Presentation by Steve Densley, Jr.

Transcript

[Steve Densley, Jr.]

What has been proven to you?

I’d like you to consider, what kinds of things would you say have been proven to you?

- How were they proven?

- Would you say that you are convinced that the Church is true?

- If so, do you think it would be good to try to convince others that the Church is true?

- Not that we should fight with people or “Bible-bash.”

- But should we offer reasons that people may find to be convincing?

As we think about the kinds of things we may want to prove, I wonder if we often set the bar too high.

“knowing” without seeing

I recently heard a Utah attorney relate how he was reading to his son in the backyard one evening when his son said, “Dad, do you know what I don’t believe in?” “What’s that?” his dad asked. “Crickets.” The father thought this was an odd statement because they could hear crickets all around them. “Why is that son?” “Because I’ve never seen one,” the boy said. So even though there was evidence of crickets all around him, and even though the boy had clearly heard others speak of crickets, the son chose not to believe in them because he had not seen them.

The idea that a person cannot really “know” something unless they have seen it seems to be increasingly pervasive in our society.

“Knowing” spiritual things

This may explain what I’ve noticed as an increasing discomfort among members of our Church with saying “I know the Church is true.” I used to commonly hear people in testimony meeting say they “know the Church is true beyond the shadow of a doubt,” More recently, I heard a young woman bear her testimony in church and stop herself mid-sentence from saying “I know the church is true” and instead said, “I believe the church is true.” She seemed to sense that there was something wrong with her saying she “knew” it rather than that she “believed” it, and she may have heard adults around her expressing the same concern.

Some people may be troubled by the assertion that someone could “know” that something of a religious nature is true. They may be worried about appearing judgmental, not wanting to suggest what others should think or do. They may hesitate to state they know the Church is true because of the responsibility that comes with that commitment. Some may say “I have a testimony that the Church is true,” or stated in different terms, “I have faith … but I don’t want to suggest that I can prove it to others.”

Of course, the girl should be commended for bearing her testimony with sincere words rather than merely repeating what she heard others say. However, I wonder if she may have had unrealistically high expectations for where the depth and breadth of her knowledge needed to be before she could say, with confidence, “I know.”

Do you recognize this man?

How many of you know who this is?

If I were to say, “I know that Columbus lived,” would it be incorrect? It might sound odd to say since no one doubts it. But people would probably not doubt the truth of the statement. Yet I personally have no evidence to support this statement other than the testimony of others.

By contrast, my testimony of the church is based not only upon the testimony of others, but also upon my own experience with applying gospel principles, archeological evidence, word studies, experience with the Holy Ghost, and more. So why are some people who may otherwise believe in the miraculous uncomfortable when I say I know Joseph Smith had a set of golden plates, but would not question me if I say I know that Columbus lived?

One possible reason is that in modern society, we are relentlessly bombarded with messages that matters of religion should not be imposed on others, and, while we may hold sincere beliefs, we should not suggest that others believe as we do.

Another reason is that the proposition that Columbus lived is universally accepted. One would risk being thought a crackpot if one were to go around stating that Columbus is a mythical figure.

Another, perhaps related reason, is that very little is demanded of those who believe that Columbus lived. However, to state that the Book of Mormon is true or that Joseph Smith was a prophet is to cross a line. On one side of the line, you can go on living as you have. But once you cross that line, you will need to change. You will need to start doing some things and give other things up, such as time, money, and perhaps some personal practices. You may need to change your eating habits and you may lose some or all of your friends. The stakes are much higher.

In fact, it may be said that if the matter of the truthfulness of the Church were put to a jury, no one could sit on that jury as they would be biased since each of them has a personal stake in the outcome of the litigation.

—Incidentally, this picture hangs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and is captioned “Portrait of a Man, Said to be Christopher Columbus” Although you might have felt confident that this painting depicts Christopher Columbus, art historians aren’t so sure.

Knowing that you know

In any event, the young girl who felt uncomfortable saying “I know the Church is true,” is in good company. Elder Douglas L. Callister told the following story:

When the 23-year-old Heber J. Grant was installed as president of the Tooele Stake, he told the Saints he believed the gospel was true. President Joseph F. Smith, a counselor in the First Presidency, inquired, “Heber, you said you believe the gospel with all your heart, … but you did not bear your testimony that you know it is true. Don’t you know absolutely that this gospel is true?”

Heber answered, “I do not.” Joseph F. Smith then turned to John Taylor, the President of the Church, and said, “I am in favor of undoing this afternoon what we did this morning. I do not think any man should preside over a stake who has not a perfect and abiding knowledge of the divinity of this work.”

President Taylor replied, “Joseph, Joseph, Joseph, [Heber] knows it just as well as you do. The only thing that he does not know is that he does know it.”

Within a few weeks, that testimony was realized, and young Heber J. Grant shed tears of gratitude for the perfect, abiding, and absolute testimony that came into his life.

Definitions: Know, True, Church

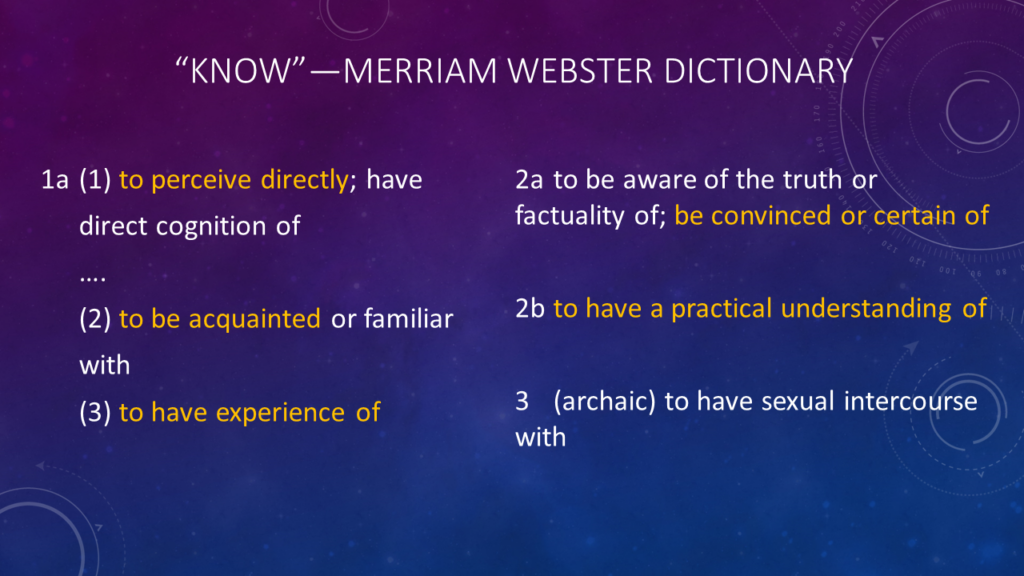

The discomfort some people experience in saying or hearing others say that “know the Church is true” may lie in the definitions of these words. The word “know” can mean a variety of things. It can mean that a person has perceived the thing directly, that they are acquainted with it, that they have experience with it, that they have a practical understanding of it, or that they are convinced or certain of it.

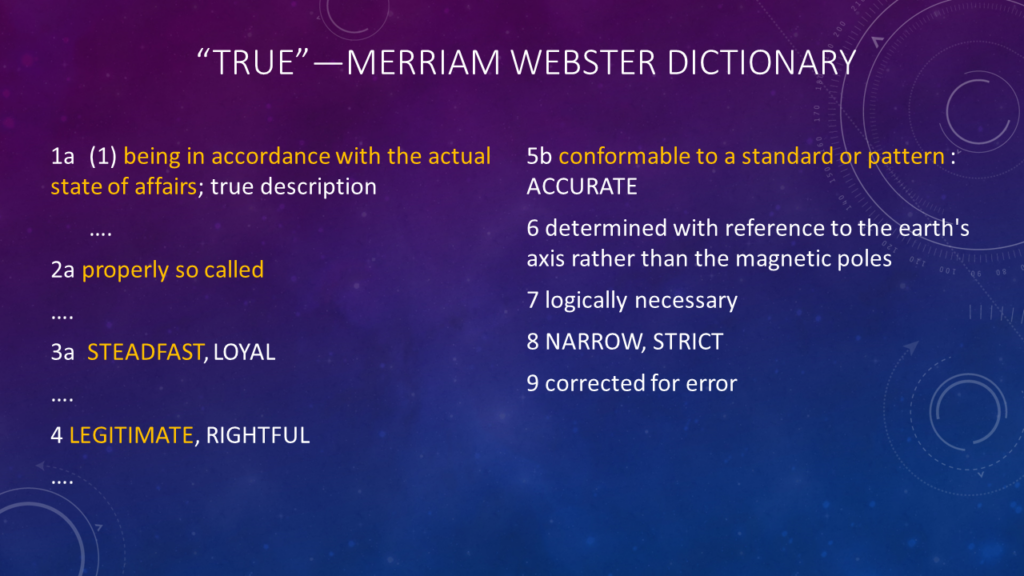

Regarding the word “true,” the dictionary lists nine different entries, with multiple sub-entries, and among the listed meanings are “being in accordance with the actual state of affairs”; “properly so called”; “steadfast”; “legitimate”; and “conformable to a standard or pattern ”. [4]

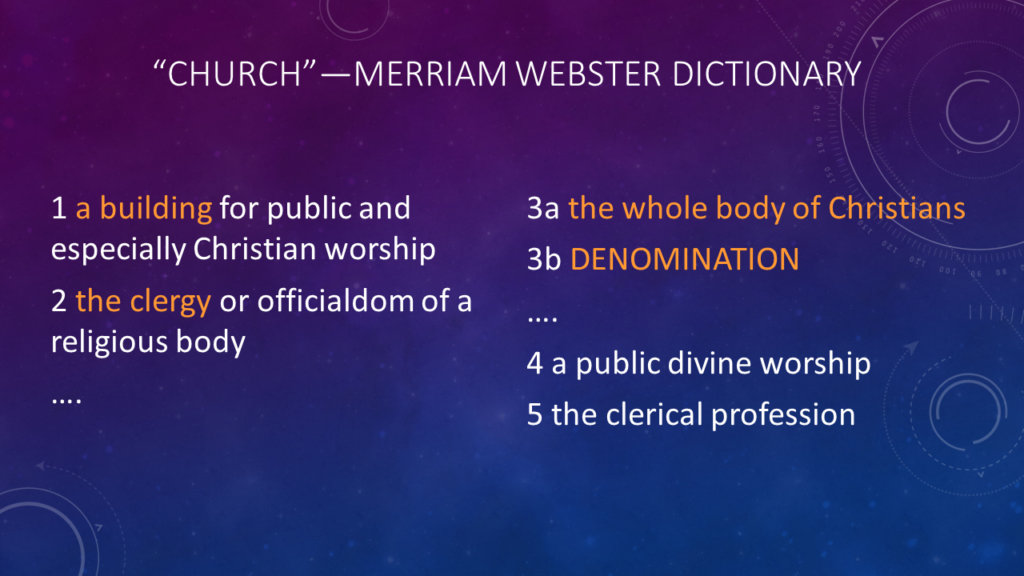

Next, what is “the Church”? Is “the Church” an organization? Is it the leaders of the organization? Is it all Christians, or a denomination of Christians? Or is “the Church” a series of meetings? Or a set of doctrines?

Or is it a building, as in “We are going to the church”?

Or, “I know the church is true.”

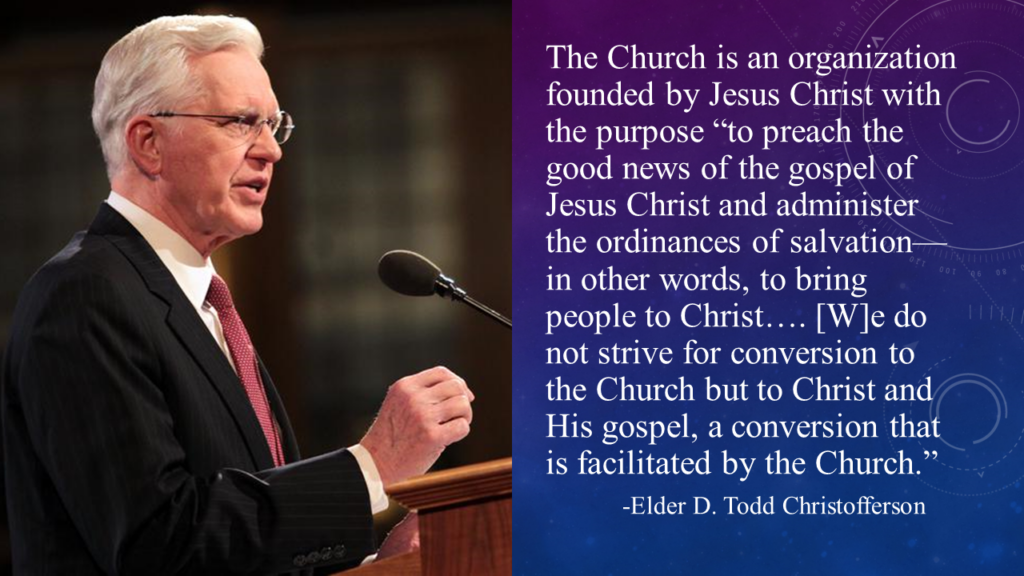

In this presentation, when I use the word “Church,” I am speaking of it in the same sense as Elder D. Todd Christofferson when he explained that the Church is an organization founded by Jesus Christ with the purpose “to preach the good news of the gospel of Jesus Christ and administer the ordinances of salvation—in other words, to bring people to Christ.”[6]

As I speak of “knowing,” or “proving the Church is true,” it is also essential to note that “we do not strive for conversion to the Church but to Christ and His gospel, a conversion that is facilitated by the Church.”[7] Therefore, I will speak of “knowing” or “proving the Church is true” in the same sense that we might speak of proving the gospel is true. However, for whatever reason, it seems more common to hear people speak of “knowing” or “proving the Church is true,” than to speak of “knowing,” or “proving that the gospel is true.”

When people bear their testimony, they sometimes give examples of what they mean and how they came to “know” that the “Church is true.” This knowledge is often explained in terms of an inner spiritual experience. Sometimes people speak of experiences with how other members of the Church have blessed their lives. Sometimes they explain how the teachings of the Church make sense.

“I know the Church is true”

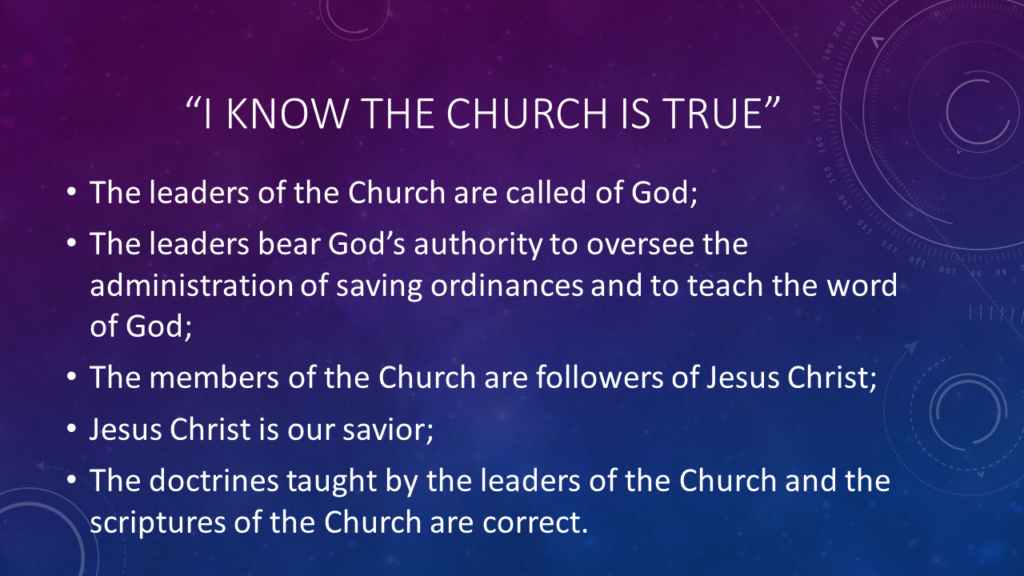

It seems that generally when people say they “know the Church is true,” they are saying that they have become convinced of one or more of the following:

- That the leaders of the Church are called of God;

- that they bear God’s authority to oversee the administration of saving ordinances and to teach the word of God;

- that the members of the Church are followers of Jesus Christ;

- that Jesus Christ is our savior; or

- that the doctrines taught by the leaders of the Church and the scriptures of the Church are correct.[8]

Whatever the approach, people seem less concerned when others stand at the pulpit and share their testimony that they “know the Church is true,” than about the idea that you can “prove” that the Church is true. Even among those who would stand and testify that they “know the Church is true,” there sometimes seems to be a belief that it would be improper to suggest that the “truth” of the “Church” can be “proven” to someone else.

Proving vs knowing

Surprisingly, while Hugh Nibley would seem to have spent his life gathering evidence in support of the truth of the Book of Mormon, he once said, “The evidence that will prove or disprove the Book of Mormon does not exist.”[9]

I will talk more later about what Nibley meant by this. But for now, let me just say that often, when when we speak of proving something, we are talking about demonstrating its truth to others. When someone states that they “know the Church is true,” in some sense they are saying that it has been “proven” to them that the Church is true. So we may say that we “know” something even if we feel unable to “prove” it to someone else.

For example, we may have seen an event, and therefore are convinced that it happened, but remain unable to persuade others that the event happened.

Of course, while we cannot “prove” everything that we know to others, we can certainly prove some things.

One thing I hope to prove to you is that it is not as hard to prove things as we might think.

I suspect another reason people are uncomfortable saying it can be proven that the Church is true is that it seems to suggest that we have no choice in the matter. In other words, the idea is that if something is “proven,” I have no choice but to believe it. This may be due to how the word “proof” is often used in common parlance. In response to any general assertion in an argument, people often say “prove it” as if to say, “demonstrate that what you are saying is true beyond all doubt.”

“Proof” defined

A common definition of “proof” is “the cogency of evidence that compels acceptance by the mind of a truth or a fact.”[10] This is the sort of proof that we expect to find in the field of mathematics where “[a] proof is a logical argument that establishes the truth of a statement beyond any doubt.”[11]

Regarding religion, we should all be able to agree that it would not be desirable to compel belief as it would violate principles of moral agency.

But as I will discuss below, there are things that have been said to be “proven” that some people still do not believe.

Proof does not compel belief

Furthermore, even miraculous acts of God do not compel commitment to the Church and Christ’s gospel.

For example, one may say if he were visited by God, or by angels, or if he could at least see the golden plates, he would have no choice but to remain faithful to the Church. However, all of these could be said of Oliver Cowdrey, and, for at least a time, he left the Church. In fact, the Doctrine and Covenants says regarding the devil that “a third part of the hosts of heaven turned he away from [God] because of their agency”[12] indicating that we can dwell in the presence of God, retain our agency, and still decide to wage war against God.

Why doesn’t God provide more evidence?

So the reason God doesn’t provide more evidence seems related to the fact that God’s intention for us is not simply that we believe. “Even the demons believe—and tremble!”[13] Instead, God hopes to help us develop into Christlike people.[14] There is something essential to our progression and to our demonstrating what our true desires are that requires that we leave God’s presence.[15] God provides enough evidence for us to be able to have the information we need to progress and demonstrate our desires, but it seems that this is a different amount of information for everyone.[16]

The ultimate test is whether or not we desire to do the will of God. For at least a third part of us, this test could be applied in the light of absolute proof. For most of us, we must proceed, as it were, while seeing “through a glass darkly.”

However, none of us are totally blind. At the very least, we all come into this world with the light of Christ. Concerning our actions in this life, we will each be judged according to the light and knowledge with which we are blessed, however much that may be. Of course, “God is faithful, who will not suffer [us] to be tempted above that [we] are able.”[17] Thus, our test does not depend upon our actions in the face of a lack of evidence. Rather, it depends on, whether we are willing to do the will of God in light of the evidence we are given.[18]

The crux of the issue is in clear definitions

So the crux of the issue lies in the definitions of the words. Just as it may be hard to know what is meant by the phrase “I know the Church is true,” the phrase “prove the Church is true” is problematic since it can also be unclear. And just as a person may have set the bar too high for what it takes to know something, what I will now set out to prove to you is that it’s not as hard to prove things as we often assume.

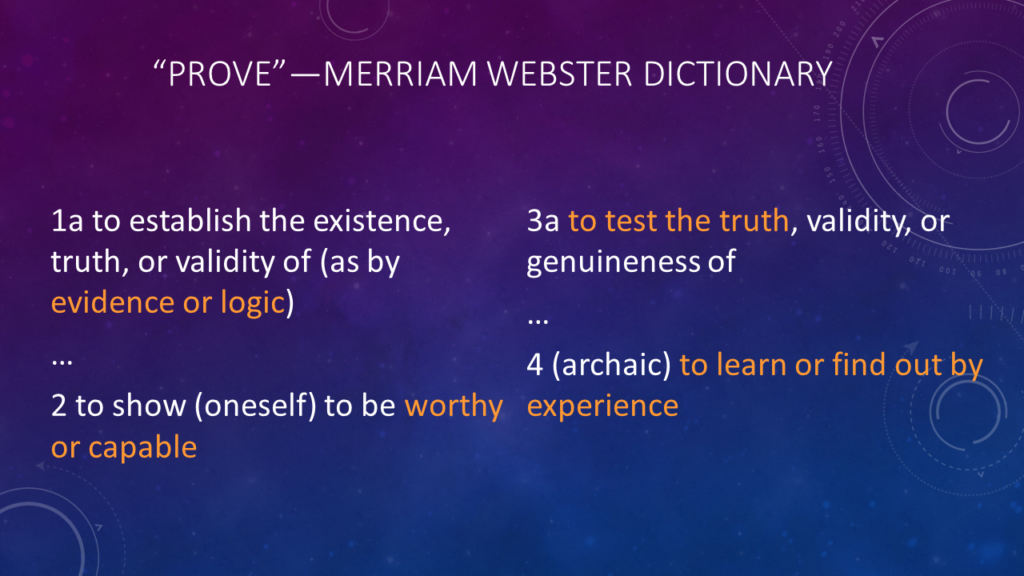

The word “prove” can have a variety of meanings. Most commonly, it can refer to establishing that something is true “as by evidence or logic.” It can also mean “to show (oneself) to be worthy or capable,” or “to test the truth, validity, or genuineness of,” as in a mathematical proof, or, interestingly, it carries the archaic meaning “to learn or find out by experience.”[19]

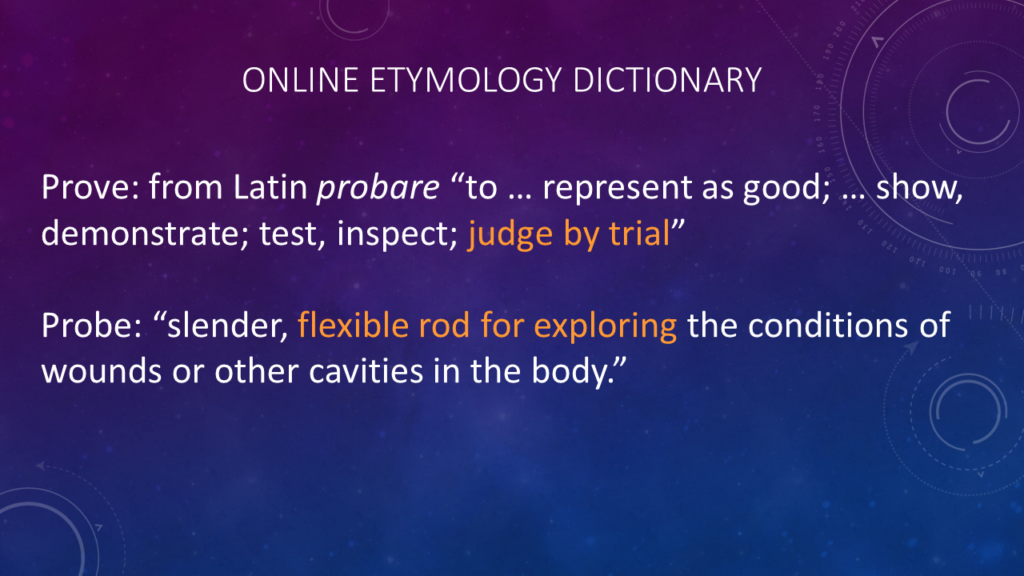

The word “prove” is derived from the Latin word probare, which means “to … represent as good; … show, demonstrate; test, inspect; judge by trial” It is also interesting to note that the same Latin word is where we get our word “probe” which, from the early fifteenth century, meant a “slender, flexible rod for exploring the conditions of wounds or other cavities in the body.”[20]

The process of proving

Depending upon the definitions we use, the process of “proving” the Church to be true would seem most often to involve a process of setting out evidence, logical arguments, and even a “probing” of the facts and finding out by experience whether the Church is true.

As the word “prove” in modern usage often relates to a process that takes place in a trial before a judge, it raises the question of how matters are proven in a modern courtroom. I will therefore take as an example the standards for proving a case in the modern courts in the United States. In light of these standards, we will then take a close look at what the scriptures say about proving the Church to be true. Hopefully, this exercise will also shed light on whether we should even try to “prove the Church is true,” how it is that people become converted, and what we can do to help lead people to Christ.

The standard of truth

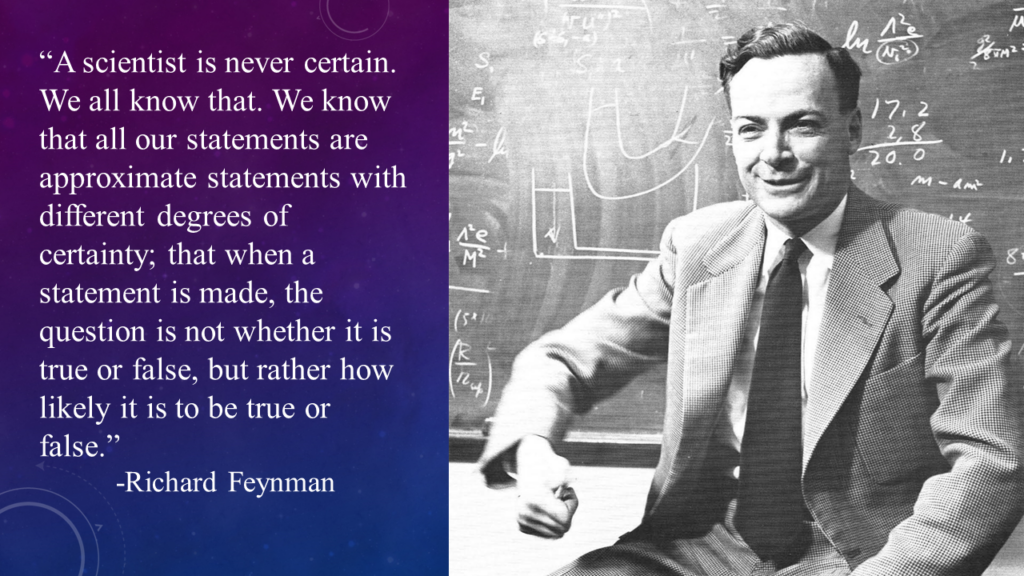

The best place to begin when we talk about proving something is to establish the standard of proof. It is very rare and nearly impossible to find a proposition that is proven beyond all doubt. People tend to think of the field of science as one where conclusions are “proven,” but, as the Nobel-Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman said, “A scientist is never certain. We all know that. We know that all our statements are approximate statements with different degrees of certainty; that when a statement is made, the question is not whether it is true or false, but rather how likely it is to be true or false.”[21]

Even in the field of mathematics, as Kurt Gödel [“Goodle”] demonstrated with his incompleteness theorums, mathematics contains some true statements that cannot be proven.[22]

The mathematician John Barrow said this about Gödel’s theorems: “If a ‘religion’ is defined to be a system of ideas that contains unprovable statements, then Gödel taught us that mathematics is not only a religion, it is the only religion that can prove itself to be one.”[23]

Nevertheless, in our everyday lives, we often act with a high level of confidence when such confidence may not be justified.

‘Bet your life’

For example, we might say that a person can show no higher degree of confidence than when they would bet their life on something. The CDC estimates that 3,000 die from foodborne diseases each year in the United States.[24] So when someone else prepares our food, we are putting our lives in the hands of the cook when that person may be a total stranger. It might be said that we “know” we won’t die since we have confidence in government health inspectors, market forces, or in personal, past experience or observations of the experience others have had going to a particular restaurant and coming out alive. Of course, if asked, it seems unlikely that a restaurant patron would say that the evidence was so compelling that there could be no doubt that the food was safe. So would the restaurant patron say that there was “proof” that they would not die? If there was “no proof,” why would they bet their life on it? It seems that practically speaking, we are often willing to act on evidence that is less than compelling. We are even willing to bet our lives on it. So if restaurant patrons would bet their lives on the proposition that the food being served is safe, would it be accurate if they were to declare that they “know the food is safe”? Or that the safety of the food has been “proven” to them?

Viewing courtroom standards of truth in light of the scriptures

Joseph Fielding Smith once invoked the venue of a courtroom in explaining the degree to which he held the evidence supporting the veracity of Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery: “I believe that I can point to evidence, circumstantial it may be, yet evidence that ought to be convincing in any court in the land, that would prove beyond the possibility of doubt that Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery spoke the truth.”[25]

While this statement of Joseph Fielding Smith lacks jurisprudential rigor, (there is no standard of proof reaching to “beyond the possibility of doubt”), it is interesting, nonetheless, to consider how standards of proof operate in the courtroom and then consider these standards in light of what the scriptures teach. We agree as a modern society that certain matters can be proven in a court of law. There is a well-developed system and easily-grasped standards established for reaching these ends. Considering these standards in light of what the scriptures teach about proof should be a useful exercise.

I will undertake that study here by first considering the way in which modern juries are typically instructed within the United States regarding proof. We will then examine some examples within the scriptures where proof is discussed. As we do so, it will be interesting to see how the language of the modern courtroom as well as the standards of proof juries must apply help illuminate the response of the scriptures to the question of whether we can “prove that the Church is true.” What we will find is that not only do the scriptures insist that the truths of the gospel can be proven, but that the evidence and arguments set forth in the scriptures are held out as satisfying the highest standards of proof.

This discussion is primarily addressed to those who would say that you cannot “prove that the Church is true,” who nevertheless, believe themselves that the Church is true. But it may also be helpful to nonbelievers as we compare and contrast the meaning of “proof” within the scriptures with its meaning within the American legal system.

I hope to further show that it is unreasonable to hold religious propositions to a standard of proof that is inconsistent with the standard we apply in other areas of our society.

A different standard

Harvard law professor Simon Greenleaf bemoaned the fact that we hold religious propositions to a different standard and exclaimed:

All that Christianity asks of men on this subject is that they would be consistent with themselves; that they would treat its evidence as they treat the evidence of other things; and that they would try and judge its actors and witnesses as they deal with their fellow men, when testifying to human affairs and actions, in human tribunals. Let the witnesses be compared with themselves, with each other, and with surrounding facts and circumstances; and let their testimony be sifted, as if it were given in a court of justice, on the side of the adverse party, the witness being subjected to a rigourous cross-examination. The result, it is believed, will be an undoubting conviction of their integrity, ability, and truth.[26]

PROOF IN A COURT OF LAW

It is helpful to note that in modern courtrooms, it is understood that there are various levels of proof and that a proposition may be said to have been “proven” when the matter is established at a level much lower than the realm of “no doubt.” Evidentiary standards of proof include reasonable suspicion, probable cause, substantial evidence, preponderance of the evidence, clear-and-convincing evidence, and beyond reasonable doubt. For the sake of time, I’ll focus on two of these.

In the typical civil case where money or property is at stake, a plaintiff must “prove” his or her claim by a “preponderance of the evidence.” On this point, a jury might be instructed as follows:

Burden of Proof—Preponderance of the Evidence

When a party has the burden of proving any claim by a preponderance of the evidence, it means you must be persuaded by the evidence that the claim is more probably true than not true.[27]

Another way of expressing this would be to say that there must be a better than fifty-percent chance that the claim is true for it to be “proven.”[28] Of course, this leaves almost as much room for doubt as for confidence that a claim is true. Even if a claim remains forty-nine percent dubious, it can still be said to have been “proven” by a preponderance of the evidence.

In federal courts, unless the parties stipulate otherwise, the verdict of the jury must be unanimous.[29] That is also true in state criminal trials.[30] However, in state court civil trials, only “[t]wenty-one states, the District of Columbia, and the federal courts still require a unanimous verdict in all civil cases while twenty-nine states require a super majority.”[31]

In other words, in most states, under the preponderance of the evidence standard, a claim made in a civil trial may be found to be proven, even if some members of the jury disagree, and even if the claim is only proven to an extent only barely over the fifty-percent mark. Even by this low standard, the prevailing party is justified in stating that the claim was proven to be true.

The standard with which most people are probably familiar is the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard. This is the standard that applies to the question of whether or not an individual is guilty of a crime. Regarding this standard, juries are often instructed as follows:

Reasonable Doubt—Defined

Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is proof that leaves you firmly convinced the defendant is guilty. It is not required that the government prove guilt beyond all possible doubt.

It is interesting to note that even under the standard of beyond reasonable doubt, there is some room for doubt, albeit unreasonable doubt.[32]

THE SCRIPTURAL STANDARD OF PROOF

Turning to the scriptures, we find that the standard of proof seems to be similar to that of the higher standards of proof in the law. It is apparent that God intends for us not only to be persuaded that the gospel is probably true, as in the preponderance of evidence standard, but God also intends for us to be convinced. Consider the following scriptures:

[The purpose of the Book of Mormon is] to the convincing of the Jew and Gentile that Jesus is the Christ, the Eternal God, manifesting himself unto all nations. (Title Page of the Book of Mormon) (emphasis added).

And then cometh the day when the arm of the Lord shall be revealed in power in convincing the nations . . . of the gospel of their salvation. (D&C 90:10) (emphasis added)

And there are numerous other such scriptures that are cited in my book chapter.[33]

EVIDENCE IN THE COURTROOM

Regarding the various forms of evidence that are submitted in a courtroom to prove, or disprove, a case, juries are typically instructed as follows:

What is Evidence

The evidence you are to consider in deciding what the facts are consists of:

- the sworn testimony of any witness;

- the exhibits that are admitted into evidence;

- any facts to which the lawyers have agreed; and

- any facts that [the judge] may instruct [the jury]

to accept as proved.

Note that the testimony of witnesses is listed first. This is the primary way by which evidence is submitted, even when documents or other physical evidence are being presented to a jury. Thus, it is especially important for a jury to consider whether or not the testimony of each witness is credible. Juries are therefore often instructed as follows:

Credibility of Witnesses

In deciding the facts in this case, you may have to decide which testimony to believe and which testimony not to believe. You may believe everything a witness says, or part of it, or none of it.

In considering the testimony of any witness, you may take into account:

- the opportunity and ability of the witness to see or hear or know the things testified to;

- the witness’s memory;

- the witness’s manner while testifying;

- the witness’s interest in the outcome of the case, if any;

- the witness’s bias or prejudice, if any;

- whether other evidence contradicted the witness’s testimony;

- the reasonableness of the witness’s testimony in light of all the evidence; and

- any other factors that bear on believability.

Sometimes a witness may say something that is not consistent with something else he or she said. Sometimes different witnesses will give different versions of what happened. People often forget things or make mistakes in what they remember. Also, two people may see the same event but remember it differently. You may consider these differences, but do not decide that testimony is untrue just because it differs from other testimony.

EVIDENCE IN THE SCRIPTURES

As in a court of law, the scriptures place great stock in the testimony of witnesses. In seeking to know the truth, we are not left alone and expected to rely only upon our own personal experience. Rather, we can consider the testimony of witnesses and judge their credibility as we weigh the evidence.

Early in the scriptural record, witnesses are held out as essential in establishing the truth of an allegation of fault:

“One witness shall not rise up against a man for any iniquity, or for any sin, in any sin that he sinneth: at the mouth of two witnesses, or at the mouth of three witnesses, shall the matter be established” (Deuteronomy 19:15).

The New Testament

This standard for establishing the truth of legal matters was understood in New Testament times if not earlier, to apply in establishing the truth more broadly. For example:

This is the third time I am coming to you. In the mouth of two or three witnesses shall every word be established. (2 Corinthians 13:1)[34]

If I bear witness of myself, my witness is not true. (John 5:31)

Christ does not ask us to just take his word for it. He provides evidence.

The Book of Mormon

The people of the Book of Mormon also understood that God intended to “prove” or “establish” His word through the testimony of witnesses. Here’s just one example:[35]

And my brother, Jacob, also has seen him as I have seen him; wherefore, I will send their words forth unto my children to prove unto them that my words are true. Wherefore, by the words of three, God hath said, I will establish my word. Nevertheless, God sendeth more witnesses, and he proveth all his words…. And my soul delighteth in proving unto my people that save Christ should come all men must perish. (2 Nephi 11:3 & 6)

The Current Dispensation

In our dispensation as well, witnesses have played a central role in establishing the truth of the gospel. Here is one of many examples:[36]

I, the Lord, am God, and have given these things unto you, my servant Joseph Smith, Jun., and have commanded you that you should stand as a witness of these things;.…. And in addition to your testimony, the testimony of three of my servants, … Yea, they shall know of a surety that these things are true, for from heaven will I declare it unto them. I will give them power that they may behold and view these things as they are;…. And the testimony of three witnesses will I send forth of my word.….” (Doctrine and Covenants 5:2, 11-13 & 15)

compare & contrast: civil cases vs religious

To summarize, in civil cases, it is appropriate to say that a claim is “proven” even when there may be nearly as much doubt about a claim as there is confidence that a claim is true.

Furthermore, even when the standard of proof is higher, such as in criminal cases, the range of evidence that can be considered by a jury is limited to what can be submitted through witnesses, documents and physical evidence. In other words, while a jury may hear the testimony of witnesses and may examine documents or other physical evidence (such as a gun, etc.), a jury would not have witnessed the events themselves. In fact, a person would not be allowed to serve on a jury if that person had been a witness to the events that are the subject of the trial.[37] Although the jurors themselves are not eyewitnesses, and although they do not have a personal experience with the facts of the case, our system of justice is premised upon the notion that a matter can nonetheless be proven.

By contrast, in matters of religion, we are not only able to benefit from the examination of the documents that have been produced, and from the testimony of witnesses, but we also become witnesses ourselves. We can “test the spirits” (1 John 4:1-3 (NRVS)) and we can “experiment upon [the] words” that we are taught by applying them in our lives to see if they bring forth good fruit (Alma 32:27-43).[38] We are told that as we faithfully apply a gospel principle in our lives and see the good results that our “knowledge is perfect in that thing,” (Alma 32:34).[39] We are further taught that by virtue of a personal experience with the Holy Ghost, we can “know the truth of all things” (Mor. 10:5).[40]

Again, before a jury may find a criminal defendant to be guilty, they must be “firmly convinced the defendant is guilty”. This is possible through the testimony of witnesses and through documents and physical evidence. However, the scriptures teach that a personal experience with the Holy Ghost can not only convince us that the gospel is true, but it can change our hearts. When King Benjamin asked his people whether they believed his words, the people reported:

Yea, we believe all the words which thou hast spoken unto us; and also, we know of their surety and truth, because of the Spirit of the Lord Omnipotent, which has wrought a mighty change in us, or in our hearts, that we have no more disposition to do evil, but to do good continually. (Mos. 5:2)

SCRIPTURAL COMMENTARY ON PROOF, EVIDENCE, TESTIMONY, ETC.

Nevertheless, while the Holy Ghost is a powerful means by which people become convinced that the gospel is true, and even holds the power of changing hearts, it is not the only way by which the scriptures indicate that matters of religious doctrine are proven.

As in a court of law, the testimony of witnesses is one method by which God’s word is said to be proven. In addition to the verses quoted above,[41] we also read,

“[Nephi and Lehi] did minister unto the people, declaring throughout all the regions round about all the things which they had heard and seen, insomuch that the more part of the Lamanites were convinced of them, because of the greatness of the evidences which they had received” (Hel. 5:50).[42]

In a similar fashion, the Doctrine and Covenants teaches that the Book of Mormon itself serves as a witness to the fact that the Bible is true.

The Lord indicates that the Book of Mormon came forth, “Proving to the world that the holy scriptures are true, and that God does inspire men and call them to his holy work in this age and generation, as well as in generations of old.”[43]

A brief survey of the scriptures will further demonstrate that proof is said to have been accomplished through a wide variety of other means.

Proof by Sensory Experience

In Acts 1:3, we find that proof of the resurrection came through sensory observation: “To whom also [Christ] shewed himself alive after his passion by many infallible proofs, being seen of them forty days, and speaking of the things pertaining to the kingdom of God.”

Proof By Argument from The Scriptures (Appeal To Authority)

The author of Acts indicates that Paul used the scriptures to prove that the gospel is true, although the argument itself is not set forth:

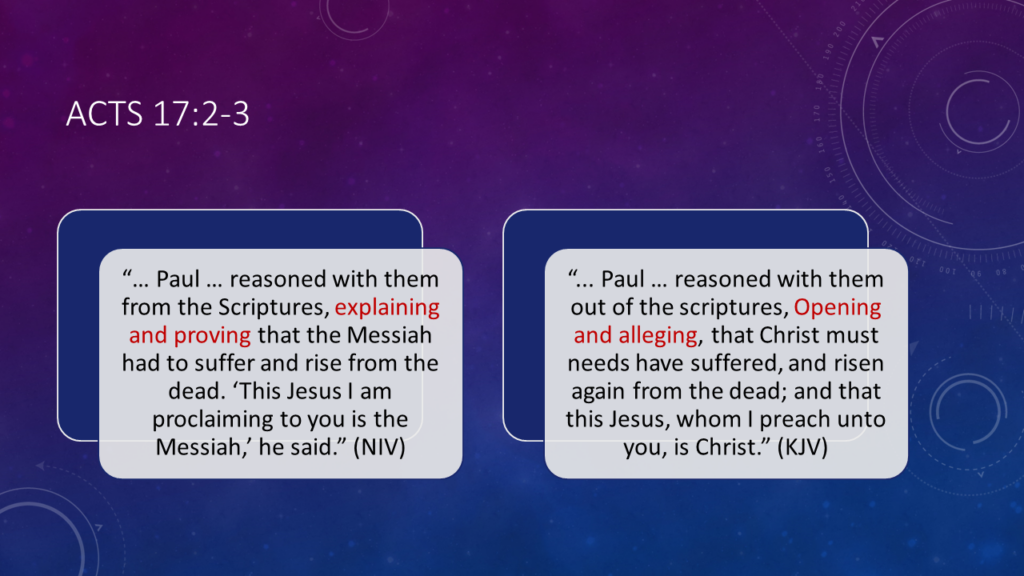

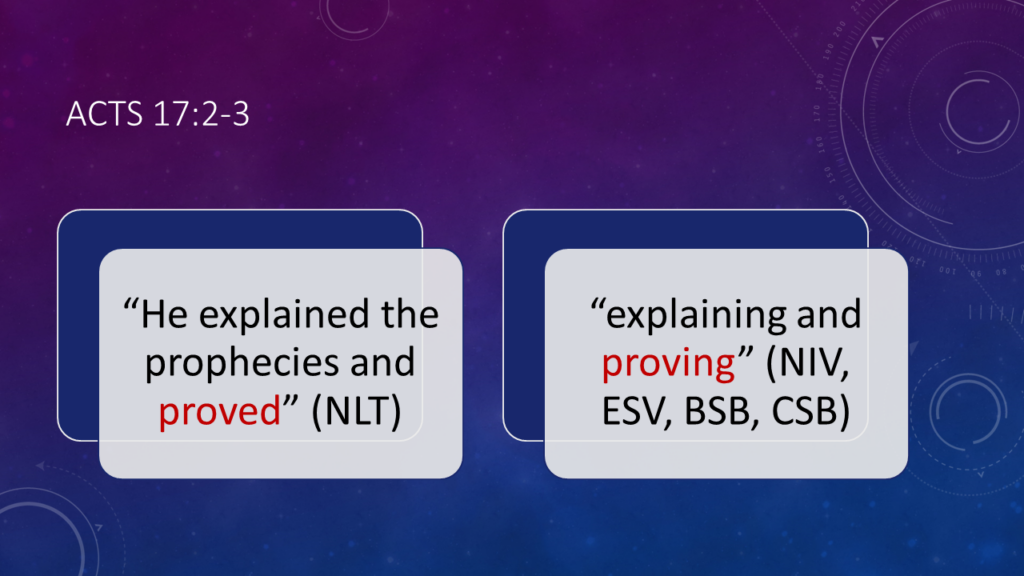

“As was his custom, Paul went into the synagogue, and on three Sabbath days he reasoned with them from the Scriptures, explaining and proving that the Messiah had to suffer and rise from the dead. ‘This Jesus I am proclaiming to you is the Messiah,’ he said” Acts 17:2-3 (NIV).

Perhaps similarly, in a revelation directed to Sidney Rigdon regarding his call as a scribe to Joseph Smith, he was told that he should use the scriptures in acting as a second witness to the words of Joseph Smith:

“And inasmuch as ye do not write, behold, it shall be given unto him to prophesy; and thou shalt preach my gospel and call on the holy prophets to prove his words, as they shall be given him” (D&C 35:23).

In addition to at least 5 other examples I’ve found in the scriptures,[44] in Alma we read:

“And ye also beheld that my brother [Alma] has proved unto you, in many instances, that the word is in Christ unto salvation. My brother has called upon the words of Zenos, that redemption cometh through the Son of God, and also upon the words of Zenock; and also he has appealed unto Moses, to prove that these things are true.”[45]

The Created Have a Creator

Nephi argues that the very fact that we exist proves that we have a Savior:

“And my soul delighteth in proving unto my people that save Christ should come all men must perish. For if there be no Christ there be no God; and if there be no God we are not, for there could have been no creation. But there is a God, and he is Christ, and he cometh in the fulness of his own time” (2 Ne. 11:6-7).[46]

Proof by Pragmatism

It is also said that we may prove God’s word by putting it to the test to see if it works.

In Malachi, we read, “Bring ye all the tithes into the storehouse, that there may be meat in mine house, and prove me now herewith, saith the Lord of hosts, if I will not open you the windows of heaven, and pour you out a blessing, that there shall not be room enough to receive it.”[47]

There are other examples in the Book of Mormon and the New Testament that we don’t have time to read now.[48]

Proof by Proper Functionalism

While we can know that God’s word is true based upon the external, tangible results that come from living its principles, it has also been said that we can know the truth by virtue of an internal perception that such is the case. This concept was given the name “proper functionalism” by modern philosophers of epistemology.[49] The process was described, at least in part, by Alma as follows:

Now, we will compare the word unto a seed. Now, if ye give place, that a seed may be planted in your heart, behold, if it be a true seed, or a good seed, if ye do not cast it out by your unbelief, … it will begin to swell within your breasts; and when you feel these swelling motions, ye will begin to say within yourselves—It must needs be that this is a good seed, or that the word is good, for it beginneth to enlarge my soul; yea, it beginneth to enlighten my understanding, yea, it beginneth to be delicious to me. (Alma 32:28.)

Proof by Personal Revelation

Of course, it is commonly understood by members of the Church that personal revelation serves as a form of private evidence that will support a personal testimony.

The prophet Jacob declares that when personal revelation is combined with the testimonies of the prophets in the scriptures, we can develop an unshaken faith:

“Wherefore, we search the prophets, and we have many revelations and the spirit of prophecy; and having all these witnesses we obtain a hope, and our faith becometh unshaken, insomuch that we truly can command in the name of Jesus and the very trees obey us, or the mountains, or the waves of the sea” (Jacob 4:6).

This verse suggests that the process of obtaining this unshaken faith is not merely a personal event. It is described here as something that comes by virtue of a study of the scriptures and not something that merely appears out of nowhere. An individual must make a personal effort and that effort is necessarily guided by the testimony of witnesses of Christ’s word.

This reminds us of Paul’s counsel to the Romans: “So faith comes from what is heard, and what is heard comes through the word of Christ” (Rom. 10:17, NRSV).[50]

AN EXPLORATION OF THE MEANING OF THE WORD “PROVE”

It should be clear by now that the scriptures indicate that God intends to prove to us, and He intends for us to prove to each other, that the Church (i.e., the gospel) is true. As discussed previously, the word “prove” can be understood in various ways by modern readers. So it raises a question regarding the way in which the word should be defined as it appears in the scriptures.

My discussion has focused on the language of the scriptures as they appear in English and, with only a few exceptions, the King James Version of the Bible. As we explore whether it is possible to “prove that the Church is true,” it may be helpful to review the definitions of the word “prove” in English and the words that are used in Hebrew and Greek where that word appears in English translations.

The word “Prove” in the Doctrine and Covenants and the Book of Mormon

A good way to examine the meaning of the word “prove” as it appears in the Doctrine and Covenants is to use Webster’s 1828 Dictionary since that volume reflects the way in which words were commonly being used in English at the time the Doctrine and Covenants was written.

The word “prove” is most often used in the Doctrine and Covenants in a way that is described by Webster’s as meaning “to try by suffering or encountering; to gain certain knowledge by the operation of something on ourselves, or by some act of our own”[51] as in

“I will try you and prove you herewith” (D&C 98:12).[52]

However, there are at least two examples, D&C 20:11 and D&C 35:23, which I read earlier, where the word is used in the sense described in Webster’s Dictionary as “To evince, establish or ascertain as truth, reality or fact, by testimony or other evidence. The plaintiff in a suit must prove the truth of his declaration; the prosecutor must prove his charges against the accused.”

It is far more common to find this use of the word “prove” in the Book of Mormon, and there are many such examples, as noted above. However, as Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack have argued, the language of the Book of Mormon does not reflect the way in which the language was used in 1800s America, or even in the King James Version of the Bible. Rather, the language of the Book of Mormon most nearly parallels Early Modern English.[53] For this reason, it would be helpful to consider the etymology of the word “prove” in English.

Etymology: Prove

The word is said to have originated around 1200 A.D. and in its early usage meant “to try by experience or by a test or standard; evaluate; demonstrate in practice.”[54] So, the word originally had a meaning that was still in common usage by the time of the publication of Webster’s 1828 Dictionary and the Doctrine and Covenants.

By the 1300s, the word was being used in the way we are examining here. That is, “find out, discover, ascertain; prove by argument.”[55] So, when used in this sense, the English word “prove” was being used in the first editions of the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants in a way with which we are familiar when speaking modern English and when we might speak of whether or not we can “prove that the Church is true.”

The word “Prove” in the Hebrew Bible

The only time in the King James Version of the Hebrew Bible that the word “prove” is used in the sense of proving that God’s word is true is in Malachi 3:10, where it reads: “Bring ye all the tithes into the storehouse, … and prove me now herewith.”[56]

The Hebrew word for “prove” here is (ba hahn) “bachan”, and it is said to mean “to examine, try”.[57] The word is especially used in the sense of testing metals but is also used “to investigate — examine, prove, tempt, try (trial).”[58] Again, we find that the scriptures, in quoting God Himself, teach that it is possible to “prove” whether or not God’s word is true.

The word “Prove” in the New Testament

It is more common to find in the New Testament than in the Old the use of the word “prove” to refer to establishing that God’s word, or the gospel, is true. This may be due to the fact that much of the New Testament is presented in the form of an argument intended to convince us that Jesus is the Christ. So it may not be surprising to find many instances where it is said that the truth of the gospel can be proven.

Starting with the book of Acts, we find that when the writer describes Christ’s visit after he rose from the dead, showing “many infallible proofs” (Acts 1:3), the word used here is tekmēriois, and it is the only instance of its being used in the Greek New Testament. This word is described as “a token (as defining a fact), i.e., Criterion of certainty–infallible proof,” and as “properly, a marker (sign-post) supplying indisputable information.”[59] Thayer’s Greek Lexicon adds that “from Aeschylus and Herodotus down, [the word describes] that from which something is surely and plainly known; an indubitable evidence, a proof.”[60] It is hard to imagine any stronger way to describe that which is proven to be true.

In Acts 9:22, we read that Paul “confounded the Jews … proving that this is very Christ.”

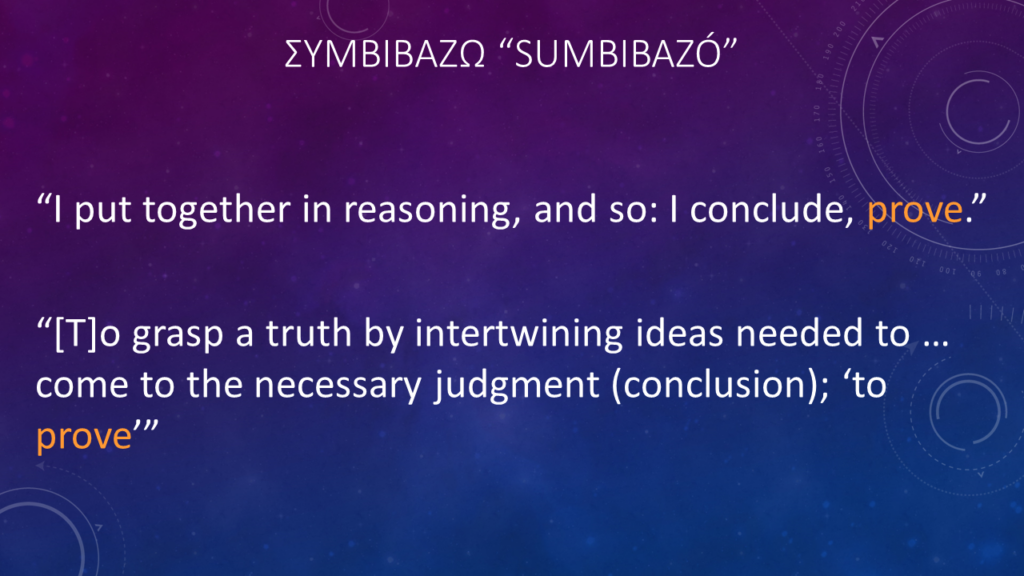

The word used here is sumbibazó. The word can be used in a way that means to “put together in reasoning, and so: I conclude, prove” or “I teach, instruct.”[61] This word can be used figuratively to mean “to grasp a truth by intertwining ideas needed to … come to the necessary judgment (conclusion); ‘to prove’”[62] This verse, therefore, suggests that Paul was teaching from the scriptures in a way that “proved” that Jesus was the Christ by convincing his listeners to reach the same conclusions that he had reached.

While the NIV translation of Acts 17:2-3 states that Paul proved his argument that Jesus is the Messiah, the KJV translation of Acts 17:2-3 indicates that Paul merely stated this as an allegation. The choice of the word “alleged” is interesting since at least by the 1670s, the word “alleged” has meant something that was “asserted but not proved.”[63]

In its earlier usage, by the mid-fourteenth century, the word was being used to refer to something that was claimed to be true “with or without proof.”[64]

Many modern translators have concluded that the earlier usage of the word is closer to what the King James Translators had in mind as this word is translated as “proved” or “proving.”[65]

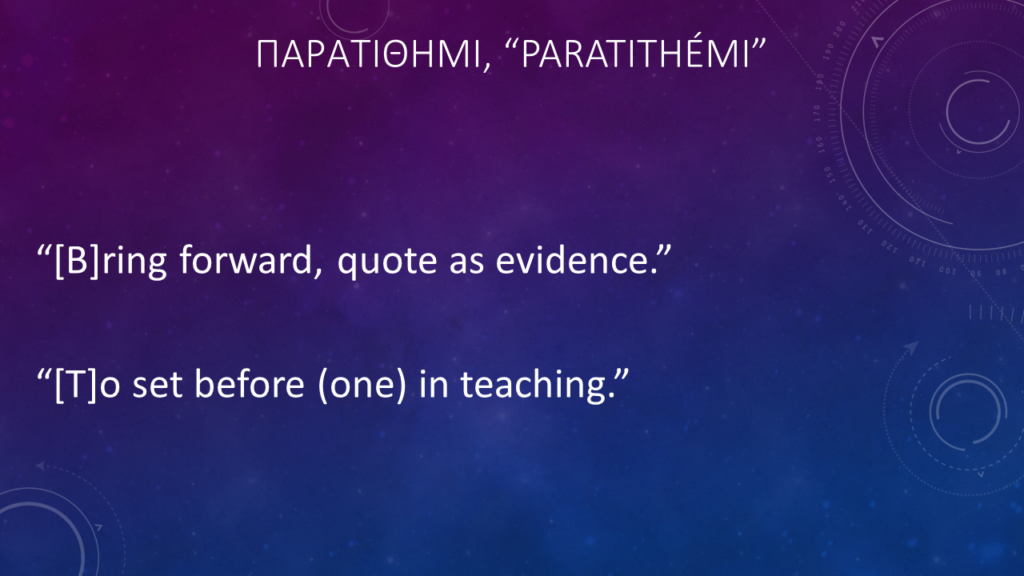

The word in Greek is paratithémi. This word can be used to mean to “bring forward, [or] quote as evidence.”[66] Thayer’s Greek Lexicon adds that the word carries the connotation of “to set before (one) in teaching.”[67]

In light of all of this, it seems that the Greek indicates that Paul did something more than merely make a claim, rather, he put on evidence in support of the claim.

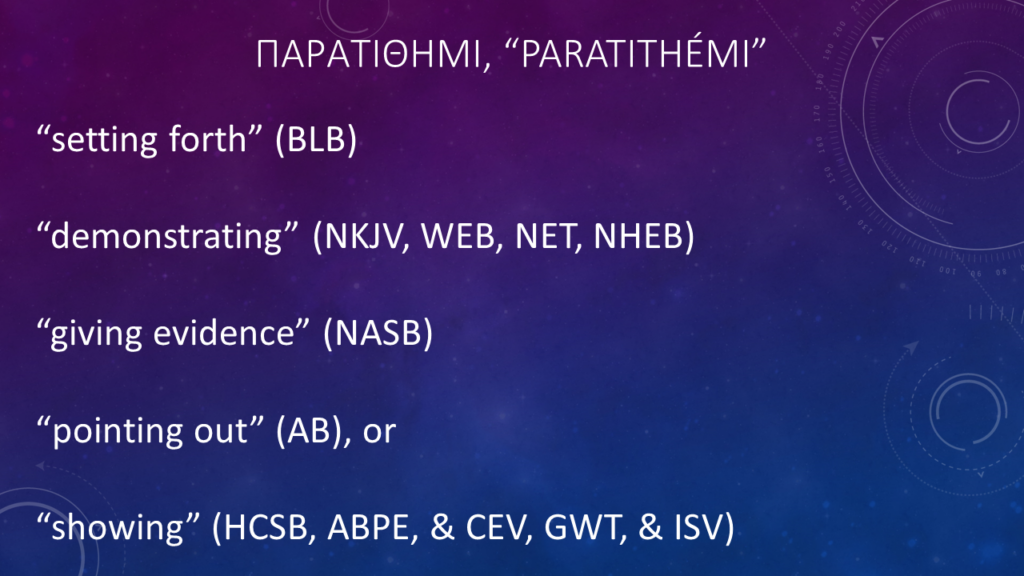

It would perhaps be too strong in this instance to claim that Paul was “proving” that Jesus was the Christ, in the sense that he was indisputably establishing it, but rather, as translated in various English editions, he was “setting forth” (BLB), “demonstrating” (NKJV, WEB, NET, NHEB), “giving evidence” (NASB), “pointing out” (AB), or “showing” (HCSB, ABPE, & CEV, GWT, & ISV) that Jesus is the Christ.[68]

So it may be that this could be considered proof by a lower standard. This is not the tekmérion of Acts 1:3, but it is still a demonstration of evidence from the scriptures that had the effect of convincing at least some listeners, as the next verse reads: “And some of them believed” (Acts 17:4).

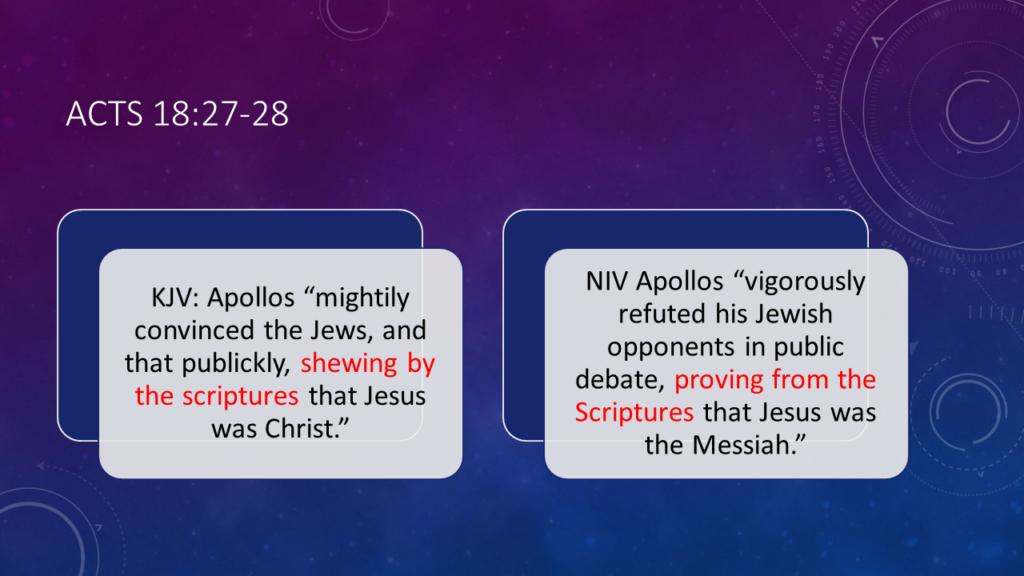

In Acts 18, we read in the King James Version that Apollos “mightily convinced the Jews, and that publickly, shewing by the scriptures that Jesus was Christ.” The NIV translation puts a different spin on the impact the argument had stating that Apollos “vigorously refuted his Jewish opponents in public debate, proving from the Scriptures that Jesus was the Messiah.”

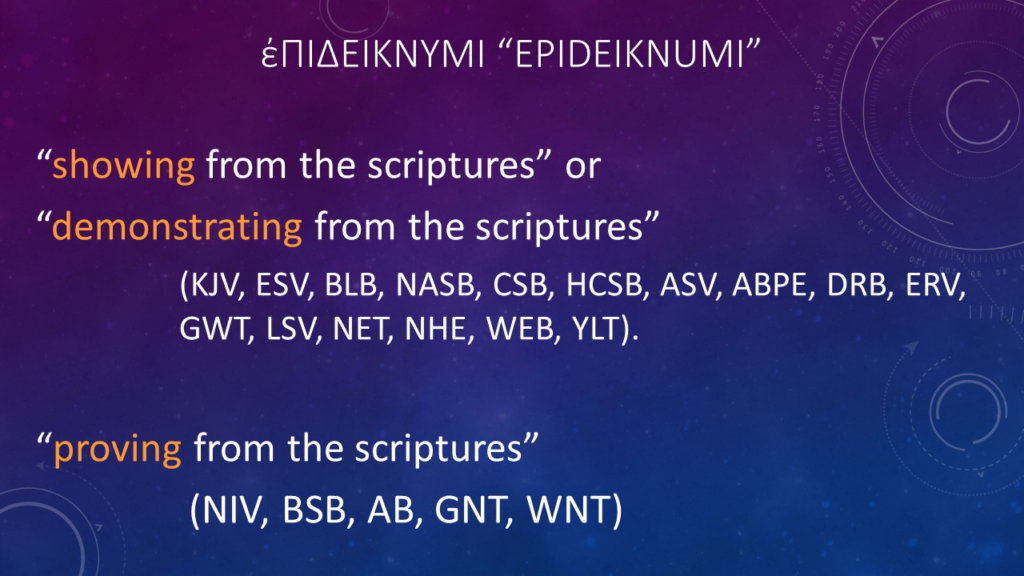

It is common in English translations to translate this phrase in Acts 18:28 as “showing from the scriptures” or “demonstrating from the scriptures”.[71] However, “proving from the scriptures:” is also used.[72] Again, while “showing” or “demonstrating” something to be true is less forceful language than the “infallible proofs” of Acts 1:3, it is safe in this instance to consider epideiknumi a form of “proof” as well.

When Paul counsels the Roman saints to transform themselves in order to “prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God” (Rom. 12:2), this seems to be the kind of proof that is private and experienced by the individual who is doing the changing. There is no indication in the text that this transformation is intended to prove to others the will of God.

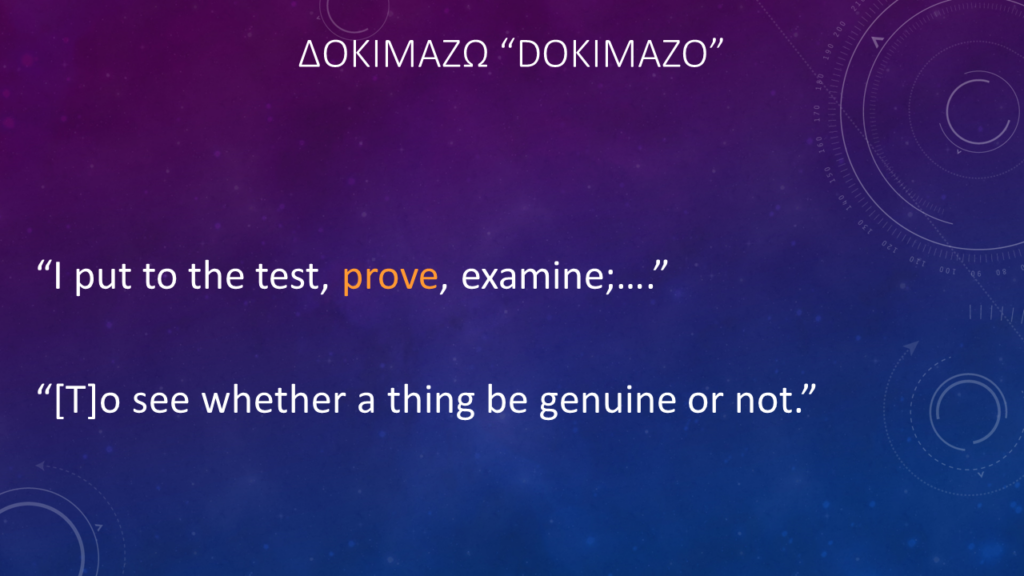

The word here in Greek is dokimazo. This word is used in the sense of “I put to the test, prove, examine;….”[73] Thayer’s Greek Lexicon explains that this term means “[T]o see whether a thing be genuine or not.” and has been used in ancient literature to refer to a test of metals, as well as men and other things.[74]

In seeking to know Paul’s meaning, it is helpful to consider that the word dokimazo is also used in 1 Thessalonians 5:21, where Paul writes: “Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.” Again, the word here seems to indicate that a person should conduct a personal test to determine what principles are true and which are false, and in this way, “prove” it to one’s self. Indeed, rather than use the word “prove” as in the KJV, modern translations most often use the word “test” or “examine” all things.[75]

Nevertheless, while this is a subjective form of proof, it is a form of proof nonetheless. It is thus evident that Paul believed that one could discover for oneself that which is true by putting the principles of the gospel to the test. This approach seems very much like that which is recommended by Alma where he counsels the Zomamites to “experiment upon my words” (Alma 32:27), which, he says, can lead to a perfect knowledge of that thing experimented upon (Alma 32:34).

ON PROOF AND KNOWING GOD

The scriptures teach that the principles of the gospel can be proven in a variety of ways. Of course, Hugh Nibley was correct, in some narrow sense, that “The evidence that will prove or disprove the Book of Mormon does not exist.” However, here, as always, we should examine what is meant by “prove.” Nibley elaborates on this point as follows:

When, indeed, is a thing proven? Only when an individual has accumulated in his own conscience enough observations, impressions, reasonings, and feelings to satisfy him personally that it is so. The same evidence which convinces one expert may leave another completely unsatisfied; the impressions that build up to definite proof are themselves nontransferable. All we can do is to talk about the material at hand, hoping that in the course of the discussion every participant will privately and inwardly form, reform, change, or abandon his opinions about it and thereby move in the direction of greater light and knowledge. Some of the things in [the book Since Cumorah] we think are quite impressive, but there is no guarantee at all that anybody else will think so.[76]

In this last sentence, Nibley reveals what he means by “proving” something to be true: a guarantee that someone else will be satisfied with the truth of some matter. So while it may be true that no one can guarantee that providing evidence supporting the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon will convince all who listen that the book is true, we can be guaranteed that if nothing regarding the Book of Mormon is shared that no one will be convinced.

The process of “proving” something to be true involves sharing information, without which there is no proof, and with which, there is some hope of conversion. If a person is converted by virtue of the testimony of a believer, that person may come to say that the matter was proven to him or her. Or if an outside observer is reporting on the circumstances, we may read, as we do in many of the scriptures cited above, that the matter was “proven.” So there are a variety of ways in which it is correct to say that gospel principles, the Church, and the Book of Mormon can be “proven” to be true.

We can come to Know

Of course, while information, the testimony of witnesses, and rational arguments can all help in convincing us that the Church is true, the scriptures state that it is through repentance and obedience, we can all come to know God:

“[E]very soul who forsaketh his sins and cometh unto me, and calleth on my name, and obeyeth my voice, and keepeth my commandments, shall see my face and know that I am” (D&C 93:1). That is not to say that all of us will attain this level of knowledge or surety in this life. For almost all of us, knowledge of God in this life comes as a spiritual manifestation:

“[I]nasmuch as you strip yourselves from jealousies and fears, and humble yourselves before me, … the veil shall be rent and you shall see me and know that I am—not with the carnal neither natural mind, but with the spiritual” (D&C 67:10).

Knowing because others know

Still, while some receive direct spiritual knowledge of the divinity of Jesus Christ, others are gifted in believing on the testimony of others:

“To some it is given by the Holy Ghost to know that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, and that he was crucified for the sins of the world. To others it is given to believe on their words, that they also might have eternal life if they continue faithful” (D&C 46:13-14).

And although believing in the words of others would seem to be a lesser form of knowledge, the sons of Helaman were free from doubt because of the knowledge of their mothers. Their conviction was so strong that God would deliver them, that “they did not fear death”.[77] As they expressed it to Helaman:

“We do not doubt our mothers knew it” (Alma 56:48).

Of course, no one should lose heart if they yearn for a sure knowledge and yet still lack conviction. Those elders who were told that they could have a vision of God were also told,

“Ye are not able to abide the presence of God now, neither the ministering of angels; wherefore, continue in patience until ye are perfected” (D&C 67:13).

And some of those who were ordained to the high priesthood of the Church were told,

“ye cannot bear all things now; nevertheless, be of good cheer, for I will lead you along. The kingdom is yours and the blessings thereof are yours, and the riches of eternity are yours” (D&C 78:18).

CONCLUSION

From this analysis of the scriptures, it should be clear that we should not shy away from presenting evidence that the Church is true. God intends to prove to us that He lives, that Jesus is the Christ, and that the Church has been restored in the latter days. It is unusual to find an instance in which God Himself appears to make His case.[78] The primary way by which God proves His case is through the testimony of his servants.

For that reason, we should “be ready always to give an answer to every man that asketh you a reason of the hope that is in us” (1 Pet. 3:15)

In fact, most modern translations of that verse use the word “defense” instead of “answer” as the word in greek is ἀπολογίαν (apologian) and commonly refers to “[a] verbal defense (particularly in a law court).”[79] In other words, Peter here calls on us to be apologists for our faith and to set out a defense of our beliefs as one might defend a case in a court of law.

Conviction vs Conversion

As the scriptures indicate that we can prove that the Church is true, it raises a question regarding why it has not been done. In other words, why doesn’t everyone believe?

We might as easily ask the critics of the Church, have you proven that the Church is not true, and if so, why is the Church still around? The question might not be one so much of belief, as conviction, commitment, and loyalty. As James wrote, “Even the demons believe—and tremble!” (James 2:19).[80]

So although one may be convinced, one may not be converted. Austin Farrer alluded to this when he wrote that “argument does not create conviction,” and “[w]hat seems to be proved may not be embraced.”[81]

As we contemplate why a person may be unable to refute an argument, and may even be intellectually persuaded, but remain unconverted, it could help to consider an anecdote related by John Stackhouse in his introduction to his book, Humble Apologetics. He tells of an expert apologist who visited a college campus and handily refuted every argument raised by each person who challenged him. Nevertheless, a student was overheard saying as she was leaving the event, “I don’t care if the son of a [gun] is right, I still hate his guts”[82] (But she didn’t say “son of a gun.”)

Self-interest is a factor

The reason that argument does not always create converts may be related to the reason an individual should be excluded from a jury if they have a self-interest in the outcome of the litigation.[83] If a member of a jury in an automobile injury case was going to gain or lose something depending upon whether the plaintiff was able to prove the case, the person would be excluded from serving on the jury. They cannot fairly assess the evidence if they have “skin in the game.” Their motivation will be to give more weight to the evidence that supports their personal interest and to reject evidence that does not.

With respect to religion, we all have skin in the game. In other words, if the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is really Christ’s restored Church, it may cause serious cognitive dissonance and psychological pain in the mind and heart of one who would rather not join the Church due to a host of considerations unrelated to the question of whether or not the Church is true. Joining the Church often involves great sacrifices, and it takes not only a change of mind but a mighty change of heart before one is willing to make those sacrifices.

Our Desire to believe is a factor

The social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has explained: “Reasoning can take us to almost any conclusion we want to reach, because we ask, ‘Can I believe it?’ when we want to believe something, but ‘Must I believe it?” when we don’t want to believe. The answer is almost always yes to the first question and no to the second.”[84] This is why so much, perhaps everything, depends upon our desires.

We are told that we will be judged according to our desires (D&C 137:9), and that we will be rewarded according to our desires (D&C 88:32; Psalm 37:4).

Do we hope the church is true?

Whether or not we develop faith and are converted to the Church may depend in large part upon whether we hope the Church is true.

As Moroni asks, “How is it that ye can attain unto faith, save ye shall have hope?” (Mor. 7:40). If we do not want the Church to be true, we will look for reasons to support our desires and justify disbelief. So one way to reach people would be to help them to see how beautiful and desirable the truths taught in the Church are. That the gospel really is “good news.” That can help them to begin to desire to believe.

Conversion: by the Spirit or by Evidence

It often seems as though some want to pit conversion by the Spirit against conversion by evidence and argument as if it is an either-or proposition. However, the Spirit does not operate in a vacuum. It does not seem possible that one could be converted by the Spirit without having been given reasons to believe. At the very least, evidence provides a reason for seeking spiritual confirmation and a reason to continue seeking spiritual strength after once receiving a witness of the Holy Ghost.

Of course, evidence does not need to be in the form of a logical argument or even an appeal to the authority of the scriptures. As demonstrated above, proof may come through a variety of means including simply that a person becomes converted through the experience of living the gospel, such as learning that through fellowship with the saints, good things are brought to pass. And once one has been given reasons to believe, the Spirit can confirm the truth of the evidence.[85]

As B.H. Roberts stated: “To be known, the truth must be stated and the clearer and more complete the statement is, the better opportunity will the Holy Spirit have for testifying to the souls of men that the work is true.”[86] To this, Elder Roberts added,

“The power of the Holy Ghost . . . must ever be the chief source of evidence for the truth of the Book of Mormon. All other evidence is secondary. . . . No arrangement of evidence, however skillfully ordered; no argument, however adroitly made, can ever take its place.”[87]

Lack of evidence or lack of desire?

We are also told that the Holy Ghost can change our hearts so that “we have no more disposition to do evil, but to do good continually” (Mos. 5:2). So although the truthfulness of the gospel can be proven, it seems that the most important function evidence serves is in providing reasons for people to hope that the Church is true, or to continue to believe, who already have the desire to believe. The evidence will have little tendency to cause a person to change their behavior if they do not want to change their behavior. Such a person may claim that there is a lack of evidence when the larger issue is a lack of desire.

Of course, once a person has a desire to believe, they must also have reasons to support that belief. Along these lines, Farrer’s oft-quoted sentiment may be modified as follows:

“For though argument does not [cause conversion], the lack of it destroys belief. What seems to be proved may not be embraced; but what no one shows the ability to defend is quickly abandoned. Rational argument does not [convert people], but it maintains a climate in which belief may flourish [into conversion]”[88]

Belief and conviction must be accompanied by desire and evidence

Belief and conviction will flourish into conversion when accompanied by both desire and evidence. It is therefore crucial if people are to develop and maintain a conviction that blossoms into conversion that we are ready “always to give an answer to every man that asketh you a reason of the hope that is in” us (1 Pet. 3:15).

That is why I am grateful to all of you and to all of the organizations that are supporting the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints through scholarship.

Thank you.[89]

No Q&A was provided for this presentation, as time did not allow.

[1] “Painted in Rome by one of the outstanding Venetian masters of the High Renaissance, this badly damaged portrait purports to show Christopher Columbus. The inscription identifies him as “the Ligurian Colombo, the first to enter by ship into the world of the Antipodes 1519,” but the writing is not entirely trustworthy and the date 1519 means that it cannot have been painted from life, as Columbus died in 1506. There are other, quite different, portraits that also claim to show Columbus. Nonetheless, from an early date our picture became the authoritative likeness. In 1814 the painting was part of the collection of Prince Talleyrand and was exhibited at the Palais Royal in Paris.” https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437645

[2] Douglas L. Callister, “Knowing That We Know,” Ensign, October, 2007.

[3] See https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/know

[4] See https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/true.

[5] For various definitions, see https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/church.

[6] D. Todd Christofferson, “Why the Church,” General Conference, October 2015.

[7] Ibid.

[8] In his book The Sin of Certainty, Peter Enns warns against being certain of our own interpretation of the scriptures as we may become inflexible and lose our trust in God if that trust is tied to an understanding of doctrine or history that we later come to find is incorrect. I have personally found that I can be certain that the doctrine of the Church is correct while remaining uncertain of my ability to understand it. In this way, I have maintained confidence in the Church and its leaders while remaining flexible in my beliefs about what actually occurred in history and why, or what the scriptures actually mean. Where Enns gets it wrong is when he argues that there is no use in intellectual arguments in favor of God. What Enns fails to take account of is how we are to develop trust in God in the first place and how we can maintain that trust in the face of intellectual arguments against God. Enns seems to respond by saying, “just trust God.” But he fails to explain how this is possible without good reasons for doing so. See Peter Enns, The Sin of Certainty: Why God Desires Our Trust More Than Our “Correct” Beliefs, (New York, NY: Harper One, 2016)

[9] Hugh W. Nibley, Since Cumorah, 2d. ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), xiv.

[10] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/proof

[11] Cupillari, Antonella, The Nuts and Bolts of Proofs: An Introduction to Mathematical Proofs (Third ed.). (Academic Press, 2005), 3

[12] D&C 29:36

[13] James 2:19 NKJV.

[14] Mos. 1:39.

[15] Abr. 3:25-26.

[16] In addressing the question of why God does not provide more evidence, Christian apologist William Lane Craig responded, “God will not allow a person to be lost if He knew that the provision of more evidence would win that person’s free assent. God will providentially order

the world so that anyone who fails to believe in God for salvation would not have believed in Him were he to be given more evidence. Certainly, more evidence might convince such a person that God exists. But that’s no big deal. What matters is saving faith. And it may well be the case that a loving God would not withhold from anyone the evidence that would suffice to bring him freely to saving faith. So anyone who fails to come to saving faith would not have come even if he had been given more evidence.” William Lane Craig, “Not Enough Evidence to Believe,” The Good Book Blog, Biola University, July 19, 2019, https://www.biola.edu/blogs/good-book-blog/2019/not-enough-evidence-to-believe.

[17] 1 Cor. 10:13.

[18] See, e.g. 2 Cor. 9:7; Moroni 7:6-10; D&C 18:38; D&C 64:34; D&C 88:32; D&C 137:9; Abr. 3:25.

[19] See https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/prove

[20] See https://www.etymonline.com/word/prove

[21] Quoted in Rob Hodge, “Museums and attacks from cyberspace: Non-linear communication in a postmodern world,” Museum and Society, 9(2) p. 114. Similarly, Karl Popper wrote “we have no proofs in science (excepting, of course, pure mathematics and logic). In the empirical sciences, which alone can furnish us with information about the world we live in, proofs do not occur, if we mean by ‘proof’ an argument which establishes once and for ever the truth of a theory.” Theobald, Douglas (1999–2012). “29+ Evidences for Macroevolution”. TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 6 March 2022. Albert Einstein similarly stated, “The scientific theorist is not to be envied. For Nature, or more precisely experiment, is an inexorable and not very friendly judge of his work. It never says ‘Yes’ to a theory. In the most favorable cases it says ‘Maybe’, and in the great majority of cases simply ‘No’. If an experiment agrees with a theory it means for the latter ‘Maybe’, and if it does not agree it means ‘No’. Probably every theory will someday experience its ‘No’—most theories, soon after conception.” Gaither, Carl (2009). Gaither’s Dictionary of Scientific Quotations. New York, NY: Springer. p. 1602.

Regarding whether one can be certain of religious claims, Blaise Pascal stated: “If we must not act save on a certainty, we ought not to act on religion, for it is not certain. But how many things we do on an uncertainty, sea voyages, battles! I say then we must do nothing at all, for nothing is certain, and that there is more certainty in religion than there is as to whether we may see to-morrow; for it is not certain that we may see to-morrow, and it is certainly possible that we may not see it.” Wikisource contributors, “Page:Blaise Pascal works.djvu/95,” Wikisource , https://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=Page:Blaise_Pascal_works.djvu/95&oldid=7866402 (accessed March 6, 2022). It is interesting to compare Pascal’s statement on certainty with that of Gordon B. Hinckley, who said “Certitude, which I define as complete and total assurance, is not the enemy of religion. It is of its very essence,” and that of David O. McKay, who said “As absolute as the certainty that you have in your hearts that tonight will be followed by dawn tomorrow morning, so is my assurance that Jesus Christ is the Savior of mankind, the Light that will dispel the darkness of the world, through the gospel restored by direct revelation to the Prophet Joseph Smith.” Gordon B. Hinckley, “Faith: The Essence of True Religion,” Ensign, October 1995.

[22] “Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/goedel-incompleteness/

[23] John D. Barrow, The Artful Universe, (Oxford University Press, 1995), 211.

[24] https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/index.html#:~:text=CDC%20estimates%2048%20million%20people,year%20in%20the%20United%20States.

[25] Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, (West Valley City, Utah: Bookcraft, 1999) 2:124.

[26] Simon Greenleaf, The Testimony of the Evangelists: The Gospels Examined by the Rules of Evidence (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregal Classics, 1995), 41-42. See also Craig A. Parton, Religion on Trial (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2008), 34 (“History, law and science are never 100% certain of their conclusions. They must always have some sense of humility and openness to being shown they are wrong and in need of correction if the facts turn out to be otherwise, Regardless of this, though, we continue to make life and death decisions based on probability reasoning and less than 100% evidence. Thus we condemn people to death by lethal injection and do life-threatening surgery based on weighing probabilities and coming to a decision based on less than 100% certainty of what the facts might be in a given court case or medical diagnosis.

Every day in the courts of the United States people award millions of dollars to victims or litigants based on the weighing of evidence. Therefore, when we come to historically based religious claims we should expect nothing different.”).

[27] Manual of Model Civil Jury Instructions For the District Courts of the Ninth Circuit, Prepared by the Ninth Circuit Jury Instructions Committee, 2017 Edition, Last Updated September 2021. https://www.ce9.uscourts.gov/jury-instructions/sites/default/files/WPD/Civil_Instructions_2021_9_0.pdf The jury instructions quoted herein are taken from the same set of instructions. The Ninth Circuit Jury Instructions are used here for illustrative purposes since the Ninth Circuit is the largest of the federal circuits. However, a comparison among the other federal circuit courts of the rules cited here would demonstrate that these particular instructions are substantially the same across the country. To compare, this site provides links to nearly all of the model jury instructions: https://libraryguides.law.marquette.edu/c.php?g=318617&p=3806593 Where model jury instructions exist, judges are highly reluctant to instruct a jury in any other way. However, note that some courts, such as those in the Tenth Circuit, do not have model jury instructions, so the parties must rely on the model instructions of other courts or they must create their own instructions based on their understanding of the law. After proposed instructions are submitted to the court, the judge has the final say on how the jury will be instructed.

[28] It may be helpful here to note that the word “probable” appears as early as the 14th century and is said to mean “likely, reasonable, plausible, having more evidence for than against”. Etymonline.com, 2022. Online Etymology Dictionary. Available at https://www.etymonline.com/word/probable [Accessed 3 March 2022].

[29] Fed. R. Evid. 48(b).

[30] Ramos v. Louisiana, 140 S. Ct. 1390 (2020).

[31] Bureau of Justice Statistics, State Court Organization 1998, Table 42, available at https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/sco9806.pdf [Accessed 5 January 2022]

[32] Note that there are a few other standards of proof, but it is sufficient for our purposes to briefly touch on these three. For a short discussion of various standards of proof, see: https://www.justia.com/trials-litigation/lawsuits-and-the-court-process/evidentiary-standards-and-burdens-of-proof/

[33] See, e.g. 1 Ne. 13:39, 1 Nephi 14:7, 2 Nephi 25:18, 2 Nephi 26:12, Helaman 5:50, D&C 11:21

[34] See also Matt. 18:16.

[35] Other examples include: 2 Nephi 27:12-14; 2 Nephi 29:8; Ether 5:2-4.

[36] Other examples include: Doctrine and Covenants 6:28; Doctrine and Covenants 17:1-6; Doctrine and Covenants 76:22; D&C 107: 23 & 25; Doctrine & Covenants 128:20.

[37] See, e.g., Utah R. Civ. P. 47(f)(4). As an example of the kinds of reasons jurors can be excluded from serving, Rule 47 of the Utah Rules of Civil Procedure lays out the following grounds that would justify dismissal:

(f)(1) A want of any of the qualifications prescribed by law to render a person competent as a juror.

(f)(2) Consanguinity or affinity within the fourth degree to either party, or to an officer of a corporation that is a party.

(f)(3) Standing in the relation of debtor and creditor, guardian and ward, master and servant, employer and employee or principal and agent, to either party, or united in business with either party, or being on any bond or obligation for either party; provided, that the relationship of debtor and creditor shall be deemed not to exist between a municipality and a resident thereof indebted to such municipality by reason of a tax, license fee, or service charge for water, power, light or other services rendered to such resident.

(f)(4) Having served as a juror, or having been a witness, on a previous trial between the same parties for the same cause of action, or being then a witness therein.

(f)(5) Pecuniary interest on the part of the juror in the result of the action, or in the main question involved in the action, except interest as a member or citizen of a municipal corporation.

(f)(6) Conduct, responses, state of mind or other circumstances that reasonably lead the court to conclude the juror is not likely to act impartially. No person may serve as a juror, if challenged, unless the judge is convinced the juror can and will act impartially and fairly.

[38] See also, Moroni 7:16-17 (“I show unto you the way to judge; for every thing which inviteth to do good, and to persuade to believe in Christ, is sent forth by the power and gift of Christ; wherefore ye may know with a perfect knowledge it is of God. But whatsoever thing persuadeth men to do evil, and believe not in Christ, and deny him, and serve not God, then ye may know with a perfect knowledge it is of the devil; for after this manner doth the devil work, for he persuadeth no man to do good, no, not one; neither do his angels; neither do they who subject themselves unto him.”); D&C 93: 26-28 (“[Christ] received a fulness of truth, yea, even of all truth; And no man receiveth a fulness unless he keepeth his commandments. He that keepeth his commandments receiveth truth and light, until he is glorified in truth and knoweth all things.”)

[39] We are also told that our knowledge of light and truth can be diminished through disobedience: “And that wicked one cometh and taketh away light and truth through disobedience, from the children of men, and because of the tradition of their fathers.” (D&C 93:39.) See also, Alma 12:10-11 (And therefore, he that will harden his heart, the same receiveth the lesser portion of the word; and he that will not harden his heart, to him is given the greater portion of the word, until it is given unto him to know the mysteries of God until he know them in full. And they that will harden their hearts, to them is given the lesser portion of the word until they know nothing concerning his mysteries; and then they are taken captive by the devil, and led by his will down to destruction. Now this is what is meant by the chains of hell.”)

[40] See also, John 15: 26 (“But when the Comforter is come, whom I will send unto you from the Father, even the Spirit of truth, which proceedeth from the Father, he shall testify of me.”); Rom. 8:16 (“The Spirit itself beareth witness with our spirit, that we are the children of God.”); Heb. 10:15 (“Whereof the Holy Ghost also is a witness to us.”); 1 Jn. 5: 6, 8-9 (“This is he that came by water and blood, even Jesus Christ; not by water only, but by water and blood. And it is the Spirit that beareth witness, because the Spirit is truth…. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one. If we receive the witness of men, the witness of God is greater: for this is the witness of God which he hath testified of his Son.”).

[41] 2 Ne. 11:3 & 6; 2 Ne. 27:12-14; Ether 5:4

[42] See also Title Page and 2 Ne. 29:9.

[43] D&C 20:11; Paul also counsels the Roman saints to transform themselves in a way that contrasted with what the world expected in order to prove God’s will through their example. Rom. 12:2.

[44] 2 Ne. 11:4; Jacob 4:6; D&C 11:21; Acts 9:20-21; Acts 18:27-28 (NIV).

[45] Alma 34: 6-7. It is sometimes said that an appeal to authority is a logical fallacy. However, this is only so when the person whose authority is invoked is not actually an authority in the area. Hansen, Hans, “Fallacies”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/fallacies/>. If the audience agrees that a source is authoritative, the appeal to the source is not considered fallacious. So in these cases, Alma and Jacob appeal to the words of prophets in order to prove that Christ is our Savior, which can be a persuasive method when the audience accepts beforehand the authority of the prophets. Otherwise, this approach would be ineffective. One of the most common ways by which we come to know things is through the teaching of authorities as this is the primary mode of instruction in our schools. Furthermore, expert witnesses are often called upon in our courtroom trials and are allowed to testify so long as other threshold requirements are met, such as that the testimony is relevant, and so long as the judge finds that the witness meets the qualifications of an expert as set forth in Federal Rule of Evidence 702: “A witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise if: (a) the expert’s scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue; (b) the testimony is based on sufficient facts or data; (c) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and (d) the expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case.” While a prophet is not a prophet by virtue of scientific or technical knowledge, a prophet certainly has another kind of knowledge and experience, and often has skill, training and education in the areas of administration and the scriptures themselves. That is not to say that a prophet would be called as an expert witness in a modern court of law as a prophet. Expert testimony must meet a standard that depends upon scientific and technical standards that do not apply to those who receive revelation from God, such as “including whether the theory or technique in question can be (and has been) tested, whether it has been subjected to peer review and publication, its known or potential error rate and the existence and maintenance of standards controlling its operation, and whether it has attracted widespread acceptance within a relevant scientific community.” Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579, 580 (1993).

[46] See also Helaman 8:24.

[47] Malachi 3:10.