FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

FAIR Answers—back to home page

| Book of Mormon Geography | A FAIR Analysis of: Difficult Questions for Mormons, a work by author: The Interactive Bible

|

Book of Mormon Races |

| Claim Evaluation |

| Difficult Questions for Mormons |

|

Response to claim: "Why are Greek names such as Lachoneus, Timothy, Jonas, and Alpha & Omega in a book that should have absolutely no Greek influence?"

We have answered this criticism at this link.

Hugh Nibley:

The occurrence of the names Timothy and Lachoneus in the Book of Mormon is strictly in order, however odd it may seem at first glance. Since the fourteenth century B.C. at latest, Syria and Palestine had been in constant contact with the Aegean world; and since the middle of the seventh century, Greek mercenaries and merchants closely bound to Egyptian interest (the best Egyptian mercenaries were Greeks) swarmed throughout the Near East.23 Lehi's people, even apart from their mercantile activities, could not have avoided considerable contact with these people in Egypt and especially in Sidon, which Greek poets even in that day were celebrating as the great world center of trade. It is interesting to note in passing that Timothy is an Ionian name, since the Greeks in Palestine were Ionians (hence the Hebrew name for Greeks: "Sons of Javanim"), and—since "Lachoneus" means "a Laconian"—that the oldest Greek traders were Laconians, who had colonies in Cyprus (Book of Mormon Akish) and of course traded with Palestine.24[1]

Response to claim: "Why aren't there other examples of "Reformed Egyptian" in Ancient America?"

Moroni makes it clear that "reformed Egyptian" is the name which the Nephites have given to a script based upon Egyptian characters, and modified over the course of a thousand years (See Mormon 9:32). So, it is no surprise that Egyptians or Jews have no script called "reformed Egyptian," as this was a Nephite term.

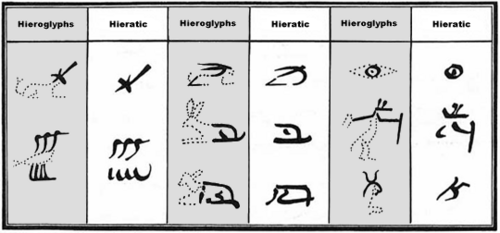

There are, however, several variant Egyptian scripts which are "reformed" or altered from their earlier form. Hugh Nibley and others have pointed out that the change from Egyptian hieroglyphics, to hieratic, to demotic is a good description of Egyptian being "reformed." By 600 BC, hieratic was used primarily for religious texts, while demotic was used for daily use.off-site

One can see how hieroglyphics developed into the more stylized hieratic, and this process continued with the demotic:

What could be a better term for this than an Egyptian script that has been "reformed"?

More recent research provides further corroboration:

The fourth presentation at BYU’s Willes Center for Book of Mormon Studies conference on 31 August 2012 was on “Writing in 7th Century BC Levant,” by Stefan Wimmer of the University of Munich. It was entitled “Palestinian Hieratic.” He examined an interesting phenomena in Hebrew inscriptions, the use of Egyptian hieratic (cursive hieroglyphic) signs.

Basically Hebrew scribes used Egyptian signs for various numerals, weights and measures. The changes in the form of these signs parallel similar chronological changes in the form of Egyptian hieratic characters, which indicates continued contact of some sort between Egyptian and Hebrew scribes, probably over several centuries. (If there had been a single scribal transmission with no ongoing contact, the changes in the Hebrew forms of hieratic signs would not parallel contemporary changes in Egyptian hieratic forms.) No other Semitic language used Egyptian hieratic signs except Hebrew (with one possible Moabite example.)

There are a couple of hundred examples of such texts, the majority dating from the late seventh century, and geographically mainly from Jerusalem southward. The phenomena ends after the Babylonian captivity. (In other words, Palestinian hieratic is most common in precisely the time and location of Lehi and Nephi, and only exists in Hebrew.)[2]

Additionally,

Documents from the kingdoms of both Israel and Judah, but not the neighboring kingdoms, of the eighth and seventh centuries contain Egyptian hieratic signs (cursive hieroglyphics) and numerals that had ceased to be used in Egypt after the tenth century (Philip J. King and Lawrence E. Stager, Life in Biblical Israel (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), 311.)

German Egyptologist Stefan Wimmer calls this script "palestinian Hieratic." See Stefan Wimmer, Palästinisches Hieratisch: Die Zahl- und Sonderzeichen in der althebräischen Schrift, Ägypten und Altes Testament 75 (Germany: Harrassowitz Wiesbaden, 2008).

William Hamblin provides additional example of such reformation of Egyptian, including:

Given that Moroni says the Nephites then modified the scripts further, "reformed Egyptian" is an elegant description of both the Old World phenomenon, and what Moroni says happened among the Nephites.

Response to claim: "Why doesn't a linguistical relationship exist between any native American language and ancient Egyptian or Hebrew?"

The Book of Mormon text suggests that Lehite language had a relatively minor impact on the speech of the Americas. It may be that Old World languages formed a type of "elite" language, used only by a few for religious purposes.

If, however, one is persuaded that the Book of Mormon text implies that some Hebrew links should still exist, preliminary linguistic data suggest that there are some intriguing links.

For example, Dr. Brian Stubbs argues for numerous parallels between Hebrew and Uto-Aztecan. As a professional linguist, Dr. Stubbs avoids the pitfalls of amateurs who simply point at similar words between two different languages. As he points out,

Any two languages can have a few similar words by pure chance. What is called the comparative method is the linguist's tool for eliminating chance similarities and determining with confidence whether two languages are historically—that is, genetically—related. This method consists of testing for three criteria. First, consistent sound correspondences must be established, for linguists have found that sounds change in consistent patterns in related languages; for example, German tag and English day are cognates (related words), as well as German tür and English door. So one rule about sound change in this case is that German initial t corresponds to English initial d. Some general rules of sound change that occur in family after family help the linguist feel more confident about reconstructing original forms from the descendant words or cognates, although a certain amount of guesswork is always involved.

Second, related languages show parallels in specific structures of grammar and morphology, that is, in rules that govern sentence and word formation.

Third, a sizable lexicon (vocabulary list) should demonstrate these sound correspondences and grammatical parallels.

When consistent parallels of these sorts are extensively demonstrated, we can be confident that there was a sister-sister connection between the two tongues at some earlier time.[4]

A few of Stubbs' many examples are:

| Hebrew/Semitic | Uto-Aztecan |

|---|---|

| kilyah/kolyah 'kidney' | kali 'kidney' |

| baraq 'lightning' | berok (derived from *pïrok) 'lightning' |

| sekem/sikm- 'shoulder' | sikum/sïka 'shoulder' |

| mayim/meem 'water' | meme-t 'ocean' |

Rhodes Scholar Dr. Roger Westcott, non-LDS Professor Emeritus of Anthropology and Linguistics at Drew University, has made positive comments about Dr. Stubbs' research:

Perhaps the most surprising of all Eurasian-American linguistic connections, at least in geographic terms, is that proposed by Brian Stubbs: a strong link between the Uto-Aztecan and Afro-Asiatic (or Hamito-Semitic) languages. The Uto-Aztecan languages are, or have been, spoken in western North America from Idaho to El Salvador. One would expect that, if Semites or their linguistic kinsmen from northern Africa were to reach the New World by water, their route would be trans-Atlantic. Indeed, what graphonomic evidence there is indicates exactly that: Canaanite inscriptions are found in Georgia and Tennessee as well as in Brazil; and Mediterranean coins, some Hebrew and Moroccan Arabic, are found in Kentucky as well as Venezuela [citing Cyrus Gordon].

But we must follow the evidence wherever it leads. And lexically, at least, it points to the Pacific rather than the Atlantic coast. Stubbs finds Semitic and (more rarely) Egyptian vocabulary in about 20 of 25 extant Uto-Aztecan languages. Of the word-bases in these vernaculars, he finds about 40 percent to be derivable from nearly 500 triliteral Semitic stems. Despite this striking proportion, however, he does not regard Uto-Aztecan as a branch of Semitic or Afro-Asiatic. Indeed, he treats Uto-Aztecan Semitisms as borrowings. But, because these borrowings are at once so numerous and so well "nativized," he prefers to regard them as an example of linguistic creolization - that is, of massive lexical adaptation of one language group to another. (By way of analogy, . . . historical linguists regard the heavy importation of French vocabulary into Middle English as a process of creolization.)....

Lest skeptics should attribute these correspondences to coincidence, however, Stubbs takes care to note that there are systematic sound-shifts, analogous to those covered in Indo-European by Grimm's Law, which recur consistently in loans from Afro-Asiatic to Uto-Aztecan. One of these is the unvoicing of voiced stops in the more southerly receiving languages. Another is the velarization of voiced labial stops and glides in the same languages.[5]

While the conclusions remain tentative, some of the details of this on-going research look promising. Certainly, nothing in the linguistic evidence provides plausible arguments against the Book of Mormon narrative.

The Book of Mormon text suggests that Lehite language had a relatively minor impact on the speech of the Americas. It may be that Old World languages formed a type of "elite" language, used only by a few for religious purposes.

If, however, one is persuaded that the Book of Mormon text implies that some Hebrew links should still exist, preliminary linguistic data suggest that there are some intriguing links.

For example, Dr. Brian Stubbs argues for numerous parallels between Hebrew and Uto-Aztecan. As a professional linguist, Dr. Stubbs avoids the pitfalls of amateurs who simply point at similar words between two different languages. As he points out,

Any two languages can have a few similar words by pure chance. What is called the comparative method is the linguist's tool for eliminating chance similarities and determining with confidence whether two languages are historically—that is, genetically—related. This method consists of testing for three criteria. First, consistent sound correspondences must be established, for linguists have found that sounds change in consistent patterns in related languages; for example, German tag and English day are cognates (related words), as well as German tür and English door. So one rule about sound change in this case is that German initial t corresponds to English initial d. Some general rules of sound change that occur in family after family help the linguist feel more confident about reconstructing original forms from the descendant words or cognates, although a certain amount of guesswork is always involved.

Second, related languages show parallels in specific structures of grammar and morphology, that is, in rules that govern sentence and word formation.

Third, a sizable lexicon (vocabulary list) should demonstrate these sound correspondences and grammatical parallels.

When consistent parallels of these sorts are extensively demonstrated, we can be confident that there was a sister-sister connection between the two tongues at some earlier time.[6]

A few of Stubbs' many examples are:

| Hebrew/Semitic | Uto-Aztecan |

|---|---|

| kilyah/kolyah 'kidney' | kali 'kidney' |

| baraq 'lightning' | berok (derived from *pïrok) 'lightning' |

| sekem/sikm- 'shoulder' | sikum/sïka 'shoulder' |

| mayim/meem 'water' | meme-t 'ocean' |

Rhodes Scholar Dr. Roger Westcott, non-LDS Professor Emeritus of Anthropology and Linguistics at Drew University, has made positive comments about Dr. Stubbs' research:

Perhaps the most surprising of all Eurasian-American linguistic connections, at least in geographic terms, is that proposed by Brian Stubbs: a strong link between the Uto-Aztecan and Afro-Asiatic (or Hamito-Semitic) languages. The Uto-Aztecan languages are, or have been, spoken in western North America from Idaho to El Salvador. One would expect that, if Semites or their linguistic kinsmen from northern Africa were to reach the New World by water, their route would be trans-Atlantic. Indeed, what graphonomic evidence there is indicates exactly that: Canaanite inscriptions are found in Georgia and Tennessee as well as in Brazil; and Mediterranean coins, some Hebrew and Moroccan Arabic, are found in Kentucky as well as Venezuela [citing Cyrus Gordon].

But we must follow the evidence wherever it leads. And lexically, at least, it points to the Pacific rather than the Atlantic coast. Stubbs finds Semitic and (more rarely) Egyptian vocabulary in about 20 of 25 extant Uto-Aztecan languages. Of the word-bases in these vernaculars, he finds about 40 percent to be derivable from nearly 500 triliteral Semitic stems. Despite this striking proportion, however, he does not regard Uto-Aztecan as a branch of Semitic or Afro-Asiatic. Indeed, he treats Uto-Aztecan Semitisms as borrowings. But, because these borrowings are at once so numerous and so well "nativized," he prefers to regard them as an example of linguistic creolization - that is, of massive lexical adaptation of one language group to another. (By way of analogy, . . . historical linguists regard the heavy importation of French vocabulary into Middle English as a process of creolization.)....

Lest skeptics should attribute these correspondences to coincidence, however, Stubbs takes care to note that there are systematic sound-shifts, analogous to those covered in Indo-European by Grimm's Law, which recur consistently in loans from Afro-Asiatic to Uto-Aztecan. One of these is the unvoicing of voiced stops in the more southerly receiving languages. Another is the velarization of voiced labial stops and glides in the same languages.[7]

While the conclusions remain tentative, some of the details of this on-going research look promising. Certainly, nothing in the linguistic evidence provides plausible arguments against the Book of Mormon narrative.

Response to claim: "How did the Book of Mormon language evolve so rapidly into non-related Indian languages? Indo-European is much older than the Book of Mormon time period, yet vestiges of Indo-European exist through all of Europe and parts of Asia."

It is important to note that we may never find traces of Hebrew language among American languages for the simple fact that the Lehite’s mother tongue all-but-disappeared shortly after their arrival in the New World. When Moroni writes about reformed Egyptian, he also explains that the “Hebrew hath been altered by us also” (Mormon 9꞉33).

Like other ancient civilizations (such as Egypt) most New World inhabitants would not have been literate. While ancient Americans had a sophisticated writing system, it is likely that knowledge of this system was limited to the civic officials or the priestly class. In the Book of Mormon we infer that training and devotion were necessary to competently master their difficult writing system. King Benjamin, for example, “caused that [his princely sons] should be taught all the languages of his fathers, that thereby they might become men of understanding” (Mosiah 1꞉3). Moroni, who had mastered the art himself, lamented that the Lord had not made the Nephites “mighty in writing” (Ether 12꞉23).

The most likely scenario is that the Lehites—who were a small incursion into a larger existing native populace—embraced the habits, culture, and language of their neighbors within a very short period after their arrival in the New World. This is what we generally find when a small group melds with a larger group. The smaller group usually takes on the traits of the larger (or, at least, the more powerful) group—not the other way around. It is not unusual, however, for at least some of the characteristics of the smaller group to show up in the larger group’s culture. Typically, however, the smaller group becomes part of the larger group with which they merge. Thus, the Lehites would have become Mesoamericans. We see, therefore, the necessity to teach the Old World language to a few elite in order to preserve, not only the traditions, but also to maintain a continuation of scribes who could read the writings of past generations.

Even with such instruction, however, the script was most likely an altered form of Egyptian—perhaps adapted to Mesoamerican scripts—and altered according to their language. This suggests that ideas and motifs that originated in the Old World were adapted to a script that could be conveyed with New World motifs, or at least New World glyphs. Under such conditions, would there be any reason to expect that we’d find “Hebrew” among the Native Americans?

Response to claim: "Why are only four main types of Mesoamerican writing systems known (and none in pre-Columbus North America): (Aztec, Mixtec, Zapotec, and Maya)?"

Response to claim: "Why can't the Anthon transcript (which contains copies of the supposed Reformed Egyptian characters) be identified with any forms of Egyptian? The only three Egyptologists that have looked at it say it does not contain any Egyptian (Ferguson Collection, BYU)"

Response to claim: "If the Book of Mormon took place outside of Mesoamerica (like in New York where the Hill Cumorah supposedly is), why are written languages of ancient America only found in Mesoamerica?"

Response to claim: "Why haven't any of the Book of Mormon proper names such as Nephi, Laman, Zarahemla, etc. been found in all of the many writings that have been found in Mesoamerica?"

Plus, there are some interesting aspects of the naming in the Book of Mormon that the names had narrative purposes, and didn't actually reflect personal names in many cases. Finally, different languages and phonetics render things differently. Mark Wright and Kerry Hull played around with a Maya representation of a purported "Greek" name in the Book of Mormon and found that in Maya it might be "flaming mosquito"--which doesn't sound like it should be a thing--except there are artistic representations of flaming mosquitoes.

Notes

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now