FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Jump to Subtopic:

| Book of Mormon Witnesses | A FAIR Analysis of: Difficult Questions for Mormons, a work by author: The Interactive Bible

|

Prophecies in the Book of Mormon |

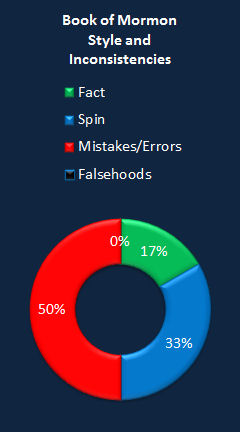

| Claim Evaluation |

| Difficult Questions for Mormons |

|

Response to claim: "If God was inspiring the translation process of the Book of Mormon, why were 4,000 changes necessary?"

The published text of the Book of Mormon has been corrected and edited through its various editions. Many of these changes were made by Joseph Smith himself. Why was this done?

The authenticity of the Book of Mormon is not affected by the modifications that have been made to its text because the vast majority of those modifications are minor corrections in spelling, punctuation, and grammar. The few significant modifications were made by the Prophet Joseph Smith to clarify the meaning of the text, not to change it. This was his right as translator of the book.

These changes have not been kept secret. A discussion of them can be found in the individual articles linked below, and in the references listed below, including papers in BYU Studies and the Ensign.

Joseph Smith taught "the Book of Mormon was the most correct of any book on earth, and the keystone of our religion, and a man would get nearer to God by abiding by its precepts, than by any other book."[1] As the end of the preceding quote clarifies, by "most correct" this he meant in principle and teaching. The authors of the Book of Mormon themselves explained several times that their writing was imperfect, but that the teachings in the book were from God (1 Nephi 19:6; 2 Nephi 33:4; Mormon 8:17; Mormon 9:31-33; Ether 12:23-26).

If one counts every difference in every punctuation mark in every edition of the Book of Mormon, the result is well over 100,000 changes.[2] The critical issue is not the number of changes that have been made to the text, but the nature of the changes.

Most changes are insignificant modifications to spelling, grammar, and punctuation, and are mainly due to the human failings of editors and publishers. For example, the word meet — meaning "appropriate" — as it appears in 1 Nephi 7:1, was spelled "mete" in the first edition of the Book of Mormon, published in 1830. (This is a common error made by scribes of dictated texts.) "Mete" means to distribute, but the context here is obvious, and so the spelling was corrected in later editions.

Some of these typographical errors do affect the meaning of a passage or present a new understanding of it, but not in a way that presents a challenge to the divinity of the Book of Mormon. One example is 1 Nephi 12:18, which in all printed editions reads "a great and a terrible gulf divideth them; yea, even the word of the justice of the Eternal God," while the manuscript reads "the sword of the justice of the Eternal God." In this instance, the typesetter accidentally dropped the s at the beginning of sword.

The current (2013) edition of the Book of Mormon has this notice printed at the bottom of the page opposite 1 Nephi, chapter 1:

Some minor errors in the text have been perpetuated in past editions of the Book of Mormon. This edition contains corrections that seem appropriate to bring the material into conformity with prepublication manuscripts and early editions edited by the Prophet Joseph Smith.

Changes that would affect the authenticity of the Book of Mormon are limited to:

There are surprisingly few meaningful changes to the Book of Mormon text, and all of them were made by Joseph Smith himself in editions published during his lifetime. These changes include:

The historical record shows that these changes were made to clarify the meaning of the text, not to alter it.

Many people in the church experience revelation that is to be dictated (such as a patriarch blessing). They will go back and alter their original dictation. This is done to clarify the initial premonitions received through the Spirit. The translation process for the Prophet Joseph may have occurred in a similar manner.

Response to claim: "Why do the stories and the characters in the Book of Mormon repeat with only minor variations in content and different names given to the characters? Example: Nephi and Moroni sound and act like the same character. "There were other Anti-Christs among the Nephites, but they were more military leaders than religious innovators . . . they are all of one breed and brand; so nearly alike that one mind is the author of them, and that a young and undeveloped, but piously inclined mind. The evidence I sorrowfully submit, points to Joseph Smith as their creator. It is difficult to believe that they are the product of history, that they come upon the scene separated by long periods of time, and among a race which was the ancestral race of the red man of America." (B. H. Roberts - Studies of the Book of Mormon, page 271)."

Response to claim: "Why was the Book of Mormon cast into the KJV style? "...there is a continual use of the 'thee', 'thou' and 'ye', as well as the archaic verb endings 'est' (second person singular) and 'eth' (third person singular). Since the Elizabethan style was not Joseph's natural idiom, he continually slipped out of this King James pattern and repeatedly confused the norms as well. Thus he lapsed from 'ye' (subject) to 'you' (object) as the subject of sentences (e.g. 'Mos. 2:19; 3:34; 4:24), jumped from plural ('ye') to singular ('thou') in the same sentence (Mos. 4:22) and moved from verbs without endings to ones with endings (e.g. 'yields . . . putteth,' 3:19)." (The Use of the Old Testament in the Book of Mormon, by Wesley P. Walters, 1990, page 30)."

Latter-day Saints and the Bible |

|

Reliability of the Bible |

|

Creation |

|

Genesis |

|

Understanding the Bible |

|

Cultural issues |

|

The Bible and the Book of Mormon |

|

| This page is still under construction. We welcome any suggestions for improving the content of this FAIR Answers Wiki page. |

Critics of the Book of Mormon claim that major portions of it are copied, without attribution, from the Bible. They argue that Joseph Smith wrote the Book of Mormon by plagiarizing the Authorized ("King James") Version of the Bible.

LDS scholar Hugh Nibley wrote the following in response to a letter sent to the editor of the Church News section of the Deseret News. His response was printed in the Church News in 1961:[4]

[One of the] most devastating argument[s] against the Book of Mormon was that it actually quoted the Bible. The early critics were simply staggered by the incredible stupidity of including large sections of the Bible in a book which they insisted was specifically designed to fool the Bible-reading public. They screamed blasphemy and plagiarism at the top of their lungs, but today any biblical scholar knows that it would be extremely suspicious if a book purporting to be the product of a society of pious emigrants from Jerusalem in ancient times did not quote the Bible. No lengthy religious writing of the Hebrews could conceivably be genuine if it was not full of scriptural quotations.

...to quote another writer of Christianity Today [magazine],[5] "passages lifted bodily from the King James Version," and that it quotes, not only from the Old Testament, but also the New Testament as well.

As to the "passages lifted bodily from the King James Version," we first ask, "How else does one quote scripture if not bodily?" And why should anyone quoting the Bible to American readers of 1830 not follow the only version of the Bible known to them?

Actually the Bible passages quoted in the Book of Mormon often differ from the King James Version, but where the latter is correct there is every reason why it should be followed. When Jesus and the Apostles and, for that matter, the Angel Gabriel quote the scriptures in the New Testament, do they recite from some mysterious Urtext? Do they quote the prophets of old in the ultimate original? Do they give their own inspired translations? No, they do not. They quote the Septuagint, a Greek version of the Old Testament prepared in the third century B.C. Why so? Because that happened to be the received standard version of the Bible accepted by the readers of the Greek New Testament. When "holy men of God" quote the scriptures it is always in the received standard version of the people they are addressing.

We do not claim the King James Version of the Septuagint to be the original scriptures—in fact, nobody on earth today knows where the original scriptures are or what they say. Inspired men have in every age have been content to accept the received version of the people among whom they labored, with the Spirit giving correction where correction was necessary.

Since the Book of Mormon is a translation, "with all its faults," into English for English-speaking people whose fathers for generations had known no other scriptures but the standard English Bible, it would be both pointless and confusing to present the scriptures to them in any other form, so far as their teachings were correct.

- What is thought to be a very serious charge against the Book of Mormon today is that it, a book written down long before New Testament times and on the other side of the world, actually quotes the New Testament! True, it is the same Savior speaking in both, and the same Holy Ghost, and so we can expect the same doctrines in the same language.

But what about the "Faith, Hope and Charity" passage in Moroni 7꞉45? Its resemblance to 1 Corinthians 13:] is undeniable. This particular passage, recently singled out for attack in Christianity Today, is actually one of those things that turn out to be a striking vindication of the Book of Mormon. For the whole passage, which scholars have labeled "the Hymn to Charity," was shown early in this century by a number of first-rate investigators working independently (A. Harnack, J. Weiss, R. Reizenstein) to have originated not with Paul at all, but to go back to some older but unknown source: Paul is merely quoting from the record.

Now it so happens that other Book of Mormon writers were also peculiarly fond of quoting from the record. Captain Moroni, for example, reminds his people of an old tradition about the two garments of Joseph, telling them a detailed story which I have found only in [th' Alabi of Persia,] a thousand-year-old commentary on the Old Testament, a work still untranslated and quite unknown to the world of Joseph Smith. So I find it not a refutation but a confirmation of the authenticity of the Book of Mormon when Paul and Moroni both quote from a once well-known but now lost Hebrew writing.

Now as to [the] question, "Why did Joseph Smith, a nineteenth century American farm boy, translate the Book of Mormon into seventeenth century King James English instead of into contemporary language?"

The first thing to note is that the "contemporary language" of the country-people of New England 130 years ago was not so far from King James English. Even the New England writers of later generations, like Webster, Melville, and Emerson, lapse into its stately periods and "thees and thous" in their loftier passages.

∗ ∗ ∗ Furthermore, the Book of Mormon is full of scripture, and for the world of Joseph Smith's day, the King James Version was the Scripture, as we have noted; large sections of the Book of Mormon, therefore, had to be in the language of the King James Version—and what of the rest of it? That is scripture, too.

One can think of lots of arguments for using King James English in the Book of Mormon, but the clearest comes out of very recent experience. In the past decade, as you know, certain ancient nonbiblical texts, discovered near the Dead Sea, have been translated by modern, up-to-date American readers. I open at random a contemporary Protestant scholar's modern translation of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and what do I read? "For thine is the battle, and by the strength of thy hand their corpses were scattered without burial. Goliath the Hittite, a mighty man of valor, thou didst deliver into the hand of thy servant David."[6]

Obviously the man who wrote this knew the Bible, and we must not forget that ancient scribes were consciously archaic in their writing, so that most of the scriptures were probably in old-fashioned language the day they were written down. To efface that solemn antique style by the latest up-to-date usage is to translate falsely.

At any rate, Professor Burrows, in 1955 (not 1835!), falls naturally and without apology into the language of the King James Bible. Or take a modern Jewish scholar who purposely avoids archaisms in his translation of the Scrolls for modern American readers: "All things are inscribed before Thee in a recording script, for every moment of time, for the infinite cycles of years, in their several appointed times. No single thing is hidden, naught missing from Thy presence."[7] Professor Gaster, too, falls under the spell of our religious idiom. [A more recent example of the same phenomenon in the twenty-first century is discussed here.]

By frankly using that idiom, the Book of Mormon avoids the necessity of having to be redone into "modern English" every thirty or forty years. If the plates were being translated for the first time today, it would still be King James English!"

Quotations from the Bible in the Book of Mormon are sometimes uncited quotes from Old Testament prophets on the brass plates, similar to the many unattributed Old Testament quotes in the New Testament; others are simply similar phrasing emulated by Joseph Smith during his translation.

Oddly enough, this actually should not lead one to believe that Joseph Smith simply plagiarized from it. Using the Original and Printer's Manuscripts of the Book of Mormon, Latter-day Saint scholar Royal Skousen has identified that none of the King James language contained in the Book of Mormon could have been copied directly from the Bible. He deduces this from the fact that when quoting, echoing, or alluding to the passages, Oliver (Joseph's amanuensis for the dictation of the Book of Mormon) consistently misspells certain words from the text that he wouldn't have misspelled if he was looking at the then-current edition of the KJV.[8]

Critics also fail to mention that even if all the Biblical passages were removed from the Book of Mormon, there would be a great deal of text remaining. Joseph Smith was able to produce long, intricate religious texts without using the Bible; if he was trying to deceive people, why did he "plagiarize" from the one book—the Bible—which his readership was sure to recognize? The Book of Mormon itself declares that it came forth in part to support the Bible (2 Nephi 29). Perhaps the inclusion of KJV text can allow us to know those places where it is engaging the Bible rather than just cribbing from it. If we didn't get some KJV text, we might think that the Nephites were trying to communicate an entirely different message.

When considering the the data, Skousen proposes as one scenario that, instead of.Joseph or Oliver looking at a Bible (which is now confirmed by the manuscript evidence and the unequivocal statements of the witnesses to the translation to the Book of Mormon that Joseph employed no notes nor any other reference materials), that God was simply able to provide the page of text from the King James Bible to Joseph's mind and then Joseph was free to alter the text as would be more comprehensible/comfortable to his 19th century, Northeastern, frontier audience. This theology of translation may feel foreign and a bit strange to some Latter-day Saints, but it seems to fit well with the Lord's own words about the nature of revelation to Joseph Smith. Latter-day Saints should take comfort in fact that the Lord accommodates his perfection to our own weakness and uses our imperfect language and nature for the building up of Zion on the earth. It may testify to the fact that God views us not only as creatures but as Gods ourselves—with abilities that can be used effectively to call others to repentance and literally become like Him.

Learn More About Parts 5 and 6 of Volume 3 of the Critical Text Project of the Book of Mormon

Standford Carmack, "Bad Grammar in the Book of Mormon Found in Early English Bibles" Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020).

Stan Spencer, "Missing Words: King James Bible Italics, the Translation of the Book of Mormon, and Joseph Smith as an Unlearned Reader" Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 38 (2020).

Critic Fawn Brodie claimed the following in her book No Man Knows My History: the Life of Joseph Smith

Many stories [Joseph Smith] borrowed from the Bible [for the creation of the Book of Mormon]. The daughter of Jared, like Salome, danced before a king and a decapitation followed. Aminadi, like Daniel, deciphered handwriting on a wall, and Alma was converted after the exact fashion of St. Paul. The daughters of the Lamanites were abducted like the dancing daughters of Shiloh; and Ammon, like the American counterpart of David, for want of a Goliath slew six sheep-rustlers with his sling.[9]

So how can we reconcile this? Did Joseph Smith actually use characters from the Bible as templates for Book of Mormon characters?

This article seeks to answer this question.

One thing that should be pointed out very clearly is that a few similarities do not equate to causal influence. Just because one two characters in two books are both said to have looked at a tree longingly in Central Park in New York City, doesn't mean that the one author read the other and copied the story. The same holds for the Book of Mormon as will be argued in more detail below.

Book of Mormon Central has produced an excellent article that may explain this type of "plagiarism" in the Book of Mormon. That article is reproduced in full (including citations for easy reference) below:

Book of Mormon Central has also produced this video on the subject:

So how then does this literary device then work with different characters in the Book of Mormon? Let’s take the claims one by one.

BYU Professor Nicholas J. Frederick has authored an insightful paper on this very question in the book Illuminating the Jaredite Records published by the Book of Mormon Academy.[25]

Frederick points out that similarities do exist. Both stories involve:

But Frederick also points out important dissimilarities:

Frederick proposes a few possible scenarios to answer the question of how we got a story this similar to Salome in the Book of Mormon:

Hugh Nibley writes that the account of the daughter of Jared is more similar to ancient accounts that use the same motifs of the dancing princess, old king, and challenger to the throne of the king.

This is indeed a strange and terrible tradition of throne succession, yet there is no better attested tradition in the early world than the ritual of the dancing princess (represented by the salme priestess of the Babylonians, hence the name Salome) who wins the heart of a stranger and induces him to marry her, behead the whole king, and mount the throne. I once collected a huge dossier on this awful woman and even read a paper on her at an annual meeting of the American Historical Association.[30] You find out all about the sordid triangle of the old king, the challenger, and the dancing beauty from Frazer, Jane Harrison, Altheim, B. Chweitzer, Franell, and any number of folklorists.[31] The thing to note especially is that there actually seems to have been a succession rite of great antiquity that followed this pattern. It is the story behind the rites at Olympia and Ara Sacra and the wanton and shocking dances of the ritual hierodules throughout the ancient world.[32] Though it is not without actual historical parallels, as when in A.D. 998 the sister of the khalif obtained as a gift the head of the ruler of Syria,[33] the episode of the a dancing princess is at all times essentially a ritual, and the name of Salome is perhaps no accident, for her story is anything but unique. Certainly the book of Ether is on the soundest possible ground in attributing the behavior of the daughter of Jared to the inspiration of ritual texts – secret directories on the art of deposing an aging king. The Jaredite version, incidentally, is quite different from the Salome story of the Bible, but is identical with many earlier accounts that have come down to us in the oldest records of civilization.[34]

The one connection, that both men interpreted the writings of God on a wall, is tenuous. Again, just because stories parallel each other in one respect, doesn't mean that one is dependent on the other for inspiration.

Brant A. Gardner observes:

The story of Aminadi [in Alma 10:2-3] clearly parallels Daniel 5:5-17 with a prophet interpreting Yahweh's writing on a wall, although there is no language dependency. There can be no textual dependency because Daniel describes events during the Babylonian captivity that postdates Lehi's departure from Jerusalem. Just as Alma's conversion experience was similar to, but different from, Paul's (see commentary accompanying Mosiah 27:10-11), it is probable that, if we had a fuller version of Aminadi's story, we would see both similarities and differences.[35]

This criticism needs to be looked at in more depth since it has received the largest amount of attention from critics, apologists, and other scholars. We have an entire page at the link below:

Latter-day Saint philosopher, historian, and Book of Mormon Scholar Alan Goff wrote a short, insightful book chapter on this parallel back in 1991:

| Then they said, Behold, there is a feast of the Lord in Shiloh yearly in a place which is on the north side of Bethel, on the east side of the highway that goeth up from Bethel to Shechem, and on the south of Lebonah. Therefore they commanded the children of Benjamin, saying, Go and lie in wait in the vineyards; and see, and behold, if the daughters of Shiloh come out to dance in dances, then come ye out of the vineyards, and catch you every man his wife of the daughters of Shiloh, and go to the land of Benjamin (Judges 21:19-21). | Now there was a place in Shemlon where the daughters of the Lamanites did gather themselves together to sing, and to dance, and to make themselves merry. And it came to pass that there was one day a small number of them gathered together to sing and to dance (Mosiah 20:1-2). |

The only similarity between these two stories is that both men killed another individual or group with a sling. How many stories can we find authored before the Book of Mormon was translated where a protagonist defeats an antagonist with a sling? Hundreds. The comparison is utterly nonsensical and flimsy.

The presence of similarities does not seem to do anything to belief in the authenticity of the Book of Mormon. More research is sure to be forthcoming on the type-scene in the Book of Mormon and readers are encouraged to pay attention for the arrival of that literature.

The Book of Mormon records the conversion and ministry of a young man named Alma. Alma, along with four companions known as the four sons of Mosiah, are recorded as going about trying to lead people away from God's church. During the apex of their efforts, an angel appears to them, causing them to fall and tremble because of fear. Because of this experience, Alma was converted to the Gospel and labored to spread it throughout his life.

In 2002, critic Grant H. Palmer asserted that this conversion narrative and much of the rest of Alma’s story "seems to draw" on Paul’s story of conversion and ministry in the New Testament as a narrative structure.[39]

In particular, Palmer asserts that the following parallels exist between the stories of Alma and Paul:

For point ten, Palmer cites 16 examples in which Alma and Paul used similar phrases in their teaching.

This article will seek to examine this criticism and address it in a way that makes sense given orthodox Latter-day Saint theological commitments.

We should consider a few things about parallels themselves before getting into the specific parallels that Palmer sees between Alma and Paul.

Parallels are easy to create, and the way they are phrased can make them seem more similar than they are—and obscure important differences. For example, the shaking of the earth in Alma's account of conversion is particularly important to that story, but Palmer leaves it out because it isn't parallel.

Secondly, there are likely to be some parallels because it would have been difficult for Joseph as a translator not to see them, and perhaps translated Alma's account in ways that seem parallel to Paul.

Third, the question is whether the parallels show dependence. They can show similarity, but don't show that the Book of Mormon account had to be connected literarily to the first. There is not reason to believe that the experiences could not have been similar. God is the same and humans can have similar experiences with him.

Are we really to believe that there can't be two narratives of men persecuting a church organization, being visited by a heavenly messenger exhorting them to repent, having them converted to preaching repentance, supporting themselves by their own labor while they preach, and being freed from bands and prison without one narrative being literately dependent on the other?

Scholars John Welch and John F. Hall created a chart noting similarities and differences between Alma's and Paul's conversion.[40] They explain:

The conversions of Saul of Tarsus on the road to Damascus and of Alma the Younger in the land of Zarahemla are similar in certain fundamental respects, as one would expect since the source of their spiritual reversals was one and the same. Interestingly, in each case we have three accounts of their conversions: Paul’s conversion is reported in Acts 9, 22, and 26. Alma’s conversion is given in Mosiah 27, Alma 36, and 38. No two of these accounts are exactly the same. The columns on the far right and left sides of chart 15–17 show the verses of these six accounts in which each element either appears or is absent. Down the middle are found the elements shared by both Paul and Alma, and off center are words or experiences unique to either Paul or Alma. In sum, the personalized differences significantly offset and highlight the individual experiences in the two conversions.

The chart they created can be seen here.

With those thoughts in place, we can begin to examine each supposed parallel listed by Palmer and highlight areas where Palmer stretches evidence or misreads it given faulty starting assumptions. The parallels are examined below. Each narrative has important similarities and dissimilarities that need to be considered in isolation in order to understand how combining them too hastily can lead to misunderstandings and faulty premises for criticism.

A fairly innocuous parallel when taken by itself and one that we could establish with many other books. This parallel can only be seen as convincing when taken in stride with other parallels. Thus we'll have to examine others to see how strong and unique they actually are. This parallel and the next are probably better suited being combined with parallels three and four as one parallel. Both are so naturally tied into 3/4 that they function better as one parallel. Palmer may be trying to craft more parallels than necessary to make this criticism look more persuasive than it actually is.

Both Alma and Paul were indeed seeking to destroy the Church.

Paul is on the road to Damascus when he has his vision. The Book of Mormon doesn't give us any details as to the location of Alma and his companions when confronted by the angel. It mentions that an angel came in a cloud and that the earth shook upon which Alma and the four sons of Mosiah stood, but it doesn't give specific details as to where they were. Maybe they were in a tent looking out of it while the angel came down. We don't know for sure.

We know that Alma was with four other people at the time of the heavenly appearance. No info is given for how many companions Saul had with him while on the road to Damascus.

"The next slight difference comes in the angel's appearance to them. To Alma the angel comes in a cloud and to Saul with a bright light from heaven (Acts 9:3)."[41]

"The next difference is the description of the voice. No description accompanies the voice in Paul's account, but in Alma's it is 'a voice of thunder' that shakes the earth. Both Saul and Alma fall to the ground—Saul/Paul because he appears to recognize majesty, and with Alma, as a result of the earth's shaking."[41]:4:450

In both accounts, all fall to the ground and all hear the voice of the angel. "The difference is that, in the Book of Mormon account, all fall and all see the messenger (v. 18)…In the Old World example, the companions heard a voice, but the record does not allow us to infer either that they understood it or assumed it to be divine."[41]:4:451

In Alma's case, it is an angel that is not God the Father nor Jesus Christ that appears to him and his companions. In Saul's/Paul's case, it is Jesus Christ.

"The similarity to Paul's experience is that 'persecution' is part of the divine message in both cases. In Saul's case, however, it is Christ who is persecuted and in Alma's it is the church. The fact of persecution exists in both cases; but in the New World, Alma's persecution precedes Jesus's coming in the flesh. Thus, in one sense, there was no person with which the church might be directly identified and against whom one might persecute as in the New Testament example. Alma's version of apostasy was almost certainly like that of Noah and his priests in which he accepted much of the competing religion but also held some beliefs of the Mosaic law. In this case, Alma and the sons of Mosiah could not have accepted a declaration like that given to Saul because they would not have believed that they were persecuting Yahweh himself, only those who believed in the future Atoning Messiah. Nevertheless, the messenger declares that the church was equated with Yahweh. Alma and the sons of Mosiah were not persecuting people who believed in a nonexistent being, but they were directly persecuting their own God."[41]:4:451–52

Both indeed preached the Gospel. Alma ascended to political power after his conversion and then relinquished it before entering ministry whereas Paul had political power, relinquished it, and did not ascend to it again after conversion and before entering ministry.

Paul and Alma did not perform the same miracle. In Alma's passages, he implores the Lord to heal Zeezrom and allow him to walk whereas in Paul's passages, he merely commands the man from Lystra to walk. The nature of the ailment of the person healed is different between the accounts as well. In Alma's account, Zeezrom is in bed and has a fever. In Paul's account, the man is lame and has not been able to walk since he was born.

This is true.

Paul and Silas were placed in prison following their being stripped of their clothes and whipped. Alma and Amulek were also confined to prison after being stripped of clothes but suffered being smitten, spit upon, and having people gnash their teeth at them. Paul was imprisoned three times throughout his ministry and Alma once. It was on the first arrest that Paul was taken with Silas and put into prison.

Palmer is entirely wrong that an earthquake resulted in Alma's bands being loosed. Alma's bands are loosed by God and then the prison walls shake and tumble whereas with Paul, it's the foundations of the prison that shake first, doors open, and then the bands are loosed. The walls of the prison in Paul's narrative do not tumble down. We aren't given more specific information in the passages from Acts whether it was God or not that loosed the bands.

Palmer next suggests that both authors used the same phrases in teaching. Yet, the Book of Mormon is replete with phrasing from the New Testament. This is not something unique to Alma and his conversion narratives and thus it can't be used as a peculiarity to establish Joseph Smith's dependence on Paul's conversion narratives for Alma. This does, however, provide potential fodder for saying that Joseph Smith lifted New Testament language to create the Book of Mormon. FAIR has collected links to 9 articles from Book of Mormon Central on this page that explain why New Testament language might appear so frequently in the Book of Mormon text. We strongly encourage readers to read those and see what theories make the most sense for them given commitments to belief in the historicity of the Book of Mormon.

So there are some parallels between the accounts of Alma and Paul's conversion and ministry. It's important to remember that just because there are a few parallels that this does not equate to causal influence by one story on another. That is, just because there are parallels between the stories of Alma and Paul, doesn't mean that Joseph used Paul as a template for creating Alma. There are many important dissimilarities between the two stories and the similarities are more general instead of the unique type of similarity you might look for to establish the type of relationship Palmer wants you to see in the story.

A much more detailed response to this criticism was given by Latter-day Saint philosopher and historian Alan Goff who, in a long paper written for and published in Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship, argues that "[b]oth the New and Old Testaments appropriate an ancient narrative genre called the prophetic commissioning story. Paul’s and Alma’s commissioning narratives hearken back to this literary genre, and to refer to either as pilfered is to misunderstand not just these individual narratives but the larger approach Hebraic writers used in composing biblical and Book of Mormon narrative."[42] We urge readers to read his paper in full and get familiar with it.

More scholarship on this issue is bound to be forthcoming in the future as scholars continue to wrestle with how the Book of Mormon was translated and how the Book of Mormon's ancient story potentially interacts with the broader ancient Mesopotamian and Mediterranean world.

The story often referred to as Alma’s conversion narrative is too often interpreted as a simplistic plagiarism of Paul’s conversion-to-Christianity story in the book of Acts. Both the New and Old Testaments appropriate an ancient narrative genre called the prophetic commissioning story. Paul’s and Alma’s commissioning narratives hearken back to this literary genre, and to refer to either as pilfered is to misunderstand not just these individual narratives but the larger approach Hebraic writers used in composing biblical and Book of Mormon narrative. To the modern mind the similarity in stories triggers explanations involving plagiarism and theft from earlier stories and denies the historicity of the narratives; ancient writers — especially of Hebraic narrative — had a quite different view of such concerns. To deny the historical nature of the stories because they appeal to particular narrative conventions is to impose a mistaken modern conceptual framework on the texts involved. A better and more complex grasp of Hebraic narrative is a necessary first step to understanding these two (and many more) Book of Mormon and biblical stories.

If Joseph was a fraud, why would he plagiarize the one text—the King James Bible—which his readers would be sure to know, and sure to react negatively if they noticed it? The Book of Mormon contains much original material—Joseph didn't "need" to use the KJV; he is obviously capable of producing original material.

The Book of Mormon claims to be a "translation." Therefore, the language used is that of Joseph Smith. Joseph could choose to render similar (or identical) material using King James Bible language if that adequately represented the text's intent.

The translation language may resemble Malachi, but the work is not attributed to Malachi. Only if we presume that the Book of Mormon is a fraud at the outset is this proof of anything. If we assume that it is a translation, then the use of Bible language tells us merely that Joseph used biblical language.

Joseph used entire chapters (e.g., 3 Nephi 12-14 based on biblical texts that he did not claim were quotations from original texts (even Malachi is treated this way by Jesus in 3 Nephi 24-25. If these are not a problem, then a resemblance to biblical language elsewhere is not either, since that is simply how Joseph translated.

Critical sources |

|

Critic David P. Wright argues that "Alma chapters 12-13, traditionally dated to about 82 B.C.E., depends in part on the New Testament epistle to the Hebrews, dated by critical scholars to the last third of the first century C.E. The dependence of Alma 12-13 on Hebrews thus constitutes an anachronism and indicates that the chapters are a composition of Joseph Smith."[43]

"Wright contends that Alma 13:17-19 is a reworking of Hebrews 7:1-4, noting six elements shared by the two texts and appearing in the same order in both.[44]"[45]

This article gives some resources on approaching a response to this criticism.

This argument is one that is long, detailed, and hard to summarize easily. The reader will simply have to be directed to resources that will help them in evaluating this criticism as they read from scholars. At another point in the future, perhaps a clearer summary can be presented up front. But, for now, we direct the reader elsewhere.

John Tvedtnes was one of the first to respond to Wright’s contentions in the Review of Books on the Book of Mormon back in 1994. Tvedtnes argues that the parallels do not come from Joseph Smith reading Hebrews 7 but instead that both Hebrews 7 and Alma 13 share in thought from an earlier source discussing Melchizedek. Readers can find a link to his paper at the citation below.[46]

Three years before Wright published on this topic, John W. Welch had written a paper on the Melchizedek material in Alma 12-13. While not giving a direct treatment of Wright’s argument nor having consciousness of it, Welch provides insightful comparisons between Alma 13, Hebrews 7, Genesis 12, and extrabiblical lore about Melchizedek to elucidate how Alma interprets Genesis and frames concepts of priesthood and thus how it differs from Hebrews 7. Readers are strongly encouraged to read Welch’s paper. Link is in the footnotes below.[47]

Book of Mormon Central has written an accessible distillation and analysis of the Melchizedek material in Alma 13 that readers are encouraged to visit.

Eminent Book of Mormon scholar Brant A. Gardner has written a commentary on Alma 12 and 13 with Wright’s argument and Tvedtnes' response in consciousness and offers a subtle response to both. In that commentary, "[he takes] the position that the construction of Alma’s text follows a different logic and theme than that of Hebrews. [He develops] this argument in the commentary on the individual verses [of Alma 13]."[48]

When taking in all of the arguments of these scholars, it is the belief of the author that readers will emerge with a nuanced perspective that holds to the conviction that the Book of Mormon is an ancient text and takes into account the theological and linguistic complexities that might emerge from the type of project that Joseph Smith was engaged in: producing a translation of an ancient record for the benefit and understanding of a modern audience.

Some claim that Helaman 12:25-26 quotes John 5:29 [49]:

And I would that all men might be saved. But we read that in the great and last day there are some who shall be cast out, yea, who shall be cast off from the presence of the Lord. [26] Yea, who shall be consigned to a state of endless misery, fulfilling the words which say: They that have done good shall have everlasting life; and they that have done evil shall have everlasting damnation. And thus it is. Amen. (Helaman 12꞉25-26)

It is claimed that the "reading" referred to is from John:

And shall come forth; they that have done good, unto the resurrection of life; and they that have done evil, unto the resurrection of damnation.(John 5:29:{{{4}}})

The problem with this is that Helaman 12:26 doesn't quote John, but at best paraphrases. The issue is over the word "read" that is used to force the connection. We must remember that the speaker in this case is Mormon, who was writing more than three centuries after Jesus Christ, and who had access to a large variety of Nephite records.

For example, the following Book of Mormon verses are potential sources for these ideas:

If they be good, to the resurrection of everlasting life; and if they be evil, to the resurrection of damnation....

Mormon had access to this text, and it approximates that used in Helaman quite closely. (Remember that many who criticize the Book of Mormon on this point claim that Helman is speaking pre-Jesus Christ, rather than the editor Mormon, who is post-Jesus and thus post-3 Nephi.)

Other options include those listed below.

For the time cometh, saith the Lamb of God, that I will work a great and a marvelous work among the children of men; a work which shall be everlasting, either on the one hand or on the other—either to the convincing of them unto peace and life eternal, or unto the deliverance of them to the hardness of their hearts and the blindness of their minds unto their being brought down into captivity, and also into destruction, both temporally and spiritually, according to the captivity of the devil, of which I have spoken.

Therefore, cheer up your hearts, and remember that ye are free to act for yourselves—to choose the way of everlasting death or the way of eternal life.

"And also, what is this that Ammon said—If ye will repent ye shall be saved, and if ye will not repent, ye shall be cast off at the last day?"

While Mormon in Helaman doesn't use the "resurrection of life" and "resurrection of damnation" that is found in John, it does use the "shall be cast off" and "the last day". Now it isn't exact either, and its quite likely that it isn't a direct quote of this passage.

Another source of this teaching in the Book of Mormon comes in 2 Nephi 2, in particular in verse 26:

"And the Messiah cometh in the fulness of time, that he may redeem the children of men from the fall. And because that they are redeemed from the fall they have become free forever, knowing good from evil; to act for themselves and not to be acted upon, save it be by the punishment of the law at the great and last day, according to the commandments which God hath given." (2 Nephi 2꞉26)

Mormon also uses this passage when he writes in Words of Mormon 1꞉11:

"And they were handed down from king Benjamin, from generation to generation until they have fallen into my hands. And I, Mormon, pray to God that they may be preserved from this time henceforth. And I know that they will be preserved; for there are great things written upon them, out of which my people and their brethren shall be judged at the great and last day, according to the word of God which is written."

Given that Mormon is writing well after Jesus' visit to the Nephites, it is also possible that he is citing another Christian text from that period—it would be logical for Jesus to teach something similar to John 5:29 among the Nephites, though as we have seen there were ample other pre-crucifixion texts available to the Nephites as well.

Since we have this idea present in Alma 22:6 (the missionary Aaron quoting Alma the Younger), it seems likely that this was an idea that was taught commonly among the Nephites. This is confirmed by the other passages cited. So whether or not we have the source in one of these passages that the Book of Helaman is referring to, we can see how the passage in Helaman reflects a Nephite theology and need not be a New Testament theology introduced anachronistically.

Ultimately, the idea is not a particularly complex one, and could easily have had multiple sources or approximations. Mormon need not be even citing a particular text, but merely indicating that one can "read" this idea in a variety of Nephite texts, as demonstrated above.

Thus, the claim of plagiarism seems forced, since there are Nephite texts which more closely approximate the citation than does the gospel of John, and a precise citation is not present in any case.

Critical sources |

|

Notes

Response to claim: "Was there a room full of plates in a secret chamber in the hill near Joseph's house as he and Brigham Young said?"

On June 17, 1877, Brigham Young related the following at a conference:

I believe I will take the liberty to tell you of another circumstance that will be as marvelous as anything can be. This is an incident in the life of Oliver Cowdery, but he did not take the liberty of telling such things in meeting as I take. I tell these things to you, and I have a motive for doing so. I want to carry them to the ears of my brethren and sisters, and to the children also, that they may grow to an understanding of some things that seem to be entirely hidden from the human family. Oliver Cowdery went with the Prophet Joseph when he deposited these plates. Joseph did not translate all of the plates; there was a portion of them sealed, which you can learn from the Book of Doctrine and Covenants. When Joseph got the plates, the angel instructed him to carry them back to the hill Cumorah, which he did. Oliver says that when Joseph and Oliver went there, the hill opened, and they walked into a cave, in which there was a large and spacious room. He says he did not think, at the time, whether they had the light of the sun or artificial light; but that it was just as light as day. They laid the plates on a table; it was a large table that stood in the room. Under this table there was a pile of plates as much as two feet high, and there were altogether in this room more plates than probably many wagon loads; they were piled up in the corners and along the walls. The first time they went there the sword of Laban hung upon the wall; but when they went again it had been taken down and laid upon the table across the gold plates; it was unsheathed, and on it was written these words: "This sword will never be sheathed again until the kingdoms of this world become the kingdom of our God and his Christ." [1]

There are at least ten second hand accounts describing the story of the cave in Cumorah, however, Joseph Smith himself did not record the incident. [2] As mentioned previously, the Hill Cumorah located in New York state is a drumlin: this means it is a pile of gravel scraped together by an ancient glacier. The geologic unlikelihood of a cave existing within the hill such as the one described suggests that the experience related by the various witnesses was most likely a vision, or a divine transportation to another locale (as with Nephi's experience in 1 Nephi 11꞉1). John Tvedtnes supports this view:

The story of the cave full of plates inside the Hill Cumorah in New York is often given as evidence that it is, indeed, the hill where Mormon hid the plates. Yorgason quotes one version of the story from Brigham Young and alludes to six others collected by Paul T. Smith. Unfortunately, none of the accounts is firsthand. The New York Hill Cumorah is a [drumlin] laid down anciently by a glacier in motion. It is comprised of gravel and earth. Geologically, it is impossible for the hill to have a cave, and all those who have gone in search of the cave have come back empty-handed. If, therefore, the story attributed to Oliver Cowdery (by others) is true, then the visits to the cave perhaps represent visions, perhaps of some far distant hill, not physical events.[3]

Given that the angel Moroni had retrieved the plates from Joseph several times previously, it is not unreasonable to assume that he was capable of transporting them to a different location than the hill in New York. As Tvedtnes asks, "If they could truly be moved about, why not from Mexico, for example?"[3]

Response to claim: "Why were clichéd Indian phrases like "Nine Moons" in (Omni 1:21) or "Great Spirit" in (Alma 19:25-27) included?"

Response to claim: "How did the Jaredites come up with the same rare idea of writing on plates 2,000 years before Lehi when such a record keeping system is virtually unknown?"

When it first appeared, the Book of Mormon was attacked for the alleged absurdity of having been written on golden plates and its claim of the existence of an early sixth century B.C. version of the Hebrew Bible written on brass plates. Today, however, there are numerous examples of ancient writing on metal plates. Ironically, some now claim instead that knowledge of such plates was readily available in Joseph Smith's day. Hugh Nibley's 1952 observation seems quite prescient: "it will not be long before men forget that in Joseph Smith's day the prophet was mocked and derided for his description of the plates more than anything else." [4]

Recent reevaluation of the evidence now points to the fact that the Book of Mormon's description of sacred records written on bronze plates fits quite nicely in the cultural milieu of the ancient eastern Mediterranean.

One of the earliest known surviving examples of writing on "copper plates" are the Byblos Syllabic inscriptions (eighteenth century B.C.), from the city of Byblos on the Phoenician coast. The script is described as a "syllabary [which] is clearly inspired by the Egyptian hieroglyphic system, and in fact is the most important link known between the hieroglyphs and the Canaanite alphabet."[5]

It would not be unreasonable to describe the Byblos Syllabic texts as eighteenth century B.C. Semitic "bronze plates" written in "reformed Egyptian characters."[6]

Walter Burkert, in his study of the cultural dependence of Greek civilization on the ancient Near East, refers to the transmission of the practice of writing on bronze plates (Semitic root dlt) from the Phoenicians to the Greeks. "The reference to 'bronze deltoi [plates, from dlt ]' as a term [among the Greeks] for ancient sacral laws would point back to the seventh or sixth century [B.C.]" as the period in which the terminology and the practice of writing on bronze plates was transmitted from the Phoenicians to the Greeks.[7]

Students of the Book of Mormon will note that this is precisely the time and place in which the Book of Mormon claims that there existed similar bronze plates which contained the "ancient sacred laws" of the Hebrews, the close cultural cousins of the Phoenicians.

Burkert also maintains that "the practice of the subscriptio in particular connects the layout of later Greek books with cuneiform practice, the indication of the name of the writer/author and the title of the book right at the end, after the last line of the text; this is a detailed and exclusive correspondence which proves that Greek literary practice is ultimately dependent upon Mesopotamia. It is necessary to postulate that Aramaic leather scrolls formed the connecting link."[8]

Joseph Smith wrote that "the title page of the Book of Mormon is a literal translation, taken from the very last leaf, on the left hand side of the collection or book of plates, which contained the record which has been translated."[9]

This idea would have been counterintuitive in the early nineteenth century when "Title Pages" appeared at the beginning, not the end, of books.

Why, then, did Joseph claim the Book of Mormon practiced subscriptio—writing the name of the author and title at the end of the book? If the existence of the practice of subscriptio among the Greeks represents "a detailed and exclusive correspondence which proves that Greek literary practice is ultimately dependent upon Mesopotamia [via Syria]," as Burkert claims, cannot the same thing be said of the Book of Mormon—that the practice of subscriptio represents "a detailed and exclusive correspondence" which offers proof that the Book of Mormon is "ultimately dependent" on the ancient Near East?

William J. Adams Jr.,

Lehi sent his sons back to Jerusalem to obtain scriptures engraved on "brass plates" (1 Nephi 3 and 4). Later we read that Lehi and his son, Nephi, kept records on metal "plates" (1 Nephi 6 and 9). These incidences raise the question: Did others in Lehi's Jerusalem inscribe records on metal plates?

The use of metal plates upon which records are inscribed is fairly well attested throughout the Middle and Far East from many centuries before to many centuries after Lehi, but none so far appear to be from Lehi's seventh-century BC Judea.

This lack of metal inscriptions from Judea could be interpreted to mean that (1) Judeans did not write on metal plates, or (2) archaeology has not found artifacts which would support the practice of writing on metal plates in seventh-century BC Jerusalem. Alternative 2 seems to have been the problem, for inscribed silver plates have been excavated only recently.[10]

Sidney B. Sperry,

Most contemporary Old Testament scholars question whether Moses wrote the Pentateuch, but the Book of Mormon affirms Moses' authorship. Questions arise as to how Jeremiah's prophecies appeared on the brass plates and what the nature of the Book of the Law was. According to the brass plates Laban and Lehi were descendants of Manasseh. How then did they come to be living in Jerusalem? The brass plates, on which may be found lost scripture, may have been the official scripture of the ten tribes.[11]

Majority of references in this section courtesy of researcher Ted Jones.

There are many examples from India:

Laws of Manu, states that land grants were to be written on copper plates.[42]

Response to claim: "Why include the ridiculous prayer of the Zoramites in Alma 31?"

Response to claim: "Why is the Passover mentioned 71 times in the Bible, but -0- times in the Book of Mormon?"

Response to claim: "How did Book of Mormon characters get the priesthood when they weren't from the tribe of Levi?"

Response to claim: "Why was Shakespeare used?"

It is claimed that Joseph Smith plagiarized Shakespeare in order to write portions of The Book of Mormon. However, there is no evidence that Joseph had read Priest's book. Even so, there is so little of it that has parallels with the Book of Mormon that this would provide a forger with little help. The passages which suggest Shakespeare are better explained by other ancient parallels; in any case, these passages provide very little that would assist in writing the Book of Mormon.

| The Wonders of Nature(1825) | Book of Mormon | Other similar phrases |

|---|---|---|

| I then requested him to leave me, as my time was short, and I had some preparation to make before I went hence to "that bourne from whence no traveller returns." (p. 469) | "Awake! and arise from the dust, and hear the words of a trembling parent, whose limbs ye must soon lay down in the cold and silent grave, from whence no traveler can return; a few more days and I go the way of all the earth. " (2 Nephi 1:14) |

|

The phrase "from whence no traveller returns" quoted by Josiah Priest is from Shakspeare's Hamlet. Therefore, an alternate criticism is the Joseph Smith plagiarized this line from Hamlet.

B.H. Roberts notes that the critic "fairly revels in the thought that he has Lehi quoting Shakespeare many generations before our great English poet was born; and indulges in the sarcasms which Campbell and more than a score of anti-Mormon writers have indulged in who have mimicked his phraseology." Roberts notes that the Book of Job, contained in the Jewish scriptures that Lehi certainly would have been familiar with, contains two passages "which could easily have supplied both Shakespeare and Lehi with the idea of that country 'from whose bourn no traveler returns.'" In other words, Lehi could have obtained his idea from the same source from which Shakespeare obtained the inspiration for his phrase. Roberts concludes:

Wrote Hugh Nibley:

Response to claim: "What was the purpose in Moroni taking the plates back? Similarly, what ever happened to the parchment written by John of the New Testament? (D&C 7) Why weren't the supposed writings of Abraham (which were actually common A.D. funerary texts) also taken similarly back?"

Response to claim: "Why did Joseph's own accounts confuse whether he was visited by Moroni or Nephi. "He called me by name, and said unto me that he was a messenger sent from the presence of God to me, and that his name was Nephi." (J. Smith - Times & Seasons Vol. 3, p. 753 1842) also (J. Smith 1851 PoGP p. 41)."

The text in question reads as follows:

Orson Pratt would later observe:

The Church teaches that Moroni was the heavenly messenger which appeared to Joseph Smith and directed him to the gold plates. Yet, some Church sources give the identity of this messenger as Nephi. Some claim that this shows that Joseph was 'making it up as he went along.' One critic even claims that if the angel spoke about the plates being "engraven by Moroni," then he couldn't have been Moroni himself.

The identity of the angel that appeared to Joseph Smith in his room in 1823 and over the next four years was known and published as "Moroni" for many years prior to the publication of the first identification of the angel as "Nephi" in the Times and Seasons in 1842. Even an anti-Mormon publication, Mormonism Unvailed, identified the angel's name as "Moroni" in 1834—a full eight years earlier. All identifications of the angel as "Nephi" subsequent to the 1842 Times and Seasons article were using the T&S article as a source. These facts have not been hidden; they are readily acknowledged in the History of the Church:

In the original publication of the history in the Times and Seasons at Nauvoo, this name appears as "Nephi," and the Millennial Star perpetuated the error in its republication of the History. That it is an error is evident, and it is so noted in the manuscripts to which access has been had in the preparation of this work. [49]

Joseph F. Smith and Orson Pratt understood the problem more than a century ago, when they wrote in 1877 to John Taylor:

"The contradictions in regard to the name of the angelic messenger who appeared to Joseph Smith occurred probably through the mistakes of clerks in making or copying documents and we think should be corrected. . . . From careful research we are fully convinced that Moroni is the correct name. This also was the decision of the former historian, George A. Smith." [50]

The following time-line illustrates various sources that refer to the angel, and whether the name "Moroni" or "Nephi" was given to them.

As can be readily seen, the "Nephi" sources all derive from a single manuscript and subsequent copies. On the other hand, a variety of earlier sources (including one hostile source) use the name "Moroni," and these are from a variety of sources.

Details about each source are available below the graphic. Readers aware of other source(s) are encouraged to contact FairMormon so they can be included here.

This is not an example of Joseph Smith changing his story over time, but an example of a detail being improperly recorded by someone other than the Prophet, and then reprinted uncritically. Clear contemporary evidence from Joseph and his enemies—who would have seized upon any inconsistency had they known about it—shows that "Moroni" was the name of the heavenly messenger BEFORE the 1838 and 1839 histories were recorded.

Notes

FAIR is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing well-documented answers to criticisms of the doctrine, practice, and history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are a volunteer organization. We invite you to give back.

Donate Now