Summary

Summary

Stephen Smoot argues that Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo-era cosmology can be meaningfully “grounded” in Genesis 1 by reading the chapter the way many modern biblical scholars do: as God organizing pre-existing chaos into an ordered, functional cosmos (not creating matter ex nihilo). He then claims Genesis 1’s “image of God” language implies an anthropomorphic, embodied deity and that the “Let us make” phrasing reflects a divine council/plurality—both of which the speaker says converge strongly with Joseph Smith’s teachings.

Introduction

Introduction

Stephen O. Smoot is a doctoral candidate in Semitic and Egyptian Languages and Literature at the Catholic University of America.

He previously earned a master’s degree from the University of Toronto in Near Middle Eastern Civilizations with a concentration in Egyptology, and a bachelor’s degree from BYU in Ancient Near Eastern Studies with a concentration in Hebrew Bible and German Studies.

He is currently an adjunct instructor of religious education at Brigham Young University and a researcher at the Ancient America Foundation.

Presentation

Introducing the Outline of this Presentation

Stephen Smoot: I’m very grateful to be here at this virtual conference being sponsored by FAIR. I appreciate the opportunity to speak on this topic that I find immensely interesting, and I hope you do as well.

The subject for my paper is on grounding the cosmology of Joseph Smith and the Latter-day Saints in the text of Genesis chapter 1. Since this is an Old Testament conference, I thought this would be an appropriate subject, as it’s one that many people keep coming back to and having questions about.

So, let’s explore a couple of points on how I believe Joseph Smith’s teachings—especially those he developed in the Nauvoo period in the King Follett discourse and in other places—how we might ground that in biblical cosmology, and how we can find convergence with the book of Genesis and the cosmology presented in the book of Genesis.

Three Key Foundational Elements of Latter-day Saint Cosmology

Stated briefly for my abstract, we want to look at three key foundational elements of Latter-day Saint cosmology that I believe can be supported from the text of Genesis chapter 1.

The first is that of creation from pre-existing matter, or in other words, a rejection of the teaching of creation ex nihilo.

The second being the concept of the imago Dei, man being made in the image of God found in Genesis chapter 1:26. My argument, as is pertinent to Latter-day Saint cosmology, is that this includes not only a moral or spiritual likeness, which is what you commonly find in Orthodox Christian and Jewish teaching, but also indeed connotes a physical or anthropomorphic dimension, which aligns nicely with the Latter-day Saint understanding of an embodied deity.

And then finally, number three, I want to look at the plural language of Genesis 1:26 again to discuss the presence of a divine plurality in the text of Genesis 1, which argues against a strict ontological monotheism, as I would say.

So, I would refer listeners to the full version of my comments that will be published in the proceedings of this conference. For the purposes of time, I’m only able to touch on these points.

But if you’d like to see my fuller argument developed, I’ll refer you to the written published version, which should be appearing hopefully shortly after the time of this conference.

Genesis Chapter 1 and Joseph Smith

So, let’s jump right into it. Let’s start with Genesis chapter 1 and Joseph Smith.

One thing we see with Joseph Smith is that he is constantly returning back to Genesis chapter 1 and engaging with this text in different ways.

So we have, of course, our Book of Moses, which is a part of Joseph Smith’s inspired translation of the Bible. We have our Book of Abraham, which also includes a recontextualized version of Genesis chapter 1 in the context of this Abrahamic narrative.

We have Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo temple liturgy, where elements of Genesis chapter 1 are incorporated into the Latter-day Saint temple endowment.

And of course, in Joseph Smith’s famous King Follett discourse, he touched on themes from Genesis 1. He read from the Hebrew of Genesis 1 and discussed that.

Genesis 1–to Joseph Smith–was not just a “literal history” in the sense that he only took it in this very narrow literal sense.

Genesis 1 as a Springboard

For Joseph Smith, Genesis 1 acted as a springboard for doctrinal and even liturgical development.

We see its liturgical use in the temple and in the endowment ritual. We see him using it in his translations in the Book of Moses and in the Book of Abraham, and in his sermons.

And so I find it interesting and significant that Joseph Smith keeps coming back to Genesis 1 and uses Genesis 1 as a basis for his cosmology. The purpose of this paper, as I said, was to explore those convergences.

Before we jump into that, though, let’s take a step back and do a broad review of Genesis chapter 1.

The Creation in Genesis 1

Modern biblical scholars today actually kind of divide what is commonly called the priestly creation account, starting from Genesis 1:1 and going to 2:4.

So if you pick up a modern study Bible, you will frequently see this unit of text is separated as a pericope as the so-called ‘priestly creation account’. 1

This language of calling it a ‘priestly account’ goes back to the classical documentary hypothesis that most biblical scholars today (to some degree) accept or countenance.

Temple Context and Priestly Language

The Sitz im Leben of this priestly creation account is widely thought to perhaps be the Jerusalem temple. I know some scholars who have even gone so far as to suggest that perhaps the Genesis account was reenacted or recited in the Jerusalem temple at different occasions.

This would have parallels with our Mesopotamian creation myths like Enuma Elish, which was recited at the Akitu festival.

There are other reasons why we think it may have its context in the Jerusalem temple, and we’ll touch on this a little bit later. But basically, a lot of the language and structure of Genesis 1 seems to be mirroring priestly or temple ideas.

Language and concepts seem to be mirroring what the ancient priests in Israel were concerned with, and it seems to revolve around that.

There’s also this sense that Genesis 1 is actually describing, in some sense, the creation of a cosmic temple, that God is inaugurating the cosmos as his temple at this moment of creation.

So for all these and other reasons, if we just look at it broadly, this is what we’re talking about here.

Scholarly Context and Purpose

In my paper and in other sources, there’s plenty of scholarship on this that has touched on these sorts of topics. For our purposes we’ll just mention it here briefly and highlight it.

The Structure of Genesis 1

So let’s look at, real quick, the structure of Genesis chapter 1. Famously, of course, we have six days of creation and a seventh day of rest in the priestly account.

And by the way, that’s the language I’ll just be using here. That’s kind of the de facto language that scholars use commonly to describe Genesis 1, the priestly account of creation.

We find something interesting. Basically, the way the days are structured in Genesis 1 is where—at first—God forms the different constituent parts of the cosmos. And then, he fills them.

And there’s a nice symmetry there where:

- He creates the different aspects of the physical cosmos, and

- He fills those different realms or aspects of the physical cosmos.

There’s lots of verbal repetition. There’s very deliberate and concise and close literary composition happening in Genesis chapter 1.

This is by no means a haphazard account. A lot of intentionality and deliberateness went into the literary craft and the structure of Genesis chapter 1 on a literary level.

And again, that has been explored at length in any of the standard biblical works on Genesis 1.

Some Syntax Issues in Genesis 1

So before we go day by day through Genesis, which I want to do here in just a moment, we need to lay some groundwork on some difficulties with Genesis chapter 1.

First of all, the Hebrew syntax of the first three verses of Genesis actually kind of hits you right in the face in terms of the complexity and some ambiguity in terms of how to actually render this passage from Hebrew to a modern language like English.

Most Latter-day Saints are used to the King James Bible and the King James rendering of Genesis. That’s sort of deceptively simple, the way that the King James translators rendered it.

So without getting too much in the weeds here, basically the operative phrase here that we have questions about is actually the very first word.

- Bereshit, in the Hebrew of Genesis;

- “In the beginning,” as it is commonly translated.

Bereshit and Competing Readings of Genesis 1:1

Ever since the Middle Ages, scholars have disputed whether or not Bereshit bara Elohim is marking an absolute finite clause. So this is what you get in your standard translations: “In the beginning, God created,” a definite, absolute finite clause. Or, is it a dependent temporal clause, acting sort of adverbially: “When God began to create.”

And in this case Bereshit bara would be in a construct form. So,

- “When God began to create,” or

- “When God began creating the heavens and the earth.”

There are arguments for both readings. Very good Hebraicists have argued for both sides of this argument since the Middle Ages, so this isn’t a new controversy.

However, scholarly consensus today favors the latter reading of it being a construct and thereby a dependent temporal clause.

If you open up any study Bible or academic edition of the Bible, you’ll see scholarly notes on this, or notes on the translation, where most of these modern versions tend to favor that.

Full disclosure, that’s the version that I favor as well. I think it’s most likely a dependent temporal clause, which we’ll discuss the significance of in a minute here.

But just be aware: if you consult different Bible translations, you may find some difference in your translation, and that may be significant.

The Verb Bara and the Nature of Creation

We have this question of what kind of syntax is happening here. There’s also the question of how do we render a verb like bara? Traditionally (bara is) rendered or translated as “to create.” That’s a fine enough translation to get the sense that God is indeed fashioning or creating something. There’s no problem there.

This verb occurs exclusively with God as a subject in the Hebrew Bible. I know some people have tried to make a lot out of this. I don’t think we necessarily need to go that far. It’s just how it’s only attested being used with God in the Hebrew Bible. I’m not sure how intentional that may have been versus simply sort of an accident of preservation.

But in any case, what kind of creation are we talking about here with a verb like bara? Because there’s others that biblical authors can use and do use. He can use asah, he can use yatsar, he can use different verbs, qanah.

But in Genesis 1, the main verb he’s using here is bara.

The best argument that I’ve seen is that we’re talking about acts of differentiation and separation.

Some lexicons, when they discuss this, think it may go back to an early root meaning “to cut” or “to fashion.” That’s a possibility.

Whatever the etymological origins of the verb, Genesis 1 is clearly describing God separating elements—light from darkness, waters above from waters below, the sea from the land, and so forth. And this leads scholars, including myself, to see bara as a verb emphasizing God’s role in assigning boundaries or roles, and not so much about him bringing material entities into existence from non-existence.

That’s a philosophical extrapolation that some have taken on this language. I don’t necessarily think that may be the case. And we’ll discuss this a little more in a second.

Day 0: The Uncreated Status of the Cosmos

So let’s start. With all that groundwork laid, with all that throat clearing that I’ve done here, let’s begin. I decided to go ahead and throw up the New Revised Standard Version, the updated edition that came out this year or last year, with the Hebrew on the right:

“When God began to create the heavens and the earth”—there it is, right? A dependent temporal clause—“The earth was complete chaos.”

It was Tohu wa-bohu . . . and darkness (hosek) covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God . . . ruah elohim, sometimes translated as the Spirit of God or a Divine wind . . . “swept over the face of the waters.”

“Then God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light.”

So taking the vav there, the conjunctive, as a “then God said,” as opposed to “and God said.”

You can see the difference here between your usual King James translation. Probably, Latter-day Saints aren’t too familiar with this rendering here. But this probably seems to capture a more technical aspect of the Hebrew.

And this is sort of describing day zero, if you will—the uncreated status of the cosmos before God is going to pronounce the creation of light, in day one.

Primordial Chaos and the Beginning of Creation

So if you read the Hebrew in this way, which I think is probably the correct way to read it, this implies that verse two is describing the Tohu wa-bohu, the complete chaos.

The hosek, the darkness upon the face of the Tehom, the deep, the primordial deep.

And a wind of God, a ruah elohim, is râchaph, sweeping or brooding over the face of the waters.

So you get this picture of primordial chaotic waters that God is beginning to sort of vivify with his divine presence, which will kickstart creation—the first act of which will be God saying, “Let there be light.”

So, “day zero”, let’s call it – uncreated cosmos. As I’ve said, this evokes a sense of a formless, uninhabitable state. This motif is ubiquitous across ancient Near Eastern cosmogonies, both from Mesopotamia and from ancient Egypt.

This is what leads many scholars, including myself, to situate the priestly account in this cultural milieu, where we see a primordial darkness, a primordial chaos, that God is beginning to insert his divine force into—his divine presence—with his spirit, as he begins to effect the creation.

So that’s day zero.

Day One: Light

Day one is the creation of light. And God said, “Let there be light: and there was light.”

What’s interesting, however, is that there’s no physical source for this light because the sun and the moon, they’re not going to be created until day four.

So we are prioritizing light in our priestly creation account as the foundational role of this cosmology. It’s to initiate time itself and all the subsequent acts of creation that will proceed from that.

And God is going to name day and night. He’s going to establish these different domains through language, another theme that occurs here. He’s going to speak and name these different domains through spoken language.

So day one: creation of light, not the creation of the heavens and the earth. They’re already in a primordial chaos on day one when the light emerges.

Day Two: Firmament

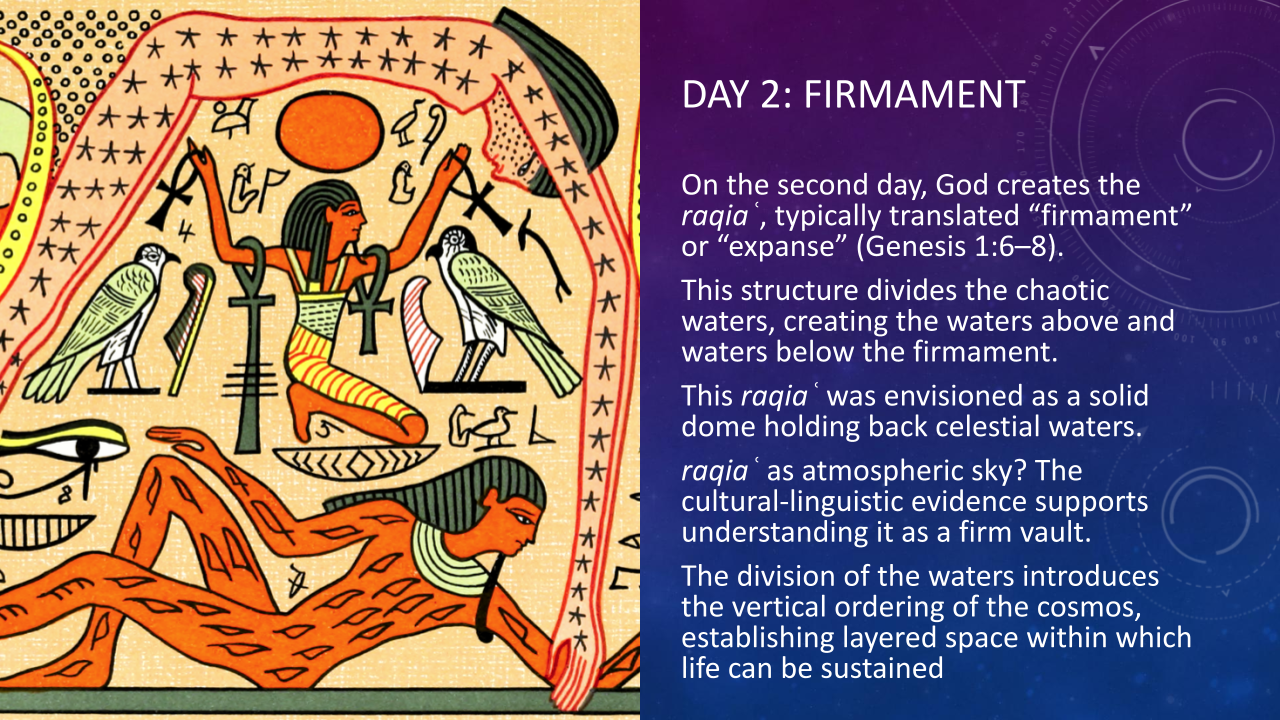

Day two is going to be the creation of the firmament, the raqia, typically translated as “firmament” or “expanse” in different translations. The purpose of this dome, this firmament, this expanse, is to divide the chaotic waters above and below—the different aspects of the world that God is now creating.

And in the ancient Israelite mindset, this dome, this firmament, is envisioned as a solid dome holding back celestial waters.

I have this picture here. This is the famous Egyptian representation of the goddess Nut, the sky. She’s got the stars on her body. She’s being held up by Shu, who is air or wind, and below him is Geb, the god personifying earth.

So you have this domed arch that is being held up by the air and being supported by the earth. You’ll notice that she’s bent over, her arms are stretched over. This is a mythological conceptualization of it, but the Israelites had a similar idea.

It’s probably not referring to atmospheric sky. The cultural linguistic evidence supports this understanding as an actual firm vault of sorts.

So we have to be careful not to anachronistically impose these ideas like, “Well maybe the firmament is like the atmosphere,” or “outer space,” or something. No. It’s something specifically unique to the cosmologies of the ancient Near East.

And again, we’re vertically ordering the cosmos by dividing these waters into upper and lower waters, these upper and lower bounds.

So that’s day two: the firmament.

Day Three: Waters and Land

Day three: the lands are going to emerge.

Water is going to gather together into seas, and for the first time now the earth is going to become a stable, inhabitable realm where we’re going to have vegetation.

They’re not planted by anybody. They just emerge. They’re not planted or cultivated, but divine command brings out the vegetation.

The earth is now fertile and self-generating. And so plants and seeds and fruit are going to multiply after their kind, and different plants are going to have the different seeds inside them after their kind that will be able to reproduce.

So once we’re structuring the earth and the cosmos, now we can populate them with life, beginning here with plant life.

Day Four: Luminaries

Day four: we’re going to have the luminaries—the sun, the moon, and the stars—set in the firmament. And their explicitly stated purpose in Genesis is to keep time. They are for signs and for seasons and for days and for years.

And the Hebrew word used for seasons is moʿadim, which again refers to liturgical seasons. This is one of our giveaways that this priestly account is concerned with priestly things like priestly festivals or sacred festivals. So we have a theological calendar. This is the purpose of these luminaries.

The other purpose of the luminaries, in one interesting reading from one scholar who I cite, is that they act as membranes that are planted in the dome of the firmament in order to let light pass through the dome and illuminate the earth. So that’s kind of interesting there.

Notice that we don’t get names for these luminaries. They are simply “the great light” and “the lesser light.”

Some have suggested this may be subtly de-mythologizing ancient astral deities that you find at places like Ugarit or Mesopotamia. I think that’s a very real possibility.

In any case, these luminaries are not divinities and they are not independent divine beings, but they are subordinate instruments for God’s ordering of the universe.

Day Five: Sea and Avian Life

Day five: now we’re going to see the emergence of sea and avian life. We’re going to get fish and birds and all those good little critters.

My fun little note here is that we have the “great whales,” as the King James calls them, the tanninim gedolim. These are mythological sea monsters in places like ancient Ugarit.

So it’s interesting that the priestly author seems to be tapping into these mythological motifs, but he is recontextualizing them, where these are no longer these chaos monsters that potentially threaten God, as they are in Mesopotamia or in ancient Canaan, but rather they are part of the harmonious created order.

So whatever real-world entity this may be referring to, it’s kind of hard to tell. In their mythological context, these were like primordial sea drakes or sea serpents.

And all these creatures, they’re going to be commanded to be fruitful, multiply, foreshadowing the command that will later be given to humans on the next day.

This is also the first explicit blessing we get in the narrative, where we see God has a desire to perpetuate life. We see this in day five with the creation of these animals.

Day Six: Land Animals and Humans

Day six, of course, is when God makes humans, although he also makes land animals. He makes livestock, little insects, little critters, wild beasts. But the true apex of the creation of land animals and others is humanity.

So humans are made, but they are not made ‘according to their kind’ like the other animals were, like the plants were. They are made in the image and likeness of God. We’ll have a whole discussion of this here soon.

So this is setting humanity apart ontologically and functionally by being made in God’s image and not just in the generic sense of being after their kind.

Day Seven: Rest

Finally, of course, famously on the seventh day God rests. This is another indication of our priestly interest in this material because in other priestly writings there’s a significance attached to the Sabbath.

In fact, in the Ten Commandments this is explicitly evoked: God rested on the seventh day, therefore all the Israelites shall rest on the seventh day, and so forth.

We’re now changing from space to time, however. Notice that we’ve gone from creating and structuring the cosmos to now demarcating sacred time, which is blessed and sanctified by God.

He blesses it, and he sanctifies the seventh day.

Creation of a Cosmic “Temple”

So like I said earlier, all this is building up to the fact that Genesis is describing the creation of a cosmic temple.

Creation becomes what I like to call the space-time matrix of the holy, of sacredness, into which God is bringing in humanity. And the Sabbath is marking the fulfillment and consecration of this space-time matrix which God has created.

Genesis 1 Illustrates How the Israelite Cosmos Works

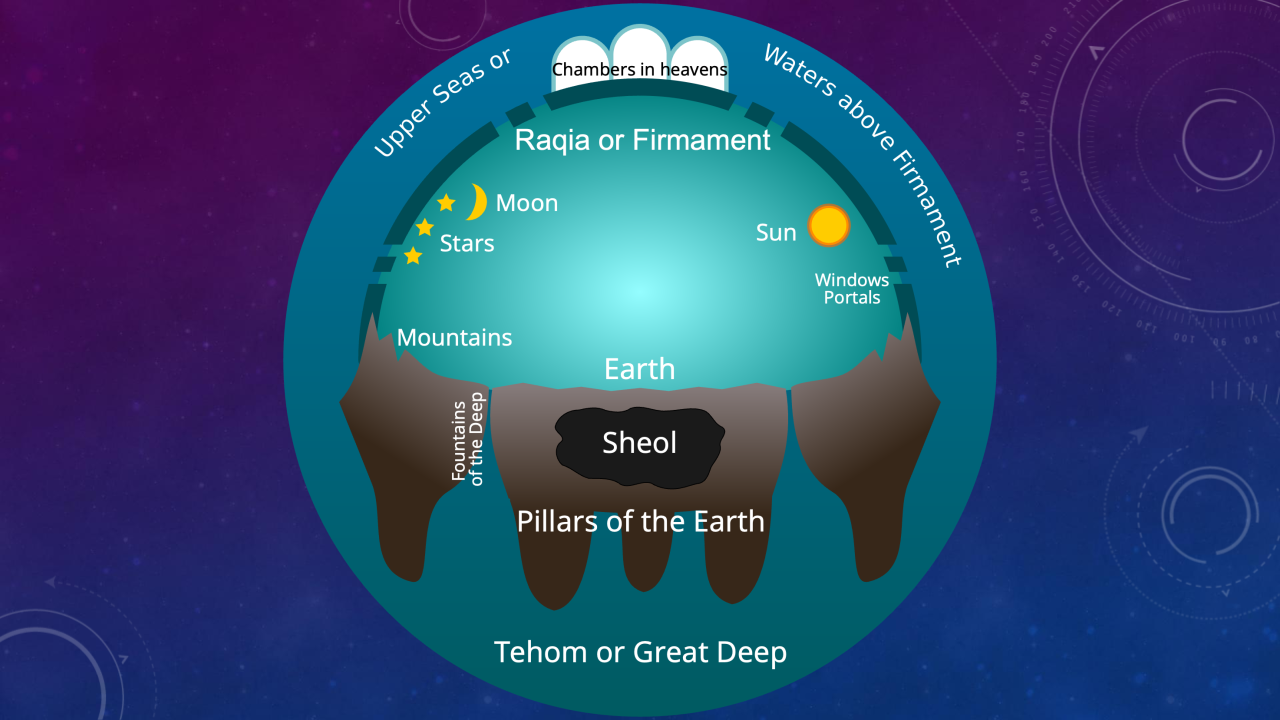

Now if you take Genesis 1 as a whole and you put all the constituent parts together, this is the worldview that the ancient Israelites have of how their cosmos works.

- We have the earth, which is most likely imagined as sort of a flat disc or plane. Underneath it is Sheol, the realm of the dead where all the dead go.

- We have tehom, the great primordial deep ocean on which the earth is resting.

- We have the raqia, the firmament, and embedded in that are the stars and the moon and the sun.

- And above them we have these waters, in which also we see God dwelling above the raqia.

So this is our picture, our cosmological picture, of what’s happening in Genesis chapter 1.

Ben Spackman is speaking at this conference. I will leave it to Ben Spackman to discuss more about what do we do with attempting to reconcile the scriptural text with modern science.

That’s a secondary concern for what we’re doing here. We just want to understand on its own terms what is happening with the Bible and with the biblical account of creation. So, I will leave it to others to discuss what we do with harmonizing this with science–if that’s the interpretive route we want to take.

But for our purposes, we’re not going to worry about that. We’re just going to understand and countenance that this is the cosmic picture that emerges from our text of Genesis.

The Big Picture of Genesis 1 and the Creation

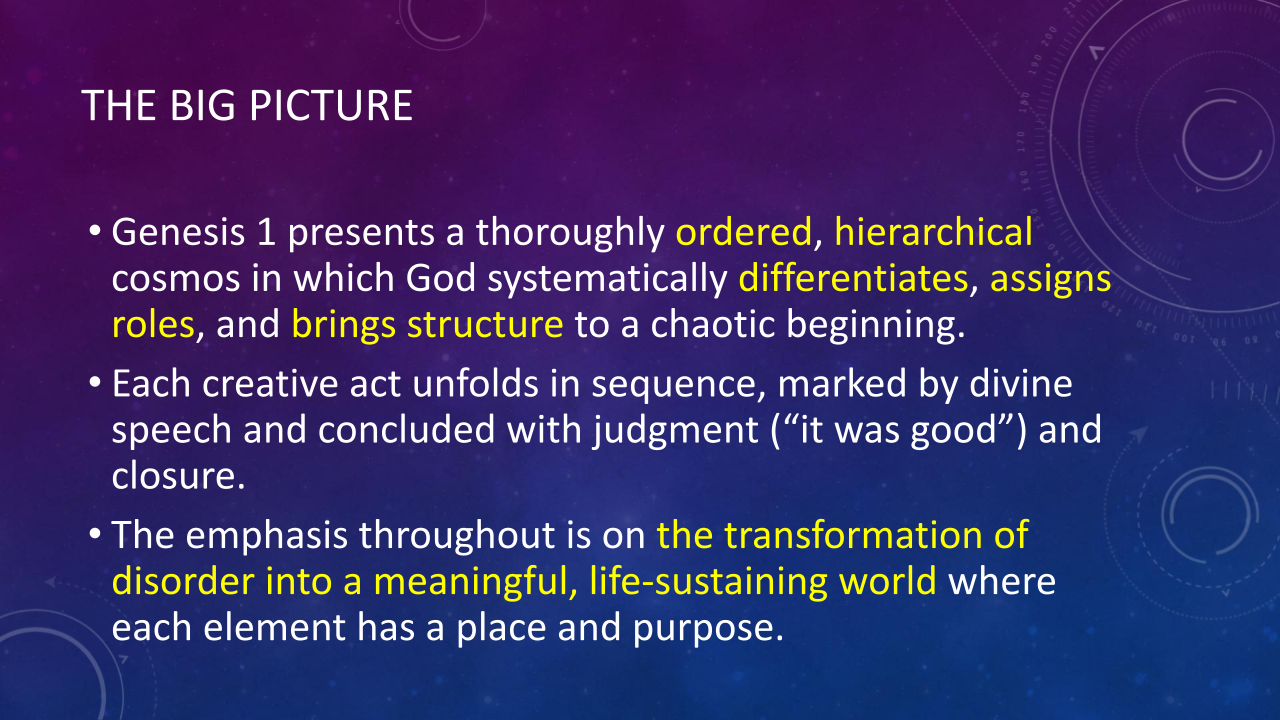

So big picture: Genesis is presenting an ordered hierarchical cosmos.

And the way God creates this is by systematically differentiating, assigning roles, and bringing structure to what was otherwise a chaotic pre-cosmos. A chaotic beginning.

Each creative act is unfolding in sequence. Again, this goes back to the highly structured nature of this account. It’s marked by divine speech and concluded with judgment and then closure, and then it proceeds to the next day.

The emphasis throughout the Genesis creation account is on the transformation of disorder into order: into a meaningful life-sustaining world where each element has a place and purpose.

That is, I would argue, the primary purpose of Genesis chapter 1. To give us this picture of how the cosmos works.

I would refer your attention to these two very good books by John Walton: The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate and Genesis One as Ancient Cosmology.

Walton, I believe, argues very persuasively that our Genesis creation narrative is not primarily concerned with how the material universe came into being, but rather how it functions as ordered sacred created space. So this is a way to reorient our approach to Genesis chapter 1.

But I think it’s important in order to properly understand and contextualize what our priestly author was probably imagining or envisioning with this description of the creation of the cosmos.

Convergence Between Genesis 1 and Joseph Smith Cosmology

So with that groundwork laid, let’s spend some time and discuss three areas of convergence between Genesis chapter 1 and Joseph Smith’s cosmology.

Three Key Areas of Convergence

And here they are:

- Creatio ex materia, so creation from pre-existing matter

- The imago Dei concept, the concept that man is made in the image of God

- The presence of a divine plurality in Genesis chapter 1

So we’re going to take them one at a time here.

Creation From Pre-existing Chaos

Let’s start with the first one: creation from pre-existing chaos—let’s say it in those terms.

This is actually one of the clearest points of agreement between Joseph Smith’s teachings and the findings of modern biblical scholarship.

It is the rejection of creation ex nihilo.

Pretty universally, critical biblical scholars recognize—even those who have theological commitments to teachings of creation ex nihilo—they recognize increasingly, if not almost universally, that this is simply not in the Genesis creation text.

The text of Genesis chapter 1 is not concerned with trying to argue that God created:

- all matter,

- every single little atom and

- quark and

- electron,

out of nothing, out of nothingness–whatever that may mean philosophically.

A Description of Functional Ontology

Rather, as Walton says, it is describing a functional ontology: how things work and why they work the way they do and for what purpose they’re working. And it’s not concerned with the generation of matter.

As I have mentioned and I would maintain, the Hebrew syntax of the first three verses of Genesis very strongly suggests that the earth already existed in an unordered primordial state of chaos at the moment when God called forth light in Genesis chapter 3.

This, of course, dovetailing very nicely with Joseph Smith’s description given in the King Follett discourse that God had materials to organize the world—to organize and give function and purpose to.

That seems to be the main intent of Genesis 1.

The Divine Structure of the Cosmos

Genesis 1: we are looking at a cosmos that is a divinely structured reality governed by:

- speech—God’s speech acts that bring the cosmos together—and by

- law–God pronouncing how these things are supposed to work, with each component serving a defined role that God is giving it.

I believe Joseph Smith’s revelations, besides his sermons like the King Follett discourse and other places, align with this. It recovers this ancient perspective in Joseph Smith’s emphasis on eternal matter, divine intelligence, and a cosmos ordered according to divine purpose.

In the Doctrine and Covenants, Joseph Smith calls intelligence the mind of God.

In the Book of Abraham, intelligences are these:

- uncreated

- eternal

- co-eternal entities or beings that

- intrinsically exist along with God, and that

- they are embedded in the cosmos in some meaningful way.

So this, to me, is a dead ringer of a convergence.

Joseph Smith’s emphasis on these aspects of how the cosmos works converges very nicely with our understanding of the purpose and intent behind the priestly creation account, which is not primarily about the creation of matter ex nihilo, but rather the purpose and function of this cosmos that God has ordered and organized out of primordial chaos.

So that’s the first point.

The Image of God

The second point: the image of God, the imago Dei.

Let’s read verses 26 and 27 of chapter 1 of Genesis:

26 Then God said, “Let us make humans in our image, according to our likeness, and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over the cattle and over all the wild animals of the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.”

27 So God created humans in his image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

That’s the rendering from the revised edition of the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible.

Okay. Image and likeness. What do we mean by this?

First, let’s define what these words are. In Hebrew, it’s selem and demut. And we know what these words are because they appear elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible.

The term selem appears about 17 times in the Hebrew Bible, and most of the time it’s referring to basically images—cast or carved images or statues or effigies of some kind. So that’s what we’re talking about with it: we’re talking about a statue or something like that.

And its counterpart, demut, also appears a good 25 times. It denotes a form, a shape, a likeness, a model, something that has a visual resemblance to something else.

It’s most vividly used in the book of Ezekiel when Ezekiel sees the demut of a man in the heaven standing above him, who we understand to be God, according to this vision of Ezekiel.

So those are our very basic definitions of these terms: image and likeness. Man is the statue, the effigy, and the resemblance or the similitude of God. That’s our basic definition of these terms.

What Does It Mean?

There are two aspects to what this might mean.

- The first is that humanity resembles God in some physical way, or they resemble his appearance in some actual way.

- And the second is that humans are distinguished from other creatures and they have an elevated role or position or status in an ontology in creation.

What’s really kind of funny and interesting is the fact that centuries of creedal Christian teachings—the same that brand Latter-day Saints as heretics for believing in an embodied God—centuries of creedal sectarian Christian dogma and orthodoxy, has attempted to absolutely sidestep or just erase the first aspect of this and focus solely on the second aspect of this.

So you will commonly see in both classical and contemporary commentaries on Genesis 1:26 and 27, the imago Dei concept, you will see Christian authors go to great lengths to emphasize number two while downplaying or just ignoring aspect number one.

Creedal vs Modern Interpretations

But that is a mistake, and biblical scholars today recognize that you can’t get around number one. The fact that according to this language, humans actually resemble God’s appearance in some meaningful way. And this isn’t just Stephen Smoot, as some Latter-day Saint hack-apologist, saying this. I can show you across the board, scholars from different faith traditions and backgrounds also recognizing this.

So here’s Richard J. Clifford, a Catholic, a Jesuit:

“The most natural explanation of this language in Genesis 1:26 and 27 is that humans resemble God because they resemble heavenly beings who resemble God.”

We’ll touch on this in just a moment with the idea of a divine plurality.

So, there’s Richard J. Clifford

Here’s Benjamin Sommer, from a Jewish perspective:

“The terms in Genesis 1:26 and 27 pertain specifically to the physical contours of God.”

This is from Sommer’s excellent book on divine anthropomorphism and divine embodiment in the Old Testament.

And then from a Protestant background, David Noel Freedman:

“Certainly the intention of Genesis 1:26 is to say that God and man share a common physical appearance.”

You just can’t get past that from the plain language and meaning of Genesis chapter 1—that humans and God share some kind of a physical appearance or resemblance.

Divine Similitude: the Example of Adam and Seth

And as a matter of fact, it’s staring you right in the face when you turn to Genesis 5:3, where these exact same terms are used in the exact same way to describe the relationship Adam shares with his son Seth, in whose image and likeness he is said to be made.

The logic here is generational.

Divine similitude is passed down as a parent’s image is passed to a child, which suggests not only a relational bond between God and humanity, but also a continuity of nature and form between God and humanity.

And J. Kathleen McDowell, I believe her name is, is the author I cite on this point. Excellent resources there from McDowell on this concept that:

- the image and likeness of God is basically inherited from father to son, and that

- humans share a sense of divine ontology because they share this image and likeness with God, just as Seth is said to share it with Adam, his father.

Broadly speaking, the idea of God being described in explicitly anthropomorphic terms is throughout the Hebrew Bible. He has a face, he has hands, he has feet.

Francesca Stavrakopoulou, in her recent book God: An Anatomy, has explored this at length, going through the various body parts and anthropomorphic dimensions described in the Hebrew Bible pertaining to God and relating that to ancient Near Eastern and Egyptian and Mesopotamian sources that give us comparative analysis and data.

These are not isolated poetic devices. (I know that’s the popular way to interpret this among creedal Christians especially who deny that God has any sort of embodiment.) Rather, it is a foundational biblical concept.

God Mistaken for a Human in Appearance

In fact, in the Hebrew Bible, God appears in such overtly human terms and in human form that at times he is mistaken for being a human being in different encounters that people have with God in some theophoric sense.

So there’s just no getting around it. I’m sorry. Despite what centuries of sectarian teachings will tell you, if you want to be honest and true about what the biblical data says, you have to grapple with this.

Now, there’s more to it here, right? It’s not just about us physically resembling God.

Here’s a quote from a pair of Catholic authors:

A look into Egyptian Mesopotamian culture where the duties of the royal office were often represented by the concept of the king as the image of the creator God, opens up another nuance involved in calling the human being an image of God . . . While in the Egyptian tradition, the king is the ‘image of God’ on the basis of his royal office, in the biblical story of creation this dignity and responsibility belong to all human beings without distinction. The concept is here practically ‘democratized’: not because of extraordinary achievement or responsibilities, but as human beings all are royal images of God.

Joseph Smith’s Teachings on God

So this, of course, converges very nicely with Joseph Smith’s teachings:

“God is a man like one of yourselves, possessing the person, image and very form of man.”

And as he taught in what is now Doctrine and Covenants section 130:

“The Father has a body of flesh and bones, as tangible as man’s; the Son also.”

So there are other ways to explore the meaning and significance of Genesis 1:26–27. I’m fine to have those conversations about how this may relate to humanity’s status or their position.

But if you’re going to be honest, you have to also countenance the fact that this language from the Bible is saying that humans resemble God in some physical anthropomorphic sense, and you can’t really get around that.

Divine Plurality

Our final point will be on the divine plurality in Genesis.

Going back to verses 26 and 27, you’ll notice that we have plural pronouns: “our image,” “our likeness,” and that we have here at the beginning: God said, “Let us make.”

So we have this plural cohortative:

“Let us make humans in our image according to our likeness.”

How do we account for this? How do we describe the plural language in Genesis 1:26 and 27? Let’s run through a couple of the options.

Option One: Pluralis Maiestatis (the Royal “We”)

Option number one, and this is a longheld and traditional explanation, is that this is an example of pluralis maiestatis or ‘the royal we’.

This is a rhetorical device in which monarchs or sovereigns speak in the plural, referring to themselves in order to reflect their majesty or their dignity or their authority.

For instance, God in the Qur’an speaks in this way—Allah speaks like this in the Qur’an. European royalty, you sometimes see them speaking like this.

The problem with this is that this is not attested anywhere else in the Hebrew Bible. Nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible does God speak like this about himself. So this would be the only exceptional case, and this explanation cannot explain why that is so.

You do find in Ezra—this is Aramaic Ezra—one instance where the Persian king refers to himself in the pluralis maiestatis, but it’s not God, and it’s the Persian king speaking Aramaic according to Ezra.

So that explanation doesn’t work because it’s unattested in the Hebrew Bible, and it would simply be special pleading to say this is the one exceptional case when we don’t have it anywhere else.

Option Two: The Trinity

How about maybe this is referring to the Trinity?

This is a popular explanation given by many Christians, that God is just speaking of himself in the plural because he is a Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

Suffice it to say, the problem with this is that we’re reading back into the text a Christian theological idea which only evolved much later.

To put it bluntly, this is eisegesis in its purest form. To insert, to shoehorn, a Trinitarian perspective on an ancient Israelite text written, I believe, sometime before 600 BC, is problematic to say the least.

As a matter of fact—and if Robert Boylan is watching this, he could probably give you all the references you need, so you can go bug Robert Boylan about it. Even other Christian apologists and theologians are moving away from trying to argue for the Trinity out of Genesis 1:26 and 27.

It’s just simply not there. It’s pure eisegesis.

So that explanation doesn’t work.

Option Three: The Divine Council

How about the idea that the plural speech in Genesis reflects God consulting his divine council? What if God is speaking to a divine council? This is my bread and butter—stuff I’ve published on.

What are the problems with this? None. There are no problems with this explanation. And in fact, it provides us with a clear and obvious solution. This is a well-established concept across numerous passages in the Hebrew Bible.

Elsewhere in Genesis, God, when referring to the Tower of Babel, will say, “Come, let us go down and confound their language.” It’ll appear in 1 Kings. It’ll appear in Job, and Psalms, and Isaiah. It’s everywhere. The divine council is ubiquitous.

This is not a controversial, edgy-Latter-day-Saint-apologist ‘take’ here. This is well established in the mainstream of biblical scholarship. The most likely explanation for the plural language in these verses is that God is addressing his divine council, his heavenly court, as he is executing creation.

“God’s Divine Entourage”

And in fact, Richard J. Clifford, who we quoted earlier, has noted no less than seven instances between Genesis chapter 1 and chapter 11—the primordial history—that suggest involvement of what he calls ‘God’s divine entourage’, his divine council.

You can see the references there: the persistent presence of heavenly beings in the creation of heaven and earth, according to Richard J. Clifford, is why we should see this as referring to God’s divine council, a divine plurality.

Angelic Resemblance

And if you merge the two together, as W. Randall Garr has done, you have God saying basically, in effect:

“Angelic gods look like God and they look like men. The god’s shape is intermediate between the two worlds they connect.”

And thus the two terms selem and demut are essentially synonymous and “indicate that human beings resemble God because they resemble angelic godlike beings that resemble God.”

So you can tie these two aspects of the Genesis 1:26 and 27 passage together: the imago Dei concept and the divine plurality. They fit together very nicely in this way.

Convergence with Joseph Smith’s Cosmology

To say the least, this resonates very strongly with Joseph Smith’s cosmology. In his King Follett discourse he spoke of how:

“The head one called the Gods together in grand council . . . . In the beginning, the head of the Gods called a council of the Gods and concocted a scheme to create this world.”

This is picked up also in the book of Abraham, where the Gods organize and counsel together to organize and form the heavens and the earth.

In fact, that language—“the Gods took counsel among themselves”—is used at one point. This is, I believe, very strongly reflecting the same divine plurality that is also preserved in Genesis 1.

So, like I said, I refer you to the full version of my paper to get the full argument, including my citations and my scholarship. But that should give you a flavor for it, at least here with my spoken remarks.

Conclusion

So let’s conclude here real quick.

The opening chapter of Genesis is offering us a rich and multi-layered vision of creation.

I think we do ourselves a disservice when we just focus on, how can we converge or harmonize Genesis with modern science? I understand why a lot of people are concerned about that. It’s a fine question to explore and to have. I think it’s an important one.

But if we sort of pigeonhole ourselves into that, where that’s all we really care about, then we miss the fact that there is so much richness and variety to this text that we can explore from a number of different angles.

Ordering the Cosmos

I maintain, as other scholars have whom I cite, that Genesis 1 is not really speaking of the material origins of the universe.

It is more concerned with ordering the cosmos according to divine will and purpose.

I don’t believe that the text is describing creation ex nihilo, and on that point I think Joseph Smith absolutely scores 100% when he rejected that teaching as well.

I think he’s well vindicated in that regard from what modern biblical scholarship is telling us.

The text assumes the presence of chaotic elements. There’s a formless, wasted earth. There are dark waters. There’s a deep abyss.

And what God is doing as the grand architect of the universe, as it were, He is fashioning that chaotic precreated condition of the cosmos into a structured, functional, and meaningful existence.

That seems to be what Genesis 1 is really speaking to here.

At the Center is the Image of God

At the center of all this is this doctrine of the imago Dei, the image of God: the declaration that humankind is made in the image and likeness of God. Of course, this has historically been interpreted in metaphysical terms.

You see commentators going all the way back to the Middle Ages:

- “Well, we are made in God’s image because we share rationality,” or

- because of our elevated status, or

- because we have the capacity for free will, or

- because we have the ability to be sentient and make moral decisions,

- and so on and so on.

That’s a part of the explanation, but that’s not only the explanation. That isn’t sufficient to describe what’s happening here.

The Appointed Vocation of Humanity

Modern biblical scholarship increasingly recognizes that the priestly author of Genesis understands that humanity has some manner of a shared divine ontology with God by virtue of both our nature that we share with God and by the vocation that God appointed us to.

So, we are meant to rule and steward creation. The human in Genesis 1 is told to subdue and rule the earth. This reflects God’s character himself within the created order.

In other words, humans are “little g” gods and viceroys of God in the created order, who share a measure of his divine nature and ontology and his divine vocation to rule over the earth.

This is the image you get from many scholars today as they look at Genesis chapter 1 and what the priestly author seems to have intended behind this sort of language.

The Council of the Gods

God dwells in a divine council. This is clear in the Hebrew Bible. He is surrounded by angels or gods. Sometimes they’re the ben elohim, the sons of God, with whom he consults in various acts, including in the act of creation.

And although in the priestly account it’s God himself who executes the creation, his divine council is still consulted and still present at the creation.

Humanity shares a relationship with this divine council. That’s why it says, “Let us make man in our image.” That explains this plural language.

So humanity shares some kind of a relationship with this divine council.

And thereby, I would contend, strict ontological monotheism—meaning pure monotheism in the sense of the total and absolute rejection of any ontological existence of any divine beings other than the singular capital-G God—I do not believe is found in the text of Genesis, not at least in the sense that it has philosophically and theologically been constructed to mean by modern monotheists.

How Does This Converge with Joseph Smith?

I believe it converges in all three points.

Joseph Smith emphatically rejected creation ex nihilo.

He emphasized that humans share both an ontological and a vocational resemblance with God and his divine council.

Joseph Smith insisted that there is indeed a divine plurality of gods somewhere out there. But there is a divine plurality that exists in the real ontological realm, not just as figments of imagination.

So I see meaningful areas of convergence between what the prophet teaches and the best of contemporary biblical scholarship.

I want to be clear, though, and clarify. I’m not trying to argue from consensus as the point of, ‘therefore, Joseph Smith is right’ and ‘therefore, our religion is all right and everybody else is wrong’. I’m not trying to appeal to the consensus as a final declarative “this means that we’re right.”

But rather, what I hope that this will do is help people recognize that Joseph Smith’s contributions to these theological discussions and these approaches to the Bible should be properly recognized as having weight to them.

Joseph Smith’s Teachings Bring Greater Perspective

I don’t believe, despite the fact that it’s shocking for many Christians to hear what Joseph Smith taught at the King Follett discourse and elsewhere, I don’t believe that they are just mere curiosities, historical relics, or theological oddities—or at the worst, theological heresies.

I believe that Joseph Smith’s teachings bring a substantive perspective into the broader theological discourse surrounding Genesis chapter 1.

And I think that many scholars today who have looked closely at Genesis chapter 1 converge with him on that—unintentionally, to be sure. I don’t believe that these biblical scholars are intentionally meaning to agree with Joseph Smith or to vindicate him, but I believe they are nevertheless.

In that regard, I suppose we could echo Hugh Nibley when he said that time vindicates the prophets. That is indeed my own position and conclusion I’ve reached here.

And I thank you very much for your time and your attention.

TOPICS

- Genesis 1

- The Creation

- Creation ex nihilio

- Man in the Image of God

- Divine Plurality

- Joseph Smith’s Cosmology

- King Follett Discourse

Abstract

In our day we often struggle with understanding the Old Testament because of cultural, temporal, historical and geographical chasms which loom between us and the Biblical writers. These contribute to our applying modern lenses to an ancient text, which sometimes yields a distorted view.

Instead, if we try to discard some modern lenses and use lenses of the ancient world, we will gain more from the Biblical text. Allowing the text to inform us who Jehovah is, rather than reading what we expect to see in the text, will help us gain more from this.

The Restoration lens is crucial in this effort. Further, using an ancient perspective on symbols, family, and history help. Making sure we see the whole picture rather than cutting the story short is also crucial.

Finally, using a covenant lens, and learning to recognize covenant phrases in the scriptures helps us make much more sense of the Old Testament and allows us to draw power from it.

Bio

Kerry Muhlestein received his BS from BYU in psychology with a Hebrew minor. He received an MA in ancient Near Eastern studies from BYU and his PhD from UCLA in Egyptology. He taught courses in Hebrew and Religion part time at BYU and the UVSC extension center, as well as in history at Cal Poly Pomona and UCLA. He also taught early-morning seminary and at the Westwood (UCLA) institute of religion. His first full-time appointment was a joint position in religion and history at BYU–Hawaii. He is the director of the BYU Egypt Excavation Project. He was selected by the Princeton Review in 2012 as one of the best 300 professors in the nation (the top .02% of those considered). He was also a visiting fellow at the University of Oxford for the 2016–17 academic year. He has published six books and over fifty-five peer-reviewed articles and has done over eighty academic presentations. He and his wife, Julianne, are the parents of six children, and together they have lived in Jerusalem while Kerry has taught there on multiple occasions. He has served as the chairman of a national committee for the American Research Center in Egypt and serves on their Research Supporting Member Council. He has also served on a committee for the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities and currently serves on their board of trustees and as a vice president of the organization. He is the co-chair for the Egyptian Archaeology Session of the American Schools of Oriental Research. He is also a senior fellow of the William F. Albright Institute for Archaeological Research. He is involved with the International Association of Egyptologists, and has worked with Educational Testing Services on their AP world history exam.