FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

| Claims made in "Chapter 3: From Profit to Prophet" | A FAIR Analysis of: One Nation Under Gods A work by author: Richard Abanes

|

Claims made in "Chapter 5: People of Zion" |

—One Nation Under Gods, p. 60.

Author's source(s)

Response

Does the Book of Mormon contain parallels to Ethan Smith's View of the Hebrews?

Author's sources:

- Ethan Smith, View of the Hebrews, 172.

- Persuitte, 107, 122.

The View of the Hebrews theory is yet another attempt to fit a secular origin to the Book of Mormon. Many of the criticisms proposed are based upon B. H. Roberts' list of parallels, which only had validity if one applied a hemispheric geography model to the Book of Mormon. There are a significant number of differences between the two books, which are easily discovered upon reading Ethan Smith's work. Many points that Ethan Smith thought were important are not mentioned at all in the Book of Mormon, and many of the "parallels" are no longer valid based upon current scholarship.[2]

Advocates of the Ethan Smith theory must also explain why Joseph, the ostensible forger, had the chutzpah to point out the source of his forgery. They must also explain why, if Joseph found this evidence so compelling, he did not exploit it for use in the Book of Mormon text itself, since the Book of Mormon contains no reference to the many "unparallels" that Ethan assured his readers virtually guaranteed a Hebrew connection to the Amerindians.

Some parallels do exist between the two books. For example, View of the Hebrews postulates the existence of a civilized and a barbarous nation who were constantly at war with one another, with the civilized society eventually being destroyed by their uncivilized brethren. This has obvious similarities to the story of the Nephites and the Lamanites in the Book of Mormon.

Many of the "parallels" that are discussed are not actually parallels at all once they are fully examined:

| Both speak of... | View of the Hebrews | Book of Mormon |

|---|---|---|

| ...the destruction of Jerusalem... | ...by the Romans in A.D. 70. | ...by the Babylonians in 586 B.C. |

| ...Israelites coming to the American continent... | ...via dry land across the Bering Strait. | ...via the ocean on board a ship. |

| ...colonists spread out to fill the entire land... | ...from the North to the South. | ...from the South to the North. |

| ...a great lawgiver (whom some assume to be associated with the legend of Quetzalcoatl)... | ...who is identified as Moses. | ...who is identified as Jesus Christ. |

| ...an ancient book that was preserved for a long time and then buried... | ...because they had lost the knowledge of reading it and it would be of no further use to them. [3] | ...in order to preserve the writings of prophets for future generations. |

| ...a buried book taken from the earth... | ...in the form of four, dark yellow, folded leaves of old parchment.[4] | ...in the form of a set of gold metal plates. |

| ...the Egyptian language, since | ...an Egyptian influence is present in hieroglyphic paintings made by native Americans.[5] | ...a reformed Egyptian was used to record a sacred history. |

Some "parallels" between the Book of Mormon and View of the Hebrews are actually parallels with the Bible as well:

| The Book of Mormon | View of the Hebrews | The King James Bible |

|---|---|---|

| The Book of Mormon tells the story of inspired seers and prophets. | View of the Hebrews talks of Indian traditions that state that their fathers were able to foretell the future and control nature. | The Bible tells the story of inspired seers and prophets. |

| The Book of Mormon was translated by means of the Nephite interpreters, which consisted of two stones fastened to a breastplate, and later by means of a seer stone, both of which were later referred to by the name "Urim and Thummim" three years after the translation was completed. | View of the Hebrews describes a breastplate with two white buttons fastened to it as resembling the Urim and Thummim. | The Bible describes the Urim and Thummim as being fastened to a breastplate (Exodus 28:30). |

This highlights the fact that general parallels are likely to be found between works that treat the same types of subjects, such as ancient history. In what ancient conflict did one side not see themselves as representing light and civilization against the dark barbarism of their enemies?

Critics generally ignore the presence of many "unparallels"—these are elements of Ethan Smith's book which would have provided a rich source of material for Joseph to use in order to persuade his contemporaries that the Book of Mormon was an ancient history of the American Indians, and that they were descended from Israel. Yet, the Book of Mormon consistently ignores such supposed "bulls-eyes," which is good news for proponents of the Book of Mormon's authenticity, since virtually all of Ethan's "evidences" have been judged to be false or misleading.

The lack of such "unparallels" is bad news, however, for anyone wanting to claim that Joseph got his inspiration or information from Ethan Smith.

If the View of the Hebrews served as the basis for the Book of Mormon, one would think that the Bible scriptures used by Ethan Smith would be mined by Joseph Smith for the Book of Mormon. Yet, this is not the case.

No contemporary critic of Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon pointed out the supposedly "obvious" connection to the View of the Hebrews and the Book of Mormon. It is only with the failure of the Spaulding theory that critics began seeking a new naturalistic explanation for Joseph's production of a 500+ book of scripture. As Stephen Ricks notes:

The names "Moroni" and "Cumorah" could have been taken from the "Comoros" Islands off the coast of Africa.

Author's sources:

- Book of Mormon (1830), 529-530 Mormon 6꞉2-11

Summary: Critics of the Book of Mormon claim that Joseph Smith could have acquired the names “Moroni” and “Cumorah” from either maps he could have had access to as a youth, stories that he may have read associated with Captain William Kidd, or local Palmyra whalers that told stories of their journeys to places where Captain Kidd is also known to have operated.

The argument typically starts with the Captain Kidd stories. Joseph is supposed to have known about stories regarding Captain Kidd and either directly cribbed the names "Moroni" and "Cumorah" (or names close to those two) from the stories or, inspired by Kidd’s and/or other pirates' exploits on the four islands of the Comoros Archipelago (which is almost sandwiched between Mozambique and Madagascar in the Mozambique Channel), gone to maps to learn more about the area and found names on those maps that he could use for the supposedly fictitious creation of the Book of Mormon. On the maps, he would have found that the capital city of one of the islands in the archipelago is Moroni. On one of the islands in the Comoros, Anjouan (also sometimes called "Joanna" historically), there is a port city named "Meroni" (sometimes spelled "Merone").

Alternatively, as mentioned, American whalers could have sailed in the Comoros and talked about their travels in settings where Joseph could have heard them.

To reiterate, there are two places that Joseph Smith could have gotten the name “Moroni” from and three places that he could have gotten “Cumorah” from, according to these critics.

For Moroni:

For Cumorah:

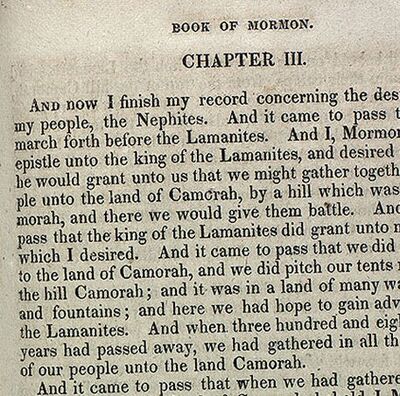

For this last potential source ("Camora"), critics note that, in the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon, Cumorah is always spelled "Camorah", suggesting that Joseph and/or Oliver merely added an h to the end of the name "Camora", placed it in the Book of Mormon, and then respelled it later on to perhaps cover their tracks more.

When weighing the probability that this theory is true, your mileage varies a little depending on what you assume regarding various questions, such as:

At nearly every step here, you're making dubious (and, in some of the cases of the critics above, false) claims/assumptions based on tenuous (and, in some of the instances of the critics above, entirely non-existent) strands of evidence.

As your evidence, you have the name "Comaro" once in General History; you have 41 mentions of other islands besides Comore in the Comoros in relation to different pirates, 12 of which are to Joanna; you have a handful of mostly late and mostly hostile (with the obvious exception of Orrin Porter Rockwell) statements that say that Joseph Smith sought for Captain Kidd's treasure and one contemporary newspaper account that says that citizens of Palmyra looked for that treasure; you have three late, hostile sources, one relying on the accuracy of the other, stating that Joseph Smith had a copy of an autobiography of or "novels" about Captain Kidd; you have five maps, all of which are detail maps of one island (out of two separate islands) in the Comoros, with names sometimes more similar and sometimes less similar to "Moroni" and "Cumorah", and two of which are in French; and you have some other potential sources documented by Carmack.

You're likely committing an appeal to probability fallacy and a texas sharpshooter fallacy to claim that the theory works and establish your case.

As far as the author's beliefs, the evidence really only carries you with certainty as far as Joseph Smith knowing about Captain Kidd and the treasure he buried in New York and looking for it. He also likely (but not certainly) read about Captain Kidd in some sources available to him. Past that, little can be certain. Little wonder Carmack says that whether Joseph Smith was aware of the Comoros before 1830 is difficult to determine conclusively. Any similarity, closer or further, between the Comoros Islands and the Book of Mormon is most likely coincidental and specious.

Both the main body of text and the footnotes of this article contain valuable information related to these arguments, and we encourage readers to review both.

Some background on Captain Kidd will be helpful as we continue with this article. This history lesson comes primarily from "MaryAnn", a blogger at the blog Wheat and Tares,[7] with some modifications by the author of this article:

Captain Kidd was Scottish-born but lived in New York. He was a successful privateer who typically worked the West Indies. An upstanding British citizen, he got hired in 1696 to go after pirates in the East Indies (and French merchants, because England and France weren’t on good terms). He and his crew were to be paid from the spoil they got, with a portion going back to his sponsors. Hiring these privateers was a way for the British government to supplement its navy and look after its interests on the high seas, while maintaining plausible deniability if the privateers ever did anything wrong.

With a brand-spankin' new ship (called the Adventure Galley) and a bunch of experienced New York seamen, Kidd made his way to the East Indies. It took a year, but Kidd and his crew finally reached Madagascar, a known pirate haven, in January 1697. Unfortunately, he couldn’t find any pirates. Whoops. After a month, he headed over to Johanna, the most popular island in the Comoro archipelago. He spent March and April in the Comoros, bouncing back and forth between the islands of Johanna and Mohilla. On Mohilla, he lost fifty men to sickness. Luckily, he got more men on the island of Johanna and was finally able to borrow enough money to repair his debilitated ship. He left the Comoro Islands an honest man, a little financially desperate, but an honest man. It wasn’t until a few months later that things started to get a little fishy.

Kidd traveled about a thousand miles north to Bab-el-Mandeb at the mouth of the Red Sea and unsuccessfully attacked a fleet in August 1697. So he decided to try his luck on the Malabar Coast, along the Western coast of India, over 3,000 miles away from the Comoros Islands. His crew grew antsy, and they attempted mutiny when Kidd refused to attack a Dutch ship. The leader of the mutiny, William Moore, later died when Kidd threw a bucket at him (this death became important later). Ultimately, he only ever took two French ships while sailing down India’s western coast, but the second, the Quedagh Merchant, was laden with valuables. Unfortunately, England was on better terms with France, so the capture of the ships was viewed as scandalous (turns out the latter boat was captained by an Englishman – double whoops). Once word of these activities reached London in late 1698, William Kidd was declared a pirate, and orders were given to apprehend him.

Captain Kidd, unaware of his infamy, sailed the Quedagh Merchant to the Caribbean (after a brief, uncomfortable encounter with a real pirate at Madagascar). Upon his arrival in the West Indies, he used part of his treasure to purchase a new ship and left the Quedagh Merchant, now a liability, behind. Later, Kidd’s crew pillaged the ship and burned it. The remains of the Quedagh Merchant were rediscovered in 2007, just off the coast of Catalina Island.

Kidd sailed up to New York to appeal to higher-ups and hid a bunch of his treasure on Gardiners Island (fueling rumors that he or his associates were also burying treasure in other areas of the Northeastern United States). He never buried treasure in the Comoros. He was apprehended and taken to England. Found guilty of piracy and the murder of William Moore, Kidd was executed in 1701 with two associates, and his body was hanged for three years over the River Thames to discourage would-be pirates.

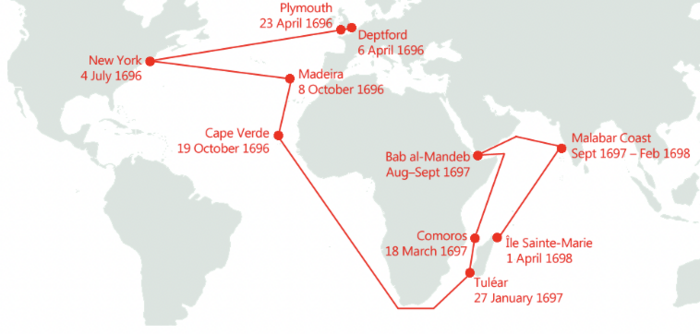

The following map is from Wikipedia and gives an overview of the locations and dates of arrival for Captain Kidd's journeys:

The Comoro Islands were indeed heavily utilized by pirates, but typically not for burying treasure. They were a part of the Pirate Round, a “sailing route followed by certain mainly English pirates, during the late 17th century and early 18th century. The course led from the western Atlantic, parallel to the Cape Route around the southern tip of Africa, stopping at Madagascar, then on to targets such as the coast of Yemen and India. The Pirate Round was briefly used again during the early 1720s. Pirates who followed the route are sometimes referred to as Roundsmen. The Pirate Round was largely co-extensive with the routes of the East India Company ships of Britain and other nations. The Pirate Round started from a variety of Atlantic ports, including Bermuda, Nassau, New York City, and A Coruña, depending on where the pirate crew initially assembled. The course then lay roughly south by southeast along the coast of Africa, frequently by way of the Madeira Islands. The pirates would then double the Cape of Good Hope, and sail through the Mozambique Channel to northern Madagascar. Pirates would frequently careen and refit their ships on Madagascar and take on fresh provisions before proceeding onward toward their targets further north. Particularly important pirate bases on Madagascar included the island of St. Mary's (often called by its French name, Île Sainte-Marie) and Ranter Bay (now called Antongil Bay), both on the northeastern side of the island."[8] The Comoros were sometimes used as a stopping point to prepare for the rest of the journey to India, Yemen, or other destinations.

We'll start with stories about Captain Kidd, as contained in books, since critics typically cite those as the most likely source for Joseph's plagiarism.

References to Joseph Smith's interest in the adventures of Captain Kidd come from some of his contemporaries, years after the publication of the Book of Mormon. For example, Pomeroy Tucker in his 1867 book Origin, rise, and progress of Mormonism (37 years after the Book of Mormon was published and 23 years after Joseph's death), portrayed the Smith family as an "illiterate, whiskey-drinking, shiftless, irreligious race of people" and Joseph Smith, Jr. as the "laziest and most worthless of the generation."[11]:16 Tucker offers this "insight" regarding the young Joseph Smith and Captain Kidd:

Joseph, moreover, as he grew in years, had learned to read comprehensively, in which qualification he was far in advance of his elder brother, and even of his father; and this talent was assiduously devoted, as he quitted or modified his idle habits, to the perusal of works of fiction and records of criminality, such for instance as would be classed with the "dime novels" of the present day [Noted here is that the first “dime novel” did not appear until 1860. See Wikipedia article "Dime novel" off-site]. The stories of Stephen Burroughs and Captain Kidd, and the like, presented the highest charms for his expanding mental perceptions. As he further advanced in reading and knowledge, he assumed a spiritual or religious turn of mind, and frequently perused the Bible...[11]:17

It's important to note that Pomeroy Tucker did not connect the Captain Kidd stories to the Book of Mormon and attempt to argue that Joseph Smith plagiarized the former.

We would dispute Tucker's late portrayal of the Smith family as lazy and shiftless, as would the contemporaneous historical records (which are more reliable than late, hostile testimony obviously designed to discredit the Smiths).[12] We'd also dispute his characterization of Joseph as an avid reader. Emma Smith, Joseph's wife, remembered that during the translation of the Book of Mormon, he didn't know that Jerusalem had walls around it.[13] She also said "Joseph Smith...could neither write nor dictate a coherent and well-worded letter; let alone dictating a book like the Book of Mormon."[14] Lucy Smith, Joseph's mother, reminisced that Joseph was less inclined to the perusal of books and more to deep meditation.[15]

| Main articles: | Joseph and the family's early reputation |

| Contemporary witnesses regarded the Smiths as trustworthy and hard-working | |

| Lazy Smiths? | |

| Joseph's early work as a farmhand |

However, knowing that Joseph was involved in treasure seeking, and that the great motivation for much of the treasure seeking being performed at the time was the result of a common belief that Captain Kidd had hidden treasure somewhere on the east coast of the United States, it is not unreasonable to assume that Joseph was familiar with the stories.

The Wayne Sentinel reported in 1825:

We are sorry to observe, even in this enlightened age, so prevalent a disposition to credit the accounts of the marvellous. Even the frightful stories of money being hid under the surface of the earth, and enchanted by the Devil or Robert Kidd [Captain Kidd], are received by many of our respectable fellow citizens as truths.[16]

Mostly hostile and, in most cases, clearly late sources reminisced that, in his early years, Joseph Smith "had spent his time for several years in telling fortunes and digging for hidden treasures, and especially for pots and iron chests of money, supposed to have been buried by Captain Kidd."[17]:3:154 Others insinuated that Joseph Smith "studied piracy while digging for the money [his] Father pretended old Bob Kidd <had> buried."[17]:1:597[18] Another stated that "[h]e had for a library a copy of the 'Arabian Nights,' stories of Captain Kidd, and a few novels."[17]:3:130 Another late, hostile source, "evidently relying on the published accounts of...Pomeroy Tucker",[17]:3:146 reported that Joseph had in his possession "'The Life of Stephen Burroughs,' the clerical scoundrel, and the autobiography of Capt. Kidd, the pirate" and that Kidd was Joseph's Smith's "hero."[17]:3:148 The "autobiography" in Joseph Smith's possession is not specified. Still, one author argued persuasively that the most likely source is Charles Johnson's General History of the Pyrates.[19]:pp. 109–110 One late, hostile source claims that Joseph Smith "saw Captain Kidd sailing on the Susquehanna River during a freshet, and that he buried two pots of gold and silver. He claimed he saw writing cut on the rocks in an unknown language telling where Kidd buried it, and he translated it through his peep-stone." That same source reports that Joseph "dug...for Kidd’s money, on the west bank of the Susquehanna, half a mile from the river, and three miles from his salt wells."[17]:4:182–84. James Harrison Kennedy, a non-Latter-day Saint and then-editor of the Magazine of Western History, wrote in an account of Church history published in 1888 that Joseph Smith Sr. was reportedly "at times" engaged in the hunt for Captain Kidd's treasure.[20]:p. 8 Kennedy also wrote that Joseph Smith had told him that the autobiography of Captain Kidd "made a deep impression upon him."[20]:p. 13 Kennedy cites no source for this statement, however. These sources may very well contain fabrications and exaggerations. They are certainly designed to convince others that Joseph Smith Sr. and Jr. Smith are/were mendacious swindlers as well as fanciful, superstitious lunatics.

"Orrin Porter Rockwell, Joseph's neighbor in Manchester, New York, told Elizabeth W. Kane in the early 1870s that '[n]ot only was there religious excitement, but the phantom treasure of Captain Kidd were sought for far and near, and even in places like Cumorah'."[21]:p. 185n53

Critics have more recently attempted to link the stories to Joseph, as Captain William Kidd is known to have visited the Comoros Islands during his life.

The first to propose the Comoros/Moroni/Captain Kidd connection seems to be Fred Buchanan, then an associate professor in the Department of Educational Studies at the University of Utah, in the June 1989 issue of Sunstone Magazine.[22] Buchanan spoke about a "rendezvous at Comoro and Moroni" that Kidd had. Yet Kidd never set foot on Comore nor Moroni.

Years later, in a 2003 article, critic Ronald V. Huggins asserted that Captain Kidd was "hanged for crimes allegedly committed in the vicinity of Moroni on Grand Comoro."[23] Except he wasn't. Similarly, critic Jeremy T. Runnells claimed that Kidd "was...arrested for capturing a treasure ship called the 'Quedagh Merchant' in the Indian Ocean near the Comoros islands."[24] Except he wasn't even close to the Comoros. Kidd was charged with crimes/declared a pirate only after he seized the ship Quedagh Merchant on January 30, 1698. Recall that the seizing of the ship occurred along the western coast of India—over 3,000 miles away from the Comoros! Kidd and his crew spotted the ship about 25 leagues from Kochi. Kidd was hanged in 1701 in London for stealing the Quedagh Merchant and for murdering his ship's gunner, William Moore, during a mutiny which occurred around the same time as the seizure of the Quedagh Merchant. None of these actions was related to the city of Moroni or the Comoros generally. The association of these events with "Moroni on Grand Comoro" is an unsupported assertion by Huggins, and these specific names have nothing to do with Kidd's execution. This seems to be a stretching attempt by Huggins to tie Kidd's execution with Joseph Smith and Mormonism more closely. Huggins' other abuses of historical sources and problematic conclusions have been thoroughly exposed by historians Mark Ashurst-McGee and Larry E. Morris.[25] We've reviewed some of Huggins' claims here on the FAIR wiki.

Eleven years after Huggins, ex-Mormon critic Grant H. Palmer asserted in a 2014 article that Joseph Smith acquired the names "Cumorah" and "Moroni" by reading stories of Captain Kidd in his youth. Palmer concludes that it is "reasonable to assert that Joseph Smith's hill in the 'land of Camorah' [Comorah/Cumorah], 'city of Moroni,' and 'land of Moroni/Meroni,' is connected with the ilhas [islands] de Comoro/'Camora,' the Moroni/Meroni settlements, and these pirate adventures."[26] Similarly, critic Jeremy T. Runnells in the 2017 edition of his CES Letter claims that "'Camora' [Grand Comore] and settlement 'Moroni' were names in pirate and treasure hunting stories involving Captain William Kidd (a pirate and treasure hunter) which many 19th century New Englanders – especially treasure hunters – were familiar with."[27] But that's negligibly true. The primary inspiration for Captain Kidd stories and legends, Daniel Defoe's (aka Captain Charles Johnson) 1724 book A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates, mentions Grande Comore once and fails to mention "Moroni/Meroni/Maroni." Neither Grande Comore nor Meroni/Merone/Maroni are connected to Kidd. This is the case for both volumes of General History which can be read/checked online (Vol. 1

When popular maps and other contemporary sources related to Joseph Smith's translation of the Book of Mormon are examined, the possibility that Joseph saw Comoros and Moroni on these maps recedes, and the idea becomes less plausible.

One critic, Noel A. Carmack, took up an exhaustive searching of maps, gazetteers, and other sources proximate to Joseph Smith and observes "that [whether] Joseph Smith Jr. had pre-1830 knowledge of the East Indian Ocean pirate haunt ["pirate haunt" being a place pirates like to frequent habitually]—the Comoro Island group and its sultan town, Moroni—is difficult to conclusively determine." He further states that "[n]o extant pre-1830 chart or map shows Moroni as a place name on the larger island [of Grande Comore]."[19]:p. 130

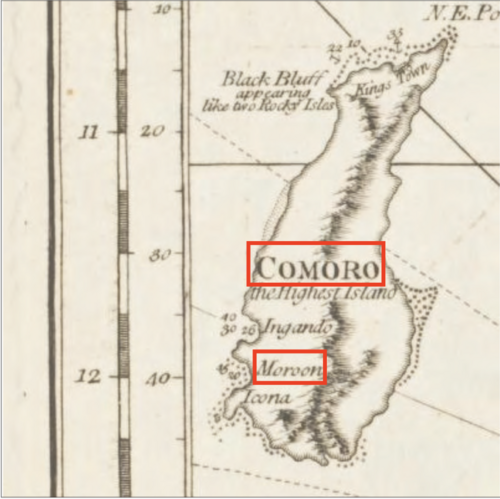

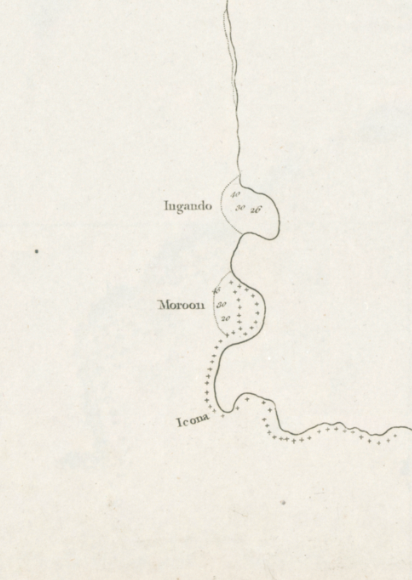

Carmack does note that there is a 1778 map of Grande Comore (called "Comoro" in this map) with the town spelled as "Moroon" (hardly the kind of easy grab for Joseph Smith the critics want):

There is also this detail map from 1774 with the names as "Comoro" and "Moroon":

Are we really going to expect Joseph Smith to look at one of these two maps of one island, Comore, flip the name "Moroon" to become "Moroni", flip the name "Comoro" to "Cumorah", and stick it in the Book of Mormon? When there's one mention of Comore and no mention of Moroon in the source closest to him (General History)?

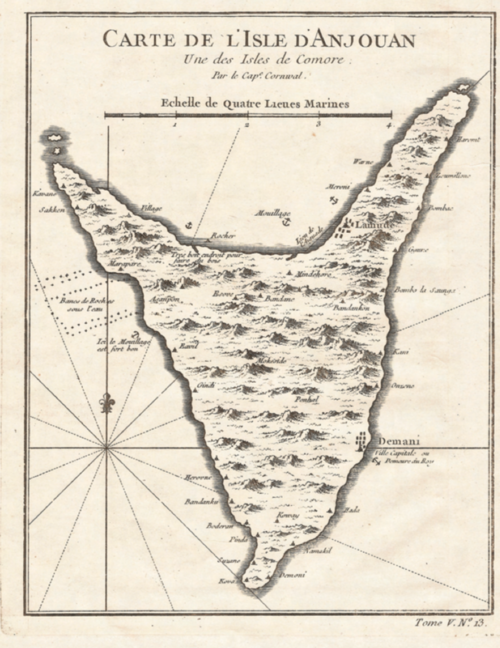

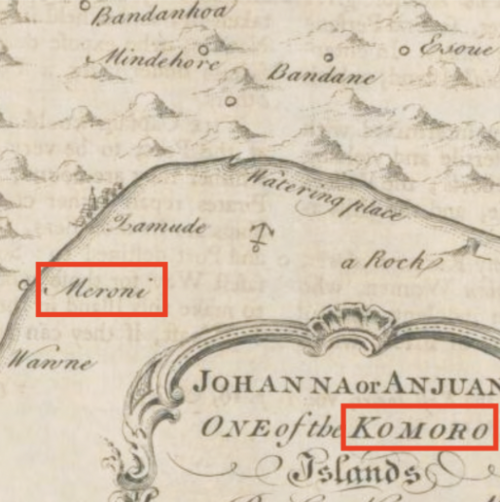

There is also this 1748 map done by French hydrographer Jacque-Nicolas Bellin of the island of Joanna with the names "Comore" and "Meroni" on it:

A 1752 version of the same map has the name spelled as "Merone":

A map from 1745–47 of Anjouan also contains the names "Komoro" and "Meroni":

But are we really going to expect that Joseph Smith is going to look at one of these three maps of one island, two of which are in French (and by which reason there's little motivation for Joseph to seek these maps out), spin the tiny port town "Meroni" and "Comore" to become "Moroni" and "Cumorah", and stick them in the Book of Mormon? When there's relatively little mention of Joanna (and especially in transitory contexts) and no mention of Meroni in the Captain Kidd stories? Why doesn't Joseph Smith look at a globe or other global map? Why a map as specific as one of these?

This is the closest anyone has come to date in placing potential inspiration for both Moroni and Cumorah in the same source.

There is another speculation put forth by critics regarding how Joseph Smith might have heard the names "Moroni" and "Cumorah" that is not related to Captain Kidd. The assumption made on one website is that he "heard about these exotic places from stories of American whalers."[28] The website notes that "The Comoro islands were visited by a large number of American whaling ships beginning before the appearance of The Book of Mormon. Sailors aboard these ships, when they returned to the whaling ports of New England, told of their adventures in the western Indian Ocean. By the time The Book of Mormon first appeared in the 1820s, both Moroni and Comoro were words known to some Americans living in the eastern United States."[28] One would have to assume, however, that Joseph came into contact with "some Americans living in the eastern United States" who were familiar with the names. Critics have posited that there may be such a connection with Solomon Mack, Joseph's grandfather and "a retired sea captain...who plied the same New England waters once haunted by Kidd[.]"[21]:p. 185n53. See also pp. 50–51 therein. Evidence for this, however, is lacking. This "connection" is based on pure conjecture. Given that the stories regarding Kidd mention "Comaro" once and never mention "Moroni" nor "Meroni", how would Solomon Mack even learn the names (or close enough matches that could become the names) "Cumorah" and "Moroni"?

What makes the theory especially lacking in the author's view is that if we're looking for words that are spelled and pronounced roughly the same that Joseph Smith could have cribbed from, we can eventually find what we're looking for, and it would have no bearing on the Book of Mormon's authenticity. To demonstrate, consider an experiment done by David Snell, a Latter-day Saint and host of the Faith and Beliefs segment of the YouTube show Saints Unscripted. Snell made up several names that sounded like Book of Mormon names and picked a random state in the United States: Kentucky. Next, Snell searched for place names in Kentucky that sounded like his made-up Book of Mormon-sounding names. He found matches or near matches for three of his five made-up names. His experiment begins at 4:20 of the video below:

Snell aptly demonstrates the fallacies that critics commit when making the Captain Kidd argument against the Book of Mormon.

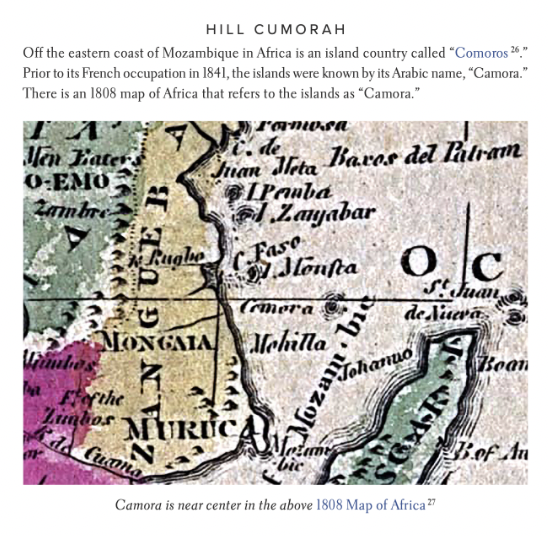

To more closely associate the Book of Mormon with the Comoros Islands, Grant Palmer and other critics note that "Cumorah" is spelled "Camorah" in the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. Both Palmer and Jeremy Runnells claim that "[p]rior to its French occupation in 1841, the islands were known by its Arabic name, 'Camora.'"[27] The name "Cumorah" figures 9 times in the Book of Mormon text, all within the book of Mormon.

The first thing to note is that the spelling of Grande Comore as "Camora" does not appear in any source that the author has been able to locate. Both Grant Palmer and Jeremy Runnells inaccurately identify an 1808 map of the Comoros as calling the group of islands "Camora." The following screenshot is from Runnells' CES Letter:

One will see two things. First, Runnells wrongly claims that "Camora" on the map refers to all the Comoros Islands when it actually refers only to Grande Comore. As evidence, one can see that the islands of Mohilla and Johanna are also mentioned. Mayotta is not mentioned. Second, you'll see that the name here is "Comora" rather than "Camora" as Runnells wrongly claims. For example, compare the "o" in "Comora" on the map above with the "o" of "Mohilla" and the "a" of "Joanno" just below and to the right of Mohilla for evidence that the map indeed says "Comora." So, even with the uniform spelling of Cumorah as "Camorah" in the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon, there is little likelihood that Joseph Smith or Oliver Cowdery cribbed the name from maps of the Comoros.

But pursuing this further, Oliver Cowdery stated that "Camorah" was a spelling error in the July 1835 issue of the Latter Day Saint's Messenger and Advocate. Oliver Cowdery states:

By turning to the 529th and 530th pages of the book of Mormon you will read Mormon's account of the last great struggle of his people, as they were encamped round this hill Cumorah. (It is printed Camorah, which is an error.)

This assertion from Oliver matches evidence from the Printer's Manuscript of the Book of Mormon where the name is spelled "Camorah" once, "Cumorah" seven times, and "Comorah" twice.[29] The portion of the Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon containing the book of Mormon is no longer extant. There were three scribes for the Printer's Manuscript: Oliver Cowdery, an unknown scribe, and Hyrum Smith.[30] The unknown scribe is the one who copied this portion of the book of Mormon from the Original Manuscript to the Printer's Manuscript. This unknown scribe may have been Martin Harris.[31] Royal Skousen argues persuasively that Oliver Cowdery likely meant to spell it "Cumorah" all nine times in the original manuscript and that Harris (when copying the original manuscript to the printer's manuscript) and the typesetter for the Book of Mormon, John Gilbert (when setting the type for the Book of Mormon), thought that some of Cowdery's uses of the letter "u" looked like uses of the letter "o" and "a." Cowdery also sometimes actually did write the wrong letter.[32] These may be the result of Oliver mishearing the pronunciation of Book of Mormon names by Joseph Smith as he dictated the text of the Book of Mormon.

Further, the use of "Cumorah" brings the name into greater parallel with other names in the Book of Mormon, including:

We don't have a Book of Mormon name that includes "cam" or "kam" in its spelling.

There are "com" names in the Book of Mormon, such as:

We have plenty of evidence of the islands in general and/or Grande Comore in particular being referred to as Comora, Comoro, Comore, Comoros, etc. However, the textual evidence documented by Royal Skousen above suggests that the name was intentionally spelled Comorah (or something close to it) first and then changed later to Cumorah.

In each of the above scenarios and with each piece of supposed evidence used, the critics commit the fallacy of appeal to probability (discussed on the linked page) while trying to establish their arguments. Additionally, the probability has receded significantly that Joseph Smith cribbed these names when examining the evidence that the critics use to develop the likelihood.

In his 2014 "debunking" of FAIR's response to the 2013 edition of the CES Letter, Jeremy T. Runnells claimed that "[f]or some Mormon apologists, the evidence is so compelling [that Captain Kidd stories influenced these names] that they have suggested that Lehi and his family may have encountered the Comoros islands on their initial voyage from the Arabian Peninsula to the western hemisphere, and that the Nephite civilization therefore may have retained a collective knowledge of the names of 'Comoros' and 'Moroni'."[33]

Runnells relied on a Wikipedia article that at one point stated the following to make his claim:

Alternative origin of the name

Close-up of 1808 map of Africa with the small Comoros islands labelled "Camora" (near center, just below marked line of latitude) [NOTE from author of this FAIR article: this map is shown above. The Wikipedia editor also wrongly claims that it says "Camora"] Grant H. Palmer has theorized that Smith created the name "Cumorah" through his study of the treasure-hunting stories of Captain William Kidd, because Kidd was said to have buried treasure in the Comoros islands (known by the Arabic name, Camora, prior to being occupied by the French in 1841). Previous to announcing his discovery of the Book of Mormon, Smith had spent several years employed as a treasure seeker. Since the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon printed the name "Cumorah" as "Camorah," it has been suggested that Smith used the name of the islands and applied it to the hill where he found buried treasure—the golden plates. Complementing this proposal is the theory that Smith borrowed the name of a settlement in the Comoros—Moroni—and applied it to the angel which led him to the golden plates.

Others posit that this line of argument commits the logical error of appeal to probability. They also point out that it is highly unlikely that Smith had access to material which would have referred to the then-small settlement of Moroni, particularly since it did not appear in most contemporary gazetteers. However, other Mormon authors have suggested that the ancestors of the Nephite people may have encountered the Comoros islands on their initial voyage from the Arabian Peninsula to the western hemisphere, and that the Nephite civilization therefore may have retained a collective knowledge of the names "Comoros" and "Moroni."[34]

Notice the unusual language in the Wikipedia article, which suggests that Mormon authors accept the Captain Kidd theories. We go to the footnote for more information, which reads:

One Mormon author suggests that Lehi and his family may have re-supplied at Moroni during the voyage: W. Vincent Coon, Choice Above All Other Lands, pg. 68; see also “How Exaggerated Setting for the Book of Mormon Came to Pass” and “A Feasible Voyage." This position reflects the argument of others that the tradition that Lehi and his company voyaged across the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean and finally the Pacific Ocean is "extreme" and non-authoritative: May, Wayne N., THIS LAND: They Came from the East, Vol. 3, pp. 12–15; Olive, P.C., The Lost Empires & Vanished Races of Prehistoric America, p. 39.[34]

The first thing we can rule out with all confidence is that Coon has connected the Captain Kidd stories to the Book of Mormon. He's still faithful, so he's not going to believe that Joseph plagiarized the stories to create the Book of Mormon. The next thing we need to learn is why some believe that the "tradition that Lehi and his company voyaged across the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean, and finally the Pacific Ocean is 'extreme' and non-authoritative." W. Vincent Coon is a hobbyist researcher of the Book of Mormon who believes that the Book of Mormon took place in the Heartland Geography (which encompasses primarily the Eastern to Mid United States). He was trying to find evidence that the Lehites were able to sail southward, away from the Arabian peninsula, around Africa, and then come from the east, through the Atlantic Ocean, to the Florida Peninsula or another area along the eastern seaboard of the United States. He used this as evidence of that assertion. He, like the other Heartland theorists mentioned in the Wikipedia quote, was trying to argue against Limited Geography Theories of Book of Mormon geography that place the Book of Mormon somewhere on the west side of the North American continent. Here's every source cited by Wikipedia that supposedly connects Coon to the Captain Kidd theory and what he actually said about the Comoros:

{

The Comoro archipelago consists of the islands of Grande Comore (Great Comoro), Anjouan (also known as Johanna), Mohilla (Mohely), and Mayotte (Mayotta). They are located at the head of the Mozambique Channel off the coast of Africa. The current capitol, shown on modern maps, is the city of Moroni.

This claim, like many efforts to explain away the Book of Mormon, commits the logical fallacy of the Appeal to probability. This fallacy argues that because something is even remotely possible, it must be true.

When the facts are examined, the possibility of Joseph seeing Comoros and Moroni recedes; the idea becomes unworkable. The following gazetteers from Joseph's era were consulted:

| Title | Relevant Contents |

| Mucullock's Universal Gazateer, 2 vols (1843-4) |

2257 pages of double columned miniscule print, with no reference to Comoros Islands or Moroni. |

| Morris' Universal Gazateer (1821) | 831 pages, no mention of Comoros or Moroni |

|

Brookes Gazateer

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There is no evidence that Joseph saw these maps, or any other, but if he had they would have provided little help.

Furthermore, it is unlikely that any source would have contained the name of "Moroni." That settlement did not become the capital city until 1876 (32 years after Joseph's death and 47 years after the publication of the Book of Mormon), when Sultan Sa'id Ali settled there. At that time it was only a small settlement. Even a century later, in 1958, its population was only 6500.

As previously noted, it is unlikely that any map of the Comoro Archiplego available to Joseph Smith would have contained the name of "Moroni." The capitol city of Moroni was unlikely to have been present on early maps of the Comoros Islands in the 1700's. However, the name "Meroni" actually did appear in a different location on one of the other Comoros Islands on maps dated to 1748, 1752 and 1755. The following 1748 map of the island of Anjouan (also known as Nzwani) has been noted by critics to contain the name "Meroni" or "Merone".[1]

The following map of Anjouan, dated to 1748, also contains the name "Merone."

It is unlikely that Joseph would have seen this, since the name "Comoro" on maps always appears to be associated with the main island "Grande Comore", while the settlement of "Meroni" on Anjoun is too small to appear on such maps showing all four islands. For example, the following 1749 maps of the Comoros clearly labels the main island as "Comore," but the scale of the island of Anjouan obscures the names of any settlements there. In order for Joseph to obtain the name "Meroni" or "Merone" from Anjouan, he would have been required to consult the Anjouan map directly make this connection, since it lists the name "Comore" at the top.

Thomas Stuart Ferguson was an "icon" of Latter-day Saint scholarship.

Author's sources: No source provided.

As John Sorensen, who worked with Ferguson, recalled:

[Stan] Larson implies that Ferguson was one of the "scholars and intellectuals in the Church" and that "his study" was conducted along the lines of reliable scholarship in the "field of archaeology." Those of us with personal experience with Ferguson and his thinking knew differently. He held an undergraduate law degree but never studied archaeology or related disciplines at a professional level, although he was self-educated in some of the literature of American archaeology. He held a naive view of "proof," perhaps related to his law practice where one either "proved" his case or lost the decision; compare the approach he used in his simplistic lawyerly book One Fold and One Shepherd. His associates with scientific training and thus more sophistication in the pitfalls involving intellectual matters could never draw him away from his narrow view of "research." (For example, in April 1953, when he and I did the first archaeological reconnaissance of central Chiapas, which defined the Foundation's work for the next twenty years, his concern was to ask if local people had found any figurines of "horses," rather than to document the scores of sites we discovered and put on record for the first time.) His role in "Mormon scholarship" was largely that of enthusiast and publicist, for which we can be grateful, but he was neither scholar nor analyst.

Ferguson was never an expert on archaeology and the Book of Mormon (let alone on the book of Abraham, about which his knowledge was superficial). He was not one whose careful "study" led him to see greater light, light that would free him from Latter-day Saint dogma, as Larson represents. Instead he was just a layman, initially enthusiastic and hopeful but eventually trapped by his unjustified expectations, flawed logic, limited information, perhaps offended pride, and lack of faith in the tedious research that real scholarship requires. The negative arguments he used against the Latter-day Saint scriptures in his last years display all these weaknesses.

Larson, like others who now wave Ferguson's example before us as a case of emancipation from benighted Mormon thinking, never faces the question of which Tom Ferguson was the real one. Ought we to respect the hard-driving younger man whose faith-filled efforts led to a valuable major research program, or should we admire the double-acting cynic of later years, embittered because he never hit the jackpot on, as he seems to have considered it, the slot-machine of archaeological research? I personally prefer to recall my bright-eyed, believing friend, not the aging figure Larson recommends as somehow wiser. [3]

Daniel C. Peterson and Matthew Roper: [4]

"Thomas Stuart Ferguson," says Stan Larson in the opening chapter of Quest for the Gold Plates, "is best known among Mormons as a popular fireside lecturer on Book of Mormon archaeology, as well as the author of One Fold and One Shepherd, and coauthor of Ancient America and the Book of Mormon" (p. 1). Actually, though, Ferguson is very little known among Latter-day Saints. He died in 1983, after all, and "he published no new articles or books after 1967" (p. 135). The books that he did publish are long out of print. "His role in 'Mormon scholarship' was," as Professor John L. Sorenson puts it, "largely that of enthusiast and publicist, for which we can be grateful, but he was neither scholar nor analyst." We know of no one who cites Ferguson as an authority, except countercultists, and we suspect that a poll of even those Latter-day Saints most interested in Book of Mormon studies would yield only a small percentage who recognize his name. Indeed, the radical discontinuity between Book of Mormon studies as done by Milton R. Hunter and Thomas Stuart Ferguson in the fifties and those practiced today by, say, the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS) could hardly be more striking. Ferguson's memory has been kept alive by Stan Larson and certain critics of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as much as by anyone, and it is tempting to ask why. Why, in fact, is such disproportionate attention being directed to Tom Ferguson, an amateur and a writer of popularizing books, rather than, say, to M. Wells Jakeman, a trained scholar of Mesoamerican studies who served as a member of the advisory committee for the New World Archaeological Foundation?5 Dr. Jakeman retained his faith in the Book of Mormon until his death in 1998, though the fruit of his decades-long work on Book of Mormon geography and archaeology remains unpublished.

Daniel C. Peterson: [5]

In the beginning NWAF was financed by private donations, and it was Thomas Ferguson's responsibility to secure these funds. Devoted to his task, he traveled throughout California, Utah, and Idaho; wrote hundreds of letters; and spoke at firesides, Rotary Clubs, Kiwanis Clubs, and wherever else he could. After a tremendous amount of dedicated work, he was able to raise about twenty-two thousand dollars, which was enough for the first season of fieldwork in Mexico.

Stan Larson, Thomas Stuart Ferguson's biographer, who himself makes every effort to portray Ferguson's apparent eventual loss of faith as a failure for "LDS archaeology,"22 agrees, saying that, despite Ferguson's own personal Book of Mormon enthusiasms, the policy set out by the professional archaeologists who actually ran the Foundation was quite different: "From its inception NWAF had a firm policy of objectivity. . . . that was the official position of NWAF. . . . all field directors and working archaeologists were explicitly instructed to do their work in a professional manner and make no reference to the Book of Mormon."

John Gee: [6]

Biographies like the book under review are deliberate, intentional acts; they do not occur by accident.4 Ferguson is largely unknown to the vast majority of Latter-day Saints; his impact on Book of Mormon studies is minimal.5 So, of all the lives that could be celebrated, why hold up that of a "double-acting sourpuss?"6 Is there anything admirable, virtuous, lovely, of good report, praiseworthy, or Christlike about Thomas Stuart Ferguson's apparent dishonesty or hypocrisy? Larson seems to think so: "I feel confident," Larson writes, "that Ferguson would want his intriguing story to be recounted as honestly and sympathetically as possible" (p. xiv). Why? Do we not have enough doubters? Yet Larson does not even intend to provide the reader with a full or complete biographical sketch of Ferguson's life, since he chose to include "almost nothing . . . concerning his professional career as a lawyer, his various real estate investments, his talent as a singer, his activities as a tennis player, or his family life" (p. xi). In his opening paragraph, Larson warns the reader that he is not interested in a well-rounded portrait of Ferguson. Nevertheless, he finds time to discourse on topics that do not deal with Ferguson's life and only tangentially with his research interest.

B.H. Roberts concluded that Joseph Smith was inspired by Ethan Smith's View of the Hebrews.

Author's sources:

- B.H. Roberts, Studies of the Book of Mormon, 243, 271.

- Wesley P. Lloyd, Private Journal of Wesley P. Lloyd, August 7, 1933.

- Truman G. Madsen, "B.H. Roberts and the Book of Mormon," BYU Studies [Summer 1979] vol. 19, 427-445.

| Main article: | B.H. Roberts and Studies of the Book of Mormon |

The View of the Hebrews theory was examined in detail by B. H. Roberts in 1921 and 1922. Roberts took the position of examining the Book of Mormon from a critical perspective in order to alert the General Authorities to possible future avenues of attack by critics. The resulting manuscripts were titled Book of Mormon Difficulties and A Parallel. Roberts, who believed in a hemispheric geography for the Book of Mormon, highlighted a number of parallels between View of the Hebrews and The Book of Mormon. Roberts stated,

Roberts concluded that, if one assumed that Joseph Smith wrote the Book of Mormon himself, that View of the Hebrews could have provided him with a foundation for creating the book. In fact, many of the issues highlighted by Roberts vanish when a limited geography theory is considered. The acceptance of the View of the Hebrews theory is therefore contingent upon the acceptance of a hemispheric geography model for the Book of Mormon. In order to promote View of the Hebrews as a source, critics necessarily reject any limited geography theory proposal for the Book of Mormon.

In 1985, Roberts' manuscripts were published under the title Studies of the Book of Mormon. This book is used by critics to support their claim that B. H. Roberts lost his testimony after performing the study. Roberts, however, clearly continued to publicly support the Book of Mormon until his death, and reaffirmed his testimony both publicly and in print.

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now