, salvation, joy, and breaking out in song might seem like an effective rebuttal to Abinadi’s gloom and doom. If a key part of Nephite religion emphasizes good news, why should we accept the depressing message of Abinadi? From their perspective, this undoubtedly seemed like an effective argument.

What’s especially puzzling, though, is Abinadi’s response.

At first glance, Abinadi seems to give an odd, rambling answer that doesn’t address the puzzling question before him. But if Isaiah 52 was a pivotal passage in Nephite religion whose abuse or misinterpretation truly deserved and required a thorough reply to counter profound apostasy, then we can see that his answer lays a foundation to overthrow the priests’ deceptive misapplication. His treatment step by step covers the nature of the law and its purpose, the inadequacy of the law for salvation and the need for reconciliation through the Messiah, and the need for repentance and following God, resulting in being raised by God. Only when we understand and accept the Messiah can we have cause for rejoicing. Those whose feet will become beautiful on Mount Zion are those who heed Isaiah 52:1–2 through shaking off the dust, repenting, arising, receiving the grace of the Messiah and putting on the beautiful garments of the Lord. Their feet shall be beautiful and firmly established, standing on Mount Zion, supporting saints with cause to rejoice and sing praises to their Redeemer.

Abinadi’s answer, long as it is, is a logical and inspiring response that exposed the ignorance and apostasy of the priests and turned their question to their own shame and need to repent. And it would profoundly affect generations of Nephites through the instrumentality of a new convert among the wicked priests, Alma the Elder.

Dusting off Alma 36

Knowledge of dust motifs may be useful in better understanding one of the most interesting poetical passages in the Book of Mormon, the grand chiasmus of Alma 36. In spite of the impressive evidence that Alma 36 is an artfully crafted chiasmus, there are legitimate questions about a couple of seemingly “loose” portions on both halves of the chiasmus where only a few words are selected among many others. Critics as well as faithful Mormons can ask fair questions about those loose portions. But some of that looseness may tighten up a bit when we consider the added parallelism that is present in light of dust motifs.

Today I will only address one of several issues present in these loose sections: the significance of falling to the earth, which is a sign of covenant breaking and death. Contrasting concepts include arising and regaining life, regaining use of limbs, and entering into the covenant.

Look at the related dust themes in the first “sloppy” portion of Alma 36:

7 earth did tremble beneath our feet … fell to the earth … fear of the Lord

8 …the voice said unto me, Arise. And I arose and stood up

9 …destroyed … seek no more to destroy the church of God

10 … I fell to the earth … three days and three nights …

11 …destroyed…destroy no more … fear … destroyed … fell to the earth and did hear no more

Note that falling to the earth is mentioned three times. His spiritual death is described in ways that mimic physical death: collapse to the earth, unable to move, and three days and three nights, like the three days in the grave of Hosea 6:2, the topic of Wijngaard’s study that helped establish modern knowledge of ancient dust motifs in the Old Testament.

The corresponding “loose” portion on the other side of the pivot point, where Alma accepts Christ and everything changes, uses language that have interesting relationships with the passage we just saw:

22 Yea, methought I saw, even as our father Lehi saw, God sitting upon his throne, surrounded with numberless concourses of angels, in the attitude of singing and praising their God; yea, and my soul did long to be there.

23 But behold, my limbs did receive their strength again, and I stood upon my feet, and did manifest unto the people that I had been born of God.

24 Yea, and from that time even until now, I have labored without ceasing, that I might bring souls unto repentance; that I might bring them to taste of the exceeding joy of which I did taste; that they might also be born of God, and be filled with the Holy Ghost.

25 Yea, and now behold, O my son, the Lord doth give me exceedingly great joy in the fruit of my labors;

26 For because of the word which he has imparted unto me, behold, many have been born of God, and have tasted as I have tasted, and have seen eye to eye as I have seen; therefore they do know of these things of which I have spoken, as I do know; and the knowledge which I have is of God.

In light of the covenant-related aspects of the dust motif and the various meanings of falling to the earth, what could be a better opposite for falling to the earth than being born again? In opposition to the triple mention of falling to the earth, here its opposite, being born of God, is also mentioned three times. Other contrasts include standing, limbs regaining strength, tasted + seen + spoken (signs of life), singing, viewing a throne, joy, etc. There is sophisticated and artful parallelism involving dust themes that don’t seem to have been adequately considered, but which may not reflect a single, linear chiastic structure. Rather, one can argue that there are multiple strands of dust-related themes interwoven with the chiastic backbone, with complex but interesting patterns that may require further research. At this point, some tentative conclusions can be offered:

- The “loose sections” in vv. 5–15, 23–26 have much more parallelism than just 4 words identified by Welch.

- Multiple strands employing dust-related themes appear to be interwoven.

- Alma’s contrast between falling to the earth and being born again and freed from the chains of death suggests awareness and deliberate use of dust-related concepts from Nephi, Isaiah, etc.

- There may be much more structure and craftsmanship than we realized in passages often said to be too weak to be real chiasmus.

The paper exploring this rather speculative issue is available at The Interpreter via this shortcut: tinyurl.com/arisedust3.

Christ’s Use of Isaiah 52

Another fascinating application of Isaiah 52 and related dust motifs occurs in 3 Nephi 20, where Christ quotes Isaiah 52:1–2 and other verses from Isaiah 52 and elsewhere. This occurs right after the major miracles of 3 Nephi 19 following baptism and receipt of the Holy Ghost in a miraculous scene with angels descending, divine fire, and miraculous events with Christ. Christ continues the covenantal theme as He breaks and blesses bread, gives wine, all miraculously provided, filling those present (vv. 3-10). But first, he commands them to arise. “And they arose up and stood” (v 2).

He then speaks of fulfilling ancient covenants with Israel, their gathering and their lands of inheritance (10-15). Then He says that “I will establish my people” (21), “this people will I establish in this land” (22), and says a “prophet shall … God raise up” (23). These all may have used or been related to the Hebrew word quwm that is the root behind “arise” in Isaiah 52 that can also mean “establish.”

Further teachings follow:

- “The Father having raised me up unto you first,” to turn sinners away from iniquities (renewing covenant, 26)

- “Break forth into joy — Sing together” (34)

- “Awake, awake again, and put on thy strength” (36)

- “Shake thyself from the dust; arise, sit down” (37)

- “How beautiful … are the feet …” (40)

- Restoration, gathering, fulfilling covenant (vv. 41-46)

Christ emphasizes the fulfilling of the Lord’s covenants, His mission in turning us from our sins, the cause we have to rejoice, but also the need to awake, shake, arise, and be enthroned. This is far more than a rallying cry to encourage the Nephites to rebuild their fallen cities, but encouragement to rebuild fallen lives and rise from the dust spiritually and literally, ultimately receiving all the promised blessings in and from the covenants of the Lord. The Savior’s repetition of Isaiah 52:1–2, calling the Nephites and us to rise from the dust and sit down, is motivated by His love and grace, seeking to help us enter the Father’s presence and be enthroned through the grace of Christ.

Moroni’s Third & Final Closing, Moroni 10

The final reference to Isaiah 52’s dust theme occurs in the last few sentences of the Book of Mormon as Moroni finally closes his text. Twice previously he thought he was done, but his ending was not clear and impactful. On this third try, it’s different, as Grant Hardy explores in detail in his Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide.[9] See also articles at Book of Mormon Central and the Maxwell Institute on Moroni’s farewells (tinyurl.com/arisedust14, 15, and 16).[10] In applying Isaiah 52, which he may have recently encountered with new insights as he worked with the account on Nephi’s small plates, Moroni seems to have found the ideal way to close the text, and in continues his pattern in drawing upon numerous teachings from the small plates, alluding to details there, making Joseph Smith’s translation all the more miraculous for those who claim he fabricated it, for the writings of Nephi and Jacob were dictated after Moroni’s close, with extensive citations of passages and teachings there, passages that had not yet been dictated as Joseph looked into his hat (tinyurl.com/arisedust18). Interestingly, Moroni’s final farewell follows language in both Nephi’s and Jacob’s farewells.

- 31 And awake, and arise from the dust, O Jerusalem; yea, and put on thy beautiful garments, O daughter of Zion; and strengthen thy stakes and enlarge thy borders forever, that thou mayest no more be confounded, that the covenants of the Eternal Father which he hath made unto thee, O house of Israel, may be fulfilled.

- 32 Yea, come unto Christ, and be perfected in him, and deny yourselves of all ungodliness; and if ye shall deny yourselves of all ungodliness and love God with all your might, mind and strength, then is his grace sufficient for you, that by his grace ye may be perfect in Christ….

- 33 [T]hen are ye sanctified in Christ by the grace of God, through the shedding of the blood of Christ, which is in the covenant of the Father unto the remission of your sins, that ye become holy, without spot.

- 34 And now I bid unto all, farewell. I soon go to rest in the paradise of God, until my spirit and body shall again reunite, and I am brought forth triumphant through the air, to meet you before the pleasing bar [or rather, the Early Modern English term pleading bar as Royal Skousen suggests[11]] of the great Jehovah, the Eternal Judge of both quick and dead. Amen.

The themes applied here include covenant keeping and fulfilling, sanctification, gathering, cleansing, resurrection, judgment, and enthronement. Closing the “voice from the dust” with these words reflects a profound understanding of the meaning of the dust motifs and the core issues of Nephite religion and the original and restored Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Conclusion

The Book of Mormon artfully employs an ancient complex of themes associated with the motif of dust, especially Isaiah 52:1–2. Both political and spiritual applications are appropriately and meaningfully applied.

Modern scholarship on this ancient theme gives us tools to better understand rich and subtle meanings in a variety of areas, such as:

- Messages from Nephi and Lehi, and Nephi’s rightful reign

- Further relationships to the Book of Moses & brass plates

- The chiastic parallelism of Alma 36 (and other chiastic passages with chains)

- The scene of Abinadi vs. Noah’s priests

- King Benjamin’s speech and Nephite swooning

- Covenantal objectives of Christ and Moroni

- The pivotal role of Isaiah 52 in Nephite religion.

- The Book of Mormon is an ancient voice from the dust.

- The Book of Mormon goal to help us rise from the dust and follow the Savior.

The Book of Mormon’s authentic ancient nature is repeatedly manifest in the appropriate and accurate way the complex of dust motifs is applied. There is much more that needs to be explored, but I hope this will lay a foundation of some kind that might be helpful to other students of the Book of Mormon.

Finally, I’d like to return to the image of a puzzled Mary standing at the tomb, from which the Messiah has already risen from the dust. She is beholding miraculous evidence for the greatest event in history, and yet misunderstands its significance. In a way, this is like many of us as we encounter the Book of Mormon, the miraculous text that gives evidence for the Restoration and the reality of the Messiah and his Resurrection and grace. Just as Mary wonders if the body is missing because someone has improperly removed it, perhaps by a questionable gardener, perhaps an act of malfeasance or even a crime, so we too can look at the book and its evidence and mistake it as a fraud, a deception, and as little more than a garden-variety product of 19th century religious zeal from a con-man.

Mary did not at first recognize the gardener behind her and perhaps suspected him of a possible violation of rules and laws or a deceptive act, even after hearing His voice the first time. It was it is only when she listened again, recognizing a familiar voice, that she turned and could grasp – literally, in her case, per the JS translation – a whole new body of evidence for a miracle beyond anything she expected. When we encounter but misunderstand the Book of Mormon, it is only when we listen to that voice from the dust again and turn to the source of that voice that we can hear its divine message and move toward it, finding ourselves embraced by the arms of Christ’s love, clasped in a covenant relationship. That voice from the dust testifies that God is not dead, that His son lives, that He speaks to us through this sacred volume, and that He calls us to follow him, to rise from the dust, to shake off the chains that bind us, to put on robes of righteousness, to follow Him and sit down with Him in the presence of the Father. May we all arise from the dust and pay more attention to the miraculous message of the voice from the dust, the Book of Mormon.

Thank you.

References

[1] Noel Reynolds, “The Brass Plates Version of Genesis,” in John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks, eds., By Study and Also by Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, 27 March 1990, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 2:136–173; http://publications.maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/fullscreen/?pub=1129&index=6.

[2] Jeff Lindsay, “‘Arise from the Dust’: Insights from Dust-Related Themes in the Book of Mormon (Part 1: Tracks from the Book of Moses),” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 179–232; http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/arise-from-the-dust-insights-from-dust-related-themes-in-the-book-of-mormon-part-1-tracks-from-the-book-of-moses/; Jeff Lindsay, “‘Arise from the Dust’: Insights from Dust-Related Themes in the Book of Mormon, Part 2: Enthronement, Resurrection, and Other Ancient Motifs from the ‘Voice from the Dust,’” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 233-277, http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/arise-from-the-dust-insights-from-dust-related-themes-in-the-book-of-mormon-part-2-enthronement-resurrection-and-other-ancient-motifs-from-the-voice-from-the-dust/; Jeff Lindsay, “‘Arise from the Dust’: Insights from Dust-Related Themes in the Book of Mormon (Part 3: Dusting Off a Famous Chiasmus, Alma 36),” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 295-318; http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/arise-from-the-dust-insights-from-dust-related-themes-in-the-book-of-mormon-part-3-dusting-off-a-famous-chiasmus-alma-36/.

[3] Jeff Lindsay, “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Map: Part 1 of 2,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 19 (2016): 153-239; http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/joseph-and-the-amazing-technicolor-dream-map-part-1-of-2/.

[4] Donald R. Parry in Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Maxwell Institute, BYU, 2007), see chiasmus for 2 Nephi 1:13–23; free download at https://tinyurl.com/arisedust7.

[5] Walter Brueggemann, “From Dust to Kingship” (Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft, 84/1 (1972): 1–18.

[6] J. Wijngaards, “Death and Resurrection in Covenantal Context (Hos. VI 2),” Vetus Testamentum 17, Fasc. 2 (April 1967): 226–239; http://www.jstor.org/stable/1516837 or https://tinyurl.com/arisedust10.

[7] David Bokovoy, “Deutero-Isaiah in the Book of Mormon: A Literary Analysis (pt. 1),” When Gods Were Men, Patheos.com, April 29, 2014; http://www.patheos.com/blogs/davidbokovoy/2014/04/deutero-isaiah-in-the-book-of-mormon-a-literary-analysis-pt-1/, also available at https://tinyurl.com/arisedust5. See also David Bokovoy, “Deutero-Isaiah in the Book of Mormon: A Literary Analysis (pt. 2),” When Gods Were Men, Patheos.com, April 30, 2014; http://www.patheos.com/blogs/davidbokovoy/2014/04/deutero-isaiah-in-the-book-of-mormon-a-literary-analysis-pt-2/, also available at https://tinyurl.com/arisedust13.

[8] Daniel Frayer-Griggs, Journal of Biblical Literature, 132/ 3 (2013): 659-670; https://www.jstor.org/stable/23487892 and tinyurl.com/arisedust6.

[9] Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), Kindle edition, Chapter 9, “Strategies of Conclusion.” Also see Bokovoy, “Deutero-Isaiah in the Book of Mormon: A Literary Analysis (pt. 2),” tinyurl.com/arisedust13.

[10] “Why Did Moroni Comment So Much Throughout Ether?,” Book of Mormon Central, Nov. 30, 2016; https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/content/why-did-moroni-comment-so-much-throughout-ether or https://tinyurl.com/arisedust14; “Why Did Moroni Write So Many Farewells?,” Book of Mormon Central, Nov. 17, 2016; https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/content/why-did-moroni-write-so-many-farewells or https://tinyurl.com/arisedust15; and Mark D. Thomas, “Moroni: The Final Voice,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, 12/1 (2003): 88–99, 119–20; https://publications.mi.byu.edu/fullscreen/?pub=1402&index=9 or https://tinyurl.com/arisedust16.

[11] Royal Skousen, “The Pleading Bar of God,” Insights 24, no. 4 (2004): 2-3; http://criticaltext.byustudies.byu.edu/pleading-bar-god or https://tinyurl.com/arisedust17.